Electrochemical Deposition vs. CVD for Inorganic Crystals: A Comprehensive Guide for Material Scientists

This article provides a systematic comparison between electrochemical deposition and chemical vapor deposition (CVD) for synthesizing inorganic crystals, targeting researchers and professionals in materials science and drug development.

Electrochemical Deposition vs. CVD for Inorganic Crystals: A Comprehensive Guide for Material Scientists

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison between electrochemical deposition and chemical vapor deposition (CVD) for synthesizing inorganic crystals, targeting researchers and professionals in materials science and drug development. It explores the fundamental principles, nucleation mechanisms, and energy dynamics governing each technique. The scope covers methodological workflows, key applications across semiconductors, energy storage, and biomedical coatings, and direct comparisons of material properties. The content also addresses practical challenges, offering troubleshooting strategies and optimization guidelines for process control, scalability, and material quality. Designed to inform material selection and process development, this review synthesizes technical insights with application-oriented analysis to guide the implementation of these critical fabrication technologies.

Core Principles and Growth Mechanisms of Electrochemical Deposition and CVD

The synthesis of inorganic crystals and functional thin films is a cornerstone of modern materials science, with broad applications in electronics, energy storage, catalysis, and protective coatings. Two dominant methodologies for producing these materials are solution-phase electrochemical reduction (electrodeposition) and vapor-phase chemical reactions, most notably Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD). These techniques operate on fundamentally different principles, involving distinct process mechanisms, experimental parameters, and resulting material properties.

Electrochemical reduction occurs in a liquid electrolyte, where dissolved metal ions are reduced on a substrate surface to form coatings or crystals. In contrast, vapor-phase CVD involves the thermal decomposition of gaseous precursor molecules on a heated substrate, leading to film growth. This guide provides a systematic comparison of these two foundational processes, highlighting their mechanisms, performance characteristics, and ideal application spaces to inform selection for specific research and development goals.

Fundamental Mechanisms and Pathways

The core distinction between these techniques lies in their reaction environments and the fundamental physics governing the deposition process.

Solution-Phase Electrochemical Reduction

This process is an electrically driven reaction occurring at the interface between a solid electrode and a liquid electrolyte. The key steps, as exemplified by Ni-Al₂O₃ composite coating deposition, include [1]:

- Mass Transport: Dissolved metal ions (e.g., Ni²⁺) and additive particles (e.g., Al₂O₃) are transported to the cathode surface through agitation and diffusion.

- Electron Transfer: Upon reaching the cathode, metal ions gain electrons and are reduced to their metallic state (e.g., Ni²⁺ + 2e⁻ → Ni⁰).

- Nucleation and Growth: Reduced atoms form nucleation sites, which grow into a crystalline or amorphous coating. Co-deposition of inert particles like Al₂O₃ can create composite coatings with enhanced properties [1].

Vapor-Phase Chemical Reactions (CVD)

CVD is a thermally driven process where film growth occurs from the gas phase. The fundamental steps, as illustrated in Figure 1(a) of the search results, involve [2]:

- Precursor Delivery and Gas Phase Reactions: Gaseous precursors are transported into a reaction chamber and may undergo homogenous gas-phase reactions.

- Surface Adsorption and Diffusion: Precursor molecules adsorb onto the heated substrate surface and diffuse across it.

- Heterogeneous Reaction and Nucleation: The adsorbed species undergo thermal decomposition or reaction with other gases, forming solid nuclei on the substrate.

- Film Growth: Nuclei grow through the continued incorporation of reaction products, forming a dense film [2].

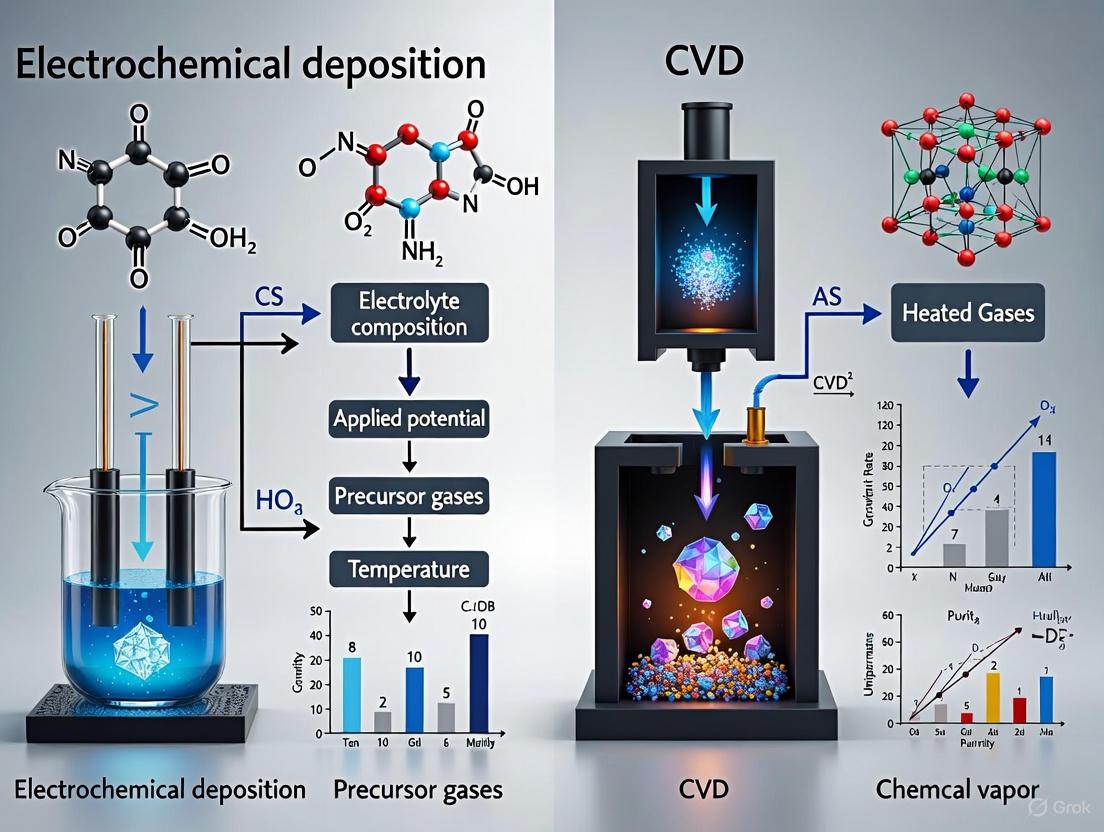

The workflow diagrams below contrast the sequential steps of these two fundamental deposition mechanisms.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for solution-phase electrochemical reduction (electrodeposition), illustrating the sequence from substrate preparation to film growth [1].

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for a typical vapor-phase Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) process, showing the path from precursor preparation to film growth [2].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

The fundamental differences in mechanism lead to distinct performance outcomes, which can be quantified through key metrics such as deposition rate, microstructure control, and material properties.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Comparative performance metrics for electrodeposition and CVD processes.

| Performance Metric | Solution-Phase Electrodeposition | Vapor-Phase CVD |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Deposition Rate | High (e.g., ~µm/min for Ni-Al₂O₃) [1] | Low to Medium [2] |

| Process Temperature | Near ambient (e.g., Room Temp - 80°C) [1] | High (e.g., 200°C > 1000°C) [2] |

| Microstructure Control | Good control over grain size and texture via current density and chemistry [1] | Excellent control over crystallinity, density, and phase via temperature and pressure [2] |

| Film Conformality | Poor on complex geometries | Excellent, uniform coverage on complex 3D structures [2] |

| Typical Film Density | Moderate, can be porous | Very high, pinhole-free [2] |

| Coating Composition | Pure metals, alloys, composites (e.g., Ni-Al₂O₃) [1] | Pure elements, ceramics, nitrides, carbides, complex functional oxides [2] |

| Energy Consumption | Primarily electrical energy for reduction | Primarily thermal energy for precursor decomposition and substrate heating [2] |

Impact of Process Parameters on Material Properties

Experimental data demonstrates how process inputs determine final material characteristics. In electrodeposition, the current density and bath chemistry critically determine the texture orientation and microstructure of the resulting coatings [1]. For instance, the concentration of boric acid in a Watts-type nickel plating bath can shift the preferential crystal orientation from (200) to (220), directly influencing hardness and wear resistance [1].

In CVD, the substrate temperature and precursor chemistry are paramount. Recent advances show that applying external electric or magnetic fields during CVD can exert additional control at the microscale, enabling low-temperature deposition, selected area deposition, and directional grain growth, thus transcending restrictions imposed by macroscopic parameters alone [2].

Experimental Protocols

This section outlines standard experimental methodologies for both techniques, providing a foundational protocol for researchers.

Table 2: Key reagent solutions for Ni-Al₂O₃ composite electrodeposition.

| Reagent Solution | Function in the Process |

|---|---|

| Watts Bath Electrolyte (Nickel Sulfate, Nickel Chloride, Boric Acid) | Provides Ni²⁺ ions for reduction; chloride minimizes anode passivation; boric acid acts as a pH buffer. |

| Al₂O₃ Powder (α-phase) | Reinforcement particles to form a composite coating, enhancing hardness and wear resistance. |

| Acetone | Solvent for degreasing and cleaning the substrate before deposition to ensure good adhesion. |

| Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) Pickling Solution | Removes surface oxides and impurities from the substrate prior to electrodeposition. |

- Substrate Preparation: Use medium carbon steel discs. Embed in phenolic resin to define a working surface area. Polish to a mirror finish. Clean and degrease by immersion in acetone, followed by rinsing with distilled water. Perform acid pickling in 50 g/L HCl solution at 40°C for one minute to remove surface oxides, then rinse and dry.

- Electrolyte Preparation: Prepare a standard Watts bath electrolyte containing nickel sulfate (240-320 g/L), nickel chloride (45-60 g/L), and boric acid (30-40 g/L). Add α-Al₂O₃ powder (10-25 g/L) as the reinforcement phase. Use magnetic stirring (e.g., 600 rpm for 16 hours) to ensure a homogeneous suspension.

- Electrodeposition Setup: Use a high-purity nickel plate as the soluble anode. Connect the prepared substrate as the cathode. Maintain a set distance (e.g., 2 cm) between the electrodes.

- Process Execution: Deposit using direct current (DC). Key parameters to control and optimize include:

- Current density: 2-5 A/dm²

- Agitation rate: 200-350 rpm

- Deposition time: 15-60 minutes

- Bath temperature: 40-60°C

- Post-Processing: After deposition, rinse the coated substrate with distilled water and dry. Characterization of coating properties can include microhardness testing, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) for morphology, energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) for composition, and X-ray diffraction (XRD) for crystallinity.

- Substrate Preparation and Loading: The substrate (e.g., silicon wafer) is meticulously cleaned using standard procedures (e.g., RCA clean) to remove organic and ionic contaminants. It is then loaded into the CVD reactor chamber.

- Reactor Evacuation and Heating: The reactor chamber is evacuated to a base pressure and purged with an inert gas. The substrate is heated to the desired deposition temperature using resistive heating (hot-wall CVD) or by heating only the substrate holder (cold-wall CVD).

- Precursor Delivery and Deposition: The precursor(s) are delivered into the chamber. This may involve:

- Bubbling: An inert carrier gas (e.g., Ar, N₂) is bubbled through a liquid precursor to transport its vapor.

- Direct Flow: For gaseous precursors (e.g., SiH₄, CH₄).

- The precursor flow rates, chamber pressure, and substrate temperature are maintained for a set duration to achieve the target film thickness.

- Chamber Purge and Cool Down: After the deposition cycle, precursor flows are stopped, and the chamber is purged with inert gas to remove any unreacted precursors and byproducts. The substrate is then cooled to room temperature under vacuum or inert atmosphere before being unloaded.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Selecting the correct precursors and reagents is critical for successfully executing either deposition technique and achieving the desired material properties.

Table 3: Essential materials and their functions for electrodeposition and CVD processes.

| Material / Reagent | Function / Role | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Salts (e.g., NiSO₄) | Source of metal ions (Mⁿ⁺) for reduction at the cathode. | Electrodeposition of pure Ni and Ni-composite coatings [1]. |

| Soluble Anode (e.g., Ni plate) | Replenishes metal ions in the solution and maintains electrical circuit. | Prevents depletion of Ni²⁺ ions in a Watts bath during DC electrodeposition [1]. |

| Boric Acid (H₃BO₃) | pH buffer agent in the electrolyte. | Maintains stable pH at the cathode-solution interface during nickel electrodeposition [1]. |

| Reinforcement Particles (e.g., Al₂O₃, YSZ) | Second-phase particles to form composite coatings. | Co-deposited with Ni to enhance microhardness and wear resistance [1]. |

| Volatile Precursors (e.g., Metalorganics, Halides) | Source of material to be deposited in gaseous form. | TiCl₄ and CH₄ are used in the CVD of TiC coatings [2]. |

| Carrier Gas (e.g., Ar, N₂, H₂) | Transports precursor vapors into the reaction chamber; can be reactive (H₂) or inert (Ar). | Hydrogen can act as a reducing agent in the CVD of metals from their halides [2]. |

| Reactive Gases (e.g., O₂, NH₃, CH₄) | React with precursor vapors to form the desired solid phase (oxide, nitride, carbide). | Oxygen is used for growing SiO₂ from SiH₄; ammonia for forming BN from BF₃ [2]. |

Solution-phase electrochemical reduction and vapor-phase CVD offer distinct pathways for materials synthesis, each with its own strengths and ideal applications.

Solution-Phase Electrodeposition is highly suited for depositing thick, metallic coatings and composites on simpler geometries where its cost-effectiveness, high deposition rates, and ability to form metal-matrix composites are major advantages. Its limitations typically lie in lower throwing power for complex shapes and generally less-precise microstructural control compared to CVD.

Vapor-Phase CVD excels in applications demanding high-purity, dense, and conformal films with superior control over crystallinity, stoichiometry, and microstructure. It is the preferred method for coating complex 3D structures and for depositing a vast range of non-metallic materials, including ceramics and semiconductors. The primary trade-offs often involve higher operational temperatures, more complex equipment, and the need for volatile precursors.

The choice between these two fundamental process mechanisms ultimately depends on the specific material system, the required film properties, the substrate limitations, and the economic constraints of the intended application. Advances in both fields, such as pulsed electrodeposition for grain refinement and field-enhanced CVD for low-temperature processing, continue to push the boundaries of their capabilities.

The pursuit of advanced materials in modern technology is fundamentally rooted in the precise control of thin film synthesis. Nucleation and growth kinetics represent a critical domain of study, dictating the structural, morphological, and functional properties of coatings and layers used across industries from microelectronics to energy storage. Two dominant methodologies—electrochemical deposition (ECD) and chemical vapor deposition (CVD)—offer distinct pathways for material fabrication, each governed by unique mechanisms and kinetic principles [3]. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these techniques, focusing on their application in growing inorganic crystals and thin films. It synthesizes current research to equip scientists and engineers with the necessary insights for selecting and optimizing deposition processes for specific research and development goals, framed within a broader thesis on inorganic materials synthesis.

Fundamental Principles and Kinetic Frameworks

Electrochemical Deposition (ECD) Kinetics

Electrochemical deposition is a solution-based process where ions in an electrolyte are reduced on a conductive substrate to form a solid phase. The kinetics are primarily driven by applied potential and are often described by classical nucleation theory (CNT).

- Nucleation Mechanism: The process initiates with the formation of stable atomic clusters, overcoming a free energy barrier. The free energy of formation for a cluster of size n is given by ΔGf,n = ΔG0n + kbTχn2/3, where the surface energy term creates an energetic barrier [4]. The critical nucleus size, beyond which growth becomes favorable, is defined by this maximum.

- Growth Dynamics: Following nucleation, growth proceeds via kinetically controlled or diffusion-controlled pathways, significantly influencing the final microstructure [5]. The growth rate and morphology can be tailored by parameters such as overpotential, ion concentration, and electrolyte pH [6].

- Site Selectivity: A key characteristic of ECD is its propensity for preferential nucleation at edge planes and surface defects. Studies on CVD-grown monolayer graphene show that MoO2 nanowires selectively nucleate at edge plane sites, affirming their higher electrochemical reactivity compared to the basal plane [7].

Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) Kinetics

Chemical vapor deposition involves the thermal decomposition and reaction of gaseous precursors on a heated substrate, resulting in the formation of a solid film.

- Nucleation Mechanism: In contrast to ECD, CVD nucleation involves precursor adsorption, surface diffusion, and decomposition [8]. The growth is typically atom-by-atom or molecule-by-molecule, with the growth plane often determined by the surface nucleation stage with the lowest energy [9].

- Energetics and Activation: Traditional CVD relies on high temperatures (600–800°C) to drive precursor decomposition. However, Plasma-Enhanced CVD (PECVD) utilizes a high-energy stream of ionized molecules to lower the required substrate temperature to a range of 200–400°C, enabling deposition on temperature-sensitive materials [10].

- Morphological Control: The growth of specific crystal structures, such as two-dimensional inorganic molecular crystals (2DIMCs), can be challenging due to weak crystalline anisotropy. Innovative approaches like Passivator-Assisted Vapor Deposition (PAVD) use passivators to suppress low-energy planes and promote lateral, two-dimensional growth [9].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental pathways from initial precursor/ion to final film structure for both ECD and CVD.

Comparative Performance Analysis

The choice between ECD and CVD significantly impacts the properties and performance of the resulting materials. The following tables provide a quantitative and qualitative comparison based on experimental data.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics and Process Conditions

| Feature | Electrochemical Deposition (ECD) | Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Driving Force | Applied electrical potential [11] [6] | Thermal energy (precursor decomposition) [8] [10] |

| Process Medium | Liquid electrolyte (aqueous/organic) [3] [6] | Vapor/gas phase [8] [9] |

| Typical Operating Temperature | Near room temperature to 90°C [11] | Thermal CVD: 600–800°CPECVD: 200–400°CPIB-CVD: Room Temperature [10] |

| Deposition Rate | High, tunable via current density | Variable, depends on precursor flux and temperature |

| Key Controlled Parameters | Potential/current, electrolyte composition, pH [6] | Temperature, pressure, precursor gas flow rate [8] |

| Energy Consumption Profile | Lower thermal energy, electrical energy for ion reduction | High thermal energy for precursor cracking and substrate heating |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics for Specific Material Systems

| Material / Application | Method | Key Performance Metrics & Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silicon-based Anodes for Li-ion batteries | ECD vs. CVD | ECD: Simple, flexible, low-cost, long cycle life. CVD: High-quality, uniform films, but often requires higher temperatures. | [3] |

| ZnO Nanowires | ECD | Growth on Graphene/Cu: Smaller diameter nanowires, stronger photoluminescence emission compared to growth on bare Cu. | [11] |

| 2D Sb₂O₃ Molecular Crystals | PAVD (CVD variant) | Achieved monolayer thickness (~0.64 nm), lateral size >20 µm. Passivator enables 2D growth by suppressing low-energy planes. | [9] |

| Copper/Copper Oxide Composites | ECD | Formation of Cu₂O crystals possible by controlling overpotential and local pH. Crystal shape and geometry tunable via deposition time. | [6] |

| Diamond Coatings on WC-Co tools | CVD (with ECD pretreatment) | ECD Pretreatment: Selective Co removal (from 6.1% to 0.3%), surface polishing. CVD: Subsequent high-quality, adherent diamond coating. | [12] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Electrochemical Deposition of ZnO Nanowires

This protocol, adapted from the synthesis of ZnO nanowires on CVD-graphene/Cu electrodes, highlights a typical ECD workflow for growing functional metal oxide nanostructures [11].

- Electrolyte Preparation: Prepare an aqueous solution of 100 mM Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O and 100 mM KNO₃. KNO₃ acts as a supporting electrolyte to enhance conductivity.

- Substrate Preparation: Use a conductive substrate such as a Cu foil or a Cu foil coated with CVD-grown graphene. Clean the substrate thoroughly with solvents (e.g., acetone, isopropanol) and dry.

- Electrochemical Setup: Employ a standard three-electrode system.

- Working Electrode: The prepared substrate (Cu or G/Cu).

- Counter Electrode: A Pt mesh.

- Reference Electrode: A saturated calomel electrode (SCE) or Ag/AgCl.

- Deposition Parameters: Maintain the electrolyte temperature at 90°C. Apply a constant cathodic potential between -0.8 V and -1.2 V (vs. Ref.) for a defined period (e.g., 30-60 minutes) without stirring.

- Post-Deposition Handling: After deposition, rinse the sample thoroughly with distilled water to remove residual salts and dry in air or under a nitrogen stream.

Protocol for Passivator-Assisted CVD of 2D Sb₂O₃ Crystals

This protocol details the synthesis of two-dimensional inorganic molecular crystals, showcasing a advanced CVD approach [9].

- Setup Configuration: Use a three-zone tube furnace. Place atomically flat mica substrates in the downstream region of the quartz tube.

- Precursor and Passivator Loading:

- Route 1 (InCl₃ assisted): Place hydrophilic SbCl₃·xH₂O precursor in the upstream zone and InCl₃ passivator in a separate boat in the central zone.

- Route 2 (Se assisted): Use Se powder as the passivator instead of InCl₃.

- Gas Environment and Heating: Evacuate the tube and maintain a constant argon flow. Heat the precursor zone to 320°C to generate SbOCl vapor. Simultaneously, heat the substrate zone to 400°C.

- Reaction and Growth: The vapors (SbOCl, H₂O, and passivator) are transported to the hot substrate zone where they react to form Sb₂O₃ flakes. The passivator critically suppresses heterophase nucleation and promotes lateral growth.

- Termination and Characterization: After a growth period (e.g., 30 minutes), cool the furnace to room temperature under argon flow. The resulting ultrathin flakes can be characterized by AFM, Raman spectroscopy, and SEM.

The workflow below visualizes the key stages of a generalized CVD process, including the crucial role of a passivator.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful deposition requires careful selection of precursors, substrates, and other reagents. The following table outlines key materials used in the featured ECD and CVD experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function / Role | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O | Source of Zn²⁺ ions in the electrolyte for ECD. | Electrochemical deposition of ZnO nanowires [11]. |

| KNO₃ | Supporting electrolyte; increases conductivity without participating in the reaction. | Electrochemical deposition of ZnO nanowires [11]. |

| Copper(II) Sulphate (CuSO₄) | Source of Cu²⁺ ions for electrodeposition of copper and its oxides. | Formation of Cu/Cu₂O nanocomposite coatings [6]. |

| SbCl₃·xH₂O | Vapor-phase precursor supplying SbOCl for Sb₂O₃ formation. | PAVD growth of 2D Sb₂O₃ molecular crystals [9]. |

| InCl₃ / Se Powder | Passivator agent; controls nucleation plane and suppresses 3D growth in CVD. | PAVD growth of 2D Sb₂O₃ molecular crystals [9]. |

| Methane (CH₄) | Carbon source gas for CVD growth of graphene. | CVD synthesis of graphene on Cu substrates [11]. |

| CVD-Graphene/Cu | Conductive substrate with modified surface properties. | Provides a surface for controlled nucleation and growth of ZnO nanowires via ECD [11]. |

| Cemented Carbide (WC-Co) | Substrate for hard coatings. Requires pretreatment for CVD. | Substrate for CVD diamond coatings after ECD cobalt removal [12]. |

Application-Specific Performance and Selection Guidelines

The optimal deposition technique is largely determined by the target application, as each method offers distinct advantages for specific material properties and performance requirements.

Energy Storage Materials (e.g., Li-ion Battery Anodes): For silicon-based anodes, ECD is valued for its simplicity, low cost, and ability to produce films with a long cycle life [3]. It allows for the creation of nanostructured and composite films that can accommodate volume changes during lithiation. Conversely, CVD can produce high-purity, uniform silicon thin films, though often at a higher cost and temperature.

Wear-Resistant and Hard Coatings: CVD is the dominant technique for applying ultra-hard coatings like diamond. A key challenge is the detrimental effect of cobalt in WC-Co substrates. Here, ECD pretreatment proves highly effective by selectively etching surface cobalt, creating an ideal surface for subsequent high-quality, adherent CVD diamond growth [12].

Electronic and Optoelectronic Devices: CVD is unparalleled for producing high-quality, large-area semiconductor films, such as graphene and 2D molecular crystals [9] [7]. ECD finds a complementary role in the functionalization of these materials; for instance, by selectively depositing metal oxides like MoO₂ onto the edge planes of graphene to create nanowires or modify electronic properties [7].

Low-Temperature and Sensitive Substrate Processing: When deposition on plastics, pre-fabricated electronics, or other temperature-sensitive materials is required, low-temperature ECD and plasma-enhanced CVD (PECVD or PIB-CVD) are the primary options. PIB-CVD, in particular, offers room-temperature deposition with high tunability of film properties, making it suitable for flexible electronics and display manufacturing [10].

The synthesis of inorganic crystals is a cornerstone of modern materials science, underpinning advancements in fields ranging from electronics to drug delivery. The properties of these crystals—and their subsequent applications—are intrinsically governed by the methods used to create them. Among the myriad of synthesis techniques, chemical vapor deposition (CVD) and electrochemical deposition (ED) represent two pivotal approaches with distinct philosophies towards energy input and the subsequent activation of chemical reactions. This guide provides an objective comparison of these techniques, focusing on how thermal, plasma, and electrical energy inputs direct reaction pathways and influence the characteristics of the resulting inorganic crystals. Framed within contemporary materials research, which increasingly leverages artificial intelligence and autonomous experimentation for synthesis optimization [13] [14], this comparison aims to equip researchers with the data needed to select and optimize the appropriate synthesis method for their specific application.

Fundamental Principles and Energy Coupling Mechanisms

The primary distinction between CVD and ED lies in their phase transition pathways and how energy is coupled into the system to drive reactions.

Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) is a process where solid material is deposited onto a substrate through the vapor-phase chemical reaction of precursors [2]. In thermal CVD, the necessary activation energy for precursor decomposition and surface reactions is supplied entirely as heat, often requiring high temperatures (several hundred to over a thousand degrees Celsius) [2]. This thermal energy overcomes the activation barriers for gas-phase and surface reactions. In plasma-enhanced CVD (PECVD), a non-thermal plasma provides an alternative energy pathway. Here, energetic electrons within the plasma generate highly reactive species (ions, radicals, and excited molecules) through electron-impact collisions, enabling these reactions to proceed at significantly lower substrate temperatures [2] [15].

Electrochemical Deposition (ED) is a solution-based process where electrical energy directly drives the reduction of metal ions at a cathode (substrate), leading to the formation of a solid crystalline film [16]. The key controlled parameter is the applied current or potential, which governs the reduction rate and supersaturation level of metal hydroxides or metals at the electrode-solution interface, thereby controlling nucleation and growth [16].

Table 1: Comparison of Fundamental Reaction Mechanisms and States of Matter.

| Feature | Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) | Electrochemical Deposition (ED) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Energy Input | Thermal, Photonic, or Plasma (Electrical) | Electrical (Potential/Current) |

| Reaction Phase | Vapor-Phase to Solid-Phase | Liquid-Phase (Solution) to Solid-Phase |

| Core Mechanism | Chemical decomposition/reaction of precursors on a heated substrate or via plasma activation. | Electrochemical reduction of metal ions at a cathode. |

| Key Controlled Parameters | Substrate temperature, pressure, precursor gas flow rates, plasma power. | Applied current density/potential, electrolyte concentration, temperature, pH. |

| Typical By-products | Gaseous reaction products (e.g., H₂, HCl, CO₂). | Molecular Hydrogen (H₂), pH changes in electrolyte. |

Comparative Analysis of Synthesis Outcomes and Performance

The different energy input mechanisms of CVD and ED directly translate to variations in the capabilities, performance, and resulting material properties of each technique.

Process Capabilities and Material Characteristics

CVD is renowned for producing high-purity, dense, and conformal thin films with excellent adhesion on complex geometries [2]. It is the industry standard for applications requiring extreme fidelity, such as semiconductor devices and high-performance coatings. The use of plasma enhancement (PECVD) extends these benefits to temperature-sensitive substrates like polymers [2] [15]. In contrast, ED excels in its relatively low energy consumption, operational simplicity, and suitability for continuous production [16]. It is particularly effective for producing high-purity crystals and is easily scalable. However, its product morphology can be sensitive to electrolyte composition and local pH changes at the electrode [16].

Quantitative Performance Data

The following table summarizes key performance metrics and experimental parameters for the two techniques, drawing from specific experimental studies on magnesium hydroxide ED and general CVD processes.

Table 2: Experimental Parameters and Synthesis Outcomes for Inorganic Crystal Growth.

| Parameter / Outcome | Electrochemical Deposition (for Mg(OH)₂) | Chemical Vapor Deposition (General) |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Near-ambient (e.g., 30-70°C) [16] | Several hundred °C (Thermal CVD); Near-ambient to ~300°C (PECVD) [2] [15] |

| Energy Input Control | Current Density (e.g., 1.25 - 5.00 mA/cm²) [16] | Substrate Temperature, Plasma Power |

| Key Precursor/Electrolyte | Mg²⁺ concentration (e.g., 0.05-0.20 mol/L) [16] | Metal-organic or halide precursors in vapor phase [2] |

| Growth Rate | Highly dependent on current density and ion concentration [16] | Governed by temperature and precursor flux [2] |

| Process Pressure | Atmospheric | Sub-atmospheric to Atmospheric [2] |

| Crystal Quality / Purity | High product purity [16] | High purity, dense, conformal films [2] |

| Notable Findings | Nucleation rate increases exponentially with current density; Growth rate peaks at intermediate Mg²⁺ concentration [16]. | Plasma allows low-temp deposition; External fields (E/M) can control texture and density [2]. |

Experimental Protocols for Technique-Specific Synthesis

Protocol: Electrochemical Deposition of Mg(OH)₂ Crystals

This protocol is adapted from the study on understanding the nucleation and growth of magnesium hydroxide [16].

1. Materials and Setup:

- Electrolyte: Aqueous solution of MgCl₂·6H₂O (e.g., 0.10 mol/L).

- Electrodes: A suitable cathode (e.g., platinum or stainless steel) and an inert anode.

- Cell: A three-electrode electrolysis cell equipped with a real-time microzone pH sensor near the cathode surface.

- Instrumentation: Potentiostat/Galvanostat for precise current control.

2. Experimental Procedure:

- Prepare the MgCl₂ electrolyte solution in deionized water.

- Place the cathode and anode in the solution, ensuring the pH sensor is positioned in the cathode microzone.

- Set the bath temperature to a specific value (e.g., 50°C) using a thermostat.

- Apply a constant current density (e.g., 2.5 mA/cm²) across the electrodes.

- Monitor the pH change in the cathode microzone in real-time; a sharp increase signifies the onset of OH⁻ generation and the nucleation induction period.

- Continue the deposition for a set duration to achieve the desired crystal thickness.

- Remove the cathode, rinse with deionized water, and dry to obtain the Mg(OH)₂ crystals.

3. Data Analysis:

- The nucleation induction period (t_ind) is determined as the time between applying the current and the observed sharp inflection in the microzone pH [16].

- Nucleation and growth rates are calculated based on ex-situ characterization of the crystals (e.g., using microscopy) correlated with the applied current density and ion concentration.

Protocol: Plasma-Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition (PECVD)

This protocol outlines a generalized PECVD process for thin-film deposition, as reviewed in recent literature [2].

1. Materials and Setup:

- Precursors: Volatile precursor gases or vapors (e.g., metalorganics, SiH₄).

- Substrate: Properly cleaned substrate (e.g., silicon wafer, glass).

- Reactor: A vacuum-compatible PECVD reactor chamber (e.g., Dielectric Barrier Discharge - DBD type).

- Gas System: Mass flow controllers for precise delivery of precursor and carrier gases.

- Plasma Source: RF or microwave power source with matching network.

2. Experimental Procedure:

- Load the substrate into the reactor and evacuate the chamber to a base pressure.

- Introduce the precursor and carrier gases (e.g., Ar, H₂) at controlled flow rates to achieve the desired working pressure.

- If required, heat the substrate to a moderate temperature (e.g., 100-300°C).

- Ignite the plasma by applying RF/microwave power at a defined density.

- Maintain the deposition for a set time to achieve the target film thickness.

- Terminate the plasma power, stop the precursor flow, and allow the system to cool under an inert gas atmosphere.

- Remove the deposited sample for characterization.

3. Data Analysis:

- Film properties are characterized using techniques like spectroscopic ellipsometry (thickness), X-ray diffraction (crystallinity), and scanning electron microscopy (morphology and conformity).

Reaction Pathways and Workflow Visualization

The distinct reaction pathways for ED and PECVD are visualized below, highlighting the sequence of events from energy input to crystal formation.

Diagram 1: A comparison of the primary reaction pathways in Electrochemical Deposition (top, red) and Plasma-Enhanced CVD (bottom, blue). Each pathway begins with an electrical energy input but proceeds through fundamentally different physical and chemical steps to form the final inorganic crystal film.

The workflow for modern materials discovery, which often involves autonomous optimization of these techniques, is illustrated below.

Diagram 2: The closed-loop workflow for autonomous experimentation (Self-Driving Labs) applied to materials synthesis. This AI-driven approach iteratively designs, executes, and analyzes experiments to rapidly optimize synthesis parameters or test hypotheses for both CVD and ED processes [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This section details key reagents and materials essential for conducting experiments in electrochemical deposition and chemical vapor deposition.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for CVD and Electrochemical Deposition.

| Item Name | Function / Application | Technical Specification / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Metalorganic Precursors | Source of metallic element in CVD. Volatile compounds transported in vapor phase. | e.g., Trimethylaluminum (TMA) for Al, Tetraethylorthosilicate (TEOS) for Si. High purity required [2]. |

| MgCl₂·6H₂O | Source of Mg²⁺ ions in the electrochemical deposition of magnesium hydroxide. | Analytical grade. Concentration in electrolyte directly influences supersaturation and growth kinetics [16]. |

| Inert Carrier Gas | Transport medium for vapor precursors in CVD. | e.g., High-purity Argon (Ar) or Nitrogen (N₂). Flow rate is a critical process parameter [2]. |

| Potentiostat/Galvanostat | Instrument for controlling current or potential in electrochemical deposition. | Must provide stable, precise control of current density, a key variable governing nucleation rates [16]. |

| Microzone pH Sensor | In-situ monitoring of local pH changes near the cathode during electrochemical deposition. | Crucial for real-time determination of the nucleation induction period [16]. |

| Dielectric Barrier Discharge (DBD) Reactor | Generating non-thermal plasma for PECVD. | Allows low-temperature deposition on sensitive substrates. Configuration impacts plasma-catalyst contact [2] [17]. |

The selection of appropriate synthesis techniques is fundamental to advancing materials science, as the method of fabrication directly dictates a material's fundamental properties and its suitability for advanced applications. Among the plethora of available techniques, electrochemical deposition (ECD) and chemical vapor deposition (CVD) have emerged as two of the most pivotal and widely adopted methods for creating thin films, coatings, and complex material architectures. ECD, a solution-based process, leverages electrical currents to reduce metal ions from an electrolyte onto a conductive substrate, enabling the formation of metallic and composite coatings at relatively low temperatures [18]. In contrast, CVD involves the vapor-phase transport and reaction of precursor molecules on a heated substrate, resulting in the deposition of high-purity, dense films of metals, semiconductors, nitrides, and complex oxides [2] [19]. The intrinsic characteristics of these processes—including their underlying mechanisms, operational parameters, and material compatibility—make them uniquely suited for specific material classes and end-use applications.

This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of ECD and CVD, focusing on their application across key material systems from elemental metals to complex oxides and nitrides. By synthesizing current experimental data and detailing standard research protocols, this analysis aims to equip researchers and development professionals with the necessary insights to select the optimal deposition technique for their specific material challenges, particularly within the context of electrochemical and inorganic crystals research.

Comparative Analysis: Electrochemical Deposition vs. Chemical Vapor Deposition

The following section provides a direct, data-supported comparison of the core characteristics, performance, and material outputs of ECD and CVD processes.

Table 1: Core Characteristics and Process Parameters

| Feature | Electrochemical Deposition (ECD) | Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Electrochemical reduction of ions from a solution onto a conductive substrate [18]. | Vapor-phase chemical reactions of precursors on a heated substrate [2]. |

| Typical Materials | Elemental metals (e.g., Cu), Alloys, Metal oxides (e.g., Cu₂O), Composites (e.g., Metal/CNT) [18]. | Nitrides (e.g., TiCN), Oxides, Elemental semiconductors, 2D materials (e.g., Graphene), Complex oxides [2] [19] [20]. |

| Standard Temperature | Near ambient to moderate (e.g., room temperature to ~90°C) [18]. | High temperature (e.g., 300°C to 1000°C+) [2] [19]. |

| Key Parameters | Applied voltage/current, electrolyte composition/pH, deposition time [18]. | Substrate temperature, precursor chemistry & flow rate, chamber pressure [2]. |

| Growth Rate | High (can exceed 1 µm/min) [18]. | Low to Moderate (nm to µm per hour) [2]. |

| Film Conformality | Varies; can be excellent on complex geometries. | Excellent, providing uniform and conformal coatings [2]. |

| Vacuum Required | No | Yes (for most variants) |

| Relative Cost | Lower | Higher |

Table 2: Performance and Material Properties of Representative Coatings

| Material System | Deposition Technique | Key Experimental Conditions | Resulting Properties / Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Copper / Cu₂O Crystals [18] | ECD | Solution: 1-100 mM CuSO₄, Voltage: 7.0 V, Substrate: CNT-coated stainless steel | Formation of various crystal forms; Raman spectroscopy identified pure Cu and Cu(I) oxide (Cu₂O) crystals. |

| TiCN Coatings [19] | CVD | Temp: ~1000°C, Precursor: TiO₂ & C powder, Reactive gas: N₂ | Hardness: ~28 GPa; Roughness: Increased from 40.88 nm to 48.25 nm with N₂ flow; Superior corrosion resistance vs. uncoated substrate. |

| Graphene Electrodes [20] | CVD | Temp: 1000°C, Precursors: CH₄ & H₂ gas, Substrate: Cu foil | High conductivity; uniform 2D structure; used as a base electrode for biomolecule immobilization. |

| CNT Conductive Coatings [21] | EPD (a type of ECD) | Voltage: 40 V, Time: 30-90 s, Suspension: CNTs in isopropanol | Resistance dropped to as low as 0.2 kΩ; homogeneous and compact CNT coatings on polymer mats. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for researchers, this section outlines the detailed methodologies from several seminal studies cited in the comparison tables.

Protocol 1: Electrochemical Deposition of Copper/Copper(I) Oxide Nanocomposites

This protocol, adapted from a 2023 study, details the formation of nanocomposites composed of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and copper-based crystals on a stainless steel substrate [18].

- Substrate Preparation: Austenitic chromium-nickel steel (AISI 304) plates are mechanically ground and ultrasonically cleaned in acetone and ethanol [18].

- CNT Functionalization: Multi-walled CNTs are chemically oxidized in a 3:1 (v/v) mixture of sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄) and nitric acid (HNO₃) at 70°C for 4 hours to introduce negatively charged carboxyl groups [18].

- Electrophoretic Deposition (EPD) of CNTs:

- Dispersion Preparation: Oxidized CNTs are dispersed in a 2:1:1 (v/v/v) mixture of acetone, ethanol, and distilled water at a concentration of 1 mg/mL, followed by sonication for 5 minutes [18].

- Process: The stainless steel substrate (anode) is placed between two counter electrodes (cathodes). A constant voltage of 30 V is applied for 60 seconds to deposit a layer of CNTs. The sample is then dried at room temperature [18].

- Electrochemical Deposition (ECD) of Copper Species:

- Electrolyte Preparation: An aqueous solution of copper(II) sulphate (CuSO₄) is prepared. Concentrations of 1 mM and 100 mM are used to vary crystal morphology [18].

- Process: The CNT-coated substrate acts as the cathode. Electrochemical deposition is performed at a constant voltage of 7.0 V for durations ranging from 60 to 600 seconds [18].

- Characterization: The resulting samples are characterized using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), Electron Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS), Raman spectroscopy, and Grazing Incidence X-ray Diffraction (GIXD) to analyze morphology, composition, and crystal structure [18].

Protocol 2: CVD of TiCN Hard Coatings

This protocol describes the synthesis of titanium carbonitride (TiCN) coatings at high temperature via CVD, as reported in a 2020 study [19].

- Substrate Preparation: A p-type c-Si (100) substrate is meticulously cleaned using the standard RCA (Radio Corporation of America) cleaning technique to remove organic and metallic contaminants [19].

- Precursor Loading: Titanium dioxide (TiO₂) and carbon (C) base powders are mixed in a 1:1 ratio and placed in a ceramic boat, which is then positioned in the heating zone of a horizontal CVD chamber. The silicon substrate is placed adjacent to the powder mixture [19].

- CVD Process:

- The chamber is sealed, and the temperature is raised to a constant, high value (specific to the reactor).

- Nitrogen (N₂) gas is introduced into the chamber as the reactive gas. The flow rate of N₂ is a critical parameter, with variations (e.g., 50, 100, 150 sccm) used to control coating properties [19].

- The deposition is carried out for a fixed duration at the target temperature [19].

- Post-Processing & Characterization: After deposition, the coated substrates are analyzed for surface morphology (SEM, AFM), microstructure (XRD), electrochemical corrosion resistance, and nanomechanical properties (nanoindentation for hardness) [19].

Protocol 3: CVD of Monolayer Graphene and Electrode Fabrication

This protocol covers the growth and transfer of high-quality graphene for electrochemical applications [20].

- Substrate Preparation: A copper foil (30 µm thick) is cleaned with ultrasonic waves in DI water, ethanol, and acetone [20].

- CVD Growth:

- PMMA-Assisted Graphene Transfer:

- A layer of Poly-methyl methacrylate (PMMA) is spin-coated onto the graphene/copper foil [20].

- The underlying copper is etched away by floating the sample on a 0.5 M Fe(NO₃)₃ solution [20].

- The PMMA/graphene layer is rinsed in DI water and transferred onto a target substrate (e.g., SiO₂/Si) [20].

- The PMMA is finally dissolved by immersing the sample in acetone overnight [20].

- Electrode Fabrication: Electrical contacts are formed by thermally evaporating nickel (10 nm) and gold (50 nm) layers onto the edge of the transferred graphene film [20].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical progression and key decision points in selecting and applying ECD and CVD for different material systems, based on the experimental data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successful execution of ECD and CVD research relies on a suite of high-purity reagents and materials. The following table details key items and their functions as derived from the cited experimental protocols.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function / Application | Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Copper(II) Sulphate (CuSO₄) | Source of Cu²⁺ ions for electrochemical deposition of copper and copper oxide crystals [18]. | Used in 1 mM and 100 mM concentrations to control crystal formation during ECD [18]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Used as a conductive scaffold or reinforcing phase in composite coatings; can be deposited via EPD [18] [21]. | Electrophoretically deposited on stainless steel before Cu ECD [18]. |

| High-Purity Acids (H₂SO₄, HNO₃) | Chemical functionalization of nanomaterials (e.g., CNTs) to introduce surface charge for dispersion and deposition [18]. | Used in a 3:1 mixture for oxidizing CNTs to enable EPD [18]. |

| Methane (CH₄) & Hydrogen (H₂) | Common precursor and carrier/reducing gas in CVD for growing carbon-based nanomaterials and thin films [2] [20]. | Used as carbon source and reducing atmosphere in graphene CVD growth [20]. |

| Titanium Dioxide (TiO₂) & Carbon Powder | Solid precursors for CVD of titanium carbide (TiC) and titanium carbonitride (TiCN) coatings [19]. | Mixed in a 1:1 ratio and used with N₂ gas to deposit TiCN coatings [19]. |

| Nitrogen (N₂) Gas | Reactive gas for introducing nitrogen into coatings during CVD, forming nitride phases [19]. | Flow rate varied (50-150 sccm) to control properties of TiCN coatings [19]. |

| Poly-methyl methacrylate (PMMA) | Polymer support layer for the transfer of delicate 2D materials (e.g., graphene) from growth substrates to target substrates [20]. | Used as a support to transfer CVD graphene from Cu foil to SiO₂/Si [20]. |

| Ultra-Pure Inorganic Reagents | Foundational for reproducible synthesis and device performance; impurities can skew results and compromise performance in electronics and catalysis [22]. | Critical for cleaner electronics fabrication and reliable trace analysis [22]. |

Technique Implementation and Target Applications in Advanced Technology

In the fields of materials science and engineering, controlled deposition of thin films and coatings is a cornerstone for advancing technology in sectors ranging from electronics to biomedical devices. Two of the most pivotal techniques in this domain are electrodeposition (ED) and chemical vapor deposition (CVD), which differ fundamentally in their approach, operating conditions, and application landscapes. Electrodeposition operates through an electrochemical reaction in a liquid electrolyte, allowing for the controlled deposition of metal ions onto a conductive substrate. In contrast, chemical vapor deposition occurs in a gaseous environment within a vacuum chamber, where precursor gases undergo thermal decomposition to form solid coatings on substrates. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of these two methodologies, framing them within the broader context of inorganic crystals research for electrochemical and materials applications. By examining their respective experimental setups, performance characteristics, and optimization strategies, this analysis aims to equip researchers and development professionals with the data necessary to select the appropriate technique for their specific application requirements.

The comparative analysis presented herein is particularly relevant for applications requiring precise control over material properties, including wear resistance, corrosion protection, and tailored electrochemical activity. Recent advances in both techniques have been accelerated by the integration of autonomous experimentation and AI-driven optimization, which allows for more rapid exploration of parameter spaces and deeper scientific understanding of deposition phenomena. As the demand for advanced functional materials grows, understanding the capabilities and limitations of these deposition technologies becomes increasingly critical for innovation across scientific and industrial domains.

Fundamental Process Principles

Electrodeposition (ED), also referred to as electroplating, is an electrochemical process where metal ions in an electrolyte solution are reduced and deposited onto a conductive substrate through the application of an electric current. The process requires an anode (source of metal ions), a cathode (substrate to be coated), and an electrolyte solution containing dissolved metal salts. When current flows, oxidation occurs at the anode, releasing metal ions into the solution, while reduction at the cathode causes metal ions to deposit as a solid film. This process allows for good control over coating thickness and composition through manipulation of current density, temperature, and electrolyte chemistry. Electrodeposition is particularly valued for its ability to coat complex geometries with uniform layers and its compatibility with a wide range of metals and alloys.

Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) describes a family of processes where a substrate is exposed to volatile precursor gases that decompose and react on the substrate surface to produce a desired deposit. CVD processes occur in vacuum chambers where precise control of gas composition, flow rates, temperature, and pressure enables the growth of high-purity, high-performance solid materials. Unlike electrodeposition, CVD does not require electrically conductive substrates and can deposit a wider variety of materials, including ceramics, semiconductors, and diamond films. Hot-filament CVD (HFCVD), a common variant, uses heated filaments to crack precursor gases, facilitating diamond growth on various substrates. The complex interplay of transport phenomena and reaction kinetics in CVD allows for exquisite control over film microstructure and properties, albeit with typically higher equipment and operational costs than electrodeposition.

Direct Performance Comparison

Table 1: Direct comparison of key characteristics between electrodeposition and chemical vapor deposition

| Characteristic | Electrodeposition | Chemical Vapor Deposition |

|---|---|---|

| Process Mechanism | Electrochemical reduction in liquid electrolyte [23] [24] | Thermal decomposition in vapor phase [13] [25] |

| Typical Operating Environment | Aqueous electrolyte solution at ambient pressure | Vacuum chamber at controlled pressure and temperature |

| Typical Coating Materials | Metals (Ni, Cu, Zn, Cr) and alloys [24] [1] | Diamond, ceramics, semiconductors, specialized alloys [13] [25] |

| Adhesion Strength | Moderate metallic bonding [23] [24] | Strong molecular bonding [23] |

| Wear Resistance | Moderate [23] [24] | Excellent [23] |

| Corrosion Resistance | Good (depends on metal type) [23] [24] | Superior [23] |

| Environmental Impact | Chemical waste requiring disposal [23] [24] | Environmentally friendly, no toxic byproducts [23] |

| Coating Uniformity on Complex Shapes | Excellent throwing power | Line-of-sight limitations, may require rotation |

| Typical Deposition Rate | 0.1-10 μm/min | 0.001-0.1 μm/min |

| Relative Cost | Low to moderate [24] | High [23] [24] |

| Heat Resistance | Limited; may degrade under heat [23] | Excellent; maintains integrity at high temperatures [23] |

Advanced Process Variations

Both electrodeposition and CVD have evolved beyond their basic implementations to include specialized techniques that expand their capabilities. Advanced electrodeposition methods include pulse electrodeposition and composite co-deposition. Pulse electrodeposition uses modulated current to achieve better grain structure control and more uniform deposits, particularly in high-aspect-ratio features. Composite co-deposition, as demonstrated in Ni-Al₂O₃ systems, suspends ceramic nanoparticles in the electrolyte that become incorporated into the growing metal matrix, significantly enhancing hardness and wear resistance [1]. These composite coatings can achieve microhardness improvements exceeding 160% compared to pure metal deposits [1].

CVD technology similarly encompasses numerous specialized approaches. Hot-filament CVD (HFCVD) is particularly important for diamond film synthesis, using strategically positioned filaments to crack precursor gases at temperatures exceeding 2000°C while maintaining substrates at lower temperatures [25]. Other variants include plasma-enhanced CVD (PECVD) that lowers deposition temperatures enabling coating of temperature-sensitive materials, and atomic layer deposition (ALD) which provides exceptional thickness control at the atomic scale through self-limiting surface reactions. The emergence of autonomous experimentation (AE) systems for CVD represents a particularly significant advancement, combining artificial intelligence with robotics to design, execute, and analyze deposition experiments in rapid, iterative cycles [13]. These self-driving labs can optimize synthesis parameters and test scientific hypotheses more efficiently than human researchers alone, accelerating materials discovery and process optimization.

Experimental Setups and Methodologies

Standard Electrodeposition Setup for Composite Coatings

The electrodeposition of nickel-alumina (Ni-Al₂O₃) composite coatings represents a well-established methodology for enhancing surface properties of components. The following protocol outlines a standardized approach optimized using Taguchi methods [1]:

Apparatus and Reagents:

- Electrolyte Cell: 200 mL Pyrex glass beaker

- Power Supply: Direct current (DC) source with adjustable current density (2-5 A·dm⁻²)

- Anode: High-purity nickel plate (99.8%) as soluble anode

- Cathode/Substrate: Medium carbon steel discs (20 mm diameter × 4 mm thickness)

- Electrolyte Composition: Watts bath containing nickel sulfate (240-300 g·L⁻¹), nickel chloride (45-90 g·L⁻¹), boric acid (30-45 g·L⁻¹)

- Reinforcement Phase: Aluminum oxide (Al₂O₃) powder (10-25 g·L⁻¹) with particle size typically 0.1-1.0 μm

- Agitation System: Magnetic stirrer with controlled rotation speed (200-350 rpm)

Substrate Preparation:

- Section substrates to required dimensions using a precision cutting instrument.

- Mount specimens in phenolic resin using a hot mounting press to define a consistent working surface area of 3.14 cm².

- Polish mounted substrates to a mirror finish using progressively finer abrasives.

- Clean and degrease by immersion in acetone for 1 minute followed by rinsing with distilled water.

- Etch in hydrochloric acid solution (50 g·L⁻¹) at 40°C for 1 minute to remove surface oxides.

- Rinse again with distilled water and dry thoroughly before deposition.

Deposition Procedure:

- Prepare electrolyte by dissolving Watts bath components in distilled water.

- Add Al₂O₃ powder to the electrolyte and stir continuously at 600 rpm for 16 hours to ensure homogeneous suspension.

- Position anode and cathode parallel to each other with an inter-electrode distance of 2 cm.

- Immerse electrodes in the electrolyte maintained at constant temperature (typically 45-55°C).

- Apply DC current at predetermined density (2-5 A·dm⁻²) for specified duration (15-60 minutes).

- Maintain constant agitation (200-350 rpm) throughout deposition to ensure uniform particle distribution.

- Remove coated substrate, rinse with distilled water, and dry for characterization.

Table 2: Optimization parameters for Ni-Al₂O₃ composite electrodeposition [1]

| Parameter | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | Optimal Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current Density (A·dm⁻²) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| Al₂O₃ Concentration (g·L⁻¹) | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 20 |

| Deposition Time (min) | 15 | 30 | 45 | 60 | 60 |

| Agitation Rate (rpm) | 200 | 250 | 300 | 350 | 300 |

Hot-Filament CVD Setup for Diamond Electrodes

The deposition of boron-doped diamond (BDD) electrodes via hot-filament CVD represents a sophisticated application of vapor deposition for advanced electrochemical applications. The following protocol details the fabrication of ceramic-based BDD electrodes [25]:

Apparatus and Reagents:

- Reactor Chamber: Custom-built HFCVD system with vacuum capability

- Filament Material: Tungium or rhenium wires arranged in parallel arrays

- Substrate: Kaolinite-cordierite ceramic (5 cm × 5 cm × 0.25 cm) with pre-drilled holes for electrical contacting

- Precursor Gases: Hydrogen (1000 mL·min⁻¹), methane (12 mL·min⁻¹), trimethylborate (0.15 mL·min⁻¹) as boron source

- Pressure Control System: Capable of maintaining 3.3 mbar operating pressure

- Temperature Monitoring: Optical pyrometry or thermocouple for substrate temperature measurement

Substrate Preparation:

- Subject ceramic substrates to particle blasting (SiC-F150, 4 bar) to enhance adhesion.

- Clean ultrasonically in ethanol to remove particulate contaminants.

- Seed with nano-diamond particles (1:500 in ethanol) using ultrasonic treatment to create nucleation sites.

- Dry seeded substrates in clean environment before loading into CVD reactor.

Deposition Procedure:

- Load prepared substrates between parallel filament arrays (30 mm spacing) in CVD chamber.

- Evacuate chamber to base pressure (typically <10⁻² mbar).

- Introduce hydrogen gas and activate filaments to operating temperature (approximately 2000°C).

- Heat substrates to deposition temperature of 850°C (±10°C) using filament radiation.

- Introduce methane and trimethylborate precursors into gas stream.

- Maintain deposition conditions for 42 hours to achieve approximately 7 μm coating thickness.

- Terminate gas flows and cool system under hydrogen atmosphere.

- Remove coated substrates for post-processing.

Post-Deposition Processing:

- Perform laser structuring using infrared laser (λ = 1064 nm, 100 W, 10 kHz) to create interdigitated electrode patterns.

- Set laser parameters to 60 mm/s scan speed with total structural path of 233.8 cm per sample side.

- Electrochemically anodize laser-structured regions at 10 V in distilled water for 2 minutes to remove sp² carbon residues.

- Characterize final electrode structure using SEM, Raman spectroscopy, and electrochemical testing.

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Comparative workflow for electrodeposition and CVD processes

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for deposition experiments

| Category | Specific Material/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrodeposition Components | Nickel Sulfate (NiSO₄·6H₂O) | Primary source of nickel ions in Watts bath | Ni and Ni-Al₂O₃ coatings [1] |

| Nickel Chloride (NiCl₂·6H₂O) | Increases conductivity, prevents anode passivation | Ni and Ni-Al₂O₃ coatings [1] | |

| Boric Acid (H₃BO₃) | pH buffer, improves deposit quality | Watts bath formulations [1] | |

| Aluminum Oxide (Al₂O₃) Powder | Reinforcement phase for composite coatings | Wear-resistant Ni-Al₂O₃ composites [1] | |

| CVD Precursors | Hydrogen (H₂) | Carrier gas, removes non-diamond carbon | Diamond CVD [25] |

| Methane (CH₄) | Carbon source for diamond growth | Boron-doped diamond electrodes [25] | |

| Trimethylborate (B(OCH₃)₃) | Boron doping source for p-type semiconductor | Conductive diamond electrodes [25] | |

| Substrate Materials | Medium Carbon Steel | Conductive substrate for electrodeposition | Ni-Al₂O₃ composite coatings [1] |

| Kaolinite-Cordierite Ceramic | Thermally stable, electrically insulating substrate | Ceramic-based BDD electrodes [25] | |

| Silicon Wafers | Semiconductor substrate with well-defined surface | BDD on silicon for comparison [25] | |

| Preparation Materials | Nano-diamond Powder (50-100 nm) | Seeding material for diamond nucleation | Enhanced diamond growth on non-traditional substrates [25] |

| Silicon Carbide (SiC) Abrasive | Surface roughening for improved adhesion | Substrate preparation for ceramic BDD [25] | |

| Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) | Surface etching/activation | Substrate cleaning and oxide removal [1] |

Performance Data and Optimization Approaches

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 4: Experimentally measured performance outcomes for deposition processes

| Performance Metric | Electrodeposition Results | CVD Results | Testing Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coating Thickness | 5-50 μm (15-60 min deposition) [1] | ~7 μm (42 h deposition) [25] | Cross-sectional SEM, Laser microscopy |

| Microhardness | 164% increase for Ni-Al₂O₃ vs pure Ni [1] | >1.91 GPa for BDD [25] | Vickers micro-indentation |

| Al₂O₃ Incorporation | 400% increase at optimal parameters [1] | Not applicable | EDS elemental analysis |

| Crystallite Size | 20-60 nm (controlled by parameters) [1] | Microcrystalline facets >1 μm [25] | XRD Scherrer calculation, SEM |

| Energy Consumption | Lower operational energy | Higher (vacuum, high temperature) | 14-46% less for iDDE vs standard BDD [25] |

| Coating Adhesion | Moderate (metallic bonding) [24] | Excellent (molecular bonding) [23] | Tape test, scratch testing |

| Crystal Orientation | (220) preferential at high H₃BO₃ [1] | (111) orientation ratio up to 96% [26] | XRD texture analysis |

Process Optimization Methodologies

Both electrodeposition and CVD benefit significantly from systematic optimization approaches. The Taguchi method has been successfully applied to electrodeposition processes to identify critical parameters and their optimal ranges. Using an L₁₆ orthogonal array design, researchers can efficiently evaluate multiple factors simultaneously while minimizing experimental runs. For Ni-Al₂O₃ composite coatings, this approach has revealed that current density and deposition time exert the most significant influence on microhardness and particle incorporation, followed by alumina concentration and agitation rate [1]. The application of Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) further quantifies the relative contribution of each parameter to the observed results, enabling data-driven process optimization.

For CVD processes, autonomous experimentation (AE) systems represent the cutting edge in optimization methodology. These self-driving labs combine robotics, in situ characterization, and artificial intelligence to iteratively design and execute experiments without human intervention. The ARES CVD system developed by the Air Force Research Laboratory exemplifies this approach, using real-time Raman spectroscopy to characterize carbon nanotube growth and AI planners to select subsequent experimental conditions [13]. This closed-loop optimization can explore complex parameter spaces—including temperature, gas composition, and flow rates—more efficiently than traditional approaches, leading to both process optimization and fundamental scientific insights. For instance, AE campaigns have confirmed that CNT catalyst activity peaks when the metal catalyst is in equilibrium with its oxide, demonstrating how optimization can yield mechanistic understanding [13].

Diagram 2: Optimization methodologies for deposition processes

Application-Specific Implementation Guidance

Technology Selection Framework

Choosing between electrodeposition and chemical vapor deposition requires careful consideration of application requirements, material constraints, and economic factors. The following decision framework provides guidance for technology selection:

Select electrodeposition when:

- Applications require moderate wear and corrosion protection rather than extreme performance [23] [24]

- Cost sensitivity is a primary concern, particularly for high-volume production [24]

- Components have complex geometries requiring uniform coverage in recessed areas [24]

- Electrical conductivity is the primary functional requirement [24]

- Substrate materials are thermally sensitive and cannot withstand high temperatures [23]

- Rapid prototyping or benchtop-scale development is needed with limited capital investment

Select chemical vapor deposition when:

- Applications demand exceptional hardness, wear resistance, or durability [23]

- High-temperature performance is required for the coated component [23]

- Superior adhesion is critical for component lifetime and reliability [23]

- Complex material compositions (ceramics, diamonds, specialized semiconductors) are needed [13] [25]

- Environmental considerations favor processes without hazardous chemical waste [23]

- Applications require precise control over crystallinity and microstructure at the nanoscale

Emerging Applications and Future Directions

Recent advances in both electrodeposition and CVD have opened new application frontiers that leverage their respective capabilities. In electrochemical advanced oxidation processes (EAOPs) for water treatment, boron-doped diamond electrodes fabricated via CVD offer exceptional performance for degrading persistent organic pollutants [25]. The development of interdigitated double diamond electrodes (iDDE) with reduced interelectrode spacing (<50 μm) demonstrates how CVD-fabricated electrodes can achieve 14-46% energy savings compared to standard BDD technology, addressing both performance and sustainability requirements [25].

For electrodeposition, the integration of nanoparticle reinforcements and optimized process parameters has enabled the fabrication of composite coatings with dramatically enhanced properties. The 400% increase in alumina incorporation and 164% improvement in microhardness demonstrated in optimized Ni-Al₂O₃ systems illustrates the potential for electrodeposition to meet demanding mechanical requirements [1]. The continued development of pulse and pulse-reverse electrodeposition techniques further expands the capability to control grain structure, residual stress, and composition distribution in electrodeposited coatings.

The convergence of both technologies with digitalization and automation represents perhaps the most significant future direction. Autonomous experimentation systems for CVD are already demonstrating the ability to optimize complex multi-parameter processes and test scientific hypotheses with minimal human intervention [13]. Similar approaches are being applied to electrodeposition, where machine learning algorithms can identify optimal parameter combinations from limited experimental data. These advancements suggest a future where deposition processes are increasingly optimized through computational and robotic approaches, accelerating both fundamental understanding and technology deployment across research and industrial sectors.

The relentless pursuit of miniaturization and enhanced performance in semiconductor devices places immense importance on advanced fabrication techniques. Thin-film deposition processes are fundamental to forming interconnects, diffusion barriers, and transistor gates, directly influencing device speed, power efficiency, and reliability. This guide provides an objective comparison between two pivotal deposition methods: electrochemical deposition (ECD) and chemical vapor deposition (CVD), within the context of inorganic crystal growth for microelectronics. Framed for researchers and scientists, this analysis presents experimental data, detailed protocols, and key reagents to inform material selection and process development for next-generation devices.

Electrochemical deposition (ECD) is a well-established technique where metal ions dissolved in an electrolyte solution are reduced and deposited onto a conductive substrate through an applied electric potential. It is widely utilized for its cost-effectiveness and high deposition rates, particularly in the formation of copper interconnects. [27]

Chemical vapor deposition (CVD) involves the dissociation of vapor-phase precursor chemicals on a heated substrate surface, resulting in the formation of a solid thin film. Variants such as Plasma-Enhanced CVD (PECVD) and Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD) offer enhanced control, enabling deposition at lower temperatures and with superior conformality for complex three-dimensional architectures. [27] [2]

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of ECD and CVD for Semiconductor Fabrication

| Feature | Electrochemical Deposition (ECD) | Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Electrochemical reduction of metal ions from a solution. [27] | Chemical reaction of vapor-phase precursors on a heated substrate. [27] |

| Typical Materials | Copper (Cu), Nickel (Ni), Gold (Au) for interconnects. [27] | Tungsten (W), Silicon Dioxide (SiO₂), Silicon Nitride (Si₃N₄), High-k dielectrics (e.g., HfO₂). [27] [28] |

| Deposition Rate | High. [27] | Moderate to Low; ALD is very low but highly controlled. [27] |

| Film Uniformity & Conformality | Can suffer from non-uniformity and poor step coverage in high-aspect-ratio features. [27] | Excellent uniformity and conformality, especially in ALD and PECVD. [27] [2] |

| Typical Process Temperature | Low (Near room temperature to <100°C). [27] | High (300-1000°C); PECVD enables lower temperatures (150-400°C). [27] [2] |

| Precursor Requirements | Metal salts in aqueous or organic electrolytes. [27] | High-purity, volatile gases or vapors (e.g., SiH₄, WF₆). [27] |

| Capital & Operational Cost | Relatively low cost and operational simplicity. [27] | High cost due to complex reactor systems and expensive precursors. [27] |

| Key Limitations | Unstable deposition quality, inadequate film uniformity, and limited precision control at micro/nanoscale. [27] | High thermal budget for conventional CVD; precursor chemistry limitations. [27] |

| Primary Applications in ICs | On-chip copper interconnects, through-silicon vias (TSVs), packaging. [27] | Gate electrodes (e.g., W), gate dielectrics, diffusion barriers (e.g., SiN), pre-metal dielectrics. [27] [28] |

Experimental Performance Data

Interconnect Fabrication: ECD vs. CVD Copper

The formation of copper interconnects is a critical application where ECD and CVD are directly compared. Experimental data from the literature highlights a performance trade-off.

Table 2: Experimental Comparison of Copper Interconnect Deposition

| Parameter | Electrochemical Deposition (ECD) of Cu | CVD of Cu |

|---|---|---|

| Resistivity (μΩ·cm) | ~1.98 (bulk, after annealing) [27] | ~2.5 - 3.5 (as-deposited, highly dependent on impurities and morphology) [27] |

| Deposition Rate | ~500 nm/min (excellent for high-throughput manufacturing) [27] | ~50 nm/min (slower, can be a bottleneck) [27] |

| Step Coverage in High-Aspect-Ratio Trenches | Moderate to poor; requires sophisticated additives and pulse plating for void-free filling. [27] | Good inherent conformality; can achieve uniform coatings without voids. [27] |

| Adhesion to Diffusion Barrier (e.g., TaN) | Excellent when surface is properly seeded and pre-treated. [27] | Good, but highly dependent on the surface chemistry of the barrier layer. [27] |

| Process Complexity | Requires management of additive chemistry (accelerators, suppressors, levelers) in the bath. [27] | Requires precise control of precursor temperature, vapor pressure, and decomposition kinetics. [27] |

Summary: ECD is the dominant industrial process for copper interconnects due to its high deposition rate and lower cost, achieving low resistivity post-annealing. However, it requires complex chemical additives to achieve void-free "superfilling" of features. CVD copper offers superior conformality without additives but suffers from higher resistivity and lower deposition rates, limiting its widespread adoption for this specific application. [27]

Barrier and Gate Layer Fabrication: The CVD and ALD Advantage

For diffusion barriers and gate stacks, CVD and its derivative, ALD, are unambiguously superior due to their atomic-level control.

Diffusion Barriers: As device features shrink, preventing copper diffusion into the silicon substrate is critical. While ECD cannot deposit an effective barrier material, CVD and ALD excel at depositing conformal, pinhole-free barrier layers like silicon nitride (SiN) or tantalum nitride (TaN). Experimental studies show that PECVD SiN barriers as thin as 20nm can effectively block copper diffusion at backend-of-line (BEOL) processing temperatures. [27] [28]

Gate Stacks: The fabrication of transistor gates demands ultra-thin, uniform, and high-quality dielectric materials. ECD has no role in this domain. In contrast, ALD, a variant of CVD, is the industry standard for depositing high-k dielectric materials (e.g., HfO₂) in gate-all-around (GAA) transistors. ALD provides the atomic-scale fidelity required for sub-5nm technology nodes, enabling equivalent oxide thicknesses of less than 1nm with low leakage currents. [28] Research on all-2D material field-effect transistors (FETs) using CVD-grown molybdenum disulfide (MoS₂) with graphene contacts has demonstrated the viability of CVD for next-generation device architectures, achieving room-temperature mobilities of ~14.5 cm²/V·s. [29]

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Electrochemical Deposition of Copper Interconnects

This protocol outlines the standard process for void-free copper filling of high-aspect-ratio trenches on a silicon wafer with a PVD-deposited Ta/TaN barrier and a Cu seed layer.

- Substrate Preparation: A 300mm p-type silicon wafer with patterned oxide trenches and a physical vapor deposition (PVD)-deposited Ta/TaN barrier layer (10nm) and a PVD Cu seed layer (50nm) is used. The wafer is cleaned in a dilute sulfuric acid solution (H₂SO₄:H₂O = 1:10 v/v) for 60 seconds to remove native oxides from the Cu seed layer, then rinsed with deionized water.

- Electrolyte Preparation: The deposition bath is prepared with 0.7M CuSO₄, 1.0M H₂SO₄, 50 ppm Cl⁻ (from HCl), and proprietary organic additives including a suppressor (polyethylene glycol), an accelerator (bis-(sodium-sulfopropyl)-disulfide), and a leveler (janus green b).

- Deposition Process: The wafer is mounted on a cathode and immersed in the electrolyte at 25°C. Deposition is performed using a periodic pulse reverse plating waveform:

- Forward Pulse: +10 mA/cm² for 50 ms (deposition).

- Reverse Pulse: -30 mA/cm² for 5 ms (dissolution).

- This cycle promotes bottom-up superfill by differentially affecting deposition rates at the trench bottom versus the sidewalls.

- Post-Deposition Treatment: The wafer is rinsed with deionized water and subjected to an annealing step at 150°C for 30 minutes in a N₂ atmosphere to recrystallize the copper, reduce grain boundary scattering, and lower resistivity. [27]

Protocol for CVD of a Tungsten Gate Electrode

This protocol describes a low-pressure CVD (LPCVD) process for depositing a tungsten (W) gate electrode via hydrogen reduction of tungsten hexafluoride.

- Substrate Preparation: A silicon wafer with an ALD-deposited high-k dielectric layer (e.g., HfO₂) is loaded into the LPCVD reactor. The chamber is evacuated to a base pressure of <10⁻⁶ Torr.

- Pre-Deposition Step: To ensure good adhesion and nucleation, a thin (~5nm) "nucleation layer" of tungsten is often deposited using a silane (SiH₄) reduction process: 2WF₆ + 3SiH₄ → 2W + 3SiF₄ + 6H₂. This step is performed at 300°C and 1 Torr.

- Bulk Deposition Process: The temperature is raised to 450°C. The main deposition is carried out using the hydrogen reduction reaction: WF₆ + 3H₂ → W + 6HF. Process conditions are:

- WF₆ flow rate: 50 sccm

- H₂ flow rate: 500 sccm

- Chamber Pressure: 2 Torr

- Deposition Time: 10 minutes (to achieve a target thickness of ~50nm)

- Post-Deposition Treatment: The chamber is purged with argon gas. The wafer is unloaded after cooling to below 100°C. Subsequent chemical-mechanical polishing (CMP) is used to planarize the tungsten film and define the final gate structure. [27] [28]

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the key decision-making workflow for selecting between ECD and CVD based on the target application in semiconductor fabrication.