Beyond Prediction: A Practical Framework for Experimentally Validating Synthesizability in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating computational synthesizability predictions with experimental synthesis data.

Beyond Prediction: A Practical Framework for Experimentally Validating Synthesizability in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating computational synthesizability predictions with experimental synthesis data. It explores the critical gap between in-silico models and laboratory reality, covering foundational concepts, advanced methodologies like positive-unlabeled learning and large language models, and practical optimization techniques. The content details robust validation frameworks, including statistical and machine learning-based checks, and presents comparative analyses of leading tools. By synthesizing key takeaways, the article aims to equip scientists with a actionable strategy to enhance the reliability of synthesizability assessments, ultimately accelerating the transition of novel candidates from computer to clinic.

The Synthesizability Gap: Why Computational Predictions Fail in the Lab

The accelerating pace of computational materials design has revealed a critical bottleneck: the transition from predicting promising compounds to experimentally realizing them. While high-throughput screening and generative artificial intelligence can explore millions of hypothetical materials, identifying which candidates are synthetically accessible remains a fundamental challenge [1]. The concept of "synthesizability" thus represents a complex multidimensional problem extending far beyond traditional thermodynamic stability considerations. Synthesizability encompasses whether a material is synthetically accessible through current experimental capabilities, regardless of whether it has been synthesized yet [2]. This definition acknowledges that many potentially synthesizable materials may not yet have been reported in literature, while also recognizing that some metastable materials outside thermodynamic stability boundaries can indeed be synthesized through kinetic control.

Traditional approaches to predicting synthesizability have relied heavily on computational thermodynamics, particularly density-functional theory (DFT) calculations of formation energy and energy above the convex hull. However, these methods capture only one aspect of synthesizability, failing to account for kinetic stabilization, synthetic pathway availability, precursor selection, and human factors such as research priorities and equipment availability [2]. This limitation is quantitatively demonstrated by the poor performance of formation energy calculations in distinguishing synthesizable materials, capturing only 50% of known inorganic crystalline materials [2]. Similarly, the commonly employed charge-balancing heuristic, while chemically intuitive, proves insufficient—only 37% of synthesized inorganic materials are charge-balanced according to common oxidation states [2].

This guide systematically compares emerging data-driven approaches that address these limitations, providing researchers with objective performance comparisons and detailed methodological protocols to inform synthesizability prediction in materials discovery campaigns.

Computational Methods for Synthesizability Prediction

Performance Benchmarking

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

| Method | Underlying Approach | Input Requirements | Reported Accuracy | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamic Stability (DFT) | Formation energy & energy above convex hull [3] | Crystal structure | 74.1% (formation energy) [3] | Strong theoretical foundation; well-established | Misses metastable phases; computationally expensive |

| Charge Balancing | Net neutral ionic charge based on common oxidation states [2] | Chemical composition only | 37% of known materials are charge-balanced [2] | Computationally inexpensive; intuitive | Overly simplistic; poor performance (23% for binary cesium compounds) [2] |

| SynthNN [2] | Deep learning with atom embeddings | Chemical composition only | 7× higher precision than DFT; 1.5× higher precision than human experts [2] | Composition-only input; efficient screening of billions of candidates | Cannot differentiate between polymorphs |

| CLscore Model [4] | Graph convolutional neural network with PU learning | Crystal structure | 87.4% true positive rate [4] | Captures structural motifs beyond thermodynamics | Requires structural information |

| CSLLM Framework [3] | Fine-tuned large language models | Text-represented crystal structure | 98.6% accuracy [3] | Highest accuracy; predicts methods and precursors | Requires substantial data curation |

Table 2: Specialized Capabilities of Advanced Synthesizability Models

| Model | Synthetic Method Prediction | Precursor Identification | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| SynthNN [2] | Not available | Not available | Outperformed 20 expert material scientists in discovery task |

| CLscore Model [4] | Not available | Not available | 86.2% true positive rate for materials discovered after training period |

| Solid-State PU Model [5] | Limited capability | Not available | Applied to 4,103 ternary oxides with human-curated data |

| CSLLM Framework [3] | 91.0% classification accuracy | 80.2% success rate | Identified 45,632 synthesizable materials from 105,321 theoretical structures |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

SynthNN Protocol for Composition-Based Prediction

The SynthNN model employs a deep learning architecture specifically designed for synthesizability classification based solely on chemical composition [2]. The experimental protocol involves:

Data Curation and Preprocessing

- Positive examples are extracted from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), representing synthesized crystalline inorganic materials [2].

- Artificially generated unsynthesized materials serve as negative examples, acknowledging that some may actually be synthesizable but unreported [2].

- The training dataset employs a semi-supervised Positive-Unlabeled (PU) learning approach that treats unsynthesized materials as unlabeled data and probabilistically reweights them according to their likelihood of being synthesizable [2].

Model Architecture and Training

- The model utilizes an atom2vec representation, where each chemical formula is represented by a learned atom embedding matrix optimized alongside other neural network parameters [2].

- The dimensionality of this representation is treated as a hyperparameter determined prior to model training [2].

- The model learns chemical principles of charge-balancing, chemical family relationships, and ionicity directly from the distribution of synthesized materials without explicit programming of these rules [2].

Validation Methodology

- Performance metrics are calculated by treating synthesized materials and artificially generated unsynthesized materials as positive and negative examples, respectively [2].

- The model is benchmarked against random guessing and charge-balancing baselines, with evaluation metrics including precision, recall, and F1-score [2].

Crystal-Likeness Score (CLscore) Protocol for Structure-Based Prediction

The CLscore model employs a graph convolutional neural network framework to predict synthesizability from crystal structure information [4]:

Data Preparation

- Training data is sourced from experimentally reported cases in the Materials Project database (9,356 materials) [4].

- The model utilizes partially supervised learning, adapting Positive and Unlabeled (PU) machine learning to handle the lack of confirmed non-synthesizable examples [4].

Model Implementation

- Graph convolutional neural networks serve as classifiers, processing crystal structure graphs as input [4].

- The model outputs a crystal-likeness score (CLscore) ranging from 0 to 1, with scores >0.5 indicating high synthesizability probability [4].

Temporal Validation

- The model is trained on databases current through the end of 2014 [4].

- Validation is performed against materials newly reported between 2015-2019, achieving an 86.2% true positive rate [4].

Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM) Protocol

The CSLLM framework represents the state-of-the-art in synthesizability prediction, utilizing three specialized large language models [3]:

Dataset Construction

- A balanced dataset of 70,120 synthesizable crystal structures from ICSD and 80,000 non-synthesizable structures screened from 1.4 million theoretical structures using a pre-trained PU learning model [3].

- Non-synthesizable examples are selected based on CLscore <0.1 from the pre-trained model [3].

- The dataset covers seven crystal systems and compositions with 1-7 elements, excluding disordered structures [3].

Material String Representation

- Crystal structures are converted to a specialized text representation called "material string" that integrates essential crystal information compactly [3].

- The format includes space group, lattice parameters, atomic species with Wyckoff positions, and coordinates in a condensed format [3].

Model Fine-tuning

- Three separate LLMs are fine-tuned for synthesizability prediction, synthetic method classification, and precursor identification [3].

- The framework uses domain-focused fine-tuning to align linguistic features with material features critical to synthesizability [3].

Visualizing Synthesizability Prediction Workflows

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Key Research Resources for Synthesizability Prediction Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Access Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Materials Databases | Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [2] [3] | Source of synthesizable (positive) examples for training | Commercial license required |

| Theoretical Materials Databases | Materials Project (MP) [3], Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD) [3], Computational Materials Database [3], JARVIS [3] | Source of hypothetical structures for negative examples or screening | Publicly accessible |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | Graph Convolutional Networks [4], Atom2Vec [2], Large Language Models [3] | Model architectures for feature learning and prediction | Open-source implementations available |

| Validation Resources | Temporal hold-out sets [4], Human expert comparisons [2], Experimental synthesis reports [5] | Performance benchmarking and model validation | Requires careful experimental design |

The evolution of synthesizability prediction methods from heuristic rules to data-driven models represents a paradigm shift in materials discovery. The performance comparisons clearly demonstrate that machine learning approaches, particularly those utilizing positive-unlabeled learning and large language models, significantly outperform traditional thermodynamic stability assessments. The CSLLM framework's achievement of 98.6% prediction accuracy, coupled with its capabilities for synthetic method classification and precursor identification, signals a new era where synthesizability prediction becomes an integral component of computational materials design [3].

Future advancements will likely focus on several key areas: developing more robust synthesizability metrics that incorporate kinetic and processing parameters, creating comprehensive synthesis planning tools that recommend specific reaction conditions, and implementing agentic workflows that integrate real-time experimental feedback to continuously refine predictions [1]. As these tools mature, the synthesis gap that currently limits the translation of computational predictions to experimental realization will progressively narrow, accelerating the discovery and deployment of novel functional materials across energy, electronics, and healthcare applications.

The High Cost of Failed Syntheses in Drug Discovery Pipelines

In the meticulously optimized world of pharmaceutical research, the synthesis of novel chemical compounds remains a critical bottleneck that significantly impacts both the timeline and financial burden of drug development. The Design-Make-Test-Analyse (DMTA) cycle serves as the fundamental iterative process for discovering and optimizing new small-molecule drug candidates [6]. Within this cycle, the "Make" phase—the actual synthesis of target compounds—frequently constitutes the most costly and time-consuming element, particularly when complex biological targets demand intricate chemical structures with multi-step synthetic routes [6]. Failed syntheses at this stage consume substantial resources, as inability to obtain the desired chemical matter for biological testing invalidates the entire iterative cycle, wasting previous design efforts and postponing critical discovery milestones.

The financial implications are staggering. The overall cost of bringing a new drug to market is estimated to average $1.3 billion, with some analyses reaching as high as $2.6 billion [7] [8]. These figures encompass not only successful candidates but also the extensive costs of failed drug development programs. While clinical trial failures account for a significant portion of this cost—with 90% of drug candidates failing after entering clinical studies—synthesis failures in the preclinical phase represent a substantial, though often less visible, financial drain [9]. This review examines the specific costs associated with failed syntheses, compares traditional and emerging computational approaches for mitigating these failures, and provides experimental frameworks for validating synthesizability predictions against empirical synthesis data.

Quantifying the Cost Burden of Synthetic Failure

Comprehensive Cost Analysis of Drug Development Stages

The financial burden of drug development extends far beyond simple out-of-pocket expenses, incorporating complex factors including capital costs and the high probability of failure at each stage. Recent economic evaluations indicate that the mean out-of-pocket cost for developing a new drug is approximately $172.7 million, but this figure rises to $515.8 million when accounting for the cost of failures, and further escalates to $879.3 million when both failures and capital costs are included [10]. These costs vary considerably by therapeutic area, with pain and anesthesia drugs reaching nearly $1.76 billion in fully capitalized development costs [10].

Table 1: Comprehensive Drug Development Cost Breakdown

| Cost Category | Mean Value (Millions USD) | Therapeutic Class Range | Key Inclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Out-of-Pocket Cost | $172.7 | $72.5 (Genitourinary) - $297.2 (Pain & Anesthesia) | Direct expenses from nonclinical through postmarketing stages |

| Expected Cost (Including Failures) | $515.8 | Not specified | Out-of-pocket costs + expenditures on failed drug candidates |

| Expected Capitalized Cost | $879.3 | $378.7 (Anti-infectives) - $1756.2 (Pain & Anesthesia) | Expected cost + opportunity cost of capital over development timeline |

The synthesis process contributes significantly to these costs through multiple channels: direct material and labor expenses for chemistry teams, extended timeline costs, and the opportunity cost of pursuing ultimately non-viable chemical series. Furthermore, the increasing complexity of biological targets often necessitates more elaborate chemical structures, which in turn require longer synthetic routes with higher probabilities of failure at individual steps [6].

The Expanding Chemical Space and Synthesis Challenges

The fundamental challenge of synthetic chemistry in drug discovery has been amplified by the explosive growth of accessible chemical space. With "make-on-demand" virtual libraries now containing tens to hundreds of billions of potentially synthesizable compounds, the disconnect between designed molecules and their synthetic feasibility has become increasingly problematic [8] [11]. While computational methods can now design unprecedented numbers of potentially active compounds, the practical synthesis of these molecules often presents significant challenges.

Traditional synthesis planning relied heavily on chemical intuition and manual literature searching, approaches that are increasingly inadequate for navigating the exponentially growing chemical space [6]. This limitation frequently results in:

- Extended optimization cycles for complex molecules, requiring numerous synthetic iterations

- Abandonment of promising chemical series due to synthetic intractability

- Strategic misdirection of medicinal chemistry resources toward synthetic challenges rather than biological optimization

The critical need to address these challenges has catalyzed the development of advanced computational approaches that predict synthetic feasibility before laboratory work begins.

Comparative Analysis of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

Traditional vs. Modern Computational Approaches

The evolution from traditional computer-assisted drug design to contemporary artificial intelligence (AI)-driven approaches represents a paradigm shift in how synthetic feasibility is assessed early in the drug discovery process.

Table 2: Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Methodologies

| Methodology | Key Features | Limitations | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Retrosynthetic Analysis | Human expertise-based; Rule-based expert systems; Manual literature searching | Limited by chemist's experience; Difficult to scale; Manually curated reaction databases | Route success determined after multi-step synthesis attempts |

| Modern Computer-Assisted Synthesis Planning (CASP) | Data-driven machine learning models; Monte Carlo Tree Search/A* Search algorithms; Integration with building block availability | "Evaluation gap" between single-step prediction and route success; Limited negative reaction data in training sets | Validation on complex, multi-step natural product syntheses |

| Bayesian Deep Learning with HTE | Bayesian neural networks (BNNs) for uncertainty quantification; High-throughput experimentation (HTE) data integration; Active learning implementation | Requires extensive initial dataset generation; Computational intensity; Platform dependency | 11,669 distinct acid amine coupling reactions; 89.48% feasibility prediction accuracy [12] |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Direct molecular graph processing; Structure-property relationship learning; Multi-task learning capabilities | Black-box nature; Limited interpretability; Data hunger for robust training | Enhanced property prediction, toxicity assessment, and novel molecule design [13] |

Traditional retrosynthetic analysis, formalized by E.J. Corey, involves the recursive deconstruction of target molecules into simpler, commercially available precursors [6]. While this approach benefits from human expertise and chemical intuition, it faces significant challenges in navigating the combinatorial explosion of potential synthetic routes for complex molecules, often requiring lengthy optimization cycles for individual steps.

Modern Computer-Assisted Synthesis Planning (CASP) has evolved from early rule-based systems to data-driven machine learning models that propose both single-step disconnections and complete multi-step synthetic routes [6]. These systems employ search algorithms like Monte Carlo Tree Search and A* Search to navigate the vast space of possible synthetic pathways. However, an "evaluation gap" persists where high performance on single-step predictions doesn't always translate to successful complete routes [6].

Emerging AI-Driven Platforms

The most recent advancements integrate multiple AI approaches to create more robust synthesis prediction systems. Bayesian deep learning frameworks leverage high-throughput experimentation data to predict not only reaction feasibility but also robustness against environmental factors [12]. These systems employ Bayesian neural networks (BNNs) that provide uncertainty estimates alongside predictions, enabling more reliable feasibility assessment and efficient resource allocation.

Simultaneously, graph neural networks (GNNs) have emerged as powerful tools for molecular property prediction and synthetic accessibility assessment [13] [14]. GNNs operate directly on molecular graph structures, learning complex structure-property relationships without requiring pre-specified molecular descriptors. This approach has demonstrated particular utility in predicting reaction outcomes and molecular properties relevant to synthetic planning.

Experimental Protocols for Validating Synthesizability Predictions

High-Throughput Experimentation for Model Training

The development of robust synthesizability predictions requires extensive empirical data for model training and validation. Recent research has established comprehensive protocols for generating the necessary datasets at scale.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Synthesis Validation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Building Block Libraries | Enamine, OTAVA, eMolecules, Chemspace | Provide diverse starting materials representing broad chemical space |

| Coupling Reagents | 6 condensation reagents (undisclosed) | Facilitate bond formation in model reaction systems |

| Catalytic Systems | C-H functionalization catalysts; Suzuki-Miyaura catalysts; Buchwald-Hartwig catalysts | Enable diverse transformation methodologies |

| HTE Platforms | ChemLex's Automated Synthesis Lab-Version 1.1 (CASL-V1.1) | Automate reaction setup, execution, and analysis at micro-scale |

| Analytical Tools | Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS); UV absorbance detection | Quantify reaction yields and identify byproducts |

A landmark study established a robust experimental framework utilizing an in-house High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) platform to execute 11,669 distinct acid amine coupling reactions within 156 instrument hours [12]. The experimental protocol encompassed:

- Diversity-guided substrate sampling: 272 carboxylic acids and 231 amines were selected using MaxMin sampling within predetermined substrate categories to ensure representative coverage of patent chemical space

- Systematic condition variation: 6 condensation reagents, 2 bases, and 1 solvent were combined in systematic arrays

- Microscale execution: Reactions were conducted at 200-300 μL volumes, appropriate for early-stage drug discovery scale

- Analytical quantification: Uncalibrated UV absorbance ratios in LC-MS were used to determine reaction yields following established industry protocols [12]

This extensive dataset, the largest single reaction-type HTE collection at industrially relevant scales, enabled robust training of Bayesian neural network models that achieved 89.48% accuracy in predicting reaction feasibility [12].

Bayesian Deep Learning with Active Learning Implementation

The experimental validation of synthesizability predictions employs sophisticated machine learning architectures trained on empirical data. The following workflow illustrates the integrated experimental and computational approach:

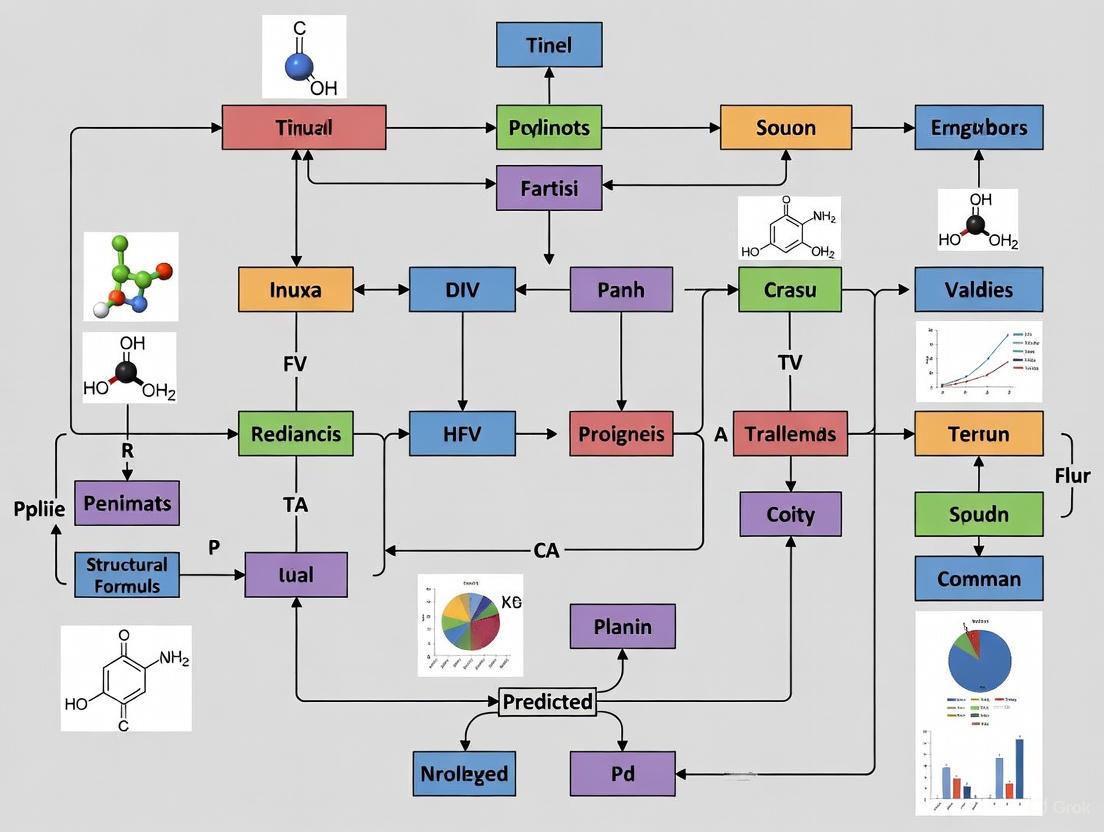

Diagram 1: Experimental-Computational Workflow for Synthesizability Prediction

The Bayesian deep learning framework implements several technical innovations:

- Uncertainty disentanglement: Separates model uncertainty from data uncertainty to identify knowledge gaps

- Active learning implementation: Reduces data requirements by approximately 80% through strategic selection of informative reactions for experimental testing [12]

- Robustness prediction: Correlates intrinsic data uncertainty with reaction reproducibility under varying conditions

This approach demonstrated particular strength in identifying out-of-domain reactions where model predictions were likely to be unreliable, enabling more efficient resource allocation in synthetic campaigns.

Case Studies: Experimental Validation of Predictive Models

Acid-Amine Coupling Reaction Feasibility

The experimental validation of the Bayesian deep learning framework for acid-amine coupling reactions provides compelling evidence for the practical utility of synthesizability predictions. The model was trained on the extensive HTE dataset of 11,669 reactions and achieved:

- 89.48% prediction accuracy for reaction feasibility

- 0.86 F1 score, indicating strong balance between precision and recall

- 80% reduction in data requirements through active learning implementation [12]

Beyond simple feasibility classification, the model successfully predicted reaction robustness—the reproducibility of outcomes under varying environmental conditions. This capability is particularly valuable for process chemistry, where sensitive reactions present significant scaling challenges. The uncertainty analysis effectively identified reactions prone to failure during scale-up, providing practical guidance for synthetic planning in industrial contexts.

AI-Driven Synthesis Planning in Pharmaceutical R&D

Implementation of AI-powered synthesis planning platforms in pharmaceutical companies demonstrates the translational potential of these technologies. At Roche, researchers have developed specialized graph neural networks for predicting C–H functionalization reactions and Suzuki–Miyaura coupling conditions [6]. These systems:

- Generate valuable and innovative ideas for synthetic route design

- Predict screening plate layouts for High-Throughput Experimentation campaigns

- Enable batched multi-objective reaction optimization using Bayesian methods [6]

The experimental validation of these systems involves retrospective analysis of successful synthetic routes and prospective testing on novel target molecules. While these tools excel at providing diverse potential transformations, the generated proposals typically require additional refinement by experienced chemists to become ready-to-execute synthetic routes [6]. This underscores the continuing importance of human expertise in conjunction with AI tools.

Integrated Workflow for Modern Drug Discovery

The most effective approach to mitigating the high cost of failed syntheses integrates computational prediction with experimental validation throughout the drug discovery pipeline. The following diagram illustrates this optimized workflow:

Diagram 2: Integrated Synthesizability-Aware Discovery Workflow

This integrated approach leverages multiple computational technologies:

- Ultra-large virtual libraries of make-on-demand compounds (e.g., Enamine's 65 billion molecules) [8]

- AI-powered synthesizability filters that prioritize readily synthesizable compounds

- Computer-Assisted Synthesis Planning (CASP) tools that generate feasible synthetic routes

- Automated synthesis and purification technologies that accelerate the "Make" phase of the DMTA cycle [6]

- Data analysis and model refinement that continuously improves predictions based on experimental outcomes

The implementation of this synthesizability-aware workflow represents the most promising approach to reducing the cost burden of failed syntheses in modern drug discovery pipelines.

The high cost of failed syntheses in drug discovery represents a significant and persistent challenge in pharmaceutical R&D. Traditional approaches that address synthetic feasibility late in the design process inevitably lead to resource-intensive optimization cycles and program delays. The integration of AI-driven synthesizability predictions early in the molecular design process, coupled with experimental validation through high-throughput experimentation, offers a transformative approach to mitigating these costs. Frameworks that combine Bayesian deep learning with active learning strategies demonstrate particular promise, achieving high prediction accuracy while minimizing data requirements. As these technologies continue to mature and integrate more seamlessly with medicinal chemistry workflows, they hold the potential to significantly reduce the financial burden of synthetic failures and accelerate the delivery of new therapeutics to patients.

For researchers discovering new materials or drug candidates, a fundamental question persists: will a computationally predicted compound actually be synthesizable? Thermodynamic stability, traditionally assessed through metrics like the energy above hull (E_hull), provides a foundational but often incomplete answer. This metric determines whether a material is stable relative to its competing phases at 0 K. However, successful synthesis is a kinetic process; a compound predicted to be thermodynamically stable may never form if its formation is outpaced by kinetic competitors. This guide compares the limitations of the traditional energy above hull metric with the emerging understanding of kinetic stability, framing the discussion within the critical context of validating predictions against experimental synthesis data.

The core limitation is succinctly stated: "phase diagrams do not visualize the free-energy axis, which contains essential information regarding the thermodynamic competition from these competing phases" [15]. Even within a thermodynamic stability region, the kinetic propensity to form undesired by-products can dominate the final experimental outcome.

Quantitative Comparison of Stability Metrics

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, data requirements, and validation challenges of the energy above hull compared to considerations of kinetic stability.

Table 1: Comparison of Energy Above Hull and Kinetic Stability Considerations

| Feature | Energy Above Hull (E_hull) | Kinetic Stability / Competition |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | The energy distance from a phase to the convex hull of stable phases in energy-composition space [16]. | The propensity for a target phase to form without yielding to kinetic by-products; related to the free energy difference between target and competing phases [15]. |

| Primary Focus | Thermodynamic stability at equilibrium (0 K). | Kinetic favorability and transformation rates during synthesis. |

| Underlying Calculation | Convex hull construction in formation energy-composition space [17] [16]. | Metrics like Minimum Thermodynamic Competition (MTC), maximizing ΔΦ = Φtarget - min(Φcompeting) [15]. |

| Typical Data Source | Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations [17]. | Combined DFT, Pourbaix diagrams, and experimental synthesis data [15]. |

| Key Limitation | Poor predictor of actual synthesizability; does not account for kinetic competition [17] [15]. | Difficult to quantify precisely; depends on specific synthesis pathway and conditions. |

| Validation Method | Comparison to static, ground-state phase diagrams. | Requires systematic experimental synthesis across a range of conditions [15]. |

Limitations of Energy Above Hull in Predictive Workflows

The energy above hull, while a necessary condition for stability, performs poorly as a sole metric for predicting which materials can be successfully synthesized.

The Critical Gap Between Formation Energy and Stability

Machine learning (ML) models can now predict the formation energy (ΔHf) of compounds with accuracy approaching that of Density Functional Theory (DFT). However, thermodynamic stability is governed by the decomposition enthalpy (ΔHd), which is determined by a convex hull construction that pits the formation energy of a target compound against all other compounds in its chemical space [17]. The central problem is that "effectively no linear correlation exists between ΔHd and ΔHf," and ΔHd spans a much smaller energy range, making it a more sensitive and subtle quantity to predict [17]. While a model might predict formation energy well, the small errors in these predictions can be large enough to completely misclassify a material's stability, as stability is a relative measure determined by a nonlinear convex hull construction [17].

The Neglect of Kinetic Competition

A stable E_hull indicates a compound is thermodynamically downhill, but it does not guarantee it is the most kinetically accessible product. A study on aqueous synthesis of LiIn(IO₃)₄ and LiFePO₄ demonstrated that even for synthesis conditions within the thermodynamic stability region of a phase diagram, phase-pure synthesis occurs only when thermodynamic competition with undesired phases is minimized [15]. This shows that the energy landscape's details beyond the hull—specifically, the energy gaps to the most competitive kinetically favored by-products—are critical for practical synthesizability.

Beyond the Hull: Frameworks for Kinetic and Synthetic Feasibility

The Minimum Thermodynamic Competition (MTC) Metric

To address the limitations of traditional phase diagrams, A. Dave et al. proposed the Minimum Thermodynamic Competition (MTC) hypothesis. This framework identifies optimal synthesis conditions as the point where the difference in free energy between a target phase and the minimal energy of all other competing phases is maximized [15]. The thermodynamic competition a target phase k experiences is quantified as:

ΔΦ(Y) = Φk(Y) - min(Φi(Y)) for all competing phases i [15]. Here, Y represents intensive variables like pH, redox potential, and ion concentrations. Minimizing ΔΦ(Y) (making it more negative) maximizes the energy barrier for nucleating competing phases, thereby minimizing their kinetic persistence.

Table 2: Experimental Protocol for Validating MTC in Aqueous Synthesis [15]

| Step | Protocol Detail | Function |

|---|---|---|

| 1. System Definition | Select target phase and relevant chemical system (e.g., Li-Fe-P-O-H for LiFePOâ‚„). | Defines the phase space for competitor identification. |

| 2. Free Energy Calculation | Calculate Pourbaix potentials (Φ) for all solid and aqueous phases using DFT-derived energies [15]. | Constructs the free-energy landscape. The Pourbaix potential incorporates pH, redox potential, and ion concentrations. |

| 3. MTC Optimization | computationally find the conditions Y* that minimize ΔΦ(Y) [15]. | Identifies the theoretical optimal synthesis point. |

| 4. Experimental Validation | Perform systematic synthesis across a wide range of pH, E, and precursor concentrations. | Tests whether phase-purity correlates with the MTC-predicted conditions. |

| 5. Analysis | Use X-ray diffraction and other characterization to identify phases present. | Provides ground-truth data to validate the MTC prediction. |

Data-Driven Feasibility Scores in Molecular Design

In organic chemistry and drug discovery, assessing synthetic feasibility faces analogous challenges. Rule-based or ML-driven scores exist, but they often fail to generalize to new chemical spaces or capture subtle differences obvious to expert chemists, such as chirality [18]. The Focused Synthesizability score (FSscore) introduces a two-stage approach: a model is first pre-trained on a large dataset of chemical reactions, then fine-tuned with human expert feedback on a specific chemical space of interest [18]. This incorporates practical, resource-dependent synthetic knowledge that pure thermodynamic metrics cannot capture, directly linking computational prediction to experimental practicality.

Table 3: Key Computational and Experimental Resources for Stability Research

| Resource / Reagent | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| VASP / DFTB+ | Software for performing DFT calculations to obtain formation energies, with DFTB+ offering a faster, approximate alternative [19]. |

| PyMatgen (Python) | A library for materials analysis that includes modules for constructing phase diagrams and calculating energy above hull [16]. |

| mp-api (Python) | The official API for the Materials Project database, allowing automated retrieval of computed material properties for hull construction [16]. |

| Pourbaix Diagram Data | First-principles derived diagrams (e.g., from Materials Project) essential for evaluating stability in aqueous electrochemical systems [15]. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) | Platform for miniaturized, parallelized reactions, enabling systematic experimental validation across diverse conditions [20]. |

| Text-Mined Synthesis Datasets | Collections of published synthesis recipes used for empirical validation of thermodynamic hypotheses [15]. |

Visualizing Workflows and Conceptual Relationships

From Prediction to Validation: An Integrated Workflow

The diagram below outlines a robust workflow for developing and validating synthesizability predictions, integrating both computational and experimental arms to address the limitations of standalone metrics.

The Hierarchy of Stability

This diagram clarifies the conceptual relationship between different types of stability and the metrics used to assess them, illustrating why a thermodynamically stable compound may not be synthesizable.

The Critical Role of Experimental Data for Model Training and Validation

The reliable prediction of material synthesizability represents a monumental challenge in accelerating materials discovery. While computational models offer high-throughput screening, their real-world utility hinges on rigorous validation against experimental data. This guide objectively compares the performance of leading synthesizability prediction methods, demonstrating that machine learning models trained on comprehensive experimental data significantly outperform traditional computational approaches in identifying synthetically accessible materials.

A fundamental challenge in materials science is bridging the gap between computationally predicted and experimentally realized materials. The discovery of new, functional materials often begins with identifying a novel chemical composition that is synthesizable—defined as being synthetically accessible through current capabilities, regardless of whether it has been reported yet [2]. However, predicting synthesizability is notoriously complex. Unlike organic molecules, inorganic crystalline materials often lack well-understood reaction mechanisms, and their synthesis is influenced by kinetic stabilization, reactant selection, and specific equipment availability, moving beyond pure thermodynamic considerations [2] [21]. This complexity necessitates a robust framework for developing and validating predictive models, where experimental data plays the indispensable role of grounding digital explorations in physical reality.

Comparative Analysis of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

We evaluate the performance of three dominant approaches to synthesizability prediction. The following table summarizes their core methodologies, advantages, and limitations, providing a foundational comparison for researchers.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Synthesizability Prediction Methodologies

| Prediction Method | Core Methodology | Key Performance Metric | Primary Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charge-Balancing | Applies net neutral ionic charge filter based on common oxidation states [2]. | Low Precision (23-37% of known synthesized materials are charge-balanced) [2]. | Computationally inexpensive; chemically intuitive. | Inflexible; fails for metallic, covalent, or complex ionic materials. |

| DFT-based Formation Energy | Uses Density Functional Theory to calculate energy relative to stable decomposition products [2]. | Captures ~50% of synthesized materials [2]. | Provides foundational thermodynamic insight. | Fails to account for kinetic stabilization and non-equilibrium synthesis routes. |

| Data-Driven ML (SynthNN) | Deep learning model trained on the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) with positive-unlabeled learning [2]. | 7x higher precision than formation energy; 1.5x higher precision than human experts [2]. | Learns complex, multi-factor relationships from all known synthesized materials; highly computationally efficient. | Performance is dependent on the quality and scope of the underlying experimental database. |

The quantitative performance gap is striking. The charge-balancing heuristic, while simple, fails for a majority of known synthesized compounds, including a mere 23% of known ionic binary cesium compounds [2]. Similarly, DFT-based formation energy calculations, a cornerstone of computational materials design, capture only about half of all synthesized materials because they cannot account for the kinetic and non-equilibrium factors prevalent in real-world labs [2] [21]. In contrast, the machine learning model SynthNN, which learns directly from the full distribution of experimental data in the ICSD, achieves a seven-fold higher precision in identifying synthesizable materials compared to formation energy calculations [2].

Experimental Protocols for Model Training and Validation

The superior performance of data-driven models is predicated on a rigorous, iterative protocol that integrates computational design with experimental validation. The standard machine learning workflow for this purpose is built upon a structured partition of data into training, validation, and test sets [22] [23] [24].

The Model Development Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standard machine learning workflow that ensures a model's reliability before it is deployed for actual discovery.

Step 1: Data Partitioning The foundational step involves splitting the entire available dataset of known materials into three distinct subsets [22] [24]:

- Training Set: The largest subset (e.g., ~80%) used to fit the model's parameters (e.g., weights in a neural network) [23].

- Validation Set: A separate subset (e.g., ~10%) used to provide an unbiased evaluation of the model during training. This set is crucial for tuning the model's architecture and hyperparameters and for implementing techniques like early stopping to prevent overfitting [22] [24].

- Test Set: A final, held-out subset (e.g., ~10%) used only for the final, unbiased evaluation of the fully-trained model. This set must never be used for training or validation to ensure it provides a honest estimate of performance on unseen data [22] [23].

Step 2: Model Training The model, such as the SynthNN deep learning architecture, is trained on the training data set. For compositional models, this often involves using learned representations like atom2vec, which discovers optimal feature sets directly from the distribution of known materials, without relying on pre-defined chemical rules [2].

Step 3: Hyperparameter Tuning & Model Selection The trained model is evaluated on the validation set. Its performance on this unseen data guides the adjustment of hyperparameters (e.g., number of neural network layers). This process is iterative, with the model being repeatedly trained and validated until optimal performance is achieved [22] [24].

Step 4: Final Model Evaluation The single best-performing model from the validation phase is evaluated once on the held-out test set. This step provides the final, unbiased metrics (e.g., precision, accuracy) that are reported as the model's expected real-world performance [24].

Addressing the "Unlabeled Data" Challenge with PU Learning

A unique challenge in synthesizability prediction is the lack of confirmed negative examples (i.e., materials definitively known to be unsynthesizable) [2]. To address this, methods like SynthNN employ Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning. In this framework:

- Positive (P) Data: Known synthesized materials from databases like the ICSD.

- Unlabeled (U) Data: A large set of artificially generated chemical formulas that are treated as not-yet-synthesized, with the understanding that some may actually be synthesizable [2].

The PU learning algorithm treats the unlabeled examples as probabilistic, reweighting them according to their likelihood of being synthesizable during training. This allows the model to learn from the entire space of possible compositions without definitive negative labels [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The experimental validation of computational predictions relies on a suite of specialized reagents, equipment, and data resources. The following table details key components of this toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Synthesis & Validation

| Tool / Material | Primary Function | Critical Role in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) | A comprehensive database of experimentally reported and structurally characterized inorganic crystals [2]. | Serves as the primary source of "positive" experimental data for training and benchmarking synthesizability models. |

| Solid-State Precursors | High-purity elemental powders, oxides, or other compounds used as starting materials for solid-state reactions. | The quality and purity of precursors are critical for reproducing predicted syntheses and avoiding spurious results. |

| Physical Vapor Deposition Systems | Systems for thin-film growth (e.g., sputtering, pulsed laser deposition) [21]. | Enable the synthesis of metastable materials predicted by models, which may not be accessible via bulk methods. |

| In Situ Characterization Tools | Real-time diagnostics like X-ray diffraction, electron microscopy, and optical spectroscopy [21]. | Provide direct, atomic-scale insight into phase evolution and reaction pathways during synthesis, closing the loop with model predictions. |

| SynthNN or Equivalent ML Model | A deep learning classifier trained on compositional data to predict synthesizability [2]. | Provides a rapid, high-throughput filter to prioritize the most promising candidate materials for experimental investigation. |

| Alamecin | Alamecin (Alafosfalin) | Alamecin is a phosphonodipeptide antibacterial for research. It inhibits cell wall biosynthesis and is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Einecs 298-470-7 | Einecs 298-470-7|Chemical Reagent for Research | High-purity Einecs 298-470-7 for research use only (RUO). Explore its applications and value in scientific development. Strictly not for personal use. |

The integration of vast experimental datasets into machine learning frameworks has demonstrably transformed the field of synthesizability prediction. As evidenced by the performance gap closed by models like SynthNN, the critical role of experimental data extends beyond mere final validation—it is the essential fuel for creating more intelligent and reliable predictive tools. The future of accelerated materials discovery lies in the continued tightening of the iterative loop between in silico prediction and in situ experimental validation, leveraging advances in multi-probe diagnostics and theory-guided data science to further refine our understanding of the complex factors governing synthesis [21].

In the field of computer-aided drug discovery, the ability to accurately predict the synthesizability of a proposed molecule is a critical gatekeeper between in-silico design and real-world application. The central thesis of this research is that the validity of synthesizability predictions can only be firmly established through rigorous validation against experimental synthesis data. This case study examines how data curation—the systematic selection, cleaning, and preparation of data—fundamentally impacts the accuracy of such predictions. Evidence increasingly demonstrates that sophisticated algorithms alone are insufficient; the quality, relevance, and structure of the underlying training data are paramount [25] [26].

The pharmaceutical industry faces a well-documented "garbage in, garbage out" conundrum, where models trained on incomplete or biased data produce misleading results, wasting significant resources [26]. This analysis compares traditional and data-curated approaches to synthesizability prediction, providing quantitative evidence that strategic data curation dramatically enhances model performance and reliability, ultimately bridging the gap between computational design and experimental synthesis.

Comparative Analysis of Prediction Approaches

The table below summarizes a direct comparison between a traditional data approach and a data-curated strategy for predicting synthesizability, drawing from recent large-scale experimental validations.

| Feature | Traditional Approach | Data-Curated Approach | Impact on Prediction Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Foundation | Relies on public databases (e.g., ChEMBL, PubChem) which often lack negative results and commercial context [26]. | Integrates proprietary, high-throughput experimentation (HTE) data and patent data, capturing failure cases and strategic intent [12] [26]. | Mitigates publication bias, providing a more realistic view of chemical space, which increases real-world prediction reliability. |

| Data Volume & Relevance | Often uses large, undifferentiated datasets [25]. | Employs smaller, targeted datasets focused on specific model weaknesses or domains [25] [12]. | A study showed a 97% performance increase with just 4% of a planned data volume by using targeted data [25]. |

| Validation Method | Primarily computational or based on historical literature data. | Direct validation against large-scale, automated experimental results [12]. | Ensures predictions are grounded in empirical reality, not just historical correlation. |

| Handling of Uncertainty | Often provides a single prediction without a confidence metric. | Uses Bayesian frameworks to quantify prediction uncertainty and identify out-of-domain reactions [12]. | Allows researchers to prioritize predictions; one model showed a high correlation between probability score and accuracy [12] [27]. |

| Key Performance Indicator | Limited experimental validation on narrow chemical spaces. | Achieved 89.48% accuracy and 0.86 F1 score in predicting reaction feasibility across a broad chemical space [12]. | Demonstrates high accuracy on a diverse, industrially-relevant set of reactions, proving generalizability. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

High-Throughput Experimental Validation

A landmark study published in Nature Communications in 2025 established a new benchmark for validating synthesizability predictions through massive, automated experimental testing [12].

- Objective: To systematically address the challenges of predicting organic reaction feasibility and robustness by integrating high-throughput experimentation (HTE) with Bayesian deep learning.

- Dataset Curation: The research utilized an in-house HTE platform (CASL-V1.1) to conduct 11,669 distinct acid-amine coupling reactions in just 156 instrument hours. This created the most extensive single HTE dataset for a reaction type at a volumetric scale practical for industrial delivery [12].

- Chemical Space Design: To ensure industrial relevance, the substrate set was curated from commercially available compounds but used a diversity-guided down-sampling strategy to align their distribution with that of the patent dataset Pistachio. This involved categorizing acids and amines and using the MaxMin sampling method within each category to maximize structural diversity [12].

- Incorporating Negative Data: A critical step was addressing the lack of negative results in published data. The team introduced 5,600 potentially negative reaction examples by leveraging expert chemical rules around nucleophilicity and steric hindrance [12].

- Model Training & Evaluation: A Bayesian neural network (BNN) model was trained on this curated HTE data. Its performance was benchmarked by its ability to predict reaction feasibility (success or failure) on a hold-out test set. The model's fine-grained uncertainty analysis was also used to power an active learning loop, effectively reducing data requirements by ~80% [12].

Data Curation via Reward Models

Another approach, focused on post-training data curation for AI models, uses specialized "curator" models to filter and select high-quality data [28].

- Objective: To improve model performance and efficiency by systematically selecting only the highest-quality data for training, rather than using massive, unfiltered datasets.

- Curator Models: The framework employs small, specialized models (e.g., ~450M parameters) to evaluate each data sample for specific attributes like correctness, reasoning quality, and coherence. Classifier curators (~3B parameters) are tuned for strict pass/fail decisions with very low false-positive rates [28].

- Application to Code Reasoning: In a case study on a code reasoning corpus, curation combined semantic filtering (using multiple curator models) with an execution filter that ran test cases. This two-step process filtered out 62% of the corpus, leaving a concise, high-signal dataset [28].

- Validation: When models were fine-tuned on this curated dataset, they matched or exceeded the performance of models trained on the entire, unfiltered dataset, while using roughly half the tokens. This resulted in a 2x speedup in training efficiency [28].

Visualization of Workflows

The AI Development Feedback Loop

The following diagram illustrates the iterative feedback loop that integrates data curation, model training, and evaluation to continuously improve prediction accuracy.

Data Curation Pipeline for Synthesis Prediction

This diagram details the specific data curation and model training workflow used for high-accuracy synthesizability prediction, as validated by high-throughput experimentation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers aiming to build and validate synthesizability models, the following tools and resources are essential.

| Tool/Resource | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Automated HTE Platforms (e.g., CASL-V1.1 [12]) | Enables rapid, large-scale experimental validation of reactions, generating the high-quality ground-truth data needed to train and test predictive models. |

| Retrosynthesis Software (e.g., Spaya [29]) | Performs data-driven synthetic planning to compute a synthesizability score (RScore) for a molecule, which can be used as a training target or validation filter. |

| Public Bioactivity Databases (e.g., ChEMBL, PubChem [30] [26]) | Provide a foundational, open-source knowledge base of chemical structures and bioactivities, useful for initial model building but requiring careful curation. |

| Specialized Curation Models (e.g., Classifier, Scoring, Reasoning Curators [28]) | Small AI models used to filter large datasets, selecting for high-quality examples based on correctness, reasoning, and other domain-specific attributes. |

| Bayesian Neural Networks (BNNs) [12] | A class of AI models that not only make predictions but also quantify their own uncertainty, which is critical for identifying model weaknesses and guiding active learning. |

| Patent Data (e.g., Pistachio [12] [26]) | Provides a rich source of commercially relevant chemical information that includes synthetic strategies and intent, helping to bridge the gap between academic and industrial chemistry. |

| 7-Methylmianserin maleate | 7-Methylmianserin maleate, CAS:85750-29-4, MF:C23H26N2O4, MW:394.5 g/mol |

| 3-Fluoroethcathinone | 3-Fluoroethcathinone HCl |

Advanced Models and Workflows for Predicting Synthesizable Candidates

Leveraging Positive-Unlabeled Learning from Human-Curated Data

In numerous scientific fields, from materials science to drug discovery, a common data challenge persists: researchers have access to a limited set of confirmed positive examples alongside a vast pool of unlabeled data where the true status is unknown. This is the fundamental problem setting of Positive-Unlabeled (PU) learning, a specialized branch of machine learning that aims to train classifiers using only positive and unlabeled examples, without confirmed negative samples [31]. The significance of PU learning stems from its ability to address realistic data scenarios where negative examples are difficult, expensive, or impossible to obtain. In materials science, this manifests as knowing which materials have been successfully synthesized (positives) but lacking definitive data on哪些 compositions cannot be synthesized (negatives) [32] [33]. Similarly, in drug discovery, researchers may have confirmed drug-target interactions but lack experimentally validated non-interactions [34].

The core challenge of PU learning lies in distinguishing potential positives from true negatives within the unlabeled set. This is particularly crucial for scientific applications where prediction reliability directly impacts experimental validation costs and research direction. This review examines how PU learning methodologies, particularly when combined with human-curated data, are advancing synthesizability predictions across multiple scientific domains by providing a more nuanced approach than traditional binary classification.

Table 1: Core PU Learning Scenarios in Scientific Research

| Scenario Type | Data Characteristics | Common Applications | Key Assumptions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Training-Set | Positive and unlabeled examples drawn from the same dataset [31] | Medical diagnosis, Survey data with under-reporting | Labeled examples are representative true positives |

| Case-Control | Positive and unlabeled examples come from two independent datasets [31] | Knowledge base completion, Materials synthesizability | Unlabeled set follows the real distribution |

Methodological Framework: How PU Learning Works

Fundamental Techniques and Algorithms

PU learning methodologies primarily fall into two categories. The two-step approach first identifies "reliable negative" examples from the unlabeled data, then trains a standard binary classifier using the positive and identified negative examples [35] [34]. This approach often employs iterative methods, splitting the unlabeled set to handle class imbalance, and may include a second stage that expands the reliable negative set through semi-supervised learning [35]. Alternatively, classifier adaptation methods optimize a classifier directly with all available data (both positive and unlabeled) without pre-selecting negative samples, instead using probabilistic formulations to estimate class membership [36] [31].

Several key assumptions enable effective PU learning. The Selected Completely At Random (SCAR) assumption posits that positive instances are labeled independently of their features, making the labeled set a representative sample of all positive instances [35]. The separability assumption presumes that a perfect classifier can distinguish positive from negative instances in the feature space, while the smoothness assumption states that similar instances likely share the same class membership [35].

PU Learning Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow for applying PU learning to scientific problems such as synthesizability prediction:

Comparative Analysis of PU Learning implementations

Materials Science Applications

In materials science, PU learning has emerged as a powerful solution to the synthesizability prediction challenge. Traditional approaches relying on thermodynamic stability metrics like energy above convex hull (Eâ„Žull) have proven insufficient, as they ignore kinetic factors and synthesis conditions that crucially impact synthesizability [32]. Similarly, charge-balancing criteria fail to accurately predict synthesizability, with only 37% of synthesized inorganic materials meeting this criterion [2].

Table 2: PU Learning implementations in Materials Science

| Study | Dataset | PU Method | Key Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chung et al. (2025) [32] | 4,103 human-curated ternary oxides | Positive-unlabeled learning model | Predicted 134 of 4,312 hypothetical compositions as synthesizable |

| SynCoTrain (2025) [33] | Oxide crystals from Materials Project | Co-training framework with ALIGNN and SchNet | Achieved high recall on internal and leave-out test sets |

| SynthNN [2] | ICSD data with artificially generated unsynthesized materials | Class-weighted PU learning | 7× higher precision than DFT-calculated formation energies |

The SynCoTrain framework exemplifies advanced PU learning implementation, employing a dual-classifier co-training approach with two graph convolutional neural networks: SchNet and ALIGNN [33]. This architecture combines a "physicist's perspective" (SchNet's continuous convolution filters for atomic structures) with a "chemist's perspective" (ALIGNN's encoding of atomic bonds and angles), with both classifiers iteratively exchanging predictions to reduce model bias and enhance generalizability [33].

Drug Discovery Applications

In pharmaceutical research, PU learning addresses the critical challenge of identifying drug-target interactions (DTIs) where only positive interactions are typically documented in known databases [34]. The PUDTI framework exemplifies this approach, integrating a negative sample extraction method (NDTISE) with probabilities that ambiguous samples belong to positive or negative classes, and an SVM-based optimization model [34]. When evaluated on four classes of DTI datasets (human enzymes, ion channels, GPCRs, and nuclear receptors), PUDTI achieved the highest AUC among seven comparison methods [34].

Another innovative approach, NAPU-bagging SVM, employs a semi-supervised framework where ensemble SVM classifiers are trained on resampled bags containing positive, negative, and unlabeled data [37]. This method manages false positive rates while maintaining high recall rates, crucial for identifying multitarget-directed ligands where comprehensive candidate screening is essential [37].

Table 3: Performance Comparison of PU Learning Methods Across Domains

| Method | Domain | Key Performance Metrics | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human-curated PU (Chung) [32] | Materials Science | Identified 156 outliers in text-mined data | High-quality training data from manual curation |

| SynCoTrain [33] | Materials Science | High recall on test sets | Dual-classifier reduces bias, improves generalization |

| PUDTI [34] | Drug Discovery | Highest AUC on 4 DTI datasets | Integrates multiple biological information sources |

| NAPU-bagging SVM [37] | Drug Discovery | High recall with controlled false positives | Effective for multitarget drug discovery |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Data Curation and Preparation

The foundation of effective PU learning in synthesizability prediction begins with rigorous data curation. Chung et al. manually extracted synthesis information for 4,103 ternary oxides from literature, specifically documenting whether each oxide was synthesized via solid-state reaction and its associated reaction conditions [32]. This human-curated approach enabled the identification of subtle synthesis criteria that automated text mining might miss, such as excluding reactions involving flux or cooling from melt, and ensuring heating temperatures remained below melting points of starting materials [32]. The resulting dataset contained 3,017 solid-state synthesized entries, 595 non-solid-state synthesized entries, and 491 undetermined entries [32].

In protein function prediction, PU-GO employs the ESM2 15B protein language model to generate 5120-dimensional feature vectors for protein sequences, which serve as inputs to a multilayer perceptron (MLP) classifier [36]. The model uses a ranking-based loss function that guides the classifier to rank positive samples higher than unlabeled ones, leveraging the Gene Ontology hierarchical structure to construct class priors [36].

Model Implementation and Training

The implementation of PU learning models requires careful handling of the unique data characteristics. Many approaches use a non-negative risk estimator to prevent the classification risk from becoming negative during training [36]. For example, PU-GO implements the following risk estimator:

$R^(g)=πR^+P(g)+max0,R^−U(g)−πR^−_P(g)+β$

where $0≤β≤π$ is constructed using a margin factor hyperparameter γ, such that $β=γπ$ with $0≤γ≤1$ [36].

In the SynCoTrain framework, the co-training process involves iterative knowledge exchange between the two neural network classifiers (ALIGNN and SchNet), with final labels determined based on averaged predictions [33]. This collaborative approach enhances prediction reliability and generalizability compared to single-model implementations.

Table 4: Key Computational Tools and Resources for PU Learning Implementation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Project Database [32] [33] | Materials Database | Source of crystal structures and composition data | Materials Science |

| ICSD (Inorganic Crystal Structure Database) [32] [2] | Materials Database | Repository of synthesized inorganic materials | Materials Science |

| ESM2 15B Model [36] | Protein Language Model | Generates feature vectors for protein sequences | Bioinformatics |

| ALIGNN [33] | Graph Neural Network | Encodes atomic bonds and bond angles in crystals | Materials Science |

| SchNet [33] | Graph Neural Network | Uses continuous convolution filters for atomic structures | Materials Science |

| Gene Ontology (GO) [36] | Ontology Database | Provides structured information about protein functions | Bioinformatics |

| Two-Step Framework [35] [34] | Algorithm Architecture | Identifies reliable negatives then trains classifier | General PU Learning |

The integration of PU learning with human-curated data represents a significant advancement in synthesizability prediction across scientific domains. By explicitly addressing the reality of incomplete negative data—a common scenario in experimental sciences—these approaches provide more realistic and effective prediction frameworks compared to traditional binary classification methods. The consistent demonstration of improved performance across materials science and drug discovery applications highlights the versatility and robustness of PU learning methodologies.

Future developments in PU learning will likely focus on enhancing model interpretability, integrating transfer learning approaches, and developing more sophisticated methods for handling the inherent uncertainty in unlabeled data. As automated machine learning (Auto-ML) systems for PU learning emerge [35], the accessibility and implementation efficiency of these methods will continue to improve, further accelerating scientific discovery through more reliable synthesizability predictions.

The discovery of new functional materials is a cornerstone of technological advancement, from developing better battery components to novel pharmaceuticals. For decades, computational materials science has employed quantum mechanical calculations, particularly density functional theory (DFT), to predict millions of hypothetical materials with promising properties. However, a significant bottleneck remains: most theoretically predicted materials have never been synthesized in a laboratory. The critical challenge lies in accurately predicting crystal structure synthesizability—whether a proposed material can actually be created under practical experimental conditions [3].

Traditional approaches to assessing synthesizability have relied on proxies such as thermodynamic stability, often measured as the energy above the convex hull (E_hull), or kinetic stability through phonon spectrum analysis. However, these metrics frequently fall short; many materials with favorable formation energies remain unsynthesized, while various metastable structures with less favorable energies are successfully synthesized [3]. This discrepancy highlights the complex, multifaceted nature of material synthesis that extends beyond simple thermodynamic considerations to include kinetic barriers, precursor selection, and specific reaction pathways.

The emerging paradigm of using artificial intelligence, particularly large language models (LLMs), offers a transformative approach to this challenge. By learning patterns from extensive experimental synthesis data, these models can capture the complex relationships between crystal structures, synthesis conditions, and successful outcomes. The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models (CSLLM) framework represents a groundbreaking advancement in this domain, demonstrating unprecedented accuracy in predicting synthesizability and providing practical guidance for experimental synthesis [3].

CSLLM Architecture and Methodology

The CSLLM framework addresses the challenge of crystal structure synthesizability through a specialized, multi-component architecture. Rather than employing a single monolithic model, CSLLM utilizes three distinct LLMs, each fine-tuned for a specific subtask in the synthesis prediction pipeline [3]:

- Synthesizability LLM: Predicts whether an arbitrary 3D crystal structure can be synthesized.

- Method LLM: Classifies possible synthetic methods (e.g., solid-state or solution routes).

- Precursor LLM: Identifies suitable chemical precursors for solid-state synthesis.

This modular approach allows each component to develop specialized expertise, resulting in significantly higher accuracy than a single model attempting to address all aspects simultaneously.

Data Curation and Representation

A critical innovation underlying CSLLM's performance is its comprehensive dataset and novel representation scheme for crystal structures. The training data consists of 70,120 synthesizable crystal structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) and 80,000 non-synthesizable structures identified from a pool of 1,401,562 theoretical structures using a positive-unlabeled (PU) learning model [3]. This balanced dataset covers seven crystal systems and elements 1-94 from the periodic table, providing broad chemical diversity [3].

To efficiently represent crystal structures for LLM processing, the researchers developed a text-based "material string" representation. This format integrates essential crystallographic information—space group, lattice parameters, atomic species, and Wyckoff positions—in a compact, reversible text format that eliminates redundancies present in conventional CIF or POSCAR formats [3].

Model Training and Fine-tuning

The LLMs within CSLLM were fine-tuned on this curated dataset using the material string representation. This domain-specific fine-tuning aligns the models' general linguistic capabilities with the specialized domain of crystallography, refining their attention mechanisms to focus on material features critical to synthesizability. This process significantly reduces the "hallucination" problem common in general-purpose LLMs, ensuring predictions are grounded in materials science principles [3].

Performance Comparison: CSLLM vs. Alternative Methods

Quantitative Accuracy Assessment

The performance of CSLLM was rigorously evaluated against traditional synthesizability screening methods and other machine learning approaches. The results demonstrate a substantial advancement in prediction accuracy, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

| Method | Accuracy | Scope | Additional Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSLLM (Synthesizability LLM) | 98.6% [3] | Arbitrary 3D crystal structures [3] | Predicts methods & precursors [3] |

| Thermodynamic (E_hull ≥ 0.1 eV/atom) | 74.1% [3] | All structures with DFT data | Limited to energy stability |

| Kinetic (Phonon ≥ -0.1 THz) | 82.2% [3] | Structures with phonon calculations | Limited to dynamic stability |

| Teacher-Student NN | 92.9% [3] | 3D crystals | Synthesizability only |

| Positive-Unlabeled Learning | 87.9% [3] | 3D crystals [3] | Synthesizability only |

| Solid-State PU Learning | Varies by system [32] | Ternary oxides [32] | Solid-state synthesizability only |

CSLLM's near-perfect accuracy of 98.6% substantially outperforms traditional stability-based methods by more than 20 percentage points. This remarkable performance advantage persists even when evaluating structures with complexity significantly exceeding the training data, demonstrating exceptional generalization capability [3].

The framework's specialized components also excel in their respective tasks. The Method LLM achieves 91.0% accuracy in classifying synthetic methods, while the Precursor LLM attains 80.2% success in identifying appropriate solid-state precursors for binary and ternary compounds [3].

Comparison with Other Data-Driven Approaches

Other machine learning approaches have shown promise but with notable limitations. Positive-unlabeled (PU) learning methods have been applied to predict solid-state synthesizability of ternary oxides using human-curated literature data [32]. While effective for their specific domains, these approaches typically focus on synthesizability assessment without providing guidance on synthesis methods or precursors.

The key advantage of CSLLM lies in its comprehensive coverage of the synthesis planning pipeline. By predicting not just whether a material can be synthesized but also how and with what starting materials, it provides significantly more practical value to experimental researchers.

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Dataset Construction Methodology

The experimental validation of CSLLM followed a rigorous protocol with multiple stages. For dataset construction, synthesizable structures were carefully curated from the ICSD, including only ordered structures with ≤40 atoms and ≤7 different elements [3]. Non-synthesizable examples were identified by applying a pre-trained PU learning model to theoretical structures from major materials databases (Materials Project, Computational Material Database, Open Quantum Materials Database, JARVIS), selecting the 80,000 structures with the lowest confidence scores (CLscore <0.1) as negative examples [3]. This threshold was validated by showing that 98.3% of known synthesizable structures had CLscores >0.1.

Model Training and Evaluation Protocol

For model training, the dataset was split into training and testing sets. Each LLM was fine-tuned using the material string representation of crystal structures. Performance was evaluated on held-out test data using standard classification metrics (accuracy, precision, recall) [3].

The generalization capability was further tested on additional structures with complexity exceeding the training data, including those with large unit cells. The Synthesizability LLM maintained 97.9% accuracy on these challenging cases, demonstrating robust performance beyond its training distribution [3].

Validation Against Experimental Synthesis Data

In practical application, CSLLM was used to assess the synthesizability of 105,321 theoretical structures, identifying 45,632 as synthesizable [3]. These predictions provide valuable targets for experimental validation, though comprehensive laboratory confirmation of all predictions remains ongoing.

Table 2: Key Research Resources for AI-Driven Synthesizability Prediction

| Resource | Type | Function in Research | Relevance to CSLLM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [3] | Database | Source of confirmed synthesizable structures | Provided positive training examples [3] |

| Materials Project [3] [32] | Database | Repository of theoretical structures | Source of candidate non-synthesizable structures [3] |

| Positive-Unlabeled Learning Models [3] [32] | Algorithm | Identifies non-synthesizable examples from unlabeled data | Critical for negative dataset construction [3] |

| Material String Representation [3] | Data Format | Text-based crystal structure encoding | Enabled efficient LLM fine-tuning [3] |

| Graph Neural Networks [38] | AI Model | Predicts material properties | Complementary to CSLLM for property prediction [3] |

CSLLM Workflow and Architecture Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of the CSLLM framework, showing how its three specialized LLMs operate in concert to provide comprehensive synthesis guidance.

CSLLM Framework Workflow

The development of Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models represents a paradigm shift in computational materials science. By achieving 98.6% accuracy in synthesizability prediction—significantly outperforming traditional stability-based methods—while simultaneously providing guidance on synthesis methods and precursors, CSLLM addresses critical bottlenecks in materials discovery [3].

This capability is particularly valuable for drug development and pharmaceutical research, where the crystallform of an active pharmaceutical ingredient can significantly impact solubility, bioavailability, and stability [39]. The ability to accurately predict synthesizable crystal structures helps derisk the development process and avoid potentially disastrous issues with late-appearing polymorphs.

Future advancements in this field will likely focus on expanding the chemical space covered by these models, incorporating more detailed synthesis parameters (temperature, pressure, atmosphere), and integrating with high-throughput experimental validation systems. As these AI-driven approaches continue to mature, they will increasingly serve as indispensable tools for researchers navigating the complex journey from theoretical material design to practical synthesis and application.

Integrating Compositional and Structural Models for Unified Scores