Bridging Theory and Experiment: A Practical Guide to Validating DFT Predictions with Experimental Synthesis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical process of validating Density Functional Theory (DFT) predictions through experimental synthesis.

Bridging Theory and Experiment: A Practical Guide to Validating DFT Predictions with Experimental Synthesis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical process of validating Density Functional Theory (DFT) predictions through experimental synthesis. It covers the foundational principles of DFT, explores its application in material and drug discovery, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, and establishes robust validation frameworks. By synthesizing current methodologies and real-world case studies—from catalytic material design to drug target engagement—this resource aims to enhance the reliability and predictive power of computational approaches in biomedical research and development.

Understanding DFT: Core Principles, Strengths, and Inherent Limitations

The Central Role of DFT in Modern Quantum Mechanics Calculations

Density Functional Theory (DFT) stands as the workhorse of modern quantum mechanics calculations, enabling the investigation of electronic structures in atoms, molecules, and condensed phases across physics, chemistry, and materials science [1]. This computational quantum mechanical modelling method determines properties of many-electron systems using functionals of the spatially dependent electron density, significantly reducing computational costs compared to traditional wavefunction-based methods while maintaining considerable accuracy [1] [2]. The versatility of DFT has led to widespread adoption in industrial and academic research, particularly for calculating material behavior from first principles without requiring higher-order parameters or fundamental material properties [1] [3]. As the scientific community increasingly relies on computational predictions to guide experimental research, validating DFT findings through experimental synthesis has become crucial, especially for applications in catalysis, pharmaceuticals, and energy materials where predictive accuracy directly impacts development timelines and success rates.

Theoretical Foundations of DFT

The theoretical framework of DFT originates from the Hohenberg-Kohn theorems, which demonstrate that all ground-state properties of a quantum system, including the total energy, are uniquely determined by the electron density[n(r)] [1]. The first theorem establishes that the electron density uniquely determines the external potential (save for an additive constant), while the second theorem provides a variational principle for the energy functional E[n(r)] [1]. These theorems reduce the many-body problem of N electrons with 3N spatial coordinates to just three spatial coordinates through functionals of the electron density [1].

Kohn and Sham later introduced a practical computational approach by replacing the original interacting system with an auxiliary non-interacting system that has the same electron density [4]. This formulation leads to the Kohn-Sham equations, which must be solved self-consistently:

[ \left[-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m}\nabla^2 + V{ext}(\mathbf{r}) + V{H}(\mathbf{r}) + V{XC}(\mathbf{r})\right]\psii(\mathbf{r}) = \varepsiloni\psii(\mathbf{r}) ]

where V{ext} is the external potential, V{H} is the Hartree potential, V{XC} is the exchange-correlation potential, and ψi and εi are the Kohn-Sham orbitals and their energies [1] [4]. The electron density is constructed from the Kohn-Sham orbitals: n(r) = Σi|ψ_i(r)|² [1].

The central challenge in DFT implementations is approximating the exchange-correlation functional, with the local-density approximation (LDA) and generalized gradient approximation (GGA) serving as foundational approaches [1] [4]. More sophisticated hybrid functionals incorporate exact Hartree-Fock exchange but require careful validation, as the inclusion of HF exchange can degrade predictive accuracy for certain properties, such as relative isomer energies in copper-peroxo systems [5].

Table 1: Common DFT Functionals and Their Applications

| Functional Type | Representative Functionals | Strengths | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| GGA | PBE, BLYP | Reasonable lattice parameters, fast computation | Solid-state physics, materials science [4] |

| Hybrid | B3LYP, TPSSh, mPW1PW | Improved accuracy for molecular properties | Molecular systems, reaction energies [5] [6] |

| Meta-GGA | TPSS | Better equilibrium geometries | Transition metal systems [5] |

| Range-Separated | ωB97X-D | Improved long-range interactions | Charge transfer excitations [1] |

DFT Validation Framework and Protocols

Validation Methodologies

Validating DFT predictions requires systematic comparison with experimental data across multiple property categories. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) emphasizes comprehensive validation targeting industrially-relevant, materials-oriented systems to address critical questions about functional selection, expected deviation from experimental values, pseudopotential performance, and failure modes [3]. An effective validation protocol encompasses several key aspects:

Structural validation involves comparing DFT-optimized geometries with experimental crystallographic data from X-ray diffraction (XRD) [6]. For example, in studies of chromone-isoxazoline hybrids, DFT calculations successfully optimized geometric structures that aligned with experimental XRD determinations, confirming the regiochemistry of the 3,5-disubstituted isoxazoline ring formation [6].

Energetic validation compares calculated reaction energies, activation barriers, and adsorption energies with experimental measurements. In the study of CuO-ZnO composites for dopamine detection, DFT calculations revealed a reaction energy barrier of 0.54 eV, which correlated with enhanced experimental catalytic performance [7]. Similarly, for Fe-doped CoMn₂O₄ catalysts, DFT predicted a reduction in the energy barrier for NH₃-SCR from 1.11 eV to 0.86 eV, subsequently confirmed by experimental performance testing [8].

Electronic property validation involves comparing calculated band gaps, density of states, molecular orbital energies, and optical properties with experimental spectra [2]. The projected density of states (PDOS) analysis in CuO-ZnO systems demonstrated that the d-band center of Cu moved closer to the Fermi level upon hybridization, explaining the enhanced catalytic activity observed experimentally [7].

Experimental-Computational Workflow

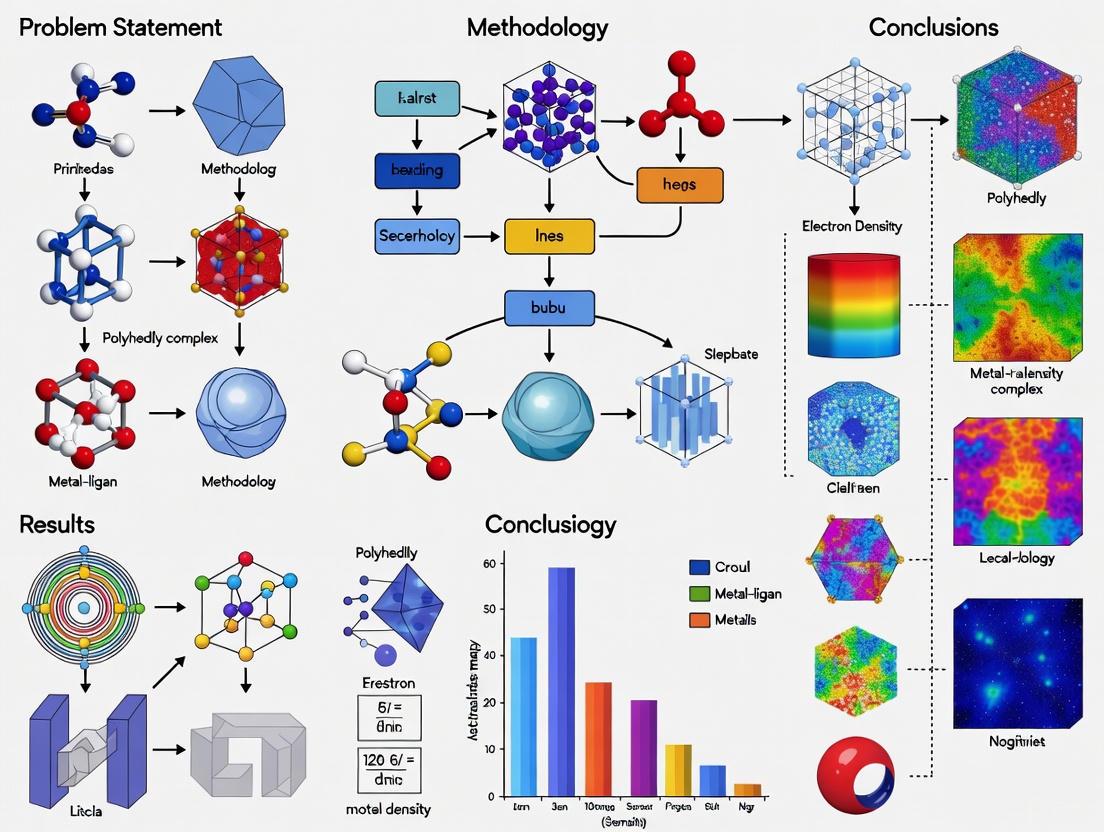

The integration of DFT predictions with experimental validation follows a systematic workflow that ensures robust material design and verification. The diagram below illustrates this iterative process:

Figure 1: DFT-Experimental Validation Workflow

Application Notes: Case Studies in DFT-Guided Material Design

Enhanced Dopamine Sensing with CuO-ZnO Composites

Background and Rationale: Accurate dopamine (DA) quantification in biological fluids is critical for early diagnosis of neurological disorders, with electrochemical sensing representing a promising approach limited by performance constraints of pristine metal oxide sensors [7]. ZnO, while biocompatible with effective electron transport characteristics, suffers from inadequate cycling stability, prompting investigation of composite structures [7].

DFT-Guided Design: Researchers synthesized four CuO-ZnO composites with different morphologies by varying CuCl₂ mass fraction (1%, 3%, 5%, and 7%) during one-step hydrothermal preparation [7]. DFT calculations examined internal structures, reaction energy barriers, and projected density of states (PDOS) [7].

Key DFT Findings:

- Rod-like nanoflowers with 3D structure (3% CuCl₂) exhibited optimal catalytic performance

- Calculated reaction energy barrier: 0.54 eV

- d-band center of Cu shifted closer to Fermi level after hybridization

- Enhanced electron transfer capabilities confirmed through PDOS analysis [7]

Experimental Validation: The CuO-ZnO nanoflowers (3% CuCl₂) were applied in glassy carbon electrode modification for DA electrochemical sensors [7]. Experimental results confirmed excellent detection limit, sensitivity, selectivity, repeatability, and stability, with practical applicability demonstrated in human serum and urine samples [7].

Table 2: DFT Predictions vs. Experimental Results for Catalytic Materials

| Material System | DFT Prediction | Experimental Result | Validation Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| CuO-ZnO nanocomposite | Low reaction energy barrier (0.54 eV) | Enhanced catalytic dopamine oxidation | Strong correlation [7] |

| Fe-doped CoMn₂O₄ | Reduced energy barrier (1.11 eV → 0.86 eV) | Improved NOx conversion (87% at 250°C) | Confirmed enhancement [8] |

| CoFe₀.₁Mn₁.₉O₄ | Enhanced NH₃ adsorption (Eads = -1.29 eV → -1.42 eV) | Increased catalytic activity for NH₃-SCR | Agreement with prediction [8] |

Pharmaceutical Development: Chromone-Isoxazoline Hybrids

Background and Rationale: Molecular hybridization combining chromone and isoxazoline pharmacophores offers potential for developing novel antibacterial and anti-inflammatory agents, addressing critical needs in antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and inflammation management [6].

Computational Protocol: DFT-based calculations optimized geometric structures and analyzed structural and electronic properties of hybrid compounds [6]. These calculations complemented experimental techniques including ¹H-NMR, ¹³C-NMR, mass spectrometry, and XRD analysis [6].

Experimental Synthesis and Validation: Novel chromone-isoxazoline hybrids were synthesized via 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reactions between allylchromone and arylnitrile oxides [6]. Antibacterial activity assessed against Gram-positive (Bacillus subtilis) and Gram-negative bacteria (Klebsiella aerogenes, Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica) showed promising efficacy compared to standard antibiotic chloramphenicol [6]. Anti-inflammatory potential was demonstrated through effective inhibition of 5-LOX enzyme, with compound 5e exhibiting particular potency (IC₅₀ = 0.951 ± 0.02 mg/mL) [6].

DFT-Experimental Correlation: DFT calculations provided insights into electronic properties and molecular stability that aligned with experimental bioactivity results, enabling rationalization of structure-activity relationships observed in biological testing [6].

Catalyst Design for Environmental Applications

Background and Rationale: Selective catalytic reduction (SCR) of NOx by NH₃ represents a promising method for nitrogen oxide removal, limited by low-temperature effectiveness and narrow operating window [8].

DFT-Guided Optimization: DFT calculations demonstrated that Fe-doped CoMn₂O₄ (CoFe₀.₁Mn₁.₉O₄) catalysts enhance catalytic activity through multiple mechanisms [8]:

- Enhanced NH₃ adsorption on catalyst surface (Eads = -1.29 eV → -1.42 eV)

- Reduced first step dehydrogenation reaction energy (Eα = 0.86 eV → 0.83 eV)

- Lowered energy barrier of NH₃-SCR (Eα = 1.11 eV → 0.86 eV)

Electronic structure analysis through electron difference density (EDD) and partial density of states (PDOS) confirmed improved adsorption characteristics [8].

Experimental Validation: CoMn₂O₄ and Fe-doped CoMn₂O₄ (CoFe₀.₀₂Mn₁.₉₈O₄) catalysts synthesized via sol-gel and impregnation techniques demonstrated significantly improved performance [8]:

- Efficient NOx conversion (87% at 250°C for doped catalyst)

- Improved N₂ selectivity (64%)

- Correlation with computational predictions

The combined DFT-experimental approach provided a method to improve denitrification efficiency of CoMn₂O₄ spinel catalysts, offering new avenues for catalyst development [8].

Essential Protocols for DFT-Experimental Integration

DFT Calculation Protocol for Catalytic Materials

System Setup:

- Employ periodic boundary conditions for solid-state systems

- Select appropriate functionals (PBE for structural properties, hybrid functionals for electronic properties)

- Include dispersion corrections (D3, TS, MBD) for noncovalent interactions [4]

- Use plane-wave basis sets with pseudopotentials or all-electron basis sets depending on system

Calculation Workflow:

- Geometry Optimization: Minimize total energy with respect to atomic positions and lattice parameters

- Electronic Structure Analysis: Calculate density of states, band structure, electron density difference

- Reaction Pathway Mapping: Identify transition states, calculate activation energies

- Property Prediction: Derive adsorption energies, reaction energies, electronic properties

Validation Metrics:

- Compare optimized geometries with experimental XRD structures

- Correlate calculated reaction barriers with catalytic performance

- Match calculated spectroscopic properties with experimental measurements

Experimental Validation Protocol

Synthesis Guidance:

- Use DFT-predicted stable structures and formation energies to guide synthesis parameters

- Apply computational screening to reduce experimental trial range

- Utilize charge distribution calculations to predict reaction sites

Characterization Techniques:

- Structural: XRD, EXAFS, TEM for comparison with optimized geometries

- Electronic: XPS, UV-Vis, EPR for comparison with density of states

- Performance: Electrochemical measurements, catalytic activity tests

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function in DFT-Experimental Research |

|---|---|

| CuO-ZnO nanocomposites | Enhanced electrochemical sensing platforms [7] |

| Fe-doped CoMn₂O₄ catalysts | Improved SCR denitrification systems [8] |

| Chromone-isoxazoline hybrids | Novel pharmaceutical agents with dual antibacterial/anti-inflammatory activity [6] |

| Graphene derivatives | CO₂ capture and storage materials [9] |

| Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) | Tunable porous materials for gas separation and storage [3] |

Advanced Applications and Emerging Frontiers

High-Pressure Material Science

DFT calculations have proven invaluable for high-pressure studies of organic crystalline materials, where pressure ranging from 0.1 to 20 GPa can induce polymorphic changes, phase transitions, and property modifications [4]. The diagram below illustrates the integrated computational-experimental approach for high-pressure studies:

Figure 2: High-Pressure DFT Study Workflow

DFT enables prediction of high-pressure polymorphs, analysis of anisotropic compression, and calculation of thermodynamic properties under conditions where direct experimental measurement proves challenging [4]. These capabilities make DFT particularly valuable for planetary science, high-energy materials, and pharmaceutical polymorphism studies [4].

Machine Learning-Enhanced DFT Protocols

Recent advances integrate machine learning with DFT to accelerate material discovery and improve accuracy. While not explicitly covered in the search results, this emerging frontier represents the natural evolution of DFT validation frameworks, potentially addressing current limitations in system size and timescale constraints [2].

The central role of DFT in modern quantum mechanics calculations is firmly established, with its position strengthened through rigorous experimental validation across diverse scientific domains. The integration of DFT predictions with experimental synthesis creates a powerful feedback loop that enhances both computational methods and material design strategies. As DFT continues to evolve through improved functionals, dispersion corrections, and integration with emerging computational approaches, its value as a predictive tool in scientific research and industrial development will further expand. The validated protocols and case studies presented herein provide a framework for researchers to effectively leverage DFT in accelerating material discovery and optimization across catalysis, pharmaceuticals, energy storage, and environmental applications.

Density functional theory (DFT) stands as a cornerstone computational method in physics, chemistry, and materials science for investigating the electronic structure and ground-state properties of many-body systems. [1] Its versatility and relatively low computational cost compared to traditional ab initio methods have made it immensely popular. However, the accuracy of DFT calculations is inherently limited by the approximations used for the exchange-correlation functional. [1] This application note details three significant challenges—delocalization error, the treatment of van der Waals forces, and static correlation error—within the critical context of validating DFT predictions with experimental synthesis research. We provide structured data, methodological protocols, and visual workflows to guide researchers in recognizing, mitigating, and controlling for these limitations in materials design and discovery.

Delocalization Error

Concept and Impact on Synthesis Prediction

Delocalization error, a manifestation of the self-interaction error, arises because approximate DFT functionals do not exactly cancel the electron's interaction with itself. This leads to an overly delocalized electron density and a failure to accurately describe systems where electron localization is crucial, such as transition states in chemical reactions, charge-transfer excitations, and defective crystals. [1] For experimental synthesis validation, this error can significantly impact the prediction of electronic properties like band gaps (which are systematically underestimated), [1] as well as the calculated stability and reactivity of proposed materials, potentially leading to the misguided synthesis of metastable or non-viable compounds.

Quantitative Comparison of Mitigation Strategies

Table 1: Approaches for Mitigating Delocalization Error

| Method | Theoretical Basis | Advantages | Limitations | Representative Functionals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Hybrids | Incorporates a fraction of exact Hartree-Fock exchange into the semilocal functional. | Reduces delocalization; improves band gaps and reaction barrier heights. | Increases computational cost; optimal fraction may be system-dependent. | PBE0, B3LYP, HSE06 |

| Range-Separated Hybrids | Separates the electron-electron interaction into short- and long-range parts, applying exact exchange predominantly in the long range. | Offers a more physically motivated treatment; excellent for charge-transfer states. | Parameter (ω) tuning may be necessary for specific material classes. | LC-ωPBE, CAM-B3LYP, HSE |

| DFT+U | Adds an on-site Coulomb repulsion term to correct for localization in specific electron orbitals (e.g., d or f electrons). | Simple, computationally cheap correction for strongly correlated systems. | The U parameter is empirical and requires derivation from experiment or higher-level theory. | PBE+U, LDA+U |

| Meta-GGAs | Uses the kinetic energy density in addition to the density and its gradient, providing more information about electron localization. | Improved accuracy for atomization energies and geometries without the cost of hybrids. | Limited impact on fundamental band gap correction. | SCAN, M06-L, TPSS |

Experimental Protocol: Validating Band Gap Predictions

Objective: To experimentally validate the DFT-predicted electronic band gap of a newly synthesized semiconductor, thereby assessing the severity of delocalization error in the chosen functional.

Materials & Reagents:

- Synthesized Crystal: Phase-pure powder or single crystal of the target material.

- Reference Standard: A well-characterized semiconductor with a known band gap (e.g., Silicon, GaAs).

- DFT Computational Setup: High-performance computing cluster; standardized computational parameters (e.g., plane-wave cutoff, k-point grid).

Procedure:

- Computational Prediction: a. Geometry Optimization: Fully optimize the crystal structure using a standard semilocal functional (e.g., PBE). b. Band Structure Calculation: Perform single-point band structure calculations using the optimized geometry with both the semilocal functional and a hybrid functional (e.g., HSE06). c. Data Extraction: Extract the fundamental and optical band gaps from the calculated electronic density of states and band structure.

- Experimental Validation via UV-Vis-NIR Spectroscopy: a. Sample Preparation: For a direct band gap material, prepare a finely ground powder and pack it uniformly into a sample holder for diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS). For thin films or single crystals, use transmission geometry. b. Measurement: Acquire DRS data over a wavelength range that encompasses the expected absorption edge (e.g., 200 nm - 1500 nm). Convert reflectance data to the Kubelka-Munk function, F(R∞). c. Tauc Plot Analysis: Plot [F(R∞) * hν]^n versus hν, where n is 1/2 for indirect and 2 for direct band gaps. The band gap is determined by extrapolating the linear region of the plot to [F(R∞) * hν]^n = 0.

- Data Comparison & Analysis: a. Compare the experimental Tauc gap with the computationally predicted values. b. Quantify the delocalization error as the difference between the PBE-predicted gap and the experimental gap. c. Assess the improvement offered by the hybrid functional.

Diagram 1: Workflow for experimental validation of DFT-predicted band gaps to assess delocalization error.

Van der Waals Forces

Challenge in Non-Covalent Interactions

Van der Waals (vdW) forces are weak, attractive interactions arising from quantum fluctuations in electron density. Standard semilocal and hybrid DFT functionals are inherently local and cannot capture these long-range, non-local correlations. [1] This results in a poor description of systems dominated by vdW interactions, such as layered materials (e.g., graphite, MoS₂), molecular crystals, adsorption phenomena on surfaces, and biomolecule-ligand interactions in drug development. [1] An uncorrected DFT calculation may predict incorrect equilibrium geometries, binding energies, and interlayer spacings, leading to a fundamental misunderstanding of material stability and reactivity.

Protocols for vdW-Inclusive Calculations

Objective: To accurately compute the binding energy and equilibrium structure of a molecular adsorption complex or a layered material using vdW-corrected DFT.

Materials & Reagents:

- Crystal Structure File: CIF or POSCAR file of the system.

- vdW-Corrected DFT Code: Software with implemented vdW corrections (e.g., VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO).

- Reference Data: (If available) Experimental crystallographic data or high-level quantum chemistry (CCSD(T)) results for benchmark systems.

Procedure:

- System Setup: a. Construct the initial geometry, ensuring the vdW-affected fragments (e.g., adsorbate and surface, or two layers) are separated but within interaction range. b. Select an appropriate periodic DFT code and planewave basis set.

- Functional Selection & Calculation: a. Perform a geometry optimization using a standard GGA functional (e.g., PBE) without vdW corrections. Note the resulting inter-fragment distance and the calculated adsorption or cohesion energy. b. Repeat the geometry optimization and energy calculation using one of the following vdW-inclusive methods: i. Semi-empirical Methods (e.g., DFT-D3): Add an empirical dispersion correction term. This is computationally inexpensive and often very effective. ii. Non-Local van der Waals Functionals (e.g., vdW-DF2, rVV10): Use a functional designed to include non-local correlation. This is more ab initio but can be computationally more demanding.

- Result Analysis: a. Plot the energy versus inter-fragment distance (binding curve) for the different methods. b. Compare the predicted equilibrium separation and binding energy with the uncorrected PBE result and with available experimental data (e.g., from X-ray diffraction or thermal desorption spectroscopy). c. The improvement in binding energy and geometry is a direct measure of the success of the vdW correction.

Table 2: Common vdW Correction Methods for DFT

| Method Category | Examples | Key Feature | Computational Cost | Recommended for |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical (DFT-D) | DFT-D2, DFT-D3, DFT-D4 | Atom-pairwise additive correction with damping function. | Negligible increase | High-throughput screening of molecular crystals, layered materials. |

| Non-Local Functionals | vdW-DF, vdW-DF2, rVV10 | Includes non-local correlation via a double real-space integral. | Moderate increase (2-5x) | Physisorption on surfaces, layered materials with competing interactions. |

| Hybrid+vVdW | PBE0-D3, SCAN+rVV10 | Combines exact exchange for delocalization error with non-local vdW. | High | Systems requiring accurate treatment of both covalent and non-covalent bonds. |

Static Correlation

The Multi-Reference Problem

Static correlation error, also known as strong correlation, occurs in systems with (near-)degenerate electronic states, such as diradicals, transition metal complexes with open d-shells, and bond-breaking processes. [10] In these cases, the true electronic wavefunction requires a multi-reference description, meaning it is a superposition of several Slater determinants with similar weights. Standard Kohn-Sham DFT, which uses a single determinant as a reference, is inherently limited in its ability to describe such systems, leading to large errors in predicting reaction barriers, singlet-triplet energy gaps, and electronic properties of multiradicals. [10]

Enhanced DFT for Static Correlation

Recent research has focused on combining DFT with reduced density matrix theory (RDMFT) to create a universal generalization of DFT for static correlation. [10] This approach leverages a unitary decomposition of the two-electron cumulant, allowing for fractional orbital occupations and thereby capturing the multi-reference character of the system. A key advancement for large molecules is the renormalization of the trace of the two-electron identity matrix using Cauchy-Schwarz inequalities, which retains the favorable O(N³) computational scaling of DFT while significantly improving accuracy for statically correlated systems. [10] This method has been successfully applied to predict singlet-triplet gaps and equilibrium geometries in acenes, a class of materials where static correlation is prominent. [10]

Protocol for Singlet-Triplet Gap Calculation in Multiradicals

Objective: To accurately compute the singlet-triplet energy gap (ΔE_ST) of an organic diradical (e.g., a large acene) using methods that address static correlation.

Materials & Reagents:

- Molecular Structure: Optimized geometry of the molecule in its neutral state.

- Advanced Electronic Structure Code: Software capable of RDMFT [10] or high-level wavefunction methods (e.g., CASSCF, DMRG, NEVPT2).

Procedure:

- Geometry Optimization: a. Optimize the molecular geometry of the system using a robust functional (e.g., B3LYP) with a modest basis set. This provides a consistent structure for subsequent high-level single-point energy calculations.

- High-Level Single-Point Energy Calculations: a. Reference Method (if computationally feasible): Perform a Complete Active Space Self-Consistent Field (CASSCF) calculation followed by N-electron Valence Perturbation Theory (NEVPT2) to obtain a benchmark ΔEST. This defines the target level of accuracy. b. Standard DFT Calculation: Calculate the total energy for the singlet and triplet states using a common functional (e.g., B3LYP, UBP86). Use a broken-symmetry approach for the singlet state. ΔEST(DFT) = E(S) - E(T). c. Enhanced RDMFT Calculation: [10] Perform a calculation using the renormalized generalized DFT/RDMFT method. This involves solving for the 1- and 2-electron reduced density matrices with constraints to enforce N-representability, typically via semidefinite programming. [10] Extract ΔE_ST(RDMFT).

- Validation and Analysis: a. Compare ΔE_ST from standard DFT and enhanced RDMFT against the benchmark NEVPT2 value or available experimental data from magnetic susceptibility or electron spin resonance (ESR) spectroscopy. b. The deviation of standard DFT from the benchmark quantifies the static correlation error, while the performance of RDMFT demonstrates the efficacy of the correction.

Diagram 2: Protocol for calculating singlet-triplet energy gaps in diradicals, comparing standard and enhanced methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational and Experimental "Reagents" for DFT Validation

| Item / Resource | Type | Function / Purpose | Example Sources / Kits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Packages | Computational | Provides the engine for performing DFT and post-DFT calculations with various functionals and solvers. | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, Gaussian, ORCA, CP2K |

| Materials Databases | Data | Source of crystal structures for calculation input and experimental data for validation (e.g., band gaps, lattice parameters). | Materials Project, ICSD, COD, NOMAD |

| Hybrid Functionals | Computational Algorithm | Mitigates delocalization error by incorporating exact exchange. Critical for accurate band gaps and defect levels. | HSE06, PBE0, B3LYP (empirical) |

| Dispersion Corrections | Computational Algorithm | Adds van der Waals interactions to DFT, essential for layered materials, molecular crystals, and adsorption. | DFT-D3, DFT-D4, vdW-DF2, rVV10 |

| Specialized Codes (RDMFT) | Computational Algorithm | Addresses static correlation error via reduced density matrix theory, enabling treatment of multiradicals and strong correlation. | Custom code (as in ref. [10]), NOCEDAR |

| UV-Vis-NIR Spectrometer | Experimental Equipment | Measures the optical absorption of a material, used to derive the experimental band gap via Tauc plot analysis. | Agilent Cary Series, PerkinElmer Lambda |

| X-ray Diffractometer | Experimental Equipment | Determines the crystal structure and lattice parameters, providing ground-truth geometry for validating DFT-optimized structures. | Bruker D8, Rigaku SmartLab |

The Critical Need for Experimental Validation in Materials and Molecular Science

Density Functional Theory (DFT) has become an indispensable computational tool for predicting the properties of materials and molecules, driving innovations in drug development, catalysis, and energy storage [11]. However, even as methodologies advance, the inherent limitations of DFT necessitate rigorous experimental validation to ensure predictions are reliable and translatable to real-world applications. This application note establishes that while DFT provides a powerful starting point, experimental synthesis and characterization form the critical bridge between theoretical prediction and scientific discovery, creating a cycle of continuous improvement for computational methods.

Quantifying Discrepancies: The Accuracy Gap Between DFT and Experiment

While DFT is a cornerstone of computational materials science, systematic comparisons with experimental data reveal a measurable accuracy gap. The table below summarizes key discrepancies reported in recent studies.

Table 1: Documented Discrepancies Between DFT Calculations and Experimental Data

| Property Measured | System | Reported Discrepancy | Source of Experimental Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formation Energy | Inorganic Crystalline Materials | MAE*: 0.076 - 0.133 eV/atom | Experimental formation energies at room temperature [12] |

| Crystal Structure | Organic Molecular Crystals | Avg. RMS Cartesian Displacement: 0.095 Å (0.084 Å for ordered structures) | High-quality experimental crystal structures from Acta Cryst. Section E [13] |

| Enthalpy of Formation | Binary & Ternary Alloys (Al-Ni-Pd, Al-Ni-Ti) | Significant errors in phase stability predictions, requiring ML-based correction | Experimental thermochemical data and phase diagrams [14] |

MAE: Mean Absolute Error; *RMS: Root Mean Square

These discrepancies arise from several fundamental sources. DFT calculations are typically performed at 0 Kelvin, while experimental measurements are conducted at room temperature, leading to differences in reported formation energies [12]. Furthermore, the choice of exchange-correlation functionals introduces systematic errors, and long-range dispersive interactions (van der Waals forces), critical in molecular crystals, are not naturally incorporated into standard DFT and require specialized corrections [13] [11].

Experimental Validation Workflow and Protocols

A robust, multi-stage workflow is essential for the effective experimental validation of computational predictions. The following protocol and diagram outline this iterative process.

Phase 1: Synthesis Planning and Target Definition

- Input from DFT: Use the DFT-predicted crystal structure, formation energy, and target properties (e.g., band gap, adsorption energy) to define the synthesis target [15].

- Defining Validation Metrics: Prior to synthesis, establish quantitative metrics for success. For structural validation, this includes target values for lattice parameters and a threshold for the root-mean-square (RMS) Cartesian displacement between the experimental and DFT-optimized atomic coordinates, with a typical benchmark for high-quality agreement being below 0.25 Å [13].

Phase 2: Material Synthesis

- Protocol for Solid-State Materials Synthesis: For inorganic crystalline materials like perovskites or alloys, use standard solid-state reactions. Weigh out high-purity precursor powders according to the stoichiometry of the DFT-predicted compound (e.g., Cs₂AgBiBr₆ for double perovskites) [15]. Mix thoroughly using a ball mill for 1-2 hours. React the mixture in a furnace using a controlled atmosphere (e.g., argon for air-sensitive materials) and a optimized temperature profile (e.g., 500-800°C for 10-20 hours) with intermediate grinding to ensure homogeneity.

- Protocol for Organic Molecular Crystals: For organic systems, purify the starting compound via recrystallization. Grow single crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction via slow evaporation from a saturated solution or slow cooling from a melt.

Phase 3: Structural Characterization and Validation Protocol

- Technique: Single-Crystal X-ray Diffraction (XRD) is the gold standard for determining atomic-level crystal structure [13].

- Procedure: Mount a high-quality single crystal (typically 0.1-0.3 mm) on a diffractometer. Collect a full dataset of diffraction intensities at a specified temperature (e.g., 100 K for reduced thermal disorder). Solve and refine the crystal structure using standard software (e.g., SHELXT, OLEX2).

- Validation Analysis: Compare the experimentally determined structure with the DFT-predicted one.

- Energy Minimization: Perform a full energy minimization (including unit-cell parameters) of the experimental crystal structure using a dispersion-corrected DFT (d-DFT) method to enable a direct comparison [13].

- Quantitative Comparison: Calculate the RMS Cartesian displacement for all non-hydrogen atoms between the experimental and DFT-minimized structures. An RMSD above 0.25 Å indicates a potentially incorrect experimental structure, interesting thermal effects, or a significant failure of the DFT functional [13].

Phase 4: Functional Property Validation

- Adsorption Energy Validation (e.g., for CO₂ capture): For materials like functionalized graphene, synthesize the material and conduct gas adsorption experiments using a volumetric or gravimetric analyzer. Measure the CO₂ uptake isotherm at relevant temperatures and pressures. Compare the experimental isotherm with the one predicted from DFT-calculated interaction energies to validate the model [9].

- Electrochemical Property Validation (e.g., for battery materials): For predicted cathode materials, fabricate electrodes and assemble coin cells in an argon-filled glovebox. Perform galvanostatic cycling to measure the average voltage and compare it with the DFT or machine learning-predicted voltage [16].

Phase 5: Data Integration and Model Refinement

This phase closes the validation loop. Document any discrepancies between experimental data and DFT predictions. Use these discrepancies to refine the computational model, for instance, by adjusting the exchange-correlation functional, incorporating more accurate dispersion corrections, or by using the experimental data to train a machine learning model that can correct systematic DFT errors [12] [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details essential materials and computational tools used in the validation process.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for DFT Validation

| Item Name | Function/Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| VASP (Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package) | A widely used software for performing DFT calculations with plane-wave basis sets and pseudopotentials. | Used for energy minimization of experimental crystal structures and property prediction [13] [17]. |

| Dispersion-Corrected DFT (d-DFT) | A class of DFT methods incorporating empirical or semi-empirical corrections for long-range van der Waals interactions. | Critical for accurately modeling the structure and stability of organic molecular crystals [13]. |

| High-Purity Precursor Salts/Oxides | Metal salts or oxides of ≥99.9% purity are used as starting materials for solid-state synthesis. | Essential for synthesizing predicted inorganic compounds (e.g., perovskites, alloys) with minimal impurity phases [15]. |

| Single-Crystal X-ray Diffractometer | Instrument for determining the precise 3D atomic arrangement within a single crystal. | The primary tool for experimental structural validation and comparison with DFT-optimized geometries [13]. |

| Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) | Models trained on DFT data to achieve near-DFT accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost. | Used for accelerated screening and property prediction while relying on DFT for training data [18]. |

Advanced Integrative Approaches: Leveraging Machine Learning

Machine learning (ML) is now a powerful bridge between DFT and experiment. ML models can be trained to predict and correct the discrepancy between DFT-calculated and experimentally measured properties.

- Protocol for ML-Based Enthalpy Correction: As demonstrated for alloy formation enthalpies, a neural network model can be developed to predict the error in DFT calculations [14].

- Data Curation: Compile a dataset of reliable experimental formation enthalpies for binary and ternary compounds.

- Feature Engineering: For each compound, calculate a set of input features including elemental concentrations, weighted atomic numbers, and interaction terms [14].

- Model Training & Application: Train a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) regressor to predict the difference between DFT and experimental enthalpies. This trained model can then be applied to correct new DFT predictions, significantly improving their accuracy and reliability for phase stability assessment [14].

This hybrid DFT-ML approach, grounded in experimental data, represents the forefront of predictive materials science.

Accurately predicting the structure and properties of organic molecular crystals is fundamental to advancements in pharmaceutical development, energetic materials, and functional materials design. Traditional computational methods face significant challenges in this domain. Density Functional Theory (DFT), while powerful, suffers from a well-documented limitation: it does not inherently account for long-range dispersive interactions (van der Waals forces), which are particularly important in molecular crystals [19]. The absence of these interactions in standard DFT calculations can lead to unrealistic structures and inaccurate energetics, severely limiting its predictive value for organic crystals.

Dispersion-corrected DFT (d-DFT) methods have emerged to bridge this accuracy gap. By incorporating a correction for dispersion forces, d-DFT achieves an optimal balance between computational cost and quantum-mechanical accuracy, enabling reliable predictions of crystal structures, mechanical properties, and reaction pathways [19] [20]. This approach transforms computational models from qualitative tools into quantitative partners for experimental synthesis research, allowing researchers to validate predictions, interpret ambiguous data, and explore structural features that are difficult to observe experimentally [19]. The validation of a d-DFT method demonstrates that its information content and reliability are on par with medium-quality experimental data, making it an indispensable component of the modern research toolkit [19].

Computational Protocols and Best Practices

Choosing a Functional and Correction Scheme

The selection of an appropriate exchange-correlation functional and dispersion correction is the most critical step in ensuring accurate simulations. Adherence to modern best-practice protocols is essential to avoid outdated methodologies [21].

- Semi-local Functionals with Explicit Corrections: Methods like Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) or Perdew-Wang-91 (PW91) coupled with an empirical dispersion correction (e.g., D3, DCP) were foundational. These are robust and computationally efficient for large systems [19] [21].

- Non-local van der Waals Functionals: For superior accuracy, vdW-DF-OptB88 is highly recommended and widely used in materials databases like JARVIS-DFT for geometry optimization of both van der Waals and non-van der Waals solids [22]. Other variants like vdW-DF-OptB86b also provide excellent performance.

- Avoiding Outdated Methods: Outdated functional/basis set combinations like B3LYP/6-31G* are known to suffer from severe inherent errors, such as missing London dispersion effects and strong basis set superposition error (BSSE). Modern, more accurate, and robust alternatives should be used instead [21].

Table 1: Recommended Density Functionals for Organic Crystals

| Functional Type | Specific Example | Key Features and Applications |

|---|---|---|

| vdW Density Functional | vdW-DF-OptB88 | Provides accurate lattice parameters; used for primary geometry optimization in high-throughput databases [22]. |

| Meta-GGA | TBmBJ (Tran-Blaha modified Becke-Johnson) | Improves bandgap predictions; used on top of optimized structures for electronic property analysis [22]. |

| Hybrid Functional | HSE06, PBE0 | Offers higher accuracy for electronic properties but at greater computational cost; used for selective validation [22]. |

Workflow for Geometry Optimization and Validation

A structured workflow is vital for obtaining physically meaningful and converged results. The following protocol, synthesizing information from multiple sources, ensures robustness:

System Preparation and Convergence Tests:

- Obtain initial crystal structures from reliable databases (e.g., ICSD, COD, Materials Project) [22].

- Perform convergence tests for the plane-wave cut-off energy and k-point mesh before full geometry optimization. A common protocol is to converge until the energy difference between successive iterations is less than a tolerance (e.g., 1 meV/atom) for several successive steps, starting from a cut-off of 500 eV and increasing by 50 eV, and a k-point length of 10 Å [22].

Multi-Stage Geometry Optimization:

- Step 1 - Fixed Cell Optimization: Initially, optimize atomic positions with the experimental unit cell fixed. This helps manage strong initial forces from experimental uncertainties [19].

- Step 2 - Full Cell Relaxation: Perform a second optimization where both atomic positions and unit cell parameters are allowed to relax. Convergence criteria should be stringent: maximal forces < 0.001 eV/Å and energy tolerance < 10⁻⁷ eV [19] [22].

- For particularly sensitive or complex structures, a three-step procedure (holding cell, then molecular positions, then full relaxation) may be necessary to avoid local minima [19].

Validation and Analysis:

- Calculate the root-mean-square (r.m.s.) Cartesian displacement between the experimental and minimized crystal structures. An average r.m.s. displacement of ~0.084-0.095 Å for ordered structures indicates excellent agreement with high-quality experimental data [19].

- Displacements exceeding 0.25 Å often signal an incorrect experimental structure, unmodeled disorder, or significant temperature effects worthy of further investigation [19].

Diagram 1: d-DFT Geometry Optimization and Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Computational Reagents

Table 2: Key Software and Pseudopotentials for d-DFT Calculations

| Tool / Reagent | Category | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| VASP [19] [22] | Software Package | A widely used plane-wave DFT code; often integrated into workflows (e.g., via GRACE or JARVIS-Tools) for efficient energy minimization. |

| Projected Augmented Wave (PAW) Pseudopotentials [22] | Pseudopotential | Used in VASP to represent atomic cores; accurate and efficient for a wide range of elements. The JARVIS_VASP_PSP_DIR environment variable must be set. |

| GRACE [19] | Software Package | A program that implements an efficient minimization algorithm and adds a dispersion correction to pure DFT calculations from VASP. |

| JARVIS-Tools [22] | Software/Workflow | A Python library and set of workflows that automate JARVIS-DFT protocols, including k-point convergence and property calculation. |

| OptB88vdW & TBmBJ [22] | Computational Parameter | The recommended functional combination for geometry optimization and subsequent electronic property analysis, respectively. |

Validation Against Experimental Data: A Case Study

The true value of any computational method lies in its agreement with empirical evidence. A landmark validation study analyzed 241 experimental organic crystal structures from Acta Cryst. Section E [19]. The structures were energy-minimized using a d-DFT method (VASP with a dispersion correction), allowing both atomic positions and unit-cell parameters to relax.

The quantitative results firmly established the method's accuracy:

- The average r.m.s. Cartesian displacement (excluding H atoms) for all 241 structures was 0.095 Å.

- For the 225 ordered structures, the average displacement was even lower at 0.084 Å [19].

This exceptional agreement confirms that d-DFT can reproduce experimental crystal structures with high fidelity. The r.m.s. displacement serves as a powerful "correctness indicator." Values above 0.25 Å were found to be a strong indicator of potential issues with the experimental structure or the presence of interesting physical phenomena, such as incorrectly modelled disorder or large temperature effects [19]. This makes d-DFT an invaluable tool for crystallographic validation and for enhancing the information content of purely experimental data.

Table 3: Quantitative Validation of d-DFT against Experimental Crystal Structures

| Validation Metric | Result | Interpretation and Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Average RMSD (All 241 Structures) | 0.095 Å | Demonstrates high overall accuracy in reproducing experimental geometries. |

| Average RMSD (225 Ordered Structures) | 0.084 Å | Highlights the method's precision for well-defined systems. |

| RMSD Threshold for "Warning" | > 0.25 Å | Suggests a potentially incorrect structure or reveals novel features like large disorder or temperature effects. |

Advanced Applications in Materials Science

Neural Network Potentials Trained on d-DFT

The high computational cost of d-DFT can be a bottleneck for large-scale molecular dynamics simulations. A cutting-edge solution is the development of Neural Network Potentials (NNPs), such as the EMFF-2025 model for C, H, N, O-based high-energy materials (HEMs) [20]. These models are trained on d-DFT data and can achieve DFT-level accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost, enabling the prediction of structure, mechanical properties, and decomposition characteristics for complex materials [20].

The strategy involves:

- Using a pre-trained model (e.g., DP-CHNO-2024) as a base.

- Employing transfer learning with minimal additional DFT data to create a general-purpose potential (e.g., EMFF-2025) [20].

- This NNP can then predict energies and forces with mean absolute errors (MAE) within ~0.1 eV/atom and ~2 eV/Å, respectively, allowing for accurate and efficient exploration of chemical spaces and reaction mechanisms [20].

Guiding Organic Synthesis and Spectroscopy

d-DFT is also instrumental in supporting synthetic chemistry, as demonstrated in the synthesis of fatty amides from extra-virgin olive oil [23] and 2-amino-4H-chromenes using a nanocatalyst [24]. In these studies, d-DFT calculations (e.g., at the B3LYP/6-311+G(d,p) level) are used to:

- Interpret experimental spectra: Calculating vibrational frequencies (FT-IR), and NMR chemical shifts ((^1)H and (^{13})C) for direct comparison with measured data [23] [24].

- Analyze electronic structure: Determining HOMO-LUMO energies provides insights into molecular reactivity and charge transfer processes [24].

- Understand molecular stability: Techniques like Natural Bond Orbital (NBO) analysis and molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) surfaces reveal intramolecular interactions and reactive sites [24].

Diagram 2: Advanced d-DFT Applications and Research Outcomes

Dispersion-corrected DFT has fundamentally overcome the limitations of traditional DFT for modeling organic molecular crystals. By integrating validated computational protocols—using modern functionals like vdW-DF-OptB88, following rigorous convergence and optimization workflows, and leveraging quantitative metrics like RMSD for validation—researchers can achieve predictive accuracy on par with experimental data. This capability positions d-DFT as a cornerstone of modern computational materials science and pharmaceutical development.

The method's utility extends from foundational crystal structure validation to guiding the synthesis of new organic compounds and training next-generation machine learning potentials. As these protocols become more automated and integrated into high-throughput workflows, d-DFT will continue to be an indispensable tool for bridging the gap between theoretical prediction and experimental synthesis, accelerating the rational design of novel materials.

The accuracy of Density Functional Theory (DFT) predictions is paramount in materials science and drug development. The integration of high-quality experimental data provides a critical benchmark for assessing the predictive power of computational models. This protocol outlines a systematic approach for validating DFT-based predictions against curated experimental datasets, focusing on formation energies and band gaps—key parameters for predicting material stability and electronic properties. The validation framework leverages statistical analysis to quantify the performance of different DFT functionals, providing researchers with a robust methodology for verifying computational models.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Database Construction and Curation

The foundational step for systematic validation involves constructing a high-quality database of inorganic materials with diverse structures and compositions. The following protocol details this process:

- Source Material Selection: Query initial crystal structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD, v2020). For materials with multiple entries (duplicate entries or polymorphs), apply a filtering process based on the lowest energy per atom according to Materials Project (GGA/GGA+U) data. For formulas without a Materials Project ID, select the ICSD entry with the fewest atoms in the unit cell [25].

- Computational Settings: Perform geometry optimizations using the PBEsol functional, which provides accurate estimation of lattice constants of solids. Use the "light" settings for numerically atom-centered orbital (NAO) basis sets in the FHI-aims code, offering an optimal balance between accuracy and computational efficiency. Employ a convergence criterion of 10⁻³ eV/Å for forces. For potentially magnetic structures (those labeled as magnetic in Materials Project or containing elements like Fe, Ni, Co), perform spin-polarized calculations [25].

- Hybrid Functional Calculations: Using the PBEsol-optimized structures, execute HSE06 energy evaluations and electronic structure calculations to obtain more accurate electronic properties. This step is computationally demanding but essential for improved accuracy, particularly for systems with localized electronic states like transition-metal oxides [25].

Validation Methodology

Once the database is established, implement this validation protocol to benchmark computational methods:

- Property Calculation: Compute key properties including formation energies and band gaps using both PBEsol and HSE06 functionals. Calculate formation energies using bulk phases as references for elements, with gaseous O₂ as the reference for oxygen [25].

- Experimental Benchmarking: Curate experimental data for binary systems from established literature sources. Identify materials common to both the computational dataset and experimental collections using Materials Project IDs for direct comparison [25].

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate Mean Absolute Deviation (MAD) for formation energies and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for band gaps between computational methods and experimental data. For band gaps, specifically compare the performance of PBEsol (GGA) and HSE06 (hybrid functional) methods [25].

- Thermodynamic Stability Assessment: Construct convex hull phase diagrams (CPDs) for representative chemical systems using both PBEsol and HSE06 functionals. Identify critical decomposition reactions and associated decomposition energy (ΔHd) as quantitative metrics of phase stability [25].

Quantitative Validation Data

The table below summarizes key quantitative metrics from a validation study of 7,024 inorganic materials, comparing PBEsol (GGA) and HSE06 (hybrid functional) methods:

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of DFT Functional Performance

| Validation Metric | PBEsol (GGA) | HSE06 (Hybrid) | Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formation Energy MAD | 0.15 eV/atom (vs. HSE06) | Reference value | Significant discrepancy in stability predictions |

| Band Gap MAD | 0.77 eV (vs. HSE06) | Reference value | Substantial systematic difference |

| Band Gap MAE | 1.35 eV (experimental) | 0.62 eV (experimental) | >50% improvement with HSE06 |

| Metallic vs. Insulating | 342 materials misclassified as metallic | Corrected band gap ≥0.5 eV | Improved electronic property prediction |

| Convex Hull Discrepancies | Distinct CPDs with different stable phases | Different CPDs with unique stable phases | Impact on predicted thermodynamic stability |

Visualization of Workflows

DFT Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete computational and validation workflow for benchmarking DFT predictions:

Validation Methodology

This diagram details the specific processes for validating computational results against experimental data:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| FHI-aims | All-electron DFT code for accurate electronic structure calculations | Supports NAO basis sets; compatible with hybrid functionals like HSE06 [25] |

| ICSD Database | Source of experimental crystal structures for initial coordinates and validation | Version 2020; provides curated inorganic crystal structures [25] |

| Materials Project API | Access to computed materials data for filtering and comparison | Contains GGA/GGA+U calculation data for structure selection [25] |

| HSE06 Functional | Hybrid functional for improved electronic property prediction | More accurate than GGA for band gaps; computationally intensive [25] |

| PBEsol Functional | GGA functional for geometry optimization | Accurate for lattice constants; efficient for initial structure optimization [25] |

| Taskblaster Framework | Workflow automation for high-throughput calculations | Manages multiple computational tasks in database construction [25] |

| spglib | Symmetry analysis tool for space group determination | Used with tolerance of 10⁻⁵ Å for accurate symmetry identification [25] |

From Simulation to Synthesis: Methodologies and Real-World Applications

Integrating DFT with Hydrothermal Synthesis and Electrode Modification

The integration of Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations with hydrothermal synthesis and electrode modification represents a paradigm shift in the rational design of advanced functional materials. This synergistic approach enables researchers to move beyond traditional trial-and-error methods, allowing for predictive material design with tailored properties for specific applications in sensing, catalysis, and energy storage. By employing DFT calculations to screen material properties and predict performance at the atomic level, researchers can guide subsequent experimental synthesis and device fabrication, significantly accelerating development cycles and enhancing fundamental understanding of structure-property relationships.

The core strength of this integrated methodology lies in creating a closed validation loop between theoretical predictions and experimental verification. Computational models suggest promising material compositions and structures, which are then synthesized via controlled hydrothermal methods and fabricated into functional electrodes. The resulting experimental performance data feedback to refine the computational models, leading to progressively more accurate predictions in an iterative design process. This protocol details the complete workflow, from initial DFT analysis through material synthesis to electrode modification and validation, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for developing high-performance materials systems.

Computational Foundation: DFT for Predictive Material Design

Fundamental DFT Calculations for Material Screening

DFT calculations provide critical insights into electronic structure, stability, and adsorption characteristics that govern material performance. For electrode modification applications, several key properties must be computed:

Band Structure and Density of States (DOS): These calculations reveal the electronic configuration, band gap values, and orbital contributions that influence electrical conductivity and catalytic activity. For instance, DFT analysis of Ni and Zn-doped CoS systems showed a systematic reduction in band gap from 1.41 eV (pristine CoS) to 1.12 eV (co-doped system), explaining enhanced charge transport properties [26]. Projected DOS (PDOS) further elucidates contributions from specific atomic orbitals, such as the hybridized Co(3d), Ni(3d), and S(3p) states dominating band edges in doped CoS systems [26].

Adsorption Energy (Eads): This parameter quantifies the strength of interaction between target molecules and catalyst surfaces. In Fe-doped CoMn₂O₄ catalysts for NH₃-SCR applications, DFT revealed enhanced NH₃ adsorption from -1.29 eV (undoped) to -1.42 eV (Fe-doped), indicating stronger reactant binding [8]. Similar calculations apply to dopamine detection systems, where adsorption energies on different crystal facets determine sensor sensitivity [7].

Reaction Energy Barriers (Eα): DFT can map reaction pathways and identify rate-limiting steps by calculating energy barriers. For CuO-ZnO systems, the reaction energy barrier for dopamine oxidation was computed as 0.54 eV, indicating favorable reaction kinetics [7]. Similarly, Fe doping in CoMn₂O₄ reduced the energy barrier for NH₃ dehydrogenation from 0.86 eV to 0.83 eV [8].

Table 1: Key DFT Parameters for Material Screening and Their Experimental Correlations

| DFT Parameter | Computational Description | Experimental Correlation | Impact on Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Band Gap (Eg) | Energy difference between valence and conduction bands | UV-Vis spectroscopy measurements | Lower Eg enhances visible light absorption and electrical conductivity |

| Adsorption Energy (Eads) | Energy released during molecule-surface interaction | Catalytic activity measurements, sensing response | Optimal Eads balances binding strength and desorption for catalytic turnover |

| d-Band Center | Average energy of d-states relative to Fermi level | XPS valence band analysis | Closer d-band center to Fermi level typically enhances reactivity |

| Reaction Energy Barrier (Eα) | Energy difference between reactants and transition state | Reaction kinetics from electrochemical measurements | Lower barriers enable faster reaction rates and improved sensitivity |

Advanced Computational Protocols

For accurate DFT modeling of electrochemical systems, several methodological considerations are essential:

Solvation Models: Implicit solvation models such as SMD (Solvation Model based on Density) must be incorporated to account for electrolyte effects [27]. Explicit water molecules can be added for specific adsorption studies.

Exchange-Correlation Functionals: Selection of appropriate functionals is critical. Hybrid functionals like HSE06 provide more accurate band gaps compared to standard GGA functionals [26]. The M06-2X functional has proven reliable for predicting reaction energies of organic transformations [27].

Electrochemical Modeling: The computational hydrogen electrode (CHE) approach allows modeling of potential-dependent electrochemical reactions. The scheme of squares framework effectively diagrams coupled electron-proton transfer pathways [27].

Calibration to Experimental Data: To address systematic DFT errors, calibration of calculated redox potentials against experimental cyclic voltammetry data is recommended. This improves predictive accuracy for new molecular systems [27].

Experimental Realization: Hydrothermal Synthesis

Hydrothermal Synthesis Principles and Setup

Hydrothermal synthesis occurs in a closed reaction vessel (autoclave) where elevated temperatures and pressures facilitate crystal growth under controlled conditions. This method offers distinct advantages for nanomaterial synthesis, including high product purity, controlled crystallinity, and the ability to regulate ultimate nanostructure dimensions and configuration within a minimally polluted closed system [28]. The process is particularly valuable for creating well-defined morphologies and heterostructures that are challenging to achieve through other synthetic routes.

Key parameters controlling hydrothermal synthesis outcomes include:

Temperature: Typically ranges from 90-200°C, influencing reaction kinetics and crystallization rates. For imogolite nanotube synthesis, optimal temperature ranges between 90-100°C, with higher temperatures favoring byproduct formation [29].

Reaction Duration: Varies from 5-48 hours, depending on material system and desired crystallinity [28]. Imogolite formation requires several days at 90°C for maximum yield [29].

pH Conditions: Critical for controlling nucleation and growth processes; generally maintained in neutral to alkaline ranges (pH 7-13) for metal oxide systems [28]. For ZnO nanostructures, pH variation from 7 to 13 produces different morphologies including nanorods, spheroidal discs, and nanoflowers [28].

Precursor Concentration and Solvent Composition: Determine final composition, morphology, and particle size. Mixed solvent systems (e.g., PEG-400/water) facilitate control over nanostructure formation [7].

Figure 1: Hydrothermal synthesis workflow

Protocol: Hydrothermal Synthesis of CuO-ZnO Nanocomposites

This protocol details the synthesis of CuO-ZnO nanoflowers for electrochemical sensing applications, adapted from recent research [7]:

Materials:

- Zinc chloride (ZnCl₂, ≥98%)

- Copper chloride (CuCl₂, ≥99%)

- Sodium hydroxide (NaOH, ≥97%)

- PEG-400

- Deionized water

Procedure:

- Precursor Solution Preparation: Dissolve 0.2169 g ZnCl₂ and 0.321 g NaOH in 40 mL of PEG-400/water solution (1:1 v/v ratio).

- Dopant Addition: Add CuCl₂ (1-7% by weight relative to total salt mixture) while stirring continuously.

- Homogenization: Stir the mixture for 60 minutes at room temperature to ensure complete homogenization.

- Hydrothermal Reaction: Transfer the solution to a Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave, seal tightly, and maintain at 120°C for 12 hours.

- Cooling and Collection: Allow the autoclave to cool naturally to room temperature. Collect the resulting precipitate by centrifugation at 8000 rpm for 10 minutes.

- Washing: Wash the product sequentially with deionized water and ethanol 3-4 times to remove impurities.

- Drying: Dry the final product at 60°C for 12 hours in a vacuum oven.

- Annealing: For enhanced crystallinity, anneal the powder at 300°C for 2 hours in a muffle furnace.

Characterization:

- Structural: XRD analysis confirms the formation of wurtzite ZnO and tenorite CuO phases.

- Morphological: FESEM and TEM reveal nanoflower structures composed of interwoven nanorods (length: 180-420 nm, width: 80-120 nm) [7].

- Compositional: EDX spectroscopy verifies elemental composition and successful doping.

Electrode Modification and Device Fabrication

Electrode Modification Techniques

Electrode modification transforms synthesized nanomaterials into functional sensing devices. Several approaches can be employed:

Drop-Casting: The simplest method involving direct application of material dispersion onto the electrode surface. For CuO-ZnO modified electrodes, 5 μL of ink (1 mg material in 1 mL ethanol) is drop-cast onto a polished glassy carbon electrode (GCE) and dried at room temperature [7].

Electrophoretic Deposition: Provides more uniform films through application of an electric field to drive material deposition.

In-situ Growth: Direct hydrothermal growth of nanostructures on electrode substrates, ensuring strong adhesion and enhanced charge transfer.

Critical considerations for effective electrode modification include:

- Material Dispersion: Complete exfoliation and homogeneous suspension in suitable solvents

- Surface Pretreatment: Electrode polishing (typically with 0.05 μm alumina slurry) and cleaning to ensure reproducible surfaces

- Film Thickness Control: Optimizing material loading to balance active sites and mass transport limitations

- Stabilization: Use of Nafion or chitosan binders to improve film stability without blocking active sites

Protocol: Fabrication of CuO-ZnO Modified Dopamine Sensor

This protocol details the fabrication and evaluation of an electrochemical dopamine sensor based on hydrothermally synthesized CuO-ZnO nanocomposites [7]:

Materials:

- Glassy carbon electrode (GCE, 3 mm diameter)

- Alumina polishing slurry (0.05 μm)

- CuO-ZnO nanocomposite powder

- Ethanol

- Phosphate buffer saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- Dopamine hydrochloride

Electrode Modification Procedure:

- GCE Pretreatment: Polish the GCE surface with 0.05 μm alumina slurry on a microcloth to create a mirror finish.

- Cleaning: Sonicate the polished electrode sequentially in ethanol and deionized water for 2 minutes each to remove residual alumina particles.

- Ink Preparation: Disperse 1 mg of CuO-ZnO nanocomposite powder in 1 mL ethanol and sonicate for 30 minutes to form a homogeneous suspension.

- Modification: Drop-cast 5 μL of the suspension onto the clean GCE surface and allow to dry at room temperature.

- Stabilization: Immerse the modified electrode in PBS (pH 7.4) and perform cyclic voltammetry scanning between -0.2 to 0.6 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) for 20 cycles to stabilize the electrode interface.

Electrochemical Characterization:

- Performance Evaluation: Using cyclic voltammetry or differential pulse voltammetry in PBS (pH 7.4) containing varying dopamine concentrations (0-100 μM).

- Detection Parameters: Measure oxidation peak current at approximately 0.25 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) for dopamine.

- Calibration: Plot peak current versus dopamine concentration to establish linear range and detection limit.

- Selectivity Assessment: Test against potential interferents including ascorbic acid, uric acid, and glucose.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of DFT-Guided Materials in Electrochemical Applications

| Material System | Application | Key DFT Prediction | Experimental Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CuO-ZnO Nanoflowers | Dopamine detection | Reduced reaction energy barrier (0.54 eV) | Low detection limit, high sensitivity and selectivity | [7] |

| Fe-doped CoMn₂O₄ | NH₃-SCR catalyst | Enhanced NH₃ adsorption (-1.42 eV), lower energy barriers | 87% NOx conversion at 250°C, improved N₂ selectivity | [8] |

| Ni,Zn-doped CoS | DSSC counter electrode | Band gap reduction, improved charge transport | Enhanced conductivity and catalytic activity vs Pt | [26] |

| ZnO-CeO₂ Heterojunction | Photocatalysis, HER | Band gap reduction (3.13→2.71 eV), suppressed charge recombination | 98% MB degradation, H₂ evolution: 3150 μmol·h⁻¹·g⁻¹ | [30] |

Validation and Correlation: Bridging Theory and Experiment

Analytical Techniques for Experimental Validation

Comprehensive characterization validates DFT predictions and establishes structure-property relationships:

Structural Analysis: XRD confirms crystal structure and phase composition. Rietveld refinement provides quantitative phase analysis. For CuO-ZnO systems, XRD confirms the coexistence of wurtzite ZnO and tenorite CuO phases without intermediate compounds [7].

Morphological Characterization: SEM and TEM reveal morphology, particle size, and distribution. HR-TEM with SAED patterns confirms crystallinity and interfacial relationships in heterostructures.

Surface Analysis: XPS determines elemental composition, chemical states, and doping effectiveness. For CuO-ZnO, XPS verifies the presence of Cu²⁺ and Zn²⁺ oxidation states [7].

Electrochemical Performance: Cyclic voltammetry, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, and amperometric i-t curves quantify sensing parameters including sensitivity, detection limit, linear range, and selectivity.

Case Study: Validating DFT Predictions for CuO-ZnO Dopamine Sensor

The integration of DFT predictions with experimental validation is exemplified in the development of CuO-ZnO dopamine sensors [7]:

DFT Predictions:

- Projected density of states (PDOS) analysis revealed strong hybridization between Cu 3d and O 2p orbitals near the Fermi level, enhancing electron transfer capabilities.

- The d-band center of Cu shifted closer to the Fermi level upon formation of heterojunctions, increasing surface reactivity.

- Reaction energy barrier for dopamine oxidation was calculated as 0.54 eV, indicating favorable reaction kinetics.

Experimental Validation:

- Cyclic voltammetry showed well-defined redox peaks for dopamine with peak separation of 0.12 V, indicating fast electron transfer kinetics.

- The sensor demonstrated a wide linear detection range (0.1-100 μM) with detection limit of 0.028 μM.

- Excellent selectivity was observed against common interferents (ascorbic acid, uric acid, glucose).

- DFT-predicted enhanced stability was confirmed with 95% signal retention after 4 weeks.

This case study demonstrates the powerful synergy between computational prediction and experimental validation, where DFT insights guided material design and experimental results confirmed computational accuracy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Integrated DFT-Experimental Studies

| Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Software | Gaussian 16, Quantum ESPRESSO, VASP | DFT calculations, electronic structure analysis | Selection depends on system size, accuracy requirements, and available resources |

| Metal Precursors | ZnCl₂, CuCl₂, AlCl₃, Ce(NO₃)₃ | Provide metal sources for nanostructure formation | Purity ≥99% recommended to minimize impurities in final product |

| Hydrothermal Equipment | Teflon-lined autoclaves, oven, centrifuge | Controlled crystal growth under elevated T&P | Autoclave volume typically 50-100 mL for lab-scale synthesis |

| Structure-Directing Agents | PEG-400, CTAB, PVP | Control morphology and prevent aggregation | Concentration critically influences nucleation and growth kinetics |

| Electrode Materials | Glassy carbon, FTO, ITO substrates | Support for modified electrodes | Surface pretreatment essential for reproducible modification |

| Electrochemical Reagents | Dopamine HCl, K₃[Fe(CN)₆], PBS buffer | Sensor performance evaluation and characterization | Fresh preparation recommended for unstable analytes like dopamine |

| Characterization Tools | XRD, SEM/TEM, XPS, FTIR | Material structure, morphology, and composition | Multiple techniques required for comprehensive characterization |

Troubleshooting and Optimization Guidelines

Successful integration of DFT with experimental synthesis requires attention to potential challenges:

DFT/Experimental Discrepancies: When computational predictions diverge from experimental results, consider limitations in DFT functionals, inadequate solvation models, or unaccounted surface defects in real materials. Calibration against known systems improves predictive accuracy [27].

Synthesis Reproducibility: Batch-to-batch variations in hydrothermal synthesis often stem from inconsistent heating rates, temperature gradients, or precursor hydrolysis rates. Strict control of reaction parameters and fresh precursor solutions enhance reproducibility.

Electrode Performance Issues: Poor sensitivity or stability may result from insufficient material-electrode contact, excessive film thickness, or binder effects. Optimize material loading and consider alternative deposition techniques.

Selectivity Challenges: Unexpected interference effects may arise from DFT-unaccounted surface interactions. Surface modification with selective membranes or functional groups can mitigate interference while maintaining sensitivity.

Figure 2: Integrated DFT-experimental workflow cycle

The accurate detection of the neurotransmitter dopamine (DA) is crucial for diagnosing and managing numerous neurological disorders. Electrochemical sensors based on metal oxides, particularly zinc oxide (ZnO), have gained prominence in this field due to their high sensitivity, cost-effectiveness, and rapid response times. However, the performance of pristine ZnO sensors is often limited by issues such as inadequate cycling stability and insufficient selectivity [7]. This case study, set within a broader thesis validating density functional theory (DFT) predictions with experimental research, explores the strategic enhancement of ZnO-based dopamine sensors through the incorporation of copper oxide (CuO). We demonstrate that the formation of CuO–ZnO heterojunctions and composites, guided by theoretical calculations, leads to a significant experimental improvement in sensor performance.

The synergy between computational and experimental materials science provides a powerful framework for rational sensor design. DFT calculations predict that CuO doping optimizes the electronic structure of ZnO, thereby enhancing its electrocatalytic activity. Subsequent experimental synthesis and validation confirm these predictions, yielding sensors with markedly improved sensitivity, selectivity, and stability for dopamine detection [7].

Theoretical Foundations: A DFT Perspective

DFT calculations provide atomic-level insight into the mechanisms by which CuO enhances the catalytic performance of ZnO for dopamine detection. The primary focus is on analyzing the electronic structure and predicting the energy barriers for the key reactions involved in dopamine oxidation.

Electronic Structure and Reaction Energetics

First-principles calculations reveal that incorporating CuO into ZnO modifies its electronic density of states. A critical finding is the shift of the d-band center of copper closer to the Fermi level in CuO–ZnO composites compared to pure CuO. This shift optimizes the adsorption energy of dopamine and its reaction intermediates onto the sensor surface, facilitating the electron transfer process that is central to electrochemical detection [7].

Furthermore, DFT is used to calculate the reaction energy barrier for the catalytic oxidation of dopamine. For the optimal CuO–ZnO nanoflower structure, this barrier is computed to be a low 0.54 eV. This low energy barrier, predicted theoretically, explains the enhanced reaction kinetics and superior electrocatalytic activity observed experimentally after CuO incorporation [7].

Charge Transfer and Band Alignment

The establishment of a p-n heterojunction at the interface between p-type CuO and n-type ZnO is a cornerstone of the enhancement mechanism. DFT modelling helps visualize the electronic band alignment at this interface. The calculations predict favorable band bending that creates an internal electric field, which in turn promotes the efficient separation of photogenerated (or electrochemically generated) electron-hole pairs. This reduced charge recombination rate directly increases the density of available charge carriers for the dopamine oxidation reaction, thereby amplifying the sensor's signal [7].