Electrodeposition Nucleation and Growth of Metal Compounds in Aqueous Solutions: Mechanisms, Control, and Biomedical Applications

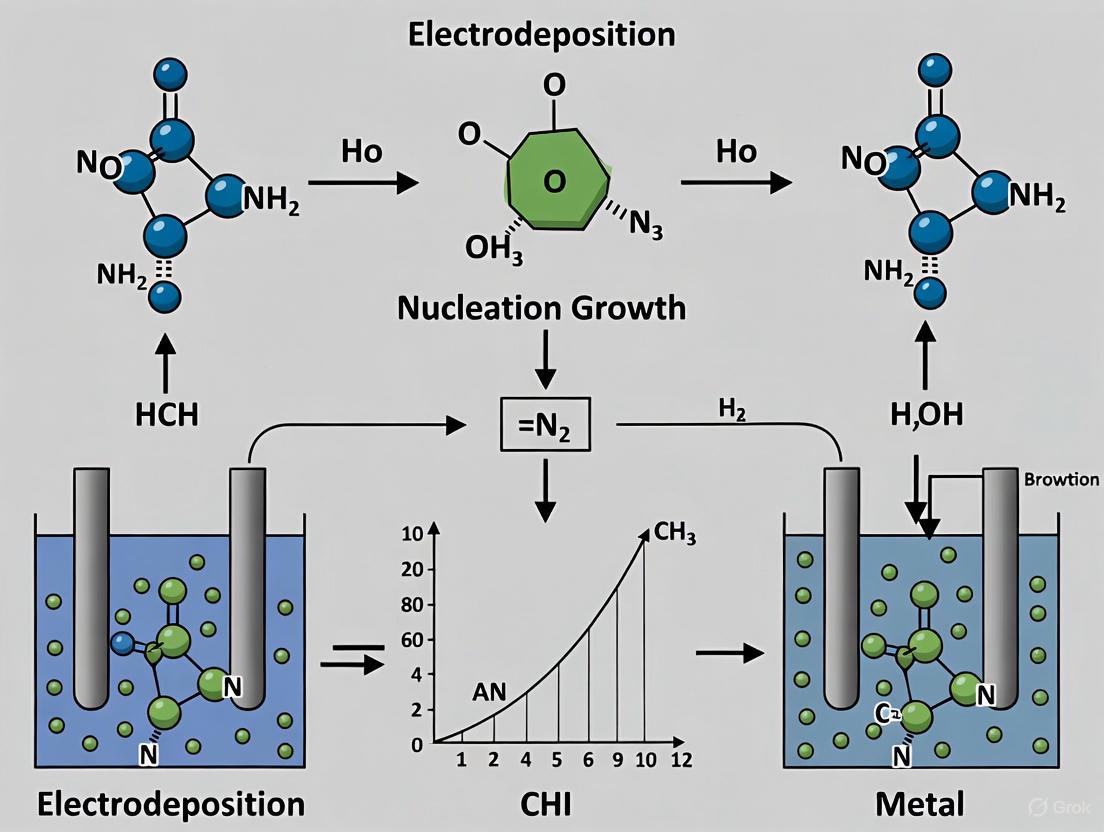

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the nucleation and growth mechanisms during the electrodeposition of metal compounds from aqueous solutions, a critical process for fabricating advanced functional materials.

Electrodeposition Nucleation and Growth of Metal Compounds in Aqueous Solutions: Mechanisms, Control, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the nucleation and growth mechanisms during the electrodeposition of metal compounds from aqueous solutions, a critical process for fabricating advanced functional materials. It explores foundational theories, from classical models to modern non-classical pathways, and details practical methodologies for controlling deposit morphology and properties. The content addresses common challenges such as hydrogen evolution and dendrite formation, offering optimization strategies and troubleshooting guidance. With a specific focus on applications for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the electrochemical synthesis of catalytic, magnetic, and smart drug-delivery systems. The review also synthesizes advanced validation techniques and comparative analyses of different electrochemical systems, providing a holistic resource for developing next-generation biomedical and clinical technologies.

Unraveling Core Principles: From Classical Nucleation to Modern Electrocrystallization Theory

Fundamental Concepts and Theoretical Background

Electrocrystallization is an electrochemical process involving the initial formation of a new phase (nucleation) on a foreign substrate, followed by its subsequent growth. This process is fundamental to various applications, including electroplating, corrosion protection, and the synthesis of functional metallic coatings [1]. The classical theory of nucleation, established by pioneers such as Volmer, Weber, Kossel, and Stranski, describes the formation of stable nuclei on a substrate. A critical concept is the "half-crystal position," introduced by Kossel and Stranski, which describes the energy state of an atom at a kink site on a crystal surface. This position represents the point where an atom is bound to the crystal with half the energy of an atom within the crystal lattice, making it a preferred site for attachment during growth [1].

The work required to form a stable nucleus is a central theme in the theory. The equations derived for this nucleation work align with classical theories, and analyses indicate that the critical nucleus size—the smallest stable cluster of atoms that can grow into a larger crystal—can be as small as one to four atoms under certain conditions [1]. Furthermore, for a cubic crystal to exhibit properties of an 'infinitely large' crystal, defined by its bond energy, its size must exceed approximately 30 nm [1]. Modern research continues to build upon these foundational concepts to understand and control the electrodeposition of metals and alloys.

Key Electrochemical Techniques for Investigation

Understanding the nucleation and growth mechanism, as well as the kinetics of electrodeposition, is crucial for controlling the phase, composition, and morphology of metal deposits [2]. Several electrochemical techniques are vital for studying these processes.

Table 1: Key Electrochemical Techniques for Studying Electrocrystallization

| Technique | Primary Function | Key Measurable Parameters | Application in Electrocrystallization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potentiostatic | Applies a fixed potential and measures resulting current over time [3]. | Transient current, nucleation rate. | Studying nucleation kinetics and growth mechanisms via current-time transients [2]. |

| Galvanostatic | Applies a fixed current and measures voltage over time [3]. | Deposition potential, capacity. | Suitable for electroplating and battery testing where charge is controlled [3]. |

| Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Scans potential linearly and measures current [3]. | Redox potentials, reaction reversibility, peak currents. | Analyzing redox behavior, identifying deposition potentials, and evaluating electrocatalysts [3]. |

| Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) | Applies a small AC potential over a frequency range and measures impedance [3]. | Charge transfer resistance (Rct), solution resistance (Rs), double-layer capacitance (Cdl). | Probing interface properties and reaction mechanisms at the electrode surface [3]. |

Experimental Protocols for Nucleation and Growth Analysis

This section provides a detailed methodology for investigating electrochemical nucleation and growth, exemplified by studies on aluminum and nickel-cobalt systems.

Protocol: Potentiostatic Current Transient Analysis for Aluminum Electrodeposition

This protocol is adapted from research on Al coatings electrodeposited from an AlCl₃-N-methylformamide (NMF) organic solvent system [4].

1. Electrolyte Preparation (AlCl₃-NMF System)

- Materials: Anhydrous AlCl₃, N-methylformamide (NMF), 3Å molecular sieves.

- Procedure:

- Dry AlCl₃ in a vacuum oven at 120 °C for 48 hours.

- Dry NMF using 3Å molecular sieves for 48 hours.

- Perform all preparation steps in an inert atmosphere glove box (e.g., Ar-filled) with real-time monitoring of water and oxygen content (maintain H₂O < 0.01 ppm, O₂ < 0.1 ppm).

- Mix AlCl₃ and dried NMF in molar ratios ranging from 1.0:1 to 1.5:1 (AlCl₃:NMF) and stir until a homogeneous liquid is formed [4].

2. Electrodeposition and In-Situ Microscopy

- Working Electrode: A suitable substrate (e.g., 300M steel, tungsten wire).

- Reference Electrode: A suitable reference (e.g., Al wire).

- Counter Electrode: Platinum or other inert material.

- Procedure:

- Set the potentiostat to the desired electrodeposition potential.

- Simultaneously record the current-time transient and use electrochemical in-situ optical microscopy to visually monitor the dynamic growth process of Al nuclei in real-time [4].

- The current transient can be analyzed to show three key regions: the charging of the electric double layer, the 3D nucleation and growth of Al, and the reduction of residual water on the deposited Al nuclei [4].

Protocol: Modeling Nucleation in Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES)

This protocol is based on the electrodeposition of Ni and Co from a metal nitrate-L-serine DES [2].

1. DES Electrolyte Synthesis (Metal Nitrate-L-Serine)

- Materials: Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O and/or Co(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, L-serine.

- Procedure:

- Weigh metal nitrate hydrates and L-serine in a molar ratio of 2:1 (M(NO₃)₂·6H₂O : L-Serine).

- Place the mixture in a beaker and stir at 60 °C until a homogeneous liquid is formed [2].

2. Potentiostatic Current Transient Analysis and Model Fitting

- Procedure:

- Perform potentiostatic experiments and record current-density time (j-t) transients.

- Data Fitting: Preliminary analysis may show that standard models (e.g., Scharifker-Mostany for monometallic deposition) do not fully fit the j-t curve. A modified model that integrates proton reduction and adsorption processes with the electrochemical nucleation and growth of metals must be applied to describe the experimental data satisfactorily [2].

- Procedure:

Quantitative Data and Nucleation Models

Analysis of current transients allows for the quantitative assessment of nucleation type and growth kinetics. The following table summarizes key parameters and models.

Table 2: Quantitative Analysis of Nucleation and Growth from Current Transients

| Parameter / Model | Mathematical Form | Significance & Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Diffusion Coefficient (D) | Determined from Cottrell equation or similar analysis [4]. | Quantifies the mass transport rate of metal ions to the electrode surface. A higher D suggests faster ion transport. |

| Instantaneous Nucleation | ( I(t) = \frac{zFD^{1/2}c}{\pi^{1/2}t^{1/2}} [1 - \exp(-N_0\pi k'Dt)] ) | Assumes all nuclei form instantaneously at the start of the potential step, and growth occurs from a fixed number of sites. |

| Progressive Nucleation | ( I(t) = \frac{zFD^{1/2}c}{\pi^{1/2}t^{1/2}} [1 - \exp(-AN_0\pi k''Dt^2)] ) | Assumes nuclei form slowly over time, leading to an increasing number of growth sites during the potential step. |

| Scharifker-Mostany Model | Non-dimensional ( (I/Im)^2 ) vs ( t/tm ) plot [2]. | Used to distinguish between instantaneous and progressive nucleation mechanisms by comparing experimental data to theoretical curves. |

| Ni-Co/L-Serine DES | Modified model integrating proton reduction [2]. | Required to accurately fit experimental data, indicating competing reactions alongside metal deposition. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Aqueous Electrodeposition Research

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Potentiostat/Galvanostat | Core instrument for applying controlled potentials or currents and measuring the electrochemical response [3]. |

| Electrochemical Cell | Container for the electrolyte and electrodes; available in glass or PTFE, with options for temperature and gas control [3]. |

| Working Electrodes | Substrate for deposition; common materials include Glassy Carbon (GC), Gold, Platinum, and industrially relevant metals like steel [3]. |

| Reference Electrodes | Provides a stable and known potential for accurate control of the working electrode potential (e.g., Saturated Calomel Electrode - SCE, Ag/AgCl) [3]. |

| Counter Electrodes | Completes the electrical circuit; typically made of inert materials like Platinum wire or mesh [3]. |

| Metal Salts | Source of metal ions in the electrolyte (e.g., Ni(NO₃)₂, Co(NO₃)₂, AlCl₃, NiSO₄, CoSO₄) [2] [4]. |

| Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES) Components | Eco-friendly electrolyte alternatives; common components include Choline Chloride (ChCl), Urea, Ethylene Glycol, and amino acids like L-Serine [2]. |

| Rotating Disk Electrode (RDE) | Establishes controlled hydrodynamics at the electrode surface, enhancing mass transport for accurate kinetic measurements [3]. |

Visualization of Electrocrystallization Processes

The following diagrams, created using Graphviz, illustrate the key pathways and workflows in electrochemical nucleation.

Nucleation Energy Pathway

Experimental Workflow

Theoretical Foundations of Classical Nucleation Theory

Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) is the primary theoretical model used to quantitatively study the kinetics of phase formation, a process where a new thermodynamic phase or structure spontaneously emerges from a metastable state [5]. The central objective of CNT is to explain and predict the immense variation observed in nucleation times, which can range from negligible to exceedingly long periods [5]. The theory is particularly relevant for understanding the initial stages of electrodeposition, where the formation of metallic nuclei on a substrate determines the properties of the final coating [4] [2].

The theory posits that the formation of a stable nucleus is governed by the competition between two energy terms as molecules cluster: the bulk free energy gained from the phase transition and the surface free energy required to create the new interface [6]. The total free energy change, ΔG, for forming a spherical cluster of radius r is given by:

ΔG = 4/3 πr³ Δg_v + 4πr² σ [5]

Here, Δg_v is the Gibbs free energy change per unit volume (which is negative for a spontaneous process), and σ is the interfacial free energy per unit area [5]. The first term represents the volumetric free energy reduction driving the transformation, while the second term represents the energy cost of creating the new surface. This energy competition results in a free energy barrier that must be overcome for a stable nucleus to form [6].

The Critical Nucleus and Energetics

A cluster must reach a specific size, known as the critical nucleus, to become stable and proceed to grow. Clusters smaller than this critical size tend to dissolve, while those larger than it are likely to continue growing [6]. The size of the critical nucleus, r_c, and the height of the nucleation free energy barrier, ΔG*, are derived from the maximum of the ΔG function [5]:

r_c = 2σ / |Δg_v| [5]

ΔG* = 16πσ³ / (3|Δg_v|²) [5]

The supersaturation of the solution, S, is a critical parameter influencing this process. It is defined as S = c / c_0, where c is the actual concentration and c_0 is the equilibrium saturation concentration [6]. The chemical potential difference, Δμ = k_B T ln S, provides the thermodynamic driving force for nucleation [6]. Higher supersaturation leads to a lower free energy barrier and a smaller critical nucleus size, making nucleation more favorable [6].

Table 1: Key Thermodynamic Parameters in Classical Nucleation Theory.

| Parameter | Symbol | Equation/Description | Significance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical Radius | r_c |

`r_c = 2σ / | Δg_v | ` | Minimum stable cluster size; clusters larger than r_c will grow. |

| Nucleation Barrier | ΔG* |

`ΔG* = 16πσ³ / (3 | Δg_v | ²)` | Energy barrier that must be overcome for stable nucleus formation. |

| Supersaturation | S |

S = c / c_0 |

Thermodynamic driving force; higher S lowers ΔG* and r_c. |

CNT in Electrodeposition: Nucleation and Growth Kinetics

In the context of electrodeposition, the reduction of metal ions (e.g., Al³⁺, Ni²⁺, Co²⁺) from a solution onto a substrate is a quintessential example of heterogeneous nucleation [4] [2]. The electrodeposition process allows fine control over nucleation and growth through applied potential and current, which directly affects the morphology and number density of nuclei [2].

The steady-state nucleation rate, R, is the central result of CNT and is expressed in an Arrhenius-like form [5]:

R = N_S Z j exp( -ΔG* / (k_B T) ) [5]

N_S: The number of potential nucleation sites per unit volume.Z j: The dynamic part, related to the rate at which molecules attach to the critical nucleus.Zis the Zeldovich factor (typically ~10⁻³), andjis the attachment frequency of monomers [5].exp( -ΔG* / (k_B T) ): The probabilistic factor representing the likelihood that a fluctuation will provide the energyΔG*needed to form the critical nucleus [5].

For electrodeposition in deep eutectic solvents (DES) or ionic liquids, the process is often diffusion-controlled and involves three-dimensional (3D) nucleation and growth [4] [2]. The nucleation rate can be quantified by analyzing current-time transients from potentiostatic experiments [2]. The initial current decay corresponds to the charging of the electric double layer, followed by a current rise associated with the 3D nucleation and growth of metal nuclei, and finally a decay as diffusion fields overlap [4].

Heterogeneous vs. Homogeneous Nucleation

Heterogeneous nucleation, which occurs on surfaces or impurities, is far more common than homogeneous nucleation because the nucleation barrier is significantly reduced [5]. The free energy needed for heterogeneous nucleation, ΔG_het, is related to that for homogeneous nucleation by a factor f(θ) that depends on the contact angle, θ, between the nucleus and the substrate [5]:

ΔG_het = f(θ) ΔG_hom, where f(θ) = (2 - 3cosθ + cos³θ) / 4 [5]

The factor f(θ) is always less than 1 for any contact angle between 0° and 180°, making heterogeneous nucleation kinetically favored [5]. This is critically important in electrodeposition, where the substrate surface properties and any imperfections act as preferential sites for nucleation [4].

Diagram 1: Energetic pathway and key factors in nucleus formation. The critical nucleus represents the peak of the energy barrier; factors like high supersaturation and low interfacial energy promote its formation.

Experimental Protocols for Studying Nucleation in Electrodeposition

Protocol 1: Potentiostatic Current Transient Analysis for 3D Nucleation

This protocol is used to determine the nucleation mechanism and kinetic parameters for metal electrodeposition, as applied in studies on Al, Ni, and Co coatings [4] [2].

Electrolyte Preparation: Perform all preparations in an inert atmosphere glove box (e.g., Ar-filled) with real-time monitoring of water and oxygen content (maintain <0.1 ppm O₂, <0.01 ppm H₂O) to prevent oxidation and hydrolysis of metal salts [4].

- Dry metal salts (e.g., AlCl₃, Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O) in a vacuum oven at 120°C for 48 hours [4].

- Dry solvents (e.g., N-methylformamide, L-serine) using 3Å molecular sieves for 48 hours [4] [2].

- Prepare the electrolyte by mixing metal salts and solvents at the desired molar ratios (e.g., AlCl₃:NMF at 1.0:1 to 1.5:1) and stir until a homogeneous liquid is formed [4].

Electrochemical Cell Setup: Use a standard three-electrode cell.

- Working Electrode: A polished inert substrate (e.g., glassy carbon, steel). Polish sequentially with alumina slurry (e.g., 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm) and clean ultrasonically in ethanol and deionized water [2].

- Counter Electrode: A platinum mesh or wire.

- Reference Electrode: A suitable reference (e.g., Ag/AgCl for aqueous systems, Al wire for non-aqueous Al systems).

Potentiostatic Experiment:

- Set the electrolyte temperature using a thermostated water bath.

- Apply a single potential step from a region where no Faradaic process occurs to a sufficiently negative potential to drive metal deposition.

- Record the current response as a function of time with high sampling rate until the transient reaches a steady state.

Data Analysis:

- Plot the recorded current density (

j) against time (t). - The transient should show three characteristic regions: double-layer charging (initial decay), nucleation and growth (current rise), and diffusion-controlled growth (current decay) [4].

- Model the

(j/j_m)²vs(t/t_m)data, wherej_mandt_mare the current and time at the peak of the transient, using established models (e.g., Scharifker-Mostany) to distinguish between instantaneous and progressive nucleation mechanisms [2].

- Plot the recorded current density (

Protocol 2: In-Situ Microscopy for Visualizing Nucleation and Dynamic Growth

This protocol couples electrochemistry with real-time visualization to directly observe the early stages of nucleation and growth [4].

Setup Configuration: Integrate an electrochemical workstation with an in-situ optical microscope equipped with a high-resolution digital camera and a long-working-distance objective.

Cell Assembly: Use a specialized electrochemical cell with an optical window. Ensure the working electrode surface is parallel to the window and in clear focus.

Simultaneous Measurement:

- Initiate the potentiostatic deposition as described in Protocol 1.

- Simultaneously record a video or capture images at a defined frame rate (e.g., 1 frame per second) throughout the experiment.

Image and Data Correlation:

- Analyze the video to quantify the number density of nuclei, their growth rates, and any morphological changes (e.g., dendritic vs. spherical growth) over time.

- Correlate the optical observations directly with features in the current-time transient. The current rise should correspond to the appearance and growth of visible nuclei [4].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Electrodeposition Studies.

| Reagent/Category | Example Components | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Salt Precursors | Anhydrous AlCl₃, Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, Co(NO₃)₂·6H₂O | Source of metal ions (Al³⁺, Ni²⁺, Co²⁺) for electrodeposition. Purity and dryness are critical [4] [2]. |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Choline Chloride-Urea, Metal Nitrate-L-Serine | Eco-friendly electrolytes with wide electrochemical windows, suppressing hydrogen evolution [2]. |

| Organic Solvent Electrolytes | N-methylformamide (NMF), Acetamide | Room-temperature electrolytes for metals like Al; act as Lewis bases to form complexes with metal ions [4]. |

| Additives | Niacinamide | Modifies coating properties by adsorbing on the electrode or growing nuclei, affecting roughness and morphology [4]. |

Data Presentation and Analysis

The following table summarizes quantitative data on nucleation parameters from various systems, illustrating how CNT parameters can be experimentally determined.

Table 3: Experimentally Determined Nucleation Parameters in Different Systems.

| System | Nucleation Type / Mechanism | Key Measured Parameters | Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Al from AlCl₃-NMF [4] | 3D nucleation, Diffusion-controlled | Nucleation rate determined from current transients. | Potentiostatic electrodeposition, molar ratios AlCl₃:NMF = 1.0 to 1.5. |

| Ni, Co from Nitrate-L-Serine DES [2] | 3D nucleation, Diffusion-controlled | Modeled with modified Scharifker models integrating proton reduction. | Potentiostatic deposition on glassy carbon electrode. |

| sI CH₄ Hydrate [7] | Homogeneous | Nucleation rate: (3.8–70.4) × 10⁻⁴ s⁻¹ | Onset subcooling (ΔT₀): 3.76 ± 0.52 K |

| sI CO₂ Hydrate [7] | Homogeneous | Nucleation rate: (8.7–66.8) × 10⁻⁴ s⁻¹ | Onset subcooling (ΔT₀): 3.55 ± 0.66 K |

| Ice in TIP4P/2005 Water Model [5] | Homogeneous | Free Energy Barrier (ΔG*): 275 k_BT | Supercooling: 19.5 °C below freezing point. |

Diagram 2: Workflow for potentiostatic nucleation study and interpretation of the current-time transient, showing the three characteristic regions of the nucleation and growth process.

The Role of Overpotential in Driving Nucleation and Growth

In electrodeposition, the process through which metal ions in solution are reduced to form solid metal deposits on an electrode surface, overpotential (η) is the driving force that dictates the initiation and evolution of the deposit's microstructure. This deviation from equilibrium potential is not merely an inefficiency but a fundamental control parameter that governs nucleation density, growth morphology, and ultimately, the functional properties of the electrodeposited material. Understanding its role is critical for advancements in numerous fields, including energy storage systems such as metal batteries and the fabrication of functional coatings with tailored properties.

This Application Note details the principles, measurement techniques, and practical applications of overpotential in the electrochemical nucleation and growth of metal compounds from aqueous solutions. It provides a structured framework for researchers to systematically investigate and manipulate this key parameter to achieve desired material characteristics.

Theoretical Foundations: Overpotential and Nucleation Kinetics

The initial stage of electrodeposition, nucleation, involves the formation of stable, nanoscale clusters of atoms (nuclei) on the electrode surface. The thermodynamic barrier to this process is described by the Gibbs free energy of formation (ΔG), which incorporates both the energy gained from the reduction of metal ions and the energy required to create a new surface.

The Critical Relationship

The applied overpotential directly controls the stability of these nascent nuclei. The critical radius (r_c), which is the minimum size a nucleus must achieve to be stable and continue growing, is inversely proportional to the applied overpotential, as defined by the equation:

r_c = A h σ / (ρ n F η) [8]

where:

- A is a geometric factor

- h is the height of the atom

- σ is the interfacial energy

- ρ is the density

- n is the number of electrons transferred

- F is the Faraday constant

- η is the nucleation overpotential

A higher overpotential results in a smaller critical nucleus size, enabling a greater number of nucleation sites to become stable. This leads to a higher nucleation density, producing a finer and more uniform grain structure in the final deposit [8].

Impact on Nucleation Rate

Furthermore, the nucleation rate (ω), or the number of stable nuclei formed per unit time per unit area, increases exponentially with overpotential:

ω = K exp[-π h σ² L A / (ρ n F η)] [8]

where K is a pre-exponential factor and L is Avogadro's constant. This exponential relationship means that slight adjustments in overpotential can lead to dramatic changes in the nucleation behavior, switching the mechanism from progressive nucleation (where nuclei form at different times) to instantaneous nucleation (where all nuclei form simultaneously) [2] [9].

The diagram below illustrates how overpotential governs the nucleation and growth process, influencing the final deposit's microstructure.

Quantitative Data and Key Relationships

The following tables summarize core quantitative relationships and experimental data from recent research, highlighting the direct impact of overpotential and related parameters on nucleation outcomes.

Table 1: Fundamental Equations Governing Overpotential and Nucleation

| Parameter | Mathematical Relationship | Functional Impact | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Critical Nucleus Radius (rc) | rc = A h σ / (ρ n F η) | Inversely proportional to η. Higher η promotes smaller, more numerous stable nuclei. | [8] |

| Gibbs Free Energy of Nucleation (ΔGc) | ΔGc = π h σ² A / (ρ n F η) | Inversely proportional to η. Higher η lowers the energy barrier for nucleation. | [8] |

| Nucleation Rate (ω) | ω = K exp[-π h σ² L A / (ρ n F η)] | Exponentially increases with η. Small η increases yield large changes in nucleation density. | [8] |

Table 2: Experimentally Observed Effects of Overpotential and Current Density

| System | Condition Change | Observed Effect on Nucleation & Growth | Resulting Coating Property | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn Deposition | η increased from 28.3 mV to 45.9 mV | Smaller critical nucleus size; accelerated nucleation rate. | Dendrite-free, dense Zn plating; high Coulombic efficiency (99.8%). | [8] |

| Ni-Graphene Coating | Current density: 2 A/dm² (optimal) | Dense structure; refined grains; uniform graphene dispersion. | Peak hardness (284 HV), lowest friction (0.43), highest corrosion resistance. | [10] |

| MoS₂ Electrodeposition | Potential: -1.1 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) | Max. nucleation density (N ~10¹⁵). Progressive → Instantaneous nucleation. | Superior HER performance due to high-active-surface-area nanostructures. | [11] |

| Al on AZ31 Mg Alloy | Potentiostatic steps in DES | 3D progressive & instantaneous nucleation; diffusion-controlled growth. | Formation of a corrosion-resistant Al coating. | [9] |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for investigating nucleation and growth mechanisms, focusing on the key technique of chronoamperometry.

Protocol: Investigating Nucleation Mechanism via Chronoamperometry

Objective: To determine the nucleation and growth mode (instantaneous vs. progressive) and extract kinetic parameters by analyzing current-time transients.

Materials and Reagents:

- Electrochemical Cell: Standard three-electrode configuration.

- Working Electrode (WE): Inert substrate (e.g., Pt wire, Glassy Carbon, Cu foil).

- Counter Electrode (CE): Pt mesh or foil.

- Reference Electrode (RE): Suitable for electrolyte (e.g., Ag/AgCl, SCE).

- Electrolyte: Aqueous solution containing the metal ion of interest (e.g., 0.5 mM AgNO₃ + 50 mM NaClO₄ [12]).

- Instrumentation: Potentiostat/Galvanostat.

Procedure:

- Electrode Preparation: Polish the WE sequentially with alumina slurry or sandpaper, then rinse thoroughly with deionized water and dry.

- Cell Setup: Assemble the cell, introduce the electrolyte, and position the electrodes.

- Potential Step Experiment:

- Set the initial potential at a value where no faradaic reaction occurs.

- Apply a series of cathodic potential steps to different overpotentials (e.g., -0.9 V to -1.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl [11]).

- For each step, record the current as a function of time for a sufficient duration (typically 10-200 seconds).

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the non-dimensional curves of (i/im)² vs. (t/tm), where im and tm are the current and time at the peak of the transient.

- Compare the experimental plots with the theoretical models for 3D nucleation:

- Instantaneous Nucleation: (i/im)² = 1.9542 / (t/tm) {1 - exp[-1.2564 (t/tm)]}²

- Progressive Nucleation: (i/im)² = 1.2254 / (t/tm) {1 - exp[-2.3367 (t/tm)²]}²

- A fit with the instantaneous model indicates all nuclei form at the same time, while a fit with the progressive model indicates continuous formation of new nuclei [2] [9].

The workflow for this protocol, from sample preparation to data interpretation, is outlined below.

Advanced Technique: Single-Particle Studies using SECCM

For investigating spatial heterogeneity in nucleation kinetics, Scanning Electrochemical Cell Microscopy (SECCM) is a powerful tool.

- Method: An electrolyte-filled micropipet probe is brought into contact with the substrate, creating a microscopic electrochemical cell. By applying a potential and measuring the current at thousands of individual locations, statistical data on nucleation times (tn) at different applied potentials can be collected [12].

- Analysis: The distribution of tn is analyzed using time-dependent kinetic models to extract meaningful chemical quantities, such as surface energies and kinetic rate constants, moving beyond traditional bulk models [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Electrodeposition Studies

| Item | Function/Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte (e.g., NaClO₄, Na₂SO₄) | Provides ionic conductivity without participating in the reaction; controls the electrical double layer structure. | Used in Ag nucleation studies to maintain conductivity without complexing Ag⁺ [12]. |

| Complexing Agent (e.g., Sodium L-tartrate, L-serine) | Modifies the solvation shell of metal ions, increasing de-solvation energy barrier and nucleation overpotential. | Sodium L-tartrate increases Zn nucleation η, promoting dense deposits [8]. L-serine forms DES with metal nitrates [2]. |

| Surfactant (e.g., C₁₂H₂₅SO₄Na) | Reduces surface tension, prevents agglomeration of nanoparticles, and inhibits pinhole formation. | Improves dispersion of graphene nanoplatelets in Ni–Gr composite coatings [10]. |

| Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES) (e.g., ChCl-Urea, Metal nitrate-L-serine) | Eco-friendly alternative to conventional solvents; wide electrochemical window suppresses hydrogen evolution. | Electrodeposition of Al [9], Ni, and Co [2] without side reactions. |

| Lithiophilic/Metallophilic Sites (e.g., Li₂₂Sn₅ alloy, Sn, rGO framework) | Provides high-binding-energy nucleation sites to reduce nucleation overpotential and guide uniform metal deposition. | Creating 3D Li-Sn alloy anodes for dendrite-free all-solid-state batteries [13]. |

Application Examples in Research

Dendrite Suppression in Zinc Metal Anodes

In aqueous zinc-ion batteries, dendrite growth is a major failure mode. Research shows that adding sodium L-tartrate to the electrolyte increases the nucleation overpotential of Zn from 28.3 mV to 45.9 mV. This higher overpotential drives the formation of a larger number of smaller, stable nuclei, leading to a compact and non-dendritic Zn plating morphology. This regulation significantly improves battery cycling stability and enables a high Zn utilization rate [8].

Optimizing Composite Coating Properties

In the electrodeposition of Ni-Graphene (Ni-Gr) coatings on brass, current density—which directly influences the overpotential—was found to be critical. A current density of 2 A/dm² produced a dense coating with refined grains and uniform graphene dispersion, yielding optimal hardness, wear resistance, and corrosion resistance. Deviations from this optimal density caused grain coarsening and property degradation, demonstrating the need for precise overpotential control to achieve synergistic performance enhancements [10].

Controlled Synthesis of Functional Compounds

The principle extends to metal compounds. During the electrochemical deposition of Mg(OH)₂, a higher current density (overpotential) was found to significantly increase the nucleation and growth rates. By constructing a multi-parameter model linking Mg²⁺ concentration, current density, and temperature, researchers gained a fundamental understanding of the crystallization kinetics, enabling the controlled synthesis of Mg(OH)₂ for applications in flame retardancy and environmental remediation [14]. Similarly, the nucleation mechanism of MoS₂ was found to shift with applied potential, with -1.1 V yielding the highest nucleation density and most active catalyst for the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) [11].

Diffusion-Controlled vs. Electrochemical Polarization-Controlled Growth

In the field of electrodeposition and the synthesis of metal compounds from aqueous solutions, understanding the growth mechanism is fundamental to controlling material properties. The kinetics of electrocrystallization are primarily governed by one of two rate-limiting steps: mass transport of electroactive species to the electrode surface or the charge transfer reaction across the electrode-electrolyte interface. These steps give rise to two distinct operational regimes: diffusion-controlled growth and electrochemical polarization-controlled growth (also referred to as interfacial or charge-transfer control). The precise identification and manipulation of the controlling regime are critical for tailoring deposit morphology, texture, grain size, and application-specific functional properties in fields ranging from battery technology to protective coatings and catalyst design.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Parameters

Electrocrystallization is a multi-step process involving ion transport, electron transfer, and phase formation. The slowest step in this sequence determines the overall growth kinetics and the resulting deposit characteristics.

Diffusion-Controlled Growth

In this regime, the rate of growth is limited by the speed at which metal ions can travel through the solution to the electrode surface. This typically occurs at high overpotentials or in solutions with low ion concentration. The process is described by Fick's laws of diffusion, and the current density (i) exhibits a characteristic decay over time as diffusion zones overlap [15]. This regime often leads to three-dimensional (3D) nucleation and growth and can result in dendritic or powdery deposits if unmanaged [16]. The radius of a hemispherical nucleus growing under pure diffusion control can be derived by combining Faraday's law with the hemispherical diffusion equation [15].

Electrochemical Polarization-Controlled Growth

Here, the growth rate is limited by the intrinsic speed of the electron transfer reaction at the electrode interface. This is also known as "interfacial control" or "charge transfer control" [15]. This regime dominates at lower overpotentials and favors the formation of smoother, more compact, and often finer-grained deposits, as the incorporation of atoms into the crystal lattice is the decisive, slower step.

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of Growth Control Mechanisms

| Feature | Diffusion-Controlled Growth | Electrochemical Polarization-Controlled Growth |

|---|---|---|

| Rate-Limiting Step | Mass transport of ions to the electrode surface [15] | Electron transfer reaction at the interface [15] |

| Governing Equation | Fick's laws of diffusion | Butler-Volmer equation |

| Typical Current Response | Current decays with time (e.g., in a potentiostatic transient) [15] | Current is stable or governed by interface area |

| Common Deposit Morphology | Dendritic, fractal, powdery, 3D structures [16] [15] | Compact, smooth, layered, 2D growth |

| Influencing Factors | Concentration, temperature, hydrodynamic conditions [17] | Overpotential, electrode material, catalytic activity [18] |

| Predominant Model | Scharifker-Hill (SH) model for 3D nucleation [19] [15] | Models of 2D layer-by-layer growth |

Experimental Protocols for Mechanism Identification

Protocol: Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) for Reaction Reversibility Assessment

Objective: To determine the reversibility of the electrode reaction and obtain initial clues about the rate-controlling step [20].

- Cell Setup: Utilize a standard three-electrode cell with a Glassy Carbon (GC) working electrode, a Platinum counter electrode, and a Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE) reference electrode [20].

- Electrolyte Preparation: Prepare a solution of the target metal ion (e.g., 1 × 10⁻⁶ M Paracetamol as a model compound) with a high concentration of supporting electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M LiClO₄) to minimize solution resistance [20].

- Measurement: Purge the solution with nitrogen gas for 15 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen. Run cyclic voltammograms at a series of scan rates (e.g., from 0.025 V/s to 0.300 V/s) [20].

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the peak separation (ΔEp = |Epc - Epa|). A significant increase in ΔEp with increasing scan rate indicates a quasi-reversible or irreversible process, often associated with slow electron transfer (polarization control) or uncompensated resistance [20].

- Plot the peak current (Ip) versus the square root of the scan rate (ν¹/²). A linear relationship is characteristic of a diffusion-controlled process. A linear plot of Ip vs. scan rate (ν) suggests an adsorption-controlled process [20].

Protocol: Chronoamperometry (CA) for Nucleation and Growth Analysis

Objective: To characterize the nucleation mechanism and growth type by analyzing current-time transients [19].

- Cell Setup: Identical to the CV protocol (three-electrode system).

- Potential Step: Apply a sufficient cathodic potential step from a region where no reaction occurs to a potential sufficiently negative to drive deposition. Multiple experiments should be conducted at different overpotentials.

- Data Recording: Record the current response over time until a steady state is reached.

- Data Analysis and Modeling: Compare the experimental current-time (I-t) transients to theoretical models.

- The Scharifker-Hill (SH) model is commonly used for 3D diffusion-controlled nucleation [15] [19].

- The dimensionless (I/Im)² vs. (t/tm) plot is used to discriminate between instantaneous (finite number of nuclei growing at the same time) and progressive (continuous formation of new nuclei) nucleation [19].

- The experimental data is often analyzed using non-linear fitting algorithms (e.g., the Marquardt-Levenberg algorithm) to extract nucleation parameters such as the number of active sites (N₀) and the nucleation rate constant (A) [19].

Protocol: Galvanostatic Intermittent Titration Technique (GITT)

Objective: To probe solid-state diffusion coefficients within alloy electrodes, particularly relevant for battery materials [17].

- Cell Setup: A coin cell or Swagelok cell with a Li metal counter/reference electrode and the alloy working electrode (e.g., Li-Al alloy).

- Measurement: Apply a constant current pulse for a specific duration (e.g., 30 minutes) to insert Li ions, followed by a long rest period (e.g., 2 hours) to allow the system to reach equilibrium. This cycle is repeated throughout the composition range of interest.

- Data Analysis: The voltage change during the pulse and relaxation phases is recorded. The apparent chemical diffusion coefficient of Li⁺ (D~Li~) can be calculated from the potential transients, revealing differences in ion mobility between phases (e.g., a ten-order-of-magnitude difference between α and β Li-Al phases) [17].

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for Identifying Growth Control Mechanisms. CV, CA, and GITT provide complementary data to distinguish between diffusion and polarization control.

Case Studies and Applications

Electrodeposition of Ni-Co-Y₂O₃ Composite Coatings

In the electrodeposition of Ni-Co-Y₂O₃ composite coatings from a sulfamate bath, chronoamperometry studies revealed that the nucleation and growth process for both the alloy and the composite approximately agreed with the Scharifker-Hill instantaneous nucleation model, which is a classic model for 3D diffusion-controlled growth [19]. The incorporation of nano-Y₂O³ particles increased the number of active nucleation sites (N₀) and the nucleation rate (A), leading to a finer-grained, more uniform, and compact deposit [19].

Magnesium Electrodeposition in Batteries

The growth morphology of magnesium metal battery anodes is highly sensitive to operating conditions. While often claimed to be dendrite-free, magnesium can exhibit kinetic-driven 3D growth or diffusion-driven dendritic growth depending on the overpotential and current density [16]. This challenges the presumed safety of Mg metal batteries and underscores the necessity of controlling the growth mechanism to prevent short-circuiting.

Lithium-Aluminum Alloy Negative Electrodes

In solid-state batteries, the Li-Al alloy system demonstrates a profound impact of phase-dependent diffusion on performance. First-principles calculations predict a ten-order-of-magnitude difference in the Li diffusion coefficient between the Li-poor α-phase (D~Li~ ≈ 10⁻¹⁷ cm²/s) and the Li-rich β-phase (D~Li~ ≈ 10⁻⁷ cm²/s) [17]. Electrodes with a higher fraction of the β-LiAl phase provide fast lithium diffusion channels, switching the rate limitation from solid-state diffusion to other processes and enabling superior rate capability (up to 7 mA cm⁻²) [17].

Real-Time Tracking of Copper Nucleation

Advanced optical techniques like Wide-Field Surface Plasmon Resonance Microscopy (WF-SPRM) allow real-time tracking of individual nanoscale nuclei. Studies on copper electrodeposition show that the growth kinetics of individual nuclei transition from a charge-transfer limitation to a diffusion limitation as the reaction progresses and the overpotential increases [21]. This technique visually confirms the overlap of diffusion fields between neighboring nuclei, a hallmark of diffusion-controlled growth [21].

Table 2: Quantitative Data from Case Studies

| System | Key Parameter | Value / Observation | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Li-Al Alloy Phases [17] | Li⁺ Diffusion Coefficient in β-LiAl | ~10⁻⁷ cm²/s | Provides fast ion-conduction channels |

| Li⁺ Diffusion Coefficient in α-Al | ~2.6 × 10⁻¹⁷ cm²/s | Acts as a diffusion barrier, trapping Li | |

| Ni-Co-Y₂O₃ Electrodeposition [19] | Nucleation Mechanism | Fits instantaneous 3D model | Growth is diffusion-controlled |

| Effect of Y₂O₃ | Increased N₀ and A | Promotes finer grain structure | |

| Paracetamol Electro-oxidation [20] | Ipc/Ipa ratio | 0.59 ± 0.03 | Coupled chemical reaction consumes product |

| ΔEp at ν=0.300 V/s | 0.186 V | Quasi-reversible electron transfer |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Electrodeposition Studies

| Item | Function / Purpose | Example from Context |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte | To eliminate ionic migration by providing excess inert ions and to reduce solution resistance. | LiClO₄ [20] |

| Complexing Agents | To shift the deposition potential, modify deposition kinetics, and improve deposit quality. | Oxalate, Citrate, Thiocyanate (for Sm deposition) [22] |

| Nano-Particles (for composites) | To incorporate into a metal matrix to enhance properties like hardness, wear, and corrosion resistance. | Nano-Y₂O₃ particles in Ni-Co matrix [19] |

| Non-Aqueous Solvents | To provide a wide electrochemical window for depositing reactive metals and to avoid hydrogen evolution. | Dimethylformamide (DMF), Acetonitrile (AN) [22] |

| Reference Electrode | To provide a stable and known reference potential for accurate control and measurement of the working electrode potential. | Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE) [20] [19] |

| Working Electrode Substrates | The surface upon which electrodeposition occurs; its nature and pretreatment significantly affect nucleation. | Glassy Carbon (GC), Copper plate, Gold film (for WF-SPRM) [20] [21] [19] |

The deliberate selection and control between diffusion-controlled and electrochemical polarization-controlled growth is a cornerstone of advanced electrodeposition research. As evidenced by the case studies, the governing growth mechanism directly dictates the structural and functional outcomes of the deposited material—be it a thin film, a composite coating, or a battery electrode. The experimental protocols outlined, supported by modern characterization techniques, provide a robust framework for researchers to diagnose and manipulate these fundamental processes. A deep understanding of these principles is indispensable for the rational design of next-generation materials in metallurgy, energy storage, and functional coatings.

Traditional models of electrochemical nucleation and growth often depict a simple, direct pathway from dissolved metal ions to crystalline bulk metal. However, advanced in-situ analysis techniques have revealed that non-classical pathways, involving multi-step nucleation and aggregative growth mechanisms, are prevalent in the electrodeposition of metal compounds from aqueous solutions. These complex processes significantly influence the final morphology, size, and properties of electrodeposited metallic coatings and nanoparticles [2] [23]. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for researchers and scientists aiming to design nanomaterials with precise functional properties for applications in catalysis, sensing, and biomedical devices [23].

This document outlines the core principles of these non-classical pathways, provides quantitative data on specific metal systems, and details the experimental protocols required for their investigation.

Key Mechanisms and Experimental Evidence

Non-classical electrodeposition involves mechanisms where growth proceeds not solely by ion-by-ion addition, but through the aggregation of pre-formed nanoclusters. The following table summarizes the key mechanisms and findings from recent studies:

Table 1: Experimental Evidence for Non-Classical Nucleation and Growth Mechanisms

| Metal System | Electrolyte | Key Finding | Mechanism | Supporting Technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silver (Ag) [23] | 1 mM AgNO₃ in 50 mM KNO₃ | Nucleation numbers from electrochemistry and AFM do not match; growth involves aggregation and detachment. | Nucleation-Aggregative Growth-Detachment | Macroscale electrochemistry, AFM, SECCM |

| Nickel-Cobalt (Ni-Co) [2] | Metal nitrate-L-Serine Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES) | J-t transients cannot be fitted with classic models; requires integration of proton reduction/adsorption. | Multi-step nucleation integrated with parasitic reactions | Potentiostatic current-time transient analysis |

| Aluminum (Al) [4] | AlCl₃-N-methylformamide (NMF) organic solvent | Transient current involves double-layer charging, 3D nucleation-growth, and reduction of residual water on nuclei. | Multi-step 3D nucleation-growth with side reactions | Chronoamperometry, In-situ optical microscopy |

| Nickel-Tungsten (Ni-W) [24] | Aqueous solution | Initial growth involves formation, movement, and aggregation of atoms, single crystals, and nanoclusters (~10 nm). | Aggregation of nanoclusters | SEM, AFM, TEM |

The proposed nucleation-aggregative growth-detachment mechanism for silver nanoparticles on Highly Oriented Pyrolytic Graphite (HOPG) suggests that after initial reduction, nanoclusters do not simply grow in place but can detach and re-attach to larger particles, leading to a final distribution of nanoparticles that cannot be explained by classical models alone [23].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Investigating Aggregative Growth using Scanning Electrochemical Cell Microscopy (SECCM)

This protocol is adapted from studies on silver electrodeposition on HOPG [23].

1. Primary Solution Preparation:

- Prepare an aqueous solution of 1 mM silver nitrate (AgNO₃) and 50 mM potassium nitrate (KNO₃) as a supporting electrolyte using ultra-pure water (>18 MΩ cm at 25 °C).

2. SECCM Pipette Fabrication and Setup:

- Pull a theta pipette to a sharp taper using a laser puller.

- Fill both barrels of the pipette with the prepared electrolyte solution.

- Insert a silver wire (Quasi-Reference Counter Electrode, QRCE) into each barrel.

- Mount the pipette above the working electrode (e.g., a freshly cleaved HOPG substrate) connected as the working electrode and held at ground.

3. Nanoscale Electrodeposition and Measurement:

- Lower the pipette towards the substrate at a controlled rate (e.g., 200 nm s⁻¹) until a measurable current is detected, indicating meniscus contact.

- Set the deposition potential by adjusting the potential of the QRCEs with respect to the grounded working electrode.

- Apply a potential step to initiate deposition and record the current-time response.

- Monitor the resistance between the two QRCEs before and after experiments to confirm meniscus stability.

4. Data Analysis:

- Analyze the current-time transients to identify individual nucleation and aggregation events.

- Correlate electrochemical data with ex-situ microscopy (e.g., AFM) to compare electrochemically inferred nucleus densities with physically observed densities.

Protocol: Analyzing Multi-Step Nucleation in Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES)

This protocol is adapted from the study of Ni and Co electrodeposition from L-Serine-based DES [2].

1. DES Electrolyte Synthesis:

- Weigh metal nitrate hexahydrate (e.g., Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O or Co(NO₃)₂·6H₂O) and L-serine in a molar ratio of 2:1 into a beaker.

- Stir the mixture at 60 °C until a homogeneous liquid is formed.

2. Electrochemical Cell Setup:

- Employ a standard three-electrode cell configuration.

- Use the metal substrate of interest (e.g., glassy carbon) as the working electrode.

- Use a platinum gauze as the counter electrode and a silver wire as a quasi-reference electrode.

3. Potentiostatic Current Transient Measurement:

- Hold the working electrode at a pre-treatment potential (+400 mV vs. QRCE for 180 s) to ensure a clean surface.

- Step the potential to a predetermined cathodic deposition potential.

- Record the current as a function of time for the duration of the deposition (typically several seconds).

4. Model Fitting and Analysis:

- Fit the obtained current-time (j-t) transients using integrated models that account for:

- Electric double-layer charging.

- 3D nucleation and growth of metal (e.g., using Scharifker-Mostany model).

- Concurrent side reactions (e.g., proton reduction and adsorption).

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the generalized multi-step experimental workflow for probing non-classical nucleation mechanisms, integrating the protocols above.

Experimental Workflow for Nucleation Studies

The conceptual pathway of non-classical nucleation and aggregative growth is complex. The following diagram maps out the key stages involved in the formation of a metal nanoparticle via these mechanisms.

Non-Classical Nucleation & Aggregative Growth

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Example Specification / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES) [2] | Eco-friendly electrolyte alternative; wide electrochemical window, suppresses hydrogen evolution. | E.g., Metal nitrate (Ni, Co) + L-Serine (2:1 molar). Avoids costly Choline Chloride. |

| AlCl₃-N-methylformamide [4] | Room-temperature, low-cost organic solvent electrolyte for Al electrodeposition. | Prepared in argon-glove box; molar ratios from 1.0 to 1.5 (AlCl₃:NMF). |

| Silver Nitrate (AgNO₃) [23] | Precursor for silver nanoparticle electrodeposition, a model system for nucleation studies. | Typically 1 mM concentration with 50 mM KNO₃ supporting electrolyte. |

| Highly Oriented Pyrolytic Graphite (HOPG) [23] | Model electrode substrate with a well-defined basal plane and step edges to study nucleation sites. | Freshly cleaved with adhesive tape before each experiment. AM grade recommended for large terraces. |

| Scanning Electrochemical Cell Microscopy (SECCM) [23] | A pipette-based technique for performing electrochemistry at nanoscale spatial resolution. | Uses theta pipettes; allows study of intrinsic basal plane activity without step edge influence. |

| Quasi-Reference Counter Electrode (QRCE) [23] [2] | A simple wire (e.g., Ag) acting as both reference and counter electrode in confined cells or non-aqueous electrolytes. | Potential is reported relative to the relevant metal/metal ion couple (e.g., Ag/Ag⁺). |

Key Rate-Controlling Steps in the Electrodeposition Chain Reaction

Electrodeposition is a versatile technique for synthesizing functional metal coatings with controlled phase, composition, and morphology. This chain reaction involves multiple consecutive steps where the overall deposition rate is governed by the slowest, rate-controlling step. Understanding these individual steps—metal ion transport, electron transfer, and nucleation/growth—is crucial for precisely controlling coating properties from nanometer to micrometer scales [2]. In aqueous solutions, this process is particularly complex due to competing parasitic reactions such as hydrogen evolution, which leads to hydrogen embrittlement and reduced Coulombic efficiency [2] [25]. This Application Note examines the key rate-controlling steps within the electrodeposition chain reaction, providing detailed protocols for mechanistic analysis and strategies for optimizing coating quality.

Theoretical Background: The Electrodeposition Chain Reaction

The electrodeposition chain reaction comprises three principal, sequential steps: mass transport of metal ions from the bulk solution to the electrode interface, electrochemical charge transfer leading to the formation of ad-atoms, and nucleation and growth of stable clusters into a continuous coating. The slowest of these steps dictates the overall deposition rate and final coating characteristics.

Nucleation Mechanisms

The initial nucleation stage typically follows one of two primary models, which can be distinguished through chronoamperometric analysis:

- Instantaneous Nucleation: All nucleation sites are activated simultaneously at the beginning of the process, and growth proceeds primarily from these fixed nuclei.

- Progressive Nucleation: Nucleation sites are activated continuously throughout the deposition process, leading to the formation of new nuclei alongside the growth of existing ones.

For many systems, including Ni-Co alloys and related composites, the nucleation/growth process approximately follows the Scharifker-Hill instantaneous nucleation model [19]. However, recent studies on novel deep eutectic solvents (DES) have shown that simply applying traditional models like Scharifker-Mostany is insufficient, necessitating the development of new models that integrate parallel processes such as proton reduction and adsorption [2].

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Rate-Controlling Steps

Protocol 1: Chronoamperometric Analysis of Nucleation Mechanism

Objective: To determine the nucleation mechanism and calculate key nucleation parameters for an electrodepositing system.

Materials:

- Potentiostat/Galvanostat with data acquisition software

- Standard three-electrode cell

- Working electrode (WE): Substrate of interest (e.g., copper plate, graphite flake, low-carbon steel)

- Counter electrode (CE): Platinum mesh or nickel sheet

- Reference electrode (RE): Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE) or Ag/AgCl

- Electrolyte: Prepared deposition bath containing metal ions

Procedure:

- Electrode Preparation: Polish the working electrode sequentially with 400, 800, and 1200-grit emery papers. Wash with distilled water and activate in 5% HCl solution for 10 seconds [19].

- Cell Setup: Assemble the three-electrode cell in a thermostated water bath to maintain constant temperature (± 2°C).

- Potential Step Experiment: Step the working electrode potential from a value where no deposition occurs to a predetermined deposition potential (e.g., from -0.2 V to -1.20 V vs. SCE). Record the current transient for 120 seconds [19].

- Data Analysis: Plot the dimensionless current-time transient and compare it with theoretical models for instantaneous and progressive nucleation.

- Parameter Calculation: Use the Marquardt-Levenberg algorithm or similar fitting procedures to calculate nucleation parameters including the number of active nucleation sites (N₀) and nucleation rate (A) [19].

Protocol 2: Linear Sweep Voltammetry for Electrochemical Behavior

Objective: To investigate the effect of additives and particles on cathodic polarization and deposition onset potential.

Materials: (Same as Protocol 1)

Procedure:

- System Preparation: Set up the three-electrode system as described in Protocol 1.

- Potential Scan: Scan the potential from the open circuit potential in the cathodic direction (e.g., from 0 V to -2.0 V vs. SCE) at a fixed scan rate (e.g., -30 mV/s) [19].

- Data Interpretation: Note the shift in deposition onset potential and changes in current density with the addition of particles or changes in electrolyte composition.

Protocol 3: Electrochemical Mass Spectrometry for Complex Reactions

Objective: To deconvolute the rates of individual steps in complex electrocatalytic reactions by quantifying gaseous products.

Materials:

- Electrochemical Mass Spectrometry (EC-MS) system

- Thin-layer electrochemical cell

- Gas-tight system components

Procedure:

- Cell Configuration: Assemble a thin-layer EC-MS cell with a platinized platinum working electrode in a stagnant configuration.

- Potential Programming: Apply carefully designed electrode potential programs to isolate individual reaction steps.

- Product Quantification: Use mass spectrometry to directly quantify CO₂ evolution (via m/z 16 signal) or other gaseous products during constant-potential oxidation or potential oscillation programs [26].

- Step Rate Calculation: Map the potential dependence of each principal reaction step and assess its contribution to the overall reaction rate.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Quantitative Nucleation Parameters from Model Systems

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Nucleation Parameters for Different Coating Systems

| Coating System | Electrolyte | Applied Potential | Nucleation Model | Nucleation Parameters | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MnO₂ on Graphite | 0.14 M MnSO₄ | 2.0 V vs. SCE | Four-stage process with instantaneous nucleation | Incubation period: ~1.5 s; Nuclei connection time: ~0.5 s | [27] |

| Ni-Co Alloy | Sulfamate bath | -1.05 to -1.20 V vs. SCE | Instantaneous nucleation | Baseline parameters for comparison | [19] |

| Ni-Co-Y₂O₃ Composite | Sulfamate bath with 10 g/L Y₂O₃ | -1.05 to -1.20 V vs. SCE | Instantaneous nucleation | Higher N₀ and A values vs. Ni-Co alloy | [19] |

| Ni/W from DES | Ni(NO₃)₂·L-serine DES | - | Integrated model (adsorption + nucleation) | Requires accounting for proton reduction | [2] |

Advanced Model Development for Complex Systems

Table 2: Key Rate-Controlling Factors in Different Electrolyte Systems

| Electrolyte System | Key Advantages | Primary Rate-Controlling Challenges | Mitigation Strategies | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aqueous Solution | High solubility, good mass transfer | Hydrogen evolution reaction, narrow potential window | Additives, pH control, pulsed electrodeposition | [25] |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Wide stability window, suppressed H₂ evolution | Complex nucleation with parallel reactions | Integrated models combining adsorption and nucleation | [2] |

| Ionic Liquids | Tunable properties, wide potential window | High viscosity limiting mass transport | Temperature control, forced convection | [25] |

| Molten Salts | High conductivity, no solvation | High temperature, corrosive environment | Material selection, potential control | [25] |

Case Study: Overcoming Step Misalignment in Electrodeposition

A fundamental limitation in electrodeposition chain reactions arises when different steps reach their optimal rates at different potentials. This misalignment significantly limits the overall deposition rate under constant potential conditions [26].

In the electrodeposition of Ni-Co alloys from metal nitrate-L-serine deep eutectic solvents, researchers found that traditional Scharifker-Mostany models failed to fully fit the current-time transients. This necessitated the development of new models that integrate proton reduction and adsorption processes with electrochemical nucleation and growth [2].

Solution: Potential Oscillation By applying alternating potentials to individually optimize adsorption and oxidation steps, researchers achieved deposition rates exceeding those under constant-potential operation. This approach overcomes the inherent limitation of step misalignment in the electrodeposition chain reaction [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Electrodeposition Studies

| Reagent/Material | Typical Composition/Properties | Primary Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sulfamate Plating Bath | Ni(NH₂SO₃)₂·4H₂O (80 g/L), Co(NH₂SO₃)₂·4H₂O (16 g/L), H₃BO₄ (40 g/L) | Source of Ni²⁺ and Co²⁺ ions; pH buffer | Electroplating of Ni-Co alloys and composites [19] |

| L-Serine DES | M(NO₃)₂·6H₂O (M = Ni, Co) + L-serine (2:1 molar ratio) | Eco-friendly electrolyte with wide stability window | Electrodeposition of Ni, Co and their alloys [2] |

| Nano-Y₂O₃ Particles | Average diameter ~50 nm | Grain refiner, enhances coating properties | Co-deposition in Ni-Co-Y₂O₃ composite coatings [19] |

| Lactate-Based Alkaline Bath | Nickel salts, tungsten salts, lactate ions | Ligand for tunable W content in alloys | Electrodeposition of nanostructured Ni-W alloys [28] |

| Manganese Sulfate Solution | 0.14 M MnSO₄ in distilled water | Source of Mn²⁺ ions for anodic deposition | Potentiostatic deposition of porous MnO₂ coatings [27] |

Identifying and understanding the key rate-controlling steps in the electrodeposition chain reaction is fundamental to advancing materials design for functional applications. Through the application of chronoamperometry, linear sweep voltammetry, and advanced techniques like electrochemical mass spectrometry, researchers can deconvolute complex deposition processes and develop targeted strategies for optimization. The emerging approach of using non-stationary potential programs to overcome inherent limitations in constant-potential deposition represents a promising direction for achieving higher deposition rates and superior coating properties. As electrodeposition continues to evolve toward more complex multi-component systems and sustainable electrolyte alternatives, the fundamental principles of nucleation and growth kinetics will remain essential for rational process design.

Synthesis and Control: Techniques for Tailoring Metal Compound Properties in Aqueous Media

Potentiostatic and Galvanostatic Electrodeposition Methodologies

Electrodeposition is a versatile technique for synthesizing functional metal coatings with controlled phase, composition, and morphology. The precise control over current, charge, and applied potential during electrodeposition directly influences nucleation and growth kinetics, which ultimately determines the structural characteristics of the deposited material from nanometer to micrometer scales [2]. The selection of appropriate electrochemical methodology—potentiostatic (constant potential) or galvanostatic (constant current)—represents a fundamental consideration in experimental design, with significant implications for nucleation mechanisms, growth dynamics, and final deposit properties. Within the broader context of research on electrodeposition nucleation and growth of metal compounds from aqueous solutions, understanding the comparative advantages, limitations, and specific applications of these two approaches is essential for optimizing deposition outcomes across various material systems and research objectives.

Fundamental Principles and Comparative Analysis

Operational Definitions

Potentiostatic electrodeposition maintains a constant potential between the working and reference electrodes throughout the deposition process. This approach directly controls the driving force for electrochemical reactions, yielding a current that fluctuates in response to changing surface conditions, nucleation events, and diffusion layer development [2] [4].

Galvanostatic electrodeposition maintains a constant current between the working and counter electrodes during deposition. This method directly controls the rate of electrochemical reaction, resulting in a potential that varies dynamically to sustain the specified current density as surface morphology and electrochemical conditions evolve [29].

Comparative Performance Characteristics

Table 1: Comparative analysis of potentiostatic versus galvanostatic electrodeposition methodologies.

| Parameter | Potentiostatic Mode | Galvanostatic Mode |

|---|---|---|

| Controlled Variable | Potential (V) | Current (A) |

| Measured Response | Current (A) | Potential (V) |

| Nucleation Control | Direct through overpotential | Indirect through current density |

| Growth Kinetics | Diffusion-controlled | Interface-controlled |

| Optimal Application | High-impedance systems (coatings, corrosion-resistant materials) | Low-impedance systems (batteries, supercapacitors) |

| Stability with Drifting OCV | Problematic if corrosion potential drifts | Maintains true zero-current condition |

| Process Automation | Complex due to current monitoring | Simplified due to constant current |

For systems where the open-circuit voltage (OCV) may drift during measurement, galvanostatic control provides a significant advantage by maintaining the desired zero-current condition throughout the experiment, ensuring measurements occur at the true corrosion potential [30]. Conversely, potentiostatic mode excels in high-impedance systems where minimal current flow must be precisely controlled, such as in corrosion-resistant coatings and detailed nucleation studies [30].

Experimental Protocols

Potentiostatic Electrodeposition of Metallic Coatings from Deep Eutectic Solvents

Principle: This protocol describes the potentiostatic electrodeposition of nickel, cobalt, and their alloys from metal nitrate-L-serine deep eutectic solvents (DES). The potentiostatic approach enables detailed study of nucleation and growth mechanisms through current-transient analysis [2].

Materials and Reagents:

- Metal salts: Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, Co(NO₃)₂·6H₂O (anhydrous, ≥99%)

- L-serine (amino acid, ≥98%)

- Working electrode: Glassy carbon, platinum, or metal substrates

- Counter electrode: Platinum mesh or wire

- Reference electrode: Ag/Ag⁺ or suitable alternative compatible with DES

DES Electrolyte Preparation:

- Weigh M(NO₃)₂·6H₂O (M = Ni or Co) and L-serine in a molar ratio of 2:1

- Combine materials in a beaker and stir at 60°C until a homogeneous liquid forms

- For alloy deposition, prepare mixed metal salts with L-serine maintaining total metal to serine ratio of 2:1

- Characterize electrochemical properties including viscosity and conductivity prior to deposition

Electrodeposition Procedure:

- Set up standard three-electrode electrochemical cell under controlled atmosphere

- Determine deposition potential range through cyclic voltammetry (typically -0.8V to -1.4V vs. Ag/Ag⁺)

- Apply predetermined deposition potential for specific duration (typically 100-1000 seconds)

- Monitor current-time transients for nucleation analysis

- Remove substrate, rinse thoroughly with appropriate solvent, and dry under inert atmosphere

Data Analysis:

- Analyze current-time transients using integrated models incorporating proton reduction and adsorption with Scharifker-Mostany model for monometallic deposition

- For alloy deposition, apply Scharifker model incorporating multiple reduction processes

- Characterize deposit morphology using SEM, composition using EDS, and structure using XRD

Galvanostatic Anodization and Electrodeposition for SERS Substrates

Principle: This protocol describes the fabrication of TiO₂/Ag substrates for Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) applications, combining galvanostatic anodization of titanium with pulsed current electrodeposition of silver nanostructures. The galvanostatic approach enables precise control over nanostructure morphology and growth rates [29].

Materials and Reagents:

- Titanium foil (grade II, 10 × 10 × 0.1 mm)

- Ammonium fluoride (NH₄F, ≥99%)

- Monoethylene glycol (MEG, anhydrous)

- Silver nitrate (AgNO₃, ≥99%)

- Sodium nitrate (NaNO₃, ≥99%)

- Acetone, ethanol, deionized water

TiO₂ Nanostructure Preparation (Galvanostatic Anodization):

- Clean titanium foils in sequential 10-minute ultrasonic baths of acetone, ethanol, and deionized water

- Prepare electrolyte containing 0.6 wt% NH₄F, 2% deionized water in MEG

- Assemble two-electrode system with Ti foil anode and graphite rod cathode (1 cm separation)

- Apply constant current density (5-30 mA/cm²) for 30 minutes with magnetic stirring

- Monitor voltage response throughout anodization process

- Rinse anodized samples with deionized water and ethanol

- Anneal in air at 450°C for 4 hours to crystallize TiO₂

Silver Electrodeposition (Pulsed Galvanostatic):

- Configure two-electrode system using anodized TNS substrates as cathode and Pt sheet as anode

- Prepare aqueous deposition solution containing 10 mM AgNO₃ and 100 mM NaNO₃

- Apply pulsed current deposition (5 mA/cm², 400 cycles) with 50 ms ON/250 ms OFF times

- Control pulses using automated system (e.g., Arduino-based controller)

- Rinse substrates thoroughly with deionized water and dry in air

Performance Evaluation:

- Evaluate SERS performance using methylene blue as probe molecule (10 μL aliquot)

- Characterize morphology by SEM, determine crystal phase by Raman spectroscopy

- Calculate analytical enhancement factor (AEF) from intensity measurements

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for electrodeposition studies.

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Salts | Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, Co(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, AlCl₃ (anhydrous, ≥99%) | Metal ion source for deposition | Ni, Co, Al deposition from DES [2] [4] |

| Deep Eutectic Solvent Components | L-serine, Choline chloride, Urea (≥98%) | Eco-friendly electrolyte solvent | Alternative to aqueous electrolytes [2] |

| Titanium Substrate | Grade II foil (10 × 10 × 0.1 mm) | Anodization substrate | TiO₂ nanotube fabrication [29] |

| Anodization Electrolyte | NH₄F (0.6 wt%), H₂O (2%) in MEG | Fluoride source for TiO₂ dissolution | TiO₂ nanostructure formation [29] |

| Silver Salts | AgNO₃ (≥99%) | Silver ion source for electrodeposition | SERS substrate fabrication [29] |

| Supporting Electrolytes | NaNO₃ (≥99%) | Ionic conductivity enhancement | Pulsed electrodeposition [29] |

Quantitative Data Analysis and Interpretation

Current Transient Analysis in Potentiostatic Deposition

For potentiostatic deposition, current-time transients provide critical information about nucleation and growth mechanisms. In metal nitrate-L-serine DES systems, the current transient typically exhibits three distinct regions [2]:

- Initial sharp decay: Corresponding to double-layer charging

- Subsequent rising current: Indicating progressive nucleation and three-dimensional growth

- Final decay: Resulting from diffusion-controlled growth and overlap of diffusion zones

Advanced analysis requires integrated models that account for simultaneous processes including proton reduction and adsorption alongside metal deposition. The Scharifker-Mostany model provides the theoretical framework for instantaneous and progressive nucleation discrimination, with modifications necessary for accurate fitting of experimental data from novel electrolyte systems [2].

Voltage Response in Galvanostatic Deposition

During galvanostatic anodization, the voltage-time response reveals critical information about the formation and growth of nanostructured oxides [29]:

- Initial voltage rise: Corresponding to barrier layer formation

- Voltage stabilization: Indicating equilibrium between oxide growth and dissolution

- Morphology determination: Different voltage profiles correlate with specific nanostructure morphologies (nanotubes vs. nanograss)

For TiO₂ anodization at 15 mA/cm², the optimal voltage stabilizes at approximately 40-60 V, producing nanostructures that maximize SERS enhancement factors up to 7×10⁷ when decorated with silver dendrites [29].

Table 3: Quantitative parameters for electrodeposition optimization.

| System | Optimal Parameter | Value | Resulting Property |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ni-Co/L-Serine DES | Deposition Potential | -1.1V to -1.3V vs. Ag/Ag⁺ | Continuous, uniform alloy deposits [2] |

| AlCl₃-NMF System | molar ratio | 1:1.3 to 1:1.5 | Optimal viscosity and conductivity [4] |

| TiO₂ Anodization | Current Density | 15 mA/cm² | Maximum SERS enhancement [29] |

| Ag Pulsed Electrodeposition | Pulse Parameters | 5 mA/cm², 50 ms ON/250 ms OFF | Dendritic nanostructures [29] |

The selection between potentiostatic and galvanostatic electrodeposition methodologies represents a critical decision point in experimental design for metal deposition research. Potentiostatic control offers superior capability for fundamental nucleation studies and high-impedance systems, enabling detailed mechanistic understanding through current-transient analysis. Galvanostatic control provides advantages for systems with drifting potentials and industrial processes requiring precise thickness control, particularly in low-impedance applications such as battery materials and SERS substrates. The continuing development of novel electrolyte systems, including deep eutectic solvents and room-temperature ionic liquids, further expands the application potential of both methodologies. Future research directions should focus on hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of both techniques, real-time monitoring of nucleation events, and advanced modeling that incorporates multi-step reduction processes and additive effects to achieve unprecedented control over metallic deposit properties.

Analyzing Nucleation Mechanisms with Chronoamperometry (Current Transients)

The electrodeposition of metals and metal compounds is a fundamental process in materials science, playing a critical role in applications ranging from corrosion-resistant coatings and energy storage devices to catalyst fabrication. The functional properties of these deposited materials—including their morphology, adhesion, porosity, and electrical performance—are intrinsically governed by the initial nucleation and growth stages of the electrocrystallization process [31]. Understanding and controlling these early stages is therefore essential for tailoring materials for specific advanced applications.

Chronoamperometry, the technique of applying a constant potential and monitoring the resulting current transient over time, serves as a powerful in situ tool for probing nucleation mechanisms. The characteristic shape of the current-time (i-t) transient provides a real-time fingerprint of the electrocrystallization process [31]. This application note, framed within a broader thesis on electrodeposition, details how researchers can leverage chronoamperometry to distinguish between different nucleation mechanisms and extract quantitative kinetic parameters for metal deposition from aqueous solutions.

Theoretical Foundations of Nucleation Analysis

Electrocrystallization is a multi-step chain reaction where metal ions in solution are reduced at the electrode surface, form ad-atoms, and subsequently incorporate into crystallization sites [31]. The overall process can be limited by different rate-controlling steps, broadly classified into two categories for nucleation and growth:

- Diffusion-Controlled Growth: The growth rate of nuclei is limited by the mass transport of electroactive species from the bulk solution to the electrode surface. This is the most common scenario in metal electrodeposition [31].

- Electrochemical Polarization-Controlled Growth: The growth rate is limited by the kinetics of the charge transfer reaction itself, with the current described by the Butler-Volmer equation [31].

In diffusion-controlled systems, the current transient exhibits a characteristic rise to a maximum (i_m) at a time (t_m) due to the formation and growth of new nuclei and the expansion of their diffusion zones. After the peak, the current decays as these diffusion zones overlap and the growth is constrained [9]. The analysis of these non-dimensional i/i_m vs. t/t_m plots allows for direct comparison with established theoretical models.