Beyond Charge-Balancing: Benchmarking Modern Synthesizability Models for Accelerated Drug Discovery

The ability to accurately predict whether a theoretical material or compound can be successfully synthesized is a critical bottleneck in drug discovery and materials science.

Beyond Charge-Balancing: Benchmarking Modern Synthesizability Models for Accelerated Drug Discovery

Abstract

The ability to accurately predict whether a theoretical material or compound can be successfully synthesized is a critical bottleneck in drug discovery and materials science. For decades, the charge-balancing heuristic has served as a simple, rule-based proxy for synthesizability. This article provides a comprehensive benchmark of traditional charge-balancing against a new generation of machine learning-based synthesizability models. We explore the foundational limitations of classical heuristics, detail the methodologies of cutting-edge models like SynthNN and CSLLM, and address key troubleshooting challenges such as data scarcity and model generalization. Through a direct comparative analysis, we demonstrate that modern AI-driven models achieve significantly higher precision and recall, offering researchers a more reliable filter for prioritizing compounds. This paradigm shift promises to de-risk the discovery pipeline and accelerate the development of novel therapeutics.

The Synthesizability Challenge: Why Charge-Balancing is No Longer Enough

Defining Synthesizability in Drug Discovery and Materials Science

In both drug discovery and materials science, a significant gap exists between computational design and practical realization. While advanced generative models can propose molecules and materials with exceptional target properties, these candidates often prove difficult or impossible to synthesize in laboratory settings. This fundamental challenge—the trade-off between optimal properties and practical synthesizability—represents a critical bottleneck in accelerating discovery cycles across both fields [1] [2].

The concept of "synthesizability" has traditionally been assessed through different lenses in these domains. In drug discovery, fragment-based heuristic scores like the Synthetic Accessibility (SA) score have dominated, while materials science has relied heavily on thermodynamic stability metrics derived from density functional theory (DFT) calculations [3] [4]. However, these conventional approaches exhibit significant limitations. The SA score evaluates synthesizability primarily through structural features without guaranteeing that actual synthetic routes can be identified, while DFT-based methods often favor low-energy structures that may not be experimentally accessible due to kinetic barriers or synthesis pathway constraints [2] [3].

Recent advances in machine learning, retrosynthetic analysis, and large-scale data mining are transforming how synthesizability is defined and evaluated. This comparison guide examines emerging computational frameworks that directly address the synthesizability challenge through data-driven metrics and practical experimental validation, with particular attention to their benchmarking methodologies and relationship to charge-balancing principles in materials science.

Comparative Analysis of Synthesizability Frameworks

Key Metrics and Performance Indicators

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Synthesizability Frameworks

| Framework | Domain | Primary Metric | Reported Accuracy/Performance | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDDBench [1] [4] | Drug Discovery | Round-Trip Score | Comprehensive evaluation across generative models | Synergistic retrosynthesis-reaction prediction duality |

| CSLLM [3] | Materials Science | Synthesizability Classification Accuracy | 98.6% accuracy on test structures | Specialized LLMs for crystal synthesis assessment |

| Synthesizability-Guided Pipeline [2] | Materials Science | Experimental Success Rate | 7/16 targets successfully synthesized | Combined compositional and structural synthesizability score |

| In-House Synthesizability [5] | Drug Discovery | CASP Success with Limited Building Blocks | ~60% solvability with 6,000 vs. 70% with 17.4M building blocks | Building block-aware synthesizability scoring |

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Outcomes

Table 2: Experimental Protocols and Validation Outcomes

| Framework | Dataset Composition | Experimental Validation | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDDBench [4] | Generated molecules from SBDD models | Round-trip similarity via reaction prediction | Dependent on quality of reaction training data |

| CSLLM [3] | 70,120 ICSD structures + 80,000 non-synthesizable structures | 97.9% accuracy on complex structures with large unit cells | Requires text representation of crystal structures |

| Synthesizability-Guided Pipeline [2] | 4.4M computational structures from Materials Project, GNoME, Alexandria | 7 novel materials successfully synthesized in 3 days | Limited to oxide materials in experimental validation |

| In-House Synthesizability [5] | Caspyrus centroids + 200,000 ChEMBL molecules | 3 de novo candidates synthesized and tested for MGLL inhibition | ~2 additional reaction steps needed with limited building blocks |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

SDDBench: Round-Trip Synthesizability Assessment

The SDDBench framework introduces a novel evaluation methodology for drug synthesizability that moves beyond traditional SA scores. Its experimental protocol consists of four critical phases:

Phase 1: Molecule Generation - Multiple structure-based drug design (SBDD) models generate candidate ligand molecules for specific protein binding sites, representing the conditional distribution P(𝒎∣𝒑) where 𝒎 denotes the ligand molecule and 𝒑 represents the target protein [4].

Phase 2: Retrosynthetic Planning - A data-driven retrosynthetic planner trained on extensive reaction datasets (e.g., USPTO) predicts feasible synthetic routes for each generated molecule. This identifies reactants 𝓜r = {𝒎r⁽ⁱ⁾}i=1m capable of producing the target molecule through single or multi-step reactions [4].

Phase 3: Reaction Prediction - A forward reaction prediction model simulates the chemical reactions starting from the predicted reactants, attempting to reproduce both the synthetic route and the final generated molecule. This serves as a computational proxy for wet lab experimentation [4].

Phase 4: Round-Trip Scoring - The framework computes the Tanimoto similarity between the reproduced molecule and the originally generated molecule. Higher similarity scores indicate more feasible synthetic routes and greater practical synthesizability [4].

SDDBench Experimental Workflow: The round-trip synthesizability assessment process

CSLLM: Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model Framework

The CSLLM framework employs three specialized large language models to address synthesizability through a comprehensive approach:

Data Curation and Representation - The model utilizes 70,120 synthesizable crystal structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) and 80,000 non-synthesizable structures identified through positive-unlabeled (PU) learning with CLscore thresholding. A novel "material string" representation efficiently encodes crystal structure information including space group, lattice parameters, and atomic coordinates in a concise text format suitable for LLM processing [3].

Synthesizability LLM - A fine-tuned LLM performs binary classification of crystal structures as synthesizable or non-synthesizable, achieving 98.6% accuracy on testing data. This significantly outperforms traditional thermodynamic (74.1%) and kinetic (82.2%) stability metrics [3].

Method and Precursor LLMs - Additional specialized models predict appropriate synthetic methods (solid-state vs. solution) with 91.0% accuracy and identify suitable precursors with 80.2% success rate, providing comprehensive synthesis guidance [3].

Experimental Validation - The framework demonstrated exceptional generalization capability, maintaining 97.9% accuracy when predicting synthesizability of complex structures with large unit cells that considerably exceeded the complexity of training data [3].

Materials Synthesizability-Guided Discovery Pipeline

This integrated approach combines computational prediction with experimental validation:

Synthesizability Modeling - The framework integrates compositional and structural signals through dual encoders. A compositional MTEncoder transformer (fc) processes stoichiometric information, while a graph neural network (fs) based on the JMP model analyzes crystal structure graphs. The model is trained on Materials Project data with labels derived from ICSD existence flags [2].

Rank-Average Ensemble - Predictions from both composition and structure models are aggregated using a Borda fusion method: RankAvg(i) = (1/2N)∑m∈{c,s}(1 + ∑j=1N𝟏[sm(j) < sm(i)]). This rank-based approach prioritizes candidates with consistently high synthesizability scores across both modalities [2].

Retrosynthetic Planning and Experimental Execution - The pipeline applies Retro-Rank-In for precursor suggestion and SyntMTE for calcination temperature prediction. In practice, the approach screened 4.4 million computational structures, identified ~500 highly synthesizable candidates, and successfully synthesized 7 of 16 target materials within three days using automated laboratory systems [2].

Materials Synthesizability-Guided Discovery Pipeline

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources for Synthesizability Research

| Resource/Reagent | Function/Role | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| AiZynthFinder [5] | Open-source CASP toolkit for retrosynthetic analysis | Transferring synthesis planning to limited building block environments |

| USPTO Dataset [4] | Comprehensive reaction database for training ML models | Benchmarking retrosynthetic planners and reaction predictors |

| Materials Project [2] [3] | Database of computed materials properties and crystal structures | Training and testing materials synthesizability models |

| Zinc Building Blocks [5] | 17.4 million commercially available compounds | General synthesizability assessment in drug discovery |

| In-House Building Blocks [5] | Limited collections (e.g., ~6,000 compounds) | Practical synthesizability in resource-constrained environments |

| ICSD [3] | Database of experimentally synthesized inorganic crystals | Positive samples for training synthesizability classifiers |

| MTEncoder Transformer [2] | Composition-based model for materials synthesizability | Generating compositional embeddings for synthesizability prediction |

| JMP Crystal Graph Neural Network [2] | Structure-aware model for crystal synthesizability | Generating structural embeddings for synthesizability prediction |

The evolving landscape of synthesizability assessment demonstrates a clear paradigm shift from theoretical stability metrics toward practical synthesizability evaluation grounded in experimental feasibility. In drug discovery, the emergence of round-trip scoring and building-block-aware synthesizability metrics represents significant advances toward bridging the design-make gap. Similarly, in materials science, integrated frameworks that combine compositional and structural synthesizability signals with precursor prediction demonstrate remarkable experimental success rates [2] [5] [4].

These approaches collectively highlight the importance of benchmarking synthesizability models against real-world experimental outcomes rather than computational proxies alone. The relationship to charge-balancing research emerges particularly in materials science, where synthesizability models must account for oxidation state constraints, precursor compatibility, and reaction thermodynamics—all of which involve fundamental charge-balancing considerations [2].

As the field progresses, the integration of synthesizability prediction directly into generative design processes—rather than as a post-hoc filter—promises to further accelerate the discovery of novel, functional molecules and materials that are not only theoretically optimal but also practically accessible. The benchmarks and frameworks examined here provide critical foundation for this ongoing development, establishing rigorous standards for evaluating synthesizability across discovery domains.

In the pursuit of novel materials, researchers have long relied on heuristic methods—experience-based techniques that provide practical, though not always perfect, solutions to complex problems where exhaustive search is impractical [6]. Among these, the principle of charge-balancing has served as a foundational heuristic for predicting the synthesizability of inorganic crystalline materials. This approach functions as a simplifying rule of thumb, assuming that chemically viable compounds are those where the total positive charge from cations balances the total negative charge from anions, resulting in a net neutral ionic charge for the elements in their common oxidation states [7].

This guide objectively compares the performance of this traditional charge-balancing heuristic against modern data-driven alternatives, specifically deep learning synthesizability models. Framing this comparison within the context of benchmarking synthesizability models reveals the evolution of these predictive tools from their chemically intuitive origins to their current computational incarnations.

Principles and Assumptions of the Charge-Balancing Heuristic

Core Theoretical Foundation

The charge-balancing heuristic is predicated on several key chemical principles and assumptions:

- Ionic Bonding Model: It primarily assumes that inorganic compounds are held together by ionic bonds, where electrons are transferred from electropositive elements (metals, cations) to electronegative elements (non-metals, anions).

- Octet Stability: The driving force for compound formation is the achievement of a stable electron configuration (often an octet) for the constituent ions, mirroring the electron configuration of noble gases.

- Fixed Oxidation States: The method assigns common, integer oxidation states to each element (e.g., Na⁺, Ca²⁺, O²⁻, Cl⁻) and requires that the sum of positive charges equals the sum of negative charges in a chemical formula.

- Stoichiometric Constraints: The heuristic directly informs the stoichiometric ratios between elements in a compound's empirical formula. For example, for Ca²⁺ and O²⁻, the only charge-balanced ratio is 1:1, giving CaO.

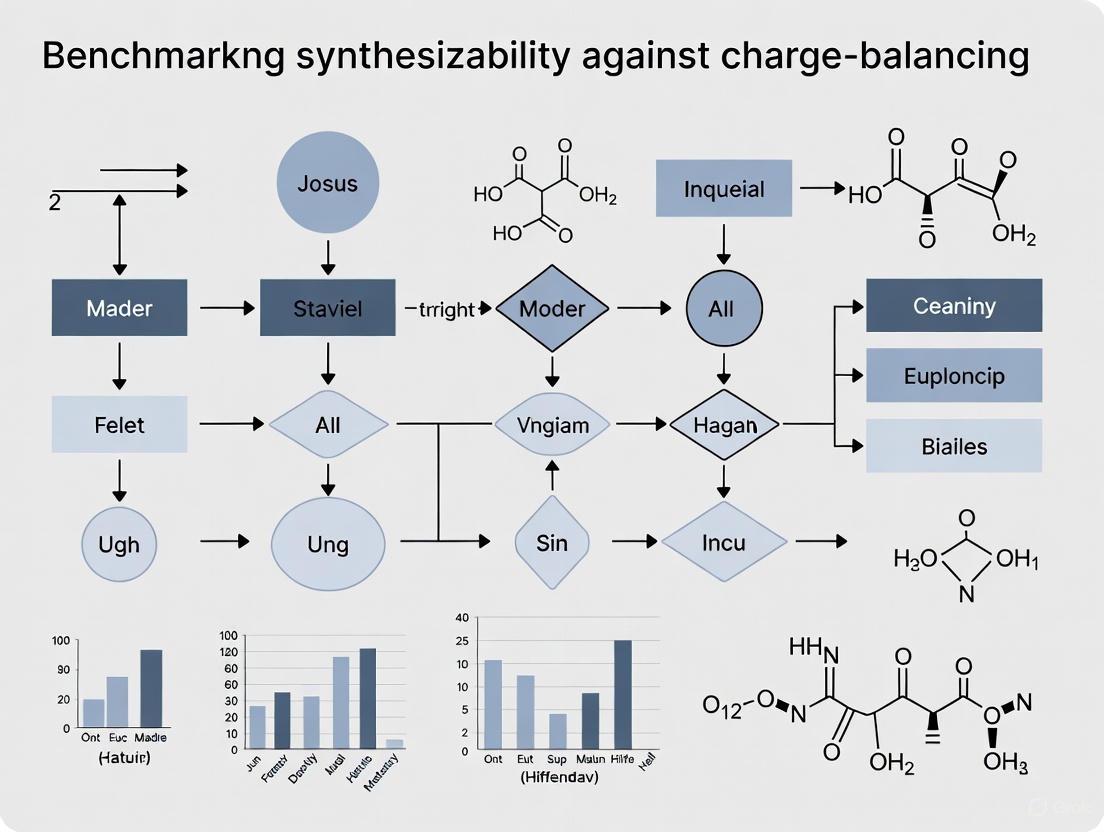

Methodological Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process of the charge-balancing heuristic when applied to a candidate chemical formula.

Benchmarking Against Modern Synthesizability Models

The performance of the charge-balancing heuristic can be quantitatively benchmarked against modern machine learning models, such as the deep learning synthesizability model (SynthNN) described in the search results [7].

Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes a direct performance comparison between charge-balancing and SynthNN, based on data from studies predicting the synthesizability of inorganic crystalline materials [7].

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Benchmark of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

| Metric | Charge-Balancing Heuristic | SynthNN (Deep Learning Model) |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Precision | Low (Precise values not given, but outperformed by SynthNN) [7] | 7x higher than charge-balancing [7] |

| Recall of Known Materials | 37% of known synthesized materials are charge-balanced [7] | Not Explicitly Stated |

| Performance in Ionic Systems | Only 23% of known binary cesium compounds are charge-balanced [7] | Not Explicitly Stated |

| Basis of Prediction | Fixed chemical rule (oxidation states) | Data-driven patterns learned from all known materials [7] |

| Key Limitation | Inflexible; fails for metallic/covalent materials, non-integer charges [7] | Requires large, curated training data [7] |

Experimental Protocol for Benchmarking

To ensure a fair and objective comparison, the benchmarking study followed a rigorous experimental protocol:

- Dataset Curation: The set of synthesizable, or "positive," examples was extracted from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), a comprehensive repository of experimentally synthesized and characterized inorganic crystals [7].

- Negative Example Generation: A set of artificially generated chemical formulas, not present in the ICSD, was created to represent unsynthesized (or "negative") examples. The study acknowledges the challenge of definitively labeling these as "unsynthesizable," leading to the use of Positive-Unlabeled (PU) learning algorithms [7].

- Model Training: The SynthNN model was trained using an atom2vec representation, which learns an optimal numerical representation for each chemical element directly from the distribution of synthesized materials in the dataset. This approach does not pre-suppose chemical rules like charge-balancing [7].

- Performance Evaluation: Model predictions were compared against the curated dataset. Precision, recall, and F1-scores were calculated, treating the artificially generated unsynthesized materials as negative examples for the purpose of benchmarking [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational and data resources essential for research in computational materials discovery and synthesizability prediction.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Synthesizability Prediction

| Research Reagent / Resource | Function and Utility |

|---|---|

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) | A critical database containing over 200,000 crystal structures of inorganic compounds. Serves as the primary source of "positive" data for training and benchmarking synthesizability models [7]. |

| atom2vec | A material representation framework that learns feature embeddings for chemical elements from data. It automates feature generation, eliminating the need for manual, heuristic-based descriptors [7]. |

| Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning Algorithms | A class of semi-supervised machine learning algorithms designed to learn from a set of confirmed positive examples and a set of unlabeled examples (which may contain both positive and negative instances). This is crucial for handling the lack of confirmed "unsynthesizable" materials data [7]. |

| Common Oxidation State Table | A reference list of typical ionic charges for elements (e.g., Alkali Metals: +1, Alkaline Earth Metals: +2, Halogens: -1, Oxygen: -2). This is the core "reagent" for applying the charge-balancing heuristic [7]. |

Integrated Workflow: From Heuristic to Machine Learning

The evolution from a heuristic-based approach to an integrated, data-driven workflow for material discovery is summarized below. This workflow shows how modern methods can incorporate, rather than wholly discard, traditional principles.

The traditional charge-balancing heuristic, while rooted in sound chemical principles of ionic bonding, demonstrates significant limitations as a standalone predictor for synthesizability, capturing only a minority of known materials. Benchmarking against modern deep learning models like SynthNN reveals a substantial performance gap, with data-driven models achieving dramatically higher precision by learning complex patterns from the entire landscape of synthesized materials.

This comparison underscores a broader paradigm shift in materials discovery: from reliance on single-principle heuristics to the adoption of holistic, data-informed models. These modern tools do not necessarily invalidate the principles of charge-balancing but subsume them into a more complex, learned representation of synthesizability. For researchers and drug development professionals, this indicates that integrating such computational synthesizability models into screening workflows is crucial for increasing the reliability and efficiency of identifying novel, synthetically accessible materials.

For decades, charge-balancing has served as a foundational, rule-based heuristic for predicting the synthesizability of inorganic crystalline materials in early-stage drug discovery and materials science. This method operates on the principle that a chemically viable compound should exhibit a net neutral ionic charge when common oxidation states are considered. However, within the context of modern computational drug design, a significant gap has emerged between theoretical predictions and practical laboratory success. A troubling trade-off persists: molecules predicted to have highly desirable pharmacological properties are often notoriously difficult to synthesize, while those that are easily synthesizable frequently exhibit less favorable properties [4].

This article objectively compares the performance of the traditional charge-balancing method against emerging data-driven synthesizability models. By benchmarking these approaches against experimental data and standardized metrics, we expose the significant failure rate of charge-balancing and provide researchers with a clear framework for selecting more reliable assessment tools.

Quantitative Performance Benchmarking

The limitations of charge-balancing are not merely theoretical but are quantitively demonstrable when assessed against comprehensive databases of known materials. The table below summarizes the performance of charge-balancing against a modern data-driven model, SynthNN, in predicting the synthesizability of inorganic chemical compositions.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Synthesizability Assessment Methods

| Metric | Charge-Balancing | SynthNN (Data-Driven Model) |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Precision | Severely Limited [7] | 7x higher than charge-balancing [7] |

| Known Material Recall | Only 37% of synthesized ICSD materials are charge-balanced [7] | Informed by the entire spectrum of synthesized materials [7] |

| Key Limitation | Inflexible rule; fails for metallic/covalent materials [7] | Learns complex, real-world factors influencing synthesis [7] |

| Basis of Prediction | Rigid application of common oxidation states [7] | Learned data representation from all synthesized materials [7] |

The failure of charge-balancing is particularly stark within specific chemical families. For example, among all known ionic binary cesium compounds, only 23% are actually charge-balanced according to common oxidation states [7]. This indicates that strict charge neutrality is not a prerequisite for synthetic accessibility, and over-reliance on this heuristic falsely excludes a vast landscape of potentially viable materials.

Experimental Protocols for Synthesizability Assessment

To move beyond simple heuristics, the field has developed more robust, experimental protocols for evaluating molecular synthesizability. These methodologies provide a framework for benchmarking the performance of any predictive model, including charge-balancing.

The Round-Trip Score Protocol for Molecular Synthesizability

A significant innovation is the round-trip score, a data-driven metric designed to evaluate whether a feasible synthetic route can be found for a given molecule [4] [1]. Its experimental workflow is as follows:

- Input: A target molecule generated by a drug design model.

- Retrosynthesis Prediction: A data-driven retrosynthetic planner is used to predict a feasible synthetic route, identifying a set of starting reactants for the target molecule [4].

- Forward Reaction Prediction: The predicted reactants are then fed into a forward reaction prediction model. This model acts as a simulation agent, attempting to reproduce the target molecule through a series of simulated chemical reactions [4].

- Output & Scoring: The molecule produced by the forward prediction is compared to the original target molecule. The round-trip score is computed as the Tanimoto similarity between the reproduced and original molecules. A high score indicates a feasible and reproducible synthetic route, while a low score exposes synthesizability issues [4].

The following diagram illustrates this cyclic validation process:

Benchmarking with SDDBench

The round-trip score forms the foundation of benchmarks like SDDBench, which is used to evaluate the ability of generative models to produce synthesizable drug candidates [4] [1]. Unlike the Synthetic Accessibility (SA) score—which relies on structural fragments and complexity penalties but cannot guarantee a synthetic route exists—the round-trip score directly assesses practical feasibility [4]. Benchmarking studies apply this protocol across a range of generative models, calculating aggregate success rates and round-trip scores to provide a standardized performance comparison [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Models

Implementing these advanced assessment methods requires a suite of computational and data resources. The following table details the essential components of a modern synthesizability evaluation workflow.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Models for Synthesizability Assessment

| Item Name | Type | Function / Description |

|---|---|---|

| Retrosynthetic Planner | Software Model | Predicts feasible synthetic routes and starting reactants for a target molecule [4]. |

| Forward Reaction Predictor | Software Model | Simulates the chemical reaction from reactants to products, validating proposed routes [4]. |

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) | Data Resource | A comprehensive database of synthesized crystalline inorganic materials used for training and benchmarking [7]. |

| USPTO Dataset | Data Resource | A large-scale dataset of chemical reactions used to train retrosynthesis and reaction prediction models [4]. |

| Atom2Vec | Framework | A deep learning framework that learns optimal chemical representations directly from data of synthesized materials [7]. |

| Round-Trip Score | Metric | A quantitative metric (Tanimoto similarity) that validates the feasibility of a synthetic route [4]. |

The evidence demonstrates that charge-balancing operates with a significant failure rate, correctly classifying only a minority of known synthesizable materials. Its rigid, rule-based framework is fundamentally mismatched to the complex and multi-faceted reality of chemical synthesis. While it offers computational simplicity, this comes at the cost of severely limited precision and recall.

In contrast, data-driven synthesizability models like SynthNN and evaluation protocols like the round-trip score in SDDBench offer a paradigm shift. By learning directly from the entire corpus of experimental synthesis data, these methods capture the subtle and complex factors that truly determine whether a molecule can be made. For researchers and drug development professionals, the path forward is clear: moving beyond the outdated heuristic of charge-balancing to adopt these more robust, data-informed tools is essential for accelerating the discovery of viable, synthesizable therapeutics.

This guide objectively compares the performance of various chemical synthesis methods, focusing on the pyrazoline derivative as a model compound, and provides supporting experimental data. The analysis is framed within a broader thesis on benchmarking synthesizability models, exploring how computational frameworks like the Minimum Thermodynamic Competition (MTC) principle can guide synthesis parameter selection to minimize kinetic by-products, a challenge directly relevant to charge-balancing research in materials design.

The journey from a theoretical compound to a synthesized material is governed by a complex interplay of thermodynamic, kinetic, and technological factors. Real-world synthesis must navigate constraints related to hardware, data storage, calibration processes, and costs, which significantly influence the performance of the resulting materials and algorithms [8]. For drug development professionals and researchers, assessing the feasibility of a proposed synthesis—encompassing the availability of starting materials, the efficiency of the pathway, and the potential for successful reactions without excessive side products—is a critical first step [9].

The ultimate goal is often to achieve high phase-purity—the selective formation of a target material without undesired kinetic by-products. Traditional thermodynamic phase diagrams identify stability regions but do not explicitly quantify the kinetic competitiveness of by-product phases [10]. This gap is addressed by emerging synthesizability models, which use computational approaches to predict optimal synthesis conditions, thereby bridging the design-synthesis divide.

Comparing Synthesis Method Performance

A performance comparison of various synthesis methods for preparing pyrazoline derivatives reveals significant differences in efficiency, yield, and operational conditions [11]. The following table summarizes key quantitative data extracted from experimental reports.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Pyrazoline Synthesis Methods

| Methods Parameter | Conventional | Microwave | Ultrasonic | Grinding | Ionic Liquid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Reflux 110°C [11] | 20-150°C [11] | 25-50°C [11] | Room Temperature (RT) [11] | ~100°C [11] |

| Reaction Time | 3-7 hours [11] | 1-4 minutes [11] | 10-20 minutes [11] | 8-12 minutes [11] | 2-6 hours [11] |

| Energy Source | Electricity and heat [11] | Electromagnetic waves [11] | Sound waves [11] | Human energy/tools [11] | Heat/electricity [11] |

| Typical Product Yield | 55-75% [11] | 79-89% [11] | 72-89% [11] | 78-94% [11] | 87-96% [11] |

Performance Analysis and Key Findings

- Efficiency vs. Yield: Conventional methods serve as a baseline but exhibit longer reaction times and moderate yields, with higher temperatures sometimes leading to product decomposition [11]. In contrast, microwave-assisted synthesis dramatically reduces reaction time from hours to minutes while achieving high yields, offering a cleaner and more efficient alternative [11].

- Green Chemistry Approaches: Grinding techniques (mechanochemistry) and ultrasonic irradiation are notable solvent-free or minimal-solvent methods. Grinding operates at room temperature and achieves high yields, making it cost-effective and environmentally friendly [11]. Ultrasonic synthesis uses sound waves to create cavitation effects, enabling reactions in short timeframes with good yields [11].

- High-Yield Strategy: Ionic liquid methods consistently achieve the highest reported yields (87-96%). These solvents also function as catalysts and can be recycled without significant loss of activity, presenting a robust, high-performance pathway despite longer reaction times [11].

Experimental Protocols for Synthesis and Validation

Protocol: Conventional Two-Step Synthesis of Pyrazoline Derivatives

This established protocol illustrates common challenges, such as longer reaction times and moderate yields [11].

Step 1: Claisen-Schmidt Condensation (Chalcone Formation)

- Objective: Synthesis of the chalcone intermediate (enone) via aldol condensation.

- Procedure: Conduct Claisen-Schmidt condensation between acetophenone and aromatic aldehyde analogs using a base catalyst to produce α,β-unsaturated ketones (chalcones) [11].

- Key Parameters: Reaction is typically carried out under reflux conditions.

Step 2: Cyclization to Pyrazoline

- Objective: Convert the chalcone into the target pyrazoline derivative.

- Procedure: React the synthesized chalcone with aryl hydrazine (often as a hydrochloride salt to reduce side products) under reflux conditions [11].

- Key Parameters: Aryl hydrazine is used to improve cyclization reaction results; reaction requires reflux for several hours [11].

Protocol: Validating the Minimum Thermodynamic Competition (MTC) Hypothesis

This computational and experimental protocol aims to minimize kinetic by-products in aqueous synthesis, directly relevant to benchmarking synthesizability models [10].

Computational MTC Analysis

- Objective: Identify synthesis conditions that maximize the free energy difference between the target phase and its most competitive by-product phase.

- Procedure:

- Calculate the Pourbaix potential (�¯) for the target and all competing phases using standard Gibbs formation free energies and accounting for pH, redox potential (E), and metal ion concentrations [10].

- Compute the thermodynamic competition metric, ΔΦ(�), for the target phase k:

ΔΦ(Y) = Φₖ(Y) - min{Φᵢ(Y)} for i in competing phases[10]. - Employ a gradient-based computational algorithm to find the optimal conditions (Y*) that minimize ΔΦ(Y), thus minimizing thermodynamic competition [10].

Experimental Validation

- Objective: Synthesize the target material (e.g., LiIn(IO₃)₄ or LiFePO₄) across a wide range of aqueous electrochemical conditions.

- Procedure:

- Perform systematic synthesis experiments across conditions spanning the thermodynamic stability region of the target phase.

- Characterize the products to determine phase purity.

- Correlation: Experimental phase purity is correlated with the computed ΔΦ(Y) value. Phase-pure synthesis is expected predominantly where ΔΦ(Y) is minimized, even if conditions are within the thermodynamic stability region [10].

Visualizing Synthesis Workflows and Principles

Minimum Thermodynamic Competition Principle

Synthesis Optimization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents, materials, and computational tools essential for advanced synthesis research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Synthesis Optimization

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Ionic Liquids (e.g., EMIM hydrogen sulfate) | Serves as both solvent and catalyst in green synthesis; enables high yields and can be recycled, maintaining catalytic activity [11]. |

| Aryl Hydrazine Hydrochloride Salts | Reacts with chalcones for pyrazoline cyclization; hydrochloride form helps reduce side reactions and improves yield [11]. |

| Synthesizability Assessment (SA) Score | AI-driven tool for high-throughput screening of molecular libraries; assesses synthetic feasibility based on reaction logic, building block availability, and cost [12]. |

| MTC Computational Framework | Identifies optimal aqueous synthesis conditions (pH, E, concentration) to maximize driving force for the target phase and minimize kinetic by-products [10]. |

| Transfer Learning Models (e.g., XGBoost) | Predicts synthesis outcomes (like particle size in MOFs) by leveraging heterogeneous data sources, accelerating synthesis optimization [13]. |

| Bottom-Up ODE Models | Computational models of biological pathways using ordinary differential equations; used to design and predict the behavior of synthetic biological circuits [14]. |

The performance comparison clearly demonstrates that non-conventional synthesis methods—microwave, ultrasonic, grinding, and ionic liquids—consistently outperform conventional reflux in key metrics such as reaction time, product yield, and often environmental impact [11]. The criticality of precise parameter control underpins all synthesis methods. A promising paradigm for future synthesis, particularly in drug development and advanced materials, is the tight integration of predictive computational models like the MTC framework [10] and SA Score [12] with experimental validation. This approach provides a powerful strategy for navigating the complex thermodynamic and kinetic landscape of real-world synthesis.

The efficient discovery of new functional materials and viable drug candidates is fundamentally limited by a single, critical question: can a proposed molecule or crystal structure actually be synthesized? For years, the scientific community has relied on chemically intuitive but performance-limited proxies for synthesizability, such as the charge-balancing principle for inorganic materials. This paradigm, which filters candidate materials based on net neutral ionic charge using common oxidation states, has proven inadequate. Research demonstrates that only 37% of synthesized inorganic materials in the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) are actually charge-balanced, a figure that drops to a mere 23% for binary cesium compounds [7]. This reveals that while chemically motivated, charge-balancing is an inflexible constraint that fails to account for diverse bonding environments like metallic alloys or covalent networks [7].

The limitations of such rule-based approaches have created an urgent need for a new, data-driven paradigm. This guide objectively compares the established charge-balancing method against modern machine learning (ML) and large language model (LLM) alternatives, providing researchers with the experimental data and protocols needed to evaluate these tools for their own discovery pipelines.

Quantitative Performance Comparison of Synthesizability Methods

The transition to a data-driven paradigm is justified by a significant performance gap. The table below provides a quantitative comparison of various synthesizability prediction methods, highlighting their accuracy, scope, and requirements.

Table 1: Comprehensive Performance Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

| Method Name | Type/Model | Reported Accuracy/Performance | Key Advantages | Input Requirement | Primary Domain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charge-Balancing [7] | Rule-based Filter | 37% Precision on ICSD materials [7] | Chemically intuitive, computationally inexpensive | Chemical Composition | Inorganic Crystals |

| CSLLM [3] | Fine-tuned Large Language Model | 98.6% accuracy; >90% accuracy for methods & precursors [3] | Predicts synthesizability, synthetic methods, and precursors | Text-represented Crystal Structure | 3D Crystal Structures |

| SynthNN [7] | Deep Learning (atom2vec) | 7x higher precision than formation energy; 1.5x higher precision than human experts [7] | Requires only chemical composition, no structural data needed | Chemical Composition | Inorganic Crystals |

| SC Model [15] | Deep Learning (FTCP representation) | 82.6% Precision, 80.6% Recall (Ternary Crystals) [15] | High true positive rate (88.6%) on new materials post-2019 [15] | Crystal Structure | Inorganic Crystals (Ternary) |

| CLscore Model [3] | Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning | Used for data curation; CLscore <0.1 indicates non-synthesizable [3] | Enables identification of negative examples for model training | Crystal Structure | 3D Crystals |

The data reveals that ML/LM models do not merely offer incremental improvement but a transformational leap in predictive capability. The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models (CSLLM) framework, for instance, achieves an accuracy of 98.6%, significantly outperforming not only charge-balancing but also traditional stability-based screening methods like energy above hull (74.1% accuracy) and phonon stability (82.2% accuracy) [3]. Furthermore, the SynthNN model demonstrates the practical impact of this new paradigm, outperforming all of 20 expert material scientists in a head-to-head discovery task by achieving 1.5x higher precision and completing the task five orders of magnitude faster than the best human expert [7].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear understanding of how these models operate, this section details the core experimental protocols for the leading data-driven approaches.

Protocol A: The CSLLM Framework for Crystal Structures

The CSLLM framework utilizes three specialized LLMs to predict synthesizability, suggest synthetic methods, and identify suitable precursors [3].

Dataset Curation:

- Positive Samples: 70,120 synthesizable crystal structures were meticulously selected from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), excluding disordered structures [3].

- Negative Samples: 80,000 non-synthesizable structures were identified by applying a pre-trained PU learning model to a pool of 1.4 million theoretical structures and selecting those with a CLscore below 0.1 [3].

Text Representation - Material String:

- Crystal structures are converted into a simplified text format called a "material string" for efficient LLM processing. This representation condenses essential information by leveraging symmetry, avoiding the redundancy of CIF or POSCAR files. The format is:

Space Group | a, b, c, α, β, γ | (AtomSite1-WyckoffSite1[WyckoffPosition1 x1, y1, z1]; AtomSite2-...)[3].

- Crystal structures are converted into a simplified text format called a "material string" for efficient LLM processing. This representation condenses essential information by leveraging symmetry, avoiding the redundancy of CIF or POSCAR files. The format is:

Model Fine-Tuning:

- Three separate LLMs are fine-tuned on this comprehensive dataset using the material string representation. This domain-specific tuning aligns the models' broad linguistic knowledge with crystallographic features critical for predicting synthesizability [3].

Protocol B: The SynthNN Model for Chemical Compositions

SynthNN predicts synthesizability from chemical formulas alone, making it ideal for early-stage discovery where structural data is unavailable [7].

Data Sourcing and Positive-Unlabeled Learning:

- Positive Data: Chemical formulas of synthesizable materials are extracted from the ICSD [7].

- Artificial Negative Data: A key challenge is the lack of verified non-synthesizable materials. This is addressed by generating a large set of artificial, non-existent chemical formulas, which are treated as unlabeled data. A semi-supervised Positive-Unlabeled (PU) learning algorithm is then employed, which probabilistically reweights these unlabeled examples according to their likelihood of being synthesizable [7].

Feature Representation - atom2vec:

- The model uses a learned embedding layer called

atom2vecthat represents each chemical element. This embedding is optimized alongside other network parameters during training, allowing the model to discover the optimal set of descriptors for synthesizability directly from the data, without relying on pre-defined human concepts like charge balance [7].

- The model uses a learned embedding layer called

Model Architecture and Training:

- SynthNN employs a deep learning classification model. The input chemical formula is processed through the atom2vec embedding layer, and the resulting representation is passed through the network to output a binary synthesizability classification [7].

Benchmarking Protocol: Charge-Balancing vs. Data-Driven Models

A rigorous comparison requires a standardized evaluation framework.

- Test Set Construction: Create a benchmark dataset containing known synthesizable materials (e.g., from ICSD) and known non-synthesizable materials (e.g., via PU learning models or failed experimental data) [3] [7].

- Metric Selection: Standard performance metrics including Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score should be calculated. For PU learning scenarios, the F1-score is particularly informative [7].

- Model Inference: Run the charge-balancing algorithm and the trained ML/LM models (e.g., CSLLM, SynthNN) on the benchmark set.

- Performance Analysis: Compare the metrics across all methods. The analysis should also extend to specific capabilities, such as the model's ability to recommend synthetic routes or precursors, a feature unique to advanced frameworks like CSLLM [3].

Workflow Visualization of the New Paradigm

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of a modern, synthesizability-driven discovery pipeline, highlighting the role of machine learning at its foundation.

To implement this new paradigm, researchers require access to specific data, computational tools, and benchmarking standards. The table below details key resources.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Synthesizability Prediction

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Key Features / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [3] [15] [7] | Materials Database | The primary source of positive (synthesizable) examples for training and benchmarking models. | Contains experimentally validated crystal structures. Essential for creating ground-truth datasets. |

| Materials Project (MP) [3] [15] [16] | Computational Materials Database | Provides a large repository of theoretically predicted structures, often used to source candidate or negative samples. | Contains DFT-calculated properties. Often used with PU learning to identify non-synthesizable candidates. |

| Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning [3] [7] | Machine Learning Technique | Addresses the core challenge of lacking verified negative data by treating unsynthesized materials as unlabeled. | A critical methodological component for building robust classifiers in this domain. |

| Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Network (CGCNN) [15] | Deep Learning Model | A widely used model architecture that processes crystal structures represented as graphs for property prediction. | Enables direct learning from atomic connections and periodic structure. |

| Fourier-Transformed Crystal Properties (FTCP) [15] | Crystal Structure Representation | Represents crystal features in both real and reciprocal space, capturing periodicity and elemental properties. | An alternative to graph-based representations that can improve model performance. |

| AstaBench [17] | AI Benchmarking Suite | Provides a holistic benchmark for evaluating AI agents on scientific tasks, including potential synthesizability-related challenges. | Helps standardize evaluation and compare AI performance in scientific discovery contexts. |

The evidence from comparative experimental data is clear: the paradigm for predicting synthesizability has irrevocably shifted. The traditional charge-balancing approach, while foundational, is now obsolete as a reliable standalone filter, with a demonstrated precision of only 37% [7]. The new paradigm is defined by data-driven machine learning and language models like CSLLM and SynthNN, which offer not just incremental gains but a fundamental leap in accuracy, speed, and functionality. These tools can outperform human experts, predict synthesis pathways, and integrate seamlessly into high-throughput computational screening workflows. For researchers and drug development professionals, adopting this new paradigm is no longer a forward-looking aspiration but a present-day necessity for accelerating the discovery of viable materials and therapeutic candidates.

A New Generation of Models: From Machine Learning to Large Language Models

The discovery of new inorganic crystalline materials is a cornerstone of technological advancement, powering innovations across fields from renewable energy to pharmaceuticals. A significant bottleneck in this process, however, lies in identifying which computationally predicted materials are synthetically accessible in a laboratory. For years, charge-balancing principles—which filter materials based on net ionic charge neutrality—served as a primary computational filter for synthesizability [7]. While chemically intuitive, this approach possesses fundamental limitations; remarkably, only 37% of all synthesized inorganic compounds in the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) satisfy common charge-balancing rules, with the figure dropping to just 23% for binary cesium compounds [7]. This gap highlights the need for more sophisticated, data-driven approaches that can learn the complex, multi-faceted nature of synthetic feasibility directly from experimental data.

Enter composition-based deep learning models. These models predict synthesizability using only chemical formulas, bypassing the need for rarely known atomic structures of undiscovered materials. Among these, the deep learning synthesizability model (SynthNN) represents a significant step forward. By leveraging the entire space of known inorganic compositions, SynthNN reformulates materials discovery as a classification task, demonstrating that machines can not only match but surpass human expertise in identifying promising candidates [7]. This guide provides a comprehensive overview of SynthNN, objectively comparing its performance against traditional charge-balancing methods and modern alternatives, with a specific focus on experimental data and benchmarking protocols essential for research scientists and drug development professionals.

Performance Benchmarking: SynthNN vs. Alternative Approaches

The evaluation of synthesizability models requires careful consideration of multiple performance metrics. The table below summarizes a quantitative comparison between SynthNN, traditional charge-balancing, a modern Large Language Model (LLM)-based approach (CSLLM), and a combined composition-structure model, providing a clear overview of the current landscape.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

| Model / Method | Input Type | Key Performance Metric | Performance vs. Charge-Balancing | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SynthNN [7] | Composition | 7x higher precision than DFT formation energy; 1.5x higher precision than best human expert | Higher Precision | Computationally efficient; requires no crystal structure |

| Charge-Balancing [7] | Composition | Only 37% of known synthesized materials are charge-balanced | Baseline | Simple, chemically intuitive rule |

| CSLLM (Synthesizability LLM) [3] | Crystal Structure | 98.6% accuracy on testing data | Significantly higher accuracy | State-of-the-art accuracy; can also predict methods and precursors |

| Combined Composition-Structure Model [2] | Composition & Structure | Successfully guided the experimental synthesis of 7 out of 16 target structures | More reliable for experimental synthesis | Integrates complementary signals from composition and structure |

Analysis of Comparative Performance

Precision and Recall Trade-offs for SynthNN: The performance of SynthNN is highly dependent on the chosen decision threshold. Evaluated on a dataset with a 20:1 ratio of unsynthesized-to-synthesized examples—reflecting the reality that most random chemical combinations are not synthesizable—SynthNN's operational parameters can be tuned for specific discovery goals [18]. For instance, using a threshold of 0.10 yields high recall (0.859) but lower precision (0.239), ideal for initial broad screening where missing a potential candidate is costly. Conversely, a threshold of 0.90 offers high precision (0.851) but lower recall (0.294), suitable for prioritizing a shortlist of the most promising candidates for experimental validation [18].

Head-to-Head with Human Experts: In a controlled discovery comparison against 20 expert materials scientists, SynthNN outperformed all human participants, achieving 1.5x higher precision in identifying synthesizable compositions. Furthermore, it completed the task five orders of magnitude faster, highlighting its dual advantage in both accuracy and efficiency for screening vast chemical spaces [7].

The Rise of LLM-Based Approaches: Newer models fine-tuned from Large Language Models have demonstrated exceptional capability, particularly when crystal structure information is available. The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM) framework achieved a state-of-the-art 98.6% accuracy on a balanced test set, significantly outperforming traditional thermodynamic and kinetic stability metrics [3]. This showcases the potential of leveraging foundational AI models for complex chemical prediction tasks.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Core SynthNN Training and Validation Protocol

The development of SynthNN followed a rigorous machine learning workflow, central to which was the construction of a robust dataset and a specialized learning algorithm to handle its inherent biases [7].

Data Curation: The positive dataset consisted of synthesizable inorganic materials extracted from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), representing a comprehensive history of reported and characterized crystalline inorganic materials [7] [18]. A critical challenge is the lack of a definitive database of "unsynthesizable" materials. This was addressed by generating a large set of artificial chemical formulas as negative examples, acknowledging that some could be synthesizable but are simply absent from the ICSD [7].

Model Architecture: SynthNN utilizes the atom2vec representation, which learns an optimal numerical representation for each element directly from the distribution of synthesized materials. This learned representation, encapsulated in an atom embedding matrix, is optimized alongside all other parameters of the deep neural network. This approach requires no prior chemical knowledge or assumptions about synthesizability rules, allowing the model to discover the relevant chemical principles from data [7].

Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning: To account for the incomplete labeling in the negative dataset, SynthNN employs a semi-supervised PU learning algorithm. This framework treats the artificially generated materials as "unlabeled" rather than definitively "negative," and probabilistically reweights them during training according to their likelihood of being synthesizable. This methodology is crucial for managing the uncertainty inherent in the data [7].

Benchmarking Against Charge-Balancing

The experimental protocol for benchmarking against charge-balancing involved a direct comparison on the task of identifying synthesizable materials [7].

- Test Set: A set of known synthesized materials (from ICSD) and artificially generated compositions was established.

- Charge-Balancing Prediction: Each composition was evaluated for charge balance according to common oxidation states. A material was predicted to be synthesizable if it was charge-balanced.

- SynthNN Prediction: The same compositions were fed into the trained SynthNN model to obtain synthesizability scores.

- Performance Calculation: Standard metrics (e.g., precision, recall) were calculated for both methods, treating synthesized materials as positive examples and artificially generated ones as negative examples. This demonstrated SynthNN's superior precision [7].

Protocol for Structure-Aware and LLM-Based Models

For models that incorporate crystal structure, the experimental protocol differs.

- Data for LLM Models: The Crystal Synthesis LLM (CSLLM) was trained on a balanced dataset of 70,120 synthesizable crystal structures from the ICSD and 80,000 non-synthesizable structures. The non-synthesizable structures were identified from over 1.4 million theoretical structures in other databases (like the Materials Project) using a pre-trained PU learning model (CLscore < 0.1) to ensure high confidence [3].

- Text Representation: To use LLMs, crystal structures (typically in CIF format) are converted into a human-readable text description using tools like

Robocrystallographeror a custom "material string" that concisely captures lattice parameters, space group, and atomic coordinates [3] [19]. - Fine-Tuning: A base LLM (e.g., GPT-4o-mini, LLaMA) is then fine-tuned on these text descriptions for the binary classification task of "synthesizable" or "non-synthesizable" [3] [19].

Diagram 1: Synthesizability assessment workflow for inorganic crystalline materials, showing multiple pathways based on input data and methodology.

Successful synthesizability prediction and validation rely on access to curated data and specialized computational tools. The following table details key resources used in the development and benchmarking of models like SynthNN.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Relevance to Synthesizability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [7] [3] | Materials Database | Provides a comprehensive collection of experimentally synthesized and characterized inorganic crystal structures. | Serves as the primary source of "positive" data (known synthesizable materials) for training and testing models. |

| Materials Project (MP) [2] [19] | Computational Materials Database | A repository of computed properties and crystal structures for both known and predicted materials. | Source of "unlabeled" or hypothetical structures used as negative examples or for discovery screening. |

| Atom2Vec [7] | Computational Representation | A deep learning-based method for generating numerical representations of chemical elements from data. | Forms the foundational input representation for SynthNN, enabling it to learn chemical principles without explicit rules. |

| Robocrystallographer [19] | Software Tool | Generates text-based descriptions of crystal structures from CIF files. | Converts structural data into a format usable by Large Language Models (LLMs) for structure-based prediction. |

| CLscore [3] | PU Learning Metric | A score generated by a pre-trained model to estimate the likelihood that a theoretical structure is non-synthesizable. | Used to programmatically create high-confidence "negative" datasets from large pools of hypothetical structures for training robust models. |

The benchmarking of SynthNN against the long-established charge-balancing principle marks a paradigm shift in the computational prediction of material synthesizability. The experimental data clearly shows that data-driven, composition-based deep learning models offer a substantial improvement in precision and efficiency, even surpassing human expert performance in targeted discovery tasks [7]. While charge-balancing remains a simple, interpretable heuristic, its poor performance on known synthesized materials limits its utility as a reliable filter in modern materials discovery pipelines.

The field continues to evolve rapidly. New architectures that integrate crystal structure information, such as graph neural networks and fine-tuned Large Language Models, are pushing the boundaries of accuracy [3] [19]. Furthermore, models that combine both compositional and structural signals show great promise in guiding successful experimental synthesis, as demonstrated by the realization of several novel compounds [2]. For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice of model depends on the specific discovery context—composition-only models like SynthNN are indispensable for initial, vast compositional space screening where structure is unknown, while structure-aware models provide a critical final validation for the most promising candidates, ultimately accelerating the journey from in-silico prediction to realized material.

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have revolutionized property prediction in materials science by directly learning from atomic structures. Unlike traditional descriptor-based methods, structure-aware GNNs represent crystal structures as graphs, where atoms serve as nodes and chemical bonds as edges. This approach enables models to capture complex relational and spatial information critical for predicting material properties [20]. Among these, ALIGNN (Atomistic Line Graph Neural Network) and SchNet represent two influential but architecturally distinct paradigms. ALIGNN explicitly incorporates angular information by constructing an atomistic line graph, while SchNet utilizes continuous-filter convolutions focusing on interatomic distances [21]. These models are particularly valuable for benchmarking synthesizability against charge-balancing research, as they can predict key properties like formation energy and stability that directly relate to a material's synthesizability and electronic structure.

Architectural Comparison and Computational Workflows

Fundamental Architectural Differences

The core difference between ALIGNN and SchNet lies in how they model atomic interactions. ALIGNN introduces a specialized graph convolution layer that explicitly models both two-body (pair) and three-body (angular) interactions. This is achieved by composing two edge-gated graph convolution layers—the first applied to the atomistic line graph L(g) representing triplet interactions, and the second applied to the atomistic bond graph g representing pair interactions [22]. In ALIGNN's line graph, nodes correspond to interatomic bonds and edges correspond to bond angles, allowing angular information to be directly incorporated during message passing [23].

In contrast, SchNet employs continuous-filter convolutional layers that operate directly on interatomic distances, naturally handling periodic boundary conditions while providing translation and permutation invariance [21]. SchNet focuses primarily on modeling the local chemical environment through radial filters, effectively capturing distance-based interactions but without explicitly representing angular information like ALIGNN does.

Computational Workflow and Complexity

The architectural differences lead to significant variations in computational complexity and workflow. For a central atom with k neighbors, ALIGNN's explicit enumeration of all pairwise bond angles results in O(k²) computational complexity for local angle calculations [21]. This quadratic scaling can impact computational efficiency, particularly for systems with dense local atomic environments.

SchNet's distance-based approach generally maintains O(k) complexity but may sacrifice angular resolution. Recent alternatives like SFTGNN (Spherical Fourier Transform-Enhanced GNN) attempt to bridge this gap by projecting atomic local environments into the spherical harmonic domain, capturing angular dependencies without explicit angle enumeration, thus reducing complexity to O(k) while preserving three-dimensional geometric information [21].

The workflow for structure-aware GNNs typically involves: (1) crystal graph construction from atom positions and lattice parameters, (2) neighborhood identification within a cutoff radius, (3) message passing through multiple graph convolution layers, and (4) global pooling and readout for property prediction [21].

Architecture comparison highlighting key differences in how ALIGNN and SchNet process structural information [22] [21].

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Data

Accuracy and Generalization Performance

Comprehensive benchmarking reveals distinct performance profiles across various material properties. ALIGNN demonstrates particular strength in predicting properties sensitive to angular information, achieving state-of-the-art results on multiple JARVIS-DFT and Materials Project datasets [22]. The explicit modeling of bond angles enables more accurate predictions for electronic properties like band gaps and mechanical properties like elastic moduli.

Recent large-scale benchmarking under the MatUQ framework, which evaluates models on out-of-distribution (OOD) generalization with uncertainty quantification, provides insights into real-world performance. This evaluation, encompassing 1,375 OOD prediction tasks across six materials datasets, shows that no single GNN architecture universally dominates all tasks [20]. Earlier models including SchNet and ALIGNN remain competitive, while newer models like CrystalFramer and SODNet demonstrate superior performance on specific material properties [20].

For catalytic surface reactions, the recently developed AlphaNet achieves a mean absolute error (MAE) of 42.5 meV/Å for forces and 0.23 meV/atom for energy on formate decomposition datasets, outperforming NequIP's 47.3 meV/Å and 0.50 meV/atom respectively [24]. On defected graphene systems, AlphaNet attains a force MAE of 19.4 meV/Å and energy MAE of 1.2 meV/atom, significantly surpassing NequIP's 60.2 meV/Å and 1.9 meV/atom [24].

Table 1: Performance Comparison Across Material Properties

| Model | Band Gap MAE (eV) | Formation Energy MAE (eV/atom) | Force MAE (meV/Å) | Elastic Property MAE (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALIGNN | 0.1985 (JARVIS-DFT) [25] | 0.11488 (JARVIS-DFT) [25] | 42.5 (Formate) [24] | 12.76 (Shear Modulus) [25] |

| SchNet | ~0.35 (OC20) [24] | - | - | - |

| AlphaNet | - | - | 19.4 (Graphene) [24] | - |

| SFTGNN | State-of-the-art [21] | State-of-the-art [21] | - | State-of-the-art [21] |

Computational Efficiency and Scalability

Computational efficiency presents significant trade-offs between architectural complexity and performance. ALIGNN's explicit angle enumeration with O(k²) complexity can substantially impact computational efficiency, particularly for systems with dense local atomic environments [21]. In practical terms, SFTGNN demonstrates 5.3× faster training times compared to ALIGNN while maintaining competitive accuracy across multiple property prediction tasks [21].

For large-scale molecular dynamics simulations, inference speed and memory usage become critical factors. Frame-based approaches like AlphaNet eliminate the computational overhead of calculating tensor products of irreducible representations, significantly improving efficiency while maintaining accuracy [24]. This makes them particularly suitable for extended simulations of complex systems.

Table 2: Computational Efficiency Comparison

| Model | Computational Complexity | Training Efficiency | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALIGNN | O(k²) for angles [21] | 5.3× slower than SFTGNN [21] | Explicit angle modeling |

| SchNet | O(k) for distances [21] | Faster than ALIGNN [21] | Efficient periodic boundaries |

| SFTGNN | O(k) for angles [21] | Benchmark [21] | Spherical harmonics |

| AlphaNet | Efficient frame-based [24] | High inference speed [24] | No tensor products |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Training and Evaluation Protocols

Robust benchmarking requires standardized training methodologies across models. For property prediction tasks, the ALIGNN framework utilizes a root directory containing structure files (POSCAR, .cif, .xyz, or .pdb formats) with an accompanying id_prop.csv file listing filenames and target values [22]. The dataset is typically split in 80:10:10 ratio for training-validation-test sets, controlled by train_ratio, val_ratio, and test_ratio parameters in the configuration JSON file [22].

The MatUQ benchmark framework employs an uncertainty-aware training protocol combining Monte Carlo Dropout (MCD) and Deep Evidential Regression (DER) [20]. This approach achieves up to 70.6% reduction in mean absolute error on challenging OOD scenarios while estimating both epistemic and aleatoric uncertainty [20]. For force field training, ALIGNN-FF uses a JSON format containing entries for energy (stored as energy per atom), forces, and stress, compiled from DFT calculations such as vasprun.xml files [22].

Out-of-Distribution Evaluation Strategies

Meaningful evaluation requires rigorous OOD testing methodologies. The MatUQ benchmark introduces SOAP-LOCO (Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions - Leave-One-Cluster-Out), a structure-based data-splitting strategy that captures localized atomic environments with high fidelity [20]. This approach provides more realistic and challenging OOD evaluation compared to traditional clustering-based methods using overall structure descriptors, as it directly addresses the atomic-scale structural patterns that govern GNN message passing [20].

Additional OOD generation strategies include:

- Leave-One-Cluster-Out (LOCO): Creates test sets based on sparsely populated regions in composition or property space [20]

- SparseX and SparseY: Generate test sets in low-density regions of the data manifold [20]

- OFM-based splits: Utilize overall structure descriptors to simulate distribution shifts [20]

Standardized experimental workflow for benchmarking structure-aware GNNs [22] [20].

Research Reagent Solutions and Tools

Essential Software and Computational Tools

Implementing structure-aware GNNs requires specific software frameworks and computational resources. The ALIGNN implementation is publicly available via GitHub and can be installed through conda, pip, or direct repository cloning [22]. Critical dependencies include PyTorch, DGL (Deep Graph Library), and specific CUDA toolkits for GPU acceleration [22].

For force field development and molecular dynamics simulations, ALIGNN-FF provides pre-trained models capable of modeling diverse solids with any combination of 89 elements from the periodic table [22] [23]. These enable structural optimization, phonon calculations, and interface modeling without requiring expensive DFT calculations for each new configuration [22].

Benchmarking Datasets and Materials

Standardized datasets enable fair model comparison and reproducibility. Key resources include:

- JARVIS-DFT: Contains approximately 75,000 materials and 4 million energy-force entries covering 89 elements [22] [23]

- Materials Project (MP): Provides extensive crystal structure data and calculated properties [21]

- Open Catalyst 2020 (OC20): Focused on catalytic systems with 2M+ relaxations [24]

- Matbench Suite: Standardized prediction tasks with unified splits and metrics [20]

- QM9: Molecular dataset with quantum chemical properties for organic molecules [23]

Table 3: Essential Research Resources

| Resource Type | Specific Tools/Datasets | Primary Function | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Frameworks | ALIGNN, SchNet, DGL, PyTorch | Model implementation | GitHub, conda, pip [22] |

| Pre-trained Models | ALIGNN-FF, CHGNet, MACE | Transfer learning, force fields | Figshare, public repositories [22] |

| Benchmark Datasets | JARVIS-DFT, Materials Project, QM9 | Training and evaluation | Public portals, API [22] [23] |

| Evaluation Frameworks | MatUQ, Matbench | Standardized benchmarking | GitHub, public code [20] |

Implications for Synthesizability and Charge-Balancing Research

Structure-aware GNNs provide powerful tools for connecting atomic-scale structure with macroscopic synthesizability. ALIGNN's accurate prediction of formation energies and energies above the convex hull directly informs thermodynamic stability assessments crucial for synthesizability predictions [25]. Recent advancements in cross-modal knowledge transfer demonstrate that enhancing composition-based predictors with structural information improves performance on formation energy prediction by up to 39.6% [25].

For charge-balancing research, models capturing angular interactions show improved performance on electronic properties like band gaps and dielectric constants [23] [25]. The explicit modeling of three-body correlations in ALIGNN enables more accurate description of electron density distributions and polarization effects, which are critical for understanding charge transfer and balance in complex materials.

The integration of uncertainty quantification in frameworks like MatUQ further enhances the reliability of synthesizability predictions, allowing researchers to identify when models are extrapolating beyond their reliable domain [20]. This is particularly valuable for exploring novel material compositions where charge-balancing considerations might deviate significantly from training data distributions.

The discovery of new functional materials is a cornerstone of technological advancement, from developing new pharmaceuticals to creating next-generation batteries. Computational methods, particularly density functional theory (DFT), have successfully identified millions of candidate materials with promising properties. However, a critical bottleneck remains: determining whether a theoretically predicted crystal structure can be successfully synthesized in a laboratory. This property, known as "synthesizability," represents the significant gap between in silico predictions and real-world applications. Conventional approaches for assessing synthesizability have relied on thermodynamic or kinetic stability metrics, such as formation energy or phonon spectrum analysis. Unfortunately, these methods often prove inadequate; many structures with favorable formation energies remain unsynthesized, while various metastable structures with less favorable energies are successfully synthesized. This limitation highlights the complex, multi-factorial nature of chemical synthesis, which depends on precursor choice, reaction conditions, and pathway kinetics, factors not captured by stability metrics alone [3].

The emergence of large language models (LLMs) offers a transformative approach to this challenge. By training on vast amounts of scientific text and data, LLMs can learn complex, implicit patterns that govern material synthesis. The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models (CSLLM) framework represents a groundbreaking application of this technology. It moves beyond traditional machine learning models by employing specialized LLMs to accurately predict synthesizability, suggest viable synthetic methods, and identify appropriate precursors, thereby bridging the gap between theoretical materials design and experimental realization [3]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of the CSLLM framework against traditional and alternative machine learning approaches, with a specific focus on its performance within the critical context of benchmarking against charge-balancing and other physical constraints.

CSLLM Framework: A Specialized Architecture for Synthesis Prediction

The CSLLM framework is not a single model but an integrated system of three specialized LLMs, each fine-tuned for a distinct subtask in the synthesis prediction pipeline. This modular architecture allows for targeted, high-fidelity predictions across the entire synthesis planning workflow [3].

- Synthesizability LLM: This core component is tasked with a binary classification: determining whether a given 3D crystal structure is synthesizable or non-synthesizable. It was fine-tuned on a massive, balanced dataset containing 70,120 synthesizable crystal structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) and 80,000 non-synthesizable structures identified from a pool of over 1.4 million theoretical structures using a positive-unlabeled (PU) learning model. This careful dataset construction was crucial for training a robust predictor [3].

- Method LLM: Once a structure is deemed synthesizable, this model classifies the most plausible synthetic pathway. It distinguishes between major method categories, such as solid-state or solution-based synthesis, providing crucial guidance for experimentalists on where to begin [3].

- Precursor LLM: This model addresses the critical question of "what to use." It identifies suitable chemical precursors required for the synthesis of specific binary and ternary compounds, a task that traditionally requires deep expert knowledge [3].

A key innovation enabling the use of LLMs for this structural problem is the development of a novel text representation for crystal structures, termed "material string." Traditional crystal structure representations, like CIF or POSCAR files, contain redundant information and are not optimized for LLM processing. The material string overcomes this by providing a concise, reversible text format that comprehensively captures essential crystal information, including lattice parameters, composition, atomic coordinates, and symmetry, in a form digestible by language models [3].

Performance Benchmarking: CSLLM vs. Alternative Approaches

Quantitative benchmarking demonstrates that LLM-based approaches like CSLLM significantly outperform traditional methods for synthesizability prediction. The following table summarizes the performance of CSLLM against other common techniques.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

| Method Category | Specific Model / Metric | Key Performance Metric | Accuracy / Performance | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamic | Energy Above Hull (≥ 0.1 eV/atom) | Synthesizability Classification | 74.1% [3] | Fails on many metastable and stable-but-unsynthesized materials. |

| Kinetic | Phonon Spectrum (Lowest Freq. ≥ -0.1 THz) | Synthesizability Classification | 82.2% [3] | Computationally expensive; structures with imaginary frequencies can be synthesized. |

| Previous ML | Teacher-Student Dual Neural Network | Synthesizability Classification | 92.9% [3] | Limited explainability; performance plateaus. |

| LLM-based | CSLLM (Synthesizability LLM) | Synthesizability Classification | 98.6% [3] | Requires curated dataset and text representation; limited to trained chemistries. |

| LLM-based | StructGPT-FT (Ablation Study) | Synthesizability Classification | ~85% Precision, ~80% Recall [19] | Shows the value of structural information over composition-only models. |

| LLM-Embedding Hybrid | PU-GPT-Embedding Model | Synthesizability Classification | Outperforms StructGPT-FT and graph-based models [19] | Combines LLM's representation power with dedicated PU-classifier. |

The superiority of the CSLLM framework is further validated by its performance on specialized downstream tasks, where it provides functionality largely absent from traditional models.

Table 2: Performance of CSLLM on Downstream Synthesis Tasks

| CSLLM Component | Task Description | Performance | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Method LLM | Classifying possible synthetic methods (e.g., solid-state vs. solution) | 91.0% Accuracy [3] | Guides experimentalists toward viable synthetic routes. |

| Precursor LLM | Identifying solid-state synthetic precursors for binary/ternary compounds | 80.2% Success Rate [3] | Automates a knowledge-intensive task, accelerating experimental planning. |