Advancing Solid-State Structure Prediction: Machine Learning, AI, and Validation Strategies for Biomedical Research

Accurate prediction of solid-state structures is a critical challenge with profound implications for drug development and material science.

Advancing Solid-State Structure Prediction: Machine Learning, AI, and Validation Strategies for Biomedical Research

Abstract

Accurate prediction of solid-state structures is a critical challenge with profound implications for drug development and material science. This article explores the latest advancements in computational methods, focusing on the integration of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of crystal structure prediction (CSP) for small molecule pharmaceuticals and biological macromolecules. We cover foundational challenges, innovative methodologies like neural network potentials and large language models, and strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing predictions. The content also addresses rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analyses of emerging tools, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive guide to navigating and applying these transformative technologies in biomedical and clinical research.

The Core Challenges in Solid-State Structure Prediction: From Polymorphism to Protein Dynamics

The Critical Impact of Polymorphism in Pharmaceutical Development and Material Science

Troubleshooting Common Polymorphism Issues in the Laboratory

This section addresses frequent challenges encountered during solid-form research and provides practical solutions.

Table 1: Common Polymorphism Issues and Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Causes | Diagnostic Methods | Corrective & Preventive Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unexpected Solid Form Appearance | Seeding from a metastable form; minor impurities; changes in crystallization solvent or conditions [1] [2]. | X-ray Powder Diffraction (XRPD) to identify the new phase; Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) to check thermal properties [3] [1]. | Control crystallization parameters (temperature, supersaturation, seeding); implement rigorous polymorph screening early in development [2]. |

| Batch-to-Batch Variability in API | Inconsistent crystallization process (e.g., temperature, cooling rate, solvent composition); lack of controlled seeding [1]. | XRPD for solid form identity; particle size analysis; Karl Fischer titration for water content [1]. | Develop a robust, well-controlled crystallization process; use in-line monitoring techniques; define and control critical process parameters [2]. |

| Failed Dissolution or Bioavailability Specifications | Change to a polymorph with lower solubility and dissolution rate [2] [4]. | Dissolution testing; confirm solid form in dosage form using techniques like Raman spectroscopy [2]. | Select the most thermodynamically stable form for development; monitor for form conversion during formulation processes like wet granulation and milling [2] [4]. |

| Form Instability During Drug Product Manufacturing | Processing-induced transformation (e.g., during milling, compaction, or wet granulation); excipient interactions [2]. | Compare XRPD or solid-state NMR of API before and after processing; test intact dosage form [2]. | Select a physically robust polymorph; avoid high-shear processes that can induce phase changes; study excipient compatibility [2]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Polymorphism

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between a polymorph and a solvate/hydrate?

A polymorph is a solid crystalline phase of a compound with the same chemical composition but a different molecular arrangement or conformation in the crystal lattice [3] [5]. A solvate (or hydrate, if the solvent is water) is a crystalline form that incorporates solvent molecules as part of its structure, thus having a different chemical composition from the unsolvated form [2] [5]. It is a common misconception to call solvates "pseudopolymorphs"; this term is discouraged. A true polymorph is a different crystal structure of the identical chemical substance [5].

Q2: Why is polymorphism considered a major risk in pharmaceutical development?

Polymorphism is a critical risk because different solid forms can have vastly different physicochemical properties, such as solubility, dissolution rate, and chemical and physical stability [2] [4]. If a more stable, less soluble polymorph appears after a drug is marketed, it can render the product ineffective, as famously occurred with Ritonavir. This event led to a product withdrawal and cost an estimated $250 million, highlighting the devastating financial and patient-care impacts [4]. Furthermore, about 85% of marketed drugs have more than one crystalline form, making this a widespread concern [4].

Q3: When should we begin polymorph screening for a new API, and what is the goal?

Polymorph screening should begin as early in drug development as drug substance supply allows [2]. The goal is to identify the optimal solid form (considering stability, bioavailability, and manufacturability) before large-scale GMP production and clinical trials begin. A staged approach is recommended:

- Early Stage: An abbreviated screen on efficacious compounds before final candidate selection.

- Mid-Stage: A full polymorph screen before the first GMP material is produced.

- Late Stage: An exhaustive screen before drug launch to find and patent all possible forms [2]. This strategy helps avoid the costly dilemma of having clinical trials with one form and commercial production with another [2].

Q4: Our API consistently crystallizes in a metastable form. How can we obtain the stable form?

The failure to crystallize the stable form is a known challenge, as seen with acetaminophen, where the orthorhombic form could only be isolated using seeds obtained from melt-crystallized material, not from standard solvent evaporation [1]. To overcome this:

- Vary Crystallization Conditions: Use a wide range of solvents, temperatures, and supersaturation levels.

- Use Seeding: Actively seed experiments with the desired stable form, if available.

- Employ Alternative Techniques: Try methods like melt crystallization, grinding, or crystallization from amorphous solids to access forms that are difficult to obtain from solution [1] [6].

- Leverage Solid Solutions: In some systems, forming a solid solution with a similar "guest" molecule can stabilize a metastable "host" polymorph, switching the thermodynamic stability landscape [6].

Q5: How can Machine Learning (ML) improve crystal structure prediction (CSP)?

Traditional CSP is computationally intensive. ML accelerates this by:

- Narrowing the Search Space: ML models can predict likely space groups and packing densities for a given molecule, filtering out low-probability, unstable structures before expensive calculations begin [7].

- Providing Efficient Forcefields: Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) trained on quantum mechanical data enable rapid and accurate structure relaxation at a fraction of the computational cost of Density Functional Theory (DFT) [8] [7].

- Predicting Synthesizability: Advanced models like Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models (CSLLM) can predict whether a theoretical crystal structure is synthesizable, its likely synthetic method, and suitable precursors, bridging the gap between prediction and experimental realization [9].

Experimental Protocols for Key Investigations

Protocol for Polymorph Screening via Slurry Conversion

Objective: To identify the most thermodynamically stable anhydrous polymorph of an API under relevant conditions.

Principle: A slurry of the solid in a solvent creates a microenvironment where less stable forms dissolve and the most stable form grows, facilitating conversion to the lowest-energy structure [1].

Materials:

- API (mixture of known or unknown forms)

- A range of pure solvents (e.g., water, alcohols, acetonitrile, ethyl acetate, heptane)

- Vials with magnetic stirrers or roller banks

- Temperature-controlled incubator or chamber

Procedure:

- Slurry Preparation: Place a small amount of the API (e.g., 50-100 mg) into each vial. Add a sufficient volume of solvent to create a mobile slurry, typically leaving about 90% of the solid undissolved.

- Equilibration: Cap the vials and agitate them continuously at a constant temperature (e.g., 5°C, 25°C, 40°C) for a predefined period (e.g., 1-7 days).

- Sampling: After the equilibration period, stop agitation and allow the solid to settle. Isolate the solid by filtration.

- Analysis: Analyze the solid residue using XRPD to identify the crystalline form present. Complementary techniques like DSC and Raman spectroscopy can provide additional confirmation.

- Validation: The form that consistently appears across multiple solvents and temperatures is likely the thermodynamically most stable anhydrous form under those conditions.

Protocol for Solid Form Stability Assessment

Objective: To determine the physical stability of a polymorph and its potential for interconversion under stress conditions.

Principle: Exposing a solid form to elevated temperature and humidity can accelerate physical and chemical degradation processes, revealing the relative stability of polymorphs.

Materials:

- Candidate polymorphs

- Controlled stability chambers (e.g., 40°C/75% RH, 60°C)

- Desiccators with saturated salt solutions for specific humidity levels

- Analytical equipment (XRPD, DSC, TGA, HPLC)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Spread a thin layer of each polymorphic sample in open glass dishes or place in vials.

- Stress Conditions: Place samples in stability chambers set at accelerated conditions (e.g., 40°C/75% RH, 60°C/dry). Include a controlled room temperature condition as a baseline.

- Time Points: Remove samples at scheduled intervals (e.g., 1, 2, 4 weeks, 3 months).

- Analysis:

- Physical Form: Analyze by XRPD to detect any solid-form changes.

- Chemical Purity: Analyze by HPLC to rule out chemical degradation.

- Hydration/Desolvation: Use TGA and Karl Fischer titration to monitor changes in solvent/water content.

- Interpretation: The form that shows no change in crystallinity, chemical purity, or hydration state is considered the most stable under the tested conditions.

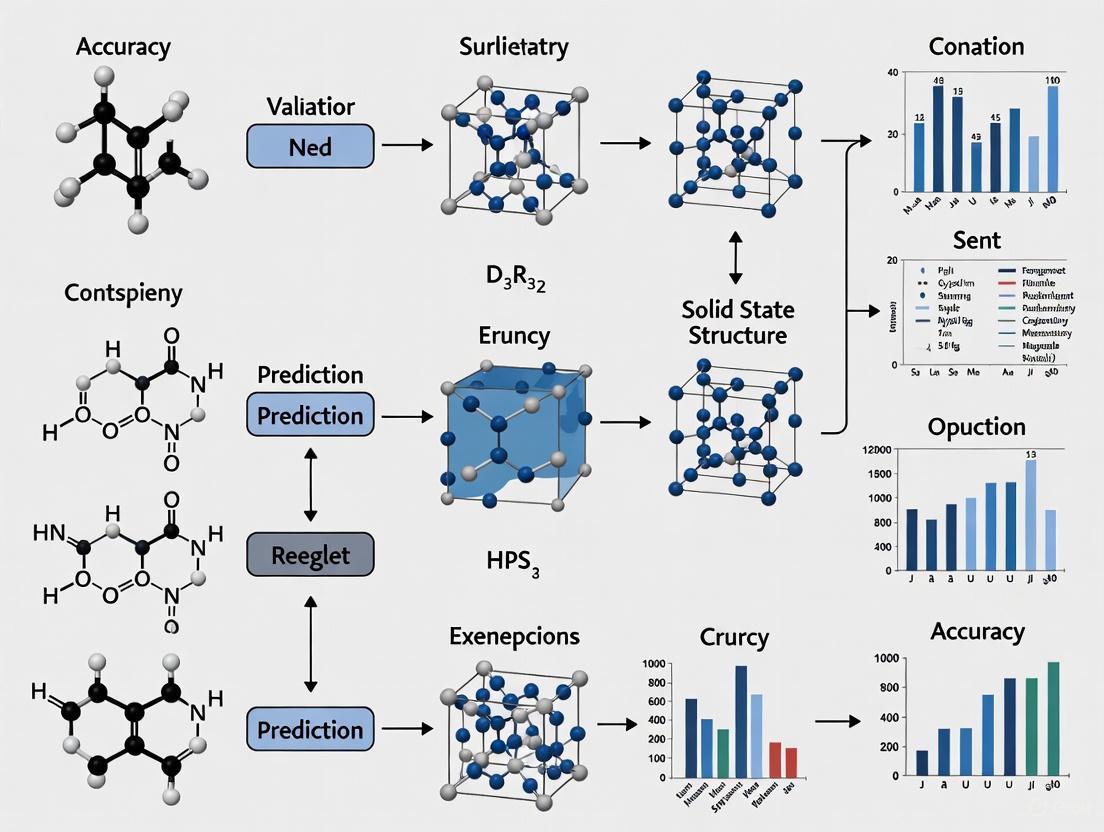

Workflow: From Prediction to Experimental Realization

The following diagram illustrates an integrated workflow combining computational prediction and experimental validation for robust polymorph control, a core concept for improving the accuracy of solid-state structure prediction research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Polymorph Screening

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Solvent Systems | Water, Methanol, Ethanol, Acetonitrile, Acetone, Ethyl Acetone, Toluene, Heptane, Chloroform [1]. | To crystallize the API from a diverse range of polarities, hydrogen-bonding capacities, and dielectric constants to explore the full solid-form landscape. |

| Seeding Materials | Authentic samples of known polymorphs (e.g., from melt crystallization or previous screens) [1]. | To provide a nucleation site to selectively produce a specific polymorph, especially metastable forms that are difficult to access spontaneously. |

| Solid Solution Components | Structurally similar molecules (e.g., nicotinamide for benzamide systems) [6]. | To investigate the formation of solid solutions, which can alter the relative stability of polymorphs and provide a pathway to otherwise inaccessible forms [6]. |

| Analytical Standards | Certified reference materials for thermal analysis (e.g., Indium for DSC calibration). | To ensure the accuracy and calibration of analytical instruments used for characterizing and distinguishing between polymorphs. |

Overcoming the Limitations of Weak Intermolecular Forces in Organic Crystals

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is Crystal Structure Prediction (CSP) particularly challenging for organic molecules compared to inorganic ones?

Organic crystals are stabilized by relatively weak intra- and inter-molecular interactions such as van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonds, and π–π stacking, unlike inorganic crystals which often rely on stronger ionic or covalent bonds [7]. Even minor variations in these weak interactions can give rise to entirely different crystal structures, making accurate prediction difficult [7]. Furthermore, the energy differences between polymorphs are usually very small (often in single units of kJ mol⁻¹), which is comparable to both the thermal noise at room temperature (kT = 2.5 kJ mol⁻¹) and the typical error margins of experimental sublimation enthalpy measurements or sophisticated Density-Functional Theory (DFT) calculations [10]. This narrow energy window makes identifying the true global energy minimum extremely difficult.

FAQ 2: What are the dominant types of weak intermolecular forces in organic crystals, and how do their energies compare?

The following table summarizes the key weak interactions and their typical energy ranges:

Table 1: Types and Strengths of Weak Intermolecular Interactions in Organic Crystals

| Interaction Type | Typical Energy Range (kJ mol⁻¹) | Description and Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Van der Waals (Dispersion) Forces | Varies widely | Includes Coulombic, polarization, and dispersion forces. A "significant share" of cohesive energy is in non-specific contacts [10]. |

| Hydrogen Bonds (Strong) | 20 – 40 | E.g., D—H⋯A where D and A are O, N, F [10]. |

| Charge-Assisted Hydrogen Bonds | Up to ~150 | Comparable in energy to some covalent bonds [10]. |

| Weak Hydrogen Bonds (e.g., C—H⋯O) | ~5 | Considerably weaker than classical hydrogen bonds [10]. |

| C—H⋯π Interactions | As low as ~0.2 | Imperceptibly merges with unspecified van der Waals interactions [10]. |

| Halogen Bonds | 10 – 200 | Energy varies widely based on atoms involved and geometry [10]. |

FAQ 3: My CSP workflow generates too many low-density, unstable candidate structures. How can I improve its efficiency?

This is a common issue with random sampling methods. A highly effective strategy is to employ machine learning (ML) models to narrow the search space before performing expensive energy calculations [7]. Specifically, you can implement:

- Space Group Prediction: Use an ML classifier (e.g., LightGBM) trained on the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) to predict the most probable space groups for your molecule, rather than sampling all 230 possibilities [7].

- Packing Density Prediction: Use an ML regression model to predict the target crystal density, allowing you to filter out randomly sampled lattice parameters that do not satisfy the density tolerance during the initial structure generation [7]. This "sample-then-filter" approach has been shown to double the success rate of CSP compared to purely random sampling [7].

FAQ 4: What are the best practices for energy ranking in CSP to ensure accuracy while managing computational cost?

A hierarchical ranking method that balances cost and accuracy is considered state-of-the-art [11]. The recommended protocol is:

- Initial Screening: Use a classical force field (FF) or a machine learning force field (MLFF) to quickly relax and rank a large number of generated candidate structures.

- Intermediate Refinement: Optimize and re-rank the top candidates from the first stage using a machine learning force field (MLFF) that includes long-range electrostatic and dispersion interactions for greater accuracy [11].

- Final Ranking: Perform periodic DFT calculations (e.g., using the r2SCAN-D3 functional) on the shortlisted candidates to obtain the most reliable relative energies for the final ranking [11].

FAQ 5: How can we account for the risk of "late-appearing" polymorphs in drug development?

Computational CSP is a powerful tool to de-risk this problem. By performing extensive CSP calculations, you can identify all low-energy polymorphs of an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API), including those not yet discovered experimentally [11]. If the calculations reveal a thermodynamically competitive polymorph that has not been observed, it signals a potential risk. Proactive experimental efforts can then be directed toward attempting to crystallize this form under various conditions, allowing you to characterize its properties and secure intellectual property or adjust the formulation strategy early in development [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inaccurate Relative Energy Ranking of Polymorphs The computed energy landscape does not match experimental stability, or the known form is not ranked as the lowest in energy.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Energy Ranking Issues

| Symptoms | Potential Causes | Solutions and Experimental Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Known polymorph is not ranked as the most stable. | 1. Inadequate treatment of dispersion forces in DFT.2. Overlooking temperature effects (comparing 0 K energy to room-temperature stability).3. Insufficient lattice sampling missed the global minimum. | 1. Protocol: Improve DFT Methodology - Use a DFT functional that includes van der Waals corrections (e.g., D3 dispersion correction) [11]. - For final rankings, use a high-quality functional like r2SCAN-D3 [11].2. Protocol: Estimate Free Energy - Perform lattice dynamics calculations or use machine learning potentials to estimate the vibrational contribution to the free energy (G), which is more relevant for experimental stability at finite temperatures than the 0 K internal energy (U) [11]. |

| Over-prediction: Too many candidate structures with energy very close to the global minimum. | 1. Redundant sampling of structures that are nearly identical.2. Clustering of structures that are functionally the same but represent different local minima on a flat potential energy surface. | Protocol: Post-Processing Clustering- Cluster the relaxed candidate structures based on structural similarity (e.g., using RMSD₁₅ < 1.2 Å for a cluster of 15 molecules) [11].- Select a single representative structure with the lowest energy from each cluster before the final analysis. This removes trivial duplicates and provides a cleaner, more interpretable energy landscape [11]. |

Problem: Low Success Rate in Reproducing Experimental Crystal Structures Your CSP workflow consistently fails to generate the experimentally observed crystal structure within the top candidates.

Table 3: Troubleshooting Low CSP Success Rate

| Symptoms | Potential Causes | Solutions and Experimental Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| The experimentally observed structure is not generated. | 1. Inaccurate initial molecular conformation.2. Inefficient sampling of the crystal packing space (e.g., missing the correct space group or lattice parameters). | 1. Protocol: Molecular Conformer Preparation - Extract the molecular geometry from an experimental CIF file, then optimize it in isolation using a high-quality method (e.g., a pre-trained neural network potential like PFP or ANI at MOLECULE mode) with a tight force convergence threshold (e.g., 0.05 eV Å⁻¹) [7].2. Protocol: Enhanced Lattice Sampling - Implement ML-based sampling (SPaDe strategy) to predict space group and density, drastically reducing the generation of unrealistic structures [7]. - For a more systematic search, use a "divide-and-conquer" strategy that breaks down the parameter space into subspaces based on space group symmetries and searches each one consecutively [11]. |

| The experimental structure is generated but poorly ranked after relaxation. | 1. Inaccurate energy model during the initial relaxation steps, causing the structure to relax to an incorrect local minimum.2. Force field inadequacies for specific interactions (e.g., halogen bonds, π-π stacking). | Protocol: Hierarchical Relaxation and Ranking- Adopt a multi-stage workflow. Use a fast MLFF for the initial relaxation of thousands of candidates. Then, take the top several hundred and re-relax/re-rank them with a more accurate, potentially system-specific, MLFF. Finally, apply the most expensive and accurate periodic DFT calculations only to the top 10-50 candidates for the final ranking [11]. This ensures the best model is used on the most promising structures. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 4: Key Computational Tools for Advanced CSP

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Neural Network Potentials (NNPs)(e.g., PFP, ANI) | High-speed structure relaxation with near-DFT accuracy. | Pre-trained models (e.g., PFP v6.0.0) can perform geometry optimizations in CRYSTAL mode, offering a superior balance of speed and accuracy compared to traditional force fields for organic crystals [7]. |

| Machine Learning Density & Space Group Predictors | Intelligent pre-screening of the crystal structure search space. | Models (e.g., LightGBM) trained on CSD data using molecular fingerprints (e.g., MACCSKeys) can predict likely crystal density and space groups, filtering out unrealistic structures before relaxation [7]. |

| Dispersion-Corrected DFT(e.g., r2SCAN-D3) | Final, high-accuracy energy ranking. | Considered a gold standard for final energy evaluations in CSP, as it provides a more physically realistic treatment of the weak dispersion forces that are critical for organic crystal stability [11]. |

| CrystalExplorer17 | Visualization and energy analysis of intermolecular interactions. | Uses a pixel-based formalism and quantum-chemical formalisms to calculate and visualize the energy contributions of specific intermolecular contacts (Coulombic, polarization, dispersion, repulsion) in a crystal [10]. |

| Systematic Packing Search Algorithm | Robust exploration of crystal packing possibilities. | A novel search method that systematically explores crystal packing parameters, often using a divide-and-conquer strategy across space group subspaces, ensuring comprehensive coverage [11]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Modern CSP Workflow for Organic Molecules

This protocol outlines the SPaDe-CSP workflow, which integrates machine learning for efficient sampling and neural network potentials for accurate relaxation [7].

Step 1: Data Curation and Molecular Preparation

- Input: SMILES string or molecular structure of the organic compound.

- Molecular Conformation: Extract the molecular geometry from a relevant CIF file if available, or generate a low-energy conformer. Optimize this gas-phase molecular geometry using a pre-trained NNP (e.g., PFP at

MOLECULEmode) using the BFGS algorithm with a force threshold of 0.05 eV Å⁻¹ [7].

Step 2: Machine Learning-Guided Lattice Sampling

- Feature Generation: Convert the SMILES string into a molecular fingerprint vector (e.g., 167-bit MACCSKeys) [7].

- Space Group Prediction: Input the fingerprint into a pre-trained multi-class classifier (e.g., LightGBM) to obtain a probability distribution over the 32 most common space groups. Set a probability threshold to define a list of candidate space groups for sampling [7].

- Density Prediction: Input the fingerprint into a pre-trained regression model (e.g., LightGBM) to predict the target crystal density.

- Structure Generation: Iteratively generate initial crystal structures by:

- Randomly selecting a space group from the candidate list.

- Randomly sampling lattice parameters within a reasonable range (e.g., 2 ≤ a, b, c ≤ 50 Å; 60 ≤ α, β, γ ≤ 120°).

- Checking if the sampled parameters satisfy the predicted density tolerance. If they do, place the optimized molecule in the lattice. Continue until the desired number of initial structures (e.g., 1000) is generated [7].

Step 3: Hierarchical Structure Relaxation and Ranking

- Stage 1 - Initial Relaxation: Relax all 1000 generated structures using a fast and accurate NNP (e.g., PFP in

CRYSTAL_U0_PLUS_D3mode) using the L-BFGS algorithm (e.g., for up to 2000 iterations) [7]. Rank the relaxed structures by their lattice energy. - Stage 2 - Clustering: Perform a cluster analysis on the top-ranked relaxed structures (e.g., based on RMSD₁₅ < 1.2 Å) to remove duplicates. Select the lowest-energy structure from each cluster [11].

- Stage 3 - Final Ranking: Take the top, unique candidates (e.g., 10-50 structures) and perform a single-point energy calculation or a final gentle relaxation using a high-accuracy, dispersion-corrected periodic DFT method (e.g., r2SCAN-D3) [11]. The final ranking is based on these DFT energies.

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of the modern, hierarchical CSP workflow described in this guide.

Diagram Title: Hierarchical CSP Workflow

Addressing Conformational Flexibility in Molecules and Intrinsically Disordered Proteins

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What are the primary computational methods for generating accurate conformational ensembles of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs)?

Answer: Generating accurate conformational ensembles of IDPs typically requires integrating molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with experimental data. Two primary computational approaches are widely used:

- Maximum Entropy Reweighting: This is a robust and automated procedure that integrates all-atom MD simulations with experimental data from Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS). The method works by reweighting a large pool of structures from unbiased MD simulations to achieve agreement with experimental data, introducing minimal perturbation to the computational model. It uses a single parameter, the desired effective ensemble size, to automatically balance restraints from different experimental datasets [12].

- Integrative Ensemble Modeling (e.g., ENSEMBLE): This approach selects a subset of conformations from a large initial pool to achieve simultaneous agreement with a diverse set of experimental data, including NMR, SAXS, and single-molecule Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (smFRET). This method is valuable for resolving discrepancies between different experimental techniques and validating the final ensemble [13].

FAQ 2: My MD simulations and experimental data show discrepancies in the global dimensions of my IDP. How can I resolve this?

Answer: Discrepancies between simulated and experimental global dimensions, such as the radius of gyration (Rg) and end-to-end distance (Ree), are common. Follow this troubleshooting guide:

Troubleshooting Steps:

Verify the Force Field:

- Issue: The physical model (force field) used in the MD simulation may be biased toward overly compact or overly extended conformations.

- Action: Run comparative simulations using different, modern force fields specifically developed or tuned for IDPs, such as

a99SB-disp,Charmm22*, orCharmm36m[12]. Using a water model that matches the force field is critical.

Integrate Multiple Data Types:

- Issue: Relying on a single experimental technique can lead to an incomplete or biased structural picture.

- Action: Integrate multiple forms of experimental data during the ensemble calculation or for validation. SAXS provides information on Rg, while smFRET and NMR parameters (e.g., chemical shifts, J-couplings, PREs) provide complementary information on local and long-range distances [12] [13].

Apply Reweighting:

- Issue: The unbiased simulation may sample a broad conformational space, but not in the correct proportions.

- Action: Use a maximum entropy reweighting procedure to adjust the statistical weights of structures in your simulation-derived ensemble so that the averaged experimental observables match the measured data. This corrects the ensemble without discarding simulation data [12].

Check for Fluorophore Effects (if using smFRET):

- Issue: Dyes used in smFRET experiments may interact with the protein or each other, perturbing the native ensemble and leading to inaccurate distance inferences.

- Action: Reserve smFRET data as an independent validation set rather than using it as a restraint during ensemble calculation. Consistency with an ensemble built using NMR and SAXS data indicates minimal perturbation from the labels [13].

FAQ 3: How can I predict multiple conformational states for an IDP when no experimental structures are available?

Answer: For proteins without experimentally determined structures, you can use ensemble-based ab initio prediction methods. The FiveFold approach is one such method that leverages a combination of five complementary algorithms (AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold, OmegaFold, ESMFold, and EMBER3D) to generate multiple plausible conformations [14].

Workflow:

- Generate Predictions: Run the protein sequence through the five component algorithms.

- Encode Structures: Use the Protein Folding Shape Code (PFSC) system, which assigns alphabetic characters to different secondary structure elements, to create a standardized representation of each prediction [15] [14].

- Build a Variation Matrix: Construct a Protein Folding Variation Matrix (PFVM) that systematically captures the local folding variations observed across the five predictions along the protein sequence [15] [14].

- Sample Conformations: Generate an ensemble of 3D structures by probabilistically sampling different combinations of the local folding shapes documented in the PFVM [15] [14].

This method is particularly designed to expose flexible conformations and model the conformational diversity inherent to IDPs.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Determining an Atomic-Resolution IDP Ensemble via Maximum Entropy Reweighting

This protocol outlines the steps for refining a conformational ensemble derived from MD simulations using NMR and SAXS data [12].

Step-by-Step Guide:

Generate an Unbiased Structural Pool:

- Perform long-timescale, all-atom MD simulations of the IDP using one or more modern force fields (e.g.,

a99SB-disp,Charmm36m). - Extract tens of thousands of snapshots to create a initial structural ensemble representing conformational diversity.

- Perform long-timescale, all-atom MD simulations of the IDP using one or more modern force fields (e.g.,

Calculate Experimental Observables:

- For each snapshot in the ensemble, use forward models (theoretical calculators) to predict the values of your experimental data.

- For NMR chemical shifts: Use quantum chemical (e.g., Density Functional Theory) or empirical shift calculators [16] [12].

- For SAXS data: Calculate the theoretical scattering profile from the atomic coordinates of each structure [12].

Perform Maximum Entropy Reweighting:

- Input the calculated observables and the corresponding experimental data into the reweighting algorithm.

- Set the target Kish ratio (K), which determines the effective number of conformations in the final ensemble (e.g., K=0.1 retains about 10% of the initial pool).

- Run the optimization. The algorithm will assign new statistical weights to each structure to achieve the best agreement with the experimental data while maximizing the entropy of the weights.

Validate the Ensemble:

- Check that the reweighted ensemble accurately back-calculates the experimental data used in the restraint.

- If available, validate the ensemble against a separate set of experimental data not used in the reweighting (e.g., smFRET data or NMR paramagnetic relaxation enhancements) [13].

The workflow for this integrative approach is summarized below.

Integrative Workflow for IDP Ensemble Determination

Protocol 2: Integrative Modeling with NMR, SAXS, and smFRET Data

This protocol uses the ENSEMBLE method to build a consensus model consistent with three key biophysical techniques [13].

Step-by-Step Guide:

Data Collection:

- NMR: Collect chemical shifts, J-couplings, and relaxation data.

- SAXS: Collect scattering data to inform on global shape and dimensions.

- smFRET: Collect data from constructs labeled at specific sites to inform on long-range distances.

Generate a Candidate Ensemble:

- Create a large, diverse pool of conformations. This can be generated from MD simulations, coarse-grained modeling, or random sampling.

Calculate Theoretical Data:

- For each structure, calculate theoretical NMR parameters, SAXS profiles, and FRET efficiencies based on the positions of dye labels.

Ensemble Selection:

- Use the ENSEMBLE algorithm to find a weighted subset of structures from the candidate pool whose averaged theoretical data simultaneously agree with all experimental datasets (NMR, SAXS, smFRET).

Analysis and Functional Insight:

- Analyze the properties of the final ensemble (e.g., distribution of Rg and Ree, presence of transient structures) to draw conclusions about the IDP's function, such as its mechanisms of binding or regulation.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Force Field Performance for IDP Simulations

This table summarizes the initial agreement with experimental data for MD simulations of various IDPs run with different force fields before reweighting, based on a benchmark study [12].

| Protein (Length) | a99SB-disp | Charmm22* (C22*) | Charmm36m (C36m) | Key Observables |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aβ40 (40 residues) | Reasonable agreement | Reasonable agreement | Reasonable agreement | Chemical Shifts, SAXS |

| drkN SH3 (59 residues) | Reasonable agreement | Reasonable agreement | Reasonable agreement | Chemical Shifts, SAXS |

| α-Synuclein (140 residues) | Reasonable agreement | Reasonable agreement | Reasonable agreement | Chemical Shifts, SAXS |

| ACTR (69 residues) | Reasonable agreement | -- | Divergent sampling | Chemical Shifts, SAXS |

| PaaA2 (70 residues) | Reasonable agreement | Divergent sampling | -- | Chemical Shifts, SAXS |

Table 2: Computational Methods for IDP Conformational Analysis

This table provides a comparison of key computational tools and methods used in the field.

| Method / Tool | Type | Primary Function | Key Application in IDP Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Entropy Reweighting [12] | Hybrid (Simulation + Exp) | Refines MD ensembles to match experimental data | Determining accurate, force-field independent conformational ensembles |

| ENSEMBLE [13] | Hybrid (Simulation + Exp) | Selects a weighted subset of structures to fit multiple data types | Integrative modeling with NMR, SAXS, and smFRET data |

| FiveFold [14] | Ab Initio Prediction | Generates multiple conformational states from sequence | Predicting conformational ensembles for IDPs without known structures |

| PFSC/PFVM [15] [14] | Analysis/Prediction | Encodes and analyzes local folding patterns | Revealing folding flexibility and variation from sequence or structures |

| DFT (Density Functional Theory) [16] | Quantum Chemical | Calculates NMR parameters (chemical shifts) from structure | Validating and assigning structures by comparing computed and experimental NMR spectra |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational and Experimental Reagents

| Item | Function / Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Modern Force Fields (a99SB-disp, Charmm36m) | Physical models defining atomic interactions for MD simulations. | Critical for accurate initial sampling of IDP conformations; performance should be benchmarked [12]. |

| NMR Chemical Shift Prediction (DFT) | Quantum mechanical calculation of NMR parameters from a 3D structure. | Enables direct comparison between candidate structures and experimental NMR spectra for validation [16]. |

| Forward Model Calculators | Software to compute experimental observables (SAXS profile, smFRET efficiency) from atomic coordinates. | Essential for integrating simulation and experiment; examples include SASTBX for SAXS and FRETcalc for smFRET [12] [13]. |

| Site-Directed Spin/Labeling Reagents | Chemical tags for introducing NMR-active spin labels or fluorescent dyes for FRET. | Used for measuring long-range distances via PRE-NMR or smFRET; choice of label can minimize perturbation to the native ensemble [13]. |

| FiveFold Algorithm Suite | Ensemble-based structure prediction framework combining five AI tools. | Used for de novo prediction of multiple conformational states, especially for IDPs with no known structures [14]. |

Navigating the Vast Search Space and Computational Cost of Accurate Predictions

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How can I reduce the generation of low-probability, unstable crystal structures during the initial sampling phase? A common inefficiency in Crystal Structure Prediction (CSP) is the generation of a large number of low-density, less-stable structures that consume computational resources. Implementing a machine learning-based filter before full structure relaxation can dramatically narrow the search space. Specifically, you can use predictors for likely space groups and target packing density to accept or reject randomly sampled lattice parameters before committing to the computationally expensive step of placing molecules in the lattice and performing relaxation. This "sample-then-filter" strategy has been shown to double the success rate of finding the experimentally observed structure compared to a purely random CSP approach [7].

FAQ 2: Why does prediction accuracy drop for chimeric or fused protein sequences, and how can I improve it? Default structure predictors like AlphaFold can lose accuracy when predicting non-natural, chimeric proteins (e.g., a structured peptide fused to a scaffold protein). The primary source of error is the construction of the Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA), where evolutionary signals for the individual protein parts are lost when the entire chimeric sequence is aligned at once [17]. To restore accuracy, use a Windowed MSA approach:

- Independently compute MSAs for the scaffold region and the tag (peptide) region.

- Merge these sub-alignments by concatenating them, inserting gap characters (

-) in the non-homologous positions (i.e., peptide-derived sequences have gaps across the scaffold region, and vice-versa). - Use this merged, windowed MSA as the input for structure prediction. This method has been shown to produce strictly lower RMSD values in 65% of test cases for fusion constructs [17].

FAQ 3: My molecular docking or virtual screening results lack robustness. How can I better prioritize candidate compounds? Relying on a single virtual screening method, such as molecular docking alone, can yield false positives and miss non-obvious structure-activity relationships. For more reliable hit identification, implement an orthogonal filtering strategy that combines structure-based and ligand-based methods [18]. A robust workflow integrates:

- Molecular Docking: To assess the complementarity of a compound to a target protein's binding pocket.

- QSAR Models: Machine learning models trained on experimental activity data can re-score and prioritize docked molecules, reducing false positives.

- Fragment-Based Generative Models: To creatively explore novel chemical spaces that retain desired pharmacophoric features but might be missed by traditional screening [18].

FAQ 4: What optimizer configurations can help navigate complex, high-dimensional energy landscapes more effectively? Standard optimizers like Adam can get trapped in local minima when dealing with the complex energy landscapes of protein folding or structure refinement. Integrating a Landscape Modification (LM) method with Adam can improve performance. LM dynamically adjusts gradients using a threshold parameter and a transformation function, which helps the optimizer avoid local minima and traverse flat or rough regions of the landscape more efficiently. A variant that integrates simulated annealing (LM SA) can further improve convergence stability. This hybrid approach has demonstrated faster convergence and better generalization on proteins not included in the training set compared to standard Adam [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Low Predictive Accuracy for Organic Crystal Structures

- Problem: The CSP workflow fails to find the experimentally observed crystal structure within a reasonable computational budget.

- Solution: Implement the SPaDe-CSP Workflow. This methodology uses machine learning to guide lattice sampling, drastically improving efficiency [7].

- Protocol:

- Data Curation: Obtain a high-quality training set from the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD). Filter for organic structures with Z' = 1, R-factor < 10, no solvent, and apply reasonable bounds for lattice parameters (e.g., 2 ≤ a, b, c ≤ 50 Å) [7].

- Model Training:

- Structure Generation & Relaxation:

- For a new molecule, predict its likely space groups and crystal density.

- During random lattice sampling, filter candidates by accepting only those whose parameters are consistent with the predicted density.

- Generate crystal structures using the filtered candidates and perform final structure relaxation using a Neural Network Potential (NNP) like PFP, which offers near-DFT accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost [7].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the SPaDe-CSP protocol:

Issue: Inaccurate Structure Prediction for Chimeric Proteins

- Problem: AlphaFold2/3 or ESMFold produces high-RMSD predictions for the tag region of a fusion protein, even when the tag and scaffold are accurately predicted in isolation.

- Solution: Apply the Windowed MSA Method. This technique preserves independent evolutionary signals for each protein part within the chimeric sequence [17].

- Protocol:

- Compute Independent MSAs: Use a tool like MMseqs2 (e.g., via the ColabFold API) to generate separate MSAs for the scaffold sequence and the peptide tag sequence.

- Merge MSAs with Gaps:

- Create a new alignment where the full sequence is the chimeric construct (scaffold-linker-tag).

- For sequences from the scaffold MSA, align them to the scaffold region of the chimera and fill the tag region with gap characters (

-). - For sequences from the tag MSA, align them to the tag region and fill the scaffold region with gaps.

- Structure Prediction: Feed this merged, windowed MSA into AlphaFold. This provides the model with the necessary co-evolutionary information for both domains without forcing an incorrect joint alignment [17].

The workflow for solving chimeric protein prediction is as follows:

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: Performance Comparison of CSP Workflows on a Test Set of 20 Organic Crystals [7]

| CSP Workflow | Key Methodology | Success Rate | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random CSP | Random selection of space groups and lattice parameters | ~40% | Baseline - exhaustive search |

| SPaDe-CSP | ML-guided sampling of space groups and density | ~80% | Doubles success rate, drastically reduces wasted computation |

Table 2: Performance of Structure Prediction Tools on a Peptide Benchmark (394 Targets) [17]

| Prediction Tool | Number of Targets with RMSD < 1 Å | Key Strengths / Context |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold-3 | 90 | Highest accuracy on isolated peptides |

| AlphaFold-2 | 34 | Standard baseline for performance |

| ESMFold-iterative | 21 | Language model-based, fast inference |

| AlphaFold-3 with Standard MSA (on fusions) | (Substantially lower) | Accuracy drops on chimeric proteins |

| AlphaFold-3 with Windowed MSA (on fusions) | (Restored accuracy) | 65% of cases show strictly lower RMSD |

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) | A curated repository of experimentally determined organic and metal-organic crystal structures used for training machine learning models and validating predictions [7]. |

| Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) [e.g., PFP] | Machine learning-based force fields that provide near-DFT level accuracy for structure relaxation at a fraction of the computational cost, crucial for high-throughput CSP [7]. |

| MACCSKeys / Molecular Fingerprints | A method for converting molecular structures into a numerical vector representation, enabling the use of machine learning algorithms to predict material properties like space group and density [7]. |

| Windowed MSA | A specialized technique for generating multiple sequence alignments for chimeric proteins that preserves independent evolutionary signals, restoring the accuracy of AlphaFold predictions [17]. |

| Structured State Space Sequence (S4) Model | A deep learning architecture for chemical language modeling that excels at capturing complex global properties in molecular strings (SMILES), useful for de novo molecular design and property prediction [20]. |

| Landscape Modification (LM) Optimizer | An enhanced optimizer that integrates with Adam to improve navigation of complex energy landscapes in protein structure prediction, helping to avoid local minima [19]. |

| Qsarna Platform | An online tool that integrates molecular docking, QSAR machine learning models, and fragment-based generative design into a unified virtual screening workflow [18]. |

Revolutionary Methodologies: Machine Learning, AI, and Neural Network Potentials in Action

Leveraging Machine Learning for Efficient Lattice Sampling and Space Group Prediction

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Data Preparation and Input

- Q: What are the common data formats for inputting crystal structures into ML models?

- A: Most machine learning potentials (MLFFs) and lattice sampling models are trained on data from materials databases like the Materials Project, which provide crystallographic information files (CIFs) and other standardized data formats containing atomic coordinates, space groups, and lattice parameters [8].

- Q: How can I handle configurationally disordered materials in my dataset?

- A: Universal Machine Learning Forcefields (MLFFs) have attained a level of accuracy suitable for representing disordered crystals from sources like the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [8].

Model Training and Implementation

- Q: What is a key requirement for training an accurate ML forcefield for CSP?

- A: Training universal MLFFs requires purpose-built datasets like MatPES, which are designed to make these models more efficient while retaining their level of predictive accuracy [8].

- Q: Can I use ML for CSP of organic molecules?

- A: Yes, workflows have been developed specifically for organic molecules. These combine machine learning-based lattice sampling with structure relaxation via a neural network potential, significantly increasing the probability of finding the experimentally observed crystal structure [21].

Prediction and Output Analysis

- Q: My CSP workflow generates too many low-density, unstable structures. How can I narrow the search?

- A: Implement a lattice sampling procedure that employs two machine learning models—a space group predictor and a packing density predictor. This reduces the generation of low-density, less-stable structures, effectively narrowing the search space [21].

- Q: What evaluation indicators can I use to ensure the stability of a predicted crystal structure?

- A: A robust method involves using the formation energy (predicted by a graph neural network model) and an empirical potential function (like the Lennard-Jones potential) as evaluation indicators. Bayesian optimization algorithms can then search for structures with lower energy and potentials approaching zero [22].

Computational Resources and Workflow

- Q: The computational cost for traditional CSP is too high. What are my options?

- A: Machine learning-based approaches address this issue directly. A developed CSP workflow that combines ML-based lattice sampling with structure relaxation via a neural network potential has been shown to achieve an 80% success rate with twice the efficiency of a random CSP [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low success rate in crystal structure prediction.

- Possible Cause 1: The initial lattice sampling is generating too many low-probability structures.

- Solution: Integrate a machine learning-based space group and packing density predictor into your sampling workflow to reduce the generation of low-density, less-stable structures [21].

- Possible Cause 2: The empirical potential used for relaxation is not accurate enough.

- Solution: Use a neural network potential for the structure relaxation phase instead of traditional empirical potentials [21].

Problem: Predicted crystal structures are not stable.

- Possible Cause: The evaluation criteria for the predicted structures are insufficient.

- Solution: Use a combination of formation energy (predicted by a GNN model) and Lennard-Jones potential as evaluation indicators. Apply Bayesian optimization to search for structures with lower energy and potentials near zero [22].

Problem: ML forcefield does not generalize well to new material types.

- Possible Cause: The training dataset is not comprehensive or universal enough.

- Solution: Train your model on purpose-built, universal datasets like MatPES, which are designed to cover a broad range of materials and improve model generalizability [8].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table: Key Quantitative Results from ML-Based CSP Workflows

| Study Focus | Success Rate | Comparative Efficiency | Key ML Components |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Molecule CSP [21] | 80% | Twice that of random CSP | Space group predictor, Packing density predictor, Neural network potential |

| Stable Crystal Prediction [22] | - | Ensures stability via multi-indicator evaluation | Graph Neural Network (formation energy), Lennard-Jones potential, Bayesian optimization |

Detailed Methodology: ML-Based CSP Workflow for Organic Molecules

This protocol is adapted from the workflow developed by Taniguchi and Fukasawa [21].

- Initial Setup and Data Preparation: Define the molecular structure of the organic compound to be predicted.

- Machine Learning-Based Lattice Sampling:

- Utilize a pre-trained machine learning model to predict the most probable space groups for the crystal.

- Simultaneously, use a separate ML model to predict the likely packing density.

- This step uses the ML predictions to constrain and guide the generation of initial crystal structures, avoiding low-probability regions of the crystallographic space.

- Structure Relaxation:

- Take the sampled lattice structures from the previous step.

- Relax these structures using a neural network potential to minimize their energy and achieve a stable configuration. This step moves the initial guesses towards local energy minima on the potential energy surface.

- Analysis and Validation:

- Compare the final relaxed structures against known experimental data (if available).

- Characterize the success rate based on the ability to find the experimentally observed structure and analyze which molecular and crystal parameters most influence the outcome.

Detailed Methodology: Ensuring Stability with Formation Energy and Empirical Potentials

This protocol is based on the work of Li et al. [22].

- Formation Energy Prediction:

- Input the candidate crystal structure into a trained Graph Neural Network (GNN) model.

- The GNN outputs a predicted formation energy for the structure. A more negative formation energy generally indicates a more thermodynamically stable structure.

- Empirical Potential Calculation:

- For the same candidate structure, calculate the Lennard-Jones (LJ) potential using its empirical formula.

- The LJ potential helps account for van der Waals interactions, and a value approaching zero is indicative of a stable configuration with balanced attractive and repulsive forces.

- Multi-Objective Optimization:

- Use a Bayesian optimization algorithm to search the crystallographic space.

- The optimizer is configured to find structures that simultaneously minimize the GNN-predicted formation energy and drive the Lennard-Jones potential towards zero.

- Stability Assessment:

- The final output is a set of predicted crystal structures that are stable according to both quantum-mechanical (formation energy) and empirical (LJ potential) criteria.

Workflow Visualization

ML-Driven Crystal Structure Prediction Workflow

ML Forcefield Training & Stability Assessment

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item Name | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Materials Project Database [8] | A materials database providing crucial crystallographic and thermodynamic information for training ML models and assessing polymorph competition. |

| MatPES Dataset [8] | A purpose-built dataset designed for training universal machine learning forcefields (MLFFs) to improve their efficiency and predictive accuracy. |

| Machine Learning Forcefields (MLFFs) [8] | Universal potentials used for rapid prediction of crystal structure with near electronic structure accuracy, enabling study of disordered and glassy materials. |

| Space Group Predictor (ML Model) [21] | A machine learning model that predicts the most likely space groups for a given molecule, constraining the initial lattice sampling space. |

| Packing Density Predictor (ML Model) [21] | A machine learning model that predicts the likely packing density, helping to reduce the generation of low-density, unstable crystal structures during sampling. |

| Neural Network Potential [21] | A potential energy function represented by a neural network, used for relaxing initially sampled crystal structures to their stable configurations. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) Model [22] | Used to predict the formation energy of a candidate crystal structure, a key indicator of its thermodynamic stability. |

Implementing Neural Network Potentials for High-Accuracy, Low-Cost Structure Relaxation

The accurate prediction of crystal structures is a cornerstone of materials science and pharmaceutical development. For drug molecules, which often exhibit polymorphism (the ability to exist in multiple crystalline forms), the ability to comprehensively map the solid-form landscape is critical, as different polymorphs can have vastly different properties affecting drug solubility, stability, and bioavailability [23]. Traditional methods based on Density Functional Theory (DFT) provide high accuracy but are computationally prohibitive, often requiring hundreds of thousands of CPU hours for a single Crystal Structure Prediction (CSP) [23].

Neural Network Potentials (NNPs), also known as machine learning interatomic potentials, have emerged as a transformative technology. They are machine-learned models trained on quantum mechanical (QM) data that can approximate the solution of the Schrödinger equation, enabling simulations with near-DFT accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost [24]. This guide provides technical support for researchers implementing NNPs to achieve high-accuracy, low-cost structure relaxation, directly contributing to more efficient and accurate solid-state structure prediction.

NNP Basics: A Scientist's Toolkit

Table 1: Essential Components for NNP Implementation

| Component / Reagent | Function & Description | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reference QM Software | Generates training data by performing high-fidelity quantum mechanics calculations on atomic systems. | CP2K, Quantum Espresso, VASP (periodic); ORCA, Gaussian, Psi4 (molecular) [24]. |

| QM Reference Datasets | Curated collections of DFT calculations used to train and validate NNPs. | MPtrj (Materials Project), OC20/OC22 (Open Catalyst), ODAC23 (Metal-Organic Frameworks) [24]. |

| NNP Architecture / Model | The machine learning model that learns the mapping from atomic structure to energy and forces. | Allegro, MACE, ANI (ANI-1, ANI-2x), ACE, SchNet [25]. |

| Training & Workflow Software | Infrastructure packages that facilitate the training, fitting, and deployment of MLIPs. | Includes tools for data management, training loops, and running molecular dynamics [25]. |

| Validation Benchmarks | Standardized datasets and metrics to assess the performance and transferability of a trained NNP. | Matbench Discovery, OC20 S2EF task, formate decomposition datasets [26]. |

Troubleshooting Common NNP Implementation Issues

FAQ 1: My model's energy predictions are inaccurate and fail to reproduce benchmark results. What should I do?

Answer: This is a common issue often stemming from the quality and scope of the training data or the model's architecture.

- Verify Your Training Data: Ensure your dataset is large and diverse enough to represent the chemical space of your target system. The model cannot learn what it has not seen. For universal applications, leverage large, diverse datasets like OC20 (1.2 billion DFT relaxations) or OMat24 (118 million calculations) [24] [26].

- Check for Data Leakage and Correct Splits: Ensure that your training, validation, and test datasets are properly split and that there is no data leakage between them, which can lead to overly optimistic performance metrics.

- Assess Model Capacity and Architecture: For complex systems with many elements and interaction types, a simple NNP may be insufficient. Consider more expressive models like equivariant networks (e.g., MACE, Allegro, AlphaNet) which have demonstrated state-of-the-art accuracy across various benchmarks [26] [25].

- Compare to a Known Result: As a debugging heuristic, compare your model's performance on a small, known benchmark against an established model implementation. This can help isolate whether the problem is with your data, model, or training procedure [27].

FAQ 2: My molecular dynamics simulations with an NNP are numerically unstable, leading to crashes or unphysical configurations. How can I fix this?

Answer: Numerical instabilities often arise when the model is asked to make predictions on atomic configurations that are far outside its training domain.

- Inspect the Forces: Examine the force vectors predicted by the NNP before the crash. Extremely large forces are a clear indicator that the model is in a region of the potential energy surface (PES) it was not trained on.

- Expand the Training Data: The most robust solution is to augment your training dataset with configurations that sample the problematic regions of the PES. Techniques like active learning or adversarial sampling can be used to automatically identify and include these configurations in subsequent training cycles.

- Validate with a Simple Test: Start with a simple simulation that you are confident your model should handle, such as a short relaxation of a stable crystal structure, before proceeding to more demanding tasks like high-temperature MD or phase transitions [27].

- Check for Incorrect Shapes or Numerical Issues: As with any deep learning model, ensure there are no silent bugs like incorrect tensor shapes or numerical instability (e.g.,

NaN/Infvalues) in the model's operations [27].

FAQ 3: How do I choose the right NNP for my specific application, such as pharmaceutical CSP or catalysis?

Answer: The choice involves a trade-off between accuracy, computational speed, and ease of use. Consider the following:

- For High Accuracy in Complex Systems: Modern equivariant models like MACE, Allegro, and AlphaNet have shown superior performance in accurately modeling diverse interactions, from molecular crystals to surface catalysis [26] [25]. For example, AlphaNet achieved a force MAE of 42.5 meV/Å on a formate decomposition dataset, outperforming other models [26].

- For Organic Molecules and Drug-Like Compounds: The ANI (ANAKIN-ME) family of potentials, such as ANI-1 and ANI-2x, are well-established and optimized for organic molecules containing H, C, N, O [25]. These have been successfully integrated into automated CSP protocols [23].

- For Speed and Scalability: If simulating very large systems or long time scales, consider the model's computational efficiency. Frame-based models like AlphaNet are designed to eliminate expensive tensor operations, offering high inference speeds [26].

- Leverage Pre-Trained Models: Before training a new potential from scratch, check if a pre-trained universal NNP (U-MLIP) is available that covers the chemical elements in your system. This can save significant time and resources [25].

Experimental Protocols & Performance Data

Protocol: An Automated CSP Workflow Using an NNP

A fully automated, high-throughput CSP protocol using a purpose-built NNP (Lavo-NN) has been demonstrated for pharmaceutical compounds [23]. The methodology is as follows:

- Initial Structure Generation: Generate a diverse set of initial crystal packing candidates for the target molecule.

- NNP-Driven Relaxation and Ranking: Use the specialized NNP to relax the generated structures and rank them by their predicted lattice energy. The NNP replaces expensive DFT calculations in this critical, costly step.

- High-Throughput Execution: Run the generation and relaxation phases as scalable, cloud-based workflows.

- Validation: Compare the low-energy predicted structures against known experimental polymorphs from databases.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of an Automated NNP-Based CSP Protocol [23]

| Metric | Result | Context & Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Cost | ~8,400 CPU hours per CSP | A significant reduction compared to other protocols which can require 100,000s of CPU hours. |

| Retrospective Benchmark | 49 unique, drug-like molecules | Covers a broad range of pharmaceutical compounds. |

| Polymorph Recovery | 110 out of 110 experimental polymorphs matched | Demonstrates the protocol's high degree of accuracy and comprehensiveness. |

| Real-World Application | Successful identification and ranking of polymorphs from PXRD patterns alone. | Proves utility in resolving experimental ambiguities and guiding lab work. |

Protocol: Benchmarking a New NNP on Diverse Materials

To validate the generalizability and accuracy of a new NNP like AlphaNet, a comprehensive benchmarking protocol against multiple standardized datasets is employed [26]:

- Dataset Selection: Use several publicly available datasets that cover different types of interatomic interactions and system types:

- Formate Decomposition: For catalytic surface reactions.

- Defected Graphene: For modeling inter-layer sliding and van der Waals forces.

- Zeolites: For complex, porous frameworks.

- OC20/OC2M: For general catalysis applications.

- Matbench Discovery WBM: For materials property prediction.

- Model Training: Train the NNP on the training splits of these datasets.

- Performance Quantification: Evaluate the model on the standard test splits using key metrics:

- Force Mean Absolute Error (MAE): Critical for accurate molecular dynamics.

- Energy MAE: Important for relative stability and property prediction.

- Comparison to SOTA: Compare the results against other state-of-the-art NNPs like NequIP, EquiformerV2, and SchNet.

Table 3: Sample Benchmarking Results for AlphaNet on Various Datasets [26]

| Dataset / Task | Key Metric | AlphaNet Performance | Competitor Performance (e.g., NequIP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formate Decomposition | Force MAE (meV/Å) | 42.5 | 47.3 |

| Defected Graphene | Force MAE (meV/Å) | 19.4 | 60.2 |

| OC2M (S2EF) | Energy MAE (eV) | 0.24 | ~0.35 (SchNet) |

| Matbench Discovery | F1 Score | 0.808 (AlphaNet-S) | Approaches >0.83 of larger models |

Technical Diagrams

NNP Troubleshooting Decision Tree

Core NNP Architecture Concept

Applying Large Language Models for Synthesis Route and Precursor Prediction

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key advantages of using Large Language Models (LLMs) over traditional methods for predicting synthesizability and precursors?

A1: LLMs fine-tuned for chemistry, such as the Crystal Synthesis LLM (CSLLM) framework, demonstrate superior accuracy in predicting synthesizability and identifying suitable precursors. The CSLLM achieves a state-of-the-art accuracy of 98.6% in classifying synthesizable crystal structures, significantly outperforming traditional screening methods based on thermodynamic stability (formation energy ≥0.1 eV/atom, 74.1% accuracy) and kinetic stability (lowest phonon frequency ≥ -0.1 THz, 82.2% accuracy) [9]. Furthermore, specialized LLMs for organic synthesis, like SynAsk, can be integrated with external chemistry tools to predict synthetic routes and answer complex questions, overcoming the limitations of rigid, template-based traditional systems [28] [29].

Q2: My model is generating unrealistic or chemically impossible precursors. How can I reduce these "hallucinations"?

A2: Hallucinations often occur due to a lack of domain-specific training. To mitigate this:

- Employ Domain-Focused Fine-Tuning: Fine-tune a base LLM on high-quality, curated chemical datasets. For example, the SynAsk model was created by fine-tuning the Qwen LLM with domain-specific organic chemistry data, which refines its ability to provide professional chemical dialogue and accurate information [29].

- Use a Structured Text Representation: Convert crystal structures into an efficient, non-redundant text format. The CSLLM framework uses a "material string" that integrates essential crystal information (space group, lattice parameters, atomic species, and Wyckoff positions), providing the model with a clear and consistent input format [9].

- Integrate with External Knowledge Bases and Tools: Connect the LLM to databases and cheminformatics tools. SynAsk uses a framework to seamlessly access a chemistry knowledge base and tools for tasks like molecular information retrieval and reaction prediction, grounding its responses in real data [29].

Q3: What data is required to fine-tune an LLM for solid-state synthesis prediction, and how should it be prepared?

A3: A robust dataset requires both positive and negative examples.

- Positive Samples: Collect experimentally confirmed synthesizable crystal structures from databases like the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD). For instance, the CSLLM used 70,120 ordered crystal structures from ICSD [9].

- Negative Samples: Constructing reliable negative samples (non-synthesizable structures) is critical. One effective method is to use a pre-trained Positive-Unlabeled (PU) learning model to screen large theoretical databases (e.g., the Materials Project). Structures with a low synthesizability score (e.g., CLscore <0.1) can be selected as negative examples. The CSLLM dataset included 80,000 such non-synthesizable structures, creating a balanced dataset for training [9].

- Precursor Data: For precursor prediction, data must include known synthetic reactions and their corresponding precursors, often sourced from specialized reaction databases [9] [28].

Q4: How can I validate the synthesis routes and precursors proposed by an LLM?

A4: Do not rely solely on the LLM's output. Validation is a multi-step process:

- Cross-Reference with Known Data: Use tools integrated with the LLM platform (e.g., molecular information retrieval in SynAsk) to check proposed precursors and reactions against established chemical literature and databases [29].

- Calculate Reaction Energetics: Use combinatorial analysis and calculate reaction energies to assess the thermodynamic feasibility of the proposed synthetic pathways [9].

- Leverage Accurate Physical Models: Use the LLM for initial screening, then validate the top candidates with more accurate, albeit computationally expensive, methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT) or Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) to verify stability [9] [30].

Quantitative Performance Data

The table below summarizes the performance metrics of key LLM frameworks as reported in recent literature.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarks of LLMs in Synthesis Prediction

| Model / Framework Name | Primary Task | Reported Accuracy / Performance | Key Comparative Method & Its Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal Synthesis LLM (CSLLM) [9] | 3D Crystal Synthesizability Prediction | 98.6% accuracy | Formation energy (≥0.1 eV/atom): 74.1% accuracy |

| Crystal Synthesis LLM (CSLLM) [9] | Synthetic Method Classification | 91.0% accuracy | Not Specified |

| Crystal Synthesis LLM (CSLLM) [9] | Solid-State Precursor Prediction (Binary/Ternary) | 80.2% success rate | Not Specified |

| SynAsk [29] | General Organic Synthesis Q&A | Outperforms other open-source models with >14B parameters on chemistry benchmarks. | Relies on integration with external tools for high accuracy. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fine-tuning a Synthesizability Prediction LLM (CSLLM Workflow)

This protocol outlines the methodology for developing a specialized LLM to predict the synthesizability of inorganic crystal structures [9].

1. Dataset Curation

- Objective: Create a balanced dataset of synthesizable and non-synthesizable crystal structures.

- Positive Samples: Select ~70,000 crystal structures from the ICSD. Apply filters for ordered structures, a maximum of 40 atoms per cell, and a maximum of 7 different elements.

- Negative Samples:

- Gather a large pool of theoretical structures from sources like the Materials Project (~1.4 million structures).

- Use a pre-trained PU learning model to assign a synthesizability score (CLscore) to each structure.

- Select the ~80,000 structures with the lowest CLscores (e.g., <0.1) as high-confidence negative examples.

- Data Representation: Convert all crystal structures into the "material string" text format. This format includes space group symbol, lattice parameters, and a concise list of atomic species with their Wyckoff positions.

2. Model Fine-tuning

- Base Model: Start with a large, general-purpose LLM (e.g., models from the LLaMA family).

- Input Format: The "material string" serves as the text input to the model.

- Task: Fine-tune the LLM as a classifier to predict a binary output: "synthesizable" or "non-synthesizable."

- Training: Use standard supervised learning techniques on the curated dataset, splitting it into training, validation, and test sets to evaluate performance and avoid overfitting.

3. Validation and Testing

- Hold-Out Test Set: Report the final prediction accuracy on the unseen test portion of the dataset.

- Generalization Test: Challenge the model with additional complex structures, such as those with large unit cells that were not present in the training data, to demonstrate real-world robustness (CSLLM achieved 97.9% accuracy here) [9].

Protocol: Building an LLM Agent for Organic Synthesis (SynAsk Workflow)

This protocol describes the creation of an LLM-powered platform that answers questions and performs tasks in organic synthesis by integrating with external tools [29].

1. Foundation Model Selection

- Criteria: Choose an open-source LLM with a sufficient number of parameters (e.g., >14 billion) to ensure robust reasoning capabilities. The Qwen series was selected for SynAsk based on its strong performance on benchmarks (MMLU, C-Eval) and compatibility with the integration framework [29].

2. Model Fine-tuning and Prompt Refinement

- Supervised Fine-Tuning: Perform an initial round of fine-tuning using a high-quality dataset of chemical dialogues and instructions. This specializes the model's knowledge towards organic chemistry.

- Prompt Engineering: Develop and iteratively test optimized prompt templates. These prompts guide the model to act as a skilled chemist and a proficient tool user, improving the relevance of its responses and its ability to correctly select and use external tools.

3. Tool Integration via a Chaining Framework

- Framework: Use a platform like LangChain to create a pipeline that connects the fine-tuned LLM to a suite of chemistry tools.

- Available Tools: The suite may include:

- A chemical knowledge base for information retrieval.

- Tools for molecular property calculation.

- Reaction prediction and retrosynthesis planners.

- Workflow: The user's question is processed by the LLM, which decides whether to answer based on its internal knowledge or to use an external tool. The tool's result is then fed back to the LLM, which formulates a final, coherent answer for the user.

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: LLM synthesizability prediction workflow.

Diagram 2: LLM agent tool-use workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools and Data for LLM-Driven Synthesis Prediction

| Item Name | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| ICSD (Inorganic Crystal Structure Database) [9] | Database | Primary source of experimentally confirmed, synthesizable crystal structures used for training and benchmarking LLMs. |

| Materials Project / CCDC [9] [31] | Database | Sources of theoretical and experimental crystal structures used for generating negative training samples and validation. |

| SMILES / SELFIES [28] [29] | Chemical Representation | A text-based notation for molecules, enabling LLMs to process and generate chemical structures as sequences. |

| PU Learning Model [9] | Computational Model | Used to screen large databases of theoretical structures to generate reliable negative (non-synthesizable) samples for training data. |

| Universal Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (UMA) [30] | Force Field | Provides highly accurate and fast energy and force calculations for validating the stability of predicted crystal structures. |

| LangChain [29] | Software Framework | Enables the integration of an LLM with external chemistry tools and databases, creating an powerful agent for synthesis planning. |

Utilizing Ensemble Methods for Modeling Protein Conformational Diversity

The classical sequence-structure-function paradigm of molecular biology has been updated to a sequence-conformational ensemble-function paradigm, recognizing that proteins are dynamic systems that interconvert between multiple conformational states rather than existing as single, rigid structures [32]. These ensembles are foundational to all protein functions, with the relative populations of different states determining biological activity and regulation. The energy landscape concept provides the physical framework for understanding these ensembles, where lower energy states are more populated, and minor changes in stability can shift populations between inactive and active states [32].

In solid-state structure prediction research, accurately modeling these ensembles is crucial for improving prediction accuracy, especially for understanding allosteric mechanisms, drug binding, and the functional implications of mutations. Experimental techniques like X-ray crystallography, cryo-EM, and NMR capture snapshots of these states, but computational methods are required to fully explore the conformational landscape [33] [32].

Theoretical Framework: Energy Landscapes and Allostery

The Energy Landscape Concept

The energy landscape maps all possible conformations a protein can populate. Functional proteins typically have landscapes characterized by a dominant native basin containing multiple similar substates with small energy differences between them [32]. This organization allows for population shifts in response to cellular signals.

Key Principles:

- Proteins constantly interconvert between conformational states with varying energies

- More stable conformations are more highly populated

- Changes in state populations are required for cellular function

- Wild-type proteins under physiological conditions often predominantly populate inactive states, with minor populations of active, ligand-free states [32]

Allostery and Population Shifts

Allostery represents a fundamental functional hallmark of conformational ensembles. Without multiple protein conformations, allostery - and thus biological regulation - would not be possible [32].

Allosteric Mechanisms:

- Stabilization: Binding events (covalent or noncovalent) or mutations stabilize active states

- Frustration Relief: Conformational changes relieve local energetic conflicts, propagating through the structure

- Pathway Preference: Pre-existing propagation pathways with lower kinetic barriers are favored

- Population Shift: The ensemble shifts from inactive to active states upon stabilization [32]

Table: Key Concepts in Conformational Ensemble Theory

| Concept | Description | Functional Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Landscape | Mapping of all possible conformations and their energies | Determines population distributions and transition probabilities |

| Conformational Selection | Binding partners select compatible shapes from existing ensemble | Explains molecular recognition without induced-fit forcing |

| Population Shift | Change in relative abundances of conformational states | Mechanism for allosteric regulation and activation |

| Bistable Switch | System that can toggle between two dominant states | Enables binary signaling responses in cellular pathways |

Computational Methods for Ensemble Analysis

DANCE: Dimensionality Analysis for Protein Conformational Exploration