Beyond the Filter: Understanding the Critical Limitations of Forward Screening in Modern Materials Discovery

Forward screening, the long-standing paradigm of filtering pre-defined material candidates against target properties, faces fundamental challenges in the era of vast chemical spaces and AI-driven design.

Beyond the Filter: Understanding the Critical Limitations of Forward Screening in Modern Materials Discovery

Abstract

Forward screening, the long-standing paradigm of filtering pre-defined material candidates against target properties, faces fundamental challenges in the era of vast chemical spaces and AI-driven design. This article systematically explores the limitations of forward screening, from its inherent lack of exploration and severe class imbalance to critical data leakage and validation pitfalls. We detail methodological shortcomings, discuss optimization strategies, and provide a framework for rigorous, comparative model validation. Aimed at researchers and development professionals, this review synthesizes why a paradigm shift towards inverse design is underway and how to navigate the transition for accelerated materials and drug discovery.

The Inherent Ceiling of Forward Screening: Why Trial-and-Error Hits a Wall

Forward screening represents a fundamental and widely adopted methodology in computational materials science. It operates on a straightforward, sequential principle: evaluate a predefined set of material candidates against specific property criteria to identify those worthy of further investigation [1]. This paradigm is inherently a "forward" process, moving from a known set of candidates toward a filtered subset that meets desired targets. In the broader context of materials discovery, this approach stands in direct contrast to the emerging inverse design paradigm, which starts with desired properties and works backward to compute candidate structures [1]. Despite its limitations, forward screening remains a cornerstone technique due to its systematic nature and compatibility with high-throughput computational frameworks.

The Fundamental Workflow of Forward Screening

The forward screening process follows a rigorous, sequential pathway designed to efficiently narrow large material databases into promising candidates. The entire workflow functions as a one-way filtration system, progressively applying more computationally intensive evaluation methods to an increasingly selective pool of materials.

The workflow begins with clearly defined target properties based on application requirements, such as thermodynamic stability, electronic band gap, or thermal conductivity [1]. Researchers then gather a comprehensive set of candidate materials from open-source databases like the Materials Project or AFLOW [1]. The initial screening phase typically employs machine learning surrogate models to rapidly predict properties, filtering out obviously unsuitable candidates with minimal computational cost [1]. Promising materials from this initial filter proceed to high-fidelity computational evaluation using first-principles methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT) for accurate property verification [1]. Finally, the most promising candidates undergo experimental validation to confirm predicted properties and assess synthesizability.

Quantitative Performance and Applications

Forward screening has been systematically applied across diverse material classes and property targets. The table below summarizes key performance metrics and applications documented in research literature.

Table 1: Documented Applications and Performance of Forward Screening

| Material Class | Target Properties | Screening Scale | Reported Success Rate | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk Crystals [1] | Thermodynamic stability | Hundreds of thousands of compounds | Very low (precise value not specified) | Identifies stable compounds via energy above convex hull |

| Optoelectronic Semiconductors [1] | Electronic band gap, absorption | Large databases | Very low | Discovers light absorbers, transparent conductors, LED materials |

| Thermal Management Materials [1] | Thermal conductivity | Focused libraries (e.g., Half-Heuslers) | Very low | Identifies materials with extremely low thermal conductivity |

| 2D Ferromagnetic Materials [1] | Curie temperature, magnetic moments | 2D material databases | Very low | Discovers materials with Curie temperature > 400 K |

The consistently low success rates across applications highlight a fundamental characteristic of forward screening: the severe class imbalance in materials space, where only a tiny fraction of candidates exhibit desirable properties [1]. This inefficiency stems from the paradigm's fundamental structure as a filtration process rather than a generative one.

Essential Methodologies and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of forward screening requires specialized computational tools and well-defined evaluation methodologies. The field has developed robust frameworks to standardize this process across different material classes.

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Thermodynamic Stability Screening

- Objective: Identify synthesizable compounds by evaluating thermodynamic stability [1].

- Procedure: Calculate the "energy above convex hull" (Ehull) for each candidate using DFT. Materials with Ehull ≤ 50 meV/atom are typically considered potentially stable [1].

- Validation: Perform phonon dispersion calculations to confirm dynamic stability (absence of imaginary frequencies) [1].

- Tools: AFLOW, Materials Project, and other high-throughput DFT frameworks [1].

Protocol 2: Electronic Property Evaluation for Optoelectronics

- Objective: Discover materials with suitable electronic properties for specific applications [1].

- Procedure: Compute electronic band structure using DFT with hybrid functionals (e.g., HSE06) for accurate band gaps. For photovoltaic applications, screen for band gaps between 1.0-2.0 eV and strong optical absorption [1].

- Validation: Compare computational predictions with experimental measurements where available.

- Tools: Atomate workflows for automated DFT calculation management [1].

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Forward Screening

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| AFLOW [1] | Software Framework | High-throughput DFT calculations | Automated calculation workflows, property databases |

| Atomate [1] | Software Framework | Materials analysis workflows | Streamlines data preparation, DFT calculations, post-analysis |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [1] | Machine Learning Model | Property prediction | Represents atomic structures as graphs for accurate prediction |

| Materials Project [1] | Database & Tools | Candidate material source | Contains calculated properties for over 100,000 materials |

Fundamental Limitations and Inefficiencies

Despite its widespread adoption, the forward screening paradigm faces several inherent limitations that constrain its effectiveness in materials discovery.

Structural Limitations of the Paradigm

The lack of exploration capability represents the most significant constraint of forward screening. The paradigm operates exclusively as a filtration system on existing databases, fundamentally incapable of generating or discovering materials outside predetermined chemical spaces [1]. This restriction to known data distributions prevents the discovery of novel materials with properties that deviate from established trends [1].

The severe class imbalance in materials space means the vast majority of computational resources are wasted evaluating candidates that ultimately fail screening criteria [1]. With success rates typically below 1% for many applications, this inefficiency creates substantial computational bottlenecks [1].

Forward screening represents a systematic, well-established approach to materials discovery that has enabled significant advances across multiple domains. Its structured workflow, supported by sophisticated computational tools and standardized protocols, provides a reliable method for identifying promising candidates from existing databases. However, its fundamental limitations—particularly its inability to explore beyond known chemical spaces and its inherent inefficiency due to severe class imbalance—highlight the need for complementary approaches like inverse design [1]. As the field evolves, the forward screening paradigm will likely continue to serve as an important component within a more diverse toolkit of discovery methodologies rather than as a standalone solution.

In materials discovery research, the exploration bottleneck refers to the fundamental limitation that prevents scientists from efficiently searching vast, unexplored chemical spaces to identify novel compounds. This bottleneck arises from a heavy reliance on existing experimental data and known chemical structures, which constrains computational and experimental models to familiar territories. Within the context of forward screening—a hypothesis-generating approach that begins with large-scale experimental perturbation to identify candidates of interest—this bottleneck is particularly pronounced. The process is often limited by its dependence on known data distributions for training predictive models and guiding experimental campaigns, making it challenging to venture into genuinely novel compositional or structural spaces [2] [3]. The inability to escape these known distributions significantly impedes the discovery of materials with truly disruptive properties, as the search algorithms and human intuition alike are biased toward minor variations of established systems.

The core of the problem lies in the fact that while advanced computational tools, including AI and machine learning, can rapidly predict thousands of candidate materials with desired properties, the subsequent steps of synthesis and validation often fail for candidates that fall outside the well-documented regions of chemical space [2]. This creates a critical path dependency where the initial selection of candidates, guided by historical data, determines and limits the final outcomes. For forward genetic screens in biological research, a similar challenge exists: mutants with strong phenotypes in previously characterized genes are easier to detect, while novel genes, particularly those with weak or redundant functions, are often missed because the screening process itself is tuned to recognize patterns observed in past experiments [4]. This document explores the manifestations, underlying causes, and emerging solutions to this bottleneck, providing a technical guide for researchers aiming to overcome these fundamental limitations.

Quantitative Evidence of the Bottleneck

The exploration bottleneck is not merely a theoretical concern but is substantiated by quantitative data from various stages of the discovery pipeline. The disparity between computational prediction and experimental realization, the narrowing scope of synthetic exploration, and the economic constraints of high-throughput experimentation all provide measurable evidence of this challenge.

Table 1: Quantitative Evidence of the Exploration Bottleneck in Materials Discovery

| Metric | Value / Finding | Implication | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational-Experimental Gap | ~200,000 entries in computational databases (e.g., Materials Project) vs. few computationally designed & validated materials | Vast computational spaces are not translated into tangible materials, highlighting a synthesis bottleneck. | [2] |

| Synthesis Pathway Narrowing | 144 of 164 recipes for barium titanate (BaTiO₃) use the same precursors (BaCO₃ + TiO₂) | Human bias and convention drastically limit the exploration of alternative, potentially superior synthesis pathways. | [2] |

| High-Throughput Experimentation Scale | Testing binary reactions between 1,000 compounds would require ~500,000 experiments | The combinatorial explosion of possible reactions makes exhaustive experimental screening intractable. | [2] |

| Identification of Novel Genetic Factors | Strategy emphasizes selection of weak mutants to find genes with functional redundancy | Strong phenotypes are easier to detect but often point to previously characterized genes, while novel factors require more nuanced screening. | [4] |

| AI-Driven Throughput Increase | Autonomous robotic testing framework enables a 20x throughput increase in materials synthesis and characterization | Advanced automation can alleviate the bottleneck by accelerating the "make-measure" cycle, allowing exploration of more candidates. | [5] |

The data reveals a multi-faceted problem. The sheer scale of theoretical possibility, as exemplified by the half-million experiments needed for a limited binary reaction screen, makes comprehensive exploration economically unfeasible [2]. Consequently, research practices converge on a narrow subset of known and trusted synthetic pathways, which in turn biases the resulting data and reinforces the existing data distribution. This creates a feedback loop that is difficult to break. In forward genetic screens, the explicit strategy of targeting weak phenotypes acknowledges that the most obvious, strong phenotypes have likely already been mapped to known genes, leaving the novel, functionally redundant factors in the unexplored data space [4].

Case Studies: The Bottleneck in Practice

Materials Synthesis: The Thermodynamic Stability vs. Synthesizability Dilemma

A quintessential example from materials science is the challenge of synthesizing theoretically predicted compounds. AI models like Microsoft's MatterGen can generate novel, thermodynamically stable structures. However, thermodynamic stability does not equate to synthesizability [2]. Synthesis is a pathway problem, akin to finding a mountain pass rather than attempting a direct climb over the peak. The desired material may be stable, but if competing phases are kinetically favorable to form, the synthesis will be plagued by impurities.

- Case: Bismuth Ferrite (BiFeO₃): A promising multiferroic material, its synthesis is notoriously difficult because attempts most often result in impurities like Bi₂Fe₄O₉ or Bi₂₅FeO₃₉. This occurs due to a narrow window of thermodynamic stability and the kinetic favorability of these competing phases [2].

- Case: LLZO Solid Electrolyte: The synthesis of Li₇La₃Zr₂O₁₂ for solid-state batteries requires high temperatures (~1000 °C), which volatilizes lithium and promotes the formation of the impurity La₂Zr₂O₇ [2].

These cases illustrate that without a viable, low-energy barrier synthesis pathway—which often lies outside the conventional recipes documented in literature—a predicted material remains an abstract entity. The exploration bottleneck here is the lack of data and models that can reliably predict not just stability, but also viable kinetic synthesis routes.

Forward Genetic Screening: The Bias Toward Known Strong Phenotypes

In biological discovery, forward genetic screening in model organisms like C. elegans faces a parallel bottleneck. The standard approach involves mutagenesis followed by screening for mutants with a phenotype of interest. The bottleneck arises because mutants with strong, easily detectable phenotypes are often the first to be isolated and are frequently mapped to the same set of known genes. This leaves a wealth of novel genes, particularly those with subtle or redundant functions, undetected in the vast space of possible mutations [4].

A developed protocol to overcome this specifically instructs researchers to "Selection of weak mutants can help to identify genes with functional redundancy" [4]. This is a deliberate strategy to escape the known data distribution of strong phenotypes. The protocol further incorporates whole-genome sequencing of isolated mutants early in the process to exclude those with lesions in previously characterized genes, thereby saving time and labor and focusing efforts on mapping truly novel causal mutations [4]. This methodological adjustment is a direct response to the exploration bottleneck in genetic research.

AI in Reinforcement Learning: The Sparse Reward Problem

The exploration bottleneck is also a recognized challenge in the AI domain, particularly in Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Reward (RLVR) used for post-training large language models (LLMs). When an LLM is tasked with solving hard reasoning problems (e.g., complex math questions), the vast solution space leads to low initial accuracy. This results in sparse rewards, where the model rarely receives positive feedback, creating an exploration bottleneck that hinders learning [6].

The proposed solution, EvoCoT, uses a self-evolving curriculum. It first constrains the exploration space by having the LLM generate reasoning paths guided by known answers. Then, it progressively shortens these provided reasoning steps, gradually expanding the space the model must explore on its own [6]. This controlled expansion of the problem space allows the model to stably learn from problems that were initially unsolvable, effectively overcoming the exploration bottleneck by not starting from a state of maximal uncertainty.

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols to Overcome the Bottleneck

Protocol for a Forward Genetic Screen Designed to Identify Novel Factors

This protocol is designed to mitigate the bias toward known genes by intentionally targeting weak phenotypes and incorporating early genomic exclusion.

1. Mutagenesis and Screening - Mutagenesis: Synchronized L4 or young-adult C. elegans hermaphrodites are treated with 50 mM Ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS) in M9 buffer for 4 hours at 20-25°C with constant rotation. EMS is a potent mutagen that introduces point mutations randomly across the genome [4]. - Screening: After mutagenesis, F1 progeny are allowed to self-reproduce. The F2 or later generations are screened for the phenotype of interest. Critically, the protocol emphasizes setting up screens to identify mutant animals with a weak phenotype, as these are more likely to represent novel genes with redundant functions. It is recommended to select only one mutant from each F1 plate to ensure independence of mutations [4].

2. Genomic DNA Extraction and Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) - DNA Extraction: Mutant strains are grown to starvation, and worms are collected and lysed using a lysis buffer with Proteinase K. Genomic DNA is isolated using a commercial kit (e.g., QIAGEN DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit) [4]. - WGS and Analysis: The purpose of initial sequencing is to "exclude mutants of previously characterized genes from crosses for mapping" [4]. By comparing the list of known genes associated with the phenotype against the EMS-induced variants found in the mutant, researchers can rapidly discard mutants in previously identified genes, thus focusing resources on mapping mutations in novel genes.

3. Mapping Causal Mutations - Mutants that pass the WGS exclusion step are backcrossed to eliminate background mutations. The causal mutation is then mapped by detecting EMS-induced variants linked to the phenotype after backcrossing [4].

The AI-Enabled "Predict-Make-Measure" Cycle for Targeted Materials Discovery

This methodology, as employed by Johns Hopkins APL, integrates AI throughout the discovery process to break the cycle of limited exploration.

- Predict: A novel AI architecture is used to explore the massive space of element combinations and structures, targeting specific desired properties (e.g., high-temperature stability). The models are trained on data from quantum mechanical simulations (e.g., density functional theory) and existing experimental data. This step narrows the search from millions of possibilities to a more manageable set of promising candidates [5].

- Make: High-throughput and autonomous synthesis methods are critical. One approach uses blown powder directed energy deposition, an additive manufacturing technique that allows for the fabrication of hundreds of unique samples with variations in composition and processing on a single build plate. This dramatically accelerates the synthesis step, which is a major bottleneck in traditional research [5].

- Measure: Autonomous characterization is key. A system using an instrumented robotic arm, sometimes equipped with a laser to heat samples, autonomously tests the mechanical properties of the synthesized samples under extreme conditions. This robotic system can perform testing up to five times faster than standard approaches [5].

- Iterate: The data from the "Measure" step is fed back into the AI models for Bayesian optimization, which suggests the next set of promising candidates and parameters. This closed-loop process continuously refines the search, learning from both success and failure to explore the chemical space more effectively [5].

The EvoCoT Framework for Curriculum Learning in AI

The EvoCoT framework provides a structured protocol for overcoming exploration bottlenecks in AI training by gradually increasing task difficulty.

- Stage 1: Answer-Guided Reasoning Path Self-Generation: The LLM is provided with problems and their final answers. Its task is to generate a Chain-of-Thought (CoT) explanation that reconstructs the reasoning path to the answer. These self-generated CoTs are then filtered and verified for logical consistency. This stage transforms outcome-supervised data into step-by-step reasoning trajectories without requiring external supervision [6].

- Stage 2: Step-Wise Curriculum Learning: The complete CoT trajectories from Stage 1 are progressively shortened by removing thinking steps in reverse order. This creates a curriculum of problems with increasing difficulty. The LLM starts by completing very short reasoning paths and, as it masters each level, the paths are lengthened, forcing the model to explore a gradually expanding reasoning space. This controlled expansion prevents the model from being overwhelmed by the vast solution space from the outset [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Featured Experiments

| Item | Function / Explanation | Example Experiment / Context |

|---|---|---|

| Ethyl Methanesulfonate (EMS) | A potent chemical mutagen that introduces random point mutations across the genome, creating a library of genetic variants for forward screening. | Forward Genetic Screening [4] |

| DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit | A commercial kit for the rapid and efficient purification of high-quality genomic DNA from tissue samples, essential for downstream sequencing. | Genomic DNA Extraction [4] |

| Blown Powder Directed Energy Deposition | An additive manufacturing process used to fabricate hundreds of unique material samples (with varied composition/processing) on a single build plate. | High-Throughput Materials Synthesis [5] |

| Instrumented Robotic Arm with Laser | An automated system for high-throughput mechanical and property testing of material samples, capable of applying in-situ heating via laser. | Autonomous Materials Characterization [5] |

| Bayesian Optimization Model | A machine learning model that uses the results from prior experiments to suggest the most promising candidates and parameters for the next iteration. | AI-Driven Materials Discovery [5] |

The exploration bottleneck, defined by the inability to escape known data distributions, is a pervasive limitation in forward screening across materials discovery and biological research. It is rooted in combinatorial complexity, human and algorithmic bias toward known successful patterns, and the high cost of experimentation. However, as detailed in this guide, emerging methodologies are providing a path forward. The integration of AI throughout the predict-make-measure cycle, the design of experiments that explicitly target weak signals and exclude known outcomes, and the implementation of self-evolving curriculum learning frameworks represent a paradigm shift. These approaches do not eliminate the fundamental challenge of vast search spaces but provide a structured and intelligent means to navigate them, ultimately enabling researchers to move beyond incremental discoveries and into genuinely novel territories.

The discovery of new functional materials and drug molecules is fundamentally hampered by a "needle-in-a-haystack" problem of extraordinary proportions. Chemical space—the set of all possible small organic molecules—is estimated to encompass approximately 10^60 candidates [7]. This vastness presents an almost inconceivable search challenge: finding a specific molecule with target properties requires locating one candidate among 10^60 possibilities, a feat comparable to finding a single specific grain of sand among all the beaches and deserts on Earth [7].

Traditional computational approaches, particularly forward screening methods, attempt to address this challenge by systematically evaluating predefined sets of candidates against target property criteria [1]. This paradigm, while methodical, operates within a framework inherently limited by the severe class imbalance between desirable and undesirable candidates. With only a tiny fraction of molecules exhibiting targeted properties, forward screening methods expend substantial computational resources evaluating candidates that ultimately fail, resulting in exceptionally low success rates [1]. This review examines the fundamental limitations of forward screening in addressing severe class imbalance and explores emerging paradigms that offer more efficient navigation of chemical space.

The Forward Screening Paradigm and Its Fundamental Limitations

The Forward Screening Workflow

Forward screening operates on a sequential "generate-and-filter" principle [1]. The typical workflow, illustrated below, begins with assembling a library of candidate materials, often sourced from existing databases. Property thresholds based on application requirements are established, and these thresholds act as sequential filters to eliminate non-conforming candidates. First-principles computational methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT) conventionally evaluate materials properties, though machine learning surrogate models are increasingly employed to reduce computational costs [1].

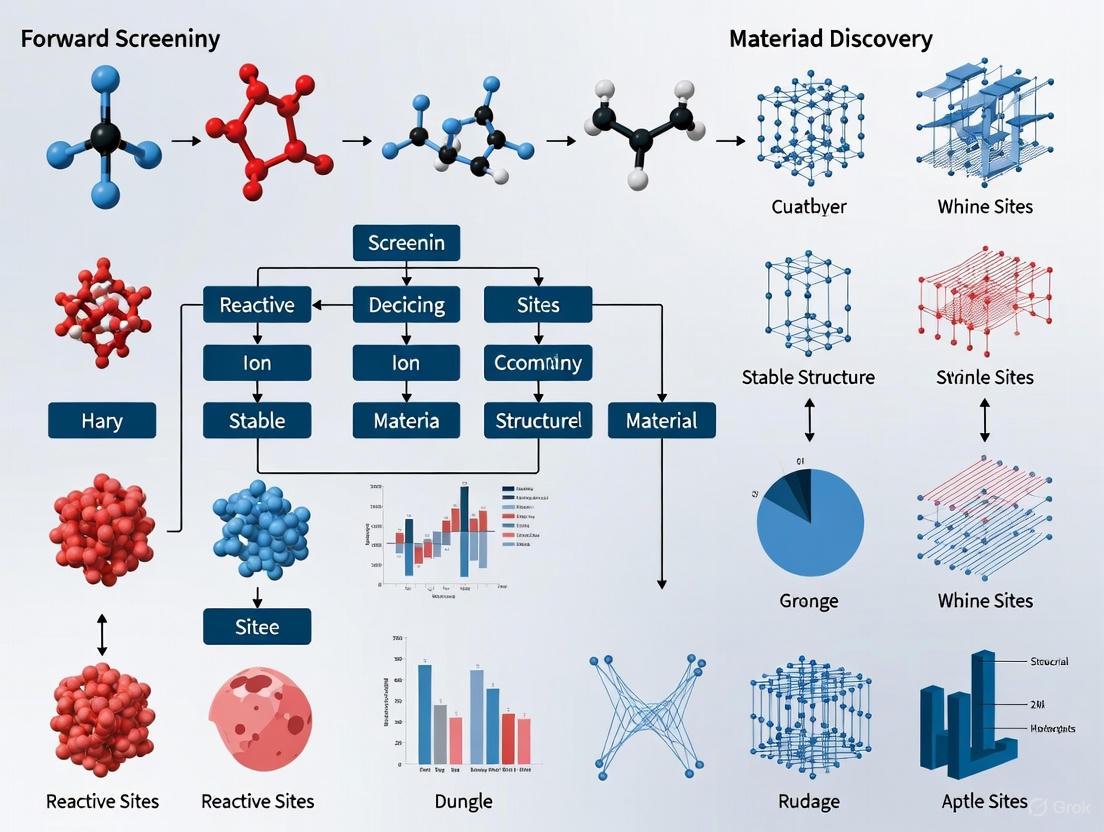

Figure 1: The conventional forward screening workflow for materials discovery. This sequential filtering approach systematically reduces candidate pools but faces fundamental efficiency limitations.

Quantitative Limitations in Chemical Space Exploration

The efficiency challenge of forward screening becomes quantitatively apparent when examining the scale of chemical space against practical screening capabilities. The following table illustrates the staggering imbalance between search space size and practical screening capacity:

Table 1: Chemical Space Exploration Scale and Methods

| Parameter | Scale/Method | Implication for Forward Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Total Chemical Space | ~10^60 possible small organic molecules [7] | Impossible to screen exhaustively |

| Typical Screening Subset | 10^3-10^6 molecules [7] | <0.000000000000000000000000000000001% of space explored |

| Screening Success Rate | Very low due to class imbalance [1] | Majority of computational resources spent on unsuccessful candidates |

| Alternative: Genetic Algorithms | 100-several million evaluations to find target [7] | Still tiny fraction of total space but more efficient than random screening |

| Alternative: Inverse Design | ~8% of materials design literature (growing) [1] | Paradigm shift from screening to generation |

Fundamental Limitations of Forward Screening

Forward screening faces several interconnected limitations when addressing severe class imbalance in chemical spaces:

Lack of Extrapolation Capability: Forward screening operates as a one-way process that applies selection criteria to existing databases without the capability to extrapolate beyond known data distributions [1]. This fundamentally constrains its ability to discover truly novel materials with properties beyond existing trends.

Severe Class Imbalance: The ratio of desirable to undesirable candidates in chemical space is exceptionally skewed [1]. Consequently, the vast majority of computational resources are spent evaluating materials that fail to meet target criteria, resulting in inefficient resource allocation.

Combinatorial Explosion: The number of possible molecular structures grows exponentially with molecular size and complexity [1]. Forward screening methods cannot overcome this combinatorial limitation through incremental improvements alone.

Path Dependency Ignorance: Effective navigation of chemical space requires following paths of incremental improvement, where each step maintains or enhances target properties [7]. Forward screening evaluates candidates in isolation without exploiting these connectivity relationships.

Why Search Algorithms Can Find Needles in Haystacks

The Path Connectivity Principle

The remarkable ability of search algorithms to locate specific molecules in vast chemical spaces despite screening only tiny subsets can be explained by the path connectivity principle. Rather than consisting of uniformly distributed, isolated points, chemical space contains an enormous number of interconnected paths that connect low-scoring molecules to high-scoring targets [7]. A path is defined as a series of molecules with non-zero quantifiable similarity to the target, where each successive molecule becomes increasingly similar [7].

The probability of randomly encountering a molecule on one of these paths is surprisingly high. For example, in a Shakespearean text search analogy (searching for the specific phrase "to be or not to be" among 6.7×10^55 possible 39-character sequences), 77% of random sequences share at least one correctly placed character with the target [7]. This high connectivity probability means search algorithms are likely to initially find molecules on productive paths, then follow these paths to the target.

Minimum Path Length in Chemical Space

The minimum path length from any point in chemical space to a specific target molecule is on the order of 100 steps, where each step represents a change of an atom- or bond-type [7]. This path length represents the theoretical minimum for a perfect search algorithm. In practice, genetic algorithms typically require screening between 100 and several million molecules to locate targets, depending on the specificity of the target property, molecular representation, and the number of viable solutions [7].

The Role of Smooth Fitness Landscapes

Search algorithm efficiency depends critically on the "smoothness" of the fitness landscape—how incrementally the score or property similarity changes with molecular modifications [7]. When similarity scores increase gradually with appropriate modifications (continuous score improvement), algorithms can efficiently follow paths toward targets. However, when scores change discontinuously (improving only after several combined modifications), search efficiency decreases dramatically [7].

Beyond Forward Screening: Inverse Design and Evolutionary Approaches

Genetic Algorithms for Chemical Space Exploration

Genetic algorithms (GAs) provide a powerful alternative to forward screening by mimicking natural selection principles [7] [1]. In chemical GAs, molecules undergo selection, mating, and mutation operations guided by fitness functions quantifying target property optimization. The following workflow illustrates a typical GA approach for molecular discovery:

Figure 2: Genetic algorithm workflow for molecular discovery. This evolutionary approach efficiently navigates chemical space by exploiting incremental improvements along connected molecular paths.

Experimental Protocol for Genetic Algorithm Molecular Search

The following detailed methodology outlines a typical GA approach for molecular rediscovery (locating predefined target molecules), based on established protocols in the literature [7]:

Table 2: Genetic Algorithm Implementation Protocol

| Component | Implementation Details | Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Representation | Graph-based or string-based (SMILES, DeepSMILES, SELFIES) | String-based GA uses character-level operations |

| Initialization | 100-500 randomly generated molecules | Population diversity critical for exploration |

| Fitness Evaluation | Tanimoto similarity based on ECFP4 circular fingerprints [7] | Range: 0 (no similarity) to 1 (identical) |

| Selection | Roulette wheel selection with elitism | Elitism preserves top performers between generations |

| Crossover | Random cut-point recombination of parent strings | 50 attempts maximum for valid offspring |

| Mutation | Character replacement in string representations | 20-50% mutation rate; 50 validity attempts |

| Termination | Target similarity reached or generation limit | Typically 300-1000 generations |

Fitness Computation Details:

- Tanimoto similarity computed using RDKit based on ECFP4 circular fingerprints [7]

- For photophysical properties: First excitation energy and oscillator strength computed using semiempirical sTDA-xTB method [7]

- Geometry optimization: Twenty random conformations generated and energy-minimized using MMFF94, lowest energy conformation selected [7]

Validation Procedures:

- Invalid molecules (according to RDKit) rejected during operations

- Aromaticity maintained (Kekulized) during operations to increase validity probability

- Molecular representations not re-canonicalized after mating and mutation operations

The Inverse Design Paradigm

Inverse design represents a fundamental paradigm shift from forward screening. Rather than generating candidates then evaluating properties, inverse design starts with target properties and works backward to identify corresponding molecular structures [1]. This approach has grown to constitute approximately 8% of the materials design literature, indicating a significant methodological shift [1].

Advanced inverse design implementations now employ deep generative models including variational autoencoders (VAEs), generative adversarial networks (GANs), and diffusion models [1]. These models learn intricate structure-property relationships and can directly generate novel material candidates conditioned on target properties, effectively addressing the class imbalance problem by focusing generative capacity on relevant regions of chemical space.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Chemical Space Exploration

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Algorithm Frameworks | Graph-based GA [7], String-based GA | Evolutionary search for molecular optimization |

| Molecular Representations | SMILES, DeepSMILES, SELFIES [7] | String-based encoding of molecular structure |

| Fingerprinting Methods | ECFP4 Circular Fingerprints [7] | Molecular similarity computation for fitness evaluation |

| Quantum Chemistry Calculators | sTDA-xTB [7], DFT | Excitation energy and property computation |

| Geometry Optimization | MMFF94 [7] | Molecular conformation search and energy minimization |

| Cheminformatics Toolkits | RDKit [7] | Molecular validation, manipulation, and descriptor calculation |

| High-Throughput Frameworks | Atomate [1], AFLOW [1] | Automated computational materials screening |

| Inverse Design Models | VAEs, GANs, Diffusion Models [1] | Property-conditioned molecular generation |

The severe class imbalance in chemical space presents a fundamental challenge to traditional forward screening approaches in materials discovery. The inefficiency of these methods stems from their inability to overcome the combinatorial explosion of molecular possibilities and their failure to exploit the connected path structure of chemical space. Evolutionary algorithms and inverse design methodologies represent more efficient paradigms that directly address the "needle-in-a-haystack" problem by leveraging incremental improvement pathways and property-conditioned generation. As these approaches continue to mature, integrating physical knowledge with data-driven models and emphasizing experimental validation, they hold significant promise for accelerating the discovery of novel functional materials and pharmaceutical compounds.

The pursuit of new materials and compounds with tailored properties represents a critical frontier across scientific disciplines, from pharmaceutical development to renewable energy technologies. Historically, this discovery process has been dominated by the forward screening paradigm, a systematic but often resource-intensive approach where researchers synthesize or select numerous candidate materials and experimentally test them to identify those matching desired properties [8]. While this method has yielded significant successes, it operates as a "needle-in-a-haystack" search through vast chemical spaces, making it inherently limited by time, cost, and practical constraints. In recent years, advances in computational power and artificial intelligence have catalyzed the emergence of inverse design, a fundamentally reversed paradigm where researchers begin by defining target properties and employ algorithms to identify the optimal material or molecular structure that fulfills these specifications [9] [8]. This paradigm shift from "properties-from-materials" to "materials-from-properties" represents a transformative approach to scientific discovery, promising to accelerate development cycles and uncover novel solutions that might otherwise remain hidden within unexplored regions of chemical space.

The core distinction between these paradigms lies in their fundamental starting point and workflow direction. Forward screening follows a materials-to-properties pathway, evaluating multiple candidates to determine which best matches target properties [10]. In contrast, inverse design implements a properties-to-materials pathway, where target properties serve as input to computational models that directly generate candidate materials possessing these characteristics [8]. This contrast is not merely procedural but represents a deeper philosophical divergence in how we approach scientific discovery—from Edisonian trial-and-error toward a principled, prediction-driven methodology.

Defining the Paradigms: Core Principles and Workflows

Forward Screening: The Traditional Workhorse

Forward screening, also known as forward genetics in biological contexts, is a phenotype-driven approach that begins with generating random mutations in a model organism or creating diverse material libraries, followed by systematic screening to identify mutants or materials exhibiting a phenotype or property of interest [11]. The strength of this approach lies in its lack of presupposition about which genes or material components are important, allowing for the discovery of entirely novel factors and mechanisms. In practice, forward screening follows a well-established workflow with distinct stages:

Table 1: Key Stages in Forward Screening Protocols

| Stage | Description | Common Techniques/Materials |

|---|---|---|

| Mutagenesis/Library Generation | Introduction of random variations or creation of diverse candidates | ENU (N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea) treatment [11], combinatorial synthesis, high-throughput experimentation |

| Phenotypic Screening | Systematic assessment for desired traits or properties | Automated property measurement, biological assays, optical/electrical characterization |

| Identification & Validation | Isolation and confirmation of hits | Backcrossing [12], dose-response studies, control experiments |

| Causal Mapping | Identification of genetic or compositional basis | Positional cloning, whole-genome sequencing, compositional analysis [11] |

The following diagram illustrates the sequential, iterative nature of the forward screening workflow:

Inverse Design: The Computational Paradigm Shift

Inverse design represents a fundamentally different approach that frames materials discovery as an optimization problem. Rather than testing numerous candidates, inverse design starts with the desired functionality and employs computational methods to identify the material or structure that satisfies these requirements [8] [13]. This paradigm leverages the understanding that material properties are controlled by atomic constituents (A), composition (C), and structure (S)—collectively termed the "ACS" framework [8]. The power of inverse design lies in its ability to navigate this ACS space efficiently through computational means rather than physical experimentation.

Three distinct modalities of inverse design have emerged, each suited to different discovery contexts [8]:

Modality 1: Applied to single material systems with vast configuration possibilities, such as superlattices or nanostructures, where properties like band gaps or Curie temperatures can be calculated for assumed configurations.

Modality 2: Focused on identifying new chemical compounds in equilibrium (ground state structures) with desired target properties from the vast space of possible elemental combinations.

Modality 3: Concerned with optimizing processing conditions and external parameters (temperature, pressure, etc.) to achieve materials with specific functional characteristics.

The following diagram illustrates the core inverse design workflow, highlighting its data-driven, iterative optimization nature:

Quantitative Comparison: Performance and Efficiency Metrics

Direct, quantitative comparisons between forward and inverse design paradigms reveal significant differences in their efficiency, success rates, and computational requirements. A case study on refractory high-entropy alloys directly compared these approaches, demonstrating their relative strengths and limitations in practical applications [10].

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Forward Screening vs. Inverse Design for Materials Discovery

| Parameter | Forward Screening | Inverse Design |

|---|---|---|

| Discovery Efficiency | Requires evaluating numerous candidates; Limited by experimental throughput | Direct identification of optimal candidates; Dramatically reduces number of experiments needed [8] |

| Exploration Capability | Limited to experimentally tractable candidate libraries | Can explore "missing" compounds not yet synthesized [8] and vast configuration spaces [8] |

| Success Rate | Dependent on library diversity and screening quality | High accuracy demonstrated (e.g., 99% composition accuracy, 85% DOS pattern accuracy) [9] |

| Resource Requirements | High experimental costs, time-intensive | High computational costs, specialized expertise needed |

| Novelty of Findings | Can discover unexpected relationships through screening | Can propose novel materials with no natural analogues (e.g., Mo₃Co for hydrogen storage) [9] |

| Handling Complexity | Struggles with high-dimensional property spaces | Can handle multidimensional properties (e.g., electronic density of states) [9] |

Limitations of Forward Screening in Modern Materials Discovery

Despite its historical contributions and ongoing utility, forward screening faces fundamental limitations in the context of contemporary materials science challenges, particularly when compared to the capabilities of inverse design approaches.

Combinatorial Explosion in Chemical Space

The most significant limitation of forward screening emerges from the vastness of chemical space. For example, the number of possible atomic configurations in simple two-component A/B superlattices is astronomic [8], and the space of possible organic molecules far exceeds what could be synthesized and tested across multiple lifetimes. This combinatorial explosion means that even high-throughput methods can only sample a minuscule fraction of possible candidates. While forward screening might evaluate hundreds or thousands of candidates, inverse design approaches like generative models can navigate these spaces more efficiently by learning underlying patterns and focusing only on promising regions [13].

High Costs and Slow Iteration Cycles

The resource-intensive nature of forward screening creates practical constraints on discovery timelines and budgets. Experimental procedures for synthesizing and characterizing materials require significant financial investment in reagents, equipment, and personnel time. For instance, the process of ENU mutagenesis in mice followed by breeding and phenotypic screening requires substantial animal husbandry resources and extends over many months [11]. These slow iteration cycles limit how quickly hypotheses can be tested and refined, particularly compared to computational approaches that can generate and evaluate thousands of virtual candidates in the time required for a single experimental measurement.

Dependence on Preconceived Hypotheses and Existing Knowledge

Traditional forward screening approaches often incorporate implicit biases based on existing knowledge, as researchers tend to focus on candidate libraries derived from known material systems or structural classes. This dependence on preconceived hypotheses can limit serendipitous discovery and creates a "known-unknowns" problem where researchers only explore variations of existing solutions rather than truly novel configurations [8]. Inverse design's ability to explore non-obvious solutions was demonstrated in the discovery of Mo₃Co for hydrogen storage—a material not previously reported and potentially counterintuitive based on conventional wisdom [9].

Inability to Leverage Multidimensional Property Data

Modern materials characterization often generates complex, multidimensional data such as electronic density of states (DOS) patterns, spectral signatures, or structure-property relationships. Forward screening struggles to utilize this rich information comprehensively, typically reducing candidate selection to one or two simplified metrics. Inverse design models excel in this context, as they can directly incorporate multidimensional properties as inputs. For example, recent advances have enabled inverse design from complete DOS patterns rather than simplified descriptors like d-band center, preserving more complete electronic structure information for materials discovery [9].

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Approaches

Forward Screening Protocol: Genetic Approach in Model Organisms

A detailed protocol for forward genetic screening in C. elegans exemplifies the methodological rigor and multiple stages required in comprehensive forward screening approaches [12]:

Mutagenesis: Treatment with ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS) to induce random mutations throughout the genome. EMS typically causes point mutations, with a preference for G/C to A/T transitions.

Primary Screening: Systematic evaluation of F2 progeny for mutants displaying a phenotype of interest. Weak mutants are often retained as they may identify genes with functional redundancy.

Backcrossing: Outcrossing isolated mutants to separate the causal mutation from background mutations and confirm heritability of the phenotype.

Complementation Testing: Crossing mutants to known genes in the pathway of interest to determine if the mutation represents a novel gene.

Positional Cloning & Whole-Genome Sequencing: Identification of causal mutations through a combination of genetic mapping and sequencing technologies.

This multi-stage process typically requires 3-6 months for completion and involves specialized expertise in genetics, molecular biology, and bioinformatics [12].

Inverse Design Protocol: Deep Learning for Materials Discovery

A state-of-the-art inverse design protocol for discovering inorganic materials with target electronic density of states (DOS) patterns demonstrates the computational workflow [9]:

Data Curation: Collect and preprocess a large database of materials structures and corresponding DOS patterns (e.g., 32,659 DOS patterns from Materials Project) [9].

Representation Learning: Develop an invertible representation that encodes material composition—such as Composition Vectors (CVs) formed by concatenating Element Vectors (EVs)—that preserves chemical information while being machine-readable [9].

Model Training: Train a convolutional neural network (CNN) to map between DOS patterns (input) and composition vectors (output) using the collected database.

Inverse Prediction: Input target DOS patterns into the trained model to generate candidate composition vectors, which are then decoded into specific material compositions.

Validation: Verify predicted materials through density functional theory (DFT) calculations or targeted synthesis to confirm they exhibit the desired DOS properties.

This approach has achieved 99% composition accuracy and 85% DOS pattern accuracy in benchmark tests, successfully identifying novel materials for applications such as catalysis and hydrogen storage [9].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Forward and Inverse Design

| Tool/Resource | Function/Role | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) | Chemical mutagen that induces random point mutations at high density [11] | Forward genetic screening in model organisms |

| EMS (Ethyl methanesulfonate) | Alkylating agent used to create random mutagenesis in genetic screens [12] | C. elegans and other model organism genetics |

| Composition Vectors (CVs) | Machine-readable representations encoding material composition as concatenated element vectors [9] | Inverse design of inorganic materials |

| Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) | Deep learning framework that pits generator and discriminator networks against each other to produce realistic data [13] | Inverse design of zeolites and porous materials |

| Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) | Neural network architecture that learns latent representations of input data for generation [13] | Discovery of metastable vanadium oxide compounds |

| High-Throughput Screening Robotics | Automated systems for rapidly testing large libraries of compounds or materials | Experimental forward screening |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Computational method for modeling electronic structure and predicting material properties | Validation of inverse design predictions |

The limitations of forward screening in modern materials discovery research have become increasingly apparent as chemical spaces grow more complex and multidimensional property data becomes more central to materials optimization. The combinatorial explosion of possible candidates, high resource requirements, dependence on existing knowledge frameworks, and inability to fully leverage complex property data collectively constrain the potential of forward approaches alone to drive future innovation. Inverse design paradigms address these limitations by reframing discovery as an optimization problem, leveraging computational power to navigate vast design spaces efficiently and without predefined structural biases.

Nevertheless, the most promising path forward lies not in exclusive adoption of either paradigm but in their strategic integration. Forward screening remains invaluable for validating computational predictions, exploring regions of chemical space where reliable models are unavailable, and generating high-quality training data for machine learning approaches. Inverse design excels at navigating complex, high-dimensional spaces and generating novel candidates that would be unlikely discovered through human intuition alone. As these approaches continue to evolve—with advances in multimodal AI [14], automated experimentation, and data infrastructure—we anticipate increasingly sophisticated hybrid frameworks that leverage the complementary strengths of both paradigms to accelerate materials discovery across scientific disciplines and application domains.

Operational Pitfalls: How Data and Workflow Flaws Undermine Screening Success

Forward screening, the process of using computational models to predict and identify promising new materials, is a cornerstone of modern materials discovery. However, its effectiveness is fundamentally constrained by the quality and completeness of the underlying databases used to train these models. Data scarcity, characterized by datasets containing only hundreds to thousands of samples, and systematic data bias, arising from uneven coverage of chemical and structural space, severely limit the generalizability and predictive power of machine learning (ML) models [15] [16]. In applications where failed experimental validation is time-consuming and costly, such as battery development or drug formulation, these limitations can lead to erroneous conclusions and wasted resources. This technical guide examines the consequences of incomplete materials databases within the context of forward screening, detailing the quantitative impacts, methodological frameworks for assessment, and potential solutions to mitigate these critical challenges.

Quantifying the Data Scarcity and Bias Problem

The scale of materials data is often insufficient for robust model training. Exemplar datasets for key material properties frequently contain fewer than 1,000 samples, as shown in Table 1, which summarizes the characteristics of several benchmark datasets used in data-scarce ML research [15].

Table 1: Exemplar Data-Scarce Materials Property Datasets

| Dataset | Total Number of Samples | Maximum Number of Atoms | Property Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jarvis2d Exfoliation | 636 | 35 | (0.03, 1604.04) |

| MP Poly Total | 1,056 | 20 | (2.08, 277.78) |

| Vacancy Formation Energy (ΔHV) | 1,670 | Not Specified | Not Specified |

| Work Function (ϕ) | 58,332 | Not Specified | Not Specified |

| Bulk Modulus (log(KVRH)) | 10,563 | Not Specified | Not Specified |

Data bias presents a parallel challenge. Real-world materials databases often suffer from an uneven distribution of data points across different chemical systems, crystal structures, and property spaces. For instance, research into battery materials has historically focused on cobalt- and nickel-rich cathode chemistries due to their high energy density, creating a significant data void for more affordable and abundant alternatives, such as iron-based compounds [17]. This bias means that ML models trained on such data are inherently ill-equipped to accurately screen materials from underrepresented chemical families, directly limiting the scope of forward screening campaigns.

Consequences for Model Generalizability and Performance

The primary consequence of data scarcity and bias is the degradation of model performance, particularly in out-of-distribution (OOD) generalization. When a model is tasked with predicting properties for materials that are chemically or structurally distinct from those in its training set, performance can drop precipitously.

Standard random-split validation protocols often provide overly optimistic performance estimates because the test set is drawn from the same biased distribution as the training data, a phenomenon known as data leakage [16]. For example, in modeling vacancy formation energies and surface work functions, where multiple training examples can originate from the same base crystal structure, the expected model error for inference can vary by a factor of 2–3 depending on the data splitting strategy used for validation [16]. This indicates that a model's reported accuracy on a random test set is a poor indicator of its real-world performance in a forward-screening context targeting novel materials.

The impact of data scarcity on predictive accuracy is quantitatively demonstrated in semi-supervised learning scenarios. As shown in Table 2, models trained on only a fraction of the available data (denoted as "S") show significantly higher error compared to those trained on the full dataset ("F"). Introducing synthetic data ("GS") can help, but performance often remains inferior to models trained on large, real datasets, highlighting the fundamental challenge of data scarcity [15].

Table 2: Impact of Data Scarcity on Model Performance (Mean Absolute Error)

| Datasets | F (Full Data) | S (Scarce Data) | GS (Synthetic Data) | S + GS (Combined) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jarvis2d Exfoliation | 62.01 ± 12.14 | 64.03 ± 11.88 | 64.51 ± 11.84 | 63.57 ± 13.43 |

| MP Poly Total | 6.33 ± 1.44 | 8.08 ± 1.53 | 8.09 ± 1.47 | 8.04 ± 1.35 |

Methodological Framework: Assessing Generalizability with MatFold

To systematically evaluate and mitigate the risks of data scarcity and bias, researchers can employ standardized cross-validation (CV) protocols. The MatFold procedure provides a featurization-agnostic toolkit for generating reproducible and increasingly difficult data splits to stress-test a model's OOD generalizability [16].

MatFold Splitting Criteria and Protocol

MatFold generates data splits based on a variety of chemically and structurally motivated criteria, creating a hierarchy of generalization difficulty:

- Outer K-folds Splits (CK):

Random,Structure,Composition,Chemical system (Chemsys),Element,Periodic table (PT) group,PT row,Space group number (SG#),Point group,Crystal system. - Inner L-folds Splits (CL): Can be

Randomor use any of the outer split criteria. - Additional Parameters: Dataset size reduction factor (D), assignment of specific compounds (e.g., binaries) to training set (T), and fold counts (K, L).

The workflow for a MatFold analysis, which directly addresses the limitations imposed by database incompleteness, is as follows:

Diagram 1: MatFold Cross-Validation Workflow

This systematic approach allows researchers to quantify the "generalizability gap"—the difference between a model's performance on easy random splits versus challenging structural or chemical hold-out splits—providing a more realistic assessment of its utility in forward screening.

Emerging Solutions: Synthetic Data and the Data Flywheel

To combat data scarcity directly, researchers are turning to generative models to create synthetic materials data. The MatWheel framework exemplifies this approach, aiming to establish a "data flywheel" where synthetic data is used to improve both generative and property prediction models iteratively [15].

The MatWheel Framework and Experimental Insights

MatWheel operates under two primary scenarios:

- Fully Supervised Learning: A conditional generative model (e.g., Con-CDVAE) is trained on all available real data. It then generates synthetic material structures conditioned on property values sampled from a Kernel Density Estimate (KDE) of the training distribution. The predictive model (e.g., CGCNN) is subsequently trained on a combination of real and synthetic data.

- Semi-Supervised Learning: A predictive model is first trained on a small subset (e.g., 10%) of the available real data. This model generates pseudo-labels for the remaining unlabeled data. The generative model is then trained on this combined set (real-labeled and pseudo-labeled data) and generates a synthetic dataset. Finally, the predictive model is retrained on the original real data and the new synthetic data.

Experimental results indicate that synthetic data shows the most promise in extreme data-scarce scenarios (semi-supervised). While training on synthetic data alone generally yields the poorest performance, strategically combining it with limited real data can achieve performance close to that of models trained on the full real dataset [15]. This suggests that synthetic data can help mitigate the impact of scarcity, though it is not a perfect substitute for real data.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Data-Centric Materials Discovery

| Tool / Resource | Function | Key Features / Application |

|---|---|---|

| MatFold [16] | Standardized cross-validation toolkit | Generates chemically-motivated data splits; assesses OOD generalizability; reproducible benchmarking. |

| MatWheel [15] | Synthetic data generation framework | Implements data flywheel using conditional generative models (Con-CDVAE) to alleviate data scarcity. |

| Conditional Generative Models (e.g., Con-CDVAE) [15] | Synthetic data generation | Generates novel material structures conditioned on target properties; expands training datasets. |

| Graph Convolutional Neural Networks (e.g., CGCNN) [15] | Property prediction | Learns from crystal structures by modeling atomic spatial relationships; effective for data-scarce learning. |

| Leave-One-Cluster-Out CV (LOCO-CV) [16] | Model validation | Tests generalizability by holding out entire clusters of similar materials from training. |

Data scarcity and bias in materials databases pose significant, quantifiable limitations to the forward-screening paradigm. Relying on simplistic validation methods and small, biased datasets leads to models with poor out-of-distribution generalizability, increasing the risk and cost of failed experimental validation. Addressing these challenges requires a methodological shift towards rigorous, standardized validation protocols like those enabled by MatFold and the strategic use of synthetic data generation frameworks like MatWheel. By openly acknowledging and systematically accounting for the incompleteness of our materials databases, researchers can develop more reliable and robust models, ultimately accelerating the discovery of novel materials.

The adoption of data-driven science heralds a new paradigm in materials science, where knowledge is extracted from large, complex datasets that defy traditional human reasoning [18]. Within this paradigm, surrogate models—fast, approximate models trained to mimic the behavior of expensive simulations or experiments—have become established tools in the materials research toolkit [18] [19]. However, these models often function as "black boxes" whose internal logic remains opaque, creating a significant trap for researchers: the inability to extract interpretable physical insights and understand the causal mechanisms behind model predictions [20] [21]. This limitation is particularly acute in forward screening approaches for materials discovery, which systematically evaluate predefined candidates against target properties but struggle to explore beyond known chemical spaces and suffer from low success rates [1].

The core of the black-box problem lies in the fundamental trade-off between predictive performance and interpretability. Complex models such as deep neural networks, graph neural networks (GNNs), and ensemble methods often deliver superior accuracy but obscure the physical relationships between input parameters and material properties [19] [22]. When researchers cannot understand why a model makes specific predictions, they struggle to (1) validate results against domain knowledge, (2) identify novel physical mechanisms, and (3) build the intuitive understanding necessary for scientific breakthroughs [20] [21]. This paper examines the manifestations, implications, and potential solutions to the interpretability crisis in surrogate modeling for materials discovery.

The Forward Screening Paradigm and Its Fundamental Limitations

Forward screening represents a natural, widely-used methodology in computational materials discovery wherein researchers systematically evaluate a set of predefined material candidates to identify those meeting specific property criteria [1]. The typical workflow, illustrated in Figure 1, begins with candidate generation from existing databases, applies property filters based on domain requirements, and leverages computational frameworks like Atomate and AFLOW for high-throughput evaluation [1].

Figure 1. Forward screening workflow for materials discovery. This one-way process applies selection criteria to existing databases but cannot extrapolate beyond known data distributions [1].

Despite its widespread application across various material classes—including thermoelectric materials, battery components, and catalysts—forward screening faces fundamental limitations that the black-box nature of surrogate models exacerbates:

- Lack of exploration: The screening process operates as a one-way filter on existing databases without extrapolation capabilities, fundamentally constraining discovery to regions near known materials [1].

- Severe class imbalance: Only a tiny fraction of candidates typically exhibits desirable properties, resulting in inefficient allocation of computational resources toward evaluating ultimately unsuccessful materials [1].

- Combinatorial explosion: The materials design space is astronomically large, with stringent stability conditions creating high failure rates for naïve traversal approaches [1].

- Absence of physical insights: Even successful predictions rarely provide understanding of underlying structure-property relationships, hindering scientific intuition development [20].

These limitations become particularly pronounced when compared to emerging inverse design approaches, which start from desired properties and work backward to identify candidate structures, potentially offering a more efficient discovery pathway [1].

Methodologies: Experimental Protocols for Surrogate Model Interpretation

Global Surrogate Modeling Protocol

The global surrogate model approach creates an interpretable model that approximates the predictions of a black-box model, enabling researchers to draw conclusions about the black box's behavior [23]. The experimental protocol involves these critical steps:

- Dataset Selection: Choose a dataset (X) which may be the training data for the black-box model or new data from the same distribution [23].

- Black-Box Prediction: Obtain predictions for the selected dataset using the existing black-box model [23].

- Interpretable Model Selection: Select an interpretable model type (linear models, decision trees, etc.) based on the explanation needs [23].

- Surrogate Training: Train the interpretable model on dataset X and the corresponding black-box predictions [23].

- Fidelity Measurement: Quantify how well the surrogate replicates black-box predictions using metrics like R-squared [23].

The R-squared measure calculates the percentage of variance captured by the surrogate model: R² = 1 - SSE/SST, where SSE represents the sum of squared errors between surrogate and black-box predictions, and SST represents the total sum of squares of black-box predictions [23]. Values close to 1 indicate excellent approximation, while values near 0 signal failure to explain the black-box behavior [23].

Physics-Informed Bayesian Optimization

For materials design applications where physical knowledge is partially available, Physics-Informed Bayesian Optimization (BO) represents a promising gray-box approach that integrates theoretical information with statistical data [24]. The methodology incorporates physics-infused kernels into Gaussian Processes to leverage both physical and statistical information, transforming purely black-box optimization into gray-box optimization [24]. This enhancement is particularly valuable for designing complex material systems such as NiTi shape memory alloys, where identifying optimal processing parameters to maximize transformation temperature benefits from incorporating domain knowledge [24].

Causality-Driven Surrogate Modeling

The causality-driven approach employs double machine learning (DML) to estimate heterogeneous treatment effects (HTEs) that quantify how control inputs influence outcomes under varying contextual conditions [21]. This method provides:

- Causal interpretability through linear regression-based DML frameworks that produce interpretable coefficients showing how parameter impacts vary across contexts [21].

- High predictive fidelity with accuracy comparable to full-scale simulations across broad input spectra [21].

- Optimization readiness through low-dimensional numerical structures that facilitate computationally efficient optimization [21].

Quantitative Analysis of Surrogate Model Performance

Table 1. Performance comparison of surrogate modeling approaches across materials science applications

| Methodology | Application Domain | Key Performance Metrics | Interpretability Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Surrogates [23] | General black-box interpretation | R²: 0.71-0.76 on test cases | Flexible; works with any black-box; intuitive | Uncertain R² thresholds; approximation gaps |

| Physics-Informed BO [24] | NiTi shape memory alloy design | Improved decision-making efficiency | Incorporates physical laws; data-efficient | Requires partial physical knowledge |

| GNoME Active Learning [22] | Crystal structure prediction | Hit rate: >80% (structure), 33% (composition) | Emergent generalization to 5+ elements | Computational intensity; model complexity |

| Causality-Driven DML [21] | DOAS preheating control | High predictive fidelity vs. full simulator | Causal coefficients; context-aware impacts | Linear regression limitations |

Table 2. Evolution of AI approaches in materials inverse design

| Algorithm Category | Examples | Interpretability Characteristics | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary Algorithms [1] | Genetic Algorithms, Particle Swarm Optimization | Moderate (operators traceable) | Structure prediction, compositional optimization |

| Adaptive Learning Methods [1] [24] | Bayesian Optimization, Reinforcement Learning | Low to moderate (acquisition functions) | Processing optimization, microstructure design |

| Deep Generative Models [1] | VAEs, GANs, Diffusion Models | Very low (complex latent spaces) | Crystal structure generation, molecule design |

| Graph Neural Networks [22] | GNoME, GNN interatomic potentials | Low (message passing obscure) | Crystal stability prediction, property forecasting |

Table 3. Essential research reagents and computational tools for surrogate modeling research

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Processes [24] | Surrogate modeling with uncertainty quantification | Bayesian Optimization frameworks |

| Graph Neural Networks [22] | Materials representation learning | Crystal property prediction, stability analysis |

| Double Machine Learning [21] | Causal effect estimation | Interpretable surrogate control models |

| Variational Autoencoders [1] | Latent space learning for generation | Materials inverse design |

| Diffusion Models [1] | High-quality data generation | Stable materials generation |

| Active Learning Frameworks [22] | Intelligent data acquisition | Materials discovery campaigns |

| Benchmark Datasets [22] | Model training and validation | Materials Project, OQMD, ICSD |

Pathway Toward Interpretable Surrogate Modeling

The integration of explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) techniques with surrogate modeling presents a promising pathway to overcome the black-box trap [20]. This unified workflow combines surrogate modeling with global and local explanation techniques to enable transparent analysis of complex systems [20]. The complementary approaches of global explanations (feature effects, sensitivity analysis) and local attributions (instance-level importance scores) provide both system-level relationships and actionable drivers for individual predictions [20].

Figure 2. Iterative framework for interpretable surrogate modeling in materials science. This workflow integrates physical knowledge with explainable AI to build trustworthy models [20] [21].

The critical requirement for effective surrogate modeling in scientific applications is maintaining physical consistency while ensuring computational efficiency [21]. As demonstrated in building energy systems, surrogate models must not only achieve predictive accuracy but also adhere to thermodynamic principles and provide causal interpretability [21]. This necessitates moving beyond purely statistical correlations to models that capture genuine causal influences, enabling researchers to trust and act upon the insights generated [21].

The black-box trap in surrogate modeling represents a significant challenge for materials discovery, particularly within the forward screening paradigm. While surrogate models offer dramatic acceleration in computational workflows—reducing prediction times from hours to milliseconds—their lack of interpretability fundamentally limits their scientific utility [19] [20]. Overcoming this limitation requires a multifaceted approach that integrates physics-informed modeling, causality-driven frameworks, and explainable AI techniques [24] [20] [21].

The materials research community must prioritize interpretability-by-design in surrogate model development, recognizing that predictive accuracy alone is insufficient for scientific advancement. By adopting the methodologies and frameworks outlined in this review—including global surrogate models, physics-informed Bayesian optimization, and causality-driven approaches—researchers can transform black-box traps into transparent, insightful discovery tools. This paradigm shift will be essential for accelerating the development of novel materials with tailored properties, ultimately bridging the gap between data-driven predictions and fundamental physical understanding.

Forward screening, a widely used methodology in computational materials discovery, operates on a fundamentally straightforward principle: systematically evaluating a large set of candidate materials to identify those that meet specific target property criteria [1]. This approach typically involves collecting candidates from existing databases, applying property thresholds as filters, and using computational tools like density functional theory (DFT) or machine learning surrogate models for evaluation [1]. While this paradigm has enabled significant discoveries across various materials classes—including thermoelectrics, magnets, and two-dimensional materials—it suffers from critical limitations that severely restrict its ability to predict real-world viability [1].

The most fundamental challenge lies in forward screening's inherent inability to adequately address synthesizability and stability. This approach operates as a one-way process that applies criteria to existing databases without the capability to extrapolate beyond known data distributions [1]. Furthermore, it faces a severe class imbalance problem—only a tiny fraction of candidates exhibit desirable properties, leading to inefficient allocation of computational resources toward evaluating materials that ultimately fail to meet target criteria [1]. These limitations become particularly problematic when considering that thermodynamic stability calculations, often used as a primary filter, typically overlook finite-temperature effects, entropic factors, and kinetic barriers that govern synthetic accessibility in laboratory settings [25].

This technical guide examines the core challenges in predicting synthesizability and stability, presents advanced computational frameworks addressing these limitations, and provides experimental methodologies for validating real-world viability. By framing these issues within the context of forward screening's constraints, we aim to equip researchers with practical tools for bridging the gap between computational prediction and experimental realization.

The Synthesizability Prediction Challenge

Beyond Thermodynamic Stability

The assessment of synthesizability represents a grand challenge in accelerating materials discovery through computational means [26]. While thermodynamic stability—typically quantified by the energy above hull (E$__{\text{hull}}$)—provides a useful initial filter, it constitutes an insufficient predictor for experimental realization [25]. Synthesis is a complex process governed not only by a material's thermodynamic stability relative to competing phases but also by kinetic factors, advances in synthesis techniques, precursor availability, and even shifts in research focus [26].

The complexity of these interacting factors makes developing a general, first-principles approach to synthesizability currently impractical [26]. Consequently, data-driven methods that capture the collective influence of these factors through historical experimental evidence have emerged as a promising alternative. These approaches recognize that the collective influence of all complex factors affecting synthesizability is already reflected in the measured ground truth: whether a material was successfully synthesized and characterized [26].

Quantifying the Screening Efficiency Problem

The severity of the forward screening efficiency problem becomes evident when examining the statistics of large-scale materials databases. Current efforts in machine-learning-accelerated, ultra-fast in-silico screening have unlocked vast databases of predicted candidate structures, with resources such as the Materials Project, GNoME, and Alexandria containing structures that now exceed the number of experimentally synthesized compounds by more than an order of magnitude [25].

Table 1: Scale of the Materials Screening Challenge

| Database/Resource | Predicted Structures | Experimentally Realized | Success Rate Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| GNoME | Millions | Severe class imbalance | |

| Materials Project | >100,000 | Limited synthesizability assessment | |

| Alexandria | Millions | Filtering challenge | |

| ICSD | ~200,000 known crystals | ~200,000 | Limited diversity for novel discovery |