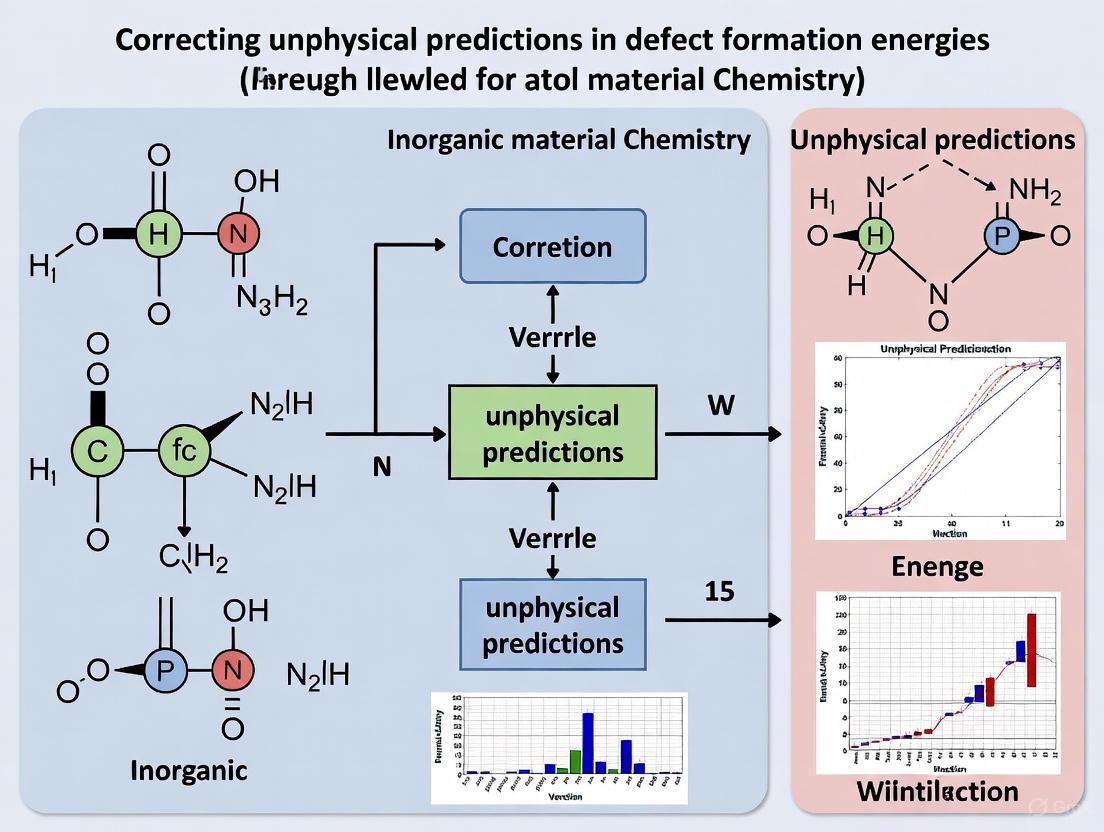

Correcting Unphysical Predictions in Defect Formation Energies: From Computational Fixes to AI Solutions

Accurate prediction of defect formation energies is paramount for advancing materials science, influencing properties from chemical reactivity to conductivity.

Correcting Unphysical Predictions in Defect Formation Energies: From Computational Fixes to AI Solutions

Abstract

Accurate prediction of defect formation energies is paramount for advancing materials science, influencing properties from chemical reactivity to conductivity. However, standard computational methods, particularly semi-local Density Functional Theory (DFT), are prone to unphysical predictions that can misdirect research. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers on this critical issue. We first explore the fundamental sources of these errors, including band gap underestimation and inadequate charge delocalization treatment. We then detail a spectrum of correction methodologies, from established a-posteriori schemes to innovative machine-learning potentials and defect-informed neural networks. The article further offers practical troubleshooting advice for implementing these corrections and concludes with a rigorous validation framework, benchmarking the performance of various approaches against high-fidelity hybrid-DFT calculations and experimental data to guide reliable materials design and discovery.

The Root of the Problem: Understanding Sources of Unphysical Defect Predictions

The Defect Formation Energy Equation and Its Vulnerabilities

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers calculating defect formation energies, a critical task for understanding material properties in semiconductors and other functional materials.

Understanding the Defect Formation Energy Equation

What is the fundamental equation for calculating defect formation energy?

The standard formalism for calculating the formation energy of a point defect ( X ) in charge state ( q ) is given by the Zhang-Northrup equation [1] [2]:

[E^f[X^q] = E{tot}[X^q] - E{tot}[bulk] - \sumi ni \mui + q(E{VBM} + \mue) + E{corr}]

Where:

- ( E_{tot}[X^q] ): Total energy of the defective supercell.

- ( E_{tot}[bulk] ): Total energy of the pristine bulk supercell.

- ( ni ): Number of atoms of type ( i ) added (( ni > 0 )) or removed (( n_i < 0 )).

- ( \mu_i ): Chemical potential of atom ( i ).

- ( q ): Charge state of the defect.

- ( E_{VBM} ): Valence Band Maximum energy of the pristine bulk.

- ( \mu_e ): Electron chemical potential (Fermi level), referenced from the VBM.

- ( E_{corr} ): Energy correction term for finite-size effects.

Unphysical predictions most frequently stem from three main issues [3] [1] [2]:

- Uncorrected Finite-Size Effects: When using charged defects in periodic boundary conditions, spurious electrostatic interactions occur between the defect and its periodic images. This long-range Coulomb interaction converges very slowly with increasing supercell size, leading to inaccurate total energies if not properly corrected [4] [1].

- Incorrect Potential Alignment: The term ( q(E{VBM} + \mue) ) requires a common energy reference between the bulk and defective supercells. An incorrect alignment of the electrostatic potentials far from the defect site introduces significant errors in the formation energy [1] [2].

- Improper Chemical Potentials: The chemical potentials ( \mu_i ) are not single values but depend on the experimental growth conditions of the material. An unphysical choice can lead to formation energies that are not experimentally realistic [4] [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

How do I correct for finite-size effects in charged defect calculations?

The recommended method to correct for finite-size effects is the Freysoldt-Neugebauer-Van de Walle (FNV) scheme [3] [1] [2]. The correction has two main components:

[E{corr} = E{lat} - q \Delta V]

- Lattice Energy Correction (( E_{lat} )): This corrects the electrostatic energy of the periodic array of model charges. A model charge distribution (e.g., a Gaussian) is placed at the defect site, and its periodic interaction energy is calculated and subtracted [1].

- Potential Alignment (( \Delta V )): This aligns the electrostatic potential of the defective supercell in a region far from the defect with the potential of the pristine bulk supercell. This ensures the electronic chemical potential is referenced correctly [1] [2].

Experimental Protocol for FNV Correction [1] [2]:

- Calculate Total Energies: Perform DFT calculations for both the pristine bulk supercell and the charged defective supercell to get ( E{tot}[bulk] ) and ( E{tot}[X^q] ).

- Compute Electrostatic Potential: Extract the electrostatic potential for both the bulk and defective supercells from your calculation.

- Choose a Model Charge: A typical choice is a 3D Gaussian distribution ( \rho^m(r) = \frac{q}{(\sqrt{2\pi}\sigma)^3} e^{-r^2/(2\sigma^2)} ), where the width ( \sigma ) should reflect the actual defect charge distribution.

- Calculate ( E{lat} ): The lattice energy for a Gaussian model in a dielectric medium with constant ( \varepsilon ) is: [ E{lat} = \frac{2\pi}{\varepsilon \Omega} \sum_{\vec{G} \neq 0} \frac{q^2 e^{-G^2\sigma^2}}{G^2} - \frac{q^2}{2\sqrt{\pi}\varepsilon\sigma} ] where ( \Omega ) is the supercell volume and ( \vec{G} ) are reciprocal lattice vectors.

- Determine ( \Delta V ): Align the electrostatic potential of the defective cell (( V^{X^q}{el} )) with the bulk potential (( V^{0}{el} )) in a region far from the defect, often by planar or atomic-site averaging: [ \Delta V = \frac{1}{A} \int dx dy \left[ V(\vec{r}) - (V^{X^q}{el}(\vec{r}) - V^{0}{el}(\vec{r})) \right]{z=z0} ] Here, ( V(\vec{r}) ) is the potential from the model charge.

My defect formation energy does not converge with supercell size. What should I do?

This is a classic symptom of insufficient correction for electrostatic interactions.

Step-by-Step Solution:

- Verify Your Correction Scheme: Ensure the FNV correction (or a similar scheme like Lany-Zunger) is correctly implemented. Pay close attention to the potential alignment step, as this is a common source of error [2].

- Check the Dielectric Constant: The FNV correction requires the static dielectric constant ( \varepsilon ) of your material. Using an incorrect value (especially an isotropic one for an anisotropic material) will yield poor convergence. Calculate this value from first principles or use a reliable experimental value [3] [2].

- Increase Supercell Size Systematically: Calculate the formation energy for a series of increasingly large supercells (e.g., 2x2x2, 3x3x3, 4x4x4). Plot the corrected formation energy against the inverse of the supercell size. Well-behaved, localized defects will show a linear trend converging to a finite value [4] [2].

- Inspect the Charge Localization: For highly delocalized charge states (common in small band gap semiconductors), the simple FNV model might be less effective. In such cases, using a more sophisticated model charge or significantly larger supercells may be necessary.

The table below shows an example of convergence for a carbon vacancy in diamond, where the energy stabilizes with a 4x4x4 supercell or larger [4].

| Supercell Size | Number of Atoms | Defect Formation Energy (eV) |

|---|---|---|

| 2x2x2 | 64 | 9.15 |

| 3x3x3 | 216 | 8.57 |

| 4x4x4 | 512 | 8.42 |

| 5x5x5 | 1000 | 8.41 |

How do I choose appropriate chemical potentials (( \mu_i ))?

The chemical potentials are not arbitrary and must be chosen to represent physically realistic experimental conditions [4] [3].

Methodology:

- Establish Bounds: The chemical potentials are constrained by the stability of the host material and the formation of competing phases. For a binary compound AB:

- ( \muA + \muB = \Delta Hf(AB) ), where ( \Delta Hf(AB) ) is the formation enthalpy of AB.

- ( \muA \leq \muA^{bulk} ) and ( \muB \leq \muB^{bulk} ) to prevent precipitation of elemental phases.

- Choose Reference States: A common choice is to use the total energy per atom of the elemental ground-state structure as the reference [4] [3]. For example:

- Map the Phase Stability: Vary ( \mu_i ) within their allowed bounds to see how the defect formation energy changes under different growth conditions (e.g., metal-rich vs. anion-rich).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

The VBM should be obtained from a well-converged band structure or density-of-states (DOS) calculation of the pristine, bulk material [3] [2]. Do not use the VBM from the defective supercell, as the defect can introduce shifts and gap states that make the identification unreliable. The workflow is: 1) Relax the bulk unit cell; 2) Perform a static calculation on the relaxed bulk with a dense k-point grid; 3) Analyze the DOS or band structure to extract the VBM energy.

Should I use a different k-point grid for the bulk and defect calculations?

Yes. The pristine bulk calculation used to determine the VBM and as a reference often requires a denser k-point grid because it is typically performed on a smaller unit cell. For the large supercells used in defect calculations, a much sparser k-point grid (sometimes only the Γ-point) is sufficient and computationally necessary [4]. Always ensure your k-point grids are converged for their respective cell sizes.

What is the "ghost atom" method and when should I use it?

When creating a vacancy, instead of simply deleting an atom, you can convert it to a "ghost" atom. This means the atom is removed from the structure, but its basis functions are retained in the calculation. This corrects for the Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSSE), which can slightly improve the accuracy of the energy difference with an insignificant computational cost [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key computational "reagents" and parameters essential for reliable defect formation energy calculations.

| Item | Function / Description | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Code | Software to perform first-principles energy calculations. | QuantumATK [3] [2], GPAW [1], SCM (BAND) [4], Quantum ESPRESSO [4]. |

| Pseudopotentials | Replace core electrons to reduce computational cost. | Use consistent and validated sets (e.g., PBE-based for GGA calculations). |

| Exchange-Correlation Functional | Approximates the quantum mechanical electron-electron interactions. | LDA, PBE (GGA), PBESol (for solids) [3]; Hybrid functionals or GW for accurate band gaps. |

| Dielectric Constant (( \varepsilon )) | Critical input for electrostatic corrections of charged defects. | Can be computed from DFPT or extracted from optical spectrum calculations [2]. |

| Chemical Potential Reference | Provides energy reference for atoms added/removed to form the defect. | Ground-state elemental phases (e.g., diamond for C, O₂ molecule for O) [4]. |

| Supercell | A large, periodic cell to model an isolated defect. | Must be large enough to minimize defect-defect interactions; size testing is mandatory [4] [2]. |

| FNV Correction Script/Tool | Applies necessary energy corrections for charged defects. | May be built into modern codes (e.g., QuantumATK study object) [2] or require manual implementation [1]. |

Band Gap Underestimation in Semi-Local DFT and Its Cascading Effects

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Unphysical Predictions in Defect Formation Energies

FAQ: Addressing Common Computational Issues

1. Why do my calculated defect formation energies seem unphysical or show incorrect trends? Unphysical defect formation energies are frequently a direct cascading effect of the well-known band gap underestimation in semi-local DFT (e.g., LDA, GGA). The formation energy of a charged defect depends explicitly on the position of the Fermi level, which is constrained by the underestimated band gap [5]. This forces the Fermi level into an incorrect, often unphysical, energy range during the calculation, severely distorting the resulting formation energies [6] [5].

2. My GGA calculation predicts the correct crystal structure but a metallic state for an insulator. What is wrong? This is a classic symptom of the band gap problem, particularly pronounced in materials with strongly correlated electrons, such as actinide oxides (e.g., NpO2). Semi-local functionals fail to describe the strong electronic correlations, which can lead to a spurious prediction of metallic behavior instead of the experimentally observed insulating state [5]. Moving to a method that accounts for strong correlations, such as DFT+U or a hybrid functional, is necessary [5].

3. Is it sufficient to just use a hybrid functional on a GGA-optimized structure to get an accurate band gap? While this common workflow is computationally efficient, caution is advised. A systematic study has shown that the potential alignment at an interface calculated with GGA is often within 50 meV of the value from a more expensive HSE calculation, even when the geometries are fully relaxed with their respective functionals [7]. Therefore, for band offset calculations, combining GGA-optimized structures (for the potential alignment) with HSE-calculated bulk band structures can be a reliable and efficient approach [7]. However, for the total energy calculations required for defect formation energies, a consistent methodology is crucial.

4. Besides the band gap, what other electronic properties change when I switch from GGA to a hybrid functional? The change is not merely a "rigid shift" or a "scissor operator" adjustment. Hybrid functionals can alter the character of the bands themselves [6]. This is because they partially correct the self-interaction error present in semi-local functionals, which can change the relative ordering and dispersion of bands. The impact is most significant in systems where self-interaction error is large, such as in materials with localized d or f electrons, and can dramatically affect the predicted electronic structure and properties like optical selection rules [6].

Diagnostic Tables and Protocols

Table 1: Comparison of DFT Methodologies for Defect Calculations

| Method | Typical Band Gap Error | Computational Cost | Recommended Use Case | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GGA (PBE) | Severe underestimation (can be several eV) [7] | Low (baseline) | Initial structure optimization; high-throughput screening of geometries [8] | Unreliable for band gaps and defect energetics in wide-gap materials [7] [5] |

| DFT+U | Varies, can be greatly improved | Moderate | Systems with strongly localized electrons (e.g., transition metals, actinides) [5] | The U parameter is material-specific and requires careful tuning [5] |

| Hybrid (HSE) | ~0.2 eV mean absolute error for semiconductors [9] | High | Accurate band gap and defect property calculations [7] [9] | Computationally expensive for large supercells or structural relaxations [7] |

| G(0)W(0) | High accuracy (often considered a benchmark) [8] | Very High | Benchmarking properties for small systems [8] | Prohibitively costly for most defect supercell calculations [8] |

| ML-Corrected PBE | ~0.25 eV RMSE vs. G(0)W(0) [8] | Low (after model training) | High-throughput materials discovery where G(0)W(0) accuracy is needed [8] | Model transferability depends on training data |

Table 2: Cascading Effects of Band Gap Underestimation on Defect Properties

| Affected Property | Manifestation of the Problem | Consequence for Research |

|---|---|---|

| Defect Formation Energy | Strong dependence on Fermi level, which is constrained by an incorrect band gap [5] | Predicts incorrect stable defect charge states and formation energies [5] |

| Defect Charge-State Transition Levels | Incorrect positioning within the band gap [6] | Misidentification of dopability and carrier trapping behavior |

| Material's Stoichiometry & Stability | Formation energies vary with chemical potentials, which are incorrectly evaluated [5] | Unreliable prediction of stable phases under different growth conditions (e.g., O-rich vs. O-poor) [5] |

Experimental Protocol: Accurate Defect Formation Energy Calculation using Hybrid Functionals

This protocol outlines a robust methodology for calculating defect formation energies, mitigating the errors from semi-local DFT.

- Build a Defect Supercell: Construct a sufficiently large supercell of the host material to minimize spurious interactions between periodic images of the defect. A 2x2x2 or 3x3x3 expansion is often a starting point [5].

- Geometry Optimization with a Hybrid Functional: Fully relax the atomic positions of the defective supercell using a hybrid functional like HSE. Note: This is the most computationally expensive step but is crucial for accuracy. As a potential workaround, literature suggests that for some properties like band offsets, a GGA-relaxed structure can be used without significant loss of accuracy for the subsequent single-point energy calculation with a hybrid functional [7]. However, for formation energies, consistency is key.

- Calculate Total Energies: Perform single-point energy calculations to obtain the total energy of the defective supercell ((E{\text{def}}^{\text{tot}})) and the perfect supercell ((E{\text{perf}}^{\text{tot}})) at the same level of theory (hybrid functional).

- Compute Formation Energy: Use the standard formula to calculate the defect formation energy [5]: ( \Delta E{\text{def}}(X^q) = E{\text{def}}^{\text{tot}} - E{\text{perf}}^{\text{tot}} + \sumi \Delta ni \mui + qEF ) Here, (q) is the defect charge state, (\Delta ni) and (\mui) are the change in number and chemical potential of atoms of type (i), and (EF) is the Fermi level. The accuracy of the hybrid functional's band gap ensures (E_F) varies within a physically meaningful range.

Methodological Pathways and Computational Tools

Decision Workflow for Correcting Band Gap-Related Errors

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Accurate Defect Energetics

| Tool / Functional | Category | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| HSE (Heyd-Scuseria-Ernzerhof) | Screened Hybrid Functional | Provides accurate band gaps and electronic structures; the gold standard for defect calculations in semiconductors and insulators [7] [9]. |

| DFT+U | Hubbard Model Correction | Adds a penalty term for electron localization, crucial for correcting the description of strongly correlated 5f/3d electrons in materials like actinide oxides [5]. |

| Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) Model | Machine Learning Correction | Corrects DFT-PBE band gaps to G(0)W(0) accuracy at PBE cost, ideal for high-throughput discovery [8]. |

| FHI-aims | All-Electron DFT Code | Enables large-scale hybrid DFT calculations on systems with thousands of atoms, bridging the gap between accuracy and system size [10]. |

| VASP | Plane-Wave DFT Code | A widely used platform that implements various functionals (GGA, HSE, DFT+U) suitable for the protocols described here [5]. |

Charge Delocalization Errors and Improper Electrostatic Treatments

Core Concepts FAQ

What are charge delocalization and localization errors in computational research?

Charge delocalization error, also known as self-interaction error (SIE), is a fundamental limitation in approximate density functional theory (DFT) functionals where electrons spuriously delocalize over multiple nuclei or fragments. This occurs due to incomplete cancellation of the Hartree and exchange contributions, causing electrons to interact with themselves [11] [12]. Conversely, localization error represents the opposite problem, where electron density becomes artificially confined to specific regions. Both errors represent significant deviations from physically accurate electron distribution [11].

How do these errors impact defect formation energy predictions?

In defect formation energy research, these errors cause several unphysical predictions:

- Delocalization Error: Leads to underestimation of charge transition levels and formation energies, as the energy cost of adding/removing electrons is inaccurately represented [12].

- Localization Error: Can create artificial symmetry breaking in defect systems, even when strong correlation is absent. For example, in the TiZnvO defect in ZnO, semilocal functionals spuriously break C3v symmetry, while hybrid functionals preserve it [11].

- Energy Profile Distortions: Typical semilocal functionals exhibit convex deviations from the piecewise linear behavior of total energy with respect to fractional electron number, affecting defect charge state stability predictions [11].

What practical consequences might researchers observe in their calculations?

Researchers may encounter:

- Incorrect dissociation limits of charged dimers and molecular clusters [12]

- Spurious barriers in reaction pathways [12]

- Artificial symmetry breaking in symmetric systems [11]

- Underestimated band gaps in insulating materials [11]

- Improper charge localization in charged molecular clusters like (CH4)n+ [12]

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Unexpected symmetry breaking in defect systems

Diagnosis: This often indicates self-interaction error-induced artificial symmetry breaking, particularly in systems without genuine strong correlation [11].

Solutions:

- Functional Selection: Use hybrid functionals with exact exchange or specialized functionals designed to reduce SIE. Testing shows that while LDA, PBE, and SCAN break symmetry in model systems, properly designed functionals and Hartree-Fock preserve it [11].

- Validation Method: Compare results with high-level wavefunction methods or perform calculations on one-electron model systems like Hₙ×⁺²/ₙ⁺(R) to identify functional-induced artifacts [11].

- Systematic Testing: Incrementally increase system size and monitor symmetry preservation. Research shows symmetry breaking often emerges as system size increases [11].

Problem: Improper charge localization in molecular clusters

Diagnosis: This manifests as unrealistic charge distribution across molecular complexes, particularly in charged systems like (CH₄)ₙ⁺ clusters [12].

Solutions:

- Specialized Functionals: Implement functionals specifically designed to treat charge delocalization together with nondynamic correlation [12].

- Benchmarking: Test functional performance on symmetric charged dimers A₂⁺, a stringent test for charge delocalization error [12].

- Reference Comparison: Validate against CCSD(T) results throughout the dissociation range to assess functional accuracy [12].

Problem: Inaccurate electrostatic potential predictions

Diagnosis: Errors in modeling noncovalent interactions and ionic systems due to improper electrostatic treatment [13].

Solutions:

- Surface Potential Analysis: Compute molecular surface electrostatic potentials on 0.001 au electronic density contours using methods like B3PW91/6-31G(d,p) [13].

- Statistical Quantities: Utilize derived parameters including average deviation Π, positive/negative variances (σ₊², σ₋²), and balance parameter ν to quantify electrostatic features [13].

- Experimental Validation: Compare computational results with experimental diffraction methods where possible [13].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Validating Symmetry Preservation in Defect Systems

Purpose: To identify and mitigate artificial symmetry breaking caused by self-interaction error [11].

Procedure:

- System Selection: Choose a symmetric defect system with known electronic structure (e.g., TiZnvO in ZnO with C3v symmetry) [11].

- Computational Setup:

- Analysis:

- Monitor electron density distribution across symmetric equivalent sites.

- Compare symmetry preservation between functional types.

- Reference against exact solutions or high-level theory for one-electron systems [11].

Expected Outcome: Hybrid functionals should preserve symmetry while semilocal functionals may show artificial breaking, indicating SIE influence [11].

Protocol 2: Assessing Charge Delocalization in Molecular Clusters

Purpose: To evaluate and correct improper charge delocalization in charged systems [12].

Procedure:

- Test Systems: Select symmetric charged dimers A₂⁺ and molecular clusters like (CH₄)ₙ⁺ [12].

- Functional Development:

- Validation Metrics:

- Benchmarking: Compare results with CCSD(T) across the entire dissociation range [12].

Expected Outcome: Properly corrected functionals should predict realistic charge localization and nearly constant ionization potentials regardless of cluster size [12].

Protocol 3: Quantitative Electrostatic Potential Analysis

Purpose: To characterize electrostatic properties for understanding interactive tendencies [13].

Procedure:

- Computational Method:

- Surface Potential Calculation:

- Ionic System Application:

Expected Outcome: Consistent trends in electrostatic potential statistical quantities that predict interactive behavior and physical properties of ionic systems [13].

Table 1: Functional Performance in Addressing Delocalization/Localization Errors

| Functional | Error Type Addressed | Test System | Performance | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDA/PBE/SCAN | Multiple errors | Hₙ×⁺²/ₙ⁺(R) model | Artificial symmetry breaking; Electron localization at large R; Delocalization at small R [11] | Severe SIE; Spurious symmetry breaking [11] |

| Proof-of-Concept DFA | Localization error | Hₙ×⁺²/ₙ⁺(R) model | Preserves symmetry; Reduces delocalization error [11] | Slight overlocalization in some systems [11] |

| Modified SIE-Functional | Charge delocalization | A₂⁺ dimers; (CH₄)ₙ⁺ clusters | Correct charge localization; Nearly constant IP; Matches CCSD(T) dissociation [12] | Requires validation across diverse systems [12] |

| Hybrid Functionals | Self-interaction error | TiZnvO defect in ZnO | Preserves C3v symmetry; Proper localization [11] | Computational cost [11] |

Table 2: Electrostatic Potential Statistical Quantities for Common Molecules

| Molecule | Π (kcal/mol) | σtot² | ν | νσtot² | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | 22.2 | 85.0 | 0.250 | 21.2 | Highest variance despite small size [13] |

| Methane | 3.0 | 5.9 | 0.250 | 1.5 | Zero dipole moment [13] |

| N₂ | 4.4 | 12.2 | 0.250 | 3.1 | Zero dipole moment [13] |

| Acetylene | 12.4 | 70.2 | 0.249 | 17.5 | Significant internal charge separation [13] |

| Dimethyl ether | 8.9 | 36.7 | 0.247 | 9.1 | Least balanced molecule [13] |

Diagnostic and Solution Workflows

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Electrostatic Error Correction

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| B3PW91/6-31G(d,p) | Computational Method | Accurate electrostatic potential calculation | Predicting molecular interactive tendencies; Ionic system analysis [13] |

| Modified SIE-Functional | Specialized Functional | Charge delocalization error reduction | Charged dimer dissociation; Molecular cluster charge localization [12] |

| Proof-of-Concept DFA | Specialized Functional | Artificial symmetry breaking prevention | Model system validation; Defect symmetry preservation [11] |

| Hₙ×⁺²/ₙ⁺(R) Model | Test System | Self-interaction error identification | Functional validation; Symmetry preservation testing [11] |

| Surface Electrostatic Potential Analysis | Analytical Method | Interactive tendency quantification | Noncovalent interaction prediction; Ionic system characterization [13] |

| Bayesian Active Learning | Machine Learning Approach | Electron density prediction | Accelerated exploration of material properties [14] |

Challenges of Anisotropic Environments in Molecular Materials

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What does "anisotropic" mean in the context of molecular materials, and why is it a challenge? Anisotropy refers to a material's property of being direction-dependent; its physical or chemical characteristics vary when measured along different axes [15] [16]. In molecular materials, this manifests as orientation-dependent optical, thermal, and mechanical properties [15] [17]. This is a significant challenge because it complicates the accurate prediction of material behavior, including defect formation energies. Standard models that assume uniform, isotropic behavior can yield unphysical results when applied to these complex, direction-dependent systems [18] [16].

Q2: My simulations for defect formation energies in an anisotropic crystal are producing unphysical (negative) values. What could be wrong? This is a common issue when the computational model does not fully account for the material's structural anisotropy. Key factors to check include:

- Anisotropic Elastic Constants: Ensure your model uses the full stiffness tensor (with up to 21 independent coefficients for a fully anisotropic material) rather than simplified isotropic elastic constants [16].

- Strain Energy Contribution: In anisotropic media, the strain field generated by a point defect is not symmetric. An isotropic approximation can severely underestimate this energy contribution, leading to incorrect (often negative) formation energies [16] [19].

- Supercell Size and Shape: The simulation cell must be large enough to avoid spurious interactions between periodic images of the defect, and its shape should be compatible with the anisotropic symmetry of the host lattice.

Q3: How can I experimentally characterize point defects in an anisotropic 2D material like ReSe₂? Atomic-scale techniques are required. A standard methodology involves:

- Material Synthesis: Prepare monolayer ReSe₂ via chemical vapor deposition (CVD) [19].

- Defect Imaging: Use Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (STEM) to directly visualize various point defects like vacancies (VSe1-4), isoelectronic substitutions (OSe1-4, SSe1-4), and antisite defects (SeRe1-2, ReSe1-4) [19].

- Statistical Analysis: Count defect densities across multiple images to determine the most prevalent types [19].

- In-Situ Irradiation: Use the electron beam to dynamically study the creation and evolution of Se vacancies [19].

- Theoretical Validation: Correlate findings with Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations to determine formation energies and electronic structures (e.g., in-gap states introduced by vacancies) [19].

Q4: How do I measure anisotropic thermal conductivity in a polymer fiber? Thermal conductivity (κ) becomes a tensor property in anisotropic materials. The standard protocol involves:

- Sample Preparation: Fabricate aligned polymer fibers or films with a high draw ratio to maximize chain orientation [20].

- Directional Measurement: Use a technique like the 3ω method or transient thermal grating to measure thermal transport parallel and perpendicular to the polymer chain alignment.

- Data Analysis: You will find a high κ∥ (parallel to chains) and a low κ⊥ (perpendicular to chains). The anisotropy ratio is κ∥/κ⊥. Key factors influencing this are crystallinity, chain orientation, and phonon scattering mechanisms [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Troubleshooting Defect Formation Energy Calculations

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unphysical negative formation energies | Isotropic approximation of elastic properties; improper supercell size [16]. | Implement a fully anisotropic elastic tensor in the computational model [16]. |

| Large variance in reported formation energies for the same defect | Inconsistent treatment of chemical potentials in anisotropic environments [19]. | Standardize the calculation of element-specific chemical potentials based on stable reference phases relevant to the anisotropic crystal structure [19]. |

| Poor convergence of formation energy with supercell size | Anisotropic strain fields causing long-range interactions [16]. | Use elongated supercells that align with the soft crystallographic directions to properly accommodate the strain field. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Experimental Characterization of Anisotropy

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent optical characterization (e.g., birefringence) | Uncontrolled sample orientation during measurement [15]. | Implement a rotational stage to perform angle-resolved measurements. Always reference the crystal axes. |

| Low measured anisotropic thermal conductivity ratio in polymers | Insufficient chain alignment or low crystallinity [20]. | Increase the draw ratio during fiber spinning and optimize post-processing (e.g., annealing) to enhance crystallinity and alignment [20]. |

| Difficulty interpreting light scattering data | Assuming the material is isotropic [17]. | Employ a combined spatiotemporal analysis (e.g., transient imaging) with Monte Carlo simulations that account for the full scattering tensor [17]. |

Experimental Data & Protocols

| Defect Type | Example | Key Impact on Properties (from DFT) |

|---|---|---|

| Vacancy | VSe1, VSe2 | Introduces mid-gap electronic states. |

| Isoelectronic Substitution | OSe1, SSe1 | Can quench in-gap states caused by vacancies. |

| Antisite | ReSe1, SeRe1 | Can introduce localized magnetic moments. |

Protocol 1: Fabricating Anisotropic Shape Memory Polymer Composites (SMPCs) [18]

- Materials: Plain woven carbon fabric, liquid tert-butyl acrylate (tBA), polyethylene glycol dimethacrylate (PEGDMA - crosslinker), diethylene glycol dimethacrylate (DEGDMA - crosslinker), 2,2-dimethoxy-2-phenylacetophenone (DMPA - photoinitiator).

- Resin Preparation: Mix tBA monomer with PEGDMA and DEGDMA crosslinkers. Add 1 wt% DMPA photoinitiator and stir until fully dissolved.

- Composite Layup: Impregnate carbon fabric layers with the resin. Stack layers at the desired fiber orientations (e.g., [0°/90°], [-45°/45°]).

- Curing: Place the layup in a UV photopolymerization chamber. Cure for 2 hours under a UV intensity of 10 mW/cm².

- Post-Processing: Post-cure the composite in an oven at 80°C for 24 hours to complete the polymerization.

Protocol 2: Creating Anisotropic Hydrogels via Magnetic Field Alignment [15]

- Gel Precursor: Prepare a hydrogel precursor solution containing monomers (e.g., acrylamide), crosslinker, and magnetic nanoparticles (e.g., iron oxide).

- Alignment: Place the solution in a strong, uniform magnetic field (> 0.5 T). The field will align the magnetic nanoparticles and any suspended anisotropic nanostructures.

- Polymerization: Initiate polymerization (e.g., thermally or with UV light) while the magnetic field is applied, "freezing" the aligned structure into the gel.

- Result: The resulting hydrogel will exhibit anisotropic swelling and mechanical properties, being stiffer and swelling less along the alignment direction [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Anisotropic Material Experiments

| Material / Reagent | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Plain Woven Carbon Fabric [18] | Provides anisotropic mechanical reinforcement in composite materials, dictating direction-dependent strength and stiffness. |

| Liquid Crystal Monomers [15] | The building blocks for liquid crystal polymers (LCPs); their self-assembling nature is key to creating molecular-scale anisotropy. |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles (e.g., Fe₃O₄) [15] | Used as an additive to induce macroscopic anisotropy in polymeric materials (e.g., hydrogels) through application of an external magnetic field during processing. |

| tBA, PEGDMA, DEGDMA [18] | Monomer and crosslinkers used in the photopolymerization of shape memory polymers, forming the matrix of anisotropic SMPCs. |

| 2,2-dimethoxy-2-phenylacetophenone (DMPA) [18] | A photoinitiator that generates free radicals upon UV exposure to initiate polymerization in resin systems. |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Diagram 1: Logic flow for correcting unphysical defect energies.

Diagram 2: Workflow for anisotropic defect analysis.

The Critical Role of Chemical Potential Approximations

In computational materials science and drug development, accurately predicting the behavior of materials requires a deep understanding of point defects—vacancies, substitutions, and interstitials that inevitably exist in any real material. These defects profoundly influence electrical conductivity, chemical reactivity, and optical properties. The formation energy of a defect determines its concentration under specific environmental conditions and is calculated using the equation [4] [21]:

[E^f(Dq) = E{\text{tot}}(Dq) - E{\text{tot}}(\text{bulk}) + \sumi ni\mui + qEF + E_{\text{corr}}]

In this fundamental equation, the (\sumi ni\mui) term represents the chemical potential component, where (ni) indicates the number of atoms of species (i) added to ((ni > 0)) or removed from ((ni < 0)) the system to form the defect, and (\mu_i) is their chemical potential [4]. The chemical potential effectively represents the energy of a single atom being taken from or added to a reservoir [4]. Unphysical approximations in these chemical potential values stand as a primary source of erroneous defect formation energy predictions, potentially leading to incorrect conclusions about material stability, reactivity, or functionality [21].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is chemical potential in simple terms, and why does it matter for defect calculations?

The chemical potential, denoted as (\mu_i), represents the energy that can be absorbed or released when the number of particles of a specific species changes [22]. In practical terms for defect calculations, it is the energy cost of obtaining an atom from a reference source (or donating it to one) when creating a defect [4]. For example, when creating a vacancy in diamond, you need to remove a carbon atom and place it somewhere, and the chemical potential represents the energy associated with that carbon atom in its reservoir [4]. The chemical potential dictates how easily defects form under different environmental conditions, making it critical for predicting defect concentrations and resulting material properties [21].

Q2: My defect formation energies yield negative values for stable compounds. What is wrong?

Negative defect formation energies that suggest spontaneous defect formation in stable materials typically indicate unphysically chosen chemical potentials. The chemical potentials of elements in a stable compound are constrained by thermodynamic stability requirements [23]. For instance, in TiO₂ (rutile), the chemical potentials of Ti and O must satisfy [23]: [ \mu\mathrm{Ti} + 2\mu\mathrm{O} = \mu\mathrm{TiO2(\text{rutile})} ] and also remain less than or equal to their standard state values (e.g., (\mu\mathrm{Ti} \leq \mu\mathrm{Ti(\text{HCP})}) and (\mu\mathrm{O} \leq \frac{1}{2}\mu{\mathrm{O}_2})) [23]. Violating these constraints by selecting chemical potentials that are too high makes the system appear to gain energy by forming defects, leading to nonsensical negative formation energies. This can be corrected by implementing thermodynamic equilibrium constraints to establish physically meaningful bounds on chemical potential values [23].

Molecular materials present particular challenges because molecules have internal degrees of freedom and specific bonding environments. A thoughtful treatment of molecular phase space is required [21]. The standard approximation of using isolated, gas-phase molecules as references can introduce significant errors. For accurate results, you must account for the actual molecular environment and the energy changes associated with molecular reorganization when defects are present [21]. This often requires more sophisticated treatments that consider the molecular dynamics and the anisotropic electron density distributions around defects in molecular systems [21].

Q4: What is the difference between "metal-rich" and "oxygen-rich" conditions in practice?

These conditions represent the thermodynamic extremes within which chemical potentials can vary while maintaining stability of the host material [23]:

- O-rich conditions: The chemical potential of oxygen ((\mu_\mathrm{O})) is at its maximum possible value (typically referenced to an O₂ molecule), while the metal chemical potential is at its minimum [23].

- Ti-rich conditions: The chemical potential of titanium ((\mu_\mathrm{Ti})) is at its maximum (referenced to bulk Ti metal), while the oxygen chemical potential is at its minimum [23].

Actual experimental conditions (during synthesis or operation) fall somewhere between these extremes. Reporting defect formation energies for both limits provides bounds on what is thermodynamically possible [23].

Q5: How do charged defects affect chemical potential considerations?

Charged defects introduce additional complexity through the (qEF) term in the formation energy equation, where (EF) is the Fermi level [21]. While this doesn't directly change the elemental chemical potential term (\sumi ni\mui), accurate calculation requires careful alignment of the electrostatic potential between defective and pristine cells, and appropriate correction schemes ((E{\text{corr}})) to address spurious interactions between periodic images of the charged defect [4] [21]. For molecular materials with anisotropic charge distributions, correction schemes that account for local fields are particularly important [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Unphysical Defect Formation Energies

Symptoms:

- Negative formation energies for defects in stable compounds.

- Formation energies change dramatically with small variations in calculation parameters.

- Predictions contradict experimental observations of material stability.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Check Thermodynamic Constraints: For a compound (AxBy), verify that your chosen chemical potentials satisfy: [ x\muA + y\muB = \mu{AxBy} ] Ensure (\muA \leq \mu{A(\text{bulk})}) and (\muB \leq \mu_{B(\text{reference})}) to prevent precipitation of elemental phases [23].

Map the Feasible Region: Use computational tools (like the Spinney package for Python) to map the entire thermodynamically accessible range of chemical potential values. The example below shows output for TiO₂ [23]:

This output confirms the chemical potential bounds for stable TiO₂ [23].

Identify Competing Phases: Calculate the formation energies of potential competing phases in your chemical system. Plot the feasible region to visualize which competing phases would precipitate before chemical potentials reach their elemental limits, as shown in this diagram [23]:

Problem 2: Inconsistent Results Across Different Research Groups

Symptoms:

- Published defect formation energies for the same system vary significantly.

- Disagreement on which defects are dominant under specific conditions.

- Difficulty reproducing published computational results.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Standardize Chemical Potential References: Ensure all groups use the same reference states. For example:

Document Calculation Parameters Completely: Create a standardized reporting table:

Parameter Specification Example Value Reference States Elemental/molecular forms used O₂ molecule, Diamond C Chemical Potential Values Numerical values with units μ_C = -9.874 eV/atom Computational Method DFT functional, basis set PBE, DZ Supercell Size Dimensions of computational cell 3×3×3 k-point Grid Sampling of Brillouin zone 3×3×3 Correction Schemes Charged defect corrections Freysoldt et al. scheme Verify k-point Convergence: For neutral defects, formation energies converge relatively quickly with supercell size. However, k-point sampling significantly affects energy calculations. The diagram below illustrates the convergence workflow [4]:

Problem 3: Poor Convergence in Molecular Material Defect Calculations

Symptoms:

- Defect formation energies oscillate with increasing supercell size.

- Significant errors persist despite large computational cells.

- Particularly problematic for molecular materials with anisotropic structures.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Implement Anisotropic Correction Schemes: Standard isotropic correction schemes (like Gaussian charge models) perform poorly for molecular materials with dipoles and anisotropic electron densities. Use correction schemes specifically designed for such systems, such as those proposed by Kumagai and Oba, or Suo et al., which better account for local fields created by defects near molecules [21].

Account for Molecular Reorganization Energy: In molecular materials, defect formation often involves significant molecular rearrangement. Standard approaches that treat molecules as rigid bodies introduce errors. Implement methods that account for the full molecular phase space and the energy cost of molecular reorganization [21].

Validate with Multiple Supercell Sizes: Always compute defect formation energies across a range of supercell sizes (e.g., 2×2×2, 3×3×3, 4×4×4) to identify convergence. The example below shows how vacancy formation energy in diamond converges with supercell size [4]:

| Supercell Size | Number of Atoms | Vacancy Formation Energy (eV) |

|---|---|---|

| 2×2×2 | 64 | 9.21 |

| 3×3×3 | 216 | 8.57 |

| 4×4×4 | 512 | 8.43 |

| 5×5×5 | 1000 | 8.41 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Calculating Neutral Vacancy Formation Energy in Diamond

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for calculating the formation energy of a neutral carbon vacancy in diamond using density functional theory (DFT) [4].

Research Reagent Solutions:

| Computational Tool | Function |

|---|---|

| DFT Code (BAND, QE) | Performs quantum mechanical energy calculations |

| Supercell Generation | Creates larger periodic structures from unit cells |

| k-point Grid | Samples the Brillouin zone for accurate integration |

| Basis Set | Represents electron wavefunctions in DFT calculations |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Perfect Structure Calculation:

- Start with a conventional diamond unit cell (cubic structure).

- Generate a 3×3×3 supercell containing 216 atoms using crystal editing tools.

- Set numerical quality to "Good" for k-space sampling, resulting in a 3×3×3 k-point grid.

- Run a single-point DFT calculation with LDA exchange-correlation potential and DZ basis set.

- Record the total energy (E_p = -2118.32) eV [4].

Defective Structure Preparation:

- From the perfect structure, select and delete one carbon atom to create a vacancy, resulting in 215 atoms.

- To ensure consistent potential alignment for future charged defect calculations:

- Set the origin to the vacancy location.

- Disable the

UpdateStdVecoption in expert settings to prevent system shifting.

- Maintain all other computational parameters identical to the perfect cell calculation.

Defective Structure Calculation:

- Run the DFT calculation with identical parameters to the perfect cell.

- Record the total energy (E_0 = -2099.94) eV [4].

Chemical Potential Reference:

- Calculate the carbon chemical potential reference as the energy per atom in the perfect diamond crystal: [ \muC = Ep / N_{\text{atoms}} = -2118.32 / 216 = -9.807 \text{ eV} ]

- This represents the energy cost of removing a carbon atom from the perfect diamond lattice [4].

Energy Calculation:

- Compute the neutral vacancy formation energy using: [ E^f0 = E0 - Ep + \muC = -2099.94 - (-2118.32) + (-9.807) = 8.57 \text{ eV} ]

- This value represents the energy required to form a neutral vacancy in diamond [4].

Protocol 2: Determining Thermodynamic Limits for Chemical Potentials in TiO₂

This protocol establishes the allowable range of chemical potentials for titanium and oxygen in rutile TiO₂ while maintaining thermodynamic stability [23].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Competeing Phases Identification:

- Identify all stable compounds in the Ti-O system: Ti, O₂, TiO₂_rutile, Ti₂O₃, TiO, Ti₃O₅.

- Calculate the formation energy per formula unit for each compound using consistent DFT parameters.

Formation Energy File Preparation:

- Create a text file (formation_energies.txt) with calculated formation energies:

Feasible Region Calculation:

- Use thermodynamic analysis tools (e.g., Spinney Python package) to process the formation energies.

- Define the equality constraint for rutile TiO₂ stability.

- The algorithm automatically determines the feasible region satisfying all thermodynamic constraints.

Chemical Potential Extremes Extraction:

- Extract the minimum and maximum values for each chemical potential: [ \Delta \mu\mathrm{O}: -3.53 \text{ eV to } 0 \text{ eV} ] [ \Delta \mu\mathrm{Ti}: -9.47 \text{ eV to } -2.41 \text{ eV} ]

- These ranges define the Ti-rich ((\Delta \mu\mathrm{O} = -3.53) eV) and O-rich ((\Delta \mu\mathrm{O} = 0) eV) limits [23].

Visualization and Validation:

- Plot the feasible region to visualize thermodynamic stability boundaries.

- Identify which competing phases define the boundaries of the feasible region.

- Verify that no single-element phases can precipitate within these chemical potential ranges.

Advanced Considerations for Specific Material Systems

Handling Doped Systems (e.g., Nb-doped TiO₂)

When introducing dopants into host materials, additional thermodynamic constraints must be considered. For Nb-doped TiO₂, you must account for competing Nb-containing phases [23]:

- Expand Phase Space: Include Nb, NbO₂, TiNb₂O₇, and other relevant Nb-O and Ti-Nb-O phases in your thermodynamic analysis.

- 3D Feasible Region: The chemical potential space becomes three-dimensional ((\Delta \mu\mathrm{O}), (\Delta \mu\mathrm{Ti}), (\Delta \mu_\mathrm{Nb})) with additional constraints.

- Dopant-Rich Limits: Under Nb-rich conditions ((\Delta \mu_\mathrm{Nb} = 0)), rutile TiO₂ may not be thermodynamically stable as NbO₂ would precipitate instead. This analysis helps determine optimal doping conditions [23].

Molecular Materials Considerations

Defect calculations in molecular materials require special attention to [21]:

- Anisotropic Charge Distributions: Molecules often have strong dipoles and anisotropic electron density, requiring specialized correction schemes for charged defects.

- Rotational Symmetry Reduction: Defects decrease the host material's rotational symmetry, leading to complex electrostatic environments.

- Molecular Reorganization Energy: The energy cost of molecular rearrangement around defects must be properly accounted for, beyond rigid molecule approximations.

The relationship between these advanced considerations is summarized below:

By implementing these protocols, troubleshooting guides, and advanced considerations, researchers can significantly improve the accuracy and reliability of their defect formation energy calculations, leading to more predictive materials design and more robust computational research outcomes.

A Toolkit for Accuracy: Methodologies for Correcting Defect Energetics

In the computational modeling of crystalline materials, the accurate prediction of defect formation energies is essential for understanding material properties. However, standard simulation techniques using periodic boundary conditions introduce significant unphysical artifacts when studying charged defects. These artifacts arise from spurious electrostatic interactions between the defect and its periodic images, as well as the use of an artificial compensating background charge [24]. Left uncorrected, these errors can lead to qualitatively incorrect predictions in defect concentrations and electronic behavior, undermining the reliability of computational materials design [25].

A posteriori correction schemes have emerged as crucial tools for addressing these limitations. These methods apply systematic corrections after the initial electronic structure calculation, enabling researchers to obtain accurate defect formation energies and defect level positions without prohibitive computational expense. This technical support center addresses the practical implementation challenges of these essential correction methodologies, providing troubleshooting guidance and experimental protocols for researchers working at the intersection of materials science and computational physics.

Understanding A-Posteriori Correction Methods

Historical Development and Key Methods

The evolution of a posteriori correction schemes has progressed from simple phenomenological approaches to increasingly sophisticated electrostatic models:

- Early Foundations: The Mott-Littleton method (1938) established continuum approaches for charged defect energetics, while the Makov-Payne correction (1995) provided early supercell corrections including monopole and quadrupole terms [25].

- Freysoldt-Neugebauer-Van de Walle (FNV) Scheme: This influential method enables accurate estimation of correction energy through alignment of the defect-induced potential to a model charge potential [26]. It combines image-charge correction with potential alignment procedures.

- Kumagai-Oba Extension: This advancement addresses two practical limitations of the FNV scheme by using atomic site electrostatic potentials as markers instead of planar-averaged potentials, and extending the approach to anisotropic materials through a point charge model in an anisotropic medium [26].

- Recent Self-Consistent Approaches: Newer methods move away from a posteriori corrections toward direct modification of the underlying self-consistent calculation, incorporating more physical long-range dielectric screening [25].

Table 1: Comparison of Major A-Posteriori Correction Methods

| Method | Key Innovation | Applicable Systems | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Makov-Payne | Early supercell correction including monopole & quadrupole terms | Bulk cubic systems | Requires determination of quadrupole moment; limited to isotropic materials |

| FNV Scheme | Potential alignment to model charge distribution | Bulk systems with isotropic dielectric response | Uses planar-averaged potential; assumes macroscopic dielectric constant |

| Kumagai-Oba | Atomic site potentials; anisotropic dielectric response | Anotropic materials; relaxed systems | Requires accurate atomic site potential calculation |

| CoFFEE Implementation | Generalized Poisson solver for multiple geometries | Bulk, 2D materials, nanowires, nanoribbons | Dependent on accuracy of model charge distribution |

The Correction Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow for applying a posteriori corrections to charged defect calculations:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Methodological Questions

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between the Freysoldt and Kumagai-Oba correction schemes?

The Freysoldt-Neugebauer-Van de Walle (FNV) scheme uses planar-averaged potentials for determining the potential offset and assumes long-range Coulomb interactions are screened by a macroscopic dielectric constant, which is valid primarily for cubic systems [26]. The Kumagai-Oba extension introduces two key improvements: (1) using atomic site electrostatic potentials as potential markers instead of planar-averaged potentials, which makes it applicable to relaxed systems where planar averaging is problematic, and (2) extending the scheme to anisotropic materials by adopting a point charge model in an anisotropic medium for estimating long-range interactions [26].

Q2: When should I use potential alignment corrections versus image-charge corrections?

The potential alignment correction is not an independent correction but is actually included within the image-charge correction framework. As demonstrated by Kumagai and Oba, the potential alignment corresponds to part of the first-order and the full third-order image-charge correction, meaning the third-order image-charge contribution is absent after potential alignment [26]. Therefore, modern implementations treat these as integrated components rather than separate corrections.

Q3: How do I handle charged defect corrections in low-dimensional systems like 2D materials or nanowires?

For low-dimensional systems, specialized approaches are required. The CoFFEE (Corrections For Formation Energy and Eigenvalues) package implements a generalized Poisson solver that can handle materials with varying dimensionalities [24]. For 2D systems (slabs, 2D materials) and 1D systems (nanowires, nanoribbons), the code numerically solves the Poisson equation with spatially varying dielectric profiles and extrapolates electrostatic energy to the isolated limit, as analytical solutions available for bulk systems may not apply.

Practical Implementation Questions

Q4: What are the most common sources of error when applying a posteriori corrections?

The most significant errors arise from: (1) inaccurate determination of the model charge distribution representing the defect, (2) improper potential alignment between defect and bulk systems, (3) using isotropic dielectric constants for anisotropic materials, and (4) insufficient supercell size leading to incomplete separation of defect interactions [26] [24]. The Kumagai-Oba method specifically addresses the anisotropic dielectric response issue, while careful potential alignment procedures mitigate the second concern.

Q5: How can I validate that my correction procedure is working correctly?

Several validation approaches are recommended: (1) Perform convergence tests with increasing supercell sizes to ensure corrections properly approach asymptotic values, (2) Compare results from different correction schemes where applicable, (3) For well-studied benchmark systems, compare with literature values, and (4) Use implementation packages like CoFFEE that have been tested on standard systems [24]. The correction should significantly reduce the dependence of formation energies on supercell size.

Q6: What computational tools are available for implementing these corrections?

The CoFFEE package provides a comprehensive implementation of the FNV correction scheme for charged defects in various material geometries including bulk, 2D materials, and nanowires [24]. The code is written in Python and features MPI parallelization for efficient computation. Other DFT packages may have built-in implementations, but CoFFEE offers the advantage of working across multiple material dimensionalities.

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Calculation Errors and Solutions

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Implementation Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solution Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Unphysical formation energies | Incorrect potential alignment; improper charge model | Verify potential reference points; check model charge distribution against defect wavefunction |

| Poor convergence with supercell size | Insufficient cell size; anisotropic effects not accounted for | Use larger supercells; employ anisotropic correction schemes like Kumagai-Oba |

| Discrepancies between different correction methods | Different treatment of dielectric response; varying alignment schemes | Standardize on one well-validated method; check for implementation errors |

| Inaccurate defect level positions | Uncorrected eigenvalue shifts; poor band gap description | Apply specific eigenvalue corrections; verify bulk band structure accuracy |

Optimization Strategies for Accurate Results

Supercell Size Selection: While corrections enable smaller supercells, careful convergence tests remain essential. For bulk systems, 100-atom supercells often provide reasonable accuracy after correction, but larger cells may be needed for delocalized defects [26].

Dielectric Constant Treatment: For anisotropic materials, always use the full dielectric tensor rather than an isotropic approximation. The Kumagai-Oba method specifically addresses this requirement [26].

Potential Alignment Validation: Compare potential alignment from multiple approaches - atomic site potentials (Kumagai-Oba) versus planar averages (FNV) - to identify potential inconsistencies in your implementation.

Charge Model Optimization: Ensure your model charge distribution (typically Gaussian) properly represents the actual defect charge distribution. Adjust the distribution width to match the defect characteristics.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Implementation Workflow for Charged Defect Corrections

The following protocol outlines the complete procedure for applying a posteriori corrections to charged defect formation energy calculations:

Pristine System Calculation: Compute the total energy of the pristine supercell and save the electrostatic potential in a standardized format (e.g., cube or xsf format) for reference [24].

Neutral Defect Calculation: Compute the total energy of the supercell containing the neutral defect with optimized atomic positions. Save the electrostatic potential using the same format and settings as the pristine calculation.

Charged Defect Calculation: Compute the total energy of the supercell containing the charged defect, including the appropriate uniform background charge. Save the electrostatic potential with identical parameters to previous calculations.

Model Charge Definition: Construct a model charge distribution representing the defect. Typically, a Gaussian distribution is used: ( \rho_{model}(r) = q(\alpha/\pi)^{3/2}exp(-\alpha r^2) ), where the width parameter α is optimized to match the actual defect charge distribution [24].

Potential Alignment: Calculate the potential alignment term by matching the defect-induced potential to the model potential in regions far from the defect core. The Kumagai-Oba method uses atomic site potentials rather than planar averages for this alignment [26].

Image-Charge Correction: Compute the energy correction using the expression: ( \Delta E = E{lat} - q\Delta V ), where ( E{lat} ) is the lattice energy for the model charge distribution and ( \Delta V ) is the potential alignment term [26] [24].

Formation Energy Calculation: Apply the correction to the raw DFT formation energy: ( E^f[X^q] = E^f{DFT}[X^q] + \Delta E ), where ( E^f{DFT}[X^q] ) is the uncorrected formation energy of defect X in charge state q.

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Defect Correction Research

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| CoFFEE Package | Implements FNV correction scheme for various geometries | Bulk, 2D, and 1D material systems |

| Atomic Site Potential Calculator | Computes reference potentials for alignment | Kumagai-Oba correction implementation |

| Generalized Poisson Solver | Numerically solves Poisson equation with anisotropic dielectrics | Low-dimensional and anisotropic systems |

| Model Charge Optimizer | Fits model charge distributions to actual defect density | Accurate representation of defect electrostatic properties |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Recent developments in a posteriori correction schemes are expanding their applicability and accuracy. Machine-learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) are now being integrated as MM models in hybrid QM/MM schemes, enabling more computationally efficient simulations while maintaining accuracy [27]. Novel adaptive QM/MM methods utilize residual-based error estimators that provide both upper and lower bounds for approximation errors, allowing for anisotropic updates of QM/MM partitions based on defect geometry [27].

The field is also moving toward more sophisticated self-consistent potential corrections that modify the underlying electronic structure calculation directly rather than applying a posteriori corrections [25]. These approaches, such as the self-consistent potential correction by da Silva et al. (2021) and the image charge correction by Suo et al. (2020), incorporate more physical screening responses directly during the calculation rather than as a post-processing step [25]. As these methodologies mature, they promise to further enhance the predictive power of computational materials design for both fundamental research and practical applications in materials science and drug development.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the primary cause of constant bias adjustments in multivariate calibration models? The need for constant bias adjustments is most often due to consistent spectral differences between instruments. These differences arise from variations in wavelength registration, photometric offset, and spectral linewidth (bandwidth). When calibration is transferred from a primary instrument to a secondary one, these consistent differences manifest as a bias, requiring a zero-order correction for each product and constituent model [28].

2. How do I correct for slope errors in my predictive model? Unlike bias, which is a simple offset, slope errors are often caused by fundamental changes in the spectral data, such as shifts in wavelength registration or changes in spectral linewidth [28]. Correcting a slope error requires more than a simple adjustment; it necessitates addressing the root cause of the spectral variation, which can sometimes be achieved by ensuring instruments have matching spectral characteristics or by using standardization algorithms [28].

3. What is the difference between a 'constant offset' and 're-calibrating the slope' in the context of model correction? A constant offset (or bias) is a zero-order correction that simply adds or subtracts a single value to align the average prediction with the reference. It treats all prediction values the same, regardless of their magnitude. Re-calibrating the slope is a first-order correction that involves adjusting both the slope and the intercept of the prediction. This corrects for proportional errors across the range of predicted values and addresses more fundamental, consistent spectral differences between instruments [28].

4. When should I use bias correction versus a full slope recalibration? Bias correction is suitable for addressing consistent, additive differences between instruments, such as a stable photometric offset. If the error in your predictions changes proportionally with the value of the constituent you are measuring (e.g., error increases with concentration), this indicates a slope error, and a full recalibration or instrument standardization is required [28].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Inaccurate Predictions After Transferring a Calibration Model

Problem: After moving a validated calibration model from your primary instrument to a secondary instrument, the predictions are consistently inaccurate.

Diagnosis and Solution:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Check for Bias: Predict a set of validation samples on both instruments and calculate the average difference in predictions. | A consistent, non-proportional difference across all samples indicates a simple bias [28]. |

| 2 | Apply Bias Correction: If a bias is found, subtract the mean prediction difference from all future predictions made on the secondary instrument. | Predictions from the secondary instrument should now align with the primary instrument's baseline [28]. |

| 3 | Check for Slope Error: Plot the predictions from the secondary instrument against those from the primary. | A non-unity slope in the correlation plot indicates a slope error that bias correction cannot fix [28]. |

| 4 | Re-calibrate the Slope: If a slope error is confirmed, more advanced calibration transfer techniques (e.g., Piecewise Direct Standardization - PDS) or a full recalibration on the secondary instrument may be necessary [28]. | The relationship between predictions from the two instruments should become 1:1. |

Issue: High Standard Error of Prediction (SEP)

Problem: Your model exhibits a high Standard Error of Prediction, making it unreliable.

Diagnosis and Solution Flowchart:

Quantitative Impact of Instrument Variation

The table below summarizes how specific instrument variations affect key prediction metrics, based on a univariate model with a constituent concentration of 15 units [28].

| Instrument Variation | Change in SEP | Change in Bias | Change in Slope |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelength Shift (+0.5 nm) | Large Increase | Change of ~ -0.7 units | Significant Effect |

| Photometric Offset (+0.10 AU) | Large Increase | Change of ~ +4.5 units | No Effect |

| Linewidth Increase (+1.8 nm) | Large Increase | Change of ~ -6.0 units | Significant Effect |

Experimental Protocol: Calculating Defect Formation Energy

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for calculating the neutral defect formation energy of a vacancy in diamond using Density Functional Theory (DFT), as derived from established first-principles calculations [4].

Objective

To compute the neutral vacancy formation energy (E⁰_f) in a diamond crystal using a supercell approach.

Methodology

1. Build the Perfect Supercell

- Software: Use a DFT engine such as BAND or Quantum ESPRESSO.

- Structure: Start with a conventional diamond unit cell.

- Supercell: Generate a 3x3x3 supercell of the conventional cell. This creates a 216-atom structure.

- Calculation: Run a single-point energy calculation (E_p) on this perfect supercell. Use a Good k-space quality setting (e.g., 3 k-points in each lattice direction) and the LDA exchange-correlation potential [4].

2. Create the Defective Supercell

- Modification: In the perfect supercell structure, delete a single carbon atom to create a vacancy, resulting in a 215-atom structure.

- Region Tagging (Optional but Recommended): Before deleting the atom, mark its position as a "region." This helps maintain consistent symmetry operators across calculations, which is critical for later charged defect calculations [4].

- Potential Alignment: Set the origin to the atom that will be deleted. Disable the

UpdateStdVecexpert option to prevent the system from being shifted in subsequent calculations, which is crucial for accurate potential alignment [4]. - Calculation: Run a single-point energy calculation (E_0) on this defective supercell using the same computational parameters as in Step 1 [4].

3. Determine the Carbon Chemical Potential (μ_C)

- The chemical potential represents the energy of an atom in its reservoir.

- For a carbon vacancy, the reference is the energy per atom in the perfect diamond crystal.

- Calculate μC as: μC = E_p / N, where N is the number of atoms in the perfect supercell (216) [4].

4. Calculate the Defect Formation Energy

- Use the following formula to compute the neutral vacancy formation energy:

E⁰f = E0 - Ep + μC

Where:

- E0 = Total energy of the defective supercell (215 atoms)

- Ep = Total energy of the perfect supercell (216 atoms)

- μC = Chemical potential of carbon (Ep / 216) [4]

Expected Results

Using a 3x3x3 supercell with the described protocol, you should obtain a neutral vacancy formation energy of approximately 8.57 eV [4]. The formation energy converges with larger supercell sizes, as shown in the table below.

| Supercell Size | Number of Atoms | Approximate Vacancy Formation Energy (eV) |

|---|---|---|

| 2x2x2 | 64 | Not Converged |

| 3x3x3 | 216 | 8.57 |

| 4x4x4 | 512 | ~ Converged |

| 5x5x5 | 1000 | Converged |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| DFT Software (BAND, Quantum ESPRESSO) | First-principles software used to calculate the total energy of perfect and defective crystal structures, which is the foundation for determining defect formation energies [4]. |

| Positron Annihilation Spectroscopy (PAS) | A non-destructive technique used to characterize vacancy-type defects in materials. It provides positron lifetimes and Doppler-broadening spectra, offering information about the size and environment of defects [29]. |

| Machine Learning (ML) Joint Model | A computational framework that integrates predictions of defect formation energies and band-edge properties. This enables high-throughput virtual screening of promising materials, such as dopable oxides for semiconductor applications [30]. |

| Chemical Potential (μ_i) | A reference energy for an atom of element i, representing its energy in a reservoir (e.g., its bulk solid phase). It is essential for calculating the energy cost of adding or removing atoms to form a defect [4]. |

The Rise of Universal Machine-Learning Interatomic Potentials (UMLIPs) for High-Throughput Screening

### 1. UMLIP Models and Their Performance

The table below summarizes key universal Machine-Learning Interatomic Potentials (UMLIPs) and their benchmarked performance on properties critical for defect formation energy calculations, such as phonon dispersion and structural relaxation [31].

| Model Name | Key Architectural Features | Performance on Energy (MAE) | Performance on Forces (MAE) | Phonon Prediction Accuracy | Key Considerations for Defect Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M3GNet [31] | Pioneering model using three-body interactions [31]. | Information missing | Information missing | Moderate | A foundational model; may struggle with highly distorted structures [31]. |

| CHGNet | Relatively small architecture (~400k parameters) [31]. | Higher error [31] | Reliable structural relaxation [31] | Information missing | Often requires an energy correction procedure for improved accuracy [31]. |

| MACE-MP-0 | Uses atomic cluster expansion for efficient message passing [31]. | Information missing | Information missing | High | Good balance of accuracy and computational efficiency [31]. |

| MatterSim-v1 | Builds on M3GNet, uses active learning for broader chemical space sampling [31]. | Information missing | Highly reliable structural relaxation [31] | Information missing | Designed for robust energy and force predictions on diverse structures [31]. |

| ORB | Combines smooth overlap of atomic positions with a graph network simulator [31]. | Information missing | Predicts forces as a separate output [31] | Information missing | Higher failure rate in structural relaxation; forces are not exact energy derivatives [31]. |

| eqV2-M | Utilizes equivariant transformers for higher-order representations [31]. | Information missing | Predicts forces as a separate output [31] | Information missing | Top-ranked but high failure rate in relaxation; caution advised for off-equilibrium structures [31]. |

### 2. Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details computational tools and datasets essential for developing and applying UMLIPs in high-throughput screening [31] [32].

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Relevance to Defect Energy Calculations |

|---|---|---|

| Materials Project Database [31] [32] | A comprehensive database of DFT-calculated crystal structures and properties. | Primary source of training data and a reference for thermodynamic stability (convex hull) against which defect formation energies are computed [32]. |

| GNoME Dataset [32] | A massive dataset of crystal structures discovered through scaled graph network learning. | Provides diverse atomic configurations for training robust potentials and expands the known chemical space for screening new host materials [32]. |

| VASP (Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package) [33] [31] | A software package for performing DFT calculations. | Used to generate high-fidelity training data (energies, forces) and to verify UMLIP predictions on defect structures [33]. |

| LAMMPS [34] | A widely-used molecular dynamics simulation package. | The primary engine for running large-scale molecular dynamics simulations using trained UMLIPs to study defect kinetics and evolution [34]. |

| MTP (Moment Tensor Potential) [34] | A type of MLIP known for a good balance between computational cost and accuracy. | Used in constructing specialized potentials capable of modeling complex defects like general grain boundaries with DFT accuracy [34]. |

### 3. Experimental Protocol: High-Throughput Screening of Defects with UMLIPs

This protocol outlines a workflow for using UMLIPs to screen for stable point defects in crystalline materials, with a specific focus on obtaining physically accurate formation energies.

Step 1: Candidate Generation and Model Selection

- Generate Defective Supercells: Create a set of supercells containing the point defects of interest (e.g., vacancies, interstitials, substitutions) in various charge states.

- Select a Suitable UMLIP: Choose a UMLIP model based on the target material and the required accuracy, referring to the performance benchmarks in Section 1. Models like MACE-MP-0 or MatterSim-v1 are often recommended for their reliability [31].

Step 2: Structural Relaxation with UMLIPs

- Perform Relaxation: Use the selected UMLIP to perform full structural relaxation of each defective supercell, minimizing the total energy and atomic forces.

- Convergence Check: Ensure the relaxation converges with forces below a stringent threshold (e.g., 0.005 eV/Å) to guarantee a valid local minimum on the potential energy surface [31]. Be aware that models predicting forces as a separate output (e.g., ORB, eqV2-M) can have higher failure rates at this stage [31].

Step 3: Energy Calculation and Post-Process Correction

- Calculate Uncorrected Energy: Compute the formation energy of the relaxed defect using standard formulas.