Advancing Material Discovery: A Comprehensive Guide to Self-Supervised Pretraining Strategies for Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of self-supervised pretraining (SSL) strategies for learning powerful material representations, a critical technology for accelerating drug discovery and materials science.

Advancing Material Discovery: A Comprehensive Guide to Self-Supervised Pretraining Strategies for Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of self-supervised pretraining (SSL) strategies for learning powerful material representations, a critical technology for accelerating drug discovery and materials science. We first establish the foundational principles of SSL and its transformative potential in overcoming the labeled-data bottleneck in biomedical research. The article then delves into specific methodological frameworks—including contrastive, predictive, and multimodal learning—applied to both molecular and material graphs, highlighting real-world applications in property prediction. We address key practical challenges such as data imbalance and structural integrity, offering optimization techniques and novel augmentation strategies. Finally, we present a rigorous comparative analysis of SSL performance against supervised benchmarks across diverse property prediction tasks, synthesizing evidence to guide researchers and development professionals in implementing these cutting-edge approaches for more efficient and accurate material design and drug development.

The SSL Paradigm Shift: Foundations and Principles for Material Representation Learning

Biomedical research stands at a critical juncture, where data generation capabilities have far outpaced our capacity for manual annotation. The reliance on supervised learning (SL) has created a fundamental bottleneck: the scarcity of expensive, time-consuming, and often inconsistent expert-labeled data. This limitation is particularly pronounced in specialized domains where annotation requires rare expertise, such as medical image interpretation, molecular property prediction, and clinical text analysis. The emerging paradigm of self-supervised learning (SSL) offers a transformative path forward by leveraging the inherent structure within unlabeled data to learn meaningful representations. This technical guide examines the core principles, methodologies, and applications of SSL within biomedical contexts, providing researchers with the framework to overcome label scarcity and unlock the full potential of their data.

The transition from supervised dependence to self-supervised freedom represents more than a methodological shift—it constitutes a fundamental reimagining of how machine learning systems can acquire knowledge from biomedical data. Where supervised approaches require explicit human guidance through labels, self-supervised methods discover the underlying patterns and relationships autonomously, creating representations that capture the essential structure of the data itself. This capability is especially valuable in biomedical domains where unlabeled data exists in abundance, but labeled examples remain scarce due to the cost, time, and expertise required for annotation.

The Fundamental Challenge: Limitations of Supervised Learning in Biomedical Contexts

The Label Scarcity Problem

Supervised learning's performance strongly correlates with the quantity and quality of available labeled data, creating significant barriers in biomedical applications. Experimental validation of molecular properties is both costly and resource-intensive, leading to a scarcity of labeled data and increasing reliance on computational exploration [1]. This scarcity is compounded by the concentration of available labeled data in narrow regions of chemical space, introducing bias that hampers generalization to unseen compounds [1]. The fundamental limitation lies in supervised models' tendency to rely heavily on patterns observed within the training distribution, resulting in poor generalization to out-of-distribution compounds—a critical failure point in drug discovery where the most crucial compounds often lie beyond the training data [1].

In medical imaging, the labeling process is particularly burdensome, as expert annotation requires specialized medical knowledge and is highly time-consuming [2]. This challenge manifests across multiple biomedical domains, from molecular property prediction to medical image analysis and clinical text understanding. The consequence is that supervised approaches often fail to generalize reliably to novel, unseen examples that differ from the training distribution, limiting their real-world applicability in dynamic biomedical environments.

Quantitative Performance Comparisons

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Supervised vs. Self-Supervised Learning on Medical Imaging Tasks

| Task | Dataset Size | Supervised Learning Accuracy | Self-Supervised Learning Accuracy | Performance Gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumonia Diagnosis (Chest X-ray) | 1,214 images | 87.3% | 85.1% | -2.2% |

| Alzheimer's Diagnosis (MRI) | 771 images | 83.7% | 79.8% | -3.9% |

| Age Prediction (Brain MRI) | 843 images | 81.5% | 77.2% | -4.3% |

| Retinal Disease (OCT) | 33,484 images | 94.2% | 93.7% | -0.5% |

Recent comparative analyses reveal that in scenarios with small training sets, supervised learning often maintains a performance advantage over self-supervised approaches [2]. However, this advantage diminishes as dataset size increases, as evidenced by the minimal performance gap on the larger retinal disease dataset. This relationship highlights a crucial trade-off: while supervised learning can be effective with sufficient labeled data, its performance degrades rapidly as label scarcity increases. In contrast, self-supervised methods demonstrate more consistent performance across data regimes, particularly when leveraging large-scale unlabeled data during pre-training.

Core Principles of Self-Supervised Learning for Biomedical Data

Theoretical Foundations

Self-supervised learning operates on the principle of generating supervisory signals directly from the structure of the data itself, without human annotation. This approach leverages the natural information richness present in biomedical data through pretext tasks—learning objectives designed to force the model to learn meaningful representations by predicting hidden or transformed parts of the input. The fundamental advantage lies in SSL's ability to leverage vast quantities of unlabeled data that would be impractical to annotate manually, thus learning robust feature representations that capture the underlying data manifold.

The theoretical foundation rests on the assumption that biomedical data possesses inherent structure—spatial, temporal, spectral, or semantic relationships—that can be exploited for representation learning. In medical images, this might include anatomical symmetries or tissue texture patterns; in molecular data, chemical structure relationships; in clinical text, linguistic patterns and semantic relationships. By designing pretext tasks that require understanding these inherent structures, SSL models learn representations that transfer effectively to downstream supervised tasks with limited labels.

Domain-Specific Adaptations

The effectiveness of self-supervised learning in biomedical contexts depends critically on adapting general SSL principles to domain-specific characteristics. For hyperspectral images (HSIs), which capture rich spectral signatures revealing vital material properties, researchers have developed Spatial-Frequency Masked Image Modeling (SFMIM) [3]. This approach recognizes that hyperspectral images are composed of two inherently coupled dimensions: the spatial domain across 2D image coordinates, and the spectral domain across wavelength or frequency bands.

In molecular property prediction, where generalization to out-of-distribution compounds is crucial, novel bilevel optimization approaches leverage unlabeled data to interpolate between in-distribution (ID) and out-of-distribution (OOD) data [1]. This enables the model to learn how to generalize beyond the training distribution, addressing the fundamental limitation of standard molecular prediction models that tend to rely heavily on patterns observed within the training data.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Dual-Domain Masked Image Modeling for Hyperspectral Data

Protocol Objective: To learn robust spatial-spectral representations from unlabeled hyperspectral imagery through simultaneous masking in spatial and frequency domains.

Methodology Details: The SFMIM framework employs a transformer-based encoder and introduces a novel dual-domain masking mechanism [3]:

Input Processing: The input HSI cube X ∈ ℝ^(B×S×S) is divided into N = S^2 non-overlapping patches spatially, where each patch captures the complete spectral vector for its spatial location.

Spatial Masking: Random selection of patches are masked and replaced with trainable mask tokens, forcing the network to infer missing spatial information from unmasked patches.

Frequency Domain Masking: Application of Fourier transform to the spectral dimension followed by selective filtering (masking) of specific frequency components.

Reconstruction Objective: The model learns to reconstruct both masked spatial patches and missing frequency components, capturing higher-order spectral-spatial correlations.

Implementation Specifications:

- Transformer architecture follows standard Vision Transformer with multi-head self-attention

- Embedding dimension: 512

- Masking ratio: 60% for spatial domains, 40% for frequency domains

- Optimization: AdamW with learning rate of 1e-4

- Pre-training epochs: 800 on unlabeled data

Bilevel Optimization for Molecular Property Prediction

Protocol Objective: To address covariate shift in molecular property prediction by leveraging unlabeled data to densify scarce labeled distributions.

Methodology Details: This approach introduces a novel bilevel optimization framework that interpolates between labeled training data and unlabeled molecular structures [1]:

Architecture: The model consists of a meta-learner (standard MLP) and a permutation-invariant learnable set function μ_λ as a mixer.

Input Processing: For each labeled molecule xi ∼ 𝒟train, context points {cij}j=1^mi are drawn from unlabeled data 𝒟context.

Mixing Operation: The set function μλ mixes xi^(lmix) and Ci^(lmix) as a set, outputting a single pooled representation x~i^(lmix) = μλ({xi^(lmix), Ci^(lmix)}) ∈ ℝ^(B×1×H).

Bilevel Optimization:

- Inner loop: Updates task learner parameters θ to minimize training loss L_T(θ,λ)

- Outer loop: Updates set function parameters λ to minimize meta-validation loss L_V(λ,θ*(λ))

Implementation Specifications:

- Context sample size: M = 50 per minibatch

- Hidden dimension: H = 512

- Mixing layer: l_mix = 3 (of 6 total layers)

- Optimization: Inner loop (Adam, lr=1e-3), Outer loop (hypergradient descent)

Biomedical Natural Language Processing with Limited Labels

Protocol Objective: To extract meaningful information from clinical text with minimal labeled examples through specialized pre-training strategies.

Methodology Details: Recent advances in biomedical NLP have demonstrated several effective approaches for low-label scenarios:

Continual Pre-training: Adaptation of general-purpose LLMs to biomedical domains through continued pre-training on domain-specific corpora [4]. For example, Llama3-ELAINE-medLLM was continually pre-trained on Llama3-8B, targeted for the biomedical domain and adapted for multilingual languages (English, Japanese, and Chinese).

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG): Enhancement of LLM knowledge by leveraging external information to improve response accuracy for medical queries [4]. The MedSummRAG framework employs a fine-tuned dense retriever, trained with contrastive learning, to retrieve relevant documents for medical summarization.

Adaptive Biomedical NER: Development of specialized models like AdaBioBERT that build upon BioBERT with adaptive loss functions combining Cross Entropy and Conditional Random Field losses to optimize both token-level accuracy and sequence-level coherence [4].

Implementation Specifications:

- Pre-training data: Biomedical corpora (PubMed, clinical notes)

- Architecture modifications: Domain-specific tokenization, entity-aware attention

- Fine-tuning: Multi-task learning on related biomedical tasks

- Evaluation: Cross-dataset generalization tests

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Self-Supervised Biomedical Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transformer Architectures | Model Architecture | Captures long-range dependencies in sequential and structured data | Hyperspectral image analysis [3], Clinical text processing [4] |

| Masked Autoencoders | Pre-training Framework | Reconstruction-based pre-training for representation learning | Spatial-spectral feature learning [3], Medical image understanding |

| Bilevel Optimization | Training Strategy | Separates model and hyperparameter updates for improved generalization | Molecular property prediction [1], Out-of-distribution generalization |

| Contrastive Learning | Pre-training Objective | Learns representations by contrasting positive and negative samples | Biomedical image similarity [2], Retrieval augmentation [4] |

| Domain-Specific Corpora | Data Resource | Provides domain-adapted pre-training data | Biomedical text continuual pre-training [4], Clinical code generation |

| Retrieval-Augmented Generation | Inference Framework | Enhances knowledge with external database access | Medical question answering [4], Clinical decision support |

Performance Evaluation and Comparative Analysis

Quantitative Benchmarking

Table 3: Performance Gains of Self-Supervised Methods Across Biomedical Domains

| Domain | Task | Supervised Baseline | Self-Supervised Approach | Performance Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperspectral Imaging | HSI Classification | 85.3% (Supervised CNN) | 92.7% (SFMIM) [3] | +7.4% |

| Molecular Property Prediction | OOD Generalization | 0.63 AUROC | 0.79 AUROC (Bilevel Optimization) [1] | +25.4% |

| Medical Text Processing | Relation Triplet Extraction | 0.42 F1 (Fine-tuned) | 0.492 F1 (Gemini 1.5 Pro Zero-shot) [4] | +17.1% |

| Clinical QA | Radiology QA | 68.5 F1 | 80-83 F1 (DPO + Encoder-Decoder) [4] | +15.5% |

| Biomedical NER | Entity Recognition | 0.886 F1 (BioBERT) | 0.892 F1 (AdaBioBERT) [4] | +0.6% |

The performance gains observed across diverse biomedical applications demonstrate the transformative potential of self-supervised approaches, particularly in scenarios involving out-of-distribution generalization, limited labeled data, and complex multimodal relationships. The most significant improvements appear in tasks where supervised approaches struggle with distributional shift or extreme label scarcity.

Efficiency and Scalability Considerations

Beyond raw performance metrics, self-supervised methods offer significant advantages in training efficiency and computational resource utilization. Research has shown that specialized domain-adaptive pre-training can match or surpass traditionally trained biomedical language models while incurring up to 11 times lower training costs [5]. This efficiency stems from the ability of SSL methods to leverage abundant unlabeled data during pre-training, creating robust foundational representations that require minimal fine-tuning on downstream tasks.

In hyperspectral imaging, the SFMIM approach demonstrates rapid convergence during fine-tuning, highlighting the efficiency of representation learning during pre-training [3]. Similarly, in molecular property prediction, the bilevel optimization framework enables more sample-efficient learning by intelligently interpolating between labeled and unlabeled data distributions [1]. These efficiency gains are particularly valuable in biomedical contexts where computational resources may be constrained relative to the volume and complexity of available data.

Future Directions and Emerging Trends

The field of self-supervised learning for biomedical applications continues to evolve rapidly, with several promising research directions emerging. Fully autonomous research systems like DREAM demonstrate the potential for LLM-powered systems to conduct complete scientific investigations without human intervention, achieving efficiencies over 10,000 times greater than average scientists in certain contexts [6]. These systems leverage the UNIQUE paradigm (Question, codE, coNfIgure, jUdge) to autonomously interpret data, generate scientific questions, plan analytical tasks, and validate results.

Another significant trend involves the development of more sophisticated multimodal self-supervised approaches that can jointly learn from diverse data modalities—genomic sequences, medical images, clinical text, and molecular structures. The integration of retrieval-augmented generation with domain-specific pre-training has shown particular promise for complex tasks like medical text summarization, where it achieves significant improvements in ROUGE scores over baseline methods [4].

As self-supervised methodologies mature, we anticipate increased focus on interpretability, robustness verification, and seamless integration with existing biomedical research workflows. The ultimate goal remains the creation of systems that can not only overcome label scarcity but also accelerate the pace of biomedical discovery through more efficient, generalizable, and insightful analysis of complex biological data.

Self-supervised learning (SSL) is a machine learning paradigm that addresses a fundamental challenge in modern artificial intelligence: the reliance on large, expensively annotated datasets. Technically defined as a subset of unsupervised learning, SSL distinguishes itself by generating supervisory signals directly from the structure of unlabeled data, eliminating the need for manual labeling in the initial pre-training phase [7]. This approach has become particularly valuable in specialized domains like materials science and drug development, where expert annotations are scarce, costly, and time-consuming to obtain [2] [8].

The core mechanism of SSL involves a two-stage framework: pretext task learning followed by downstream task adaptation. In the first stage, a model is trained on a pretext task—a surrogate objective where the labels are automatically derived from the data itself. This process forces the model to learn meaningful, general-purpose data representations. In the second stage, these learned representations are transferred to solve practical downstream tasks (e.g., classification or regression) via transfer learning, often requiring only minimal labeled data for fine-tuning [9] [7]. This framework is especially powerful for materials research, where deep learning models show superior accuracy in capturing structure-property relationships but are often limited by small, annotated datasets [10].

SSL methods are broadly categorized into three families based on their learning objective:

- Contrastive Learning: Differentiates between similar and dissimilar data points.

- Generative Learning: Reconstructs original or missing parts of the input data.

- Predictive Pretext Tasks: Predicts predefined transformations or relationships within the data.

The following sections provide a technical dissection of these core principles, their methodologies, and their application in scientific domains.

Contrastive Learning Principles

Contrastive learning operates on a simple yet powerful principle: it learns representations by discriminating between similar (positive) and dissimilar (negative) data samples [9]. The core idea is to train an encoder to produce embeddings where "positive" pairs (different augmented views of the same instance) are pulled closer together in the latent space, while "negative" pairs (views from different instances) are pushed apart [9] [7].

The foundational workflow involves creating augmented views of each input data point. For an input image or material structure graph x_i, two stochastically augmented versions, x_i^1 and x_i^2, are generated. These augmented views are then processed by an encoder network f(·) to obtain normalized embeddings z_i^1 and z_i^2. The learning objective is formalized using a contrastive loss function, such as the normalized temperature-scaled cross entropy (NT-Xent) used in SimCLR [8]. The loss for a positive pair (i, j) is computed as:

L_contrastive = -log [exp(sim(z_i, z_j)/τ) / ∑_(k=1)^(2N) 1_[k≠i] exp(sim(z_i, z_k)/τ)]

where sim(·, ·) is the cosine similarity function, τ is a temperature parameter, and the denominator involves a sum over one positive and numerous negative examples [8]. This loss function effectively trains the model to recognize the inherent invariance between different views of the same object or material structure.

Diagram 1: Contrastive learning workflow for material representations.

Key Experimental Protocols in Contrastive Learning

Implementing contrastive learning for material science applications requires careful design of several components. The following protocols are critical for success:

Data Augmentation Strategy: For material graphs or structures, augmentations must preserve fundamental physical properties while creating meaningful variations. Graph-based augmentations that inject noise without structurally deforming material graphs have proven effective [10]. In remote sensing for materials analysis, domain-specific augmentations like spectral jittering and band shuffling can be employed [8].

Negative Sampling Strategy: Early contrastive methods required large batches or memory banks to maintain diverse negative samples, which was computationally expensive. Recent advancements like BYOL (Bootstrap Your Own Latent) and SimSiam eliminate this requirement by using architectural innovations like momentum encoders and stop-gradient operations to prevent model collapse [11].

Encoder Architecture Selection: The choice of encoder depends on the data modality. For molecular structures, graph neural networks (GNNs) are natural encoders. For crystalline materials, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) or vision transformers may be more appropriate.

The EnSiam method addresses instability in negative-sample-free approaches by using ensemble representations, generating multiple augmented samples from each instance and utilizing their ensemble as stable pseudo-labels, which analysis shows reduces gradient variance during training [11].

Table 1: Contrastive SSL Methods and Their Key Characteristics

| Method | Core Mechanism | Negative Samples | Key Innovation | Material Science Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SimCLR | End-to-end contrastive | Large batch required | Simple framework with MLP projection head | Baseline for material property prediction |

| MoCo | Dictionary look-up | Memory bank | Maintains consistent negative dictionary | Large-scale material database pre-training |

| BYOL | Self-distillation | Not required | Momentum encoder with prediction network | Learning invariant material representations |

| SimSiam | Simple siamese | Not required | Stop-gradient operation without momentum encoder | Resource-constrained material research |

| EnSiam | Ensemble learning | Not required | Multiple augmentations for stable targets | Improved training stability for material graphs |

Generative Learning Methods

Generative self-supervised learning takes a fundamentally different approach from contrastive methods by focusing on reconstructing original or missing parts of the input data. The core principle is to train models to capture the underlying data distribution by learning to generate plausible samples, which implicitly requires learning meaningful representations of the data's structure [9] [7].

The most prominent generative SSL approach is the masked autoencoder (MAE) framework, which has shown remarkable success across computer vision, natural language processing, and scientific domains [12]. In this approach, a significant portion of the input (e.g., image patches, molecular graph nodes, or gene sequences) is randomly masked. The model is then trained to reconstruct the missing information based on the remaining context. The reconstruction loss between the original and predicted values serves as the supervisory signal [8] [13]. For materials research, this could involve masking atom features in a molecular graph or spectral bands in material characterization data.

Another important generative approach is through variational autoencoders (VAEs), which learn to encode input data into a latent probability distribution and then decode samples from this distribution to reconstruct the original input [14] [7]. The encoder compresses the input into a lower-dimensional latent space, forcing the network to capture the most salient features. The decoder then attempts to reconstruct the original input from this compressed representation. Denoising autoencoders represent a variant where the model is given partially corrupted input and must learn to restore the original, uncorrupted data [14].

Diagram 2: Generative learning with masked autoencoding.

Implementation Protocols for Generative SSL

Implementing generative SSL for materials research involves several key design decisions:

Masking Strategy: The masking approach significantly impacts what representations the model learns. For material graphs, random masking of node features provides minimal inductive bias, while structured masking based on chemical properties (e.g., functional groups) incorporates domain knowledge [13]. In remote sensing for materials analysis, spatial-spectral masking based on local variance in spectral bands has proven effective [8].

Reconstruction Target: Models can be trained to reconstruct raw input features (e.g., pixel values, atom types) or more abstract representations. The MaskFeat approach demonstrated that using HOG (Histogram of Oriented Gradients) features as reconstruction targets can be more effective than raw pixels for certain vision tasks [12].

Architecture Design: The autoencoder architecture must be tailored to the data modality. For molecular structures, graph transformers with attention mechanisms can effectively capture long-range dependencies, while for crystalline materials, U-Net-like architectures with skip connections may be more appropriate for preserving fine structural details.

In single-cell genomics (with parallels to molecular representation learning), masked autoencoders have demonstrated particular effectiveness, outperforming contrastive methods—a finding that diverges from trends in computer vision [13]. This underscores the importance of domain-specific adaptation in generative SSL.

Table 2: Performance of Generative SSL in Scientific Domains

| Domain | SSL Method | Masking Strategy | Downstream Task | Performance Gain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell Genomics | Masked Autoencoder | Random & Gene Program | Cell-type prediction | 2.4-4.5% macro F1 improvement [13] |

| Remote Sensing | Masked Autoencoder | Spatial-spectral | Land cover classification | 2.7% accuracy improvement with 10% labels [8] |

| Computer Vision | Masked Autoencoder | Random patches (75%) | Image classification | Competitive with supervised pre-training [12] |

| Medical Imaging | Denoising Autoencoder | Partial corruption | Disease diagnosis | Mixed results in small datasets [2] |

Predictive Pretext Tasks

Predictive pretext tasks represent the earliest approach in self-supervised learning, where models are trained to predict automatically generated pseudo-labels derived from the data itself [9] [14]. These tasks are designed to force the model to learn semantic representations by solving artificial but meaningful prediction problems that don't require human annotation.

The most common predictive pretext tasks include:

Rotation Prediction: Images or material structures are rotated by random multiples of 90°, and the model must predict the applied rotation angle [11] [14]. This simple task requires the model to understand object orientation and spatial relationships—critical for recognizing crystal structures or molecular conformations.

Relative Patch Prediction: The input is divided into patches, and the model must predict the relative spatial position of a given patch with respect to a central patch [14]. This task encourages learning spatial context and part-whole relationships within materials.

Jigsaw Puzzle Solving: Patches from an image are randomly permuted, and the model must predict the correct permutation used to rearrange them [11] [14]. Solving this task requires understanding how different parts of a material structure relate to form a coherent whole.

Exemplar Discrimination: Each instance and its augmented versions are treated as a separate surrogate class, and the model must learn to distinguish between different instances while being invariant to augmentations [14]. This approach shares similarities with contrastive learning but is framed as a classification problem.

Diagram 3: Predictive pretext task framework.

Experimental Design for Predictive Pretext Tasks

Implementing predictive pretext tasks for material representation requires careful design:

Transformation Selection: The chosen transformations should align with invariances important for downstream tasks. For material property prediction, rotation and scaling invariance might be crucial for recognizing crystalline structures from different orientations, while color invariances would be less relevant than in natural images.

Task Difficulty Calibration: The pretext task must be challenging enough to force meaningful learning but not so difficult that it becomes impossible to solve. In jigsaw puzzles, the permutation set size and Hamming distance between permutations significantly affect task difficulty and representation quality [14].

Architecture Adaptation: Most predictive pretext tasks use a standard encoder-classifier architecture, where the encoder learns general representations and the classifier solves the specific pretext task. For material graphs, the encoder would typically be a graph neural network adapted to process the specific pretext task objective.

While predictive pretext tasks were foundational in SSL, they have been largely superseded by contrastive and generative approaches in recent state-of-the-art applications. However, they remain valuable for specific domain applications and as components in multi-task learning frameworks [9] [14].

SSL Evaluation Frameworks and Protocols

Rigorous evaluation is essential for assessing the quality of representations learned through self-supervised methods. The SSL community has established several standardized protocols to measure how well pre-trained models transfer to downstream tasks, particularly important for scientific domains like materials research where labeled data is scarce [12].

The primary evaluation protocols include:

Linear Probing: After self-supervised pre-training, the encoder weights are frozen, and a single linear classification layer is trained on top of the learned features for the downstream task. This protocol tests the quality of the frozen representations without allowing further feature adaptation [12] [13].

Fine-Tuning: The entire pre-trained model (or most of it) is further trained on the downstream task with labeled data. This allows the model to adapt its representations to the specific target domain and typically yields higher performance than linear probing [12].

k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) Classification: A kNN classifier is applied directly to the frozen feature representations without any additional training. This protocol is computationally efficient and provides a quick assessment of the representation space structure [12].

Low-Shot Evaluation: Models are evaluated with progressively smaller subsets of labeled training data to measure data efficiency—particularly relevant for material science where annotations are scarce [2].

Recent benchmarking studies have found that in-domain linear and kNN probing protocols are generally the best predictors for out-of-domain performance across various dataset types and domain shifts [12]. This is valuable for material research where models may be applied to novel material classes not seen during pre-training.

Table 3: SSL Evaluation Protocols and Their Characteristics

| Evaluation Protocol | Parameters Updated | Computational Cost | Measured Capability | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Probing | Only final linear layer | Low | Quality of frozen features | Initial benchmarking, feature quality assessment |

| End-to-End Fine-Tuning | All parameters | High | Adaptability of representations | Final application deployment |

| k-NN Classification | No training | Very Low | Representation space structure | Quick evaluation, clustering quality |

| Low-Shot Learning | Varies | Medium | Data efficiency | Label-scarce environments like material research |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing self-supervised learning for material representations requires both computational "reagents" and methodological components. The following table details essential resources and their functions for building effective SSL frameworks in materials research.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for SSL in Material Science

| Research Reagent | Type | Function in SSL Pipeline | Example Implementations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Networks | Architecture | Encodes material graph structures into latent representations | GCN, GAT, GraphSAGE for molecular graphs |

| Data Augmentation Strategies | Preprocessing | Creates positive pairs for contrastive learning or corrupted inputs for generative tasks | Graph noise injection, spectral jittering, rotation [10] [8] |

| Contrastive Loss Functions | Optimization Objective | Measures similarity between representations in contrastive learning | NT-Xent (SimCLR), Triplet Loss, InfoNCE [8] |

| Reconstruction Loss | Optimization Objective | Measures fidelity of reconstructions in generative methods | Mean Squared Error, Cross-Entropy, HOG feature loss [12] |

| Masking Strategies | Algorithmic Component | Creates self-supervision signal by hiding portions of input | Random masking, gene-program masking [13], spatial-spectral masking [8] |

| Momentum Encoder | Architectural Component | Provides stable targets in negative-free contrastive learning | BYOL, MoCo teacher-student framework [11] |

| Memory Bank | Data Structure | Stores negative examples for contrastive learning without large batches | MoCo dictionary approach [9] |

Self-supervised learning represents a paradigm shift in how machine learning models acquire representations, particularly impactful for scientific domains like materials research where labeled data is scarce but unlabeled data is abundant. The three core SSL families—contrastive, generative, and predictive pretext tasks—offer complementary approaches to learning meaningful representations without human supervision.

For material property prediction, recent advances demonstrate that supervised pretraining with surrogate labels can establish new benchmarks, achieving significant performance gains ranging from 2% to 6.67% improvement in mean absolute error (MAE) over baseline methods [10]. Furthermore, graph-based augmentation techniques that inject noise without structurally deforming material graphs have shown particular promise for improving model robustness [10].

As SSL continues to evolve, promising research directions for materials science include multi-modal SSL (combining structural, spectral, and textual data), foundation models for materials pre-trained on large-scale unlabeled data, and domain-adaptive SSL that can generalize across different material classes and characterization techniques. By reducing dependency on expensive labeled datasets, SSL enables more scalable, accessible, and cost-effective AI solutions for accelerating materials discovery and development [8].

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) represent a specialized class of deep learning algorithms specifically designed to process graph-structured data, which capture relationships among entities through nodes (vertices) and edges (links). In molecular and materials science, this structure naturally represents atomic systems: atoms serve as nodes, and chemical bonds form the edges connecting them [15]. This abstraction enables GNNs to directly operate on molecular structures, encoding both the compositional and relational information critical for predicting chemical properties and behaviors.

The significance of GNNs lies in their ability to overcome limitations of traditional molecular representation methods. Conventional approaches, such as molecular fingerprints (e.g., Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints) or string-based representations (e.g., SMILES), often produce sparse outputs, compress two-dimensional spatial information inefficiently, or struggle to maintain invariance—where the same molecule can yield different representations [16]. In contrast, GNNs generate dense, adaptive representations that preserve structural information and demonstrate permutation invariance, meaning the representation remains consistent regardless of how the graph is ordered [16]. This capability positions GNNs as powerful tools for applications ranging from drug discovery and material property prediction to fraud detection and recommendation systems [17].

Core Architectural Principles of GNNs

The Message Passing Framework

The fundamental operating principle of most GNNs is message passing, a mechanism that allows nodes to incorporate information from their local neighborhoods [18]. This process can be conceptualized as a series of steps that are repeated across multiple layers:

- Node Initialization: Each node begins with an initial feature vector. In molecular graphs, these features might include atomic number, charge, orbital hybridization, or other chemical attributes [18].

- Message Creation: Each node creates a "message" based on its current state, often through a learned transformation function. Similarly, each edge may also contribute to the message based on its own features (e.g., bond type, bond length) [19].

- Message Exchange: Nodes send their created messages to all adjacent neighbors connected by edges [18].

- Aggregation: Each node collects the messages from its neighbors and combines them using an order-invariant function such as sum, mean, or maximum. This operation ensures the GNN's output is unchanged by permutations in node ordering [18].

- Update: Each node updates its own representation by combining its previous state with the aggregated neighborhood information, typically through another learned function like a neural network layer [18].

With each successive message passing layer, a node gathers information from a wider neighborhood—after one layer, it knows about immediate neighbors; after two layers, it knows about neighbors' neighbors, and so on [18]. This progressive feature propagation enables GNNs to capture complex dependencies within molecular structures.

GNN Variants and Specialized Architectures

Several specialized GNN architectures have been developed to enhance the capabilities of the basic message-passing framework:

- Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs): Approximate convolutional operations on graphs by performing normalized aggregations of neighborhood features, enabling effective node representation learning [20].

- Graph Attention Networks (GATs): Incorporate attention mechanisms that assign learned importance weights to neighbors during aggregation, allowing models to focus on more relevant parts of the graph [19].

- Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (KANs): Recent variants like KA-GNNs replace standard multilayer perceptrons with learnable univariate functions based on the Kolmogorov-Arnold representation theorem, improving expressivity and parameter efficiency while offering enhanced interpretability [19]. Fourier-series-based functions within KANs have demonstrated particular effectiveness in capturing both low-frequency and high-frequency structural patterns in molecular graphs [19].

- Mamba-Enhanced Models: Newer frameworks such as MOL-Mamba combine GNNs with state-space models to better capture long-range dependencies in molecular structures, addressing the "over-squashing" limitation of traditional GNNs where information from many nodes is compressed into fixed-size vectors [21].

Table 1: Key GNN Variants for Molecular Representation

| Architecture | Core Mechanism | Advantages | Molecular Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| GCN | Normalized neighborhood aggregation | Computational efficiency, simplicity | Molecular property prediction, node classification |

| GAT | Attention-weighted aggregation | Focus on relevant substructures | Protein interface prediction, reaction analysis |

| KA-GNN | Learnable univariate activation functions | Enhanced interpretability, parameter efficiency | Molecular property prediction, drug discovery |

| Mamba-GNN | State-space model integration | Long-range dependency capture | Complex polymer modeling, electronic property prediction |

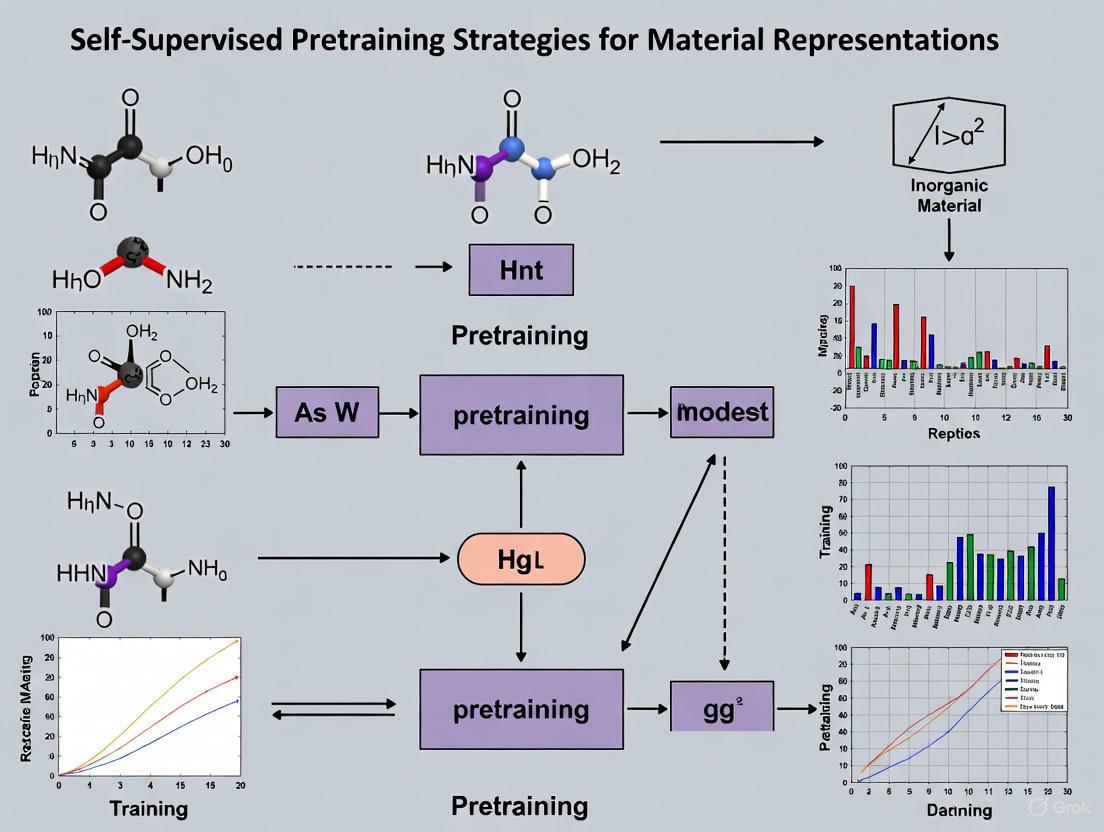

Self-Supervised Pretraining Strategies for Materials

Self-supervised learning (SSL) has emerged as a powerful paradigm for addressing the limited availability of labeled molecular data, which is often expensive and time-consuming to obtain experimentally [22]. SSL frameworks pretrain GNNs on unlabeled molecular structures using automatically generated pretext tasks, enabling the model to learn rich structural representations before fine-tuning on specific property prediction tasks with limited labeled data.

Pretext Tasks for Molecular Graphs

Research has identified several effective SSL strategies for molecular graphs:

- Node- and Edge-Level Pretraining: This approach trains the model to reconstruct masked node and edge attributes based on their surrounding context [22]. By learning to predict missing atomic properties or bond types from molecular structure, the GNN develops a nuanced understanding of local chemical environments.

- Graph-Level Pretraining: The model learns to discriminate between original molecular graphs and corrupted versions, or to predict global graph properties derived from the structure itself without experimental labels [22].

- Ensemble Multilevel Pretraining: The most effective approach combines node-, edge-, and graph-level pretext tasks, enabling the model to capture both local structural patterns and global molecular characteristics [22]. Research on polymer property prediction demonstrates that this ensemble approach decreases root mean square errors by 28.39% and 19.09% for electron affinity and ionization potential predictions, respectively, in data-scarce scenarios compared to supervised learning without pretraining [22].

Knowledge-Enhanced Representation Learning

Advanced SSL frameworks integrate domain knowledge to further enhance representations:

- Multimodal Fusion: Approaches like MOL-Mamba jointly learn from structural information (atom-level and fragment-level graphs) and electronic descriptors (quantum chemical properties), creating more comprehensive molecular representations that reflect both geometric and electronic characteristics [21].

- Chemical Knowledge Integration: Methods such as KCL (Knowledge Contrastive Learning) incorporate chemical knowledge graphs or topological descriptors like persistent homology fingerprints as additional supervision signals during pretraining, grounding the learned representations in established chemical principles [21].

Table 2: Self-Supervised Pretraining Strategies for Molecular GNNs

| Strategy | Pretext Task | Learning Objective | Reported Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attribute Masking | Reconstruct masked node/edge features | Captures local chemical contexts | Improves data efficiency by 19-28% on quantum property prediction [22] |

| Graph Contrastive Learning | Discriminate between original and corrupted graphs | Learns invariant graph representations | Enhances performance on polymer property prediction with limited labels [22] |

| Multimodal Fusion | Align structural and electronic representations | Integrates multiple molecular views | Outperforms state-of-the-art baselines across 11 chemical-biological datasets [21] |

| Knowledge Integration | Incorporate chemical knowledge graphs | Grounds representations in domain knowledge | Improves interpretability and model performance on downstream tasks [21] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Implementation of KA-GNNs for Molecular Property Prediction

Recent work on Kolmogorov-Arnold GNNs (KA-GNNs) provides a detailed experimental framework for molecular property prediction [19]:

Architecture Variants:

- KA-GCN: Integrates Fourier-based KAN modules into Graph Convolutional Networks. Node embeddings are initialized by passing concatenated atomic features and neighboring bond features through a KAN layer. Message passing follows the GCN scheme with node feature updates via residual KANs instead of traditional MLPs [19].

- KA-GAT: Incorporates KAN modules into Graph Attention Networks, using attention mechanisms to weight neighborhood aggregation while leveraging learnable activation functions for enhanced expressivity [19].

Fourier-KAN Formulation: The Fourier-based KAN layer employs trigonometric basis functions to approximate complex mappings:

This formulation enables effective capture of both low-frequency and high-frequency patterns in molecular graphs, with theoretical approximation guarantees grounded in Carleson's theorem and Fefferman's multivariate extension [19].

Experimental Setup:

- Datasets: Evaluation across seven molecular benchmarks including quantum chemistry (QM9), physical chemistry (ESOL, FreeSolv), and physiology (BBBP, Tox21) datasets [19].

- Training Protocol: Models trained with Adam optimizer, learning rate of 0.001, batch size of 128, and early stopping with patience of 100 epochs [19].

- Evaluation Metrics: Mean absolute error (MAE) for regression tasks, area under the ROC curve (AUC-ROC) for classification tasks [19].

MOL-Mamba Hierarchical Representation Learning

The MOL-Mamba framework implements a sophisticated approach for integrating structural and electronic information [21]:

Hierarchical Graph Construction:

- Atom-Level Graph (𝒢𝐴): Standard molecular graph with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges [21].

- Fragment-Level Graph (𝒢𝐹): Generated by masking edges in the atom-level graph to create molecular fragments, which then serve as nodes connected by inter-fragment bonds [21].

Architecture Components:

- Atom & Fragment Mamba-Graph (MG): Processes both atom-level and fragment-level graphs using Mamba-enhanced GNNs for hierarchical structural reasoning [21].

- Mamba-Fusion Encoder (MF): Integrates structural representations with electronic descriptors (𝒟𝐸) using a hybrid Mamba-Transformer architecture [21].

Training Framework:

- Structural Distribution Collaborative Training: Aligns representations across atom and fragment levels to capture hierarchical chemical information [21].

- E-semantic Fusion Training: Jointly optimizes structural and electronic representation learning using contrastive objectives [21].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for GNN Experimentation

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| PyTorch Geometric (PyG) | Graph deep learning library | KA-GNN implementation, graph data processing [19] |

| Deep Graph Library (DGL) | Graph neural network framework | MOL-Mamba architecture, message passing operations [21] |

| Molecular Datasets | Benchmark performance evaluation | QM9, ESOL, FreeSolv, BBBP, Tox21 [19] |

| Fourier-KAN Layers | Learnable activation functions | Replace MLPs in GNN components for enhanced expressivity [19] |

| Mamba Modules | State-space model components | Capture long-range dependencies in molecular graphs [21] |

| Electronic Descriptors | Quantum chemical features | Integrate with structural data for multimodal learning [21] |

Performance Analysis and Quantitative Assessment

Table 4: Comparative Performance of Advanced GNN Architectures

| Model | Dataset | Metric | Performance | Baseline Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KA-GNN | Multiple molecular benchmarks | Prediction accuracy | Consistent outperformance | Superior to conventional GNNs in accuracy and efficiency [19] |

| KA-GNN | Molecular property prediction | Computational efficiency | Higher throughput | Improved training and inference speed [19] |

| MOL-Mamba | 11 chemical-biological datasets | Property prediction AUC | State-of-the-art results | Outperforms GNN and Graph Transformer baselines [21] |

| Self-supervised GNN | Polymer property prediction | RMSE (electron affinity) | 28.39% reduction | Versus supervised learning without pretraining [22] |

| Self-supervised GNN | Polymer property prediction | RMSE (ionization potential) | 19.09% reduction | Versus supervised learning without pretraining [22] |

Quantitative evaluations demonstrate that GNNs incorporating advanced architectural components consistently outperform conventional approaches. KA-GNNs show both accuracy and efficiency improvements across diverse molecular benchmarks [19], while frameworks like MOL-Mamba achieve state-of-the-art results by effectively integrating structural and electronic information [21]. The significant error reduction achieved by self-supervised approaches in data-scarce scenarios highlights the practical value of pretraining strategies for real-world materials research [22].

Future Research Directions

The evolution of GNNs for molecular and materials representation continues to advance along several promising trajectories:

- Interpretability and Explainability: While current GNNs offer improved interpretability through mechanisms like attention weights and KAN visualization, developing quantitative evaluation frameworks for model explanations remains challenging [23]. Future work needs to establish standardized benchmarks for assessing the chemical relevance of explanatory subgraphs identified by GNNs [23].

- Long-Range Dependency Modeling: Overcoming the "over-squashing" effect in GNNs through architectures like Mamba-enhanced models and graph transformers represents a critical frontier for capturing complex interactions in large molecular systems [21].

- Multiscale Representation Learning: Developing unified frameworks that seamlessly integrate quantum, atomistic, and mesoscale representations will enable more comprehensive materials modeling across different spatial and temporal scales [16].

- Foundation Models for Materials Science: The creation of large-scale, transferable molecular representation models pretrained on extensive unlabeled molecular databases could potentially revolutionize materials discovery, analogous to the impact of foundation models in natural language processing [22].

As GNN methodologies continue to mature, their integration with domain knowledge, multimodal data sources, and self-supervised learning paradigms will further enhance their capability to represent and predict complex molecular and material behaviors, accelerating discovery across chemical, biological, and materials science domains.

The scarcity of labeled data presents a significant bottleneck in scientific domains such as materials science and drug development. The pretraining-finetuning workflow addresses this challenge by leveraging abundant unlabeled data to build generalized foundational models, which are subsequently adapted to specialized prediction tasks with limited labeled examples. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of this paradigm, detailing its theoretical foundations, methodological frameworks, and practical implementation protocols. Within the context of material representations research, we demonstrate how self-supervised pretraining strategies capture vital spatial-spectral correlations and material properties, enabling rapid convergence and state-of-the-art performance on specialized prediction tasks. We present comprehensive experimental protocols, quantitative benchmarks, and essential toolkits to equip researchers with practical resources for implementing this workflow in scientific discovery pipelines.

In material science and pharmaceutical research, generating high-quality labeled data for specific property predictions is often prohibitively expensive, time-consuming, or technically infeasible. Traditional supervised learning approaches face fundamental limitations under these data-constrained conditions, particularly when deploying parameter-intensive transformer architectures that typically require massive labeled datasets for effective training. The pretraining-finetuning workflow emerges as a transformative solution, creating a knowledge bridge from easily accessible unlabeled data to precise predictive models for specialized tasks.

This paradigm operates through two distinct yet interconnected phases: (1) Self-supervised pretraining, where models learn generalizable representations and fundamental patterns from vast unlabeled datasets without human annotation, and (2) Supervised finetuning, where these pretrained models are specifically adapted to target tasks using limited labeled data [24] [25]. This approach mirrors human learning—first acquiring broad conceptual knowledge before specializing in specific domains—thereby maximizing knowledge transfer while minimizing annotation requirements. Within material representations research, this workflow enables models to learn intrinsic material properties, spectral signatures, and spatial relationships during pretraining, which can then be efficiently directed toward predicting specific material characteristics, stability, or functional properties during finetuning.

Theoretical Foundations and Definitions

Conceptual Frameworks

The pretraining-finetuning workflow embodies principles of transfer learning, where knowledge gained from solving one problem is applied to different but related problems [25]. In the context of deep learning, this manifests as a two-stage process that separates general pattern recognition from task-specific adaptation:

Pre-training involves training a model on a large, diverse dataset to learn general representations, patterns, and features fundamental to the data domain without task-specific labels [24]. For material representations, this might include learning spectral signatures, spatial relationships, or structural patterns across diverse material classes. This stage establishes what can be considered "scientific intuition" within the model—a foundational understanding of domain-specific principles that enables generalization beyond specific labeled examples.

Fine-tuning takes a pre-trained model and further trains it on a smaller, task-specific labeled dataset to adapt its general knowledge to specialized applications [24] [26]. This process adjusts the model's weights to optimize performance for specific predictive tasks such as material classification, property prediction, or stability assessment. Unlike the pre-training phase which requires massive computational resources, fine-tuning is computationally efficient and can often be accomplished with limited hardware resources [25].

Evolution in the GenAI Era

The scale and implementation of these concepts have evolved significantly with advancements in generative AI. In the neural network era (pre-ChatGPT), pre-training typically involved manageable datasets on limited GPUs, while fine-tuning often added task-specific layers to frozen base models. In the contemporary GenAI era (2024/25), pre-training has become an industrial-scale operation requiring thousands of GPUs and trillion-token datasets, while fine-tuning now involves direct weight adjustments across all model layers without structural modifications [25]. This evolution has made transfer learning the default mode in modern AI systems, with models inherently designed for adaptation to diverse tasks through prompting or minimal fine-tuning.

Technical Methodology: A Dual-Phase Approach

Self-Supervised Pretraining Strategies

Self-supervised pretraining employs innovative pretext tasks that generate supervisory signals directly from the structure of unlabeled data, enabling models to learn meaningful representations without manual annotation. These strategies are particularly valuable for scientific data where unlabeled samples are abundant but labeled examples are scarce.

Masked Image Modeling (MIM) has emerged as a powerful pretraining approach for visual and scientific data. In this paradigm, portions of the input data are deliberately masked or corrupted, and the model is trained to reconstruct the missing elements based on the visible context [3] [24]. For hyperspectral data analysis in material science, the Spatial-Frequency Masked Image Modeling (SFMIM) approach introduces a novel dual-domain masking mechanism:

- Spatial Masking: Random patches within the spatial dimensions of the hyperspectral cube are masked, forcing the model to infer missing spatial information from surrounding context across different spectral channels [3].

- Frequency Domain Masking: The input spectra undergo Fourier transformation, after which selective frequency components are removed, requiring the model to predict missing frequencies and learn salient spectral features [3].

This dual-domain approach enables the model to capture higher-order spectral-spatial correlations fundamental to material property analysis. The technical implementation involves dividing the input hyperspectral cube X∈ℝ^(B×S×S) into N=S^2 non-overlapping patches, with each patch y_i∈ℝ^B containing the complete spectral vector for its spatial location [3]. These patches are projected into an embedding space, combined with positional encodings, and processed through a transformer encoder to learn comprehensive representations.

Other pretraining techniques include Next Sentence Prediction (NSP) for understanding contextual relationships between data segments, and Causal Language Modeling (CLM) for autoregressive generation tasks [24]. The selection of appropriate pretraining strategies depends on the data modality, target tasks, and computational constraints.

Supervised Finetuning Approaches

Once a model has established foundational knowledge through pretraining, finetuning adapts this general capability to specialized predictive tasks using limited labeled data. Several finetuning methodologies have proven effective for scientific applications:

Transfer Learning: This approach uses weights from pre-trained models as a starting point, building upon existing domain understanding to accelerate convergence and improve performance on specialized tasks [24]. According to a Stanford University survey, this method reduces training time by approximately 40% and improves model accuracy by up to 15% compared to training from scratch [24].

Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT): Utilizing labeled datasets, SFT enables precise model adjustments for specific predictive tasks. The Hugging Face Transformers library provides optimized Trainer APIs that facilitate this process with comprehensive training features including gradient accumulation, mixed precision training, and metric logging [26].

Domain-Specific Fine-Tuning: This technique involves training the model on specialized datasets to enhance its understanding of domain-specific terminology, patterns, and contexts. For pharmaceutical applications, this might involve finetuning on molecular structures, assay results, or clinical trial data to optimize predictive performance for drug development tasks [24].

A critical consideration during finetuning is preventing overfitting, where models become too specialized to the finetuning dataset and lose generalization capability. Techniques to mitigate this include regularization methods, careful learning rate selection, and progressive unfreezing of model layers.

Experimental Protocol: Implementation Framework

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end pretraining-finetuning workflow for material property predictions:

Case Study: SFMIM for Hyperspectral Data Analysis

The Spatial-Frequency Masked Image Modeling (SFMIM) approach provides a concrete implementation of this workflow for hyperspectral material analysis. The following diagram details its dual-domain masking strategy:

Implementation Protocol

Data Preparation and Preprocessing:

- Unlabeled Pretraining Data: Collect diverse hyperspectral cubes or material characterization data without labels. For SFMIM, format data as X∈ℝ^(B×S×S) with B spectral bands and S×S spatial dimensions.

- Labeled Finetuning Data: Prepare task-specific labeled datasets for target predictions (e.g., material properties, stability metrics). Ensure proper train/validation/test splits.

- Data Augmentation: Apply domain-appropriate augmentations including spatial transformations, spectral perturbations, and noise injection to enhance model robustness.

Model Architecture Configuration:

- Backbone Selection: Choose appropriate architecture (e.g., Vision Transformer, Factorized Transformer) based on data modality and computational constraints.

- Embedding Configuration: Project input patches into embedding space of dimension d using linear layer E∈ℝ^(d×B). Add positional embeddings to encode spatial information.

- Classifier Head: For finetuning, replace pretrained head with task-specific classification or regression layers.

Training Hyperparameters: Table: SFMIM Training Configuration

| Training Stage | Global Batch Size | Learning Rate | Epochs | Max Sequence Length | Weight Decay | Warmup Ratio | Deepspeed Stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-training | 256 | 1e-3 | 1 | 2560 | 0 | 0.03 | ZeRO-2 |

| Instruction Fine-tuning | 128 | 2e-5 | 1 | 2048 | 0 | 0.03 | ZeRO-3 |

Computational Requirements:

- Hardware: 8× A800 GPUs with 80GB memory for large-scale pretraining

- Training Time: Varies by dataset size and model complexity (typically days to weeks for pretraining, hours to days for finetuning)

- Optimization: Leverage mixed-precision training and distributed data parallelism for efficient scaling

Quantitative Performance Analysis

Benchmark Results

The effectiveness of the pretraining-finetuning workflow is demonstrated through comprehensive benchmarking across multiple datasets and tasks. The following table summarizes quantitative results from SFMIM implementation on hyperspectral classification benchmarks:

Table: SFMIM Performance on HSI Classification Benchmarks

| Dataset | Model Approach | Pretraining Strategy | Accuracy (%) | Convergence Speed | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indiana HSI | Supervised Baseline | No Pretraining | 85.2 | 1.0× (baseline) | High |

| Indiana HSI | MAEST | Spectral Masking Only | 89.7 | 1.8× | Medium |

| Indiana HSI | FactoFormer | Factorized Masking | 91.3 | 2.1× | Low |

| Indiana HSI | SFMIM (Proposed) | Dual-Domain Masking | 94.8 | 3.2× | Medium |

| Pavia University | Supervised Baseline | No Pretraining | 83.7 | 1.0× (baseline) | High |

| Pavia University | MAEST | Spectral Masking Only | 87.9 | 1.7× | Medium |

| Pavia University | FactoFormer | Factorized Masking | 90.5 | 2.3× | Low |

| Pavia University | SFMIM (Proposed) | Dual-Domain Masking | 93.2 | 3.5× | Medium |

| Kennedy Space Center | Supervised Baseline | No Pretraining | 79.8 | 1.0× (baseline) | High |

| Kennedy Space Center | MAEST | Spectral Masking Only | 84.3 | 1.9× | Medium |

| Kennedy Space Center | FactoFormer | Factorized Masking | 87.6 | 2.4× | Low |

| Kennedy Space Center | SFMIM (Proposed) | Dual-Domain Masking | 91.7 | 3.8× | Medium |

Ablation Studies

Ablation studies demonstrate the contribution of individual components within the pretraining-finetuning workflow:

Table: Component Ablation Analysis for SFMIM

| Model Variant | Spatial Masking | Frequency Masking | Dual-Domain Reconstruction | Accuracy (%) | Representation Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | 85.2 | Low |

| Spatial-Only | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | 88.4 | Medium |

| Frequency-Only | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | 87.9 | Medium |

| Sequential | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | 90.7 | High |

| SFMIM (Full) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 94.8 | Highest |

The results indicate that dual-domain masking with joint reconstruction achieves superior performance by capturing complementary spatial and spectral information, enabling more comprehensive material representations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Implementing the pretraining-finetuning workflow requires both computational frameworks and domain-specific tools. The following table details essential components for successful deployment in material science research:

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Pretraining-Finetuning Workflow

| Component | Function | Implementation Examples | Domain Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transformer Architecture | Base model for capturing long-range dependencies | Vision Transformer (ViT), SpectralFormer, Factorized Transformer | Spatial-spectral relationship modeling in material data |

| Self-Supervised Pretext Tasks | Generating supervisory signals from unlabeled data | Dual-domain masking, contrastive learning, context prediction | Learning intrinsic material properties without labels |

| Data Augmentation Framework | Enhancing dataset diversity and model robustness | Spatial transformations, spectral perturbations, noise injection | Improving generalization across material variants |

| Optimization Libraries | Efficient training and fine-tuning implementations | Hugging Face Transformers, PyTorch Lightning, DeepSpeed | Streamlining model development and deployment |

| Evaluation Benchmarks | Standardized performance assessment | HSI classification datasets, material property prediction tasks | Comparative analysis of model effectiveness |

| Visualization Tools | Interpreting model attention and representations | Attention map visualization, feature projection, spectral analysis | Understanding model focus and decision processes |

The pretraining-finetuning workflow represents a paradigm shift in developing predictive models for scientific domains with limited labeled data. By establishing a knowledge bridge from unlabeled data to specialized predictions, this approach maximizes information utilization while minimizing annotation costs. The SFMIM case study demonstrates how dual-domain self-supervision during pretraining enables comprehensive representation learning that transfers effectively to downstream material property predictions.

Future research directions include developing multimodal pretraining strategies that integrate diverse characterization data (spectral, structural, compositional), creating domain-adaptive finetuning techniques that maintain robustness across material classes, and establishing standardized benchmarks for evaluating material representation learning. As this workflow continues to evolve, it holds significant potential for accelerating discovery in materials science, pharmaceutical development, and other data-constrained scientific domains.

The rapid advancement of Machine Learning (ML), particularly Deep Neural Networks (DNN), has propelled the success of deep learning across various scientific domains, from Natural Language Processing (NLP) to Computer Vision (CV) [27]. Historically, most high-performing models were trained using labeled data, a process that is both costly and time-consuming, often requiring specialized knowledge for domains like medical data annotation [27]. To overcome this fundamental bottleneck, Self-Supervised Learning (SSL) has emerged as a transformative approach. SSL learns feature representations through pretext tasks that do not require manual annotation, thereby circumventing the high costs associated with annotated data [27]. The general framework involves training models on these pretext tasks and then fine-tuning them on downstream tasks, enabling the transfer of acquired knowledge [27]. This paradigm shift has powered a journey from foundational algorithms like Word2Vec to sophisticated frameworks such as BERT and DINOv3, establishing SSL as a cornerstone of modern AI research in science. This whitepaper details this evolution, with a specific focus on its implications for developing powerful representations in scientific fields, including materials research and drug development.

Foundational NLP Technologies: From Word2Vec to BERT

The emergence of SSL in NLP demonstrated for the first time that models could learn powerful semantic representations without explicit human labeling.

Word2Vec: Pioneering Word Embeddings

Introduced by researchers at Google in 2013, Word2vec provided a technique for obtaining vector representations of words [28]. These vectors capture semantic information based on the distributional hypothesis—words that appear in similar contexts have similar meanings [28].

- Architectures and Approach: Word2vec uses two shallow neural network architectures to produce distributed representations [28]:

- Continuous Bag-of-Words (CBOW): Predicts a target word given its surrounding context words. It acts like a 'fill in the blank' task and is generally faster to train [28].

- Skip-gram: Uses the current word to predict the surrounding window of context words. It tends to perform better for infrequent words [28].

- Mathematical Foundation: Both models learn vectors that maximize the log-probability of word contexts. The Skip-gram objective, for instance, seeks to maximize

∑i ∑j∈N ln Pr(wj+i | wi), whereNis the set of context indices [28]. - Impact and Limitations: Word2vec demonstrated that semantically similar words cluster in the vector space, enabling algebraic operations like

v("king") - v("man") + v("woman") ≈ v("queen")[29]. However, it generated static embeddings, meaning each word has a single representation regardless of context, which is a significant limitation for polysemous words.

BERT: The Bidirectional Breakthrough

BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers), introduced by Google in 2018, marked a revolutionary leap by learning contextual, latent representations of tokens [30] [31].

- Core Architecture: BERT is an "encoder-only" transformer architecture. The input representation is constructed by summing the token embeddings, position embeddings, and segment embeddings [30]. BERTBASE (110M parameters) uses 12 transformer layers, a hidden size of 768, and 12 attention heads, while BERTLARGE (340M parameters) uses 24 layers, a hidden size of 1024, and 16 heads [30] [31].

- Pre-training Objectives: BERT was pre-trained simultaneously on two novel tasks [30] [31]:

- Masked Language Modeling (MLM): 15% of tokens in the input sequence are randomly masked, and the model must predict the original vocabulary id of the masked word based on its bidirectional context. To mitigate the discrepancy between pre-training and fine-tuning, the masked token is not always replaced with the

[MASK]token [30]. - Next Sentence Prediction (NSP): The model receives pairs of sentences and learns to predict whether the second sentence logically follows the first in the original corpus, which helps it understand sentence relationships [30].

- Masked Language Modeling (MLM): 15% of tokens in the input sequence are randomly masked, and the model must predict the original vocabulary id of the masked word based on its bidirectional context. To mitigate the discrepancy between pre-training and fine-tuning, the masked token is not always replaced with the

- Performance and Evolution: BERT dramatically improved the state-of-the-art on 11 common NLP tasks, including question answering (SQuAD) and natural language inference (GLUE), in some cases surpassing human-level performance [31]. It spawned the field of "BERTology" and led to models like GPT and beyond, establishing the transformer as the foundational architecture for modern NLP [32].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Foundational SSL Models in NLP

| Feature | Word2Vec (2013) | BERT (2018) |

|---|---|---|

| Representation Type | Static word embeddings | Contextualized token representations |

| Core Architecture | Shallow neural network (CBOW/Skip-gram) | Deep Transformer Encoder |

| Training Objectives | Predict word given context (or vice versa) | Masked Language Modeling (MLM), Next Sentence Prediction (NSP) |

| Context Understanding | Local, window-based | Bidirectional, full-sequence |

| Key Innovation | Dense semantic vector space | Pre-training deep bidirectional representations |

| Primary Limitation | No context-dependent meanings | Computationally intensive pre-training |

The SSL Revolution in Computer Vision

Inspired by the success in NLP, SSL was rapidly adopted in computer vision, leading to novel frameworks that could learn visual representations from unlabeled images and videos.

Core Methodological Families in Visual SSL

SSL methods in vision can be broadly categorized based on their learning objective [27]:

- Contrastive Methods: Frameworks like MoCo (Momentum Contrast) and SimCLR learn representations by bringing different augmented views of the same image ("positives") closer in an embedding space while pushing apart views from different images ("negatives") [33] [34]. MoCo introduced a momentum encoder and a queue of negative samples to enable large-scale contrastive learning without immense batch sizes [33].

- Non-Contrastive Methods: Methods like BYOL (Bootstrap Your Own Latent) demonstrated that SSL could work without negative pairs altogether, avoiding potential pitfalls of negative sampling [33].

- Clustering-based & Generative Methods: Approaches like SwAV simultaneously cluster data while enforcing consistency between cluster assignments of different augmentations. Other methods use generative objectives like masked image modeling, inspired by BERT's MLM [27] [35].

The DINO Family: Emergence of Visual Foundation Models

The DINO (self-DIstillation with NO labels) framework and its successors represent a significant milestone in visual SSL [33].

- Core Mechanism: DINO employs a self-distillation approach where a student network is trained to match the output of a teacher network. Both networks receive different augmented views of the same image. The teacher's weights are an exponential moving average (EMA) of the student's weights, preventing mode collapse [33].

- Evolution and Scaling:

- DINOv2: Focused on scale, incorporating masked image modeling and a curated dataset of 142 million images. It delivered incredibly strong out-of-the-box performance without fine-tuning [33].

- DINOv3: Scaled further to a 7B parameter model trained on 1.7 billion images. It introduced techniques like Gram Anchoring to maintain dense feature quality over long training runs and high resolutions, setting new state-of-the-art results across vision benchmarks [33].

- Significance: DINO showed that Vision Transformers (ViTs) combined with SSL could surpass Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), leading to models that discover "objectness" without explicit supervision. Their embeddings can be directly used for tasks like segmentation, detection, and classification [33].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Modern Visual SSL Frameworks on Standard Benchmarks

| Model | Architecture | ImageNet Linear Eval. (%) | ImageNet k-NN Eval. (%) | Parameters | Key Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MoCo v2 [36] | ResNet-50 | 67.5 | 57.0 | ~24M | Momentum contrast with negative queue |

| SimCLR [33] | ResNet-50 | 69.3 | 58.5 | ~24M | Simple framework, strong augmentations |

| BYOL [33] | ResNet-50 | 70.6 | 57.0 | ~24M | Positive-only learning, no negatives |

| DINO [33] | ViT-S/16 | 73.8 | 63.9 | ~22M | Self-distillation with ViTs |

| DINOv2 [33] | ViT-g/14 | 79.2 | - | ~1B | Large-scale pre-training, curated data |

| DINOv3 [33] | ViT-H/14 | 81.5* | - | 7B | Gram Anchoring, extreme scale |

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit - Key Research Reagents in Modern SSL

| Tool / Reagent | Function in SSL Research |

|---|---|

| Vision Transformer (ViT) [33] | Base architecture that processes images as sequences of patches; thrives with SSL pre-training. |

| Momentum Encoder [33] [34] | A slowly updated copy of the main model that provides stable targets for self-distillation (e.g., in DINO, MoCo). |

| Exponential Moving Average (EMA) [33] | The mechanism for updating the teacher/model weights in self-distillation, preventing model collapse. |

| Masked Image Modeling (MIM) [35] | A pretext task where the model learns to reconstruct randomly masked patches of an image, analogous to BERT's MLM. |

| Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) [35] | A parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) method that adapts large pre-trained models to new domains with minimal cost. |

| Contrastive Loss (InfoNCE) [36] | The objective function used in contrastive learning that distinguishes positive sample pairs from negative ones. |

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking

Robust and standardized evaluation is critical for assessing the quality of SSL-learned representations.

Standard Evaluation Protocols