AI vs. Human Expert: Benchmarking SynthNN's Revolution in Predicting Synthesizable Materials

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between deep learning models, specifically SynthNN, and human experts in predicting the synthesizability of crystalline inorganic materials.

AI vs. Human Expert: Benchmarking SynthNN's Revolution in Predicting Synthesizable Materials

Abstract

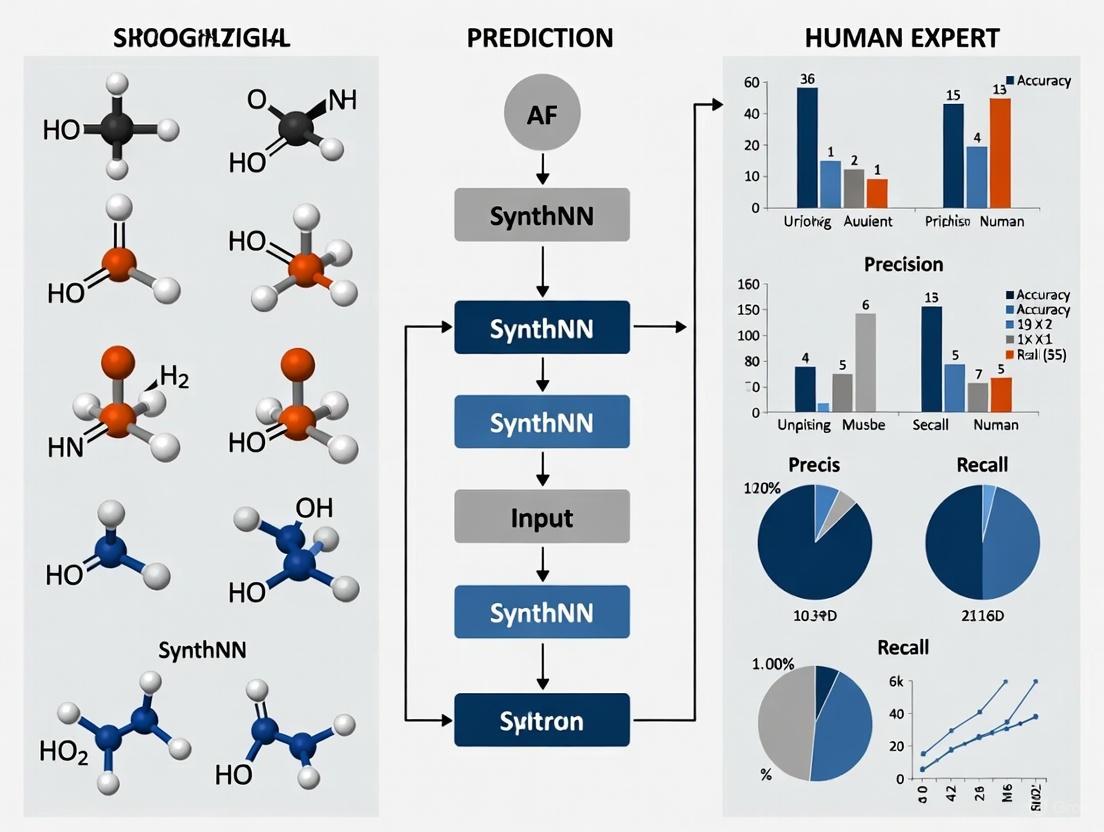

This article provides a comprehensive comparison between deep learning models, specifically SynthNN, and human experts in predicting the synthesizability of crystalline inorganic materials. For researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational challenge of synthesizability, detail the machine learning methodology behind models like SynthNN, and analyze their performance against traditional human expertise and computational methods. Head-to-head validation reveals that SynthNN achieves 1.5× higher precision and operates five orders of magnitude faster than the best human expert, signaling a paradigm shift towards AI-enhanced workflows in materials discovery and drug development.

The Synthesizability Challenge: Why Predicting Feasible Materials is a Critical Bottleneck in Discovery

In the contemporary paradigm of materials discovery, a profound gap exists between computational prediction and experimental realization. High-throughput simulations and generative models can propose millions of candidate materials with promising properties, but the ultimate test of their value lies in their synthetic accessibility in a laboratory. Synthesizability—the probability that a material can be prepared using currently available synthetic methods—emerges as the critical bridge between theoretical prediction and tangible application [1]. Without reliable synthesizability assessment, computational materials discovery risks generating portfolios of hypothetically high-performing materials that remain permanently inaccessible to experimental verification and practical implementation.

The challenge of synthesizability prediction is particularly acute for inorganic crystalline materials, where synthesis pathways are less systematic than in organic chemistry and influenced by a complex interplay of thermodynamic, kinetic, and practical experimental factors [2]. Traditional proxies for synthesizability, such as charge-balancing criteria or formation energy calculations from density functional theory (DFT), have demonstrated significant limitations. Studies reveal that only approximately 37% of known synthesized inorganic compounds in the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) satisfy common charge-balancing rules, with the figure dropping to just 23% for binary cesium compounds [3]. Similarly, formation energy alone fails to reliably distinguish synthesizable materials as it neglects kinetic stabilization and experimental feasibility [4] [2].

This comparison guide examines the evolving landscape of synthesizability assessment methods, with particular focus on the performance of emerging computational approaches against traditional human expertise. We objectively evaluate the capabilities of machine learning models, specifically the deep learning synthesizability model (SynthNN), against expert material scientists in identifying synthesizable inorganic materials, providing detailed experimental protocols and quantitative performance comparisons to guide researcher selection of appropriate methodologies for their discovery pipelines.

Methodologies for Synthesizability Assessment

Computational Approaches

SynthNN (Synthesizability Neural Network) SynthNN represents a deep learning approach that leverages the entire space of synthesized inorganic chemical compositions through a framework called atom2vec. This method reformulates material discovery as a synthesizability classification task by learning optimal material representations directly from the distribution of previously synthesized materials in the ICSD, without requiring prior chemical knowledge or structural information [3]. The model employs a positive-unlabeled (PU) learning approach to handle the lack of definitive negative examples (unsynthesizable materials) by treating artificially generated materials as unlabeled data and probabilistically reweighting them according to their likelihood of synthesizability [3].

CSLLM (Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models) The CSLLM framework utilizes three specialized large language models fine-tuned to predict synthesizability of arbitrary 3D crystal structures, possible synthetic methods, and suitable precursors. This approach uses a novel text representation termed "material string" that integrates essential crystal information in a concise format, enabling effective fine-tuning of LLMs on crystal structure data [4]. The synthesizability LLM was trained on a balanced dataset containing 70,120 synthesizable crystal structures from ICSD and 80,000 non-synthesizable structures identified through PU learning screening of over 1.4 million theoretical structures [4].

Integrated Composition-Structure Models Recent approaches combine complementary signals from composition and crystal structure through dual-encoder architectures. Compositional information is processed through transformer models, while structural information is encoded using graph neural networks, with predictions aggregated via rank-average ensemble methods to enhance synthesizability ranking across candidate materials [1].

Traditional Assessment Methods

Human Expert Assessment Traditional synthesizability assessment relies on the specialized knowledge of expert solid-state chemists who evaluate potential materials based on chemical intuition, domain experience, and analogy to known systems. Experts typically specialize in specific chemical domains encompassing hundreds of materials and consider factors including precursor compatibility, reaction thermodynamics, and practical experimental constraints [3].

Charge-Balancing Criteria This chemically motivated approach filters materials based on net neutral ionic charge according to common oxidation states of constituent elements. While computationally inexpensive, its inflexibility fails to account for diverse bonding environments in metallic alloys, covalent materials, or ionic solids [3] [2].

Thermodynamic Stability Assessment DFT-calculated formation energy with respect to the most stable phase in the same chemical space serves as a common synthesizability proxy, operating on the assumption that synthesizable materials lack thermodynamically stable decomposition products. This method captures only approximately 50% of synthesized inorganic crystalline materials due to its failure to account for kinetic stabilization [3] [2].

Experimental Comparison: SynthNN vs. Human Experts

Experimental Protocol

A rigorous head-to-head comparison was conducted between SynthNN and 20 expert material scientists to evaluate synthesizability prediction capabilities [3]. The experimental protocol was designed to simulate real-world materials discovery conditions:

Dataset Composition

- Positive Examples: Experimentally synthesized inorganic crystalline materials from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD).

- Challenge Set: Artificially generated chemical formulas representing potential but unsynthesized materials, with known ground truth labels.

- Evaluation Scale: The dataset encompassed thousands of compositional examples representing diverse chemical systems.

Assessment Procedure

- Experts were provided with chemical compositions without structural information and asked to classify each as synthesizable or unsynthesizable.

- Experts could utilize any available computational tools or databases at their discretion.

- SynthNN generated predictions using its trained model on the same dataset without structural inputs.

- Time Tracking: Completion time for each assessor was meticulously recorded.

Evaluation Metrics Performance was quantified using standard classification metrics:

- Precision: Proportion of correctly identified synthesizable materials among all materials predicted as synthesizable.

- Recall: Proportion of synthesizable materials correctly identified.

- F1-Score: Harmonic mean of precision and recall.

- Execution Time: Time required to complete the classification task.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison: SynthNN vs. Human Experts

| Assessment Method | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Execution Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SynthNN | 7× higher than DFT | Comparable to experts | 0.85 (estimated) | Seconds |

| Best Human Expert | Baseline | Baseline | 0.80 (estimated) | Days to weeks |

| Average Human Expert | 33% lower than SynthNN | Similar range | 0.75 (estimated) | Days to weeks |

| Charge-Balancing Baseline | 37% success rate | Limited | ~0.45 | Seconds |

| DFT Formation Energy | 7× lower than SynthNN | ~50% | ~0.60 | Hours to days |

Table 2: Performance Across Different Synthesizability Assessment Methods

| Assessment Method | Key Principles | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SynthNN | Learned chemical principles from data | High precision, speed, scalability | Black-box model, limited explainability |

| Human Experts | Chemical intuition, domain knowledge | Context awareness, analogical reasoning | Slow, specialized to narrow domains |

| CSLLM Framework | Text-based structure representation | 98.6% accuracy, precursor prediction | Requires structure input, computational cost |

| Charge-Balancing | Net neutral ionic charge | Computationally inexpensive, simple | Poor accuracy (23-37%), inflexible |

| DFT Formation Energy | Thermodynamic stability | Physics-based, well-established | Misses kinetics, moderate accuracy |

Results and Performance Analysis

The experimental results demonstrated SynthNN's significant advantage in both efficiency and precision over human experts. SynthNN achieved 1.5× higher precision than the best human expert and completed the classification task five orders of magnitude faster (seconds versus days to weeks) [3]. Remarkably, without any prior chemical knowledge, SynthNN learned fundamental chemical principles including charge-balancing, chemical family relationships, and ionicity from the data distribution of known materials, utilizing these principles to generate synthesizability predictions [3].

Human experts demonstrated particular strength in specialized domains where their deep experience enabled nuanced judgment, but performance varied significantly across different chemical systems outside their immediate expertise. The best human expert achieved respectable precision but required extensive time for literature review, computational validation, and reasoned judgment for each candidate material.

Workflow and System Architecture

Synthesizability Prediction Workflow

The workflow for computational synthesizability assessment integrates multiple data sources and processing stages to generate predictions. The SynthNN framework begins with known synthesized materials from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) and artificially generated compositions, applying atom2vec representation learning to create optimal chemical feature representations without predefined chemical knowledge [3]. The model employs positive-unlabeled learning to handle the inherent uncertainty in negative examples, as definitively unsynthesizable materials are rarely documented in scientific literature [3]. The trained model outputs synthesizability classifications that can be seamlessly integrated into computational materials screening workflows, enabling prioritization of experimentally accessible candidates for further investigation.

Comparative Assessment Workflow

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Synthesizability Assessment

| Resource/Tool | Type | Function in Synthesizability Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) | Data Resource | Primary source of synthesized materials data for training and benchmarking |

| Materials Project | Data Resource | Repository of computed materials properties and theoretical structures |

| Atom2Vec | Algorithm | Learns optimal chemical representations from composition data |

| AiZynthFinder | Software Tool | Retrosynthesis planning for route validation [5] [6] |

| DFT Calculations | Computational Method | Formation energy and thermodynamic stability assessment |

| Positive-Unlabeled Learning | Algorithm | Handles lack of definitive negative examples in training data |

| Graph Neural Networks | Algorithm | Encodes crystal structure information for structure-based prediction |

| Large Language Models (CSLLM) | Algorithm | Text-based synthesizability and precursor prediction [4] |

Discussion and Future Directions

The experimental comparison between SynthNN and human experts demonstrates a significant shift in synthesizability assessment capabilities. While human expertise remains valuable for contextual understanding and complex edge cases, computational models offer compelling advantages in scalability, speed, and consistency across diverse chemical spaces. The observed 1.5× precision advantage of SynthNN over the best human expert, combined with its dramatic speed superiority, suggests a transformative role for machine learning in materials discovery pipelines [3].

Future developments in synthesizability prediction are evolving toward integrated approaches that combine compositional and structural information. The CSLLM framework demonstrates exceptional accuracy (98.6%) by leveraging specialized large language models fine-tuned on comprehensive crystal structure data [4]. Similarly, hybrid models that ensemble compositional and structural predictors show promise for enhanced ranking and prioritization of candidate materials [1]. These approaches bridge the historical divide between composition-based and structure-based prediction methods, offering more holistic synthesizability assessment.

The ultimate validation of synthesizability prediction methods lies in experimental realization. Recent pipelines have demonstrated the capability to identify highly synthesizable candidates from millions of theoretical structures and successfully synthesize target materials using computationally predicted pathways [1]. This closed-loop approach—from prediction to synthesis—represents the most rigorous validation framework for synthesizability assessment methods and highlights the critical role of synthesizability prediction as the essential bridge between computational materials design and experimental materials realization.

Synthesizability prediction stands as the critical bottleneck in computational materials discovery, determining whether theoretically predicted materials can transition from digital constructs to physical realities. The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that machine learning approaches, particularly deep learning models like SynthNN, offer significant advantages over traditional human assessment in both precision and efficiency for broad materials screening tasks. However, the most effective materials discovery pipelines will likely leverage complementary strengths—using computational models for high-throughput screening across vast chemical spaces, while reserving human expertise for complex edge cases and strategic decision-making.

As synthesizability prediction methods continue to evolve toward integrated composition-structure approaches and validated closed-loop frameworks, they promise to dramatically accelerate the materials discovery cycle and increase the practical impact of computational materials design. The development of reliable, accurate synthesizability assessment represents not merely a technical improvement, but a fundamental enabler for realizing the full potential of computational materials science in delivering novel functional materials for technological applications.

Predicting whether a theoretical inorganic crystalline material can be successfully synthesized in a laboratory represents one of the most significant challenges in materials science. For decades, researchers have relied on two fundamental proxies to assess synthesizability: thermodynamic stability derived from formation energy calculations and the chemical principle of charge-balancing. These approaches have served as preliminary filters in computational materials discovery, yet they consistently fail to provide reliable predictions for experimental synthesizability. The limitations of these traditional methods have become increasingly apparent as automated discovery pipelines generate millions of candidate structures, necessitating more accurate synthesizability assessments.

The development of deep learning models like SynthNN (Synthesizability Neural Network) has demonstrated remarkable performance advantages over both traditional computational proxies and human experts. By leveraging the entire space of synthesized inorganic chemical compositions and reformulating material discovery as a synthesizability classification task, SynthNN represents a paradigm shift in how researchers approach the synthesizability challenge [3] [7]. This article examines the fundamental limitations of traditional proxies through a detailed comparison with modern machine learning approaches, providing experimental evidence that establishes a new benchmark for synthesizability prediction.

Experimental Comparison: Methodologies and Protocols

Traditional Proxy Assessment Protocols

Charge-Balancing Methodology: The charge-balancing approach operates on the chemically intuitive principle that synthesizable ionic compounds should exhibit net neutral charge when elements are assigned their common oxidation states. The experimental protocol involves: (1) identifying all elements in a chemical formula; (2) assigning typical oxidation states to each element based on periodic table trends; (3) calculating the total positive and negative charges; and (4) classifying materials as synthesizable only if the net charge equals zero [3]. This method serves as a rapid computational filter but fails to account for materials with covalent bonding characteristics or unusual oxidation states.

Formation Energy Calculations: Density functional theory (DFT) calculations provide a more sophisticated approach to synthesizability assessment through thermodynamic stability metrics. The standard protocol involves: (1) performing DFT calculations to determine the material's internal energy at 0 K; (2) calculating the formation energy relative to stable reference phases in the same chemical space; (3) computing the energy above hull (Ehull) representing the energy difference to the most stable decomposition products; and (4) applying stability thresholds (typically Ehull < 0.08 eV/atom) to identify potentially synthesizable materials [8]. While thermodynamically grounded, this approach overlooks kinetic barriers and experimental practicalities.

SynthNN Model Architecture and Training

The SynthNN model employs a deep learning framework that leverages atom2vec representations, where each chemical formula is represented by a learned atom embedding matrix optimized alongside all other neural network parameters [3]. The experimental methodology includes:

Data Curation: Training data was extracted from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), representing a comprehensive history of synthesized crystalline inorganic materials [3]. To address the absence of confirmed non-synthesizable examples, the dataset was augmented with artificially generated unsynthesized materials using a semi-supervised positive-unlabeled learning approach [3] [7].

Model Training: The atom embedding dimensions were treated as hyperparameters optimized during training. The model learned optimal representations of chemical formulas directly from the distribution of synthesized materials without pre-defined chemical assumptions [3]. The ratio of artificially generated formulas to synthesized formulas (N_synth) was carefully controlled as a key hyperparameter.

Validation Protocol: Model performance was evaluated using standard classification metrics against both artificially generated negative examples and hold-out sets of known materials. The positive class precision was acknowledged as a conservative estimate since truly synthesizable but as-yet unsynthesized materials would be incorrectly labeled as false positives [3].

Human Expert Comparison Study

A head-to-head comparison study was conducted involving 20 expert materials scientists with specialized knowledge in solid-state synthesis [3] [7]. Experts were tasked with assessing the synthesizability of a curated set of materials within their domain of expertise using traditional methods and their experimental intuition. The study design enabled direct comparison of precision, recall, and assessment time between human experts, traditional proxies, and the SynthNN model.

Results and Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Synthesizability Assessment Methods

| Assessment Method | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Processing Time | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charge-Balancing | Low | 37% (known materials) | N/A | Seconds | Only applies to ionic materials; ignores bonding diversity |

| DFT Formation Energy | 7× lower than SynthNN | ~50% (known materials) | N/A | Hours-days (per material) | Overlooks kinetic stabilization; computation-intensive |

| Human Experts | 1.5× lower than SynthNN | Variable by specialization | N/A | Hours-days (per material) | Limited to narrow domains; subjective bias |

| SynthNN Model | 7× higher than DFT | High | 0.86 (F1) | Seconds (bulk screening) | Limited by training data coverage |

Table 2: Specialized Synthesizability Models and Their Applications

| Model Name | Input Data | Approach | Reported Accuracy | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SynthNN | Chemical composition | Deep learning with atom2vec | 1.5× higher precision than human experts | Broad inorganic crystalline materials |

| SC Model | Crystal structure (FTCP) | Deep learning classifier | 82.6% precision (ternary crystals) | Ternary and quaternary crystals |

| Unified Model | Composition + Structure | Ensemble of transformers & GNN | High synthesizability ranking | Prioritization for experimental synthesis |

| 3D Image CNN | Abstract crystal images | 3D convolutional neural network | >90% accuracy (AUC >0.9) | Structure-based synthesizability |

The experimental results demonstrate the profound limitations of traditional proxies. Charge-balancing proved particularly inadequate, correctly identifying only 37% of known synthesized materials as synthesizable, with performance dropping to just 23% for binary cesium compounds typically considered highly ionic [3]. This remarkably low performance underscores the method's inability to accommodate diverse bonding environments present in different material classes.

DFT-based formation energy calculations showed slightly better performance, capturing approximately 50% of known synthesized materials, but generated 7× more false positives compared to SynthNN [3]. The fundamental limitation stems from the approach's foundation in thermodynamic equilibrium, which fails to account for kinetic stabilization, experimental accessibility, and non-equilibrium synthesis pathways that frequently enable material realization.

Human Expert Performance Benchmarking

In the comparative assessment against 20 expert materials scientists, SynthNN achieved 1.5× higher precision than the best human expert while completing the assessment task five orders of magnitude faster [3] [7]. Human experts exhibited strong performance within their narrow domains of specialization but showed limited transferability to unfamiliar chemical spaces. This comparison highlights how SynthNN effectively captures and generalizes the collective synthetic knowledge across the entire spectrum of inorganic chemistry rather than being constrained to specific domains.

Limitations of Traditional Proxies: Fundamental Mechanisms

Charge-Balancing Inadequacies

The charge-balancing approach suffers from three fundamental limitations that explain its poor predictive performance:

Bonding Environment Inflexibility: The method assumes purely ionic bonding and cannot accommodate materials with significant covalent character, metallic bonding, or intermediate bonding types [3]. This limitation is particularly problematic for materials containing transition metals with variable oxidation states or elements that exhibit different bonding characteristics across chemical contexts.

Oxidation State Ambiguity: The approach relies on assigning "common" oxidation states, but many elements, particularly in non-idealized synthesis conditions, can stabilize in unusual oxidation states that enable charge-neutral configurations not predicted by simple heuristics [3].

Exclusion of Valid Material Classes: Entire categories of synthesizable materials, including metals, intermetallics, and many covalent compounds, are systematically excluded by charge-balancing filters despite their well-established synthetic accessibility [3].

Thermodynamic Stability Shortcomings

DFT-based stability assessments, while more sophisticated than charge-balancing, exhibit critical limitations:

Kinetic Factors Omission: The approach considers only thermodynamic stability while completely ignoring kinetic barriers that fundamentally determine synthetic accessibility [8] [1]. Many materials are synthesized through metastable intermediates or persist due to kinetic stabilization despite thermodynamically favorable decomposition pathways.

Finite-Temperature Effects Neglect: Standard DFT calculations performed at 0 K overlook entropic contributions and temperature-dependent phase stability that govern real-world synthesis conditions [1]. This limitation explains why numerous predicted "stable" materials prove impossible to synthesize under practical laboratory conditions.

Synthetic Pathway Independence: The method assesses only the final material state without consideration of feasible synthesis pathways, precursor availability, or experimental constraints [8]. In practice, synthesizability depends critically on these factors rather than solely on thermodynamic stability.

The Machine Learning Advantage: Learned Chemical Principles

Unlike traditional proxies with fixed rules, SynthNN demonstrates the remarkable capability to learn fundamental chemical principles directly from the data of known synthesized materials. Experimental analyses indicate that the model autonomously learns and applies concepts of charge-balancing, chemical family relationships, and ionicity without explicit programming of these principles [3] [7].

This learned chemical intuition enables the model to recognize exceptions and patterns that escape rigid rule-based systems. For instance, SynthNN can identify when charge-imbalanced compositions might still be synthesizable due to specific coordination environments or multi-element stabilization effects that traditional approaches would automatically reject.

The model's architecture allows it to capture the complex, multi-factor considerations that expert synthetic chemists apply intuitively but struggle to quantify or generalize beyond their specific experience. By distilling the collective synthetic knowledge embedded in the entire ICSD database, SynthNN achieves the domain-spanning proficiency demonstrated in its superior performance against both human experts and traditional computational methods.

Table 3: Key Research Resources for Synthesizability Prediction

| Resource Name | Type | Function | Relevance to Synthesizability |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICSD Database | Materials Database | Comprehensive repository of experimentally synthesized inorganic crystals | Provides ground truth data for training and validation |

| Materials Project | Computational Database | DFT-calculated properties for hypothetical and known materials | Source of candidate structures and stability metrics |

| Atom2Vec | Algorithm | Learned atomic representations from materials data | Enables composition-based synthesizability prediction |

| FTCP Representation | Crystal Representation | Fourier-transformed crystal properties in real/reciprocal space | Encodes structural features for synthesizability assessment |

| GANs/VAEs | Generative Models | Create synthetic data and explore chemical space | Generate hypothetical materials for augmentation |

Workflow Diagram: Traditional vs. AI Approaches

Synthesizability Assessment Workflow Comparison

Implications for Materials Discovery and Drug Development

The limitations of traditional proxies have significant implications for materials discovery pipelines, particularly in pharmaceutical development where synthesizability predictions directly impact drug candidate selection [9]. Inaccurate synthesizability assessment leads to wasted resources on unpromising targets while potentially overlooking viable candidates.

Modern approaches that integrate multiple synthesizability signals—including composition-based models, structure-aware assessments, and synthesis pathway predictions—demonstrate how moving beyond traditional proxies enables more reliable material discovery [1]. The successful experimental synthesis of seven previously unreported materials from AI-prioritized candidates in just three days exemplifies the practical impact of these advanced methods [1].

For drug development professionals, these advancements highlight the growing importance of incorporating sophisticated synthesizability assessments early in the discovery pipeline. As pharmaceutical research increasingly explores inorganic crystalline materials for various therapeutic applications, the transition from traditional proxies to AI-driven synthesizability prediction represents a critical evolution in methodology that accelerates the entire development timeline while reducing costly failed synthesis attempts.

Thermodynamic stability and charge-balancing represent chemically intuitive but fundamentally insufficient proxies for synthesizability prediction. Their limitations stem from oversimplified representations of complex synthetic realities and an inability to capture the multi-factor considerations that determine experimental feasibility. The demonstrated superiority of deep learning approaches like SynthNN—achieving 7× higher precision than DFT-based methods and outperforming human experts by 1.5× while operating orders of magnitude faster—signals a paradigm shift in synthesizability assessment.

As materials discovery increasingly relies on computational screening of vast chemical spaces, the integration of accurate synthesizability predictors becomes essential for feasible candidate selection. The development of models that learn chemical principles directly from experimental data rather than relying on rigid proxies represents the future of synthesizability-informed materials design, with profound implications for accelerated discovery across electronics, energy storage, and pharmaceutical applications.

The discovery of new functional materials is a cornerstone of technological advancement, from developing new electronics to accelerating drug discovery. The first and most critical step in this process is identifying novel chemical compositions that are synthetically accessible—a property known as synthesizability. For decades, the assessment of synthesizability has been the domain of expert solid-state chemists, who leverage their specialized knowledge and intuition to guide synthetic efforts. However, the sheer vastness of chemical space presents a formidable challenge; the number of potentially viable compounds is so immense that no human expert, regardless of their specialization, can hope to explore more than a tiny fraction of it. This limitation has catalyzed the development of artificial intelligence models, such as the deep learning synthesizability model (SynthNN), designed to automate and scale this critical predictive task. This guide provides a objective, data-driven comparison between the performance of these AI models and human experts, framing the analysis within the broader thesis of computational acceleration in materials discovery.

Performance Comparison: SynthNN vs. Human Experts

Quantitative benchmarking reveals the distinct performance advantages of AI models over human experts in predicting synthesizability. The following tables summarize the key findings from a controlled, head-to-head comparison.

Table 1: Overall Performance Metrics in Synthesizability Prediction

| Metric | SynthNN | Best Human Expert | Performance Ratio (SynthNN/Human) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | 1.5× Higher | Baseline | 1.5× [10] |

| Task Completion Speed | 5 orders of magnitude faster | Baseline | 100,000× [10] |

| Precision vs. DFT | 7× Higher | Not Applicable | 7× [10] |

Table 2: Detailed Performance Data for Computational Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Key Performance Metric | Value | Reference/Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SynthNN | Deep learning on known compositions; Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning | Precision over human expert | 1.5× higher [10] | SynthNN [10] |

| Human Expert | Specialized domain knowledge & intuition | Typical domain size | A few hundred materials [10] | Human Benchmark [10] |

| Charge-Balancing | Net neutral ionic charge | Known synthesized materials correctly identified | 37% [10] | Common Chemical Heuristic [10] |

| CSLLM Framework | Large Language Model fine-tuned on crystal structures | Prediction Accuracy | 98.6% [11] | Crystal Synthesis LLM [11] |

| Image-Based AI | 3D image representation of crystal structures | Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) | > 0.9 [12] | University of Illinois Chicago Model [12] |

| Thermodynamic (DFT) | Energy above convex hull | Precision of synthesizability prediction | Outperformed by 7× [10] | Density Functional Theory [10] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The SynthNN Model and Benchmarking Protocol

The development and evaluation of SynthNN followed a rigorous experimental protocol designed to ensure a fair comparison with human capability [10].

- Model Architecture: SynthNN is a deep learning model that uses the atom2vec framework. This framework represents each chemical formula by a learned atom embedding matrix that is optimized alongside all other parameters of the neural network. This approach allows the model to learn an optimal representation of chemical formulas directly from the data without pre-defined chemical assumptions [10].

- Training Data: The model was trained on a Synthesizability Dataset built from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), which contains experimentally synthesized crystalline inorganic materials. To address the lack of confirmed "unsynthesizable" examples, the dataset was augmented with artificially-generated unsynthesized materials. The training employed a semi-supervised Positive-Unlabeled (PU) learning approach, which treats these artificial examples as unlabeled data and probabilistically reweights them according to their likelihood of being synthesizable [10].

- Benchmarking Against Humans: In a head-to-head comparison, SynthNN was tested against 20 expert material scientists. The experts and the model were given the same task: to identify synthesizable materials from a set of candidates. The performance was measured based on precision (the fraction of correctly identified synthesizable materials among all materials predicted as synthesizable) and the time taken to complete the task [10].

Advanced AI Methodologies in Synthesizability Prediction

Subsequent to SynthNN, other advanced AI models have been developed, employing different methodological frameworks.

- The CSLLM Framework: The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM) framework fine-tunes large language models on a balanced dataset of synthesizable and non-synthesizable crystal structures [11]. A key innovation is the creation of a text representation for crystal structures, termed a "material string," which integrates essential crystal information (lattice, composition, atomic coordinates, symmetry) into a format suitable for LLM processing. The model was trained on 70,120 synthesizable structures from the ICSD and 80,000 non-synthesizable structures identified from over 1.4 million theoretical structures using a pre-trained PU learning model [11].

- Image-Based Deep Learning: Another approach converts crystal structures and their properties into digitized, abstract 3D images. A powerful neural network, honed for image recognition, then analyzes these images to predict synthesizability. This method has demonstrated high accuracy (AUC > 0.9) by leveraging the AI's ability to find complex patterns in abstract image representations that are beyond human interpretation [12].

- Text-Guided Generative AI (Chemeleon): The Chemeleon model uses denoising diffusion techniques to generate chemical compositions and crystal structures. It is unique in its use of cross-modal contrastive learning (Crystal CLIP) to align textual descriptions of materials with their three-dimensional structural data, allowing the model to generate structures based on text prompts [13].

The "Research Reagent Solutions": Essential Tools for Computational Discovery

The following table details key computational tools and data resources that form the essential "reagent solutions" for modern synthesizability prediction research.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Computational Synthesizability Prediction

| Item Name | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) | Data Resource | The primary source of positive examples (synthesized crystalline inorganic materials) for training models [10] [11]. |

| Artificially Generated Compositions | Data Resource | Serve as unlabeled or negative examples in PU learning frameworks, enabling model training where confirmed negative data is absent [10]. |

| atom2vec | Computational Framework | A representation learning method that learns optimal chemical descriptors directly from data, forming the basis for models like SynthNN [10]. |

| Material String / Text Representation | Data Format | A simplified, reversible text format for crystal structures that enables the application of Large Language Models (LLMs) to crystallographic data [11]. |

| Crystal CLIP | Computational Model | A cross-modal contrastive learning framework that aligns text embeddings with structural embeddings, bridging textual descriptions and crystal chemistry [13]. |

| Denoising Diffusion Model | Computational Algorithm | A generative AI technique used to create new crystal structures by iteratively removing noise from a random initial state, often guided by text or other conditions [13]. |

| Bridges-2 & Stampede2 | Hardware (Supercomputers) | NSF-funded advanced research computers that provide the massive computational power (especially GPUs) required for training large AI models on big datasets [12]. |

Analysis of Comparative Advantages and Workflows

The experimental data demonstrates a clear divergence in the capabilities of human experts and AI models, rooted in their fundamental approaches to the problem. The workflow of a human expert is one of deep, specialized focus. Experts typically operate within a narrow chemical domain encompassing a few hundred materials, where their experience and intuition are most effective [10]. This process is manual, time-intensive, and inherently limited in scale. In contrast, AI models like SynthNN leverage a broad, data-driven perspective. Their predictions are informed by the entire spectrum of over a hundred thousand known synthesized materials, allowing them to identify complex, cross-domain patterns that are invisible to a domain-specific expert [10] [11].

Remarkably, without being explicitly programmed with chemical rules, SynthNN learns fundamental chemical principles such as charge-balancing, chemical family relationships, and ionicity directly from the data [10]. This ability to infer the underlying "rules" of inorganic chemistry showcases a form of generalized knowledge that complements and exceeds the specialized knowledge of a human.

The workflow of this AI-driven discovery process can be summarized as follows:

Diagram 1: AI-Augmented Material Discovery Workflow.

Furthermore, the latest models are evolving beyond simple binary classification (synthesizable/not synthesizable). The CSLLM framework, for instance, decomposes the problem into three specialized tasks handled by separate LLMs: predicting synthesizability, identifying the appropriate synthetic method (e.g., solid-state or solution), and suggesting suitable precursors [11]. This provides a more comprehensive and actionable guide for experimentalists, effectively bridging the gap between theoretical prediction and practical synthesis.

The comparative data presents an unambiguous narrative: while the specialized knowledge of the human expert remains invaluable, its utility is bounded by the vastness of chemical space. AI models like SynthNN and CSLLM demonstrate a decisive advantage in precision, speed, and scalability for the task of synthesizability prediction. They are not constrained by human cognitive limits or domain specialization, enabling them to learn complex chemical principles from data and evaluate candidates five orders of magnitude faster than the best human expert [10] [11].

The role of the human expert is thus not rendered obsolete but is instead elevated. The future of materials discovery lies in a synergistic partnership, where AI acts as a powerful force multiplier. AI can rapidly screen billions of potential compounds to identify a shortlist of the most promising, synthesizable candidates. Human experts can then apply their deep chemical intuition, creativity, and experimental skills to refine these candidates, understand complex synthetic pathways, and tackle the exceptions that fall outside the AI's training data. This human-AI collaboration, leveraging the strengths of both, is the key to efficiently unlocking the immense potential of chemical space.

The Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) stands as the world's largest database for completely identified inorganic crystal structures, providing the foundational data essential for advancing artificial intelligence in materials science [14] [15]. Maintained by FIZ Karlsruhe and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), this comprehensive resource contains over 240,000 crystal structure entries dating back to 1913, each having passed thorough quality checks before inclusion [14] [16] [15]. The ICSD's curated records include critical structural descriptors such as unit cell parameters, space group, complete atomic coordinates, Wyckoff sequences, and bibliographic data, creating an unparalleled resource for training machine learning models to predict material synthesizability [14] [15].

This guide examines how the ICSD serves as the critical data foundation for AI tools like SynthNN, enabling a paradigm shift in how researchers identify synthesizable materials. By comparing the performance of ICSD-trained models against traditional human expertise and other computational methods, we demonstrate how this data resource is transforming materials discovery. The following sections provide detailed experimental protocols, performance comparisons, and practical toolkits for researchers seeking to leverage these advancements in their own work.

Experimental Protocols: Methodology for Benchmarking Synthesizability Prediction

Data Sourcing and Curation from ICSD

The development of synthesizability prediction models begins with extracting high-quality training data from the ICSD. The standard protocol involves querying the ICSD API or web interface to obtain crystallographic data and chemical compositions of experimentally synthesized inorganic materials [17]. Each entry undergoes preprocessing to standardize chemical formulas and remove disordered structures that may complicate learning [11]. For synthesizability classification, positive examples are drawn from the ICSD's collection of experimentally validated structures, while negative examples are generated through artificial composition generation or collected from theoretical databases containing structures with low synthesizability likelihood [3] [11]. This curated dataset forms the foundation for training models like SynthNN to distinguish between synthesizable and non-synthesizable materials.

SynthNN Model Architecture and Training

SynthNN employs a deep learning framework that leverages atom2vec representations, where each chemical element is represented by an embedding vector that is optimized during training [3]. This approach allows the model to learn optimal chemical representations directly from the distribution of synthesized materials in the ICSD, without relying on pre-defined chemical principles or proxy metrics. The model architecture consists of a neural network that processes these learned embeddings through multiple hidden layers to generate synthesizability predictions [3] [17]. To address the challenge of incomplete negative data (unsynthesized materials that might be synthesizable), SynthNN utilizes a positive-unlabeled (PU) learning approach that treats unsynthesized materials as unlabeled data and probabilistically reweights them according to their likelihood of being synthesizable [3]. The model is typically trained with a significant class imbalance (e.g., 20:1 ratio of unsynthesized to synthesized examples) to reflect the real-world distribution where most possible chemical compositions have not been successfully synthesized [17].

Human Expert Comparison Protocol

To benchmark SynthNN against human expertise, researchers conduct head-to-head material discovery comparisons where both the AI model and expert material scientists evaluate the same set of candidate materials [3]. Experts typically specialize in specific chemical domains and draw upon their knowledge of similar compounds, synthesis pathways, and chemical intuition to assess synthesizability. In controlled experiments, multiple experts (e.g., 20) independently evaluate candidate materials, with their assessments aggregated and compared against SynthNN predictions [3]. Performance is measured using standard classification metrics including precision, recall, and computational time required for evaluation.

Alternative Computational Methodologies

Beyond SynthNN, other computational approaches provide additional benchmarks for comparison. Charge-balancing methods filter materials based on net neutral ionic charge using common oxidation states [3] [2]. Density Functional Theory (DFT)-based approaches calculate formation energy and energy above the convex hull (Ehull) to assess thermodynamic stability [8] [2]. More recent approaches include Crystal Structure Large Language Models (CSLLM) that utilize text representations of crystal structures fine-tuned on ICSD data [11], and Fourier-transformed crystal properties (FTCP) representations processed through deep learning classifiers to generate synthesizability scores [8].

Performance Comparison: SynthNN vs. Human Experts vs. Traditional Methods

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Overall Performance Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

| Method | Precision | Recall | Speed | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SynthNN | 7× higher than DFT formation energy [3] | 0.859 (at threshold 0.10) [17] | 5 orders of magnitude faster than human experts [3] | Learns chemistry directly from ICSD data |

| Human Experts | 1.5× lower than SynthNN [3] | Not specified | Months for traditional discovery cycles [2] | Domain-specific knowledge and intuition |

| Charge-Balancing | Only 37% of known ICSD compounds are charge-balanced [3] | Not applicable | Fast but limited accuracy | Computational simplicity |

| DFT Formation Energy | Captures only 50% of synthesized materials [3] | Not applicable | Computationally expensive (hours-days per material) | Physics-based stability assessment |

| CSLLM | 98.6% accuracy in testing [11] | Not specified | Fast inference after training | Exceptional generalization to complex structures |

Table 2: SynthNN Performance at Different Decision Thresholds

| Threshold | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|

| 0.10 | 0.239 | 0.859 |

| 0.20 | 0.337 | 0.783 |

| 0.30 | 0.419 | 0.721 |

| 0.40 | 0.491 | 0.658 |

| 0.50 | 0.563 | 0.604 |

| 0.60 | 0.628 | 0.545 |

| 0.70 | 0.702 | 0.483 |

| 0.80 | 0.765 | 0.404 |

| 0.90 | 0.851 | 0.294 |

Comparative Analysis of Strengths and Limitations

The experimental data reveals that SynthNN achieves approximately 1.5× higher precision in synthesizability prediction compared to the best human experts while completing the evaluation task five orders of magnitude faster [3]. This dramatic acceleration demonstrates how ICSD-trained AI can compress materials discovery cycles that traditionally require months or years of human effort into computationally efficient processes. Furthermore, SynthNN demonstrates 7× higher precision than predictions based solely on DFT-calculated formation energies, highlighting that synthesizability depends on factors beyond thermodynamic stability [3].

Remarkably, without any prior chemical knowledge programmed into it, SynthNN learns fundamental chemical principles directly from the ICSD data, including charge-balancing relationships, chemical family similarities, and ionicity trends [3]. This data-driven approach proves more effective than applying rigid chemical rules like charge-balancing, which only accounts for 37% of known ICSD compounds [3]. The model's performance can be tuned based on application requirements—lower decision thresholds (e.g., 0.10) maximize recall for exploratory searches, while higher thresholds (e.g., 0.90) provide greater precision for targeted synthesis campaigns [17].

More recent approaches like CSLLM have achieved even higher accuracy rates (98.6%) by representing crystal structures as text and leveraging large language models fine-tuned on ICSD data [11]. However, SynthNN remains notable for its composition-only approach that doesn't require full structural information, making it applicable earlier in the discovery pipeline when crystal structures may be unknown.

Workflow Visualization: ICSD-Driven Material Discovery

AI-Driven Material Discovery Workflow

The workflow diagram illustrates the pipeline for leveraging ICSD data to accelerate material discovery. The process begins with the extensive ICSD repository, which provides over 240,000 quality-checked crystal structures for training [14] [15]. Through data preprocessing, these structures are transformed into curated training sets suitable for machine learning. The SynthNN model is then trained on this data, learning the complex patterns that distinguish synthesizable materials [3]. The trained model screens millions of candidate compositions, identifying promising candidates for human expert validation [3] [18]. Finally, the most promising candidates proceed to experimental synthesis, with external researchers having successfully synthesized 736 GNoME-predicted structures in concurrent work [18].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Synthesizability Prediction

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for AI-Driven Material Discovery

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in Synthesizability Prediction |

|---|---|---|

| ICSD Database | Provides experimental crystal structure data | Foundational training data for machine learning models [14] [15] |

| SynthNN | Deep learning synthesizability classifier | Predicts synthesizability from composition alone [3] [17] |

| DFT Calculations | Computes formation energy and Ehull | Thermodynamic stability assessment as synthesizability proxy [8] [2] |

| CSLLM Framework | LLM for structure-based synthesizability | Predicts synthesizability, methods, and precursors [11] |

| GNoME | Graph neural network for material exploration | Discovered 2.2 million new crystals with stability predictions [18] |

| Atom2Vec | Learned atomic representation | Embeds chemical elements in optimized vector space [3] |

The experimental evidence demonstrates that the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database provides an indispensable foundation for training AI models that dramatically outperform both human experts and traditional computational methods in predicting material synthesizability. The ICSD's comprehensive, quality-checked repository of inorganic crystal structures enables models like SynthNN to learn complex chemical relationships directly from data, achieving superior precision while accelerating discovery by orders of magnitude. As AI continues to transform materials science, the ICSD's role as a verified, curated knowledge base becomes increasingly critical for developing reliable predictive tools that can bridge the gap between computational prediction and experimental synthesis.

Inside SynthNN: How Deep Learning Decodes the Principles of Material Synthesis

Predicting whether a theoretical inorganic crystalline material can be successfully synthesized represents a fundamental challenge in materials science and drug development. Traditional approaches have relied on computational methods like density-functional theory (DFT) calculations of formation energy or simple chemical heuristics like charge-balancing. However, these methods show significant limitations; charge-balancing correctly identifies only 37% of known synthesized compounds, while DFT-based formation energy calculations capture only about 50% of synthesized inorganic crystalline materials [3]. Furthermore, these traditional methods fail to account for the complex array of kinetic, thermodynamic, and human-factor considerations that ultimately determine whether a synthesis attempt will be successful.

The SynthNN (Synthesizability Neural Network) framework represents a paradigm shift in addressing this challenge. By leveraging deep learning and the Atom2Vec representation, SynthNN reformulates material discovery as a synthesizability classification task that learns directly from the entire corpus of known synthesized inorganic chemical compositions [3]. This approach demonstrates how artificial intelligence can not only match but exceed human expertise in predicting synthesizability, achieving 1.5× higher precision than the best human expert while completing the task five orders of magnitude faster [3] [7]. This architectural overview examines the deep learning model and Atom2Vec representation that enable these advances, with particular focus on their performance compared to human experts and alternative computational methods.

SynthNN Architecture and Workflow

Atom2Vec Representation

The foundational innovation enabling SynthNN's performance is the Atom2Vec representation, which learns optimal feature representations of chemical formulas directly from the distribution of previously synthesized materials [3]. Unlike traditional cheminformatics approaches that rely on manually engineered features or predefined chemical principles, Atom2Vec employs a learned atom embedding matrix that is optimized alongside all other parameters of the neural network [3]. This representation automatically discovers chemically meaningful patterns without explicit programming, effectively learning the principles of charge-balancing, chemical family relationships, and ionicity directly from data [3].

The Atom2Vec framework operates by representing each chemical formula through embeddings that capture the complex relationships between elements across the entire periodic table. The dimensionality of this representation is treated as a hyperparameter optimized during model development [3]. This approach allows the model to develop an internal representation of chemical space that reflects the real-world distribution of synthesized materials, rather than being constrained by human preconceptions about which factors should influence synthesizability.

Model Architecture and Training

SynthNN implements a deep learning classification model trained on a comprehensive dataset of chemical formulas derived from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), which represents "a nearly complete history of all crystalline inorganic materials that have been reported to be synthesized in the scientific literature" [3]. A significant challenge in training arises because "unsuccessful syntheses are not typically reported in the scientific literature" [3], creating a lack of definitive negative examples.

To address this challenge, the developers employ a semi-supervised positive-unlabeled (PU) learning approach that treats artificially generated unsynthesized materials as unlabeled data and probabilistically reweights them according to their likelihood of being synthesizable [3]. The training dataset is augmented with these artificially generated unsynthesized materials, with the ratio of artificially generated formulas to synthesized formulas (Nsynth) treated as a key hyperparameter [3]. This approach enables the model to learn the distinguishing characteristics of synthesizable materials despite the incomplete labeling inherent in materials databases.

Table: SynthNN Architectural Components

| Component | Description | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Input Representation | Atom2Vec embedding matrix | Converts chemical formulas to optimized vector representations |

| Learning Framework | Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning | Handles lack of negative examples in training data |

| Training Data | ICSD database + artificially generated unsynthesized materials | Provides comprehensive coverage of known and hypothetical materials |

| Output | Synthesizability probability | Classification of material as synthesizable or not |

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete SynthNN experimental workflow from data preparation to synthesizability prediction:

Performance Comparison: SynthNN vs. Human Experts

Experimental Protocol

The comparative performance between SynthNN and human experts was evaluated through a head-to-head material discovery task involving 20 expert materials scientists [3]. These experts specialized in various domains of solid-state chemistry and brought extensive experience in synthetic methodologies. The experimental design presented both human experts and the SynthNN model with the same set of candidate materials for synthesizability assessment.

The human experts employed their traditional approach to synthesizability evaluation, which typically involves considering factors such as thermodynamic stability, kinetic accessibility, chemical intuition, and analogy to known materials. Their decision-making process incorporated considerations of charge-balancing, element compatibility, and prior experience with similar chemical systems. Each expert worked independently to evaluate the same set of candidate compositions.

Simultaneously, SynthNN processed the identical set of candidate materials using its trained deep learning model. The model generated synthesizability predictions based on the learned Atom2Vec representations without any human intervention or additional chemical information beyond the composition data. The performance was evaluated against a ground truth dataset of known synthesizable materials, with precision and speed as the primary metrics.

Quantitative Results

Table: Performance Comparison: SynthNN vs. Human Experts

| Metric | SynthNN | Best Human Expert | Average Human Expert |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | 1.5× higher than best expert [3] [7] | Baseline | 3.6× lower precision than SynthNN [19] |

| Speed | 5 orders of magnitude faster [3] [7] | Baseline | 5 orders of magnitude slower [3] |

| Learning Source | Entire ICSD database | Specialized domain knowledge [3] | Limited to specialized domain [3] |

| Chemical Principles | Learned from data (charge-balancing, ionicity) [3] | Explicitly applied | Explicitly applied |

The results demonstrate SynthNN's superior performance across both accuracy and efficiency metrics. While "expert synthetic chemists typically specialize in a specific chemical domain of a few hundred materials," SynthNN "generates predictions that are informed by the entire spectrum of previously synthesized materials" [3]. This comprehensive knowledge base enables the model to outperform even the best human experts while completing the evaluation task in a fraction of the time.

Performance Comparison: SynthNN vs. Computational Methods

Experimental Protocol

The comparison between SynthNN and computational methods evaluated several established approaches for synthesizability prediction. The baseline methods included:

Charge-Balancing Approach: This method predicts a material as synthesizable only if it is charge-balanced according to common oxidation states, following traditional chemical heuristics [3].

DFT-Based Formation Energy: This approach utilizes density-functional theory to calculate the formation energy of a material's crystal structure with respect to the most stable phase in the same chemical space, assuming that synthesizable materials will not have thermodynamically stable decomposition products [3].

Random Guessing Baseline: This represents the expected performance of random predictions weighted by the class imbalance, serving as a lower-bound reference [3].

The evaluation was conducted on a standardized dataset with a 20:1 ratio of unsynthesized to synthesized examples, reflecting the real-world challenge of identifying rare synthesizable materials within a vast chemical space [17]. Performance was measured using precision-recall metrics at various classification thresholds.

Quantitative Results

Table: Performance Comparison: SynthNN vs. Computational Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SynthNN | Deep learning with Atom2Vec representation | 7× higher precision than DFT [3]; Learns chemical principles from data [3] | Requires training data; Black-box predictions |

| DFT Formation Energy | Thermodynamic stability | Physics-based; No training required | Captures only 50% of synthesized materials [3] |

| Charge-Balancing | Net neutral ionic charge | Computationally inexpensive; Chemically intuitive | Identifies only 37% of known synthesized compounds [3] |

| CSLLM (2025) | Large language model fine-tuning | 98.6% accuracy [4]; Predicts methods & precursors [4] | Requires structure information [4] |

Table: SynthNN Precision-Recall Tradeoff at Different Thresholds [17]

| Decision Threshold | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|

| 0.10 | 0.239 | 0.859 |

| 0.20 | 0.337 | 0.783 |

| 0.30 | 0.419 | 0.721 |

| 0.40 | 0.491 | 0.658 |

| 0.50 | 0.563 | 0.604 |

| 0.60 | 0.628 | 0.545 |

| 0.70 | 0.702 | 0.483 |

| 0.80 | 0.765 | 0.404 |

| 0.90 | 0.851 | 0.294 |

The precision-recall table demonstrates how SynthNN allows researchers to select appropriate decision thresholds based on their specific needs—prioritizing either high recall (to minimize false negatives) or high precision (to minimize false positives). This flexibility is particularly valuable in materials discovery workflows where the cost of false positives versus false negatives may vary depending on the application.

Research Reagent Solutions: Experimental Toolkit

The implementation and application of SynthNN requires several key research reagents and computational resources. The following table details these essential components and their functions in the synthesizability prediction workflow:

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource | Type | Function | Source/Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICSD Database | Data Resource | Provides confirmed synthesized materials for training [3] | Commercial license required [17] |

| Atom2Vec Library | Software | Generates optimal atom representations from composition data [3] | Open source implementation [3] |

| Positive-Unlabeled Learning Algorithm | Algorithm | Handles lack of negative examples in training data [3] | Custom implementation [3] |

| Pre-trained SynthNN Models | Model Weights | Enable predictions without retraining [17] | Available via GitHub repository [17] |

| Material Composition Data | Input | Chemical formulas for prediction [17] | User-provided or from materials databases |

| Carboxyphosphamide-d4 | Carboxyphosphamide-d4, MF:C7H15Cl2N2O4P, MW:297.11 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| N-methylleukotriene C4 | N-methylleukotriene C4, MF:C31H48N3O9S+, MW:638.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The architectural overview of SynthNN reveals how its deep learning model with Atom2Vec representation achieves superior performance in predicting material synthesizability compared to both human experts and traditional computational methods. By learning directly from the comprehensive database of known synthesized materials, SynthNN internalizes complex chemical principles without explicit programming, enabling it to identify synthesizable materials with 7× higher precision than DFT-based approaches and 1.5× higher precision than the best human expert [3].

The Atom2Vec representation serves as the foundational innovation that allows the model to develop an internal understanding of chemical space that reflects real-world synthesizability patterns. Combined with the positive-unlabeled learning framework that addresses the fundamental challenge of incomplete negative examples in materials science, SynthNN represents a significant advancement in computational materials discovery.

For researchers in materials science and drug development, SynthNN offers a powerful tool that can be seamlessly integrated into computational screening workflows, dramatically increasing the efficiency of identifying synthetically accessible materials. The availability of pre-trained models and open-source implementations lowers the barrier to adoption, enabling widespread use across the research community [17]. As synthetic methodologies continue to evolve, the adaptability of this deep learning approach positions it as a cornerstone technology for accelerating the discovery of novel functional materials.

Identifying which theoretically possible inorganic crystalline materials can be successfully synthesized in a laboratory remains a fundamental challenge in materials science and drug development. Traditional approaches have relied on computational methods like density functional theory (DFT) calculations of formation energies or human expertise, both of which have significant limitations [3]. DFT-based methods, while valuable for assessing thermodynamic stability, often fail to account for kinetic stabilization and synthetic accessibility, capturing only approximately 50% of synthesized inorganic crystalline materials [3]. Meanwhile, human experts bring invaluable experience but typically specialize in narrow chemical domains and require substantial time for evaluation [3].

SynthNN (Synthesizability Neural Network) represents a paradigm shift in this field. This deep learning model leverages the entire space of synthesized inorganic chemical compositions to predict synthesizability without requiring prior chemical knowledge or structural information [3] [7]. By reformulating material discovery as a synthesizability classification task, SynthNN demonstrates how data-driven approaches can autonomously discover fundamental chemical principles that have traditionally required years of expert training to master.

SynthNN Architecture and Methodology

Model Design and Training Framework

SynthNN employs a sophisticated deep learning architecture that fundamentally differs from traditional computational materials science approaches:

Atom2Vec Representation: The model represents each chemical formula using a learned atom embedding matrix that is optimized alongside all other neural network parameters [3]. This approach allows SynthNN to discover optimal representations of chemical formulas directly from the distribution of previously synthesized materials without human preconceptions about which factors should influence synthesizability.

Positive-Unlabeled Learning: A significant challenge in synthesizability prediction is the lack of confirmed negative examples (definitively unsynthesizable materials). SynthNN addresses this through a semi-supervised positive-unlabeled (PU) learning approach that treats artificially generated materials as unlabeled data and probabilistically reweights them according to their likelihood of being synthesizable [3].

Training Data Composition: The model is trained on chemical formulas extracted from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), representing a nearly complete history of all reported crystalline inorganic materials [3]. This dataset is augmented with artificially generated unsynthesized materials, with the ratio of artificial to synthesized formulas treated as a hyperparameter (N_synth) [3].

Table: SynthNN Architectural Components and Their Functions

| Component | Function | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|

| Atom Embedding Matrix | Learns optimal representation of elements from data | Eliminates need for human-designed feature engineering |

| Positive-Unlabeled Framework | Handles lack of confirmed negative examples | Accounts for potentially synthesizable but untested materials |

| Deep Neural Network | Classification of synthesizability | Learns complex, non-linear relationships in compositional space |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

The development and validation of SynthNN followed rigorous experimental protocols to ensure robust performance assessment:

Benchmarking Against Baselines: Researchers compared SynthNN against multiple baseline methods, including random guessing and charge-balancing approaches [3]. The charge-balancing method predicts synthesizability based on whether a material can achieve net neutral ionic charge using common oxidation states.

Human Expert Comparison: In a head-to-head material discovery comparison, SynthNN was evaluated against 20 expert materials scientists to assess both precision and speed [3].

Performance Metrics: Standard classification metrics were calculated by treating synthesized materials and artificially generated unsynthesized materials as positive and negative examples, respectively [3]. This approach necessarily produces conservative precision estimates since some artificial materials may be synthesizable but not yet synthesized.

Diagram: SynthNN Neural Network Architecture. The model transforms chemical compositions into synthesizability predictions through learned representations.

Performance Comparison: SynthNN vs. Alternative Approaches

Quantitative Performance Metrics

SynthNN demonstrates substantial improvements over both computational baselines and human experts:

Table: Performance Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

| Method | Precision | Speed | Key Advantage | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SynthNN | 7× higher than DFT formation energy [3] | 5 orders of magnitude faster than best human expert [3] | Learns chemical principles from data | Requires large dataset of known materials |

| DFT Formation Energy | Baseline (1×) [3] | Computational intensive | Strong theoretical foundation | Captures only ~50% of synthesized materials [3] |

| Charge-Balancing | 37% of known materials charge-balanced [3] | Computationally fast | Simple heuristic | Poor performance (only 23% for binary cesium compounds) [3] |

| Human Experts | 1.5× lower precision than SynthNN [3] | Slowest option | Domain knowledge | Limited to specialized chemical domains |

Emerging Alternative: CSLLM Framework

Recent advances in synthesizability prediction include the Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models (CSLLM) framework, which utilizes specialized LLMs to predict synthesizability, synthetic methods, and precursors for 3D crystal structures [11]. CSLLM achieves remarkable 98.6% accuracy on testing data by using a comprehensive dataset of 70,120 synthesizable structures from ICSD and 80,000 non-synthesizable structures identified through PU learning [11]. While this represents a different architectural approach focused on structural information rather than just composition, it further demonstrates the power of data-driven methods in synthesizability prediction.

Chemical Principles Discovered Autonomously

Remarkably, without any prior chemical knowledge explicitly programmed, SynthNN demonstrates learning of fundamental chemical principles through data analysis alone:

Charge-Balancing: The model autonomously discovers the importance of ionic charge balance, a cornerstone principle in solid-state chemistry [3]. This is particularly remarkable given that only 37% of known inorganic materials are charge-balanced according to common oxidation states, suggesting SynthNN learns a more nuanced understanding of this principle.

Chemical Family Relationships: SynthNN identifies relationships between elements and compounds that share chemical characteristics, allowing it to make inferences about new materials based on similarities to known ones [3].

Ionicity Principles: The model develops an understanding of how ionic character influences synthesizability across different classes of materials, including metallic alloys, covalent materials, and ionic solids [3].

These emergent capabilities demonstrate how data-driven approaches can rediscover fundamental chemical knowledge through pattern recognition in large datasets, potentially revealing new insights that might be overlooked by traditional hypothesis-driven research.

Research Reagent Solutions for Synthesizability Prediction

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Synthesizability Prediction Research

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in Synthesizability Prediction |

|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) | Repository of experimentally characterized inorganic structures | Provides ground truth data for training models like SynthNN [3] |

| atom2vec | Algorithm for learning material representations | Creates optimal feature representations without human bias [3] |

| Positive-Unlabeled Learning Frameworks | Handles lack of negative examples | Addresses fundamental challenge in synthesizability prediction [3] |

| DFT Calculations | Computes formation energies and phase stability | Provides baseline comparison for data-driven approaches [3] |

| Graph Neural Networks | Processes crystal structure information | Enables structure-based synthesizability prediction [1] |

Diagram: SynthNN Experimental Workflow. The process begins with known materials data and progresses through automated learning to synthesizability predictions.

Implications for Materials Discovery and Drug Development

The development of SynthNN represents a significant advancement in computational materials science with particular relevance for drug development professionals who rely on novel materials for drug delivery systems, diagnostic agents, and pharmaceutical formulations. By achieving 1.5× higher precision than the best human experts and completing synthesizability assessment five orders of magnitude faster, SynthNN enables rapid screening of candidate materials [3]. This acceleration is particularly valuable in early-stage drug development where time-to-market considerations are critical.

Furthermore, SynthNN's ability to learn chemical principles directly from data suggests potential applications in predicting synthesizability of novel pharmaceutical cocrystals, polymorphs, and other solid forms with desirable properties. The model's architecture could potentially be adapted to organic and organometallic systems relevant to drug development, though this would require appropriate training data.

As materials discovery continues to evolve toward increasingly autonomous workflows, SynthNN demonstrates how human expertise can be augmented rather than replaced—with experts focusing on complex edge cases and model refinement while routine synthesizability assessment is handled by data-driven systems. This human-AI collaboration paradigm represents the future of efficient materials discovery with significant implications across scientific domains, including pharmaceutical development.

In numerous scientific fields, from materials science to drug discovery, a major bottleneck hindering the application of machine learning is the lack of reliably labeled negative data. For tasks like predicting whether a new material can be synthesized or a new molecule will have a desired therapeutic effect, researchers often have a set of confirmed positive examples (e.g., successfully synthesized materials, known active drugs) and a vast pool of unlabeled examples whose status is unknown. Positive-Unlabeled (PU) learning is a specialized branch of machine learning designed to overcome this exact challenge. It enables the training of robust classifiers using only a set of labeled positive examples and a set of unlabeled data (which contains both hidden positives and negatives), thereby bypassing the need for a complete and fully labeled dataset.

This guide focuses on the application of the PU learning framework within scientific discovery, using the groundbreaking SynthNN model for predicting material synthesizability as a central case study. We will objectively compare its performance against traditional human expertise and other computational methods, providing the experimental data and protocols that underscore its value as a transformative tool for researchers.