Controlling Nucleation: How Quenching Rates Dictate Nanoparticle Synthesis in Thermal Plasma

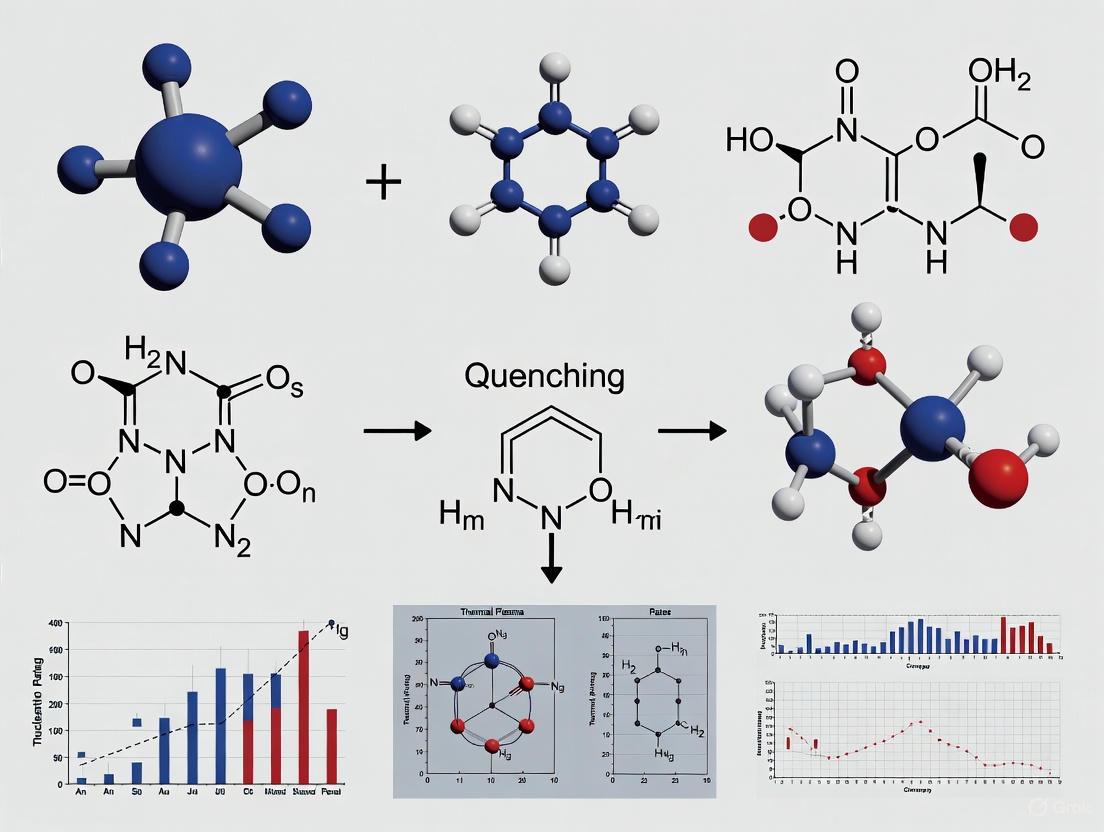

This article explores the critical role of quenching—the rapid cooling of a thermal plasma effluent—in controlling nucleation rates and the subsequent growth of nanoparticles.

Controlling Nucleation: How Quenching Rates Dictate Nanoparticle Synthesis in Thermal Plasma

Abstract

This article explores the critical role of quenching—the rapid cooling of a thermal plasma effluent—in controlling nucleation rates and the subsequent growth of nanoparticles. Tailored for researchers and scientists in drug development, we dissect the fundamental mechanisms through which quenching dictates particle size, distribution, and crystallinity. Building on this foundation, the review analyzes experimental and computational methodologies for implementing quenching, addresses common optimization challenges, and validates these strategies through direct comparisons with experimental data. The insights provided are pivotal for designing nanomedicines, drug delivery carriers, and other advanced materials with precise specifications.

The Nucleation Blueprint: Unraveling the Core Principles of Quenching in Thermal Plasmas

Defining the Quenching Process in Thermal Plasma Synthesis

In thermal plasma synthesis, the quenching process is the critical step that immediately follows the vaporization of precursor materials in a high-temperature plasma. This process rapidly cools the vapor, driving it into a supersaturated state that initiates nucleation and growth of nanoparticles. The rate and method of quenching directly determine key nanoparticle characteristics, including size, size distribution, and crystal phase, by effectively freezing the growth processes at a desired point [1] [2]. Controlling this step is therefore paramount for fabricating nanomaterials with tailored properties for advanced applications in catalysis, energy storage, and biomedicine. This guide provides a detailed comparison of the primary quenching strategies employed in research and industrial settings, supported by experimental data and methodologies.

Quenching Mechanisms and Performance Comparison

The primary quenching methods achieve rapid cooling through different physical mechanisms, each with distinct performance outcomes and implications for nanoparticle nucleation and growth. The table below summarizes these key characteristics for easy comparison.

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Quenching Methods in Thermal Plasma Synthesis

| Quenching Method | Physical Mechanism | Typical Cooling Rate | Impact on Nucleation & Growth | Resulting Nanoparticle Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas Injection / Mixing | Dilution and convective heat transfer via introduction of cold gas streams [3] [1]. | High | Rapid supersaturation leads to a high nucleation density, abruptly halting growth [1]. | Smaller average size, narrower size distribution [1]. |

| Conductive Cooling | Heat transfer to a cooled physical surface (e.g., a rod or chamber walls) [3]. | Variable (depends on design) | Slower cooling can allow for more growth time post-nucleation. | Larger average size compared to gas mixing. |

| Expansion Nozzle | Rapid adiabatic expansion and creation of fluid dynamic effects that enhance mixing [3]. | Very High (~107 K/s) [3] | Extremely fast cooling "freezes" the nanoparticle population. | Preserves initial nucleation burst, minimizing coagulation. |

The efficacy of quenching is quantitatively evident in its impact on nanoparticle populations. Computational studies modeling silicon nanoparticle synthesis demonstrate that at higher cooling rates, a greater proportion of the vapor is rapidly converted into a high density of nuclei. Following this initial nucleation burst, particle growth transitions to a much slower coagulation phase. Consequently, faster quenching yields a final product with a greater total number density, smaller average size, and smaller standard deviation [1].

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of Quenching on Silicon Nanoparticle Synthesis Outcomes [1]

| Parameter | Effect of Higher Cooling Rates |

|---|---|

| Vapor-to-Particle Conversion | Rapid conversion of 40–50% of vapor atoms. |

| Total Number Density | Increases. |

| Average Particle Size | Decreases. |

| Size Distribution (Standard Deviation) | Decreases. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Quenching Studies

Gas Injection Quenching for Silicon Nanoparticles

This protocol is used to study the direct effect of a quenching gas on nanoparticle growth [1].

- Objective: To investigate the effects of gas quenching on the growth processes and size distributions of silicon nanoparticles.

- Materials: Inductively Coupled Thermal Plasma (ICTP) torch system, argon plasma gas (G1 grade, <0.1 ppm O2), coarse silicon powder feed (∼7 µm, 99.99% purity), and quench gas (Argon, 80 L/min).

- Methodology:

- Plasma Generation & Precursor Injection: Argon plasma gas is introduced at 35 L/min to sustain the plasma. Silicon powder is fed into the plasma torch at 0.048 g/min using a carrier argon gas (3 L/min).

- Vaporization & Quenching: The silicon powder is vaporized in the high-temperature plasma (>10,000 K). The vapor is then transported to the plasma tail, where an additional argon gas stream is injected at 80 L/min towards the central axis, rapidly cooling the vapor stream.

- Analysis: The synthesized nanoparticles are collected and analyzed using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). Size distributions are measured by counting approximately 1200 nanoparticles from the SEM micrographs.

- Key Findings: The introduction of quenching gas was found to directly result in altered nanoparticle size distributions, validating models that show faster cooling produces smaller, more uniform particles [1].

Post-Plasma Reactive Quenching for CO2Conversion

This protocol explores a advanced quenching method where a cold gas is not just a coolant but also a reactant [4].

- Objective: To enhance CO2 conversion by injecting CH4 into the post-plasma afterglow to utilize residual heat and suppress reverse reactions.

- Materials: 2.45 GHz Microwave Plasma reactor, CO2 gas, CH4 gas.

- Methodology:

- Plasma Generation: A pure CO2 plasma is sustained at set pressure (e.g., 500 mbar) and power (e.g., 1250 W).

- Dual Injection Quenching: CH4 is injected directly into the hot post-plasma region (afterglow), rather than being premixed with the CO2 before the plasma.

- Analysis: The effluent gas is analyzed for CO2 and CH4 conversion, product selectivity (CO, H2), and syngas ratio (H2:CO). Chemical kinetics modeling is used to identify key reaction pathways.

- Key Findings: This reactive quenching approach achieved a CO2 conversion of ~55%. The mechanism enhances conversion by scavenging O atoms that would otherwise recombine with CO to form CO2, while the residual heat drives CH4 dissociation [4].

Visualization of Quenching Pathways and Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the logical flow of the quenching process and a specific experimental setup for reactive quenching.

Quenching Process Pathways

Diagram 1: Pathways from precursor to product, showing how different quenching methods influence growth.

Reactive Quenching Experiment

Diagram 2: Workflow for a dual-injection reactive quenching experiment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details essential materials and equipment used in thermal plasma synthesis and quenching experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Plasma Quenching Studies

| Item | Function / Role in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Precursor Materials (e.g., Coarse Silicon Powder [1], CO2/CH4 gases [4]) | The raw material to be vaporized in the plasma for nanoparticle synthesis or gas conversion. |

| Plasma Gases (e.g., Argon [1]) | An inert gas used to generate and sustain the high-temperature thermal plasma. |

| Quenching Gases (e.g., Argon [1], CH4 [4], N2 [4]) | Injected to rapidly cool the vapor. Can be inert (physical quenching) or reactive (chemical quenching). |

| Thermal Plasma System (e.g., Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) [1], DC Plasma Jet [1], Microwave Plasma [4]) | The core apparatus that generates the high-temperature environment for vaporizing precursors. |

| Quenching Gas Injector / Nozzle [1] | A precisely designed port or nozzle for introducing the quenching gas into the vapor stream to ensure rapid and uniform mixing. |

| Cooled Probes or Walls (e.g., water-cooled rod/coil [3] [1]) | A physical surface actively cooled by a circulating fluid (e.g., water) to remove heat via conduction from the effluent. |

| Analytical Instruments (e.g., SEM, UV-Vis Spectrometer, FT-IR [1] [5]) | Used to characterize the final products (nanoparticle size, morphology, chemical composition, and gas conversion efficiency). |

The choice of quenching method is a decisive factor in thermal plasma synthesis, directly governing nucleation rates and the ultimate properties of synthesized nanomaterials. As evidenced by the experimental data, gas injection and reactive quenching offer superior control for producing small, monodisperse nanoparticles and enhancing gas conversion efficiencies compared to slower conductive cooling methods. The ongoing refinement of quenching strategies, particularly reactive quenching which utilizes residual post-plasma energy, is pivotal for advancing the scalability and economic viability of plasma-based nanomaterial fabrication and chemical production.

Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) and the Thermodynamic Drive

Within the broader thesis investigating the effect of quenching on nucleation rates in thermal plasma research, understanding the fundamental drivers of phase transition is paramount. This guide compares the predictive performance of Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) against modern computational alternatives, focusing on the central role of the thermodynamic drive.

Theoretical Comparison: CNT vs. Alternative Models

Classical Nucleation Theory provides a foundational framework for estimating nucleation rates by considering the balance between the thermodynamic drive for phase formation and the energy penalty for creating a new interface. The key equation for the homogeneous nucleation rate, J, is:

J = K exp(-ΔG*/kBT)

where ΔG* is the free energy barrier, kB is Boltzmann's constant, T is temperature, and K is a kinetic pre-factor. The thermodynamic drive is primarily captured by the Gibbs free energy difference, ΔGv, between the parent and new phase.

Alternative models, such as Density Functional Theory (DFT) and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, offer a more granular, atomistic perspective.

Comparison of Predictive Performance for Nucleation Rates

Table 1: Comparison of Theoretical Models for Nucleation Rate Prediction

| Model | Theoretical Basis | Pros | Cons | Typical Agreement with Experiment (Log J) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) | Macroscopic thermodynamics (capillarity approximation) | Simple, analytical, provides physical intuition. | Often underestimates rates; assumes bulk properties for small clusters. | ± 5 to 10 orders of magnitude |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Electronic structure and statistical mechanics | More accurate for small clusters; no empirical parameters. | Computationally intensive; limited to small system sizes and timescales. | ± 2 to 5 orders of magnitude |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations | Classical interatomic potentials | Directly models atomic motion and cluster dynamics. | Limited by timescale (requires enhanced sampling); accuracy depends on the potential. | ± 1 to 3 orders of magnitude |

Supporting Experimental Data in a Quenching Context

Experimental validation in thermal plasma synthesis, where rapid quenching creates high supersaturation, is challenging. The following table summarizes data from a model system (solidification of nickel from the melt) under controlled quenching conditions, comparing measured nucleation rates with model predictions.

Table 2: Experimental vs. Predicted Nucleation Rates for Nickel Undercooling

| Undercooling, ΔT (K) | Experimental J (m⁻³s⁻¹) | CNT Prediction J (m⁻³s⁻¹) | MD Simulation J (m⁻³s⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 300 | 1.0 x 10²⁵ | 2.5 x 10¹⁹ | 5.8 x 10²³ |

| 350 | 5.0 x 10²⁹ | 3.1 x 10²⁴ | 1.2 x 10²⁹ |

| 400 | 2.5 x 10³³ | 1.5 x 10²⁸ | 9.5 x 10³² |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Electromagnetic Levitation (EML) for Undercooling Experiments This method is used to gather benchmark data, as cited in Table 2.

- Sample Preparation: A high-purity spherical sample (e.g., Ni) is placed in an EML chamber.

- Melting & Levitation: The chamber is evacuated and back-filled with high-purity inert gas (He/Ar mixture). The sample is melted and positioned contact-free via electromagnetic fields.

- Quenching & Undercooling: The heating power is rapidly reduced, leading to a controlled quench. The sample's temperature is monitored via a pyrometer.

- Nucleation Event Detection: The recalescence event (a sudden temperature increase due to the release of latent heat) marks the nucleation point. The undercooling (ΔT) is recorded.

- Statistical Analysis: The nucleation rate is calculated from the statistics of undercooling achieved over multiple experimental runs.

Protocol 2: Seeding Method for CNT Parameter Calibration This protocol helps calibrate the interfacial energy parameter in CNT using experimental data.

- Generate Baseline Data: Obtain nucleation rates (J) vs. undercooling (ΔT) for a pure substance using EML (Protocol 1).

- CNT Fitting: Use the CNT equation for solidification, where the thermodynamic drive ΔGv is a function of ΔT. The interfacial energy (σ) is treated as a fitting parameter.

- Parameter Extraction: Adjust σ until the CNT prediction curve best fits the experimental J(ΔT) data. This calibrated σ can then be used for predictions in more complex systems.

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

CNT Nucleation Pathway

Quenching Enhances Nucleation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Nucleation Rate Experiments

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Metal Spheres (e.g., Ni, Zr) | Model systems with well-characterized thermodynamic properties for benchmarking theories. |

| Inert Process Gas (He, Ar, He/Ar mix) | Creates a contamination-free environment in levitation experiments to prevent heterogeneous nucleation. |

| Electromagnetic Levitator (EML) | Provides containerless processing to achieve deep undercooling by eliminating crucible-induced nucleation. |

| High-Speed Pyrometer | Accurately measures sample temperature and detects the rapid recalescence event signaling nucleation. |

| Classical Nucleation Theory Code/Software | Enables rapid calculation of expected nucleation rates and energy barriers for comparison with data. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software (e.g., LAMMPS) | Allows for atomistic simulation of nucleation events, providing insights beyond CNT's limitations. |

The Critical Role of Supersaturation in Particle Monomer Formation

Supersaturation represents a critical non-equilibrium state in which a solution contains a solute concentration that exceeds its thermodynamic solubility, yet the solute remains soluble for an extended period due to a high free-energy barrier to nucleation [6]. This metastable condition serves as the fundamental driving force for phase transitions across diverse scientific domains, from the formation of crystalline materials and pharmaceutical compounds to the pathological assembly of amyloid fibrils and the synthesis of advanced nanoparticles [6] [1]. The breakdown of supersaturation triggers nucleation and subsequent growth processes that determine the final characteristics of the formed particles, including their size, size distribution, and crystalline structure.

In thermal plasma research, the controlled manipulation of supersaturation through quenching strategies represents a powerful tool for directing nucleation rates and controlling particle monomer characteristics. As vapor experiences rapid temperature decreases in thermal plasma tails, it enters a supersaturated state that drives the homogeneous nucleation of nanoparticles [1]. Understanding and controlling this phenomenon is essential for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to engineer particles with precise specifications for applications ranging from lithium-ion battery electrodes to targeted drug delivery systems.

Theoretical Framework: Supersaturation and Nucleation Kinetics

Quantitative Definition and Phase Behavior

Supersaturation is quantitatively defined using two key parameters: the supersaturation ratio (S) and the degree of supersaturation (σ) [6]:

- Supersaturation ratio: S = [C]/[C]C

- Degree of supersaturation: σ = ([C] - [C]C)/[C]C

where [C] represents the initial solute concentration and [C]C denotes the thermodynamic solubility. These parameters determine the position within a phase diagram that delineates distinct regions of solution behavior, as illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1: Phase Diagram Regions for Protein Solvency Based on Precipitant Concentration

| Region | Designation | Physical State | Nucleation Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Region I | Soluble Region | Monomers are thermodynamically stable | No nucleation occurs |

| Region II | Metastable Region | Supersaturation persists without seeding or agitation | Nucleation requires seeding |

| Region III | Labile Region | Spontaneous nucleation occurs | Nucleation occurs after a lag time |

| Region IV | Amorphous Region | Amorphous aggregation dominates | Immediate aggregation without lag time |

The driving force for nucleation is proportional to lnS, while the nucleation rate exhibits an inverse relationship with the lag time observed before particle formation begins [6]. This theoretical framework provides the foundation for understanding how experimental conditions influence nucleation kinetics and particle characteristics.

Kinetics of Nucleation Under Increasing Supersaturation

The kinetics of homogeneous nucleation-growth processes under increasing supersaturation reveal complex behaviors that depend on the rate at which external parameters change. Analytical expressions describing the dependence of supercritical cluster numbers on both the rate of supersaturation change and time indicate that two distinct nucleation regimes exist [7]:

- Thermal nucleation dominates at moderate rates of supersaturation increase

- Athermal nucleation becomes predominant at higher rates of change

In the thermal nucleation regime, the onset of nucleation-growth processes (defined as the minimum supersaturation required for intensive nucleation) depends logarithmically on the rate of supersaturation increase [7]. This relationship has profound implications for designing quenching protocols in thermal plasma systems, where cooling rates directly impact nucleation thresholds.

Supersaturation Pathway to Nucleation: This diagram illustrates the transition through phase regions during particle formation, highlighting critical decision points between ordered nucleation and amorphous aggregation.

Experimental Evidence: Quenching Effects in Thermal Plasma Systems

Silicon Nanoparticle Fabrication: A Case Study

Experimental investigations into silicon nanoparticle formation using inductively coupled thermal plasma (ICTP) systems have revealed how quenching strategies dramatically impact nanoparticle characteristics. In these systems, coarse silicon powder (approximately 7 μm particle size, 99.99% purity) is introduced through a feeder nozzle into the plasma torch with carrier argon gas [1]. The material vaporizes in the high-temperature plasma (approximately 10,000 K) and then experiences rapid temperature decreases in the plasma tail, triggering supersaturation and subsequent nanoparticle formation.

When quenching is applied, additional argon gas is injected from the lower part of the torch toward the central axis at 80 L min⁻¹, substantially altering the cooling rate and consequent nucleation dynamics [1]. The experimental outcomes, validated through scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis of approximately 1200 nanoparticles per condition, demonstrate clear quenching effects on particle size distributions as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Experimental Outcomes of Silicon Nanoparticle Fabrication With and Without Quenching

| Experimental Condition | Total Number Density | Mean Particle Size | Size Distribution Width | Primary Growth Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without Quenching | Lower | Larger | Broader | Condensation-dominated |

| With Quenching (80 L min⁻¹ Argon) | Higher | Smaller | Narrower | Coagulation-dominated |

Computational Modeling of Growth Processes

Computational studies using nodal-type models (classified as Type D in aerosol dynamics modeling) have provided crucial insights into the implicit mechanisms governing nanoparticle growth under different quenching conditions [1]. These models express size distributions evolving temporally with simultaneous homogeneous nucleation, heterogeneous condensation, interparticle coagulation, and melting point depression. The numerical simulations reveal that:

- In highly supersaturated states, 40-50% of vapor atoms rapidly convert to nanoparticles via homogeneous nucleation

- After vapor atom consumption, nanoparticle growth continues through coagulation at a much slower rate than initial condensation

- Higher cooling rates produce greater total number densities, smaller mean sizes, and reduced standard deviations in size distributions

The modeling results further demonstrate that quenching presents limitations for controlling nanoparticle characteristics, as the rapid temperature decrease primarily affects the initial nucleation burst rather than subsequent growth phases [1].

Comparative Analysis: Quenching Methods and Outcomes

Quenching Strategies in Thermal Plasma Systems

Various quenching approaches have been developed to control temperature and flow fields in thermal plasma systems, each with distinct effects on supersaturation development and nanoparticle characteristics. Experimental studies have implemented multiple strategies, each inducing different cooling rates and consequent nucleation dynamics as summarized in Table 3.

Table 3: Comparison of Quenching Methods in Thermal Plasma Nanoparticle Fabrication

| Quenching Method | Implementation Approach | Effect on Cooling Rate | Impact on Nanoparticle Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water-cooled coil | Convective cooling at plasma boundary | Moderate increase | Moderate reduction in mean size |

| Water-cooled ball | Direct insertion into plasma tail | High increase | Significant size reduction, narrower distribution |

| Pulse modulation | Periodic power variation | Cyclic variation | Controlled crystallinity, complex size distributions |

| Counterflow injection | Opposing gas flow to plasma | High increase | Substantial number density increase, smaller sizes |

| Radial gas injection | Perpendicular gas injection | Moderate increase | Moderate refinement of size distribution |

These quenching methods directly manipulate the development of supersaturation by controlling the temperature decrease rate at the plasma tail, thereby influencing the nucleation rate and subsequent growth processes [1]. The selection of an appropriate quenching strategy depends on the desired nanoparticle characteristics and the specific material system being processed.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Supersaturation and Nucleation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| β2-microglobulin (β2m) | Model amyloidogenic protein for studying fibril formation | Investigation of supersaturation role in amyloidosis [6] |

| Hen Egg White Lysozyme (HEWL) | Model protein for crystallization and amyloid formation studies | Analysis of supersaturation breakdown mechanisms [6] |

| HANABI System | High-throughput analysis of amyloid fibril formation | Ultrasonication-triggered supersaturation breakdown studies [6] |

| Argon Quenching Gas | Inert cooling medium for thermal plasma systems | Manipulation of cooling rates in nanoparticle synthesis [1] |

| Silicon Powder (99.99%) | High-purity precursor for nanoparticle fabrication | Model system for studying quenching effects on growth processes [1] |

Implications for Pharmaceutical Research and Drug Development

The principles governing supersaturation and quenching effects in thermal plasma systems find important parallels in pharmaceutical research, particularly in the context of amyloid diseases and drug formulation. In Alzheimer's disease research, cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of amyloid β(1-42) peptide decline 25 years before expected symptom onset and 15 years before amyloid deposition [6]. Similar decreases in α-synuclein concentration occur in Parkinson's disease [6]. The supersaturation hypothesis provides a physical explanation for these observations: the breakdown of supersaturation decreases soluble peptide concentrations concomitantly with amyloid fibril deposition.

Understanding quenching effects on nucleation rates enables drug development professionals to design better inhibitors of pathological protein aggregation by targeting the supersaturation maintenance phase rather than attempting to reverse established aggregation. Furthermore, the principles of controlled supersaturation breakdown find application in pharmaceutical crystallization processes, where quenching strategies can be employed to produce drug particles with specific size distributions and bioavailability characteristics.

Quenching Effect on Nanoparticle Formation: This workflow diagrams the sequential process from vaporization to final particle formation, highlighting how rapid quenching triggers supersaturation and subsequent growth mechanisms.

The critical role of supersaturation in particle monomer formation represents a unifying principle across diverse fields from materials science to pharmaceutical research. Experimental evidence from thermal plasma systems demonstrates that quenching strategies, which directly manipulate supersaturation development, enable significant control over nucleation rates and particle characteristics. Specifically, higher cooling rates produce greater nanoparticle number densities, smaller sizes, and narrower size distributions by affecting the initial nucleation burst in highly supersaturated states.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these insights provide valuable frameworks for designing experimental protocols aimed at controlling particle formation. The parallels between nanoparticle synthesis and pathological protein aggregation suggest that fundamental principles of supersaturation and nucleation kinetics can inform therapeutic strategies for amyloid diseases while guiding the development of advanced drug delivery systems. Future research integrating real-time monitoring of supersaturation states with controlled quenching protocols promises to enhance our ability to engineer particles with precision-tailored properties for specific applications.

How Cooling Rate Directly Influences Nucleation Rate and Critical Cluster Size

This guide examines the direct influence of cooling rate on nucleation kinetics and critical cluster formation, a fundamental relationship governing material synthesis in thermal plasma processing. Rapid quenching during thermal plasma synthesis is a critical control parameter for manipulating nanoparticle characteristics, including size distribution, crystallinity, and phase composition. We compare experimental data across multiple material systems—including silicon nanoparticles, graphene, and metallic glasses—to provide researchers with quantitative insights for optimizing nanomaterial fabrication protocols. The analysis reveals that increased cooling rates systematically elevate nucleation rates while reducing critical cluster sizes, enabling precise morphological control in advanced material design.

In thermal plasma synthesis, precursor materials are vaporized at extremely high temperatures (approximately 10,000 K) before undergoing rapid cooling or "quenching" in the plasma tail region [1]. This quenching process creates a supersaturated vapor where nucleation—the initial formation of stable particulate matter from vapor-phase atoms—becomes thermodynamically favorable [1] [8]. The cooling rate directly controls the supersaturation level, which is the primary driving force for nucleation events [9]. Understanding the quantitative relationship between cooling rate and nucleation parameters is essential for controlling product characteristics in applications ranging from silicon nanoparticle anodes for lithium-ion batteries to graphene flakes for electronic devices [1] [10].

Theoretical frameworks, particularly Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT), provide the mathematical foundation for describing these relationships. According to CNT, the nucleation rate (J), defined as the number of nuclei formed per unit volume per unit time (m⁻³s⁻¹), follows an Arrhenius-type relationship with the system's free energy landscape [9]. This relationship is formally expressed as:

J = A · exp(-ΔGcrit / kBT) [9]

where A is a pre-exponential factor incorporating kinetic parameters, kB is Boltzmann's constant, T is absolute temperature, and ΔGcrit represents the free energy barrier for forming stable nuclei [9]. The cooling rate influences both the exponential term by altering supersaturation and the pre-exponential factor through temperature-dependent molecular attachment frequencies [9].

Theoretical Framework: Cooling Rate Effects on Nucleation Parameters

Critical Cluster Size and Energy Barrier

The critical cluster size (r*) represents the minimum cluster dimension that remains stable without spontaneous dissolution [9]. This parameter is inversely related to the degree of supersaturation (S), which increases dramatically under rapid cooling conditions. According to CNT derivations for spherical nuclei, the free energy barrier is expressed as:

ΔGcrit = (16πγ³υ²) / (3(kBT ln S)²) [9]

where γ represents the surface tension at the crystal-liquid interface, and υ is the molecular volume [9]. Since rapid cooling produces elevated supersaturation (S), the denominator increases substantially, thereby reducing the activation barrier for nucleation. A lower energy barrier enables more clusters to achieve stability, resulting in a higher nucleation density and finer particulate morphology [9] [1].

For researchers applying these principles, the functional relationship implies that a doubling of supersaturation through controlled quenching reduces the critical cluster size by approximately a factor of two, based on the inverse square relationship present in the denominator of the ΔGcrit equation [9]. This quantitative understanding allows for predictive design of nucleation conditions.

Quantitative Nucleation Rate Model

The overall nucleation rate incorporates both thermodynamic and kinetic factors, with the pre-exponential factor A expressed as:

A = Z f* Cns [9]

where Z is the Zeldovich factor (typically 0.01-1), f* represents the molecular attachment frequency, and Cns is the concentration of nucleation sites [9]. The attachment frequency is particularly sensitive to temperature, which is directly controlled by the cooling rate in thermal plasma systems [9].

Experimental validation of these relationships often involves plotting ln J against T⁻¹, which theoretically produces a linear relationship with a slope of -ΔGcrit/kB, allowing researchers to extract the free energy barrier directly from experimental data [9]. However, as noted by Mullin (2001), this relationship may not be perfectly linear because ΔGcrit itself is temperature-dependent [9].

Table 1: Theoretical Relationships Between Cooling Rate and Nucleation Parameters

| Nucleation Parameter | Mathematical Expression | Effect of Increased Cooling Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleation Rate (J) | J = A · exp(-ΔGcrit/kBT) | Increase [9] |

| Critical Cluster Size (r*) | Decreases with rising supersaturation | Decrease [9] [1] |

| Free Energy Barrier (ΔGcrit) | ΔGcrit ∝ 1/(ln S)² | Decrease [9] |

| Supersaturation (S) | S = P/Peq | Increase [1] |

Comparative Experimental Data Across Material Systems

Silicon Nanoparticle Synthesis

In silicon nanoparticle fabrication using inductively coupled thermal plasma (ICTP), controlled quenching through additional gas injection demonstrates clear cooling rate effects. Experimental measurements show that approximately 40-50% of vapor atoms rapidly convert to nanoparticles during high supersaturation conditions, with subsequent growth occurring through slower coagulation processes [1].

Table 2: Cooling Rate Effects on Silicon Nanoparticles in Thermal Plasma Synthesis

| Cooling Rate Condition | Total Number Density | Average Size | Size Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Higher Cooling Rate | Greater | Smaller | Smaller standard deviation [1] |

| Lower Cooling Rate | Lower | Larger | Larger standard deviation [1] |

Computational modeling of these systems using nodal-type approaches (Model Type D) confirms that increased cooling rates produce greater total number densities of nanoparticles with reduced average diameters and narrower size distributions [1]. This occurs because rapid quenching generates more nucleation sites simultaneously, consuming available vapor atoms before significant growth can occur through condensation or coagulation [1].

Graphene Formation in Plasma Systems

In plasma-based graphene synthesis, quenching rate significantly influences morphology and structural quality. Without active quenching, the products primarily consist of spherical carbon nanoparticles and amorphous carbon structures [10]. With the introduction of controlled quenching, the product morphology shifts toward graphene flakes with reduced layer numbers and improved crystallinity [10].

Reactive force field (ReaxFF) molecular dynamics simulations reveal the atomic-scale mechanisms behind this transformation. Increased quenching rates rapidly lower growth temperatures, which retards C–H bond breakage at carbon cluster edges [10]. These intact C–H bonds terminate further C–C bond formation, preventing structural bending and promoting the formation of planar graphene structures rather than curved fullerenes [10]. The resulting materials exhibit fewer structural defects and enhanced oxidation resistance, critical parameters for electronic applications [10].

Polyamide 11 Crystallization

While not a plasma process, research on rotational molding of Polyamide 11 for hydrogen storage liners provides additional insights into cooling rate effects on crystallinity. Slower cooling processes produce higher crystallinity in the final material [11]. This increased crystallinity significantly improves barrier properties, with gas permeability coefficients 2-3 times lower than materials with low crystallinity [11]. These findings demonstrate that cooling rate management provides a critical control parameter for tailoring functional material properties across diverse applications.

Experimental Protocols for Thermal Plasma Quenching Studies

Silicon Nanoparticle Synthesis with Quenching

Objective: To investigate quenching effects on silicon nanoparticle growth processes and size distributions at cooling rates typical in thermal plasma tails [1].

Materials and Equipment:

- Inductively Coupled Thermal Plasma (ICTP) torch and reaction chamber [1]

- Coarse silicon powder (approx. 7 μm particle size, 99.99% purity) as precursor material [1]

- Argon gas (G1 grade, <0.1 ppm oxygen) as plasma and carrier gas [1]

- Quenching gas injection system for radial gas introduction [1]

- Powder feeding system (e.g., TP-99010FDR) with controlled feed rate [1]

- Scanning Electron Microscope (e.g., JSM-7800F) for size distribution analysis [1]

Methodology:

- Plasma Stabilization: Fill the main chamber with argon at 100 kPa, then inject argon continuously at 35 L/min from the torch top to sustain plasma [1].

- Precursor Introduction: Introduce coarse silicon powder through a feeder nozzle at 0.048 g/min with carrier argon gas (3 L/min) [1].

- Quenching Application: For quenched conditions, inject additional argon radially from the lower torch section toward the central axis at 80 L/min [1].

- Product Collection: Use a water-cooled collection chamber to capture synthesized nanoparticles [1].

- Size Characterization: Analyze approximately 1200 nanoparticles via SEM micrographs to determine size distributions [1].

Computational Modeling: Implement a nodal-type model (Type D) that expresses size distribution evolution through simultaneous homogeneous nucleation, heterogeneous condensation, and interparticle coagulation [1]. Discretize particle sizes using a geometric progression (vk+1 = 1.16vk) with kmax = 161 nodes [1]. Solve the population balance for each node to track nucleation and growth dynamics [1].

Graphene Synthesis with Modulated Quenching

Objective: To analyze the effects of quenching rate on the plasma gas-phase synthesis of graphene flakes [10].

Materials and Equipment:

- Magnetically rotating arc plasma system with rod cathode and annular anode [10]

- Acetylene gas as carbon precursor [10]

- Quenching gases of varying flow rates and compositions (argon, hydrogen mixtures) [10]

- Water-cooled collection chamber [10]

- Transmission Electron Microscope for morphological characterization [10]

Methodology:

- Plasma Operation: Generate plasma using a rod cathode (8mm diameter) and annular anode (30mm inner diameter) with an applied axial magnetic field [10].

- Precursor Pyrolysis: Introduce acetylene gas into the high-temperature plasma region for pyrolysis [10].

- Controlled Quenching: Modulate quenching rate using radial gas injection with varying flow rates and gas compositions in the plasma downstream [10].

- Product Analysis: Characterize products using TEM imaging to determine morphological evolution from spherical particles to graphene flakes [10].

- Molecular Dynamics Simulation: Complement experimental work with ReaxFF simulations to track formation pathways, focusing on five/six/seven-membered ring evolution and C–H bond dynamics [10].

Research Reagent Solutions for Nucleation Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Thermal Plasma Nucleation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Silicon Powder | Precursor material for nanoparticle synthesis | Silicon nanoparticle fabrication in ICTP [1] |

| Acetylene Gas | Carbon source for graphene formation | Plasma gas-phase synthesis of graphene flakes [10] |

| Argon Gas (G1 Grade) | Plasma working gas and quenching medium | Creates inert atmosphere for silicon nanoparticle synthesis [1] |

| Iron Silicate Particles | Analog for meteoric smoke in heterogeneous nucleation studies | Simulation of atmospheric ice nucleation conditions [12] |

| Polyamide 11 Resin | Model polymer for crystallization studies | Investigating cooling rate effects on crystallinity [11] |

| Monosilane (SiH₄) | Precursor for silicon nanoparticle synthesis | Microwave plasma reactor nanoparticle production [8] |

Visualization of Cooling Rate Effects

Theoretical Relationships Diagram

Experimental Workflow for Quenching Studies

The experimental data and theoretical frameworks presented demonstrate that cooling rate serves as a fundamental control parameter in thermal plasma synthesis, directly governing nucleation rate and critical cluster size through its influence on vapor supersaturation. Higher cooling rates consistently produce elevated nucleation densities and reduced particle sizes across diverse material systems, from silicon nanoparticles to graphene flakes. These relationships enable researchers to strategically manipulate quenching conditions to achieve targeted material properties, including crystallinity, size distribution, and morphological characteristics. The experimental protocols and computational approaches outlined provide a methodological foundation for systematic investigation of cooling rate effects in advanced material synthesis.

In thermal plasma research, quenching is a critical process step that abruptly halts particle growth by rapidly cooling the high-temperature plasma effluent. This process directly controls the nucleation and growth kinetics of synthesized materials, directly influencing critical characteristics such as particle size, size distribution, crystallinity, and morphology [1]. The quenching rate—the speed at which the system is cooled—can be manipulated to steer these material properties toward desired outcomes. Rapid quenching typically involves extreme cooling rates, often achieved through gas injection or contact with cooled surfaces, to "freeze" the material's state. In contrast, gradual cooling allows for a more prolonged period where particles can form and grow under thermodynamically favorable conditions [13]. The choice between these approaches represents a fundamental trade-off between kinetic control and thermodynamic equilibrium, making the understanding of their contrasting effects essential for researchers designing nanoparticle synthesis protocols.

The following tables synthesize experimental data from multiple studies, highlighting the direct impact of quenching rate on material characteristics in thermal plasma synthesis.

Table 1: Impact of Quenching Rate on Nanoparticle Characteristics

| Material System | Quenching Condition | Primary Outcome | Key Quantitative Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silicon Nanoparticles [1] | Rapid Quenching | Smaller, more uniform particles | Higher total number density, smaller average size, smaller standard deviation. |

| No/Gradual Quenching | Larger particles | Broader size distribution, continued particle growth via coagulation. | |

| Carbon-based Materials [10] | High Quenching Rate | Graphene flakes | Increased graphene content, fewer layers (3-8), reduced amorphous carbon, better crystallinity. |

| Low Quenching Rate | Spherical carbon nanoparticles | Formation of amorphous carbon and onion-like carbon structures. | |

| Zinc Oxide Powders [13] | Rapid Quenching | Conventional small powders | Not explicitly quantified in abstract. |

| Gradual, Regulated Quenching | Enhanced size characteristics | Significantly improved powder properties, effective control over characteristics. |

Table 2: Characteristics of Metallic Glasses Formed at Different Cooling Rates

| Glass Type | Critical Cooling Rate | Critical Heating Rate | Structural Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Doped Glass (SDG) [14] | ~500 K s⁻¹ | ~20,000 K s⁻¹ | Contains quenched-in nuclei or nucleation precursors. |

| Chemically Homogeneous Glass (CHG) [14] | ~4000 K s⁻¹ | ~6000 K s⁻¹ | No quenched-in structures; more homogeneous. |

Underlying Mechanisms and Pathways

The contrasting outcomes from rapid and gradual quenching stem from their direct influence on nucleation and growth pathways, as illustrated below.

Nucleation and Growth Dynamics

The pathway begins when material vapor in the thermal plasma is transported to the plasma tail, experiencing a rapid temperature decrease that leads to a supersaturated state [1]. In this state, the vapor has exceeded its equilibrium concentration, creating a powerful driving force for particle formation.

Rapid Quenching Effects: Under high cooling rates, the system enters a period of intense massive homogeneous nucleation, where a vast number of critical nuclei form simultaneously from the vapor phase [1]. This is quickly followed by heterogeneous condensation, where remaining vapor condenses onto existing nuclei. The rapid temperature drop quickly terminates the condensation process and limits the time available for interparticle coagulation, effectively "freezing" the nanoparticle population in a state characterized by high number density, small size, and narrow size distribution [1]. For carbon nanomaterials, this rapid cessation of growth prevents structural bending at the edges, favoring the formation of flat graphene flakes over spherical particles [10].

Gradual Quenching Effects: Slower cooling rates produce markedly different dynamics. The initial homogeneous nucleation event is less extensive, creating fewer critical nuclei [13]. These nuclei then undergo extended growth through both heterogeneous condensation and, importantly, interparticle coagulation, where smaller particles collide and merge to form larger ones [1]. This coagulation phase occurs much more slowly than condensation but becomes the dominant growth mechanism once most vapor atoms have been consumed [1]. The result is a population of larger particles with broader size distributions. For metallic alloys, gradual cooling enables the formation of quenched-in nuclei or nucleation precursors within the glassy matrix, creating what is termed a self-doped glass [14].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Plasma Synthesis with Active Quenching

This protocol details the experimental approach for investigating quenching effects in thermal plasma nanoparticle synthesis, as derived from silicon nanoparticle research [1].

- System Setup: The experiment utilizes an inductively coupled thermal plasma (ICTP) torch and reaction chamber. The system is filled with high-purity argon gas at 100 kPa. Argon plasma sustainer gas is injected continuously at 35 L/min.

- Feedstock Introduction: Coarse silicon powder (approximately 7 μm particle size, 99.99% purity) is introduced through a feeder nozzle into the plasma torch at a controlled feed rate of 0.048 g/min, using carrier argon gas at 3 L/min.

- Quenching Intervention: For rapid quenching conditions, additional argon gas is injected from the lower part of the torch toward the central axis at a high flow rate of 80 L/min. This gas injection creates a sharp temperature gradient in the plasma tail. For control experiments (no/graded quenching), this additional gas flow is omitted.

- Collection and Analysis: Synthesized nanoparticles are collected and prepared for analysis using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Size distributions for approximately 1200 nanoparticles are measured from multiple SEM micrographs to ensure statistical significance [1].

Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Quenching Effects

Computational studies using Reactive Force Field (ReaxFF) molecular dynamics provide atomic-scale insights into quenching mechanisms, particularly for carbon nanomaterial synthesis [10].

- System Initialization: The simulation begins with a defined box containing acetylene (C₂H₂) molecules as the carbon source, representing the feedstock in experimental plasma pyrolysis.

- High-Temperature Pyrolysis: The system is heated to high temperatures (typically 4000-5000 K) to simulate the plasma environment, causing molecular dissociation and formation of carbon clusters.

- Controlled Quenching: The system is cooled at different defined rates:

- Rapid quenching is simulated with fast energy removal from the system.

- Gradual quenching implements slower linear cooling.

- Pathway Analysis: The simulation tracks the formation and evolution of carbon ring structures (5-, 6-, and 7-membered rings), C–H bond breakage, and the emergence of curved versus lamellar structures. Key metrics include the number of specific ring types, H/C ratio, and the progression of carbon cluster sizes [10].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Plasma Quenching Studies

| Item Name | Function/Application | Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Inductively Coupled Thermal Plasma (ICTP) | High-temperature vaporization of precursor materials | Creates environment for vapor-phase nanoparticle nucleation [1]. |

| High-Purity Argon Gas | Plasma generation and quenching medium | Inert environment prevents oxidation; high-flow injection implements rapid quenching [1]. |

| Silicon Powder (99.99%) | Model precursor for nanoparticle synthesis | Used to study fundamental quenching effects on semiconductor nanoparticles [1]. |

| Acetylene (C₂H₂) Gas | Carbon source for graphene synthesis | Feedstock for plasma pyrolysis studies of carbon nanomaterial formation [10]. |

| ReaxFF Force Field | Atomic-scale simulation of reaction pathways | Enables molecular dynamics studies of quenching effects on chemical bonding and structure [10]. |

| Instrumented Quenching Probe | Characterizes heat extraction capability | Measures time-temperature data during quenching to determine cooling rates [15]. |

| Ethylene Glycol Coolant (-40°C) | Ultra-high quenching rate medium | Provides extreme cooling rates for studying microstructural control in alloys [16]. |

The choice between rapid and gradual quenching strategies in thermal plasma synthesis presents researchers with a powerful tool for directing material outcomes. Rapid quenching offers kinetic control, producing smaller, more uniform nanoparticles with metastable structures by arresting growth processes prematurely. In contrast, gradual cooling allows the system to approach thermodynamic equilibrium, yielding larger particles with more developed crystalline structures. The decision between these approaches must be guided by the specific material properties desired, whether for battery electrodes, catalytic supports, or structural composites. Future research will likely focus on optimizing hybrid approaches, such as staged or spatially distributed quenching, to achieve even greater control over particle characteristics and push the boundaries of nanomaterial design.

Quenching in Action: Techniques and Material Outcomes for Advanced Nanomaterials

In thermal plasma research, quenching is a critical step that rapidly cools the high-temperature plasma effluent to "freeze" desired chemical compositions or material structures by suppressing reverse reactions or controlling nucleation and growth processes. The quenching rate directly determines the final products' characteristics, from the conversion efficiency of value-added gases to the crystallinity and morphology of synthesized nanomaterials. This guide objectively compares the performance of three principal experimental quenching methods—gas injection, cooled surfaces, and nozzle expansion—based on published experimental data. It provides researchers with a detailed comparison of their protocols, outcomes, and applications, particularly within the context of controlling nucleation rates in thermal plasma systems.

The table below summarizes the core characteristics and performance data of the three primary quenching methods.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Key Experimental Quenching Methods

| Quenching Method | Typical Applications | Achieved Cooling Rate | Key Performance Metrics | Reported Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nozzle Expansion | CO₂ conversion to CO [17] [18], DRM [3] | ~10⁷ K/s [18] | Conversion increase, energy efficiency | CO₂ conversion increased from 5% to 35% (7-fold increase) [17] |

| Gas Injection (Radial) | Gas-phase synthesis of graphene [10] | Modulated via flow rate/ gas type [10] | Product morphology, crystallinity, layer number | Product evolution from spherical nanoparticles to graphene flakes; higher quenching rates produced flakes with fewer layers and higher crystallinity [10] |

| Cooled Surfaces | DRM [3], general heat removal from effluent [3] | Modeled as conductive cooling [3] | Conversion, product selectivity | Can decrease conversion in DRM (e.g., from 23.4% to 22.6%) but may improve H₂ selectivity [3] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Data

Nozzle Expansion Quenching

- Objective and Principle: To prevent the recombination of CO into CO₂ in the afterglow of a CO₂ microwave plasma by rapidly cooling the gas, thereby "freezing" the high conversion achieved in the hot plasma zone [17]. The nozzle forces mixing between hot central gas and cooler gas near the walls and, in some designs, uses adiabatic expansion to convert heat into kinetic energy, achieving rapid cooling [17] [18].

- Experimental Setup (Based on [17]):

- Plasma System: Atmospheric-pressure microwave plasma torch.

- Reactant: CO₂ gas.

- Nozzle Configuration: A water-cooled constricting nozzle of varying diameter (e.g., 2.5 mm) is attached to the reactor's effluent.

- Operating Conditions: Pressure of 900 mbar, plasma power of 1500 W, CO₂ flow rates below 10 slm.

- Key Workflow and Mechanism:

Figure 1: Nozzle Expansion Quenching Workflow

- Outcome and Performance Data:

- Conversion: Without a nozzle, conversion was approximately 5%. With a 2.5 mm nozzle, conversion enhanced to 35%, a 7-fold increase [17].

- Mechanism Insight: Computational models revealed the nozzle induces strong convective cooling and enhances conductive cooling through its water-cooled walls, with the most significant impact at low flow rates where recombination is most limiting [17].

- Quenching Rate: In a similar supersonic expansion setup, a quenching rate of 10⁷ K/s was achieved as gas temperature dropped from over 3000 K to 1000 K [18].

Gas Injection Quenching

- Objective and Principle: To control the product morphology and crystallinity in the plasma gas-phase synthesis of graphene by rapidly cooling the plasma downstream using a radial gas stream. The quenching rate modulates the residence time of carbon clusters in high-temperature zones, thereby directing the growth pathway towards specific nanostructures [10].

- Experimental Setup (Based on [10]):

- Plasma System: Magnetically rotating arc plasma system.

- Feedstock: Acetylene (C₂H₂) as the carbon source.

- Quenching System: A radial gas inlet located downstream of the plasma region, through which gases (e.g., Ar, H₂) are injected at controlled flow rates to modulate the quenching rate.

- Key Workflow and Mechanism:

Figure 2: Gas Injection Quenching Workflow

- Outcome and Performance Data:

- Product Morphology: Without quenching gas, the product consisted of spherical carbon nanoparticles. As the quenching rate increased, the product evolved into graphene flakes [10].

- Graphene Quality: Higher quenching rates resulted in graphene flakes with fewer layers, reduced defects (less amorphous carbon), and better oxidation resistance [10].

- Mechanism Insight: Reactive molecular dynamics (ReaxFF) simulations revealed that a high quenching rate rapidly lowers the growth temperature, retarding C–H bond breakage at cluster edges. The resulting C–H bonds terminate C–C bond formation, preventing edge growth bending and favoring the growth of a lamellar (graphene) structure [10].

Cooled Surface Quenching

- Objective and Principle: To remove heat from the plasma effluent via conduction to a cooled solid surface, slowing down or altering undesired chemical reactions in the afterglow, such as the reverse water gas shift reaction in Dry Reforming of Methane [3].

- Experimental Setup (Based on [3]):

- Modeling Context: This method is often modeled as conductive cooling without specifying a single reactor geometry.

- Physical Analog: Experimental implementations can involve inserting a liquid-cooled rod directly into the reactor outlet or using other water-cooled elements in the effluent stream [3].

- Operating Conditions: Studied for warm plasma DRM with CO₂/CH₄ ratios between 30/70 and 70/30.

- Key Workflow and Mechanism:

Figure 3: Cooled Surface Quenching Workflow

- Outcome and Performance Data:

- Conversion Impact: Kinetic modeling suggests conductive cooling has a minor or even slightly negative effect on conversion for certain DRM mixtures. For example, a drop in total conversion from 23.4% to 22.6% was reported for a CO₂/CH₄ ratio of 3/1 [3].

- Selectivity Impact: The primary effect is a shift in product selectivity. Cooled surfaces can boost H₂ selectivity while reducing H₂O formation, attributed to the inhibition of the reverse water gas shift reaction at lower temperatures [3].

- Application Specificity: Its effect is highly dependent on the gas mixture. It was found to be unimportant for DRM mixtures with 30/70 and 50/50 CO₂/CH₄ ratios but did affect mixtures with excess CO₂ (70/30) [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item Name | Function in Experiment | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Microwave Plasma Torch | Generates high-temperature plasma for reactant dissociation. | CO₂ dissociation into CO and O [17]. |

| Magnetically Rotating Arc Plasma System | Provides high-temperature environment for feedstock pyrolysis. | Synthesis of graphene from acetylene [10]. |

| Constricting/Converging Nozzle | Forces rapid gas expansion and mixing to induce quenching. | Effluent quenching in CO₂ microwave plasma [17] [18]. |

| Radial Gas Injection System | Injects gas into the plasma downstream to control cooling rate. | Modulating quenching rate for graphene synthesis [10]. |

| Liquid-Cooled Rod/Surface | Removes heat from the effluent via conduction. | Conductive cooling in DRM afterglow [3]. |

| Acetylene (C₂H₂) | Serves as a carbon-containing feedstock. | Precursor for graphene nanoflake synthesis [10]. |

| Argon (Ar) / Hydrogen (H₂) | Act as quenching gases or buffer gases. | Radial injection to control cooling rate and product morphology [10]. |

Leveraging Reactive Molecular Dynamics (ReaxFF) to Simulate Quenching

In molecular simulation, quenching refers to a computational technique that rapidly cools a simulated system from a high temperature to a low temperature, trapping it in a metastable state that may not be accessible through equilibrium processes. Coupled with the Reactive Force Field (ReaxFF), which allows for dynamic bond breaking and formation, quenched molecular dynamics (QMD) provides a powerful tool for generating atomistic models of complex materials and studying non-equilibrium processes. Within thermal plasma research, this methodology is invaluable for simulating the rapid cooling phases that dictate nucleation rates and the formation of novel material phases. This guide compares the application of ReaxFF-based quenching across different scientific domains, detailing protocols, outcomes, and key reagent solutions.

Comparative Analysis of ReaxFF Quenching Applications

The table below summarizes the objectives, quantitative parameters, and key findings from three distinct research applications of ReaxFF-based quenching.

Table 1: Comparative Summary of ReaxFF Quenching Applications

| Application Domain | Primary Quenching Objective | Simulation & Quenching Parameters | Key Quantitative Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanoporous Carbon Generation [19] | Generate atomistic models of Carbide-Derived Carbons (CDCs) | Quenched MD routine; System size: large systems (1000s-100,000s atoms); ReaxFF force field for C/H/O/Si. | Realistic pore size distribution achieved; Prevalence of non-hexagonal carbon rings identified; Model corroborated with experimental pair distribution functions. |

| Pollutant Emission in Co-Combustion [20] | Study NO emission mechanisms from municipal sludge/coal combustion | NVT ensemble; Temperature: High temperatures (picosecond scale); Time step: 0.25 fs; ReaxFF force field for C/H/O/N. | Identified negative synergistic effect on NO emission; Coal reduced MS-NO yield by 13.6% at 800°C; Revealed radical-driven pathways (HCN→NCO). |

| Polymer Nanocomposite Pyrolysis [21] | Investigate thermal degradation pathways of cis-1,4-polyisoprene | NVT ensemble with Nosé-Hoover thermostat; Temperature: 1500-2500 K; Time step: 0.25 fs; Duration: 42 ps; ReaxFF for C/H/O/Si. | 60 wt% nano-silica increased activation energy by 9.77% (121.9 to 133.8 kJ/mol); Extended degradation time by ~100%; Key products: C₅H₈, C₂H₄, CH₄. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

The efficacy of ReaxFF quenching simulations hinges on robust and reproducible computational methodologies. The following protocols are distilled from the cited research.

Protocol for Material Generation via Quenching (CDC Model)

This protocol, derived from the work on carbide-derived carbons, is designed for generating atomistic models of metastable materials. [19]

- System Initialization: Construct an initial simulation cell containing the relevant atoms. For a CDC model, this may involve a random or semi-ordered distribution of carbon atoms. The system size can be scaled up to hundreds of thousands of atoms to better capture structural heterogeneities.

- High-Temperature Equilibration: Heat the system to a very high temperature (e.g., several thousand Kelvin) using molecular dynamics under the NVT or NVE ensemble. This high-temperature phase randomizes the atomic structure, mimicking a molten or highly disordered state.

- Quenching Phase: Apply a linear or exponential cooling ramp to rapidly reduce the system temperature to the target level (e.g., room temperature). The quench rate (K/ps) is a critical parameter that controls the final structure; slower rates may allow for more ordered structures.

- Structural Compression (Optional): After quenching, apply external pressure to the system to achieve the desired material density. This step can help match simulated pore size distributions to experimental targets. [19]

- Validation and Analysis: Compare the final quenched structure against experimental data. Key metrics include the pair distribution function (PDF), pore size distribution (PSD), and ring statistics. Successful models will show strong agreement with these experimental benchmarks. [19]

Protocol for Reaction Pathway Analysis (Combustion/Pyrolysis)

This protocol, used in combustion and pyrolysis studies, focuses on elucidating chemical mechanisms under rapid thermal treatment. [20] [21]

- Model Construction: Build a molecular model containing the fuel and oxidizer (for combustion) or the polymer matrix (for pyrolysis). For co-combustion, this involves creating a mixed system, such as municipal sludge and coal molecules. [20]

- Simulation Setup: Perform ReaxFF MD simulations in the NVT ensemble to control temperature. Use a Nosé-Hoover thermostat to maintain a stable temperature profile. A very small time step (e.g., 0.25 femtoseconds) is required to accurately capture bond-breaking events. [20] [21]

- Thermal Treatment: Expose the system to a target high temperature (e.g., 2500 K for pyrolysis, or combustion-relevant temperatures) for a sufficient duration (tens of picoseconds) to initiate and propagate reactions.

- Trajectory Analysis: Analyze the simulation trajectory to identify reaction products, intermediates, and pathways. Techniques like atomic labeling can trace the fate of specific atoms (e.g., nitrogen from sludge vs. coal). [20]

- Product Quantification: Count the formation of key molecular species (e.g., NO, HCN, isoprene) over time to calculate product yields and understand the influence of additives or mixture composition. [20] [21]

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the generalized logical workflow for a ReaxFF-based quenching simulation, integrating common steps from the reviewed protocols.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below catalogs key computational and material components used in the featured ReaxFF quenching studies.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ReaxFF Quenching Studies

| Reagent / Material / Model | Function in Simulation | Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| ReaxFF Force Field (C/H/O/N) | Describes reactive potential energy surface; enables bond breaking/formation. | Fundamental for all combustion [20] and pyrolysis [21] simulations. |

| ReaxFF Force Field (C/H/O/Si) | Describes reactive potential energy surface for systems containing silicon. | Essential for simulating nano-silica composites [21] or Si-containing carbides [19]. |

| Municipal Sludge Molecular Model (C₁₄₆H₁₄₂O₂₅N₁₆) | Atomistic representation of sludge fuel for studying co-combustion reactions. | Used to probe NO emission mechanisms versus coal [20]. |

| Nano-Silica Units | Nanoparticulate additive to modulate thermal degradation pathways. | Stabilizes polyisoprene, altering pyrolysis kinetics and products [21]. |

| Nosé-Hoover Thermostat | Algorithm to control and maintain system temperature during MD. | Critical for implementing the NVT ensemble during thermal treatment [21]. |

| Atomic Labeling Method | Computational technique to track the origin and fate of specific atoms. | Differentiates nitrogen from sludge vs. coal in product gases like NO [20]. |

ReaxFF-based quenched molecular dynamics serves as a versatile and powerful tool for investigating out-of-equilibrium processes across diverse fields. As the comparative data demonstrates, its application ranges from generating structurally validated models of disordered materials like nanoporous carbons to unraveling complex radical-driven reaction networks in combustion and pyrolysis. The core strength of this methodology lies in its ability to provide atomistic insights into phenomena that are difficult to probe experimentally, such as the role of specific radicals in NO formation or the atomistic structure of a nanopore. For researchers in thermal plasma science, the protocols and case studies presented here offer a foundational framework for adapting ReaxFF quenching simulations to model nucleation and growth processes under rapid cooling, ultimately enabling better control and design of materials synthesized in plasma environments.

Within thermal plasma research, the quenching process is a critical lever for controlling nanoparticle nucleation and growth. Quenching, the rapid cooling of a high-temperature plasma stream, directly governs reaction kinetics, thereby determining key nanoparticle characteristics such as size, distribution, and crystallinity [1]. This case study examines the pivotal role of quenching in the synthesis of silicon nanoparticles (SiNPs) and silica nanoparticles (SiO2 NPs), with a specific focus on how engineered quenching strategies enable precise control over particle properties for advanced applications, including drug delivery.

The fundamental principle hinges on manipulating the cooling rate to dominate the competition between nucleation and growth phases. As one computational study notes, "At higher cooling rates, one obtains greater total number density, smaller size, and smaller standard deviation" [1]. This establishes quenching as a powerful, albeit complex, tool for tailoring nanomaterials.

Quenching Effects on Nucleation and Growth Dynamics

Mechanisms of Quenching in Thermal Plasma Systems

In thermal plasma fabrication, precursor materials are vaporized at extreme temperatures (~10,000 K). The subsequent journey through the plasma tail subjects this vapor to a steep temperature gradient, triggering supersaturation—the driving force for nucleation [1]. Quenching acts at this precise moment by rapidly removing thermal energy, which "freezes" the particle population.

Experimental and computational studies reveal a two-stage growth process:

- Vapor Conversion: In a highly supersaturated state, 40–50% of vapor atoms are rapidly converted to nanoparticles via homogeneous nucleation and heterogeneous condensation [1].

- Coagulative Growth: After the vapor is largely consumed, nanoparticle growth continues through interparticle coagulation, a comparatively slower process [1].

Quenching interventions, such as the injection of cool gas, are designed to maximize the first stage while curtailing the second.

Impact of Cooling Rate on Final Particle Characteristics

The rate of cooling directly and predictably influences nanoparticle characteristics. Higher cooling rates lead to:

- Increased Number Density: Rapid quenching creates a high degree of supersaturation, generating a large population of nuclei.

- Reduced Average Size: With limited thermal energy and time, these nuclei have less opportunity for growth via condensation or coagulation.

- Narrower Size Distribution: A swift and uniform quenching event produces a more monodisperse population by synchronizing the nucleation burst.

These effects were demonstrated in ReaxFF molecular dynamics simulations of carbon nanoparticle synthesis, which showed that increased quenching rates rapidly lower growth temperature, retarding chemical reactions at cluster edges and preventing growth bending [10]. While focused on carbon, the underlying physical principles are analogous to silicon nanoparticle growth.

Comparative Analysis of Size Control Methodologies

Thermal Plasma Synthesis with Quenching

Thermal plasma synthesis represents a high-throughput, gas-phase method for producing high-purity nanoparticles. Controlling particle characteristics requires modulating the plasma's temperature and flow fields, often through strategic quenching.

Table 1: Experimental Quenching Strategies in Thermal Plasma Synthesis

| Quenching Method | Mechanism of Action | Impact on Nanoparticle Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Radial/Counterflow Gas Injection [1] [10] | Injects cool gas into the plasma downstream, increasing convective cooling and reducing vapor residence time. | Increases number density, reduces average particle size, and narrows size distribution. |

| Water-Cooled Probes (Coil/Ball) [1] [10] | Introduces a cold physical surface into the plasma, providing a heat sink for rapid thermal quenching. | Enhances nucleation rate and can achieve high production yields (e.g., 17 g/min for SiNPs) [1]. |

| Pulse Modulation [1] | Periodically interrupts plasma power, creating cyclic temperature drops that quench the reaction. | Offers dynamic control over growth processes, potentially improving batch-to-batch consistency. |

The efficacy of gas quenching was quantitatively demonstrated in graphene synthesis, where increased quenching rates transformed the product from spherical carbon nanoparticles to high-quality, few-layer graphene flakes [10]. This underscores quenching's role in controlling not only size but also morphology and structure.

Colloidal (Wet-Chemical) Synthesis

In contrast to plasma methods, colloidal synthesis, such as the Stöber process or micelle entrapment, offers precision at a smaller scale. This liquid-phase approach controls size through chemical kinetics.

A systematic study of a micelle entrapment method demonstrated precise sizing from 15 nm to 1800 nm by tuning parameters like reaction temperature, solvent (butanol) volume, and silica precursor volume [22] [23]. For instance, raising the temperature from 22°C to 47°C incrementally increased particle size from 27 nm to 172 nm [22].

Table 2: Size Control Parameters in Colloidal Synthesis of Silica Nanoparticles [22] [24]

| Synthesis Parameter | Directional Change | Typical Effect on SiNP Size | Underlying Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction Temperature | Increase | Increase (in a specific range) | Accelerates both nucleation and growth kinetics, often favoring growth. |

| Precursor Concentration | Increase | Increase | Provides more material for particle growth, shifting balance from nucleation to growth. |

| Catalyst Concentration | Increase | Decrease | Accelerates hydrolysis/condensation rates, leading to a higher nucleation density. |

| Solvent Composition | Higher Ethanol/Butanol | Variable (offers fine control) | Modulates precursor hydrolysis rate and micelle size in emulsion-based methods. |

Experimental Protocols for Plasma Synthesis with Quenching

Protocol: Inductively Coupled Thermal Plasma (ICTP) Synthesis with Gas Quenching

This protocol is adapted from experiments investigating quenching effects on silicon nanoparticle growth [1].

Objective: To synthesize silicon nanoparticles with controlled size and distribution using radial gas injection for quenching.

Materials and Equipment:

- Plasma System: Inductively Coupled Thermal Plasma (ICTP) torch and reaction chamber.

- Precursor: Coarse silicon powder (e.g., ~7 μm particle size, 99.99% purity).

- Process Gases: Argon (plasma work gas and carrier gas).

- Quenching System: Gas manifold for radial injection of quench gas (e.g., Argon) into the plasma downstream.

- Characterization: Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) for size distribution analysis.

Procedure:

- System Preparation: Evacuate and backfill the main chamber with argon to create an inert atmosphere (e.g., 100 kPa).

- Plasma Ignition: Sustain the plasma by continuously injecting argon gas (e.g., 35 L/min) at the torch top.

- Precursor Introduction: Feed coarse silicon powder into the plasma torch using a powder feeding system at a controlled rate (e.g., 0.048 g/min) with argon carrier gas (e.g., 3 L/min).

- Application of Quenching: Initiate radial injection of quench gas from the lower part of the torch toward the central axis. The flow rate is the primary variable (e.g., 0 L/min for no quenching, 80 L/min for high quenching) [1].

- Product Collection: Nanoparticles are collected in a water-cooled collection chamber following the reaction zone.

- Analysis: Determine the size distribution by measuring the diameters of approximately 1200 nanoparticles from multiple SEM micrographs [1].

Supporting Computational Modeling

Computational models are crucial for understanding the mechanisms behind experimental observations.

- Nodal (Sectional) Model (Type D): This model discretizes the nanoparticle size distribution and solves for its temporal evolution, accounting for simultaneous homogeneous nucleation, heterogeneous condensation, and interparticle coagulation [1]. It is computationally intensive but can predict complex, non-lognormal size distributions, making it suitable for simulating the rapid transients induced by quenching [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Materials and Reagents for Silicon Nanoparticle Research

| Item | Specification / Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Silica Precursor | Triethoxyvinylsilane (TEVS) or Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS). Silicon source for nanoparticle synthesis. | Colloidal / Sol-Gel Synthesis [22] [24] |

| Catalyst | Aqueous Ammonia (NH4OH). Base catalyst to accelerate hydrolysis and condensation reactions. | Colloidal / Sol-Gel Synthesis (Stöber process) [24] |

| Surfactant | Tween 80, CTAB. Stabilizes emulsions or micelles for confined growth and size control. | Micelle Entrapment Methods [22] |

| High-Purity Silicon | 99.99% purity coarse powder. Evaporation feedstock for high-purity nanoparticle production. | Thermal Plasma Synthesis [1] |

| Process & Quench Gas | High-purity Argon, Helium, or Hydrogen. Sustains plasma and acts as a cooling medium for quenching. | Thermal Plasma Synthesis [1] [10] |

Visualization of Quenching Mechanisms and Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the logical relationships and experimental workflows in quenching-controlled nanoparticle synthesis.

Plasma Quenching Mechanism

Diagram Title: How Quenching Rate Controls Nanoparticle Size

Experimental Synthesis Workflow

Diagram Title: Thermal Plasma Synthesis Workflow

This case study demonstrates that quenching is a fundamental process for exerting precise control over silicon nanoparticle size and distribution in thermal plasma synthesis. The cooling rate directly and predictably influences nucleation kinetics and growth dynamics, enabling researchers to tailor nanomaterials for specific applications. While thermal plasma with gas quenching excels in high-throughput production of high-purity particles, colloidal methods offer complementary fine control at a smaller scale. The integration of robust experimental protocols with advanced computational models provides a powerful framework for advancing the field, paving the way for the next generation of engineered nanoparticles for drug delivery and other advanced technologies.

Few-layer graphene (FLG) has emerged as a critical nanomaterial with extraordinary electrical, thermal, and mechanical properties. Within thermal plasma research, controlling the nucleation and growth dynamics of FLG presents a significant challenge, with effect quenching emerging as a pivotal technique for manipulating synthesis outcomes. Quenching—the rapid cooling of a reaction system—directly influences nucleation rates and crystal quality by arresting growth processes at precisely defined moments. This case study provides a comprehensive comparison of FLG synthesis methodologies, analyzing how strategic implementation of quenching protocols affects critical quality parameters including crystallinity, layer number, defect density, and electrical performance, thereby offering researchers a framework for optimizing synthesis conditions for specific application requirements.

Synthesis Methodologies and Quenching Protocols

Thermal Reduction of Graphite Oxide

A fast thermal synthesis approach enables large-scale FLG production from high-purity natural graphite. This method involves thermal exfoliation and reduction of graphite oxide at specific temperature stages with controlled quenching in an inert atmosphere [25].