Automated Feature Selection for Material Properties: Advanced Methods and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of automated feature selection techniques specifically tailored for predicting material properties, with a focus on applications in biomedical and clinical research.

Automated Feature Selection for Material Properties: Advanced Methods and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of automated feature selection techniques specifically tailored for predicting material properties, with a focus on applications in biomedical and clinical research. It explores the foundational principles driving the shift from traditional manual feature engineering to sophisticated, data-driven algorithms. The content details cutting-edge methodologies, including reinforcement learning, differentiable information imbalance, and causal model-inspired selection, highlighting their implementation in real-world material discovery and drug development pipelines. Practical guidance on overcoming common challenges like data scarcity and feature redundancy is provided, alongside a rigorous comparison of technique performance on limited datasets. This resource is designed to equip researchers and scientists with the knowledge to enhance the accuracy, efficiency, and interpretability of their material property prediction models.

Why Automation is Revolutionizing Feature Selection in Materials Science

The Critical Role of Feature Selection in Predicting Material Properties

In the data-driven landscape of modern materials science, feature selection has emerged as a critical preprocessing step that directly influences the accuracy, efficiency, and interpretability of predictive models. The proliferation of high-dimensional data from experiments and simulations has created a pressing need to identify the most relevant material descriptors while eliminating redundant or irrelevant features. This application note examines the pivotal role of automated feature selection within materials research, providing structured protocols and quantitative benchmarks to guide researchers in developing more robust property prediction models. By integrating domain knowledge with advanced algorithms, feature selection transforms raw computational data into actionable scientific insights, accelerating the discovery of next-generation functional materials.

The Feature Selection Challenge in Materials Science

Materials science inherently grapples with the "curse of dimensionality", where the number of potential features often vastly exceeds the number of available samples [1]. This challenge is particularly acute in research areas such as alloy development, battery materials, and catalyst design, where comprehensive datasets may contain hundreds of compositional, processing, and microstructural descriptors. Without effective feature selection, models suffer from overfitting, diminished generalization capability, and reduced physical interpretability [2] [1].

The limitations of purely data-driven approaches have prompted the development of hybrid methods that embed materials domain knowledge directly into the feature selection process. This integration ensures that selected features align with established physical principles while maintaining the computational advantages of machine learning-driven discovery [2].

Feature Selection Methodologies: A Comparative Analysis

Method Categories and Characteristics

Feature selection methods can be categorized into three primary approaches, each with distinct advantages for materials informatics applications.

Table 1: Categories of Feature Selection Methods in Materials Science

| Method Type | Key Characteristics | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Methods (Fisher Score, Mutual Information) | Selects features based on statistical measures | Computational efficiency, model-agnostic | Ignores feature dependencies, may select redundant features |

| Wrapper Methods (Sequential Feature Selection, Recursive Feature Elimination) | Uses model performance to evaluate feature subsets | Considers feature interactions, often higher accuracy | Computationally intensive, risk of overfitting |

| Embedded Methods (LASSO, Random Forest Importance, TreeShap) | Incorporates feature selection within model training | Balanced approach, computational efficiency | Model-specific, may require customization |

Domain-Knowledge Integrated Approaches

Recent advancements have introduced methods that explicitly incorporate materials domain knowledge to address the limitations of purely data-driven approaches. The NCOR-FS method identifies highly correlated features through both data-driven analysis and domain expertise, then applies Non-Co-Occurrence Rules to eliminate redundant descriptors [2]. This hybrid approach has demonstrated superior performance in selecting feature subsets that improve both prediction accuracy and model interpretability across multiple materials systems [2].

Quantitative Benchmarking of Feature Selection Techniques

Performance Evaluation on Synthetic Datasets

Rigorous benchmarking on synthetic datasets with known ground truth provides critical insights into the capabilities and limitations of various feature selection methods. Recent studies have systematically evaluated multiple approaches on carefully designed datasets containing non-linear relationships and irrelevant features [1].

Table 2: Performance Benchmark of Feature Selection Methods on Non-Linear Datasets

| Method | RING Dataset (Accuracy) | XOR Dataset (Accuracy) | RING+XOR Dataset (Accuracy) | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forests | High | High | High | Medium |

| TreeShap | High | High | High | Medium |

| mRMR | High | Medium | High | High |

| LassoNet | Medium | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| DeepPINK | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| CancelOut | Low | Low | Low | Low |

The benchmark results reveal that tree-based methods consistently outperform deep learning-based feature selection approaches, particularly when detecting non-linear relationships between features [1]. This finding is significant for materials scientists working with complex, non-linearly separable material properties where traditional linear methods may be insufficient.

Real-World Application Performance

In industrial applications, embedded feature selection methods have demonstrated remarkable effectiveness. A recent study on fault classification in mechanical systems achieved an average F1-score of 98.40% using only 10 selected features from time-domain sensor data [3]. This performance highlights how strategic feature reduction can enhance model precision while significantly decreasing computational complexity in practical materials diagnostics.

Experimental Protocols for Feature Selection in Materials Research

Protocol 1: NCOR-FS Method for Domain-Knowledge Integration

Purpose: To select feature subsets that minimize redundancy while incorporating materials domain knowledge.

Materials/Software Requirements:

- MatSci-ML Studio or similar materials informatics platform [4]

- Dataset with compositional, processing, and property descriptors

- Domain knowledge references (phase diagrams, structure-property relationships)

Procedure:

- Data Preparation and Feature Identification

- Compile comprehensive dataset with all potential descriptors

- Document domain knowledge regarding known correlations between features

Acquisition of Highly Correlated Features

- Apply data-driven correlation analysis (Pearson/Spearman correlation)

- Simultaneously identify correlated feature pairs based on domain knowledge

- Merge results to create comprehensive set of correlated feature groups

Definition of Non-Co-Occurrence Rules

- Formulate rules prohibiting simultaneous selection of features within correlated groups

- Quantify NCOR violation degree for candidate feature subsets

Optimization-Based Feature Selection

- Implement Multi-objective Particle Swarm Optimization algorithm

- Evaluate feature subsets based on prediction accuracy and NCOR violation degree

- Select optimal feature subset that balances performance and interpretability

Validation:

- Compare selected features against known structure-property relationships

- Verify model performance on holdout validation set

- Assess physical plausibility of selected feature subset

Protocol 2: Automated Multi-Strategy Feature Selection

Purpose: To implement a comprehensive feature selection workflow combining multiple strategies for robust descriptor identification.

Materials/Software Requirements:

- MatSci-ML Studio with hyperparameter optimization capabilities [4]

- Computational resources for cross-validation and model training

Procedure:

- Initial Data Assessment

- Perform data quality evaluation (completeness, uniqueness, validity)

- Handle missing values using appropriate imputation strategies

Multi-Stage Feature Selection

- Importance-Based Filtering: Use model-intrinsic metrics for initial feature filtering

- Wrapper Method Application: Implement Recursive Feature Elimination with cross-validation

- Advanced Optimization: Apply Genetic Algorithms for feature subset exploration

Model Training with Selected Features

- Utilize broad model library (Scikit-learn, XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost)

- Perform automated hyperparameter optimization using Bayesian methods

- Validate model performance with k-fold cross-validation

Interpretability Analysis

- Apply SHapley Additive exPlanations for model interpretation

- Evaluate feature importance rankings across multiple models

- Assess consistency with materials science principles

Validation:

- Compare performance metrics across different feature subsets

- Evaluate stability of selected features through bootstrap sampling

- Verify generalization capability on external test datasets

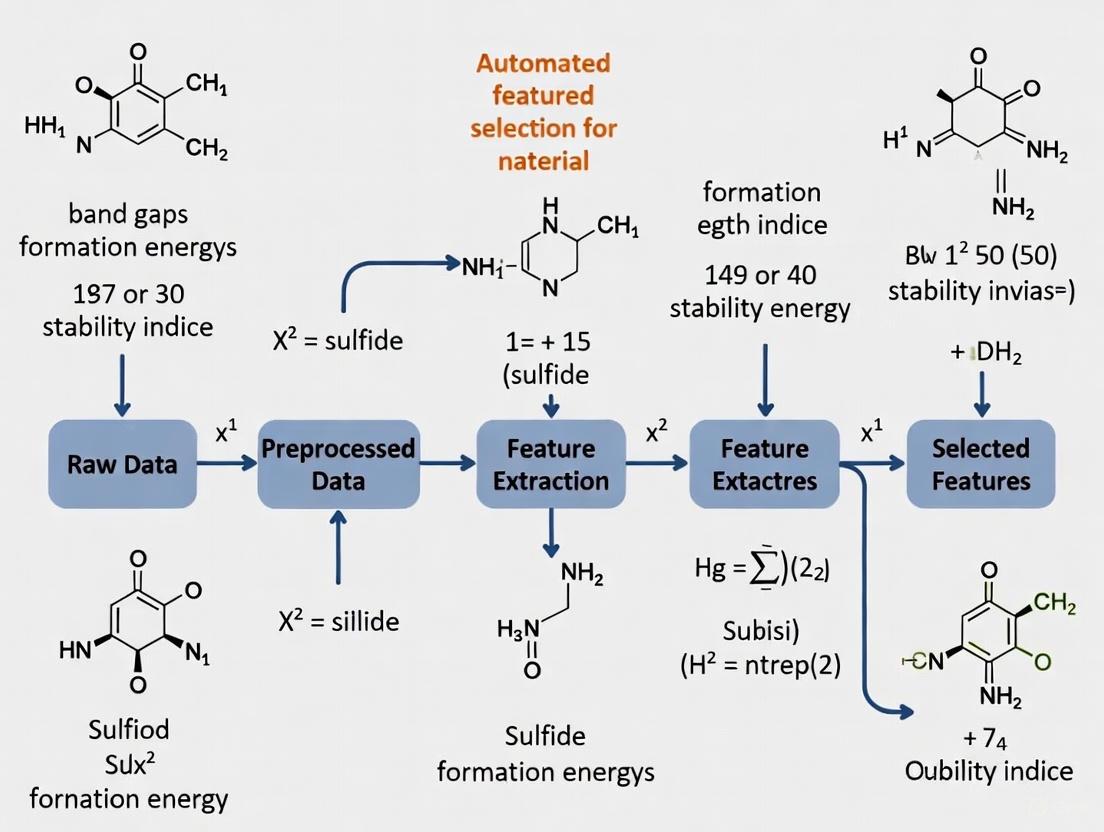

Visualization of Feature Selection Workflows

NCOR-FS Methodology Workflow

Automated Materials Informatics Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Automated Feature Selection in Materials Science

| Tool/Platform | Type | Key Functionality | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| MatSci-ML Studio | GUI-based Workflow Toolkit | End-to-end ML pipeline with automated feature selection | Accessible platform for domain experts with limited coding experience [4] |

| AutoGluon/TPOT | Automated ML Framework | Automated model selection and hyperparameter tuning | High-throughput screening of material candidates [5] |

| NCOR-FS Algorithm | Domain-Knowledge Embedded Method | Feature selection with non-co-occurrence rules | Scenarios requiring alignment with materials domain knowledge [2] |

| Random Forest/TreeShap | Ensemble Method with Interpretation | Feature importance ranking with non-linear capability | Complex datasets with interactive effects between features [1] |

| LassoNet | Deep Learning Approach | Neural network with L1-regularization for feature selection | High-dimensional datasets with potential non-linear relationships [1] |

| Optuna | Hyperparameter Optimization | Bayesian optimization for model tuning | Fine-tuning predictive models with selected feature subsets [4] |

Feature selection represents a cornerstone of modern materials informatics, enabling researchers to extract meaningful patterns from complex, high-dimensional datasets. By implementing the protocols and methodologies outlined in this application note, materials scientists can significantly enhance the predictive accuracy, computational efficiency, and scientific interpretability of their data-driven models. The integration of domain knowledge with automated feature selection algorithms, as demonstrated by approaches like NCOR-FS, provides a powerful framework for addressing the unique challenges of materials property prediction.

Future advancements in feature selection will likely focus on improved handling of non-linear relationships, more sophisticated integration of multi-scale materials data, and enhanced interpretability for scientific discovery. As autonomous experimentation and high-throughput computing continue to transform materials research [5] [6], robust feature selection methodologies will play an increasingly critical role in accelerating the discovery and development of next-generation functional materials.

In the pursuit of discovering and optimizing new materials, researchers face a triad of fundamental limitations that constrain the pace and scope of innovation. Traditional experimental approaches are often characterized by intensive manual labor, prohibitively high computational costs, and problem formulations that belong to the class of NP-hard challenges [7]. These bottlenecks are particularly pronounced in the phase of feature selection, where scientists must identify the most relevant descriptors from a vast and complex feature space to predict material properties accurately. The manual curation of datasets, execution of experiments, and analysis of results constitute a significant time investment, often requiring months or even years for a single material development cycle [4]. Furthermore, the computational models used to navigate this complexity often involve solving problems that are NP-hard, meaning that the time required to find an optimal solution grows exponentially with the problem size, making exhaustive search infeasible for all but the simplest of cases [7]. This article details these limitations within the context of automated feature selection for material properties research and provides structured protocols to navigate this complex landscape.

Quantitative Analysis of Traditional vs. Automated Workflows

The inefficiencies of traditional methodologies become starkly evident when their resource demands are quantified. The transition to automated workflows, particularly those incorporating sophisticated feature selection, fundamentally alters this resource profile.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Workflow Efficiency in Materials Research

| Aspect | Traditional Workflow | Automated Feature Selection Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Cycle Time | Months to years [4] | Days to weeks [4] |

| Primary Labor Input | High (manual data curation, trial-and-error) [4] | Low (algorithm-driven, high-throughput) [4] |

| Computational Cost Nature | High cost for single, rigid simulations | Focused cost on hyperparameter optimization and model interpretation [4] |

| Problem Complexity Class | Often NP-hard; requires heuristic shortcuts [7] | Managed via multi-strategy algorithms (e.g., RFE, Genetic Algorithms) [4] |

| Feature Selection Paradigm | Manual, based on domain intuition | Automated, multi-stage (importance-based filtering, wrapper methods) [4] |

| Resulting Model Accuracy (R²) | Lower (e.g., ~0.84 for Random Forest on a representative dataset) [4] | Higher (e.g., ~0.94 for AdaBoost with feature engineering on a representative dataset) [4] |

Table 2: Breakdown of NP-hard Problem Characteristics in Materials Informatics

| Characteristic | Description | Impact on Materials Research |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | A problem is NP-hard if it is at least as hard as the hardest problems in NP; no known polynomial-time solution exists [7]. | General, efficient algorithms for finding optimal material compositions are unlikely to exist. |

| Exponential Time Growth | Solution time grows exponentially with input size (e.g., number of features or elements in an alloy) [7]. | Searching the entire composition-property-property space for complex alloys becomes computationally intractable. |

| Practical Consequence | Forces a shift from seeking perfect, universal solutions to finding specialized, satisficing strategies [7]. | Researchers must use heuristics, approximations, and clever optimizations to make progress. |

| Verifiability | A proposed solution can be verified quickly (polynomial time), even if finding it is hard [7]. | A model's prediction for an optimal material composition can be checked with a simulation or experiment. |

Experimental Protocols for Automated Feature Selection

Protocol 1: Multi-Stage Feature Selection for Composition-Property Mapping

This protocol is designed for a classic materials science problem: predicting a target property (e.g., ultimate tensile strength) from a material's composition and processing history.

1. Data Ingestion and Quality Assessment

- Action: Load structured, tabular data (e.g., in CSV format) containing compositional and processing parameters as features and the target property as the output variable [4].

- Tools: Utilize data management modules in platforms like MatSci-ML Studio for initial statistical summary [4].

- Deliverable: A report on data dimensions, data types, and missing value counts.

2. Intelligent Data Preprocessing

- Action: Employ an intelligent data quality analyzer to generate a data quality score and a prioritized list of remediation actions [4].

- Methods:

- Best Practice: Leverage a StateManager with undo/redo functionality to experiment with different cleaning strategies without risk [4].

3. Multi-Strategy Feature Selection

- Action: Systematically reduce the feature space to the most relevant descriptors.

- Stage 1 (Importance-based Filtering): Use model-intrinsic metrics (e.g.,

.feature_importances_from a Random Forest model) for rapid, initial feature filtering [4]. - Stage 2 (Wrapper Methods): Apply advanced search algorithms, such as Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) or Genetic Algorithms (GA), which evaluate feature subsets based on actual model performance [4].

- Stage 1 (Importance-based Filtering): Use model-intrinsic metrics (e.g.,

- Output: A refined set of high-impact features for model training.

4. Model Training with Automated Hyperparameter Optimization

- Action: Train predictive models using a library of algorithms (e.g., XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost) [4].

- Optimization: Automate hyperparameter tuning using Bayesian optimization frameworks like Optuna to identify high-performance model configurations efficiently [4].

- Validation: Use k-fold cross-validation to ensure model robustness.

5. Model Interpretation and Validation

- Action: Employ SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis to interpret model predictions and validate that the selected features align with domain knowledge [4].

- Final Step: Conduct experimental validation of the model's top predictions to confirm real-world performance [4].

Protocol 2: Inverse Design via Multi-Objective Optimization

This protocol addresses the "inverse" problem: finding a material composition that meets a set of desired target properties, an inherently NP-hard challenge.

1. Problem Formulation

- Action: Define the inverse design task as a multi-objective optimization problem.

- Input: A set of target property values (e.g., Tensile Strength ≥ X, Electrical Conductivity ≥ Y).

- Constraints: Specify any boundaries for compositional elements (e.g., 0 < Si < 15 wt%).

2. Search Space Exploration

- Action: Use a multi-objective optimization engine to explore the complex design space [4].

- Methods: Algorithms such as genetic algorithms are well-suited for this, as they can efficiently navigate high-dimensional, non-linear spaces to find a Pareto front of non-dominated solutions.

3. Candidate Selection and Verification

- Action: From the Pareto-optimal set, select one or more candidate compositions for further analysis.

- Verification: Run the candidates through the forward predictive model (from Protocol 1) to ensure they meet the target properties. The best candidates are then recommended for synthesis and testing.

Inverse Design Workflow: This diagram outlines the protocol for finding material compositions that meet multiple target properties.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details the essential digital "reagents" and tools required to implement the protocols described above.

Table 3: Essential Toolkit for Automated Feature Selection in Materials Science

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Role in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Structured Tabular Dataset | The foundational input data containing composition, processing parameters, and measured properties [4]. | Serves as the raw material for building predictive models. |

| Automated ML Platform (e.g., MatSci-ML Studio) | An integrated, GUI-driven software toolkit that encapsulates the end-to-end ML workflow [4]. | Lowers the technical barrier for domain experts, enabling code-free data preprocessing, feature selection, and model training. |

| Data Preprocessing Algorithms (e.g., KNNImputer, Isolation Forest) | Algorithms designed to handle missing data and detect outliers in the dataset [4]. | Acts as a "cleaning agent" to ensure data quality and robustness before model training. |

| Feature Selection Algorithms (e.g., RFE, Genetic Algorithms) | Multi-strategy algorithms for systematically reducing the dimensionality of the feature space [4]. | Functions as a "molecular sieve" to isolate the most impactful descriptors from a complex mixture of features. |

| Hyperparameter Optimization Library (e.g., Optuna) | A framework that uses Bayesian optimization to efficiently find the best model parameters [4]. | Serves as a "precision tuner" for machine learning models, maximizing predictive performance. |

| Interpretability Module (e.g., SHAP) | A module for explaining the output of machine learning models [4]. | Acts as an "analytical probe" to validate model decisions and gain mechanistic insights, building trust in the AI. |

Automated Feature Selection Workflow: This diagram visualizes the logical sequence of applying the digital tools in the Scientist's Toolkit.

The field of materials informatics applies data-centric approaches, including machine learning, to advance materials science research and development. This methodology is transforming traditional R&D processes by enabling the inverse design of materials—where desired properties dictate the composition—rather than relying solely on the forward process of discovering properties from existing materials. The core challenge in this domain stems from the inherent nature of experimental data, which is often sparse, high-dimensional, biased, and noisy [8]. This data landscape makes automated feature selection not merely beneficial but essential for accelerating discovery.

Feature selection (FS) is critically important for four primary reasons: it reduces model complexity by minimizing the number of parameters, decreases training time, enhances the generalization capabilities of models by reducing overfitting, and helps avoid the curse of dimensionality [9]. In high-dimensional proteomics data, for instance, a only small fraction of detected proteins are biologically relevant to specific pathologies, while the majority represent technical noise or non-causal correlations [10]. Automated feature selection methods address this by precisely identifying the most discriminative features from these vast datasets.

The adoption of these automated, data-centric approaches is accelerating due to three key drivers: significant improvements in AI-driven solutions leveraged from other sectors, the development of robust data infrastructures (including open-access repositories and cloud-based research platforms), and a growing awareness and educational push around the necessity of these tools to maintain competitive innovation pace [8].

Core Drivers and Quantitative Benchmarks

Key Drivers for Automation

The transition toward automated feature selection and analysis in materials and drug discovery is underpinned by several compelling strategic advantages. Research by IDTechEx has identified three repeated benefits of employing advanced machine learning techniques in the R&D process: enhanced screening of candidates and research areas, reducing the number of experiments required to develop a new material (thereby shortening time to market), and discovering new materials or relationships that might otherwise remain hidden [8].

Furthermore, the economic imperative is clear. According to Morgan Stanley Research, AI can automate up to 37% of tasks in real estate (a property-focused materials industry), unlocking an estimated $34 billion in efficiency gains by 2030 [11]. In the broader materials informatics sector, the revenue of firms offering MI services is forecast to grow at a 9.0% CAGR through 2035 [8]. These figures underscore the significant financial impact of adopting these technologies.

Performance Comparison of Feature Selection Methods

The performance of various feature selection methodologies can be quantitatively assessed across multiple metrics. The following table summarizes recent comparative data for several advanced FS methods applied to high-dimensional biological and proteomic datasets.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Feature Selection and Classification Methods

| Method | Dataset | Key Performance Metrics | Number of Features Selected |

|---|---|---|---|

| TMGWO-SVM [9] | Wisconsin Breast Cancer | Accuracy: 98.85% [9] | Not Specified |

| ST-CS [10] | Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma (CPTAC) | AUC: 97.47% | 37 (57% fewer than HT-CS) |

| HT-CS [10] | Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma (CPTAC) | AUC: 97.47% | 86 |

| ST-CS [10] | Glioblastoma | AUC: 72.71% | 30 |

| LASSO [10] | Glioblastoma | AUC: 67.80% | Not Specified |

| SPLSDA [10] | Glioblastoma | AUC: 71.38% | Not Specified |

| ST-CS [10] | Ovarian Serous Cystadenocarcinoma | AUC: 75.86% | 24 ± 5 |

| BBPSOACJ [9] | Multiple | Superior classification performance vs. comparison methods | Not Specified |

Table 2: Advantages and Limitations of Feature Selection Approaches

| Method Type | Examples | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Methods [10] | ANOVA, Pearson's correlation | Fast computation, model-agnostic | Neglects multivariate interactions |

| Wrapper Methods [10] | Genetic Algorithms | Optimizes feature subsets for specific models | Prohibitive computational cost in high-dimensional settings |

| Embedded Methods [10] | LASSO, Elastic Net | Integrates selection with model training | LASSO may discard weakly correlated biomarkers; Elastic net sacrifices sparsity |

| Hybrid FS Methods [9] | TMGWO, ISSA, BBPSO | Balances exploration and exploitation, enhances convergence accuracy | Increased algorithmic complexity |

| Compressed Sensing [10] | ST-CS, HT-CS | Robust sparse signal recovery, automates feature selection | Requires specialized implementation |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Soft-Thresholded Compressed Sensing (ST-CS) for Biomarker Discovery

Introduction ST-CS is a hybrid framework integrating 1-bit compressed sensing with K-Medoids clustering designed specifically for high-dimensional proteomic datasets characterized by technical noise, feature redundancy, and multicollinearity. Unlike conventional methods relying on manual thresholds, ST-CS automates feature selection by dynamically partitioning coefficient magnitudes into discriminative biomarkers and noise [10].

Materials and Reagents

- Software Environment: R programming language with Rdonlp2 package for sequential quadratic programming optimization.

- Input Data: High-dimensional proteomic profiles from mass spectrometry measurements (e.g., CPTAC datasets).

- Computational Resources: Standard workstation capable of handling matrices with dimensions (samples × features) where features >> samples.

Procedure

- Data Preprocessing: Standardize proteomic intensity data using z-score normalization to ensure equal feature contribution.

- Linear Decision Function Formulation: Define the decision score for the i-th sample as ( zi = ⟨w, xi⟩ ), where ( w ) denotes the coefficient vector, ( x_i ) encodes the proteomic profile, and ( ⟨·,·⟩ ) represents the Euclidean inner product.

- Constrained Optimization: Solve the constrained optimization problem:

- Maximize: ( ∑{i=1}^n yi ⟨w, xi⟩ )

- Subject to: ( ||w||1 + ||w||2^2 ≤ λ ) where ( yi ) represents binary class labels, ( ||w||1 ) promotes sparsity, ( ||w||2^2 ) controls multicollinearity, and ( λ ) is a hyperparameter controlling sparsity-intensity trade-off.

- Coefficient Clustering: Apply K-Medoids clustering to the magnitudes of the optimized coefficient vector ( |w| ) to automatically distinguish true biomarkers (large coefficients) from noise (near-zero coefficients).

- Feature Selection: Select features corresponding to coefficients in the cluster with largest magnitudes as the final biomarker set.

- Validation: Assess classification performance using AUC metrics and feature set sparsity.

Troubleshooting

- If convergence issues occur with the Rdonlp2 optimizer, adjust constraint tolerances or reformulate with penalty terms.

- If clustering fails to separate signals from noise clearly, consider varying the number of clusters (K) in the K-Medoids algorithm.

Protocol 2: Hybrid AI-Driven Feature Selection Framework

Introduction This protocol employs hybrid feature selection algorithms such as TMGWO (Two-phase Mutation Grey Wolf Optimization), ISSA (Improved Salp Swarm Algorithm), and BBPSO (Binary Black Particle Swarm Optimization) to identify significant features for classification in high-dimensional datasets. These metaheuristic algorithms introduce innovations that enhance the balance between exploration and exploitation in the feature selection process [9].

Materials and Reagents

- Datasets: Wisconsin Breast Cancer Diagnostic dataset, Sonar dataset, Differentiated Thyroid Cancer dataset.

- Classification Algorithms: K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Random Forest (RF), Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), Logistic Regression (LR), Support Vector Machines (SVM).

- Implementation Framework: Python with scikit-learn for classifiers and custom implementations of hybrid FS algorithms.

Procedure

- Data Preparation: Split datasets into training and testing sets using 10-fold cross-validation. Apply Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) to address class imbalance if necessary.

- Feature Selection Phase:

- For TMGWO: Implement two-phase mutation strategy to enhance exploration and exploitation balance.

- For ISSA: Incorporate adaptive inertia weights, elite salps, and local search techniques to boost convergence accuracy.

- For BBPSO: Utilize velocity-free mechanism with adaptive chaotic jump strategy to assist stalled particles.

- Classification Phase: Train multiple classifiers (KNN, RF, MLP, LR, SVM) on the selected feature subsets.

- Performance Evaluation: Compare algorithms based on accuracy, precision, and recall. Determine the most effective classifier based on the highest accuracy level.

- Comparative Analysis: Conduct comparative analysis of hybrid FS algorithms from multiple perspectives, including computational efficiency and feature reduction capability.

Troubleshooting

- If TMGWO converges prematurely, adjust mutation phase parameters to maintain population diversity.

- For BBPSO particles getting stuck in local optima, modify the adaptive chaotic jump parameters to enhance exploration.

Implementation and Visualization

Workflow Visualization

ST-CS Feature Selection Workflow: This diagram illustrates the automated biomarker discovery process using Soft-Thresholded Compressed Sensing, from data preprocessing to final validation.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Item Name | Type/Class | Function/Purpose | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Dimensional Proteomic Data | Data Input | Raw material containing protein intensity measurements from mass spectrometry | Biomarker discovery for cancer diagnostics [10] |

| CPTAC Datasets | Benchmark Data | Curated, real-world proteomic data for method validation | Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, glioblastoma studies [10] |

| Wisconsin Breast Cancer Dataset | Benchmark Data | Well-established dataset for classification algorithm validation | Evaluating TMGWO-SVM performance [9] |

| Rdonlp2 Package | Optimization Software | Sequential quadratic programming for constrained optimization | Solving ST-CS optimization problem [10] |

| K-Medoids Clustering | Algorithm | Partitioning coefficient magnitudes into biomarkers and noise | Automated thresholding in ST-CS [10] |

| SMOTE | Data Preprocessing | Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique for class imbalance | Balancing training data in TMGWO protocol [9] |

| Hybrid Metaheuristic Algorithms | Feature Selection | TMGWO, ISSA, BBPSO for identifying significant features | High-dimensional data classification [9] |

Materials Informatics Pipeline: This architecture shows the integrated role of automated feature selection within the broader materials informatics workflow, highlighting the iterative refinement process.

In the data-driven landscape of modern materials science, the ability to extract meaningful patterns from high-dimensional datasets is paramount for the discovery and optimization of novel materials. Feature selection—the process of identifying and selecting the most relevant input variables—serves as a critical pre-processing step to improve model performance, enhance interpretability, and reduce computational cost [12] [13]. This is particularly true in materials informatics, where datasets often contain a vast number of potential descriptors (e.g., derived from composition, structure, or processing conditions) but a relatively small number of experimental samples [14] [2]. By focusing on the most informative features, researchers can build more robust, efficient, and physically interpretable machine learning (ML) models, thereby accelerating the pipeline for predicting material properties [6] [4].

Feature selection methods are broadly categorized into three families: Filter, Wrapper, and Embedded methods. A fourth, emerging category explores Reinforcement Learning (RL) approaches, which frame feature selection as a sequential decision-making problem. The following sections detail these concepts, provide application notes tailored to materials science, and present experimental protocols for their implementation.

Core Methodologies and Theoretical Framework

Filter Methods

Filter methods assess the relevance of features based on intrinsic data properties, independent of any ML model. They rely on statistical measures to score and rank features, often making them computationally efficient and scalable to very high-dimensional datasets [12] [15].

- Core Principle: Features are filtered using statistical metrics that evaluate their relationship with the target variable.

- Common Techniques:

- Correlation Coefficient: Measures linear relationships between features and the target [12].

- Mutual Information: Quantifies the amount of information one variable provides about another, capable of detecting non-linear relationships [16].

- Variance Threshold: Removes features with low variance, assuming they contain little information [12].

- Chi-Square Test: Assesses independence between categorical features and the target [12].

- Advantages: High computational efficiency, model-agnostic nature, and simplicity [12] [15].

- Disadvantages: Ignores feature interactions and may fail to select the optimal subset for a specific model [12] [14].

Wrapper Methods

Wrapper methods evaluate feature subsets by using a specific ML model's performance as the evaluation criterion. They "wrap" themselves around a predictive model and search for the feature subset that yields the best model performance [12] [15].

- Core Principle: A search algorithm is used to explore combinations of features, and each subset is evaluated by training and testing a model.

- Common Techniques:

- Forward Selection: Starts with no features and iteratively adds the most contributive feature [12].

- Backward Elimination: Starts with all features and iteratively removes the least important feature [12].

- Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE): Recursively fits a model and removes the weakest features until the desired number is reached [12] [4].

- Advantages: Typically provide better predictive performance than filter methods by considering feature interactions and model-specific biases [12] [15].

- Disadvantages: Computationally intensive and prone to overfitting, especially with large feature sets [12] [14].

Embedded Methods

Embedded methods integrate the feature selection process directly into the model training phase. They combine the efficiency of filter methods with the performance-oriented nature of wrapper methods [12] [17].

- Core Principle: Feature selection is performed as an inherent part of the model's learning algorithm.

- Common Techniques:

- LASSO (L1 Regularization): Adds a penalty equal to the absolute value of the coefficients' magnitude, which can shrink some coefficients to zero, effectively performing feature selection [12] [17].

- Tree-Based Methods: Algorithms like Random Forest and Gradient Boosting provide native feature importance scores based on how much a feature decreases impurity across all trees [12] [17].

- Advantages: Computationally efficient, model-specific without the need for separate search, and often achieve high accuracy [15] [17].

- Disadvantages: The selection is tied to a specific model, which may limit generalizability [17].

Reinforcement Learning Approaches

While not as established as the three primary methods, Reinforcement Learning (RL) presents a novel paradigm for feature selection. RL formulates the process as a Markov Decision Process (MDP) where an agent learns to sequentially select or deselect features to maximize a cumulative reward, often defined by model performance and feature set parsimony. Although not explicitly detailed in the provided search results, this approach is an active area of research in automated machine learning (AutoML) and can be applied to materials discovery pipelines.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Feature Selection Methods

| Aspect | Filter Methods | Wrapper Methods | Embedded Methods | RL Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Statistical measures of feature relevance [12] | Guided search using model performance [12] | Built-in selection during model training [17] | Sequential decision-making to maximize reward |

| Computational Cost | Low [12] [15] | High [12] [14] | Medium [15] | Very High |

| Model Dependency | No (Unsupervised) [12] | Yes (Supervised) [12] | Yes (Supervised) [17] | Yes (Supervised) |

| Handles Feature Interactions | No [12] | Yes [12] | Yes [17] | Yes |

| Risk of Overfitting | Low [15] | High [15] | Medium [15] | Medium-High |

| Primary Use Case | Pre-processing for high-dimensional data [14] | Performance optimization for critical tasks | General-purpose supervised learning [17] | Automated feature engineering |

Application in Materials Properties Research

The selection of an appropriate feature selection strategy is highly dependent on the dataset characteristics and the research objective. The following workflow provides a guided approach for materials scientists.

Diagram 1: A workflow for selecting a feature selection method in materials informatics, highlighting the decision points based on data size and research goal. NG >> NS refers to a common scenario in materials data (e.g., microarray data) where the number of genes/features far exceeds the number of samples [14].

Protocol 1: Filter Method for High-Throughput Screening

This protocol is designed for initial analysis of high-dimensional materials data, such as gene expression from microarray experiments or vast compositional descriptors.

- Objective: To rapidly reduce the dimensionality of a dataset with thousands of features to a manageable number for subsequent modeling.

- Experimental Steps:

- Data Preparation: Load the dataset (e.g., a matrix where rows are samples and columns are features). Handle missing values appropriately (e.g., imputation or removal).

- Feature Scoring: Calculate a statistical score for each feature. For a continuous target (regression), use Pearson correlation. For a categorical target (classification), use ANOVA F-statistic or Mutual Information.

- Feature Ranking: Rank all features in descending order based on their calculated scores.

- Subset Selection: Select the top k features from the ranked list. The value of k can be chosen based on a threshold (e.g., p-value < 0.05) or a predefined number.

- Validation: The selected subset is then used to train a predictive model (e.g., Random Forest). Performance is compared against a model trained on the full feature set to validate the effectiveness of the selection.

Table 2: Quantitative Results from Filter Method Applied to Microarray Datasets (Adapted from [14])

| Dataset | Original Features | Selected Features (k) | Classification Accuracy (Full Set) | Classification Accuracy (Selected Subset) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colon Tumor | 2000 | 100 | 80.5% | 85.2% |

| Leukemia | 7129 | 150 | 92.1% | 95.8% |

| Lymphoma | 4026 | 200 | 88.7% | 91.3% |

Protocol 2: Embedded Method with Domain Knowledge Integration

This protocol leverages embedded methods, enhanced with domain knowledge, to build interpretable and accurate models for predicting material properties. The NCOR-FS method is a prime example [2].

- Objective: To select a non-redundant, physically meaningful subset of features that improves model accuracy and interpretability.

- Experimental Steps:

- Define Feature Pool: Assemble a comprehensive set of initial features/descriptors for the material system.

- Acquire Domain Knowledge Rules (NCORs):

- Data-Driven NCORs: Identify pairs of highly correlated features using statistical measures (e.g., Pearson correlation > 0.9).

- Knowledge-Driven NCORs: Consult domain experts or literature to identify feature pairs that are known to represent similar physical mechanisms or should not be used together. Formulate these as Non-Co-Occurrence Rules (NCORs).

- Formulate Optimization Problem: Define a multi-objective optimization function.

- Objective 1: Maximize model performance (e.g., minimize prediction error).

- Objective 2: Minimize the violation of the defined NCORs.

- Execute Feature Selection: Use a swarm intelligence algorithm (e.g., Multi-objective Particle Swarm Optimization) to search for the feature subset that best satisfies both objectives.

- Model Training and Validation: Train the final model using the selected feature subset and validate its performance on a hold-out test set.

Diagram 2: Workflow for the NCOR-FS embedded feature selection method, which integrates materials domain knowledge into the selection process to reduce feature correlation and improve interpretability [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Experiments

| Item / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use in Materials Informatics |

|---|---|---|

| MatSci-ML Studio | An interactive, GUI-based toolkit for automated ML in materials science [4]. | Provides a code-free environment for end-to-end workflow management, including multi-strategy feature selection (filter, wrapper, embedded) and model interpretation. |

| Scikit-learn | A comprehensive Python library for machine learning [4]. | Offers implementations for all major feature selection methods (e.g., SelectKBest for filters, RFE for wrappers, LassoCV for embedded). |

| Optuna | A hyperparameter optimization framework [4]. | Used to efficiently tune the parameters of wrapper and embedded feature selection methods (e.g., the number of features in RFE or the regularization strength in LASSO). |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | A game-theoretic approach to explain model output [12] [4]. | Provides post-hoc interpretability for any model, identifying the contribution of each selected feature to a specific prediction, crucial for validation against domain knowledge. |

| Automated Feature Selection Frameworks (e.g., AutoML) | Systems that automate the process of model selection and hyperparameter tuning. | Can be extended to include reinforcement learning agents that explore the space of feature subsets to optimize long-term performance metrics. |

Filter, Wrapper, and Embedded methods provide a versatile toolkit for tackling the "curse of dimensionality" in materials science research. Filter methods offer a fast starting point for massive datasets, wrapper methods can optimize for predictive performance at a higher computational cost, and embedded methods strike a practical balance between efficiency and efficacy. The emerging use of domain knowledge, as exemplified by the NCOR-FS method, and the potential of Reinforcement Learning, signal a move towards more intelligent, automated, and physically grounded feature selection pipelines. By strategically applying these protocols, researchers can enhance the accuracy, efficiency, and, most importantly, the interpretability of data-driven models for material property prediction, thereby accelerating the cycle of discovery and design.

In the field of materials informatics, the exponential growth of feature spaces—encompassing compositional, structural, and microstructural descriptors—presents a fundamental challenge for predictive modeling. Automated feature selection has emerged as a critical preprocessing step to navigate this complexity, directly impacting model performance across three key dimensions: predictive accuracy, generalization capability, and computational efficiency. Within materials research, where datasets are often limited and high-dimensional, selecting physically meaningful features becomes paramount for developing robust, interpretable models that accelerate the discovery of novel functional materials [5] [18].

The integration of machine learning (ML) in materials science has transformed traditional discovery paradigms, shifting from empirical trial-and-error to data-driven prediction [5]. However, the effectiveness of these ML models hinges on the quality and relevance of input features. Automated feature selection addresses this by systematically identifying optimal feature subsets, thereby enhancing model performance while providing insights into underlying physical relationships governing material properties [18] [19].

Quantitative Impact of Feature Selection on Model Performance

Empirical studies across materials science domains demonstrate that strategic feature selection consistently enhances model performance. The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from recent research.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Feature Selection Methods in Materials Property Prediction

| Model/Method | Feature Selection Approach | Target Property | Dataset Size | Performance Metric | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MODNet [18] | Feature selection + Joint learning | Vibrational Entropy (305K) | Limited dataset | Mean Absolute Error | 0.009 meV/K/atom (4x lower than benchmarks) |

| MODNet [18] | Feature selection + Joint learning | Formation Energy | N/A | Test Error | Outperformed graph-network models |

| Graph Networks (e.g., MEGNet) [18] | Automatic via graph convolution | Various properties | Large datasets required | Accuracy | High accuracy dependent on substantial data |

| LASSO Regression [20] | L1 regularization | Generic | N/A | Model Sparsity | Automatically shrinks irrelevant feature coefficients to zero |

| Random Forest/Gradient Boosting [20] | Embedded feature importance | Generic | N/A | Feature Ranking | Ranks features by impurity reduction (Gini/entropy) |

Table 2: Impact on Computational Efficiency and Generalization

| Aspect | Impact of Effective Feature Selection | Underlying Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Efficiency | Reduces training time and resource consumption [20] | Decreases dimensionality, lowering computational complexity |

| Generalization | Reduces overfitting on small materials datasets [18] [20] | Eliminates noisy, redundant, and irrelevant features |

| Interpretability | Highlights physically meaningful features [18] | Identifies key descriptors linked to material physics |

| Robustness | Improves model stability across diverse datasets | Focuses model on core, stable relationships |

Automated Feature Selection Frameworks and Protocols

Several advanced frameworks have been developed specifically to address the challenges of feature selection in computational materials science.

The MODNet Protocol for Materials Property Prediction

The Materials Optimal Descriptor Network (MODNet) is specifically designed for effective learning on limited datasets common in materials science [18]. The following workflow diagram illustrates its architecture:

Experimental Protocol:

- Feature Generation: Represent the raw crystal structure using a comprehensive set of physical, chemical, and geometrical descriptors. Utilize libraries like

matminerto generate features that encode elemental (e.g., atomic mass, electronegativity), structural (e.g., space group), and site-specific local environment information [18]. - Feature Selection: Apply a two-step, data-driven feature selection process:

- Calculate Normalized Mutual Information (NMI): Compute the NMI between each feature and the target property. NMI is superior to Pearson correlation as it captures non-linear relationships and is less sensitive to outliers [18].

- Relevance-Redundancy Filtering: Iteratively select features that maximize relevance to the target while minimizing redundancy with already-selected features. Use the dynamic scoring function from MODNet:

RR(f) = NMI(f, y) / [max(NMI(f, f_s))^p + c], wherepandcare hyperparameters that balance the trade-off [18].

- Model Training: Build a feedforward neural network with a tree-like architecture that enables joint learning. Share initial layers across multiple related properties (e.g., different vibrational properties) to imitate a larger dataset and improve generalization [18].

- Validation: Perform rigorous k-fold cross-validation and test on a held-out dataset. Use mean absolute error and other domain-relevant metrics to evaluate performance, especially compared to baseline models without feature selection.

Reinforcement Learning (RL) for Automated Feature Selection

Reinforcement Learning formulates feature selection as a sequential decision-making problem, offering a powerful alternative to traditional methods [19]. The framework involves an agent that interacts with the feature set environment.

Experimental Protocol:

- Problem Formulation:

- State (

s_t): A representation of the currently selected feature subset. This can be a vector of descriptive statistics, a graph encoding feature correlations, or an encoded representation from an autoencoder [19]. - Action (

a_t): A binary decision to include or exclude a specific feature from the subset. - Reward (

r_t): A feedback signal based on the predictive performance (e.g., accuracy) of a model trained on the selected feature subset, often penalized for larger subset sizes to encourage parsimony. For example,r = W_i * (Accuracy - β * Redundancy)[19].

- State (

- Algorithm Selection: Choose an RL algorithm suited to the problem scale.

- For high-dimensional spaces: Use Monte Carlo-based Reinforced Feature Selection (MCRFS) with early stopping to manage computational load [19].

- For complex feature interactions: Implement Multi-Agent RL (MARLFS), where each feature is an independent agent, or a Dual-Agent framework where one agent selects features and another selects relevant data instances [19].

- Training Loop: Let the agent explore the feature space over many episodes. The policy is optimized to maximize cumulative reward, converging on an optimal feature subset.

- Integration with Expert Knowledge: Implement Interactive RL (IRL) to allow external "trainers" (e.g., a decision tree or a KBest filter) to advise the agent, reducing the exploration space and incorporating domain priors [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Libraries for Automated Feature Selection

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function in Feature Selection | Application Context in Materials Science |

|---|---|---|---|

| MODNet [18] | Python Package | End-to-end framework with built-in feature selection and joint learning for small datasets. | Predicting formation energy, band gap, and vibrational properties from limited data. |

| Matminer [18] | Python Library | Provides a vast library of featurizers for generating material descriptors. | Creating initial feature sets from crystal structures, compositions, and sites. |

| Scikit-learn | Python Library | Implements filter (mutual info, correlation), wrapper (RFE), and embedded (LASSO) methods. | General-purpose feature selection for various material property prediction tasks. |

| Reinforcement Learning Frameworks (e.g., TensorFlow, PyTorch) | Library | Enables custom implementation of RL-based feature selection agents. | Building adaptive, automated feature selection systems for high-dimensional data. |

| Weka [21] | GUI/Java Software | Provides a suite of ML algorithms and feature selection tools for data mining. | Rapid prototyping and comparative analysis of feature selection methods. |

Automated feature selection is a cornerstone of modern materials informatics, directly determining the efficacy of data-driven models. By strategically reducing dimensionality, these methods significantly enhance predictive accuracy—as evidenced by MODNet's 4x error reduction on small datasets—while simultaneously improving generalization by eliminating noise and redundancy. Furthermore, they yield substantial gains in computational efficiency by focusing resources on the most salient descriptors. The integration of advanced paradigms like reinforcement learning and joint learning represents the future of fully automated, adaptive, and interpretable feature selection pipelines, ultimately accelerating the discovery and design of next-generation functional materials.

A Guide to Modern Automated Feature Selection Algorithms and Their Implementation

The application of Reinforcement Learning (RL) in materials science represents a paradigm shift from traditional, computationally expensive discovery processes. Within this domain, automated feature selection is a critical task, as the identification of the most relevant physical, chemical, and geometric descriptors from a vast potential set is essential for building accurate and generalizable property prediction models. RL frameworks provide a powerful methodology to automate this search for optimal feature subsets and model architectures, significantly accelerating materials research and drug development. These frameworks can be broadly categorized into single-agent strategies, where one agent learns to make sequential decisions, and multi-agent strategies, which leverage the collaborative or competitive dynamics of multiple agents to solve complex problems more efficiently. The choice between these strategies depends on the specific problem constraints, available computational resources, and the nature of the search space.

A Comparative Framework for RL Strategies

The selection of an RL strategy is foundational to the success of an automated feature selection pipeline. The table below summarizes the core architectural patterns, their mechanisms, and their suitability for different scenarios in materials and drug discovery research.

Table 1: Comparison of Single-Agent and Multi-Agent RL Strategies for Automated Workflows

| Strategy | Architectural Pattern | Mechanism & Control Topology | Typical Use Cases in Materials/Drug Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Agent (Meta-Learning) | Two-loop structure (Inner & Outer) [22] | The inner loop learns a task-specific policy (e.g., feature selection for a specific dataset), while the outer loop optimizes the inner loop's learning process across multiple tasks [22]. | Fast adaptation for predicting properties of new material classes or drug targets with limited data [22] [23]. |

| Swarm Intelligence (Multi-Agent) | Decentralized Multi-Agent [22] | Population-based search where simple agents follow local rules (e.g., Particle Swarm Optimization). Global behavior emerges from their interactions, balancing exploration and exploitation [22] [24]. | Large-scale feature space exploration and hyperparameter optimization for property prediction models [25] [24]. |

| Evolutionary (Multi-Agent) | Population-level [22] | A population pool of agent instances is evaluated; top performers are selected, mutated, and recombined over generations. A curriculum engine often adjusts task difficulty [22]. | Discovering novel molecular structures or complex, non-intuitive feature combinations for multi-target property prediction [22]. |

| Hierarchical (Single-Agent) | Centralized, Layered [22] | Splits decision-making into stacked layers (e.g., reactive, deliberative, meta-cognitive) with different time scales and abstraction levels [22]. | Robotics-assisted high-throughput experimentation, where low-level control is separated from high-level experimental planning [22]. |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Contrastive Meta-Reinforcement Learning for Heterogeneous Graph Neural Architecture Search (CM-HGNAS)

This protocol details a sophisticated single-agent strategy that combines meta-learning with contrastive learning to automate the design of neural networks for graph-based data, such as molecular or crystalline structures [23].

1. Objective: To automatically search for high-performing Heterogeneous Graph Neural Network (HGNN) architectures for tasks like node classification (e.g., predicting atom properties) and link prediction (e.g., predicting molecular interactions) on unseen datasets with limited data.

2. Experimental Workflow:

- Step 1: Problem Formulation. Define the search space of possible HGNN architectures (e.g., types of aggregation functions, attention mechanisms, layer depths).

- Step 2: Meta-Training Task Preparation. Assemble a diverse set of meta-training tasks from various datasets (e.g., DBLP, ACM, AMAZON). These tasks should include different types, such as node classification and link prediction [23].

- Step 3: Contrastive Learning Phase. To unify evaluation metrics across different task types, a contrastive learning loss is used. This phase trains the model to produce architecture embeddings such that high-performing architectures for a given task are grouped together, regardless of the task's native evaluation metric (e.g., Macro-F1 vs. ROC_AUC) [23].

- Step 4: Meta-Reinforcement Learning. The RL agent uses a recurrent neural network (RNN) as its controller. The controller's hidden state serves as the meta-knowledge carrier.

- The agent samples an architecture from the search space.

- The performance of the sampled architecture on a meta-training task is evaluated.

- This performance, transformed into a unified reward via the contrastive model, is used to update the controller's parameters using a policy gradient method, encouraging the generation of better architectures over time [23].

- Step 5: Rapid Adaptation to Novel Tasks. After meta-training, the agent's acquired meta-parameters are used to initialize the search process on a new, unseen meta-test task. This allows for rapid convergence to an optimal architecture with minimal additional training [23].

3. Visualization of Workflow:

Diagram 1: CM-HGNAS workflow.

Protocol 2: Hierarchical Self-Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization (HSAPSO) for Drug Classification

This protocol outlines a multi-agent RL strategy based on a swarm intelligence paradigm, applied to the problem of optimizing a deep learning model for drug target identification [25].

1. Objective: To achieve high-accuracy classification of druggable protein targets by optimizing the hyperparameters of a Stacked Autoencoder (SAE) feature extractor and classifier.

2. Experimental Workflow:

- Step 1: Data Curation. Collect drug-related data from sources like DrugBank and Swiss-Prot. Preprocess the data to ensure quality and extract initial feature representations [25].

- Step 2: HSAPSO Algorithm Initialization.

- Initialize a swarm of particles, where each particle's position represents a potential set of hyperparameters for the SAE (e.g., learning rate, number of layers, units per layer).

- The hierarchy in HSAPSO involves a self-adaptive mechanism where each particle dynamically adjusts its own behavior over iterations, balancing individual experience (cognitive component) and swarm influence (social component) more effectively than standard PSO [25].

- Step 3: Fitness Evaluation. For each particle's position (hyperparameter set):

- Train the SAE model.

- Evaluate the model's performance on a validation set using a target metric such as classification accuracy.

- This performance score is the particle's fitness.

- Step 4: Swarm Update.

- Each particle updates its velocity and position based on:

- Its personal best position (pbest) found so far.

- The global best position (gbest) found by any particle in the swarm.

- The self-adaptive parameters control the influence of these two components, allowing the swarm to avoid local minima and converge efficiently [25].

- Each particle updates its velocity and position based on:

- Step 5: Model Selection. After the optimization process converges, select the hyperparameter set from the gbest particle. Train the final optSAE model on the full training set and evaluate on a held-out test set [25].

3. Key Results: The optSAE + HSAPSO framework achieved a classification accuracy of 95.52% with significantly reduced computational complexity (0.010 s per sample) and high stability on benchmark datasets [25].

4. Visualization of Workflow:

Diagram 2: HSAPSO optimization workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues essential computational tools and frameworks that facilitate the implementation of RL strategies for automated feature selection and materials informatics.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents & Frameworks for RL-Driven Research

| Item Name | Function / Application | Relevant RL Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Hyperopt-sklearn | An AutoML library that automatically searches for the best combination of model algorithms and hyperparameters for a given dataset [26]. | Single-Agent / Swarm |

| CALYPSO | A crystal structure prediction software based on Particle Swarm Optimization, used to search for stable atomic configurations [24]. | Swarm Intelligence (Multi-Agent) |

| MODNet | A framework for materials property prediction that uses a feature selection algorithm based on Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) to choose physically meaningful descriptors [27]. | Not RL, but a foundational method for feature selection. |

| LangChain/LangGraph | Frameworks for building complex, stateful AI agents. LangGraph enables multi-agent coordination and cyclic workflows, useful for simulating complex research processes [28]. | Multi-Agent Orchestration |

| CrabNet | A materials property prediction model that uses a transformer architecture to interpret elemental compositions, representing a state-of-the-art supervised learning approach [27]. | Not RL, but a performance benchmark. |

Differentiable Information Imbalance (DII) represents a significant advancement in the field of automated feature selection, addressing fundamental challenges in the analysis of complex molecular systems and materials science research. Feature selection is a crucial step in data analysis and machine learning, aiming to identify the most relevant variables for describing a complex system. This process reduces model complexity and improves performance by eliminating redundant or irrelevant information [29]. In molecular contexts, features can include diverse variables such as distances between atoms, bond angles, or other chemical-physical properties that describe the structure and behavior of a molecule [29].

The DII method specifically addresses several persistent challenges in feature selection: determining the optimal number of features for a simplified yet informative model, aligning features with different units of measurement, and assessing their relative importance [30] [29]. Traditional feature selection methods, including wrapper, embedded, and filter approaches, often suffer from limitations such as combinatorial explosion problems, difficulties in handling heterogeneous variables, and inefficiencies in identifying the true optimal feature subset [30]. DII overcomes these limitations by providing an automated framework that evaluates the informational content of each feature and optimizes the importance of each variable using gradient descent optimization [30] [29].

Table 1: Comparison of Feature Selection Methods

| Method Type | Key Characteristics | Limitations | DII Improvements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wrapper Methods | Use downstream task as selection criterion | Combinatorial explosion problems | Task-agnostic through distance preservation |

| Embedded Methods | Incorporate feature selection into model training | Limited to specific model types | Model-agnostic approach |

| Filter Methods | Independent of downstream task | Often consider features individually | Multivariate feature evaluation |

| Traditional Unsupervised Filters | Exploit data manifold topology | No unit alignment capabilities | Automatic unit alignment and weighting |

The fundamental innovation of DII lies in its ability to compare the information content between sets of features using a measure called Information Imbalance (Δ) [30]. This measure quantifies how well pairwise distances in one feature space allow for predicting pairwise distances in another space, providing a score between 0 (optimal prediction) and 1 (random prediction) [30]. By making this measure differentiable, DII enables the use of gradient-based optimization techniques to automatically learn the most predictive feature weights, effectively addressing the challenges of unit alignment and relative importance scaling simultaneously [30].

Mathematical and Computational Framework

Fundamental Equations and Concepts

The mathematical foundation of DII builds upon the concept of Information Imbalance Δ, which serves as a robust measure for comparing the information content between different feature spaces. Given a dataset where each point i can be represented by two feature vectors, ({{{{\bf{X}}}}}{i}^{A}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{D}{A}}) and ({{{{\bf{X}}}}}{i}^{B}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{D}{B}}) (for i = 1, …, N), the standard Information Imbalance Δ(dA → dB) quantifies the prediction power that a distance metric built with features A carries about a distance metric built with features B [30]. The formal definition of Information Imbalance is expressed as:

$$\Delta \left({d}^{A}\to {d}^{B}\right):=\frac{2}{{N}^{2}}\,{\sum}{i,j:\,\,{r}{ij}^{A}=1}{r}_{ij}^{B}.$$

In this equation, ({r}{ij}^{A}) (respectively ({r}{ij}^{B})) represents the distance rank of data point j with respect to data point i according to the distance metric dA (resp. dB) [30]. For example, ({r}{ij}^{A}=7) indicates that j is the 7th neighbor of i according to dA. The Δ(dA → dB) value approaches 0 when dA serves as an excellent predictor of dB, as the nearest neighbors according to dA will also be among the nearest neighbors according to dB. Conversely, if dA provides no information about dB, the ranks ({r}{ij}^{B}) in the equation become uniformly distributed between 1 and N − 1, resulting in Δ(dA → dB) approaching 1 [30].

The differentiable version of this measure, DII, enables the optimization of feature weights through gradient descent. If the features in space A and the distances dA depend on a set of variational parameters w, finding the optimal feature space A requires optimizing (\Delta \left({d}^{A}({{{\boldsymbol{w}}}})\to {d}^{B}\right)) with respect to w [30]. The differentiability of this measure is crucial, as it allows for efficient optimization of feature weights to minimize the information loss when representing the data using the selected features rather than the full feature set or ground truth representation.

Optimization Approach and Algorithmic Implementation

The DII optimization process involves minimizing the information imbalance between a weighted feature space and a ground truth space through gradient-based methods. Each feature in the input space is scaled by a weight, which is optimized by minimizing the DII through gradient descent [30] [29]. This approach simultaneously addresses unit alignment and relative importance scaling while preserving interpretability [30]. The algorithm can also produce sparse solutions through techniques such as L1 regularization, enabling automatic determination of the optimal size of the reduced feature space [30].

Table 2: Key Mathematical Components of DII

| Component | Mathematical Representation | Role in DII Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Feature Weights | (w = (w1, w2, ..., w_D)) | Learnable parameters scaling each feature dimension |

| Distance Metric | (d^A(xi, xj) = \sqrt{\sum{k=1}^D wk^2 (x{i,k} - x{j,k})^2}) | Weighted Euclidean distance in feature space A |

| Information Imbalance | (\Delta \left({d}^{A}\to {d}^{B}\right):=\frac{2}{{N}^{2}}\,{\sum}{i,j:\,\,{r}{ij}^{A}=1}{r}_{ij}^{B}) | Core objective function to minimize |

| Gradient | (\nabla_w \Delta(d^A(w) \to d^B)) | Enables optimization via gradient descent |

The implementation of DII is available in the Python library DADApy [30] [29], providing researchers with an accessible tool for automated feature selection. The library includes comprehensive documentation and tutorials to facilitate adoption across various research domains [30].

Figure 1: DII Optimization Workflow - The iterative process for optimizing feature weights using Differentiable Information Imbalance.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Identifying Collective Variables for Biomolecular Conformations

Objective: To identify the optimal set of collective variables (CVs) that describe conformations of a biomolecule using DII [30] [29].

Materials and Data Requirements:

- Molecular dynamics (MD) trajectory data of the biomolecule

- Initial candidate features: interatomic distances, dihedral angles, contact maps, etc.

- Ground truth: high-dimensional feature space or relevant physical observables

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Extract structural snapshots from MD trajectories at regular intervals

- Calculate comprehensive set of potential features (distances, angles, etc.) for each snapshot

- Standardize features to zero mean and unit variance

Ground Truth Definition:

- Use all available features or a validated subset as the ground truth space B

- Alternatively, define ground truth based on physical observables or expert knowledge

DII Optimization:

- Initialize feature weights randomly or with heuristic values

- Compute pairwise distances in both the weighted feature space A and ground truth space B

- Calculate distance ranks and compute DII value

- Perform gradient descent to update feature weights to minimize DII

- Iterate until convergence (typically Δ < 0.1 or minimal improvement)

Result Interpretation:

- Identify features with highest final weights as most informative CVs

- Validate selected CVs through visualization of free energy landscape

- Compare with traditional CV selection methods for benchmarking

Technical Notes: The optimization can be enhanced with L1 regularization to promote sparsity in the feature weights, automatically determining the optimal number of CVs [30]. Computational cost scales with O(N²) due to pairwise distance calculations, making it suitable for medium-sized datasets (N ~ 10⁴ points).

Protocol 2: Feature Selection for Machine Learning Force Fields

Objective: To select optimal features for training machine-learning force fields using DII [30].

Materials and Data Requirements:

- Atomic configuration data with energies and forces

- Candidate descriptors: Atom-Centered Symmetry Functions (ACSFs), Smooth Overlap of Atomic Position (SOAP) descriptors, etc.

- Ground truth: High-quality descriptors or quantum mechanical calculations

Procedure:

- Descriptor Calculation:

- Generate extensive set of atomic environment descriptors (e.g., ACSFs with various parameters)

- Compute SOAP descriptors as potential ground truth [30]

- Normalize descriptors to account for different scales and units

DII Configuration:

- Set SOAP descriptors or quantum mechanical energies as ground truth space B

- Use ACSFs or other simplified descriptors as space A for optimization

- Configure distance metrics appropriate for descriptor spaces

Weight Optimization:

- Implement minibatch gradient descent for large datasets

- Monitor validation DII to prevent overfitting

- Apply sparsity constraints to identify minimal sufficient descriptor set

Validation:

- Train machine learning force fields using selected features

- Compare accuracy and computational efficiency with full feature set

- Assess generalization to unseen atomic configurations

Technical Notes: This approach is particularly valuable for identifying the most informative ACSFs, reducing the computational cost of force field evaluation while maintaining accuracy [30]. The method can also be used with different ground truth spaces depending on the specific application requirements.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for DII Implementation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function/Purpose | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DADApy Library | Software | Python implementation of DII and related algorithms | Available via pip/conda; requires Python 3.8+ [30] |

| Molecular Dynamics Data | Data Input | Trajectories for biomolecular CV identification | GROMACS, AMBER, or LAMMPS formats supported |

| Atomic Descriptors | Feature Generation | ACSFs, SOAP, etc. for ML force fields | Libraries: DScribe, ASAP, QUIP [30] |

| Optimization Framework | Computational Backend | Gradient descent optimization | PyTorch or JAX enable efficient DII minimization |

| Visualization Tools | Analysis | Free energy landscape projection | Matplotlib, PyEMMA, plumed |

| High-Performance Computing | Infrastructure | Handling large-scale molecular datasets | MPI parallelization for distance matrix calculations |

Application Notes and Case Studies

Case Study 1: Biomolecular Conformational Analysis

In the application to biomolecular conformational analysis, DII has demonstrated significant advantages over traditional approaches for identifying collective variables. Researchers applied DII to MD trajectories of a biomolecule, successfully identifying a minimal set of CVs that preserved the essential conformational dynamics [30] [29]. The DII approach automatically determined the optimal weighting of different types of features, such as distances, angles, and contact maps, resolving the unit alignment problem that typically plagues manual CV selection [30].

The key advantage observed in this application was DII's ability to identically preserve the neighborhood relationships present in the high-dimensional conformational space while using only a small subset of interpretable features. This resulted in CVs that produced more meaningful free energy landscapes and enhanced understanding of the biomolecular dynamics compared to traditional approaches [30].

Case Study 2: Machine Learning Force Field Optimization

For machine learning force fields, DII addressed the critical challenge of selecting the most informative descriptors from a large pool of candidate features. In the development of a water force field, researchers used DII with SOAP descriptors as ground truth to identify optimal subsets of ACSF descriptors [30]. This approach led to several important outcomes:

- Significant feature reduction: DII identified a compact set of ACSFs that preserved the essential information contained in the more complex SOAP descriptors [30].

- Improved computational efficiency: The selected features reduced the computational cost of force field evaluation while maintaining accuracy [30].

- Automatic unit alignment: DII automatically determined appropriate scaling factors for different types of symmetry functions, eliminating manual parameter tuning [30].

The success in this application demonstrates DII's potential for optimizing the trade-off between accuracy and efficiency in machine learning potential development, a crucial consideration for large-scale molecular simulations.

Figure 2: DII Application Pipeline - End-to-end workflow for applying DII in molecular systems research, from feature extraction to application outputs.

Advanced Applications and Future Directions