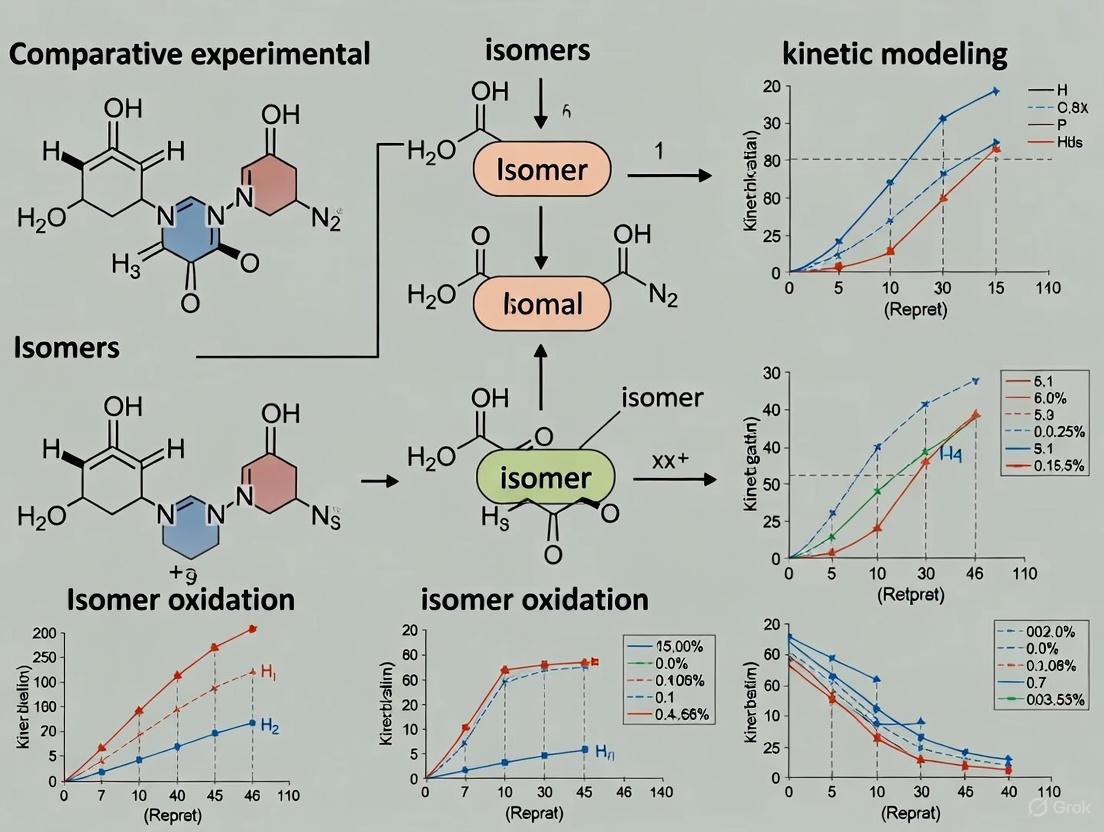

Comparative Experimental and Kinetic Modeling of Isomer Oxidation: From Fundamental Chemistry to Engine Application

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the combustion characteristics of fuel isomers, with a specific focus on alcohol isomers like propanol and butanol.

Comparative Experimental and Kinetic Modeling of Isomer Oxidation: From Fundamental Chemistry to Engine Application

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of the combustion characteristics of fuel isomers, with a specific focus on alcohol isomers like propanol and butanol. It integrates foundational experimental data from reactors and shock tubes with advanced kinetic modeling techniques. The content explores methodological approaches for mechanism development, troubleshooting strategies for model optimization, and validation protocols through comparative analysis. Aimed at researchers and scientists in combustion chemistry and fuel development, this review synthesizes current knowledge to highlight structure-reactivity relationships and their critical implications for designing cleaner, more efficient combustion systems and alternative fuels.

Exploring Isomer-Dependent Combustion: Molecular Structure and its Impact on Reactivity

The global transition toward sustainable energy has intensified the exploration of biofuels as viable alternatives to conventional fossil fuels. Among these, alcohol-based biofuels, particularly isomers of propanol (C₃H₇OH) and butanol (C₄H₉OH), have garnered significant scientific interest for their promising fuel properties and potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. While ethanol remains the most widely used alcohol biofuel, higher alcohols like propanol and butanol offer distinct advantages, including higher energy density and better compatibility with existing engine infrastructure [1] [2]. This review objectively compares the performance of propanol and butanol isomers as biofuels, framed within the context of comparative experimental and kinetic modeling of isomer oxidation research. The analysis draws upon recent experimental data, combustion studies, and metabolic engineering advances to provide a comprehensive resource for researchers and scientists engaged in fuel development and sustainable energy solutions.

Fundamental Properties of Propanol and Butanol Isomers

The combustion characteristics and engine performance of alcohol fuels are fundamentally influenced by their molecular structure and physicochemical properties. Propanol exists as two structural isomers: n-propanol (1-propanol) and isopropanol (2-propanol). Butanol has four isomers: n-butanol (1-butanol), isobutanol (2-methyl-1-propanol), sec-butanol (2-butanol), and tert-butanol (2-methyl-2-propanol). The arrangement of carbon atoms and the position of the hydroxyl group in each isomer create distinct combustion behaviors and fuel characteristics.

Table 1: Comparative Physicochemical Properties of Alcohol Biofuels

| Property | Methanol | Ethanol | n-Propanol | i-Propanol | n-Butanol | Gasoline | Diesel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Formula | CH₃OH | C₂H₅OH | C₃H₇OH | C₃H₇OH | C₄H₉OH | C₄–C₁₂ | C₉–C₂₅ |

| Molecular Mass (g/mol) | 32.04 | 46.07 | 60.10 | 60.10 | 74.12 | ~100 | ~200 |

| Energy Density (MJ/kg) | 19.9 [3] | 26.7 [3] | 30.6 [3] | - | ~33.1 [2] | ~44 | ~45 |

| Research Octane Number (RON) | 109 | 109 | 108 [4] | 106 [4] | 96 [4] | 90-100 | - |

| Motor Octane Number (MON) | 89 | 90 | - | - | 78 [4] | 82-90 | - |

| Cetane Number | - | 8 | 12 [4] | - | ~17 [4] | - | 45-55 |

| Oxygen Content (% wt) | 49.9 | 34.7 | 26.6 | 26.6 | 21.6 | <2.7 | 0 |

| Boiling Point (°C) | 64.7 | 78.4 | 97 | 82.6 | 117.7 | 27-225 | 180-330 |

Key property differentiators impact engine performance: n-propanol has a higher calorific value (30.6 MJ/kg) and octane number (RON 118) than many shorter-chain alcohols, promoting efficient energy release [3]. Butanol isomers, particularly n-butanol, demonstrate superior energy content (~33.1 MJ/kg) and cetane numbers, making them more suitable for compression ignition engines [2]. The longer carbon chains in butanol isomers provide fuel properties more closely aligned with conventional diesel, including better miscibility and lower hygroscopicity compared to ethanol.

Experimental Performance Data in Engine Applications

Spark Ignition (SI) Engine Performance

Experimental studies using propanol-gasoline blends in 4-stroke SI engines demonstrate significant impacts on performance and emissions. Testing across propanol concentrations (0-18%) and engine speeds (1700-3800 rpm) under fixed loads reveals that increased propanol content enhances combustion due to oxygen content and higher latent heat of vaporization.

Table 2: Optimized SI Engine Performance with Propanol-Gasoline Blends (18% Propanol) [1]

| Performance Parameter | Value | Emission Type | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Engine Torque | 8.23 Nm | CO | 4.72 % |

| Brake Power | 2.94 kW | CO₂ | 9.54 % |

| Brake Thermal Efficiency (BTE) | 21.76 % | HC | 53.92 ppm |

| Brake Specific Fuel Consumption (BSFC) | 0.446 kg/kWh | NOx | 1679.27 ppm |

Response Surface Methodology optimization at 18% propanol content, 20 psi load, and 3436 rpm engine speed demonstrated enhanced torque, brake power, and brake thermal efficiency alongside reduced hydrocarbon (HC) and carbon monoxide (CO) emissions [1]. The oxygenated nature of propanol promotes more complete combustion, thereby reducing CO and HC emissions, though NOx levels may increase due to higher combustion temperatures.

Compression Ignition (CI) Engine Performance

In CI engines, research focuses on biodiesel-alcohol blends to reduce diesel dependency. Recent investigations of complete diesel replacement using 90% biodiesel with 10% propanol and carbon nanotube (CNT) additives show promising results across three CNT variants (SWCNT, DWCNT, MWCNT) at 100 ppm concentration.

Table 3: Diesel Engine Performance with Biodiesel-Propanol-CNT Blends (1500 rpm) [5]

| Parameter | SWCNT Blend | DWCNT Blend | MWCNT Blend | Conventional Diesel |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cylinder Pressure Change | +0.2% | -11.9% | +0.7% | Baseline |

| Heat Release Rate Improvement | +13.1% | +11.2% | +13.0% | Baseline |

| Brake Specific Fuel Consumption (BSFC) | +9.2% | +12.7% | +13.2% | Baseline |

| Brake Thermal Efficiency (BTE) | +6.3% | +3.1% | +1.5% | Baseline |

| NOx Emissions | -7.3% | -7.6% | -8.4% | Baseline |

| HC Emissions Improvement | Up to 40.2% | Up to 40.2% | Up to 40.2% | Baseline |

These findings demonstrate that MWCNT-enhanced biodiesel-propanol blends significantly reduce emissions, particularly NOx and HC, despite slightly increased fuel consumption [5]. The addition of oxygenated alcohols like propanol to biodiesel improves combustion efficiency and reduces particulate matter through more complete oxidation.

Spray and Combustion Characteristics

Fundamental combustion studies in constant volume chambers reveal differences in spray evolution and flame characteristics between biodiesel and alcohol-blended fuels. Experiments with soybean-based biodiesel blended with n-propanol and n-butanol show that alcohol addition increases liquid spray penetration length and flame lift-off length, indicating improved spray characteristics [6]. Alcohol-fuel blends exhibit reduced peak combustion pressure but increased peak apparent heat release rate, alongside shorter ignition delay and combustion duration. The lower natural flame luminosity of alcohol blends suggests reduced carbon soot production, supporting low-carbon combustion strategies [6].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Engine Testing Protocol

Standard experimental protocols for evaluating alcohol biofuel performance typically involve:

- Fuel Preparation: Propanol isomers are blended with gasoline in volumetric ratios (e.g., 5%, 10%, 15%, 18%) using mechanical stirring or ultrasonic mixing to ensure homogeneity [1]. Butanol isomers are typically tested in blends ranging from 10-40% with diesel or biodiesel.

- Engine Test Setup: A single-cylinder, four-stroke engine coupled with an eddy current dynamometer is standard. Experiments are conducted at constant loads (e.g., 10 and 20 psi) with varying engine speeds (1700-3800 rpm) [1].

- Data Acquisition: Combustion parameters (cylinder pressure, heat release rate) and performance metrics (torque, brake power, BSFC, BTE) are recorded. Emissions are analyzed using exhaust gas analyzers for CO, CO₂, HC, and NOx [1] [5].

- Statistical Optimization: Response Surface Methodology (RSM) designs experiments, develops empirical models, and identifies optimum operating conditions through analysis of variance (ANOVA) [1].

Constant Volume Chamber Combustion Study

For fundamental spray and combustion analysis:

- Apparatus: Constant Volume Chamber (CVC) systems simulate engine-like conditions, featuring cylindrical combustion chambers with optical access via quartz windows [6].

- Fuel Injection: High-pressure fuel injection systems replicate actual engine injection parameters.

- Optical Diagnostics: High-speed shadowgraphy captures spray evolution, while natural flame luminosity imaging characterizes combustion behavior [6].

- Parameter Measurement: Software analysis determines spray penetration length, flame lift-off length, ignition delay, and combustion duration from recorded images.

Kinetic Modeling of Alcohol Isomer Oxidation

Kinetic modeling provides crucial insights into combustion mechanisms of alcohol isomers, predicting ignition behavior, flame propagation, and pollutant formation. Detailed kinetic mechanisms for n-propanol and isopropanol combustion comprise numerous reactions among hundreds of species, validated against experimental data from flow reactors, shock tubes, and counterflow diffusion flames [7] [4].

Combustion pathways differ significantly between isomers. Isopropanol oxidation predominantly forms acetone as a key intermediate across all combustion conditions, while n-propanol oxidation produces propanal [7]. These distinct pathways influence overall combustion efficiency and emission profiles, with isopropanol generally exhibiting higher reactivity under certain conditions.

Modern kinetic models employ lumping techniques to manage computational complexity while maintaining predictive accuracy for higher alcohols (C≥5). The CRECK kinetic model demonstrates this approach, validated against new ignition delay time measurements and speciation data [4]. Such models enable synergistic fuel-engine design, allowing parametric analyses of ignition propensity for different fuel blends.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biofuel Combustion Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Experimental Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| n-Propanol/i-Propanol (≥99.5%) | Fuel component for gasoline blending | SI engine performance and emission studies [1] |

| n-Butanol/Butanol Isomers (≥99%) | Diesel/biodiesel blending component | CI engine combustion and emission analysis [2] |

| Commercial Biodiesel (B100) | Base fuel for alcohol blending | Diesel replacement studies with alcohol additives [5] |

| Carbon Nanotubes (SWCNT/DWCNT/MWCNT) | Nano-additives for fuel enhancement | Improve combustion efficiency and reduce emissions [5] |

| Ultra-Low Sulphur Diesel | Baseline reference fuel | Benchmark for alternative fuel performance comparison [5] |

| Clostridia Strains | Microbial fermentation hosts | Biopropanol/biobutanol production from biomass [3] |

| Lignocellulosic Biomass | Non-edible fermentation feedstock | Second-generation biofuel production [3] [8] |

| Gas Chromatograph-Mass Spectrometer | Speciation analysis | Intermediate and pollutant identification in combustion [7] |

Propanol and butanol isomers present compelling cases as advanced biofuels with distinct advantages and limitations. n-Propanol demonstrates excellent SI engine performance with reduced HC and CO emissions, while butanol isomers show superior compatibility with CI engines due to higher cetane numbers and energy density. Kinetic modeling reveals fundamental differences in oxidation pathways between isomers, explaining variations in combustion efficiency and pollutant formation.

The commercial viability of these alcohols depends on overcoming production challenges through advanced metabolic engineering of fermentation strains and utilization of non-food biomass. Future research should focus on optimizing combustion strategies for specific isomer properties, developing more accurate kinetic models for isomer blends, and advancing biorefinery concepts for sustainable production. As the global biofuel market continues to evolve, propanol and butanol isomers offer promising pathways for reducing fossil fuel dependence and advancing toward a more sustainable energy future.

The combustion chemistry of hydrocarbon isomers is a cornerstone of developing cleaner and more efficient propulsion systems. A fundamental property for evaluating fuel reactivity in such systems is the ignition delay time (IDT), defined as the time interval between fuel-air mixture exposure to a high-temperature, high-pressure environment and the onset of explosive ignition. This guide provides a comparative analysis of experimental IDT data for two prominent sets of hydrocarbon isomers—butanols and pentanes—obtained primarily from shock tube studies. Understanding how molecular structure dictates ignition behavior is critical for the computational kinetic modeling of combustion, which forms the basis for optimizing next-generation engine designs and selecting sustainable alternative fuels.

Ignition Delay Time Data Comparison

The following tables summarize key experimental ignition delay data for butanol and pentane isomers, collected from shock tube (ST) and rapid compression machine (RCM) studies under varied conditions.

Table 1: Experimental Ignition Delay Data for Butanol Isomers

| Isomer | Experimental Setup | Conditions (Pressure, Equivalence Ratio φ) | Observed Reactivity Order (Most to Least Reactive) | Key Observations | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-, iso-, tert-Butanol (in diesel blends) | Constant Volume Vessel (Engine-like conditions) | Various blend ratios, 715-910 K | tert-Butanol > n-Butanol > iso-Butanol | tert-Butanol blends showed fastest LTHR and shortest ID despite higher octane number. Absence of H atom on alpha carbon alters chemistry. [9] | [9] |

| s-, t-, i-Butanol (neat) | Rapid Compression Machine (RCM) | 15 bar, 30 bar; φ=1.0 | n-Butanol > s-Butanol ≈ i-Butanol > t-Butanol (at 15 bar) | Order changes with pressure. t-Butanol exhibited pre-ignition heat release, especially at higher pressures (30 bar) and fuel loads (φ=2.0). [10] | [10] |

| n-, s-, i-, t-Butanol (in n-heptane blends) | Ignition Quality Tester (IQT) | ASTM D6890-07a protocol | t-Butanol blends showed highest reactivity | Despite low pure-component reactivity, t-butanol's lack of α-H atoms reduces radical suppression, increasing blend reactivity. [11] | [11] |

Table 2: Experimental Ignition Delay Data for Pentane Isomers

| Isomer | Experimental Setup | Conditions (Pressure, Equivalence Ratio φ, Temperature) | Key Observations | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-, iso-, neo-Pentane | Shock Tubes (ST) & Rapid Compression Machine (RCM) | 1, 10, 20 atm; φ=0.5, 1.0, 2.0; 643-1718 K | n-Pentane: Most reactive due to straight-chain structure enabling fast low-temperature chain-branching reactions. neo-Pentane: Least reactive at low temperatures; its highly branched, symmetric structure lacks secondary C-H bonds, inhibiting key isomerization steps in low-temperature oxidation pathways. [12] | [12] |

Experimental Methodologies

Shock Tube Fundamentals

The shock tube is a premier apparatus for measuring ignition delay times under well-defined, homogeneous conditions. It operates by utilizing a high-pressure driver gas and a low-pressure driven section separated by a diaphragm or fast-opening valve. The instantaneous rupture of the diaphragm sends a compression shock wave into the driven section, which contains the test fuel-oxidizer mixture. This shock wave reflects from the end wall, rapidly increasing the temperature and pressure of the test gas mixture and initiating the ignition process. [12] [13] [14]

The core measurement involves recording the pressure history at the end wall. The IDT is typically defined as the time between the arrival of the reflected shock wave (marked by a sharp pressure rise) and the subsequent rapid pressure increase due to ignition, often identified by the maximum slope in the pressure trace or the onset of CH* chemiluminescence. [12] [13] Advanced techniques like infrared laser absorption are sometimes used to verify initial fuel concentration. [12] To achieve higher pressures necessary for studying low-reactivity fuels, shock-wave focusing elements (SWFEs) can be employed to converge planar shocks, amplifying their strength and generating pressures far beyond conventional tube limits. [14]

Rapid Compression Machines (RCMs)

An RCM simulates a single compression stroke of an internal combustion engine. It uses a piston to compress the test mixture rapidly, achieving high-temperature and high-pressure conditions similar to those in an engine cylinder before ignition. The IDT is measured from the end of the compression to the pressure rise from ignition. RCMs are particularly valuable for studying ignition at lower temperatures (e.g., 600–900 K) relevant to engine knock and auto-ignition, effectively bridging the gap between shock tube data and real engine conditions. [12] [10]

The diagram below illustrates the typical workflow for a comparative ignition delay study using these key experimental apparatuses.

Chemical Pathways and Kinetic Modeling

The stark differences in ignition delays among isomers are a direct manifestation of their distinct molecular structures and the resulting oxidation chemistries. Detailed chemical kinetic models, developed and validated against the IDT data presented above, reveal the controlling reaction pathways.

For the butanol isomers, the reactivity is heavily influenced by the presence and location of hydrogen atoms relative to the hydroxyl (-OH) group. The initial fuel decomposition often involves the abstraction of an H atom, and the ease of this abstraction is site-specific. n-Butanol, with a straight chain, has multiple easily abstractable H atoms, facilitating faster progression through the oxidation chain. In contrast, tert-butanol lacks a hydrogen atom on the carbon bearing the OH group (the so-called α-carbon). This unique structure means it does not consume as many OH radicals during initial oxidation, making more radicals available to oxidize a blended fuel (like diesel or n-heptane), which explains its surprisingly short ignition delay in blends. [9] [11]

For the pentane isomers, the divergence in reactivity is governed by the well-established low-temperature oxidation mechanism for alkanes. This mechanism involves the sequential addition of molecular oxygen to alkyl radicals, followed by isomerization via intramolecular H-atom transfer. The rate of this isomerization is highly sensitive to the size of the cyclic transition state and the type of C-H bonds broken. n-Pentane, with its straight chain, allows for facile isomerization via 6- and 7-membered transition rings, leading to chain branching and short ignition delays. Conversely, the highly branched structure of neo-pentane creates a kinetic bottleneck. Its structure prohibits the formation of the necessary transition states for the key isomerization steps, effectively shutting down the low-temperature chain-branching pathway and resulting in significantly longer ignition delays at lower temperatures. [12]

The following diagram summarizes the primary reaction pathways that differentiate isomer oxidation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Apparatus

This section details the core materials and instruments essential for conducting ignition delay studies on fuel isomers.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Apparatus

| Item Name | Function/Description | Relevance to Isomer Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Shock Tube | Apparatus for generating high-temperature, high-pressure conditions via a reflected shock wave for fundamental IDT measurement. [12] [13] | Primary tool for acquiring homogeneous gas-phase IDT data for model validation under a wide range of T and P. |

| Rapid Compression Machine (RCM) | Simulates a single engine compression stroke, creating conditions relevant to auto-ignition and engine knock. [12] [10] | Crucial for studying low-to-intermediate temperature chemistry (600–900 K) where shock tube data is sparse. |

| Ignition Quality Tester (IQT) | Standardized device (ASTM D6890) that measures derived cetane number (DCN) from a spray combustion process. [11] | Provides application-relevant blending behavior data, linking fundamental kinetics to practical fuel rating. |

| High-Purity Isomers | Research-grade (typically >99% purity) samples of the isomeric fuels under study (e.g., n-/iso-/neo-pentane, n-/s-/i-/t-butanol). | Ensures experimental results are not confounded by impurities, allowing clear attribution of reactivity to molecular structure. |

| Driver/Driven Gases | High-pressure driver gas (e.g., He, N₂, He/Ar mixtures) and controlled-composition driven gas ("air" or oxidizer/fuel/inert mixes). [12] [13] [14] | Tailoring the driver gas composition (e.g., using Ar or N₂ with He) can extend test times. The driven gas composition defines the test condition (φ, diluent). |

| Shock-Wave Focusing Element (SWFE) | A specially designed convergent section for a shock tube that focuses the shock wave to achieve extreme pressures (>40 MPa). [14] | Enables study of ignition kinetics at very high pressures relevant to advanced combustion engines. |

Laminar burning velocity (LBV) is a fundamental property of a fuel-oxidizer mixture that characterizes the rate at which a flat, unstretched flame propagates into the unburned reactant mixture. It is an intrinsic parameter determined by the complex interplay of chemical kinetics, molecular transport, and thermodynamic properties. This metric serves as a critical benchmark for validating detailed chemical kinetic mechanisms and plays a vital role in the design of combustion devices, influencing stability, blow-off limits, and emissions.

The molecular structure of a fuel, including its carbon skeleton arrangement, functional groups, and bond energies, profoundly influences its combustion characteristics. Even among isomers—compounds with identical molecular formulas—significant differences in LBV can arise due to variations in the ease of initial fuel decomposition, the nature of the radical pool generated, and the subsequent pathways of intermediate oxidation. This article provides a comparative analysis of how molecular structure induces variations in laminar burning velocity, drawing upon experimental data and kinetic modeling studies across several important fuel classes, including alcohols, alkenes, and oxygenated biofuels.

Comparative LBV Data Across Fuel Structures

Experimental data from the literature reveals clear trends in laminar burning velocities based on molecular structure. The following tables summarize key findings for different fuel families.

Table 1: Laminar Burning Velocities of Butanol Isomers (at 343 K, 1 atm) [15]

| Isomer | Common Name | Maximum LBV (cm/s) | Equivalence Ratio at Peak LBV (ϕ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| n-Butanol | 1-Butanol | 50.0 | 1.10 - 1.15 |

| sec-Butanol | 2-Butanol | 48.5 | 1.10 - 1.15 |

| iso-Butanol | 2-Methyl-1-propanol | 47.0 | 1.10 - 1.15 |

| tert-Butanol | 2-Methyl-2-propanol | 39.0 | 1.10 - 1.15 |

Table 2: Laminar Burning Velocities of Butene and C3H6O Isomers (at ~298 K, 1 atm) [16] [17]

| Fuel Family | Isomer | Maximum LBV (cm/s) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Butene (C4H8) | 1-Butene | ~48 [17] | Highest reactivity among butenes |

| trans-2-Butene | ~46 [17] | Intermediate reactivity | |

| Isobutene | ~42 [17] | Lowest reactivity among butenes | |

| C3H6O | Propylene Oxide | ~43 [16] | Cyclic ether; fastest in group |

| Propionaldehyde | ~40 [16] | Aldehyde | |

| Acetone | ~36 [16] | Ketone; slowest in group |

Table 3: LBV Enhancement in Ammonia Flames via Additives/Oxidizers [18] [19] [20]

| Fuel Mixture | Condition | Reported LBV | Enhancement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| NH3/Air | - | 6-7 cm/s [20] | Baseline |

| NH3/H2/Air | 40% H2 in fuel | 29-30 cm/s [20] | ~4-5x |

| NH3/N2O | - | ~77.6 cm/s [18] | ~10x vs air, ~3x vs O2/N2 |

| NH3/O2/NO/CO2 | With NO in oxidizer | Significantly enhanced [19] | Chemical promotion via NO |

Experimental Methodologies for LBV Measurement

Several established experimental techniques are employed to determine laminar burning velocities, each with specific strengths and considerations.

Constant Volume Combustion Chamber (Spherically Expanding Flame)

This method involves igniting a quiescent fuel-oxidizer mixture at the center of a rigid vessel and optically tracking the subsequent outwardly propagating spherical flame. High-speed schlieren or shadowgraph photography records the flame radius as a function of time. The stretched flame speed is derived from the radius-time history. A nonlinear regression methodology is then applied to eliminate stretch effects and extrapolate to the unstretched laminar burning velocity. This technique was used in studies on butanol isomers [15] and butene isomers [17]. It is well-suited for measurements at elevated pressures and temperatures but requires careful correction for flame stretch and instabilities.

Heat Flux Method (Flat Flame Stabilization)

This approach establishes a stationary, adiabatic, flat flame on a perforated plate burner. The principle relies on balancing the heat loss from the flame to the burner plate with the heat gain of the unburned gas mixture preheting as it flows through the plate. When the radial temperature gradient across the plate becomes zero, the flame is adiabatic, and the LBV is calculated directly from the volumetric flow rate of the unburned mixture. This method, cited in the context of NH3/CH4/O2/NO/CO2 flames [19], provides stretch-free data directly and is known for its high accuracy at atmospheric pressure.

Counterflow Burner (Twin-Flame Configuration)

In this setup, two opposing jets of unburned mixture issue from nozzles, forming twin premixed flames stabilized in the resulting stagnation flow field. The velocity of the unburned gas is gradually increased until the flame extinguishes. The laminar burning velocity is determined from the measured flow velocity at extinction through extrapolation techniques. This method was employed for butanol isomers [15] and butene isomers [17]. It is particularly useful for studying strained flames and for fuels prone to cellular instabilities in spherical configurations.

Kinetic Modeling and Reaction Path Analysis

Kinetic modeling is indispensable for interpreting experimental LBV data and elucidating the underlying chemical physics responsible for structural effects.

Sensitivity and Reaction Path Analyses are two primary computational tools. Sensitivity analysis identifies the chemical reactions that have the greatest influence on the flame speed. For instance, the mass burning rates of n-, sec-, and iso-butanol flames are largely sensitive to hydrogen/carbon monoxide (H2/CO) and C1–C2 hydrocarbon kinetics, not to fuel-specific reactions. In contrast, tert-butanol shows notable sensitivity to its own decomposition pathways [15].

Reaction path analysis traces the dominant consumption routes of the parent fuel and the formation of key intermediates. For example, in tert-butanol flames, a major intermediate is iso-butene, which subsequently forms the resonantly stable iso-butenyl radical. This stability retards the overall reactivity, explaining its significantly lower LBV compared to other butanol isomers [15]. For ammonia flames, adding NO actively participates in the reaction network, promoting radical formation (H, OH) through pathways like NH2 + NO = NNH + OH and NNH = N2 + H, thereby accelerating chain-branching and enhancing LBV [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Equipment for LBV Research

| Item | Function/Description | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Constant Volume Combustion Chamber | Rigid vessel for studying outwardly propagating spherical flames under controlled conditions. | Used for NH3/N2O/N2 [18] and butene isomers [17]. |

| Heat Flux Burner | Perforated plate burner for stabilizing adiabatic, stretch-free flat flames for direct LBV measurement. | Used for NH3/CH4/O2/NO/CO2 flames [19]. |

| Counterflow Burner | Setup for stabilizing twin premixed flames in a stagnation flow field for extinction-based measurements. | Used for butanol [15] and butene isomers [17]. |

| High-Speed Schlieren/Shadowgraph | Optical system for visualizing flame front topology and tracking its propagation. | Essential for constant volume bomb method [16] [17]. |

| Chemical Kinetic Mechanisms | Detailed sets of reactions and species used to simulate and interpret combustion chemistry. | E.g., CEU-1.2 for NH3/N2O [18], Konnov mechanism for C3H6O isomers [16]. |

| High-Purity Gases & Vaporization System | Ensures precise mixture preparation; vaporization system is critical for liquid fuels. | Noted in butanol [15] and ammonia studies [18] [19]. |

The experimental data and kinetic analyses presented in this guide consistently demonstrate that molecular structure is a primary determinant of laminar burning velocity. Key structural factors include the degree of branching, as seen in the butanol and butene series, where increased branching generally correlates with reduced LBV. The presence and type of oxygenated functional groups (e.g., ether, aldehyde, ketone) also create distinct kinetic pathways that significantly influence global reactivity. Furthermore, the interaction between fuel and oxidizer chemistry, such as the promoting effect of NO in ammonia flames, highlights that the reaction environment itself can be tailored to overcome inherent fuel reactivity limitations. A deep understanding of these structure-induced variations, gained through a combination of precise experimental measurement and robust kinetic modeling, is essential for the intelligent selection and design of next-generation fuels and the optimization of combustion systems for efficiency and reduced environmental impact.

The Negative Temperature Coefficient (NTC) region represents a critical and counterintuitive phenomenon in combustion chemistry where the global reaction rate of a fuel decreases with increasing temperature over a specific intermediate temperature range (typically between 650-950 K). This behavior stands in direct opposition to the classical Arrhenius law, which predicts a monotonic increase in reaction rate with temperature. The NTC region emerges from the complex competition between elementary reaction pathways available to peroxy radicals (RO₂) formed after the initial O₂ addition to fuel radicals. At lower temperatures, the reaction mechanism favors chain-branching pathways via isomerization of RO₂ to hydroperoxyalkyl radicals (Q̇OOH), which subsequently decompose to form highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (OH) that accelerate oxidation. However, as temperature increases within the NTC region, the dominant reaction pathways shift toward alternative channels that produce less reactive species, particularly through the decomposition of RO₂ radicals to yield olefins and HO₂ radicals, thereby decreasing the overall system reactivity and creating the characteristic NTC behavior [21] [22].

Understanding the NTC region is fundamentally important for developing accurate kinetic models that predict ignition timing in advanced combustion engines, particularly for gasoline compression ignition (GCI) and homogeneous charge compression ignition (HCCI) engines where fuel autoignition is precisely controlled. The presence and characteristics of the NTC region significantly influence ignition delay times and combustion phasing, directly impacting engine efficiency and emissions. Furthermore, the NTC behavior varies substantially among different fuel structures, including isomers with identical chemical formulas but distinct molecular architectures, making comparative studies of isomer oxidation particularly valuable for fuel design and optimization [23]. This review systematically compares the NTC characteristics of various fuel isomers based on experimental and kinetic modeling studies, providing insights essential for both fundamental combustion science and practical fuel development.

Comparative Analysis of NTC Behaviors in Fuel Isomers

C9H12 Aromatic Isomers

Aromatic hydrocarbons represent crucial components in practical fuels, with C9H12 isomers serving as important surrogate components for jet fuels and gasoline. Experimental studies using jet-stirred reactors (JSR) at high pressure (12 atm) have revealed significant differences in the low-temperature oxidation behaviors and NTC characteristics of three C9H12 isomers: n-propylbenzene (A1C3H7), 1,3,5-trimethylbenzene (T135MB), and 1,2,4-trimethylbenzene (T124MB). These structural differences profoundly impact their oxidation characteristics, as summarized in Table 1 [24].

Table 1: Comparison of NTC Behaviors in C9H12 Isomers

| Isomer | Molecular Structure | NTC Behavior | Low-Temperature Reactivity | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-Propylbenzene (A1C3H7) | Benzene ring with n-propyl chain | Pronounced two-stage oxidation | Highest reactivity | Clear low-temperature oxidation activity with distinct NTC region |

| 1,2,4-Trimethylbenzene (T124MB) | Benzene ring with three methyl groups in 1,2,4-positions | Pronounced NTC behavior | Moderate reactivity | Exhibits classic NTC characteristics under fuel-lean conditions |

| 1,3,5-Trimethylbenzene (T135MB) | Benzene ring with three methyl groups in symmetric 1,3,5-positions | No significant NTC behavior | Lowest reactivity | Lacks substantial low-temperature oxidation activity |

The distinct NTC behaviors observed among these isomers underscore how molecular structure dictates reaction pathways. A1C3H7, with its longer alkyl chain, provides more favorable sites for O₂ addition and subsequent isomerization reactions that enable low-temperature chain branching. In contrast, T135MB, with its symmetric structure and only methyl substituents, offers fewer favorable pathways for the isomerization reactions necessary to sustain low-temperature oxidation chains. T124MB occupies an intermediate position, where the asymmetric arrangement of methyl groups creates more favorable sites for oxidation compared to T135MB, but less than A1C3H7. These structural considerations are essential when formulating surrogate fuels intended to match the combustion characteristics of complex practical fuels like RP-3 kerosene [24].

Polyoxymethylene Dimethyl Ether (DMMn) Isomers

Polyoxymethylene dimethyl ethers (DMMn) have attracted significant interest as potential alternative fuels or fuel additives due to their favorable properties for reducing soot emissions. Comparative studies of DMM1 (dimethoxymethane, CH₃OCH₂OCH₃), DMM2 (CH₃O(CH₂O)₂CH₃), and DMM3 (CH₃O(CH₂O)₃CH₃) have revealed important differences in their low-temperature oxidation characteristics, as summarized in Table 2 [21].

Table 2: Comparison of NTC Behaviors in DMMn Isomers

| Isomer | Molecular Formula | Oxygen Content | NTC Behavior | Low-Temperature Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMM1 | C₃H₈O₂ | 42.1% | No obvious low-temperature reactivity | Oxidative decomposition after dehydrogenation |

| DMM2 | C₄H₁₀O₃ | 45.3% | Weak NTC process | Strong low-temperature oxidation reactions |

| DMM3 | C₅H₁₂O₄ | 47.1% | Weak NTC process | Strong low-temperature oxidation reactions |

The absence of significant low-temperature reactivity in DMM1, compared to the observable NTC behaviors in DMM2 and DMM3, highlights the critical role of molecular size and structure in determining oxidation pathways. The additional oxymethylene (-CH₂O-) units in DMM2 and DMM3 create more possibilities for O₂ addition and subsequent isomerization reactions that enable low-temperature oxidation chains. Importantly, CH₃OCHO and COCOC*O have been identified as crucial intermediates in the low-temperature oxidation processes of DMM1-3, with their concentrations varying systematically with equivalence ratio and molecular structure. These findings provide valuable insights for developing kinetic models that accurately predict the combustion characteristics of these oxygenated fuels across a wide temperature range [21].

Experimental Methodologies for Studying NTC Behavior

Jet-Stirred Reactor (JSR) Systems

The jet-stirred reactor (JSR) has emerged as a fundamental experimental tool for investigating low-temperature oxidation chemistry and NTC behaviors due to its ability to maintain homogeneous reaction conditions with precise control over temperature, pressure, and residence time. In a typical JSR experiment, the fuel-oxidizer mixture is introduced through multiple high-velocity jets that create intense turbulence, ensuring perfect mixing and uniform temperature distribution throughout the reactor volume. This well-defined environment allows researchers to measure species concentrations as a function of temperature across the NTC region, providing essential validation data for kinetic models [21] [24] [25].

Standard JSR experimental protocols involve operating the reactor across a temperature range that encompasses the low-temperature oxidation, NTC, and high-temperature oxidation regimes (typically 500-1100 K), with careful control of parameters including equivalence ratio (usually ranging from fuel-lean to fuel-rich conditions, Φ = 0.5-2.0), pressure (from atmospheric to engine-relevant pressures up to 12 atm or higher), and residence time (typically 0.5-2 seconds). Species sampling and analysis are most commonly performed using gas chromatography (GC) coupled with various detection methods, including mass spectrometry (MS) and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). More advanced setups incorporate synchrotron vacuum ultraviolet photoionization mass spectrometry (SVUV-PIMS), which enables isomer-specific detection of reactive intermediates and oxidation products with minimal fragmentation [21] [25].

For the study of C9H12 isomers, researchers have employed high-pressure JSR systems operating at 12.0 atm with a fixed equivalence ratio of 0.4 (fuel-lean conditions) and temperature ramping from 500 to 1020 K. The fuel components are typically introduced as a vaporized mixture with the oxidizer (air or O₂ in N₂), with the total fuel concentration maintained at approximately 0.2% mole fraction to minimize secondary reactions. For DMMn isomers, JSR experiments are commonly conducted at atmospheric pressure across equivalence ratios of 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0, with temperature ranging from 500 to 950 K and a fixed residence time of 2 seconds. These systematic variations in experimental conditions provide comprehensive datasets for developing and validating kinetic models across the parameter space relevant to practical combustion systems [21] [24].

Complementary Experimental Techniques

While JSR systems provide essential data on species concentrations versus temperature, other experimental methods offer complementary insights into NTC behaviors. Rapid compression machines (RCMs) measure ignition delay times at elevated pressures (10-50 bar) and temperatures (650-900 K) directly within the NTC region, providing critical validation targets for kinetic models under conditions closely replicating engine environments. Similarly, shock tubes extend these measurements to higher temperatures and shorter time scales. For example, studies of C9H12 isomers using RCMs and shock tubes have confirmed that A1C3H7 and T124MB exhibit shorter ignition delays than T135MB in the NTC region, consistent with JSR observations of their relative reactivities [24].

Additionally, thermogravimetric analyzers (TGA) and differential scanning calorimeters (DSC) provide information on heat release patterns and mass changes during low-temperature oxidation, which can help identify temperature ranges where exothermic reactions accelerate or decelerate due to NTC behavior. These techniques are particularly valuable for studying heavier fuels and complex fuel mixtures where detailed speciation may be challenging [26].

Kinetic Modeling of NTC Behaviors

Fundamental Chemical Mechanisms

The NTC phenomenon arises from the temperature-dependent competition between various reaction pathways available to peroxy radicals (RȮ₂) formed after molecular oxygen addition to alkyl radicals (R∙). At lower temperatures (typically < 750 K), the RȮ₂ radicals preferentially undergo internal hydrogen atom isomerization to form hydroperoxyalkyl radicals (Q̇OOH), which can then decompose via two competitive pathways: (1) chain-propagation through olefin and HO₂ formation, or (2) chain-branching through a second O₂ addition followed by decomposition to carbonyl species, cyclic ethers, and, most importantly, highly reactive OH radicals. The chain-branching pathway dominates at lower temperatures, leading to high system reactivity [22].

As temperature increases into the NTC region, the decomposition of RȮ₂ radicals directly to olefins and HO₂ radicals becomes increasingly favored due to its higher activation energy compared to the isomerization reactions. Since HO₂ radicals are significantly less reactive than OH radicals, this shift in dominant pathways reduces the overall system reactivity, creating the characteristic decrease in global reaction rate with increasing temperature. At even higher temperatures (typically > 950 K), hydrogen abstraction reactions by H and OH radicals become dominant, producing highly reactive HȮ₂ radicals that restore the normal positive temperature dependence of reaction rates [22].

Recent theoretical and kinetic modeling studies on cyclohexane oxidation have revealed the crucial influence of conformational structures on low-temperature oxidation chemistry. For cyclohexyl radicals, the chair and twist-boat conformations lead to distinct RȮ₂ adducts (chair-axial, twist-boat-axial, and twist-boat-isoclinal) with different preferences for specific isomerization reactions. For instance, both axial and isoclinal preferences facilitate 1,5-H transfer reactions, while only the twist-boat-isoclinal conformation enables 1,6-H transfer. These subtle structural effects highlight the importance of considering conformational complexity in developing accurate kinetic models for NTC behaviors [22].

Model Development and Validation Approaches

Developing accurate kinetic models for predicting NTC behaviors requires careful consideration of reaction classes including H-atom abstraction from the parent fuel by small radicals (HȮ₂, CH₃, OH, etc.), RȮ₂ isomerization through internal H-atom transfer, decomposition of Q̇OOH radicals, and second O₂ addition reactions. For aromatic compounds like the C9H12 isomers, additional complexity arises from the presence of both aromatic ring H-atoms and aliphatic side-chain H-atoms with different bond dissociation energies and reaction pathways [24].

Modern kinetic model development typically follows a hierarchical approach where submechanisms for individual fuel components are first validated against experimental data (JSR species profiles, ignition delay times, flame speeds) before being combined into comprehensive models for multi-component mixtures. For the C9H12 isomers, detailed kinetic models containing thousands of species and reactions have been developed, validated, and shown to successfully reproduce experimental observations of their distinct NTC behaviors. These models reveal that A1C3H7, despite being the most reactive isomer as a pure component, is consumed more slowly than T135MB and T124MB during the oxidation of surrogate fuel mixtures in stages II and III, highlighting the complex interactions between fuel components in multi-component systems [24].

Similarly, for DMMn isomers, detailed kinetic models have been developed based on analogies with shorter-chain oxygenated compounds, with careful attention to the low-temperature oxidation reactions specific to each molecular structure. These models successfully capture the absence of significant low-temperature reactivity in DMM1 compared to the weak NTC behaviors observed in DMM2 and DMM3, providing mechanistic insights into how molecular structure affects the competition between alternative reaction pathways [21].

Research Reagents and Experimental Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Experimental Tools for Studying NTC Behavior

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Role in NTC Research | Examples/Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Jet-Stirred Reactor (JSR) | Provides homogeneous reaction conditions for measuring temperature-dependent species concentrations | Studying low-temperature oxidation of C9H12 isomers [24] and DMMn compounds [21] |

| Synchrotron VUV Photoionization Mass Spectrometry (SVUV-PIMS) | Enables isomer-specific detection of reactive intermediates and oxidation products with minimal fragmentation | Identification of 29 oxidation species in n-heptanol oxidation [25] |

| Gas Chromatography (GC) | Separates and quantifies stable species in reaction mixtures | Routine analysis of reactants, intermediates, and products in JSR experiments [21] |

| Rapid Compression Machine (RCM) | Measures ignition delay times at engine-relevant conditions (elevated pressure and temperature) | Validation of kinetic models for C9H12 isomers in NTC region [24] |

| Shock Tube | Measures ignition delay times at high temperatures and short time scales | Complementary data to RCM for kinetic model validation |

| Reference Fuels | Well-characterized compounds serving as model fuels for fundamental studies | n-Heptane, cyclohexane, C9H12 isomers [24] [22] |

| Alternative Fuel Components | Oxygenated compounds with potential for reduced emissions | DMMn isomers [21], n-heptanol [25] |

The NTC region in low-temperature oxidation represents a complex chemical phenomenon with significant implications for fuel autoignition and combustion performance in advanced engine concepts. Systematic comparisons of isomer oxidation reveal that molecular structure profoundly influences NTC characteristics through its control of the competition between chain-branching and chain-propagation pathways. Aromatic isomers with longer or less symmetric alkyl substituents (e.g., n-propylbenzene) generally exhibit more pronounced low-temperature reactivity and NTC behaviors compared to their more symmetric counterparts (e.g., 1,3,5-trimethylbenzene). Similarly, among oxygenated fuels, molecular size and structure dictate the availability of favorable pathways for O₂ addition and isomerization, with larger DMMn isomers (DMM2, DMM3) showing weak NTC behaviors absent in the smaller DMM1.

Advanced experimental techniques, particularly jet-stirred reactors coupled with sophisticated analytical methods like SVUV-PIMS, provide essential data for developing and validating detailed kinetic models that accurately capture NTC behaviors across temperature, pressure, and equivalence ratio parameter space. These models reveal the critical role of conformational effects and temperature-dependent competition between reaction pathways in producing the characteristic NTC phenomenon. The continued refinement of these experimental and modeling approaches, coupled with systematic comparisons of isomer oxidation, will enable the development of more predictive combustion models and the design of advanced fuels optimized for next-generation, high-efficiency, low-emission combustion technologies.

Synchrotron Vacuum Ultraviolet Photoionization Mass Spectrometry (SVUV-PIMS) has emerged as a premier analytical technique for identifying key intermediate species in complex chemical processes, particularly in combustion chemistry and catalytic reactions. This technique leverages synchrotron-generated vacuum ultraviolet light as an ionization source, coupled with mass spectrometry, to achieve unprecedented detail in detecting and quantifying reactive intermediates. The fundamental advantage of SVUV-PIMS lies in its ability to minimize fragmentation interference, distinguish between structural isomers, and detect elusive radical species that are crucial for understanding reaction mechanisms at a molecular level [27]. These capabilities provide invaluable experimental data for developing and validating detailed chemical kinetic models that predict behavior in combustion systems, atmospheric chemistry, and materials synthesis.

The application of mass spectrometry in combustion diagnostics dates back over half a century, but earlier methods relying on electron-impact (EI) ionization sources suffered from significant limitations in energy resolution. Traditional EI-based molecular beam mass spectrometry (EI-MBMS) made species identification laborious and often impossible to distinguish between isomers due to fragmentation patterns and overlapping signals [27]. The development of synchrotron VUV photoionization overcame these limitations by providing a tunable, high-intensity photon source with superior energy resolution, enabling isomer-specific detection through photoionization efficiency (PIE) measurements and precise ionization energy determinations [27] [28].

Technical Principles and Comparative Advantages

Fundamental Mechanisms of SVUV-PIMS

The operational principle of SVUV-PIMS centers on the photoionization process, where tunable VUV light interacts with chemical species in a molecular beam, ejecting electrons and creating ions. The kinetic energy of these photons can be precisely controlled to match the ionization energies of specific compounds, allowing for selective ionization. The resulting ions are then separated by their mass-to-charge ratio in a time-of-flight mass spectrometer and detected [29]. A critical component of this technique is molecular-beam sampling, which involves extracting species from reaction environments (such as flames or reactors) through a series of skimmers into vacuum chambers, effectively freezing the chemical reactions and preserving the composition of reactive intermediates for analysis [27].

The photoionization efficiency spectrum, which plots ion signal as a function of photon energy, serves as a molecular fingerprint for unambiguous identification. Each chemical species has a characteristic ionization threshold, and the shape of the PIE curve provides additional structural information. By scanning the photon energy across appropriate ranges and measuring the appearance energies of different masses, researchers can identify multiple isomers simultaneously in complex mixtures—a capability that sets SVUV-PIMS apart from conventional mass spectrometry techniques [27] [28].

Comparative Analysis with Alternative Techniques

Table 1: Comparison of SVUV-PIMS with Other Analytical Techniques for Intermediate Detection

| Technique | Isomer Discrimination | Radical Detection | Fragmentation Interference | Quantitative Capability | Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVUV-PIMS | Excellent (via IE/PIE) | Excellent | Minimal | Good (with cross-sections) | High |

| EI-MBMS | Poor | Moderate | Significant | Moderate | Moderate |

| GC-MS | Excellent | Poor | Minimal | Excellent | High |

| LIMS | Moderate | Excellent | Moderate | Challenging | Moderate |

When compared to electron impact ionization methods, SVUV-PIMS provides significantly softer ionization, which substantially reduces fragmentation that often complicates mass spectral interpretation [27]. While gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) offers excellent isomer separation capabilities, it cannot detect highly reactive radical species and requires stable, condensable samples [30]. Laser ionization mass spectrometry (LIMS) can detect radicals but lacks the tunability for precise isomer discrimination. SVUV-PIMS thus occupies a unique position in the analytical landscape, combining the radical detection capability of laser methods with the isomer specificity of chromatographic techniques.

The integration of SVUV-PIMS with complementary techniques like GC-MS creates a particularly powerful analytical approach. As demonstrated in recent research on benzyl self-reaction, SVUV-PIMS can identify reactive intermediates in situ, while GC-MS provides ex-situ validation and identification of stable products and isomers with nearly identical ionization energies [30]. This combined approach overcomes individual technique limitations and provides comprehensive mechanistic insights.

Application Case Studies in Isomer Oxidation Research

Detection of Radical Intermediates in Oxidative Coupling of Methane

A compelling demonstration of SVUV-PIMS capabilities comes from its application to the oxidative coupling of methane (OCM) reaction. Researchers successfully detected gas-phase methyl radicals (CH₃•) during OCM catalyzed by Li/MgO catalysts, providing direct experimental evidence for a long-proposed reaction mechanism [28]. The identification was achieved by measuring the photoionization efficiency spectrum for m/z = 15, which showed an ionization threshold of 9.80 eV—matching exactly the known ionization energy of methyl radicals [28].

The concentration of detected methyl radicals correlated well with the yield of ethylene and ethane products, strongly supporting the mechanism wherein methane activation on the catalyst surface generates methyl radicals that subsequently couple in the gas phase to form C₂ products [28]. This direct detection of methyl radicals resolved a longstanding question in OCM reaction mechanisms and demonstrated how SVUV-PIMS can provide crucial evidence for theoretical models. Without the tunable VUV photoionization source and the minimal fragmentation of the technique, unambiguous identification of these transient radicals would not have been possible.

Isomer-Specific Analysis in Benzyl Self-Reaction Pathways

In investigations of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) formation mechanisms, SVUV-PIMS has provided exceptional insights into isomer-specific pathways. Studies of benzyl (C₇H₇) radical self-reactions revealed the formation of multiple C₁₄H₁₄, C₁₄H₁₂, and C₁₄H₁₀ isomers, including previously unrecognized products [30]. The technique enabled identification of o-tolyl radical (o-C₇H₇) as a reaction isomer and detected several C₁₄H₁₀ products including diphenylacetylene, phenanthrene, and anthracene [30].

Table 2: Key Intermediates and Products Identified in Benzyl Self-Reaction Using SVUV-PIMS

| Mass | Species | Isomers Identified | Ionization Energy (eV) | Role in Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C₇H₇ | Radical | benzyl, o-tolyl | ~7.5-8.0 (varies by isomer) | Initial reactant |

| C₁₄H₁₄ | Intermediate | 1-benzyl-2-methylbenzene | 8.43 (cal.) | Initial adduct |

| C₁₄H₁₂ | Intermediate | 9,10-dihydrophenanthrene | 7.66 (exp.) | Dehydrogenation product |

| C₁₄H₁₀ | Product | phenanthrene, anthracene, diphenylacetylene | 7.43-7.89 (exp.) | Final PAH products |

These isomer-resolved measurements allowed researchers to distinguish between competing reaction pathways on electronic ground-state and excited-state potential energy surfaces. The absence of key intermediates from proposed excited-state pathways, combined with theoretical calculations, enabled the identification of new facile reaction routes that contribute to enhanced anthracene production [30]. This case study highlights how SVUV-PIMS data can challenge existing mechanistic assumptions and guide computational chemistry toward more accurate models.

Low-Temperature Oxidation Intermediates in Ether Chemistry

The application of SVUV-PIMS to diethyl ether (DEE) oxidation revealed several key reactive intermediates that are crucial for understanding low-temperature oxidation mechanisms. Using multiplexed photoionization mass spectrometry (MPIMS) with tunable VUV radiation, researchers directly detected and quantified peroxy (ROO•), hydroperoxyalkyl peroxy (•OOQOOH), and ketohydroperoxide (HOOP=O) intermediates [31].

These species undergo dissociative ionization into smaller fragments, making their identification by conventional mass spectrometry challenging. However, with tunable VUV photoionization and support from quantum chemical calculations, the researchers identified the dissociative ionization channels of these key chemical species and quantified their time-resolved concentrations [31]. This enabled the determination of absolute photoionization cross-sections for ROO•, •OOQOOH, and ketohydroperoxide species directly from experimental data, providing crucial parameters for future quantitative studies of low-temperature oxidation kinetics.

Experimental Methodology and Workflow

Core Experimental Setup and Protocols

The typical SVUV-PIMS apparatus consists of three main components: (1) a reaction chamber (flow reactor, flame setup, or catalytic microreactor), (2) a differentially pumped molecular-beam sampling system, and (3) the photoionization time-of-flight mass spectrometer [27] [28]. The molecular-beam sampling system employs a series of skimmers and vacuum chambers to extract species from the reaction environment while maintaining high vacuum for mass spectrometric analysis. This sampling approach effectively "freezes" the chemical composition by rapidly cooling and isolating the species from the reaction zone [27].

For data acquisition, two primary measurement modes are employed: mass scans at fixed photon energy and photoionization efficiency scans at fixed mass. In mass spectrum mode, the photon energy is set to a fixed value (typically above the ionization thresholds of expected species), and the complete mass spectrum is recorded. In PIE mode, the photon energy is scanned across a specific range while monitoring the ion signal for a selected mass, producing the photoionization efficiency curve that serves for identification [29]. The experimental data processing involves converting arrival time to mass-to-charge ratio, background subtraction, and correction for photon flux variations using a photodiode [29].

Diagram 1: SVUV-PIMS Experimental Workflow illustrating the integration of reaction systems with synchrotron ionization and mass spectrometric detection.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Experimental Components

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Experimental Components for SVUV-PIMS

| Component | Function | Specific Examples | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synchrotron Light Source | Provides tunable VUV radiation | Advanced Light Source (ALS), National Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (NSRL) | Energy range: 7.8-24.0 eV; Resolution: ΔE/E ~ 1-2% |

| Molecular Beam Sampling System | Extracts species from reaction environment | Nozzle (100 μm orifice), Skimmer (2 mm) | Maintains pressure differential; Freezes chemical reactions |

| Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometer | Separates ions by mass-to-charge ratio | Reflectron TOF-MS | Mass resolution: m/Δm ~ 2000-4000 |

| Photoionization Detectors | Measures photon flux | Silicon photodiode | Required for photon flux normalization |

| Microreactors | Controlled reaction environments | Tubular SiC reactor, Jet-stirred reactor | Temperature range: 300-1700 K; Pressure: 10⁻³ to 10⁴ Pa |

| Calibration Compounds | Photoionization cross-section reference | Toluene, 1,3-dimethyluracil, DNA bases | Essential for quantitative measurements |

The experimental setup requires careful calibration and optimization at multiple stages. The mass spectrometer must be calibrated using known compounds to establish the relationship between arrival time and mass-to-charge ratio [29]. The photon energy scale requires calibration using standard gases with well-known ionization energies [28]. For quantitative measurements, photoionization cross-sections must be determined or obtained from reference databases, though these are not available for all species, particularly novel intermediates [31].

Current Research Trends and Future Perspectives

The application of SVUV-PIMS continues to expand into new research areas and technical implementations. Recent developments include the combination with gas chromatography in an isomer-resolved method that provides complementary separation capabilities [30]. This hybrid approach addresses the limitation of SVUV-PIMS in discriminating isomers with nearly identical ionization energies by adding a chromatographic separation dimension before analysis.

Another significant trend is the extension of SVUV-PIMS to increasingly complex chemical systems, including pyrolysis of biomass and bio-derived fuels [27], oxidation of larger hydrocarbon fuels [32] [33], and the formation mechanisms of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and soot precursors [27] [30]. The technique is also being applied to heterogeneous catalytic systems beyond traditional combustion environments, as demonstrated by the OCM study [28].

Diagram 2: Research applications and methodological extensions of SVUV-PIMS in modern chemical kinetics.

Future developments will likely focus on improving sensitivity for trace-level intermediates, enhancing energy resolution for better isomer discrimination, and developing faster data acquisition methods for time-resolved studies. The integration of SVUV-PIMS with theoretical chemistry and computational kinetics will continue to strengthen, with experimental data providing crucial validation for theoretical predictions and guiding the development of more accurate kinetic models [30] [32]. As synchrotron facilities become more accessible worldwide, SVUV-PIMS is poised to become an increasingly standard technique for unraveling complex reaction mechanisms across diverse chemical disciplines.

Synchrotron VUV Photoionization Mass Spectrometry represents a powerful analytical tool that has fundamentally advanced our ability to detect and identify key intermediate species in complex chemical environments. Its unique capabilities in isomer discrimination, radical detection, and minimal fragmentation interference provide crucial advantages over traditional analytical methods. Through applications in combustion chemistry, catalytic mechanism studies, and pyrolysis research, SVUV-PIMS has yielded unprecedented insights into reaction pathways and enabled the development of more accurate kinetic models. As technical innovations continue to emerge and synergies with complementary techniques strengthen, SVUV-PIMS will remain at the forefront of experimental chemical kinetics, driving discoveries in energy conversion, environmental science, and fundamental reaction mechanisms.

In the development of cleaner, more efficient combustion systems and the utilization of alternative fuels, a precise understanding of fuel consumption pathways is paramount. The molecular structure of a fuel dictates its reaction chemistry, influencing ignition, flame propagation, and emissions formation. Among the myriad of possible initial reactions, three consumption mechanisms are fundamentally important across a wide range of fuels: hydrogen (H-) abstraction, unimolecular decomposition, and dehydration (particularly for oxygenated fuels). The competition between these pathways controls the distribution of reactive radicals and stable intermediates, thereby steering the entire combustion process.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of these dominant consumption channels, framing the discussion within the context of comparative experimental and kinetic modeling of isomer oxidation. The objective is to equip researchers and scientists with a clear understanding of how molecular structure influences dominant reaction chemistry, supported by quantitative data and detailed methodologies from current literature.

Comparative Analysis of Consumption Pathways

The competition between H-abstraction, unimolecular decomposition, and dehydration is highly sensitive to molecular structure and combustion conditions. The table below summarizes the characteristics and dominance of each pathway for different fuel types.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Dominant Consumption Pathways

| Fuel Category | Dominant Pathway(s) at High Temperature | Key Radicals / Products | Impact on Reactivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary Amine (Diethylamine) | H-Abstraction (at C site near N, low-to-med T) → Unimolecular Decomposition (C-C dissociation, high T) [34] | Radicals: C2H5, CH3 |

High reactivity due to radical chain branching [34] |

| n-/iso-Alkanes (e.g., Octane Isomers) | H-Abstraction (followed by low-T oxidation pathway) [35] [36] | Alkyl radicals (R•), Q˙OOH |

Determines low-temperature ignition propensity [36] |

| 1-butanol / iso-butanol | H-Abstraction (primary consumption) [37] | Highly reactive radicals (H, OH) |

Higher reactivity [37] |

| 2-butanol / tert-butanol | Dehydration (primary consumption) [37] | Alkenes (e.g., C4H8), resonance-stabilized radicals |

Lower reactivity [37] |

| Propanol Isomers | H-Abstraction vs. Dehydration (highly dependent on hydroxyl group position and α-H BDE) [38] | Aldehydes vs. alkenes | Dictates intermediate speciation and overall oxidation profile [38] |

Experimental Data and Kinetic Modeling

Quantitative Rate Constants for Diethylamine

A theoretical kinetic study on diethylamine (DEA) provides high-pressure limit rate constants for its consumption pathways, offering a quantitative basis for comparison.

Table 2: Theoretical Rate Constants for Diethylamine (DEA) Consumption Pathways [34]

| Reaction Class | Specific Reaction | Temperature Range (K) | Theoretical Method | Dominance Condition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H-Abstraction | DEA + H, O, OH, HO2, CH3 |

Low-to-intermediate | CVT/TST with MS-TAnh and SCT/Wigner Tunneling | Dominant at low-to-intermediate temperatures |

| Unimolecular Decomposition | 1,3-elimination, 1,2-H transfer | - | SS-QRRK/MSC-Dean | Dominant at low-to-intermediate temperatures |

| Unimolecular Decomposition | C–C and C–N bond dissociations | High | Variable Reaction-Coordinate TST (VRC-TST) | Dominant at high temperatures |

Isomer-Dependent Pathway Branching in Butanols

Experimental shock tube studies and kinetic modeling of the four butanol isomers reveal how molecular structure shifts the dominant consumption mechanism.

Table 3: Consumption Pathway Branching for Butanol Isomers at High Temperature [37]

| Fuel Isomer | Primary Consumption Pathway | Key Product Species | Measured Reactivity (Ignition Delay Time) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-butanol | H-atom abstraction | Reactive radicals (H, OH) |

Higher Reactivity (Shorter Ignition Delay) |

| iso-butanol | H-atom abstraction | Reactive radicals (H, OH) |

Higher Reactivity (Shorter Ignition Delay) |

| 2-butanol | Dehydration | Alkenes (C4H8), resonance-stabilized radicals |

Lower Reactivity (Longer Ignition Delay) |

| tert-butanol | Dehydration | Alkenes (C4H8), resonance-stabilized radicals |

Lower Reactivity (Longer Ignition Delay) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Theoretical Kinetics Protocol for Pathway Analysis

The following methodology, as applied in the diethylamine study, is representative of high-level theoretical kinetic analysis [34]:

Quantum Chemical Calculations:

- Geometry Optimization: Molecular geometries of reactants, transition states, and products are optimized at the M06-2X/def2-TZVP level of theory.

- Energy Benchmarking: Electronic energies are refined using high-level methods like DLPNO-CCSD(T) with complete basis set (CBS) extrapolations to achieve chemical accuracy (< 1.0 kcal mol⁻¹).

- Method Validation: Cost-effective computational methods are benchmarked against the high-level method to ensure accuracy for larger systems.

Rate Constant Calculation:

- Tight Transition States: For reactions with well-defined, tight saddle points (H-abstraction, eliminations), high-pressure limit rate constants are determined using Canonical Variational Transition-State Theory (CVT).

- Tunneling and Anharmonicity: Critical corrections are applied, including Multi-Structural Torsional Anharmonicity (MS-T) and Small-Curvature Tunneling (SCT).

- Pressure Dependence: For bond dissociation reactions and other pressure-sensitive unimolecular decompositions, pressure-dependent rate constants are calculated using the System-Specific Quantum Rice–Ramsperger–Kassel (SS-QRRK) method with a Modified Strong Collision (MSC) model.

Kinetic Model Integration: The calculated rate parameters are integrated into a detailed kinetic model, which is validated against available experimental data (e.g., ignition delay times, species profiles).

Experimental Ignition Delay Measurement Protocol

Ignition delay time (IDT) is a key metric for validating kinetic models. A standard protocol using a rapid compression machine (RCM) and shock tube is outlined below, consistent with methodologies in the search results [35] [36].

Facility and Instrumentation:

- Rapid Compression Machine (RCM): A twin opposed-piston design is used to achieve high-pressure and temperature conditions nearly adiabatically, with a typical compression time of ~17 ms. Pressure is recorded using a high-frequency transducer (e.g., Kistler 6045B).

- High-Pressure Shock Tube (HPST): A heated driver section and a driven section separated by a diaphragm. Rupturing the diaphragm creates a shock wave that instantaneously heats and compresses the test gas mixture.

Mixture Preparation: Fuel/O₂/inert gas (usually N₂ or Ar) mixtures are prepared manometrically in a specialized mixing vessel at specified equivalence ratios (Φ). The mixture is allowed to homogenize for at least 24 hours.

Experimental Procedure:

- The reaction vessel (RCM or HPST test section) is evacuated and then filled with the test mixture to a specified initial pressure (

P₀) and temperature (T₀). - In the RCM, the pistons are released, rapidly compressing the gas to the compressed pressure (

P_c) and temperature (T_c). In the HPST, the diaphragm is burst, creating the shock wave. - The pressure history is recorded at high frequency. The ignition delay time (

τ) is defined as the time interval from the end of compression (RCM) or the shock wave passing the endwall (HPST) to the subsequent rapid pressure rise associated with ignition.

- The reaction vessel (RCM or HPST test section) is evacuated and then filled with the test mixture to a specified initial pressure (

Diagram 1: Integrated computational and experimental workflow for identifying dominant consumption pathways in fuel isomers.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Combustion Kinetics Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example from Context |

|---|---|---|

| Radical Scavengers (H, O, OH, HO₂, CH₃) | Reactants in H-abstraction studies; critical for mapping site-specific reactivity [34]. | Used to calculate rate constants for H-abstraction from Diethylamine [34]. |

| High-Purity Fuel Isomers | Enable the isolation of molecular structure effects on reaction pathways and global reactivity [36] [37]. | 2,3,4-Trimethylpentane vs. iso-octane; Butanol isomers (1-, 2-, iso-, tert-) [36] [37]. |

| Inert Bath Gas (N₂, Ar, He) | Serves as a diluent to control temperature and pressure during experiments; used in shock tubes and RCMs. | Argon used in shock tube studies of butanol isomers; N₂ used as diluent in 'air' mixtures for octane isomer ignition studies [35] [37]. |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Calculates thermochemical parameters (enthalpy, entropy) and optimizes molecular geometries for kinetic theory input. | Used to calculate thermochemistry for octane isomer sub-mechanisms at CCSD(T)-F12//B2PLYPD3 level [35] [36]. |

| Kinetic Modeling Software | Solves complex reaction networks; integrates experimental data with theoretical kinetics for model validation and prediction. | Used to develop and validate models for octane and propanol isomers against IDT and speciation data [35] [36] [38]. |

The dominant initial consumption pathway of a fuel—be it H-abstraction, unimolecular decomposition, or dehydration—is a direct consequence of its molecular architecture and the prevailing combustion conditions. The consistent finding across multiple fuel classes is that H-abstraction, particularly from the most vulnerable C-H bonds, tends to promote higher reactivity by generating radical chain carriers. In contrast, dehydration and certain unimolecular decomposition channels often lead to more stable, less reactive intermediates like alkenes and resonance-stabilized radicals, thereby reducing global reactivity.

This comparative guide underscores the power of integrating high-level theoretical kinetics with targeted experimental validation to deconvolute complex reaction networks. For researchers in fuel development and engine design, these principles and tools provide a predictive framework for tailoring fuel molecules and optimizing combustion strategies for efficiency and low emissions.

Kinetic Modeling in Practice: From Mechanism Development to Engine-Relevant Conditions

In the field of combustion research, the development of robust kinetic models is essential for predicting fuel behavior and optimizing engine performance. This guide compares contemporary approaches to constructing detailed kinetic models, with a focus on the critical C0-C4 core chemistry and the expanding need for isomer-specific sub-mechanisms. The performance of different model frameworks and experimental protocols is evaluated based on their predictive accuracy, comprehensiveness, and applicability to real-world fuels.

Comparative Analysis of Kinetic Model Frameworks

The table below summarizes the scope and key features of different kinetic modeling approaches, highlighting the trend towards integrating larger core mechanisms with detailed isomer-specific chemistry.

| Model / Study Focus | Core Chemistry Scope | Isomer-Specific & Extended Chemistry | Key Validation Targets | Notable Features & Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C3MechV3.3 (C3 Consortium) [39] | C0 – C4 core mechanism | Hexane isomers, n-heptane, iso-octane, nC8–nC12 alkanes, PAHs, NOx | Ignition delay times, flame speeds, species profiles for natural gas, n-alkanes, PRF, TPRF | Open access; includes pollutant formation; validated over wide range of temperatures & pressures; suitable for complex fuel surrogates [39]. |

| iso-Propanol/THF Oxidation Study [40] | Integrated C0–C4 base mechanism (NUIG1.3) | Sub-mechanisms for C3–C4 alcohols (iso-propanol) and cyclic ethers (Tetrahydrofuran) | Low-temperature oxidation in a Jet-Stirred Reactor (JSR); speciation data for fuels & intermediates | Focus on sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs); reveals chemical interaction & suppression effects in fuel blends [40]. |

| Photopolymerization Kinetics Review [41] | Radical (e.g., from photoinitiators) and cationic propagation kinetics | Not typically isomer-specific; focuses on functional group reactivity (acrylates, epoxides) | Monomer conversion vs. time; cure speed; "dark reaction" kinetics | Focus on material manufacturing; highlights impact of oxygen inhibition & temporal/spatial control [41]. |

A critical trend is the move towards validating models against data from isomer-specific compounds and oxygenated fuels, which is critical for modern fuel design [39] [40]. The C3MechV3.3 model exemplifies a top-down approach, building on a validated core and extending it to larger molecules and pollutants [39]. In contrast, the iso-propanol/THF study demonstrates a bottom-up approach, where a base mechanism is integrated with newly developed or refined sub-mechanisms for specific oxygenated compounds to explain unique low-temperature reactivity and blending effects [40].

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

A model's predictive capability is determined by the quality and breadth of experimental data against which it is validated. Key experimental methods provide distinct data types for kinetic model development and refinement.

Jet-Stirred Reactor (JSR) Speciation Studies

This method is ideal for probing low-temperature oxidation pathways and quantifying intermediate species [40].

- Objective: To obtain detailed speciation data under well-controlled, homogeneous conditions for a wide temperature range (e.g., 500 – 1200 K) at atmospheric pressure [40].

- Protocol:

- Apparatus: A quartz JSR is used, typically equipped with multiple nozzles to ensure perfect mixing of the vaporized fuel/oxidizer mixture. The reactor is coupled to a direct sampling system connected to an analytical instrument like a Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometer (TOF-MS) [40].

- Operation: Experiments are conducted at a fixed pressure (e.g., 1 bar) and equivalence ratio (e.g., ϕ = 0.5 for lean conditions). The temperature is systematically varied across the range of interest [40].

- Data Collection: At each temperature point, the reactor effluent is rapidly sampled. The TOF-MS identifies and quantifies the mole fractions of the stable fuel, intermediates, and final products [40].

- Data Application: The measured mole fraction profiles of species over temperature are used to validate and refine the proposed reaction pathways in a kinetic model, particularly for low-temperature chain-branching and isomerization reactions [40].

Real-Time Fourier-Transformed Infrared (RT-FTIR) Spectroscopy

This technique is a standard for tracking functional group conversion in real-time, especially in polymer curing and oxidation studies [41].