From Digital Design to Real-World Function: A Guide to Experimentally Validating AI-Designed Inorganic Materials

The advent of generative AI and machine learning has revolutionized the design of novel inorganic materials, but the ultimate measure of success lies in successful experimental validation.

From Digital Design to Real-World Function: A Guide to Experimentally Validating AI-Designed Inorganic Materials

Abstract

The advent of generative AI and machine learning has revolutionized the design of novel inorganic materials, but the ultimate measure of success lies in successful experimental validation. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists navigating the critical journey from in-silico design to physical synthesis and characterization. We explore the foundational principles of AI-driven materials design, detail advanced methodologies for synthesis and analysis, address common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and present frameworks for rigorous validation and comparative analysis. By synthesizing the latest 2025 research, this article serves as a strategic roadmap for accelerating the development of reliable, high-performance inorganic materials for advanced applications in biomedicine and beyond.

The New Frontier of AI-Driven Materials Design: Principles and Promise

The discovery of new inorganic materials is a fundamental driver of innovation across critical industries including renewable energy, electronics, and healthcare. However, this discovery process faces a profound bottleneck: the vastness of chemical space combined with the limitations of traditional experimental approaches. Researchers estimate that the number of possible stable inorganic compounds is orders of magnitude larger than the approximately 200,000 currently known synthesized materials [1] [2]. This discrepancy exists not because these unknown materials are inherently unstable or non-functional, but because finding them through conventional methods is both prohibitively slow and resource-intensive.

Traditional materials discovery has relied heavily on experimental trial-and-error, guided by researcher intuition and domain expertise. While this approach has yielded many foundational materials, it struggles to efficiently navigate the immense combinatorial possibilities of elemental combinations, synthesis conditions, and crystal structures. The resulting bottleneck slows the development cycle for technologies ranging from advanced battery systems to novel semiconductors. This article examines why traditional methods fall short and compares their performance against emerging computational approaches that leverage machine learning and high-throughput experimentation.

How Traditional Methods Create the Bottleneck

Reliance on Human Intuition and Limited Data

The conventional approach to materials discovery has predominantly depended on the knowledge and experience of expert solid-state chemists who specialize in specific synthetic techniques or material classes [1]. This method, while valuable, inherently limits the exploration speed and scope for several reasons:

- Domain Specialization Constraints: Experts typically operate within well-understood chemical domains of a few hundred materials, making it difficult to identify promising candidates outside their immediate focus areas [1].

- Incomplete Data Utilization: Traditional approaches struggle to integrate and analyze the exponentially growing volumes of biomedical data, including genomics, proteomics, and scientific literature [3].

- Cognitive Biases: Human researchers naturally gravitate toward chemical spaces and synthesis pathways that align with established knowledge, potentially overlooking novel or non-intuitive material combinations.

Thermodynamic Stability as an Incomplete Proxy

Traditional computational screening often relies on thermodynamic stability as the primary filter for identifying synthesizable materials, typically using density functional theory (DFT) calculations to compute formation energies [1] [2]. However, this approach captures only one aspect of synthesizability:

- Limited Predictive Power: Formation energy calculations alone fail to identify approximately 50% of synthesized inorganic crystalline materials because they cannot account for kinetic stabilization and complex synthesis pathway dependencies [1].

- Resource Intensity: High-accuracy DFT calculations are computationally expensive, creating their own bottleneck in screening large chemical spaces [4].

- Ignoring Practical Factors: Thermodynamic approaches cannot incorporate real-world synthesis considerations such as precursor availability, equipment requirements, or economic constraints [1] [2].

Table 1: Limitations of Traditional Synthesizability Assessment Methods

| Method | Primary Mechanism | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Expert Intuition | Domain knowledge and specialized experience | Limited to familiar chemical spaces; difficult to scale or transfer |

| Charge-Balancing | Net neutral ionic charge based on common oxidation states | Only 37% of known synthesized materials are charge-balanced; too rigid for different bonding environments [1] |

| DFT Formation Energy | Thermodynamic stability relative to competing phases | Computationally intensive; misses 50% of synthesized materials; ignores kinetic effects [1] |

| Literature Mining | Extraction of synthesis recipes from published studies | Relies on published successes; lacks negative results; cannot assess novel compositions [5] |

Quantitative Comparison: Traditional vs. Modern Approaches

The limitations of traditional methods become starkly evident when comparing their performance against modern computational approaches using objective metrics. Recent research has enabled direct head-to-head comparisons between human experts and machine learning models for predicting synthesizable materials.

In a systematic evaluation, a deep learning synthesizability model (SynthNN) was tested against 20 expert materials scientists in a material discovery task [1]. The results demonstrated a significant performance gap:

Table 2: Performance Comparison: Human Experts vs. Machine Learning

| Assessment Method | Precision in Identifying Synthesizable Materials | Time Required for Assessment | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Experts (Best Performer) | Baseline | Baseline (hours to days) | Domain knowledge; understanding of context |

| Charge-Balancing Method | 7× lower than SynthNN [1] | Seconds | Fast; chemically intuitive |

| SynthNN (ML Model) | 1.5× higher than best human expert [1] | 5 orders of magnitude faster | Scalable; data-driven; consistent |

Beyond synthesizability prediction, modern approaches demonstrate superior efficiency across multiple discovery phases. For example, AI-discovered drugs have entered Phase II trials in just 12 months—85% faster than traditional methods [3]. Pharmaceutical companies using machine learning for target identification have cut preclinical trial costs by 28% [3], demonstrating how computational acceleration translates to economic benefits.

Modern Approaches Overcoming the Bottleneck

Machine Learning for Synthesizability Prediction

Novel machine learning approaches are directly addressing the synthesizability challenge by learning from the complete historical record of synthesized materials. The SynthNN model exemplifies this approach:

Experimental Protocol: SynthNN Development and Validation

- Training Data: Models are trained on chemical formulas from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), representing the nearly complete history of synthesized crystalline inorganic materials [1].

- Representation Learning: The atom2vec algorithm learns optimal chemical representations directly from the distribution of synthesized materials, without requiring pre-defined chemical rules [1].

- Handling Data Limitations: Positive-unlabeled learning techniques account for the lack of confirmed negative examples (unsynthesizable materials) in scientific literature [1].

- Validation: Models are benchmarked against both computational methods (charge-balancing, formation energy) and human experts using precision-recall metrics [1].

This data-driven approach allows models to learn complex chemical principles implicitly, including charge-balancing relationships, chemical family similarities, and ionicity trends, without explicit programming of these concepts [1].

High-Throughput Experimental Databases

The creation of large-scale experimental databases represents another paradigm shift in materials discovery. The High Throughput Experimental Materials (HTEM) Database exemplifies this approach:

Experimental Protocol: High-Throughput Data Generation

- Combinatorial Synthesis: Thin-film sample libraries are synthesized using combinatorial physical vapor deposition methods, enabling parallel processing of thousands of compositions [6].

- Automated Characterization: Structural (X-ray diffraction), chemical (composition), and optoelectronic (absorption spectra, conductivity) properties are measured using spatially-resolved techniques [6].

- Data Infrastructure: Custom laboratory information management systems automatically harvest instrument data, align synthesis and characterization metadata, and provide programmatic access through application programming interfaces [6].

- Scale: As of 2018, the HTEM Database contained over 140,000 sample entries with structural, synthetic, chemical, and optoelectronic properties [6].

This infrastructure enables researchers without access to specialized equipment to explore materials data and provides the large, diverse datasets needed to train accurate machine learning models.

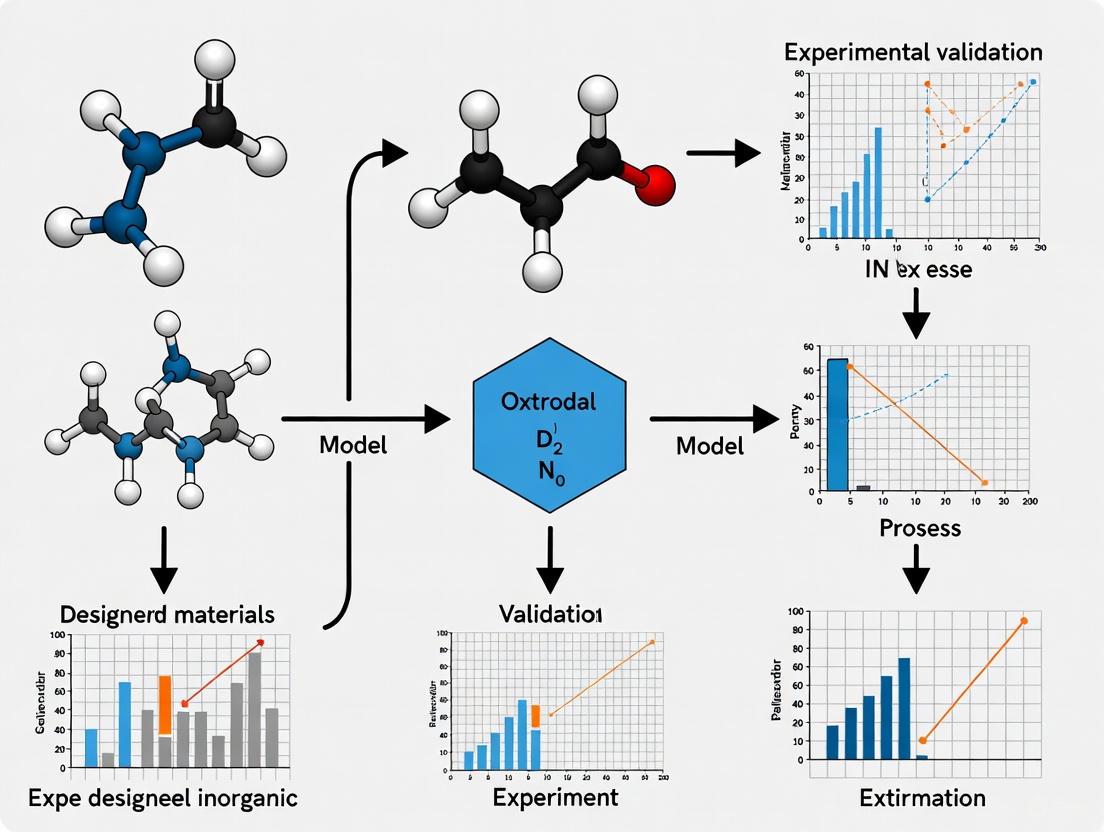

Diagram 1: Traditional vs. Modern Discovery Workflows

Implementing modern materials discovery approaches requires specialized computational and data resources. The following tools and databases have become essential for overcoming traditional bottlenecks:

Table 3: Essential Resources for Modern Inorganic Materials Discovery

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| HTEM Database [6] | Experimental Database | Provides open access to high-throughput experimental materials data | >140,000 samples; synthesis conditions; structural and optoelectronic properties |

| ICSD [1] | Structural Database | Curated repository of inorganic crystal structures | Nearly complete history of synthesized inorganic materials; essential for training ML models |

| SynthNN [1] | Machine Learning Model | Predicts synthesizability of inorganic chemical formulas | 1.5× higher precision than human experts; requires no structural information |

| Materials Stability Network [2] | Analytical Framework | Models discovery likelihood using network science | Combines thermodynamic data with historical discovery timelines; encodes circumstantial factors |

| OQMD [2] [4] | Computational Database | Density functional theory calculations for materials | Formation energies; stability predictions; electronic properties |

| FHI-aims [4] | Simulation Software | All-electron DFT with hybrid functionals | Higher accuracy for electronic properties; particularly valuable for transition metal oxides |

The inorganic materials discovery bottleneck, long constrained by traditional methods' limitations, is being systematically addressed through integrated computational and experimental approaches. The evidence demonstrates that modern machine learning techniques can outperform human experts in identifying synthesizable materials while operating at dramatically accelerated timescales. However, the most promising path forward lies in hybrid approaches that combine the pattern recognition power of algorithms with the domain expertise and contextual understanding of materials scientists.

Future progress will depend on continued expansion of high-quality experimental databases, development of more sophisticated synthesizability models that incorporate synthesis pathway information, and creation of better validation frameworks for computational predictions. As these technologies mature, they promise to transform materials discovery from a rate-limited process into an accelerated innovation engine, enabling the rapid development of materials needed to address pressing global challenges in energy, healthcare, and sustainability.

The field of inorganic materials discovery is undergoing a fundamental transformation, shifting from a screening-based paradigm to a generative, inverse design approach. Historically, materials innovation relied on experimental trial and error, a process that often spanned decades from conception to deployment [7]. Computational screening of large materials databases accelerated this process but remained fundamentally limited by the number of known materials, representing only a tiny fraction of potentially stable inorganic compounds [8]. The emergence of generative artificial intelligence (AI) represents a paradigm shift toward inverse design, where desired properties serve as input and AI models generate novel material structures matching these specifications [9] [10]. This approach inverts the traditional discovery pipeline, enabling researchers to navigate the vast chemical space—estimated to exceed 10^60 carbon-based molecules—with unprecedented efficiency [7].

This comparison guide examines the experimental validation of two predominant generative AI frameworks in inorganic materials research: diffusion-based models (exemplified by MatterGen) and LLM-driven agent frameworks (represented by MatAgent). We objectively compare their performance metrics, computational efficiency, and experimental validation results to provide researchers with a comprehensive assessment of current capabilities and limitations in this rapidly evolving field.

Comparative Analysis of Generative AI Frameworks

MatterGen: A Diffusion-Based Approach

MatterGen is a diffusion model specifically tailored for designing crystalline materials across the periodic table [8] [10]. Similar to how image diffusion models generate pictures from text prompts, MatterGen generates proposed crystal structures by adjusting atom positions, elements, and periodic lattices through a learned denoising process [10]. Its architecture handles periodicity and 3D geometry through specialized corruption processes for atom types, coordinates, and lattice parameters [8]. The model was trained on 607,683 stable structures from the Materials Project and Alexandria databases (Alex-MP-20) and can be fine-tuned with property labels for targeted inverse design [8].

MatAgent: An LLM-Driven Agent Framework

MatAgent employs a large language model (LLM) as its central reasoning engine, integrated with external cognitive tools including short-term memory, long-term memory, a periodic table, and a materials knowledge base [11] [12]. Unlike single-step generation models, MatAgent uses an iterative, feedback-driven process where the LLM proposes compositions, a structure estimator generates crystal configurations, and a property evaluator provides feedback for refinement [12]. This framework emulates human expert reasoning by leveraging historical data and fundamental chemical knowledge to guide exploration toward target properties [12].

Performance Metrics and Experimental Validation

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Comparative Performance Metrics of Generative AI Frameworks for Inorganic Materials Design

| Metric | MatterGen | MatAgent | Traditional Screening | Previous Generative Models (CDVAE/DiffCSP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stability Rate | 78% of generated structures within 0.1 eV/atom of convex hull [8] | High compositional validity via iterative refinement [12] | Limited to known stable materials | Lower than MatterGen [8] |

| Novelty Rate | 61% of generated structures new to established databases [8] | High novelty through expanded compositional space [12] | No novelty (limited to known materials) | Lower novelty than MatterGen [8] |

| Structural Quality | 95% of structures with RMSD < 0.076 Å to DFT-relaxed structures [8] | Dependent on structure estimator accuracy [12] | DFT-ready structures | ~10x higher RMSD than MatterGen [8] |

| Success Rate for Target Properties | Effective across mechanical, electronic, and magnetic properties [10] | Interpretable, iterative refinement toward targets [12] | Limited to properties of known materials | Limited to narrow property sets [8] |

| Compositional Diversity | Broad coverage across periodic table [8] | Vast expansion via external knowledge bases [12] | Limited to known compositions | Often constrained to narrow element subsets [8] |

Table 2: Experimental Validation Results for Generated Materials

| Validation Method | MatterGen Results | MatAgent Capabilities | Traditional Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT Relaxation | Structures >10x closer to local energy minimum than previous models [8] | Property evaluation via GNN predictors [12] | Standard validation approach |

| Experimental Synthesis | TaCr₂O₆ synthesized with measured bulk modulus (169 GPa) within 20% of target (200 GPa) [10] | Framework supports experimental validation [12] | Time-consuming and resource-intensive |

| Stability Assessment | 13% of structures below convex hull of MP database [8] | Formation energy prediction for stability screening [12] | Standard assessment for discovered materials |

| Rediscovery Rate | >2,000 experimentally verified ICSD structures not seen during training [8] | Not explicitly reported | Benchmark for generative effectiveness |

Computational Efficiency and Screening Acceleration

Generative AI approaches demonstrate remarkable computational efficiency gains compared to traditional methods. MatterGen enables rapid exploration of novel materials space without the exhaustive screening required by high-throughput virtual screening (HTVS) approaches [8] [10]. In one sustainable packaging materials study, a GAN-based inverse design framework achieved 20-100× acceleration in screening efficiency compared to traditional DFT calculations while maintaining high accuracy [13]. This efficiency stems from the direct generation of candidate materials rather than exhaustive screening of known databases, particularly valuable for identifying materials with multiple property constraints that would be computationally prohibitive to discover through conventional means [13].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

MatterGen Training and Validation Protocol

Dataset Curation:

- Source: 607,683 stable structures from Materials Project and Alexandria databases (Alex-MP-20)

- Filtering: Structures with up to 20 atoms per unit cell

- Reference for Stability: Alex-MP-ICSD dataset with 850,384 unique structures for convex hull calculations [8]

Model Architecture:

- Diffusion process with specialized corruption for atom types, coordinates, and lattice

- Wrapped Normal distribution for coordinate diffusion respecting periodic boundaries

- Symmetric lattice diffusion approaching cubic lattice distribution

- Categorical diffusion with masking for atom types [8]

Validation Methodology:

- DFT calculations performed on 1,024 generated structures

- Stability threshold: <0.1 eV/atom above convex hull

- Uniqueness: No match to other generated structures

- Novelty: No match to structures in extended Alex-MP-ICSD database [8]

- Experimental synthesis validation for selected candidates [10]

MatAgent Workflow Protocol

Framework Configuration:

- LLM as central reasoning engine with planning and proposition stages

- External tools: Short-term memory, long-term memory, periodic table, materials knowledge base

- Structure estimator: Diffusion-based crystal structure generation model

- Property evaluator: Graph neural network trained on MP-60 dataset [12]

Iterative Refinement Process:

- Planning Stage: LLM analyzes current context and selects appropriate tool

- Proposition Stage: LLM generates new composition with explicit reasoning

- Structure Estimation: Multiple candidate structures generated for composition

- Property Evaluation: Formation energy prediction and feedback generation [12]

Validation Approach:

- Compositional validity checks

- Formation energy prediction via GNN

- Stability assessment through structure relaxation [12]

Diagram 1: Comparative workflows of MatterGen and MatAgent frameworks

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Generative Materials Design

| Tool/Category | Function | Examples/Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Generative Models | Create novel material structures | Diffusion models (MatterGen), GANs, VAEs, GFlowNets [7] |

| Property Predictors | Accelerate property evaluation without DFT | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), Equivariant Transformers (EquiformerV2) [13] |

| Materials Databases | Provide training data and reference structures | Materials Project, OMat24, ICSD, Alexandria [8] [13] |

| Structure Matching Algorithms | Assess novelty and uniqueness | Ordered-disordered structure matcher [10] |

| Stability Assessment | Evaluate thermodynamic stability | DFT relaxation, convex hull analysis [8] |

| Fine-tuning Modules | Steer generation toward target properties | Adapter modules, classifier-free guidance [8] |

The experimental validation of generative AI frameworks for inorganic materials design demonstrates a significant paradigm shift from screening to inverse design. MatterGen's diffusion-based approach sets a new standard for generating stable, diverse materials with high success rates and experimental validation [8] [10]. MatAgent's LLM-driven framework offers enhanced interpretability and iterative refinement capabilities, though with more indirect experimental validation to date [12]. Both approaches substantially outperform traditional screening methods in novelty generation and computational efficiency for multi-property optimization.

Future developments will likely focus on integrating these approaches with experimental synthesis pipelines, improving handling of compositional disorder, and expanding property constraints for specialized applications. As these technologies mature, generative AI is poised to dramatically accelerate the discovery of next-generation materials for energy storage, catalysis, electronics, and sustainability applications [14]. The experimental validation of TaCr₂O₆ with properties closely matching design targets provides compelling evidence that generative inverse design can bridge the gap between computational prediction and practical materials synthesis [10].

The discovery of new inorganic crystals is a fundamental driver of technological progress, powering innovations from advanced lithium-ion batteries to efficient solar cells and carbon capture technologies [10]. Historically, identifying new materials has been a slow and resource-intensive process, relying heavily on experimental trial-and-error or computational screening of known candidates [15]. The emerging paradigm of generative artificial intelligence is transforming this landscape by enabling the direct creation of novel crystal structures tailored to specific property constraints [10]. Among these approaches, MatterGen, a diffusion model developed by Microsoft Research, represents a significant advancement in the generative design of inorganic materials across the periodic table [16] [17].

This guide provides an objective comparison of MatterGen's performance against other state-of-the-art crystal structure prediction (CSP) and generation methods, with a specific focus on experimental validation within inorganic materials research. We examine quantitative metrics for stability, novelty, and property-specific generation, detail methodological protocols, and contextualize these findings within the broader framework of validating computationally designed materials. For researchers and scientists engaged in materials discovery and drug development, understanding the capabilities and limitations of these generative models is crucial for integrating them effectively into the materials design pipeline.

Performance Benchmarking: MatterGen Versus Alternative Approaches

Comparative Performance Metrics for Crystal Generation

The evaluation of generative models for materials requires robust metrics that assess both the structural quality and thermodynamic stability of proposed crystals. Key performance indicators include the percentage of generated structures that are Stable, Unique, and Novel (S.U.N.), the Root Mean Square Distance (RMSD) to relaxed structures, and success rates in property-conditional generation [16] [17].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Generative Models for Inorganic Crystals (Based on 1,024 Generated Samples Each)

| Model | % S.U.N. | RMSD (Å) | % Stable | % Unique | % Novel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MatterGen | 38.57 | 0.021 | 74.41 | 100.0 | 61.96 |

| MatterGen (MP20) | 22.27 | 0.110 | 42.19 | 100.0 | 75.44 |

| DiffCSP (Alex-MP-20) | 33.27 | 0.104 | 63.33 | 99.90 | 66.94 |

| DiffCSP (MP20) | 12.71 | 0.232 | 36.23 | 100.0 | 70.73 |

| CDVAE | 13.99 | 0.359 | 19.31 | 100.0 | 92.00 |

| G-SchNet | 0.98 | 1.347 | 1.63 | 100.0 | 98.23 |

| P-G-SchNet | 1.29 | 1.360 | 3.11 | 100.0 | 97.63 |

The data reveals that MatterGen achieves state-of-the-art performance on the critical S.U.N. metric, generating stable, unique, and novel structures at more than double the rate of other deep generative models like CDVAE [16]. Furthermore, its exceptionally low RMSD indicates that generated structures are very close to their local energy minima, reducing the computational cost required for subsequent relaxation [16] [18].

Performance in Property-Conditioned Generation

A key advantage of generative models over screening methods is their ability to directly create candidates for desired extreme properties, effectively exploring beyond known materials databases [10]. MatterGen's adapter-based fine-tuning architecture enables conditioning on a wide range of properties, including chemical system, space group, and electronic, magnetic, and mechanical properties [16] [18].

Table 2: MatterGen's Performance in Property-Conditioned Generation

| Generation Task | Condition | Performance Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical System | Well-explored systems | 83% S.U.N. structures |

| Chemical System | Partially explored systems | 65% S.U.N. structures |

| Chemical System | Unexplored systems | 49% S.U.N. structures |

| Bulk Modulus | 400 GPa | 106 S.U.N. structures obtained within a budget of 180 DFT calculations |

| Magnetic Density | > 0.2 μB Å⁻³ | 18 S.U.N. structures obtained within a budget of 180 DFT calculations |

In a notable demonstration, MatterGen was tasked with generating materials possessing both high magnetic density and a chemical composition with low supply-chain risk, showcasing its capability for multi-property optimization [18]. This ability to balance multiple, potentially competing design constraints is particularly valuable for real-world materials engineering.

Experimental Protocols and Validation Frameworks

MatterGen's Model Architecture and Training Protocol

Model Type and Architecture: MatterGen is a diffusion model that operates on the 3D geometry of crystalline materials [17] [10]. Its architecture is based on GemNet, a class of graph neural networks adept at modeling atomic interactions [17]. The model jointly generates a material's atomic fractional coordinates, element types, and periodic unit cell lattice parameters through a learned denoising process [18].

Training Data and Preprocessing:

- Data Sources: The model was trained on approximately 608,000 stable crystalline materials from the Materials Project (MP) and Alexandria (Alex) databases [17] [10].

- Data Filtering: Structures were limited to those with up to 20 atoms in the unit cell and an energy above the convex hull below 0.1 eV/atom. Structures containing noble gas elements, radioactive elements, or elements with an atomic number greater than 84 were excluded [17].

- Preprocessing: All training structures were converted to their primitive cell representation. Unit cell lattices were processed using Niggli reduction and polar decomposition to ensure lattice matrices were symmetric [17].

Training Hyperparameters:

- Initial learning rate of 1e-4, reduced by a factor of 0.6 when the training loss plateaued.

- Batch size of 512.

- Training conducted in float32 precision [17].

Structure Generation and Evaluation Methodology

The process for generating and validating new crystal structures involves a multi-step workflow, combining AI generation with physics-based simulation to ensure predicted stability and properties are reliable.

Unconditional Generation Protocol [16]:

- Model Loading: Load a pre-trained MatterGen checkpoint (e.g.,

mattergen_base). - Sampling: Execute the

mattergen-generatecommand with specified parameters such asbatch_sizeandnum_batches. - Output: The script produces several files:

generated_crystals_cif.zip: Individual CIF files for each generated structure.generated_crystals.extxyz: A single file containing all generated structures as frames.generated_trajectories.zip(optional): Contains the full denoising trajectory for each structure.

Property-Conditioned Generation Protocol [16]:

- Model Selection: Load a fine-tuned model (e.g.,

dft_mag_densityfor magnetic properties,chemical_system_energy_above_hullfor joint constraints). - Condition Specification: Use the

--properties_to_condition_onflag to specify target property values (e.g.,{'dft_mag_density': 0.15}). - Guidance: Apply classifier-free guidance with

--diffusion_guidance_factor(typically 2.0) to enhance conditioning fidelity.

Evaluation Protocol [16]:

- Relaxation: Generated structures are relaxed using the MatterSim machine learning force field (MLFF) to reach a local energy minimum. The larger

MatterSim-v1-5Mmodel can be used for improved accuracy. - Stability Assessment: The energy above the convex hull (Eₕᵤₗₗ) is computed for each relaxed structure. A structure is typically considered stable if Eₕᵤₗₗ < 0.1 eV/atom [17].

- Novelty and Uniqueness Check: A structure is deemed novel if it does not match any entry in a reference database (e.g., MP2020) using a structure matcher. Uniqueness requires that no two generated structures are identical [16] [17].

- DFT Validation: For high-fidelity assessment, a subset of promising candidates can be further relaxed and have their energies computed using Density Functional Theory (DFT), which is considered the gold standard despite higher computational cost [16].

Critical Evaluation of Validation Metrics

The benchmarking of generative models for materials must carefully align regression metrics with task-relevant classification performance [19]. Accurate prediction of formation energy (a regression task) does not guarantee correct stability classification if the predicted value lies close to the convex hull boundary. Consequently, frameworks like Matbench Discovery emphasize classification metrics (e.g., precision, recall, false-positive rates) for true prospective discovery performance [19]. MatterGen's evaluation adopts this rigorous approach by reporting S.U.N. percentages, which directly reflect success in a discovery-oriented task [16] [17].

The Research Toolkit for Generative Materials Design

The effective application of generative models like MatterGen relies on a suite of computational tools and databases that form the modern materials informatics pipeline.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Generative Crystal Design

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| MatterGen | Generative AI Model | Core engine for generating novel crystal structures with optional property conditioning [16] [10]. |

| MatterSim | Machine Learning Force Field (MLFF) | Fast relaxation of generated structures and prediction of energies and forces; used for stability pre-screening [16] [10]. |

| DFT Software (e.g., VASP) | Quantum Mechanical Simulation | High-fidelity validation of structural stability and electronic/magnetic properties; the computational gold standard [16] [20]. |

| Materials Project (MP) | Materials Database | Source of training data and reference structures for evaluating novelty and constructing convex hulls [17]. |

| Alexandria Database | Materials Database | Source of additional training data, including many hypothetical crystal structures [17]. |

| Structure Matcher | Evaluation Algorithm | Determines if two crystal structures are identical, accounting for symmetry and compositional disorder; critical for assessing novelty and uniqueness [16]. |

The experimental validation of MatterGen underscores the transformative potential of generative AI in inorganic materials research. Quantitative benchmarks demonstrate its superior performance in generating stable, novel, and unique crystals compared to prior generative models [16] [18]. The model's capacity for property-conditioned and multi-property optimization enables a targeted exploration of chemical space far beyond the limits of conventional database screening [10].

The successful experimental synthesis of TaCr2O6, a material generated by MatterGen conditioned on a high bulk modulus, provides critical proof-of-concept. The measured bulk modulus of 169 GPa aligned with the target specification of 200 GPa, representing a relative error below 20% from design to lab—a significant achievement in experimental materials science [10].

Looking forward, the integration of generative models like MatterGen with rapid validation tools like MatterSim creates a powerful design flywheel for materials discovery [10]. This synergistic combination accelerates both the proposal of promising candidates and the simulation of their properties. For researchers in materials science and drug development, adopting these tools necessitates a focus on robust experimental protocols and rigorous evaluation metrics that prioritize real-world discovery outcomes over retrospective benchmark performance. As these foundational models continue to evolve, they promise to significantly shorten the development cycle for next-generation materials addressing pressing global challenges.

The discovery of new inorganic materials is a cornerstone of technological progress, pivotal to advancements in fields ranging from renewable energy to healthcare. Traditional, intuition-driven discovery processes are often slow, costly, and inefficient. The emergence of generative AI has heralded a paradigm shift, introducing powerful tools capable of designing novel materials at an unprecedented scale. However, this potential can only be realized with robust and reliable methods to evaluate the outputs of these AI models. This guide focuses on three critical metrics for the experimental validation of AI-designed inorganic materials: Stability, Uniqueness, and Novelty (SUN). We will objectively compare the performance of leading AI systems—Microsoft's MatterGen, Google's GNoME, and the research framework MatAgent—by examining their reported SUN metrics and the experimental protocols used to derive them.

Core SUN Metrics and Comparative Performance

For researchers, the ultimate test of a generative AI model is the quality of its proposed materials. The SUN metrics provide a quantitative framework for this assessment. The table below summarizes the performance of major AI systems against these benchmarks.

Table 1: SUN Performance Comparison of AI Materials Design Models

| AI System / Model | Reported Stability Metrics | Reported Novelty & Uniqueness Metrics | Key Reported Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| MatterGen (Microsoft) | • Stability Above Hull (S.A.H.): Percentage of structures with energy above convex hull below a threshold [21]• Relaxation Displacement: RMSD between pre- and post-relaxed structures [21] | • Novelty: Percentage of generated structures not matching any in a reference dataset [21]• Uniqueness: Percentage of generated structures not matching other generated structures [21] | A generative model designed for property-guided materials design, focusing on proposing new materials that meet specific needs [22]. |

| GNoME (Google DeepMind) | • 380,000 stable materials identified as promising candidates for experimental synthesis [23]• Stable materials are those that "lie on the convex hull," a mathematical representation of thermodynamic stability [23] | • 2.2 million new crystals discovered, dramatically expanding the known library of materials [23]• These findings include 52,000 new layered compounds similar to graphene [23] | 2.2 million new crystal structures predicted, of which 380,000 are classified as stable [23]. |

| MatAgent (Research Framework) | Achieves high compositional validity through iterative, feedback-driven guidance [11] | Consistently achieves high uniqueness and material novelty by leveraging a vast materials knowledge base to explore new compositional space [11] | An AI agent that combines a diffusion model with a property predictor, using cognitive tools to steer exploration toward user-defined targets [11]. |

Experimental Protocols for SUN Metric Evaluation

The quantitative data presented in Table 1 is the result of rigorous computational and experimental workflows. Understanding these methodologies is crucial for interpreting the results and assessing their validity.

Stability Validation Protocol

Stability, often considered the most critical metric, confirms that a proposed material is thermodynamically viable and unlikely to decompose.

Computational Workflow:

- Energy Calculation: The formation energy of a proposed AI-generated crystal structure is computed using Density Functional Theory (DFT), a first-principles quantum mechanical method [23].

- Convex Hull Construction: The computed energy is plotted against the energies of all other known compositions and phases in a relevant chemical space to form a convex hull. The most stable structures reside on this hull [23].

- Stability Classification:

- Relaxation Displacement: The initial AI-generated structure is computationally "relaxed" to its lowest energy state. The Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) between the original and relaxed structures is a key metric; a small displacement indicates the initial prediction was highly stable [21].

Experimental Corroboration: The gold standard for stability validation is successful lab synthesis. For instance, external researchers have independently created 736 of GNoME's predicted structures in the laboratory, providing tangible proof of the model's accuracy [23].

Uniqueness and Novelty Assessment Protocol

These metrics ensure that the AI is generating genuinely new materials, not just replicating known ones.

- Structure Matching: This is the core technique for evaluating novelty and uniqueness. MatterGen, for example, employs several specialized matchers [21]:

- OrderedStructureMatcher: For strict, element-by-element comparison to known structures.

- DisorderedStructureMatcher: A more sophisticated algorithm that allows for element substitution based on physical properties (e.g., atomic radius, electronegativity), recognizing when a new structure is an ordered approximation of a known disordered material like an alloy [21].

- Novelty Calculation: A material is deemed novel if it fails to match any structure in a comprehensive reference dataset (e.g., the Materials Project) using the matchers above [21].

- Uniqueness Calculation: Among a set of AI-generated candidates, a material is unique if it does not match any other candidate within the same set, ensuring diversity in the output [21].

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for evaluating these core metrics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

In the context of AI-driven materials discovery, "research reagents" extend beyond chemicals to encompass the computational tools, datasets, and software that are fundamental to the process. The following table details key components of the modern materials informatics toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for AI-Driven Materials Discovery

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in SUN Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Computational Method | The quantum mechanical standard for calculating formation energy and determining thermodynamic stability via convex hull construction [23]. |

| Materials Project Database | Open Data Resource | A comprehensive repository of known crystal structures and computed properties; serves as the essential reference dataset for novelty checks [23]. |

| Structure Matchers (e.g., Ordered/Disordered) | Software Algorithm | Core tools for comparing crystal structures to assess novelty (against known materials) and uniqueness (within a generated set) [21]. |

| Active Learning Loop | AI Training Framework | A process where AI predictions (e.g., on stability) are validated (e.g., by DFT) and fed back into the model to continuously and dramatically improve its accuracy [23]. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | AI Model Architecture | A type of model (e.g., in GNoME) that naturally represents atomic connections in crystals, making it particularly powerful for predicting new stable structures [23]. |

The rigorous benchmarking of generative AI models using Stability, Uniqueness, and Novelty (SUN) metrics is not an academic exercise—it is a prerequisite for their successful application in real-world materials discovery. As the comparative data shows, systems like MatterGen and GNoME are already achieving remarkable results, predicting hundreds of thousands of stable and novel materials that are now being validated experimentally. For researchers in drug development and other applied sciences, these metrics provide a reliable framework for selecting and trusting AI tools. By understanding and applying the experimental protocols behind the SUN framework, scientists can critically evaluate AI-generated candidates, focusing precious experimental resources on the most promising leads and truly accelerating the journey from digital design to physical reality.

The field of inorganic materials research is undergoing a fundamental transformation, moving beyond the traditional focus on optimizing single properties toward a holistic approach that balances multiple functional constraints with pressing sustainability requirements. This paradigm shift is driven by the growing complexity of global challenges in energy, healthcare, and environmental technologies, which demand materials that simultaneously excel across mechanical, thermal, optical, and electrochemical domains while minimizing environmental impact. The integration of advanced experimental methodologies with computational guidance and data-driven optimization has created unprecedented opportunities to accelerate the discovery and development of such multi-functional inorganic materials [24] [25].

This evolution necessitates rigorous experimental validation frameworks capable of systematically evaluating material performance across multiple property domains. Researchers now employ sophisticated approaches that combine high-throughput experimentation with multi-scale characterization to unravel complex structure-property relationships. The critical challenge lies in designing materials that not only meet diverse performance specifications but also align with principles of green chemistry and sustainable manufacturing throughout their lifecycle [26] [27]. This comparison guide examines current experimental methodologies, provides quantitative performance comparisons across material classes, and details protocols for validating multi-functional inorganic materials within a sustainability context.

Experimental Frameworks for Multi-Functional Validation

Advanced Experimentation and Characterization Methods

The evaluation of multi-functional inorganic materials requires sophisticated experimental frameworks that can simultaneously probe multiple property domains. Autonomous experimentation platforms, particularly self-driving laboratories, have emerged as powerful tools for rapidly exploring complex parameter spaces. These systems integrate real-time, in situ characterization with microfluidic principles to enable continuous mapping of transient reaction conditions to steady-state equivalents [24]. When applied to material systems such as CdSe colloidal quantum dots, dynamic flow experiments have demonstrated at least an order-of-magnitude improvement in data acquisition efficiency while significantly reducing both time and chemical consumption compared to state-of-the-art self-driving fluidic laboratories [24].

Complementary characterization techniques provide insights into multiple property domains. Structural properties are typically evaluated using X-ray diffraction (XRD) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM), while surface characteristics are analyzed through Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area measurements and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). Functional performance assessments span electrical conductivity measurements, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, thermal stability analysis via thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), and mechanical property evaluation through nanoindentation and tensile testing [28] [29]. For sustainability assessment, life cycle inventory methods quantify energy consumption and waste generation, while specialized protocols evaluate recyclability and reusability potential.

Data-Driven Methodologies and Computational Guidance

The growing complexity of multi-functional material design has accelerated the adoption of machine learning (ML) techniques and computational guidance throughout the materials development pipeline. Data-driven methods now enable researchers to predict synthesis outcomes, optimize processing parameters, and identify promising compositional spaces with significantly reduced experimental overhead [25]. These approaches leverage diverse material descriptors—including compositional features, structural fingerprints, and processing conditions—to build predictive models that guide experimental planning.

Physical models based on thermodynamics and kinetics provide the fundamental framework for assessing synthesis feasibility, while ML techniques including neural networks, Gaussian processes, and random forests extract complex patterns from experimental data [25]. The integration of these computational approaches with high-throughput experimentation has proven particularly valuable for navigating multi-objective optimization problems, where trade-offs between conflicting property requirements must be carefully balanced. Transfer learning strategies further enhance the efficiency of these approaches by leveraging knowledge from data-rich material systems to accelerate development in less-explored domains [25].

Table 1: Comparison of Experimental Methodologies for Multi-Functional Materials Validation

| Methodology | Key Features | Property Domains Accessible | Throughput | Sustainability Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Flow Experiments [24] | Continuous parameter mapping, real-time characterization | Optical, structural, compositional | Very High (>10x conventional) | Reduces chemical consumption >10x |

| Autonomous Experimentation [24] | Self-driving labs, closed-loop optimization | Multiple simultaneous properties | High | Minimizes waste, energy efficient |

| High-Throughput Screening [25] | Parallel synthesis, rapid characterization | Structural, electronic, catalytic | High | Optimizes resource utilization |

| Computational-Guided Design [25] | ML predictions, theory-guided exploration | Theoretical properties, stability | Very High | Virtual screening reduces experimental trials |

| Sol-Gel Processing [29] | Low-temperature synthesis, hybrid materials | Mechanical, optical, electrical | Medium | Energy efficient, versatile chemistry |

Performance Comparison of Multi-Functional Inorganic Material Systems

Structural and Energy Materials

The pursuit of multi-functional performance has yielded significant advances in structural and energy-focused inorganic materials. Organic-inorganic hybrid materials exemplify this approach, with Class II hybrid systems (featuring covalent bonds between organic and inorganic components) demonstrating exceptional multi-functionality through synergistic property enhancements [28] [29]. These materials achieve performance characteristics unattainable through single-component systems, enabling applications from solid-state batteries to advanced structural composites.

In energy storage, novel double-network polymer electrolytes based on nonhydrolytic sol-gel reactions of tetraethyl orthosilicate with in situ polymerization of zwitterions demonstrate exceptional multi-functional performance [29]. These materials combine high strength and stretchability with wide electrochemical windows and excellent interface compatibility with Li metal electrodes. Similarly, aerogel composites incorporating MXenes and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) exhibit outstanding electrical conductivity, mechanical robustness, and specific capacitance that outperforms conventional supercapacitors, while also providing exceptional thermal insulation properties [27].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Multi-Functional Inorganic Material Systems

| Material System | Key Functional Properties | Sustainability Profile | Primary Applications | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CdSe Colloidal Quantum Dots [24] | Tunable optoelectronics, photocatalytic | Reduced chemical consumption >10x | Photovoltaics, displays, sensing | High quantum yield (>80%), size-tunable absorption |

| Organic-Inorganic Hybrid Electrolytes [29] | High ionic conductivity, mechanical strength | Low processing temperature | Solid-state batteries | Strength >5 MPa, electrochemical window >4.5V |

| Aerogel Composites [27] | Thermal insulation, energy storage | High porosity (99.8%), sustainable precursors | Insulation, supercapacitors | Thermal conductivity <0.02 W/m·K, specific capacitance >500 F/g |

| PANI-MoS2 Hybrids [30] | Hg(II) detection, electrical conductivity | Green synthesis, water remediation | Environmental sensing | Detection threshold 0.03 μg/L, selective complexation |

| Self-Healing Concrete [27] | Crack autonomy, structural strength | Reduced concrete replacement | Sustainable infrastructure | Autonomous crack sealing, 30% extended service life |

Functional Coatings and Composite Systems

Inorganic coating materials represent another domain where multi-functional performance is increasingly critical. The global inorganic coatings market reflects this trend, projected to rise from USD 78.9 billion in 2025 to USD 126.4 billion by 2032, driven by demands for durability, corrosion resistance, and sustainable material technologies [26]. Advanced coating systems now combine multiple functionalities—including corrosion protection, thermal management, and environmental responsiveness—in single formulations.

Cerate coatings have emerged as preferred multi-functional alternatives to chromates, offering non-toxic composition, superior corrosion protection, and self-healing characteristics while eliminating hazardous materials [26]. In electric vehicle applications, specialized inorganic coatings provide simultaneous thermal resistance, dielectric strength, and enhanced durability for battery packs and power electronics. Similarly, powder coatings combine zero VOC emissions with durable finishes and alignment with global environmental compliance standards, demonstrating how environmental and performance objectives can be simultaneously addressed [26].

Hybrid fiber reinforced polymer composites (HFRPCs) combine organic and inorganic fibers within a polymer matrix to leverage the strengths of each component while addressing individual limitations [29]. These systems achieve enhanced mechanical properties and performance suitable for automotive, aerospace, and construction applications, with demonstrated advantages in both performance and cost-effectiveness derived from the strategic combination of materials [29].

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Functional Validation

Protocol 1: Dynamic Flow Synthesis and Characterization of Quantum Materials

This protocol details the experimental workflow for flow-driven synthesis and multi-property characterization of inorganic quantum materials, adapted from established methodologies with modifications for enhanced sustainability [24].

Materials and Equipment:

- Microfluidic reactor system with temperature control (0-200°C)

- Precursor solutions (CdO, Se powder, fatty acids)

- Inline UV-Vis spectrophotometer

- Photoluminescence spectrometer

- Transmission electron microscope

- Dynamic light scattering instrument

Procedure:

- System Setup: Assemble microfluidic reactor with precisely controlled temperature zones and real-time monitoring capabilities.

- Precursor Preparation: Prepare cadmium oleate and Se precursor solutions under inert atmosphere.

- Flow Synthesis: Implement dynamic flow experiments with continuous parameter variation (residence time: 10-300s; temperature: 120-260°C).

- In-line Characterization: Monitor optical properties continuously using inline UV-Vis and periodic photoluminescence measurements.

- Material Collection: Collect samples at steady-state conditions for ex-situ characterization.

- Multi-property Analysis:

- Structural characterization via TEM and XRD

- Optical property assessment through absorbance and emission spectroscopy

- Surface chemistry analysis using FTIR and XPS

- Sustainability Metrics: Quantify chemical consumption, energy input, and waste generation per data point obtained.

This protocol enables rapid exploration of synthesis parameter spaces while simultaneously characterizing multiple functional properties. The dynamic flow approach reduces chemical consumption by at least an order of magnitude compared to conventional batch methods, contributing significantly to more sustainable materials development [24].

Protocol 2: Multi-Functional Assessment of Hybrid Materials

This protocol provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating the multi-functional performance of organic-inorganic hybrid materials, with emphasis on interfacial interactions and synergistic effects [28] [29].

Materials and Equipment:

- Hybrid material samples

- Universal testing machine

- Electrochemical impedance spectrometer

- TGA/DSC system

- Surface area and porosity analyzer

- Environmental degradation chamber

Procedure:

- Interfacial Characterization:

- Analyze hybrid interface using FTIR and XPS to determine bond type (Class I/II)

- Examine morphology and domain size through SEM and TEM

- Quantify interfacial area through BET measurements

Mechanical Property Assessment:

- Conduct tensile tests to determine strength and elongation at break

- Perform nanoindentation for hardness and modulus measurement

- Evaluate fracture toughness through appropriate methods

Functional Performance Evaluation:

- Assess electrical/ionic conductivity via impedance spectroscopy

- Determine thermal stability using TGA (up to 800°C)

- Evaluate optical properties through UV-Vis-NIR spectroscopy

Sustainability and Durability Testing:

- Subject samples to accelerated environmental aging

- Assess recyclability and reusability potential

- Quantify embodied energy and carbon footprint

This comprehensive protocol enables researchers to move beyond single-property optimization and evaluate the complex trade-offs and synergies that define multi-functional material systems. The emphasis on interfacial characterization provides critical insights into the fundamental mechanisms governing property enhancements in hybrid systems [28] [29].

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

Multi-Functional Materials Development Workflow

Diagram Title: Multi-Functional Materials Development Workflow

Dynamic Flow Experimentation Setup

Diagram Title: Dynamic Flow Experimentation Setup

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Multi-Functional Inorganic Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function | Multi-Functional Role | Sustainability Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) [29] | Sol-gel precursor | Creates inorganic networks in hybrids | Low temperature processing, versatile chemistry |

| CdO/Se precursors [24] | Quantum dot synthesis | Tunable optoelectronic properties | Flow synthesis reduces consumption |

| Polylactic acid (PLA) [29] | Polymer matrix | Biodegradable composite component | Renewable sourcing, compostable |

| MXenes [27] | 2D conductive filler | Electrically conductive composites | Abundant precursors, tunable chemistry |

| Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [27] | Porous scaffolds | Gas capture, energy storage | High surface area, design flexibility |

| Polyaniline (PANI) [30] | Conducting polymer | Sensor platforms, hybrid composites | Green synthesis approaches available |

| Cerate compounds [26] | Corrosion inhibition | Self-healing coatings | Non-toxic chromate alternative |

| Hydroxyapatite (nHA) [29] | Bioactive filler | Biomedical scaffolds, composites | Biocompatible, biomimetic |

The experimental comparison presented in this guide demonstrates significant convergence in strategies for developing high-performance inorganic materials that successfully balance multiple functional constraints with sustainability imperatives. Autonomous experimentation methodologies, particularly dynamic flow approaches, provide unprecedented efficiency in exploring complex synthesis parameter spaces while dramatically reducing resource consumption. The systematic evaluation of organic-inorganic hybrid systems reveals the critical importance of interfacial design in achieving synergistic property enhancements that transcend the capabilities of individual components.

The integration of computational guidance with high-throughput experimental validation continues to accelerate progress in this domain, enabling researchers to navigate multi-objective optimization problems with increasing sophistication. As these methodologies mature, they promise to transform materials development from a sequential, single-property focused endeavor to an integrated process that simultaneously addresses performance, sustainability, and scalability requirements. This holistic approach is essential for developing the next generation of inorganic materials needed to address complex global challenges in energy, environment, and advanced manufacturing.

Bridging the Digital-Physical Divide: Synthesis and Characterization Workflows

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into inorganic materials research has catalyzed a paradigm shift, transitioning the discovery process from empirical, trial-and-error experimentation to a computationally driven, predictive science. AI models, particularly generative models and large language models (LLMs), have demonstrated a remarkable capacity to propose novel, stable inorganic structures with targeted properties, from thermoelectrics to perovskite oxides [31]. However, a significant bottleneck persists in the research workflow: effectively translating these AI-generated virtual structures into viable, laboratory-tested materials. This crucial step of interpreting AI output and formulating a corresponding synthesis plan remains a frontier challenge. The central thesis of modern inorganic materials research is that the true value of AI-generated designs is only realized upon experimental validation, a process that requires not just accurate property prediction but also a scientifically grounded pathway to synthesis. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the AI tools and methodologies designed to bridge this gap, equipping researchers with the knowledge to move seamlessly from digital discovery to physical reality.

Comparative Analysis of AI Approaches for Materials Discovery and Synthesis

The landscape of AI tools for materials science is diverse, ranging from single-task models to integrated autonomous systems. The following table summarizes the core capabilities of different AI approaches relevant to the discovery and synthesis pipeline.

Table 1: Comparison of AI Approaches in Inorganic Materials Research

| AI Approach / Model | Primary Function | Synthesis Planning Capability | Key Strengths | Experimental Integration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SparksMatter [31] | Multi-agent autonomous discovery | Indirect, via workflow planning and critique | Generates novel, stable structures; iterative self-improvement; high novelty & scientific rigor | High; designs workflows and suggests validation steps |

| Generative Models (e.g., MatterGen) [31] | Novel material structure generation | Limited | Explores vast chemical spaces; targets specific properties | Low; requires separate synthesis planning |

| Specialized LLMs (GPT-4, Gemini, etc.) [32] | Precursor and condition prediction | Direct, via data-augmented recall and prediction | High precursor prediction accuracy (Top-1: up to 53.8%); predicts temperatures (MAE <126°C) | Medium; provides actionable synthesis parameters |

| SyntMTE Model [32] | Synthesis parameter prediction | Direct, fine-tuned for accuracy | Lowers calcination/sintering MAE (73-98°C); reproduces experimental trends | High; provides highly accurate synthesis conditions |

| NLP Text-Mining Pipelines [33] | Extraction of synthesis recipes from literature | Provides data foundation for other models | Large-scale dataset of codified procedures (35,675+ entries) | Indirect; serves as training data for predictive models |

The performance of these models is quantifiable. For instance, general-purpose LLMs like GPT-4 and Gemini 2.0 Flash can achieve a Top-1 accuracy of up to 53.8% and a Top-5 accuracy of 66.1% in predicting precursors for a held-out set of inorganic reactions [32]. Their mean absolute error (MAE) in predicting calcination and sintering temperatures is below 126°C, a performance that matches specialized regression methods. When fine-tuned on a large, generated dataset, specialized models like SyntMTE can reduce these errors further, achieving an MAE of 73°C for sintering and 98°C for calcination temperatures [32]. In design tasks, multi-agent systems like SparksMatter have been shown to outperform tool-less LLMs like GPT-4 and O3-deep-research, achieving significantly higher scores in relevance, novelty, and scientific rigor as assessed by blinded evaluators [31].

Experimental Protocols for AI Output Validation

Transitioning from an AI-proposed material to a characterized sample requires a multi-stage experimental protocol. The following workflow diagram outlines the critical steps for validating AI-generated inorganic materials, from initial computational checks to final laboratory synthesis.

Phase 1: Computational Validation and Synthesis Planning

Objective: To verify the stability and properties of the AI-generated structure in silico and formulate an initial synthesis plan.

Methodology:

- Structure Validation: Use density functional theory (DFT) calculations to confirm the thermodynamic stability of the proposed structure. Key metrics include energy above hull (should be ≤ 50 me/atom for likely stability) and phonon dispersion (absence of imaginary frequencies) [31] [34].

- Property Prediction: Employ machine-learned force fields or DFT to predict key functional properties (e.g., band gap, elastic moduli, ionic conductivity) to ensure they meet the design target [31].

- Synthesis Planning: Input the validated material composition into a synthesis prediction model.

- Protocol A (LLM-Based): Use a general or specialized LLM (e.g., GPT-4, SyntMTE) to predict a list of likely solid-state or solution-based precursors and critical synthesis parameters such as calcination temperature (expected MAE: ~98°C) and sintering temperature (expected MAE: ~73°C) [32].

- Protocol B (Literature-Based): Query a text-mined synthesis database [33] to find analogous synthesis procedures for materials with similar compositions or crystal structures. This provides heuristic guidance and established chemical pathways.

Phase 2: Laboratory Synthesis and Characterization

Objective: To synthesize the material in the lab and characterize its structure and properties.

Methodology:

- Synthesis:

- Solid-State Reaction: Based on the AI-predicted parameters, mix precursor powders, pelletize, and heat in a furnace. The process should follow a ramp-and-hold profile with the predicted temperatures and durations, adjusted for known furnace and precursor characteristics [32] [35].

- Solution-Based Synthesis: For coprecipitation, sol-gel, or hydrothermal methods, follow the procedural sequence (mixing, heating, cooling, drying) extracted from literature-derived datasets [33]. Precursor concentrations and pH should be controlled as per the predicted recipe.

- Characterization:

- X-Ray Diffraction (XRD): To confirm the crystal structure and phase purity of the synthesized product. The experimental XRD pattern should be compared with the pattern simulated from the AI-generated model.

- Electron Microscopy (SEM/TEM): To analyze the material's morphology, grain size, and microstructure.

- Property Measurement: Conduct relevant functional tests (e.g., electrical conductivity, Seebeck coefficient, capacity) to compare with the AI-predicted properties.

Successfully navigating the AI-to-lab pipeline requires a suite of computational and experimental tools. The following table details key resources.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Resources for AI-Driven Materials Research

| Category | Resource | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Databases | The Materials Project [31] | Repository of known and computed crystal structures and properties for validation and precursor lookup. |

| Text-Mined Synthesis Datasets [33] | Provides structured, large-scale data on solution-based and solid-state synthesis procedures for training and heuristic planning. | |

| AI Models & Tools | Multi-Agent Systems (SparksMatter) [31] | For end-to-end autonomous hypothesis generation, structure design, and workflow planning. |

| Generative Models (MatterGen) [31] | For generating novel, stable inorganic structures conditioned on target properties. | |

| Fine-Tuned Prediction Models (SyntMTE) [32] | For obtaining accurate synthesis parameters like precursor lists and thermal treatment temperatures. | |

| Laboratory Reagents | High-Purity Inorganic Precursors | Essential for both solid-state and solution-based synthesis to avoid impurity phases. |

| Structure-Directing Agents/Solvents | Critical for solution-based synthesis (e.g., sol-gel, hydrothermal) to control solution conditions and final morphology [33]. |

The journey from AI-generated structure to a tangible material in the laboratory is complex but increasingly navigable thanks to a new generation of AI tools. As the comparative analysis shows, the field is moving beyond pure structure generation towards integrated systems that encompass planning, validation, and synthesis prediction. The critical differentiator among tools is their capacity for scientifically grounded reasoning and integration of domain knowledge, which directly impacts the experimental feasibility of their outputs.

Future progress hinges on several key developments. First, the creation of larger and more diverse synthesis databases [33] will continue to enhance the accuracy of models like SyntMTE. Second, the tight integration of multi-agent reasoning with high-throughput automated laboratories will close the feedback loop, allowing AI systems to not only propose but also physically execute and learn from synthesis experiments [31]. Finally, as models become more complex, evaluation frameworks that rigorously assess the faithfulness, relevance, and accuracy of their outputs will be paramount for building researcher trust [36]. For researchers and development professionals, the path forward involves a synergistic approach: leveraging the generative power of models like SparksMatter for discovery, while relying on the specialized predictive accuracy of synthesis models to create a reliable and efficient bridge to the laboratory.

Advanced Synthesis Techniques for Novel Inorganic Compounds

The discovery and synthesis of novel inorganic compounds are fundamental to advancements in energy, electronics, and medicine. Traditional synthesis, reliant on trial-and-error and researcher intuition, has long been a bottleneck, often taking months or even years for a single material [37]. However, a transformative shift is underway. The integration of machine learning (ML), high-throughput robotics, and computational guidance is creating a new paradigm for inorganic synthesis. This guide objectively compares these emerging techniques against traditional methods, framing the analysis within the broader thesis of experimental validation in materials research. By comparing performance data, detailing experimental protocols, and outlining essential research tools, this article provides scientists and developers with a clear framework for selecting and implementing advanced synthesis strategies.

Comparative Analysis of Synthesis Techniques

The following techniques represent the forefront of inorganic materials synthesis. Their performance can be quantitatively compared across several key metrics, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Advanced Inorganic Synthesis Techniques

| Synthesis Technique | Reported Success Rate/Improvement | Throughput | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Synthesizability Prediction (e.g., SynthNN) | 7x higher precision in identifying synthesizable materials than DFT-based formation energy [1] | High (computational screening of billions of candidates) [1] | Learns complex chemical principles from data without prior knowledge [1] | Requires large datasets of known materials; predicts feasibility, not specific conditions [1] |

| Robotic Laboratory Synthesis | Higher phase purity for 32 out of 35 target materials (91%) [38] | 224 reactions in weeks (vs. months/years manually) [38] | Unattended, precise execution and rapid experimental validation [38] | High initial capital investment; requires specialized programming and maintenance |

| ML-Guided Optimization (e.g., CVD) | Area Under ROC Curve (AUROC) of 0.96 for predicting successful growth [39] | Adaptive models reduce the number of required trials [39] | Quantifies and ranks the importance of synthesis parameters [39] | Performance depends on quality and size of initial training dataset [39] |

| Traditional Solid-State Reaction | N/A (Established baseline) | Low (days of heating, repeated grinding) [37] | Produces highly crystalline, stable materials [37] | Low control over particle size; often yields thermodynamically stable phases only [37] |

Detailed Techniques and Experimental Protocols

Computational Synthesizability Prediction with SynthNN

This technique uses deep learning to predict whether a hypothetical inorganic chemical composition is synthesizable, acting as a powerful pre-screening filter before experimental work begins.

Experimental Protocol:

- Model Architecture: A deep learning model (SynthNN) is built using an

atom2vecframework. This framework represents each chemical formula via a learned atom embedding matrix that is optimized alongside other neural network parameters, allowing the model to learn optimal descriptors for synthesizability directly from data [1]. - Data Preparation: The model is trained on positive examples from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), which contains known synthesized crystalline materials. These are augmented with a larger set of artificially generated, "unsynthesized" compositions. The ratio of artificial to real formulas is a key hyperparameter (N_synth) [1].

- Training: A semi-supervised Positive-Unlabeled (PU) learning approach is employed. This method treats the artificially generated examples as unlabeled data and probabilistically reweights them according to their likelihood of being synthesizable, accounting for the fact that some might be synthesizable but not yet reported [1].

- Validation: Model performance is benchmarked against baseline methods like random guessing and the charge-balancing criterion. It is evaluated on its precision in classifying known synthesized materials as synthesizable and artificially generated ones as not [1].

Robotic High-Throughput Synthesis and Validation

This approach uses automated robotic laboratories to execute and analyze many synthesis reactions in parallel, drastically accelerating the experimental cycle.

Experimental Protocol:

- Precursor Selection: A modern approach involves selecting precursor powders based on analyzing phase diagrams to avoid unwanted pairwise reactions between precursors that lead to impurities [38].

- Automated Synthesis: The selected precursors are robotically weighed, mixed, and dispensed into reaction vessels (e.g., crucibles). The robotic system (e.g., the ASTRAL lab) places the vessels in high-temperature furnaces under programmed atmospheric conditions [38].

- In-Line Characterization: After synthesis, the robotic system automatically transports the samples to characterization instruments. X-ray diffraction (XRD) is typically used for high-throughput phase identification and assessment of phase purity [38].

- Data Analysis: The characterization data (e.g., XRD patterns) are automatically analyzed to quantify the yield of the target material versus impurity phases. The success of a synthesis is determined by the percentage of the target phase in the final product [38].

Machine Learning-Guided Optimization of Synthesis Parameters

For established synthesis methods like Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD), ML models can map complex, non-linear relationships between synthesis parameters and outcomes to recommend optimal conditions.

Experimental Protocol (for CVD-grown MoS₂):

- Dataset Curation: Historical synthesis data (e.g., 300 experiments from lab notebooks) are compiled. Each data point includes synthesis parameters (features) and a binary outcome (label), such as "Can grow" (sample size >1 μm) or "Cannot grow" [39].

- Feature Engineering: Non-informative or fixed parameters are eliminated. The final feature set for MoS₂ CVD included distance of S outside furnace, gas flow rate, ramp time, reaction temperature, reaction time, addition of NaCl, and boat configuration [39].

- Model Training and Selection: Several classifier models (e.g., XGBoost, Support Vector Machine) are trained and evaluated using nested cross-validation to prevent overfitting. The best-performing model (XGBoost-C, with an AUROC of 0.96) is selected for interpretation and prediction [39].

- Interpretation and Optimization: The SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) method is applied to the trained model to quantify the importance of each synthesis parameter. The model is then used to predict the probability of success for unexplored combinations of parameters, recommending the most favorable conditions for experimentation [39].

Diagram 1: Integrated mat discovery workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of advanced synthesis requires specific reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions used in the featured experiments.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced Inorganic Synthesis

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Powders | Raw materials containing the target elements that react to form the final compound. Selection is critical for purity [38]. | Solid-state synthesis of oxide materials for batteries and catalysts [38]. |

| Atom2Vec Embeddings | A learned numerical representation of chemical elements that helps ML models understand chemical similarity and interactions [1]. | Featuring in deep learning models (SynthNN) for predicting synthesizability [1]. |

| Charge-Balancing Filter | A heuristic filter that checks if a composition can achieve net neutral charge with common oxidation states; a baseline for ML models [1] [40]. | A initial, fast screen in computational material screening pipelines [40]. |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | A game-theoretic method to interpret the output of ML models, quantifying the contribution of each input feature to the prediction [39]. | Interpreting an XGBoost model to rank the importance of CVD parameters like gas flow rate and temperature [39]. |