Data-Driven Material Synthesis: Accelerating Discovery from AI Prediction to Lab Validation

This article provides a comprehensive overview of data-driven methodologies revolutionizing the discovery and synthesis of novel materials.

Data-Driven Material Synthesis: Accelerating Discovery from AI Prediction to Lab Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of data-driven methodologies revolutionizing the discovery and synthesis of novel materials. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational shift from traditional, time-intensive experimentation to approaches powered by machine learning (ML) and materials informatics. The scope spans from core concepts and computational frameworks like the Materials Project to practical applications in predicting mechanical and functional properties. It critically addresses ubiquitous challenges such as data quality and model reliability, offering optimization strategies. Finally, the article presents comparative analyses of different ML techniques and real-world validation case studies, synthesizing key takeaways to outline a future where accelerated material synthesis directly impacts the development of advanced biomedical technologies and therapies.

The New Paradigm: Foundations of Data-Driven Materials Science

The field of materials science is undergoing a fundamental transformation, moving from reliance on empirical observation and intuition-driven discovery to a precision discipline governed by informatics and data-driven methodologies. This paradigm shift represents a fundamental reorientation in how researchers understand, design, and synthesize novel materials. Where traditional approaches depended heavily on trial-and-error experimentation and theoretical calculations, the emerging informatics paradigm leverages machine learning, high-throughput computation, and data-driven design to navigate the vast complexity of material compositions and properties with unprecedented speed and accuracy [1]. This transition is not merely incremental improvement but constitutes a revolutionary change in the scientific research paradigm itself, enabling the acceleration of materials development cycles from decades to mere months [2].

The driving force behind this shift is the convergence of several technological advancements: increased availability of materials data, sophisticated machine learning algorithms capable of parsing complex material representations, and computational resources powerful enough to simulate material properties at quantum mechanical levels. As noted by Kristin Persson of the Materials Project, this data-rich environment "is inspiring the development of machine learning algorithms aimed at predicting material properties, characteristics, and synthesizability" [3]. The implications extend across the entire materials innovation pipeline, from initial discovery to synthesis optimization and industrial application, fundamentally reshaping research methodologies in both academic and industrial settings.

Key Drivers of the Informatics-Led Transformation

The Data Foundation: High-Throughput Computation and Experiments

The infrastructure supporting this paradigm shift relies on systematic data generation through both computational and experimental means. Initiatives like the Materials Project have created foundational databases by using "supercomputing and an industry-standard software infrastructure together with state-of-the-art quantum mechanical theory to compute the properties of all known inorganic materials and beyond" [3]. This database, covering over 200,000 materials and millions of properties, serves as a cornerstone for data-driven materials research, delivering millions of data records daily to a global community of more than 600,000 registered users [3].

Complementing these computational efforts, high-throughput experimental techniques enable rapid empirical validation and data generation. Automated materials synthesis laboratories, such as the A-Lab at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, integrate AI with robotic experimentation to accelerate the discovery cycle [1]. This synergy between computation and experiment creates a virtuous cycle where computational predictions guide experimental efforts, while experimental results refine and validate computational models. The design of experiments (DOE) methodology provides a statistical framework for optimizing this process, introducing conditions that directly affect variation and establishing validity through principles of randomization, replication, and blocking [4].

Advanced Machine Learning Methodologies

Machine learning algorithms represent the analytical engine of the informatics paradigm, with Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) emerging as particularly powerful tools for materials science applications. GNNs operate directly on graph-structured representations of molecules and materials, providing "full access to all relevant information required to characterize materials" at the atomic level [5]. This capability is significant because it allows models to learn internal material representations based on natural input structures rather than relying on hand-crafted feature representations.

The Message Passing Neural Network (MPNN) framework has become particularly influential for materials applications. In this architecture, "node information is propagated in form of messages through edges to neighboring nodes," allowing the model to capture both local atomic environments and longer-range interactions within material structures [5]. This approach has demonstrated superior performance in predicting molecular properties compared to conventional machine learning methods, enabling applications ranging from drug design to material screening [5].

Table 1: Machine Learning Approaches in Materials Informatics

| Method Category | Key Examples | Primary Applications | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Networks | Message Passing Neural Networks, Spectral GNNs | Molecular property prediction, Material screening | Direct structural representation, End-to-end learning |

| Generative Models | MatterGen, GNoME | Inverse materials design, Novel structure prediction | Exploration of uncharted chemical space |

| Multi-task Learning | Multi-headed neural networks | Predicting multiple reactivity metrics simultaneously | Efficient knowledge transfer, Reduced data requirements |

Quantum and Computational Advances

Underpinning the data-driven revolution are significant advances in computational methods, particularly in quantum mechanical modeling. Large-scale initiatives such as the Materials Genome Initiative, National Quantum Initiative, and CHIPS for America Act represent coordinated efforts to investigate quantum materials and accelerate their development for practical applications [6]. These initiatives recognize that while "all materials are inherently quantum in nature," leveraging quantum phenomena for applications requires manifestation at classical scales [6].

Computational methods now enable high-fidelity prediction of material properties across multiple scales, from quantum mechanical calculations of electronic structure to mesoscale modeling of polycrystalline materials. The integration of these computational approaches with machine learning creates powerful hybrid models, such as those combining density functional theory (DFT) with machine-learned force fields for defect simulations [6]. These multi-scale, multi-fidelity modeling approaches are essential for bridging the gap between quantum phenomena and macroscopic material properties.

Exemplary Case Studies in Informatics-Driven Discovery

Atomic-Level Mapping of Ceramic Grain Boundaries

A landmark achievement exemplifying the new paradigm is Professor Martin Harmer's 2025 work mapping the atomic structure of ceramic grain boundaries with unprecedented resolution. This research, recognized by the Falling Walls Foundation as one of the year's top ten scientific breakthroughs, represents a fundamental advance in understanding these critical interfaces where crystalline grains meet in polycrystalline materials [7]. Historically viewed as defect-prone zones that inevitably led to material failure, grain boundaries can now be precisely engineered using Harmer's approach, which combines aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscopy with sophisticated computational modeling [7].

The methodology enabled three-dimensional atomic mapping of these boundaries, generating what Harmer describes as a "roadmap for designing stronger and more durable ceramic products" [7]. The practical implications are substantial across multiple industries: in aerospace, enabling turbine blades that withstand significantly higher operating temperatures; in electronics, paving the way for more efficient semiconductors. This work exemplifies how deep atomic-level understanding, facilitated by advanced characterization and modeling, enables precise tuning of materials at the most fundamental level [7].

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of Informatics-Driven Materials Development

| Application Domain | Traditional Timeline | Informatics-Accelerated Timeline | Key Enabling Technologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ceramics Development | 5-10 years | 1-2 years | Atomic-level mapping, Computational modeling |

| Cementitious Precursors | 3-5 years | Rapid screening | LLM literature mining, Multi-task neural networks |

| Energy Materials | 10-20 years | 2-5 years | High-throughput computation, Automated experimentation |

Data-Driven Discovery of Cementitious Materials

In a compelling application of informatics to industrial-scale sustainability challenges, researchers have developed a machine learning framework for identifying novel cementitious materials. This approach addresses the critical environmental impact of cement production, which "accounts for >6% of global greenhouse gas emissions" [8]. The methodology combines large language models (LLMs) for data extraction with multi-headed neural networks for property prediction, demonstrating the power of integrating diverse AI methodologies.

The research team fine-tuned LLMs to extract chemical compositions and material types from 88,000 academic papers, identifying 14,000 previously used cement and concrete materials [8]. A subsequent machine learning model predicted three key reactivity metrics—heat release, Ca(OH)₂ consumption, and bound water—based on chemical composition, particle size, specific gravity, and amorphous/crystalline phase content [8]. This integrated approach enabled rapid screening of over one million rock samples, identifying numerous potential clinker substitutes that could reduce global greenhouse gas emissions by 3%—equivalent to removing 260 million vehicles from U.S. roads [8].

Experimental Workflow for Informatics-Driven Materials Discovery

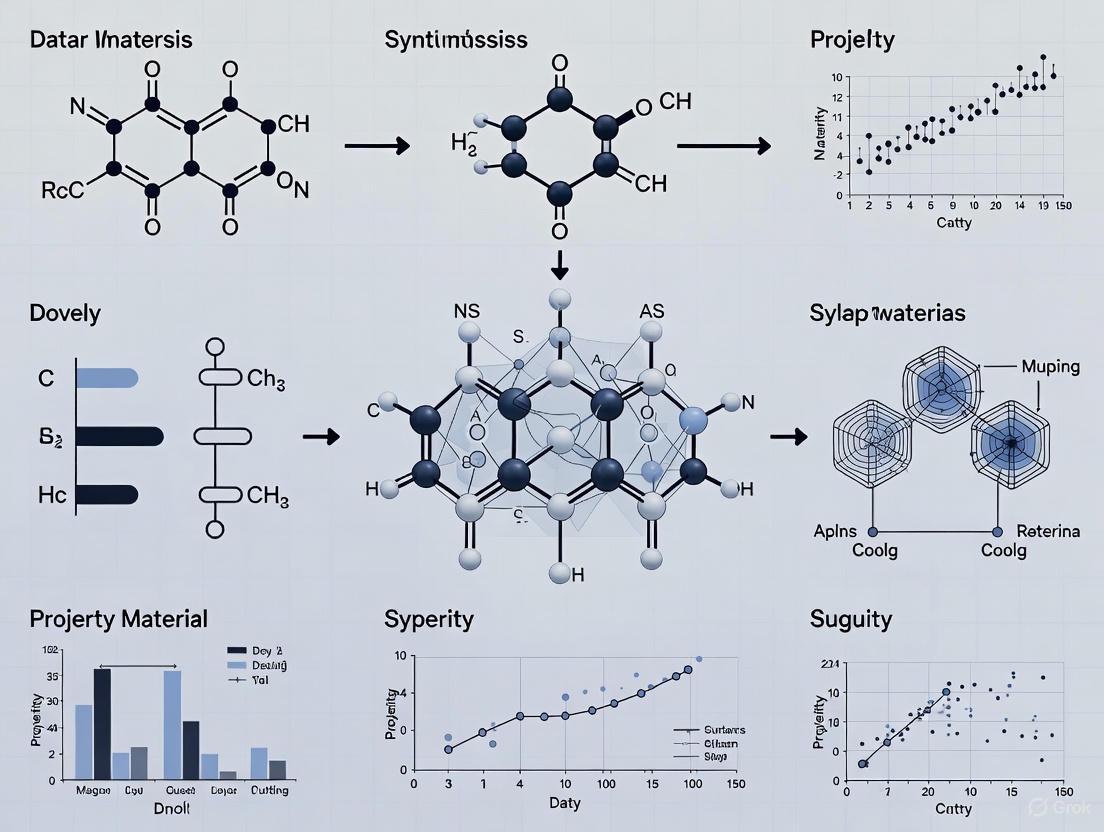

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational-experimental workflow characteristic of modern materials informatics, synthesizing methodologies from the case studies above:

Diagram 1: Informatics-driven materials discovery workflow integrating computational and experimental approaches.

Essential Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

The Scientist's Toolkit: Core Research Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools and Methodologies for Materials Informatics

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function & Application | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characterization Instruments | Aberration-corrected STEM | Atomic-scale mapping of material structure | Grain boundary analysis in ceramics [7] |

| Computational Resources | Materials Project Database | Repository of computed material properties | Screening candidate materials for specific applications [3] |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Learning molecular representations from structure | Property prediction for novel compounds [5] |

| Experimental Validation Systems | R3 Test Apparatus | Standardized assessment of chemical reactivity | Evaluating cementitious precursors [8] |

| High-Throughput Automation | Robotic synthesis systems | Automated material preparation and testing | Accelerated synthesis optimization [1] |

Protocol: Atomic-Level Mapping of Grain Boundaries

The groundbreaking work on ceramic grain boundaries followed a meticulous experimental and computational protocol:

Sample Preparation: Fabricate polycrystalline ceramic specimens with controlled composition and processing history to ensure representative grain boundary structures.

Atomic-Resolution Imaging: Employ aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) to resolve atomic positions at grain boundaries. This technique corrects for lens imperfections that historically limited resolution [7].

Three-Dimensional Reconstruction: Acquire multiple images from different orientations to reconstruct the three-dimensional atomic arrangement using tomographic principles.

Computational Modeling Integration: Develop atomic-scale models that simulate the observed structures, incorporating quantum mechanical calculations to understand interface energetics and stability [7].

Property Correlation: Correlate specific atomic configurations with macroscopic material properties through controlled experiments, establishing structure-property relationships that inform design principles.

This protocol successfully demonstrated that grain boundaries, traditionally viewed as material weaknesses, could be engineered to enhance material performance—a fundamental shift in understanding enabled by advanced characterization and modeling [7].

Protocol: Machine Learning-Assisted Discovery of Cementitious Materials

The data-driven approach to identifying cement alternatives followed this systematic protocol:

Literature Mining Phase:

- Collect ~5.7 million journal publications through a streamlined extraction pipeline

- Apply fine-tuned large language models (LLMs) to extract chemical compositions from XML tables

- Classify materials into 19 predefined types using hierarchical classification [8]

Model Training Phase:

- Curate a training set of 318 materials with experimentally measured reactivity

- Train a multi-headed neural network to predict three reactivity metrics: heat release, Ca(OH)₂ consumption, and bound water

- Input features include chemical composition, median particle size, specific gravity, and amorphous/crystalline phase content [8]

Screening and Validation Phase:

- Apply the trained model to screen over one million rock samples from geological databases

- Identify promising candidates with heat release >200 J/g

- Validate predictions through targeted experimental testing [8]

This protocol demonstrates how machine learning can dramatically accelerate the initial screening process for material discovery, reducing the experimental burden by orders of magnitude while systematically exploring a broader chemical space.

Implementation Challenges and Future Trajectories

Critical Implementation Barriers

Despite the considerable promise of informatics-driven materials science, significant challenges remain in widespread implementation:

Data Quality and Availability: The success of AI models depends fundamentally on "the quality and quantity of available data" [1]. Issues such as data inconsistencies, proprietary restrictions on formulations, and difficulties in replicating results across different laboratories hinder scalability [1].

Integration with Physical Principles: For models to be truly predictive and generalizable, they must incorporate fundamental scientific principles. As noted in the NIST Quantum Matters workshop, "truly accelerating materials innovation also requires rapid synthesis, testing and feedback, seamlessly coupled to existing data-driven predictions and computations" [6].

Manufacturing Scalability: Even with successful discovery, scaling production to industrial levels presents substantial hurdles. Market analysts point to "significant hurdles related to scaling production to a level that demands atomic precision," requiring advanced manufacturing capabilities and supply chain adaptations [7].

Emerging Frontiers and Future Development

The trajectory of materials informatics points toward several exciting frontiers:

Autonomous Discovery Systems: The integration of AI with robotic laboratories is advancing toward fully autonomous materials discovery systems. These systems would "not only identify new material candidates but also optimize synthesis pathways, predict physical properties, and even design scalable manufacturing processes" [1].

Quantum-Accurate Machine Learning: Developing machine learning models that achieve quantum accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency remains an active frontier. Methods that combine the accuracy of high-fidelity quantum mechanical calculations with the speed of machine learning represent a key direction for future research [6].

Multi-Scale Modeling Integration: Bridging length and time scales from quantum phenomena to macroscopic material behavior requires sophisticated multi-scale modeling approaches. Workshops such as QMMS focus on "streamlining this effort" through improved synergy between experimental and computational approaches [6].

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected challenges and solution frameworks characterizing the future of materials informatics:

Diagram 2: Implementation framework addressing key challenges in materials informatics.

The transformation of materials science from intuition to informatics represents more than a methodological shift—it constitutes a fundamental change in how humanity understands and engineers the material world. This paradigm shift enables researchers to navigate the complex landscape of material composition, structure, and properties with unprecedented precision and efficiency. The convergence of advanced characterization techniques, computational modeling, and machine learning has created a powerful new framework for materials discovery and design.

As the field advances, the integration of data-driven approaches with fundamental physical principles will be crucial for developing truly predictive capabilities. The challenges of data quality, model interpretability, and manufacturing scalability remain substantial, but the progress to date demonstrates the immense potential of informatics-driven materials science. This paradigm promises not only to accelerate materials development but to enable entirely new classes of materials with tailored properties and functionalities, ultimately driving innovation across industries from energy and electronics to medicine and construction. The era of informatics-led materials science has arrived, and its impact is only beginning to be realized.

Process-Structure-Property (PSP) Linkages and Material Fingerprints

The Process-Structure-Property (PSP) linkage is a foundational concept in materials science, providing a framework for understanding how a material's processing history influences its internal structure, and how this structure in turn determines its macroscopic properties and performance [9]. For decades, materials development has been hindered by the significant time and cost associated with traditional trial-and-error methods, where the average timeline for a new material to reach commercial maturity can span 20 years or more [9]. The emergence of data-driven materials informatics represents a paradigm shift, augmenting traditional physical knowledge with advanced computational techniques to dramatically accelerate the discovery and development of novel materials [9].

Central to this data-driven approach is the concept of a material fingerprint (sometimes termed a "descriptor")—a quantitative, numerical representation of a material's critical characteristics that enables machine learning algorithms to establish predictive mappings between structure and properties [10]. When combined with PSP linkages, these fingerprints allow researchers to rapidly predict material behavior, solve inverse design problems (determining which material and process will yield a desired property), and navigate the complex, multi-dimensional space of material possibilities with unprecedented efficiency [11] [9]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of PSP linkages and material fingerprints, framing them within the context of modern data-driven methodologies for novel material synthesis.

Foundational Principles of PSP Linkages

The Hierarchical Nature of Materials

A fundamental challenge in establishing PSP linkages lies in the hierarchical nature of materials, where critical structures form over multiple time and length scales [9]. At the atomic scale, elemental interactions and short-range order define lattice structures or repeat units. These atomic arrangements collectively give rise to microstructures at larger scales, which ultimately determine macroscopic properties observable at the scale of practical application [9]. This multi-scale complexity means that minute variations at the atomic or microstructural level can profoundly influence final material performance, a phenomenon known in cheminformatics as an "activity cliff" [12].

Table 1: Key Entity Types in PSP Relationship Extraction

| Entity Type | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Material | Main material system discussed/developed/manipulated | Rene N5, Nickel-based Superalloy |

| Synthesis | Process/tools used to synthesize the material | Laser Powder Bed Fusion, alloy development |

| Microstructure | Location-specific features on the "micro" scale | Stray grains, grain boundaries, slip systems |

| Property | Any material attribute | Crystallographic orientation, environmental resistance |

| Characterization | Tools used to observe and quantify material attributes | EBSD, creep test |

| Environment | Conditions/parameters used during synthesis/characterization/operation | Temperature, applied stress, welding conditions |

| Phase | Materials phase (atomic scale) | γ precipitate |

| Phenomenon | Something that is changing or observable | Grain boundary sliding, deformation |

Formalizing PSP Relationships

The formalization of PSP relationships enables computational extraction and modeling. As illustrated in recent natural language processing research, scientific literature contains rich, unstructured descriptions of these relationships that can be transformed into structured knowledge using specialized annotation schemas [13]. These schemas define key entity types (Table 1) and their inter-relationships (Table 2), providing a standardized framework for knowledge representation.

Table 2: Core Relation Types in PSP Linkages

| Relation Type | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| PropertyOf | Specifies where a particular property is found | Stacking fault energy - PropertyOf - Alloy3 |

| ConditionOf | When one entity is contingent on another entity | Applied stress - ConditionOf - creep test |

| ObservedIn | When one entity is observed in another entity | GB deformations - ObservedIn - Creep |

| ResultOf | Connects "Result" with its associated entity/action/operation | Suppress (crack formation) - ResultOf - addition (of Ti & Ni) |

| FormOf | When one entity is a specific form of another entity | Single crystal - FormOf - Rene N5 |

The following diagram illustrates the core PSP paradigm and its integration with data-driven methodologies:

Core PSP and Data-Driven Integration

Material Fingerprints: The Data-Driven Descriptor

Definition and Purpose

A material fingerprint is a quantitative numerical representation that captures the essential characteristics of a material, enabling machine learning algorithms to process and analyze material data [10]. In essence, these fingerprints serve as the "DNA code" for materials, with individual descriptors acting as "genes" that connect fundamental material characteristics to macroscopic properties [9]. The primary purpose of fingerprinting is to transform complex, often qualitative material information into a structured numerical format suitable for computational analysis and machine learning.

The critical importance of effective fingerprinting cannot be overstated—the choice and quality of descriptors directly determine the success of subsequent predictive modeling. As noted in foundational materials informatics research, "This is such an enormously important step, requiring significant expertise and knowledge of the materials class and the application, i.e., 'domain expertise'" [10]. Proper fingerprinting must balance completeness and computational efficiency, providing sufficient information to capture relevant physics while remaining tractable for large-scale data analysis.

Classification of Fingerprint Types

Material fingerprints span multiple scales and modalities, reflecting the hierarchical nature of materials themselves. The table below categorizes major fingerprint types and their applications:

Table 3: Classification of Material Fingerprints

| Fingerprint Category | Descriptor Examples | Typical Applications | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic-Scale Descriptors | Elemental composition, atomic radius, electronegativity, valence electron count | Prediction of phase formation, thermodynamic properties | Fundamental physical basis; transferable across systems |

| Microstructural Descriptors | Grain size distribution, phase fractions, texture coefficients, topological parameters | Structure-property linkages for mechanical behavior | Direct connection to processing conditions |

| Synthesis Process Parameters | Temperature, pressure, time, cooling rates, energy input | Process-structure linkages, manufacturing optimization | Direct experimental control parameters |

| Computational Descriptors | Density Functional Theory (DFT) outputs, band structure parameters, phonon spectra | High-throughput screening of hypothetical materials | Ability to predict properties before synthesis |

| Geometric & Morphological Descriptors | Surface area-to-volume ratio, pore size distribution, particle morphology | Porous materials, composites, granular materials | Captures complex architectural features |

Data-Driven Methodologies for Establishing PSP Linkages

The Materials Informatics Workflow

The establishment of quantitative PSP linkages follows a systematic workflow that integrates materials science domain expertise with data science methodologies. This workflow typically encompasses several key stages, as illustrated in the following diagram and described in subsequent sections:

Data-Driven PSP Workflow

Data Acquisition and Generation

The foundation of any data-driven PSP model is a comprehensive, high-quality dataset. Data sources for materials informatics include:

- High-Throughput Experiments: Automated synthesis and characterization systems that generate large volumes of consistent experimental data [2]. For example, combinatorial thin-film synthesis enables rapid screening of composition-property relationships [2].

- Computational Simulations: Physics-based simulations across multiple scales, from quantum mechanical calculations to phase-field and finite element methods [9]. High-throughput density functional theory (HT-DFT) can calculate thermodynamic and electronic properties for tens to hundreds of thousands of material structures [9].

- Legacy Literature Data: Historical research data embedded in scientific publications, patents, and technical reports [13]. Extracting this information requires specialized natural language processing (NLP) techniques, including named entity recognition (NER) tailored to materials science concepts [13] [12].

The critical considerations for data acquisition include ensuring adequate data quality, completeness, and coverage of the relevant PSP space. As noted in recent foundation model research, "Materials exhibit intricate dependencies where minute details can significantly influence their properties" [12], emphasizing the need for sufficiently granular data.

Machine Learning for PSP Modeling

With fingerprinted materials data, machine learning algorithms establish the mapping between descriptors and target properties. The learning problem is formally defined as: Given a {materials → property} dataset, what is the best estimate of the property for a new material not in the original dataset? [10]

Several algorithmic approaches have proven effective for PSP modeling:

- Regression Methods: Kernel ridge regression, Gaussian process regression, and neural networks for continuous property prediction (e.g., strength, conductivity, band gap) [10].

- Classification Algorithms: Support vector machines, random forests, and deep learning models for categorical predictions (e.g., crystal structure classification, phase identification) [10].

- Dimensionality Reduction: Principal component analysis (PCA), t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE), and autoencoders for visualization and pattern recognition in high-dimensional descriptor spaces [10].

- Hybrid Physical-Statistical Models: Approaches that incorporate physical knowledge or constraints into statistical learning frameworks, enhancing interpretability and extrapolation capability [11].

A key advantage of these surrogate models is their computational efficiency—once trained and validated, "model predictions are instantaneous, which makes it possible to forecast the properties of existing, new, or hypothetical material compositions, purely based on past data, prior to performing expensive computations or physical experiments" [9].

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies

Protocol: Data-Driven Workflow for Additive Manufacturing PSP Linkages

This protocol outlines the methodology for establishing PSP linkages in additive manufacturing (AM) processes, based on established research workflows [14]:

1. Data Generation via Simulation:

- Employ Potts-kinetic Monte Carlo (kMC) simulations to model grain growth during directional solidification in AM.

- Use a cubic lattice domain where each site is assigned a "spin" identifying its grain membership.

- Simulate multiple passes of a localized heat source with controlled parameters: melt pool size (60-90 sites, corresponding to 0.3-0.45 mm), scan pattern, and power density.

- Generate an ensemble dataset of microstructures (e.g., 1798 simulations) by systematically varying process parameters [14].

2. Microstructure Quantification:

- Apply advanced image analysis to simulated microstructures to extract quantitative metrics.

- Calculate grain size distributions, grain aspect ratios, and crystallographic texture coefficients.

- Compute spatial correlation functions to capture topological features of the microstructures.

3. Dimensionality Reduction:

- Apply principal component analysis (PCA) to the quantitative microstructure metrics.

- Identify dominant microstructure components that capture the maximal variance within the dataset.

- Represent each microstructure using a low-dimensional vector of component scores.

4. Process-Structure Model Development:

- Employ regression techniques (e.g., Gaussian process regression, neural networks) to map process parameters to the low-dimensional microstructure representation.

- Validate model accuracy through cross-validation and holdout testing.

- Quantify uncertainty in predictions to identify regions of process space with high prediction variance.

5. Model Deployment:

- Utilize the validated P-S linkage to solve inverse problems: identifying process parameters that will yield a target microstructure.

- Implement active learning strategies to selectively acquire new data points that maximize model improvement.

Protocol: Natural Language Processing for PSP Relationship Extraction

This protocol details the methodology for extracting PSP relationships from scientific literature using natural language processing techniques [13]:

1. Corpus Construction:

- Manually select relevant publications from target domains (e.g., high-temperature materials, uncertainty quantification).

- Focus initially on paper abstracts, which typically contain condensed PSP relationships and are often accessible without subscription barriers.

2. Schema Development:

- Define a comprehensive annotation schema covering key PSP entity types (Table 1) and relation types (Table 2).

- Ensure schema attributes of uniqueness, clarity, and complementarity to support broad applicability across materials domains.

3. Text Annotation:

- Utilize the BRAT annotation tool to enrich text with domain knowledge.

- Have human annotators label entities and relations according to the defined schema.

- Establish annotation guidelines to ensure consistency across multiple annotators.

4. Model Training and Evaluation:

- Implement a conditional random field (CRF) model based on MatBERT—a domain-specific BERT variant trained on materials science literature.

- Compare performance with fine-tuned general-purpose LLMs (e.g., GPT-4) under identical conditions.

- Evaluate using standard metrics: precision, recall, and F1-score for both entity recognition and relation extraction.

5. Knowledge Graph Construction:

- Extract identified entities and relationships as structured tuples.

- Assemble tuples into a knowledge graph representing PSP relationships across the corpus.

- Enable querying and reasoning across the integrated knowledge base for materials discovery.

Research Reagent Solutions for PSP Studies

Table 4: Essential Research Materials and Computational Tools

| Item | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| High-Temperature Alloys | Model systems for PSP studies in extreme environments | Nickel-based superalloys (e.g., Rene N5), Ti-6Al-4V |

| Additive Manufacturing Platforms | Generating process-structure data for metal AM | Selective Laser Melting (SLM), Electron Beam Melting (EBM) systems |

| Characterization Tools | Quantifying microstructural features | EBSD (Electron Backscatter Diffraction), XRD (X-ray Diffraction), SEM |

| Domain-Specific Language Models | NLP for materials science text extraction | MatBERT, SciBERT - pre-trained on scientific corpora |

| Kinetic Monte Carlo Simulation Packages | Simulating microstructure evolution | SPPARKS kMC simulation suite with Potts model implementations |

| High-Throughput Computation | Generating large-scale materials property data | Density Functional Theory (DFT) codes (VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO) |

| Annotation Platforms | Creating labeled data for NLP tasks | BRAT rapid annotation tool for structured text enrichment |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Foundation Models for Materials Discovery

The materials science field is witnessing the emergence of foundation models—large-scale AI models pre-trained on broad data that can be adapted to diverse downstream tasks [12]. These models, including large language models (LLMs) adapted for scientific domains, show significant promise for advancing PSP linkages:

- Encoder-only models (e.g., materials-specific BERT variants) focus on understanding and representing input data, generating meaningful representations for property prediction [12].

- Decoder-only models are designed to generate new outputs sequentially, making them suitable for tasks such as generating novel material compositions or synthesis recipes [12].

- Multimodal models integrate information from text, images, tables, and molecular structures, capturing the diverse representations of materials knowledge [12].

These foundation models benefit from transfer learning, where knowledge acquired from large-scale pre-training on diverse datasets can be applied to specific materials problems with limited labeled examples [12]. This capability is particularly valuable in materials science, where expert-annotated data is often scarce [13].

Autonomous Experimentation and Inverse Design

The integration of PSP linkages with autonomous experimentation systems represents the cutting edge of materials discovery. Autonomous laboratories combine AI-driven decision-making with robotic synthesis and characterization, enabling real-time experimental feedback and adaptive experimentation strategies [11]. This closed-loop approach continuously refines PSP models while actively exploring the materials space.

A powerful application of established PSP linkages is inverse materials design, where target properties are specified and the models identify optimal material compositions and processing routes to achieve them [11] [9]. This inversion of the traditional discovery process is facilitated by the mathematical structure of surrogate PSP models, which "allow easy inversion due to their relatively simple mathematical reduction" compared to first-principles simulations [14].

Challenges and Emerging Solutions

Despite significant progress, several challenges remain in the widespread application of PSP linkages and material fingerprints:

- Data Quality and Standardization: Inconsistent data formats, reporting standards, and terminology hinder the integration of data from multiple sources. Solutions include developing standardized data formats, ontologies, and reporting guidelines for materials research [11].

- Model Interpretability: The "black box" nature of some complex machine learning models limits physical insight. Explainable AI (XAI) approaches are being developed to improve transparency and physical interpretability of PSP models [11].

- Uncertainty Quantification: Reliable estimation of prediction uncertainty is essential for responsible deployment of PSP models, particularly when extrapolating beyond the training data distribution. Bayesian methods and ensemble approaches provide frameworks for uncertainty-aware prediction [10].

- Integration of Physical Knowledge: Purely data-driven models may violate physical laws or constraints. Hybrid modeling approaches that incorporate physical principles into data-driven frameworks offer a promising path forward [11].

As these challenges are addressed, PSP linkages and material fingerprints will continue to transform materials discovery and development, enabling more efficient, targeted, and rational design of novel materials with tailored properties for specific applications.

In the landscape of data-driven materials science, public computational repositories have become indispensable for accelerating the discovery and synthesis of novel materials. The Materials Project (MP) stands as a paradigm, providing open, calculated data on inorganic materials to a global research community. This whitepaper provides a technical guide to the core data resources, application programming interfaces (APIs), and machine learning methodologies enabled by the Materials Project. Framed within a broader thesis on data-driven material synthesis, we detail protocols for accessing and utilizing these resources, present quantitative comparisons of material properties, and outline emerging machine learning frameworks that leverage this data, particularly for overcoming challenges of data scarcity. This guide is intended for researchers and scientists engaged in the computational design and experimental realization of new materials.

Launched in 2011, the Materials Project (MP) has evolved into a cornerstone platform for materials research, serving over 600,000 users worldwide by providing high-throughput computed data on inorganic materials [15]. Its core mission is to drive materials discovery by applying high-throughput density functional theory (DFT) calculations and making the results openly accessible. The platform functions as both a vast database and an integrated software ecosystem, enabling researchers to bypass costly and time-consuming experimental screens by pre-emptively screening material properties in silico. The data within MP is multi-faceted, encompassing primary properties obtained directly from DFT calculations—such as total energy, optimized atomic structure, and electronic band structure—and secondary properties, which require additional calculations involving applied perturbations, such as elastic tensors and piezoelectric coefficients [16]. This structured, hierarchical data architecture provides a foundational resource for probing structure-property relationships and guiding synthetic efforts toward promising candidates.

The Materials Project database is dynamic, with regular updates that expand its content and refine data quality based on improved computational methods [17]. The following tables summarize the key quantitative data available and the evolution of the database.

Table 1: Key Material Property Data Available in the Materials Project

| Property Category | Specific Properties | Data Availability Notes | Theoretical Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Properties | Total Energy, Formation Energy (E(f)), Optimized Atomic Structure, Electronic Band Gap (E(g)) | Direct outputs from DFT; widely available for ~146k materials [16]. | GGA/GGA+U, r2SCAN |

| Thermodynamic Stability | Energy Above Convex Hull (E(_{\text{Hull}})) | Crucial for assessing phase stability; 53% of materials in MP have E(_{\text{Hull}}) = 0 eV/atom [16]. | GGAGGA+UR2SCAN mixing scheme |

| Mechanical Properties | Elastic Tensor, Bulk Modulus, Shear Modulus | Scarce data; only ~4% of MP entries have elastic tensors [16]. | GGA/GGA+U |

| Electrochemical Properties | Insertion Electrode Data, Conversion Electrode Data | Used for battery material research [17]. | GGA/GGA+U |

| Electronic Structure | Band Structure, Density of States (DOS) | Available via task documents [17]. | GGA/GGA+U, r2SCAN |

| Phonon Properties | Phonon Band Structure, Phonon DOS | Available for ~1,500 materials computed with DFPT [17]. | DFPT |

Table 2: Recent Materials Project Database Updates (Selected Versions)

| Database Version | Release Date | Key Additions and Improvements |

|---|---|---|

| v2025.09.25 | Sept. 25, 2025 | Fixed filtering for insertion electrodes, adding ~1,200 documents [17]. |

| v2025.04.10 | April 18, 2025 | Added 30,000 GNoME-originated materials with r2SCAN calculations [17]. |

| v2025.02.12 | Feb. 12, 2025 | Added 1,073 recalculated Yb materials and ~30 new formate perovskites [17]. |

| v2024.12.18 | Dec. 20, 2024 | Added 15,483 GNoME materials with r2SCAN; modified valid material definition [17]. |

| v2022.10.28 | Oct. 28, 2022 | Initial pre-release of (R2)SCAN data alongside default GGA(+U) data [17]. |

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Data Access via the Materials Project API

The primary method for programmatic data retrieval from the Materials Project is through its official Python client, mp-api [18]. The following workflow details a standard protocol for accessing data for a material property prediction task.

Title: Data Retrieval via MP API

Protocol Steps:

- Client Installation and Setup: Install the

mp-apipackage using a Python package manager. Obtain a unique API key from the Materials Project website. - Session Initialization: Within a Python script or Jupyter notebook, initialize a session using the

MPResterclass with your API key. - Data Query: Use the

MPRestermethods to query data. Thesummaryendpoint is a common starting point for obtaining a wide array of pre-computed properties for a material. - Data Filtering and Extraction: Specify search criteria, such as material IDs (e.g., 'mp-1234') or chemical formulas, to retrieve specific documents. Extract relevant property fields (e.g.,

formation_energy_per_atom,band_gap,elasticity) from the returned documents. - Data Post-processing: Convert the extracted data into structured data formats like Pandas DataFrames or JSON files for subsequent analysis, visualization, or as input to machine learning models.

Machine Learning with Data-Scarce Properties

Mechanical properties like bulk and shear moduli are notoriously data-scarce in public databases. Transfer learning (TL) has emerged as a powerful protocol to address this [16].

Title: Transfer Learning Protocol

Protocol Steps:

- Source Model Pretraining: Train a deep learning model, such as a Graph Neural Network (GNN), on a data-rich source task where labels are abundant. A common example is the prediction of material formation energies, for which thousands of data points exist in MP [16]. This model learns general, low-level representations of atomic structures and interactions.

- Model Adaptation: Remove the final output layer of the pre-trained source model, which is specific to the source task. The remaining layers serve as a feature extractor that encodes fundamental materials chemistry and structure.

- Fine-tuning on Target Task: Add a new output layer suited for the data-scarce target property (e.g., a regression head for bulk modulus). Initialize the training with the weights from the pre-trained model and then train the entire network on the smaller target dataset. This process allows the model to adapt its general knowledge to the specific, data-scarce property.

- Validation: Rigorously assess the model's performance on a held-out test set for the target property to ensure it has generalized effectively without overfitting.

An alternative advanced protocol is the "Ensemble of Experts" (EE) approach, where multiple pre-trained models ("experts") are used to generate informative molecular fingerprints. These fingerprints, which encapsulate essential chemical information, are then used as input for a final model trained on the scarce target property, significantly enhancing prediction accuracy [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Key Software and Computational Tools for Materials Data Science

| Tool Name | Type/Function | Brief Description of Role |

|---|---|---|

| MP API (mp-api) | Data Access Client | The official Python client for programmatically querying and retrieving data from the Materials Project database [18]. |

| pymatgen | Materials Analysis | A robust, open-source Python library for materials analysis, which provides extensive support for parsing and analyzing MP data [15]. |

| Atomate2 | Workflow Orchestration | A modern software ecosystem for defining, running, and managing high-throughput computational materials science workflows, used for generating new data for MP [15]. |

| ALIGNN | Machine Learning Model | A GNN model that updates atom, bond, and bond-angle representations, capturing up to three-body interactions for accurate property prediction [16]. |

| CrysCo Framework | Machine Learning Model | A hybrid Transformer-Graph framework that incorporates four-body interactions and transfer learning for predicting energy-related and mechanical properties [16]. |

| VASP | Computational Core | A widely used software package for performing ab initio DFT calculations, which forms the computational backbone for the data in the Materials Project [15]. |

The Materials Project has fundamentally reshaped the approach to materials discovery by providing a centralized, open platform of computed properties. Its integration with modern data science practices, through accessible APIs and powerful software ecosystems, allows researchers to navigate the vast complexity of materials space efficiently. The future of this field lies in the continued expansion of databases with higher-fidelity calculations (e.g., r2SCAN), the development of more sophisticated machine learning models that can handle data scarcity and provide interpretable insights, and the deepening synergy between computation and experiment. By leveraging these public repositories and the methodologies outlined in this guide, researchers are well-equipped to accelerate the rational design and synthesis of next-generation functional materials.

The traditional materials development pipeline, often spanning 15 to 20 years from discovery to commercialization, is increasingly misaligned with the urgent demands of modern challenges such as climate change and the need for sustainable technologies [9]. This extended timeline is primarily due to the complex, hierarchical nature of materials and the resource-intensive process of experimentally exploring a vast compositional space [9]. This whitepaper details how a paradigm shift towards data-driven approaches is fundamentally compressing this timeline. By integrating Materials Informatics (MI), high-throughput (HT) methodologies, and advanced computational modeling, researchers can now rapidly navigate process-structure-property (PSP) linkages, prioritize promising candidates, and reduce reliance on serendipitous discovery. This document provides a technical guide for researchers and scientists, complete with quantitative benchmarks, experimental protocols, and visual workflows for implementing these accelerating technologies.

The Problem: Deconstructing the 20-Year Timeline

The protracted development cycle for novel materials is not a matter of a single bottleneck but a series of interconnected challenges across the R&D continuum.

The Multiple Length Scale Challenge

Material properties emerge from complex, hierarchical structures that span atomic, micro-, and macro-scales. Formulating a complete understanding of the Process-Structure-Property (PSP) linkages across these scales is a fundamental challenge in materials science [9]. The number of possible atomic and molecular arrangements is virtually infinite, making exhaustive experimental investigation impractical [9].

Table 1: Primary Factors Contributing to Extended Material Development Timelines

| Factor | Description | Impact on Timeline |

|---|---|---|

| Complex PSP Linkages | Multiscale structures (atomic to macro) dictate properties; understanding these relationships is time-consuming [9]. | High |

| Vast Compositional Space | Seemingly infinite ways to arrange atoms and molecules; testing is resource-intensive [9]. | High |

| Sequential Experimentation | Traditional "Edisonian" trial-and-error approach is slow and often depends on researcher intuition [9]. | High |

| Data Accessibility & Sharing | Experimental data is often not easily accessible or shareable, leading to repeated experiments [9]. | Medium |

| Regulatory & Validation Hurdles | Rigorous approval processes in regulated industries increase time and cost [9]. | Medium/High |

| Market & Value Misalignment | The value proposition of a new material may not initially align with market needs [9]. | Variable |

A notable example of these challenges is the history of lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO4). First synthesized in the 1930s, its potential as a high-performance cathode material for lithium-ion batteries was not identified until 1996—a gap of 66 years, illustrating the "hidden properties" in known materials that traditional methods can overlook [9].

Core Drivers: Data-Driven Acceleration Technologies

A new paradigm is augmenting traditional methods by leveraging computational power and advanced analytics to accelerate discovery and development [9].

Materials Informatics (MI) and Predictive Modeling

Materials Informatics underpins the acquisition and storage of materials data and the development of surrogate models to make rapid property predictions [9]. The core objective of MI is to accelerate materials discovery and development by leveraging data-driven algorithms to digest large volumes of complex data [9].

- The Material Fingerprint: A material is represented by a set of descriptors—its DNA code—that connects fundamental characteristics (e.g., elemental composition, crystal structure) to its macroscopic properties [9].

- Predictive Workflow: A model is trained on historical data to establish a mapping between a material's fingerprint and its properties. Once validated, the model can instantaneously forecast properties of new or hypothetical compositions, prioritizing candidates for further investigation [9].

- Uncertainty Quantification: Modern MI workflows incorporate methods to assess prediction uncertainties, guiding researchers on which experiments will most efficiently improve model accuracy [9].

High-Throughput (HT) and Automated Methodologies

HT techniques, both computational and experimental, enable the rapid screening of vast material libraries.

- HT Computational Screening: Methods like High-Throughput Density Functional Theory (HT-DFT) can calculate the thermodynamic and electronic properties of tens to hundreds of thousands of known or hypothetical material structures, creating a data explosion that fuels MI models [9].

- Self-Driving Labs: The integration of robotics, AI, and automated synthesis creates closed-loop systems that can propose, synthesize, and characterize new materials with minimal human intervention, dramatically accelerating the experimental validation cycle [20].

Investment and Funding Trends

Capital deployment is actively shifting towards these accelerating technologies. Investment in materials discovery has shown steady growth, with early-stage (pre-seed and seed) funding indicating strong confidence in the sector's long-term potential [20].

Table 2: Investment Trends in Materials Discovery (2020 - Mid-2025)

| Year | Equity Financing | Grant Funding | Key Drivers & Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | $56 Million | Not Specified | - |

| 2023 | Not Specified | Significant Growth | $56.8M grant to Infleqtion (quantum tech) from UKRI [20]. |

| 2024 | Not Specified | ~$149.87 Million | Near threefold increase; $100M grant to Mitra Chem for LFP cathode production [20]. |

| Mid-2025 | $206 Million | Not Specified | Cumulative growth from 2020; sector shows sustained private capital flow [20]. |

The funding landscape underscores a collaborative approach, with consistent government support and steady corporate investment driven by the strategic relevance of materials innovation to long-term R&D and sustainability goals [20].

Experimental Protocols: A Data-Driven Case Study

The following protocol details a data-driven methodology for developing sustainable biomass-based plastic from soya waste, exemplifying the accelerated approach [21].

Protocol: Synthesis and Optimization of Soy-Based Bioplastic

Objective: To develop a high-quality, biodegradable biomass-based plastic from soya waste using a data-driven synthesis and optimization workflow [21].

Diagram 1: Data-driven material development workflow.

Research Reagent Solutions:

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Soy-Based Bioplastic Synthesis

| Reagent | Function / Role in Synthesis |

|---|---|

| Soya Waste | Primary biomass feedstock; provides the base polymer matrix [21]. |

| Corn | Co-polymer component; modifies mechanical and barrier properties [21]. |

| Glycerol | Plasticizer; increases flexibility and reduces brittleness of the film [21]. |

| Vinegar | Provides acidic conditions; can influence cross-linking and polymerization. |

| Water | Solvent medium for the reaction mixture [21]. |

Methodology:

Experimental Design:

- Employ Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to design the experiment. RSM is a statistical technique used to build models, optimize processes, and explore the relationships between several explanatory variables and one or more response variables [21].

- Identify the independent variables (e.g., ratios of soya, corn, glycerol, vinegar) and their ranges.

- Use an RSM design (e.g., Central Composite Design) to generate a set of experimental runs that efficiently explores the multi-variable space.

Synthesis:

- For each experimental run specified by the RSM design, combine the reagents (soya waste, corn, glycerol, vinegar, water) in the specified proportions [21].

- Process the mixture under controlled conditions (e.g., temperature, stirring time) to form a homogeneous gel/film.

- Dry the synthesized material to produce the final bioplastic film.

Characterization and Data Acquisition:

- Analyze the synthesized bioplastic films using instrumental techniques:

- FTIR (Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy): To identify functional groups and chemical bonds.

- DTA (Differential Thermal Analysis) & TGA (Thermogravimetric Analysis): To study thermal stability and decomposition profiles [21].

- Measure physical properties in the laboratory, including:

- Analyze the synthesized bioplastic films using instrumental techniques:

Data Modeling and Optimization:

- Use advanced AI tools to develop predictive models:

- Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS).

- Artificial Neural Network (ANN) [21].

- Input the characterization data and experimental variables into these models.

- The models will learn the non-linear relationships between the reagent combinations and the resulting material properties.

- Use the validated model to identify the optimal reagent combination that produces a bioplastic with the desired properties (e.g., high tensile strength, specific biodegradability).

- Use advanced AI tools to develop predictive models:

The New Materials Development Workflow

The integration of the core drivers creates a streamlined, iterative workflow that replaces the traditional linear path.

Diagram 2: Integrated, iterative material development workflow.

This workflow demonstrates a fundamental shift from a sequential, trial-and-error process to a closed-loop, data-centric one. The continuous feedback of experimental data refines the predictive models, enhancing their accuracy with each iteration and ensuring that each physical experiment is maximally informative.

The 20-year timeline for novel materials development is no longer an immutable constraint. The convergence of Materials Informatics, high-throughput computation and experimentation, and strategic investment constitutes a proven set of core drivers for radical acceleration. By adopting these data-driven approaches, researchers and R&D organizations can systematically navigate the complexity of material design, unlock hidden properties in known systems, and rapidly bring to market the advanced materials required for a sustainable and technologically advanced future. The paradigm has shifted from one of slow, sequential discovery to one of rapid, intelligent innovation.

From Data to Discovery: Methodologies and Real-World Applications

In the field of novel material synthesis, the traditional trial-and-error approach is increasingly being supplemented by sophisticated data-driven algorithms that can model complex relationships, predict properties, and optimize synthesis parameters. These computational methods leverage statistical learning and artificial intelligence to extract meaningful patterns from experimental data, accelerating the discovery and development of new materials. Within this context, four classes of algorithms have demonstrated significant utility: Fuzzy Inference Systems (FIS), Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference Systems (ANFIS), and Ensemble Methods. These approaches offer complementary strengths for handling the multi-scale, multi-parameter challenges inherent in materials research, from managing uncertainty and imprecision in measurements to modeling highly nonlinear relationships between synthesis conditions and material properties. This review provides a comprehensive technical examination of these algorithms, their theoretical foundations, implementation protocols, and potential applications in material science and drug development research.

Fuzzy Inference Systems (FIS)

Theoretical Foundations

Fuzzy Inference Systems (FIS) are rule-based systems that utilize fuzzy set theory to map inputs to outputs, effectively handling uncertainty and imprecision in data [22]. Unlike traditional binary logic where values are either true or false, fuzzy logic allows for gradual transitions between states through membership functions that assign degrees of truth ranging from 0 to 1 [23]. This capability is particularly valuable in material science where experimental measurements often contain inherent uncertainties and qualitative observations from researchers need to be incorporated into quantitative models.

The fundamental components of a FIS include [22] [23]:

- Fuzzification: Converts crisp input values (real-world measurements) into fuzzy sets using membership functions

- Rule Base: Contains a collection of if-then rules that describe the system behavior using linguistic variables

- Inference Engine: Processes the fuzzy inputs through the rule base to generate fuzzy outputs

- Defuzzification: Converts the fuzzy output back into a crisp value for practical application

Implementation Methodologies

Two primary FIS architectures are commonly employed, each with distinct characteristics and application domains:

Table 1: Comparison of FIS Methodologies

| Feature | Mamdani FIS | Sugeno FIS |

|---|---|---|

| Output Type | Fuzzy set | Mathematical function (typically linear or constant) |

| Defuzzification | Computationally intensive (e.g., centroid method) | Computationally efficient (weighted average) |

| Interpretability | Highly intuitive, linguistically meaningful outputs | Less intuitive, mathematical outputs |

| Common Applications | Control systems, decision support | Optimization tasks, complex systems |

The Mamdani system, one of the earliest FIS implementations, uses fuzzy sets for both inputs and outputs, making it highly intuitive for capturing expert knowledge [23]. For material synthesis, this might involve rules such as: "If temperature is high AND pressure is medium, THEN crystal quality is good." The Sugeno model, by contrast, employs crisp functions in the consequent part of rules, typically as linear combinations of input variables, offering computational advantages for complex optimization problems [23].

Experimental Protocol for Material Synthesis Application

Implementing FIS for material synthesis parameter optimization involves these methodical steps:

System Identification: Define input variables (e.g., precursor concentration, temperature, pressure, reaction time) and output variables (e.g., material purity, yield, particle size) based on experimental objectives.

Fuzzification Setup: For each input variable, define 3-5 linguistic terms (e.g., "low," "medium," "high") with appropriate membership functions. Gaussian membership functions are commonly used for smooth transitions, defined as: μ(x) = exp(-(x - c)²/(2σ²)), where c represents the center and σ controls the width [22].

Rule Base Development: Construct if-then rules based on expert knowledge or preliminary experimental data. For a system with N input variables each having M linguistic values, the maximum number of possible rules is Mᴺ, though practical implementations often use a curated subset.

Inference Configuration: Select appropriate fuzzy operators (AND typically as minimum, OR as maximum) and implication method (usually minimum or product).

Defuzzification Method: Choose an appropriate defuzzification technique. The centroid method is most common for Mamdani systems, calculated as: y = ∫y·μ(y)dy/∫μ(y)dy [22].

Figure 1: Fuzzy Inference System Architectural Workflow

Artificial Neural Networks (ANN)

Fundamental Principles

Artificial Neural Networks are computational models inspired by biological neural networks, capable of learning complex nonlinear relationships directly from data through a training process [24]. This data-driven approach is particularly advantageous in material science where the underlying physical models may be poorly understood or excessively complex. ANNs excel at pattern recognition, function approximation, and prediction tasks, making them suitable for modeling the relationship between material synthesis parameters and resulting properties.

The basic building block of an ANN is the artificial neuron, which receives weighted inputs, applies an activation function, and produces an output. These neurons are organized in layers: an input layer that receives the feature vectors, one or more hidden layers that transform the inputs, and an output layer that produces the final prediction [24]. The power of ANNs lies in their ability to learn appropriate weights and biases through optimization algorithms like backpropagation, gradually minimizing the difference between predictions and actual observations.

Network Architectures and Training

Several ANN architectures have proven useful in material informatics:

Table 2: ANN Architectures for Material Research

| Architecture | Structure | Strengths | Material Science Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feedforward Networks | Sequential layers, unidirectional connections | Universal function approximation, simple implementation | Property prediction, quality control |

| Recurrent Networks | Cycles allowing information persistence | Temporal dynamic modeling | Time-dependent synthesis processes |

| Convolutional Networks | Local connectivity, parameter sharing | Spatial hierarchy learning | Microstructure analysis, spectral data |

The training process involves these critical steps:

Data Preparation: Normalize input and output variables to similar ranges (typically 0-1 or -1 to 1) to ensure stable convergence.

Network Initialization: Initialize weights randomly using methods like Xavier or He initialization to break symmetry and ensure efficient learning.

Forward Propagation: Pass input data through the network to generate predictions: z⁽ˡ⁾ = W⁽ˡ⁾a⁽ˡ⁻¹⁾ + b⁽ˡ⁾, a⁽ˡ⁾ = g⁽ˡ⁾(z⁽ˡ⁾), where W represents weights, b biases, a activations, and g activation functions.

Loss Calculation: Compute the error between predictions and targets using an appropriate loss function (e.g., mean squared error for regression, cross-entropy for classification).

Backpropagation: Calculate gradients of the loss with respect to all parameters using the chain rule: ∂L/∂W⁽ˡ⁾ = ∂L/∂a⁽ˡ⁾ · ∂a⁽ˡ⁾/∂z⁽ˡ⁾ · ∂z⁽ˡ⁾/∂W⁽ˡ⁾.

Parameter Update: Adjust weights and biases using optimization algorithms like gradient descent, Adam, or RMSProp to minimize the loss function.

Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS)

Hybrid Architecture

The Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) represents a powerful hybrid approach that integrates the learning capabilities of neural networks with the intuitive, knowledge-representation strengths of fuzzy logic [24]. This synergy creates a system that can construct fuzzy rules from data, automatically optimize membership function parameters, and model complex nonlinear relationships with minimal prior knowledge. ANFIS implements a first-order Takagi-Sugeno-Kang fuzzy model within a five-layer neural network-like structure [24], combining the quantitative precision of neural networks with the qualitative reasoning of fuzzy systems.

The ANFIS architecture consists of these five fundamental layers [24]:

Input Layer and Fuzzification: Each node in this layer corresponds to a linguistic label and calculates the membership degree of the input using a parameterized membership function, typically Gaussian: Oᵢʲ = μAᵢ(xⱼ) = exp(-((xⱼ - cᵢ)/σᵢ)²), where cᵢ and σᵢ are adaptive parameters.

Rule Layer: Each node represents a fuzzy rule and calculates the firing strength via product T-norm: wᵢ = μA₁(x₁) · μA₂(x₂) · ... · μAₙ(xₙ).

Normalization Layer: Nodes compute normalized firing strengths: w̄ᵢ = wᵢ/∑wⱼ.

Consequent Layer: Each node calculates the rule output based on a linear function of inputs: w̄ᵢfᵢ = w̄ᵢ(pᵢx₁ + qᵢx₂ + rᵢ), where {pᵢ, qᵢ, rᵢ} are consequent parameters.

Output Layer: The single node aggregates all incoming signals to produce the final crisp output: y = ∑w̄ᵢfᵢ.

Experimental Implementation Protocol

Implementing ANFIS for material synthesis optimization involves these methodical steps:

Data Collection and Partitioning: Collect a comprehensive dataset of synthesis parameters (inputs) and corresponding material properties (outputs). Partition the data into training (70%), testing (15%), and validation (15%) subsets [25].

Initial FIS Generation: Create an initial fuzzy inference system using grid partitioning or subtractive clustering to determine the number and initial parameters of membership functions and rules.

Hybrid Learning Configuration: Implement the two-pass hybrid learning algorithm where:

- In the forward pass, consequent parameters are identified using least squares estimation

- In the backward pass, premise parameters are updated using gradient descent

Model Training: Iteratively present training data to the network, adjusting parameters to minimize the error metric (typically mean squared error). Implement early stopping based on validation set performance to prevent overfitting.

Model Validation: Evaluate the trained model on the testing dataset using multiple metrics: accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and area under the ROC curve for classification; MSE, RMSE, and R² for regression [25].

Figure 2: ANFIS Five-Layer Architecture Diagram

Ensemble Methods

Theoretical Framework

Ensemble methods combine multiple machine learning models to produce a single, superior predictive model, typically achieving better performance than any individual constituent model [26]. This approach rests on the statistical principle that a collection of weak learners can be combined to form a strong learner, with the ensemble's variance and bias characteristics often superior to those of individual models. Ensemble learning addresses the fundamental bias-variance tradeoff in machine learning, where bias measures the average difference between predictions and true values, and variance measures prediction dispersion across different model realizations [26].

The effectiveness of ensemble methods depends on two key factors: the accuracy of individual models (each should perform better than random guessing) and their diversity (models should make different errors on unseen data) [27]. This diversity can be achieved through various techniques including using different training data subsets, different model architectures, or different feature subsets.

Key Ensemble Techniques

Three predominant ensemble paradigms have emerged as particularly effective across domains:

5.2.1 Bagging (Bootstrap Aggregating) Bagging is a parallel ensemble method that creates multiple versions of a base model using bootstrap resampling of the training data [26]. Each model is trained independently on a different random subset of the data (sampled with replacement), and their predictions are combined through majority voting (classification) or averaging (regression). The Random Forest algorithm extends bagging by randomizing both the data samples and feature subsets used for splitting decision trees, further increasing diversity among base learners [26].

5.2.2 Boosting Boosting is a sequential approach that iteratively builds an ensemble by focusing on instances that previous models misclassified [26]. Unlike bagging where models are built independently, boosting constructs models in sequence where each new model prioritizes training examples that previous models handled poorly. Popular implementations include:

- AdaBoost: Increases weights of misclassified instances in each iteration

- Gradient Boosting: Fits new models to the residual errors of the previous ensemble

5.2.3 Stacking (Stacked Generalization) Stacking employs a meta-learner that combines the predictions of multiple heterogeneous base models [26]. The base models are first trained on the original data, then their predictions become features for training the meta-model. This approach leverages the unique strengths of different algorithms, with the meta-learner learning optimal combination strategies.

Table 3: Ensemble Method Comparison

| Method | Training Approach | Base Learner Diversity | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bagging | Parallel, independent | Data sampling with replacement | Reduces variance, robust to outliers |

| Boosting | Sequential, adaptive | Weighting misclassified instances | Reduces bias, high accuracy |

| Stacking | Parallel with meta-learner | Different algorithms | Leverages diverse model strengths |

Implementation Protocol for Material Research

Implementing ensemble methods for material property prediction involves:

Base Learner Selection: Choose appropriate base models based on problem characteristics. For heterogeneous ensembles, select algorithms with complementary inductive biases (e.g., decision trees, SVMs, neural networks).

Diversity Generation: Implement diversity mechanisms:

- For bagging: Generate multiple bootstrap samples from the training data

- For boosting: Implement instance reweighting schemes

- For stacking: Train fundamentally different model types

Ensemble Construction:

- Bagging: Train each base learner on its bootstrap sample in parallel

- Boosting: Iteratively train models, adjusting instance weights based on previous model performance

- Stacking: Train base learners, then use their predictions as features for meta-learner

Prediction Aggregation: Combine base learner predictions using appropriate strategies:

- Majority voting for classification problems

- Weighted averaging or median for regression tasks

- Meta-learning for stacked ensembles

Recent research demonstrates that second-order ensembles (ensembles of ensembles) can achieve exceptional performance, with one study reporting DC = 0.992, R = 0.996, and RMSE = 0.136 for complex modeling tasks [28].

Comparative Analysis and Applications

Algorithm Selection Framework

Choosing the appropriate algorithm depends on multiple factors including data characteristics, problem requirements, and computational resources. The following guidelines assist in algorithm selection for material science applications:

- FIS: Most suitable when expert knowledge is available for rule formulation, system transparency is important, or uncertainty management is critical

- ANN: Preferred for problems with abundant data, complex nonlinear relationships, and when model interpretability is secondary to predictive accuracy

- ANFIS: Optimal balance between interpretability and learning capability, especially when both data and partial theoretical understanding are available

- Ensemble Methods: Most appropriate for maximizing predictive accuracy, particularly when diverse modeling perspectives can capture complementary aspects of the problem

Table 4: Performance Comparison Across Domains

| Algorithm | Reported Accuracy | Application Domain | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANFIS | 83.4% accuracy, 86% specificity [25] | Coronary artery disease diagnosis | Handles uncertainty, combines learning and reasoning |

| 2nd-Order Ensemble | DC = 0.992, R = 0.996, RMSE = 0.136 [28] | Biological Oxygen Demand modeling | Superior predictive performance, robust to noise |

| Logistic Regression | 72.4% accuracy, 81.5% AUC [25] | Medical diagnosis | Interpretable, well-calibrated probabilities |

| FIS | Security evaluation of cloud providers [29] | Trust assessment | Natural uncertainty handling, interpretable rules |

Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing these algorithms requires both computational tools and methodological components:

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for Algorithm Implementation

| Reagent Solution | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| MATLAB with Fuzzy Logic Toolbox | FIS and ANFIS development | Membership function tuning, rule base optimization, surface viewer analysis |

| Python Scikit-learn | Ensemble method implementation | BaggingClassifier, StackingClassifier, RandomForestRegressor |

| XGBoost Library | Gradient boosting implementation | State-of-the-art boosting with regularization, handles missing data |

| SMOTE Algorithm | Handling imbalanced datasets [25] | Synthetic minority oversampling for classification with rare materials |

| Cross-Validation Modules | Model evaluation and hyperparameter tuning | K-fold validation, stratified sampling, nested cross-validation |

Data-driven algorithms represent powerful tools for accelerating material discovery and optimization. FIS provides a transparent framework for incorporating expert knowledge, ANNs offer powerful pattern recognition capabilities, ANFIS combines the strengths of both approaches, and ensemble methods deliver state-of-the-art predictive performance. The selection of appropriate algorithms depends on specific research objectives, data characteristics, and interpretability requirements. As material science continues to evolve toward data-intensive methodologies, these computational approaches will play increasingly central roles in unraveling complex synthesis-structure-property relationships and enabling the rational design of novel materials with tailored characteristics. Future directions likely include increased integration of physical models with data-driven approaches, automated machine learning pipelines for algorithm selection and hyperparameter optimization, and the development of specialized architectures for multi-scale material modeling.