Beyond Classical Theory: Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation as a Paradigm Shift in Biomineralization Research

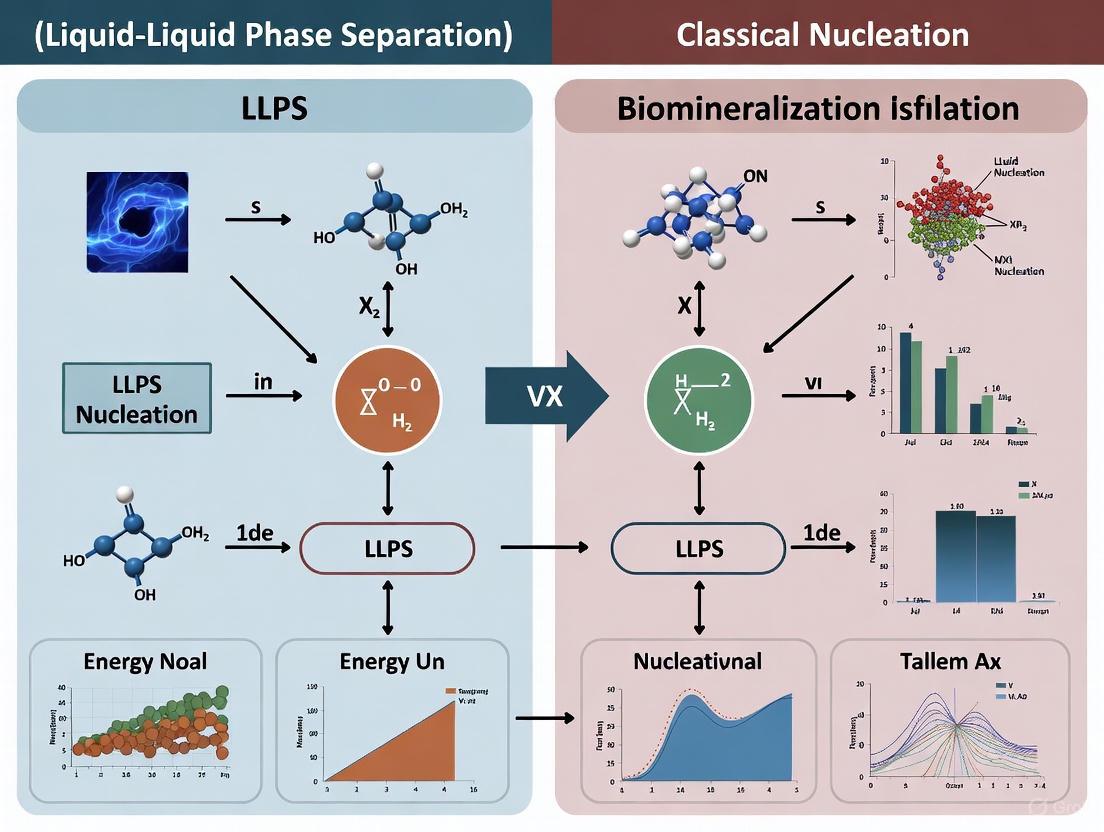

This article explores the paradigm shift from classical nucleation theory (CNT) to non-classical pathways centered on liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) in biomineralization.

Beyond Classical Theory: Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation as a Paradigm Shift in Biomineralization Research

Abstract

This article explores the paradigm shift from classical nucleation theory (CNT) to non-classical pathways centered on liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) in biomineralization. Targeting researchers and drug development professionals, it synthesizes foundational concepts, examining the limitations of CNT and the evidence for LLPS across mineral systems like calcium carbonate and phosphates. The scope extends to cutting-edge methodologies for observing these transient precursors, the significant experimental challenges in their characterization, and the application of this knowledge in designing biomimetic medical materials. By providing a comparative analysis of theoretical frameworks and validating LLPS mechanisms through recent studies, this review aims to bridge fundamental science with clinical innovation in tissue regeneration and therapeutic delivery.

From Classical Steps to Liquid Droplets: Redefining Biomineral Nucleation

The Limitations of Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) in Biological Systems

Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) has long provided a fundamental framework for understanding the initial stages of phase transitions, from the condensation of vapors to the crystallization of solids from solution. Its core premise is that the formation of a new phase is governed by a single energy barrier, which arises from the competition between the unfavorable surface energy of creating a new interface and the favorable bulk energy of forming the more stable phase. The critical nucleus, a cluster of a specific size, represents the top of this barrier; clusters smaller than this critical size tend to dissolve, while larger ones are likely to grow [1] [2]. This model offers an elegant, macroscopic explanation for nucleation kinetics. However, the breathtaking complexity and intricate control exhibited by biological mineralization processes (biomineralization)—such as the formation of bones, teeth, and mollusk shells—increasingly challenge the simplifying assumptions of CNT. Within the context of modern biomineralization research, a paradigm shift is occurring, moving away from a purely classical view towards one that incorporates non-classical pathways, most notably those involving liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) and pre-nucleation clusters (PNCs). This guide objectively compares the performance of the classical model against these non-classical alternatives, providing experimental data and methodologies that underscore the limitations of CNT in explaining the nuanced phenomena observed in living systems.

Core Limitations of CNT in Biological Environments

The application of CNT to biological systems reveals several significant shortcomings. These limitations primarily stem from CNT's macroscopic, equilibrium-based assumptions, which often break down at the molecular level and in the crowded, heterogeneous environments within organisms.

- Oversimplification of Nuclei Structure: CNT assumes that nascent nuclei are spherical, possess a uniform interior density identical to the bulk stable phase, and are separated by a sharp interface with a constant surface tension [1]. In reality, biological precursors are often non-spherical, chemically heterogeneous, and diffuse. For instance, in biomineralization, precursors like polymer-induced liquid precursors (PILPs) are liquid-like and lack a defined crystalline structure [1].

- Neglect of Stable Intermediate Species: A fundamental shortcoming of CNT is its failure to account for the existence of thermodynamically stable or metastable intermediates that precede the final crystalline phase. Research over the past two decades has conclusively shown that many minerals form through multi-step processes involving ion pairs, charged triple-ion clusters, and pre-nucleation clusters (PNCs) [3]. These PNCs, which are stable associated states of ions present before nucleation, have been observed for calcium carbonate, calcium phosphates, and iron oxides, yet they have no place in the classical model [3].

- Inability to Explain Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation (LLPS): A mounting body of evidence reveals that liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) plays a crucial role in the non-classical nucleation processes of many biominerals [1]. In this pathway, a homogeneous solution first separates into solute-rich and solute-poor liquid phases. The solute-rich droplets then act as precursors where nucleation can occur, a process that fundamentally differs from the single-step mechanism of CNT. These liquid intermediates can be either metastable, eventually transforming into a solid phase, or stable, remaining as a homogeneous liquid for extended periods [4]. This phenomenon is irreconcilable with CNT's direct path from solution to crystal.

- Insensitivity to Specific Molecular Interactions: CNT treats the nucleating system as a continuum, largely ignoring the specific chemical interactions—such as hydrogen bonding, electrostatic forces, and stereochemical complementarity—between organic molecules (proteins, peptides, sugars) and inorganic ions [2] [5]. In biomineralization, these interactions are not mere modifiers; they are the principal mechanisms by which organisms exert exquisite control over nucleation sites, crystal polymorphs, and ultimate mineral morphology [2].

Table 1: Core Conceptual Limitations of CNT in Biological Systems

| Limitation | CNT Assumption | Biological Reality | Key Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclei Structure | Spherical clusters with sharp interface and constant surface tension. | Amorphous, liquid-like, or chemically heterogeneous precursors with diffuse interfaces. | Observation of Polymer-Induced Liquid Precursors (PILPs) in calcium carbonate formation [1]. |

| Reaction Pathway | Single-step, direct formation of the stable phase. | Multi-step pathways via stable intermediates. | Identification of pre-nucleation clusters (PNCs) in calcium carbonate and phosphate systems [3]. |

| Role of Liquids | No role for liquid intermediates. | Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation (LLPS) is a common precursor. | Characterization of stable and metastable LLPS in citicoline sodium and protein systems [1] [4]. |

| Template Effects | Homogeneous or simple heterogeneous nucleation. | Complex recognition by organic matrices controls nucleation. | Proteins in bone and nacre templating nucleation via geometric and electrostatic complementarity [2] [5]. |

Quantitative Comparison: CNT vs. Non-Classical Pathways

The conceptual differences between classical and non-classical nucleation translate into distinct, measurable parameters. The following table and experimental data highlight these differences, providing a quantitative basis for comparison.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Nucleation Pathways

| Parameter | Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) | Non-Classical Pathways (LLPS & PNCs) |

|---|---|---|

| Free Energy Profile | Single activation barrier [3]. | Multi-step profile with multiple local minima and barriers [3]. |

| Critical Size Definition | A specific cluster radius (( r{crit} = -2\gamma / \Delta G\nu )) [1]. | Often a dynamic liquid droplet or a stable cluster of ions, not defined by a simple radius. |

| Dependence on Supersaturation | Nucleation rate is a sensitive function of supersaturation. | Nucleation may occur at lower effective supersaturation within dense liquid phases [1]. |

| Intermediate Species | None; only sub-critical and super-critical clusters. | Ion pairs, solvent-shared ion pairs, Charged Triple-Ion Clusters (CTICs), PNCs [3]. |

| Experimental Signature | Sigmoidal kinetics with a defined lag time [6]. | Observation of dense liquid droplets or stable clusters prior to crystal appearance [1] [4]. |

Supporting Experimental Data

Free Energy Calculations: The free energy cost of forming a spherical nucleus according to CNT is given by: [ \Delta G = \frac{4}{3}\pi r^3\rhos\Delta\mu + 4\pi r^2\gamma ] where ( \rhos ) is the solid number density, ( \Delta\mu ) is the chemical potential difference (the driving force, <0), and ( \gamma ) is the surface tension [2]. This produces a single energy barrier. In contrast, non-classical pathways inhabit a more complex free energy landscape with several valleys, representing stable intermediates like ion pairs and PNCs, separated by kinetic barriers [3].

Lag Time in Virus Capsid Assembly: CNT-based analysis of virus capsid assembly, which is treated as a nucleation-and-growth process, predicts a distinct lag time before a significant production of capsids is observed. The lag time and steady-state nucleation rate are sensitive functions of the concentration of coat proteins and the binding energy, which is itself dependent on ambient conditions like pH and ionic strength [6]. This sigmoidal kinetics is a hallmark of a nucleation-limited process, though the fixed size of capsids introduces non-universal scaling behavior that deviates from simple CNT predictions [6].

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Non-Classical Nucleation

To move beyond CNT, researchers employ a suite of advanced techniques capable of probing the early stages of nucleation and detecting metastable intermediates.

Protocol: Differentiating Stable and Metastable LLPS

Objective: To characterize and distinguish between stable and metastable Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation in a model system like citicoline sodium [4].

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare a homogeneous aqueous solution of the target molecule (e.g., citicoline sodium).

- Use two different antisolvents: one that induces stable LLPS (e.g., acetone) and another that induces metastable LLPS (e.g., ethanol).

Process Induction and Monitoring:

- Gradually add the antisolvent to the aqueous solution under controlled stirring and temperature (e.g., 30°C).

- Use Process Analytical Technologies (PAT) such as:

- Focused Beam Reflectance Measurement (FBRM): To track the chord length distribution and count particles, identifying the point of phase separation and subsequent solid formation.

- Particle Vision Measurement (PVM): To visually confirm the formation of liquid droplets and their evolution.

Phase Diagram Construction:

- For each antisolvent system, determine the binodal curve (the boundary between homogeneous solution and the LLPS region) by identifying the cloud point at various compositions.

- For the metastable system (ethanol), further identify the conditions under which the liquid droplets spontaneously transform into solid crystals.

Mechanistic Analysis:

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation: Model the solvation state of solute molecules in the presence of different antisolvents. Simulations have indicated that a solvation-enhanced state correlates with stable LLPS, while a desolvation state leads to metastable LLPS [4].

- Spectroscopy: Use Raman spectroscopy to analyze the molecular conformation and state of solute molecules within the liquid intermediates. Molecules in a metastable liquid intermediate often exhibit characteristics of a metastable state [4].

Protocol: Identifying Prenucleation Clusters (PNCs)

Objective: To detect and characterize the formation of pre-nucleation clusters in a mineral system like calcium carbonate [3].

Solution Preparation: Prepare a supersaturated solution of the mineral of interest (e.g., by mixing calcium chloride and sodium carbonate solutions) under conditions that inhibit immediate precipitation.

Probing PNCs:

- Analytical Ultracentrifugation (AUC): This technique can separate and quantify different species in solution based on their sedimentation velocity, allowing for the direct detection of PNCs that are larger than ion pairs but smaller than amorphous nanoparticles.

- Potentiometric Titration and Ion-Selective Electrodes: Monitor the free ion activity during titration. A deviation from the behavior expected for free ions indicates the presence of associated species like PNCs.

- Mass Spectrometry: In some systems, specialized mass spectrometry techniques can be used to identify the specific stoichiometry of charged clusters, such as positively charged ([Ca2CO3]^{2+}) or negatively charged ([Ca(CO3)2]^{2-}) clusters in calcium carbonate solutions [3].

- Computational Methods: Employ molecular dynamics or metadynamics simulations to model the free energy landscape of ion association, predicting the stability and structure of PNCs and other intermediates like solvent-separated and contact ion pairs [3].

Pathway Visualization: From Ions to Crystals

The following diagrams, generated using DOT language, illustrate the fundamental differences between the classical and non-classical nucleation pathways.

Classical vs. Non-Classical Nucleation Free Energy Landscape

Multi-Step Nucleation Pathway in Biomineralization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successfully investigating the limitations of CNT requires specific tools and reagents designed to probe non-equilibrium and intermediate states.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Non-Classical Nucleation Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Model Biomineralization Molecules | To study nucleation pathways under controlled, biomimetic conditions. | Citicoline sodium (for LLPS studies) [4]; Acidic amino acids (Asp, Glu) for chiral crystal control [1]. |

| Recombinant Proteins from Biominerals | To isolate the role of specific organic matrices in templating nucleation. | Recombinant nacre proteins (e.g., Pif80) for studying Ca2+-protein coacervates [1]. |

| Process Analytical Technology (PAT) | To monitor the nucleation process in real-time, tracking the appearance and evolution of intermediates. | Focused Beam Reflectance Measurement (FBRM) and Particle Vision Measurement (PVM) [4]. |

| Divalent Cations (Hofmeister Series) | To probe ion-specific effects in triggering or modulating nucleation, especially in protein crystallization. | Mg2+, Ca2+ for inducing 2D protein crystals; Zn2+, Cu2+ for studying aggregation [7]. |

| Computational Chemistry Software | To model the free energy landscape of ion association and the molecular dynamics of LLPS. | Software for Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to analyze solvation/desolvation states [4] [3]. |

| Antisolvents for LLPS Studies | To induce phase separation and study the stability of liquid precursors. | Acetone (for stable LLPS) and Ethanol (for metastable LLPS) in citicoline sodium systems [4]. |

Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation (LLPS) has emerged as a crucial physicochemical process that challenges long-held classical views of nucleation, particularly in the field of biomineralization. This ubiquitous non-classical pathway enables the formation of complex, hierarchical mineral structures found in biological systems—from mollusk shells to vertebrate bones—through mechanisms that defy traditional crystallization models [1] [8]. LLPS describes the phenomenon where a homogeneous solution spontaneously separates into two distinct liquid phases with different compositions and properties: a dense, solute-rich phase and a dilute, solute-poor phase [9]. Within biomineralization research, this process facilitates the creation of membrane-less compartments that concentrate mineral precursors and organic molecules, providing a controlled environment for the nucleation and growth of biominerals with exceptional precision and organization [10].

The significance of LLPS extends across multiple disciplines, representing a paradigm shift in our understanding of how living organisms orchestrate mineral formation. While classical nucleation theory (CNT) has long served as the fundamental framework for explaining crystal formation, a growing body of evidence reveals its limitations in accounting for the complex, biologically-controlled mineralization processes observed in nature [1] [8]. The non-classical pathway involving LLPS offers a more comprehensive explanation for how organisms achieve precise spatial and temporal control over mineral deposition, enabling the creation of sophisticated structural materials with remarkable mechanical properties that often surpass their synthetic counterparts [11].

Theoretical Framework: Classical Versus Non-Classical Nucleation

Limitations of Classical Nucleation Theory

Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) has traditionally dominated the understanding of crystal formation from solution. According to CNT, nucleation occurs through stochastic fluctuations where dissolved ions or molecules assemble into spherical clusters, with the system needing to overcome a defined free-energy barrier [1] [8]. This energy barrier, described by the equation ΔGcrit = (16πγp³)/(3ΔGν²), where γp represents interface energy and ΔG_ν represents bulk energy, determines the critical nucleus size that must be reached for a crystal to become stable and continue growing [1]. CNT simplifies nucleation into two categories: homogeneous (occurring spontaneously in solution) and heterogeneous (occurring on foreign surfaces that lower the energy barrier) [1].

However, the rapid development of experimental techniques has revealed numerous shortcomings of CNT, particularly in explaining biomineralization processes. The theory's oversimplified assumptions—including uniform interior densities of nuclei, ignorance of curvature dependence on surface tension, and neglect of collisions between pre-existing clusters—limit its applicability to complex biological systems [1] [8]. Mounting experimental evidence shows that CNT-predicted nucleation processes often do not align with observed results in biomineralization, creating a critical knowledge gap in understanding how organisms control crystal formation with such remarkable precision [1].

LLPS as a Non-Classical Nucleation Pathway

The non-classical nucleation theory introduces a fundamentally different pathway where crystal formation proceeds through metastable precursor phases rather than direct assembly of ions into crystalline lattices [1] [8]. In this framework, LLPS serves as a crucial intermediate step, creating a solute-rich liquid phase that concentrates mineral precursors and significantly reduces nucleation energy barriers compared to classical pathways [1]. This mechanism enables organisms to exert sophisticated control over mineral formation through organic molecules that guide and regulate the phase separation process [10].

The thermodynamic advantage of LLPS-driven nucleation lies in its two-step energy landscape. Instead of overcoming the large single energy barrier described by CNT (ΔGcrit), the system first surmounts a much smaller barrier (ΔG1) to form dense liquid droplets via LLPS, then overcomes a second reduced barrier (ΔG_2) for nucleation within these concentrated environments [1] [8]. This sequential pathway dramatically increases nucleation rates compared to single-step classical nucleation, explaining the efficiency and precision of biological mineralization processes [1].

Table 1: Key Differences Between Classical and Non-Classical Nucleation Pathways

| Feature | Classical Nucleation Theory | LLPS-Based Non-Classical Nucleation |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Process | Single-step assembly from solution | Multi-step process through metastable precursors |

| Energy Barrier | Single large barrier (ΔG_crit) | Two smaller sequential barriers (ΔG1, ΔG2) |

| Nucleation Site | Throughout solution or on foreign surfaces | Within dense liquid droplets |

| Role of Polymers | Minor influence on energy barriers | Essential drivers of liquid phase formation |

| Structural Control | Limited to crystal modification | Precise morphological control through confinement |

| Precursor Species | Ions and ion clusters | Prenucleation clusters, amorphous nanoparticles |

Molecular Mechanisms and Key Players in LLPS

Intrinsically Disordered Proteins as Critical Scaffolds

Intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) serve as fundamental molecular drivers of LLPS in biomineralization systems. Unlike structured proteins with fixed three-dimensional configurations, IDPs lack stable secondary or tertiary structures and contain low-complexity domains (LCDs) with repetitive sequence elements that facilitate multivalent interactions [12] [10]. These proteins possess flexible regions enriched in specific amino acid residues—particularly aromatic (tyrosine, tryptophan) and hydrophobic (leucine, methionine) residues—that enable weak, transient interactions necessary for phase separation [12]. The multivalency of IDPs, characterized by multiple interacting domains or motifs, allows them to form complex interaction networks that exceed a critical threshold for phase separation [10].

The functional significance of IDPs in biomineralization is exemplified by their presence in various mineralizing systems. For instance, the matrix protein pif80 in molluscan nacre forms Ca²⁺-pif80 coacervates through LLPS, stabilizing and regulating the release of polymer-induced liquid precursor (PILP)-like amorphous calcium carbonate granules in intracellular vesicles [1] [8]. Similarly, IDPs are abundant components of otoliths (inner ear minerals) and other calcium carbonate biominerals, where they influence crystal morphology and nucleation pathways [10]. The structural flexibility of IDPs allows them to interact with numerous partners, including ions, nucleic acids, and other proteins, making them ideal regulators of complex processes like biomineralization [10].

The Role of Ions and Polymers in Modulating LLPS

Divalent cations, particularly calcium ions (Ca²⁺), play crucial roles in modulating LLPS processes in biomineralization. Recent research has revealed that divalent cations can directly influence protein phase behavior by affecting conformational states and promoting transient intermolecular cross-links [10]. For example, zinc ions strongly enhance the propensity of tau protein to undergo LLPS by lowering its critical concentration threshold, while calcium ions control the phase behavior of EF-hand domain protein 2 (EFhd2) and its interaction with tau [10]. In biomineralization systems, calcium ions interact with acidic polymers and IDPs to form complexes that undergo LLPS, creating environments conducive to mineral formation [1] [10].

Acidic polymers represent another critical component of LLPS-driven biomineralization. These polymers, often rich in aspartic acid or glutamic acid residues, interact with calcium ions through their negatively charged side chains, facilitating the formation of polymer-induced liquid precursors (PILPs) [1]. The PILP process, first identified by Gower et al., has revolutionized understanding of how organisms control crystal morphologies that deviate dramatically from equilibrium shapes [10]. These polymers not only initiate LLPS but also stabilize amorphous mineral precursors against uncontrolled crystallization, enabling their transport and deposition in specific locations before transitioning to crystalline phases [1] [10].

Diagram 1: Molecular drivers and processes in LLPS-mediated biomineralization. Intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs), polymers, calcium ions, and RNA participate in multivalent interactions that drive liquid-liquid phase separation, resulting in dense phases that concentrate precursors and provide confined environments for controlled crystallization.

Experimental Approaches for LLPS Investigation

Advanced Techniques for Detecting and Characterizing LLPS

Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching (FRAP) has served as a cornerstone technique for demonstrating the liquid-like properties of biomolecular condensates. This method involves photobleaching fluorescently labeled molecules within a defined region and monitoring the recovery of fluorescence due to the exchange of molecules between the bleached area and its surroundings [13]. While classical full-FRAP and partial-FRAP experiments provide information about dynamics, they cannot reliably distinguish LLPS from alternative mechanisms like interactions with clustered binding sites (ICBS) [14]. However, the development of half-FRAP experiments, where precisely half of a condensate is bleached, enables researchers to detect preferential internal mixing—a hallmark of LLPS [14]. In these experiments, the characteristic signature of LLPS appears as an increase in fluorescence in the bleached half coupled with a simultaneous decrease in the non-bleached half, indicating rapid internal rearrangement without extensive exchange across the phase boundary [14].

The emerging MOCHA-FRAP (Model-free calibrated half-FRAP) workflow represents a significant advancement in quantifying LLPS properties in living cells. This approach probes the strength of the interfacial barrier at condensate boundaries, which is responsible for preferential internal mixing [14]. MOCHA-FRAP has been applied to study components of various cellular structures, including heterochromatin foci, nucleoli, stress granules, and nuage granules, revealing that the strength of the interfacial barrier increases progressively across these systems [14]. Another innovative methodology, LLPS REDIFINE (REstricted DIFfusion of INvisible speciEs), offers a label-free, non-invasive approach to characterize biomolecular condensates using diffusion NMR measurements [15]. This technique exploits exchange dynamics between molecules in condensed and dispersed phases to determine diffusion constants, phase fractions, droplet radii, and exchange rates without requiring fluorescent tags that might alter protein behavior [15].

Practical Workflow for LLPS Experiments

A robust experimental workflow for investigating LLPS in biomineralization contexts involves multiple complementary approaches. The initial phase typically involves in vitro reconstitution using purified components (proteins, polymers, ions) to establish baseline phase separation behavior under controlled conditions [14]. This is followed by live-cell imaging to verify that observed phenomena occur in physiological contexts, utilizing techniques like half-FRAP to distinguish true LLPS from other clustering mechanisms [14]. For biomineralization systems, the critical step involves demonstrating functional consequences—showing that LLPS directly facilitates or controls mineral nucleation and growth, rather than representing an incidental byproduct [1] [10].

Table 2: Key Experimental Methods for LLPS Characterization

| Method | Key Measured Parameters | Applications in Biomineralization | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Half-FRAP/MOCHA-FRAP | Internal mixing dynamics, interfacial barrier strength | Testing if mineral precursors form liquid droplets | Distinguishes LLPS from binding artifacts | Requires fluorescent labeling |

| LLPS REDIFINE | Diffusion constants, droplet size, exchange rates | Characterizing precursor droplets without labels | Label-free, non-invasive | Limited to in vitro applications |

| 1,6-Hexanediol Treatment | Sensitivity of structures to aliphatic alcohol | Probing interaction types in mineral precursors | Simple implementation | Does not distinguish LLPS from ICBS |

| In Vitro Reconstitution | Phase diagrams, concentration thresholds | Establishing minimal components for mineralization | Controlled reductionist approach | May oversimplify complex systems |

Diagram 2: Experimental approaches for LLPS investigation. Different methodologies including FRAP, REDIFINE, and hexanediol treatment provide complementary data on dynamics, physical properties, and interaction types, enabling researchers to distinguish true LLPS from alternative mechanisms in biomineralization systems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for LLPS Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function in LLPS Research | Example Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs) | Scaffold molecules that drive phase separation | pif80 for nacre formation, otolith matrix proteins | Require recombinant expression and purification |

| Acidic Polymers | Induce polymer-induced liquid precursors (PILP) | Polyaspartate, polyglutamate for calcium carbonate mineralization | Length and charge density affect efficacy |

| Fluorescent Tags (GFP, YFP) | Enable visualization and FRAP experiments | Live-cell imaging of mineral precursor dynamics | May alter native protein behavior |

| 1,6-Hexanediol | Probe hydrophobic interactions in condensates | Testing sensitivity of mineral precursors | Does not distinguish LLPS from ICBS |

| Agarose Hydrogel | Stabilize droplets for prolonged observation | NMR studies of LLPS dynamics | Creates artificial environment |

| Divalent Cations | Modulate protein phase behavior | Calcium for carbonate/phosphate mineralization | Concentration critically affects phase boundaries |

Implications and Future Perspectives in Biomineralization Research

The recognition of LLPS as a fundamental process in biomineralization has transformative implications for both basic science and applied materials engineering. From a biological perspective, it provides a mechanistic framework for understanding how organisms create complex mineralized tissues with precise hierarchical organization—addressing long-standing questions about the formation of mollusk nacre, bone microstructure, and otolith patterning [1] [10] [8]. The LLPS paradigm explains how biological systems overcome nucleation barriers at near-neutral pH and low supersaturations where classical pathways would be inefficient or impossible [1].

In biomedical engineering, understanding LLPS mechanisms opens new avenues for designing innovative biomaterials. The principles of LLPS-driven mineralization are already inspiring developments in bone tissue engineering, tooth remineralization strategies, and biotemplated nanocarriers for targeted drug delivery [11]. By harnessing the capacity of LLPS to create highly organized structures from nanoscale to macroscale, researchers can develop materials with enhanced mechanical properties, biocompatibility, and functional integration [11]. Furthermore, the connection between dysregulated LLPS and pathological mineralization processes—such as gallstone formation and certain types of kidney stones—suggests potential therapeutic interventions that target phase separation mechanisms [1] [8].

Looking forward, several emerging technological vectors promise to advance our understanding and application of LLPS in biomineralization. These include superhydrophilic/hydrophobic interfacial engineering for controlling mineralization sites, hybrid composite systems that combine organic and inorganic components, and AI-optimized mineralization architectures [11]. The integration of advanced characterization techniques like REDIFINE with computational modeling and synthetic biology approaches will likely uncover deeper principles governing LLPS-mediated biomineralization, enabling unprecedented control over material synthesis and organization [11] [15]. As these multidisciplinary efforts converge, they will further establish LLPS as not merely an alternative pathway, but as a fundamental organizational principle bridging the living and mineral worlds.

The study of biomineralization has undergone a fundamental paradigm shift with the recognition of non-classical nucleation pathways, challenging the long-established Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT). Within this new framework, calcium carbonate (CaCO₃) has emerged as the seminal model system for understanding liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS), a process now regarded as critical in the formation of structured biominerals, from mollusk shells to sea urchin spines [1] [16] [17]. CNT, which posits a direct, single-step transformation from ions in solution to a stable crystalline solid, has proven insufficient to explain the complex, highly organized architectures of biological minerals [1]. The discovery that calcium carbonate crystallization frequently proceeds through a transient, dense liquid precursor has provided a powerful alternative explanation for how organisms exert exquisite control over mineral formation [16] [18].

This guide objectively compares the classical and non-classical nucleation pathways, using calcium carbonate as the primary reference point. We synthesize current experimental evidence, detail key methodologies, and present quantitative data that have established CaCO₃ as the foundational model for LLPS in mineral systems. Understanding this pathway is not merely of academic interest; it provides a blueprint for biomimetic materials synthesis and has implications for fields ranging from carbon sequestration to pharmaceutical development [18].

Classical vs. Non-Classical Nucleation: A Fundamental Comparison

The divergence between classical and non-classical nucleation represents a fundamental difference in understanding how the first crystalline solids emerge from solution.

The Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) Framework

Classical Nucleation Theory describes nucleation as a process driven by stochastic fluctuations where individual ions or molecules associate to form a critical nucleus. The global free energy (ΔG) of this nucleus is expressed as ΔG = 4/3πr³ΔGᵥ + 4πr²γ, where the bulk energy (ΔGᵥ) acts as the driving force, and the interface energy (γ) represents the resistance to nucleation [1]. The theory assumes that nuclei are dense, with uniform internal properties and a sharp interface with the solution. While CNT effectively describes many homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation processes in simple systems, a growing body of evidence, particularly from biomineralizing systems, shows that its oversimplified model often fails to match experimental observations [1] [19].

The Non-Classical Nucleation Framework and the Centrality of LLPS

Non-classical nucleation theory proposes a multi-step pathway where a metastable precursor phase appears before the formation of crystalline nuclei [1]. For calcium carbonate, this pathway is often initiated by LLPS, a physicochemical process where a well-mixed solution separates into a solute-rich, dense liquid phase and a solute-poor, dilute phase [1] [12]. This dense liquid phase (DLP) is a metastable precursor that can significantly reduce the nucleation free-energy barrier compared to the direct path described by CNT [1]. The subsequent steps typically involve the stabilization of this DLP into amorphous calcium carbonate (ACC), which then undergoes dehydration and final crystallization into one of the polymorphic forms of CaCO₃ (calcite, vaterite, or aragonite) [20] [18]. This mechanism, governed by stable prenucleation clusters (PNCs) rather than stochastic fluctuations, provides a more accurate description of the complex nucleation processes observed in nature and the laboratory [20].

Table 1: Core Principles of Classical vs. Non-Classical Nucleation in Calcium Carbonate Systems

| Feature | Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) | Non-Classical Nucleation (via LLPS) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Pathway | Single-step: Ions → Critical Nucleus → Crystal [1] | Multi-step: Ions → PNCs → Dense Liquid Phase (LLPS) → ACC → Crystal [1] [20] [18] |

| Nucleation Precursor | Metastable ion association (critical nucleus) [1] | Stable Prenucleation Clusters (PNCs) that undergo liquid-liquid demixing [20] |

| Governing Energetics | Overcome a single, high free-energy barrier (ΔG_crit) [1] |

Overcome a lower initial barrier (ΔG_1) to a metastable liquid state [1] |

| Key Intermediate | None | Polymer-Induced Liquid Precursor (PILP) or additive-free Dense Liquid Phase (DLP) [1] [16] [18] |

| Role of Polymers/Additives | May act as heterogeneous nucleation sites [1] | Can participate in and stabilize the LLPS process [1] [16] |

| Explanatory Power for Biominerals | Limited for complex biological structures [1] | High; explains fine-grained control and intricate morphologies [1] [17] |

Experimental Evidence and Methodologies for Studying LLPS in CaCO₃

The establishment of CaCO₃'s LLPS pathway rests on a body of evidence gathered through diverse and complementary experimental techniques.

Key Experimental Protocols

Researchers have developed several standard methods to induce and study calcium carbonate precipitation, allowing for control over parameters like supersaturation and pH.

- The Ammonia Diffusion Technique: Surfaces or solutions of CaCl₂ are exposed to vapors from decomposing ammonium carbonate ((NH₄)₂CO₃) in a closed environment. This method slowly releases CO₂, maintaining a constant pH and allowing for gradual nucleation and growth, which is ideal for observing intermediate phases [19] [16].

- Direct Mixing Method: Solutions of calcium chloride and sodium (bi)carbonate are mixed directly. This method allows for precise control over initial concentrations, injection speed, and pH (via titration), making it suitable for kinetic studies and techniques like stopped-flow spectroscopy [20] [16].

- Kitano Method: Crystallization is induced from a saturated calcium bicarbonate solution through the slow evaporation of water or a decrease in CO₂ partial pressure. This method can mimic certain geologically and biologically relevant conditions [16].

Core Analytical Techniques and Findings

A multi-pronged analytical approach is crucial for identifying and characterizing the transient liquid precursors.

- Cryogenic Transmission Electron Microscopy (Cryo-TEM): By rapidly freezing samples, this technique preserves transient liquid states. Cryo-TEM has consistently revealed emulsion-like, liquid-like structures in reactive mixtures prior to crystallization, providing direct visual evidence for a liquid precursor phase [16].

- Liquid-Phase TEM (LP-TEM): This allows for the direct observation of dynamic processes in solution. LP-TEM has been used to visualize the coalescence of calcium carbonate droplets, a key behavior confirming their liquid character [16].

- In Situ Spectroscopy:

- Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier-Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) Spectroscopy: Monitors chemical changes in real-time, such as the evolution of carbonate vibrational bands, tracking the transition from the dense liquid to ACC and finally to crystals [20] [18].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: Used to study ion association and diffusion dynamics within prenucleation clusters and the dense liquid phase, providing insight into the molecular-scale interactions that drive LLPS [16] [18].

- Potentiometric Titration and Ion-Selective Electrodes: These methods track the concentration of free calcium ions during crystallization. The changes in ion activity products help define the liquid-liquid binodal and spinodal limits, which are the boundaries of the metastable and unstable zones in the phase diagram, respectively [20] [19].

Table 2: Key Experimental Evidence for LLPS in Calcium Carbonate Nucleation

| Experimental Technique | Key Observation | Interpretation & Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Cryo-TEM & LP-TEM | "Liquid-like" or "emulsion-like" structures; droplet coalescence [16] | Direct visualization of a dense liquid precursor phase prior to solidification. |

| Potentiometric Titration | Variable solubility of Amorphous Calcium Carbonate (ACC) depending on mixing rate [20] | ACC forms by dehydration of a liquid precursor; its solubility is defined by the liquid-liquid spinodal and binodal limits. |

| Stopped-Flow ATR-FTIR | Minimum kinetics time constant at a specific Ion Activity Product (IAP) [20] | Identifies the liquid-liquid spinodal limit, where the phase separation barrier vanishes and kinetics are fastest. |

| Scattering & Microscopy | Solid deposits with "liquid-like" morphologies (e.g., droplets arrested during coalescence) [16] | Suggests that solidification occurred from a liquid intermediate. |

| In Situ TEM & Spectroscopy | Observation of a hydrated bicarbonate DLP transforming into hollow, then solid, ACC particles [18] | Elucidates the chemical evolution and solidification pathway of the dense liquid phase. |

Visualization of the Non-Classical Nucleation Pathway

The following diagram synthesizes the experimental data into a coherent non-classical nucleation pathway for calcium carbonate, highlighting the role of LLPS.

Non-classical nucleation pathway of calcium carbonate, from ions to crystals, driven by LLPS. PILP: Polymer-Induced Liquid Precursor.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Research into the LLPS pathway of calcium carbonate relies on a specific set of chemical reagents and materials to replicate and study the process.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Calcium Carbonate LLPS Studies

| Reagent / Material | Typical Function in Experiment | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium Source | Provides Ca²⁺ ions for reaction with carbonate. | Calcium chloride (CaCl₂); concentration controls supersaturation [19] [16]. |

| Carbonate Source | Provides CO₃²⁻ ions, often through controlled release. | Ammonium carbonate ((NH₄)₂CO₃) [19], Sodium carbonate (Na₂CO₃) [16], or Dimethyl carbonate [16]. |

| Acidic Polymers / Additives | To study and stabilize the Polymer-Induced Liquid Precursor (PILP) phase. | Poly(acrylic acid) [1] [16]; mimics acidic proteins in biomineralization, extending DLP lifetime [18]. |

| Functionalized Surfaces | To study heterogeneous nucleation and surface-directed crystallization. | Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs) with –COOH, –OH, –NH₂ termini [19]; different surfaces promote specific polymorphs and nucleation mechanisms. |

| Mineral Substrates | To investigate promotion of ikaite or anhydrous CaCO₃ nucleation. | Quartz or mica sheets; can significantly promote ikaite formation at low temperatures [21]. |

| Buffers & pH Modulators | To control solution pH, a critical parameter for PNC stability and polymorph selection. | Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) or hydrochloric acid (HCl) for titration [20] [16]; pH influences proto-ACC structure (e.g., proto-calcite vs. proto-vaterite) [20]. |

Calcium carbonate stands as the seminal and most comprehensively studied model for liquid-liquid phase separation in mineral systems. The extensive body of experimental evidence, derived from a suite of advanced in situ and ex situ techniques, firmly establishes a multi-step nucleation pathway via a dense liquid precursor. This non-classical pathway, which contrasts fundamentally with the direct route of Classical Nucleation Theory, provides a powerful explanatory framework for the controlled and intricate biomineralization processes observed in nature. The quantitative data, methodologies, and reagents detailed in this guide provide a foundation for researchers to further explore LLPS, not only in calcium carbonate but also in other mineral systems of biological, geological, and industrial importance.

The understanding of biomineralization has undergone a significant paradigm shift, moving beyond the limitations of Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) toward the recognition of non-classical, multi-step pathways. Within this new framework, Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation (LLPS) has emerged as a critical intermediate step, representing a physicochemical process where a well-mixed fluid separates into distinct, dense liquid precursor droplets and a dilute continuous phase [16] [8]. While extensively documented in organic and proteinaceous systems, the role of LLPS in inorganic mineral systems presents unique experimental challenges due to accelerated crystallization kinetics, often reducing the observable lifetime of precursors to milliseconds or seconds [16]. This review synthesizes the expanding inventory of mineral systems exhibiting LLPS behavior, focusing on oxalates, phosphates, and metallic nanoparticles, and provides a comparative analysis of the experimental evidence, methodologies, and confidence levels supporting these findings.

Comparative Evidence for LLPS Across Mineral Systems

The following table summarizes the current evidence and confidence levels for LLPS occurrence across diverse mineral systems, based on a critical analysis of the literature.

Table 1: Evidence and Confidence for LLPS in Various Mineral Systems

| Mineral System | Supporting Experimental Techniques | Key Observations | Reported Confidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium Carbonate (without additives) | Cryo-TEM, SEM, Liquid-Phase TEM, NMR, Molecular Dynamics [16] | Liquid-like morphologies, droplet coalescence, diffusion dynamics, "emulsion-like" structures [16] | Very High [16] |

| Cerium Oxalate | Cryo-TEM, SEM, Liquid-Phase TEM [16] | Liquid-like morphologies in bulk/porous matrices, observed droplet coalescence [16] | Very High [16] |

| Metallic Nanoparticles | Cryo-TEM, AFM, Liquid-Phase TEM [16] | Liquid-like morphologies, soft droplets on substrates, liquid-like dynamics [16] | Very High [16] |

| Calcium Phosphates (Apatite) | Cryo-TEM, SEM, Liquid-Phase TEM [16] | Liquid-like morphology, dense liquid observed via LP-TEM; amorphous precursors infiltrate collagen [16] [22] | Supportive [16] |

| Barium Sulfate | TEM (after ethanol quenching) [16] | Liquid-like morphologies in static images post-quenching [16] | Suggestive [16] |

| Sulfur Hydrosols | Macroscopic emulsion behavior [16] | Thermal behavior of an emulsion [16] | Suggestive [16] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Systems

Cerium Oxalate LLPS Protocol

- Objective: To observe and characterize liquid-liquid phase separation preceding crystallization in the cerium oxalate system.

- Materials: Aqueous solutions of cerium(III) chloride (CeCl₃) and sodium oxalate (Na₂C₂O₄).

- Methodology:

- Rapid Mixing: Solutions of CeCl₃ and Na₂C₂O₄ are rapidly mixed to achieve supersaturation.

- Cryo-Fixation: At specific time intervals (e.g., seconds post-mixing), a small aliquot of the reaction mixture is vitrified by plunging into a cryogen (e.g., liquid ethane) to freeze the transient structures.

- Cryo-Transmission Electron Microscopy (Cryo-TEM): The vitrified sample is transferred to a cryo-TEM under liquid nitrogen conditions. This allows for direct imaging of the liquid droplets formed via LLPS without crystallization artifacts from drying.

- Liquid-Phase TEM (LP-TEM): A microfluidic chamber is used to contain the reaction solution within the TEM. The process is observed in real-time, where direct visualization of droplet coalescence provides definitive evidence of liquid character [16].

- Key Data: Cryo-TEM images show spherical, liquid-like droplets. LP-TEM videos capture dynamic events where two droplets contact and merge into a single, larger droplet, confirming their fluid nature [16].

Calcium Phosphate / Apatite LLPS Protocol

- Objective: To investigate the formation of amorphous liquid precursors and their role in the crystallization of apatite, particularly within a collagen matrix.

- Materials: Calcium and phosphate-containing solutions (e.g., CaCl₂ and Na₂HPO₄), often with polymeric additives or non-collagenous proteins (NCPs) like poly-aspartic acid.

- Methodology:

- Precursor Formation: Solutions are mixed under conditions that favor the formation of an amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP) precursor.

- Stabilization: Polyelectrolytes such as negatively charged NCPs act to stabilize the highly hydrated, fluid ACP phase, preventing immediate crystallization [22].

- Infiltration: The fluidic ACP precursor phase infiltrates the nanoscopic gaps and grooves of collagen fibrils, drawn in by capillary action [22].

- Crystallization: Within the confined space of the collagen fibrils, the ACP dehydrates and crystallizes into oriented hydroxyapatite (HAP) platelets, mimicking the natural bone formation process [22].

- Characterization: LP-TEM can be used to observe the dense liquid phase early in the process. Subsequent analysis by SEM and TEM reveals the final mineralized composite structure [16] [22].

- Key Data: LP-TEM may show dense liquid droplets. The final composite material shows HAP crystals embedded within and aligned with the collagen fibrils, supporting the "amorphous precursor pathway" mediated by a liquid-like phase [16] [22].

Visualization of LLPS Experimental Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the general experimental workflow for studying LLPS in mineral systems, highlighting the two primary microscopy approaches.

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for LLPS Characterization. This diagram outlines the two primary pathways for characterizing mineral LLPS: cryo-TEM for high-resolution snapshots of frozen droplets, and liquid-phase TEM for direct, real-time observation of dynamic behavior like coalescence.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Techniques for LLPS Mineralization Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application in LLPS Research |

|---|---|

| Cryo-Transmission Electron Microscopy (Cryo-TEM) | Provides high-resolution, static images of liquid precursors by instantaneously freezing the solution, preserving native-state morphology [16]. |

| Liquid-Phase TEM (LP-TEM) | Enables real-time, in-situ observation of nucleation dynamics, including droplet formation, growth, and coalescence, directly confirming liquid character [16]. |

| Acidic Polymers (e.g., Poly-Aspartic Acid) | Induce and stabilize polymer-induced liquid precursors (PILPs), particularly in calcium carbonate and phosphate systems, mimicking biological control [16] [8]. |

| Non-Collagenous Proteins (NCPs) | Act as biomimetic regulators in phosphate systems; their negative charges stabilize amorphous precursors and guide infiltration into collagen scaffolds [22]. |

| Cryo-Focused Ion Beam SEM (Cryo-FIB-SEM) | Used to prepare thin lamellae from specific cellular or synthetic regions for cryo-electron tomography, allowing structural analysis in a near-native state [23]. |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy | Used to probe ion pairing and diffusion dynamics within pre-nucleation clusters and liquid precursors, providing insights into composition and behavior [16]. |

The inventory of mineral systems exhibiting LLPS is unequivocally expanding, with very high confidence now assigned to systems beyond the canonical calcium carbonate, including cerium oxalate and metallic nanoparticles. The study of LLPS is facilitated by a powerful suite of characterization techniques, with cryo-TEM and liquid-phase TEM being particularly definitive. The evidence supporting a role for liquid precursors in calcium phosphate mineralization is increasingly supportive, linking this non-classical pathway directly to the formation of biological apatite in bone. This growing body of work solidifies LLPS as a fundamental mechanism in non-classical nucleation, offering profound implications for the rational design of advanced materials and providing a new lens through which to understand both physiological and pathological mineralization processes.

Biomineralization, the process by which living organisms form minerals, has long been a subject of intense scientific interest. Traditional understanding of crystal formation was governed by classical nucleation theory (CNT), which posits that ions in solution directly assemble into a critical nucleus that then grows into a crystal through the sequential addition of monomers [8]. However, a paradigm shift has occurred with the recognition that many biomineralization processes follow non-classical pathways involving transient precursor phases [8]. This review examines the transformative role of organic molecules—from synthetic polymer additives to biological intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs)—in directing these pathways through the phenomenon of liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS).

The limitations of CNT have become increasingly apparent. As Deniz Erdemir and colleagues noted, CNT suffers from oversimplifications including the assumption that nuclei have uniform interior densities, ignorance of curvature dependence of surface tension, and neglect of collisions between pre-existing clusters [8]. In contrast, non-classical nucleation involves the formation of metastable precursor phases before the appearance of crystal nuclei [8]. LLPS has emerged as a crucial mechanism in this process, enabling the creation of highly organized biominerals with exceptional mechanical properties and biological functions [11] [10].

This review systematically compares how different classes of organic molecules influence biomineralization through LLPS, providing researchers with experimental frameworks and mechanistic insights to advance materials science and biomedical applications.

Fundamental Mechanisms: LLPS vs. Classical Nucleation

Theoretical Frameworks

The fundamental distinction between classical and non-classical nucleation pathways lies in their mechanisms and intermediate states. Classical nucleation theory describes a single-step process where ions or molecules in solution spontaneously form stable crystalline nuclei when a critical size is reached, overcoming a single energy barrier [8]. The free energy of nucleation (ΔG) in CNT is expressed as:

[ \Delta G = \frac{4}{3}\pi r^3\Delta G_v + 4\pi r^2\gamma ]

where (r) is the nucleus radius, (\Delta G_v) is the volume free energy change, and (\gamma) is the surface energy [8].

In contrast, non-classical nucleation via LLPS involves multiple steps with distinct energy landscapes. A homogeneous solution first separates into solute-rich and solute-poor liquid phases, creating a microenvironment where nucleation occurs with a reduced energy barrier [8]. This process frequently involves pre-nucleation clusters (PNCs) and amorphous precursors that subsequently transform into crystalline phases [11] [8].

Visualization of Nucleation Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the key differences between classical and non-classical nucleation pathways in biomineralization:

Polymer Additives in LLPS-Mediated Biomineralization

Polymer-Induced Liquid Precursors (PILP)

The polymer-induced liquid precursor (PILP) system, first introduced by Gower and colleagues, represents a foundational discovery in non-classical biomineralization [10] [8]. This process involves anionic polymers such as polyaspartic acid or polyacrylic acid that induce the separation of a liquid-phase mineral precursor from solution [8]. The PILP system demonstrates how simple organic polymers can mimic complex biological control over mineral formation.

The mechanism involves electrostatic interactions between negatively charged carboxylate groups on the polymer and positively charged calcium ions, leading to the formation of a dense, liquid-phase precursor that can be molded into non-equilibrium shapes before solidification [8]. This process enables the creation of complex morphologies that would be inaccessible through classical crystallization pathways.

Experimental Protocols for Polymer-Mediated LLPS

Table 1: Experimental Systems for Studying Polymer-Induced LLPS

| Mineral System | Polymer Additives | Experimental Conditions | Characterization Techniques | Key Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium carbonate | Polyaspartic acid, polyacrylic acid | Ammonia diffusion, direct mixing, Kitano method | SEM, cryo-TEM, AFM, NMR | Liquid-like droplets that coalesce and solidify into complex morphologies | [8] [16] |

| Calcium phosphate | Polyglutamic acid, phosphoproteins | Simulated body fluid, physiological pH | SEM, TEM, LP-TEM | Formation of polymer-stabilized amorphous precursors | [16] |

| Cerium oxalate | Not specified | Porous matrices, bulk solution | SEM, cryo-TEM, LP-TEM | Liquid-like morphologies with demonstrated droplet coalescence | [16] |

Standard protocol for observing polymer-induced LLPS in calcium carbonate:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare 5-20 mM calcium chloride solution and an equivalent concentration of sodium carbonate/bicarbonate solution. Add polyaspartic acid (MW 5-30 kDa) to the calcium solution at concentrations ranging from 0.01-1 mg/mL [16].

- Mixing Method: Combine solutions using either (a) direct mixing with rapid pipetting, (b) ammonia diffusion technique, or (c) Kitano method (slow evaporation from calcium bicarbonate solution) [16].

- Time-Resolved Observation: Monitor immediately after mixing using light microscopy for droplet formation. For electron microscopy, apply rapid freezing (cryo-TEM) or sample at timed intervals [16].

- Characterization: Analyze droplet morphology, coalescence behavior, and transformation to amorphous and crystalline phases using SEM, TEM, AFM, or NMR [16].

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for studying polymer-induced LLPS:

Intrinsically Disordered Proteins in Biological LLPS

Structural and Functional Properties of IDPs

Intrinsically disordered proteins represent a class of proteins that lack a stable three-dimensional structure under physiological conditions, existing instead as dynamic conformational ensembles [24] [25]. IDPs are characterized by their enrichment in polar and charged amino acids while being depleted in hydrophobic residues, which prevents traditional folding [25]. In the context of biomineralization, IDPs are overrepresented in mineralized tissues compared to the general proteome, suggesting their fundamental importance in controlling mineral formation [24] [26].

Key features of IDPs that facilitate their role in LLPS-mediated biomineralization include:

- Multivalency: The presence of multiple interaction domains enables the formation of complex, weak, transient interaction networks that drive phase separation [10] [25].

- Structural flexibility: IDPs can adopt various conformations to interact with different partners, including ions, mineral surfaces, and other proteins [24] [26].

- Post-translational modifications: Phosphorylation, glycosylation, and other modifications dramatically alter IDP charge states and interaction capabilities, providing regulatory control over mineralization [24] [26].

- Charge patterning: The specific arrangement of positive and negative charges along the protein chain determines phase separation propensity and material properties of the resulting condensates [25].

IDP-Driven LLPS in Different Mineral Systems

Table 2: IDP-Mediated LLPS in Biological Mineralization Systems

| Mineral System | Key IDPs | Biological Context | LLPS Characteristics | Biological Function | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium carbonate | Otolith matrix proteins, AP7 | Fish otoliths, mollusk shells | Ca²⁺-induced condensation, droplet maturation | Control of crystal polymorphism, morphological shaping | [10] [24] |

| Calcium phosphate (hydroxyapatite) | SIBLING family (OPN, BSP, DMP1, DSPP) | Bone, dentin formation | Phosphorylation-dependent separation, collagen interaction | Mineral nucleation, growth inhibition, tissue organization | [24] [26] |

| Calcium phosphate (enamel) | Amelogenin | Dental enamel | Nanosphere formation, liquid droplet assembly | Enamel prism organization, crystal alignment | [26] |

| Silica | Silaffins, silacidins | Diatom frustules | Phase-separated organic templates | Porous silica structure formation | [24] |

Experimental Approaches for IDP-Mediated LLPS

Standard protocol for investigating IDP-driven LLPS in biomineralization:

Protein Purification: Express and purify recombinant IDPs (e.g., amelogenin, osteopontin) using affinity chromatography with tags (His-tag, GST-tag). Maintain reducing conditions to prevent aggregation [24] [26].

In Vitro LLPS Assay:

- Prepare protein solutions at physiological concentrations (0.1-10 mg/mL) in appropriate buffers.

- Induce phase separation by adding calcium chloride (1-10 mM) or adjusting pH/salt concentration.

- Monitor droplet formation via light scattering, fluorescence microscopy with conjugated dyes, or differential interference contrast microscopy [10] [24].

Mineralization Assay:

- Incubate protein condensates with supersaturated mineral solutions (calcium carbonate, calcium phosphate).

- Control supersaturation levels to match physiological conditions.

- Monitor mineral formation within droplets using time-lapse microscopy, alkaline phosphatase activity assays (for phosphate minerals), or calcein staining (for calcium) [24] [26].

Characterization:

The following diagram illustrates the mechanistic role of IDPs in LLPS-mediated biomineralization:

Comparative Analysis: Polymer Additives vs. IDPs

Mechanistic Comparison

While both synthetic polymer additives and biological IDPs facilitate LLPS in biomineralization, they operate through distinct yet overlapping mechanisms. The following table provides a systematic comparison of their roles, mechanisms, and functional outcomes:

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Polymer Additives vs. IDPs in LLPS-Mediated Biomineralization

| Parameter | Synthetic Polymer Additives | Intrinsically Disordered Proteins |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Composition | Homogeneous repeating units (e.g., polyAsp, polyGlu) | Heterogeneous amino acid sequences with specific patterning |

| Interaction Mechanisms | Primarily electrostatic interactions with mineral ions | Multivalent weak interactions (electrostatic, π-π, hydrophobic) |

| Regulation | Concentration, molecular weight, charge density | Post-translational modifications, proteolytic processing, partner interactions |

| Liquid Precursor Stability | Hours to days | Tightly regulated temporal control (minutes to hours) |

| Biological Integration | Limited | Direct interaction with cellular machinery, matrix components |

| Specificity | Polymorph selection through surface energy modification | Precise crystal plane recognition, orientation control |

| Evolutionary Optimization | None | Millions of years of selection for function |

| Spatial Control | Limited to diffusion and surface interactions | Directed cellular secretion, compartmentalization |

| Information Content | Simple chemical information | Complex biological information encoding hierarchical structure |

Experimental Evidence and Validation

The distinct roles of polymer additives versus IDPs are supported by experimental observations across multiple mineralization systems:

Calcium carbonate formation: Polyaspartic acid induces liquid precursors that mold to container shapes, while otolith matrix proteins form species-specific otolith morphologies with precise control [10] [8] [16].

Bone mineralization: Synthetic polyelectrolytes can initiate hydroxyapatite formation, but SIBLING proteins like osteopontin and DMP1 provide spatiotemporal control integrated with cellular activity and collagen matrix organization [24] [26].

Enamel formation: Amelogenin IDPs self-assemble into nanospheres that guide the extraordinary organization of enamel rods, a level of structural hierarchy unattainable with synthetic polymers alone [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Methods for LLPS Biomineralization Research

| Category | Specific Reagents/Techniques | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Additives | Polyaspartic acid, polyacrylic acid, polyglutamic acid | Induce liquid precursor formation in model systems | Molecular weight, polydispersity, concentration critical for reproducibility |

| Mineral Precursors | Calcium chloride, sodium carbonate/bicarbonate, ammonium phosphate | Create supersaturated solutions for mineralization | Purity, mixing method, and ionic strength affect pathway selection |

| Characterization Techniques | Cryo-TEM, liquid-phase TEM, AFM, NMR, dynamic light scattering | Visualize and characterize liquid precursors and transformation | Cryo-TEM preserves native structure; LP-TEM may introduce artifacts |

| IDP Expression Systems | E. coli, mammalian cell lines | Produce recombinant IDPs for mechanistic studies | Post-translational modifications may require eukaryotic systems |

| Phase Separation Assays | Turbidity measurements, fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP), microfluidics | Quantify LLPS dynamics and material properties | FRAP assesses liquid character through recovery kinetics |

| Mineral Analysis | Raman spectroscopy, XRD, SAED, FTIR | Determine mineral phase, crystallinity, orientation | Complementary techniques provide complete structural picture |

| Molecular Probes | Calcein (calcium), fluorescently conjugated polymers/IDPs | Track mineral ion distribution and organic phase localization | Probe size and charge should not interfere with native process |

The comparison between synthetic polymer additives and intrinsically disordered proteins in LLPS-mediated biomineralization reveals both convergent mechanisms and distinct biological advantages. While synthetic polymers have been invaluable for establishing fundamental principles and enabling biomimetic materials synthesis, IDPs represent evolutionarily optimized systems that integrate mineralization with biological regulation.

Future research directions should focus on:

- Decoding IDP sequence-grammar to identify specific motifs that control phase behavior and mineral interaction.

- Developing synthetic IDP-mimetics that capture the functional advantages of biological systems while maintaining synthetic tractability.

- Engineering spatiotemporal control into polymer additive systems for advanced biomaterials fabrication.

- Elucidating the role of LLPS in pathological mineralization and developing therapeutic interventions.

The convergence of polymer science, biophysics, and molecular biology in understanding LLPS-driven biomineralization continues to provide transformative insights with applications ranging from regenerative medicine to advanced materials synthesis. As Vekilov noted, "two-step nucleation is by now ubiquitous and registered cases of classical nucleation are celebrated" [16], highlighting the fundamental shift in understanding that has positioned LLPS as a central mechanism in materials science and biomineralization.

Capturing Transient Phases: Techniques and Biomedical Applications of LLPS

The study of biomineralization—the processes by which living organisms form minerals—has undergone a paradigm shift. The long-standing model of classical nucleation theory, which posits an ion-by-ion addition pathway, has been increasingly challenged by observations of non-classical pathways involving metastable precursors [16] [27]. Among these, Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation (LLPS) has emerged as a critical intermediate step, representing a pre-nucleation stage where a dense, reactant-rich liquid phase separates from the surrounding solution [16]. This shift in understanding has been driven largely by advances in characterization tools capable of probing these transient, nanoscale phenomena. Cryogenic Transmission Electron Microscopy (Cryo-TEM), Liquid-Phase Transmission Electron Microscopy (Liquid-Phase TEM), and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy now allow researchers to capture and analyze these previously elusive processes. This guide provides an objective comparison of these techniques, framing their performance within the central scientific debate between LLPS and classical nucleation pathways in biomineralization research.

Tool Comparison: Principles, Capabilities, and Data

The following section compares the operational principles, key performance metrics, and specific applications of Cryo-TEM, Liquid-Phase TEM, and NMR Spectroscopy in biomineralization studies.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Advanced Characterization Techniques

| Feature | Cryo-TEM | Liquid-Phase TEM | NMR Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Vitrification of solution to preserve native-state structures for imaging in vacuum [27] | Real-time imaging of samples encapsulated in liquid cells with electron-transparent membranes [27] [28] | Detection of nuclear spin transitions in magnetic fields to probe local atomic environment and dynamics [29] [30] |

| Key Strength | High-resolution imaging of hydrated, near-native structures; avoids drying artifacts [27] | Direct, dynamic observation of reactions and processes in liquid phase [27] | Atomic-level structural and dynamic information; quantitative on bulk sample [29] |

| Spatial Resolution | Near-atomic (for single particle analysis) [31] | Nanometer-scale [27] | Atomic-scale (local structure), but no direct spatial image |

| Temporal Resolution | Static (millisecond freezing) [27] | Real-time (milliseconds to seconds) [16] [27] | Timescale of atomic dynamics (microseconds to seconds) |

| Primary Application in Biomineralization | Identifying and characterizing amorphous precursors, PILPs, and final crystal morphologies [16] [27] | Visualizing dynamic nucleation events, precursor formation, and transformation pathways [27] | Probing the structure and coordination chemistry of amorphous precursors and crystalline phases [30] |

| Key Experimental Evidence for LLPS | "Liquid-like" droplet morphologies and coalescence in CaCO₃, cerium oxalate, and apatite systems [16] | Direct video of droplet coalescence, growth, and crystallization in CaCO₃ and other minerals [16] [27] | Detection of distinct local calcium environments in amorphous precursors, supporting a dense liquid phase [30] |

Table 2: Technical Specifications and Practical Considerations

| Feature | Cryo-TEM | Liquid-Phase TEM | NMR Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Environment | Cryogenic (liquid nitrogen), vitrified ice [27] | Liquid, room temperature (or controlled) [28] | Liquid or solid-state, room temperature (or controlled) [29] |

| Sample Preparation Complexity | High (vitrification requires optimization) [27] | Moderate (liquid cell assembly and conditioning) [27] [28] | Low to Moderate (depending on isotope enrichment) |

| Radiation Damage Concerns | Moderate (minimized by low dose and cryo-condition) [27] | High (electron beam effects on sample and liquid, causing radiolysis) [27] [28] | None |

| Key Limitation | Only provides a "snapshot" of a dynamic process [27] | Electron beam can interfere with the natural process being observed [16] [28] | Inherently low sensitivity, especially for low-yield nuclei like ⁴³Ca [30] |

| Recent Technical Advance | Ultra-stable gold supports and graphene coatings to reduce beam-induced motion [32] | Improved silicon nitride membrane cells and graphene liquid cells [27] [28] | Ultra-high magnetic fields (≥23.5 T) for enhanced sensitivity and resolution [30] [33] |

Experimental Protocols for Biomineralization Research

Cryo-TEM for Capturing Transient Precursors

This protocol is designed to capture and stabilize transient mineralization precursors, such as those formed via LLPS, in a near-native state for Cryo-TEM analysis [27] [31].

- Sample Preparation: A common method for calcium carbonate studies involves the direct mixing of an aqueous calcium chloride solution with a sodium (bi)carbonate solution, allowing control over concentrations and initial pH [16].

- Grid Preparation: Apply a 3-5 µL aliquot of the reaction solution at a desired time point onto a freshly glow-discharged holey carbon grid (e.g., Quantifoil) [31].

- Vitrification: Using a vitrification device (e.g., FEI Vitrobot), blot the grid to create a thin liquid film (typically <1 µm) and rapidly plunge it into a cryogen (liquid ethane cooled by liquid nitrogen) to form vitreous ice [27] [31]. Key parameters include blot time (e.g., 2-6 seconds), humidity (>90%), and temperature (e.g., 4°C) [31].

- Data Collection: Transfer the grid under cryogenic conditions to a Cryo-TEM equipped with a direct electron detector (e.g., Gatan K3). Automated data collection software (e.g., EPU, SerialEM) is used to acquire images with a low electron dose (e.g., 50 e⁻/Ų) to minimize radiation damage [31]. The "Faster acquisition" mode in EPU, which minimizes stage movements, can significantly increase throughput without compromising resolution [31].

Liquid-Phase TEM for In Situ Dynamics

This protocol enables the real-time observation of biomineralization events, allowing researchers to distinguish between classical and non-classical growth [27].

- Liquid Cell Assembly: A commercial silicon nitride-based liquid cell is typically used. The cell consists of two chips with thin electron-transparent silicon nitride membranes (e.g., 20-50 nm thick) that enclose the liquid sample [27] [28].

- Cell Loading and Sealing: Introduce a small volume (e.g., 0.5-1 µL) of the reaction solution into the liquid cell using a syringe or pipette, creating a sealed liquid layer a few micrometers thick [27].

- In Situ Reaction Initiation: Reactions can be initiated in several ways, including:

- Imaging and Data Acquisition: Operate the TEM in scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) mode or use low-dose TEM protocols to minimize electron beam effects on the process. Record movies to capture dynamic events like droplet formation, coalescence, and crystallization [27] [28].

Solid-State NMR for Atomic-Level Structure

This protocol is used to obtain atomic-level structural information about both amorphous and crystalline biominerals, which is crucial for characterizing precursors [30].

- Sample Preparation: For biomineral studies, samples are often packed into a magic-angle spinning (MAS) rotor. For hydrated or sensitive phases, samples may be preserved under cryogenic conditions or via DNP-NMR approaches to enhance sensitivity [29].

- Magnetic Field Strength: Use the highest magnetic field available. Ultra-high fields (e.g., 35.2 T, corresponding to a ¹H Larmor frequency of 1.5 GHz) are critical for studying challenging nuclei like ⁴³Ca due to significant gains in sensitivity and spectral resolution [30] [33].

- Data Acquisition:

- For ⁴³Ca NMR, experiments are performed at natural abundance due to the low natural abundance (0.135%) of this isotope. Use high-power decoupling and magic-angle spinning (MAS) to improve resolution [30].

- For ¹H or ³¹P NMR in bone studies, the enhanced sensitivity allows for the investigation of the organic-inorganic interface (e.g., collagen-hydroxyapatite interactions) [29] [34].

- Spectral Analysis: Isotropic chemical shifts and signal intensities provide information on the local atomic environment, coordination number, and the presence of distinct phases in complex mixtures [30].

Visualizing Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the logical progression and key decision points in the experimental workflows for the three characterization techniques.

Cryo-TEM Workflow for Precursor Capture - This workflow shows the rapid vitrification process used in Cryo-TEM to preserve transient states for static, high-resolution analysis.

Liquid-Phase TEM Workflow for Dynamics - This workflow illustrates the setup for Liquid-Phase TEM, enabling real-time observation of dynamic biomineralization processes.

NMR Spectroscopy Workflow for Atomic Structure - This workflow highlights the use of ultra-high field NMR to probe the atomic-scale structure of biominerals and their precursors.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biomineralization Characterization

| Item | Function/Application | Example in Use |

|---|---|---|

| Holey Carbon Grids | Support for vitrified ice in Cryo-TEM; commonly used mesh size is 200-300. | Quantifoil grids (e.g., 1.2/1.3 µm hole size) are glow-discharged before applying protein or mineral solution [31]. |

| Apoferritin Protein Standard | Benchmark sample for validating Cryo-TEM performance and data collection parameters. | Thermo Fisher Scientific's VitroEase Apoferritin Standard (3.5-4.0 mg/mL) is used for system calibration [31]. |

| Silicon Nitride (SiN) Membranes | Electron-transparent windows for liquid cell TEM, enabling in situ imaging. | SiN membranes (20-50 nm thick) enclose the liquid sample hermetically, separating it from the microscope vacuum [27] [28]. |

| Dimethyl Carbonate (DMC) | In situ source of CO₃²⁻ ions for calcium carbonate precipitation studies. | Hydrolysis of DMC in a CaCl₂ solution (with NaOH) allows controlled study of CaCO₃ nucleation and growth [16]. |

| Magic-Angle Spinning (MAS) Rotor | Holds solid samples for NMR analysis and spins them at a specific angle to narrow spectral lines. | Used in solid-state NMR of bone or synthetic biominerals to improve spectral resolution [29] [30]. |

Integrated Analysis: Resolving the Biomineralization Pathway Debate

The debate between LLPS and classical nucleation is not a matter of which single pathway is "correct," but rather under which conditions each mechanism dominates. The complementary data from Cryo-TEM, Liquid-Phase TEM, and NMR spectroscopy have been instrumental in building a nuanced, multi-scale understanding.

For the calcium carbonate system—the most studied model—evidence for LLPS is now considered to have "very high" confidence [16]. Cryo-TEM provides still images of emulsion-like structures and morphologies suggestive of coalescing liquid droplets [16]. Liquid-Phase TEM moves beyond these snapshots, offering direct video evidence of droplet diffusion, coalescence, and eventual crystallization [16] [27]. Meanwhile, ultra-high field ⁴³Ca NMR provides atomic-level validation by resolving distinct calcium environments in pre-nucleation clusters and amorphous precursors, the structural signature of a dense liquid phase that differs from both the solution and the final crystal [30].