Advanced Strategies for Optimizing Reaction Parameters in Novel Materials and Pharmaceutical Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide to modern reaction optimization strategies for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Advanced Strategies for Optimizing Reaction Parameters in Novel Materials and Pharmaceutical Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to modern reaction optimization strategies for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the evolution from traditional one-factor-at-a-time approaches to advanced machine learning-driven methodologies, including Design of Experiments (DoE), Bayesian Optimization, and High-Throughput Experimentation. Covering foundational principles, practical applications, troubleshooting techniques, and validation protocols, the content addresses key challenges in developing novel materials and active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). Special emphasis is placed on multi-objective optimization balancing yield, selectivity, cost, and environmental impact, with real-world case studies demonstrating successful implementation in pharmaceutical process development.

From Trial-and-Error to AI: Fundamental Concepts in Reaction Parameter Optimization

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

OFAT (One-Factor-at-a-Time) Troubleshooting Guide

Problem 1: Inefficient Optimization Process

- Symptoms: The optimization process is taking an excessively long time; discovered optimal conditions fail when the process is scaled up.

- Possible Cause: OFAT fails to account for interaction effects between factors [1]. An optimum found by varying one factor may become sub-optimal when another factor is changed later.

- Solution: Transition to a Design of Experiments (DoE) approach to efficiently capture factor interactions.

Problem 2: Inconsistent or Non-Reproducible Results

- Symptoms: Results from different experimental batches show high variability, making it difficult to pinpoint a reliable optimum.

- Possible Cause: OFAT is highly sensitive to noise and uncontrolled variables, as it does not systematically account for variability across all experimental runs [1].

- Solution: Implement DoE, which uses randomization and replication to better estimate and account for experimental error.

DoE (Design of Experiments) Troubleshooting Guide

Problem 1: Curse of Dimensionality in High-Throughput Experimentation

- Symptoms: Facing a combinatorial explosion of experiments when trying to optimize a process with a large number of parameters (e.g., culture media with many components) [1].

- Possible Cause: Traditional DoE, while more efficient than OFAT, can still generate a large number of experimental runs when factors are numerous.

- Solution: Use machine learning (ML) models to navigate the complex, high-dimensional parameter space more efficiently. ML can identify the most influential factors from large datasets, allowing for a more focused DoE [2] [1].

Problem 2: Modeling Complex, Non-Linear Relationships

- Symptoms: A DoE model with linear and interaction terms does not adequately describe the system's behavior, leading to poor predictive performance.

- Possible Cause: The relationship between process parameters and the output is highly non-linear [1].

- Solution: Employ ML algorithms (e.g., neural networks, Gaussian process regression) that are capable of learning and predicting these complex, non-linear relationships without requiring a pre-specified model structure [2] [3].

Machine Learning Troubleshooting Guide

Problem 1: Poor Model Performance on a New Reaction or Process

- Symptoms: An ML model pre-trained on a large, general reaction database performs poorly when predicting outcomes for your specific, novel material system [3].

- Possible Cause: The "source domain" (general database) and your "target domain" (novel material) are too distinct. The model lacks relevant, high-quality data for your specific problem [3].

- Solution: Apply Transfer Learning. Fine-tune a pre-trained model on a smaller, focused dataset relevant to your specific reaction family or material class. This leverages general knowledge while adapting to your specific problem [3].

Problem 2: Limited or No Initial Data for a New Research Problem

- Symptoms: You cannot build a predictive ML model because you have no or very few initial data points for your novel research area.

- Possible Cause: Supervised ML models require data for training.

- Solution: Implement an Active Learning strategy. Start with an initial set of experiments (either randomly or based on expert knowledge). The ML model then iteratively suggests the next most informative experiments to perform, maximizing knowledge gain and finding optimal conditions with fewer total experiments [3].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When should I definitely avoid using OFAT and switch to DoE or ML?

- A: Avoid OFAT when you suspect strong interactions between factors (common in complex chemical or biological processes), when you need to model the response surface comprehensively, or when experimental resources (time, materials) are limited and you need maximum efficiency [1].

Q2: My DoE results seem good in the lab but fail in the bioreactor. Why?

- A: This can occur if the DoE was conducted in a static environment that doesn't capture the dynamic, non-linear interactions present in a scaled-up bioreactor system. ML models, trained on high-throughput or historical bioreactor data, are often better at capturing these complex relationships and predicting performance under scale-up conditions [1].

Q3: What is the biggest hurdle to implementing ML in my lab?

- A: The primary challenge is often data quality and availability. ML models require large, consistent, and well-annotated datasets to be effective. Challenges related to data scalability, model interpretability, and regulatory compliance for therapeutic development also need to be considered [1].

Q4: Can I use ML with a traditional DoE?

- A: Yes, they are complementary. A well-designed DoE can provide an excellent initial dataset for building a powerful ML model. The ML model can then be used with active learning to explore the design space beyond the initial DoE runs, refining the optimization further [2] [3].

Comparison of Optimization Methods

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of OFAT, DoE, and Machine Learning to aid in method selection.

Table 1: Comparison of OFAT, DoE, and Machine Learning for Parameter Optimization

| Feature | OFAT (One-Factor-at-a-Time) | DoE (Design of Experiments) | Machine Learning (ML) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Vary one parameter while holding all others constant [1]. | Systematically vary all parameters simultaneously according to a statistical design [1]. | Learn complex relationships between parameters and outcomes from data using algorithms [2] [1]. |

| Handling Interactions | Fails to capture interaction effects between factors [1]. | Explicitly designed to identify and quantify interaction effects. | Excels at modeling complex, non-linear, and higher-order interactions [1]. |

| Experimental Efficiency | Low; can require many runs for few factors and miss the true optimum. | High; structured to extract maximum information from a minimal number of runs. | Can be very high; active learning guides the most informative experiments, reducing total runs [3]. |

| Data Requirements | Low per experiment, but overall approach is inefficient. | Requires a predefined set of experiments. | Requires a substantial amount of high-quality data for training, but can be sourced from historical data or HTE [1] [3]. |

| Best Suited For | Simple systems with no factor interactions; very preliminary screening. | Modeling well-defined experimental spaces and building quantitative response models. | Highly complex, non-linear systems; high-dimensional spaces; leveraging large historical datasets [2] [1]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: ML-Guided Bioprocess Optimization

This protocol outlines a methodology for using Machine Learning to optimize culture conditions to minimize charge heterogeneity in monoclonal antibody (mAb) production, a critical quality attribute [1].

1. Define Objective and Acquire Data

- Objective: Minimize the percentage of acidic and basic charge variants in the final mAb product.

- Data Collection: Compile a historical dataset from past experiments. Each entry should include:

- Inputs (Features): Process parameters (pH, temperature, culture duration, dissolved oxygen) and medium components (glucose, metal ions, amino acids) [1].

- Outputs (Labels): Analytical results for charge variant distribution (% main species, % acidic species, % basic species) obtained via methods like Cation Exchange Chromatography (CEX) or capillary isoelectric focusing (cIEF) [1].

2. Data Preprocessing and Model Selection

- Clean Data: Handle missing values, normalize numerical features, and remove outliers.

- Select Model: For regression tasks with complex, non-linear relationships, algorithms like Gaussian Process Regression or Random Forests are often suitable starting points [1].

3. Model Training and Validation

- Split the dataset into training and testing sets (e.g., 80/20).

- Train the ML model on the training set.

- Validate the model's predictive accuracy on the held-out testing set. Use metrics like R-squared (R²) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE).

4. Iterative Optimization via Active Learning

- The trained model predicts charge variant outcomes for a vast number of potential parameter combinations.

- An acquisition function (e.g., targeting lowest predicted impurity) selects the most promising conditions for the next round of experimentation [3].

- Conduct new experiments with these suggested conditions.

- Add the new experimental results to the training dataset and retrain the model.

- Repeat this cycle until the desired product quality (e.g., maximum % main species) is achieved.

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

The following table details key components used in the development and optimization of bioprocesses for monoclonal antibody production, as discussed in the context of controlling charge variants [1].

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for mAb Bioprocess Optimization

| Item | Function / Relevance in Optimization |

|---|---|

| CHO Cell Line | The most common host cell system for the industrial production of monoclonal antibodies. Its specific genotype and phenotype significantly influence product quality attributes [1]. |

| Chemically Defined Culture Medium | A precisely formulated basal and feed medium. The concentrations of components like glucose, amino acids, and metal ions are critical factors that can be optimized to control post-translational modifications and charge heterogeneity [1]. |

| Metal Ion Supplements (e.g., Zn²⁺, Cu²⁺) | Specific metal ions can act as cofactors for enzymes (e.g., carboxypeptidase) that process the antibody, directly impacting the formation of basic variants by influencing C-terminal lysine cleavage [1]. |

| pH Buffers | Maintaining a stable and optimal pH is critical. pH directly influences the rate of deamidation (a major contributor to acidic variants) and other degradation pathways [1]. |

| Analytical Standards for cIEF/CEX | Certified standards used to calibrate capillary isoelectric focusing (cIEF) or Cation Exchange Chromatography (CEX) instruments. Essential for accurately quantifying the distribution of charge variants (acidic, main, basic species) [1]. |

FAQs: Understanding Variable Types in Experiment Design

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between a continuous and a categorical variable in material synthesis?

In material synthesis, variables are classified based on the nature of the data they represent:

- Continuous Variables: These are measured on a scale with a meaningful numerical value and interval. Examples include

temperature,pressure,flow rate,reaction time, andconcentration[4] [5]. You can perform mathematical operations on them, and they can take on a wide range of values. - Categorical Variables: These represent discrete, qualitative groups or classifications. Examples include

catalyst type,precursor vendor,solvent class,synthesis route order, andmaterial identity[5] [6] [7]. Assigning numbers to them (e.g., Vendor A=1, Vendor B=2) does not make them quantitative, as the numbers lack sequence or scale meaning [5].

Q2: When does it make sense to treat a categorical variable as continuous?

Treating a categorical variable as continuous is rarely advised, but can be considered in specific, justified situations [8]:

- Ordinal with Meaningful Intervals: When the categories have a natural order (ordinal) and the intervals between them are reasonably assumed to be equal. For example, if using a well-tested scale with meaningful cut points for "low," "medium," and "high" purity that are equidistant on the underlying measurement scale [8] [9].

- Binary Variables: A two-level category (e.g., catalyst present/absent) is commonly coded as 0 and 1 and used in regression models, which is a form of treating it as a continuous predictor [8].

- Probabilistic Models: In advanced methods like Item Response Theory, a latent continuous scale is assumed behind ordered categories, and category locations are estimated on that continuum [8].

Troubleshooting Tip: Incorrectly treating a categorical variable as continuous often leads to models that poorly represent the real-world process. If a categorical variable has no inherent order (e.g.,

vendor name), it must never be treated as continuous.

Q3: What are the primary risks of categorizing a continuous variable (e.g., using a median split)?

Categorizing a continuous variable, while sometimes necessary, leads to significant information loss and can compromise your analysis [9]:

- Loss of Information and Power: All variation within a category (e.g., all "high" temperatures) is ignored, making it harder to detect genuine effects [8] [9].

- Arbitrary Groupings: The choice of cut-point (e.g., median) is often arbitrary and can vary from sample to sample, making results less stable and reproducible [9].

- Masked Non-Linear Relationships: It fails to capture the true, potentially gradual, relationship between the variable and the outcome [9].

Q4: How do I handle experiments with a mix of both variable types?

Many modern modeling and optimization approaches are designed for mixed-variable problems.

- Regression with Dummy Variables: In statistical models like DOE and multiple regression, categorical variables are handled using dummy variable coding, creating (N-1) new binary variables for an N-level category [5] [10].

- Specialized AI/ML Models: Advanced frameworks, such as

NanoCheffor nanoparticle synthesis, use techniques like positional encoding and embeddings to represent categorical choices (e.g., reagent sequence) for joint optimization with continuous parameters (e.g., temperature, time) [7]. - Bayesian Optimization with Bandits: For material design, optimization processes can combine a multi-armed bandit strategy (for categorical choices) with continuous Bayesian optimization [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Model Performance with Categorical Inputs

Symptoms: Your regression or machine learning model has low predictive accuracy (R²), high error, or fails to identify significant factors when categorical variables are included.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect Coding | Check how the variable is encoded in your software. Are the categories represented as numbers (1,2,3) or as text/factors? | Recode the categorical variable using dummy variable encoding (also called indicator coding). Most statistical software (like R, Quantum XL) does this automatically behind the scenes [5] [10]. |

| Insufficient Data | Check the number of experimental runs for each level of your categorical factor. | Ensure a balanced design with an adequate number of replicates for each categorical level to reliably estimate its effect. |

| Complex Interactions | Check for significant interaction effects between your categorical variable and key continuous variables. | Include interaction terms in your model (e.g., Vendor*Temperature). This can reveal if the effect of temperature depends on the vendor [5]. |

Issue: Difficulty Optimizing Processes with Both Continuous and Categorical Parameters

Symptom: Traditional optimization methods (e.g., response surface methodology) are ineffective or cannot be applied when your synthesis process involves choosing the best material type (categorical) and the best temperature (continuous).

Solution: Implement a mixed-variable optimization strategy.

- Define the Problem: Clearly list all continuous (e.g., temperature, flow rate) and categorical (e.g., catalyst type, solvent) parameters [6] [7].

- Select a Suitable Model: Use a surrogate model capable of handling mixed variables, such as a Random Forest or a Gaussian Process model with specialized kernels for categorical inputs [6].

- Apply a Mixed-Variable Optimizer: Utilize an optimization algorithm designed for this purpose, such as a combination of:

- A multi-armed bandit to efficiently explore and exploit the best categorical choices.

- Bayesian optimization to fine-tune the continuous parameters for the selected category [6].

- Iterate in an Autonomous Loop: In advanced setups, this process can be automated. An AI-directed platform (like

AutoBotorNanoChef) suggests new experiments, a robotic system executes them, and the model is updated until the optimal combination is found [11] [7].

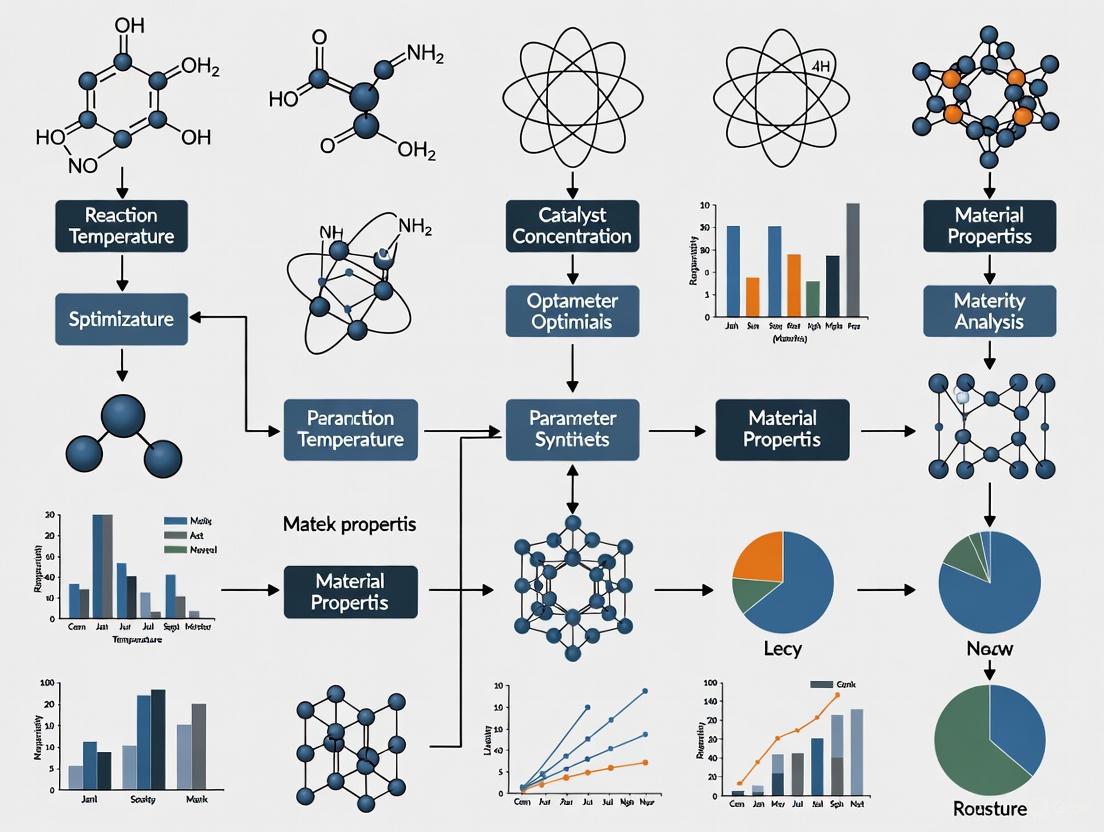

The workflow for such an automated, closed-loop optimization system can be visualized as follows:

Data Presentation: Variable Classification and Handling

The table below summarizes the core characteristics and modeling approaches for continuous and categorical variables in material synthesis.

Table 1: Summary of Variable Types in Material Synthesis Experiments

| Feature | Continuous Variable | Categorical Variable |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Measured quantity with numerical meaning and interval [5] [12]. | Qualitative group or classification without numerical scale [5] [12]. |

| Examples | Temperature (°C), pressure (bar), concentration (M), time (min) [4] [5]. | Catalyst type (A, B, C), solvent (water, acetone), vendor (X, Y, Z) [5] [6]. |

| Statistical Handling | Used directly in regression; coefficient represents slope/change [5]. | Coded into N-1 dummy variables for regression; coefficients represent difference from a reference level [5] [10]. |

| Optimization Approach | Response surface methodology (RSM), Bayesian optimization [4]. | Multi-armed bandit, decision trees; often requires specialized mixed-variable optimizers [6] [7]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Designing an Experiment with Mixed Variables Using Dummy Variables

This methodology allows you to include categorical factors in a regression model to analyze their impact on a continuous outcome (e.g., yield, particle size).

Methodology:

- Identify Variables: Define your continuous and categorical Independent Variables (IVs) and your Dependent Variable (DV).

- Example: IVs:

Vendor(categorical: ACME, SZ, BP),Temperature(continuous: 50-100°C). DV:Purity(continuous).

- Example: IVs:

- Choose a Reference Level: Select one level of your categorical variable as the baseline for comparison (e.g.,

ACME) [5]. - Create Dummy Variables: For the remaining levels, create new binary columns in your data matrix.

- For a run with

Vendor = SZ, theSZ_dummycolumn is 1, and theBP_dummycolumn is 0. - For a run with

Vendor = BP, theSZ_dummycolumn is 0, and theBP_dummycolumn is 1. - For the reference level (

ACME), bothSZ_dummyandBP_dummyare set to 0 [5].

- For a run with

- Run Regression: Perform multiple linear regression using the continuous variable and the new dummy variables as predictors.

- Interpret Results:

- The coefficient for

SZ_dummyis your confidence that the performance of SZ is different from ACME. - The coefficient for

Temperaturerepresents the expected change in purity per unit increase in temperature, assuming the vendor is held constant [5].

- The coefficient for

Protocol 2: Autonomous Optimization of Mixed Variables for Nanoparticle Synthesis

This protocol is based on the NanoChef AI framework, which simultaneously optimizes synthesis sequences (categorical) and reaction conditions (continuous) [7].

Methodology:

- Parameter Definition:

- Categorical: Synthesis sequence order of reagents (e.g., A-then-B, B-then-A).

- Continuous: Reaction conditions like reaction time, temperature, and concentration [7].

- Representation:

- Use AI techniques like positional encoding and MatBERT embeddings to convert the categorical sequence into a numerical vector that a deep learning model can process [7].

- Modeling & Loop:

- A deep learning model (e.g., a neural network) is trained to predict the material property outcome (e.g., UV-Vis absorption peak, monodispersity) from the mixed-variable input.

- A Bayesian optimizer suggests the next most informative experiment (combination of sequence and conditions) to evaluate, aiming to find the global optimum efficiently.

- In a closed-loop autonomous laboratory, this suggestion is passed to a robotic system for execution [11] [7].

- Validation:

- The process continues until a performance plateau is reached or a target is met. The optimal recipe is then validated experimentally. In the

NanoChefstudy, this approach led to a 32% reduction in the full width at half maximum (FWHM) for Ag nanoparticles, indicating higher monodispersity [7].

- The process continues until a performance plateau is reached or a target is met. The optimal recipe is then validated experimentally. In the

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key material categories and their functions in experiments involving mixed-variable optimization, as featured in the cited research.

Table 2: Essential Materials and Their Functions in Synthesis Optimization

| Category / Item | Example in Research | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Solutions | Metal halide perovskite precursors [11]. | The starting chemical solutions used to synthesize the target material. Their composition and mixing order are critical categorical and continuous parameters. |

| Crystallization Agents | Anti-solvents used in perovskite thin-film synthesis [11]. | A chemical agent added to induce and control the crystallization process from the precursor solution. Timing of addition is a key continuous parameter. |

| Catalysts / Reagents | Reagents for Ag nanoparticle synthesis [7]. | Substances that participate in the reaction to determine the final product's properties. Their identity is categorical; their concentration is continuous. |

| Process Analytical Technology (PAT) | Inline UV-Vis, FT-IR, NMR spectrometers; photoluminescence imaging [4] [11]. | Tools for real-time, inline measurement of process parameters and product quality attributes (e.g., concentration, film homogeneity). Essential for data-driven feedback. |

► Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the core green metrics I should track for a sustainable catalytic process? The main green metrics for evaluating the sustainability of catalytic processes include Atom Economy (AE), Reaction Yield (ɛ), Stoichiometric Factor (SF), Material Recovery Parameter (MRP), and Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME). These metrics help in assessing the environmental and economic efficiency of a process. For instance, a high Atom Economy (close to 1.0) indicates that most of the reactant atoms are incorporated into the desired product, minimizing waste. These metrics can be graphically evaluated using tools like radial pentagon diagrams for a quick visual assessment of the process's greenness [13].

Q2: How can I handle multiple, conflicting optimization objectives, like maximizing yield while minimizing cost? Optimizing multiple conflicting objectives is a common challenge. The solution is not to combine them into a single goal but to use Multi-Objective Optimization (MOO) methods. Machine learning techniques, particularly Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization (MOBO), are designed for this purpose. They aim to find a set of optimal solutions, known as the Pareto front, where no objective can be improved without worsening another. This allows researchers to see the trade-offs and select the best compromise solution for their specific needs [14] [15] [16].

Q3: My reaction optimization is slow and resource-intensive. Are there more efficient approaches? Yes, traditional one-factor-at-a-time approaches are often inefficient. Autonomous Experimentation (AE) systems and High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) integrated with machine learning can dramatically accelerate this process. These closed-loop systems use AI to design, execute, and analyze experiments autonomously, rapidly identifying optimal conditions with minimal human intervention and resource consumption [14] [15].

Q4: What is a practical way to quantitatively decide the best solution from multiple optimal candidates? When faced with a set of Pareto-optimal solutions, you can use decision-making techniques to select a single best compromise. One method is the probabilistic methodology for multi-objective optimization (PMOO), which calculates a total preferable probability for each candidate alternative. This is done by treating each objective as an independent event and calculating the joint probability of all objectives being met simultaneously. The alternative with the highest total preferable probability is the most balanced and optimal choice [17].

► Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inability to Find a Balanced Condition for Multiple Objectives

- Symptoms: Optimizing one objective (e.g., yield) leads to unacceptable performance in another (e.g., selectivity or cost).

- Solution:

- Verify your objectives: Ensure all critical objectives (e.g., yield, selectivity, purity, cost) are clearly defined.

- Implement a MOO algorithm: Use an optimization planner like Expected Hypervolume Improvement (EHVI) that is specifically designed for multiple objectives. This will help you map the Pareto front instead of converging to a single point [14].

- Post-process results: Analyze the Pareto-optimal set using a decision-making method like BHARAT or the probabilistic methodology (PMOO) to select the final operating conditions based on your project's priorities [17] [16].

Problem: Low Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME) and High Waste

- Symptoms: The mass of the final product is low compared to the mass of all reactants used.

- Solution:

- Analyze Green Metrics: Calculate your process's Atom Economy, Reaction Yield, and Stoichiometric Factor to identify the primary source of inefficiency [13].

- Improve Material Recovery: Investigate and implement methods for solvent recycling and catalyst recovery. Studies show that process sustainability improves significantly with better material recovery, as captured by the Material Recovery Parameter (MRP) [13].

- Catalyst Selection: Consider switching to a more selective or efficient catalytic system. For example, in the synthesis of dihydrocarvone, using a dendritic zeolite catalyst resulted in excellent green characteristics (AE = 1.0, RME = 0.63) [13].

Problem: Optimization Process Fails to Converge or is Unstable

- Symptoms: The optimization algorithm suggests erratic parameter changes or fails to show consistent improvement over iterations.

- Solution:

- Check for discontinuities: In computational optimization, ensure that the energy or property calculations are smooth. For forcefield methods like ReaxFF, discontinuities can be reduced by adjusting the

BondOrderCutoffor using tapered bond orders [18]. - Adjust the algorithm's balance: Tune the balance between exploration (testing new regions of the parameter space) and exploitation (refining known good regions) in your Bayesian Optimization algorithm [15].

- Start with diverse initial samples: Begin the optimization campaign with a well-spread set of initial experiments, such as those generated by Sobol sampling, to ensure the algorithm has a good baseline understanding of the reaction landscape [14] [15].

- Check for discontinuities: In computational optimization, ensure that the energy or property calculations are smooth. For forcefield methods like ReaxFF, discontinuities can be reduced by adjusting the

► Key Green Metrics for Process Sustainability

The following table summarizes the core metrics used to quantitatively assess the greenness and efficiency of chemical processes [13].

| Metric | Formula / Definition | Interpretation | Ideal Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atom Economy (AE) | (MW of Desired Product / Σ MW of Reactants) x 100% | Measures the fraction of reactant atoms incorporated into the final product. | Close to 100% |

| Reaction Yield (ɛ) | (Actual Moles of Product / Theoretical Moles of Product) x 100% | Measures the efficiency of the reaction in converting reactants to the desired product. | Close to 100% |

| Stoichiometric Factor (SF) | Σ (Stoichiometric Coeff. of Reactants) | Relates to the excess of reactants used. A lower, optimized value is better. | Minimized |

| Material Recovery Parameter (MRP) | A measure of the fraction of materials (solvents, catalysts) recovered and recycled. | Indicates the effectiveness of material recovery efforts. | 1.0 (Full recovery) |

| Reaction Mass Efficiency (RME) | (Mass of Product / Σ Mass of All Reactants) x 100% | A holistic measure of the mass efficiency of the entire process. | Close to 100% |

► Experimental Protocol: Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization for Reaction Optimization

This protocol outlines the application of a closed-loop autonomous system for optimizing chemical reactions, as demonstrated in recent studies [14] [15].

1. Initialization Phase

- Define Objectives: Clearly state all objectives to be optimized (e.g., maximize yield, maximize selectivity, minimize cost).

- Define Search Space: Identify all controllable reaction parameters (e.g., catalyst, ligand, solvent, temperature, concentration) and their plausible ranges.

- Set Constraints: Specify any practical constraints, such as excluding solvent combinations with boiling points lower than the reaction temperature or unsafe reagent pairs.

2. Autonomous Experimentation Workflow The following diagram illustrates the closed-loop optimization cycle.

Step 1: Plan

- The AI planner (e.g., a Multi-Objective Bayesian Optimization algorithm like q-NEHVI or TS-HVI) uses the current knowledge base to design the next batch of experiments.

- The algorithm balances exploring unknown areas of the parameter space and exploiting known promising regions.

Step 2: Experiment

- The research robot or automated platform (e.g., a high-throughput screening robot or a modified 3D printer with a syringe extruder) executes the specified experiments.

- Onboard machine vision systems can be used to capture results in real-time [14].

Step 3: Analyze

- The system automatically characterizes the reaction outcomes (e.g., yield, selectivity) from the experimental data.

- The results, paired with their input parameters, are used to update the machine learning model's knowledge base.

Iteration: The cycle repeats until a termination criterion is met, such as convergence, a set number of iterations, or exhaustion of the experimental budget.

► The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

This table lists essential materials and their functions in advanced optimization and materials research, as featured in the cited studies.

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| K–Sn–H–Y-30-dealuminated zeolite | A catalyst used in the epoxidation of R-(+)-limonene, demonstrating the application of green metrics in fine chemical production [13]. |

| Dendritic Zeolite d-ZSM-5/4d | A catalytic material used in the synthesis of dihydrocarvone, noted for its excellent green characteristics (AE=1.0, RME=0.63) [13]. |

| Non-Precious Metal Catalysts (e.g., Ni-based) | Lower-cost, earth-abundant alternatives to precious metal catalysts (e.g., Pd) for cross-coupling reactions, aligning with economic and environmental objectives [15]. |

| Custom Syringe Extruder | A key component of autonomous research systems (e.g., AM-ARES) for additive manufacturing and materials testing, enabling the exploration of novel material feedstocks [14]. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) Regressor | A core machine learning model used in Bayesian optimization to predict reaction outcomes and their uncertainties based on experimental data [15]. |

| Pulsed Nd:YAG Laser System | Used in laser welding process optimization, where parameters like peak power and pulse duration are tuned for quality and energy efficiency [17]. |

Troubleshooting Poor Aqueous Solubility

FAQ: What formulation strategies can overcome poor solubility and dissolution-limited bioavailability?

For poorly water-soluble drug candidates, the dissolution rate and apparent solubility in the gastrointestinal tract are major barriers to adequate absorption and bioavailability. Amorphous solid dispersions (ASDs) are a leading formulation strategy to address this. ASDs work by creating and stabilizing a drug substance in a higher-energy amorphous form within a polymer matrix, which can lead to rapid dissolution and the formation of a supersaturated solution, thereby enhancing the driving force for absorption [19].

Key Considerations:

- Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation (LLPS): Upon dissolution, a supersaturated state can lead to the formation of drug-rich nanodroplets (LLPS). These can act as reservoirs to maintain supersaturation but may also precede crystallization [19].

- Congruent Release: The polymer and API must be released together from the ASD. High drug loading or rapidly crystallizing drugs risk rapid precipitation, negating the solubility advantage. The use of surfactants can promote congruent release [19].

- Polymer Selection: The polymer in the ASD is critical for preventing the amorphous API from undergoing phase separation and crystallization, both in the solid state and upon dissolution [19].

Experimental Protocol: Solubility Measurement and Dissolution Method Development for ASDs

Objective: To characterize the solubility and develop a discriminatory dissolution method for an immediate-release solid oral dosage form containing an amorphous solid dispersion.

Materials:

- API (crystalline and amorphous forms)

- Polymer(s) for dispersion (e.g., PVP, HPMC)

- Dissolution apparatus (USP I, II, or IV)

- Buffers and surfactants (e.g., SLS) for media

- HPLC system with UV detection or in-situ fiber optics

Methodology [19]:

- Equilibrium Solubility Measurement: Use the shake-flask method at 37°C. Prepare saturated solutions of the crystalline API in various physiologically relevant media (e.g., pH 1.2, 4.5, 6.8) and agregate for a sufficient time (e.g., 24-72 hours) to reach equilibrium. Filter and quantify the dissolved API concentration.

- Amorphous Solubility Determination: Determine the concentration at which liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) occurs, observed as a sudden increase in solution turbidity. This defines the amorphous solubility limit.

- Dissolution Media Selection: For Quality Control (QC), the medium should have a pH and composition that provides sink conditions (typically a volume 3-10 times that required to form a saturated solution). For ASD formulations that achieve supersaturation, a non-sink condition may be necessary for the method to be discriminatory.

- Dissolution Testing: Perform dissolution testing on the ASD formulation. Common parameters include: paddle apparatus (USP II), 50-75 rpm, 37°C, in 500-900 mL of medium. Sample at appropriate timepoints (e.g., 10, 20, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120 minutes) and analyze for drug concentration.

- Data Analysis: Plot the dissolution profile (\% dissolved vs. time). The method should be able to detect changes in performance, such as those caused by crystallization of the API within the formulation.

Workflow: Solubility and Dissolution Challenge Pathway

Quantitative Data: Solubility and Sink Conditions

Table 1: Key Solubility and Dissolution Parameters for Formulation Development [19]

| Parameter | Description | Typical Target / Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamic Solubility | Equilibrium concentration of the crystalline API in a solvent. | Baseline for defining sink conditions. |

| Amorphous Solubility | Maximum concentration achieved by the amorphous form before LLPS. | Defines the upper limit for supersaturation. |

| Sink Condition | Volume of medium sufficient to dissolve the dose. | USP recommends >3x saturated solubility volume. |

| Supersaturation | Concentration exceeding thermodynamic solubility. | Aims to increase absorption flux. |

Managing Chemical Instability and Reaction Optimization

FAQ: How can I efficiently optimize complex, multi-variable reactions to improve yield and stability?

Traditional One-Variable-at-a-Time (OVAT) optimization is inefficient for complex reactions with many interacting parameters. Machine Learning (ML)-driven Bayesian Optimization (BO) combined with High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) is a powerful strategy for navigating high-dimensional reaction spaces efficiently. This approach uses algorithmic guidance to balance the exploration of new reaction conditions with the exploitation of known promising areas, identifying optimal conditions with fewer experiments [15] [20].

Key Considerations:

- Multi-objective Optimization: Real-world processes require balancing multiple goals simultaneously, such as maximizing yield and selectivity while minimizing cost and impurities [15].

- Handling Categorical Variables: The choice of catalyst, ligand, and solvent (categorical variables) often has a dramatic effect on outcomes. The optimization algorithm must effectively handle these discrete choices [15].

- Human-in-the-Loop: Chemists' domain knowledge remains crucial for defining the plausible reaction space, interpreting results, and guiding the overall campaign strategy [20].

Experimental Protocol: Bayesian Optimization Campaign for Reaction Parameters

Objective: To identify optimal reaction conditions for a chemical transformation by maximizing yield and selectivity through an automated ML-driven workflow.

Materials:

- Automated HTE platform (e.g., 96-well plate reactor)

- Stock solutions of reactants, catalysts, ligands, and bases

- A library of solvents and additives

- Analytical equipment for rapid analysis (e.g., UPLC-MS, GC-MS)

- Define Reaction Space: Specify all variables to be optimized (e.g., catalyst/ligand identity and loading, solvent, concentration, temperature, equivalents of reagents) as continuous or categorical parameters. Apply constraints to filter impractical conditions (e.g., temperature above solvent boiling point).

- Initial Sampling: Use a space-filling design like Sobol sampling to select an initial batch of experiments (e.g., one 96-well plate) that diversely explores the defined reaction space.

- Execution and Analysis: Run the batch of experiments automatically or manually and analyze the outcomes (e.g., yield, selectivity).

- Machine Learning Loop:

- Model Training: Train a machine learning model (e.g., Gaussian Process regressor) on all collected data to predict outcomes and their uncertainty for all possible condition combinations.

- Next-Batch Selection: An acquisition function (e.g., q-NParEgo, q-NEHVI) uses the model's predictions to select the next batch of experiments that best balances exploration and exploitation.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 3 and 4 for several iterations until performance converges or the experimental budget is exhausted.

Workflow: Bayesian Optimization for Reaction Screening

Research Reagent Solutions for Reaction Optimization

Table 2: Key Components of an ML-Driven Optimization Toolkit [15]

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Optimization |

|---|---|

| Bayesian Optimization Algorithm | Core ML strategy for guiding experimental design by modeling the reaction landscape. |

| Acquisition Function (e.g., q-NParEgo) | Balances exploration of new conditions vs. exploitation of known high-performers. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) Platform | Enables highly parallel execution of reactions (e.g., in 96-well plates) for rapid data generation. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) Regressor | A probabilistic model that predicts reaction outcomes and quantifies uncertainty for new conditions. |

Controlling Impurity Profiles and Mitigating Risk

FAQ: What are the critical controls for genotoxic nitrosamine impurities (NAs) in drug substances?

N-Nitrosamine impurities are potent genotoxicants that can form during API synthesis or drug product storage. Regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA have established stringent guidelines requiring proactive risk assessment and control. These impurities form in acidic environments from reactions between nitrosating agents (e.g., nitrites) and secondary or tertiary amines, amides, or other nitrogen-containing groups [21].

Key Considerations:

- N-Nitrosamine Drug Substance-Related Impurities (NDSRIs): Recent regulatory updates specifically address NDSRIs, which are nitrosamines formed from the API itself, posing new analytical and control challenges [21].

- Widespread Risk Factors: Common reagents and solvents like dimethylformamide (DMF), N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP), and triethylamine (TEA) can be precursors to nitrosamine formation, even after purification [21].

- Excipient Compatibility: "Inactive" excipients can be a source of risk. For example, lactose can participate in Maillard reactions with primary amine APIs, and certain polymers may contain peroxide impurities that drive API oxidation [22].

Experimental Protocol: Risk Assessment and Analytical Control for N-Nitrosamines

Objective: To identify, quantify, and control N-nitrosamine impurities in a drug substance per latest regulatory guidelines.

Materials:

- API and synthetic intermediates

- Reference standards for suspected N-nitrosamines

- LC-MS/MS or GC-MS system

- Solvents (HPLC/MS grade)

Methodology [21]:

- Risk Assessment: Conduct a thorough analysis of the API synthesis pathway. Identify all steps where secondary or tertiary amines, amides, carbamates, or ureas are exposed to nitrosating agents (e.g., nitrites, nitrogen oxides, azide reagents) or where nitrosamine formation is chemically plausible.

- Analytical Method Development:

- Technique Selection: Use highly sensitive and selective techniques like Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) or Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS).

- Sample Preparation: Develop extraction and concentration techniques suitable for the API matrix.

- Validation: Validate the method for specificity, accuracy, precision, and sensitivity (LOQ should be below the established Acceptable Intake (AI)).

- Testing and Monitoring: Test the API and critical intermediates for the identified nitrosamine impurities. Implement controls in the manufacturing process to mitigate the risk, such as using alternative reagents, adding scavengers, or modifying process parameters.

- Documentation: Document the risk assessment, testing results, and control strategies in regulatory submissions.

Workflow: Nitrosamine Impurity Risk Management

Quantitative Data: Regulatory Limits for Common N-Nitrosamines

Table 3: Overview of Common N-Nitrosamine Impurities and Regulatory Guidance [21]

| N-Nitrosamine Impurity | Associated Drug Classes / Reagents | Carcinogenic Potency Category | Interim Acceptable Intake (AI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| N-Nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) | Sartans (Valsartan), Ranitidine | High | As per latest regulatory revision (e.g., 96 ng/day) |

| N-Nitrosodiethylamine (NDEA) | Sartans | High | As per latest regulatory revision (e.g., 26.5 ng/day) |

| NDSRIs | APIs with secondary/tertiary amine structures | Compound-specific | Set based on carcinogenic potential; interim limits established for many. |

| N-Nitroso-ethyl-isopropyl-amine | Sartans | Medium | As per latest regulatory revision (e.g., 320 ng/day) |

FAQs: Fundamental Concepts in Reaction Optimization

What is a "chemical search space" in reaction optimization? The chemical search space encompasses all possible combinations of reaction parameters (or factors)—such as reagents, solvents, catalysts, temperatures, and concentrations—that are deemed plausible for a given chemical transformation. In systematic exploration, this space is treated as a discrete combinatorial set of potential conditions. Guided by practical process requirements and domain knowledge, this approach allows for the automatic filtering of impractical conditions, such as reaction temperatures exceeding solvent boiling points or unsafe reagent combinations [15].

Why is traditional One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) optimization often insufficient? OFAT approaches explore only a limited subset of fixed combinations within a vast reaction space. As additional reaction parameters multiplicatively expand the number of possible experimental configurations, exhaustive screening becomes intractable even with advanced technology. Consequently, traditional methods may overlook important regions of the chemical landscape containing unexpected reactivity or superior performance [15].

How does High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) transform optimization? HTE platforms utilize miniaturized reaction scales and automated robotic tools to enable highly parallel execution of numerous reactions. This makes the exploration of many condition combinations more cost- and time-efficient than traditional techniques. However, the effectiveness of HTE relies on efficient search strategies to navigate large parameter spaces without resorting to intractable exhaustive screening [15].

What is a Response Surface, and why is it important? A response surface is a visualization or mathematical model that shows how a system's response (e.g., reaction yield or selectivity) changes as the levels of one or more factors are increased or decreased. It is a crucial concept for understanding optimization. For a one-factor system, it can be a simple 2D plot; for two factors, it can be represented as a 3D surface or a 2D contour plot, helping researchers identify optimal regions within the search space [23].

Troubleshooting Guides: Common Optimization Challenges

Challenge: Poor Reaction Yield or Selectivity

Symptoms:

- Consistently low yield across multiple experimental batches.

- Failure to identify any promising reaction conditions after initial screening.

- Inability to meet target thresholds for yield or selectivity.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Verify Chemical Space Definition: Ensure the defined search space includes a diverse and chemically sensible range of parameters (e.g., ligands, solvents, additives) known to influence the reaction outcome [15].

- Assess Initial Sampling: Evaluate if the initial set of experiments (e.g., selected via quasi-random Sobol sampling) provides adequate coverage of the reaction condition space. Poor initial diversity can hinder subsequent optimization [15].

- Check for Unexplored Regions: Use your optimization algorithm's output (e.g., uncertainty predictions from a Bayesian model) to identify regions of the search space that have not been explored but are predicted to be promising [15].

Resolution Strategies:

- Implement Bayesian Optimization (BO): Use a BO workflow with an acquisition function like q-NEHVI (q-Noisy Expected Hypervolume Improvement) that balances the exploration of unknown regions with the exploitation of known high-performing conditions. This is particularly effective for multi-objective optimization (e.g., simultaneously maximizing yield and selectivity) [15] [24].

- Adopt Adaptive Constraints: Integrate strategies like Adaptive Boundary Constraint BO (ABC-BO) to prevent the algorithm from suggesting "futile" experiments—conditions that, even assuming a 100% yield, could not improve upon the best-known objective value. This maximizes the value of each experimental cycle [25].

- Leverage Swarm Intelligence: Consider nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithms like

α-PSO(Particle Swarm Optimization). This method treats reaction conditions as particles that navigate the search space using simple, intuitive rules based on personal best findings and the swarm's collective knowledge, often offering interpretable and effective optimization [24].

Challenge: Algorithm Suggests Impractical or Unsafe Conditions

Symptoms:

- The optimization algorithm recommends conditions with incompatible reagents.

- Suggested temperatures or pressures exceed the safe operating limits of laboratory equipment.

- Proposed solvent-catalyst combinations are known to be ineffective or degrading.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Review Constraint Library: Check the list of predefined "impractical conditions" in your optimization software. This should automatically filter out unsafe combinations, such as NaH in DMSO or temperatures above a solvent's boiling point [15].

- Inspect Factor Ranges: Verify that the upper and lower bounds set for continuous variables (e.g., temperature, concentration) are aligned with practical laboratory constraints and chemical knowledge [23].

Resolution Strategies:

- Pre-define a Plausible Reaction Set: Before optimization begins, work with chemists to define the reaction condition space as a discrete set of plausible conditions. This allows for automatic filtering based on domain expertise and process requirements [15].

- Incorporate Hard Constraints: Implement an adaptive constraint system that dynamically updates based on the objective function. For example, ABC-BO uses knowledge of the objective to avoid conditions that are mathematically futile, which often overlap with chemically impractical ones [25].

Challenge: Optimization Stagnates at a Local Optimum

Symptoms:

- Sequential experimental batches show minimal or no improvement.

- The algorithm repeatedly suggests similar conditions in a small region of the search space.

- The global best performance plateaus well below the theoretical maximum.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Analyze Exploration-Exploitation Balance: Review the parameters of your acquisition function. An over-emphasis on exploitation (refining known good conditions) can trap the algorithm in a local optimum [15].

- Evaluate Search Space "Roughness": Analyze the reaction landscape. "Rough" landscapes with many reactivity cliffs are harder to optimize and may require algorithms with stronger exploration capabilities [24].

Resolution Strategies:

- Tune Algorithm Parameters: For

α-PSO, adjust the cognitive (c_local), social (c_social), and ML guidance (c_ml) parameters to encourage more exploration. For BO, adjust the acquisition function to favor higher uncertainty [24]. - Strategic Re-initialization: Use ML-guided particle reinitialization to jump from stagnant local optima to more promising regions of the reaction space [24].

- Switch Acquisition Functions: For Bayesian optimization, consider using the q-NParEgo or Thompson sampling with hypervolume improvement (TS-HVI) functions, which are designed to handle parallel batch optimization and can improve exploration in high-dimensional spaces [15].

Optimization Algorithm Comparison

The following table summarizes key algorithms for the systematic exploration of chemical search spaces.

| Algorithm | Key Principle | Advantages | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) [15] | Uses a probabilistic model (e.g., Gaussian Process) to predict reaction outcomes and an acquisition function to balance exploration vs. exploitation. | Handles noisy data; sample-efficient; well-suited for multi-objective optimization. | Spaces with limited experimental budget; optimizing multiple objectives (yield, selectivity). |

Particle Swarm Optimization (α-PSO) [24] |

A metaheuristic where "particles" (conditions) navigate the space based on personal and swarm bests, enhanced with ML guidance. | Mechanistically clear and interpretable; highly parallel; effective on rough landscapes. | High-throughput HTE campaigns; users seeking transparent, physics-intuitive optimization. |

| Adaptive Boundary Constraint BO (ABC-BO) [25] | Enhances standard BO by incorporating knowledge of the objective function to dynamically avoid futile experiments. | Reduces wasted experimental effort; increases likelihood of finding global optimum with smaller budget. | Complex reactions with obvious futile zones (e.g., low catalyst loading for high throughput). |

| Sobol Sampling [15] | A quasi-random sequence used to generate a uniformly spread set of initial points in the search space. | Ensures diverse initial coverage; simple to implement; non-parametric. | Initial screening phase to gather foundational data across the entire search space. |

Experimental Protocol: A Standard HTE Optimization Campaign

This protocol outlines a generalized workflow for optimizing a chemical reaction using a highly parallel, machine-learning-guided approach, as demonstrated in pharmaceutical process development [15].

1. Define the Chemical Search Space: - Inputs: Compile a list of all plausible reaction parameters. This typically includes: - Categorical Variables: Ligands, solvents, bases, catalysts, additives. - Continuous Variables: Temperature, concentration, catalyst loading, reaction time. - Constraint Application: Define and apply rules to filter out impractical conditions (e.g., solvent boiling point < reaction temperature, incompatible reagent pairs). The resulting space is a discrete set of all valid reaction conditions [15].

2. Initial Experimental Batch via Sobol Sampling: - Procedure: Use a Sobol sequence algorithm to select the first batch of experiments (e.g., 96 conditions for a 96-well plate). - Purpose: This technique maximizes the coverage of the reaction space in the initial batch, increasing the probability of discovering informative regions that may contain optima [15].

3. Execute Experiments and Analyze Results: - Execution: Run the batch of reactions using an automated HTE platform. - Analysis: Quantify key reaction outcomes (e.g., Area Percent (AP) yield and selectivity for each condition using techniques like UPLC/HPLC [15].

4. Machine Learning Model Training and Next-Batch Selection: - Model Training: Train a machine learning model (e.g., Gaussian Process regressor) on all accumulated experimental data. The model learns to predict reaction outcomes and their associated uncertainties for all conditions in the search space [15]. - Batch Selection: Use an acquisition function (e.g., q-NEHVI for multi-objective BO) to evaluate all conditions and select the next most promising batch of experiments. The function balances exploring uncertain regions and exploiting known high-performing areas [15].

5. Iterate and Converge: - Iteration: Repeat steps 3 and 4 for as many cycles as the experimental budget allows. - Convergence Criteria: Terminate the campaign when performance plateaus, a satisfactory condition is identified, or the budget is exhausted [15].

Workflow Diagram: ML-Guided High-Throughput Optimization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Optimization | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Precious Metal Catalysts (e.g., Ni) [15] | Catalyse cross-coupling reactions (e.g., Suzuki reactions) as a more sustainable and cost-effective alternative to precious metals like Pd. | Earth-abundant; can exhibit unexpected reactivity patterns that require careful optimization of supporting ligands [15]. |

| Ligand Libraries [15] | Modulate the activity and selectivity of metal catalysts. A key categorical variable in optimizing metal-catalysed reactions. | Diversity of electronic and steric properties is crucial for exploring a broad chemical space and finding optimal catalyst systems [15]. |

| Solvent Libraries [15] | Medium for the reaction; can profoundly influence reaction rate, mechanism, and selectivity. | Includes solvents of varying polarity, proticity, and environmental impact (adhering to guidelines like the FDA's permissible solvent list) [24]. |

| Additives (e.g., Salts, Acids/Bases) [15] | Fine-tune reaction conditions by modulating pH, ionic strength, or acting as scavengers. | Can be critical for overcoming specific reactivity hurdles, such as suppressing catalyst deactivation or promoting desired pathways [15]. |

Algorithm Decision Diagram: Choosing an Optimization Strategy

Implementing DoE, Bayesian Optimization, and HTE for Pharmaceutical Applications

FAQs: Applying DoE in Catalytic Hydrogenation

Q1: How can DoE help me optimize a catalytic hydrogenation process more efficiently than traditional methods?

Changing one parameter at a time is an inefficient Edisonian approach that can miss critical parameter interactions. DoE is a statistical method that investigates the effects of various input factors on specific responses by generating a set of experiments that cover the entire design space in a structured way. This allows researchers to:

- Identify Significant Factors: Determine which parameters (e.g., temperature, pressure, catalyst loading) truly influence the reaction outcome.

- Model Responses: Create a mathematical regression model that predicts outcomes like conversion or selectivity based on the input factors.

- Reveal Interactions: Uncover how parameters interact with one another, which is impossible with one-factor-at-a-time approaches [26].

Q2: I am studying a novel Mn-based hydrogenation catalyst. What is a practical DoE approach to begin understanding its kinetics?

A powerful strategy is to use a Response Surface Design (RSD). For a kinetic study, you can employ a central composite face-centered design. This involves:

- Selecting Key Factors: Choose continuous regressors like temperature, H₂ pressure, catalyst concentration, and concentration of a base (if required).

- Setting Levels: Test each factor at three levels: a lower boundary, a mid-point, and a higher boundary.

- Randomized Runs: Perform a series of randomized experiments (e.g., 30 runs) as defined by the design to map the effects of each regressor and their interactions. This approach allows you to construct a polynomial regression equation that provides a detailed kinetic description of the catalyst, capturing different reaction regimes and the effect of condition parameters on the reaction rate [27].

Q3: My catalytic system shows unexpected deactivation. How can DoE help troubleshoot this issue?

DoE can help systematically rule out or confirm potential causes of deactivation. You should design an experiment that includes factors related to stability, such as:

- Process Conditions: Temperature, reaction time, and impurity levels (e.g., controlled additions of a suspected poison).

- Catalyst Environment: Concentration of reactants or additives that might inhibit deactivation. By analyzing the model's response (e.g., catalyst lifetime or conversion over time), you can identify which factors significantly contribute to deactivation and optimize them to prolong catalyst life [26] [28].

Q4: In a recent CO2 hydrogenation experiment, increasing the gas flow rate unexpectedly boosted the reaction rate, contrary to traditional rules. Why?

You may be observing a "dynamic activation" effect. In a novel reactor design, using the reaction gas stream at high linear velocity to blow catalyst particulates against a rigid target can create highly active sites through collisions. This process leads to:

- Lattice Distortion: Creates a discrete condensed state with a distorted and elongated lattice.

- Reduced Coordination: Lowers the coordination number of metal sites.

- Mechanism Shift: Alters the reaction mechanism, significantly suppressing side reactions like CO formation and dramatically enhancing desired product selectivity (e.g., methanol) [29]. This phenomenon challenges classical kinetics, where reaction rates are considered independent of flow rate, and highlights the importance of considering dynamic catalyst states in your experimental design.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Poor Selectivity in CO2 Hydrogenation to Methanol

Problem: Low methanol selectivity and high CO production from CO2 hydrogenation.

| Potential Cause | Investigation Method using DoE | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Inherent catalyst properties | Design experiments with catalyst composition (e.g., Cu/ZnO ratio, use of In2O3) as a factor. | Optimize the catalyst formulation to create symbiotic interfaces that integrate acid-base and redox functions [30]. |

| Reaction temperature too high | Use a DoE model to map selectivity as a function of temperature and pressure. | Lower the reaction temperature. Thermodynamically, methanol formation is favored at lower temperatures, while the competing Reverse Water-Gas Shift (RWGS) to CO is endothermic and favored at higher temperatures [30]. |

| Insufficient reaction pressure | Include pressure as a factor in a Response Surface Design. | Increase reaction pressure. Methanol synthesis involves a reduction in the number of molecules and is thus favored by higher pressures [30]. |

| Static catalyst surface state | Experiment with gas hourly space velocity (GHSV) as a DoE factor to probe for dynamic effects. | Explore reactor designs that enable dynamic activation, where high-velocity gas flow creates transient active sites, which can inhibit CO desorption and boost methanol selectivity to over 95% [29]. |

Guide 2: Managing Catalyst Deactivation and Poisoning

Problem: Observed activity of the catalyst decreases over time.

| Symptom | Likely Cause | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid initial activity drop | Catalyst poisoning by strong-binding impurities in the feedstock. | Implement pre-treatment steps to remove catalyst poisons. Consider using poison inhibitors as additives that selectively bind to impurities, protecting the catalyst's active sites [28]. |

| Gradual activity decline | Sintering (fusion of catalyst particles at high temperature) or fouling (coking, by-product accumulation). | Optimize temperature to minimize sintering. Use regeneration techniques like thermal treatment to burn off deposits or chemical regeneration to restore active sites [28]. |

| Loss of active metal | Leaching of metal from homogeneous catalysts or stripping in dynamic systems. | For homogeneous catalysts, optimize ligand environment to enhance metal stability. For dynamic systems, ensure the collision energy is appropriate for the catalyst's bonding strength to prevent excessive stripping [29] [27]. |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a DoE for Kinetic Analysis of a Homogeneous Hydrogenation Catalyst

This protocol is adapted from a study on a Mn(I) pincer catalyst for ketone hydrogenation [27].

Objective: To rapidly obtain a detailed kinetic description and understand the effect of key process variables.

Materials:

- Homogeneous catalyst (e.g., Mn-CNP complex)

- Substrate (ketone)

- Solvent

- Base additive (e.g., KO^tBu)

- High-pressure autoclave reactors

Methodology:

- Factor Selection: Identify four continuous factors to study: Temperature (T), Hydrogen Pressure (P_H₂), Catalyst Concentration ([Cat]), and Base Concentration ([Base]).

- Experimental Design: Employ a Central Composite Face-Centered (CCF) Response Surface Design. This requires testing each factor at three levels (-1, 0, +1). The total number of experiments includes cube points, axial points, and center point replicates (e.g., 30 runs).

- Randomization: Randomize the order of all experimental runs to minimize the effects of confounding variables.

- Reaction Execution: Carry out hydrogenation reactions according to the designed matrix. Use average reaction rate (concentration of product / time) as the response.

- Data Analysis:

- Perform a multiple polynomial regression analysis on the data. The initial model will include linear, quadratic, and interaction terms.

- Use statistical measures (p-values, R², predicted R²) to eliminate insignificant terms via a stepwise elimination algorithm.

- The final regression equation provides a model that maps the response of the reaction rate to the input parameters, offering insights into the reaction kinetics and mechanism.

Protocol 2: Testing for Dynamic Activation Effects in a Heterogeneous System

This protocol is based on a study of Cu/Al₂O₃ for CO₂ hydrogenation [29].

Objective: To determine if a catalyst's performance can be enhanced by a dynamic activation process driven by high-velocity gas flow.

Materials:

- Catalyst powder (e.g., 40% Cu/Al₂O₃)

- Dynamic Activation Reactor (DAR) with a nozzle and rigid target.

- Reaction gases (CO₂/H₂ mixture).

Methodology:

- Reactor Setup: Load catalyst powder between the nozzle and the rigid target in the DAR.

- Baseline Measurement: First, test the catalyst in a traditional fixed-bed reactor (FBR) mode to establish baseline performance (conversion, selectivity, space-time-yield).

- Dynamic Activation Test: Switch to the DAR mode. Feed the CO₂/H₂ mixture through the nozzle at a high linear velocity (e.g., ~452 m/s at nozzle exit) to blow catalyst particulates, causing them to collide cyclically with the target.

- Performance Monitoring: Analyze the tail gas using online GC. Key metrics to track include:

- CO₂ Conversion

- Methanol Selectivity

- Methanol Space-Time-Yield (STY)

- CO Selectivity

- Comparison: Compare the performance metrics from the DAR mode with the FBR baseline. A significant increase in STY and a dramatic shift in selectivity away from CO and towards methanol are indicators of a successful dynamic activation effect.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Performance Comparison of CO2 Hydrogenation Catalysts and Conditions

| Catalyst System | Reaction Conditions | Key Performance Metrics | Reference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature (°C) | Pressure (MPa) | Reactor Type | CO2 Conv. (%) | MeOH Select. (%) | MeOH STY (mg·gcat⁻¹·h⁻¹) | ||

| 40% Cu/Al₂O₃ | 300 | 2.0 | Fixed Bed (FBR) | ~(see reference) | < 40 | ~100 | [29] |

| 40% Cu/Al₂O₃ | 300 | 2.0 | Dynamic Activation (DAR) | > 3x FBR rate | ~95 | 660 | [29] |

| Cu-ZnO-Al₂O₃ | 220-270 | 5-10 | Fixed Bed | Varies with conditions | High activity, limited selectivity | (Industry standard) | [30] |

| In₂O₃-based | 300-350 | 5 | Fixed Bed | High selectivity and stability | > 90 | (High selectivity) | [30] |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Catalytic Hydrogenation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Pincer Ligand Complexes (e.g., Mn-CNP, Fe-A) | Homogeneous catalysts, often based on earth-abundant metals, providing highly tunable and selective platforms for hydrogenation [27]. |

| Noble Metal Catalysts (e.g., Pd/C, Pt/Al₂O₃, Rh complexes) | Heterogeneous and homogeneous catalysts offering high activity and selectivity; Pd is common for alkene hydrogenation, Rh/Ru for asymmetric synthesis [28]. |

| Reducible Oxide Supports (e.g., In₂O₃, ZrO₂, CeO₂) | Catalyst supports that can activate CO₂ and create symbiotic interfaces with metal sites, enhancing selectivity in CO₂ hydrogenation to methanol [30]. |

| Base Additives (e.g., KO^tBu) | Often required in homogeneous hydrogenation to generate the active metal-hydride species from H₂ [27]. |

| Poison Inhibitors | Additives used to protect catalyst active sites by selectively binding to impurities in the feedstock that would otherwise cause deactivation [28]. |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: DoE Workflow for Catalytic Hydrogenation Research.

Diagram 2: Static vs. Dynamic Catalyst Activation.

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Gaussian Process (GP) Model Issues

Problem 1: Poor Surrogate Model Performance and Inaccurate Predictions

- Symptoms: The GP model fails to fit existing data points, shows poor cross-validation scores, or provides unrealistic uncertainty estimates (very wide or very narrow confidence bands).

- Solutions:

- Check Kernel Selection: The default kernel may be unsuitable for your objective function's smoothness. For modeling physical phenomena, the Matérn kernel (e.g., Matérn-5/2) is often preferred over the common Radial Basis Function (RBF) due to its flexibility in modeling different smoothness levels [31].

- Inspect Data Preprocessing: Ensure input features are properly normalized. GP performance can be sensitive to the scale of input variables.

- Review Hyperparameters: Optimize GP hyperparameters (length scale, noise level) via maximum likelihood estimation or Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods, rather than using default values.

Problem 2: Inability to Handle High-Dimensional or Discontinuous Search Spaces

- Symptoms: Optimization fails to converge, or performance degrades significantly as the number of dimensions increases beyond ~20.

- Solutions:

- Consider Advanced Surrogates: For complex, high-dimensional materials spaces, replace standard GPs with Deep Gaussian Processes (DGPs) or Random Forest surrogates. DGPs can model hierarchical relationships and are more effective for capturing complex, non-linear composition-property relationships in materials science [32] [31] [33].

- Implement Dimensionality Reduction: Apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or autoencoders to reduce parameter space dimensionality before optimization.

- Use Domain Knowledge: Incorporate known physical constraints or relationships into the kernel design to guide the model in high-dimensional spaces.

Acquisition Function Optimization Challenges

Problem 1: Over-Exploration or Over-Exploitation

- Symptoms: The optimization process either (a) spends too many evaluations exploring unpromising regions with high uncertainty, or (b) converges prematurely to a local optimum.

- Solutions:

- Tune Exploration Parameters: For Upper Confidence Bound (UCB), adjust the

λparameter: decreaseλfor more exploitation (focusing on known good areas), increaseλfor more exploration (probing uncertain regions) [34]. - Use Adaptive Trade-off: For Expected Improvement (EI), implement a dynamic trade-off value

τthat starts with higher exploration (largerτ) and gradually shifts toward exploitation (smallerτ) as the optimization progresses [35]. - Switch Acquisition Functions: If one acquisition function performs poorly, try alternatives. Expected Improvement generally provides a better balance than Probability of Improvement, which can be too greedy [34] [36].

- Tune Exploration Parameters: For Upper Confidence Bound (UCB), adjust the

Problem 2: Failed or Slow Optimization of the Acquisition Function

- Symptoms: The process of finding the maximum of the acquisition function itself becomes a bottleneck, failing to find good candidate points in a reasonable time.

- Solutions:

- Use Global Optimizers: Replace local optimizers (e.g., L-BFGS) with global methods such as evolutionary algorithms or multi-start strategies when optimizing acquisition functions, especially in multi-modal landscapes [37] [36].

- Consider Mixed-Integer Programming: For guaranteed global convergence, recent research has explored Mixed-Integer Quadratic Programming (MIQP) with piecewise-linear kernel approximations to provably optimize acquisition functions [38].

- Implement Batch Optimization: Use parallel batch methods like q-EHVI (q-Expected Hypervolume Improvement) to select multiple points simultaneously, reducing total optimization time [31].

Multi-Objective and Constrained Optimization Difficulties

Problem 1: Handling Multiple Competing Objectives

- Symptoms: The optimization struggles to identify materials that balance multiple property trade-offs (e.g., strength vs. cost, thermal stability vs. conductivity).

- Solutions:

- Use Multi-Task Gaussian Processes (MTGPs): Instead of independent GPs for each objective, implement MTGPs or Multi-Output GPs that explicitly model correlations between different material properties, leading to more efficient optimization [32].

- Apply Pareto-Optimal Methods: Implement multi-objective acquisition functions like Expected Hypervolume Improvement (EHVI) to approximate the Pareto front of optimal solutions [31].

- Leverage Multi-Fidelity Data: Integrate cheaper, lower-fidelity data (e.g., computational simulations) with expensive high-fidelity data (experimental results) using Multi-Fidelity Bayesian Optimization (MFBO) to reduce total cost while maintaining performance [39].

Problem 2: Incorporating Experimental Constraints

- Symptoms: The algorithm suggests candidate materials that are impractical, unstable, or violate known physical constraints.

- Solutions:

- Use Constrained Bayesian Optimization: Model constraint satisfaction probability with a separate GP and multiply it with the acquisition function to penalize constraint violations [33].

- Implement Domain-Specific Rules: Build in chemical rules and compositional constraints based on domain expertise to avoid "naïve" suggestions that a researcher would immediately rule out [33].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How do I choose the most suitable acquisition function for my materials optimization problem? The choice depends on your specific goals and the nature of your optimization problem. The table below compares the most common acquisition functions:

| Acquisition Function | Best Use Case | Key Parameters | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probability of Improvement (PI) | Quick convergence to a good enough solution when computational budget is very limited [34]. | None explicit | Simple, computationally light | Overly exploitative; prone to getting stuck in local optima [34] [36] |

| Expected Improvement (EI) | General-purpose optimization; balancing progress and discovery [34] [35] [40]. | Trade-off (τ) to balance exploration/exploitation [35] |

Good balance; considers improvement magnitude [34] | May not explore aggressively enough in high-dimensional spaces |

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | Problems where explicit exploration-exploitation control is needed [34]. | Exploration weight (λ) [34] |

Explicit parameter control; theoretical guarantees | Parameter λ needs tuning for different problems [34] |

| q-Expected Hypervolume Improvement (q-EHVI) | Multi-objective optimization with batch evaluations [31]. | Number of batch points (q) |

Handles multiple objectives; enables parallel experiments | Computationally intensive; increased complexity [31] |

Q2: When should I consider using advanced surrogate models like Deep Gaussian Processes (DGPs) over standard GPs? Consider DGPs when:

- Property Correlations Exist: You are optimizing multiple material properties that are correlated. DGPs and Multi-Task GPs (MTGPs) can exploit these correlations, unlike conventional GPs that model properties independently [32].

- Highly Nonlinear Relationships: Your composition-property relationships are complex, non-stationary, or hierarchical in nature [31].

- Data is Heterotopic: You have incomplete datasets where not all properties are measured for all samples, which is common in materials research [31].

Q3: Why is my Bayesian optimization performing poorly with high-dimensional materials formulations? Standard GP-based BO faces several challenges in high-dimensional spaces:

- Exponential Computational Growth: GP computation time scales cubically with the number of data points and exponentially with dimensions [33].

- Sparse Data Space: In high dimensions, data becomes sparse, making it difficult for GPs to build accurate models without an infeasible number of samples [33].

- Solution Approaches:

- Use Random Forest surrogates with uncertainty estimates, which handle high-dimensional, discontinuous spaces more effectively [33].

- Implement DGPs that can learn latent representations of high-dimensional inputs [31].

- Apply dimensionality reduction techniques to the parameter space before optimization.

Q4: How can I make my Bayesian optimization process more interpretable for scientific review?

- Use Explainable Surrogates: Random Forests provide feature importance measures and SHAP values that quantify how much each input parameter contributes to predictions [33].

- Visualize Partial Dependencies: Create plots showing how individual input variables affect predicted properties while holding others constant.

- Incorporate Domain Knowledge: Build in physical rules and constraints that make suggestions more chemically or physically plausible, increasing trust in the recommendations [33].

Q5: What are effective strategies for managing computational budgets in expensive materials simulations?