CSLLM: How the Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model is Revolutionizing Drug Discovery and Materials Design

The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM) framework represents a groundbreaking shift in predicting material synthesizability, a critical bottleneck in drug development and materials science.

CSLLM: How the Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model is Revolutionizing Drug Discovery and Materials Design

Abstract

The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM) framework represents a groundbreaking shift in predicting material synthesizability, a critical bottleneck in drug development and materials science. This article explores how CSLLM's three specialized models achieve unprecedented accuracy (98.6%) in predicting synthesizability, classifying synthetic methods, and identifying precursors for 3D crystal structures. We examine CSLLM's foundational architecture, its methodological applications in biomedical research, optimization strategies to overcome data limitations, and validation against traditional thermodynamic approaches. For researchers and drug development professionals, this comprehensive analysis demonstrates CSLLM's potential to dramatically accelerate the translation of theoretical compounds into synthesized candidates for therapeutic applications.

The Synthesizability Challenge: Understanding CSLLM's Foundation and Core Architecture

The journey from a computationally designed drug molecule to a manufactured product is fraught with a critical, often underestimated, bottleneck: the reliable prediction of crystal synthesizability. This challenge represents a fundamental gap in modern drug development, where the transition from theoretical structures to experimentally accessible solid forms determines the viability of countless therapeutic candidates. The discovery and development of new drugs remains one of the riskiest, costliest, and most resource-intensive processes in healthcare, with approximately 90% of drug candidates failing during pre-clinical and clinical stages [1]. A significant contributor to these failures lies in the unpredictable solid-form landscape of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), where late-appearing polymorphs can jeopardize product stability, efficacy, and safety [2].

Traditional approaches to identifying synthesizable crystal structures have relied heavily on thermodynamic stability metrics, particularly energy above the convex hull calculated via density functional theory (DFT) [3]. However, these methods exhibit a significant gap between predicted stability and actual synthesizability, as numerous structures with favorable formation energies remain unsynthesized, while various metastable structures are successfully synthesized despite less favorable formation energies [3]. This discrepancy highlights the complex interplay of kinetic factors, synthetic pathways, and precursor selection that governs practical synthesizability—factors largely overlooked by conventional stability assessments.

The emergence of specialized computational frameworks like the Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM) represents a paradigm shift in addressing this bottleneck [3]. By leveraging large language models fine-tuned on comprehensive materials data, these approaches aim to bridge the gap between theoretical prediction and experimental realization, offering unprecedented accuracy in synthesizability assessment while simultaneously suggesting viable synthetic methods and precursors.

The Synthesizability Prediction Landscape

Limitations of Conventional Methods

Traditional synthesizability assessment relies primarily on two computational approaches: thermodynamic stability analysis and kinetic stability evaluation. Thermodynamic methods typically compute the energy above the convex hull via DFT calculations, with structures having formation energies ≥0.1 eV/atom generally considered unstable [3]. Kinetic approaches assess stability through phonon spectrum analyses, identifying structures with imaginary phonon frequencies as potentially unstable [3]. However, both methods demonstrate limited correlation with experimental synthesizability, achieving only 74.1% and 82.2% accuracy respectively in comparative studies [3].

The fundamental limitation of these conventional approaches lies in their narrow focus on equilibrium properties, failing to capture the complex, non-equilibrium conditions of actual synthetic environments. As Bartel (2022) notes, thermodynamic methods typically "overlook finite-temperature effects, namely entropic and kinetic factors, that govern synthetic accessibility" [4]. This explains why numerous metastable structures with less favorable formation energies are successfully synthesized, while many theoretically stable structures remain elusive.

Data Challenges in Synthesizability Prediction

A primary obstacle in developing accurate synthesizability predictors is the curation of balanced training data containing both synthesizable and non-synthesizable examples. Positive samples (synthesizable crystals) can be sourced from experimental databases like the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), but constructing reliable negative samples presents considerable challenges [3]. Common approaches include:

- Treating structures with unknown synthesizability as negative samples, which inevitably introduces numerous synthesizable structures into the negative set [3]

- Collecting unobserved structures from well-studied compositions, though such datasets are limited in scale (approximately 3,000 samples) [3]

- Employing semi-supervised methods like positive-unlabeled learning, achieving 87.9% accuracy for 3D crystals [3]

- Using failed experimental data as negative samples, though this approach is often constrained to specific material systems [3]

The CSLLM framework addressed this challenge by employing a pre-trained PU learning model to generate CLscores for 1,401,562 theoretical structures, selecting 80,000 structures with the lowest scores (CLscore <0.1) as high-confidence negative examples, while curating 70,120 synthesizable structures from ICSD as positive examples [3].

Performance Comparison of Synthesizability Assessment Methods

Table 1: Quantitative comparison of synthesizability prediction approaches

| Method | Accuracy | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamic (Energy Above Hull ≥0.1 eV/atom) | 74.1% | Strong theoretical foundation, widely implemented | Overlooks kinetic accessibility, poor correlation with experimental synthesis |

| Kinetic (Phonon Frequency ≥ -0.1 THz) | 82.2% | Accounts for dynamic stability | Computationally expensive, limited predictive value |

| PU Learning Models | 87.9% | Addresses data labeling challenges | Moderate accuracy, limited to specific material systems |

| Teacher-Student Dual Network | 92.9% | Improved accuracy over basic PU learning | Complex architecture, computational overhead |

| CSLLM Framework | 98.6% | High accuracy, suggests synthesis methods & precursors | Requires specialized text representation of crystals |

The CSLLM Framework: Architecture and Implementation

Model Architecture and Specialization

The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model framework employs a specialized multi-component architecture consisting of three fine-tuned LLMs, each dedicated to a specific aspect of the synthesis prediction pipeline [3]:

- Synthesizability LLM: Predicts whether an arbitrary 3D crystal structure is synthesizable, achieving 98.6% accuracy on testing data [3]

- Method LLM: Classifies appropriate synthetic methods (solid-state or solution), exceeding 90% accuracy [3]

- Precursor LLM: Identifies suitable solid-state synthetic precursors for binary and ternary compounds, achieving 80.2% prediction success [3]

This tripartite architecture enables end-to-end synthesis planning, from initial synthesizability assessment to specific synthetic routes and precursor recommendations. The exceptional performance of CSLLM arises from "domain-focused fine-tuning, which aligns the broad linguistic features of LLMs with material features critical to synthesizability, thereby refining its attention mechanisms and reducing hallucinations" [3].

Material Representation and Data Processing

A critical innovation enabling CSLLM's success is the development of an efficient text representation for crystal structures termed "material string" [3]. Traditional crystal structure representations like CIF or POSCAR formats contain significant redundancy—for instance, multiple atomic coordinates at the same Wyckoff position can be inferred from one atomic coordinate along with space group and Wyckoff position symbols [3]. The material string representation eliminates such redundancies while preserving essential information on lattice parameters, composition, atomic coordinates, and symmetry.

The dataset construction for CSLLM training involved meticulous curation of 70,120 synthesizable crystal structures from ICSD, containing no more than 40 atoms and seven different elements, with disordered structures excluded to focus on ordered crystal structures [3]. The representation covers seven crystal systems (cubic, hexagonal, tetragonal, orthorhombic, monoclinic, triclinic, and trigonal) and elements with atomic numbers 1-94 (excluding 85 and 87), providing comprehensive coverage of inorganic crystal space [3].

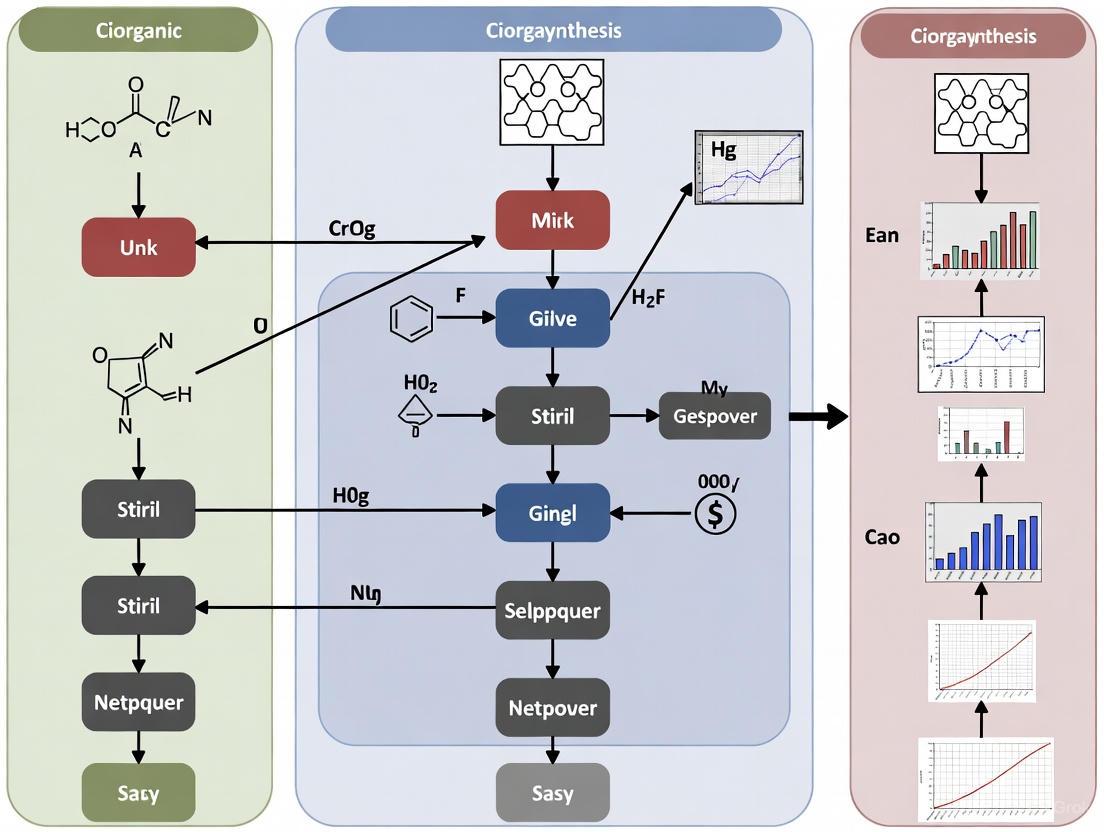

Diagram 1: CSLLM Framework Workflow. The process begins with crystal structure conversion to text representation, followed by sequential analysis through three specialized LLMs to generate a comprehensive synthesis plan.

Experimental Validation and Performance

The CSLLM framework was rigorously validated through multiple experimental paradigms. In standard testing, the Synthesizability LLM achieved 98.6% accuracy, significantly outperforming traditional thermodynamic (74.1%) and kinetic (82.2%) methods [3]. More importantly, the model demonstrated exceptional generalization capability, maintaining 97.9% accuracy when predicting synthesizability of experimental structures with complexity considerably exceeding that of the training data [3].

In a large-scale practical demonstration, a synthesizability-guided pipeline similar to CSLLM was applied to screen over 4.4 million computational structures from major materials databases [4]. The pipeline identified 24 highly synthesizable candidates, of which 16 were selected for experimental synthesis attempts. Remarkably, 7 of these targets were successfully synthesized and characterized, including one completely novel and one previously unreported structure [4]. The entire experimental process—from precursor selection to characterization—was completed in just three days, highlighting the transformative potential of accurate synthesizability prediction in accelerating materials discovery [4].

Protocols for Synthesizability Assessment and Validation

Protocol 1: CSLLM-Based Synthesizability Screening

Purpose: To identify synthesizable crystal structures from theoretical candidates and predict their synthetic pathways.

Materials and Data Requirements:

- Crystal structures in CIF or POSCAR format

- Access to CSLLM framework or equivalent synthesizability prediction tools

- Computational resources for structure preprocessing

Procedure:

- Structure Preprocessing: Convert candidate crystal structures to material string text representation by extracting essential crystal information (lattice parameters, composition, atomic coordinates, symmetry) while eliminating redundancies [3].

- Synthesizability Classification: Input material strings into Synthesizability LLM to obtain binary classification (synthesizable/non-synthesizable) with probability scores [3].

- Method Recommendation: For structures classified as synthesizable, process through Method LLM to identify appropriate synthetic approaches (solid-state vs. solution methods) [3].

- Precursor Identification: Input synthesizable structures into Precursor LLM to generate ranked lists of potential solid-state precursors [3].

- Synthesis Planning: Apply retrosynthetic planning models (e.g., Retro-Rank-In) to produce viable precursor combinations and use reaction condition predictors (e.g., SyntMTE) to estimate calcination temperatures [4].

- Experimental Prioritization: Rank candidates by synthesizability scores and feasibility of predicted synthesis routes for experimental validation.

Validation Metrics:

- Prediction accuracy against known experimental outcomes

- Success rate of predicted synthesis routes

- Characterization match between target and synthesized structures

Protocol 2: Experimental Validation of Predicted Synthesizable Structures

Purpose: To experimentally verify synthesizability predictions and characterize resulting materials.

Materials:

- High-purity precursor compounds

- Automated solid-state synthesis platform

- X-ray diffraction system for characterization

- Controlled atmosphere furnace

Procedure:

- Precursor Preparation: According to CSLLM precursor predictions, obtain high-purity starting materials and mix in stoichiometric ratios determined by balanced chemical equations [4].

- Reaction Parameter Setup: Program synthesis platform with predicted calcination temperatures from synthesis condition models [4].

- High-Throughput Synthesis: Execute parallel synthesis reactions for multiple candidates using automated laboratory platforms to maximize efficiency [4].

- In-Situ Monitoring: Employ characterization techniques during synthesis where possible to track reaction progress and phase formation.

- Product Characterization: Analyze synthesized products using X-ray diffraction (XRD) and compare patterns with target crystal structures [4].

- Phase Identification: Match characterization results to target structures to confirm successful synthesis, noting any polymorphic variations or impurity phases.

Validation Criteria:

- XRD pattern match between synthesized product and target structure

- Phase purity assessment

- Reproduction of predicted synthetic route

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 2: Key Resources for Synthesizability Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Application in Synthesizability Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Databases | ICSD, CSD | Source of synthesizable crystal structures | Provides positive training examples; ground truth validation |

| Theoretical Databases | Materials Project, GNoME, Alexandria | Source of theoretical crystal structures | Provides candidate structures for screening; source of negative examples |

| Synthesizability Models | CSLLM, PU Learning Models, CLscore | Predict synthesizability from structure/composition | Primary assessment tools for screening theoretical candidates |

| Synthesis Planning Tools | Retro-Rank-In, SyntMTE | Predict precursors and reaction conditions | Translates synthesizable predictions to practical recipes |

| Characterization Methods | XRD, Automated Lab Platforms | Verify synthesis success | Experimental validation of predictions |

The accurate prediction of crystal synthesizability represents a critical frontier in accelerating drug development and materials discovery. The CSLLM framework and similar synthesizability-guided pipelines demonstrate that integrating specialized computational models with experimental validation can successfully bridge the gap between theoretical prediction and practical synthesis. By achieving unprecedented accuracy in synthesizability assessment while simultaneously providing actionable synthetic guidance, these approaches directly address the fundamental bottleneck that has long hampered the translation of computational materials design to real-world applications.

The successful experimental synthesis of seven predicted targets—including previously unknown structures—in just three days provides compelling evidence that synthesizability prediction has matured from theoretical exercise to practical tool [4]. As these methodologies continue to evolve and integrate more deeply with automated experimental platforms, they promise to dramatically accelerate the discovery and development of new pharmaceutical compounds and functional materials, ultimately transforming the landscape of drug development.

The discovery of new functional materials is often bottlenecked not by theoretical design but by experimental synthesis. While computational methods and machine learning have successfully identified millions of candidate materials with promising properties, a significant gap persists between theoretical prediction and experimental realization. The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM) framework represents a transformative approach to bridging this gap, moving beyond traditional stability-based screening methods toward a more comprehensive prediction of synthesizability, viable synthesis methods, and appropriate chemical precursors [5].

This application note details the structured methodology and experimental protocols underlying the CSLLM framework, which employs three specialized large language models (LLMs) working in concert. Unlike conventional approaches that rely on thermodynamic or kinetic stability calculations, CSLLM leverages domain-adapted language models fine-tuned on comprehensive crystallographic data to make accurate, rapid predictions directly from crystal structure representations [5] [6]. This three-pronged architecture addresses the fundamental challenges in materials synthesis by decomposing the problem into logically sequential components: first determining if a structure can be synthesized, then identifying how it can be synthesized, and finally specifying what starting materials are required.

The framework's significance lies in its direct practical application to experimental materials science. By providing researchers with specific synthesis pathways and precursor recommendations, CSLLM transitions materials discovery from theoretical screening to actionable experimental guidance. With demonstrated 98.6% accuracy in synthesizability prediction, the framework substantially outperforms traditional methods based on formation energy (74.1% accuracy) or phonon stability (82.2% accuracy) [5]. This protocol document provides researchers with comprehensive methodological details to understand, implement, and extend the CSLLM approach for accelerating functional materials discovery.

Framework Architecture & Experimental Workflows

The Three-Component Architecture of CSLLM

The CSLLM framework employs a specialized, modular architecture where three distinct LLMs operate sequentially to resolve the complex problem of crystal synthesis prediction. Each model addresses a specific subproblem, with the output of earlier models informing the processing of subsequent ones [5] [6].

Synthesizability LLM: This first component operates as a binary classification system that evaluates whether an input crystal structure is synthesizable. It was fine-tuned on a balanced dataset of 70,120 synthesizable structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) and 80,000 non-synthesizable structures identified from theoretical databases using a positive-unlabeled (PU) learning model [5]. The model achieves its remarkable 98.6% accuracy through comprehensive training on diverse crystal systems spanning seven lattice types and compositions containing 1-7 elements [5].

Method LLM: For structures deemed synthesizable, this component classifies the appropriate synthesis pathway as either solid-state or solution-based methods. This classification is crucial for guiding experimentalists toward the correct synthetic approach, as the requirements for precursors, equipment, and conditions differ substantially between these pathways. The Method LLM demonstrates 91.0% accuracy in classifying synthetic routes, providing reliable guidance for experimental planning [5].

Precursor LLM: The final component identifies specific chemical precursors suitable for synthesizing the target material, with particular effectiveness for binary and ternary compounds. This model achieves an 80.2% success rate in predicting appropriate solid-state synthesis precursors, significantly accelerating the experimental workflow by reducing the trial-and-error typically associated with precursor selection [5].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the sequential operation and data flow between these three specialized LLMs:

Comprehensive Dataset Curation Protocol

The exceptional performance of CSLLM stems from its foundation on a carefully curated, balanced dataset of crystal structures. The dataset construction followed a rigorous protocol to ensure comprehensive coverage and minimize bias [5]:

Positive Sample Selection (Synthesizable Crystals): Researchers extracted 70,120 crystal structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) with specific inclusion criteria: structures containing no more than 40 atoms, no more than seven different elements, and exclusion of disordered structures. This filtering ensured dataset quality while maintaining diversity across crystal systems and compositions [5].

Negative Sample Generation (Non-Synthesizable Crystals): Using a pre-trained positive-unlabeled (PU) learning model developed by Jang et al., researchers computed CLscores for 1,401,562 theoretical structures from multiple sources (Materials Project, Computational Material Database, Open Quantum Materials Database, JARVIS). Structures with CLscores below 0.1 (indicating high probability of being non-synthesizable) were selected, resulting in 80,000 negative examples. Validation confirmed that 98.3% of positive samples had CLscores above this threshold, affirming the threshold's appropriateness [5].

Structural Diversity Analysis: The final dataset of 150,120 structures was visualized using t-SNE, confirming coverage of seven crystal systems (cubic, hexagonal, tetragonal, orthorhombic, monoclinic, triclinic, and trigonal) with appropriate representation across structure types. Elemental diversity spanned atomic numbers 1-94 (excluding 85 and 87), with compositions containing 1-7 elements, predominantly 2-4 elements [5].

Table: CSLLM Dataset Composition and Characteristics

| Dataset Aspect | Specifications | Source/Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Samples | 70,120 structures | Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) |

| Negative Samples | 80,000 structures | Multiple theoretical databases screened via PU learning |

| Element Diversity | Atomic numbers 1-94 (excl. 85, 87) | Comprehensive periodic table coverage |

| Structure Complexity | ≤40 atoms, ≤7 elements per structure | Controlled for model training efficiency |

| Crystal Systems | 7 systems covered | Cubic (most prevalent), hexagonal, tetragonal, orthorhombic, monoclinic, triclinic, trigonal |

Material String Representation: Textual Encoding of Crystal Structures

A critical innovation enabling CSLLM's application of LLMs to crystallographic data is the development of the "material string" representation, which converts complex 3D structural information into a compact text format suitable for language model processing [5]. The encoding protocol involves:

Lattice Parameter Encoding: The representation begins with the space group number followed by the three lattice constants (a, b, c) and three lattice angles (α, β, γ), providing complete unit cell geometry information in a compact format:

SP | a, b, c, α, β, γ[5].Atomic Constituent Specification: For each symmetrically distinct atomic site, the encoding includes the atomic symbol (AS), Wyckoff site multiplicity (WS), Wyckoff position symbol (WP), and fractional coordinates (x, y, z). This format efficiently captures the complete crystal structure without redundancy, as other equivalent positions can be generated through symmetry operations [5].

Comprehensive Structural Information: Compared to traditional CIF or POSCAR formats, the material string eliminates redundant atomic coordinate listings while preserving all essential crystallographic information. This compact representation (typically 100-500 characters) significantly reduces computational load during LLM processing while maintaining structural fidelity [5].

The material string representation was instrumental in fine-tuning the LLMs, as it provided a standardized, concise format for encoding the diverse crystal structures in the training dataset. This domain-specific adaptation of the input representation was crucial for achieving CSLLM's high prediction accuracy [5].

Implementation Protocols & Reagent Solutions

Model Training and Fine-Tuning Protocol

The CSLLM framework implementation requires specialized protocols for adapting general-purpose LLMs to the specific domain of crystal synthesis prediction. The fine-tuning process follows these methodological steps [5]:

Base Model Selection: While the specific base LLM architecture isn't explicitly detailed in the research, the approach involves leveraging a pre-trained foundation model with substantial parameters, following the standard practice of domain adaptation for scientific applications. The model is selected based on its demonstrated performance on structured data and scientific tasks [5].

Domain-Specific Fine-Tuning: The base model undergoes supervised fine-tuning using the curated dataset of 150,120 crystal structures represented as material strings. This process aligns the model's broad linguistic knowledge with crystallographic features critical for synthesizability assessment, refining its attention mechanisms to focus on structurally significant patterns rather than general language features [5].

Task-Specific Head Implementation: Each of the three CSLLM components incorporates specialized output heads fine-tuned for their specific predictive tasks. The Synthesizability LLM uses a binary classification head, the Method LLM employs a multi-class classification head for synthesis routes, and the Precursor LLM implements a sequence generation head for precursor recommendation [5].

Hallucination Reduction Techniques: Through domain-focused fine-tuning, the models learn to ground their predictions in crystallographic facts rather than generating speculative outputs. This specialized training significantly reduces the "hallucination" problem common in general-purpose LLMs, ensuring that predictions are based on structural patterns observed in the training data [5].

Research Reagent Solutions for CSLLM Implementation

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for CSLLM Deployment

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Role in CSLLM Framework | Implementation Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Crystallographic Databases | Source of training data and prediction inputs | ICSD (synthesizable structures), Materials Project, OQMD, JARVIS (theoretical structures) |

| Material String Representation | Text encoding for crystal structure data | Compact format: SP | a,b,c,α,β,γ | (AS1-WS1WP1) | (AS2-WS2WP2)... |

| PU Learning Model | Identification of non-synthesizable structures | Pre-trained model generating CLscores; threshold <0.1 for negative examples |

| Domain-Adapted LLMs | Core prediction engines for synthesizability, methods, precursors | Three specialized models fine-tuned on crystallographic data with material string inputs |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Property prediction for synthesizable candidates | Used alongside CSLLM to predict 23 key properties of identified synthesizable structures |

Experimental Validation Workflow

The validation protocol for CSLLM performance assessment involves multiple experimental phases to ensure prediction reliability [5]:

Accuracy Benchmarking: Researchers evaluated the Synthesizability LLM against traditional methods by comparing its predictions with thermodynamic stability (energy above hull ≥0.1 eV/atom) and kinetic stability (lowest phonon frequency ≥ -0.1 THz) metrics on the same test structures. The LLM demonstrated 98.6% accuracy versus 74.1% for thermodynamic and 82.2% for kinetic methods [5].

Generalization Testing: The framework was validated on structures with complexity exceeding training data, particularly those with large unit cells. The Synthesizability LLM maintained 97.9% accuracy on these challenging cases, demonstrating robust generalization capability beyond its training distribution [5].

Precursor Validation: For the Precursor LLM, researchers performed additional validation through reaction energy calculations and combinatorial analysis to confirm the thermodynamic feasibility of recommended precursor combinations, providing a secondary verification mechanism beyond the model's intrinsic predictions [5].

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow from data preparation to model deployment:

Performance Metrics & Output Analysis

Quantitative Performance Benchmarking

The CSLLM framework was rigorously evaluated against traditional synthesizability screening methods across multiple performance dimensions. The following table summarizes the comprehensive quantitative assessment reported in the research [5]:

Table: CSLLM Performance Metrics Across Three Specialized LLMs

| Model Component | Performance Metric | Results | Comparative Baseline Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthesizability LLM | Prediction Accuracy | 98.6% | Energy above hull (0.1 eV/atom): 74.1% Phonon stability (-0.1 THz): 82.2% |

| Synthesizability LLM | Generalization Accuracy | 97.9% | Tested on complex structures exceeding training data complexity |

| Method LLM | Classification Accuracy | 91.0% | Binary classification (solid-state vs. solution methods) |

| Precursor LLM | Prediction Success Rate | 80.2% | For binary and ternary compounds in solid-state synthesis |

| Framework Application | Synthesizable Candidates Identified | 45,632 materials | From 105,321 screened theoretical structures |

Experimental Deployment and Output Interpretation

The practical implementation of CSLLM involves specific protocols for processing crystal structures and interpreting model outputs:

Input Processing Protocol: Experimentalists begin by converting crystal structure files (CIF or POSCAR format) to the material string representation using the specified encoding scheme. This standardized input is then processed sequentially through the three LLM components [5].

Output Interpretation Guidelines: For the Synthesizability LLM, outputs with confidence scores above 0.95 can be considered high-probability synthesizable candidates. Method LLM outputs provide specific synthesis route classifications, while Precursor LLM recommendations should be evaluated alongside additional thermodynamic calculations when available [5].

Batch Processing Capability: The framework supports batch processing of multiple candidate structures, enabling high-throughput screening of theoretical materials databases. In research applications, CSLLM successfully evaluated 105,321 theoretical structures, identifying 45,632 as synthesizable candidates whose properties were subsequently predicted using graph neural networks [5].

User Interface Implementation: The research team developed a user-friendly CSLLM interface that accepts uploaded crystal structure files and automatically returns synthesizability predictions, recommended synthesis methods, and precursor suggestions, making the technology accessible to materials researchers without specialized computational backgrounds [5] [6].

The robust performance metrics and systematic implementation protocols establish CSLLM as a transformative framework for accelerating functional materials discovery. By bridging the critical gap between theoretical design and experimental synthesis, the approach enables researchers to focus experimental resources on the most promising, synthesizable candidate materials with predetermined synthesis pathways.

The discovery of new functional materials is often hindered by the significant challenge of accurately predicting whether a theoretically designed crystal structure can be successfully synthesized. Traditional approaches, which rely on metrics of thermodynamic and kinetic stability, have proven inadequate, as they do not fully capture the complex nature of real-world synthesis. The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM) framework represents a transformative methodology that leverages specialized large language models (LLMs) to accurately predict synthesizability, propose synthetic methods, and identify suitable precursors, thereby bridging the critical gap between computational prediction and experimental realization [5].

Conventional methods for assessing material synthesizability have primarily relied on computational assessments of thermodynamic stability, such as calculating the energy above the convex hull via density functional theory (DFT), or evaluations of kinetic stability through phonon spectrum analyses [5]. While these methods are valuable, they exhibit notable limitations; numerous structures with favorable formation energies remain unsynthesized, while various metastable structures with less favorable energies are successfully synthesized in the lab [5]. This discrepancy highlights that synthesizability is a complex process influenced by precursor choice and reaction conditions, factors that traditional stability metrics cannot fully encompass. The CSLLM framework addresses this gap by applying the advanced pattern recognition and predictive capabilities of LLMs, which have been fine-tuned on extensive materials data, to deliver a more direct and accurate assessment of a material's potential for successful synthesis.

Quantitative Performance Comparison: CSLLM vs. Traditional Methods

The table below summarizes the performance of the CSLLM framework against traditional stability-based screening methods, demonstrating its superior accuracy and expanded capabilities.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

| Prediction Method | Key Metric | Reported Accuracy/Success Rate | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSLLM (Synthesizability LLM) | Synthesizability Classification | 98.6% Accuracy [5] | Requires a comprehensive, balanced dataset for training. |

| Traditional Thermodynamic | Energy Above Hull (≥0.1 eV/atom) | 74.1% Accuracy [5] | Fails to account for kinetic factors and synthesis pathways. |

| Traditional Kinetic | Lowest Phonon Frequency (≥ -0.1 THz) | 82.2% Accuracy [5] | Computationally expensive; cannot identify synthesis routes. |

| CSLLM (Method LLM) | Synthetic Method Classification | 91.0% Accuracy [5] | Provides direct guidance on solid-state vs. solution routes. |

| CSLLM (Precursor LLM) | Precursor Identification | 80.2% Success Rate [5] | Identifies suitable chemical precursors for synthesis. |

The CSLLM Framework: Protocol and Workflow

The CSLLM framework employs a multi-component architecture, where three specialized LLMs work in concert to address the different aspects of the synthesis prediction problem. The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated process.

Protocol 1: Data Curation and "Material String" Representation

A critical first step in applying the CSLLM framework is the preparation of a balanced and comprehensive dataset and the conversion of crystal structures into a text-based format suitable for LLM processing.

- Objective: To construct a high-quality dataset for training and to create an efficient text representation for arbitrary 3D crystal structures.

- Materials and Software: Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), various theoretical structure databases (e.g., Materials Project), a pre-trained PU learning model for scoring [5].

- Procedure:

- Positive Sample Curation: Select experimentally confirmed, synthesizable crystal structures from the ICSD. The protocol used by CSLLM developers involved filtering for ordered structures with ≤40 atoms and ≤7 different elements, yielding 70,120 positive examples [5].

- Negative Sample Curation: Screen a large pool of theoretical structures (e.g., 1.4 million) using a pre-trained model to calculate a "CLscore." Select structures with the lowest scores (e.g., CLscore <0.1) as non-synthesizable negative examples. The CSLLM protocol curated 80,000 such structures to create a balanced dataset [5].

- Text Representation ("Material String"): Convert each crystal structure into a condensed text string that includes:

- Space Group (SP)

- Lattice Parameters:

a, b, c, α, β, γ - Atomic Species and Coordinates: A condensed list of atomic species (AS), Wyckoff site symbols (WS), and fractional coordinates (WP) in the format:

(AS1-WS1[WP1_x,WP1_y,WP1_z], AS2-WS2[WP2_x,WP2_y,WP2_z], ...)[5]. This representation eliminates redundant information found in standard CIF or POSCAR files, providing a clean, tokenizable input for the LLMs.

Protocol 2: Fine-tuning the Specialized LLMs

The core of the CSLLM framework involves fine-tuning three separate LLMs on the curated dataset.

- Objective: To adapt general-purpose LLMs into specialized models for synthesizability, method, and precursor prediction.

- Materials and Software: Pre-trained LLM (e.g., LLaMA), the curated dataset of material strings, fine-tuning framework (e.g., using PyTorch or TensorFlow with Hugging Face libraries).

- Procedure:

- Model Architecture Selection: Start with a pre-trained decoder-only transformer LLM.

- Task-Specific Fine-Tuning:

- Synthesizability LLM: Fine-tune the model as a binary classifier. The input is a material string, and the output is a probability of the structure being synthesizable. This model achieved a state-of-the-art test accuracy of 98.6% [5].

- Method LLM: Fine-tune the model as a multi-class classifier to recommend a synthetic pathway (e.g., solid-state or solution synthesis). This model achieved 91.0% classification accuracy [5].

- Precursor LLM: Fine-tune the model for a sequence-to-sequence task, taking a material string as input and generating the chemical formulas of likely solid-state precursors (e.g., for binary and ternary compounds). This model achieved an 80.2% success rate in precursor identification [5].

- Validation: Rigorously evaluate each model on a held-out test set to confirm accuracy and generalization ability, particularly for structures with complexity exceeding the training data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

The following table lists key computational tools and data resources essential for research in LLM-driven crystal synthesis prediction.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents & Solutions for LLM-driven Crystal Synthesis

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Crystallographic Information File (CIF) | Data Format | Standard text file format for representing crystallographic data; serves as a primary data source [7]. |

| Material String | Data Format | Condensed text representation of a crystal structure designed for efficient LLM processing [5]. |

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) | Database | Source of experimentally confirmed, synthesizable crystal structures for positive training examples [5]. |

| Materials Project (MP) Database | Database | Source of theoretical, computationally generated crystal structures for curating potential negative examples [5]. |

| Pre-trained PU Learning Model | Software Tool | Used to screen large volumes of theoretical structures and assign a non-synthesizability score (CLscore) for negative dataset creation [5]. |

| Quantized Low-Rank Adaptation (QLoRA) | Fine-tuning Method | An efficient fine-tuning technique that significantly reduces memory usage, enabling the adaptation of very large LLMs on limited hardware [8]. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | Software Tool | Used in conjunction with CSLLM to predict key electronic and thermodynamic properties of the identified synthesizable materials [5]. |

The CSLLM framework marks a significant paradigm shift in materials discovery. By moving beyond the limitations of traditional stability metrics, it provides a robust, data-driven pathway for evaluating synthesizability. Its integrated approach, which delivers not just a binary classification but also actionable insights into synthesis methods and precursors, offers a powerful tool for researchers and drug development professionals. This accelerates the transition from in-silico design to tangible material, ultimately paving the way for the more efficient discovery of novel functional materials.

Within the CSLLM (Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models) research framework, the construction of a high-quality, balanced dataset is a critical prerequisite for developing reliable models that can predict synthesizability, identify synthetic pathways, and suggest suitable precursors. The core challenge lies in curating a dataset that accurately reflects reality, containing both positively labeled synthesizable structures and credibly negative labeled non-synthesizable structures. This application note details comprehensive protocols for building such a dataset by integrating the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) with large repositories of theoretical structures, employing advanced machine learning screening to ensure balance and comprehensiveness.

The foundational data sources for constructing a balanced dataset are the ICSD for synthesizable crystals and aggregated theoretical databases for non-synthesizable candidates. The quantitative details of these sources are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Core Data Sources for Balanced Dataset Construction

| Data Source | Data Type | Key Characteristics & Usage | Volume |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [9] [10] | Experimentally synthesizable crystal structures (Positive Samples) | - Contains completely identified inorganic crystal structures.- Quality-assured data dating back to 1913.- Includes pure elements, minerals, metals, and intermetallic compounds.- Provides structural descriptors (Pearson symbol, ANX formula, Wyckoff sequences). | >240,000 crystal structures (2021.1 release) [10]. |

| Aggregated Theoretical Databases [5] | Hypothetical/predicted crystal structures (Source for Negative Samples) | - Includes structures from the Materials Project (MP), Computational Material Database, Open Quantum Materials Database, and JARVIS.- Structures are initially unlabeled regarding synthesizability.- A pre-trained PU learning model is used to screen for non-synthesizable candidates. | ~1.4 million structures [5]. |

Workflow for Constructing a Balanced Dataset

The following workflow diagram illustrates the multi-stage protocol for creating a balanced dataset of synthesizable and non-synthesizable crystal structures.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Sourcing and Filtering Positive Data from ICSD

This protocol outlines the acquisition and preparation of experimentally verified, synthesizable crystal structures from the ICSD.

- Objective: To extract a high-quality, manageable set of inorganic crystal structures confirmed to be synthesizable.

- Materials & Reagents:

- Procedure:

- Data Access: Access the ICSD web interface. Use the advanced search and retrieve function, typically found in the navigation menu [11].

- Initial Query: To gather a broad set of data, run a query with minimal constraints to download a large subset of the database.

- Data Filtering: Apply the following filters to the downloaded data to ensure structural manageability and focus on ordered crystals:

- Remove any structures with reported disorder.

- Retain only structures containing between 1 and 7 distinct elements.

- Retain only structures with a maximum of 40 atoms in the unit cell [5].

- Data Export: Export the final filtered set of structures. The CIF format is the standard and recommended format for downstream processing, as it contains comprehensive structural information [7] [5].

Protocol 2: Generating Negative Data from Theoretical Structures

This protocol describes the process of identifying credible non-synthesizable structures from large theoretical databases using a Positive-Unlabeled (PU) learning approach.

- Objective: To construct a robust set of negative samples (non-synthesizable structures) for balanced model training.

- Materials & Reagents:

- Procedure:

- Data Aggregation: Compile theoretical structures from multiple databases into a single pool. The example in the search results utilized a pool of 1,401,562 structures [5].

- PU Model Application: Process the entire pool of theoretical structures through the pre-trained PU learning model. This model will assign a CLscore (Crystal Likelihood score) to each structure, which is a metric reflecting the model's confidence that the structure is synthesizable.

- Threshold Selection: Define a strict CLscore threshold to identify high-confidence negative samples. The published methodology uses a threshold of CLscore < 0.1 [5].

- Negative Sample Selection: Select all structures with a CLscore below the defined threshold to form the negative sample set. To balance the dataset, a number of negative samples equivalent to the positive set can be randomly selected from this group (e.g., 80,000 negatives to match 70,120 positives) [5].

Protocol 3: Dataset Balancing and Validation

This protocol ensures the final dataset is balanced and representative for training machine learning models like the CSLLM.

- Objective: To create a finalized, balanced dataset and validate its chemical and structural diversity.

- Procedure:

- Combine and Balance: Combine the filtered positive samples from Protocol 1 and the selected negative samples from Protocol 2. The final dataset used in the CSLLM research contained 150,120 structures (70,120 positives + 80,000 negatives) [5].

- Diversity Validation: Perform a t-SNE (t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding) analysis on the final dataset to visually confirm that it encompasses a wide range of crystal systems (cubic, hexagonal, tetragonal, etc.) and chemical compositions (elements 1-94) [5]. This step verifies that the dataset is not only balanced in label count but also comprehensive in its coverage of inorganic chemical space.

- Format Conversion for LLM Training: Convert the final set of CIF files into a text representation suitable for efficient LLM fine-tuning. The CSLLM framework introduced a "material string" format, which is a more concise text representation that integrates space group, lattice parameters, and essential atomic coordinates, reducing redundancy found in standard CIF files [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Computational Tools and Resources for Dataset Construction

| Item Name | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| ICSD Subscription | The primary source for experimentally verified, synthesizable inorganic crystal structures used as positive samples [9] [10]. |

| Theoretical Structure Databases (MP, OQMD, JARVIS) | Provide a large pool of hypothetical structures from which high-confidence negative samples are sourced using machine learning screening [5]. |

| Pre-trained PU Learning Model | A machine learning model used to assign a CLscore to theoretical structures, enabling the identification of non-synthesizable candidates for the negative dataset [5]. |

| CIF File Parser | A software tool or script to read, process, and filter the Crystallographic Information Files (CIFs) downloaded from the ICSD and other databases [7]. |

| Text Representation Converter (e.g., to 'material string') | Converts the detailed CIF representation of a crystal into a condensed, reversible text format optimized for training Large Language Models, incorporating key information like space group and lattice parameters [5]. |

The integration of Large Language Models (LLMs) into materials science represents a paradigm shift in the discovery and design of novel functional materials. Within the Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM) framework, a critical challenge persists: transforming intricate, three-dimensional crystal structures into a format that is both computationally efficient and semantically rich for LLM processing. Traditional representations, such as the CIF (Crystallographic Information File) and POSCAR formats, while comprehensive, contain significant redundancy and are not optimized for natural language processing tasks. This application note details the development and implementation of a novel "material string" representation, a specialized text encoding that facilitates the accurate prediction of synthesizability, synthetic methods, and precursors for arbitrary 3D crystal structures within the CSLLM framework [5]. By providing a condensed, information-dense text format, the material string bridges the gap between structural chemistry and the textual understanding of LLMs, enabling state-of-the-art performance in predictive tasks essential for accelerating materials discovery.

The CSLLM Framework and the Need for Efficient Text Representation

The CSLLM framework employs three specialized LLMs to address distinct challenges in materials synthesis: predicting whether an arbitrary 3D crystal structure is synthesizable, identifying viable synthetic methods, and suggesting suitable chemical precursors [5]. The efficacy of these models is contingent upon the quality and structure of their input data. LLMs are fundamentally architected to process sequences of tokens (text); therefore, an effective representation must translate the complex, multi-faceted data of a crystal structure—including lattice parameters, atomic species, coordinates, and symmetry operations—into a coherent and compact textual sequence.

Standard crystallographic file formats are suboptimal for this purpose. The CIF format, though rich in detail, is verbose and contains repetitive entries for symmetrically equivalent atoms. The POSCAR format, used in the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package, is more concise but lacks explicit symmetry information, which is crucial for understanding material properties [5]. The proposed material string overcomes these limitations by distilling the essential information of a crystal structure into a single line of text, eliminating redundancy and creating an efficient input stream for fine-tuning and inference with LLMs. This domain-specific text representation is a cornerstone of the CSLLM's reported accuracy of 98.6% in synthesizability prediction [5].

Material String: Protocol for Text Representation

Format Specification and Grammar

The material string format is designed as a structured, pipe-separated sequence that encapsulates the complete information of an ordered crystal structure. Its formal grammar is as follows:

<Space Group Number> | <Lattice Parameters> | <Atomic Species and Wyckoff Positions>

A detailed breakdown of each component is provided in the table below.

Table 1: Comprehensive breakdown of the Material String format.

| Component | Description | Format & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Space Group Number | The international space group identifier. | An integer from 1 to 230. E.g., 225 for Fm-3m. |

| Lattice Parameters | The six fundamental parameters defining the unit cell. | a, b, c, α, β, γ (lengths in Å, angles in degrees). E.g., 5.43, 5.43, 5.43, 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 for a cubic cell. |

| Atomic Species & Wyckoff Positions | A list of unique atomic sites, each specifying the element and its crystallographic site. | (ASi-WSa[WPi, x, y, z]), (ASj-WSj[WPj, x, y, z]), ... • AS: Atomic Symbol (e.g., Si, O). • WS: Wyckoff Site symbol (e.g., a, 8c). • WP: Wyckoff Position coordinates. |

Step-by-Step Encoding Protocol

Protocol 1: Converting a Crystal Structure to a Material String

Objective: To accurately generate a material string representation from a crystallographic data source (e.g., a CIF file).

Input: A CIF file for an ordered crystal structure. Output: A single-line material string.

- Extract Space Group: Parse the CIF file to obtain the international space group number (e.g.,

_space_group_IT_number). - Extract Lattice Parameters: Parse the six lattice parameters from the CIF:

a,b,c,α,β, andγ. - Identify Unique Wyckoff Positions: Using the space group symmetry, analyze the crystal structure to determine all symmetrically unique atomic sites. This step is crucial for eliminating redundancy. For each unique site, note:

- The atomic symbol (e.g.,

Si). - The Wyckoff site symbol (e.g.,

a). - The fractional coordinates (

x, y, z) of a representative atom in that site.

- The atomic symbol (e.g.,

- Assemble the String: Concatenate the components in the specified order, using the pipe (

|) symbol as a delimiter and commas to separate values within a component.- Format:

SP | a, b, c, α, β, γ | (AS1-WS1[WP1, x1, y1, z1]), (AS2-WS2[WP2, x2, y2, z2]), ...

- Format:

Example: Encoding Silicon with a Diamond Structure

- Space Group: 225

- Lattice Parameter: a = 5.43 Å (cubic structure, so a=b=c=5.43, α=β=γ=90.0)

- Atomic Species & Wyckoff Positions: Silicon occupies the 8a Wyckoff position at (0, 0, 0). After symmetry reduction, this is represented by a single unique atom.

- Resulting Material String:

225 | 5.43, 5.43, 5.43, 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 | (Si-8a[0, 0, 0])

Decoding and Validation Protocol

Protocol 2: Reconstructing a Crystal Structure from a Material String

Objective: To verify the integrity and reversibility of the material string by reconstructing the original crystal structure.

Input: A valid material string. Output: A CIF file representing the crystal structure.

- Parse the String: Split the string using the pipe (

|) delimiter to isolate the three main components. - Apply Space Group Symmetry: Use the space group number and a crystallography library (e.g.,

pymatgenorase) to generate all symmetry operations for that group. - Replicate Atomic Positions: For each unique atomic site specified in the

(AS-WS[WP, x, y, z])component, apply the full set of symmetry operations to the given fractional coordinates. This generates the coordinates of all symmetrically equivalent atoms in the unit cell. - Generate CIF File: Using the lattice parameters and the complete set of atomic coordinates, write a standard CIF file. The correctness of the reconstruction can be validated by comparing the generated CIF to the original source file.

Experimental Integration and Workflow

The material string is not an isolated concept but is integrated into a comprehensive computational workflow within the CSLLM framework. The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end process, from data curation to final prediction.

Dataset Curation for Model Training

The development of the CSLLM relied on a meticulously curated dataset to ensure model robustness and generalizability [5].

- Positive Samples: 70,120 synthesizable crystal structures were sourced from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD). Structures were filtered to include a maximum of 40 atoms and 7 different elements, and disordered structures were excluded [5].

- Negative Samples: 80,000 non-synthesizable structures were identified from a pool of 1.4 million theoretical structures from databases like the Materials Project. A pre-trained Positive-Unlabeled (PU) learning model was used to calculate a CLscore, with scores below 0.1 indicating non-synthesizability [5].

This balanced dataset of 150,120 structures, spanning all seven crystal systems and elements 1-94, was then encoded into the material string format for model training.

The following table lists key computational tools and data resources critical for research in crystal structure representation and LLM applications in materials science.

Table 2: Key research reagents, tools, and data resources for CSLLM-related research.

| Item Name | Type | Function & Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| ICSD | Database | The Inorganic Crystal Structure Database provides a curated collection of experimentally synthesized crystal structures, serving as the primary source of positive (synthesizable) training examples [5]. |

| Materials Project | Database | A repository of computed crystal structures and properties, used as a source for generating potential negative (non-synthesizable) samples via PU learning [5]. |

| PU Learning Model | Algorithm | A semi-supervised machine learning model used to assign a CLscore to theoretical structures, enabling the identification of high-confidence non-synthesizable examples for the training dataset [5]. |

| CIF File | Data Format | The standard Crystallographic Information File is the initial source of truth for crystal structures before encoding into the material string format [5]. |

| Material String | Data Format | The efficient text representation developed for the CSLLM framework, enabling effective fine-tuning of LLMs for crystal structure analysis [5]. |

| PyTorch Geometric | Library | A deep learning library built upon PyTorch, used for developing Graph Neural Network models like CGTNet that predict material properties within integrated frameworks like T2MAT [12]. |

The material string representation establishes a new, efficient protocol for encoding complex crystal structures into a text-based format optimized for large language models. By integrating this representation into the CSLLM framework, researchers can achieve unprecedented accuracy in predicting synthesizability, synthetic pathways, and precursors. This methodology significantly bridges the gap between theoretical materials design and experimental realization, paving the way for accelerated and more reliable discovery of novel functional materials. The provided protocols for encoding, decoding, and dataset construction offer a reproducible pathway for the scientific community to build upon this work.

CSLLM in Action: Implementation Workflows and Real-World Applications in Biomedical Research

The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM) framework represents a transformative approach in materials science, bridging the critical gap between theoretical crystal structures and their experimental synthesis. This end-to-end workflow enables researchers to systematically evaluate synthesizability, identify appropriate synthetic methods, and select suitable precursors for arbitrary 3D crystal structures. The framework addresses a fundamental challenge in materials discovery: while computational methods have identified millions of candidate materials with promising properties, most remain theoretical constructs without clear pathways to experimental realization [5]. CSLLM leverages specialized large language models trained on comprehensive datasets of synthesizable and non-synthesizable structures, achieving unprecedented accuracy in predicting viable synthesis pathways. This application note details the complete workflow from crystal structure input to synthesis recommendation, providing researchers with practical protocols for implementing this cutting-edge technology in their materials development pipelines.

CSLLM Architecture and Core Components

The CSLLM framework employs three specialized LLMs that work in concert to transform crystal structure data into actionable synthesis recommendations:

- Synthesizability LLM: Predicts whether a given crystal structure can be successfully synthesized, achieving 98.6% accuracy [5]

- Method LLM: Classifies appropriate synthesis methods (solid-state or solution) with 91.0% accuracy [5]

- Precursor LLM: Identifies suitable solid-state synthetic precursors with 80.2% prediction success [5]

This modular architecture allows for targeted optimization of each component while maintaining interoperability across the entire workflow. The models were fine-tuned on a balanced dataset containing 70,120 synthesizable crystal structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) and 80,000 non-synthesizable structures identified through positive-unlabeled learning [5]. This comprehensive training enables robust predictions across diverse chemical systems and crystal symmetries.

Figure 1: CSLLM Framework Architecture showing the complete workflow from crystal structure input to synthesis recommendation

Input Representation: Material String Formulation

The Material String Format

A critical innovation enabling CSLLM's performance is the material string representation, which transforms complex crystal structure data into a standardized text format suitable for LLM processing. This representation efficiently encodes essential crystallographic information while eliminating redundancies present in traditional formats like CIF or POSCAR [5]. The material string incorporates:

- Space group (SP) information

- Lattice parameters (a, b, c, α, β, γ)

- Atomic species (AS) and their corresponding Wyckoff positions (WP)

- Composition ratios for multi-element systems

This compact representation preserves the complete crystallographic information needed for synthesizability assessment while optimizing for LLM processing efficiency. The format's reversibility allows reconstruction of full crystal structures, enabling seamless integration with existing materials informatics pipelines.

Conversion Protocol

Protocol: Converting Crystal Structures to Material String Representation

Input Preparation: Begin with a validated CIF or POSCAR file containing the target crystal structure. Ensure the structure is properly refined and contains no disordered atoms.

Symmetry Analysis:

- Determine the exact space group symmetry using tools like SPGLIB or FINDSYM

- Identify unique Wyckoff positions and their multiplicities

- Verify that atomic coordinates correspond to standardized settings

Parameter Extraction:

- Extract lattice parameters (a, b, c, α, β, γ) with precision to 0.001 Å and 0.01°

- List all atomic species present in the unit cell

- Determine fractional coordinates for one representative atom per Wyckoff position

String Assembly:

- Format data according to the pattern: "SP | a, b, c, α, β, γ | (AS1-WS1[WP1-coordinates], AS2-WS2[WP2-coordinates], ...)"

- Include composition ratios for multi-component systems

- Validate string reversibility by reconstructing and comparing to original structure

Synthesizability Prediction Workflow

Experimental Protocol for Synthesizability Assessment

Protocol: Implementing Synthesizability Predictions with CSLLM

Model Input Preparation:

- Convert target crystal structure to material string format as detailed in Section 3.2

- For batch processing, prepare JSONL files with each line containing a separate material string and corresponding identifier [13]

Synthesizability LLM Inference:

- Utilize the fine-tuned Synthesizability LLM with the prepared material string inputs

- The model returns a binary classification (synthesizable/non-synthesizable) with confidence scoring

- Threshold: Structures with confidence scores >0.95 are classified as synthesizable [5]

Validation and Interpretation:

- Compare CSLLM predictions with traditional stability metrics (formation energy, phonon spectra)

- For conflicting results, prioritize CSLLM predictions based on demonstrated superior accuracy

- Flag borderline cases (confidence scores 0.90-0.95) for additional validation

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Synthesizability Assessment Methods

| Assessment Method | Accuracy | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSLLM Framework | 98.6% [5] | High accuracy, rapid prediction, broad applicability | Requires structured data input |

| Energy Above Hull (≥0.1 eV/atom) | 74.1% [5] | Strong thermodynamic basis | Poor predictor for metastable phases |

| Phonon Stability (≥ -0.1 THz) | 82.2% [5] | Assesses kinetic stability | Computationally expensive, false negatives |

Case Study: Complex Structure Validation

The CSLLM framework demonstrates exceptional generalization capability, achieving 97.9% accuracy on complex structures with large unit cells significantly exceeding the complexity of its training data [5]. This performance advantage is particularly evident for:

- Metastable phases with favorable synthesis pathways but unfavorable thermodynamics

- Complex compositions with 4-7 elements where traditional methods struggle

- Novel structure types without close analogues in existing databases

Synthesis Method Classification

Method Prediction Protocol

Protocol: Synthetic Method Classification Using Method LLM

Input Requirements:

- Material string representation of synthesizable crystal structure

- Optional: Additional constraints (temperature limits, atmospheric requirements)

Classification Process:

- Method LLM analyzes structural and compositional features

- Returns classification: "solid-state" or "solution" synthesis

- Provides supporting rationale based on training data patterns

Method-Specific Considerations:

- Solid-state synthesis: Preferred for oxide materials, high-temperature stable phases

- Solution synthesis: Recommended for molecular crystals, hybrid materials, temperature-sensitive compounds

Table 2: Synthesis Method Classification Accuracy by Material Category

| Material Category | CSLLM Accuracy | Common Precursor Types | Typical Synthesis Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binary Oxides | 94.2% | Metal carbonates, oxides | 800-1400°C, air atmosphere |

| Ternary Compounds | 90.7% | Mixed metal oxides | 1000-1600°C, controlled atmosphere |

| Chalcogenides | 88.3% | Elemental precursors, binary chalcogenides | 500-900°C, sealed ampoules |

| Hybrid Materials | 91.5% | Molecular precursors, coordination compounds | 80-200°C, solvothermal conditions |

Precursor Identification and Validation

Precursor Prediction Workflow

The Precursor LLM identifies suitable solid-state synthetic precursors for binary and ternary compounds by analyzing compositional relationships and reaction thermodynamics. The model leverages patterns learned from experimental synthesis data to suggest precursor combinations that maximize yield and phase purity [5].

Protocol: Precursor Selection and Validation

Precursor Identification:

- Input material string of target compound into Precursor LLM

- Model returns 3-5 recommended precursor combinations ranked by predicted success probability

- Each recommendation includes expected reaction pathway and byproducts

Thermodynamic Validation:

- Calculate reaction energies for suggested precursor routes using DFT

- Prefer combinations with large negative reaction energies (ΔG < -0.1 eV/atom)

- Evaluate phase purity through competition analysis with potential side products

Experimental Optimization:

- Refine precursor ratios based on stoichiometric requirements

- Adjust processing conditions (temperature, time, atmosphere) based on similar known systems

- Implement iterative optimization with characterization feedback

Figure 2: Precursor identification and validation workflow showing iterative optimization process

Precursor Performance Metrics

Table 3: Precursor Prediction Success Rates by Compound Type

| Compound Type | Prediction Success Rate | Common Successful Precursors | Alternative Routes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perovskite Oxides | 85.4% | Carbonates (ACO₃), Oxide (B₂O₃) | Nitrates, hydroxides |

| Spinel Compounds | 78.9% | MO, M₂O₃ | Mixed oxide precursors |

| Garnet Phases | 72.3% | Stoichiometric oxide mixtures | Sol-gel precursors |

| Layered Oxides | 81.6% | Carbonates + oxides | Hydroxide precursors |

Integration with Materials Discovery Pipelines

High-Throughput Screening Implementation

The CSLLM framework enables efficient screening of theoretical material databases to identify synthesizable candidates with promising properties. The workflow processes thousands of structures simultaneously, significantly accelerating materials discovery [5].

Protocol: Large-Scale Synthesizability Screening

Database Preparation:

- Compile theoretical structures from sources like Materials Project, OQMD, JARVIS

- Convert all structures to material string format

- Organize in JSONL format for batch processing [13]

Parallelized Assessment:

- Implement CSLLM across distributed computing infrastructure

- Process structures in batches of 1,000-10,000

- Log all predictions with confidence scores for posterior analysis

Priority Ranking:

- Rank synthesizable structures by confidence score

- Cross-reference with property predictions from graph neural networks

- Select top candidates for experimental pursuit

Property-Structure Co-Optimization

Advanced implementations integrate CSLLM with property prediction models like Crystal Graph Transformer Networks (CGTNet) to simultaneously optimize for synthesizability and target properties [12]. This approach enables true multi-objective optimization in materials design.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for CSLLM Implementation

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Sources | ICSD, Materials Project, OQMD, JARVIS [5] | Provides training data and validation structures | Curate balanced datasets with synthesizable/non-synthesizable examples |

| Format Libraries | pymatgen, ASE, CIF parsers | Converts crystal structures to material string format | Ensure Wyckoff position standardization |

| LLM Frameworks | LangChain, Hugging Face Transformers [14] | Infrastructure for model fine-tuning and inference | Optimize for structured data processing |

| Validation Tools | DFT codes (VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO), phonon calculators | Validates synthesizability predictions | Compute formation energies, phonon spectra |

| Precursor Databases | Literature compilation, reaction databases | Training data for precursor prediction | Include successful synthetic routes from literature |

The CSLLM framework establishes a comprehensive end-to-end workflow from crystal structure input to synthesis recommendation, achieving unprecedented accuracy in synthesizability prediction (98.6%), method classification (91.0%), and precursor identification (80.2% success). The material string representation enables efficient processing of crystallographic information by specialized language models, while the modular architecture allows for continuous improvement of individual components. Implementation protocols detailed in this application note provide researchers with practical guidance for integrating CSLLM into their materials development pipelines, significantly accelerating the translation of theoretical predictions to synthesized materials. Future developments will focus on expanding precursor prediction to more complex compositions, integrating real-time experimental feedback, and incorporating additional synthesis parameters such as atmospheric requirements and heating profiles.

Application Note: Synergistic Framework for Autonomous Materials Discovery

The integration of the Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM) framework with the T2MAT (text-to-materials) agent establishes a powerful, closed-loop pipeline for the inverse design and validation of novel functional materials. This synergy addresses a critical bottleneck in computational materials science: transitioning from theoretical predictions of high-performing materials to the identification of realistically synthesizable candidates with defined production pathways. The CSLLM framework contributes specialized models for assessing synthesizability, predicting synthetic methods, and identifying precursors with high accuracy [5]. The T2MAT agent provides a universal interface that initiates material generation from a simple text prompt and manages an automated workflow for first-principles validation, exploring chemical spaces beyond existing databases [15]. When combined, these systems enable a more autonomous discovery process, minimizing reliance on human expertise and accelerating the development of new materials for applications ranging from drug development to energy storage.

This application note details the protocols for leveraging this integrated framework, its performance benchmarks, and the essential computational tools required for implementation. The unified workflow is designed for researchers and scientists aiming to rapidly identify and validate novel, synthesizable material structures with target properties.

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks of Core Models

The predictive performance of the individual components within the CSLLM and T2MAT frameworks is foundational to the integrated pipeline's reliability. The following tables summarize the key quantitative benchmarks for each model.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarks of the CSLLM Framework Components [5]

| CSLLM Model | Primary Function | Reported Accuracy | Key Benchmarking Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthesizability LLM | Predicts synthesizability of 3D crystal structures | 98.6% | Outperforms stability-based methods (74.1-82.2% accuracy) |

| Method LLM | Classifies possible synthetic methods (e.g., solid-state, solution) | 91.0% | For common binary and ternary compounds |

| Precursor LLM | Identifies suitable solid-state synthesis precursors | 80.2% | For common binary and ternary compounds |

Table 2: Key Components of the T2MAT Framework [15]

| T2MAT Component | Primary Function | Role in Integrated Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Text Interface | Accepts user-defined property goals via a single sentence | Initiates the inverse design process |

| CGTNet Model | Predicts material properties via a Crystal Graph Transformer NETwork | Captures long-range interactions for accurate property prediction |

| Automated Validation | Manages entirely automated first-principles calculations | Provides quantum-mechanical validation of generated structures |

Integrated Experimental & Computational Protocols

Protocol 1: Inverse Design and Synthesizability Screening of Novel Materials

Purpose: To generate novel crystal structures with user-specified target properties and subsequently identify the synthesizable candidates along with their potential precursors.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Input Specification: Provide a text-based description of the desired material properties to the T2MAT agent. Example: "Generate a layered semiconductor with a direct bandgap of 1.5 eV." [15]

- Structure Generation: The T2MAT agent explores the chemical space and uses its generative models to produce candidate crystal structures that meet the specified goal. This step operates beyond the constraints of existing material databases. [15]

- Property Validation: Employ the CGTNet model within T2MAT to predict a suite of properties for the generated candidates. Subsequently, execute an automated first-principles calculation (e.g., using Density Functional Theory) to validate the stability and properties of the generated structures with high fidelity. [15]

- Synthesizability Screening: Pass the validated candidate structures to the CSLLM framework. Use the Synthesizability LLM to evaluate and filter the list, retaining only structures predicted to be synthesizable with high confidence (98.6% accuracy). [5]

- Synthesis Route Prediction: For the synthesizable candidates, use the CSLLM Method LLM to classify the likely synthetic pathway (e.g., solid-state or solution method). Then, use the Precursor LLM to identify a shortlist of potential solid-state precursors for the target material. [5]

Expected Output: A curated list of novel, property-matched crystal structures predicted to be synthesizable, each accompanied by a recommended synthetic method and a set of potential precursor compounds.

Protocol 2: Validation of Synthesizability Predictions on Complex Structures

Purpose: To experimentally benchmark and validate the generalizability of the CSLLM synthesizability predictions, particularly for structures with complexity exceeding its training data.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Test Set Curation: Compile a dataset of experimentally reported crystal structures not present in the original CSLLM training data. This set should include structures with large unit cells or high elemental complexity. [5]

- Model Prediction: Process these experimental structures through the CSLLM Synthesizability LLM to obtain synthesizability predictions.

- Accuracy Assessment: Compare the model's predictions against the known experimental status of the structures (synthesized or not). The reported benchmark shows CSLLM can achieve 97.9% accuracy on such complex test sets, confirming its robust generalization ability. [5]

- Precursor Analysis: For structures correctly predicted as synthesizable, further validate the output of the Precursor LLM against the precursors reported in the experimental literature.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated pipeline combining T2MAT and CSLLM for automated material generation and synthesis planning.

Integrated T2MAT-CSLLM Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational tools and data resources that function as essential "reagents" in experiments utilizing the CSLLM and T2MAT frameworks.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CSLLM and T2MAT Workflows

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|