Fine-Tuning Strategies for Materials Foundation Models: A Guide for Biomedical and Clinical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on fine-tuning materials foundation models.

Fine-Tuning Strategies for Materials Foundation Models: A Guide for Biomedical and Clinical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on fine-tuning materials foundation models. Foundation models, pre-trained on vast and diverse atomistic datasets, offer a powerful starting point for simulating complex biological and materials systems. We explore the core concepts of these models and detail targeted fine-tuning strategies that achieve high accuracy with minimal, system-specific data. The article covers practical methodologies, including parameter-efficient fine-tuning and integrated software platforms, addresses common challenges like catastrophic forgetting and data scarcity, and presents rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing the latest research, this guide aims to empower scientists to reliably adapt these advanced AI tools for applications in drug discovery, biomaterials development, and clinical pharmacology.

What Are Materials Foundation Models and Why Fine-Tune Them?

The field of atomistic simulation is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by the emergence of AI-based foundation models. These models represent a fundamental shift from traditional, narrowly focused machine-learned interatomic potentials (MLIPs) towards large-scale, pre-trained models that capture the broad principles of atomic interactions across chemical space. The core idea is to leverage data and parameter scaling laws, inspired by the success of large language models, to create a foundational understanding of chemistry and materials that can be efficiently adapted to a wide range of downstream tasks with minimal additional data [1]. This paradigm separates the costly representation learning phase from application-specific fine-tuning, offering unprecedented efficiency and transferability compared to training models from scratch for each new system [1] [2].

A critical distinction must be made between universal potentials and true foundation models. Universal potentials, such as MACE-MP-0, are models trained to be broadly applicable force fields for systems across the periodic table, typically at one level of theory [1] [2]. While immensely valuable, they are supervised to perform one specific task: predict energy and force labels. A true atomistic foundation model, in contrast, exhibits three defining characteristics: (1) superior performance across diverse downstream tasks compared to task-specific models, (2) compliance with heuristic scaling laws where performance improves with increased model parameters and training data, and (3) emergent capabilities—solving tasks that appeared impossible at smaller scales, such as predicting higher-quality CCSD(T) data from DFT training data [1].

Architectural Foundations and Key Models

Atomistic foundation models are built on geometric machine learning architectures that inherently respect the physical symmetries of atomic systems, including translation, rotation, and permutation invariance. Most current models employ graph neural network (GNN) architectures where atoms represent nodes and bonds represent edges in a graph [3] [2]. These models incorporate increasingly sophisticated advancements including many-body interactions, equivariant features, and transformer-like architectures to capture complex atomic environments [2].

Table 1: Prominent Atomistic Foundation Models and Their Specifications

| Model | Release Year | Parameters | Training Data Size | Primary Training Objective |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MACE-MP-0 | 2023 | 4.69M | 1.58M structures | Energy, forces, stress |

| GNoME | 2023 | 16.2M | 16.2M structures | Energy, forces |

| MatterSim-v1 | 2024 | 4.55M | 17M structures | Energy, forces, stress |

| ORB-v1 | 2024 | 25.2M | 32.1M structures | Denoising + energy, forces, stress |

| JMP-L | 2024 | 235M | 120M structures | Energy, forces |

| EquiformerV2-M | 2024 | 86.6M | 102M structures | Energy, forces, stress |

These models learn robust, transferable representations of atomic environments through pre-training on massive, diverse datasets comprising inorganic crystals, molecular systems, reactive mixtures, and more [4]. The training incorporates careful homogenization of reference energies and uniform treatment of dispersion corrections to ensure consistency across chemical space [4].

Fine-Tuning Methodologies and Protocols

Frozen Transfer Learning Protocol

The "frozen transfer learning" approach has emerged as a particularly effective fine-tuning strategy for atomistic foundation models. This method involves controlled freezing of neural network layers during fine-tuning, where parameters in specific layers remain fixed while only a subset of layers are updated [3].

Application Protocol: Implementing Frozen Transfer Learning

Foundation Model Selection: Choose an appropriate pre-trained model (e.g., MACE-MP "small," "medium," or "large") based on your computational resources and accuracy requirements [3].

Layer Freezing Strategy: Implement a progressive unfreezing approach:

- Freeze all layers except the readout functions (designated as f6 configuration)

- Gradually unfreeze deeper layers: product layer (f5), then interaction parameters (f4)

- Empirical studies show optimal performance typically with 4 frozen layers (f4 configuration) [3]

Data Preparation: Curate a task-specific dataset of atomic structures with corresponding target properties (energies, forces). For reactive surface chemistry, several hundred configurations often suffice [3].

Model Training:

- Utilize specialized software implementations such as the mace-freeze patch for the MACE software suite [3]

- Maintain the original model architecture while restricting gradient computation to non-frozen layers

- Employ standard optimization techniques (Adam, L-BFGS) with reduced learning rates for fine-tuning

Validation: Assess performance on held-out configurations, comparing energy and force root mean squared error (RMSE) against both the foundation model and from-scratch trained models [3].

This protocol demonstrates remarkable data efficiency, with frozen transfer learned models achieving accuracy comparable to from-scratch models trained on 5x more data [3]. For instance, MACE-MP-f4 models trained on just 20% of a dataset (664 configurations) showed similar accuracy to from-scratch models trained on the entire dataset (3376 configurations) [3].

Integrated Fine-Tuning Platforms

Comprehensive platforms like MatterTune provide integrated environments for fine-tuning atomistic foundation models. MatterTune offers a modular framework consisting of four core components: a model subsystem, data subsystem, trainer subsystem, and application subsystem [2]. This platform supports multiple state-of-the-art foundation models including ORB, MatterSim, JMP, MACE, and EquiformerV2, enabling researchers to fine-tune models for diverse materials informatics tasks beyond force fields, such as property prediction and materials screening [2].

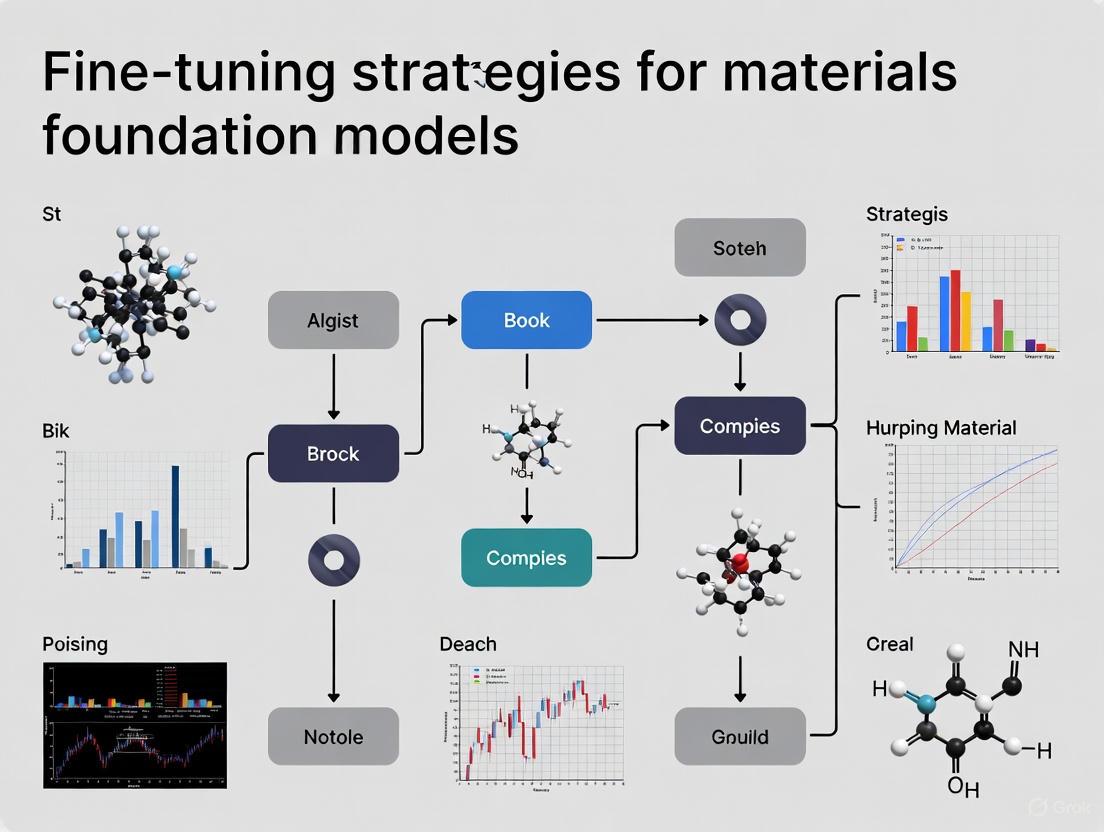

Foundation Model Fine-Tuning Workflow

Experimental Validation and Performance Metrics

Quantitative Performance Assessment

Rigorous benchmarking establishes the accuracy and domain of universality for fine-tuned foundation models. Large-scale assessments across thousands of materials show that leading models can reproduce energies, forces, lattice parameters, elastic properties, and phonon spectra with remarkable accuracy [4].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Fine-Tuned Foundation Models on Challenging Datasets

| System | Fine-Tuning Method | Training Data Size | Energy RMSE | Force RMSE | Comparative Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H₂/Cu surfaces | MACE-MP-f4 (frozen) | 664 configurations (20%) | < 5 meV/atom | ~30 meV/Å | Matches from-scratch model trained on 3376 configurations [3] |

| Ternary alloys | MACE-MP-f4 (frozen) | 10-20% of full dataset | Comparable to full training | Comparable to full training | Achieves similar accuracy with 80-90% less data [3] |

| Various materials | UMLPs fine-tuned | System-specific | ~0.044 eV/atom (formation energies) | Several meV/Å | Reproduces DFT-level accuracy for diverse properties [4] |

For particularly challenging properties like mixing enthalpies in alloys, where small energy differences are critical, foundation models fine-tuned with system-specific data can correct initial errors and restore correct thermodynamic trends [4]. Similarly, for surface systems—typically underrepresented in broad training sets—targeted fine-tuning significantly reduces errors correlated with descriptor-space distance from the original training data [4].

Advanced Adaptation Strategies

Beyond basic fine-tuning, several advanced adaptation strategies enhance foundation model performance:

Predictor-Corrector Fine-Tuning: Pre-trained universal machine-learned potentials provide robust initializations, and fine-tuning rapidly improves accuracy on task-specific datasets, often outperforming models trained from scratch and reducing outlier errors in lattice parameters, defect energies, and elastic constants [4].

Active Learning Integration: In global optimization and structure search, the combination of a universal surrogate with sparse Gaussian Process Regression models enables iterative, on-the-fly improvement. This approach, coupled with structure search algorithms like replica exchange, leads to robust identification of DFT global minima even in challenging systems [4].

Multi-Head Fine-Tuning: This approach maintains transferability across systems represented in the original pre-training dataset while allowing training on data from multiple levels of electronic structure theory, addressing the challenge of catastrophic forgetting during fine-tuning [3].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Implementation

Table 3: Key Software and Computational Tools for Atomistic Foundation Models

| Tool/Platform | Type | Primary Function | Supported Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| MatterTune | Fine-tuning platform | Modular framework for fine-tuning atomistic FMs | ORB, MatterSim, JMP, MACE, EquiformerV2 [2] |

| MACE software suite | MLIP infrastructure | Training and fine-tuning MACE-based models | MACE-MP and variants [3] |

| mace-freeze patch | Specialized tool | Implements frozen transfer learning for MACE | MACE-MP foundation models [3] |

| MedeA Environment | Commercial platform | Integrated workflows for MLP generation and application | VASP-integrated MLPs [5] [6] |

| ALCF Supercomputers | HPC infrastructure | Large-scale training of foundation models | Custom models (e.g., battery electrolytes) [7] |

Atomistic Foundation Model Research Ecosystem

The development of atomistic foundation models represents a paradigm shift in computational materials science and chemistry. By distinguishing these models from mere universal potentials and establishing robust fine-tuning protocols, researchers can leverage their full potential as adaptable, specialized tools. The frozen transfer learning methodology, in particular, offers a data-efficient pathway to achieving chemical accuracy for challenging systems like reactive surfaces and complex alloys.

Future developments will likely focus on enhanced architectural principles incorporating explicit long-range interactions and polarizability [4], more sophisticated continual learning approaches to prevent catastrophic forgetting, and improved benchmarking across diverse chemical domains. As these models continue to evolve, they promise to dramatically accelerate materials discovery and molecular design across pharmaceuticals, energy storage, and beyond [8] [9] [7].

The development of Foundation Models (FMs) represents a paradigm shift across scientific domains, from atomistic simulations in materials science to biomarker detection in oncology. These large-scale, pretrained models achieve remarkable generalization by learning universal representations from extensive datasets. However, a fundamental challenge emerges: the accuracy-transferability trade-off. This core conflict arises when enhancing a model's accuracy for a specific, high-fidelity task compromises its performance across diverse, out-of-distribution scenarios. In materials science, FMs pretrained on millions of generalized gradient approximation (GGA) density functional theory (DFT) calculations demonstrate high transferability but exhibit consistent systematic errors, such as energy and force underprediction [10]. Conversely, migrating these models to higher-accuracy functionals like meta-GGAs (e.g., r2SCAN) improves accuracy but introduces transferability challenges due to significant energy scale shifts and poor label correlation between fidelity levels [10]. Understanding and managing this trade-off is critical for deploying robust FMs in real-world research and development, where both precision and adaptability are required.

Quantitative Benchmarking of the Trade-off

The accuracy-transferability trade-off manifests quantitatively across different domains. The following tables summarize key performance metrics from recent studies, highlighting the performance gaps between internal and external validation, a key indicator of transferability.

Table 1: Performance of a Fine-Tuned Pathology Foundation Model (EAGLE) for EGFR Mutation Detection in Lung Cancer [11]

| Validation Setting | Dataset Description | Area Under the Curve (AUC) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Validation | 1,742 slides from MSKCC | 0.847 | Baseline performance on primary samples was higher (AUC 0.90) |

| External Validation | 1,484 slides from 4 institutions | 0.870 | Demonstrates strong generalization across hospitals and scanners |

| Prospective Silent Trial | Novel primary samples | 0.890 | Confirms real-world clinical utility and robust transferability |

Table 2: Multi-Fidelity Data Challenges in Materials Foundation Models [10]

| Data Fidelity Level | Typical Formation Energy MAE | Key Advantages | Key Limitations for Transferability |

|---|---|---|---|

| GGA/GGA+U (Low) | ~194 meV/atom [10] | Computational efficiency, large dataset availability | Limited transferability across bonding environments; noisy data from empirical corrections |

| r2SCAN (Meta-GGA, High) | ~84 meV/atom [10] | Higher general accuracy for strongly bound compounds | High computational cost, limited data scale, energy scale shifts hinder transfer from GGA |

Table 3: Comparison of Learning Techniques for Few-Shot Adaptation [12]

| Learning Technique | Within-Distribution Performance | Out-of-Distribution Performance | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fine-Tuning | Good | Better | Learns more diverse and discriminative features |

| MAML | Better | Good | Specializes for fast adaptation on similar data distributions |

| Reptile | Better | Good | Similar to MAML; specializes for the training distribution |

Experimental Protocols for Managing the Trade-off

Protocol: Cross-Functional Transfer Learning for Materials FMs

This protocol outlines a method to bridge a pre-trained GGA model to a high-fidelity r2SCAN dataset, addressing the energy shift challenge [10].

1. Pre-Trained Model and Target Dataset Acquisition:

- Research Reagent: A foundation model pre-trained on a large-scale GGA/GGA+U dataset (e.g., CHGNet, M3GNet).

- Research Reagent: A high-fidelity target dataset (e.g., MP-r2SCAN) with consistent labels (energy, forces, stresses).

- Procedure: Acquire the pre-trained model weights and the target dataset. Perform a correlation analysis between the GGA and high-fidelity labels (e.g., r2SCAN energies) to quantify the distribution shift.

2. Elemental Energy Referencing:

- Research Reagent: Isolated elemental reference energies calculated at both the low-fidelity (GGA) and high-fidelity (r2SCAN) levels of theory.

- Procedure: Calculate the systematic energy shift per chemical element between the two fidelity levels. Apply this per-element shift to the pre-trained model's output or the target labels to align the energy scales before fine-tuning.

3. Model Fine-Tuning:

- Research Reagent: High-performance computing cluster with GPU acceleration.

- Procedure: Initialize the model with pre-trained weights. Freeze a significant portion of the initial layers to preserve general features. Fine-tune the later, more task-specific layers on the energy-referenced high-fidelity dataset using a low learning rate and a suitable loss function (e.g., Mean Absolute Error for energies).

4. Validation and Analysis:

- Procedure: Validate the fine-tuned model on a held-out test set from the high-fidelity data. Perform an out-of-distribution test on material systems not present in the fine-tuning set to evaluate retained transferability. Analyze the scaling law to confirm data efficiency gains from transfer learning.

Protocol: Fine-Tuning a Pathology FM for Clinical Biomarker Detection

This protocol details the development of EAGLE, a computational biomarker for EGFR mutation detection in lung cancer, demonstrating a successful real-world application that balances accuracy and transferability [11].

1. Foundation Model and Dataset Curation:

- Research Reagent: An open-source pathology foundation model (e.g., pre-trained on a large corpus of whole slide images).

- Research Reagent: A large, international cohort of digitized H&E-stained lung adenocarcinoma slides (N=8,461 slides from 5 institutions), with corresponding ground truth EGFR mutation status from genomic sequencing.

- Procedure: Curate the dataset, ensuring slides are from multiple institutions and scanned with different scanners to build in diversity. Split data into training (e.g., 5,174 slides), internal validation (e.g., 1,742 slides), and multiple external test sets.

2. Weakly-Supervised Fine-Tuning:

- Research Reagent: High-performance computing environment with substantial GPU memory for processing whole slide images.

- Procedure: Employ a multiple-instance learning framework. Divide whole slide images into smaller tiles. Fine-tune the foundation model using a weakly supervised approach, where only the slide-level label (EGFR mutant/wild-type) is required, eliminating the need for manual, pixel-level annotations.

3. Multi-Cohort Validation:

- Procedure: Evaluate the fine-tuned model on the internal validation set and multiple external test cohorts from different hospitals and geographic locations. Calculate the Area Under the Curve to assess accuracy.

4. Prospective Silent Trial:

- Procedure: Deploy the validated model in a real-time, prospective setting on new, consecutive patient samples. Run the model "silently" without impacting clinical decision-making to confirm its performance and transferability in a true real-world workflow. Analyze clinical utility, such as the potential reduction in rapid molecular tests.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Fine-Tuning Foundation Models

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function & Application | Examples & Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-Trained Foundation Models | Provides a base of generalizable features for transfer learning, drastically reducing data and compute needs for new tasks. | - CHGNet/M3GNet: For atomistic simulations of materials [10].- Evo 2: For multi-scale biological sequence analysis and design [13].- Pathology FMs: Pre-trained on vast slide libraries for computational pathology [11]. |

| High-Fidelity Target Datasets | Serves as the ground truth for fine-tuning, enabling the model to achieve higher accuracy on a specific task. | - MP-r2SCAN: High-fidelity quantum mechanical data for materials [10].- Multi-institutional Biobanks: Clinically annotated medical images with genomic data [11]. |

| Specialized Software Platforms | Optimizes the training, fine-tuning, and deployment of large foundation models, particularly on biological and chemical data. | - NVIDIA BioNeMo: Offers optimized performance for biological and chemical model training/inference [13]. |

| Elemental Reference Data | Critical for aligning energy scales in multi-fidelity learning for materials science, mitigating negative transfer. | - Isolated Elemental Energies: Calculated at both low- and high-fidelity levels of theory (e.g., GGA and r2SCAN) [10]. |

The accuracy-transferability trade-off is an inherent property of foundation models, but it is not insurmountable. The protocols and data presented demonstrate that strategic fine-tuning—informed by domain knowledge and robust validation—can yield models that excel in both high-accuracy tasks and out-of-distribution generalization. Key to this success is the use of techniques like elemental energy referencing for materials FMs and multi-institutional, weakly-supervised fine-tuning for medical FMs. Future research should focus on improving multi-fidelity learning algorithms, developing more standardized and expansive benchmarking datasets, and creating more flexible model architectures that can dynamically adapt to data from different distributions. By systematically addressing this core challenge, foundation models will fully realize their potential as transformative tools in scientific discovery and industrial application.

Foundation models for materials science, pre-trained on extensive datasets encompassing diverse chemical spaces, have emerged as powerful tools for initial atomistic simulations [3] [8]. However, their generalist nature often comes at the cost of precision, and they can lack the chemical accuracy required to reliably predict critical system-specific properties such as reaction barriers, phase transition dynamics, and material stability [3] [14]. Fine-tuning has established itself as the pivotal paradigm for bridging this accuracy gap. This process adapts a broad foundation model to a specific chemical system or property, achieving quantitative, often near-ab initio, accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency and requiring significantly less data than training a model from scratch [14].

Recent systematic benchmarks demonstrate that fine-tuning is a universal strategy that transcends model architecture. Evaluations across five leading frameworks—MACE, GRACE, SevenNet, MatterSim, and ORB—reveal consistent and dramatic improvements after fine-tuning on specialized datasets [14]. The adaptation process effectively unifies the performance of these diverse architectures, enabling them to accurately reproduce system-specific physical properties that foundation models alone fail to capture [14].

Quantitative Efficacy of Fine-Tuning

The transformative impact of fine-tuning is quantitatively demonstrated across multiple studies and model architectures. The following table summarizes key performance metrics reported in recent literature.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Gains from Fine-Tuning Foundation Models

| Model / Framework | System Studied | Key Performance Improvement | Data Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| MACE-freeze (f4) [3] | H₂ dissociation on Cu surfaces | Achieved accuracy of from-scratch model with only 20% of training data (664 vs. 3376 configs) [3] | High |

| Multi-Architecture Benchmark [14] | 7 diverse chemical systems | Force errors reduced by 5-15x; Energy errors improved by 2-4 orders of magnitude [14] | High |

| MACE-MP Foundation Model [3] | Tertiary alloys & surface chemistry | Fine-tuned model with hundreds of datapoints matched accuracy of from-scratch model trained with thousands [3] | High |

| CHGNet Fine-Tuning [3] | Not Specified | Required >196,000 structures for fine-tuning, similar to from-scratch data needs [3] | Low |

The data unequivocally shows that fine-tuning is not merely an incremental improvement but a essential step for achieving quantitative accuracy. The data efficiency is particularly noteworthy, as fine-tuning can reduce the required system-specific data by an order of magnitude or more [3] [14]. This translates directly into reduced computational cost for generating training data via expensive ab initio calculations.

Fine-Tuning Methodologies and Protocols

Several sophisticated fine-tuning methodologies have been developed to optimize performance and mitigate issues like catastrophic forgetting.

Frozen Transfer Learning

This technique involves keeping the parameters of specific layers in the foundation model fixed during further training. By freezing the early layers that capture general chemical concepts (e.g., atomic embeddings), and only updating the later, more task-specific layers (e.g., readout functions), the model retains its broad knowledge while adapting to new data [3].

Experimental Protocol: Frozen Transfer Learning with MACE (MACE-freeze) [3]

- Foundation Model Selection: Begin with a pre-trained MACE-MP model (e.g., "small," "medium," or "large").

- Layer Freezing Strategy:

- Implement the

mace-freezepatch to the MACE software suite. - The recommended configuration is MACE-MP-f4, which freezes the initial layers and allows parameters in the product layer and interaction layers to update. This has been shown to peak predictive performance [3].

- Implement the

- Training Configuration:

- Use the standard

mace_run_trainscript. - Set

--foundation_model="small"(or path to model). - Configure loss weights for energy and forces (e.g.,

--energy_weight=1.0 --forces_weight=1.0). - Utilize an adaptive learning rate scheduler, starting with a relatively low learning rate (e.g.,

--lr=0.01).

- Use the standard

- Validation: Perform k-fold cross-validation and run validation Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to ensure stability and accuracy [3].

Multihead Replay Fine-Tuning

This protocol is designed to prevent catastrophic forgetting—where the model loses performance on its original training domain—by concurrently training on the new, specialized dataset and a subset of the original foundation model's training data [15].

Experimental Protocol: Multihead Replay Fine-Tuning [15]

- Foundation Model & Data Preparation:

- Select a foundation model (e.g.,

--foundation_model="small"). - Prepare your system-specific training data (e.g.,

train.xyz). - Have a subset of the original pre-training data (e.g., from Materials Project trajectory data) available for replay.

- Select a foundation model (e.g.,

- Training Execution:

- Use the

mace_run_trainscript with the argument--multiheads_finetuning=True. - Specify the training files and standard hyperparameters. The framework automatically manages the multihead training process.

- This method is the recommended protocol for fine-tuning Materials Project foundation models as it typically produces more robust and stable models [15].

- Use the

Integrated Workflow and Visualization

The typical workflow for fine-tuning a materials foundation model, from data generation to deployment of a surrogate potential, is illustrated below. This integrated pipeline ensures both data and computational efficiency.

Diagram 1: Integrated fine-tuning workflow for MLIPs

This workflow highlights the iterative and efficient nature of the process. A key advantage is the optional final step where the fine-tuned foundation model can be used as a reliable, high-accuracy reference to generate labels for training an even more computationally efficient surrogate model, such as one based on the Atomic Cluster Expansion (ACE) [3]. This creates a powerful pipeline for large-scale or massively parallel simulations.

Table 2: Key Resources for Fine-Tuning Materials Foundation Models

| Resource Name | Type | Function & Application | Reference/Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| MACE-MP Foundation Models | Pre-trained Model | Robust, equivariant potential; a common starting point for fine-tuning on diverse materials systems. | [3] [15] |

| MatterTune Platform | Software Framework | Integrated, user-friendly platform for fine-tuning various FMs (ORB, JMP, MACE); lowers adoption barrier. | [2] |

| aMACEing Toolkit | Software Toolkit | Unified interface for fine-tuning workflows across multiple MLIP frameworks (MACE, GRACE, etc.). | [14] |

| Materials Project (MPtrj) | Dataset | A primary source of pre-training data; also used in multihead replay to prevent catastrophic forgetting. | [3] [14] |

| Multihead Replay Protocol | Training Algorithm | Mitigates catastrophic forgetting during fine-tuning by replaying original training data; recommended for MACE-MP. | [15] |

| Frozen Transfer Learning | Training Algorithm | Enhances data efficiency by freezing general-purpose layers and updating only task-specific layers. | [3] |

Fine-tuning has firmly established itself as a non-negotiable paradigm for unlocking the full potential of materials foundation models. The quantitative evidence is clear: this process transforms robust but general-purpose potentials into highly accurate, system-specific tools capable of predicting challenging properties like reaction barriers and phase behavior [3] [14]. By leveraging strategies such as frozen transfer learning and multihead replay, researchers can achieve this precision with remarkable data efficiency, overcoming a critical bottleneck in computational materials science. As unified toolkits and platforms like MatterTune and the aMACEing Toolkit continue to emerge, these advanced methodologies are becoming increasingly accessible, paving the way for their widespread adoption in accelerating materials discovery and drug development.

The integration of atomistic foundation models (FMs) is revolutionizing biomedical research by enabling highly accurate and data-efficient simulations of complex biological systems. These models, pre-trained on vast and diverse datasets, provide a robust starting point for understanding intricate biomedical phenomena. Fine-tuning strategies, such as frozen transfer learning, allow researchers to adapt these powerful models to specific downstream tasks with limited data, overcoming a significant bottleneck in computational biology and materials science [3] [2]. This article details key applications and provides standardized protocols for employing fine-tuned FMs in two critical areas: predicting protein-ligand interactions for drug discovery and designing stable, functional biomaterials.

Fine-Tuning Foundations: Core Concepts and Strategies

Foundation models for atomistic systems are typically graph neural networks (GNNs) trained on large-scale datasets like the Materials Project to predict energies, forces, and stresses from atomic structures [2]. Their strength lies in learning general, transferable representations of atomic interactions.

- Frozen Transfer Learning: This is a highly data-efficient fine-tuning method where the initial layers of a pre-trained FM are kept fixed ("frozen"), and only the later layers are updated on the new, task-specific dataset. This approach preserves the general knowledge acquired during pre-training while efficiently adapting the model to a specialized domain, achieving high accuracy with hundreds, rather than thousands, of data points [3].

- Platforms for Implementation: Frameworks like MatterTune have been developed to lower the barrier for researchers. MatterTune integrates state-of-the-art FMs (e.g., MACE, MatterSim, ORB) and provides a user-friendly interface for flexible fine-tuning and application across diverse materials informatics tasks [2].

The following workflow illustrates the typical process for fine-tuning a foundation model for a specialized biomedical application:

Fine-Tuning Workflow for Biomedical Applications

Application Note 1: Predicting Protein-Ligand Binding Dynamics

Objective: To accurately identify dynamic binding "hotspots" and predict ligand poses and affinities by integrating molecular dynamics (MD) with insights from fine-tuned FMs, thereby accelerating target and drug discovery [16] [17].

Quantitative Binding Dynamics

A large-scale analysis of 100 protein-ligand complexes provided key quantitative metrics that define stable binding interactions. These parameters are crucial for validating both MD and docking predictions [16].

Table 1: Key Quantitative Parameters for Protein-Ligand Binding Sites from MD Simulations [16]

| Parameter | Description | Median Value (Interquartile Range) |

|---|---|---|

| Binding Residue Backbone RMSD | Measures structural fluctuation of binding site residues. | 1.2 Å (0.8 Å) |

| Ligand RMSD | Measures stability of the bound ligand pose. | 1.6 Å (1.0 Å) |

| Minimum SASA of Binding Residues | Minimum solvent-accessible surface area of binding residues. | 2.68 Ų (0.43 Ų) |

| Maximum SASA of Binding Residues | Maximum solvent-accessible surface area of binding residues. | 3.2 Ų (0.59 Ų) |

| High-Occupancy H-Bonds | Hydrogen bonds with persistence >71 ns during a 100 ns MD simulation. | 86.5% of all H-bonds |

Experimental Protocol: MD Simulation for Hotspot Validation

Methodology: This protocol uses classical Molecular Dynamics (cMD) to validate the stability of a protein-ligand complex and identify dynamic hotspots, based on the workflow established by International Journal of Molecular Sciences [16].

System Preparation:

- Obtain a high-resolution co-crystal structure of the protein-ligand complex from the RCSB Protein Data Bank. Prefer structures with a resolution of <2.0 Å and without mutations in the binding pocket.

- Parameterize the ligand using standard force fields (e.g., GAFF2) with tools like

acpypeor the RESP charge method. - Solvate the complex in a triclinic water box (e.g., TIP3P water model) with a minimum 1.0 nm distance between the protein and box edge.

- Add ions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻) to neutralize the system's charge and simulate a physiological salt concentration (e.g., 0.15 M NaCl).

Simulation Setup:

- Use a molecular dynamics package such as GROMACS.

- Apply periodic boundary conditions.

- Employ a force field like AMBER99SB-ILDN or CHARMM36 for the protein.

- Set long-range electrostatics treatment using the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method.

Energy Minimization and Equilibration:

- Energy Minimization: Run steepest descent minimization until the maximum force is below 1000 kJ/mol·nm.

- NVT Equilibration: Equilibrate the system for 100 ps in the canonical ensemble (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) using a thermostat (e.g., V-rescale) at 300 K.

- NPT Equilibration: Equilibrate the system for 100 ps in the isothermal-isobaric ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) using a barostat (e.g., Berendsen) at 1 bar.

Production MD Run:

- Run a production simulation for a minimum of 100 ns. Save atomic coordinates every 10 ps for analysis.

Data Analysis:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Calculate the backbone RMSD for the entire protein, the binding site residues, and the ligand to assess stability.

- Hydrogen Bond Occupancy: Use a tool like

gmx hbondin GROMACS to compute the existence matrix of H-bonds between binding residues and the ligand. Classify occupancy as low (0-30 ns), moderate (31-70 ns), or high (71-100 ns). - Solvent-Accessible Surface Area (SASA): Calculate the SASA for binding site residues to understand their exposure and interaction with the solvent and ligand.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Protein-Ligand Interaction Analysis

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Software for Protein-Ligand Studies

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | A versatile package for performing MD simulations. | Used for the energy minimization, equilibration, and production MD runs in the protocol above [16]. |

| HAMD | An alternative MD engine for simulating biomolecular systems. | Can be used for simulating large complexes or specific force fields. |

| Force Fields (AMBER, CHARMM) | Parameter sets defining potential energy functions for atoms. | Provides the physical rules for atomic interactions during the simulation (e.g., AMBER99SB-ILDN) [16]. |

| GAFF2 (Generalized Amber Force Field 2) | A force field for small organic molecules. | Used for parameterizing drug-like ligands in the protein-ligand system [16]. |

| PyMOL / VMD | Molecular visualization systems. | Used for visualizing the initial structure, simulation trajectories, and interaction analysis (e.g., H-bond plotting) [16]. |

| High-Resolution Co-crystal Structure | A experimentally determined structure of the protein-ligand complex. | Serves as the essential starting point and ground truth for the simulation [16]. |

Application Note 2: Engineering Biomaterials with Targeted Stability

Objective: To design hydrogel-based bioinks and enzyme-responsive biomaterials with optimal printability, long-term mechanical stability, and tailored biocompatibility for applications in regenerative medicine and drug delivery [18] [19].

Key Parameters for Biomaterial Stability and Function

The design of functional biomaterials requires balancing multiple properties. Rheological properties dictate printability, while cross-linking and enzymatic sensitivity determine in-vivo performance and stability.

Table 3: Critical Parameters for Hydrogel-Based Biomaterial Design [18] [19]

| Parameter | Influence on Function | Target/Example Value |

|---|---|---|

| Storage Modulus (G′) | Determines the mechanical stiffness and elastic solid-like behavior of the scaffold. | Should be > Loss Modulus (G″) for shape retention post-printing [18]. |

| Shear-Thinning Behavior | Enables extrusion during bioprinting by reducing viscosity under shear stress. | Essential property for extrusion-based bioprinting [18]. |

| Enzyme-Responsive Peptide Linker | Confers specific, on-demand degradation or drug release in target tissues. | MMP-2/9 cleavable sequence (e.g., PLGLAG) for targeting inflamed or remodeling tissues [19]. |

| Dual Cross-Linking | Enhances long-term mechanical stability and integrity of the printed construct. | Combination of ionic (e.g., CaCl₂ for alginate) and photo-crosslinking (e.g., UV for GelMA) [18]. |

| Swelling Ratio | Affects the scaffold's pore size, permeability, and mechanical load bearing. | Must be tuned to match the target tissue environment. |

Experimental Protocol: Rheology and Printability Assessment of Bioinks

Methodology: This protocol outlines a sequence of rheological tests to quantitatively correlate a bioink's properties with its printability and stability, as detailed in the Journal of Materials Chemistry B [18].

Bioink Formulation:

- Prepare the bioink formulation. An example optimal formulation is 4% Alginate (Alg), 10% Carboxymethyl Cellulose (CMC), and 8-16% Gelatin Methacrylate (GelMA) [18].

- Ensure all components are fully dissolved and homogeneously mixed.

Rheological Characterization: (Perform using a rotational rheometer with a parallel plate geometry)

- Flow Sweep Test: To assess shear-thinning.

- Set the temperature to the printing temperature (e.g., 20-25°C).

- Apply a linearly increasing shear rate (e.g., from 0.1 to 100 s⁻¹).

- Record the viscosity. A significant decrease in viscosity with increasing shear rate confirms shear-thinning behavior.

- Amplitude Sweep Test: To determine the linear viscoelastic region (LVE) and yield stress.

- At a fixed frequency (e.g., 10 rad/s), apply an oscillatory shear strain from 0.1% to 1000%.

- Record the storage (G′) and loss (G″) moduli.

- The yield stress is identified as the point where G′ drops sharply, indicating the transition from elastic to viscous behavior.

- Thixotropy Test: To evaluate self-healing and structural recovery.

- Apply a low oscillatory shear (e.g., 1% strain, within the LVE) for 2 minutes to simulate post-printing recovery.

- Switch to a high oscillatory shear (e.g., 200% strain) for 1 minute to simulate the extrusion process.

- Immediately return to the low shear for 5 minutes and monitor the recovery of G′.

- Time Sweep Test: To measure curing kinetics and final stiffness.

- After depositing the bioink, initiate cross-linking (e.g., expose to UV light for GelMA, or apply CaCl₂ spray for alginate).

- Monitor G′ and G″ over time at a fixed strain and frequency until the moduli plateau.

- Flow Sweep Test: To assess shear-thinning.

Printability Assessment:

- Use an extrusion-based 3D bioprinter.

- Print a standard test structure (e.g., a grid or filament) at the predetermined pressure and nozzle speed.

- Quantify printability using metrics like filament diameter consistency, ability to form freestanding filaments, and the printability value (Pr).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Biomaterial Formulation and Testing

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Equipment for Biomaterial Development

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Alginate (Alg) | A natural polymer that forms ionic hydrogels with divalent cations. | Provides the primary scaffold structure and enables ionic cross-linking with CaCl₂ [18]. |

| Gelatin Methacrylate (GelMA) | A photopolymerizable bioink component derived from gelatin. | Provides cell-adhesive motifs (RGD) and enables UV-triggered covalent cross-linking for stability [18]. |

| Carboxymethyl Cellulose (CMC) | A viscosity-modifying polymer. | Enhances the rheological properties and printability of the bioink formulation [18]. |

| Photoinitiator (e.g., LAP) | A compound that generates radicals upon UV light exposure. | Used to initiate the cross-linking of GelMA in the bioink [18]. |

| Rotational Rheometer | An instrument for measuring viscoelastic properties. | Used to perform flow sweeps, amplitude sweeps, and thixotropy tests to characterize the bioink [18]. |

| MMP-Cleavable Peptide (PLGLAG) | A peptide sequence degraded by Matrix Metalloproteinases. | Incorporated into hydrogels as a cross-linker for targeted, enzyme-responsive drug release in diseased tissues [19]. |

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process and key considerations in the biomaterial design pipeline, from formulation to functional assessment:

Biomaterial Design and Evaluation Pipeline

A Practical Toolkit: Fine-Tuning Methods and Platforms

The field of materials science is undergoing a significant transformation driven by the development of deep learning-based interatomic potentials. These models, often termed atomistic foundation models, leverage large-scale pre-training on diverse datasets to achieve broad applicability across the periodic table [2]. They represent a paradigm shift from traditional, narrowly focused machine-learned potentials towards general-purpose, universal interatomic potentials that can be fine-tuned for specific applications with remarkable data efficiency [3] [2]. Among the most prominent models in this rapidly evolving landscape are MACE, MatterSim, ORB, and GRACE. These models share the common objective of accurately simulating atomic interactions to predict material properties and behaviors, yet they differ in their architectural approaches, training methodologies, and specific strengths. This overview provides a detailed comparison of these leading models, focusing on their technical specifications, performance benchmarks, and practical implementation protocols for materials research and discovery.

Model Specifications and Comparative Analysis

The following sections detail the core architectures, training approaches, and performance characteristics of each model, with quantitative comparisons summarized in subsequent tables.

MACE (Multi-Atomic Cluster Expansion)

MACE employs an architecture that incorporates many-body messages and equivariant features, which effectively capture the symmetry properties of atomic structures [3]. This design enables high accuracy in modeling complex atomic environments. The model has been trained on the Materials Project dataset (MPtrj) and has demonstrated impressive performance across various benchmark systems [3]. A key advantage of the MACE framework is its suitability for fine-tuning strategies. Research has shown that applying transfer learning with partially frozen weights and biases—where parameters in earlier layers are fixed while later layers are adapted to new tasks—significantly enhances data efficiency [3]. This approach, implemented through the mace-freeze patch, allows MACE models to reach chemical accuracy with only hundreds of datapoints instead of the thousands typically required for training from scratch [3].

MatterSim

Developed by Microsoft Research, MatterSim is designed for simulating materials across wide ranges of temperature (0–5000 K) and pressure (0–1000 GPa) [20]. It utilizes a deep graph neural network trained through an active learning approach where a first-principles supervisor guides the exploration of materials space [20]. MatterSim demonstrates a ten-fold improvement in precision compared to prior models, with a mean absolute error of 36 meV/atom on its comprehensive MPF-TP dataset [20]. The model is particularly noted for its ability to predict Gibbs free energies with near-first-principles accuracy, enabling computational prediction of experimental phase diagrams [20]. MatterSim also serves as a platform for continuous learning, achieving up to 97% reduction in data requirements when fine-tuned for specific applications [20]. Two pre-trained versions are available: MatterSim-v1.0.0-1M (faster) and MatterSim-v1.0.0-5M (more accurate) [21] [22].

ORB

ORB represents a fast, scalable neural network potential that prioritizes computational efficiency without sacrificing accuracy [23]. Its architecture is based on a Graph Network Simulator augmented with smoothed graph attention mechanisms, where messages between nodes are updated based on both attention weights and distance-based cutoff functions [23]. A distinctive feature of ORB is that it learns atomic interactions and their invariances directly from data rather than relying on architecturally constrained models with built-in symmetries [23]. Upon release, ORB achieved a 31% reduction in error over other methods on the Matbench Discovery benchmark while being 3-6 times faster than existing universal potentials across various hardware platforms [23]. The model is available under the Apache 2.0 license, permitting both research and commercial use [23].

GRACE

It is important to note a significant naming ambiguity in the literature. While the search results reveal several models named GRACE, the most relevant in the context of materials foundation models is briefly mentioned in a review as an example of models trained on diverse chemical structures [3]. However, detailed technical specifications for a materials-focused GRACE model are not available in the search results, which instead predominantly refer to clinical and medical models (e.g., GRACE-ICU for patient risk assessment and GRACE score for acute coronary events) [24] [25] [26]. This overview will therefore focus on the well-documented MACE, MatterSim, and ORB models for subsequent comparative analysis and protocols.

Table 1: Core Model Specifications and Training Details

| Model | Architecture | Training Data Size | Parameter Count | Training Objective |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MACE-MP-0 | Many-body messages with equivariant features [3] | 1.58M structures [2] | 4.69M [2] | Energy, forces, stress [2] |

| MatterSim-v1 | Deep Graph Neural Network [20] | 17M structures [2] | 4.55M [2] | Energy, forces, stress [2] |

| ORB-v1 | Graph Network Simulator with attention [23] | 32.1M structures [2] | 25.2M [2] | Denoising + energy, forces, stress [2] |

| GRACE | Information not available in search results | Information not available in search results | Information not available in search results | Information not available in search results |

Table 2: Performance Characteristics and Applications

| Model | Key Strengths | Reported Accuracy | Optimal Fine-tuning Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| MACE | Data-efficient fine-tuning [3] | Chemical accuracy with 10-20% of data [3] | Frozen transfer learning (MACE-freeze) [3] |

| MatterSim | Temperature/pressure robustness [20] | 36 meV/atom MAE on MPF-TP [20] | Active learning with first-principles supervisor [20] |

| ORB | Computational speed [23] | 31% error reduction on Matbench Discovery [23] | Not specified in search results |

| GRACE | Information not available | Information not available | Information not available |

Fine-tuning Strategies and Experimental Protocols

Frozen Transfer Learning for MACE

Frozen transfer learning has emerged as a particularly effective fine-tuning strategy for foundation models, especially for MACE [3]. This protocol involves freezing specific layers of the pre-trained model during fine-tuning, which preserves general features learned from the original large dataset while adapting the model to specialized tasks with limited data.

Table 3: MACE Frozen Transfer Learning Configuration

| Component | Specification | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Foundation Model | MACE-MP "small", "medium", or "large" [3] | Provides pre-trained base with broad knowledge |

| Fine-tuning Data | 100-1000 structures [3] | Task-specific data for model adaptation |

| Frozen Layers | Typically 4 layers (MACE-MP-f4 configuration) [3] | Preserves general features from pre-training |

| Active Layers | Readout and product layers [3] | Adapts model to specific task |

| Performance | Similar accuracy with 20% of data vs. from-scratch training with 100% [3] | Enables high accuracy with minimal data |

Experimental Protocol for MACE Fine-tuning:

- Model Selection: Choose an appropriate pre-trained MACE-MP model ("small" recommended for balance of accuracy and efficiency) [3]

- Data Preparation: Curate a task-specific dataset of several hundred structures with corresponding energies and forces

- Model Configuration: Apply the mace-freeze patch to freeze the first four layers of the network [3]

- Training: Fine-tune only the unfrozen layers using the specialized dataset

- Validation: Validate against benchmark systems to ensure maintained accuracy on original capabilities while achieving improved performance on target domain

Active Learning Protocol for MatterSim

MatterSim employs an active learning workflow that integrates a deep graph neural network with a materials explorer and first-principles supervisor [20]. This approach continuously improves the model by targeting the most uncertain regions of the materials space.

MatterSim Active Learning Workflow

Implementation Steps:

- Initialization: Begin with a curated dataset from existing sources [20]

- Model Training: Train the MatterSim model on the current dataset

- Uncertainty Sampling: Use the trained model as a surrogate to identify regions of materials space with high prediction uncertainty [20]

- Targeted Exploration: Deploy materials explorers to gather additional structures from these uncertain regions [20]

- First-Principles Validation: Label the newly sampled structures using first-principles calculations (typically DFT at PBE level with Hubbard U correction) [20]

- Iterative Enrichment: Add the newly labeled structures to the training set and repeat the process through multiple active learning cycles [20]

This protocol enables MatterSim to achieve comprehensive coverage of materials space beyond the limitations of static databases, which often contain structural biases toward highly symmetric configurations near local energy minima [20].

Implementation Framework: MatterTune

The MatterTune framework provides an integrated, user-friendly platform for fine-tuning atomistic foundation models, including support for ORB, MatterSim, and MACE [2]. This platform addresses the current limitation in software infrastructure for leveraging atomistic foundation models across diverse materials informatics tasks.

Table 4: MatterTune Framework Components

| Subsystem | Function | Supported Capabilities |

|---|---|---|

| Model Subsystem | Manages different model architectures | Supports JMP, ORB, MatterSim, MACE, EquiformerV2 [2] |

| Data Subsystem | Handles diverse input formats | Standardized structure representation based on ASE package [2] |

| Trainer Subsystem | Controls fine-tuning procedures | Customizable training loops with distributed training support [2] |

| Application Subsystem | Enables downstream tasks | Property prediction, molecular dynamics, materials screening [2] |

Key Advantages of MatterTune:

- Modular Design: Decouples models, data, algorithms, and applications for high adaptability [2]

- Standardized Abstractions: Provides unified interfaces for diverse model architectures [2]

- Customizable Fine-tuning: Supports various fine-tuning strategies beyond black-box approaches [2]

- Broad Application Support: Enables use of foundation models for tasks beyond force fields, including property prediction and materials discovery [2]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 5: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource | Type | Function | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| MatterTune | Software framework | Fine-tuning atomistic foundation models [2] | GitHub: Fung-Lab/MatterTune [2] |

| MACE-Freeze | Software patch | Implements frozen transfer learning for MACE [3] | Integrated in MACE software suite [3] |

| Materials Project | Database | Source of training structures and references [3] | materialsproject.org |

| ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) | Software library | Structure manipulation and analysis [2] | wiki.fysik.dtu.dk/ase |

| MPtrj Dataset | Training data | Materials Project trajectory data for foundation models [3] | materialsproject.org |

The development of universal interatomic potentials represents a transformative advancement in computational materials science. MACE, MatterSim, and ORB each offer distinct approaches to addressing the challenge of accurate, efficient atomistic simulations across diverse chemical spaces and thermodynamic conditions. While these models demonstrate impressive zero-shot capabilities, their true potential is realized through strategic fine-tuning approaches such as frozen transfer learning and active learning, which enable researchers to achieve high accuracy on specialized tasks with minimal data requirements. Frameworks like MatterTune further lower barriers to adoption by providing standardized interfaces and workflows for leveraging these powerful models across diverse materials informatics applications. As these foundation models continue to evolve, they are poised to dramatically accelerate materials discovery and design through accurate, efficient prediction of structure-property relationships across virtually the entire periodic table.

Frozen transfer learning has emerged as a pivotal technique for enhancing the data efficiency of foundation models in atomistic materials research. This method involves taking a pre-trained model on a large, diverse dataset and fine-tuning it for a specific task by keeping (freezing) the parameters in a subset of its layers while updating (unfreezing) others. Foundation models, pre-trained on extensive datasets, learn robust, general-purpose representations of atomic interactions. However, they often lack the specialized accuracy required for predicting precise properties like reaction barriers or phase transitions in specific systems. Frozen transfer learning addresses this by leveraging the model's general knowledge while efficiently adapting it to specialized tasks with minimal data, thereby preventing overfitting and the phenomenon of "catastrophic forgetting" where a model loses previously learned information [3].

In the domain of materials science and drug development, where generating high-quality training data from first-principles calculations is computationally prohibitive, this approach is particularly valuable. It represents a paradigm shift from building task-specific models from scratch to adapting versatile, general models, making high-accuracy machine-learned interatomic potentials accessible for a wider range of scientific investigations [3] [2].

Quantitative Analysis of Data Efficiency

The application of frozen transfer learning to materials foundation models demonstrates significant gains in data efficiency and predictive performance across different systems.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Fine-Tuning Strategies on the H₂/Cu System [3]

| Model Type | Training Data Used | Energy RMSE (meV/atom) | Force RMSE (meV/Å) | Primary Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| From-Scratch MACE | 100% (~3,376 configs) | ~3.0 | ~90 | Baseline accuracy |

| MACE-MP-f4 (Frozen) | 20% (~664 configs) | ~3.0 | ~90 | Similar accuracy with 80% less data |

| MACE-MP-f4 (Frozen) | 10% (~332 configs) | ~5.5 | ~125 | Good accuracy with 90% less data |

Table 2: Impact of Foundation Model Size on Fine-Tuning Efficiency [3]

| Foundation Model | Number of Parameters | Relative Fine-Tuning Compute | Final Accuracy on H₂/Cu |

|---|---|---|---|

| MACE-MP "Small" | ~4.69 million | 1.0x (Baseline) | High |

| MACE-MP "Medium" | ~9.06 million | ~1.8x | Comparable to Small |

| MACE-MP "Large" | ~16.2 million | ~3.5x | Comparable to Small |

Studies on reactive hydrogen chemistry on copper surfaces (H₂/Cu) show that a frozen transfer-learned model (MACE-MP-f4) achieves accuracy comparable to a model trained from scratch using only 20% of the original training data—hundreds of data points instead of thousands [3]. This strategy also reduces GPU memory consumption by up to 28% compared to full fine-tuning, as freezing layers reduces the number of parameters that need to be stored and updated during training [27]. The "small" foundation model is often sufficient for fine-tuning, offering an optimal balance between performance and computational cost [3].

Experimental Protocols for Frozen Transfer Learning

Protocol 1: Fine-Tuning a Foundation Potential for a Surface Chemistry Application

This protocol details the procedure for adapting a general-purpose MACE-MP foundation model to study the dissociative adsorption of H₂ on Cu surfaces [3].

- Objective: To create a highly accurate and data-efficient machine learning interatomic potential for H₂/Cu reactive dynamics.

- Primary Materials & Models:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Data Preparation and Partitioning:

- Curate your target dataset (e.g., H₂/Cu structures with DFT-calculated energies and forces).

- Split the data into training (e.g., 80%), validation (e.g., 10%), and test sets (e.g., 10%). For data efficiency analysis, create smaller subsets (e.g., 10%, 20%) from the full training set.

Model and Optimizer Setup:

- Load the pre-trained MACE-MP "small" model.

- Configure the

mace-freezepatch to freeze all layers up to and including the first three interaction layers. This corresponds to the "f4" configuration, which keeps the foundational feature detectors frozen while allowing the later layers to specialize [3]. - Initialize an optimizer (e.g., Adam) with a reduced learning rate (e.g., 1e-4) for the unfrozen parameters to enable stable adaptation.

Training and Validation Loop:

- Train the model on the target training set, using the validation set to monitor for overfitting.

- Use a loss function that combines energy and force errors.

- Employ early stopping if the validation loss does not improve for a predetermined number of epochs.

Model Evaluation:

- Evaluate the final model on the held-out test set.

- Report key metrics: Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) on energies and forces, comparing performance against a from-scratch model and the baseline foundation model.

Protocol 2: Fine-Tuning for Ternary Alloy Properties

This protocol outlines the adaptation for predicting the stability and elastic properties of ternary alloys [3].

- Objective: To develop a specialized model for accurate property prediction in complex ternary alloy systems.

- Primary Materials & Models:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Data Preparation:

- Assemble a dataset of ternary alloy structures with calculated energies, forces, and target properties (e.g., elastic tensor components).

- Perform a train/validation/test split as in Protocol 1.

Freezing Strategy Selection:

- For CHGNet, a common strategy is to freeze the entire graph neural network backbone and only fine-tune the readout layers. For MACE, the "f4" or "f5" configuration is recommended [3] [28].

- This approach preserves the general physical knowledge of atomic interactions while efficiently learning the mapping to the new properties.

Fine-Tuning Execution:

- Load the foundation model and apply the chosen freezing configuration.

- Use a loss function tailored to the target properties (e.g., including a stress term for elastic properties).

- Proceed with training and validation as in Steps 3 and 4 of Protocol 1.

Surrogate Model Generation (Optional):

- Use the fine-tuned, high-accuracy model to generate labels for a larger set of configurations.

- Train a more computationally efficient surrogate model, such as an Atomic Cluster Expansion (ACE) potential, on this generated data, creating a fast model for large-scale simulations [3].

Workflow and Strategy Visualization

Figure 1: A decision workflow for selecting an optimal layer-freezing strategy, based on dataset characteristics and project goals [3] [27].

Table 3: Key Resources for Frozen Transfer Learning Experiments

| Resource Name | Type | Function / Application | Example / Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| MACE-MP Models | Foundation Model | Pre-trained interatomic potentials providing a robust starting point for fine-tuning. | MACE-MP-0, MACE-MP-1 [3] [2] |

mace-freeze Patch |

Software Tool | Enables layer-freezing for fine-tuning within the MACE software suite. | [3] |

| MatterTune | Software Platform | Integrated, user-friendly framework for fine-tuning various atomistic foundation models (ORB, MatterSim, MACE). | [2] |

| Materials Project (MPtrj) | Pre-training Dataset | Large-scale dataset of DFT calculations used to train foundation models. | ~1.58M structures [3] [2] |

| H₂/Cu Surface Dataset | Target Dataset | Task-specific dataset for benchmarking fine-tuning performance on reactive chemistry. | 4,230 structures [3] |

| Atomic Cluster Expansion (ACE) | Surrogate Model | A fast, efficient potential that can be trained on data generated by a fine-tuned model for large-scale MD. | [3] |

Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT) represents a strategic shift in how researchers adapt large, pre-trained models to specialized tasks. Instead of updating all of a model's parameters—a computationally expensive process known as full fine-tuning—PEFT methods selectively modify a small portion of the model or add lightweight, trainable components. This drastically reduces computational requirements, memory consumption, and storage overhead without significantly compromising performance [29]. In natural language processing (NLP) and computer vision, techniques like Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) have become standard practice. However, the application of PEFT to molecular systems presents unique challenges, primarily due to the critical need to preserve fundamental physical symmetries—a requirement that conventional methods often violate [30] [31].

The emergence of atomistic foundation models pre-trained on vast quantum chemical datasets has created an urgent need for efficient adaptation strategies. These models learn general, transferable representations of atomic interactions but often require specialization to achieve chemical accuracy on specific systems, such as novel materials or complex biomolecular environments [3] [32]. This application note details the theoretical foundations, practical protocols, and recent advancements in PEFT for molecular systems, with a focused examination of LoRA and its equivariant extension, ELoRA, providing researchers with a framework for efficient and physically consistent model specialization.

Fundamental Techniques: From LoRA to ELoRA

Standard LoRA and Its Limitations in Scientific Domains

Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) is a foundational PEFT technique that operates on a core hypothesis: the weight updates (ΔW) required to adapt a pre-trained model to a new task have a low "intrinsic rank." Instead of computing the full ΔW matrix, LoRA directly learns a decomposed representation through two smaller, trainable matrices, A and B, such that ΔW = AB [29] [33]. During training, only A and B are updated, while the original pre-trained weights W remain frozen. The updated forward pass for a layer therefore becomes: h = Wx + BAx, where r (the rank) is a key hyperparameter, typically much smaller than the original matrix dimensions [33].

This approach offers significant advantages:

- Memory Efficiency: It dramatically reduces the number of trainable parameters, often to less than 1% of the original model, enabling fine-tuning on consumer-grade GPUs [29].

- Modularity: Multiple, task-specific LoRA adapters can be trained independently and swapped on top of a single, frozen base model [34].

However, a critical limitation arises when applying standard LoRA to geometric models like Equivariant Graph Neural Networks (GNNs). The arbitrary matrices A and B do not respect the rotational, translational, and permutational symmetries (SO(3) equivariance) that are fundamental to physical systems. Mixing different tensor orders during the adaptation process inevitably breaks this equivariance, leading to physically inconsistent predictions [30] [35].

ELoRA: Preserving Equivariance for Molecular Systems

ELoRA (Equivariant Low-Rank Adaptation) was introduced to address the symmetry-breaking shortfall of standard LoRA. Designed specifically for SO(3) equivariant GNNs, which serve as the backbone for many pre-trained interatomic potentials, ELoRA ensures that fine-tuning preserves equivariance—a critical property for physical consistency [30] [31].

The key innovation of ELoRA is its path-dependent decomposition for weight updates. Unlike standard LoRA, which applies the same low-rank update across all feature channels, ELoRA applies separate, independent low-rank adaptations to each irreducible representation (tensor order) path within the equivariant network [35]. This method prevents the mixing of features from different tensor orders, thereby strictly preserving the equivariance property throughout the fine-tuning process [30]. This approach not only maintains physical consistency but also leverages low-rank adaptations to significantly improve data efficiency, making it highly effective even with small, task-specific datasets [31].

Performance Comparison and Quantitative Benchmarks

The effectiveness of ELoRA and related advanced PEFT methods is demonstrated through comprehensive benchmarks on standard molecular datasets. The table below summarizes their performance in predicting energies and forces—key quantities in atomistic simulations.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Fine-Tuning Methods on Molecular Benchmarks

| Method | Key Principle | rMD17 (Organic) Energy MAE | rMD17 (Organic) Force MAE | 10 Inorganic Datasets Avg. Energy MAE | 10 Inorganic Datasets Avg. Force MAE | Trainable Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Fine-Tuning | Updates all model parameters | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline | Baseline | 100% |

| ELoRA [30] [31] | Path-dependent, equivariant low-rank adaptation | 25.5% improvement vs. full fine-tuning | 23.7% improvement vs. full fine-tuning | 12.3% improvement vs. full fine-tuning | 14.4% improvement vs. full fine-tuning | Highly Reduced (<5%) |

| MMEA [35] | Scalar gating modulates feature magnitudes | State-of-the-art levels | State-of-the-art levels | State-of-the-art levels | State-of-the-art levels | Fewer than ELoRA |

| Frozen Transfer Learning (MACE-MP-f4) [3] | Freezes early layers of foundation model | Similar accuracy to from-scratch training with ~20% of data | Similar accuracy to from-scratch training with ~20% of data | Not Specified | Not Specified | Highly Reduced |

A recent advancement beyond ELoRA is the Magnitude-Modulated Equivariant Adapter (MMEA). Building on the insight that a well-trained equivariant backbone already provides robust feature bases, MMEA employs an even lighter strategy. It uses lightweight scalar gates to dynamically modulate feature magnitudes on a per-channel and per-multiplicity basis without mixing them. This approach preserves strict equivariance and has been shown to consistently outperform ELoRA across multiple benchmarks while training fewer parameters, suggesting that in many scenarios, modulating channel magnitudes is sufficient for effective adaptation [35].

Experimental Protocols for Fine-Tuning Molecular Foundation Models

Protocol 1: Fine-Tuning with ELoRA

This protocol outlines the steps for adapting a pre-trained equivariant GNN using the ELoRA method.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for ELoRA Fine-Tuning

| Item Name | Function / Description | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-trained Equivariant GNN | The base model providing foundational knowledge of interatomic interactions. | Models: MACE, EquiformerV2, NequIP, eSEN [32] [2]. |

| Target Dataset | The small, task-specific dataset for adaptation. | A few hundred to a few thousand local structures of the target molecular system [35]. |

| ELoRA Adapter Modules | The trainable, path-specific low-rank matrices injected into the base model. | Rank r is a key hyperparameter; code available at [30]. |

| Software Framework | Library providing implementations of equivariant models and PEFT methods. | e3nn framework, MatterTune platform [2]. |

| Optimizer | Algorithm for updating the trainable parameters during fine-tuning. | AdamW or SGD; choice has minimal impact on performance with low ranks [33]. |

Procedure:

- Model Preparation: Load a pre-trained equivariant foundation model (e.g., MACE-MP) and freeze all its parameters.

- ELoRA Injection: Inject ELoRA adapter modules into the designated layers of the model (typically the linear layers within interaction blocks). These modules are initialized with small, random values.

- Dataset Splitting: Split your target dataset into training (80%), validation (10%), and test (10%) sets. Ensure the dataset contains structures, energies, and forces.

- Loss Function Configuration: Define a composite loss function,

L = α * L_energy + β * L_forces, whereαandβare scaling factors (e.g., 1 and 100 respectively) to balance the importance of energy and force accuracy. - Hyperparameter Tuning:

- Set the rank

rof the ELoRA matrices. Start with a low value (e.g., 2, 4, or 8) and increase if performance is inadequate [33]. - Choose a learning rate for the optimizer, typically in the range of 1e-4 to 1e-3, as only the adapters are being trained.

- Set the number of epochs based on dataset size, monitoring for overfitting on the validation set.

- Set the rank

- Training Loop: For each epoch, iterate through the training set, performing forward and backward passes to update only the ELoRA adapter parameters.

- Validation and Early Stopping: Evaluate the model on the validation set after each epoch. Stop training if validation loss does not improve for a predetermined number of epochs (patience).

- Final Evaluation: Assess the final fine-tuned model's performance on the held-out test set to gauge its generalization capability.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the ELoRA fine-tuning process:

Protocol 2: Frozen Transfer Learning for Data Efficiency

An alternative PEFT strategy, particularly effective with very large foundation models, is frozen transfer learning. This method involves freezing a significant portion of the model's early layers and only fine-tuning the later layers on the new data [3].

Procedure:

- Model Selection: Choose a foundation model pre-trained on a massive, diverse dataset (e.g., MACE-MP, JMP, or a UMA model trained on OMol25) [32] [2].

- Layer Freezing Strategy: Freeze the parameters in the initial layers of the network. For example, with a MACE model, you might freeze all layers up to and including the first few interaction blocks (e.g., a configuration known as MACE-MP-f4) [3].

- Fine-Tuning: Unfreeze and update only the remaining, higher-level layers of the model. This allows the model to adapt its more specialized representations to the new task while retaining the general, low-level features learned during pre-training.

- Training: Proceed with a standard training loop, but note that the number of trainable parameters is substantially reduced, similar to LoRA-based methods.

This approach has been shown to achieve accuracy comparable to models trained from scratch on thousands of data points using only hundreds of target configurations (10-20% of the data), demonstrating exceptional data efficiency [3].

Integrated Software and Workflow Tools

To lower the barriers for researchers, integrated platforms like MatterTune have been developed. MatterTune is a user-friendly framework that provides standardized, modular abstractions for fine-tuning various atomistic foundation models [2].

- Supported Models: It supports a wide range of state-of-the-art models, including ORB, MatterSim, JMP, MACE, and EquiformerV2, within a unified interface [2].

- Workflow Integration: The platform simplifies the entire fine-tuning pipeline, from data handling and model configuration to distributed training and application to downstream tasks like molecular dynamics and property screening [2].

- Customization: Despite its ease of use, MatterTune maintains flexibility, allowing researchers to customize fine-tuning procedures, including the implementation of PEFT methods like those discussed here [2].

The following diagram illustrates the high-level software workflow within such a platform:

The adoption of Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning methods, particularly equivariant approaches like ELoRA and MMEA, marks a significant advancement in atomistic materials research. These techniques enable researchers to leverage the power of large foundation models while overcoming critical constraints related to computational cost, data scarcity, and—most importantly—physical consistency. By providing robust performance with a fraction of the parameters, PEFT democratizes access to high-accuracy simulations, paving the way for rapid innovation in drug development, battery design, and novel materials discovery. Integrating these protocols into user-friendly platforms like MatterTune further accelerates this progress, empowering scientists to focus on scientific inquiry rather than computational overhead.

The emergence of atomistic foundation models (AFMs) represents a paradigm shift in computational materials science and chemistry. These models, pre-trained on vast and diverse datasets of quantum mechanical calculations, learn fundamental, transferable representations of atomic interactions [36] [2]. However, a significant challenge persists: achieving quantitative accuracy for specific systems and properties often requires adapting these general-purpose models to specialized downstream tasks [14] [3]. Fine-tuning—the process of further training a pre-trained model on a smaller, application-specific dataset—has emerged as a critical technique to bridge this gap, enabling researchers to leverage the broad knowledge of foundation models while attaining the precision needed for predictive simulations [14] [3].

Despite its promise, the widespread adoption of fine-tuning has been hampered by technical barriers. The ecosystem of atomistic foundation models is fragmented, with each model often having distinct architectures, data formats, and training procedures [36] [14]. This lack of standardization forces researchers to navigate a complex landscape of software tools, creating inefficiency and limiting reproducibility. To address these challenges, integrated software frameworks have been developed. This application note focuses on two such frameworks: MatterTune, an integrated platform for fine-tuning diverse AFMs for broad materials informatics tasks, and the aMACEing Toolkit, a unified interface specifically designed for fine-tuning workflows across multiple machine-learning interatomic potential (MLIP) frameworks [36] [14]. These toolboxes are designed to lower the barriers to adoption, streamline workflows, and facilitate robust, reproducible fine-tuning strategies in materials foundation model research.

MatterTune: A Unified Platform for Atomistic Foundation Models

MatterTune is designed as a modular and extensible framework that simplifies the process of fine-tuning various atomistic foundation models and integrating them into downstream materials informatics and simulation workflows [36] [2]. Its core objective is to provide a standardized, user-friendly interface that abstracts away the implementation complexities of different models, thereby accelerating research and development.

Core Architecture and Abstractions: MatterTune's architecture is built around several key abstractions that ensure flexibility and generalizability [2] [37]:

- Data Abstraction: It employs a minimal data abstraction, defining a dataset as a mapping from sample indices to atomic structures standardized in the