Anomaly Synthesis Recipes: Novel Methodologies for Biomedical Discovery and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of anomaly synthesis, a transformative methodology for generating artificial abnormal samples to overcome data scarcity in research and development. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we examine the foundational principles of teratogenesis and synthetic anomalies, detail cutting-edge techniques from hand-crafted to generative model-based approaches, and address critical troubleshooting and optimization challenges. The content further delivers a rigorous analysis of validation frameworks and comparative performance metrics, offering a roadmap for integrating these powerful recipes to accelerate insight generation and innovation in biomedical science.

Anomaly Synthesis Recipes: Novel Methodologies for Biomedical Discovery and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of anomaly synthesis, a transformative methodology for generating artificial abnormal samples to overcome data scarcity in research and development. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we examine the foundational principles of teratogenesis and synthetic anomalies, detail cutting-edge techniques from hand-crafted to generative model-based approaches, and address critical troubleshooting and optimization challenges. The content further delivers a rigorous analysis of validation frameworks and comparative performance metrics, offering a roadmap for integrating these powerful recipes to accelerate insight generation and innovation in biomedical science.

Foundations of Anomaly Synthesis: From Biological Teratogens to Computational Generators

FAQs: Core Concepts of Anomaly Synthesis

Q1: What is anomaly synthesis, and why is it critical for scientific research?

Anomaly synthesis is the artificial generation of data samples that represent rare, unusual, or faulty states. It is a promising solution to the "data scarcity" problem, a significant obstacle in applying artificial intelligence (AI) to scientific research and drug development [1] [2]. In fields like materials discovery or medical diagnosis, collecting enough real-world anomalous data (e.g., rare material defects or specific tumors) is often impossible, slow, or prohibitively expensive [1] [3]. Anomaly synthesis addresses this by creating diverse and realistic abnormal samples, enabling the development of robust machine learning models for tasks like predictive maintenance, quality control, and anomaly detection [4] [5].

Q2: What are the primary techniques for generating synthetic anomalies?

Techniques have evolved from simple manual methods to advanced generative models. The main categories include:

- Hand-crafted Methods: Early techniques using patch-level operations (e.g., cutting and pasting image sections) or random noise (e.g., Perlin noise) to simulate anomalies [5].

- Generative-Model-Based Methods: Modern approaches that produce more realistic and diverse anomalies. Key models include:

- Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs): Two neural networks (a Generator and a Discriminator) compete to produce increasingly realistic synthetic data [4].

- Diffusion Models: Advanced models that generate high-fidelity anomalies by iteratively denoising random noise, often conditioned on text descriptions or normal samples [6] [5].

Q3: How can synthetic data prevent model failure?

Synthetic data can mitigate critical AI failure modes like model collapse and bias [1].

- Model Collapse: This occurs when AI models are trained on data that includes their own or other AIs' outputs, leading to a feedback loop of degradation. High-quality synthetic data provides a fresh, diverse information source to prevent this [1].

- Bias: Real-world data often over-represents certain scenarios. Synthetic data can be generated to rebalance datasets, ensuring models are exposed to rare events and diverse conditions, leading to fairer and more accurate predictions [1].

Troubleshooting Guides: Implementing Anomaly Synthesis

Guide 1: Addressing Poor Model Performance Due to Data Scarcity

Problem: Your machine learning model for predicting material failures or drug compound efficacy is underperforming due to insufficient anomalous training data.

Solution: Implement a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) to synthesize run-to-failure data.

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Preprocessing: Clean your historical sensor or experimental data. Normalize the readings (e.g., using min-max scaling) to maintain consistent scales and handle any missing values [4].

- GAN Training:

- Generator (G): Takes a random noise vector as input and learns to map it to data points that resemble your real run-to-failure data.

- Discriminator (D): Acts as a binary classifier, learning to distinguish between real data from your training set and fake data generated by (G) [4].

- Adversarial Training: Train both networks concurrently in a mini-max game. The generator aims to fool the discriminator, while the discriminator improves at telling real and fake data apart. This competition continues until a dynamic equilibrium is reached [4].

- Synthetic Data Generation: Use the trained generator to produce synthetic run-to-failure data with patterns similar to your observed data but not identical to it [4].

- Model Retraining: Augment your original, scarce dataset with the newly generated synthetic data. Retrain your predictive model (e.g., an LSTM neural network or Random Forest) on this enhanced dataset [4].

Verification: After retraining, validate the model's performance on a held-out test set of real-world data. Key metrics should show significant improvement in accuracy for predicting rare failure events [4].

Guide 2: Generating Realistic, Unseen Anomalies for Zero-Shot Detection

Problem: You need to train a model to detect entirely new types of anomalies (e.g., a novel material defect or a rare cellular structure) for which you have no existing examples.

Solution: Use the "Anomaly Anything" (AnomalyAny) framework, which leverages a pre-trained Stable Diffusion model [6].

Experimental Protocol:

- Framework Setup: Implement the AnomalyAny framework, which is designed for zero-shot anomaly generation.

- Conditional Generation: During test time, condition the Stable Diffusion model on a single normal sample (e.g., an image of a normal material or cell) and a text description of the desired, unseen anomaly [6].

- Attention-Guided Optimization: Apply AnomalyAny's attention-guided anomaly optimization to direct the diffusion model's attention to generating "hard" anomaly concepts, improving the challenge and diversity of the synthesized data [6].

- Prompt Refinement: Use the framework's prompt-guided anomaly refinement, incorporating detailed textual descriptions to further enhance the visual quality and relevance of the generated anomalies [6].

- Downstream Training: Use the generated high-quality, unseen anomalies to train or augment your anomaly detection model, significantly enhancing its ability to generalize to new types of faults [6].

Verification: Benchmark your enhanced anomaly detection model on standard datasets (e.g., MVTec AD or VisA). The model should show improved performance in detecting both seen and unseen anomalies compared to models trained without synthetic data [6].

Quantitative Data and Method Comparison

The table below summarizes quantitative results from key studies that implemented anomaly synthesis to overcome data scarcity.

Table 1: Performance Impact of Anomaly Synthesis in Machine Learning Models

| Research Context | Synthesis Method | Base Model Performance (without synthesis) | Augmented Model Performance (with synthesis) | Key Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictive Maintenance [4] | Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) | ~70% detection accuracy for critical defects | ~95% detection accuracy for critical defects | Detection Accuracy |

| Predictive Maintenance [4] | Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) | ANN: N/A | ANN: 88.98% | Accuracy |

| Random Forest: N/A | Random Forest: 74.15% | |||

| Decision Tree: N/A | Decision Tree: 73.82% | |||

| Industrial Anomaly Detection (ASBench) [5] | Hybrid Multiple Synthesis Methods | Varies by base method | Significant improvement over single-method synthesis | Detection Accuracy |

Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

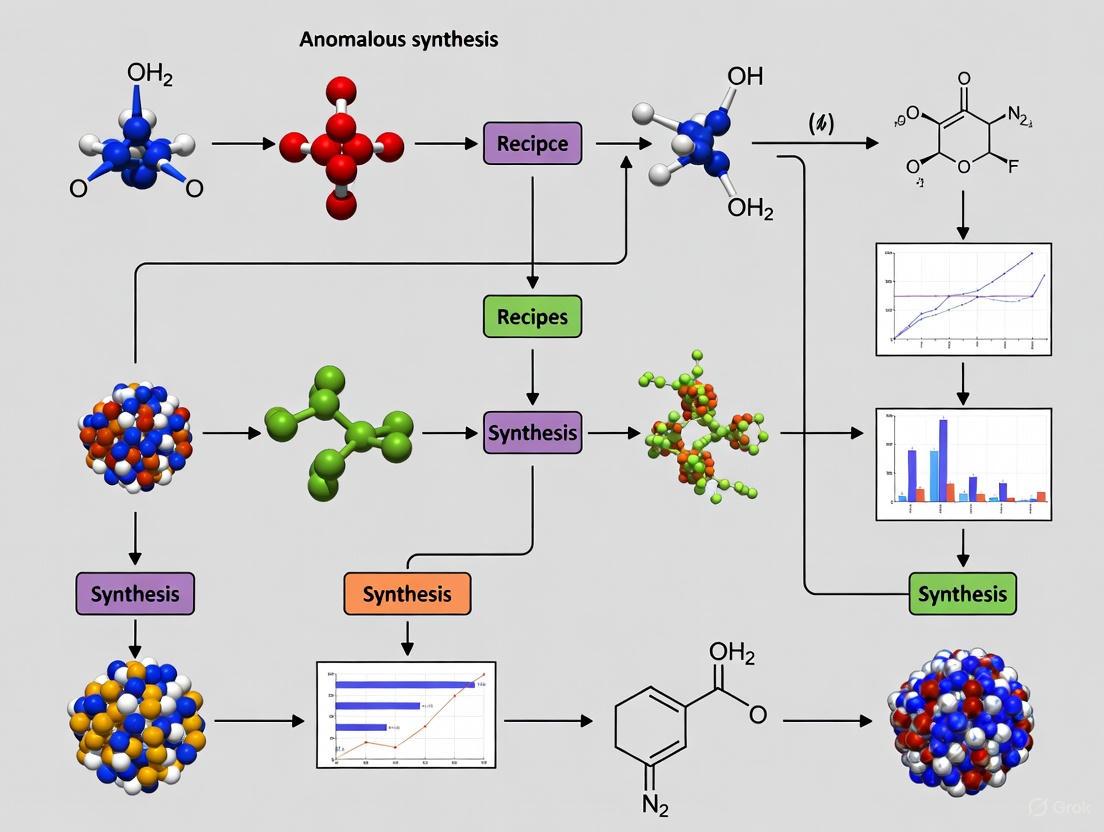

The following diagram illustrates the core adversarial training process of a GAN, a foundational technique for anomaly synthesis.

The diagram below outlines a modern, test-time anomaly synthesis workflow for generating unseen anomalies, as used in frameworks like AnomalyAny.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools and Algorithms for Anomaly Synthesis

| Item Name | Type | Primary Function in Anomaly Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) [4] | Algorithm | A framework for generating synthetic data through an adversarial game between a generator and a discriminator. Ideal for creating sequential sensor data or images. |

| Stable Diffusion Model [6] | Algorithm / Model | A pre-trained latent diffusion model capable of generating high-fidelity images. It can be conditioned on text and normal samples to create diverse, realistic unseen anomalies. |

| Perlin Noise [5] | Algorithm | A gradient noise function used in hand-crafted anomaly synthesis to generate realistic, semi-random anomalous textures for data augmentation. |

| Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) [4] | Algorithm | A type of recurrent neural network (RNN) effective at extracting temporal patterns from sequential data (e.g., sensor readings). Often used in conjunction with synthetic data for predictive maintenance. |

| Failure Horizons [4] | Data Labeling Technique | A method to address data imbalance in run-to-failure data by labeling the last 'n' observations before a failure as "failure," increasing the number of failure instances for model training. |

| Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) [1] | Review Framework | A process incorporating human expertise to validate the quality and relevance of synthetic datasets, ensuring ground truth integrity and preventing model degradation. |

| PF-915275 | PF-915275, CAS:857290-04-1, MF:C18H14N4O2S, MW:350.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Nothramicin | Nothramicin | Nothramicin is a research-grade anthracycline antibiotic with antimycobacterial and antitumor activity. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

The field of teratology, the study of abnormal development and birth defects, provides critical tools for researchers investigating anomalous synthesis recipes in developmental biology and toxicology. At the core of this field lie James G. Wilson's Six Principles of Teratology, formulated in 1959 and detailed in his 1973 monograph, Environment and Birth Defects [7]. These principles establish a systematic framework for understanding how developmental disruptions occur, guiding research into the causes, mechanisms, and manifestations of abnormal development [8]. For scientists pursuing new insights in developmental research, Wilson's principles offer a proven methodological approach for designing experiments, troubleshooting anomalous outcomes, and interpreting results within a structured theoretical context.

Wilson's Six Principles: Core Concepts and Research Applications

James G. Wilson's principles were inspired by earlier work, particularly Gabriel Dareste's five principles of experimental teratology from 1877 [7]. The six principles guide research on teratogenic agents—factors that induce or amplify abnormal embryonic or fetal development [7]. The table below summarizes these principles and their direct research applications.

| Principle | Core Concept | Research Application for Anomalous Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Genetic Susceptibility | Susceptibility depends on the genotype of the conceptus and its interaction with adverse environmental factors [7] [8]. | Different species (e.g., humans vs. rodents) or genetic strains show varying responses to the same agent [7]. |

| 2. Developmental Stage | Susceptibility varies with the developmental stage at exposure [7] [8]. | Timing of exposure is critical; organ systems are most vulnerable during their formation (organogenesis) [7] [8]. |

| 3. Mechanism of Action | Teratogenic agents act via specific mechanisms on developing cells and tissues to initiate abnormal developmental sequences [7]. | Identify the precise cellular or molecular initiating event (pathogenesis) to understand and potentially prevent defects [7]. |

| 4. Access to Developing Tissues | Access of adverse influences depends on the nature of the agent [7] [8]. | Physical (e.g., radiation) and chemical agents reach the conceptus differently; consider maternal metabolism and placental transfer [7] [8]. |

| 5. Manifestations of Deviant Development | Final outcomes are death, malformation, growth retardation, and functional deficit [7] [8]. | These four manifestations are interrelated; the same insult can produce different outcomes based on dose and timing [8]. |

| 6. Dose-Response Relationship | Manifestations increase in frequency and degree as dosage increases from no-effect to lethal levels [7] [8]. | Establish a dose-response curve; effects can transition rapidly from no-effect to totally lethal with increasing dosage [7] [8]. |

Troubleshooting Guides: Applying Wilson's Principles to Research Challenges

FAQ: How do I determine if my experimental compound is causing specific developmental anomalies?

Answer: Apply Wilson's third principle: "Teratogenic agents act in specific ways (mechanisms) on developing cells and tissues to initiate sequences of abnormal developmental events (pathogenesis)" [7]. This principle indicates that specific teratogenic agents produce distinctive malformation patterns rather than random defects [7].

Diagnostic Protocol:

- Characterize the Anomaly Pattern: Document the specific type, location, and combination of observed malformations

- Compare with Known Teratogens: Reference established teratogenic agents and their signature defects (e.g., thalidomide and limb reduction defects) [9]

- Investigate Cellular Mechanisms: Examine effects on fundamental developmental processes including cell proliferation, migration, differentiation, and cell death [10]

FAQ: Why does my compound produce severe defects in one species but minimal effects in another?

Answer: This reflects Wilson's first principle: "Susceptibility to teratogenesis depends on the genotype of the conceptus and the manner in which this interacts with adverse environmental factors" [7]. The classic example is thalidomide, which causes severe limb defects in humans and primates but minimal effects in many rodents [7].

Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Verify Species Differences: Research whether your compound exhibits known species-specific effects

- Examine Metabolic Pathways: Compare metabolic activation/detoxification pathways between species

- Check Genetic Factors: Investigate genetic polymorphisms affecting drug metabolism or target sensitivity

- Consider Maternal Physiology: Account for differences in placental structure, transfer rates, and maternal metabolism

FAQ: How can I explain variable outcomes where the same exposure causes different effects?

Answer: This variability reflects multiple Wilson principles simultaneously. Principle 2 (developmental stage) explains why timing of exposure produces different outcomes, while Principle 1 (genetic susceptibility) accounts for individual differences in response [7]. Principle 6 (dose-response) further clarifies that effects vary with dosage [7].

Diagnostic Table: Variable Outcome Analysis

| Observation | Possible Cause | Wilson Principle | Investigation Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Different malformation patterns | Exposure at different developmental stages | Principle 2: Developmental Stage | Precisely document exposure timing relative to developmental milestones |

| Variable severity in genetically similar subjects | Subtle environmental differences | Principle 1: Gene-Environment Interaction | Control for maternal diet, stress, housing conditions |

| Some subjects unaffected | Threshold effect or genetic resistance | Principle 6: Dose-Response | Establish precise dosing and examine genetic factors in non-responders |

| Multiple defect types from single exposure | Variable tissue susceptibility | Principle 2: Developmental Stage | Analyze critical periods for each affected organ system |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Developmental Toxicity Assessment

Standard Teratology Testing Protocol

This methodology implements Wilson's principles to systematically evaluate potential developmental toxicants, particularly relevant for assessing anomalous synthesis outcomes in pharmaceutical development [8].

Objective: To identify and characterize the developmental toxicity of test compounds using a standardized approach.

Materials and Reagents:

- Pregnant laboratory animals (typically rats or rabbits)

- Test compound and vehicle control

- Histological equipment and stains

- Skeletal preparation materials (alizarin red staining)

- Statistical analysis software

Procedure:

- Dose Selection: Based on Principle 6, establish a dose range from no observable adverse effect level (NOAEL) to clearly toxic levels [8] [10]

- Timed Pregnancies: Precisely time matings to enable exposure during specific developmental windows (Principle 2)

- Administration: Expose animals during critical periods of organogenesis (typically gestation days 6-15 in rats)

- Termination: Sacrifice animals just prior to term for comprehensive fetal examination

- Fetal Examination: Implement triple assessment:

- External examination for gross malformations

- Internal examination of visceral structures

- Skeletal examination using alizarin red staining

Data Interpretation:

- Analyze litter-based data rather than individual fetal data

- Compare incidence of malformations, variations, and developmental delays

- Establish dose-response relationships for different effect types

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Teratology Research

The following table details key reagents and their functions in developmental toxicity assessment, supporting researchers in establishing robust experimental protocols.

| Research Reagent | Function in Teratology Research | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Animal Models (rats, rabbits, mice) | In vivo assessment of developmental toxicity [8] | Select species based on metabolic relevance to humans; consider transgenic models for specific mechanisms |

| Alizarin Red S | Stains calcified skeletal tissue for bone and cartilage examination [8] | Essential for detecting subtle skeletal variations and malformations |

| Bouin's Solution | Tissue fixative for visceral examination | Provides superior preservation for internal organ assessment |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Vehicle for compound administration | Use minimal concentrations to avoid solvent toxicity; include vehicle controls |

| Embryo Culture Media | Supports whole embryo culture for mechanism studies | Enables direct observation of developmental processes in controlled conditions |

Advanced Research Applications: From Principles to Innovation

Historical Context and Modern Evolution

Wilson's principles built upon earlier teratology work, including that of Dareste who identified critical susceptibility periods by manipulating chick embryos [7] [8]. The thalidomide tragedy of the early 1960s tragically confirmed these principles in humans and brought developmental toxicology to regulatory forefront [9] [8]. Modern teratology has expanded to include functional deficits and behavioral teratology, recognizing these as significant manifestations of abnormal development [8] [10].

Contemporary Research Directions

Current research continues to apply Wilson's framework while incorporating new scientific advances:

- Endocrine Disruptors: Investigating compounds that challenge classical monotonic dose-response models [9]

- Functional Deficits: Recognizing that structural normalcy doesn't guarantee normal function [8]

- Molecular Mechanisms: Delineating precise pathways from molecular initiation to structural defects [8]

- Epigenetic Modifications: Exploring how environmental influences cause persistent changes without DNA sequence alteration

James G. Wilson's six principles of teratology continue to provide an essential conceptual framework for investigating abnormal development. For researchers exploring anomalous synthesis recipes and their effects on development, these principles offer proven guidance for experimental design, problem diagnosis, and data interpretation. By systematically applying these principles—addressing genetic susceptibility, developmental timing, specific mechanisms, agent access, manifestation spectra, and dose-response relationships—scientists can more effectively troubleshoot research challenges and advance our understanding of developmental disruptions. As teratology continues to evolve with new scientific discoveries, Wilson's foundational principles remain remarkably relevant for structuring research inquiries and interpreting anomalous developmental outcomes.

The Critical Need for Synthetic Anomalies in Drug Discovery and Safety Testing

Within the high-stakes field of drug discovery, the ability to predict and understand failures is just as valuable as the ability to predict successes. Your research into identifying anomalous synthesis recipes is a critical endeavor for uncovering new insights. This technical support center is designed to help you, the researcher, leverage synthetic anomalies—artificially generated data points that mimic rare or unexpected synthesis outcomes—to build more robust predictive models and accelerate the development of safe, effective therapeutics. By intentionally generating and studying these anomalies, you can overcome the limitations of sparse, real-world failure data and gain a deeper understanding of the complex chemical processes at play [11].

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

General Concepts

What are synthetic anomalies in the context of drug synthesis? Synthetic anomalies are artificially generated data points that mimic rare, unexpected, or failed synthesis outcomes in drug development. They are created using algorithms and generative models to simulate scenarios such as impure compounds, unexpected byproducts, or anomalous reaction pathways that may occur infrequently in real-world experiments but have significant implications for drug safety and efficacy [11] [12].

Why should I use synthetic anomaly data instead of real experimental data? Real experimental failure data is often scarce, costly to produce, and potentially risky. Synthetic anomalies provide a controlled, scalable, and privacy-compliant way to generate a comprehensive dataset of potential failure modes. This allows you to train machine learning models to recognize these anomalies without the time and resource constraints of collecting only real data, ultimately improving your model's ability to predict and prevent synthesis failures [11] [12].

Implementation & Methodology

What are the main methods for generating synthetic anomalies for chemical synthesis? You can choose from several methodological approaches, each with different strengths. The table below summarizes the core techniques.

| Method | Core Principle | Best For | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hand-crafted Synthesis [13] | Using domain expertise to manually define rules for anomalous reactions (e.g., introducing impurities). | Simulating known, well-understood synthesis failures or pathway deviations. | Highly interpretable but may lack complexity and miss novel anomalies. |

| Generative Models (GMs) [11] [12] | Using models like GANs or VAEs trained on real recipe data to generate novel, realistic anomalous recipes. | Creating high-dimensional, complex anomaly data that mirrors real-world statistical properties. | Requires quality training data; risk of generating unrealistic data if not properly validated. |

| Vision-Language Models (VLMs) [13] | Leveraging multi-modal models to generate anomalies based on text prompts (e.g., "synthesis with excessive exotherm"). | Exploring complex, conditional anomaly scenarios described in scientific literature or patents. | A cutting-edge approach; requires significant computational resources. |

How do I validate that my synthetic anomalies are realistic and useful? Validation is a multi-step process critical to the success of your project. The recommended protocol is the Train Synthetic, Test Real (TSTR) approach [12]:

- Split Your Real Data: Reserve a portion of your real, experimental synthesis data as a validation set.

- Train a Model: Train your predictive or anomaly detection model exclusively on your generated synthetic dataset, which includes both normal and anomalous synthesis recipes.

- Test on Real Data: Evaluate the model's performance on the held-out set of real experimental data.

- Analyze Performance: If the model performs well on the real data, it confirms that your synthetic anomalies accurately capture the properties of real-world synthesis. Additionally, you should statistically compare the synthetic data with the real data to ensure key properties and relationships are preserved [12].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue: My model, trained on synthetic anomalies, performs poorly on real experimental data. This is often a problem of data quality or model overfitting.

- Potential Solution 1: Validate Synthetic Data Quality. The synthetic data may not accurately capture the complexity of real chemistry. Revisit the validation step using the TSTR method and compare the statistical properties (e.g., distribution of reaction conditions, types of precursors) of your synthetic data against the real data. Improve your generative model or rules based on the discrepancies you find [12].

- Potential Solution 2: Prevent Overfitting. Your model may be learning the specific "artifacts" of the synthetic data rather than generalizable patterns. Introduce more diversity into your synthetic anomaly set and employ regularization techniques during model training. Ensure your synthetic data covers a wide range of plausible anomalous scenarios, not just a few types [11].

Issue: I am concerned about the privacy of proprietary synthesis data when using generative models.

- Potential Solution: Leverage Privacy-Preserving Generation. A key benefit of high-quality AI-generated synthetic data is that it reproduces the statistical patterns of the original data without containing or revealing the actual, sensitive information from the original dataset. When generated correctly, the synthetic recipes should not be reversible to the original, proprietary data, allowing for safer collaboration and data sharing [12].

Issue: My generative model produces chemically implausible or invalid synthesis recipes.

- Potential Solution: Incorporate Domain Expertise and Constraints. Move beyond purely data-driven generation. Integrate chemical rules and constraints (e.g., valency rules, feasible reaction templates, stability criteria) into the generative process. This can be done through hand-crafted rules as a baseline or by using hybrid models that combine machine learning with domain-knowledge graphs [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational and data resources essential for working with synthetic anomalies in a drug discovery context.

| Item / Resource | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) [11] [12] | A deep learning framework where two neural networks compete, enabling the generation of highly realistic and novel synthetic synthesis data that mimics real statistical properties. |

| Variational Autoencoder (VAE) [11] [12] | A generative model that learns a compressed, latent representation of input data (e.g., successful synthesis recipes) and can then generate new, anomalous data points by sampling from this latent space. |

| Synthetic Data Quality Assurance Report [12] | A diagnostic report, often provided by synthetic data generation platforms, that provides statistical comparisons between real and synthetic datasets to validate fidelity across multiple dimensions. |

| ACT Rule for Color Contrast [14] | A guideline for ensuring sufficient visual contrast in data dashboards and tools, critical for accurately interpreting complex chemical structures and model performance metrics without error. |

| Rs-029 | Rs-029, CAS:110230-95-0, MF:C13H16N6O6, MW:352.30 g/mol |

| NS-638 | NS-638, CAS:150493-34-8, MF:C15H11ClF3N3, MW:325.71 g/mol |

Experimental Workflows & Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the core iterative workflow for generating and utilizing synthetic anomalies in drug discovery, ensuring continuous model improvement.

Anomaly synthesis is a critical methodology for addressing the fundamental challenge of data scarcity in anomaly detection research, particularly in fields like drug discovery and development where anomalous samples are rare, costly, or dangerous to obtain [15] [16]. By artificially generating anomalous data, researchers can enhance the robustness and performance of detection algorithms, accelerating scientific discovery and ensuring safety in experimental processes. This technical support guide explores the three primary paradigms of anomaly synthesis—Hand-crafted, Distribution-based, and Generative Model-based approaches—within the context of identifying anomalous synthesis recipes for novel research insights. Each paradigm offers distinct methodological frameworks, advantages, and limitations that researchers must understand to effectively implement these techniques in their experimental workflows.

The scarcity of anomalous samples presents a significant bottleneck in developing reliable detection systems across multiple domains. In industrial manufacturing, low defective rates and the need for specialized equipment make real anomaly collection prohibitively expensive [15]. Similarly, in self-driving laboratories, process anomalies arising from experimental complexity and human-robot collaboration create substantial challenges for operational safety and require sophisticated detection capabilities [17]. Anomaly synthesis methodologies directly address these limitations by generating synthetic yet realistic anomalous samples, thereby transforming the data landscape for researchers and practitioners working on novel insight discovery through anomaly detection.

Comparative Analysis of Synthesis Paradigms

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Anomaly Synthesis Paradigms

| Paradigm | Core Methodology | Key Subcategories | Primary Applications | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hand-crafted Synthesis | Manually designed rules and image manipulations [15] | Self-contained synthesis; External-dependent synthesis; Inpainting-based synthesis [15] | Controlled environments where high realism is not critical; Industrial defect simulation [15] [18] | Straightforward implementation; Cost-efficient; Training-free [15] | Limited realism and defect diversity; Manual effort required; May not capture complex anomaly patterns [15] |

| Distribution Hypothesis-based Synthesis | Statistical modeling of normal data distributions with controlled perturbations [15] | Prior-dependent synthesis; Data-driven synthesis [15] | Scenarios with well-defined normal data distributions; Feature-space anomaly generation [15] | Leverages statistical properties of data; Enhanced diversity through perturbations [15] | Relies on accurate distribution modeling; May not capture complex real-world anomalies [15] |

| Generative Model (GM)-based Synthesis | Deep generative models including GANs, VAEs, and Diffusion Models [15] [19] | Full-image synthesis; Full-image translation; Local anomalies synthesis [15] | Complex anomaly generation requiring high realism; Industrial quality control; Medical imaging [15] [19] [16] | High-quality, realistic outputs; Can learn complex anomaly patterns; End-to-end training [19] | Computationally intensive; Training instability (GANs); Blurry outputs (VAEs); Slow inference (Diffusion Models) [19] |

| Vision-Language Model (VLM)-based Synthesis | Leverages large-scale pre-trained vision-language models [15] | Single-stage synthesis; Multi-stage synthesis [15] | Context-aware anomaly generation; Scenarios requiring multimodal integration [15] | Exploits extensive pre-trained knowledge; Integrated multimodal cues; High-quality, detailed outputs [15] | Emerging technology with unproven scalability; Computational demands [15] |

Table 2: Technical Characteristics of Synthesis Methods

| Method Category | Training Requirements | Inference Speed | Output Diversity | Realism Control | Data Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hand-crafted | None (training-free) [15] | Fast | Low to Moderate | Manual parameter tuning | Minimal (often just normal samples) |

| Distribution-based | Moderate (distribution fitting) | Fast | Moderate | Statistical bounds | Normal samples for distribution modeling |

| GM-based: GANs | High (adversarial training) [19] | Fast after training | High | Via latent space manipulation | Large datasets for stable training |

| GM-based: VAEs | Moderate (reconstruction loss) [19] | Fast | Moderate | Probabilistic latent space | Moderate datasets |

| GM-based: Diffusion | Very High [19] | Slow (many steps) [19] | Very High | Noise scheduling and conditioning | Very large datasets |

| VLM-based | Very High (pre-training) + Fine-tuning | Moderate to Slow | Very High | Prompt engineering and fine-tuning | Massive multimodal datasets |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: What are the key considerations when selecting an anomaly synthesis paradigm for drug discovery research?

Answer: Selection depends on multiple factors including dataset characteristics, computational resources, and research objectives. For initial exploration with limited data and resources, hand-crafted methods provide a practical starting point. When working with well-characterized normal datasets where statistical properties are understood, distribution-based approaches offer mathematical rigor. For complex anomaly patterns requiring high realism, GM-based methods are preferable despite their computational demands [15] [19]. In drug discovery contexts specifically, consider the biological plausibility of generated anomalies and regulatory requirements for model interpretability.

FAQ 2: How can we address the common challenge of generating unrealistic synthetic anomalies that don't generalize to real-world scenarios?

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: Synthetic anomalies lack realism and fail to improve detection performance on real data.

- Root Causes:

- Oversimplified anomaly modeling

- Insufficient domain knowledge incorporation

- Distribution shift between synthetic and real anomalies

- Solutions:

- Incorporate domain expertise through structured anomaly categorization (e.g., missing object, inoperable object, transfer failure categories for laboratory settings) [17]

- Implement multi-level synthesis as in DLAS-Net, which combines image-level and feature-level anomaly generation for enhanced realism [18]

- Utilize 3D rendering with physical accuracy for object-based anomalies, ensuring proper lighting, shadows, and perspective matching [16]

- Validate synthetic anomalies with domain experts before large-scale generation

- Employ hybrid approaches that combine the controllability of hand-crafted methods with the realism of generative models

FAQ 3: What strategies can improve training stability and output quality when using Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) for anomaly synthesis?

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: GAN training instability leading to mode collapse or poor sample quality.

- Root Causes:

- Unbalanced generator-discriminator competition

- Inadequate gradient flow

- Improper loss function design

- Solutions:

- Implement stabilization techniques including Lipschitz constraints, gradient penalty, spectral normalization, and batch normalization [19]

- Use alternative loss functions such as least squares loss or Wasserstein distance to improve training dynamics [19]

- Apply progressive growing techniques that start with low-resolution images and gradually increase resolution

- Utilize specialized architectures like StyleGAN for fine-grained control over anomaly characteristics [16]

- Monitor training metrics including inception score and Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) for objective quality assessment

FAQ 4: How can we effectively leverage limited real anomaly samples when working with synthesis methods?

Answer: Several strategies can maximize utility from limited real anomalies:

- Use real anomalies as references for hand-crafted methods rather than primary training data

- Implement data augmentation techniques specifically designed for anomaly detection contexts [15]

- Apply transfer learning where models pre-trained on synthetic anomalies are fine-tuned with limited real samples

- Utilize one-shot or few-shot learning approaches that can learn from minimal examples

- Employ active learning strategies to strategically select the most informative real anomalies for annotation [20]

FAQ 5: What are the emerging trends in anomaly synthesis that researchers in drug development should monitor?

Answer: Key emerging trends include:

- Vision-Language Models (VLMs) for context-aware anomaly synthesis using multimodal cues [15]

- Programmatic synthesis frameworks like LLM-DAS that leverage Large Language Models as "algorithmists" to reason about detector weaknesses and generate synthesis code [21]

- Differentiable rendering for more physically plausible object insertion in 3D contexts [16]

- Federated learning approaches enabling collaborative model training while preserving data privacy across institutions

- Explainable synthesis methods that provide rationale for why specific anomalies are generated, crucial for regulatory compliance in drug development

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Dual-Level Anomaly Synthesis (DLAS-Net) for Weak Defect Detection

Background: This protocol is designed for detecting weak, subtle anomalies in applications such as LCD defect detection or pharmaceutical manufacturing quality control [18].

Materials and Reagents:

- Normal samples dataset

- Anomaly mask generation toolkit

- Feature extraction network (pre-trained)

- Gaussian noise generator

- Gradient ascent optimization framework

Procedure:

- Image-Level Anomaly Synthesis:

- Generate diverse anomaly masks with transparency variations

- Simulate typical industrial defect patterns (scratches, spots, discolorations)

- Apply morphology operations to ensure shape diversity

- Incorporate low-contrast targets to enhance model sensitivity to subtle anomalies

Feature-Level Anomaly Synthesis:

- Extract features from normal samples using pre-trained network

- Inject Gaussian noise into normal feature representations

- Apply adaptive gradient ascent to perturb features toward decision boundaries

- Implement sophisticated truncated projection to maintain discriminative characteristics while staying close to normal feature distributions

Model Training:

- Train detection model on combined normal and synthesized anomaly samples

- Utilize multi-task learning to jointly optimize for anomaly classification and localization

- Apply progressive difficulty scheduling to gradually introduce more challenging synthetic anomalies

Validation Metrics:

- Image-level AUROC (Area Under Receiver Operating Characteristic curve)

- Pixel-level AUROC for localization tasks

- Precision-Recall metrics for imbalanced data scenarios

Protocol 2: SYNAD Pipeline for 3D Object Injection

Background: This protocol describes a systematic approach for inserting 3D objects into 2D images to create synthetic anomalies, particularly useful for foreign object detection in laboratory and manufacturing environments [16].

Materials and Reagents:

- Background image dataset

- 3D object models in .blend format or compatible 3D formats

- Blender rendering software

- Lighting estimation toolkit

- Ground plane detection algorithm

Procedure:

- Input Data Preparation:

- Collect background images with consistent camera positioning

- Prepare 3D object models representing potential anomalous objects

- Set base scale, rotation, and color parameters for each object type

Lighting and Ground Plane Estimation:

- Analyze background images to estimate lighting conditions

- Detect ground plane geometry and perspective

- Calculate shadow casting parameters based on lighting analysis

Object Placement and Model Adaptation:

- Position 3D objects in physically plausible locations

- Orient objects according to ground plane geometry

- Adjust object scale to match scene perspective

Object Randomization:

- Apply random variations to object appearance, position, and orientation

- Introduce material and texture variations

- Generate multiple poses for each object type

Output Data Generation:

- Render composite images with integrated objects

- Generate pixel-perfect anomaly masks during rendering

- Export paired image-mask datasets for training

Validation Approach:

- Compare detection performance on real anomalies versus synthetic-only training

- Assess model generalization across different object types and scenes

- Evaluate physical plausibility through domain expert review

Protocol 3: LLM-Guided Programmatic Anomaly Synthesis (LLM-DAS)

Background: This innovative approach repositions Large Language Models as "algorithmists" that analyze detector weaknesses and generate detector-specific synthesis code, particularly valuable for tabular data in drug discovery contexts [21].

Materials and Reagents:

- Large Language Model with code generation capabilities

- Target anomaly detector algorithm description

- Normal training dataset (not exposed to LLM)

- Code execution environment

Procedure:

- Detector Analysis Phase:

- Provide LLM with high-level description of target detector's algorithmic mechanism

- Prompt LLM to identify detector-specific weaknesses and blind spots

- Guide LLM to reason about types of anomalies that would be "hard-to-detect"

Code Generation Phase:

- LLM generates Python code for anomaly synthesis targeting identified weaknesses

- Ensure code is data-agnostic and reusable across datasets

- Implement synthesis strategies that exploit detector vulnerabilities

Code Instantiation and Execution:

- Execute generated synthesis code on specific dataset

- Generate "hard-to-detect" anomalies tailored to the detector

- Augment training data with synthesized anomalies

Detector Enhancement:

- Retrain or fine-tune detector on augmented dataset

- Transform learning problem from one-class to two-class classification

- Evaluate enhanced robustness against previously challenging anomalies

Key Advantages:

- Preserves data privacy by not exposing raw data to LLM

- Generates reusable, detector-specific synthesis logic

- Systematically addresses logical blind spots of existing detectors

Workflow Visualization and Experimental Design

Synthesis Taxonomy Overview

Dual-Level Anomaly Synthesis Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Anomaly Synthesis

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Application Context | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Sources | Normal samples dataset | Provides baseline distribution for synthesis | All paradigms | Representativeness critical for synthesis quality |

| Real anomaly references (if available) | Guides realistic anomaly generation | Hand-crafted, GM-based | Even small numbers can significantly improve realism | |

| 3D object models (.blend format) [16] | Source objects for synthetic insertion | 3D rendering approaches | Physical plausibility and domain relevance essential | |

| Software Tools | Blender [16] | 3D modeling and rendering for object insertion | SYNAD pipeline | Enables physically accurate lighting and shadows |

| Pre-trained VLM models | Base models for vision-language synthesis | VLM-based approaches | Require prompt engineering or fine-tuning | |

| GAN/VAE/Diffusion frameworks | Core engines for generative synthesis | GM-based paradigms | Choice depends on data type and quality requirements | |

| Computational Resources | GPU clusters | Accelerate model training and inference | GM-based, VLM-based | Substantial requirements for large-scale generation |

| Memory optimization tools | Handle large datasets and model parameters | All paradigms | Critical for scaling to industrial applications | |

| Validation Tools | Domain expert review panels | Assess biological/physical plausibility | Drug discovery contexts | Essential for regulatory compliance |

| Automated metric calculators | Quantitative evaluation (FID, AUROC, etc.) | All paradigms | Standardized protocols needed for fair comparison [20] | |

| Specialized Methodologies | LLM code generation [21] | Programmatic synthesis targeting detector weaknesses | LLM-DAS approach | Preserves privacy by not exposing raw data |

| Multi-level synthesis [18] | Combined image-level and feature-level generation | Weak defect detection | Enhances sensitivity to subtle anomalies |

Advanced Methodological Considerations

Evaluation Frameworks and Metric Selection

Robust evaluation is essential for validating anomaly synthesis methodologies. Researchers should employ multiple complementary metrics to assess different aspects of synthesis quality:

Synthesis Quality Metrics:

- Fréchet Inception Distance (FID): Measures statistical similarity between real and synthetic anomaly distributions

- Precision-Recall Analysis: Particularly important for imbalanced datasets common in anomaly detection [20]

- Domain-specific plausibility assessments: Expert evaluation of biological or physical realism in generated anomalies

Detection Performance Metrics:

- Area Under ROC Curve (AUROC): Overall detection performance across thresholds

- Area Under Precision-Recall Curve (AUPR): More informative for highly imbalanced data [20]

- Pixel-level localization accuracy: For tasks requiring precise anomaly localization

Recent research emphasizes that no single algorithm dominates across all scenarios, and method effectiveness depends heavily on data characteristics, anomaly types, and domain requirements [20]. Researchers should implement standardized evaluation protocols that strictly separate normal data for training and testing while assigning all anomalies to the positive test set.

Emerging Integration Patterns

The field is evolving toward hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of multiple paradigms:

Programmatic-Learning Integration: Frameworks like LLM-DAS demonstrate how programmatic synthesis generated by LLMs can be combined with data-driven learning approaches [21]. This preserves privacy while enabling targeted augmentation that addresses specific detector weaknesses.

Multi-scale Synthesis Architectures: Approaches like DLAS-Net show the value of combining image-level and feature-level synthesis in a coordinated framework [18]. This enables addressing both coarse and subtle anomalies within a unified methodology.

Cross-modal Fusion: Leveraging multiple data modalities (e.g., visual, textual, structural) enhances synthesis realism and applicability to complex domains like self-driving laboratories [17]. Vision-language models are particularly promising for this integration.

As anomaly synthesis methodologies continue to advance, researchers in drug discovery and development should maintain flexibility in their technical approaches while rigorously validating synthesis quality against domain-specific requirements. The optimal approach often involves carefully balanced hybrid methodologies that leverage the complementary strengths of hand-crafted, distribution-based, and generative model paradigms.

Methodologies in Practice: A Technical Guide to Anomaly Synthesis Recipes

Hand-crafted synthesis represents a foundational approach to generating anomalous data through manually designed rules and algorithms. This methodology operates without extensive training data, instead relying on predefined transformations and perturbations applied to normal samples to create controlled anomalies. Within industrial and scientific contexts, these techniques address the fundamental challenge of anomaly scarcity by generating synthetic defective samples for training and validating detection systems [15].

The core value of hand-crafted methods lies in their interpretability, computational efficiency, and suitability for environments with well-defined anomaly characteristics. By implementing controlled perturbations—such as geometric transformations, texture modifications, or structural rearrangements—researchers can systematically generate anomalies that mimic real-world defects while maintaining complete understanding of the generation process [15].

Core Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Self-Contained Synthesis Techniques

Self-contained synthesis operates by directly manipulating regions within the original image itself, creating anomalies derived entirely from the existing content without external references [15].

Protocol 1: CutPaste-based Anomaly Synthesis

- Objective: Simulate structural defects and misalignments by relocating image patches.

- Procedure:

- Select a random rectangular patch from a normal training image.

- Apply affine transformations (rotation, scaling) to the extracted patch.

- Paste the transformed patch back into a different location within the original image.

- Use Poisson blending or edge feathering to create smooth transitions between the pasted patch and background.

- Applications: Effective for detecting structural anomalies, misassembled components, or surface disruptions where texture remains consistent but structure changes [15].

Protocol 2: Bézier Curve-guided Defect Simulation

- Objective: Generate realistic scratch and crack anomalies with natural curvature variations.

- Procedure:

- Define control points for Bézier curves to model scratch/crack paths.

- Render the curve with varying thickness and intensity to simulate depth perception.

- Overlay the rendered curve onto normal images using blending modes.

- Add random noise along the curve path to create natural imperfections.

- Applications: Ideal for simulating fine scratches, hairline cracks, or linear defects on manufactured surfaces [15].

External-Dependent Synthesis Approaches

External-dependent synthesis utilizes resources external to the original image, such as texture libraries or defect templates, to create anomalies independent of the source image content [15].

Protocol 3: Texture Library-based Defect Generation

- Objective: Introduce foreign textures and materials as anomalies.

- Procedure:

- Curate a library of anomalous textures (stains, discolorations, foreign materials).

- Segment target regions in normal images for anomaly insertion.

- Apply color matching and illumination adjustment to blend external textures.

- Use mask-guided fusion to integrate external textures with background content.

- Applications: Effective for contaminant detection, material inconsistency identification, and surface staining scenarios [15].

Inpainting-Based Synthesis Methods

Inpainting-based approaches create anomalies by deliberately removing or corrupting local image regions, thereby disrupting structural continuity [15].

Protocol 4: Mask-Guided Region Corruption

- Objective: Simulate missing components or occluded regions.

- Procedure:

- Generate random masks of varying shapes and sizes across the image.

- Apply corruption to masked regions using: (a) Noise injection (Gaussian, salt-and-pepper), (b) Uniform coloring, or (c) Texture replacement.

- Ensure mask diversity to cover various anomaly scales and locations.

- Applications: Useful for training detection systems to identify missing parts, corrosion spots, or obliterated regions [15].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Hand-crafted Synthesis Methods

| Method Category | Anomaly Realism Score (1-5) | Computational Cost | Implementation Complexity | Best-Suited Anomaly Types |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Contained | 3.2 | Low | Low | Structural defects, misalignments |

| External-Dependent | 3.8 | Medium | Medium | Foreign contaminants, texture anomalies |

| Inpainting-Based | 2.9 | Very Low | Low | Missing components, occlusions |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Computational Resources for Anomaly Synthesis Experiments

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| MVTec AD Dataset | Benchmark dataset for validation | Provides 3629 normal training images and 1725 test images across industrial categories [22] |

| Bézier Curve Toolkits | Mathematical modeling of curved anomalies | Python svg.path or custom parametric curve implementations for scratch generation [15] |

| Poisson Blending Libraries | Seamless integration of pasted elements | OpenCV seamlessClone() function for natural patch blending [15] |

| Texture Libraries | Source of external anomalous patterns | Curated collection of stain, crack, and contaminant textures at varying scales [15] |

| Mask Generation Algorithms | Creating region selection for corruption | Random shape generators with controllable size and spatial distributions [15] |

| AKR1C1-IN-1 | AKR1C1-IN-1, CAS:4906-68-7, MF:C13H9BrO3, MW:293.11 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| RSV604 | RSV604, CAS:676128-63-5, MF:C22H17FN4O2, MW:388.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ 1: Why do synthetic anomalies appear unrealistic and fail to improve detection performance?

- Issue: Synthetic anomalies lack contextual consistency with background content, creating easily distinguishable artifacts rather than realistic defects.

- Solution: Implement background-aware generation constraints. Ensure anomalies respect background texture patterns and illumination conditions. For example, when pasting patches, apply gradient domain blending rather than direct overlay. Recent approaches propose disentanglement losses to separate background and defect generation processes while maintaining contextual relationships [23].

- Prevention: Conduct realism validation with domain experts before large-scale synthesis. Use perceptual similarity metrics alongside traditional pixel-level measures.

FAQ 2: How can we address limited diversity in synthetic anomaly patterns?

- Issue: Hand-crafted methods often produce repetitive anomaly patterns that lead to overfitting rather than robust detection.

- Solution: Introduce orthogonal perturbation strategies that generate diverse anomalies while maintaining realism. Train conditional perturbators to create input-dependent variations rather than fixed transformations. Constrain perturbations to remain proximal to normal samples to ensure plausibility [24].

- Prevention: Implement anomaly diversity metrics to quantitatively assess variation in synthetic datasets before training detection models.

FAQ 3: What approaches improve synthesis for logical anomalies versus structural defects?

- Issue: Logical anomalies (contextual inconsistencies) are particularly challenging as they may not manifest as visual distortions.

- Solution: Develop relationship-aware synthesis that models interactions between image components rather than local transformations. For object assembly anomalies, simulate component misplacements or incorrect combinations that violate functional relationships [23].

- Prevention: Incorporate semantic understanding through lightweight fine-tuning of vision-language models to generate contextually inappropriate elements.

FAQ 4: How can we optimize the trade-off between anomaly realism and implementation complexity?

- Issue: Highly realistic anomaly synthesis often requires complex generative models with substantial computational resources.

- Solution: Implement adaptive synthesis pipelines that apply appropriate methods based on anomaly type and application context. Use simpler hand-crafted methods for obvious structural defects and reserve complex approaches for subtle, context-dependent anomalies [22].

- Prevention: Conduct requirement analysis to determine the necessary level of realism for specific detection tasks rather than maximizing realism universally.

Visual Workflows for Anomaly Synthesis

Hand-crafted Synthesis Method Selection Workflow

Adaptive Synthesis and Triplet Training Workflow

This technical support center provides resources for researchers applying Distribution-Hypothesis-Based Synthesis in materials science and drug development. This methodology leverages machine learning to analyze "normal" feature spaces derived from successful historical synthesis recipes. The core hypothesis posits that intelligent perturbation of these learned spaces can identify anomalous, yet promising, synthesis pathways that defy conventional intuition, thereby accelerating the discovery of novel materials and compounds [25]. The following guides and FAQs address specific experimental challenges encountered in this innovative research paradigm.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Poor Model Generalization to Novel Compositions

Problem Statement: A machine learning model trained on text-mined synthesis recipes fails to predict viable synthesis conditions for novel material compositions, instead suggesting parameters similar to existing recipes without meaningful innovation [25].

| Troubleshooting Step | Action | Rationale & Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Verify Data Quality | Audit the training dataset for variety and veracity [25]. Check for over-representation of specific precursor classes or reaction conditions. |

Anthropogenic bias in historical data can limit model extrapolation. Identifying gaps allows for targeted data augmentation. |

| 2. Implement Attention-Guided Perturbation | Introduce sample-aware noise to the input features during training, focusing perturbation on critical feature nodes identified via an attention mechanism [26]. | Prevents the model from learning simplistic "shortcuts," forcing it to develop a more robust understanding of underlying synthesis principles. |

| 3. Validate with Anomalous Recipes | Test the model on a curated set of known, but rare, successful synthesis recipes that differ from the majority. | A robust model should assign higher probability to these true anomalies, validating its predictive capability beyond the training distribution. |

| 4. Incorporate Reaction Energetics | Use Density Functional Theory (DFT) to compute the reaction energetics (e.g., energy above hull) for a subset of predicted reactions [25]. | Provides a physics-based sanity check. A promising anomalous recipe should still be thermodynamically plausible. |

Guide 2: Diagnosing Failure in Anomaly Detection During Synthesis Screening

Problem Statement: High-throughput experimental screening fails to identify any successful syntheses from model-predicted "anomalous" candidates, resulting in a low hit rate.

| Troubleshooting Step | Action | Rationale & Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Check Contrastive Learning Setup | For GCL models, ensure the pretext task measures node-level differences between original and augmented graphs, using cosine dissimilarity for accurate measurement [27]. | Prevents representation collapse where semantically different synthesis pathways are mapped to similar embeddings, ensuring true anomalies are distinguishable. |

| 2. Recalibrate Anomaly Threshold | Analyze the distribution of model confidence scores for known successful and failed syntheses. Adjust the threshold for classifying a recipe as an "anomaly of interest." | An improperly calibrated threshold may discard promising candidates or include too many false positives. |

| 3. Review Precursor Selection | Manually examine the precursors suggested for the failed syntheses. Investigate if kinetic barriers, rather than thermodynamic stability, prevented the reaction [25]. | The model may have identified a valid target but suggested impractical precursors. This can inspire new mechanistic hypotheses about reaction pathways. |

| 4. Verify Experimental Fidelity | Ensure that the automated synthesis platform accurately implements the predicted parameters (e.g., temperature gradients, mixing times). | Discrepancies between digital prediction and physical execution are a common failure point. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our text-mined synthesis dataset is large but seems biased towards certain chemistries. How can we build a robust "normal" feature space from this imperfect data?

A1: Acknowledging data limitations is the first step. Historical data often lacks variety and carries anthropogenic bias [25]. To build a robust feature space:

- Apply Weighting Schemes: Assign lower weight to over-represented synthesis pathways during model training.

- Leverage Transfer Learning: Pre-train your model on a large, general chemical database (e.g., from the Materials Project [25]) and then fine-tune it on your domain-specific, text-mined data.

- Focus on Anomalies: The primary value of a biased "normal" space may not be in its representativeness, but in the rare, anomalous recipes that defy its trends. These outliers are often the source of new scientific insights [25].

Q2: What is the difference between random perturbation and attention-guided perturbation of the feature space, and why does it matter?

A2:

- Random Perturbation adds uniform noise to all features in a sample-agnostic manner. It is simple but inefficient, as it treats all features as equally important [26].

- Attention-Guided Perturbation uses a learned model to identify the most critical features or regions in the input data (e.g., specific precursor attributes or reaction conditions) and applies more aggressive, targeted noise to these areas [26]. This forces the model to learn more invariant and robust patterns at these key locations, leading to more efficient training and a feature space that is better at identifying meaningful, rather than random, anomalies.

Q3: We successfully identified an anomalous synthesis recipe experimentally. How should we integrate this new knowledge back into our models?

A3: This is a crucial step for iterative discovery.

- Document the Recipe: Formally document the successful synthesis as a new data point, including all precursors, operations, and conditions, following a structured JSON format as in previous text-mining efforts [25].

- Feature Vector Update: Encode this new recipe into the feature space of your model.

- Model Retraining: Periodically retrain your machine learning models on the augmented dataset that includes newly validated anomalies. This continuously refines the definition of "normal" and expands the model's understanding of viable synthesis space.

Q4: How can we visually diagnose if our Graph Contrastive Learning (GCL) model is effectively capturing the differences between synthesis pathways?

A4: You can design a diagnostic experiment based on a technique like UMAP for visualization.

- Procedure: Generate a 2D UMAP plot of the embeddings from your GCL model for a set of known synthesis recipes.

- Interpretation: If the model is working well, recipes with similar underlying mechanisms should cluster together. More importantly, confirmed anomalous recipes should appear as clear outliers in distinct regions of this plot. The separation between different clusters and outliers provides a visual assessment of the model's discriminative power [27].

Experimental Protocol: Node-Level Graph Contrastive Learning for Synthesis Prediction

This protocol details a method to train a model that learns nuanced differences between material synthesis pathways.

1. Objective: To implement a Graph Contrastive Learning (GCL) framework that accurately captures node-level differences between original and augmented synthesis graphs, enabling the identification of semantically distinct (anomalous) synthesis recipes [27].

2. Materials and Data Input:

- Synthesis Graph: Each synthesis recipe is represented as a graph where nodes are chemical precursors or targets, and edges represent synthesis operations or relationships [25].

- Feature Matrices: Node features (e.g., chemical descriptors) and the graph adjacency matrix.

3. Methodology:

- Step 1 - Graph Augmentation: Apply multiple augmentation strategies (e.g., random edge dropping, attribute masking) to the original synthesis graph to create several augmented views [27].

- Step 2 - Graph Encoding: Use a Graph Neural Network (GNN) encoder to generate node-level embeddings for both the original graph and the augmented views.

- Step 3 - Node-Level Difference Measurement: Employ a node discriminator to distinguish between original and augmented nodes. Calculate the precise difference for each node using cosine dissimilarity based on the feature and adjacency matrices [27].

- Step 4 - Contrastive Loss Calculation: Train the model using a loss function that pulls together embeddings of semantically similar nodes (positive pairs) and pushes apart dissimilar ones (negative pairs). The loss is constrained so that the distance between original and augmented nodes in the embedding space is proportional to their calculated cosine dissimilarity [27].

- Step 5 - Model Validation: Validate the model on a held-out test set containing known anomalous recipes. A successful model will rank these true anomalies higher than other candidates during a retrieval task.

Workflow and System Diagrams

Research Workflow for Anomaly-Driven Synthesis

GCL with Node-Level Difference Learning

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational and data "reagents" essential for research in this field.

| Research Reagent | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Text-Mined Synthesis Database | A structured dataset (e.g., in JSON format) of historical synthesis recipes, including precursors, targets, and operations, used to train the initial "normal" feature model [25]. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) Encoder | A model (e.g., Graph Convolutional Network) that transforms graph-structured synthesis data into a lower-dimensional vector space (embeddings) for analysis and comparison [27]. |

| Attention-Guided Perturbation Network | An auxiliary model that generates sample-aware attention masks to guide where to apply noise in the input data, promoting robust feature learning [26]. |

| Node Discriminator | A component within the GCL framework that learns to distinguish between nodes from the original graph and nodes from an augmented view, facilitating the measurement of fine-grained differences [27]. |

| Contrastive Loss Function | An objective function (e.g., InfoNCE) that trains the model by maximizing agreement between similar (positive) data pairs and minimizing agreement between dissimilar (negative) pairs [27]. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: For a research project with limited high-resolution (HR) training data, which generative model architecture is more suitable, and why?

A1: A Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) is often more suitable. GANs are known for their superior sample efficiency and can achieve impressive results with relatively fewer training samples [28]. Furthermore, once trained, they can generate samples in a single forward pass, making them faster for real-time or high-throughput applications [29] [28]. In practice, unsupervised GAN-based models have been successfully applied in domains like super-resolution of cultural heritage images where paired high-resolution and low-resolution data is unavailable [30].

Q2: Our conditional diffusion model generates images that are diverse but poorly align with the specific text prompt. What are the primary techniques to improve prompt adherence?

A2: Poor prompt adherence is often addressed by tuning the guidance scale. This is a parameter that controls the strength of the conditioning signal during the sampling process [31].

- Classifier-Free Guidance: This is the most common and effective technique. By training a model that can operate both conditionally and unconditionally (via conditioning dropout), you can use a guidance scale (γ) greater than 1 to sharpen the distribution and focus the output on the prompt. The sampling process is modified to use a barycentric combination:

score = (1 - γ) * unconditional_score + γ * conditional_score[31]. Cranking this scale up significantly improves adherence to the conditioning signal at a potential cost to sample diversity.

Q3: During training, our GAN's generator produces a limited variety of outputs, a phenomenon where the discriminator starts rejecting valid but less common samples. What is this issue and how can it be mitigated?

A3: This is a classic problem known as mode collapse [29] [28]. It occurs when the generator finds a few outputs that reliably fool the discriminator and fails to learn the full data distribution. Mitigation strategies include:

- Training Stability Techniques: Implementing methods like spectral normalization and gradient penalty (e.g., in WGAN-GP) can help stabilize the adversarial training [28].

- Architectural Adjustments: Using a two-stage reconstruction generator and applying an Exponential Moving Average (EMA) to the generator's parameters can produce a more stable variant, suppressing artifacts and improving output consistency [30].

Q4: What is "model collapse" and how does it relate to the long-term use of generative models in research pipelines?

A4: Model collapse is a degenerative process that occurs when successive generations of AI models are trained on data produced by previous models, rather than on original human-authored data [32] [33]. This leads to a narrowing of the model's "view of reality," where rare patterns and events in the data distribution vanish first, and outputs drift toward bland averages with reduced variance and potentially weird outliers [33]. For research, this poses a significant risk if synthetic data is used recursively for training without safeguards, as it can erode the diversity and novelty of generated molecular structures or other scientific data over time [34].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue: Diffusion model sampling is prohibitively slow for high-throughput screening of molecular structures.

- Solution: Investigate optimized samplers. The iterative denoising process of diffusion models is inherently slower than single-pass models [28]. To address this, research into faster samplers like DPM-Solver is ongoing. These solvers leverage the underlying differential equations of the diffusion process to reduce the number of required denoising steps (e.g., to around 10 steps) without a significant loss in quality [35].

Issue: A GAN-based super-resolution model introduces visual artifacts and distortions in the character regions of oracle bone rubbing images.

- Solution: Implement an artifact loss function. This specialized loss function measures the discrepancy between the outputs of a primary generator and a stabilized EMA generator variant. By explicitly penalizing these discrepancies during training, the model learns to suppress artifacts and distortions in critical regions, preserving the integrity of fine-grained structures [30].

Issue: A generative model for molecular design produces molecules with high predicted affinity but poor synthetic accessibility (SA).

- Solution: Integrate chemoinformatic oracles and active learning (AL) cycles. In a published drug discovery workflow, a Variational Autoencoder (VAE) generative model is refined through inner AL cycles. In these cycles, generated molecules are evaluated by computational predictors for drug-likeness and synthetic accessibility. Molecules meeting threshold criteria are used to fine-tune the model, iteratively guiding it towards the generation of more synthesizable compounds [34].

Quantitative Data and Performance Comparison

GANs vs. Diffusion Models: A Technical Comparison

Table 1: A comparative analysis of GANs and Diffusion Models across key technical aspects.

| Aspect | GANs (Generative Adversarial Networks) | Diffusion Models |

|---|---|---|

| Training Method | Adversarial game between generator & discriminator [29] [28] | Gradual denoising of noisy images [29] [28] |

| Training Stability | Unstable, prone to mode collapse and artifacts [29] [28] | Stable and predictable training [29] [28] |

| Inference Speed | Very fast (single forward pass) [29] [28] | Slower (multiple denoising steps) [29] [28] |

| Output Diversity | Can suffer from low diversity (mode collapse) [29] [28] | High diversity, strong prompt alignment [29] [28] |

| Best Use Cases | Real-time generation, super-resolution, data augmentation [29] [28] | Text-to-image, creative industries, scientific simulation [29] [28] |

Case Study: Quantifying Model Collapse in a Telehealth Service

Table 2: A hypothetical case study illustrating the impact of recursive training on model performance in a telehealth triage system. Data adapted from a model collapse analysis [33].

| Metric | Gen-0 (Baseline) | Gen-1 | Gen-2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training Mix | 100% human + guidelines | ~70% synthetic + 30% human | ~85% synthetic + 15% human |

| Notes with Rare-Condition Checklists | 22.4% | 9.1% | 3.7% |

| Accurate Triage — Rare, High-Risk Cases | 85% | 62% | 38% |

| 72-Hour Unplanned ED Visits | 7.8% | 10.9% | 14.6% |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: Active Learning-Driven Molecular Generation with a VAE

This protocol details a workflow for generating novel, drug-like molecules with high predicted affinity for a specific target, using a VAE integrated with active learning cycles [34].

- Data Representation: Represent training molecules as SMILES strings. Tokenize and convert them into one-hot encoding vectors for input into the VAE.

- Initial Training: Pre-train the VAE on a large, general molecular dataset to learn fundamental chemical rules. Then, perform initial fine-tuning on a target-specific training set.

- Inner AL Cycle (Chemical Optimization):

- Generation: Sample the VAE to produce new molecules.

- Evaluation: Filter generated molecules using chemoinformatic oracles for drug-likeness (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five), synthetic accessibility (SA), and dissimilarity from the current training set.

- Fine-tuning: Add molecules that pass the filters to a "temporal-specific" set. Use this set to fine-tune the VAE, steering it towards chemically favorable regions of the latent space. Repeat for a set number of iterations.

- Outer AL Cycle (Affinity Optimization):

- Evaluation: Take the accumulated molecules from the temporal-specific set and evaluate them using a physics-based oracle, specifically molecular docking simulations to predict binding affinity to the target.

- Fine-tuning: Transfer molecules with favorable docking scores to a "permanent-specific" set. Use this set for a major fine-tuning round of the VAE. Subsequent inner AL cycles will now assess similarity against this improved, affinity-enriched set.

- Candidate Selection: After multiple AL cycles, apply stringent filtration to the permanent-specific set. Use advanced molecular modeling simulations, such as Protein Energy Landscape Exploration (PELE) or Absolute Binding Free Energy (ABFE) calculations, to select top candidates for synthesis and experimental validation [34].

Protocol: Unsupervised Super-Resolution with a GAN (OBISR Model)

This protocol describes an unsupervised approach for enhancing the resolution of oracle bone rubbing images where paired low-resolution (LR) and high-resolution (HR) data is unavailable [30].

- Model Architecture: Employ a dual half-cycle architecture based on SCGAN, containing two degradation generators (GHL, GSL) and two super-resolution reconstruction generators (DTG, DTGEMA).

- First Half-Cycle (Synthetic Degradation):

- Input a real HR image (IHR) into the degradation generator GHL (along with a random noise vector z) to produce a synthetically degraded 4x downsampled LR image (ISL).

- Process ISL through both reconstruction generators (DTG and DTGEMA) to produce two reconstructed HR images (ISS and ISSEMA).