Cross-Domain Generalization in Generative Material Models: Strategies for Robust AI in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive examination of cross-domain generalization for generative AI models in material science and drug discovery.

Cross-Domain Generalization in Generative Material Models: Strategies for Robust AI in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of cross-domain generalization for generative AI models in material science and drug discovery. It explores the foundational shift from traditional descriptors to automated deep learning representations, details advanced methodological frameworks like graph neural networks and cross-domain feature augmentation, and addresses critical challenges including data scarcity and model interpretability. By synthesizing validation strategies and comparative analyses, this review equips researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to build more robust, generalizable models that can accelerate the discovery of novel therapeutics across diverse chemical spaces.

From Handcrafted Descriptors to Learned Representations: The Foundation of Molecular AI

The field of computational chemistry is undergoing a fundamental paradigm shift, moving from reliance on manually engineered descriptors toward automated feature extraction using deep learning. This transition enables data-driven predictions of molecular properties, inverse design of compounds, and accelerated discovery of chemical and crystalline materials—including organic molecules, inorganic solids, and catalytic systems [1]. Where researchers once depended on human-curated features such as molecular weight, polarity, or pre-defined structural descriptors, advanced neural architectures now automatically extract chemically relevant features directly from molecular structures, spectral data, and scientific literature. This automation has dramatically expanded the scope, accuracy, and scalability of computational approaches across drug discovery and materials science.

The integration of automated feature extraction with cross-domain generalization represents a particularly significant advancement. Generative material models can now leverage knowledge learned from one domain to accelerate discovery in unrelated domains. For instance, molecular representation learning has catalyzed this shift by employing graph neural networks, autoencoders, transformer architectures, and hybrid self-supervised learning frameworks to extract transferable features across chemical spaces [1]. This cross-domain capability is essential for real-world applications where labeled data may be scarce for specific domains of interest, but abundant in related areas.

The Evolution of Feature Extraction in Chemical Sciences

Historical Context: Manual Feature Engineering

Traditional computational chemistry relied heavily on manually engineered descriptors and human-curated features. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR/QSPR) modeling initially employed simple statistical models applied to small datasets of molecules characterized by a restricted array of descriptors [2]. Researchers would manually calculate or estimate molecular properties such as logP for lipophilicity, molar refractivity, hydrogen bond donor/acceptor counts, and topological indices. These descriptors, while chemically intuitive, were limited in their ability to capture complex, hierarchical molecular characteristics and required significant domain expertise to select and compute.

The limitations of this manual approach became increasingly apparent as chemical datasets grew in size and complexity. Human engineers could not possibly identify all chemically relevant features, especially those involving complex non-local interactions or higher-order patterns across molecular structures. This bottleneck constrained the predictive power of models and their applicability across diverse chemical domains.

The Rise of Automated Feature Learning

The advent of deep learning in computational chemistry has enabled automated feature extraction through representation learning, where algorithms discover optimal feature representations directly from raw molecular data across multiple domains [1]. This approach has demonstrated superior performance across numerous chemical tasks while reducing human bias in feature selection. As representation learning has matured, attention has shifted toward cross-domain generalization—the ability of models trained in one chemical domain to perform effectively in unrelated domains with different data distributions.

Table 1: Comparison of Feature Extraction Paradigms in Computational Chemistry

| Aspect | Manual Feature Engineering | Automated Feature Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Approach | Domain expert selection of chemically intuitive descriptors | Algorithmic discovery of features from raw data |

| Key Technologies | RDKit, Dragon, MOE descriptors | Graph Neural Networks, Autoencoders, Transformers |

| Feature Interpretability | High | Variable (addressed via XAI techniques) |

| Domain Transfer Capability | Limited | High (through cross-domain frameworks) |

| Data Requirements | Smaller datasets | Larger, diverse datasets |

| Representative Examples | Molecular weight, logP, polar surface area | Learned embeddings from molecular graphs |

Core Architectures for Automated Feature Extraction

Graph Neural Networks for Molecular Representation

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have emerged as a fundamental architecture for molecular feature extraction, naturally representing molecules as graphs with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges. Unlike string-based representations such as SMILES, GNNs preserve the topological structure of molecules and can learn features that capture complex relational patterns between atomic constituents. Modern GNN architectures perform message passing between connected atoms, enabling the learning of hierarchical representations that capture both local atomic environments and global molecular structure [1].

The cross-domain applicability of GNNs has been demonstrated across multiple chemical domains, from organic molecules to inorganic crystals. By learning fundamental principles of chemical bonding and spatial relationships, these models can transfer knowledge between disparate material classes. For instance, a GNN pretrained on organic molecule datasets can be fine-tuned for inorganic systems with minimal retraining, significantly reducing data requirements for new domains [1].

Transformer Architectures and Attention Mechanisms

Originally developed for natural language processing, transformer architectures have been adapted for chemical data through representations such as SMILES strings, SELFIES, or molecular fingerprints. The self-attention mechanism in transformers enables the model to weigh the importance of different molecular substructures dynamically based on the specific prediction task [3]. This capability allows transformers to identify complex, non-local relationships between functional groups that might escape manually designed descriptors.

Recent advancements have seen the development of domain-agnostic foundational models pretrained with chemical-oriented objectives. For example, RecBase employs a unified item tokenizer that encodes molecular representations into hierarchical concept identifiers, enabling structured representation and efficient vocabulary sharing across domains [4]. Such approaches demonstrate how transformer architectures can learn chemically meaningful features that transfer effectively across domain boundaries.

Multi-Modal and Cross-Domain Fusion Strategies

The most advanced automated feature extraction systems now employ multi-modal fusion strategies that integrate information from diverse molecular representations including graphs, sequences, and quantum chemical descriptors [1]. These approaches recognize that different molecular representations capture complementary aspects of chemical structure and properties, and that combining them can yield more robust and generalizable features.

Cross-modal alignment has been particularly powerful for domain generalization. For instance, vision-language models (VLMs) like CLIP have demonstrated strong cross-modal alignment capabilities that can enhance domain generalization [5]. When applied to chemical data, such models can align structural representations with textual descriptions of molecular properties, creating a shared embedding space that transfers well to unseen domains.

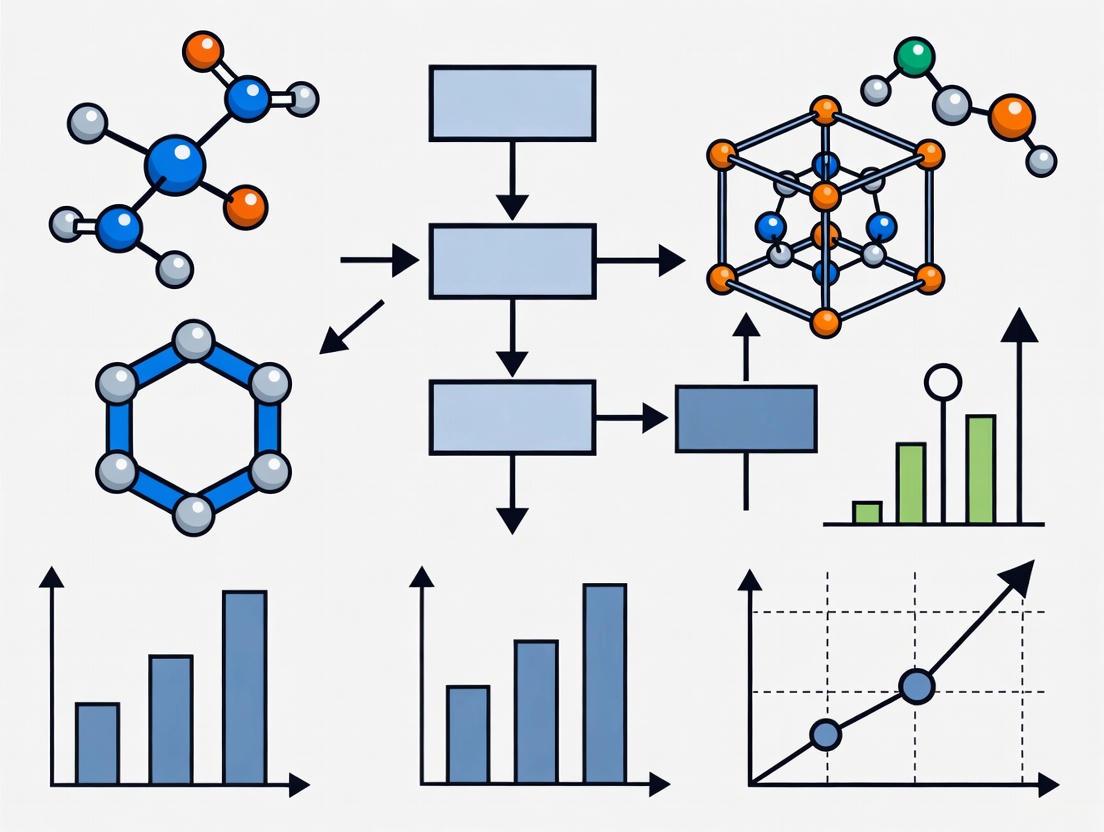

Diagram 1: Multi-modal molecular representation learning architecture for cross-domain feature extraction

Quantitative Benchmarking of Automated Feature Extraction

Recent studies have systematically evaluated the performance of automated feature extraction methods against traditional approaches across diverse chemical tasks. The results demonstrate consistent advantages for automated methods, particularly in cross-domain settings where the test data distribution differs from the training data.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Feature Extraction Methods on Molecular Property Prediction

| Model Architecture | Representation Type | Average RMSE | Cross-Domain Drop | Extraction Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | Manual Descriptors | 0.89 | 42% | Manual |

| Graph Neural Network | Learned Graph Features | 0.63 | 28% | Automated |

| Transformer | Learned Sequence Features | 0.58 | 25% | Automated |

| Multi-Modal Fusion | Hybrid Learned Features | 0.51 | 15% | Automated |

| Cross-Domain GNN | Domain-Invariant Graphs | 0.54 | 9% | Automated |

The benchmarking data reveals several key trends. First, automated feature extraction methods consistently outperform manual descriptor-based approaches across multiple property prediction tasks. Second, models employing automated feature extraction demonstrate significantly better cross-domain generalization, with performance drops of only 9-28% compared to 42% for manual approaches. The multi-modal fusion approach shows particularly strong performance, highlighting the value of integrating multiple molecular representations [1].

Notably, LLM-based AI agents have demonstrated remarkable capability in automated data extraction from scientific literature. In one benchmark evaluating extraction of thermoelectric and structural properties from approximately 10,000 full-text scientific articles, GPT-4.1 achieved extraction accuracies of F1 ≈ 0.91 for thermoelectric properties and F1 ≈ 0.838 for structural fields, while GPT-4.1 Mini offered nearly comparable performance at a fraction of the cost [6]. This demonstrates how automated feature extraction extends beyond molecular design to encompass knowledge mining from the scientific literature.

Methodologies for Cross-Domain Generalization

Language-Guided Feature Remapping

Language-guided feature remapping represents a cutting-edge approach for enhancing cross-domain generalization in molecular representation learning. This method leverages vision-language models (VLMs) like CLIP to augment sample features and improve the generalization performance of regular models [5]. The approach constructs a teacher-student network structure where the teacher network (based on VLMs) provides cross-modal alignment capabilities that guide the student network (a regular-sized model) to learn more robust, domain-invariant features.

The core innovation involves using domain prompts and class prompts to guide sample features to remap into a more generalized and universal feature space. Specifically, domain prompt prototypes based on domain text prompts and class text prompts direct the transformation of local and global features into the desired generalization feature space [5]. Through knowledge distillation from the teacher network to the student network, the domain generalization capability of the student network is significantly enhanced without increasing computational requirements during deployment.

Unified Tokenization for Cross-Domain Alignment

Recent work has introduced unified tokenization strategies that enable effective feature alignment across disparate chemical domains. Rather than relying on ID-based sequence modeling (which lacks semantics) or language-based modeling (which can be verbose), methods like RecBase employ a general item tokenizer that unifies molecular representations across domains [4]. Each molecule is tokenized into multi-level concept IDs, learned in a coarse-to-fine manner inspired by curriculum learning.

This hierarchical encoding facilitates semantic alignment, reduces vocabulary size, and enables effective knowledge transfer across diverse domains. The model is trained using an autoregressive modeling paradigm where it predicts the next token in a sequence, enabling learning of molecular co-relationships within a unified concept token space [4]. This approach has demonstrated strong performance in zero-shot and cross-domain settings, matching or surpassing the performance of LLM baselines up to 7B parameters despite using significantly fewer parameters.

Diagram 2: Cross-domain generalization through language-guided feature remapping

Experimental Protocol for Cross-Domain Evaluation

Robust evaluation of cross-domain generalization requires carefully designed experimental protocols. The following methodology has emerged as a standard for assessing automated feature extraction systems:

Dataset Partitioning: Source domains (\mathcal{S}=\left{ \mathcal{S}1,..., \mathcal{S}M \right}) with M ≥ 1 are used for training, where each source domain (\mathcal{S}i=\left{ \left( xk^i,yk^i \right) \right} _{k=1} ^{n^i} \sim P{XY}^{\left( i\right) }) contains (n^i) training samples. The target domain (\mathcal{T}=\left{ \left( xj \right) \right} _{j=1} ^{n^{M+1}} \sim P{XY}^t) remains unlabeled and unseen during training [7].

Distribution Shift Enforcement: Joint probability distributions are explicitly different across domains: (P{XY}^{\left( i\right) } \ne P{XY}^{\left( j \right) }) for i ≠ j, and between source and target: (P{XY}^t \ne P{XY}^{\left( i \right) }) for i (\in) [1, M] [7].

Evaluation Metrics: Primary metrics include cross-domain performance drop (difference between in-domain and cross-domain performance), zero-shot accuracy (performance without target domain fine-tuning), and few-shot adaptation capability.

Ablation Studies: Systematic removal of components (e.g., language guidance, specific fusion strategies) to isolate their contribution to cross-domain performance.

This protocol ensures rigorous assessment of how well automated feature extraction systems generalize across domain boundaries, which is essential for real-world deployment where chemical data distributions frequently shift.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Implementation

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Automated Feature Extraction in Computational Chemistry

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Domain Generalization Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepMol | AutoML Framework | Automated machine learning for chemical data | Integrated pipeline serialization, supports conventional and deep learning models for regression, classification and multi-task learning [2] |

| RecBase | Foundation Model | Cross-domain recommendation and molecular selection | Unified item tokenizer with hierarchical concept IDs, autoregressive pretraining for zero-shot generalization [4] |

| LGFR | Feature Remapping | Language-guided feature adaptation | Domain prompt prototypes, class text prompts, teacher-student knowledge distillation [5] |

| ChemRL-GNN | Graph Neural Network | Molecular graph representation learning | Geometric learning, 3D-aware representations, physics-informed neural potentials [1] |

| SpectraML | Spectral Analysis | AI-driven spectroscopic data interpretation | Multimodal data fusion, foundation models trained across millions of spectra, explainable AI integration [8] |

Future Frontiers and Research Directions

The field of automated feature extraction in computational chemistry continues to evolve rapidly, with several promising research directions emerging. Physics-informed neural networks represent a significant frontier, combining data-driven feature learning with fundamental physical principles to create more robust and interpretable models [1]. These networks incorporate domain knowledge through physical constraints, preserving real spectral and chemical constraints while maintaining the representational power of deep learning.

Multi-modal foundation models trained on massive-scale chemical data represent another promising direction. These models aim to create universal molecular representations that transfer seamlessly across diverse chemical domains and tasks [3]. By pretraining on extensive datasets encompassing molecules, materials, and their associated properties, these foundation models capture fundamental chemical principles that enable strong performance on downstream tasks with minimal fine-tuning.

The integration of AI with quantum computing and hybrid AI-quantum frameworks shows particular promise for tackling previously intractable problems in computational chemistry [9]. These approaches leverage quantum processing to enhance feature extraction for complex electronic structure problems, potentially revolutionizing our ability to predict and design molecular properties with quantum accuracy.

As these technologies mature, the paradigm of automated feature extraction will continue to displace manual approaches, accelerating the discovery of novel materials and therapeutic compounds while enhancing our fundamental understanding of chemical space across domains.

The automation of feature extraction represents a fundamental paradigm shift in computational chemistry, moving the field from reliance on manually engineered descriptors toward learned representations that capture complex chemical patterns directly from data. This transition has dramatically improved predictive performance while enabling unprecedented cross-domain generalization—the ability of models to maintain performance when applied to new chemical domains with different data distributions.

Architectures such as graph neural networks, transformers, and multi-modal fusion models have proven particularly effective for automated feature extraction, each offering unique advantages for capturing different aspects of molecular structure and properties. When combined with cross-domain generalization techniques like language-guided feature remapping and unified tokenization strategies, these approaches enable knowledge transfer across disparate chemical domains, reducing data requirements and accelerating discovery.

As automated feature extraction continues to mature, it will increasingly serve as the foundation for generative molecular design, autonomous discovery systems, and cross-domain predictive modeling. The researchers and drug development professionals who master these automated approaches will be positioned to lead the next wave of innovation in computational chemistry and materials science.

Molecular representation serves as the foundational bridge between chemical structures and their computational analysis in modern drug discovery and materials science. These representations translate molecular structures into mathematical or computational formats that algorithms can process to model, analyze, and predict molecular behavior. Effective molecular representation is essential for various tasks including virtual screening, activity prediction, and scaffold hopping, enabling efficient navigation of the vast chemical space estimated to contain over 10^60 molecules [10] [11].

Traditional representation methods, primarily Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) and molecular fingerprints, have established themselves as indispensable tools in cheminformatics over recent decades. Despite their widespread adoption, these representations exhibit inherent limitations that impact their performance in predictive modeling and generative tasks. This technical review examines the fundamental principles, applications, and constraints of these traditional approaches, with particular emphasis on their implications for cross-domain generalization in generative material models research.

SMILES: Syntax and Capabilities

The Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) represents a specification for describing chemical structures using short ASCII strings. Developed by Weininger et al. in 1988, SMILES provides a linearized representation of molecular graphs, functioning conceptually as a depth-first traversal of the molecular structure [12] [11].

Core Syntax Principles

The SMILES notation system employs a relatively simple yet powerful syntax to encode molecular structures:

- Atomic Representation: Standard atomic symbols represent atoms, with elements outside the organic subset (B, C, N, O, P, S, F, Cl, Br, I) enclosed in brackets (e.g.,

[Pt]for platinum). Hydrogen atoms are typically implied rather than explicitly stated [12]. - Bond Encoding: Single bonds (

-) are usually omitted, while double (=), triple (#), and aromatic bonds (:) are explicitly denoted. Delocalized bonds are represented with a period (.) [12]. - Branching: Parentheses encapsulate branched structures, allowing nested representations (e.g.,

C(C)Cfor propane) [12]. - Cyclic Structures: Ring systems are encoded by breaking one bond and assigning matching numbers to the connected atoms (e.g.,

c1ccccc1for benzene) [12]. - Stereochemistry: Isomeric configurations are specified using

/and\symbols for double bond stereochemistry and@/@@for tetrahedral chirality [12].

Variants and Standardization

Several SMILES variants have emerged to address specific application needs:

- Canonical SMILES: Generates unique string representations for molecules to ensure consistency across different software implementations [12].

- Isomeric SMILES: Incorporates stereochemical and isotopic information for more precise molecular representation [12].

- TokenSMILES: A recently developed grammatical framework that standardizes SMILES into structured sentences composed of context-free words through five syntactic constraints, significantly reducing redundant enumerations while maintaining valence compliance [13].

Table 1: SMILES Notation Examples and Corresponding Structures

| SMILES String | Molecular Structure | Description |

|---|---|---|

CCO |

Ethanol | Linear alcohol |

CN1C=NC2=C1C(=O)N(C(=O)N2C)C |

Caffeine | Complex heterocycle |

C/C=C/C |

(Z)-2-butene | Cis configuration |

C/C=C\C |

(E)-2-butene | Trans configuration |

N[C@](C)(F)C(=O)O |

S-configured amino acid | Tetrahedral chirality |

Molecular Fingerprints: Encoding Structural Features

Molecular fingerprints provide an alternative representation that encodes molecular structures as fixed-length bit strings, where each bit indicates the presence or absence of particular substructures or chemical features. These representations enable rapid similarity comparisons and are widely employed in virtual screening and machine learning applications [11] [14].

Fingerprint Generation and Types

The most widely used fingerprint implementation is the Extended-Connectivity Fingerprint (ECFP), which iteratively captures and hashes local atomic environments up to a specified radius to generate a fixed-length vector [15] [11]. ECFP generation follows a circular neighborhood approach:

- Initialization: Each atom is assigned an initial identifier based on its atomic number, degree, and other atomic properties.

- Iterative Update: For each iteration (radius), identifiers are updated by combining information from neighboring atoms.

- Hashing and Folding: The resulting identifiers are hashed to a fixed-length bit string, with multiple identifiers potentially mapping to the same bit (folded representation).

Table 2: Major Molecular Fingerprint Types and Their Characteristics

| Fingerprint Type | Representation | Key Features | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extended-Connectivity (ECFP) | Hashed circular substructures | Radius-dependent atom environments, not predefined | Similarity searching, QSAR, machine learning |

| MACCS | Predefined structural keys | 166 or 960 structural fragments | Rapid similarity screening |

| Avalon | Combined approach | Predefined and hashed substructures | Similarity searching, QSAR |

| Klekota-Roth | Predefined structural keys | 4860 chemical substructures | Bioactivity prediction |

| Molecular signatures | Atomic environment collection | Local subgraphs up to radius r | Exhaustive enumeration, inverse QSAR |

Applications in Cheminformatics

Fingerprints have demonstrated exceptional utility in various computational chemistry applications:

- Similarity Assessment: Tanimoto coefficient and other similarity metrics operating on fingerprint vectors enable rapid molecular similarity calculations [11].

- Machine Learning: Fingerprints serve as feature vectors for predictive modeling of molecular properties, toxicity, and biological activity [16] [11].

- Reverse Engineering: Recent advances have demonstrated the feasibility of reconstructing molecular structures from fingerprints, challenging previous assumptions about their non-invertibility [15].

Limitations of Traditional Representations

Despite their widespread adoption and computational efficiency, traditional molecular representations exhibit significant limitations that impact their performance in modern drug discovery applications, particularly in cross-domain generalization tasks.

SMILES Limitations

Non-Uniqueness and Redundancy

A fundamental limitation of SMILES notation is its non-uniqueness, where multiple distinct strings can represent the same molecular structure. This redundancy arises from different traversal orders of the molecular graph and variations in ring-opening positions. For example, benzene can be validly represented as c1ccccc1, C1=CC=CC=C1, and numerous other variants [12] [13]. This lack of bijective mapping introduces noise in machine learning applications and complicates model interpretation.

Validity and Robustness Issues

Chemical language models trained on SMILES representations invariably generate invalid strings that do not correspond to chemically plausible structures. This perceived limitation has motivated extensive research into alternative representations and correction mechanisms [10]. Counterintuitively, recent evidence suggests that the ability to produce invalid outputs may actually benefit chemical language models by providing a self-corrective mechanism that filters low-likelihood samples. Invalid SMILES are sampled with significantly lower likelihoods than valid SMILES, suggesting their removal functions as an intrinsic quality filter [10].

Structural Information Loss

As a one-dimensional representation, SMILES strings cannot encode three-dimensional structural information, conformational dynamics, or molecular geometry—critical factors influencing molecular properties and biological activity [12] [11]. Additionally, while SMILES can represent stereochemistry, this information is often lost in canonicalization processes unless explicitly preserved using isomeric SMILES.

Tautomeric and Protonation Ambiguity

Different tautomeric forms and protonation states of the same fundamental chemical species yield entirely different SMILES strings, with no inherent indication of their relationship. This poses significant challenges for modeling solution-phase properties where specific tautomers or protonation states predominate [17]. Identifying the predominant microstate at physiological conditions requires additional computational workflows, such as macroscopic pKa prediction [17].

Fingerprint Limitations

Information Loss in Vectorization

The fingerprint vectorization process constitutes a lossy compression of structural information, particularly for folded fingerprints where multiple structural features map to the same bit. This hashing collisions result in decreased resolution and potential loss of critical structural details [15].

Predefined Feature Bias

Structural key fingerprints (e.g., MACCS) rely on predefined molecular fragments, introducing a bias toward known chemical motifs and potentially limiting their ability to represent novel structural classes outside their design scope [11].

Limited Chemical Interpretability

While fingerprints efficiently encode structural patterns for similarity searching, their bit representations generally lack direct chemical interpretability. Understanding which specific structural features contribute to particular bits or activity predictions requires additional analysis steps [16].

Challenges in Generative Applications

The fixed-length, bit-level representation of fingerprints presents significant challenges for their direct use in generative models, as small changes in the bit vector do not necessarily correspond to semantically meaningful molecular modifications [15].

Experimental Analysis: Performance and Limitations

SMILES vs. SELFIES in Chemical Language Models

Recent experimental investigations have provided quantitative comparisons between SMILES and alternative representations like SELFIES (SELF-referencIng Embedded Strings), which guarantees 100% validity by design [10].

Experimental Protocol:

- Training Data: Models trained on random samples from ChEMBL database [10]

- Model Architecture: Language models based on LSTM or Transformer architectures [10]

- Evaluation Metrics: Fréchet ChemNet distance, Murcko scaffold similarity, validity rate, novelty rate [10]

- Comparison Method: Parallel training on SMILES and SELFIES representations of identical molecular sets [10]

Key Findings:

- Models trained on SELFIES achieved 100% validity versus 90.2% for SMILES-based models [10]

- Despite lower validity rates, SMILES-based models generated novel molecules that better matched training set distributions according to Fréchet ChemNet distance [10]

- The performance advantage of SMILES models was negatively correlated with validity rate (r = -0.87, p < 0.001) [10]

- Invalid SMILES exhibited significantly higher perceptual losses than valid SMILES across all error categories (p < 0.0001 for all comparisons) [10]

Diagram 1: Invalid SMILES as Self-Corrective Mechanism in Chemical Language Models

Fingerprint Inversion and Structural Reconstruction

Recent advances have challenged the long-standing assumption that molecular fingerprints are non-invertible. A deterministic enumeration algorithm has demonstrated complete molecular reconstruction from ECFP vectors given appropriate alphabet and threshold settings [15].

Experimental Protocol:

- Datasets: MetaNetX (natural compounds) and eMolecules (commercial chemicals) [15]

- Fingerprint Parameters: ECFP with radius 2, 2048 bits [15]

- Reconstruction Method: Two-step approach combining signature-enumeration and molecule-enumeration algorithms [15]

- Comparison: Transformer-based generative model trained to predict SMILES from ECFP [15]

Key Findings:

- Deterministic algorithm achieved near-complete molecular reconstruction from ECFP [15]

- Alphabet representativity crucial—plateau in new atomic signatures observed after ~1 million molecules for radius 2 [15]

- Transformer model achieved 95.64% top-ranked retrieval accuracy but struggled with exhaustive enumeration [15]

- Reconstruction success rate decreased with increasing molecular complexity and fingerprint radius [15]

Diagram 2: Deterministic Fingerprint Inversion Workflow

Cross-Domain Generalization Implications

The limitations of traditional molecular representations present particular challenges for cross-domain generalization in generative material models research. Cross-domain graph learning aims to transfer knowledge across structurally diverse domains—such as from organic molecules to inorganic materials—by identifying universal patterns in molecular representations [18].

Structural and Feature Disparities

Cross-domain generalization faces fundamental challenges due to:

- Structural Differences: Molecular graphs vary significantly in connectivity patterns, size, and complexity compared to other graph types (e.g., social networks, citation networks) [18].

- Feature Disparities: Node features in molecular graphs (atom types, hybridization) differ dimensionally and semantically from features in other domains (e.g., text embeddings in citation networks) [18].

- Representational Gaps: The syntax and constraints of SMILES strings create domain-specific patterns that do not transfer readily to other structured data domains [10] [18].

Impact on Foundation Models

The development of true graph foundation models requires representations that capture transferable knowledge across domains. Traditional molecular representations present specific obstacles:

- SMILES Syntax Constraints: The grammatical rules of SMILES are specific to molecular structures and do not generalize to other graph-structured data [13].

- Fingerprint Specificity: Molecular fingerprints encode chemical domain knowledge that may not align with feature representations in other domains [15] [18].

- Valency Limitations: Representations that enforce chemical validity (e.g., SELFIES) introduce structural biases that impair distribution learning and limit generalization to unseen chemical space [10].

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Molecular Representation Research

| Tool/Platform | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics toolkit | SMILES parsing, fingerprint generation, molecular manipulation |

| SIRIUS | MS/MS data analysis | Fragmentation tree computation for fingerprint prediction [14] |

| Rowan pKa Workflow | Microstate prediction | Tautomer and protonation state standardization for SMILES [17] |

| SmilX | TokenSMILES implementation | Grammar-based SMILES standardization [13] |

| Graph Attention Networks (GAT) | Graph neural networks | Molecular fingerprint prediction from fragmentation data [14] |

| Transformer Architectures | Sequence modeling | SMILES generation from molecular fingerprints [15] |

Traditional molecular representations, particularly SMILES and fingerprints, have established themselves as fundamental tools in computational chemistry and drug discovery. Their computational efficiency, interpretability, and well-established workflows continue to make them valuable for many applications. However, their limitations—including non-uniqueness, information loss, validity issues, and domain specificity—present significant challenges for next-generation generative models and cross-domain applications.

Recent research suggests that some perceived limitations, such as invalid SMILES generation, may actually provide beneficial filtering mechanisms rather than representing pure deficits. Nevertheless, the development of more robust, expressive molecular representations remains crucial for advancing cross-domain generalization in generative material models. Future directions likely include hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of traditional representations with modern graph-based and geometric learning techniques, ultimately enabling more effective knowledge transfer across diverse chemical and material domains.

In computational chemistry and materials science, the representation of a molecular structure serves as the foundational step for any predictive or generative model. Graph-based representations have emerged as a paradigm shift from traditional descriptors by explicitly encoding atoms as nodes and bonds as edges, thus directly mirroring the physical reality of molecular structures [19]. This approach allows deep learning models, particularly Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), to learn directly from the intrinsic connectivity of molecules, capturing complex patterns that are essential for predicting molecular properties, designing novel compounds, and understanding chemical interactions [19] [20]. Within the context of cross-domain generalization in generative material models, graph-based representations provide a universal and transferable schema for encoding molecular information, enabling models to learn fundamental chemical principles that extend beyond the confines of a single dataset or application domain [19] [21]. Their inductive bias towards atomic connectivity makes them particularly powerful for tasks such as drug-target interaction prediction and de novo molecular design, where generalizing to unseen compounds or proteins is a critical challenge [22] [21].

Core Principles and Methodologies

Fundamentals of Molecular Graphs

A molecular graph ( G = (V, E) ) formally represents a molecule, where ( V ) is the set of nodes (atoms) and ( E ) is the set of edges (bonds) [19]. This structure explicitly captures the topology and connectivity of the molecule, providing a natural framework for computational analysis.

- Node Features: Each atom node is typically encoded with features such as atom type, hybridization state, formal charge, and number of attached hydrogens [19] [20].

- Edge Features: Bonds are represented with features including bond type (single, double, triple), conjugation, and stereochemistry [19].

- Spatial Geometry: Advanced representations incorporate 3D spatial coordinates of atoms, evolving from static 2D connectivity to capture conformational dynamics and quantum mechanical properties [19].

Comparison with Alternative Representations

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Molecular Representation Paradigms

| Representation Type | Data Structure | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation | Domain Generalization Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graph-Based | Node and Edge Lists | Explicitly encodes structural relationships | Computational intensity for large molecules | High (structure-aware bias) [19] [21] |

| String-Based (SMILES) | Linear String | Compact, human-readable | Ambiguous; poor error tolerance | Low (sensitive to syntax) [19] |

| Molecular Fingerprints | Bit Vector | Fast similarity search | Loss of structural detail | Medium (dependent on design) [19] |

| 3D Density Fields | Volumetric Grid | Captures electronic structure | Very high computational cost | High (physics-aware) [19] |

Experimental Protocol for Graph Construction

The standard methodology for converting a chemical structure into a computational graph involves a multi-step, reproducible protocol [19] [22]:

- Input Parsing: Begin with a molecular structure file (e.g., SDF, MOL2) or a SMILES string. Using a cheminformatics toolkit (e.g., RDKit), parse the input to extract all atoms and bonds.

- Node Identification: For each atom, create a corresponding graph node.

- Node Feature Assignment: For each node, compute a feature vector. Standard features include:

- Atom type (as one-hot encoding: C, N, O, etc.)

- Atomic number

- Degree of connectivity

- Formal charge

- Hybridization state (sp, sp², sp³)

- Aromaticity indicator

- Edge Creation: For every chemical bond between atoms, create an undirected or directed edge in the graph.

- Edge Feature Assignment: For each edge, compute a feature vector. Standard features include:

- Bond type (single, double, triple, aromatic)

- Bond stereochemistry

- Conjugation

- Presence in a ring

This structured protocol ensures that the resulting graph is a faithful and information-rich representation of the molecular structure, suitable for downstream machine-learning tasks.

Advanced Architectures and Cross-Domain Applications

Graph Neural Network Architectures

GNNs operate on the principle of message passing, where nodes iteratively aggregate information from their local neighbors to build increasingly sophisticated representations [19] [20].

- Message Passing: In each layer, a node's representation is updated by combining its current state with the aggregated states of its neighboring nodes [20]. This process can be summarized as: [ hv^{(l+1)} = \text{UPDATE}\left(hv^{(l)}, \text{AGGREGATE}\left({hu^{(l)}, \forall u \in \mathcal{N}(v)}\right)\right) ] where ( hv^{(l)} ) is the representation of node ( v ) at layer ( l ), and ( \mathcal{N}(v) ) is the set of its neighbors [19].

- Graph-Level Readout: After several message-passing layers, a readout function generates a single representation for the entire graph, which is used for property prediction [20]. Common methods include global pooling or attention-based aggregation.

Application in Drug-Target Interaction (DTI) Prediction

Graph-based representations are pivotal in overcoming the cross-domain generalization and cold-start problems in DTI prediction, where models must predict interactions for novel drugs or targets unseen during training [22] [21].

The CDI-DTI framework leverages multi-modal features—textual, structural, and functional—through a multi-strategy fusion approach [22]. Its key innovation is a balanced fusion strategy:

- Early Fusion: A multi-source cross-attention mechanism aligns and fuses different modalities of a single entity (drug or protein) to create a unified representation.

- Late Fusion: A deep orthogonal fusion module combines predictions from different modalities, using orthogonality constraints to minimize feature redundancy [22].

The GraphBAN framework employs a knowledge distillation architecture with a teacher-student model to handle inductive predictions for entirely unseen compounds and proteins [21]. It incorporates a Conditional Domain Adversarial Network (CDAN) module to improve performance across different dataset domains by managing disparate data distributions between source and target domains [21].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Graph-Based Models in Cross-Domain DTI Prediction

| Model | Architecture | BindingDB (AUROC) | BioSNAP (AUROC) | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GraphBAN [21] | GNN + Knowledge Distillation + CDAN | 0.914 (Baseline: 0.867) | 0.901 (Baseline: 0.824) | Inductive link prediction for unseen entities |

| CDI-DTI [22] | Multi-modal Fusion + Orthogonal Loss | State-of-the-art on BindingDB & DAVIS | Not Reported | Multi-strategy fusion for cross-domain tasks |

| DrugBAN [21] | Bilinear Attention Network | 0.867 | 0.824 | Bilinear attention for interaction modeling |

| GraphDTA [21] | Graph Neural Network | 0.849 (on PDBbind 2016) | 0.861 | Simple GNN using molecular graphs |

Application in De Novo Molecular Design

Generative graph-based models have significantly advanced de novo molecular design by directly operating on the graph structure [19] [20]. These models, including Graph Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), learn a continuous latent space of molecular graphs. This enables the generation of novel, valid molecular structures with optimized properties, a process crucial for lead compound discovery in drug development [19] [20]. The explicit encoding of structure allows these models to incorporate synthetic accessibility constraints directly into the generation process.

Visualization of Workflows and Architectures

Molecular Graph Construction Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the standard protocol for converting a molecular structure into a featurized computational graph.

Graph Neural Network Message Passing

This diagram depicts the core message-passing mechanism of a GNN, where node representations are updated by aggregating information from their neighbors.

Cross-Domain DTI Prediction Architecture (GraphBAN)

This diagram outlines the architecture of GraphBAN, showcasing its knowledge distillation and domain adaptation components for cross-domain prediction.

Table 3: Key Software Tools and Datasets for Graph-Based Molecular Modeling

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Molecular graph construction & manipulation | Extracts atoms, bonds, and features from SMILES/MOL files for graph creation [19] |

| NetworkX | Graph Analysis Library | Graph structure creation and analysis | Prototypes graph algorithms and analyzes topological properties of molecular networks [23] [24] |

| PyTorch Geometric | Deep Learning Library | Implements Graph Neural Networks | Provides efficient, batched GNN layers (e.g., GCN, GAT) for property prediction [19] |

| ChemBERTa [21] | Pre-trained Language Model | Generates contextual embeddings from SMILES | Provides textual feature embeddings for multi-modal molecular representation [22] [21] |

| ESM (Evolutionary Scale Modeling) [21] | Pre-trained Protein Language Model | Generates protein sequence embeddings | Provides protein feature representations for drug-target interaction tasks [21] |

| BindingDB [22] [21] | Benchmark Dataset | Curated drug-target binding data | Serves as a standard benchmark for training and evaluating DTI prediction models [22] |

| DAVIS [22] | Benchmark Dataset | Kinase inhibitor-target binding affinities | Provides another high-quality benchmark for validating model performance [22] |

Graph-based representations, by explicitly encoding atomic connectivity, provide an indispensable foundation for modern computational chemistry and drug discovery. Their structural fidelity enables models to learn fundamental chemical principles, which is the cornerstone of effective cross-domain generalization. Advanced frameworks like CDI-DTI and GraphBAN demonstrate that integrating these representations with multi-modal data and domain adaptation techniques powerfully addresses long-standing challenges such as cold-start prediction and extrapolation to novel chemical spaces. As the field evolves, the integration of 3D geometric learning and self-supervised pre-training on graph structures promises to further enhance the robustness and generalizability of generative models, solidifying the role of graph-based representations as a critical enabler for accelerated scientific discovery.

Molecular representation learning has catalyzed a paradigm shift in computational chemistry and materials science, moving from reliance on manually engineered descriptors to the automated extraction of features using deep learning. This transition enables data-driven predictions of molecular properties, inverse design of compounds, and accelerated discovery of chemical and crystalline materials [19]. While early representations utilized simplified one-dimensional (1D) strings or two-dimensional (2D) topological graphs, these approaches fail to capture the rich spatial information contained in molecular three-dimensional (3D) geometry, which fundamentally determines physicochemical properties and biological activities [25] [19].

The incorporation of 3D geometric information represents a frontier in molecular machine learning, with geometric learning approaches demonstrating exceptional performance in predicting molecular properties, understanding interaction dynamics, and designing novel compounds [19]. From a life sciences perspective, molecular properties and drug bioactivities are fundamentally determined by their 3D conformations [25]. This technical guide explores the core methodologies, experimental protocols, and applications of 3D-aware geometric learning, framed within the context of cross-domain generalization in generative material models research.

Core Methodological Frameworks in 3D Geometric Learning

Contrastive Pre-training for Molecular Relational Learning

The 3D Interaction Geometric Pre-training for Molecular Relational Learning (3DMRL) framework addresses the critical challenge of understanding interaction dynamics between molecules, which is essential for applications ranging from catalyst engineering to drug discovery [26]. Traditional approaches have been limited to using only 2D topological structures due to the prohibitive cost of obtaining 3D interaction geometry. 3DMRL introduces a novel pre-training strategy that incorporates a 3D virtual interaction environment, overcoming the limitations of costly quantum mechanical calculations [26].

The framework operates through two principal pre-training strategies. First, it trains a 2D Molecular Relational Learning (MRL) model to produce representations that are globally aligned with those of the 3D virtual interaction environment via contrastive learning. Second, the model is trained to predict localized relative geometry between molecules within this virtual interaction environment, enabling the learning of fine-grained atom-level interactions [26]. This approach allows the model to understand the nature of molecular interactions without requiring explicit 3D data during downstream tasks, facilitating positive transfer to various MRL applications.

Efficient 3D Convolutional Networks

Voxel-based 3D convolutional neural networks (3D CNNs) have gained attention in molecular representation learning research due to their ability to directly process voxelized 3D molecular data [25]. However, these methods often suffer from severe computational inefficiencies caused by the inherent sparsity of voxel data, resulting in numerous redundant operations. The Prop3D model addresses these challenges through a kernel decomposition strategy that significantly reduces computational cost while maintaining high predictive accuracy [25].

Prop3D employs three core modules for efficient molecular feature learning. The model first encodes molecular structures into regularized 3D grid data based on their 3D coordinate information, preserving spatial geometric features. A standard 3D CNN then performs channel expansion and information fusion on the input 3D grid data. Inspired by the InceptionNeXt design, large convolution kernels are decomposed in 3D space to balance efficiency and computational resource consumption [25]. Additionally, a channel and spatial attention mechanism (CBAM) is integrated after each convolutional module to focus on key features and improve generalization capability.

Equivariant Graph Neural Networks for Molecular Generation

Equivariant graph neural networks have emerged as powerful architectures for 3D molecular generation, particularly for designing high-affinity molecules for specific protein targets [27]. The DMDiff framework exemplifies this approach, employing a diffusion model based on SE(3)-equivariant graph neural networks to enhance generated molecular binding affinity using long-range and distance-aware attention mechanisms [27].

This approach incorporates a molecular geometry feature enhancement strategy that strengthens the perception of the spatial size of ligand molecules. The fundamental innovation lies in its distance-aware mixed attention (DMA) geometric neural network, which combines long-range and distance-aware attention heads. The long-range attention captures dependencies between distant atoms, while the distance-aware attention focuses on short-range interactions, with Euclidean distances dynamically adjusting attention weights [27].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of 3D Geometric Learning Models

| Model | Architecture | Key Innovation | Reported Performance | Application Domain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3DMRL [26] | Contrastive Pre-training | Virtual interaction environment | Up to 24.93% improvement across 40 tasks | Molecular relational learning |

| Prop3D [25] | 3D CNN | Kernel decomposition strategy | Consistently outperforms SOTA methods | Molecular property prediction |

| GEO-BERT [28] | Transformer | Atom-atom, bond-bond, atom-bond positional relationships | Optimal performance across multiple benchmarks | Drug discovery |

| DMDiff [27] | Equivariant GNN | Distance-aware mixed attention | Median docking score: -10.01 (Vina Score) | Structure-based drug design |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

3DMRL Pre-training Protocol

The 3DMRL framework employs a systematic pre-training approach to capture molecular interaction dynamics. The experimental workflow begins with the construction of a virtual interaction environment from 3D conformer pairs. For each pair of 3D molecular conformations (g₃D¹, g₃D²), a virtual interaction geometry (g_vr) is derived to simulate real molecular interactions [26].

The pre-training consists of two parallel objectives. The global alignment objective uses contrastive learning to align 2D molecular representations with the 3D virtual interaction environment representations. Simultaneously, the local geometry prediction objective trains the model to predict relative spatial relationships between atoms in the interaction environment. This dual approach enables the model to capture both macroscopic interaction patterns and atomic-level spatial dependencies [26].

The downstream implementation involves transferring the pre-trained 2D molecular encoders (f₂D¹ and f₂D²) to various molecular relational learning tasks, including solvation-free energy prediction, chromophore-solute interactions, and drug-drug interactions, without requiring 3D data during inference.

Prop3D 3D CNN Implementation

The Prop3D model implements an efficient 3D convolutional architecture for molecular property prediction. The experimental protocol begins with molecular data preprocessing, where molecular structures are encoded into regularized 3D grid data based on atomic coordinate information. Each atom is mapped onto grid units within a 3D voxel space, preserving spatial geometric features [25].

The architecture employs a kernel decomposition strategy where large convolution kernels are decomposed to reduce computational complexity. Specifically, the model adapts the channel-wise decomposition approach from InceptionNeXt, splitting large-kernel convolution into four parallel branches: a small square kernel, two orthogonal strip-shaped large kernels, and an identity mapping [25]. This design significantly reduces computational costs while maintaining receptive field size.

Following each convolutional module, the model integrates a Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) that sequentially applies channel and spatial attention mechanisms. This attention mechanism enhances feature discriminability by emphasizing important channels and spatial regions while suppressing less useful ones [25]. The model is trained end-to-end using standard backpropagation with task-specific loss functions.

Table 2: Computational Efficiency Comparison of 3D Molecular Models

| Model Type | Computational Complexity | Memory Requirements | Key Optimization | Suitable Deployment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard 3D CNN [25] | High | High | None | High-performance computing |

| Voxel with Smoothing [25] | Medium-High | Medium-High | Wavelet transform sparsity reduction | Research servers |

| Prop3D [25] | Medium | Medium | Kernel decomposition | Standard research workstations |

| Geometric GNN [27] | Medium-Low | Medium | Distance-aware attention | Cloud and local deployment |

DMDiff Equivariant Generation Protocol

The DMDiff framework implements a diffusion-based approach for 3D molecular generation targeting specific protein pockets. The experimental protocol consists of a forward diffusion process and a reverse generation process, both defined as Markov chains [27].

The diffusion process progressively injects noise into molecular data following a predetermined schedule. Starting from initial molecular coordinates x₀, the forward process produces increasingly noisy versions x₁, x₂, ..., x_T through Gaussian noise addition. The reverse process trains a neural network to denoise these molecular structures, effectively learning the data distribution [27].

The core innovation lies in the Distance-aware Mixed Attention (DMA) geometric neural network used for denoising. This network employs 3D equivariant graph attention message passing that updates both atomic hidden embeddings and coordinates based on spatial relationships. The mixed attention strategy concatenates representations from long-range and distance-aware attention heads, which are then passed through a linear layer to produce updated atomic features and coordinate features [27].

The molecular geometry enhancement component abstracts molecules into rectangular cuboid geometries, enabling the model to learn spatial volume characteristics that correlate with binding affinity. This allows the model to generate molecules with appropriate sizes for specific protein pockets, improving binding compatibility.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for 3D Geometric Learning

| Resource | Type | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3D Molecular Datasets [26] [25] | Data | Provide ground truth 3D structures for training and evaluation | Pre-training, benchmark evaluation |

| Quantum Chemistry Software [26] | Computational Tool | Generate accurate 3D geometries and interaction energies | Creating virtual interaction environments |

| Voxelization Tools [25] | Preprocessing | Convert 3D molecular coordinates into regular 3D grids | Preparing input for 3D CNN models |

| Geometric Deep Learning Libraries [27] | Software Framework | Implement equivariant operations and graph attention mechanisms | Building SE(3)-equivariant models |

| Molecular Docking Software [27] | Validation Tool | Evaluate binding affinity of generated molecules | Assessing DMDiff output quality |

| Diffusion Model Implementations [27] | Algorithmic Framework | Provide denoising networks for molecular generation | Implementing reverse diffusion process |

Cross-Domain Generalization and Future Frontiers

The advancements in 3D-aware geometric learning demonstrate significant potential for cross-domain generalization across materials science, drug discovery, and catalytic engineering. The virtual interaction environment concept from 3DMRL [26] can be extended to model solid-state interactions in crystalline materials, while the efficient 3D convolutional approaches from Prop3D [25] offer promising pathways for analyzing porous materials and metal-organic frameworks.

Emerging research directions include the development of more sophisticated physics-informed neural potentials that incorporate physical laws directly into the learning objective, enhancing model interpretability and physical consistency [19]. Additionally, multi-modal fusion strategies that integrate graphs, sequences, and quantum descriptors are showing promise for creating more comprehensive molecular representations that transfer across domains [19]. As geometric learning methodologies continue to mature, their ability to capture universal spatial principles positions them as foundational technologies for accelerating discovery across the molecular sciences.

Molecular representation learning has catalyzed a fundamental paradigm shift in computational chemistry and materials science, moving the field from a reliance on manually engineered descriptors toward the automated extraction of informative features using deep learning [19]. This transition enables data-driven predictions of molecular properties, inverse design of compounds, and accelerated discovery of chemical and crystalline materials, with profound implications for drug development, organic molecule design, inorganic solids, and catalytic systems [19]. Within this broader context, self-supervised learning (SSL) has emerged as a particularly powerful framework for leveraging the vast quantities of unlabeled molecular data that exist in scientific repositories, effectively addressing the critical bottleneck of limited annotated datasets [29] [19].

The core premise of SSL involves pretraining deep neural networks on 'pretext tasks' that do not require ground-truth labels or annotations, allowing for efficient representation learning from massive amounts of unlabeled data [30]. This pretraining phase leads to the emergence of rich, general-purpose molecular representations that can subsequently be fine-tuned for specific 'downstream tasks' through supervised transfer learning, often achieving state-of-the-art performance across diverse applications [29] [30]. Particularly for specialized domain-specific applications where assembling massive labeled datasets may be impractical or computationally infeasible, SSL offers a robust methodological alternative that can outperform large-scale pretraining on general datasets [30]. This approach has demonstrated remarkable potential for cross-domain generalization within generative material models research, enabling more precise and predictive molecular modeling that transcends traditional chemical boundaries [19].

SSL Methodologies for Molecular Data: Architectures and Pretext Tasks

The architectural landscape for SSL in molecular applications encompasses diverse neural network designs, each tailored to specific data modalities and learning objectives. Transformer-based neural networks have recently demonstrated remarkable success when pretrained in a self-supervised manner on millions of unannotated tandem mass spectra (MS/MS) [29]. These models typically employ BERT-style masked modeling approaches, where each molecular spectrum is represented as a set of two-dimensional continuous tokens associated with pairs of peak mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) and intensity values [29]. During pretraining, a fraction (typically 30%) of random m/z ratios are masked from each spectrum, sampled proportionally to their corresponding intensities, and the model is trained to reconstruct these masked peaks [29]. This approach forces the network to develop a comprehensive understanding of spectral patterns and molecular fragmentation characteristics without requiring annotated examples.

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) constitute another prominent architectural family for molecular SSL, particularly well-suited for encoding molecular structures as graphs where atoms represent nodes and bonds represent edges [19]. These networks can be pretrained using various SSL strategies including node masking, edge prediction, and context prediction [19]. More recently, 3D-aware GNNs have extended these capabilities by incorporating spatial molecular geometry through equivariant models and learned potential energy surfaces, offering physically consistent, geometry-aware embeddings that extend beyond static graphs [19]. The innovative 3D Infomax approach exemplifies this trend, utilizing 3D geometries to enhance the predictive performance of GNNs by pretraining on existing 3D molecular datasets [19].

Hybrid self-supervised learning frameworks represent the cutting edge of molecular representation learning, integrating the strengths of diverse learning paradigms and data modalities [19]. By combining inputs such as molecular graphs, SMILES strings, quantum mechanical properties, and biological activities, these frameworks generate more comprehensive and nuanced molecular representations [19]. Early advancements such as MolFusion's multi-modal fusion and SMICLR's integration of structural and sequential data highlight the promise of these models in capturing complex molecular interactions that transcend single-modality approaches [19].

Table 1: Common SSL Pretext Tasks for Molecular Data

| Pretext Task Category | Specific Implementation | Molecular Data Type | Learning Objective |

|---|---|---|---|

| Masked Modeling | Peak reconstruction in MS/MS spectra | Tandem mass spectra | Predict masked spectral peaks based on surrounding context [29] |

| Contrastive Learning | Molecular similarity estimation | Molecular graphs or SMILES | Learn embeddings where similar molecules have similar representations [19] |

| 3D Geometry Learning | Spatial relationship prediction | 3D molecular structures | Capture spatial geometry and conformational behavior [19] |

| Multi-modal Alignment | Cross-modal consistency | Multiple representations (graphs, sequences, etc.) | Align representations across different molecular modalities [19] |

The DreaMS Framework: A Case Study in Large-Scale Molecular SSL

Dataset Curation: The GeMS Collection

The development of the DreaMS (Deep Representations Empowering the Annotation of Mass Spectra) framework exemplifies the transformative potential of self-supervised learning applied to molecular data at repository scale [29]. A fundamental challenge in this domain has been the absence of large standardized datasets of mass spectra suitable for unsupervised or self-supervised deep learning [29]. To address this limitation, researchers mined the MassIVE GNPS repository to establish the GNPS Experimental Mass Spectra (GeMS) dataset—a comprehensive collection comprising hundreds of millions of experimental MS/MS spectra [29]. The dataset curation pipeline involved multiple sophisticated steps: initially collecting 250,000 LC–MS/MS experiments from diverse biological and environmental studies; extracting approximately 700 million MS/MS spectra; implementing a quality control pipeline to filter spectra into subsets (GeMS-A, GeMS-B, GeMS-C) with consecutively larger sizes at the expense of quality; addressing redundancy through clustering using locality-sensitive hashing; and finally storing the processed spectra in a compact HDF5-based binary format designed specifically for deep learning applications [29].

The resulting GeMS datasets are orders of magnitude larger than existing spectral libraries and are systematically organized into numeric tensors of fixed dimensionality, thereby unlocking new possibilities for repository-scale metabolomics research [29]. For reference, 97% of spectra in the highest-quality GeMS-A subset were acquired using Orbitrap mass spectrometers, while the GeMS-C subset comprises 52% Orbitrap and 41% quadrupole time of flight (QTOF) spectra [29]. This careful curation and stratification strategy ensures that researchers can select the appropriate balance between data quality and quantity for their specific applications.

Diagram 1: GeMS dataset curation workflow showing sequential processing stages and quality-based stratification.

Model Architecture and Pre-training Methodology

The DreaMS framework implements a transformer-based neural network specifically designed for MS/MS spectra and trained using the massive GeMS dataset [29]. The core innovation lies in its self-supervised pretraining approach, which combines BERT-style spectrum-to-spectrum masked modeling with chromatographic retention order prediction [29]. The model represents each spectrum as a set of two-dimensional continuous tokens associated with pairs of peak m/z and intensity values, then masks a fraction (30%) of random m/z ratios from each set, sampled proportionally to corresponding intensities [29]. The training objective involves reconstructing these masked peaks, forcing the network to learn the underlying patterns and relationships within molecular fragmentation data.

Additionally, the architecture incorporates an extra precursor token that is never masked and designed to aggregate global information about the spectrum [29]. Through optimization toward these self-supervised objectives on unannotated mass spectra, the model spontaneously discovers rich representations of molecular structures that are organized according to structural similarity between molecules and demonstrate robustness to variations in mass spectrometry conditions [29]. These representations emerge as 1,024-dimensional real-valued vectors that effectively capture essential molecular characteristics without explicit supervision.

Table 2: DreaMS Framework Components and Specifications

| Component | Specification | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Network Architecture | Transformer-based neural network | Processes spectral data through self-attention mechanisms [29] |

| Model Parameters | 116 million parameters | Capacity to capture complex molecular patterns [29] |

| Input Representation | 2D continuous tokens (m/z and intensity pairs) | Encodes spectral peaks for transformer processing [29] |

| Pre-training Dataset | GeMS-A10 (highest-quality subset) | Provides curated, diverse molecular spectra for learning [29] |

| Output Representation | 1,024-dimensional vectors (DreaMS embeddings) | Captures structural similarity and robust molecular features [29] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Implementation

SSL Pretraining Protocol for Molecular Representations

The implementation of self-supervised learning for molecular data requires meticulous experimental design and execution. For the DreaMS framework, the pretraining phase employed the GeMS-A10 dataset, which represents the highest-quality subset of the GeMS collection with controlled redundancy [29]. The training process utilized the AdamW optimizer with a learning rate of 10⁻⁴ and a batch size of 512 spectra [29]. The model was trained for approximately 1 million steps on 8 NVIDIA A100 GPUs, requiring roughly two weeks to complete training [29]. The masking procedure for the BERT-style pretext task randomly selected 30% of spectral peaks for prediction, with sampling probability proportional to peak intensity to focus learning on more informative spectral features [29].

For graph-based molecular SSL implementations, the pretraining protocol typically involves node-level, edge-level, and graph-level objectives [19]. Node-level objectives may include atom type prediction or masking of atom features, while edge-level objectives involve bond type prediction or edge existence forecasting. Graph-level objectives often incorporate contrastive learning strategies that maximize agreement between differently augmented views of the same molecular graph while minimizing agreement with views from different molecules [19]. These multi-level learning objectives encourage the model to capture molecular characteristics at varying scales of granularity, from atomic properties to global molecular features.

Downstream Task Fine-tuning Methodology

Following self-supervised pretraining, the learned representations are typically adapted to specific downstream tasks through supervised fine-tuning. In the DreaMS framework, this process involved transferring the pretrained weights to task-specific models and then training with labeled datasets for applications including spectral similarity prediction, molecular fingerprint prediction, chemical property forecasting, and specialized tasks such as fluorine presence detection [29]. The fine-tuning process generally employs significantly smaller learning rates (typically 10-100 times smaller) than those used during pretraining to prevent catastrophic forgetting of the general-purpose representations acquired during self-supervised learning.

For molecular property prediction tasks, the standard evaluation protocol involves partitioning labeled datasets using scaffold splits to assess model performance on novel molecular architectures not encountered during training [19]. This rigorous evaluation strategy provides a more realistic measure of real-world applicability compared to random splits, particularly for drug discovery applications where generalization to new chemical scaffolds is essential. Performance metrics vary by application but commonly include ROC-AUC for classification tasks, RMSE for regression problems, and rank-based metrics for retrieval applications.

Diagram 2: Two-phase SSL framework showing pretraining with pretext tasks followed by task-specific fine-tuning.

Performance Evaluation and Comparative Analysis

Benchmark Results and State-of-the-Art Performance

The DreaMS framework demonstrates state-of-the-art performance across a variety of molecular analysis tasks following self-supervised pretraining and subsequent fine-tuning [29]. In spectral similarity assessment, which is fundamental to molecular networking and compound identification, DreaMS significantly outperformed traditional dot-product-based algorithms and unsupervised shallow machine learning methods such as MS2LDA and Spec2Vec [29]. For molecular fingerprint prediction—a crucial task for quantifying structural similarity and retrieving analogous compounds from databases—the framework surpassed the performance of established methods including SIRIUS and its computational pipeline of approximate inverse annotation tools based on combinatorics, discrete optimization, and machine learning leveraging mass spectrometry domain expertise [29].

The practical utility of the DreaMS representations was further validated through the construction of the DreaMS Atlas, a molecular network of 201 million MS/MS spectra assembled using DreaMS annotations [29]. This monumental achievement demonstrates the scalability of the approach and its applicability to repository-scale metabolomics research. The emergent representations were shown to be organized according to structural similarity between molecules and exhibited robustness to variations in mass spectrometry conditions, indicating that the model had learned fundamental aspects of molecular structure rather than merely memorizing instrumental artifacts [29].

Advantages Over Traditional and Supervised Approaches

Self-supervised learning approaches for molecular data offer distinct advantages over traditional methods and fully supervised deep learning models. Traditional molecular representations such as SMILES and structure-based molecular fingerprints, while foundational to computational chemistry, often struggle with capturing the full complexity of molecular interactions and conformations [19]. Their fixed nature means they cannot easily adapt to represent dynamic behaviors of molecules in different environments or under varying chemical conditions [19]. SSL-derived representations address these limitations by learning contextual, adaptable embeddings that capture underlying molecular principles.

Compared to fully supervised deep learning models, SSL approaches dramatically reduce the dependency on limited annotated spectral libraries, which cover only a tiny fraction of known natural molecules [29]. This is particularly valuable for molecular analysis, where experimental annotation of spectra is time-consuming, expensive, and requires specialized expertise. By leveraging unlabeled data at scale, SSL methods can develop a more comprehensive understanding of the chemical space, leading to improved generalization, especially for rare or novel molecular structures that may be absent from traditional training datasets.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Molecular Representation Learning Approaches

| Method Category | Representative Examples | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Descriptors | SMILES, Molecular Fingerprints [19] | Simple, interpretable, computationally efficient | Limited representation capacity, hand-crafted features [19] |

| Supervised Deep Learning | SIRIUS, MIST, MIST-CF [29] | Task-specific optimization, high performance on target tasks | Requires extensive labeled data, limited generalization [29] |

| Self-Supervised Learning | DreaMS, KPGT, 3D Infomax [29] [19] | Leverages unlabeled data, generalizable representations, reduces annotation dependency | Computationally intensive pretraining, complex implementation [29] [19] |

Successful implementation of self-supervised learning for molecular data requires both computational resources and domain-specific data assets. The following table summarizes key components of the research toolkit for developing and applying SSL approaches in molecular sciences.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular SSL

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Role in SSL Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Spectral Data Repositories | MassIVE GNPS [29], GeMS Dataset [29] | Sources of unlabeled MS/MS spectra for self-supervised pretraining |

| Computational Infrastructure | NVIDIA A100 GPUs [29], High-Performance Computing Clusters | Accelerate transformer pretraining on large-scale molecular datasets |

| Molecular Representation Libraries | RDKit, OpenBabel | Process and featurize molecular structures for graph-based SSL |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | PyTorch, TensorFlow, JAX | Implement and train neural network models for molecular SSL |

| Specialized Mass Spectrometry Instruments | Orbitrap Mass Spectrometers, QTOF Systems [29] | Generate high-quality experimental spectra for model training and validation |

| Benchmark Datasets | NIST20 Tandem Mass Spectral Library [29], MoNA [29] | Evaluate model performance on standardized molecular analysis tasks |

Future Frontiers and Research Directions

The field of self-supervised learning for molecular data continues to evolve rapidly, with several promising research directions emerging. Cross-modal fusion strategies that integrate graphs, sequences, and quantum descriptors represent a particularly exciting frontier [19]. These approaches aim to generate more comprehensive molecular representations by combining complementary information from multiple modalities, potentially leading to improved performance on complex prediction tasks such as reaction outcome forecasting and molecular interaction modeling.

Geometric learning approaches that incorporate 3D structural information through equivariant graph neural networks and related architectures offer another compelling direction [19]. By explicitly modeling molecular geometry and conformation, these methods can capture critical aspects of molecular behavior that are inaccessible to topology-only representations. Early implementations such as the 3D Infomax approach have demonstrated the significant potential of this paradigm [19].