Balancing Act: How to Select the Right DFT Functional for Accuracy vs. Computational Cost in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on navigating the critical trade-off between accuracy and computational cost when selecting Density Functional Theory (DFT) functionals.

Balancing Act: How to Select the Right DFT Functional for Accuracy vs. Computational Cost in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on navigating the critical trade-off between accuracy and computational cost when selecting Density Functional Theory (DFT) functionals. We explore the foundational hierarchy of functionals, from GGA to hybrid and double-hybrid methods, and their direct application in modeling drug-receptor interactions, reaction mechanisms, and spectroscopic properties. The guide offers practical troubleshooting strategies for common failures like self-interaction error and dispersion neglect, and presents a framework for systematic validation against experimental and high-level computational benchmarks. The goal is to empower scientists to make informed, project-specific functional choices that optimize resources without compromising the predictive reliability essential for biomedical innovation.

Understanding the DFT Functional Landscape: From LDA to Machine Learning-Infused Methods

Technical Support Center: DFT Functional Selection & Performance Issues

Troubleshooting Guide

Issue 1: My DFT calculation is taking far too long for my system size.

- Possible Cause: You are likely using a high-level hybrid functional (e.g., HSE06, B3LYP) or a method with a large basis set.

- Solution A (Speed Focused): Switch to a Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) functional like PBE. Consider using a smaller basis set or employing pseudopotentials. Utilize k-point reduction or Γ-point sampling for large cells.

- Solution B (Balanced Approach): Use the "system-specific functional selection" protocol (see Experimental Protocols below).

Issue 2: My band gap/ reaction energy/ binding energy is inaccurate compared to experiment.

- Possible Cause: You are using a functional known for poor performance for that specific property (e.g., PBE underestimates band gaps).

- Solution A (Accuracy Focused): For band gaps, use a hybrid functional (HSE06) or a meta-GGA like SCAN. For reaction energies, consider double-hybrid functionals or higher-level wavefunction methods if feasible.

- Solution B (Balanced Approach): Perform a benchmark on a known test set (e.g., MGGA-MS55) for your property of interest to select the best cost-accuracy functional.

Issue 3: I encounter convergence failures in my self-consistent field (SCF) cycle.

- Possible Cause: Complex electronic structure, metallic systems, or poor initial guesses.

- Solution: Use smearing (e.g., Methfessel-Paxton) for metals. Employ a charge density mixing algorithm (Kerker, Pulay). Start from a superposition of atomic densities or a converged calculation from a simpler functional.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the single biggest factor determining DFT calculation time? A1: The type of functional is paramount. The computational cost scales approximately as: LDA < GGA (PBE) < meta-GGA (SCAN) < Hybrid GGA (HSE06) < Hybrid meta-GGA. The exact exchange mixing percentage is a key driver of cost.

Q2: Can I get both high accuracy and high speed? A2: Not universally. This is the core trade-off. Your goal is to find the functional with the lowest computational cost that still delivers the required accuracy for your specific property and system. This is the thesis of system-aware functional selection.

Q3: For drug development (non-covalent interactions), what functional should I start with? A3: For initial speed, use a GGA like PBE-D3 (with dispersion correction). For publication-quality accuracy on binding energies, you will likely need a hybrid functional like ωB97X-D or a double-hybrid, acknowledging the significant increase in cost.

Q4: How do I formally decide which functional to use? A4: Follow a benchmarking protocol. Select a small, representative test set of molecules or materials where the property you need (e.g., adsorption energy, lattice constant) is known experimentally or from high-level theory. Test multiple functionals across the cost spectrum and compare performance using metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE).

Quantitative Data: Functional Performance vs. Cost

Table 1: Typical Relative Computational Cost & Accuracy Trends for Common Functionals

| Functional Class | Example | Relative Cost Factor (vs. LDA) | Typical Accuracy Weakness | Typical Accuracy Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDA | LDA | 1 | Severe bond length/energy error, band gaps | Speed, structure for simple metals |

| GGA | PBE, RPBE | 1.2 - 1.5 | Band gaps, dispersion forces | Good structures, general-purpose speed |

| meta-GGA | SCAN, r²SCAN | 2 - 5 | Still underestimates gaps | Improved energies vs. GGA, no empiricism |

| Hybrid GGA | HSE06, PBE0 | 10 - 50 | Cost, metallic systems | Good band gaps, improved thermochemistry |

| Double-Hybrid | DSD-PBEP86 | 100 - 500+ | Very high cost, scaling | High chemical accuracy (≈1 kcal/mol) |

Note: Cost factors are approximate and highly dependent on implementation, system size, and basis set.

Table 2: Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for Selected Test Sets (Illustrative)

| Functional | G3/05 Thermochemistry (kcal/mol) | S22 Non-Covalent Binding (kcal/mol) | Lattice Constant (Å) | Band Gap (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBE | 8.5 | >2.0 (without D3) | ~0.02 | ~1.0 (Underestimate) |

| SCAN | 4.5 | ~0.8 | ~0.01 | ~0.7 (Underestimate) |

| HSE06 | 4.0 | ~0.6 | ~0.01 | ~0.3 (Good) |

| Target "Chemical Accuracy" | < 1.0 | < 0.5 | < 0.01 | < 0.1 |

Data is a synthesis from recent benchmarks (e.g., MGGA-MS55, GMTKN55). Actual values vary by test set.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: System-Specific Functional Selection Benchmarking

- Define Target Property: Choose one primary property (e.g., adsorption energy, band gap, formation enthalpy).

- Build Test Set: Assemble 5-10 systems with reliable experimental or CCSD(T)/QMC reference data.

- Select Functionals: Choose 3-5 functionals spanning the cost spectrum (e.g., PBE, SCAN, HSE06, one higher-cost option).

- Standardize Calculation: Use identical computational parameters (k-points, cutoff, convergence) for all systems/functionals.

- Compute & Analyze: Calculate the property. Compute MAE and Root-Mean-Square Error (RMSE) for each functional.

- Decision Point: Select the functional with the lowest cost that meets your pre-defined accuracy threshold (e.g., MAE < 0.05 eV).

Protocol 2: Convergence Testing Workflow

- Energy Cutoff: Increase plane-wave cutoff until total energy change < 1 meV/atom.

- k-Point Sampling: Densify k-point mesh until total energy change < 1 meV/atom.

- Lattice Relaxation: Converge forces to a threshold of < 0.01 eV/Å.

- Self-Consistency: Tighten SCF convergence until energy change < 10⁻⁶ eV. Always perform this test with your chosen functional on a representative system before production runs.

Diagrams

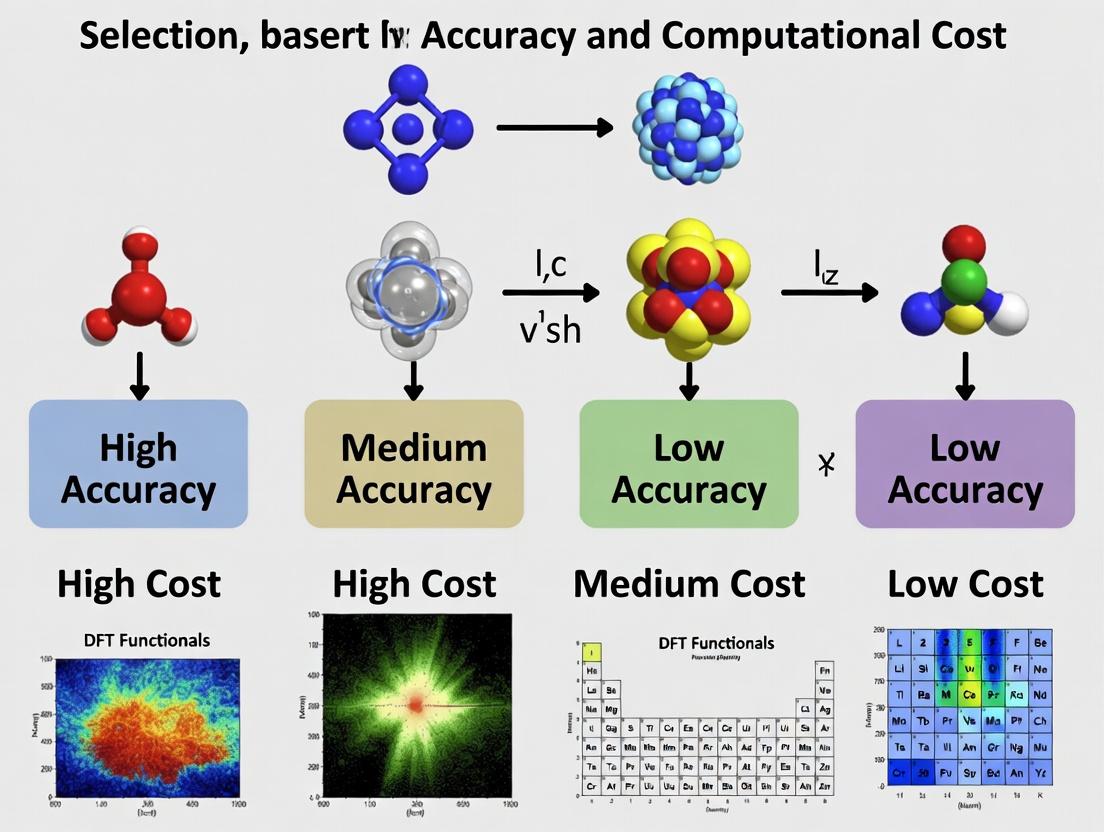

Diagram 1: The DFT Accuracy-Speed Trade-Off Decision Flow

Diagram 2: DFT Functional Hierarchy & Computational Cost Scaling

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Materials for DFT Studies

| Item/Software | Primary Function | Key Consideration for Trade-Off |

|---|---|---|

| VASP | Plane-wave DFT code with extensive functional library. | Efficient scaling; good for solids/surfaces. Cost scales with functional choice. |

| Gaussian, ORCA | Quantum chemistry packages for molecular DFT. | Excellent for hybrid functionals, wavefunction methods. Critical for molecular drug design. |

| CP2K | DFT code using mixed Gaussian/plane-wave basis. | Efficient for large, complex systems (e.g., electrolytes, biomolecules). |

| Pseudopotential Library (PSLIB) | Replaces core electrons to reduce cost. | Softer pseudopotentials allow lower cutoff but require validation. |

| Dispersion Correction (D3, vdW-DF) | Adds van der Waals interactions. | Essential for molecular/drug systems. Adds negligible cost but critical for accuracy. |

| Benchmark Database (MGGA-MS55) | Reference data for functional testing. | Required for executing Protocol 1 and making evidence-based functional selections. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My GGA calculation on an organic molecule yields a band gap that is severely underestimated compared to experiment. What is the likely cause and how can I resolve it? A1: This is a well-known limitation of local (LDA) and semi-local (GGA) functionals, often called the "band gap problem." They suffer from self-interaction error and lack a derivative discontinuity, systematically underestimating fundamental gaps.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify: Confirm the system is not metallic by checking the density of states (DOS) plot. A small but non-zero DOS at the Fermi level indicates possible underestimation.

- Solution: Move to a higher rung on Jacob's Ladder. Use a hybrid functional (e.g., B3LYP, PBE0) which mixes in exact Hartree-Fock exchange. For a more rigorous but costly fix, use a range-separated hybrid (e.g., HSE06) or a double-hybrid functional.

- Workflow Protocol: Perform a single-point energy calculation on the converged GGA geometry using the higher-rung functional. For large systems, consider using the

ACFDTflag for approximate correlation in hybrids or employing localized basis sets to reduce cost.

Q2: When performing a geometry optimization for a transition metal complex with a meta-GGA (e.g., SCAN), my calculation fails to converge or yields unrealistic bond lengths. What could be wrong? A2: Meta-GGAs depend on the kinetic energy density, which can be sensitive to numerical noise and require higher-quality integration grids and tighter convergence criteria.

- Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Increase Integration Grid: Switch from a medium (e.g.,

Grid=4) to a fine grid (e.g.,Grid=5orInt=UltraFine). - Tighten Convergence: Set stricter criteria for energy (

SCFConv=8), forces (ForceConv=6), and geometry steps (MaxStep=0.1). - Check Initial Guess: Use a stable initial density guess from a converged GGA calculation (

Guess=Read). - Verify Functional Suitability: Some meta-GGAs can have stability issues for certain spin states. Consult literature for known performance on similar complexes.

- Increase Integration Grid: Switch from a medium (e.g.,

Q3: My double-hybrid functional calculation is prohibitively expensive. What practical strategies can I use to include its benefits in my research on drug-sized molecules? A3: Double-hybrids (e.g., B2PLYP) add a second-order perturbation correction, scaling as O(N⁵), making them costly for large molecules.

- FAQs & Solutions:

- Q: Can I use double-hybrids for geometry optimization? A: Typically, no. The standard protocol is to optimize geometry with a cheaper GGA or hybrid functional, then perform a single-point energy calculation with the double-hybrid for improved energetics (e.g., binding affinity, reaction energy).

- Q: Are there efficiency tricks?

A: Yes. Use the Resolution-of-the-Identity (RI) or density fitting approximation for the perturbative correlation part (e.g.,

RIJCOSXandAuxiliarybasis sets). This can reduce cost by an order of magnitude. - Workflow Protocol:

- Geometry Optimize with PBE0-D3/def2-SVP.

- Frequency calculation at same level to confirm minima and obtain thermal corrections.

- Final Single-Point Energy with e.g., DSD-BLYP-D3/def2-QZVP using RI approximation.

Table 1: Functional Rungs - Typical Error Ranges and Computational Scaling Note: Errors are illustrative trends for molecular properties. Actual errors depend strongly on the system and property.

| Functional Rung | Example Functionals | Typical Error (e.g., Atomization Energy) | Computational Scaling (vs. LDA) | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDA | SVWN5 | 50-100 kcal/mol (Large Error) | 1.0x (Reference) | Quick electron density estimates, jellium models. |

| GGA | PBE, BLYP | 10-20 kcal/mol | 1.1x - 1.3x | Standard geometry optimizations, large system MD. |

| meta-GGA | SCAN, TPSS | 5-15 kcal/mol | 1.5x - 2.5x | Improved geometries for solids, surfaces, and some reaction barriers. |

| Hybrid | PBE0, B3LYP | 4-10 kcal/mol | 5x - 50x (HF cost dominates) | Accurate molecular properties, band gaps, reaction thermochemistry. |

| Double-Hybrid | B2PLYP, DSD-PBEP86 | 2-5 kcal/mol | 50x - 500x (O(N⁵) scaling) | Benchmark-quality energetics (binding, barriers) for small/medium molecules. |

Table 2: Recommended Functional Selection Protocol for Drug Development

| Research Question | Recommended Functional(s) (Balance) | Recommended Basis Set | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Virtual Screening | GFN2-xTB (Semi-empirical), PBE-D3/def2-SV(P) | Minimal (Speed) | Speed is critical. Accuracy sacrificed for throughput. |

| Ligand-Protein Docking/MM-PBSA | PM6-D3H4, B3LYP-D3/6-31G* | Small | Must interface with MM force fields. Partial charges often needed. |

| Conformational Analysis | PBE-D3/def2-SVP, ωB97X-D/6-31G* | Split-Valence | Must describe weak dispersion (D3 correction). Cost allows for many single-points. |

| Reaction Mechanism (Barriers) | B3LYP-D3/def2-TZVP, M06-2X/6-311+G | Triple-Zeta + Diffuse | Requires transition state search. Hybrids/meta-hybrids often necessary. |

| Benchmark Binding Affinity | Protocol: PBE0-D3/def2-TZVP (Opt/Freq) → DLPNO-CCSD(T)/def2-QZVPP (SP) | Mixed | "Gold standard" protocol. Double-hybrid or wavefunction theory for final SP. |

Experimental & Computational Protocols

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Functional Accuracy for Reaction Energy Objective: Determine the most cost-effective functional for catalyzed reaction energies in your chemical space.

- Reference Set: Select 20-50 small-molecule reactions with reliable experimental or CCSD(T) reaction energies (e.g., from databases like GMTKN55).

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize all reactants and products using a consistent, mid-tier method (e.g., PBE0/def2-SVP) with tight convergence. Apply a dispersion correction (D3(BJ)).

- Frequency Calculation: At the same level, confirm minima (no imaginary frequencies) and obtain zero-point energy and thermal corrections (298 K, 1 atm).

- High-Rung Single Points: Perform single-point energy calculations on all optimized structures using a series of functionals: GGA (PBE), meta-GGA (SCAN), hybrid (PBE0, B3LYP), double-hybrid (B2PLYP).

- Analysis: Compute Mean Absolute Errors (MAE) and Root Mean Square Errors (RMSE) for the reaction energies (including thermal corrections) against the reference set. Plot cost (CPU time) vs. accuracy (MAE).

Protocol 2: Calculating Ligand-Protein Binding Affinity (ΔG_bind) Objective: Compute the binding free energy of a drug candidate to a protein active site.

- System Preparation: Obtain protein-ligand complex from docking or crystal structure. Add hydrogens, assign protonation states, solvate in a water box, add ions.

- Classical MD Simulation: Run equilibration and production MD using an Amber/CHARMM force field. (This step is primarily MM).

- QM Region Selection: From the MD trajectory, extract snapshots. Define the QM region as the ligand and key active site residues (e.g., within 5Å of ligand).

- QM/MM Setup: Treat the QM region with a DFT functional (e.g., B3LYP-D3/6-31G*) and the rest with MM.

- Energy Calculation: Perform QM/MM single-point calculations on multiple snapshots. Calculate the interaction energy for each.

- Free Energy Estimate: Average the interaction energies. Apply Poisson-Boltzmann/Surface Area (MM-PBSA/GBSA) corrections from the classical MD to estimate ΔG_bind. Note: For higher accuracy, the QM region can be treated with a double-hybrid in a single-point correction on a representative snapshot.

Visualizations

Title: Jacob's Ladder of DFT Functional Rungs

Title: DFT Functional Selection Decision Tree

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Materials for DFT Studies

| Item / "Reagent" | Function & Explanation | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Basis Set | Mathematical functions to describe electron orbitals. Larger sets are more accurate but costly. | def2-SVP (small), def2-TZVP (medium), def2-QZVP (large). cc-pVXZ series for wavefunction methods. |

| Pseudopotential (PP) / Effective Core Potential (ECP) | Replaces core electrons for heavy atoms, reducing cost. Essential for elements > Kr. | def2-ECP for 4d/5d metals. Always use matching PP/basis set. |

| Dispersion Correction | Adds van der Waals (dispersion) forces missing in most standard functionals. | -D3, -D3(BJ) (Grimme), -D4. Always use for non-covalent interactions. |

| Integration Grid | Numerical grid for integrating functionals. Finer grids improve accuracy, especially for meta-GGAs. | Grid=4 (Medium), Grid=5 (Fine), Int=UltraFine. |

| Solvation Model | Mimics solvent effects implicitly via a continuum dielectric. | SMD (universal), CPCM, COSMO. Crucial for solution-phase chemistry. |

| RI / Density Fitting Basis | Auxiliary basis set to accelerate calculation of 2-electron integrals, drastically reducing cost. | def2/J, def2-TZVP/C for Coulomb (RI-J). cc-pV5Z/MP2FIT for correlation in double-hybrids. |

| Geometry Constraints | "Fixes" atoms during optimization to mimic crystal environment or preserve part of a large system. | $freeze (in xyz), Opt=ModRedundant. Used in QM/MM or surface calculations. |

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My DFT calculation on an organic molecule cluster shows drastically underestimated binding energy. Which functional ingredient is most likely missing? A: This is a classic symptom of missing dispersion corrections. Standard semi-local functionals (e.g., PBE) fail to describe long-range electron correlation (van der Waals forces). You must apply an empirical dispersion correction (e.g., DFT-D3, D4) or use a non-local functional (e.g., vdW-DF2). The correction adds minimal computational overhead (<5%) but is critical for accuracy in supramolecular systems.

Q2: When modeling a transition metal complex, my calculated reaction barrier is significantly off compared to experiment. Should I prioritize hybrid functionals or better basis sets? A: For transition metals, the description of exchange-correlation is often the dominant error. Prioritize moving from a GGA (e.g., PBE) to a hybrid functional (e.g., PBE0, B3LYP) to include exact Hartree-Fock exchange, which improves barrier heights and electronic structure. This increases cost significantly (10-100x). Only after selecting an appropriate functional should you systematically improve the basis set.

Q3: I added DFT-D3 corrections, but my calculated lattice parameters for a molecular crystal are still inaccurate. What is the next step? A: The dispersion correction is likely adequate, but the underlying exchange-correlation functional may be insufficient. Consider a meta-GGA (e.g., SCAN) or a hybrid functional. Be aware that SCAN alone has some medium-range correlation but may still benefit from a dispersion add-on (SCAN-D3). This step will substantially increase computational cost.

Q4: My periodic calculation with a hybrid functional is computationally prohibitive. Are there efficient alternatives? A: Yes. Consider range-separated hybrid functionals (e.g., HSE06) which apply exact exchange only to short-range interactions, drastically reducing cost in periodic systems. Alternatively, use screened hybrid functionals or the "ghost" interaction correction in some codes. For very large systems, double-hybrid functionals are not recommended due to extreme cost.

Troubleshooting Guide

| Symptom | Likely Culprit | Diagnostic Check | Solution & Cost Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Underbound molecular complexes, soft materials | Missing dispersion forces. | Compare PBE vs. PBE-D3 results on a dimer. | Add DFT-D3/D4 correction. Cost: Negligible increase. |

| Over-delocalized electrons, band gap error | Insufficient exact exchange. | Compare HOMO-LUMO gap from PBE vs. PBE0. | Switch to hybrid functional (e.g., PBE0). Cost: High (10-100x GGA). |

| Inaccurate reaction energetics, barrier heights | Poor exchange-correlation description. | Test on a known benchmark set (e.g., GMTKN55). | Use hybrid or meta-hybrid (e.g., SCAN0). Cost: Very High. |

| Slow SCF convergence with hybrids | Increased non-locality. | Monitor SCF cycles; check for metallic character. | Improve k-grid, use smearing, better mixer. Cost: Increased time per cycle. |

| Good energies but poor geometries | Error cancellation failing. | Validate geometries against CCSD(T) benchmarks. | Use a functional parameterized for geometries (e.g., ωB97X-D). Cost: High (hybrid + dispersion). |

Table 1: Representative Functional Types, Ingredients, and Relative Cost Cost normalized to a single GGA (PBE) calculation on a medium-sized system.

| Functional Class | Key Physical Ingredients | Example(s) | Typical Relative Computational Cost | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GGA | Semi-local exchange, semi-local correlation. | PBE, RPBE, BLYP | 1x (Baseline) | Preliminary screening, metallic systems. |

| Meta-GGA | GGA + kinetic energy density. | SCAN, TPSS | 1.5x - 3x | Improved geometries, diverse solids. |

| Hybrid | GGA/MGGA + % Exact HF Exchange. | PBE0, B3LYP, HSE06 | 10x - 100x | Electronic gaps, reaction barriers. |

| Double-Hybrid | Hybrid + % MP2 correlation. | B2PLYP, DSD-PBEP86 | 100x - 1000x | High-accuracy thermochemistry. |

| Dispersion Corrections | Empirical pairwise potentials. | DFT-D3, DFT-D4 | <0.05x (add-on) | All non-covalent interactions. |

Table 2: Accuracy vs. Cost for Selected Functionals (Generalized Trends) Based on broad benchmarks like GMTKN55 for molecular systems.

| Functional | Dispersion Included? | Typical Accuracy (kcal/mol) | Relative Cost | Cost-Performance Sweet Spot |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBE | No | >10 | 1x | Bulk materials, fast surveys. |

| PBE-D3 | Yes (add-on) | ~5-8 | ~1x | Non-covalent interactions, biomolecules. |

| SCAN | Some (medium-range) | ~4-6 | 2-3x | Solids, diverse chemistry. |

| B3LYP-D3 | Yes (add-on) | ~3-5 | 30-50x | Organic/molecular chemistry. |

| ωB97X-D | Yes (internal) | ~2-3 | 50-80x | High-accuracy molecular design. |

| DSD-PBEP86-D3 | Yes (add-on) | ~1-2 | 500x+ | Benchmarking, small molecule refinement. |

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking Functional Performance

Protocol Title: Systematic Evaluation of DFT Functionals for Organic Molecule Binding Energies.

Objective: To determine the optimal exchange-correlation and dispersion combination for predicting non-covalent binding energies relevant to drug fragment docking.

Materials (The Scientist's Toolkit):

| Research Reagent Solution | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| GMTKN55 Database Subset | Provides benchmarked experimental/CCSD(T) binding energies for organic dimers (e.g., S66, L7). |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Computational engine (e.g., ORCA, Gaussian, VASP with appropriate settings). |

| Consistent Basis Set | Defines the mathematical basis for electron orbitals (e.g., def2-TZVP with matching auxiliary basis). |

| Dispersion Correction Library | Implements empirical corrections (e.g., DFT-D3(BJ) with Becke-Johnson damping). |

| Scripting/Analysis Toolkit | Automates job submission, data extraction, and error statistical analysis (MAE, RMSE). |

Methodology:

- System Selection: Choose a representative benchmark set (e.g., the S66x8 dataset of 66 dimer complexes at 8 separation distances).

- Computational Setup: Select a suite of functionals: PBE, PBE-D3, B3LYP, B3LYP-D3, ωB97X-D, SCAN, SCAN-D3. Use a consistent, medium-to-large basis set (e.g., def2-TZVP) and tight convergence criteria.

- Geometry Processing: For each dimer, perform a single-point energy calculation on the experimentally derived or high-level optimized geometry. This isolates the functional's energy error.

- Energy Calculation: Run single-point calculations for each monomer (A, B) and the complex (AB) using all chosen functionals.

- Binding Energy Computation: Calculate the binding energy: ΔEbind = EAB - (EA + EB). Apply counterpoise correction for Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE) if not using a very large basis set.

- Error Analysis: Compute the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) for each functional against the reference data.

- Cost Measurement: Record the computational time (CPU hours) for a representative system (e.g., the largest dimer) for each functional.

- Data Synthesis: Plot accuracy (MAE) vs. computational cost (time) to visualize the Pareto front of optimal functional choices.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: DFT Functional Selection Decision Pathway

Diagram 2: Computational Cost vs. Accuracy Trade-off

Diagram 3: DFT Calculation Workflow with Key Ingredients

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My ML-DFT (e.g., DM21) functional calculation is yielding unrealistic electron densities or convergence failures in my metal-organic system. What are the primary checks? A: This is often a training set mismatch. Follow this protocol:

- Verify System Similarity: Check if your system's elements and coordination chemistry are represented in the functional's training data (e.g., OE62 benchmark set). If not, the functional is extrapolating.

- Increase Integration Grid: ML functionals can have sharper features. Increase the integration grid size (e.g., from

DefGrid2toDefGrid3in ORCA, orIntAcc=4.0to5.0in Gaussian). - Stabilize SCF: Use tighter convergence criteria (

SCF=Tight) and consider switching to a different DFT optimizer (SCF=QCin Gaussian for problematic cases). - Fallback Protocol: Run a single-point energy calculation using a robust, traditional hybrid functional (e.g., PBE0) on the ML-optimized geometry to compare density profiles.

Q2: When benchmarking a Neural Network (NN) functional against traditional functionals for drug-like molecule energetics, what is the minimal recommended dataset and workflow to ensure statistical significance? A: Use the following experimental protocol:

- Dataset: Select a curated subset of 50-100 molecules from the

DrugBankdatabase or theCOMP6benchmark subset. Include diverse functional groups (amines, carbonyls, halogens). - Reference Data: Use DLPNO-CCSD(T)/CBS or

ωB97M-V/def2-QZVPPD calculations as your "gold standard" reference for energies. - Compute Settings: Perform single-point energy calculations on identical, pre-optimized geometries (B3LYP/def2-SVP level) using:

- The NN functional (e.g., OrbNet)

- A range GGA (PBE), hybrid (PBE0), and double-hybrid (B2PLYP) functionals.

- The same basis set (e.g., def2-TZVP) and integration grid for all.

- Analysis: Calculate Mean Absolute Errors (MAE) and Root Mean Square Errors (RMSE) for the energy differences (e.g., relative conformer energies) against the reference.

Q3: I am experiencing prohibitive computational costs with a neural network functional for geometry optimization of a medium-sized protein ligand (>150 atoms). Are there recommended strategies to reduce cost? A: Yes, employ a multi-level "embeddding" or "layered" approach:

- ONIOM-type Workflow: Use the NN functional only on the active site (e.g., ligand and binding pocket residues within 5Å). Treat the rest of the protein with a cheaper force field or semi-empirical method (GFN2-xTB).

- Protocol: a. Optimize the full system with GFN2-xTB. b. Freeze atoms beyond 10Å from the ligand. c. Perform optimization with the NN functional on the high-layer region, with electrostatic embedding from the low-layer region.

- Hardware Leverage: Ensure your software (like PySCF with

DeepDMET) utilizes GPU acceleration. The cost scaling of NN functionals is often steeper on CPU-only architectures.

Q4: How do I interpret the "black box" uncertainty estimation provided by some Bayesian NN functionals, and when should I distrust the prediction? A: The uncertainty metric (often a variance) is key for reliability.

- Thresholds: Establish an uncertainty threshold from calibration on known molecules. A prediction with variance > 10 mHa (≈ 6 kcal/mol) should be flagged for manual inspection.

- Action Protocol: If a prediction for reaction energy has high uncertainty:

- Re-calculate using a consensus of two other lower-cost ML functionals (e.g.,

SCANandr²SCAN). - If discrepancies are large, revert to a robust but expensive wavefunction method (DLPNO-CCSD(T)) for that specific data point.

- Report the uncertainty alongside the prediction in your results.

- Re-calculate using a consensus of two other lower-cost ML functionals (e.g.,

Data Presentation

Table 1: Performance Benchmark of Select Functionals on Drug-Relevant Benchmarks (MAE in kcal/mol)

| Functional Type | Functional Name | Relative Energy (CONF6) MAE | Isomerization Energy (ISO6) MAE | Computational Cost (Relative to PBE) | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GGA | PBE | 1.85 | 3.22 | 1.0 | Preliminary screening, large systems |

| Meta-GGA | SCAN | 1.12 | 1.98 | 1.8 | Accurate geometries, medium systems |

| Hybrid | PBE0 | 0.89 | 1.45 | 4.5 | Thermochemistry, single-point energies |

| Double-Hybrid | B2PLYP | 0.62 | 0.91 | 25.0 | High-accuracy benchmarks (small) |

| ML/Neural Network | DM21 | 0.55 | 0.80 | 8.0 | Electronic properties, charge transfer |

| ML/Neural Network | OrbNet (EquiBind) | 0.48 | 0.75 | 15.0* | Binding affinity prediction, specialized tasks |

Note: Cost highly dependent on GPU acceleration and model implementation.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Quick Reference Table

| Symptom | Likely Cause | First Action | Secondary Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCF convergence failure | Training set extrapolation, sharp density features | Increase integration grid density | Switch to a more robust SCF algorithm (DIIS+QC) |

| Unphysical bond lengths | Inadequate gradient training in NN | Validate geometry with a meta-GGA (SCAN) | Use NN functional only for single-point energy on a stable geometry |

| High computational time | O(N³) or worse scaling for large N | Implement embedding (ONIOM) scheme | Switch to a lower-rung ML potential for dynamics |

| Large error vs experiment | Benchmark set bias (e.g., missing dispersion) | Apply a posteriori dispersion correction (D4) | Use consensus prediction from 3 different functional classes |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Benchmarking Functional Cost-Accuracy for Tautomer Equilibrium Prediction Objective: To determine the optimal functional for predicting tautomer ratios in drug-like molecules. Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below. Methodology:

- Selection: Choose 20 prototypical tautomerizing systems (e.g., keto-enol, amine-imine) from the

TAUT15database. - Reference Geometry: Optimize all tautomers and conformers at the

B3LYP-D3(BJ)/def2-TZVPlevel with implicit solvation (SMD, water). Confirm minima via frequency analysis. - Single-Point Energy Evaluation: For each optimized structure, calculate electronic energies using:

- Target ML/NN functional (e.g.,

ANI-2x,PhysNet) - Comparator functionals:

ωB97X-D,PBE0-D3(BJ),M06-2X - High-level reference:

DLPNO-CCSD(T)/def2-QZVPP

- Target ML/NN functional (e.g.,

- Analysis: For each functional

i, compute the MAE in predicted tautomer energy difference vs. the DLPNO-CCSD(T) reference. Plot MAE against the average computational wall time per calculation to generate the cost-accuracy curve.

Protocol B: Validating NN Functional for Protein-Ligand Binding Pose Scoring Objective: To assess if an NN functional can improve pose ranking over traditional MM/GBSA. Materials: PDB structure of a target (e.g., kinase), docked ligand poses (from Glide or AutoDock). Methodology:

- Preparation: Isolate the protein-ligand complex for the top 50 docked poses. Prepare structures (add H, assign bonds) using

PDBFixerorMOE. - MM Optimization: Perform constrained geometry optimization (protein heavy atoms fixed) using the

GAFF2force field inOpenMM. - QM Scoring: For each pose, calculate the interaction energy using a neural network functional (e.g.,

OrbNet) on the ligand and all residues within 8Å. Use theDef2-SVPbasis set. Apply BSSE correction via the counterpoise method. - Correlation: Rank poses by the NN interaction energy. Calculate the Spearman rank correlation coefficient (ρ) between this ranking and the ranking based on the known experimental pose (or a high-quality MD-refined pose). Compare ρ to that obtained from MM/GBSA scores.

Mandatory Visualization

Title: Decision Workflow for Applying ML/NN Density Functionals

Title: ML Redefining the DFT Cost-Accuracy Curve

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Solution | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| OE62 Benchmark Database | A standardized set of 62 molecules and energies for training and testing ML-DFT models. Provides diverse chemical environments. |

| LibXC Software Library | Provides uniform access to >600 density functionals. Essential for consistent implementation and comparison between traditional and ML-enhanced functionals. |

| PySCF / DeepChem Framework | Python-based quantum chemistry environment with integrated ML toolkits. Enables custom implementation and training of neural network functionals. |

| GPU-Accelerated QM Code (e.g., QUICK, PySCF with CUDA) | Dramatically reduces the wall-time for evaluating neural network functionals, making them practical for drug-sized systems. |

| Dispersion Correction Parameters (D3(BJ), D4) | Most ML functionals do not include long-range dispersion. Adding these corrections a posteriori is crucial for biomolecular interactions. |

| CHEMDNER / DrugBank Dataset | Curated, annotated chemical structure databases essential for creating domain-specific (drug-like) training sets for transfer learning of NN functionals. |

| Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE) | Python scripting interface to automate workflows involving both traditional DFT and ML/NN potential calculations, enabling high-throughput benchmarking. |

Strategic Functional Selection for Drug Discovery: Applications from Binding Energies to Reaction Pathways

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: Why does my calculated molecular geometry differ significantly from experimental crystal structures?

Answer: This is often a functional limitation. Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) functionals like PBE tend to overestimate bond lengths. For accurate geometries, especially for main-group organic molecules, hybrid functionals like B3LYP or ωB97X-D are recommended. Always use a basis set with polarization functions (e.g., 6-31G*). For metal-organic complexes, consider meta-GGAs (e.g., SCAN) or double-hybrids for improved performance.

FAQ 2: My reaction energy barrier seems too low compared to experimental kinetics. What went wrong?

Answer: Standard GGA and hybrid functionals often underestimate reaction barriers due to self-interaction error. For accurate thermochemistry and kinetics (barrier heights), use a hybrid meta-GGA functional like M06-2X, or a range-separated hybrid like ωB97X-D. The Minnesota family (e.g., M06-2X) is parametrized for main-group thermochemistry. Double-hybrid functionals (e.g., DSD-PBEP86) offer higher accuracy at greater cost.

FAQ 3: My calculated UV-Vis absorption spectrum peaks are shifted relative to experiment. How can I correct this?

Answer: Peak shifts are common. Standard TD-DFT with GGA/hybrid functionals often suffers from charge-transfer excitation errors. For excitation energies and spectra:

- For local excitations: Range-separated hybrids like CAM-B3LYP or ωB97X-D are superior.

- For charge-transfer excitations: Long-range corrected functionals (e.g., LC-ωPBE) are essential.

- Always use a functional and basis set that includes diffuse functions (e.g., 6-31+G) for excited states.

Troubleshooting Guide: Systematically Improving Calculation Accuracy

| Symptom | Likely Culprit | Recommended Action | Expected Computational Cost Increase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor geometries (bonds, angles) | LDA/GGA functional, small basis set | Switch to hybrid (B3LYP) or meta-hybrid (M06-2X). Use basis set with polarization (def2-SVP). | Moderate (2-5x) |

| Underestimated binding/cohesion energy | Missing dispersion corrections | Add empirical dispersion (e.g., -D3, -D4) to your functional (e.g., B3LYP-D3). | Negligible |

| Incorrect ground state spin/ordering | Self-interaction error, insufficient correlation | Use hybrid (PBE0) or meta-GGA (SCAN). For transition metals, consider TPSSh or PBE0. | Moderate (3-10x) |

| Inaccurate band gap (solids) | GGA functional band gap error | Use hybrid (HSE06) or GW methods. | High (10-50x) |

| Shifted UV-Vis peaks | Standard functional for CT states | Use range-separated hybrid (CAM-B3LYP, ωB97X-D). | High (5-15x vs GGA) |

Table 1: DFT Functional Recommendations for Common Tasks

| Calculation Task | Recommended Functional Tier 1 (Best Value) | Recommended Functional Tier 2 (Higher Accuracy) | Critical Basis Set Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geometry Optimization (Organic) | ωB97X-D, B3LYP-D3(BJ) | DSD-PBEP86, PW6B95-D3(BJ) | Polarization (e.g., 6-31G*, def2-SVP) |

| Single-Point Energy (Thermochemistry) | ωB97X-D, M06-2X | DLPNO-CCSD(T), DSD-PBEP86 | Large, with diffuse/polarization (e.g., def2-TZVP) |

| Reaction Kinetics (Barrier Height) | M06-2X, ωB97X-D | DSD-PBEP86, DLPNO-CCSD(T) | As above; include solvent model |

| NMR Chemical Shifts | WP04, KT2, PBE0 | double-hybrids (DSD-PBEP86) | Large, with careful gauge treatment |

| UV-Vis Spectroscopy | CAM-B3LYP, ωB97X-D | EOM-CCSD, ADC(2) | Diffuse functions essential (e.g., 6-31+G) |

| Non-Covalent Interactions | ωB97X-D, B3LYP-D3(BJ) | DSD-PBEP86, MP2/CBS | Large basis; must include dispersion |

Experimental & Computational Protocols

Protocol 1: Benchmarking a Functional for Reaction Energy Barriers

- System Selection: Choose a set of 5-10 well-known reactions with reliable experimental barrier heights (e.g., from the NIST Computational Chemistry Comparison and Benchmark Database).

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize the reactant, transition state (TS), and product structures using a medium-level method (e.g., B3LYP-D3/6-31G*). Verify TS with frequency analysis (one imaginary frequency).

- High-Accuracy Single Point: Calculate the electronic energy for each optimized structure using the target functional (e.g., M06-2X) and a large basis set (e.g., def2-TZVP).

- Thermal Correction: Calculate zero-point energy and thermal corrections at the optimization level and add to the high-accuracy single-point energy.

- Solvation: Apply an implicit solvation model (e.g., SMD) consistent with experimental conditions.

- Benchmark: Calculate the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) against experimental values. Compare to errors from other functionals.

Protocol 2: Calculating a UV-Vis Absorption Spectrum

- Ground State Optimization: Fully optimize the molecule's geometry using a functional like ωB97X-D and a basis set like 6-31+G. Confirm it's a minimum (no imaginary frequencies).

- Excited State Calculation: Perform a Time-Dependent DFT (TD-DFT) calculation on the optimized geometry. Use a range-separated hybrid functional (CAM-B3LYP) with the same or larger basis set.

- States & Solvent: Request calculation of at least 10-20 excited states. Include the solvent environment via an implicit model (e.g., IEFPCM for acetonitrile).

- Spectrum Generation: Use visualization software (e.g., GaussView, Multiwfn) to simulate the spectrum by applying a line-broadening function (e.g., Gaussian, 0.3 eV FWHM) to the calculated excitations and oscillator strengths.

- Analysis: Inspect the molecular orbitals involved in key transitions to characterize the nature of the excitation.

Pathway & Workflow Visualizations

Decision Tree for DFT Functional Selection

DFT Accuracy Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Solution | Function in Computational Experiment |

|---|---|

| Software Suite (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA, Q-Chem) | Primary engine for performing DFT and ab initio calculations. Provides implementations of functionals, basis sets, and solvation models. |

| Basis Set Library (e.g., def2, cc-pVnZ, 6-31G*) | Mathematical sets of functions describing electron orbitals. Choice critically balances accuracy and computational cost. |

| Implicit Solvation Model (e.g., SMD, COSMO) | Mimics solvent effects without explicit solvent molecules, crucial for comparing to experiment in solution. |

| Empirical Dispersion Correction (e.g., D3(BJ), D4) | Adds van der Waals attraction forces missing in many standard functionals, vital for non-covalent interactions. |

| Molecular Visualization & Analysis (e.g., VMD, Multiwfn, GaussView) | For building input structures, visualizing molecular orbitals, charge densities, and analyzing results (e.g., spectra). |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Essential for performing calculations with high-level methods or large systems within a reasonable timeframe. |

| Benchmark Database (e.g., GMTKN55, S22, NIST CCCBDB) | Curated datasets of experimental/reference values for validating the accuracy of computational methods. |

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Center

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: My DFT calculations for a host-guest complex yield binding energies that are far too exothermic compared to experiment. What is the likely cause and how can I fix it? A: This is a classic symptom of basis set superposition error (BSSE). The small basis sets often used for large systems lack completeness, allowing fragments to artificially lower their energy by using each other's basis functions. Solution: Always apply the Counterpoise (CP) correction for final binding energy reporting. For geometry optimization, use a moderate basis set (e.g., def2-SVP) and then perform a single-point energy calculation with a larger basis set (e.g., def2-TZVP) and CP correction.

Q2: When modeling π-π stacking in a supramolecular system, my selected functional (e.g., B3LYP) fails to reproduce the correct parallel-displaced geometry. Why? A: Standard hybrid functionals like B3LYP lack long-range dispersion corrections, which are critical for describing π-π interactions. They often incorrectly predict a co-facial (eclipsed) stacking. Solution: Switch to a dispersion-corrected functional. Use a range-separated hybrid with D3(BJ) correction (e.g., ωB97X-D) or a double-hybrid functional (e.g., B2PLYP-D3(BJ)) for improved accuracy.

Q3: My protein-ligand interaction energy calculation is computationally prohibitive. How can I balance cost and accuracy? A: For large systems (>500 atoms), a pure QM treatment is often not feasible. Solution: Employ a QM/MM (Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics) approach. Use DFT (with dispersion correction) for the ligand and key protein residues (e.g., active site), and a fast MM force field for the rest of the protein. Alternatively, use a very fast, dispersion-corrected semi-empirical method (e.g., GFN2-xTB) for initial screening before higher-level DFT on promising candidates.

Q4: How do I choose between a double-hybrid functional and a dispersion-corrected meta-GGA for screening supramolecular catalysts? A: This is the core accuracy vs. cost trade-off. Refer to the benchmark table below. Use meta-GGAs (e.g., SCAN-D3(BJ)) for high-throughput screening of large libraries. Reserve double-hybrids (e.g., DSD-BLYP-D3(BJ)) for final validation of top-ranked systems due to their superior accuracy but ~100x higher cost.

Table 1: Performance of DFT Functionals for Non-Covalent Interactions (Mean Absolute Error in kcal/mol)

| Functional Class | Example Functional | S66 (General NC) | L7 (Protein-Ligand) | HSG (Supramolecular) | Relative Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Double-Hybrid + Disp. | DSD-BLYP-D3(BJ) | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | ~1000 |

| Range-Sep. Hyb. + Disp. | ωB97X-D3(BJ) | 0.2-0.3 | 0.4-0.6 | 0.6-0.8 | ~100 |

| Hybrid + Disp. | B3LYP-D3(BJ) | 0.4-0.5 | 0.6-1.0 | 1.0-1.5 | ~50 |

| Meta-GGA + Disp. | SCAN-D3(BJ) | 0.3-0.4 | 0.5-0.8 | 0.8-1.2 | ~10 |

| GGAs & No Disp. | PBE, B3LYP | >2.0 | >3.0 | >4.0 | 1 (Baseline) |

Data compiled from recent benchmarks (PSI4, GMTKN55). Cost is relative to a standard GGA for a single-point energy calculation.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Accurate Binding Energy Calculation for a Protein-Ligand Complex (Single-Point, QM Region)

- System Preparation: Extract the ligand and all protein residues within 5Å of it from a crystal structure (PDB ID). Cap valencies with hydrogen atoms.

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize the isolated ligand and the protein binding site fragment using a cost-effective method (e.g., GFN2-xTB or B3LYP-D3(BJ)/def2-SVP in vacuum). Keep heavy atoms of protein residues restrained (force constant 0.5 au).

- High-Level Single-Point Calculation: a. Perform a single-point energy calculation on the optimized complex using a target high-level functional (e.g., DSD-BLYP-D3(BJ)) and basis set (def2-QZVP). b. Perform identical calculations on the optimized ligand and protein fragments in isolation. c. Apply the Counterpoise correction to all three calculations to remove BSSE.

- Energy Calculation: Compute the binding energy: ΔEbind = E(complex, CP) - [E(ligand, CP) + E(proteinfragment, CP)].

Protocol 2: Benchmarking Functional Accuracy for Supramolecular Host-Guest Binding

- Dataset Selection: Select a reference dataset with high-level CCSD(T)/CBS reference energies (e.g., the S30L, L7, or HSG sets).

- Computational Setup: For each complex in the dataset, obtain the benchmark geometry.

- Systematic Calculation: Perform a single-point energy calculation for each complex and its monomers using a series of functionals (e.g., PBE, B3LYP, B3LYP-D3(BJ), ωB97X-D, DSD-BLYP). Use a consistent, medium-sized basis set (e.g., def2-TZVP) and apply CP correction.

- Error Analysis: Calculate the interaction energy for each functional. Compute the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) relative to the reference data for the entire set.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: DFT Functional Selection Workflow for NC Interactions

Diagram 2: Accuracy vs. Cost Trade-off in Functional Selection

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Modeling NC Interactions

| Item / Software | Category | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| ORCA | Quantum Chemistry Package | Highly efficient for wavefunction methods and double-hybrid DFT; excellent D3 correction implementation. |

| Gaussian / G16 | Quantum Chemistry Package | Industry standard with robust implementations of a wide range of functionals and basis sets. |

| PSI4 | Quantum Chemistry Package | Designed for accurate non-covalent interaction benchmarks; includes many modern density functionals. |

| def2 Basis Sets | Basis Set | A series of balanced Gaussian basis sets (SVP, TZVP, QZVP) for accurate results across the periodic table. |

| D3(BJ) Correction | Empirical Correction | Adds damped dispersion (van der Waals) corrections to DFT functionals; critical for binding energies. |

| Counterpoise (CP) | Error Correction | Eliminates Basis Set Superposition Error (BSSE) in interaction energy calculations. |

| GFN2-xTB | Semi-empirical Method | Provides surprisingly good geometry optimizations and rough energies for very large systems at low cost. |

| AutoDock Vina | Docking Software | Used for initial pose generation and high-throughput screening before costly QM refinement. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting DFT Functional Selection for Catalysis

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: My DFT-calculated activation barrier for a proton transfer reaction is 30% lower than the experimental value when using PBE. Which functional should I try for better accuracy without moving to high-cost coupled-cluster methods?

A: This is a common issue with GGA functionals like PBE, which often underestimate reaction barriers. For improved accuracy at a moderate computational cost, we recommend a hybrid-GGA functional.

- Primary Recommendation: Use the M06-2X meta-hybrid functional. It is parameterized for main-group thermochemistry, kinetics, and non-covalent interactions.

- Alternative: The ωB97X-D range-separated hybrid functional includes empirical dispersion and is excellent for barrier heights and diverse interaction types.

- Protocol: 1) Re-optimize the reactant, product, and transition state geometries with the new functional. 2) Perform a frequency calculation to confirm the transition state has one imaginary frequency. 3) Perform a more accurate single-point energy calculation on each geometry using a larger basis set (e.g., def2-TZVP) if resources allow. Compare the new barrier to your PBE result and literature values.

Q2: My transition state optimization for a catalytic C–C coupling step keeps failing or converges to a structure that doesn't look correct. What steps should I take?

A: Transition state optimization is sensitive to initial geometry and method.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Initial Guess: Ensure your initial guess is close to the suspected transition state. Use the reactant and product structures to interpolate an approximate geometry.

- Method Stability: Use a functional known for reliable transition state optimization, such as B3LYP or PBE0, with a moderate basis set (e.g., def2-SVP) for the initial optimization. M06-2X is also a strong candidate.

- Algorithm: Use a dedicated transition state search algorithm (e.g., Berny, QST2/3). Start from a structure where the forming/breaking bonds are constrained to lengths slightly longer/shorter than equilibrium.

- Verification: Always perform a frequency calculation on the optimized TS. A true TS has exactly one significant imaginary frequency (e.g., -500 to -1500 cm⁻¹). Visualize this vibrational mode to confirm it corresponds to the correct reaction coordinate.

- Protocol for Constrained Optimization: a) Build a guess structure. b) Freeze the key reaction coordinate bond distance(s). c) Optimize all other degrees of freedom. d) Release the constraint and perform a full transition state search.

Q3: How do I account for solvation effects in my organometallic catalytic cycle, and does the choice of functional interact with the solvation model?

A: Solvation is critical for solution-phase catalysis. The functional and solvation model must be chosen consistently.

- Recommendation: Use an implicit solvation model (e.g., SMD, CPCM) self-consistently during geometry optimization and energy evaluation.

- Functional Interaction: Hybrid or double-hybrid functionals paired with an implicit solvation model generally yield more accurate solvation energies. For organometallics, TPSSh (a hybrid meta-GGA) or PBE0 are good starting points. B3LYP is widely used but can have known issues for some organometallics.

- Protocol: 1) Select your functional (e.g., PBE0). 2) Choose the appropriate solvent in your SMD or CPCM model. 3) Optimize all structures (reactants, TS, intermediates, products) in the presence of the solvation model. 4) Ensure the electronic embedding is turned on for the optimization.

Q4: For screening potential drug molecules involving enzyme catalysis, I need a fast but reliable functional for comparing activation energies. What is the best compromise?

A: In high-throughput screening, cost-effective yet accurate methods are essential.

- Recommendation: The r²SCAN-3c composite method is excellent. It uses the robust r²SCAN meta-GGA functional with a specialized basis set and correction for dispersion and basis set incompleteness, offering "double-hybrid" quality at lower cost.

- Alternative: The B97-3c composite method is even faster and reliable for geometries and relative energies.

- Protocol for Screening: 1) Use a reliable semi-empirical or force-field method for initial pre-optimization. 2) Perform a final geometry optimization and frequency calculation with r²SCAN-3c. 3) Compare single-point energies (or Gibbs free energies) for the key transition states and intermediates across your candidate set.

Table 1: Performance of Selected DFT Functionals for Catalysis & Barrier Heights

| Functional Class | Example Functional | Typical Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for Barrier Heights (kcal/mol)* | Computational Cost (Relative to PBE) | Recommended For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GGA | PBE | 5.0 - 8.0 | 1.0 (Baseline) | Initial geometry scans, large systems. |

| Hybrid-GGA | PBE0, B3LYP | 3.0 - 4.5 | 3-5x | General organic/organometallic kinetics. |

| Meta-Hybrid-GGA | M06-2X | 2.5 - 3.5 | 8-12x | Main-group thermochemistry & kinetics, NCIs. |

| Range-Separated Hybrid | ωB97X-V, ωB97X-D | 2.0 - 3.0 | 10-15x | Charge-transfer, excitation, broad accuracy. |

| Double-Hybrid | DLPNO-CCSD(T) (not DFT, for reference) | < 1.0 | 100-1000x | Benchmark "gold standard" for small models. |

| Composite Method | r²SCAN-3c | ~2.5 | 2-4x | High-throughput screening, good geometries/energies. |

*Data synthesized from recent benchmarks (e.g., GMTKN55, BH76). MAE is system-dependent.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide: Functional Selection by Problem

| Computational Problem / Symptom | Likely Cause (Functional Issue) | Recommended Functional Switch |

|---|---|---|

| Underestimated reaction barrier | Lack of exact Hartree-Fock exchange (GGA limitation) | Switch from PBE to a hybrid (PBE0, B3LYP) or meta-hybrid (M06-2X). |

| Over-stabilization of charge-transfer states | Incorrect long-range exchange behavior | Switch to a range-separated hybrid (ωB97X-D, ωB97X-V). |

| Poor description of dispersion (stacking, van der Waals) in TS | Functional lacks dispersion correction | Add an empirical dispersion correction (e.g., -D3(BJ)) to your functional or switch to a functional with dispersion built-in (M06-2X, ωB97X-D). |

| Inaccurate spin-state ordering in transition metal catalysts | Self-interaction error, poor correlation | Use a hybrid meta-GGA (TPSSh) or range-separated hybrid (ωB97X-D) and validate against experimental data or high-level theory. |

| Calculations are too slow for system size | Functional too high-level for exploratory work | Use a fast composite method (B97-3c) or lower-tier hybrid for initial scans; step up later. |

Experimental & Computational Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Workflow for Computing a Catalytic Activation Barrier

- System Preparation: Build initial geometries of reactant complex and suspected product complex using molecular builder software. Ensure correct spin state and protonation state.

- Initial Optimization: Optimize reactant (R) and product (P) geometries using a cost-effective functional/basis set (e.g., PBE/def2-SVP). Perform frequency calculation to confirm minima (no imaginary frequencies).

- Transition State Search:

- Generate a plausible guess for the transition state (TS), often by modifying bond lengths/angles along the reaction coordinate.

- Use a hybrid functional (e.g., PBE0/def2-SVP) and a QST2 or Berny algorithm to optimize to a transition state.

- Crucially, perform a frequency calculation. A valid TS has exactly one imaginary frequency. Animate this frequency to verify it connects R and P.

- Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC): Perform an IRC calculation from the TS to confirm it connects to your R and P.

- High-Accuracy Single-Point Energy: Using the optimized geometries, perform a more accurate single-point energy calculation with a larger basis set (e.g., def2-TZVP) and a higher-level functional (e.g., ωB97X-D, DLPNO-CCSD(T) for benchmarking). Include implicit solvation if applicable.

- Thermochemical Analysis: Use frequency results (scaled vibrational frequencies) to calculate zero-point energy, thermal corrections, and Gibbs free energy at your desired temperature (e.g., 298.15 K).

Protocol 2: Functional Validation for a New Catalytic System

- Define a Test Set: Assemble 3-5 key experimental observables for a related, well-studied system (e.g., barrier heights, reaction energies, bond dissociation energies).

- Multi-Functional Benchmark: Calculate these observables using a hierarchy of functionals: a GGA (PBE), a hybrid (PBE0), a meta-hybrid (M06-2X), and a range-separated hybrid (ωB97X-D). Use consistent basis sets and solvation.

- Cost vs. Error Analysis: Plot computational cost versus deviation from experiment (or high-level theory). Select the functional that offers the best trade-off for your specific property (e.g., barrier height) for your larger, unknown system.

Visualization: Workflows & Relationships

Title: DFT Workflow for Catalytic Barrier Calculation

Title: Functional Selection: Cost vs. Accuracy Trade-Off

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Reaction Mechanism Studies

| Item / "Reagent" | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| DFT Software (Gaussian, ORCA, Q-Chem) | The core platform for performing electronic structure calculations, geometry optimizations, and frequency analyses. |

| Molecular Builder & Visualizer (Avogadro, GaussView, Chemcraft) | Used to build initial molecular geometries, visualize optimized structures, orbitals, and vibrational modes. |

| Basis Set Library (def2-SVP, def2-TZVP, cc-pVDZ) | Sets of mathematical functions describing electron orbitals. Crucial for accuracy; balance between completeness and cost. |

| Implicit Solvation Model (SMD, CPCM) | A computational model that approximates solvent as a continuous dielectric medium, essential for modeling solution-phase chemistry. |

| Empirical Dispersion Correction (D3(BJ), D3(0)) | An add-on correction to account for long-range van der Waals (dispersion) forces, often missing in standard DFT functionals. |

| Intrinsic Reaction Coordinate (IRC) Algorithm | A computational "path-following" tool that traces the minimum energy path from a transition state down to reactants and products. |

| Thermochemistry Analysis Script/Tool | Software routines that use frequency calculation outputs to compute Gibbs free energy, enthalpy, and entropy at specified temperatures. |

| High-Level Wavefunction Method (DLPNO-CCSD(T)) | A "gold standard" method used for benchmarking and obtaining highly accurate reference energies for small model systems. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Q1: My DFT geometry optimization for a large ligand (80+ atoms) fails to converge with a hybrid functional (e.g., B3LYP). What are the most cost-effective steps to resolve this?

A: This is often due to the increased complexity and computational demand of hybrid functionals on large systems. Implement this protocol:

- Initial Relaxation: First, perform a geometry optimization using a fast, low-rung GGA functional such as PBE or PBEsol with a moderate basis set (e.g., def2-SVP) and loose convergence criteria (e.g.,

Opt=(Loose,MaxCycles=200)in Gaussian). This provides a reasonable starting structure. - Refinement: Use this pre-optimized structure as the input for a single-point energy calculation with your target hybrid functional (e.g., B3LYP) and a larger basis set (e.g., def2-TZVP). For final accuracy, a subsequent optimization with the hybrid functional can be attempted, but the single-point approach on a GGA-optimized structure often provides an excellent cost/accuracy balance for screening.

Q2: When screening transition metal complexes, my selected functional (PBE) gives unrealistic bond lengths compared to experiment. Which functional should I switch to without increasing CPU time tenfold?

A: GGA functionals like PBE often fail for metals due to self-interaction error. Instead, use a meta-GGA functional like SCAN or r²SCAN, which include kinetic energy density and provide much better accuracy for organometallic systems at only a modest (~20-50%) increase in cost over PBE. For systematic screening, implement a tiered protocol:

- Tier 1 (Initial Filter): Use r²SCAN/def2-SVP for geometry optimization and preliminary scoring.

- Tier 2 (Validation): Re-score top hits (<5% of library) with a hybrid functional like TPSSH or B3LYP-D3(BJ) and a larger basis set via single-point calculation.

Q3: My high-throughput workflow is bottlenecked by frequency calculations for thermal corrections. Can I safely skip them for relative ranking of similar molecules?

A: For ranking similar congeneric series (e.g., drug-like molecules with the same core), the vibrational contributions to free energy often cancel out. You can perform a validation study:

- Select a representative subset (50-100 compounds) from your library.

- Calculate full Gibbs free energies (G) and compare rankings using only electronic energies (E).

- If the Spearman rank correlation coefficient (ρ) is >0.98, you can justify using electronic energies only for the full screen. Document this validation in your thesis methods.

Q4: How do I choose between wavefunction-based (DLPNO-CCSD(T)) and density-based (DFT) methods for post-screening validation of my top 100 hits?

A: The choice hinges on system size and the nature of interactions. Follow this decision tree:

Diagram 1: Method Selection for Post-Screening Validation (100 chars)

Functional Performance & Computational Cost Data

The selection of a Density Functional Theory (DFT) functional is a direct trade-off between accuracy and computational expense, a core thesis of cost-effective high-throughput screening. Below is quantitative data for common functionals in drug-like molecule screening.

Table 1: Benchmark of DFT Functionals for Organic/Bio-Molecule Properties

| Functional Type | Example Functional | Relative Speed (vs. PBE) | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for Thermochemistry (kcal/mol)* | Recommended Use Case in HTVS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GGA | PBE, PBEsol | 1.0 (Reference) | ~5 - 8 | Initial geometry optimization, very large libraries (>1M cmpds) |

| Meta-GGA | SCAN, r²SCAN | 1.2 - 1.5 | ~2 - 3 | Excellent balance. Primary screening for diverse libraries. |

| Hybrid GGA | B3LYP, PBE0 | 3 - 5 | ~2 - 4 | Final scoring of top hits (<1% of library), small molecules |

| Hybrid Meta-GGA | ωB97M-V, M06-2X | 5 - 8 | ~1 - 2 | High-accuracy validation, non-covalent interaction energies |

| Double-Hybrid | B2PLYP-D3 | 10 - 15 | < 1.5 | Ultimate benchmark for subsets (<100 cmpds), requires MP2 |

*Data sourced from benchmarks like GMTKN55 and Minnesota Databases. MAE is illustrative; actual error depends on property.*

Table 2: Recommended Tiered Screening Protocol for 1M+ Compound Library

| Tier | Purpose | % of Library | Functional & Basis Set | Typical Compute Time per Molecule | Goal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 - Ultra-Fast Filter | 3D Conformer Generation & Rough Scoring | 100% | GFN2-xTB (Semi-empirical) | < 1 CPU-min | Reduce library by 80-90% |

| 2 - Primary DFT Screen | Accurate Geometry & Scoring | 10-20% | r²SCAN-D3/def2-SVP | 10-30 CPU-hrs | Identify top 0.5% candidates |

| 3 - Refinement | High-Accuracy Ranking | 0.5% | ωB97M-V/def2-TZVP (Single Point) | 20-50 CPU-hrs | Final ranked list for assay |

Experimental Protocol: Tiered DFT Screening Workflow

Objective: To identify the top 50 potential inhibitors from a 500,000-compound library targeting a specific enzyme active site.

Diagram 2: Tiered HTVS Workflow for Large Library (99 chars)

Detailed Protocol Steps:

Tier 1 - Semi-Empirical Pre-Filter:

- Software: Use

xtbfor GFN2-xTB calculations. - Input: 3D SDF file of all pre-processed ligands.

- Command:

xtb input.sdf --gfn 2 --opt loose --parallel 8 > output.log - Analysis: Extract GFN2-xTB energy. Rank compounds and select the lowest 10% (50,000 compounds) for Tier 2.

Tier 2 - DFT Primary Screen:

- Software: ORCA (v5.0 or later) recommended for efficiency.

- Functional/Basis:

r2SCAN-3ccomposite method orr²SCAN-D3(BJ)/def2-SVP. - Input File Template (

tier2.inp): - Execution: Run in a high-throughput job array. Collect optimized geometries and final single-point energies.

- Analysis: Rank by DFT energy. Select top 0.5% (2,500 compounds).

Tier 3 - Hybrid Refinement:

- Software: ORCA or Gaussian.

- Method: Perform a single-point calculation on the r²SCAN-optimized geometries.

- Input File Template (

tier3.inp): - Analysis: The final ranking for experimental validation is based on the ωB97M-V/def2-TZVP electronic energy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools & Materials for HTVS

| Item/Software | Function in HTVS Protocol | Key Consideration for Cost-Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|

xtb (CREST) |

Ultra-fast semi-empirical quantum chemistry for conformational sampling and Tier 1 pre-screening. | Free, open-source. Dramatically reduces workload for expensive DFT steps. |

| ORCA | DFT software package. Excellent for high-throughput due to robust automation and good parallel scaling. | Free for academic use. Lower operational cost than many commercial alternatives. |

def2 Basis Sets |

A family of balanced, increasingly sized basis sets (SVP, TZVP, QZVP) for systematic method improvement. | Using a smaller def2-SVP for optimization saves time; accuracy is recovered in larger basis set single-point. |

| D3(BJ) Correction | An empirical dispersion correction added to the functional (e.g., B3LYP-D3(BJ)). | Negligible computational cost. Essential for any non-covalent interaction (drug binding) screening. |

| Job Array Scheduler (e.g., SLURM, PBS) | Manages thousands of individual DFT calculations on an HPC cluster. | Efficient scheduling and queue management is critical to complete large screens in a practical timeframe. |

| Cheminformatics Toolkit (RDKit) | Prepares ligand libraries (tautomer generation, protonation, filtering) and analyzes results. | Open-source. Automates pre- and post-processing, saving researcher time and ensuring reproducibility. |

Diagnosing DFT Failures and Optimizing Workflows for Efficiency and Reliability

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My calculated band gaps for semiconductors are consistently smaller than experimental values. Which error is likely responsible, and how can I correct it?

A: This is a classic symptom of Delocalization Error, inherent in many standard semi-local functionals (e.g., LDA, GGA). The error causes excessive electron delocalization, underestimating band gaps and reaction barriers.

- Correction Protocol: Use a hybrid functional (e.g., B3LYP, PBE0) mixing a portion of exact Hartree-Fock (HF) exchange. For severe cases (e.g., strongly correlated systems), consider DFT+U or advanced functionals like SCAN or r²SCAN.

- Workflow: Perform a convergence test with increasing HF exchange percentage (e.g., 0% to 25% in PBE0) and compare to known benchmark data.

Q2: My DFT calculation predicts a spurious fractional electron transfer between dissociated fragments, or fails to describe dissociation correctly (e.g., H₂⁺). What is happening?

A: This indicates Self-Interaction Error (SIE), where an electron incorrectly interacts with itself. This is severe in LDA/GGA and leads to unrealistic charge stabilization.

- Correction Protocol: Implement a functional with exact exchange. Global hybrids (like PBE0) reduce SIE. For complete elimination in single-electron systems, use Hartree-Fock or a range-separated hybrid (e.g., HSE, CAM-B3LYP).

- Experimental Check: Calculate the dissociation curve of H₂⁺. A functional with large SIE will not yield the correct flat, energy-conserving curve at large distances.

Q3: My open-shell (radical) calculation shows high spin contamination (

A: Yes, significant Spin Contamination means your wavefunction is contaminated by higher spin states, making energies and properties unreliable.

- Correction Protocol:

- Check & Diagnose: Always output the expectation value of the

- Switch Functional: Pure GGA functionals (e.g., PBE) often have less contamination than older hybrids (e.g., B3LYP). Consider using modern, minimally contaminated hybrids like PBE0.

- Advanced Method: If contamination remains high, use a broken-symmetry approach for biradicals or switch to a wavefunction method like CCSD(T) for critical results.

- Check & Diagnose: Always output the expectation value of the

Q4: How do I systematically choose a functional to balance accuracy and computational cost for my transition metal catalyst study?

A: Follow this decision protocol, framed within the accuracy vs. cost thesis:

- Define Property: Identify the key property (reaction energy, barrier, spin state ordering, electronic spectrum).

- Initial Screen: Use a fast GGA (e.g., PBE) with a moderate basis set for geometry optimization.

- Accuracy Refinement: On optimized geometries, perform single-point energy calculations with a hierarchy of functionals of increasing cost and accuracy (see Table 1).

- Benchmark: Use known experimental or high-level ab initio data for a similar system to validate your functional choice.

Table 1: Functional Hierarchy for Accuracy vs. Cost Trade-off

| Functional Class | Example | Typical SIE | Delocalization Error | Spin Contamination | Relative Cost (vs. PBE) | Best for Property |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GGA | PBE, RPBE | High | High | Low-Moderate | 1.0 | Structures, phonons, initial screening |

| Meta-GGA | SCAN, r²SCAN | Moderate | Reduced | Low-Moderate | ~1.5-2.0 | Structures, cohesive energies |

| Global Hybrid | PBE0, B3LYP | Reduced | Reduced | Can be High (B3LYP) | ~3-10 | Band gaps, reaction energies |

| Range-Separated Hybrid | HSE06, CAM-B3LYP | Reduced | Improved for charge transfer | Moderate | ~5-15 | Optical spectra, charge transfer |

| Double Hybrid | B2PLYP, DSD-PBEP86 | Low | Low | Low | ~50-100+ | Highly accurate thermochemistry |

Table 2: Diagnostic Values for Spin Contamination in Common Radicals

| System | Ideal | Typical | Typical | Acceptable Tolerance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methyl Radical (CH₃•) | 0.750 | 0.751 - 0.755 | 0.760 - 0.780 | ±0.02 |

| Phenyl Radical (C₆H₅•) | 0.750 | 0.752 - 0.760 | 0.78 - 0.85 | ±0.02 |

| Iron-Oxo Porphyrin (Compound I) | 2.000 (Quintet) | 2.02 - 2.05 | 2.10 - 2.30 | ±0.05 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Diagnosing Delocalization Error via Band Gap Calculation

- System: Obtain a crystal structure (e.g., silicon, TiO₂ anatase).

- Software: Use a plane-wave code (e.g., VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO) or Gaussian basis set code.

- Calculation Steps:

- Optimize geometry with PBE functional.

- Perform single-point PBE calculation on optimized structure to get band gap (E_g^PBE).

- Perform single-point calculation with HSE06 hybrid functional on the same structure.

- Compare Eg^PBE and Eg^HSE06 to the experimental band gap.

- Expected Result: Eg^PBE << Eg^HSE06 ≈ Experimental value.

Protocol 2: Quantifying Spin Contamination

- System: An open-shell molecule (e.g., NO₂).

- Software: Use Gaussian, ORCA, or NWChem.

- Calculation Steps:

- Perform an unrestricted calculation (UKS) using the PBE0/def2-TZVP level of theory.

- In the output, locate the expectation value of the total spin operator

<S²>. - Compute the ideal value: S*(S+1), where S is the total spin quantum number (e.g., for doublet, S=1/2, ideal

- Calculate deviation: Δ

Diagrams

Title: Workflow for Correcting DFT Delocalization Error

Title: Spin Contamination Diagnosis and Mitigation Path

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for DFT Error Analysis

| Item/Software | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Quantum ESPRESSO | Open-source plane-wave DFT code. Ideal for periodic systems (solids, surfaces) to diagnose band gap errors. |

| Gaussian/ORCA | Leading quantum chemistry packages. Essential for molecular calculations, detailed wavefunction analysis, and <S²> diagnostics. |

| LibXC | Library of hundreds of exchange-correlation functionals. Allows systematic testing of different functionals against errors. |

| VASPKIT/ase | Post-processing toolkits. Automate extraction and analysis of band structures, densities, and convergence data. |

| Materials Project/CCCBDB | Online databases of computed and experimental properties. Critical for benchmarking and identifying systemic functional errors. |

| DFT+U Pseudopotentials | Pseudopotentials with Hubbard U parameter. Correct for excessive electron delocalization in transition metal oxides. |

| Def2 Basis Sets (SVP, TZVP, QZVP) | High-quality Gaussian-type orbital basis sets. Ensure results are not artifacts of a poor basis set. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My DFT calculation on a mid-sized organic molecule (≈50 atoms) is taking an extremely long time and exhausting memory. What basis set-related issue is most likely, and how can I resolve it? A: The issue is likely the use of a basis set with high angular momentum functions (e.g., 6-311++G(3df,3pd)) or a very large plane-wave cutoff. For geometry optimizations of such systems, start with a moderate Pople-style basis (e.g., 6-31G) or a DZP-quality basis. Use this optimized geometry for a subsequent *single-point energy calculation with the larger, target basis set. This "optimize-then-refine" protocol balances cost and accuracy effectively.

Q2: I observe significant basis set superposition error (BSSE) in my computed intermolecular binding energies. How can I correct for this within a typical workflow? A: BSSE is common when using finite basis sets. The standard correction is the Counterpoise (CP) method. For a dimer A-B, perform three calculations with the full dimer basis set: 1) on the dimer in its geometry, 2) on monomer A with its own basis plus the ghost orbitals of B, and 3) on monomer B with its own basis plus the ghost orbitals of A. The CP-corrected binding energy is: Ebind(CP) = EAB - [EA(B) + EB(A)].

Q3: For transition metal complexes, my chosen functional (e.g., B3LYP) yields inaccurate spin state energies. Could the basis set be a factor? A: Absolutely. Transition metals require basis sets with sufficient flexibility for electron correlation (crucial for correct spin states). Using a double-zeta basis for the metal is often inadequate. Switch to a triple-zeta basis for the metal (e.g., def2-TZVP) and ensure it includes diffuse functions if dealing with anionic species or charge transfer. Always use the associated effective core potential (ECP) for metals beyond the 3rd row to account for relativistic effects.

Q4: When modeling non-covalent interactions (e.g., π-stacking in a drug candidate), my results are poor. What basis set feature is critical? A: You must include diffuse functions. These are essential for modeling the weak, long-range electron density overlaps in dispersion forces. Use basis sets denoted with "+" (for heavy atoms) or "++" (for heavy atoms and hydrogens), such as aug-cc-pVDZ or 6-311++G. Note that this significantly increases computational cost.

Q5: How do I systematically converge results with respect to basis set size for a high-accuracy project? A: Perform a basis set convergence study. Run your key calculation (e.g., single-point energy) on a fixed geometry using a sequence of basis sets of increasing size (e.g., cc-pVDZ → cc-pVTZ → cc-pVQZ). Plot the target property (energy, reaction enthalpy) against the basis set level. The point where the property change becomes negligible relative to your accuracy threshold defines your adequate basis set.

Table 1: Relative Computational Cost & Accuracy of Common Gaussian-Type Basis Sets

| Basis Set | Typical Use Case | Relative CPU Time* | Key Features/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3-21G | Initial scans, very large systems | 1.0 (Baseline) | Minimal, fast; poor accuracy. |

| 6-31G* (DZP) | Geometry optimization, medium accuracy | ~8x | Polarization on heavy atoms; good cost/accuracy. |

| 6-311++G | NCIs, anions, final single-point energies | ~50x | Triple-zeta, diffuse & polarization on all atoms. |

| cc-pVDZ | Correlated methods (MP2, CCSD), general purpose | ~10x | Double-zeta; part of correlation-consistent family. |

| cc-pVTZ | High-accuracy benchmarks | ~100x | Triple-zeta; much improved accuracy over DZ. |

| def2-SVP | Geometry optimizations for organometallics | ~12x | Good balance for transition metals. |

| def2-TZVP | Final energies for transition metal systems | ~80x | Recommended for metal spin-state energetics. |

*Estimated for a typical organic molecule; time scales super-linearly with atom count.

Table 2: Recommended Basis Set Protocols for Different Research Goals

| Research Goal | Recommended Protocol | Expected Error Reduction vs. Minimal Basis |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Geometry Optimization | 6-31G* / def2-SVP | High (Most geometry error removed) |