Beyond the Hypothesis: Evaluating AI and Machine Learning for Predicting Synthesis Feasibility in Materials and Drug Discovery

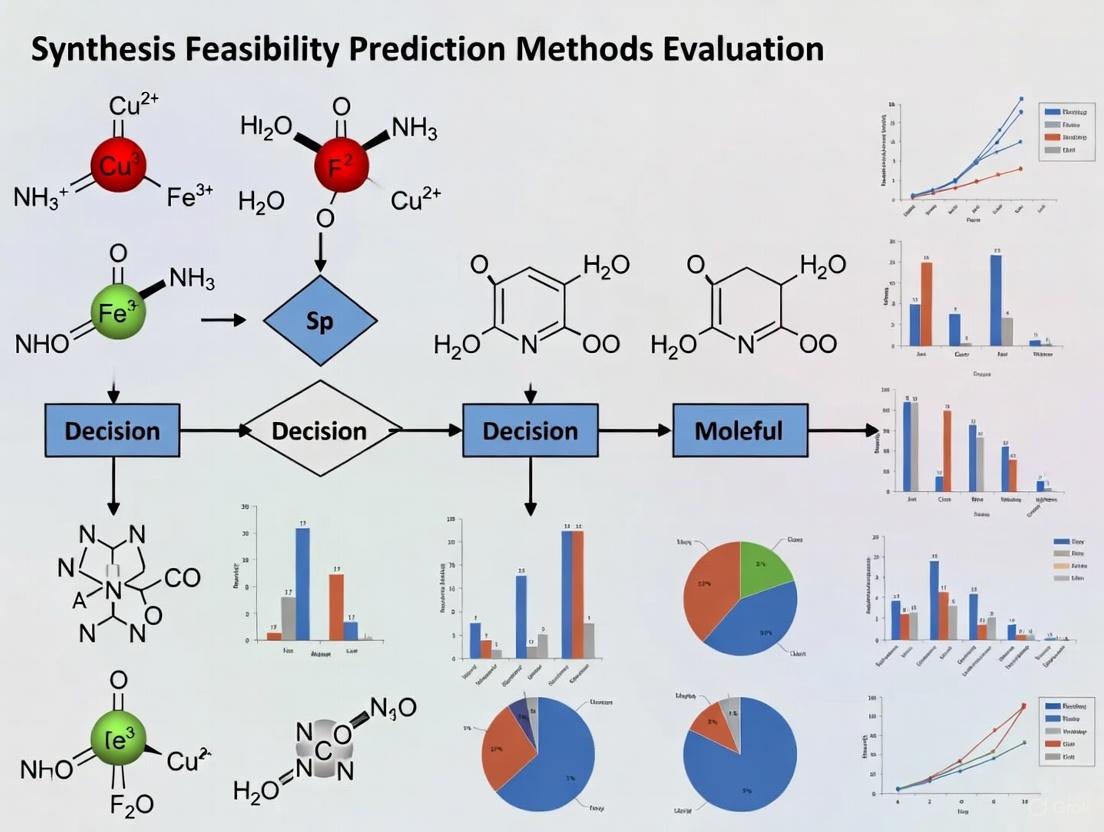

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of modern computational methods for predicting synthesis feasibility, a critical bottleneck in materials science and drug development.

Beyond the Hypothesis: Evaluating AI and Machine Learning for Predicting Synthesis Feasibility in Materials and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of modern computational methods for predicting synthesis feasibility, a critical bottleneck in materials science and drug development. It explores the foundational shift from traditional thermodynamic proxies to data-driven machine learning and AI approaches, including Positive-Unlabeled learning, Large Language Models, and retrosynthetic planning tools. For researchers and drug development professionals, we detail specific methodologies, compare their performance and limitations, and present validation frameworks and benchmarks. The content also addresses practical challenges in implementation and optimization, concluding with a forward-looking perspective on integrating synthesizability prediction into high-throughput and generative discovery pipelines to bridge the gap between computational design and experimental realization.

The Synthesizability Challenge: Why Traditional Metrics Fall Short in Modern Discovery

The acceleration of computational materials discovery has created a critical bottleneck: experimental validation. High-throughput calculations can generate millions of candidate structures, but determining which are practically achievable in the laboratory remains a profound challenge. Synthesizability—the probability that a proposed material can be physically realized under practical laboratory conditions—has emerged as a central focus in modern materials informatics. This concept extends far beyond simple thermodynamic stability to encompass kinetic accessibility, precursor availability, and experimental pathway feasibility. The disconnect between computational prediction and experimental realization is substantial; for instance, among 4.4 million computational structures screened in a recent study, only approximately 1.3 million were calculated to be synthesizable, and far fewer were successfully synthesized in practice [1].

The field has evolved through multiple paradigms for assessing synthesizability. Traditional approaches relying solely on formation energy and energy above the convex hull (E hull) provide incomplete guidance, as they overlook kinetic barriers and finite-temperature effects that govern synthetic accessibility [1]. Numerous structures with favorable formation energies have never been synthesized, while various metastable structures with less favorable formation energies are routinely produced in laboratories [2]. This limitation has spurred the development of more sophisticated computational frameworks that integrate machine learning, natural language processing, and network science to predict synthesizability with greater accuracy and practical utility.

Comparative Analysis of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

Traditional Thermodynamic and Kinetic Approaches

Conventional synthesizability assessment has primarily relied on density functional theory (DFT) calculations to determine thermodynamic stability metrics. The most common approach involves calculating the energy above the convex hull, which represents the energy difference between a compound and the most stable combination of competing phases at the same composition. Materials on the convex hull (E hull = 0) are thermodynamically stable, while those with positive values are metastable or unstable. However, this approach has significant limitations: it typically calculates internal energies at 0 K and 0 Pa, ignoring the actual thermodynamic stability under synthesis conditions [3]. It also fails to account for kinetic factors, where energy barriers can prevent otherwise energetically favorable reactions [3].

Alternative stability assessments include kinetic stability analysis through computationally expensive phonon spectrum calculations. Structures with imaginary phonon frequencies are considered dynamically unstable, yet such materials are sometimes synthesized despite these predictions [2]. Other traditional methods include phase diagram analysis, which provides more direct correlation with synthesizability by delineating stable phases under varying temperatures, pressures, and compositions. However, constructing complete free energy surfaces for all possible phases remains computationally impractical for high-throughput screening [2].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Traditional Synthesizability Assessment Methods

| Method | Key Metric | Advantages | Limitations | Reported Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamic Stability | Energy above convex hull (E hull) | Strong theoretical foundation; Well-established computational workflow | Ignores kinetic factors; Limited to 0 K/0 Pa conditions | 74.1% [2] |

| Kinetic Stability | Phonon spectrum (lowest frequency) | Assesses dynamic stability; Identifies vibrational instabilities | Computationally expensive; Does not always correlate with experimental synthesizability | 82.2% [2] |

| Phase Diagrams | Free energy surface | Incorporates temperature/pressure effects; More experimentally relevant | Impractical for high-throughput screening; Incomplete data for many systems | Qualitative guidance only |

Modern Data-Driven Approaches

Machine learning methods have emerged as powerful alternatives to traditional physics-based calculations for synthesizability prediction. These approaches learn patterns from existing materials databases and can incorporate both compositional and structural features that influence synthetic accessibility.

The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models (CSLLM) framework represents a significant advancement, utilizing three specialized LLMs to predict synthesizability, synthetic methods, and suitable precursors for arbitrary 3D crystal structures. This system achieves remarkable accuracy (98.6%) by leveraging a comprehensive dataset of 70,120 synthesizable structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) and 80,000 non-synthesizable structures identified through positive-unlabeled learning [2]. The framework introduces an efficient text representation called "material string" that integrates essential crystal information for LLM processing, overcoming previous challenges in representing crystal structures for natural language processing.

Network science approaches offer another innovative methodology, constructing materials stability networks from convex free-energy surfaces and experimental discovery timelines. These networks exhibit scale-free topology with power-law degree distributions, where highly connected "hub" materials (like common oxides) play dominant roles in determining synthesizability. By tracking the temporal evolution of network properties, machine learning models can predict the likelihood that hypothetical materials will be synthesizable [4]. This approach implicitly captures circumstantial factors beyond pure thermodynamics, including the development of new synthesis techniques and precursor availability.

Integrated composition-structure models represent a third category, combining signals from both chemical composition and crystal structure. Compositional signals capture elemental chemistry, precursor availability, and redox constraints, while structural signals capture local coordination, motif stability, and packing environments. These models use ensemble methods like rank-average fusion to leverage both information types, demonstrating state-of-the-art performance in identifying synthesizable candidates from millions of hypothetical structures [1].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Data-Driven Synthesizability Prediction Methods

| Method | Key Features | Dataset Size | Advantages | Reported Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSLLM Framework [2] | Three specialized LLMs for synthesizability, methods, precursors | 150,120 structures | Exceptional generalization; Predicts synthesis routes and precursors | 98.6% (Synthesizability LLM) >90% (Method/Precursor LLMs) |

| Network Science Approach [4] | Materials stability network with temporal dynamics | ~22,600 materials | Captures historical discovery patterns; Identifies promising chemical spaces | Quantitative likelihood scores |

| Integrated Composition-Structure Model [1] | Ensemble of compositional and structural encoders | 178,624 compositions | Combines complementary signals; Effective for screening millions of candidates | Successful experimental synthesis of 7/16 predicted targets |

| Positive-Unlabeled Learning [3] | Semi-supervised learning from positive examples only | 4,103 ternary oxides | Addresses lack of negative examples; Human-curated data quality | Predicts 134/4312 hypothetical compositions as synthesizable |

| Bayesian Deep Learning [5] | Uncertainty quantification for reaction feasibility | 11,669 reactions | Handles limited negative data; Active learning reduces data requirements by 80% | 89.48% (reaction feasibility) |

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Workflow for High-Throughput Synthesizability Assessment

The experimental validation of synthesizability predictions follows a structured pipeline from computational screening to physical synthesis. A representative protocol from a recent large-scale study demonstrates this process [1]:

Phase 1: Computational Screening The initial stage involves applying synthesizability filters to millions of candidate structures. The integrated composition-structure model calculates separate synthesizability probabilities from compositional and structural encoders, then aggregates them via rank-average ensemble (Borda fusion). This approach identified 1.3 million potentially synthesizable structures from an initial pool of 4.4 million candidates [1]. Key filtering criteria include removing platinoid group elements (for cost reasons), non-oxides, and toxic compounds, yielding approximately 500 final candidates for experimental consideration.

Phase 2: Synthesis Planning For high-priority candidates, synthesis planning proceeds in two stages. First, Retro-Rank-In suggests viable solid-state precursors for each target, generating a ranked list of precursor combinations. Second, SyntMTE predicts the calcination temperature required to form the target phase. Both models are trained on literature-mined corpora of solid-state synthesis recipes [1]. Reaction balancing and precursor quantity calculations complete the recipe generation process.

Phase 3: Experimental Execution Selected targets undergo synthesis in high-throughput laboratory platforms. In the referenced study, samples were weighed, ground, and calcined in a benchtop muffle furnace. The entire experimental process for 16 targets was completed in just three days, demonstrating the efficiency gains from careful computational prioritization [1]. Of 24 initially selected targets, 16 were successfully characterized, with 7 matching the predicted structure—including one completely novel material and one previously unreported phase.

CSLLM Experimental Validation Protocol

The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models framework was validated through rigorous testing on diverse crystal structures [2]:

Dataset Construction: Researchers compiled a balanced dataset containing 70,120 synthesizable crystal structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) and 80,000 non-synthesizable structures screened from 1,401,562 theoretical structures via a pre-trained positive-unlabeled learning model. Structures with CLscore <0.1 were considered non-synthesizable, while 98.3% of ICSD structures had CLscores >0.1, validating this threshold.

Model Architecture and Training: The framework employs three specialized LLMs fine-tuned on crystal structure data represented in a custom "material string" format that integrates lattice parameters, composition, atomic coordinates, and symmetry information. This efficient text representation enables LLMs to process complex crystallographic data while conserving essential information for synthesizability assessment.

Generalization Testing: The Synthesizability LLM was tested on structures with complexity considerably exceeding the training data, achieving 97.9% accuracy on these challenging cases. The Method LLM achieved 91.0% accuracy in classifying synthetic methods (solid-state or solution), while the Precursor LLM reached 80.2% success in identifying appropriate precursors for binary and ternary compounds.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Synthesizability Assessment

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSLLM Framework [2] | Software/Model | Predicts synthesizability, methods, and precursors for 3D crystals | High-accuracy screening of theoretical structures |

| Materials Project Database [1] | Data Resource | Provides DFT-calculated structures and properties | Source of hypothetical structures for synthesizability assessment |

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [2] | Data Resource | Experimentally confirmed crystal structures | Source of synthesizable positive examples for model training |

| Retro-Rank-In [1] | Software/Model | Suggests viable solid-state precursors | Retrosynthetic planning for identified targets |

| SyntMTE [1] | Software/Model | Predicts calcination temperatures | Synthesis parameter optimization |

| Thermo Scientific Thermolyne Benchtop Muffle Furnace [1] | Laboratory Equipment | High-temperature solid-state synthesis | Experimental validation of predicted synthesizable materials |

| Positive-Unlabeled Learning Models [3] | Algorithmic Approach | Learns from positive examples only when negative examples are unavailable | Synthesizability prediction when failed synthesis data is scarce |

The evolution from thermodynamic stability to kinetic accessibility represents a paradigm shift in how researchers approach materials discovery. Traditional metrics like energy above the convex hull provide valuable but incomplete guidance, with accuracies around 74-82% in practical synthesizability assessment [2]. Modern data-driven approaches have dramatically improved performance, with the CSLLM framework achieving 98.6% accuracy by leveraging large language models specially adapted for crystallographic data [2].

The most effective synthesizability assessment strategies combine multiple complementary approaches: integrating compositional and structural descriptors [1], leveraging historical discovery patterns through network science [4], and incorporating synthesis route prediction alongside binary synthesizability classification [2]. These integrated pipelines have demonstrated tangible experimental success, transitioning from millions of computational candidates to successfully synthesized novel materials in a matter of days [1].

As synthesizability prediction continues to mature, key challenges remain: improving generalization across diverse material classes, incorporating more sophisticated synthesis condition predictions, and developing standardized benchmarks for model evaluation. The integration of these advanced synthesizability assessments into automated discovery platforms promises to significantly accelerate the translation of computational materials design into practical laboratory realization.

Predicting whether a theoretical material or chemical compound can be successfully synthesized is a fundamental challenge in materials science and chemistry. Accurate synthesizability assessment prevents costly and time-consuming experimental efforts on non-viable targets. For decades, researchers have relied primarily on two categories of computational approaches: thermodynamic stability metrics (particularly energy above convex hull) and expert-derived heuristic rules. While useful as initial filters, these methods suffer from significant limitations that restrict their predictive accuracy and practical utility in real-world discovery pipelines.

The "critical gap" refers to the substantial disconnect between predictions from these traditional methods and experimental synthesizability outcomes. This guide objectively compares the performance of these established approaches against emerging machine learning (ML) and large language model (LLM) alternatives, providing researchers with a clear framework for evaluating synthesis feasibility prediction methods.

Limitations of Energy Above Hull

The energy above convex hull (Eₕᵤₗₗ) has served as the primary thermodynamic metric for assessing compound stability. It represents the energy difference between a compound and the most stable combination of other phases at the same composition from the phase diagram. Despite its widespread use in databases like the Materials Project, Eₕᵤₗₗ exhibits critical limitations when used as a sole synthesizability predictor.

Theoretical Shortcomings

The fundamental assumption that thermodynamic stability guarantees synthesizability represents an oversimplification of real-world synthesis. Energy above hull calculations, typically derived from Density Functional Theory (DFT), only consider zero-Kelvin thermodynamics while ignoring crucial kinetic barriers and finite-temperature effects that govern actual synthesis processes [1] [6]. This method inherently favors ground-state structures, overlooking numerous metastable phases that are experimentally accessible yet lie above the convex hull [7].

The convex hull construction itself presents computational challenges in higher-dimensional composition spaces. For ternary, quaternary, and more complex systems, the algorithm must calculate the minimum energy "envelope" across multiple dimensions in energy-composition space [8]. This process requires extensive reference data for all competing phases, which is often incomplete or computationally prohibitive to generate for novel chemical systems.

Performance and Accuracy Gaps

Recent systematic evaluations reveal significant accuracy limitations in Eₕᵤₗₗ-based synthesizability predictions. When tested on known crystal structures, traditional thermodynamic stability methods (Eₕᵤₗₗ ≥ 0.1 eV/atom) achieve only 74.1% accuracy in identifying synthesizable materials [7]. Similarly, kinetic stability assessments based on phonon spectra analysis (lowest frequency ≥ -0.1 THz) reach just 82.2% accuracy [7].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

| Prediction Method | Accuracy | True Positive Rate | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Above Hull (≥0.1 eV/atom) | 74.1% | Not Reported | Overlooks metastable phases |

| Phonon Spectrum Analysis | 82.2% | Not Reported | Computationally expensive |

| Composition-only ML Models | Varies | Poor on stability prediction | Lacks structural information |

| Fine-tuned LLMs (Structural) | 89-98.6% | High | Requires structure description |

| PU-GPT-embedding Model | Highest | ~90% | Needs text representation |

The core performance issue stems from inadequate error cancellation. While DFT calculations of formation energies may approach chemical accuracy, the convex hull construction depends on tiny energy differences between compounds—typically 1-2 orders of magnitude smaller than the formation energies themselves [6]. These subtle thermodynamic competitions fall within the error range of high-throughput DFT, leading to unreliable stability classifications, particularly for compositions near the hull boundary.

Limitations of Heuristic Rules

Heuristic rules based on chemical intuition and known reactivity principles represent the traditional knowledge-based approach to reaction feasibility assessment. While valuable for expert-guided exploration, these rules exhibit systematic limitations in comprehensive synthesizability prediction.

Knowledge Gap and Coverage Limitations

Heuristic approaches fundamentally suffer from knowledge gaps and human bias in their construction. Rules derived from known chemical space inevitably reflect historical synthetic preferences rather than the full scope of potentially viable reactions [5]. This creates a discovery bottleneck where unconventional but synthetically accessible compounds and reactions are systematically overlooked.

The application of heuristic rules also faces a scalability challenge. Manual rule application becomes practically impossible when screening thousands or millions of candidate materials or reactions. While computational implementations can automate this process, the underlying rules remain inherently limited by their predefined constraints and inability to generalize beyond their training domain.

Performance in Reaction Feasibility Assessment

In organic chemistry, heuristic rules struggle with accurate reaction feasibility prediction, particularly for complex molecular systems. In acid-amine coupling reactions—one of the most extensively studied reaction types—even experienced bench chemists find assessing feasibility and robustness challenging based on rules alone [5].

The most significant limitation emerges in robustness prediction, where heuristic rules perform particularly poorly. Reaction outcomes can be influenced by subtle environmental factors (moisture, oxygen, light), analytical methods, and operational variations that defy simple rule-based categorization [5]. This sensitivity often makes certain reactions difficult to replicate across laboratories, creating significant challenges for process scale-up where reliability is paramount.

Emerging Alternatives: Machine Learning Approaches

Next-generation synthesizability prediction tools are overcoming traditional limitations through advanced machine learning and natural language processing techniques applied to both structural and reaction feasibility assessment.

ML for Crystal Structure Synthesizability

Modern ML frameworks for crystal synthesizability prediction integrate multiple data modalities to achieve unprecedented accuracy. The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM) framework utilizes three specialized LLMs to predict synthesizability, synthetic methods, and suitable precursors respectively [7]. This integrated system achieves 98.6% accuracy on testing data—dramatically outperforming traditional thermodynamic and kinetic stability methods [7].

Alternative architectures like the PU-GPT-embedding model first convert text descriptions of crystal structures into high-dimensional vector representations, then apply positive-unlabeled learning classifiers. This approach demonstrates superior performance compared to both traditional graph-based neural networks and fine-tuned LLMs acting as standalone classifiers [9]. The method also offers substantial cost reductions—approximately 98% for training and 57% for inference compared to direct LLM fine-tuning [9].

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Synthesizability Prediction Models

| Model/Platform | Training Data | Key Features | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSLLM Framework | 70,120 ICSD structures + 80,000 non-synthesizable structures | Material string representation, multi-task learning | Predicts methods & precursors (>90% accuracy) |

| PU-GPT-embedding | 100,195 text-described structures from Materials Project | Text-embedding-3-large representations, PU-classifier | Outperforms graph-based models in TPR/PREC |

| Bayesian Deep Learning (Organic) | 11,669 acid-amine coupling reactions | Uncertainty disentanglement, active learning | 89.48% feasibility accuracy, 80% data reduction |

ML for Organic Reaction Feasibility

For organic reactions, Bayesian deep learning approaches demonstrate remarkable performance in predicting reaction feasibility and robustness. By integrating high-throughput experimentation (HTE) with Bayesian neural networks, researchers achieved 89.48% accuracy and an F1 score of 0.86 for acid-amine coupling reaction feasibility prediction [5]. This approach explored 11,669 distinct reactions covering 272 acids, 231 amines, and multiple reagents and conditions—creating the most extensive single reaction-type HTE dataset at industrially relevant scales [5].

Fine-grained uncertainty analysis within these models enables efficient active learning, reducing data requirements by approximately 80% while maintaining prediction accuracy [5]. More importantly, these models successfully correlate intrinsic data uncertainty with reaction robustness, providing valuable guidance for process scale-up where reliability is critical.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

High-Throughput Experimentation for Organic Reactions

The generation of high-quality training data for organic reaction feasibility models involves automated high-throughput experimentation platforms. The detailed protocol for acid-amine coupling reaction screening includes:

Substrate Selection: 272 commercially available carboxylic acids and 231 amines selected using diversity-guided down-sampling to represent patent chemical space, constrained to substrates with single reactive groups to minimize ambiguity [5].

Reaction Execution: Conducted at 200-300 μL scale in 156 instrument hours, covering 6 condensation reagents, 2 bases, and 1 solvent system [5].

Outcome Analysis: Yield determination via uncalibrated UV absorbance ratio in LC-MS following established industry protocols [5].

Negative Example Incorporation: Integration of 5,600 potentially negative reactions identified through expert rules based on nucleophilicity and steric hindrance effects [5].

This protocol generated 11,669 reactions for 8,095 target products, creating a dataset with substantially broader substrate space coverage compared to previous HTE studies focused on niche chemical spaces [5].

Crystallographic Synthesizability Assessment

The experimental workflow for crystal synthesizability prediction involves:

Crystal Synthesizability Prediction Workflow

Data Curation: Balanced datasets combining synthesizable structures from ICSD (70,120 structures) and non-synthesizable structures identified through PU-learning screening of 1.4 million theoretical crystals [7].

Structure Representation: Conversion of CIF-format crystal structures to text descriptions using tools like Robocrystallographer [9]. For LLM-based approaches, development of efficient "material string" representations that comprehensively encode lattice parameters, composition, atomic coordinates, and symmetry in reversible text format [7].

Model Training: Fine-tuning of base LLM models (GPT-4o-mini) on text structure descriptions, or training of PU-classifier neural networks on LLM-derived embedding representations [9].

Experimental Validation: For promising candidates, synthesis planning via precursor-suggestion models (Retro-Rank-In) and calcination temperature prediction (SyntMTE), followed by automated solid-state synthesis and XRD characterization [1].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Synthesizability Prediction

| Tool/Platform | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Robocrystallographer | Software Library | Generates text descriptions of crystal structures | Preparing structural data for LLM processing |

| CSLLM Framework | Specialized LLMs | Predicts synthesizability, methods, and precursors | High-accuracy crystal synthesizability assessment |

| AutoMAT | Cheminformatics Toolkit | Molecular visualization and descriptor calculation | Organic reaction analysis and feature engineering |

| HTE Platform (CASL-V1.1) | Automated Lab System | High-throughput reaction execution at μL scale | Generating experimental training data for organic reactions |

| Bayesian Neural Networks | ML Architecture | Predicts reaction feasibility with uncertainty quantification | Organic reaction robustness assessment |

| PU-Learning Models | ML Framework | Classifies synthesizability from positive-unlabeled data | Crystal synthesizability prediction |

This comparison demonstrates the substantial limitations of energy above hull and heuristic rules as comprehensive synthesizability predictors. While Eₕᵤₗₗ provides valuable thermodynamic insights, its 74.1% accuracy ceiling and failure to account for kinetic factors restrict its utility as a standalone screening tool. Similarly, heuristic rules, while encoding valuable chemical intuition, lack the scalability and coverage required for modern materials and reaction discovery.

Emerging ML and LLM approaches achieve dramatically higher accuracy (89-98.6%) by directly learning synthesizability patterns from experimental data rather than relying solely on thermodynamic principles or predefined rules. These methods offer the additional advantage of predicting synthetic methods and precursors—critical practical information absent from traditional approaches. For researchers navigating synthesizability assessment, the evidence strongly suggests integrating these data-driven approaches with traditional methods for optimal discovery efficiency.

Predicting whether a chemical reaction will succeed is a fundamental challenge in chemistry and drug discovery. However, this field is plagued by a pervasive data problem: a critical scarcity of negative examples (failed reactions) and unpublished failures. This bias in the scientific record occurs because literature and patents predominantly report successful experiments, creating a skewed dataset that does not represent the true exploration space of chemistry [5]. This lack of negative data severely impedes the development of robust machine learning models for synthesis feasibility prediction, as these models require comprehensive data on both successes and failures to learn accurate boundaries between feasible and infeasible reactions.

The high failure rate in drug development underscores the real-world impact of this problem. Approximately 90% of clinical drug development fails, with about 40-50% of failures attributed to a lack of clinical efficacy, often tracing back to inadequate predictive models during early discovery [10]. This review objectively compares contemporary computational methods designed to overcome the negative data gap, evaluating their experimental performance, underlying protocols, and practical applicability for researchers and drug development professionals.

Comparative Analysis of Feasibility Prediction Methods

The following table summarizes the core characteristics and performance metrics of leading synthesis feasibility prediction methods, highlighting their approaches to handling data scarcity.

Table 1: Comparison of Synthesis Feasibility Prediction Methods

| Method Name | Core Approach | Key Differentiator | Reported Accuracy / Performance | Data Requirements & Handling of Negative Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FSscore [11] | Machine Learning (Graph Attention Network) | Fine-tuned with human expert feedback on specific chemical spaces. | Enables sampling of >40% synthesizable molecules while maintaining good docking scores. | Pre-trained on large reaction datasets; fine-tuned with as few as 20-50 human-labeled pairs. |

| BNN + HTE Framework [5] | Bayesian Neural Network (BNN) fed by High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE). | Uses extensive, purpose-built HTE data including negative results. | 89.48% accuracy; 0.86 F1 score for reaction feasibility prediction. | Trained on 11,669 reactions, including 5,600 negative examples introduced via expert rules. |

| SCScore [11] | Machine Learning (Fingerprint-based) | Predicts synthetic complexity based on required reaction steps. | Benchmarks well on reaction step length; performs poorly in feasibility prediction tasks [11]. | Trained on the assumption that reactants are simpler than products; struggles with generalizability. |

| SAscore [11] | Rule-based / Fragment-based | Penalizes rare fragments and complex structural features. | Tends to misclassify large but synthetically accessible molecules [11]. | Relies on frequency of fragments in a reference database; does not explicitly learn from reaction outcomes. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Workflows

The High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) and Bayesian Learning Pipeline

The most comprehensive approach to directly addressing the data scarcity problem involves generating a large, balanced dataset from scratch. A landmark 2025 study detailed a synergistic protocol combining HTE and Bayesian deep learning [5].

Protocol 1: Generating a Balanced Dataset for Feasibility Prediction

Chemical Space Definition and Down-Sampling:

- The target reaction (e.g., acid-amine coupling) is defined.

- Commercially available substrates (acids and amines) are selected to structurally represent those found in industrial patent data, using a diversity-guided sampling strategy to ensure broad coverage [5].

Incorporating Expert Rules for Negative Data:

- To proactively include negative examples, known chemical concepts (e.g., low nucleophilicity, high steric hindrance) are used to design reaction combinations that are a priori likely to fail. This step introduced 5,600 potential negative examples into the final dataset [5].

Automated High-Throughput Experimentation:

- An automated HTE platform (e.g., CASL-V1.1) executes thousands of unique reactions at a micro-scale (200–300 μL).

- The workflow includes reagent dispensing, reaction incubation, and automated analysis via Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS).

- Reaction feasibility is determined based on the detection and uncalibrated UV yield of the target product [5].

Model Training with Uncertainty Quantification:

- A Bayesian Neural Network (BNN) is trained on the HTE data.

- The model learns to predict reaction feasibility (a classification task) and, crucially, also estimates the uncertainty of its own predictions. This helps identify when the model is evaluating reactions outside its reliable knowledge domain [5].

The following diagram illustrates this integrated workflow, from chemical space exploration to model deployment.

Human-in-the-Loop Active Learning

An alternative or complementary strategy to generating physical HTE data is to leverage human expertise more directly through active learning.

Protocol 2: Active Learning with Human Feedback

- Baseline Model Pre-training: A model is first pre-trained on a large, general dataset of reactant-product pairs to establish a baseline understanding of synthesizability [11].

- Focused Fine-Tuning: The baseline model is then fine-tuned on a specific chemical space of interest (e.g., natural products, PROTACs).

- Expert Preference Labeling: For fine-tuning, expert chemists provide binary preference labels on pairs of molecules, indicating which is easier to synthesize. This frames the task as a ranking problem, which is less biased than absolute scoring [11].

- Iterative Refinement: The model's performance is evaluated on the focused scope, and additional rounds of expert labeling can be performed to further refine its accuracy, creating a continuous feedback loop [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Feasibility Studies

| Item | Function / Description | Application in Feasibility Research |

|---|---|---|

| Automated HTE Platform (e.g., CASL-V1.1 [5]) | Integrated robotic system for dispensing, reaction execution, and work-up. | Enables rapid, parallel synthesis of thousands of reactions to build comprehensive datasets containing both positive and negative results. |

| Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) | Analytical instrument for separating reaction components and detecting/identifying products. | The primary tool for high-throughput analysis of reaction outcomes in HTE campaigns, used to determine success (feasibility) and yield [5]. |

| Bayesian Neural Network (BNN) | A type of machine learning model that can estimate uncertainty in its predictions. | Critical for predicting not just feasibility, but also the confidence of the prediction; allows identification of out-of-domain reactions and guides active learning [5]. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | ML model that operates directly on molecular graph structures. | Used in methods like FSscore to capture complex structural features (including stereochemistry) that simpler fingerprint-based models might miss [11]. |

| Chemical Space Visualization (e.g., t-SNE) | A dimensionality reduction technique for visualizing high-dimensional data. | Used to validate that a sampled set of substrates adequately represents the broader, target chemical space (e.g., from patents) [5]. |

| Expert-Rule Library | A curated set of chemical principles (e.g., steric hindrance, nucleophilicity). | Used to systematically introduce likely negative examples into a dataset during the experimental design phase, mitigating data bias [5]. |

The scarcity of negative examples remains a significant bottleneck in developing truly reliable synthesis feasibility predictors. Comparative analysis reveals that methods relying solely on published data are inherently limited by its biased nature. The most promising path forward involves the creation of large, purpose-built datasets that include negative results, achieved through High-Throughput Experimentation and the strategic use of expert rules [5]. Furthermore, integrating human expert feedback via active learning frameworks provides a powerful mechanism to continuously refine models for specific chemical domains of interest [11].

The emerging ability of Bayesian models to provide uncertainty quantification alongside predictions is a critical advancement [5]. It not only makes the models more trustworthy but also directly enables their use in navigating chemical space and prioritizing experiments. As these data-driven, human-aware, and uncertainty-calibrated methods mature, they hold the potential to de-risk the early stages of drug discovery and molecular design, ultimately helping to improve the efficiency of the research and development pipeline.

The acceleration of materials and drug discovery hinges on the accurate prediction of synthesis feasibility. However, the fundamental challenges, data requirements, and computational approaches differ significantly between the domains of solid-state inorganic crystals and organic drug molecules. Inorganic materials discovery often grapples with the stability and formation energy of complex crystalline structures, where the goal is to identify novel, stable compounds that can be experimentally realized from a vast hypothetical space [12] [9]. Conversely, organic molecular discovery focuses on navigating reaction feasibility and synthetic pathways for often complex, bioactive molecules, where the objective is to prioritize routes that are efficient, robust, and scalable [11] [5] [13]. This guide objectively compares the performance of prevailing computational methods in each domain, underpinned by experimental data and structured within the broader thesis of evaluating synthesis feasibility prediction methodologies. The contrasting needs—predicting the formability of a crystal lattice versus the executable route for a carbon-based molecule—define a frontier in modern computational chemistry.

Comparative Analysis of Prediction Methods and Performance

The following tables summarize the core methodologies and quantitative performance of synthesis feasibility prediction approaches for inorganic crystals and organic drug molecules.

Table 1: Synthesis Feasibility Prediction Methods for Inorganic Crystals

| Method / Model Name | Core Methodology / Input | Key Performance Metrics (Approx.) | Experimental Validation / Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| DTMA Framework [12] | Data-driven multi-aspect filtration (synthesizability, oxidation states, reaction pathways). | Successful synthesis of computationally identified targets (ZnVO₃, YMoO₃₋ₓ). | Ultrafast synthesis confirmed ZnVO₃ in a disordered spinel structure; YMoO₃₋ₓ composition was identified as Y₄Mo₄O₁₁ via microED [12]. |

| PU-GPT-embedding [9] | LLM-based text embedding of crystal structure description + PU-learning classifier. | High performance, outperforming graph-based models [9]. | Provides human-readable explanations for predictions, guiding the modification of hypothetical structures [9]. |

| StructGPT-FT [9] | Fine-tuned LLM using text description of crystal structure (formula + structure). | Performance comparable to bespoke graph-neural networks [9]. | Demonstrates that text descriptions can be as effective as traditional graph representations for structure-based prediction [9]. |

| PU-CGCNN [9] | Graph neural network on crystal structure + Positive-Unlabeled learning. | Baseline performance for structure-based prediction [9]. | A established bespoke ML model; serves as a benchmark for newer methods [9]. |

Table 2: Synthesis Feasibility & Reaction Prediction for Organic Drug Molecules

| Method / Tool Name | Core Methodology / Input | Key Performance Metrics (Approx.) | Experimental Validation / Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| FSscore [11] | GNN pre-trained on reactions, then fine-tuned with human expert feedback. | Enabled sampling of >40% synthesizable molecules from a generative model while maintaining good docking scores [11]. | Distinguishes hard- from easy-to-synthesize molecules; incorporates chemist intuition via active learning [11]. |

| MEDUSA Search [14] | ML-powered search of tera-scale HRMS data with isotope-distribution-centric algorithm. | Discovers previously unknown reaction pathways from existing data [14]. | Identified a novel heterocycle-vinyl coupling process in the Mizoroki-Heck reaction without new experiments [14]. |

| Bayesian Neural Network (Reaction Feasibility) [5] | Bayesian DL model trained on high-throughput experimentation (HTE) data (11,669 reactions). | 89.48% Accuracy, F1-score: 0.86 for acid-amine coupling reaction feasibility [5]. | Active learning based on model uncertainty reduced data requirements by ~80%; correlates data uncertainty with reaction robustness [5]. |

| Informeracophore & ML [15] | Machine-learned representation of minimal structure essential for bioactivity (scaffold-centric). | Reduces biased intuitive decisions, accelerates hit identification and optimization [15]. | Informs rational drug design by identifying key molecular features for activity from ultra-large chemical libraries [15]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Cited Studies

Protocol: High-Throughput Validation of Organic Reaction Feasibility

This protocol is derived from the large-scale study on acid-amine coupling reactions [5].

- Chemical Space Formulation & Substrate Sampling: Define a finite, industrially relevant reaction space based on patent data. Use a diversity-guided down-sampling strategy (e.g., MaxMin sampling within substrate categories) to select commercially available carboxylic acids and amines that are representative of the broader patent space.

- Automated High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE): Execute reactions on an automated HTE platform.

- Reaction Scale: 200–300 µL.

- Replication: Reactions are set up in high-density microplates.

- Condition Variants: Systematically vary key parameters, such as condensation reagents (e.g., 6 types) and bases (e.g., 2 types), while keeping the solvent constant.

- Reaction Outcome Analysis:

- Technique: Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS).

- Yield Determination: Use the uncalibrated ratio of ultraviolet (UV) absorbance at the corresponding retention time to determine product yield.

- Data Processing & Model Training:

- Data Compilation: Compile results, including both positive and negative outcomes, into a structured dataset.

- Model Training: Train a Bayesian Neural Network (BNN) using the HTE data. The model input includes molecular descriptors of the substrates and the reaction conditions.

- Active Learning: Use the model's prediction uncertainty to guide the selection of the most informative subsequent experiments, iteratively improving the model with minimal data.

Protocol: Data-Driven Discovery and Synthesis of Inorganic Crystals

This protocol outlines the Design-Test-Make-Analyze (DTMA) paradigm for novel inorganic crystals [12].

- Computational Design & Filtration:

- Input: A large space of hypothetical ternary oxide compositions and structures.

- Filtration Steps:

- Synthesizability Prediction: Use data-driven models to assess the likelihood of a compound being synthesizable.

- Oxidation State Probability: Calculate the probability of formation for predicted oxidation states.

- Reaction Pathway Analysis: Evaluate potential reaction pathways for stability.

- Target Selection & Ultrafast Synthesis:

- Select top candidate compositions that pass all computational filters (e.g., ZnVO₃, YMoO₃).

- Synthesize the target compounds using high-temperature methods (e.g., ultrafast heating at ~1500°C for seconds).

- Structural & Compositional Validation:

- Technique 1 (Primary): X-ray Diffraction (XRD) to determine the crystal structure and phase purity.

- Technique 2 (Advanced): Micro-electron Diffraction (MicroED) for nano-crystalline materials to unambiguously solve complex structures.

- Technique 3 (Computational Validation): Validate the experimental crystal structure with Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations to confirm its stability.

Comparison of Synthesis Feasibility Evaluation Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Synthesis Feasibility Research

| Item / Resource | Function / Application | Domain |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Platform [5] | Automated execution of thousands of micro-scale reactions to generate consistent feasibility/robustness data. | Organic |

| Make-on-Demand Chemical Libraries [15] | Ultra-large (10⁵ - 10¹¹ compounds) virtual libraries of readily synthesizable molecules for virtual screening. | Organic |

| Robocrystallographer [9] | Software that generates human-readable text descriptions of crystal structures from CIF files for LLM-based prediction. | Inorganic |

| Hydroxyapatite (HAP) & Substituted Variants [16] | Biocompatible inorganic nanomaterial used as a carrier for drug molecules to improve dissolution rate and study amorphous confinement. | Hybrid |

| Mesoporous Silica/ Silicon [17] | Substrate with tunable pore size (2-50 nm) for confining drug molecules to stabilize the amorphous state and study crystallisation behaviour. | Hybrid |

| Isotope-Distribution-Centric Search Algorithm [14] | Core algorithm for mining tera-scale HRMS data to discover novel reactions and validate hypotheses without new experiments. | Organic |

The prediction of synthesis feasibility is a critical bottleneck in the discovery pipelines for both inorganic crystals and organic drug molecules, yet the domains demand distinct strategies. Inorganic crystal research is increasingly leveraging structure-based descriptions and LLM-embeddings to predict the formability of hypothetical materials from large databases, with explanation capabilities guiding design [12] [9]. In contrast, organic molecule research relies heavily on reaction-based data, high-throughput experimentation, and human-in-the-loop scoring to assess synthetic accessibility and reaction robustness for bioactive compounds [11] [5]. The experimental data and comparative analysis presented herein underscore that while the core computational philosophy is shared, the optimal methods are highly domain-specific. Future progress in evaluating synthesis feasibility methods will likely involve cross-pollination of ideas, such as applying robust uncertainty quantification from organic chemistry to inorganic discovery and utilizing explainable AI from materials science to demystify complex reaction predictions.

A Toolkit for Predictions: From PU-Learning to Large Language Models

In the field of machine learning, particularly for data-driven domains like drug discovery, the scarcity of reliably labeled data often poses a significant bottleneck. Traditional supervised learning requires a complete set of labeled examples from all classes, which can be expensive, time-consuming, or practically impossible to obtain for many scientific applications. Positive-Unlabeled (PU) learning has emerged as a powerful semi-supervised approach to address this exact challenge. PU learning aims to train effective binary classifiers using only a set of labeled positive instances and a set of unlabeled instances (which may contain both positive and negative examples) [18]. This capability is particularly valuable for tasks such as predicting disease-related genes, identifying drug-target interactions, or detecting polypharmacy side effects, where confirming negative cases is as difficult, if not more so, than identifying positive ones [18] [19] [20].

The core challenge that PU learning tackles is the absence of confirmed negative examples during training. A standard machine learning model trained naively on such data would learn to predict the "labeled" and "unlabeled" status rather than the underlying "positive" or "negative" class [18]. PU learning algorithms overcome this through various strategies, most commonly a two-step approach: first, identifying a set of reliable negative instances from the unlabeled set, and second, training a classifier to distinguish between the labeled positives and these reliable negatives [18] [21]. The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of a typical two-step PU learning process.

Core Methodologies in PU Learning

PU learning methods can be broadly categorized based on their underlying strategy for handling the unlabeled data. The table below summarizes the three primary methodological frameworks.

Table: Key Methodological Frameworks in PU Learning

| Method Category | Core Principle | Representative Algorithms |

|---|---|---|

| Two-Step Approach | Identifies reliable negative samples from the unlabeled set, then uses them to train a standard classifier [18] [21]. | Spy-EM [20], DDI-PULearn [21], PUDTI [20] |

| Biased Learning | Treats all unlabeled samples as negative but employs noise-robust techniques to mitigate the resulting label noise [22]. | Cost-sensitive learning [22] |

| Multitasking & Hybrid | Frames PU learning as a multi-objective problem or combines it with other paradigms to enhance performance [22] [23]. | EMT-PU [22], PU-Lie [23] |

The Two-Step Approach and Its Variants

The most popular strategy in PU learning is the two-step approach [18]. The first step (Phase 1A) involves extracting reliable negative examples. This is often done by training a classifier to distinguish the labeled positives from the unlabeled set. Instances that the model classifies with the lowest probability of being positive are deemed reliable negatives, operating under the smoothness and separability assumptions—that similar instances have similar class probabilities, and that a clear boundary exists between classes [18]. Some methods, like S-EM (Spy with Expectation Maximization), introduce "spy" instances—randomly selected positives placed into the unlabeled set—to help determine a probability threshold for identifying reliable negatives [18] [20].

An optional extension (Phase 1B) uses a semi-supervised step to expand the reliable negative set. A classifier is trained on the initial positives and reliable negatives, then used to classify the remaining unlabeled instances. Those predicted as negative with high confidence are added to the reliable negative set [18]. Finally, in Phase 2, a final classifier is trained on the labeled positives and the curated reliable negatives to create a model that predicts the true class label [18].

Evolutionary Multitasking and Hybrid Models

Recent research explores more complex frameworks, such as Evolutionary Multitasking (EMT). The EMT-PU method, for example, formulates PU learning as a bi-task optimization problem [22]. One task focuses on the standard PU classification goal of distinguishing positives and negatives from the unlabeled set. A second, auxiliary task focuses specifically on discovering more reliable positive samples from the unlabeled data. The two tasks are solved by separate populations that engage in bidirectional knowledge transfer, enhancing overall performance, especially when labeled positives are very scarce [22].

Other hybrid models, like PU-Lie for deception detection, integrate PU learning objectives with feature engineering. This model combines frozen BERT embeddings with handcrafted linguistic features, using a PU learning objective to handle extreme class imbalance effectively [23].

Performance Comparison: PU Learning Methods and Benchmarks

Evaluating PU learning models presents a unique challenge because standard metrics, which rely on known true negatives, can be misleading [24]. Performance is often assessed via cross-validation on benchmark datasets or by comparing predicted novel interactions against external databases.

Comparative Performance on Classification Tasks

The following table summarizes the reported performance of various PU learning methods across different studies and datasets, highlighting their effectiveness in specific applications.

Table: Performance Comparison of PU Learning Methods and Baselines

| Method | Domain / Dataset | Key Performance Metric & Result | Comparison with Baselines |

|---|---|---|---|

| GA-Auto-PU, BO-Auto-PU, EBO-Auto-PU [18] | 60 benchmark datasets | Statistically significant improvements in predictive accuracy; Large reduction in computational time for BO/EBO vs. GA. | Outperformed established PU methods (e.g., S-EM, DF-PU). |

| NAPU-bagging SVM [25] | Virtual screening for multitarget drugs | High true positive rate (recall) while managing false positive rate. | Matched or surpassed state-of-the-art Deep Learning methods. |

| EMT-PU [22] | 12 UCI benchmark datasets | Consistently outperformed several state-of-the-art PU methods in classification accuracy. | Superior performance demonstrated through comprehensive experiments. |

| PUDTI [20] | Drug-Target Interaction (DTI) prediction on 4 datasets (Enzymes, etc.) | Achieved the highest AUC (Area Under the Curve) among 7 state-of-the-art methods on all 4 datasets. | Outperformed BLM, RLS-Avg, RLS-Kron, KBMF2K. |

| DDI-PULearn [21] | DDI prediction for 548 drugs | Superior performance compared to two baseline and five state-of-the-art methods. | Significant improvement over methods using randomly selected negatives. |

| PU-Lie [23] | Diplomacy deception dataset (highly imbalanced) | New best macro F1-score of 0.60, focusing on the critical deceptive class. | Outperformed deep, classical, and graph-based models with 650x fewer parameters. |

Impact of Negative Sample Selection

A critical factor influencing performance is the strategy for handling negative samples. The PUDTI framework demonstrated this by comparing its negative sample extraction method (NDTISE) against random selection and another method (NCPIS) on a DTI dataset. When used with classifiers like SVM and Random Forest, NDTISE consistently led to higher performance, underscoring that the quality of identified reliable negatives is paramount [20]. Using randomly selected negatives, a common baseline approach, often results in over-optimistic and inaccurate models because the "negative" set is contaminated with hidden positives [25] [20].

Experimental Protocols and Research Toolkit

To ensure reproducibility and guide implementation, this section outlines a standard experimental protocol for a two-step PU learning method and details the essential "research reagents" — the datasets, features, and algorithms required.

Detailed Protocol: Two-Step PU Learning with NDTISE

The PUDTI framework for screening drug-target interactions provides a robust, illustrative protocol [20]:

- Feature Vector Representation: Represent each drug-target pair (DTP) as a feature vector. This often involves integrating multiple sources of biological information, such as drug chemical structures, target protein sequences, and known interaction networks.

- Feature Selection: Rank features (e.g., using a method based on discriminant capability) and select a top set (e.g., 300 features) to reduce dimensionality and mitigate overfitting.

- Reliable Negative Extraction (NDTISE): This is the first step of PU learning.

- Train a model to distinguish the labeled positive DTPs from the unlabeled DTPs.

- Use the model's predictions (e.g., incorporating a spy technique) to identify a set of strong negative DTPs with high confidence.

- Similarity Weight Calculation: For the remaining ambiguous (unlabeled) DTPs, calculate a similarity weight based on their likeness to the positive set and the reliable negative set.

- Classifier Training with Optimization: Train the final classifier (e.g., an SVM) using the positive set and the extracted reliable negatives. The similarity weights of the ambiguous samples can be incorporated into the model's objective function to guide learning. Hyperparameters (e.g., SVM parameters C1, C2) are typically optimized via grid search (e.g., within a range like [2⁻⁵, 2⁵]).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Essential Components for PU Learning Experiments in Bioinformatics

| Reagent / Resource | Function & Description | Example Instances |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Labeled Data | The small set of confirmed positive instances used for initial training. | Known disease genes [18]; Validated Drug-Target Interactions (DTIs) from DrugBank [20]; Known polypharmacy side effects [19]. |

| Unlabeled Data | The larger set of instances with unknown status, which contains hidden positives and negatives. | Genes not experimentally validated [18]; Unobserved/untested drug-target pairs [20] [21]; All other drug pairs for side effect prediction [19]. |

| Feature Representation | Numerical vectors representing each instance for model consumption. | Molecular fingerprints (ECFP4) [25]; Drug similarity measures [21]; Linguistic features (pronoun ratios, sentiment) [23]. |

| Base Classifier Algorithm | The core learning algorithm used for classification. | Support Vector Machine (SVM) [25] [20] [21]; Deep Forest [18]; One-Class SVM (OCSVM) [21]. |

| Evaluation Framework | The method for assessing model performance in the absence of true negatives. | Adjusted confusion matrix using class prior probability [24]; Cross-validation on benchmark datasets [18] [22]; Validation against external databases [20] [21]. |

Positive-Unlabeled learning represents a pragmatic and powerful paradigm for advancing research in domains plagued by incomplete labeling. As demonstrated across numerous applications in bioinformatics and text mining, PU learning methods consistently outperform approaches that rely on randomly selected negative samples [20] [21]. The ongoing development of Automated Machine Learning (Auto-ML) systems for PU learning, such as BO-Auto-PU and EBO-Auto-PU, is making these techniques more accessible and computationally efficient, broadening their applicability [18]. Furthermore, the exploration of novel frameworks like evolutionary multitasking [22] and the integration of PU learning with interpretable, lightweight hybrid models [23] point toward a future where PU learning becomes even more robust, scalable, and integral to the discovery process in science and industry. For researchers in synthesis feasibility and drug development, mastering PU learning is no longer a niche skill but a necessary tool for leveraging the full potential of their often limited and complex datasets.

The acceleration of materials discovery through machine learning represents a paradigm shift in materials science, drug development, and related fields. Among various computational approaches, graph neural networks (GNNs) have emerged as a powerful framework for predicting material properties directly from atomic structures. These models treat crystal structures as graphs where atoms serve as nodes and chemical bonds as edges, enabling comprehensive capture of critical structural information. The ability to predict material properties accurately is essential for screening hypothetical materials generated by modern deep learning models, as conventional methods like density functional theory (DFT) calculations remain computationally expensive [26].

Within this landscape, two architectures have gained significant traction: the Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Network (CGCNN) and the Atomistic Line Graph Neural Network (ALIGNN). These models represent different philosophical approaches to encoding structural information, with CGCNN utilizing a straightforward crystal graph representation while ALIGNN explicitly incorporates higher-order interactions through angle information. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these architectures, their performance characteristics, and implementation considerations to assist researchers in selecting appropriate models for materials property prediction tasks.

Architectural Foundations: How CGCNN and ALIGNN Process Crystal Structures

CGCNN: Direct Crystal Graph Representation

The Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Network (CGCNN) introduced a fundamental advancement by representing crystal structures as multigraphs where atoms form nodes and edges represent either bonds or periodic interactions between atoms [27]. The model employs a convolutional operation that aggregates information from neighboring atoms to learn material representations. Specifically, for each atom in the crystal, CGCNN considers its neighboring atoms within a specified cutoff radius, creating a local environment that forms the basis for message passing [26]. This approach allows the model to learn invariant representations of crystals that can be utilized for various property prediction tasks.

The architectural simplicity of CGCNN contributes to its computational efficiency, with the original implementation demonstrating state-of-the-art performance at the time of its publication on formation energy and bandgap prediction [27]. The model utilizes atomic number as the primary node feature and incorporates interatomic distances as edge features, typically encoded using Gaussian expansion functions. This straightforward representation enables efficient training and prediction while maintaining respectable accuracy across diverse material systems.

ALIGNN: Incorporating Angular Information through Line Graphs

The Atomistic Line Graph Neural Network (ALIGNN) extends beyond pairwise atomic interactions by explicitly modeling three-body terms through angular information [28]. This is achieved through a sophisticated dual-graph architecture where the original atom-bond graph (g) is complemented by its corresponding line graph (L(g)), which represents bonds as nodes and angles as edges [27]. The line graph enables the model to incorporate angle information between adjacent bonds, capturing crucial geometric features of the atomic environment that significantly influence material properties.

This nested graph network strategy allows ALIGNN to learn from both interatomic distances (through the bond graph) and bond angles (through the line graph) [28]. The model composes two edge-gated graph convolution layers—the first applied to the atomistic line graph representing triplet interactions, and the second applied to the atomistic bond graph representing pair interactions [28]. This hierarchical approach provides richer structural representation but comes with increased computational complexity compared to simpler graph architectures [26].

Table: Architectural Comparison Between CGCNN and ALIGNN

| Feature | CGCNN | ALIGNN |

|---|---|---|

| Graph Type | Simple crystal graph | Dual-graph (crystal + line graph) |

| Interactions Modeled | Two-body (pairwise) | Two-body and three-body (angular) |

| Structural Resolution | Atomic positions and bonds | Atoms, bonds, and angles |

| Computational Complexity | Lower | Higher due to nested graph structure |

| Parameter Count | Moderate | Substantially more trainable parameters |

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data and Benchmark Results

Formation Energy and Bandgap Prediction

Quantitative evaluations on standard datasets reveal significant performance differences between CGCNN and ALIGNN architectures. On the Materials Project dataset for formation energy (Ef) prediction, ALIGNN demonstrates superior accuracy with a mean absolute error (MAE) of 0.022 eV/atom compared to CGCNN's 0.083 eV/atom [27]. This substantial improvement highlights the value of incorporating angular information for predicting stability-related properties.

For bandgap prediction (Eg), another critical electronic property, ALIGNN maintains its advantage with an MAE of 0.276 eV compared to CGCNN's 0.384 eV on the same dataset [27]. The sensitivity of electronic properties to precise geometric arrangements makes the angular information captured by ALIGNN particularly valuable for these prediction tasks. The performance gap persists across different dataset versions, with ALIGNN achieving 0.056 eV/atom MAE for formation energy on the updated MP* dataset compared to CGCNN's 0.085 eV/atom [27].

Performance Across Diverse Material Systems

The relative performance of these models extends beyond standard benchmark datasets to specialized material systems. When predicting formation energy in hybrid perovskites—a class of materials with significant technological applications—ALIGNN-based approaches demonstrate particular advantage [27]. Similarly, for total energy predictions, ALIGNN achieves an MAE of 3.706 eV compared to CGCNN's 5.558 eV on the MC3D dataset [27].

Recent advancements have further extended these architectures. The DenseGNN model, which incorporates strategies to overcome oversmoothing in deep GNNs, shows improved performance on several datasets including JARVIS-DFT, Materials Project, and QM9 [26]. Meanwhile, crystal hypergraph convolutional networks (CHGCNN) have been proposed to address representational limitations in traditional graph approaches by incorporating higher-order geometrical information through hyperedges that can represent triplets and local atomic environments [29].

Table: Quantitative Performance Comparison on Standard Benchmarks (MAE)

| Dataset | Property | CGCNN | ALIGNN | Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Project | Formation Energy (Ef) | 0.083 | 0.022 | eV/atom |

| Materials Project | Bandgap (Eg) | 0.384 | 0.276 | eV |

| MP* | Formation Energy (Ef) | 0.085 | 0.056 | eV/atom |

| MP* | Bandgap (Eg) | 0.342 | 0.152 | eV |

| JARVIS-DFT | Formation Energy (Ef) | 0.080 | 0.044 | eV/atom |

| MC3D | Total Energy (E) | 5.558 | 3.706 | eV |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation Methodologies

Graph Construction Protocols

The construction of crystal graphs follows specific protocols that significantly impact model performance. For both CGCNN and ALIGNN, graph construction typically begins with determining atomic connections based on a combination of a maximum distance cutoff (rmax) and a maximum number of neighbors per atom (Nmax) [29]. For each atom, edges connect to its ≤Nmax-th closest neighbors within a spherical shell of radius rmax.

ALIGNN extends this basic construction by creating an additional line graph where nodes represent bonds from the original graph, and edges connect bonds that share a common atom, thereby representing angles [28]. This line graph enables the explicit incorporation of angular information, which is encoded using Gaussian expansion of the angles formed by unit vectors of adjacent bonds [29]. The construction of triplet hyperedges follows a combinatorial pattern where for a node with N bonds, N(N-1)/2 triplets are formed, leading to a quadratic increase in computational complexity [29].

Training Methodologies and Hyperparameters

Standard training protocols for both architectures utilize standardized splits of materials databases with typical distributions of 80% training, 10% validation, and 10% testing [27]. Training involves minimizing mean absolute error (MAE) or mean squared error (MSE) loss functions using Adam or related optimizers with carefully tuned learning rates and batch sizes.

For ALIGNN implementations, the training process involves simultaneous message passing on both the atom-bond graph and the bond-angle line graph [28]. The DGL or PyTorch Geometric frameworks are commonly employed, with training times for ALIGNN typically longer due to the more complex architecture and greater parameter count [26]. Recent implementations have addressed computational challenges through strategies like Dense Connectivity Networks (DCN) and Local Structure Order Parameters Embedding (LOPE), which optimize information flow and reduce required edge connections [26].

Workflow Visualization: From Crystal Structure to Property Prediction

Crystal to Property Prediction Workflow

Architectural Comparison: Message Passing Mechanisms

Message Passing in CGCNN vs. ALIGNN

Table: Key Resources for GNN Implementation in Materials Science

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Solutions | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Materials Databases | Materials Project (MP), JARVIS-DFT, OQMD | Provide structured crystal data with calculated properties for training and validation |

| Graph Construction | Pymatgen, Atomistic Line Graph Constructor | Convert CIF/POSCAR files to graph representations with atomic and bond features |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | PyTorch, PyTorch Geometric, DGL | Provide foundational GNN operations and training utilities |

| Model Architectures | CGCNN, ALIGNN, ALIGNN-FF, DenseGNN | Pre-implemented architectures for various property prediction tasks |

| Feature Encoding | Gaussian Distance Expansion, Angular Fourier Features | Encode continuous distance and angle values as discrete features for neural networks |

| Property Prediction Targets | Formation Energy, Band Gap, Elastic Constants, Phonon Spectra | Key material properties predicted for discovery and screening applications |

The comparison between CGCNN and ALIGNN reveals a fundamental trade-off between computational efficiency and predictive accuracy that researchers must navigate based on their specific applications. CGCNN provides a computationally efficient baseline suitable for high-throughput screening of large materials databases where rapid inference is prioritized. Its architectural simplicity enables faster training and deployment, making it accessible for researchers with limited computational resources.

In contrast, ALIGNN demonstrates superior performance across diverse property prediction tasks, particularly for properties sensitive to angular information such as formation energy and electronic band gaps. The explicit incorporation of three-body interactions through the line graph architecture comes at a computational cost but provides measurable accuracy improvements. For research focused on high-fidelity prediction or investigation of complex material systems, ALIGNN represents the current state-of-the-art.

Future directions in materials informatics point toward increasingly sophisticated representations, including crystal hypergraphs that incorporate higher-order geometrical information [29], universal atomic embeddings that enhance transfer learning [27], and deeper network architectures that overcome traditional limitations like over-smoothing [26]. As these methodologies evolve, the fundamental understanding of how to represent atomic interactions in machine-learning frameworks continues to refine, promising further acceleration in materials discovery and design.

A significant challenge in modern materials science is bridging the gap between computationally designed crystal structures and their actual experimental synthesis. While high-throughput screening and machine learning have identified millions of theoretically promising materials, most remain theoretical constructs because their synthesizability cannot be guaranteed. Traditional screening methods based on thermodynamic stability (e.g., energy above the convex hull) or kinetic stability (e.g., phonon spectra) provide incomplete pictures, as metastable structures can be synthesized and many thermodynamically stable structures remain elusive [2]. This gap represents a critical bottleneck in the materials discovery pipeline. The emergence of Large Language Models (LLMs) specialized for scientific applications offers a transformative approach to this problem. This guide objectively compares the performance of the novel Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models (CSLLM) framework against other computational methods for predicting synthesis feasibility, providing researchers with the experimental data and methodologies needed for informed evaluation.

Performance Comparison: CSLLM vs. Alternative Methods

The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models (CSLLM) framework represents a specialized application of LLMs to materials synthesis problems. It employs three distinct models working in concert: a Synthesizability LLM to determine if a structure can be synthesized, a Method LLM to classify the appropriate synthetic route (e.g., solid-state or solution), and a Precursor LLM to identify suitable starting materials [2] [30].

The following table summarizes the quantitative performance of CSLLM against traditional and alternative computational methods for synthesizability assessment.

Table 1: Performance comparison of synthesizability prediction methods

| Prediction Method | Reported Accuracy | Key Metric | Dataset Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSLLM (Synthesizability LLM) | 98.6% [2] [30] | Classification Accuracy | 150,120 structures [2] |

| Traditional Thermodynamic | 74.1% [2] | Classification Accuracy | Not Specified |

| Traditional Kinetic (Phonon) | 82.2% [2] | Classification Accuracy | Not Specified |

| Teacher-Student Neural Network | 92.9% [2] | Classification Accuracy | Not Specified |

| Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning | 87.9% [2] | Classification Accuracy | Not Specified |

| CSLLM (Method LLM) | 91.0% [2] [30] | Classification Accuracy | 150,120 structures [2] |

| CSLLM (Precursor LLM) | 80.2% [2] [30] | Prediction Success | Binary/Ternary compounds [2] |

| Bayesian Neural Network (Organic Rxn.) | 89.48% [5] | Feasibility Prediction Accuracy | 11,669 reactions [5] |

The performance data clearly demonstrates CSLLM's significant advance in accuracy for crystal synthesizability classification, outperforming traditional stability-based methods by over 20 percentage points and previous machine learning approaches by at least 5.7 percentage points [2]. Its high accuracy in also predicting synthesis methods and precursors makes it a uniquely comprehensive tool.

For context in other domains, a Bayesian Neural Network model for predicting organic reaction feasibility achieved 89.48% accuracy on an extensive high-throughput dataset of acid-amine coupling reactions, which, while impressive, remains below CSLLM's performance for crystals [5].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

CSLLM Dataset Construction and Model Training

A key factor in CSLLM's performance is its robust dataset and tailored training methodology, detailed in Nature Communications [2].

- Dataset Curation: The training relied on a balanced dataset of 150,120 crystal structures. Positive (synthesizable) examples were 70,120 ordered crystal structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD). Negative (non-synthesizable) examples were 80,000 theoretical structures with the lowest CLscores (a synthesizability metric from a pre-trained Positive-Unlabeled learning model) from a pool of over 1.4 million candidates [2].

- Text Representation - "Material String": To fine-tune LLMs effectively, the researchers developed a concise text representation for crystals. This "material string" format

SP | a, b, c, α, β, γ | (AS1-WS1[WP1), ...efficiently encodes space group (SP), lattice parameters, and atomic species (AS), Wyckoff species (WS), and Wyckoff positions (WP), avoiding the redundancy of CIF or POSCAR files [2]. - Model Fine-tuning: The framework utilizes three separate LLMs, each fine-tuned on the comprehensive dataset using the material string representation to specialize in synthesizability classification, synthetic method classification, and precursor prediction, respectively [2].

Benchmarking Protocol

The benchmarking compared CSLLM against established methods. The traditional thermodynamic approach classified a structure as synthesizable if its energy above the convex hull was ≥0.1 eV/atom. The kinetic approach used phonon spectrum analysis, classifying a structure as synthesizable if its lowest phonon frequency was ≥ -0.1 THz. CSLLM's performance was evaluated on held-out test data from its curated dataset [2].

The CSLLM Framework Workflow

The following diagram visualizes the end-to-end workflow of the CSLLM framework, from data preparation to final prediction.

Diagram 1: The CSLLM prediction workflow. The process begins with converting an input crystal structure into a "material string" representation. The framework then uses three fine-tuned LLMs to sequentially assess synthesizability, classify the synthetic method, and predict suitable precursors.

The Researcher's Toolkit for CSLLM

To understand, utilize, or build upon a framework like CSLLM, researchers require a specific set of computational and data resources.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and tools for CSLLM-based research

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|