Beyond the Data Wall: A Research-Driven Framework for High-Quality Synthetic Data in Materials Science

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on generating and validating high-quality synthetic data to overcome data scarcity in materials research.

Beyond the Data Wall: A Research-Driven Framework for High-Quality Synthetic Data in Materials Science

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on generating and validating high-quality synthetic data to overcome data scarcity in materials research. It covers the foundational principles of synthetic data, explores advanced generation methods like GANs and diffusion models, and details rigorous validation protocols to ensure statistical fidelity and utility. The content also addresses critical challenges such as bias mitigation, realism, and integration with real-world data, offering a strategic framework to accelerate discovery, enhance AI model robustness, and reduce reliance on costly physical experiments.

Synthetic Data Fundamentals: Defining Quality and Overcoming Real-World Data Scarcity

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Synthetic Data for Materials Research

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is synthetic data and how can it address data scarcity in materials research? Synthetic data is artificially generated information that mimics the statistical properties and patterns of real-world data but does not contain any actual measurements or sensitive details [1] [2]. It is created algorithmically using generative models [3]. For materials research, it addresses data scarcity by generating unlimited volumes of realistic data for rare material properties or expensive-to-test scenarios, effectively filling gaps where real data is unavailable or insufficient [3] [4].

FAQ 2: What are the main types of synthetic data relevant to scientific research? There are three primary types, each with different applications in materials research [1]:

- Fully Synthetic Data: Created entirely from algorithms without using any real data, ideal for initial model testing or simulating hypothetical material systems.

- Partially Synthetic Data: Only sensitive or missing data points are replaced with generated values, useful for preserving proprietary material formulas while maintaining dataset utility.

- Hybrid Synthetic Data: Combines real and synthetic data points, useful for augmenting small experimental datasets with additional generated samples.

FAQ 3: My model performs well on synthetic data but poorly on real experimental data. What could be wrong? This is often an efficacy or fidelity issue [5] [6]. The synthetic data may not have captured the full complexity or underlying physical relationships of the real material system. To troubleshoot:

- Verify that the generative model was trained on a representative sample of real data that includes edge cases and rare material behaviors [1] [4].

- Implement a more rigorous validation workflow (see Diagram 2 below) to test model performance on real data before deployment [5].

- Consider a fidelity-agnostic approach: Ensure the synthetic data is optimized for your specific prediction task rather than just general statistical similarity [6].

FAQ 4: How can I ensure the synthetic data I generate does not perpetuate or amplify existing biases in my limited real dataset? Bias amplification is a key risk [5] [4]. Mitigation strategies include:

- Careful Analysis of Source Data: Before generation, thoroughly analyze the original data's distributions and correlations to understand potential biases [1].

- Purposeful Sampling and Calibration: Use techniques to deliberately oversample underrepresented scenarios or conditions to create balanced datasets [2] [4].

- Rigorous Statistical Testing: Compare synthetic and real data distributions using statistical tests (e.g., Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests) and involve domain experts for validation [1].

FAQ 5: What are the best practices for validating synthetic data before using it to train a predictive model? Validation is a multi-step process [1] [5]:

- Statistical Validation: Ensure synthetic data matches the statistical properties (mean, variance, correlations) of the original data.

- Domain Expert Validation: Have materials scientists assess whether the data realistically represents physical phenomena.

- Task-Specific Validation (Efficacy): Test if a model trained on synthetic data performs accurately on a small, held-out set of real experimental data [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Cost of Data Generation for Rare Material Events

- Solution: Use synthetic data for data augmentation. Generate additional synthetic examples of rare events (e.g., material failure conditions, rare phase transitions) to significantly improve the accuracy and robustness of predictive models without the cost of additional physical experiments [2] [4].

Problem: Data Sensitivity and Privacy in Collaborative Research

- Solution: Leverage fully synthetic or hybrid synthetic data [1]. Generate a synthetic dataset that preserves the statistical relationships and patterns of the sensitive experimental data (e.g., proprietary alloy compositions) but contains no real measurements. This dataset can be shared freely with collaborators without confidentiality concerns [3] [4].

Problem: Inability to Test Models on Sufficient "What-If" Scenarios

- Solution: Use synthetic data for scenario planning and simulation [4]. Generate data that mimics the behavior of materials under novel or hypothetical conditions that have not yet been physically tested (e.g., performance under extreme temperatures or new chemical environments). This allows for controlled experimentation and risk-free testing of models [3].

Methodologies and Data Presentation

Synthetic Data Generation Techniques

The table below summarizes the core methods for generating synthetic data.

| Method | Core Principle | Best Use-Cases in Materials Research |

|---|---|---|

| Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [1] [3] | Two neural networks (generator and discriminator) compete to produce realistic data. | Generating high-dimensional data like microstructural images; capturing complex, non-linear relationships in material properties. |

| Statistical & Machine Learning Models [1] [3] | Uses probabilistic frameworks (e.g., Gaussian mixtures) to capture and replicate underlying data distributions. | Creating tabular data of material properties where statistical fidelity is paramount. |

| Rule-Based Generation [1] | Applies predefined business or scientific rules to create data that follows specific patterns. | Generating data where clear physical laws or hierarchical relationships exist (e.g., phase diagrams). |

| Data Augmentation [1] | Applies transformations (rotation, noise injection) to existing data points to increase dataset variety. | Expanding a limited set of material images or spectral data for training computer vision models. |

Experimental Protocol: Generating and Validating Synthetic Data for a Predictive Model

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide for a typical synthetic data workflow.

1. Define Objective and Acquire Seed Data

- Clearly define the predictive task for the AI model (e.g., predict material strength based on composition and processing parameters).

- Gather all available real-world data ("seed data"). This dataset should be as representative and clean as possible [1].

2. Select and Apply a Generation Technique

- Choose a generation method from the table above based on your data type and need. For example, use GANs for image data or statistical models for tabular data [1] [3].

- Use tools like the Synthetic Data Vault (SDV) [1], Gretel [1], or Mostly.AI [1] to build the generative model and create the synthetic dataset.

3. Validate the Synthetic Data This critical step involves multiple checks, as visualized in the following workflow.

4. Integrate and Monitor

- Use the validated synthetic data to train your AI/machine learning model.

- Continuously monitor the model's performance in real-world applications. If performance degrades, retrain the model with updated synthetic and real data [2] [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key computational "reagents" – the tools and platforms used to generate synthetic data.

| Tool / Platform | Function | Key Features for Materials Research |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Data Vault (SDV) [1] | Open-source Python library for generating synthetic tabular data. | Captures relational data from multiple tables; powerful for complex datasets with multiple interrelated parameters (e.g., process-structure-property linkages). |

| Gretel [1] | Cloud-based platform for generating synthetic data across multiple data types (tabular, text). | Provides APIs for easy integration into data workflows; focuses on metrics for quality and privacy protection. |

| Mostly.AI [1] | AI-powered platform for generating structured synthetic data. | Excels at maintaining statistical fidelity and granular data insights while ensuring privacy; supports time-series data, useful for temporal process data. |

| Synthea [1] | Open-source synthetic patient population generator. | While designed for healthcare, its principle of modeling complex systems from foundational rules can be inspirational for simulating material populations or supply chains. |

| GANs & VAEs (General Implementations) [1] [3] | Deep learning architectures for generating complex data. | Ideal for creating synthetic images of material microstructures or spectra; can learn and replicate highly complex, non-linear patterns. |

Logical Workflow: From Data Crisis to Solution

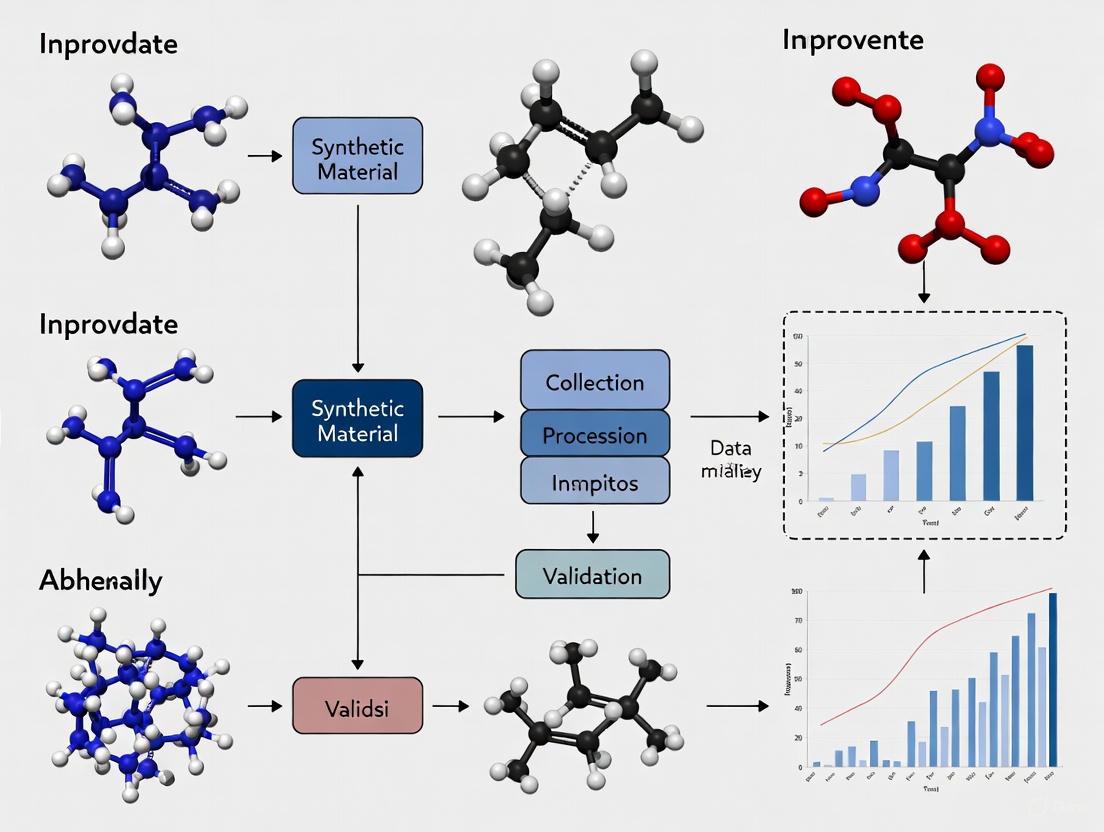

The following diagram outlines the logical pathway for overcoming data challenges in materials research using synthetic data.

Fundamental Definitions and Core Concepts

What is synthetic data?

Synthetic data is artificially generated information created by computer algorithms or statistical methods, rather than being collected from real-world events or measurements. In scientific contexts such as materials research and drug development, it serves as a proxy for real data, mimicking its statistical properties and patterns without containing any actual sensitive or proprietary information [7] [8] [9].

How do process-driven and data-driven generation paradigms differ?

The creation of synthetic data follows two distinct philosophical and methodological approaches:

Process-Driven Generation utilizes computational or mechanistic models based on established physical, biological, or clinical processes. These models typically employ known mathematical equations—such as ordinary differential equations (ODEs)—to generate data that simulates real-world behavior. Examples include pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) models, physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models, and agent-based simulations [7].

Data-Driven Generation relies on statistical modeling and machine learning techniques trained on observed data. These methods learn patterns and relationships from existing datasets and create new synthetic datasets that preserve population-level statistical distributions. Prominent techniques include Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), and Diffusion Models [7].

Table: Comparison of Synthetic Data Generation Paradigms

| Aspect | Process-Driven | Data-Driven |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Foundation | First principles, mechanistic models | Pattern recognition, statistical learning |

| Data Requirements | Can operate with minimal observed data | Typically requires substantial training data |

| Primary Applications | Hypothesis testing, simulation studies, early-stage research | Data augmentation, privacy preservation, complex pattern replication |

| Interpretability | High (based on established equations) | Variable (often "black box") |

| Example Methods | ODE-based modeling, agent-based simulations | GANs, VAEs, Diffusion Models, synthpop R package |

| Strength in Materials Research | Exploring novel materials with limited data | Enhancing predictive models with data augmentation |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Protocol 1: Implementing a Fully Supervised Data Generation Workflow using MatWheel Framework

The MatWheel framework demonstrates a complete pipeline for generating synthetic materials data in a fully supervised setting [10]:

Step 1: Data Preparation and Conditioning

- Collect a real-world dataset of material structures and properties (e.g., from Matminer database)

- Split data into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets

- For conditional generation, perform kernel density estimation (KDE) on the discrete distribution of the training data to model property ranges

Step 2: Conditional Generative Model Training

- Select an appropriate conditional generative model (e.g., Con-CDVAE for materials)

- Train the model using the full training dataset with property conditions as input

- Apply diffusion processes to atomic counts, species, coordinates, and lattice vectors

- Validate model outputs against known material structures and properties

Step 3: Synthetic Data Generation and Validation

- Sample conditions from the estimated KDE distribution

- Generate synthetic material structures using the conditioned generative model

- Create an expanded synthetic dataset (e.g., 1,000 samples)

- Validate synthetic data quality through structural feasibility and property consistency checks

Step 4: Predictive Model Enhancement

- Train property prediction models (e.g., CGCNN) on combined real and synthetic data

- Evaluate model performance on held-out test sets

- Compare results with models trained exclusively on real data

Protocol 2: Semi-Supervised Framework for Data-Scarce Scenarios

This protocol addresses extreme data scarcity scenarios common in novel materials research [10]:

Step 1: Initial Model Training with Limited Data

- Utilize only a small fraction (e.g., 10%) of the available training data

- Train an initial property prediction model on this limited dataset

- Generate pseudo-labels for the remaining unlabeled training data through model inference

Step 2: Generative Model Training with Expanded Labels

- Train the conditional generative model on the combined real and pseudo-labeled data

- This step incorporates the potentially noisy but expanded label information into the generation process

Step 3: Iterative Data Flywheel Implementation

- Generate synthetic data using the conditionally trained model

- Retrain the predictive model on both the original real data and new synthetic data

- Use the improved predictive model to generate more accurate pseudo-labels

- Repeat the cycle to progressively enhance both generative and predictive capabilities

Semi-Supervised Data Flywheel Workflow

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Encountered Technical Challenges and Solutions

Problem: Synthetic Data Lacks Realism and Complexity Symptoms: Generated materials exhibit unrealistic properties, unstable structures, or fail basic physical validity checks. Solutions:

- Implement hybrid validation combining statistical metrics and physical constraints

- Incorporate domain knowledge through rule-based filters during generation

- Use ensemble generation methods to improve diversity

- Apply multi-scale validation from atomic to macroscopic properties [11] [12]

Problem: Model Collapse in Iterative Generation Symptoms: Successive generations show decreasing diversity and quality in synthetic data. Solutions:

- Implement regularization techniques in generative model training

- Maintain a reservoir of high-quality real data samples in each iteration

- Monitor diversity metrics (e.g., pairwise distance, property distribution)

- Introduce controlled randomization in the sampling process [10]

Problem: Propagation and Amplification of Biases Symptoms: Synthetic data replicates or exaggerates limitations present in the original dataset. Solutions:

- Conduct comprehensive data profiling before generation

- Implement bias detection metrics specific to materials science

- Use targeted generation to address underrepresented regions in property space

- Apply fairness constraints in conditional generation [11] [9]

Problem: High Computational Costs in Generation Symptoms: Synthetic data generation requires prohibitive computational resources or time. Solutions:

- Implement progressive generation techniques (coarse-to-fine)

- Utilize transfer learning from pre-trained generative models

- Employ distributed computing frameworks for parallel generation

- Optimize generation parameters based on required fidelity levels [13]

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How can we evaluate the quality of synthetic materials data? Synthetic data quality should be assessed across three essential pillars:

- Fidelity: How well the synthetic data preserves properties of the original data (statistical distributions, correlations)

- Utility: How effectively the synthetic data performs in downstream tasks (predictive modeling, discovery applications)

- Privacy: For sensitive applications, the degree to which synthetic data prevents disclosure of proprietary information [9]

Q2: When should researchers choose process-driven versus data-driven approaches? The choice depends on several factors:

- Process-driven is preferable when mechanistic understanding is strong, data is extremely scarce, or for hypothesis testing novel conditions beyond available data.

- Data-driven excels when substantial training data exists, complex patterns need replication, or for data augmentation in established domains [7].

Q3: Can synthetic data completely replace real experimental data in materials research? No. Synthetic data should be viewed as a powerful complement to, not a replacement for, real data. It excels at augmentation, exploration, and preliminary validation, but final confirmation typically requires physical experimentation due to the risk of model drift and uncaptured physical phenomena [11] [12].

Q4: How can we address the "reality gap" where synthetic data diverges from physical truth?

- Implement continuous validation against new experimental data

- Develop hybrid models that incorporate physical constraints

- Establish feedback loops where synthetic predictions guide targeted experimentation

- Maintain calibration protocols to align synthetic and real data distributions [11] [13]

Q5: What are the key considerations for implementing a sustainable synthetic data flywheel?

- Establish robust validation checkpoints at each iteration

- Monitor for distribution shift and model collapse

- Maintain archival of original experimental data for reference

- Implement version control for both models and generated datasets

- Develop domain-specific quality metrics beyond statistical similarity [10]

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools and Materials

Table: Key Research Reagents for Synthetic Data Generation in Materials Science

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Generative Models | Con-CDVAE, GANs, VAEs, Diffusion Models | Generate synthetic material structures with target properties through deep learning approaches [10] [7] |

| Property Predictors | CGCNN, SchNet, MEGNet | Predict material properties from structure for validation and pseudo-label generation [10] |

| Simulation Platforms | MATLAB, ANSYS, COMSOL Multiphysics | Process-driven synthetic data generation through physics-based simulations [13] |

| Material Databases | Matminer, Materials Project, Jarvis | Source of training data and benchmarking for generative models [10] |

| Programming Frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch, synthpop R package | Core infrastructure for implementing and customizing generative algorithms [13] [14] |

| Validation Suites | Pymatgen, ASE, RDKit | Validate synthetic materials for structural stability, chemical validity, and physical properties [10] [13] |

Synthetic Data Generation Decision Framework

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

Table: Experimental Results of Synthetic Data Augmentation in Materials Science [10]

| Dataset & Condition | Training Only on Real Data | Training Only on Synthetic Data | Combined Real + Synthetic Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jarvis2D Exfoliation (Fully-Supervised) | 62.01 ± 12.14 | 64.52 ± 12.65 | 57.49 ± 13.51 |

| Jarvis2D Exfoliation (Semi-Supervised) | 64.03 ± 11.88 | 64.51 ± 11.84 | 63.57 ± 13.43 |

| MP Poly Total (Fully-Supervised) | 6.33 ± 1.44 | 8.13 ± 1.52 | 7.21 ± 1.30 |

| MP Poly Total (Semi-Supervised) | 8.08 ± 1.53 | 8.09 ± 1.47 | 8.04 ± 1.35 |

Note: Performance measured as Mean Absolute Error (lower values indicate better performance). Results demonstrate that synthetic data provides maximum benefit in data-scarce scenarios and for certain material properties.

For researchers in materials science and drug development, synthetic data has emerged as a critical tool for overcoming the persistent challenges of data scarcity, high annotation costs, and privacy restrictions [15] [10]. In the context of materials research, high-quality synthetic data is no longer an experimental luxury but an operational necessity for scaling AI responsibly [15]. The efficacy of predictive models for material property prediction or molecular design hinges on the quality of the synthetic data used for training, which is defined by three core characteristics: accuracy, diversity, and realism [16]. This technical support guide provides troubleshooting and best practices to help you ensure your synthetic data possesses these characteristics.

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

How do I evaluate the accuracy of my synthetic materials data?

Answer: Accuracy measures how closely the synthetic dataset matches the statistical characteristics of the real dataset it represents [15] [16]. A lack of accuracy can lead to models that fail to predict real-world material properties.

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: The summary statistics (e.g., mean, standard deviation) of your synthetic data differ significantly from your real data.

- Problem: Your model, trained on synthetic data, performs poorly when making predictions on real-world hold-out data.

- Problem: Correlations between key variables (e.g., between atomic structure and formation energy) are not preserved.

- Solution: Calculate correlation matrices for both real and synthetic datasets and compare them. Use this analysis to refine the conditional parameters of your generative model [18].

Experimental Protocol for Assessing Accuracy:

- Hold-out Data: Before generation, split your real dataset into a training set (for generating the synthetic data) and a completely locked-away test set.

- Statistical Comparison: Calculate the metrics listed in Table 1 for your synthetic data against the training portion of your real data.

- Model Utility Test: Train a standard property prediction model (e.g., CGCNN [10]) on your synthetic data. Then, test its performance on the locked-away test set of real data.

- Benchmark: Compare this performance against a model trained directly on the real training data.

My synthetic dataset lacks diversity and does not generalize well. How can I improve it?

Answer: Diversity assesses whether the synthetic data covers a wide range of scenarios and edge cases [15]. A lack of diversity results in models that cannot handle rare or underrepresented material types or conditions.

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: The generative model produces data with low variance, clustering around common cases and missing rare but critical edge cases (e.g., materials with exotic crystal structures).

- Solution: Adjust the sampling strategy of your generative model. Use techniques like kernel density estimation (KDE) on the training data's distribution to guide the sampling of conditional inputs, ensuring a broader exploration of the data space [10].

- Problem: The synthetic data fails to cover the full range of values (e.g., property ranges, atomic counts) present in the original data.

- Problem: The data is not sufficiently "novel" and may simply memorize or slightly alter real training samples.

- Solution: Evaluate the Row Novelty privacy metric [16]. A well-designed generative model should produce new, unique data points that were not in the training set.

Experimental Protocol for Assessing Diversity:

- Range and Category Coverage: For continuous features (e.g., formation energy), calculate the Range Coverage. For categorical features (e.g., space groups), calculate the Category Coverage and Missing Category Coverage [17].

- Visualization: Use dimensionality reduction techniques like t-SNE or PCA to plot both real and synthetic data points in a 2D space. A diverse synthetic dataset should cover a similar area as the real data without significant gaps.

- Novelty Check: Compute the percentage of synthetic data records that are exact matches to records in the training data. This value should be very low or zero [16].

How can I ensure the synthetic data is realistic enough for my scientific domain?

Answer: Realism focuses on how convincingly the synthetic data mimics real-world information, ensuring that models can generalize effectively [15]. It is about the plausibility and coherence of the generated data from a domain expert's perspective.

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: The synthetic data passes statistical tests but generates physically impossible or implausible materials (e.g., unrealistic bond lengths, unstable crystal structures).

- Solution: Incorporate expert review into your validation loop [19]. Domain scientists should manually inspect a sample of the generated data to identify subtleties that statistical metrics miss.

- Problem: The generative model misses complex, non-linear relationships between variables that are fundamental to your field.

- Problem: The data looks "blurry" or lacks the fine-grained detail of real data, a common issue in image-based data like microscopy or spectroscopy.

Experimental Protocol for Assessing Realism:

- Expert Evaluation: Create a set of data samples mixing real and synthetic data. Ask domain experts to identify which is which. If they cannot reliably distinguish them, the synthetic data is highly realistic [19].

- Model-Based Discrimination: Train a discriminative model (a classifier) to distinguish between real and synthetic data. If the classifier performs no better than random chance (50% accuracy), the synthetic data is highly realistic [18].

What are the best practices to avoid bias in my generated datasets?

Answer: Poorly designed generators can reproduce or even exaggerate existing biases in the training data [15]. This can lead to models that are unfair and perform poorly for certain sub-populations of materials.

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: The training data underrepresents a specific class of materials (e.g., a particular crystal system), and the synthetic data fails to correct this.

- Solution: Intentionally oversample the underrepresented classes during the training of the generative model or use algorithms designed for bias mitigation [21].

- Problem: The generative model itself introduces new biases due to its architecture or learning process.

- Solution: Conduct regular bias audits [19]. Analyze the distribution of synthetic data across different sensitive attributes and compare it to the real-world distribution you are trying to model.

- Problem: The model trained on synthetic data performs well on average but fails for specific, rare material types.

- Solution: Blend synthetic data with real data. Start with a real dataset as a seed and use synthetic generation primarily to expand edge cases or cover underrepresented classes [15].

Quantitative Evaluation Metrics

To systematically evaluate your synthetic data, use the following metrics, which are categorized by the core characteristic they measure.

Table 1: Metrics for Evaluating Synthetic Data Quality

| Characteristic | Metric Name | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) Test [17] [18] | Measures the similarity between continuous data distributions. | Value range [0,1]. Higher values indicate closer distribution matching [17]. |

| Total Variation Distance [17] | Measures the similarity between categorical data distributions. | Value range [0,1]. Higher values indicate closer distribution matching [17]. | |

| Prediction Score (TSTR) [16] [18] | Performance (e.g., MAE, R²) of a model trained on synthetic data and tested on real data. | Scores closer to a model trained on real data indicate higher accuracy/utility. | |

| Diversity | Range Coverage [17] | Validates if continuous features stay within the min-max range of the real data. | Value range [0,1]. Higher values indicate better coverage of the original data range [17]. |

| Category Coverage [17] | Measures the representativeness of categorical features in the synthetic data. | Value range [0,1]. Higher values indicate all categories are represented. | |

| Row Novelty [16] | Assesses if the synthetic data contains new, unique records not present in the training set. | Higher scores are better, indicating the data is novel and not just memorized. | |

| Realism | Correlation Preservation [18] | Measures how well inter-variable correlations from the real data are maintained. | Correlation matrices should be similar. High similarity indicates realistic relationships. |

| Expert Review [19] | Qualitative assessment by domain experts on the plausibility of synthetic samples. | Inability to distinguish synthetic from real is the goal. A critical, human-in-the-loop check. |

Experimental Workflow for Synthetic Data Generation and Validation

The following diagram illustrates a robust, iterative workflow for generating and validating high-quality synthetic data, specifically tailored for a materials research context.

Synthetic Data Validation Workflow

This table details key computational tools and reagents used in the generation and validation of synthetic data for materials science.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Synthetic Data Generation

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Synthetic Data |

|---|---|---|

| Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [20] [21] | Deep Learning Model | A framework with a generator and discriminator in adversarial training to produce highly realistic data samples. Variants like CTGAN are for tabular data. |

| Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) [10] [20] | Deep Learning Model | A probabilistic model that learns a latent representation of data and can generate new, diverse samples from this space. Often used for molecular structures. |

| Con-CDVAE [10] | Deep Learning Model | A conditional generative model specifically designed for crystal structures. It generates materials conditioned on target properties. |

| Diffusion Models [20] | Deep Learning Model | A robust method that generates data by iteratively denoising noise. Excels at capturing complex temporal and spatial dependencies. |

| CGCNN [10] | Predictive Model | A graph convolutional neural network for property prediction of crystal structures. Used in TSTR utility testing. |

| Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test [17] [18] | Statistical Metric | A fidelity metric to compare continuous distributions between real and synthetic data. |

| Matminer [10] | Materials Database | A platform for accessing and featurizing real materials data, which can serve as the seed for generating synthetic datasets. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most effective techniques to accelerate the training of AI models for materials research? Techniques like hyperparameter optimization, model pruning, and quantization are highly effective for accelerating AI training [22]. Hyperparameter optimization systematically finds the best configuration settings for the learning process, while pruning removes unnecessary connections in neural networks to reduce computational load [22]. Quantization converts model parameters from high-precision (e.g., 32-bit) to lower-precision (e.g., 8-bit) formats, shrinking model size and increasing inference speed without significant accuracy loss [22]. For materials research, leveraging pre-trained models and transfer learning can dramatically reduce the computational cost and data required to train accurate models for new material systems [23].

Q2: How can synthetic data overcome the challenge of researching rare material properties? Synthetic data is algorithmically generated to mimic the statistical properties of real-world data without containing any actual measurements [2]. It is particularly valuable for studying rare material properties or extreme conditions that are dangerous, costly, or impossible to measure directly in a lab [23] [24]. Using methods like Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and other generative models, researchers can create vast, diverse datasets that include rare events and edge cases [3] [1]. This provides sufficient data to train robust AI models that can predict material behavior under rare conditions [2] [1].

Q3: My AI model performs well on synthetic data but poorly on real experimental data. What could be wrong? This common issue often points to a fidelity gap between your synthetic and real data [2]. The synthetic data may not fully capture the complexity, noise, or underlying physical relationships present in the real world. To address this:

- Evaluate Data Quality: Use statistical tests (e.g., Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests) and domain expert validation to ensure the synthetic data's statistical properties and relationships match the real data closely [1].

- Check for Bias: Ensure your synthetic data generation process does not amplify biases present in a small original dataset. Use sampling techniques to create balanced datasets [2].

- Task-Specific Efficacy Testing: Don't just evaluate the data in isolation. Always test the efficacy of your synthetic data for the specific modeling task at hand to ensure it leads to valid conclusions [2].

Q4: Which specialized hardware can speed up both AI training and molecular simulations? While GPUs are versatile for both AI and simulation workloads, specialized non-GPU accelerators can offer superior performance for specific tasks [25].

- AI Training: Google's TPUs (Tensor Processing Units) and AWS Trainium chips are designed from the ground up for high-throughput training of machine learning models [25].

- Molecular Simulations: The article does not provide a direct example of hardware for molecular simulations. However, the Conesus supercomputer, optimized for large-scale physics simulations, exemplifies the type of High-Performance Computing (HPC) infrastructure used for such tasks, featuring parallel processing power to run multi-dimensional models [24].

- Inference at Scale: For deploying trained models, specialized inference Application-Specific Integrated Circuits (ASICs) often outperform GPUs in throughput and power efficiency [25].

Q5: What is a Neural Network Potential (NNP) and how does it improve materials simulation? A Neural Network Potential (NNP) is a machine learning model that learns the relationship between atomic structures and their potential energy, allowing for molecular dynamics simulations with near-DFT (Density Functional Theory) accuracy but at a fraction of the computational cost [23]. This makes it possible to simulate large systems and long timescales that are prohibitively expensive with traditional quantum mechanical methods. For example, the EMFF-2025 model is a general NNP for C, H, N, O-based high-energy materials that can predict structures, mechanical properties, and decomposition characteristics with high accuracy [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Slow AI Model Training Times Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Suboptimal Hyperparameters | Use automated optimization tools like Optuna or Ray Tune to efficiently search for the best learning rate, batch size, etc. [22]. |

| Overly Complex Model | Apply pruning to remove redundant weights and quantization to reduce numerical precision, creating a smaller, faster model [22]. |

| Inefficient Data Pipeline | Ensure your data is preprocessed and fed to the model efficiently. Techniques like data augmentation should be optimized to not become a bottleneck. |

| Insufficient Hardware Acceleration | Leverage specialized AI accelerators like GPUs with tensor cores, TPUs, or other ASICs designed for high-throughput matrix operations [25] [26]. |

Problem: Synthetic Data Lacks Realism for Target Material Property Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Poor Underlying Generative Model | Move beyond simple statistical models. Use more powerful generators like GANs or Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) that can capture complex, non-linear relationships in the original data [3] [1]. |

| Insufficient or Low-Quality Seed Data | The generative model is only as good as the data it's trained on. Start with the highest-quality, most representative real data you can acquire, even if the volume is small [1]. |

| Ignored Physical Constraints | Incorporate known physical laws or domain knowledge into the data generation process to ensure the synthetic data is not just statistically similar but also physically plausible. |

| Lack of Diversity in Generated Data | Calibrate your generation algorithm to produce a wide range of scenarios, including rare events and edge cases, to prevent bias and improve model robustness [1]. |

Problem: High Error in Neural Network Potential (NNP) Predictions Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Inadequate Training Data Coverage | The training set must encompass a wide range of atomic configurations and energies that the model is expected to see during simulations. Use active learning or a framework like DP-GEN to intelligently sample new configurations and expand the training database [23]. |

| Extrapolation Beyond Training Domain | NNPs are unreliable when predicting properties for structures far outside their training domain. Always check that the system's state (e.g., temperature, pressure) during simulation falls within the validated range of the NNP [23]. |

| Insufficient Model Transfer Learning | For new material systems, do not rely solely on a general pre-trained model. Use transfer learning by fine-tuning the model with a small amount of high-quality, system-specific DFT data [23]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: Performance Comparison of AI Inference Frameworks on Edge Hardware (NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin) [27] This table helps select the right framework for deploying trained models, a key step in the research workflow.

| Framework | Primary Use Case | Key Strengths | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PyTorch | Prototyping, Research | Exceptional flexibility, ease of use, rapid iteration | Not inherently optimized for production inference on embedded systems [27]. |

| ONNX Runtime | Cross-Platform Deployment | High portability across hardware, supports multiple execution providers | Performance can be dependent on the selected hardware backend [27]. |

| TensorRT | High-Performance Inference (NVIDIA) | Delivers superior inference speed and throughput on NVIDIA hardware | Increased deployment complexity, vendor-locked to NVIDIA ecosystem [27]. |

| Apache TVM | Hardware-Agnostic Optimization | Compiles models for diverse hardware targets, good performance | Requires more tuning and expertise to use effectively [27]. |

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of Model Optimization Techniques [22] This table summarizes the potential benefits of applying optimization techniques to AI models.

| Optimization Technique | Typical Model Size Reduction | Typical Inference Speedup | Key Trade-Off |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pruning | Varies (removes redundant weights) | Significant (less computation) | Potential small loss in accuracy, requires fine-tuning [22]. |

| Quantization | Up to 75% (32-bit to 8-bit) | 2-3x (faster memory access/compute) | Minor accuracy loss, managed with quantization-aware training [22]. |

| Knowledge Distillation | Varies (smaller student model) | Varies (smaller model) | Student model capacity must be sufficient to learn from teacher [22]. |

Workflow Diagrams

Synthetic Data for Materials Research Workflow

Neural Network Potential for Material Property Prediction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for AI-Accelerated Materials Research

| Tool / Solution | Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) | Generates high-fidelity synthetic data that mimics complex real-world distributions [3]. | Creating synthetic molecular structures or spectral data to augment limited experimental datasets. |

| Synthetic Data Vault (SDV) | An open-source Python library for generating synthetic tabular data for testing and ML training [2]. | Creating privacy-preserving versions of sensitive experimental data for sharing and collaboration. |

| Neural Network Potential (NNP) | Provides a fast, accurate force field for molecular dynamics simulations at near-DFT accuracy [23]. | Simulating the thermal decomposition of a high-energy material over long timescales. |

| Transfer Learning | Leverages knowledge from a pre-trained model to solve a new, related problem with minimal data [23]. | Fine-tuning a general NNP on a specific class of polymers using a small set of targeted DFT calculations. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Provides the massive parallel processing power needed for large-scale simulations and AI model training [24]. | Running thousands of parallel molecular dynamics simulations to scan a vast compositional space of alloys. |

Advanced Generation Techniques: From Statistical Models to Generative AI

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Problems & Solutions

My generative model produces physically unrealistic materials. What should I check? This often stems from the model learning incorrect structure-property relationships. First, verify your training data for quality and coverage. The dataset must be large and diverse enough to capture the complex process-structure-property (PSP) linkages of real materials [28]. Second, review your model's constraints. Using a tool like SCIGEN to enforce specific geometric or symmetry constraints during generation can guide the model to create materials with more plausible, target-oriented structures, such as Kagome lattices for quantum properties [29].

I am concerned about the privacy and bias in my synthetic dataset. How can I address this? Synthetic data is valued for being privacy-preserving, as it doesn't contain real-world information. However, biases in the original data can carry over [2]. To mitigate this:

- Evaluate Bias Proactively: Use statistical tests to check if your synthetic data over-represents certain material classes or properties. Intentionally calibrate your data generation to create balanced datasets [2].

- Assess Privacy: Employ metrics from libraries like the Synthetic Data Metrics Library to measure the risk of reconstructing sensitive information from your synthetic dataset [2].

- Use Hybrid Data: Consider a partially synthetic data approach, where only sensitive fields are generated, to better preserve overall data utility and authenticity [1].

My generative model's output lacks diversity and keeps producing similar structures. How can I fix this? This problem, known as "mode collapse," occurs when a generative model fails to capture the full diversity of the training data. For materials science, this limits the exploration of novel chemical spaces [30].

- For GANs: This is a known challenge. Experiment with different GAN architectures designed to improve stability and diversity, or adjust training parameters [3] [30].

- Explore Alternative Models: Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) or the newer diffusion models (like MatterGen) can sometimes offer better exploration of the latent space, leading to more diverse outputs [30] [31].

- Data Augmentation: If your original dataset is small, use data augmentation techniques to introduce more variety, which can help the model learn a broader distribution of patterns [1].

How do I know if my synthetic materials data is high-quality? Evaluating synthetic data requires a multi-faceted approach focusing on fidelity, utility, and privacy [2].

- Statistical Fidelity: Compare the statistical properties (distributions, correlations) of your synthetic data with the original, real-world data using established tests [1].

- Expert Validation: Have domain experts assess whether the generated materials and their properties are realistic and representative of the target phenomena [1].

- Downstream Task Performance (Utility): The most critical test is using the synthetic data for its intended purpose. Train a machine learning model on your synthetic data and test its performance on a held-out set of real data. If performance is similar to a model trained on real data, your synthetic data has high utility [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the core difference between screening databases and using generative AI for materials discovery? Screening methods (like high-throughput virtual screening) are limited to evaluating and filtering existing materials within a known database. In contrast, generative AI can create completely novel materials that have never been seen before, allowing exploration of a much larger chemical space [31]. As one researcher noted, "We don’t need 10 million new materials to change the world. We just need one really good material," which generative AI is well-suited to find [29].

When should I use a VAE over a GAN for generating materials data? The choice often depends on the trade-off between stability and diversity.

- Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) are typically more stable to train and provide a structured latent space that can be useful for optimization. However, they can sometimes generate blurrier or less precise outputs [30].

- Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) can produce very sharp and realistic data but are notoriously difficult to train and prone to mode collapse, where the generator fails to capture the full data diversity [30]. Newer architectures like diffusion models (e.g., MatterGen) are also emerging as powerful alternatives that can generate high-quality, diverse materials [31].

What are the main data-related challenges in materials informatics? The primary challenges are data scarcity, veracity, and integration [32] [28] [33]. Sourcing sufficient high-quality data from experiments or simulations is expensive and time-consuming. Data is often sparse, noisy, and locked in legacy formats or siloed databases. Furthermore, integrating experimental and computational data remains a significant hurdle [32] [33].

Can I use synthetic data for validating new materials without any real-world experiments? No. While synthetic data and AI models are powerful for rapid exploration and hypothesis generation, physical experimentation remains the ultimate validation step [29] [31]. For instance, the novel material TaCr2O6, generated by MatterGen, had to be synthesized in a lab to confirm its predicted structure and properties, which showed a close but not perfect match to the AI's prediction [31]. AI accelerates discovery, but experimentation confirms it.

Comparison of Synthetic Data Generation Methods

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of prominent generation methods to help you select the most appropriate one for your research goal.

| Method | Key Principle | Best Suited For | Key Advantages | Common Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [3] [30] | Two neural networks (generator & discriminator) compete to produce realistic data. | Generating high-fidelity, complex data like crystal structures and microstructural images. | Can produce very realistic and sharp data outputs. | Training can be unstable; prone to mode collapse. |

| Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) [30] | Encodes data into a latent distribution, then decodes to generate new data points. | Exploring a continuous latent space of materials for optimization and inverse design. | More stable training; provides a structured, interpretable latent space. | Generated data can be less detailed or "blurry" compared to GANs. |

| Diffusion Models [29] [31] | Iteratively refines a noisy structure into a coherent material through a reverse process. | Generating novel and diverse 3D crystal structures with targeted properties. | State-of-the-art performance in generating novel, stable, and diverse materials. | Computationally intensive due to the multi-step generation process. |

| Rule-Based Generation [1] | Uses predefined physical rules or constraints to create data. | Generating data that must adhere to strict physical laws or geometric constraints (e.g., lattice symmetries). | Highly interpretable and guarantees data conforms to specified rules. | Requires extensive domain knowledge; cannot discover rules outside its programming. |

Experimental Protocol for Validating Generative Models

This protocol outlines the steps for computationally and experimentally validating a generative model for inorganic materials, based on methodologies used in recent breakthroughs [29] [31].

1. Objective: To validate a generative AI model's ability to produce novel, stable materials with target properties.

2. Materials & Computational Resources:

- Generative Model: A pre-trained model (e.g., DiffCSP, MatterGen) or a custom-built VAE/GAN [29] [31].

- Training Data: A curated database of known stable materials (e.g., from the Materials Project or Alexandria) for training or benchmarking [31].

- Validation Software: Density Functional Theory (DFT) software (e.g., VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO) for stability and property calculations [28].

- High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster: Access to supercomputing resources for running large-scale DFT validations [29].

3. Method:

- Step 1: Conditional Generation. Use the generative model, potentially augmented with a constraint tool like SCIGEN, to produce candidate materials based on a target prompt (e.g., "high bulk modulus" or "Kagome lattice") [29] [31].

- Step 2: Stability Screening. Apply a filter to the generated candidates to select only those that are predicted to be thermodynamically stable.

- Step 3: Property Prediction. Run DFT calculations on the stable candidates to verify their target properties (e.g., electronic band structure, magnetic moments, bulk modulus) [29].

- Step 4: Synthesis & Experimental Validation. Select the most promising candidates for lab synthesis. For example, solid-state reaction methods can be used to synthesize novel oxides [31].

- Step 5: Characterization. Use techniques like X-ray diffraction (XRD) to confirm the crystal structure and other relevant experiments to measure the target properties, comparing the results with AI predictions [31].

Workflow Diagram for Generative Materials Discovery

The diagram below illustrates the integrated workflow of using generative AI, simulation, and experimentation to discover new materials.

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key computational tools and data resources that are essential for conducting generative materials science research.

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| MatterGen [31] | Generative AI Model | A diffusion model designed to generate novel, stable 3D material structures conditioned on property prompts (e.g., chemistry, magnetism). |

| SCIGEN [29] | AI Constraint Tool | A method to steer generative AI models to produce materials that adhere to specific geometric or structural constraints essential for quantum properties. |

| Synthetic Data Vault (SDV) [2] | Synthetic Data Platform | An open-source platform for generating synthetic data, particularly useful for creating structured (tabular) data while preserving privacy. |

| Materials Project [31] | Materials Database | A large, open database of computed materials properties that serves as a primary source of training data for many generative models. |

| DFT Software (VASP, etc.) [28] | Simulation Software | Density Functional Theory software used for high-throughput virtual screening to validate the stability and properties of AI-generated candidates. |

Leveraging Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) for Complex Material Structures

GAN Troubleshooting Guide: Common Problems & Solutions

This guide addresses frequent challenges encountered when training GANs for materials science applications, providing targeted solutions to improve synthetic data quality.

### FAQ 1: My generator produces low-diversity, repetitive structures. How can I address this mode collapse?

- Problem Explanation: Mode collapse occurs when the generator learns to produce a limited set of plausible outputs, failing to capture the full diversity of the real material structures. It over-optimizes for a specific discriminator state, leading to non-diverse or repetitive synthetic data [34].

- Diagnosis Check: Assess if your generator produces very similar material phases or morphologies across different random input vectors. Quantitatively, this may manifest as low variance in descriptor values across generated samples.

- Recommended Solutions:

- Use Wasserstein Loss with Gradient Penalty (WGAN-GP): This loss function provides more stable training and better gradient information, discouraging the generator from converging to a single mode [34].

- Implement Mini-batch Discrimination: This allows the discriminator to assess an entire batch of samples, making it harder for the generator to succeed by producing only a few types of outputs.

- Try Unrolled GANs: These optimize the generator considering future states of the discriminator, preventing over-optimization for a single discriminator instance [34].

### FAQ 2: My model training is highly unstable and fails to converge. What stabilization techniques can I apply?

- Problem Explanation: GAN training is a minimax game where the generator (G) and discriminator (D) have competing objectives. An imbalance can lead to oscillating losses and failure to find a stable equilibrium (Nash equilibrium) [35] [34].

- Diagnosis Check: Monitor the loss curves for both networks. Persistent oscillation or one network's loss crashing to zero while the other increases are strong indicators of training instability.

- Recommended Solutions:

- Apply Gradient Penalty Regularization: This penalizes the discriminator's gradient norm, preventing it from becoming too powerful too quickly and overwhelming the generator [34].

- Add Noise to Discriminator Inputs: Introducing noise to the real and fake data inputs of the discriminator can stabilize training [34].

- Use Spectral Normalization: This technique constrains the Lipschitz constant of the discriminator, a key factor for stable training, especially with Wasserstein loss [36].

- Balance Training: Ensure neither network becomes too strong. A common strategy is to train the discriminator for multiple steps for every single generator update.

### FAQ 3: The discriminator becomes too accurate too quickly, halting generator progress. How can I fix vanishing gradients?

- Problem Explanation: An optimal discriminator can saturate and provide zero gradients, leaving the generator with no meaningful signal to learn from. This is known as the vanishing gradients problem [34].

- Diagnosis Check: If the discriminator accuracy quickly reaches near 100% while the generator loss fails to decrease, the generator is likely receiving vanishing gradients.

- Recommended Solutions:

- Switch to Wasserstein Loss: This loss is designed to prevent vanishing gradients even when training the discriminator to optimality, as it provides a linear gradient that helps the generator learn [34].

- Modify the Loss Function: Use alternative loss functions like Least Squares GAN (LSGAN) or Hinge loss, which can offer more robust gradient behavior compared to the original minimax loss [35].

- Adjust Network Capacity: If the discriminator is too large or powerful relative to the generator, consider reducing its capacity to prevent it from becoming too accurate too fast [36].

### FAQ 4: How can I quantitatively evaluate if my synthetic material data is high-quality and useful?

- Problem Explanation: Assessing the fidelity and diversity of generated data is crucial for scientific applications. Unlike images, material data often requires domain-specific metrics [37].

- Recommended Evaluation Protocol:

- Distribution Similarity: Use statistical measures like the Hellinger distance or Jensen-Shannon divergence to compare the distributions of key material descriptors (e.g., lattice parameters, phase fractions) between real and synthetic datasets. A smaller distance indicates better distribution matching [37].

- Utility Test (TSTR - Train on Synthetic, Test on Real): Train a predictive model (e.g., for a property like bandgap or strength) entirely on your synthetic data. Then, test its performance on a held-out set of real data. High performance indicates the synthetic data captures the critical structure-property relationships of the real data [37].

- Discriminative Test (TRTS - Train on Real, Test on Synthetic): Train a classifier to distinguish between real and synthetic data. A high classification accuracy suggests the synthetic data is easily distinguishable, indicating lower quality [37].

- Propensity Score MSE: Train a model to predict whether a data sample is real or synthetic. A low Mean Squared Error (close to 0.25 for a balanced dataset) suggests the two are indistinguishable [37].

Quantitative Evaluation Metrics for Synthetic Material Data

The table below summarizes key metrics for assessing synthetic data quality in materials research.

| Metric Name | Optimal Value | Interpretation in Materials Context | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hellinger Distance [37] | Close to 0 | Measures similarity in the distribution of a single material feature (e.g., porosity). Lower values indicate better match. | In a medical data study, most variables had Hellinger distances < 0.1, indicating high similarity [37]. |

| TSTR AUC [37] | Close to 1.0 | Tests the practical utility of synthetic data. A high value means models trained on synthetic data perform well on real data. | A study on colorectal cancer data achieved a TSTR AUC of 0.99, showing high utility [37]. |

| TRTS AUC [37] | Close to 0.5 | Tests the discriminability of synthetic data. A value near 0.5 means a model cannot tell real and synthetic data apart. | The same medical study reported a TRTS AUC of 0.98, indicating the data was slightly distinguishable [37]. |

| Propensity MSE [37] | Close to 0.25 | Measures how indistinguishable the datasets are. A value of 0.25 suggests perfect indistinguishability. | A propensity MSE of 0.223 was reported, close to the ideal value [37]. |

Experimental Protocol for Validating GAN-Generated Material Data

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for a rigorous evaluation of synthetic material data, based on established practices [37].

Objective: To validate that a GAN generates high-quality, diverse, and useful synthetic data representing complex material structures.

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Split your real material dataset (e.g., from microscopy or simulations) into a Training Set (for GAN training) and a Held-Out Test Set (for final validation).

- Preprocess the data (e.g., normalization, feature scaling).

Model Training & Synthesis:

- Train your GAN model (e.g., RTSGAN for time-series data [37]) exclusively on the Training Set.

- After convergence, use the trained generator to create a Synthetic Dataset of comparable size to the real training set.

Quantitative Evaluation:

- Distributional Similarity: For each key material descriptor, calculate the Hellinger distance between the Synthetic Dataset and the real Training Set.

- Utility Test (TSTR):

- Train a property prediction model (e.g., a regressor for Young's Modulus) on the Synthetic Dataset.

- Evaluate the model's performance (e.g., AUC, MAE) on the real Held-Out Test Set.

- Discriminative Test (TRTS):

- Train a binary classifier (real vs. synthetic) on the real Training Set and the Synthetic Dataset.

- Evaluate its classification accuracy on the real Held-Out Test Set. Low accuracy is desirable.

- Propensity Score:

- Train a model to predict the data source (real/synthetic) on a combined dataset.

- Calculate the Mean Squared Error between the predictions and the balanced prior (0.5). An MSE near 0.25 is ideal [37].

Qualitative Evaluation:

GAN Validation Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for GANs in Materials Science

This table lists key computational "reagents" essential for developing and validating GANs in this domain.

| Tool / Technique | Function | Application Example in Materials Science |

|---|---|---|

| Wasserstein GAN with Gradient Penalty (WGAN-GP) [34] | Loss function that stabilizes training and mitigates mode collapse and vanishing gradients. | Generating diverse and novel crystalline structures in inverse design tasks [38]. |

| Real-world Time-Series GAN (RTSGAN) [37] | A GAN variant designed to handle real-world time-series data, common in processing and degradation studies. | Synthesizing combined time-series and static medical data; can be adapted for material aging or in-situ measurement data [37]. |

| t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) [37] | A non-linear dimensionality reduction technique for qualitative visualization of high-dimensional data. | Visualizing the latent space of generated materials to check for cluster overlap with real data and diversity [37]. |

| Hellinger Distance [37] | A quantitative metric to measure the similarity between two probability distributions. | Comparing the distribution of a specific material property (e.g., particle size) between real and synthetic datasets [37]. |

| Train on Synthetic, Test on Real (TSTR) [37] | An evaluation protocol that tests the practical utility of synthetic data for downstream tasks. | Training a property predictor on synthetic microstructures and testing its accuracy on real, held-out data [37] [38]. |

| Spectral Normalization [36] | A regularization technique applied to the discriminator to constrain its Lipschitz constant, promoting training stability. | Used in various modern GAN architectures (e.g., StyleGAN) to enable stable training on high-resolution material image data. |

Applying Diffusion Models and Variational Autoencoders (VAEs)

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the role of a VAE in a Stable Diffusion model, and why is it crucial for generating high-quality synthetic data?

The Variational Autoencoder (VAE) is a critical component in Stable Diffusion that acts as a bridge between pixel space and a lower-dimensional latent space. It consists of an encoder and a decoder [39]. The encoder compresses input images into a latent representation, while the decoder reconstructs images from this latent space [39]. In materials research, this is crucial because it allows for more efficient and stable generation of complex material structures by working in a compressed, meaningful representation, reducing computational resources and improving the coherence of generated data [39].

FAQ 2: My generated images appear washed out and lack detail. How can a VAE fix this?

A washed-out appearance is a common issue that a VAE can directly address. VAEs are known for enhancing image quality by enriching outputs with vibrant colors and sharper details [40]. By using a dedicated VAE, you can significantly improve the color saturation and definition of your generated material morphologies and microstructures, making the synthetic data more visually accurate and useful for analysis [40].

FAQ 3: I am encountering a "CUDA out of memory" error during image generation. What steps can I take to resolve this?

This error typically occurs when the GPU's memory is exhausted, especially with large image sizes or complex models [41]. You can mitigate this by:

- Reducing VRAM Usage: Lower the "VRAM Usage Level" in your application settings [41].

- Disabling Shared Memory: For users with NVIDIA drivers version 532+, disable the system RAM shared memory feature in your driver settings, as it can slow down rendering and contribute to memory issues when the GPU memory is almost full [41].

- Closing Applications: Ensure you close other GPU-intensive applications before running your experiments [41].

FAQ 4: What are the best practices for selecting and using a VAE model with my Stable Diffusion checkpoint?

For optimal results:

- Check Compatibility: Always refer to your checkpoint model's specifications, as they often recommend a compatible VAE [40].

- Use Recognized Models: Stability AI has released specific VAE models (e.g.,

sd-vae-ft-emaandsd-vae-ft-mse) that are widely used and reliable [39]. - Streamline Your Workflow: Add the VAE selection to your interface's Quick Settings list for easy access and switching between different models [40].

Troubleshooting Guide

Common Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Washed-out Images | Missing or incorrect VAE model [40]. | Download and select a compatible VAE in the SD VAE settings [39]. |

| CUDA Out of Memory | GPU memory is full due to large image size or high VRAM usage [41]. | Lower the "VRAM Usage Level" in settings; close other applications [41]. |

| Slow Rendering Speed | NVIDIA drivers using system RAM as shared memory [41]. | Disable shared memory behavior in NVIDIA driver settings [41]. |

| Poor Image Coherence | Model instability during the diffusion process. | Utilizing a VAE provides a structured latent space, enhancing output stability and realism [39]. |

Experimental Protocol: Integrating a VAE into Stable Diffusion

Objective: To improve the quality, color vibrancy, and stability of images generated by a Stable Diffusion model for synthetic data creation.

Materials/Reagents:

- A computer with a GPU (minimum 6GB VRAM recommended).

- An installed Stable Diffusion web UI (e.g., AUTOMATIC1111).

- Internet connection for downloading the VAE model.

Methodology:

- Download the VAE Model:

- Obtain the VAE model file. Stability AI provides common models, such as:

vae-ft-ema-560000-ema-pruned.ckptvae-ft-mse-840000-ema-pruned.ckpt[39].

- These are typically safe tensor (

.safetensors) or checkpoint (.ckpt) files.

- Obtain the VAE model file. Stability AI provides common models, such as:

Install the VAE Model:

- Place the downloaded VAE file into the correct directory in your Stable Diffusion installation:

stable-diffusion-webui/models/VAE/[39].

- Place the downloaded VAE file into the correct directory in your Stable Diffusion installation:

Apply the VAE Model:

- a. Open your Stable Diffusion web UI (e.g., AUTOMATIC1111).

- b. Navigate to the Settings tab.

- c. On the left, select Stable Diffusion.

- d. Find the SD VAE section.

- e. From the dropdown menu, select the VAE model you installed.

- f. Click the Apply settings button at the top of the page to save and load the new configuration [39].

Generate Images:

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of a VAE within a Stable Diffusion pipeline for generating high-quality synthetic data.

VAE Integration in Stable Diffusion

Research Reagent Solutions

| Research Reagent | Function |

|---|---|

| Stable Diffusion Checkpoint | The core pre-trained model containing knowledge of visual concepts; the base for image generation. |

| VAE (Variational Autoencoder) | Enhances output image quality, improves color vibrancy, and adds finer details to generated images [40] [39]. |

| Synthetic Data Generation Tool (e.g., Gretel, MOSTLY.AI) | Platforms for generating artificial datasets that mimic real-world data, crucial for training models when real data is scarce or sensitive [1] [3]. |

| Synthetic Data Vault (SDV) | An open-source Python library for generating synthetic tabular data, useful for creating structured material property datasets [1]. |

Implementing Rule-Based Generation and Data Augmentation for Structured Data

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between rule-based generation and other synthetic data techniques for structured materials data?

Rule-based generation creates synthetic datasets by applying a predefined set of business or domain rules that dictate how data points interact, ensuring relationships among various data elements remain intact [1]. This contrasts with generative models like GANs, which learn patterns from existing data. Rule-based approaches are particularly valuable for scenarios where specific conditions or hierarchies must be maintained, such as preserving physical laws in material property relationships [42]. They offer high interpretability and are especially effective for small datasets commonly encountered in novel materials research [43].

Q2: How can I ensure my augmented structured data maintains physical plausibility for materials science applications?

Maintaining physical plausibility requires implementing domain-specific constraints and validation rules. For material microstructure data, this involves ensuring geometric and topological information of synthetic data remains statistically consistent with real materials [44]. Establish mathematical models developed to recreate material properties [42], and validate against known physical laws. Implement rule checks for impossible combinations (e.g., a porosity percentage that would compromise structural integrity) and use domain expert validation to confirm biological or physical plausibility of generated samples [43].

Q3: What are the most effective validation metrics for assessing synthetic data quality in materials research?

Effective validation includes both statistical and domain-specific metrics. Statistical tests like Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) tests should compare distributions between real and synthetic datasets [1]. For materials applications, additionally validate by training identical machine learning models on both real and synthetic data and comparing performance on held-out real test sets [44]. In grain segmentation tasks, models trained with synthetic data and only 35% of real data have achieved competitive performance with models trained on 100% real data [44]. Domain expert assessment remains crucial for evaluating if synthetic data realistically represents the phenomena being modeled [1].

Q4: Can data augmentation address class imbalance in rare disease drug development datasets?

Yes, structured data augmentation specifically helps address class imbalance in rare disease research where patient cohorts are small. Techniques like synthetic minority oversampling (SMOTE) generate new instances for underrepresented classes by interpolating between existing data points [45]. For a rare disease dataset with few positive cases, SMOTE can create synthetic positive samples by combining features of similar real cases while preserving statistical patterns. Rule-based methods also enable targeted generation of rare disease profiles by encoding known disease characteristics as generation rules [43].

Q5: What common pitfalls degrade synthetic data quality in materials informatics, and how can I avoid them?

Common pitfalls include: (1) Introducing unrealistic feature combinations - solved by implementing domain rule validation; (2) Insufficient diversity - ensure synthetic datasets cover edge cases and rare scenarios; (3) Over-reliance on single generation techniques - combine rule-based and generative approaches; (4) Inadequate validation - use both statistical tests and domain expert review [1]. For materials specifically, ensure simulated data incorporates realistic noise and defects present in experimental data rather than perfect theoretical constructs [44].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Synthetic Material Data Lacks Realistic Variability

Symptoms: Machine learning models trained on synthetic data perform poorly on real experimental data; synthetic datasets appear overly uniform compared to real-world observations.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

- Analyze Real Data Distributions: Before generating synthetic data, conduct thorough analysis of original dataset distributions, correlations, and variable relationships [1].

- Incorporate Controlled Noise: Add realistic noise to numerical features using Gaussian noise with small standard deviations while respecting realistic bounds [45]. For material images, integrate realistic noise patterns from experimental setups.

- Combine Generation Techniques: Use hybrid approaches where rule-based generation establishes physical constraints, then generative models add realistic variations [44].

- Validate Variability: Compare variability metrics (variance, entropy) between real and synthetic datasets across multiple scales.

Table: Techniques for Enhancing Synthetic Data Realism in Materials Research

| Technique | Implementation | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Model Integration | Incorporate equations governing material behavior into generation rules | Crystal growth simulation, composite material properties |

| Experimental Noise Injection | Add noise profiles characteristic of measurement instruments | Microscopic image synthesis, spectral data generation |

| Multi-Scale Synthesis | Generate data at different scales (atomic, microstructural, bulk) | Predicting material properties across length scales |

| Defect Introduction | Systematically introduce controlled defects and impurities | Studying material failure mechanisms, quality control |

Issue: Poor Model Generalization from Synthetic to Real Materials Data

Symptoms: High performance on validation splits of synthetic data but significant performance drop when applied to real experimental data; model fails to capture essential patterns in real-world applications.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

- Implement Progressive Validation: Establish a validation pipeline where synthetic data is tested at multiple stages:

- Statistical similarity to training data

- Performance on simplified real-world tasks

- Full application performance with limited real data [44]

- Leverage Style Transfer Techniques: For image-based materials data, use image-to-image conversion to transfer simulated images into synthetic images incorporating features from real images [44].

- Apply Transfer Learning: Pre-train models on large synthetic datasets, then fine-tune with limited real experimental data [44].

- Conduct Ablation Studies: Systematically test which synthetic data components contribute most to real-world performance by training on different synthetic dataset variations.

Issue: Computational Bottlenecks in Rule-Based Data Generation

Symptoms: Synthetic data generation processes take impractically long; difficulty scaling to large dataset requirements; memory constraints with complex rule systems.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

- Optimize Rule Efficiency:

- Profile rules to identify computational bottlenecks

- Implement hierarchical rule processing (apply broad constraints first)

- Use approximate matching for non-critical constraints

- Leverage High-Performance Computing:

- Parallelize independent generation tasks

- Use distributed computing for massive datasets

- Implement GPU acceleration for applicable operations

- Implement Just-in-Time Generation: Rather than generating entire datasets upfront, generate batches during model training.

- Use Hybrid Approaches: Combine lightweight rule-based generation for structure with faster generative models for variations.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Rule-Based Synthesis for Material Microstructure Data

This protocol enables generation of synthetic material microstructure data with physically accurate properties, based on techniques validated in materials informatics research [44].

Research Reagent Solutions:

Table: Essential Components for Material Data Synthesis

| Component | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Monte Carlo Potts Model | Simulates fundamental grain growth physics | 3D polycrystalline microstructure generation [44] |

| Domain Constraint Rules | Encodes physical limits and relationships | Crystallographic rules, phase stability boundaries |

| Style Transfer Model | Adds experimental realism to simulations | GAN-based image transformation [44] |

| Statistical Validation Suite | Verifies synthetic data fidelity | KS-tests, distribution comparison metrics [1] |