A Strategic Guide to Buffer Selection and Control for Robust Kinetic Studies in Biocatalysis and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the critical role of buffer selection and control in kinetic studies.

A Strategic Guide to Buffer Selection and Control for Robust Kinetic Studies in Biocatalysis and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on the critical role of buffer selection and control in kinetic studies. It covers foundational principles of buffer chemistry, methodological applications in enzyme kinetics and bioprocessing, advanced troubleshooting for common challenges like aggregation and viscosity, and rigorous validation techniques. By synthesizing current trends and data-driven strategies, this guide aims to enhance the reproducibility, accuracy, and predictive power of kinetic experiments, ultimately accelerating the development of stable biologics and biosimilars.

The Fundamentals of Buffer Chemistry: Building a Foundation for Kinetic Integrity

Buffer solutions are indispensable in biochemical and kinetic studies, where maintaining a stable pH is critical for accurate and reproducible results. Their effectiveness hinges on a few core principles: the acid dissociation constant (pKa), which dictates the optimal pH working range; the buffer capacity, which quantifies its resistance to pH change; and the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation, which provides a mathematical relationship between pH, pKa, and the concentrations of the buffer components [1] [2]. Proper selection and preparation of buffers based on these principles are foundational to successful control experiments in drug development and enzymatic research [3] [4].

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the most critical factor when selecting a buffer for my kinetic assay? The most critical factor is the pKa of the buffering agent. For a buffer to be effective, its pKa should be within ±1 unit of your desired working pH [3] [5]. This ensures the buffer has maximum capacity to resist pH changes. Additionally, the buffer should not interact with or inhibit your system; for example, high phosphate concentrations are known to inhibit enzymes like cis-aconitate decarboxylase (ACOD1) [4].

2. My buffer isn't maintaining pH, leading to inconsistent kinetic results. What could be wrong? This is a common problem with a few likely causes:

- Incorrect pKa Selection: The pKa of your buffer is too far from your target pH, resulting in low buffer capacity [5] [6].

- Insufficient Buffer Concentration: The concentration of the weak acid and conjugate base in your solution is too low to neutralize the acids or bases being generated in your assay [6].

- Dilution of a Stock Solution: Diluting a pH-adjusted concentrated stock buffer with water will change its pH, leading to an incorrect final working concentration and ionic strength [3].

- Incorrect Preparation: "Overshooting" the pH during adjustment and then correcting it with acid or base alters the ionic strength of the final solution, which can affect the assay [3].

3. How does the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation help in practical buffer preparation? This equation allows you to calculate the exact ratio of conjugate base ([A⁻]) to weak acid ([HA]) needed to achieve a specific pH [7] [2]. The equation is: pH = pKa + log₁₀([A⁻]/[HA]) For instance, if you want to prepare an acetate buffer at pH 5.0 (pKa = 4.8), you can calculate that you need a ratio of [A⁻]/[HA] of approximately 1.6. This means for every mole of acetic acid, you need 1.6 moles of acetate salt to get your desired pH [1].

4. Why does my enzymatic activity drop in one buffer but not another, even at the same pH? The buffer substance itself can directly affect the enzyme. Specific ions can act as inhibitors or, in some cases, activators. As documented in a 2025 study, a 167 mM phosphate buffer competitively inhibited cis-aconitate decarboxylase (ACOD1) activity compared to MOPS or HEPES buffers at the same pH. This was attributed to phosphate ions potentially blocking the enzyme's active site [4]. This underscores the importance of testing multiple buffer types during assay development.

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Drifting pH during assay | Low buffer capacity; pKa too far from target pH; buffer concentration too low. | Select a buffer with a pKa within ±1 of target pH; increase the concentration of the buffer species [5] [6]. |

| Poor reproducibility between preparations | Vague buffer recipe; inconsistent pH adjustment procedure; diluting pH-adjusted stock solutions [3]. | Document the exact salt form, concentration, and pH adjustment procedure (including acid/base molarities). Prepare the buffer at its final working concentration [3]. |

| Unexpectedly high current in electrophoretic systems | High ionic strength buffer; inappropriate counter-ion [3]. | Switch to a buffer with lower conductivity (e.g., a "Good's buffer" like TRIS or MES) or a larger counter-ion to reduce current generation [3]. |

| Reduced enzymatic activity or reaction rate | Buffer-specific inhibition; incorrect ionic strength; wrong pH for optimal activity [4]. | Screen alternative buffers (e.g., MOPS, HEPES, Bis-Tris) at the desired pH; adjust and control for ionic strength with salts like NaCl [4]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their functions in buffer-based experiments.

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| MOPS Buffer | A "Good's buffer" often used as an alternative to phosphate; with a pKa of ~7.0, it is useful for a physiological pH range and has low metal-binding properties, reducing enzyme inhibition [4]. |

| Phosphate Buffer | A common inorganic buffer with high buffering capacity in the pKa range of ~2.1, 7.2, and 12.3. Can inhibit some enzymes at high concentrations and has a high ionic strength [4]. |

| HEPES Buffer | Another "Good's buffer" (pKa ~7.5) suitable for physiological pH. It is widely used in cell culture and biochemistry but can form radicals under photo-oxidation [4]. |

| Bis-Tris Buffer | A "Good's buffer" with a pKa of ~6.5, ideal for slightly acidic conditions. It is often used in protein purification and crystallization [4]. |

| NAD+ (Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide) | A common coenzyme used in oxidation-reduction reactions, such as those catalyzed by glucose dehydrogenase (GDH) [8]. |

| Glucose Dehydrogenase (GDH) | An enzyme that catalyzes the oxidation of glucose, often used in biohydrogen production research and biosensors. It serves as a model enzyme for kinetic studies [8]. |

Quantitative Data for Common Buffers

Use this table to select a buffer based on its effective range, which is typically pKa ± 1 [3] [6].

| Buffer | pKa (at or near 25°C) | Effective pH Range |

|---|---|---|

| Citric Acid (pKa1) | 3.1 | 2.1 - 4.1 |

| Citric Acid (pKa2) | 4.7 | 3.7 - 5.7 |

| Citric Acid (pKa3) | 5.4 | 4.4 - 6.4 |

| Acetic Acid | 4.8 | 3.8 - 5.8 |

| Sodium Phosphate (pKa2) | 7.2 | 6.2 - 8.2 |

| MOPS | 7.0 | 6.0 - 8.0 |

| HEPES | 7.5 | 6.5 - 8.5 |

| TRIS | 8.1 | 7.1 - 9.1 |

Detailed Protocol: Determining the Impact of Buffer Type on Enzyme Kinetics

This protocol is adapted from a 2025 study investigating cis-aconitate decarboxylase and serves as a model for testing buffer effects in kinetic studies [4].

Objective: To determine the kinetic parameters (KM and kcat) of an enzyme in different buffer systems and identify potential buffer inhibition.

Materials:

- Purified enzyme (e.g., GDH, ACOD1).

- Substrate solution.

- Assay reagents for product detection (e.g., NAD+ for GDH [8]).

- Buffers for testing (e.g., 50 mM MOPS, HEPES, Bis-Tris, Sodium Phosphate).

- NaCl to maintain constant ionic strength.

- pH Meter.

- Microtiter plate or cuvettes.

- Thermostatted plate reader or spectrophotometer.

Method:

- Buffer Preparation: Prepare each buffer (e.g., MOPS, Phosphate, HEPES) at the same pH (e.g., 7.5) and temperature (e.g., 37°C). Include 100 mM NaCl in all buffers to ensure a consistent and comparable ionic strength [4].

- Reaction Setup: In a microtiter plate, mix the buffer, enzyme, and varying concentrations of substrate. For a GDH assay, the reaction mixture would include buffer, NAD+, glucose, and the GDH enzyme [8].

- Activity Measurement: Initiate the reaction by adding the enzyme and immediately monitor the initial rate of the reaction (e.g., by measuring the increase in absorbance from NADH production at 340 nm) over time [8].

- Data Analysis: For each buffer condition, plot the initial reaction rate (V₀) against substrate concentration ([S]). Fit the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation to determine the apparent KM and kcat for each buffer [4].

- Interpretation: A significantly higher KM value in one buffer (e.g., phosphate) compared to others, while kcat remains relatively unchanged, indicates competitive inhibition by that buffer substance [4].

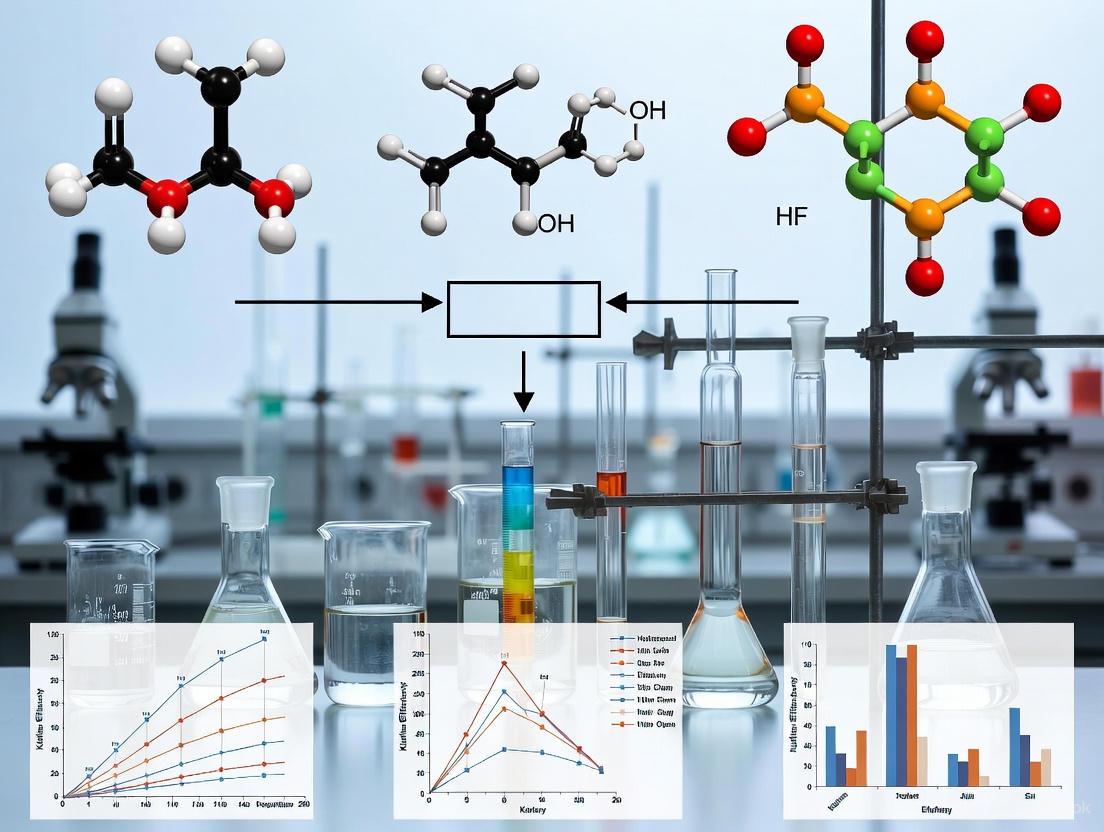

Experimental Workflow and Buffer Mechanics

The following diagram illustrates the logical process of selecting, testing, and troubleshooting a buffer system for a kinetic study.

Logical workflow for buffer selection and validation in kinetic studies

The relationship between pH, pKa, and the state of a weak acid is fundamental to understanding how buffers work, as summarized in the diagram below.

Relationship between solution pH and buffer dissociation state

This guide provides a technical resource for researchers on the use and troubleshooting of common biological buffers—Phosphate, TRIS, HEPES, and Histidine—within the context of kinetic studies and drug development.

In kinetic studies, where the focus is on measuring reaction rates, maintaining a stable pH is non-negotiable. Even minor fluctuations in hydrogen ion concentration can alter the charge state of amino acids in an enzyme's active site, dramatically affecting its activity, substrate binding, and overall reaction kinetics. Buffers are primarily chosen to control pH, but they are not inert spectators. As outlined in a comprehensive review, buffers can impact protein stability through mechanisms like ligand binding and colloidal stabilization, and can even act as scavengers in some cases [9]. Selecting the appropriate buffer and controlling for its non-pH effects are therefore critical components of experimental design, ensuring that the observed kinetics are a true reflection of the enzyme's mechanism and not an artifact of the buffer system.

The table below summarizes the key properties of the four common buffers to guide initial selection.

| Buffer | Typical pH Range | pKa at 25°C | Key Advantages | Key Considerations and Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphate | 5.8 - 8.0 [10] | 7.2 (pKa₂) | Inexpensive; high buffering capacity at physiological pH. | Forms precipitates with Ca²⁺ & other divalent cations [11] [9]; concentration-dependent pKa shift [11]. |

| TRIS | 7.0 - 9.0 [12] | ~8.1 | Effective for a broad alkaline range; common in molecular biology. | Strong temperature dependence [11] [12]; reacts with DEPC [11]; may interfere with some assays [9]. |

| HEPES | 6.8 - 8.2 [13] | ~7.5 | Good for cell culture; one of Good's buffers. | Can react with DEPC [11]; may form radicals under certain conditions [9]. |

| Histidine | 5.5 - 7.0 [9] | ~6.1 (pKa₂) | Common in therapeutic protein formulations; low concentration needed. | Metal chelator [9]; can undergo photo-degradation [9]. |

Note: pKa values are approximate and can vary with temperature and ionic strength.

A Framework for Buffer Selection and Optimization

Choosing the right buffer involves more than just matching the pKa to your target pH. The following workflow outlines a systematic approach to buffer selection and validation for sensitive applications like kinetic studies.

Beyond the pKa, consider these critical factors:

- Anticipate pH Changes: If your reaction is expected to release protons (e.g., ATP hydrolysis), choose a buffer with a pKa slightly below your target pH. If it consumes protons, choose a pKa slightly above [14].

- Optimize Concentration: For systems without active proton exchange, 25-100 mM is often sufficient. For reactions involving proton transfer, the buffer concentration should be at least 20 times the molar concentration of protons consumed or released [14].

- Account for Temperature: The pKa of many buffers, especially TRIS, is highly temperature-dependent. Always prepare and adjust your buffer at the temperature at which your experiment will be performed [11] [14].

Troubleshooting Common Buffer-Related Issues

Why is my enzyme activity low or inconsistent, even at the correct pH?

This is a common issue in kinetic studies where the buffer itself is interfering with the reaction.

- Possible Cause 1: Buffer-Specific Inhibition. The buffer may be acting as a competitive inhibitor or directly interacting with the enzyme. For instance, citrate is a known chelator of calcium, and TRIS contains a reactive amine that can interfere with certain reactions [11] [9].

- Solution: Perform a buffer screen. Test your enzyme's activity in several different buffers at the same pH and ionic strength (e.g., Phosphate, HEPES, and Imidazole). This helps identify the most compatible buffer for your specific protein [9].

- Possible Cause 2: Inadequate Buffering Capacity. The buffer concentration may be too low to handle proton flux from the reaction, causing a local pH shift.

- Solution: Increase the buffer concentration, ensuring it remains isotonic and does not negatively impact other reaction components [14].

Why am I observing high background noise or precipitation in my assay?

- Possible Cause 1: Non-specific Binding or Interactions. Buffers can participate in unwanted interactions. Phosphate buffers are known to form precipitates with calcium ions, and certain buffers can bind non-specifically to proteins or sensor chips in techniques like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) [11] [15].

- Solution: Review the chemical properties of your buffer. If using phosphate and encountering precipitation, switch to a non-coordinating buffer like HEPES or MOPS. For binding studies, optimize surface blocking and include detergents like Tween-20 to minimize non-specific binding [15].

- Possible Cause 2: Buffer Contamination or Degradation. Some organic buffers, like histidine, are susceptible to photo-degradation. Contaminants in the buffer can also catalyze decomposition reactions [9].

- Solution: Prepare fresh buffer solutions, protect light-sensitive buffers from light, and use high-purity reagents [16] [9].

Why are my results not reproducible between experiments?

- Possible Cause: Inconsistent Buffer Preparation and Handling. Small variations in how a buffer is made or stored can lead to significant differences in pH and ionic strength, which in turn affect kinetic parameters.

- Solution: Standardize your protocol. Key steps include:

- Prepare at the Correct Temperature: Always adjust the pH at the temperature your experiment will be run, especially for temperature-sensitive buffers like TRIS [11].

- Correct Dilution: Diluting a buffer from a concentrated stock can change its pH. Check and, if necessary, adjust the pH after dilution [11].

- Proper Calibration: Regularly calibrate your pH meter with fresh standard buffers [11].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials and their functions for setting up robust buffer-controlled experiments.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Water | Prevents interference from trace ions and organic contaminants in sensitive biochemical assays [16]. |

| HPLC-Grade Solvents & Salts | Ensures low UV background and avoids contamination in analytical techniques and sensitive reactions [16]. |

| pH Meter & Calibration Buffers | Ensures accurate and reproducible pH adjustment, which is foundational for reliable results [11]. |

| 0.2 µm Syringe Filters | Removes particulates and microbial contaminants from buffer solutions to prevent interference and degradation [16]. |

| Blocking Agents (e.g., BSA, Casein) | Used in techniques like SPR or Western blotting to occupy non-specific binding sites on surfaces, reducing background noise [15] [17]. |

Advanced Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Buffer Screening for Enzyme Kinetic Studies

Objective: To identify the optimal buffer for maintaining maximum enzyme stability and activity.

- Select Buffers: Choose 3-4 buffers with pKa values within ±1 of your target pH (e.g., Phosphate, HEPES, MOPS, Imidazole for pH ~7.5).

- Prepare Solutions: Prepare 50-100 mM stock solutions of each buffer. Adjust the pH at your experimental temperature. Ensure the final ionic strength is identical in all buffers by adding a salt like NaCl.

- Initial Activity Test: Incubate your enzyme in each buffer system and measure the initial reaction rate under standard assay conditions.

- Stability Assessment: Pre-incubate the enzyme in each buffer at the experimental temperature. Remove aliquots at various time points (e.g., 0, 30, 60, 120 min) and measure residual activity.

- Analysis: The optimal buffer is the one that supports the highest initial activity and maintains the greatest stability over time.

Protocol 2: Testing for Buffer-Enzyme Complex Formation

Objective: To determine if a buffer is acting as a ligand and stabilizing the enzyme conformation.

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): This is the most direct method. Prepare your protein sample in the buffers of interest.

- Run DSC: Heat the samples and measure the heat capacity change. A higher melting temperature (Tm) in a specific buffer indicates stabilization, likely through ligand binding [9].

- Alternative: Thermal Shift Assay: A more accessible method. Use a fluorescent dye that binds to hydrophobic regions of unfolded protein. A higher Tm in the DSC curve corresponds to a higher denaturation temperature in the thermal shift assay, indicating stabilization by the buffer [9].

In kinetic studies and drug development, the choice of a biological buffer is a critical variable that goes far beyond simple pH control. A methodical approach to buffer selection—one that considers pKa, chemical compatibility, and experimental conditions—is essential for generating reliable and reproducible data. By understanding the properties and potential pitfalls of common buffers like Phosphate, TRIS, HEPES, and Histidine, researchers can optimize their experimental conditions, effectively troubleshoot issues, and ensure the integrity of their scientific findings.

FAQs: Understanding pH Fundamentals in Enzyme Kinetics

1. Why does pH specifically affect enzyme activity? pH primarily affects the ionic state of amino acid residues in the enzyme's active site and throughout the protein structure. Key catalytic residues often rely on specific protonation states (such as in acidic or basic side chains) to properly bind substrates or participate in catalysis. When pH changes alter these charges, ionic bonds that stabilize the substrate-enzyme complex or the enzyme's tertiary structure can be disrupted, leading to reduced activity or complete inactivation [18]. This effect is reversible within a moderate pH range but becomes irreversible at extremes due to permanent denaturation [19].

2. What does the "pH optimum" mean, and is it an absolute value? The pH optimum is the pH value at which an enzyme exhibits its maximum catalytic activity [20]. No, it is not an absolute value and can vary significantly between enzymes [18] [19]. For example, pepsin from the stomach functions optimally at pH 1.5-1.6, while trypsin from the small intestine has an optimum of pH 7.8-8.7 [18] [20]. The observed optimum can also depend on the specific reaction conditions and the kinetic parameter being measured (e.g., k₀ or k_A) [19].

3. How can pH changes lead to irreversible enzyme inactivation? While pH effects are often reversible within a narrow range, extreme pH values can cause irreversible inactivation. This typically occurs due to the disruption of ionic bonds that maintain the enzyme's tertiary structure, leading to permanent denaturation and loss of the active site's configuration [18]. In soils, for instance, irreversible inactivation of enzymes like urease and phosphatases is particularly evident at extreme acidic and alkaline conditions [21].

4. How is the effect of pH on kinetics formally described? The effects of pH on the kinetic parameters of an enzyme following Michaelis-Menten kinetics can often be represented by an equation analogous to inhibition equations [18] [19]: [ k = \frac{k{opt}}{1 + \frac{[H^+]}{K1} + \frac{K2}{[H^+]}} ] Here, ( k ) represents a kinetic parameter (like ( k0 ) or ( kA )), ( k{opt} ) is the pH-independent value of that parameter, and ( K1 ) and ( K2 ) are acid dissociation constants [18] [19]. This model treats decreased activity on the acid side as inhibition by hydrogen ions and decreased activity on the alkaline side as inhibition by hydroxide ions [19].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common pH-Related Experimental Issues

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common pH-Related Problems in Enzyme Assays

| Observed Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions & Verification Methods |

|---|---|---|

| No or Low Activity | Incorrect buffer pH or buffer capacity exceeded [18].Enzyme irreversibly denatured during storage or handling [22].Cofactor requirement is pH-sensitive [23]. | Verify buffer pH with a calibrated micro-electrode post-preparation.Test enzyme activity with a control substrate under known optimal conditions [22]. |

| Inconsistent Results Between Replicates | Inadequate buffer capacity leading to pH drift during the reaction [18].Poor temperature control affecting pH measurement.Human error in buffer preparation. | Use a buffer with a pKa within 1 unit of your target pH and increase buffer concentration.Standardize buffer preparation and use a calibrated pH meter for verification. |

| Unexpected Cleavage Patterns or Kinetics (e.g., Star Activity) | "Star activity" or off-target cleavage can be induced by incorrect pH, high glycerol concentration, or inappropriate ionic strength [22]. | Strictly adhere to the manufacturer's recommended buffer, pH, and ionic strength conditions [22]. Avoid excessive enzyme concentrations or prolonged incubation times [22]. |

| Gradual Loss of Activity Over Time | Enzyme instability at working pH [8].Slow, irreversible denaturation at the assay pH.Microbial contamination in buffer stocks. | Determine the pH stability profile of the enzyme by pre-incubating it at different pH values before assaying at the optimum [21]. Use sterile filtration for buffer storage. |

Optimizing pH Conditions: A Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Objective: To determine the optimal pH and pH stability profile for an enzyme.

Background: A systematic approach to pH optimization is critical for robust and reproducible kinetic studies. The optimal pH for activity (where the enzyme is most active) can differ from the pH range where the enzyme is most stable [20]. The following protocol outlines a method to characterize both.

Materials:

- Purified enzyme

- Substrate solution(s)

- Buffer series covering a broad pH range (e.g., citrate phosphate for pH 3-7, Tris for pH 7-9, glycine for pH 9-10)

- Equipment: pH meter, spectrophotometer/plate reader, temperature-controlled water bath or incubator

Part A: Determining the pH-Activity Profile

- Prepare Buffer System: Prepare a series of buffers, typically in 0.5 to 1.0 pH unit increments, ensuring sufficient buffering capacity. Confirm the pH of each buffer at the assay temperature.

- Set Up Reactions: In separate tubes, mix the enzyme with the different pH buffers. It is crucial to maintain a constant concentration of all other components (substrate, cofactors, salts).

- Initiate Reaction: Start the reaction by adding substrate and incubate at a constant temperature.

- Measure Initial Velocity: Measure the initial rate of reaction (v₀) for each pH condition.

- Analyze Data: Plot the initial velocity (v₀) against pH. The pH that yields the highest v₀ is the optimum pH for activity under these specific conditions [20].

Part B: Determining the pH-Stability Profile

- Pre-incubate Enzyme: Incubate separate aliquots of the enzyme in the different pH buffers for a fixed, extended period (e.g., 1-24 hours) at the storage or assay temperature.

- Assay Residual Activity: After pre-incubation, remove an aliquot from each tube and assay for remaining enzymatic activity under standard, optimal pH conditions.

- Analyze Data: Plot the residual activity (%) against the pre-incubation pH. This reveals the pH range where the enzyme retains stability over time [20] [21].

The workflow for this optimization process is summarized in the diagram below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for pH and Kinetic Studies

| Reagent / Material | Critical Function in pH/Kinetic Studies |

|---|---|

| Appropriate Biological Buffers (e.g., Tris, Phosphate, HEPES) | Maintains constant pH during the reaction. Choice depends on required pH range, ionic strength, and chemical compatibility (e.g., avoid phosphate with Ca²⁺) [8]. |

| Cofactors (e.g., NAD+, Metal Ions) | Many enzymes require non-protein cofactors for activity. The binding and function of these cofactors can be highly pH-sensitive [23]. |

| Enzyme Stabilizers (e.g., BSA, Glycerol) | Protects the enzyme from denaturation, aggregation, and surface adsorption during storage and assay. Glycerol concentration should be kept <5% in final reactions to avoid inducing star activity [22]. |

| Substrate Solutions | Must be prepared in a compatible buffer or solvent. Product inhibition, which is often pH-dependent, should be assessed during kinetic characterization [8]. |

| Control DNA/Substrate (e.g., λ DNA) | Used to verify enzyme activity and specificity under optimal conditions, serving as a positive control to troubleshoot failed reactions [22]. |

Advanced Considerations: Integrating pH into Broader Kinetic Studies

The Critical Role of Buffer Selection in Control Experiments Buffer selection goes beyond merely matching pKa to target pH. The chemical nature of the buffer can directly impact enzyme activity. For instance, phosphate is a known inhibitor for many phosphatases and kinases. When characterizing a new enzyme, it is good practice to test its activity in 2-3 different buffer systems (e.g., Tris, HEPES, phosphate) all at the same pH to identify potential buffer-specific inhibitory or activating effects. This control experiment ensures that the observed kinetics are a true property of the enzyme and not an artifact of the chosen buffer.

Interpreting Complex pH Profiles A pH profile that is broader or narrower than predicted by simple models may indicate the involvement of multiple ionizable groups or the stabilization of the enzyme by bound substrates or cofactors. Furthermore, some enzymatic reactions themselves consume or produce hydrogen ions, which can cause the pH of a low-capacity buffer to shift during the reaction, complicating kinetic analysis [24]. Using adequate buffering capacity or employing continuous-flow systems like microreactors, which allow for superior parameter control, can mitigate this issue [8].

Connecting pH to Overall Reaction Mechanism pH studies provide key insights into the chemical mechanism. The shape of the pH-activity profile can suggest the pKa values of residues critical for catalysis or substrate binding. In complex, multi-step mechanisms, the effect of pH on different kinetic parameters (e.g., kcat vs. kcat/Km) can be diagnostic. A change in kcat/Km with pH might suggest the involvement of an ionizable group in substrate binding, while a change in kcat could point to a residue involved in the chemical step itself [18] [19]. Integrating these findings with data from inhibition studies and pre-steady-state kinetics is essential for building a complete mechanistic model [19].

FAQs on Fundamental Buffer Properties

Q1: Why is a buffer's pKa value the most critical selection parameter? A buffer's pKa defines the pH range where it exhibits optimal buffering capacity. A buffer effectively resists pH changes when the environmental pH is within approximately ±1 unit of its pKa value. Selecting a buffer with a pKa centered on your experimental pH is therefore essential for maintaining pH stability. Using a buffer outside this range can lead to poor buffering capacity and pH drift, which is particularly detrimental to kinetic studies where enzyme activity is pH-dependent [3].

Q2: How does temperature affect my buffer and how can I account for it?

Temperature changes directly impact a buffer's pKa, which in turn alters the solution's pH. This dependence is expressed as dpKa/dT. For example, Tris buffer has a relatively high dpKa/dT of -0.028 °C⁻¹ at pH 7.0, meaning its pKa decreases significantly as temperature rises. In contrast, the pKa of carboxylic acid-based buffers like MES (dpKa/dT = -0.011 °C⁻¹) is less sensitive to temperature [25] [26]. To account for this:

- Calibrate your pH meter at the same temperature as your experiment.

- Pre-equilibrate all buffer components to the experimental temperature before use and before final pH adjustment.

- Select buffers with a low dpKa/dT for experiments involving temperature shifts.

Q3: What problems can arise from a buffer's ionic strength? High ionic strength can increase current in electrophoretic techniques, leading to excessive heat generation (joule heating) and unstable methods. It can also shield charged groups on proteins, potentially altering conformational equilibria, dynamic behavior, and catalytic properties [25] [3]. It is generally recommended to optimize buffer strength as a compromise between adequate capillary wall shielding and manageable current levels (typically below 100 μA in CE) [3].

Q4: What is meant by "chemical inertia" and why is it important? Chemical inertia, or non-reactivity, refers to the ideal that a buffer should not interact with the system components. In reality, many buffers have specific and non-specific interactions with proteins. They can induce changes in conformational equilibria, dynamic behavior, and catalytic activity [25]. Crucially, some buffers chelate metal ions essential for enzyme function. For instance, Tricine binds Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺, while Tris can form complexes with ions like Cu(II) and Zn(II) [25]. These interactions can confound kinetic results by directly inhibiting enzymes or altering the free concentration of critical cofactors.

Troubleshooting Common Buffer-Related Experimental Issues

Problem 1: Poor Reproducibility of Kinetic Data Between Experiments

| Potential Cause | Troubleshooting Action |

|---|---|

| Vague buffer preparation records [3] | Standardize and record the exact protocol: salt form used, final pH, acid/base used for adjustment and their concentrations, and final volume. |

| Inconsistent pH adjustment practice (e.g., overshooting and re-adjusting) [3] | Always adjust pH slowly with appropriately diluted acids/bases. If you overshoot significantly, discard and prepare a fresh batch. Do not repeatedly adjust pH up and down. |

| Diluting a pH-adjusted stock solution [3] | Prepare the buffer at the final working concentration and pH. Diluting a concentrated, pH-adjusted stock changes the final pH because the degree of ionization of the buffer shifts with dilution. |

| Measuring pH at the wrong temperature [3] | Always adjust the pH of the buffer after it has reached the temperature at which it will be used. pH is a temperature-dependent measurement. |

Problem 2: Unexpected Enzyme Inhibition or Altered Kinetics

| Potential Cause | Troubleshooting Action |

|---|---|

| Buffer-specific inhibition or interaction [25] [27] | Test enzyme activity in a panel of different buffers at the same pH. Universal buffers (UBs) composed of multiple agents like HEPES, MES, and sodium acetate can be used across a broad pH range to eliminate the variable of changing buffer identity [25]. |

| Chelation of essential metal ions [25] [27] | Consult metal binding tables and switch to a non-chelating buffer. For example, replace Tricine (binds Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺) with HEPES or Tris, which have negligible binding for these ions under standard conditions [25]. |

| Interaction with the substrate or cofactor [27] | Use ITC or other biophysical methods to check for direct interactions between the buffer and substrates or metal cofactors. A change in the observed reaction enthalpy (ΔHobs) across different buffers can indicate complicating buffer interactions [27]. |

Problem 3: Buffer Crystallization or Precipitation in Storage or Assay

| Potential Cause | Troubleshooting Action |

|---|---|

| Salting out or solubility limit reached | Ensure the buffer is prepared correctly and that the salt form is appropriate for the final concentration. Avoid storing concentrated stocks at low temperatures. |

| Interaction with divalent cations [25] | A classic example is phosphate buffer forming insoluble complexes with Ca²⁺, leading to precipitation [25]. If your assay contains divalent cations, avoid phosphate and citrate buffers. Use buffers like HEPES or MOPS that are less likely to form precipitates. |

Essential Data Tables for Buffer Selection

| Buffer | pKa at 25°C | dpKa/°C (at pH 7.0) | Useful pH Range | Metal Binding Profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bis-Tris | 6.46 | N/A | 5.5 - 7.5 | Negligible |

| HEPES | 7.55 | -0.014 | 6.5 - 8.5 | Negligible |

| MES | 6.15 | -0.011 | 5.0 - 7.0 | Negligible |

| Sodium Acetate | 4.76 | Negligible | 3.5 - 5.5 | Negligible |

| Tricine | 8.05 | -0.021 | 7.0 - 9.0 | Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Mn²⁺, Cu²⁺ |

| Tris | 8.06 | -0.028 | 7.0 - 9.0 | Negligible for Ca²⁺/Mg²⁺; binds Cu(II), Ni(II), Zn(II) |

| Universal Buffer Code | Composition (20 mM each) | Effective Buffering Range | Key Features and Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| UB1 | Tricine, Bis-Tris, Sodium Acetate | pH 3.0 – 9.0 | Broad range. Not compatible with essential Ca²⁺ or Mg²⁺ due to Tricine. |

| UB2 | Tris, Bis-Tris, Sodium Acetate | pH 3.5 – 9.2 | Broad range. Negligible interaction with common biological divalent cations (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺). |

| UB3 / UB4 | HEPES, MES/Bis-Tris, Sodium Acetate | pH 2.0 – 8.2 | Very broad acidic to near-neutral range. Negligible interaction with Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺. |

Experimental Protocols

Purpose: To determine if a buffering agent directly interacts with your protein of interest, potentially confounding kinetic measurements.

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent/Solution |

|---|

| Purified protein solution (titrate) |

| Buffer solution of interest (titrant) |

| Matching dialysis buffer |

| ITC detergent cleaning solution |

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Dialyze the purified protein extensively against the buffer of interest to ensure exact matching of buffer components and pH. The buffer of interest will also be used as the titrant.

- Instrument Setup: Load the dialyzed protein solution into the sample cell of the ITC instrument. Load the buffer (titrant) into the syringe. Set the experimental temperature to your desired assay temperature.

- Titration Experiment: Program the ITC to perform a series of injections of the buffer into the protein solution. The experiment will measure the heat changes (either absorbed or released) upon each injection.

- Data Analysis:

- No Interaction: If the buffer is truly inert, the heat changes observed after each injection will be small and consistent, representing only the heat of dilution.

- Presence of Interaction: If the buffer binds to the protein, the thermogram will show significant, measurable heat effects. Integration of the peak areas will provide binding isotherms from which binding affinity (Kd), stoichiometry (n), and enthalpy (ΔH) can be derived.

Interpretation: A measurable binding event indicates that the buffer is not inert and could be influencing enzyme conformation and activity, suggesting an alternative buffer should be selected for kinetic studies [27].

Purpose: To create a single buffer system that maintains consistent chemical composition across a wide pH range, eliminating buffer-specific effects as a variable.

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent/Solution |

|---|

| Individual buffer components (e.g., HEPES, MES, Sodium Acetate) |

| 10M Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) |

| 5M Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) |

| Distilled or Deionized Water |

Methodology:

- Formulation Selection: Choose a universal buffer formulation from Table 2 based on your required pH range and cation compatibility (e.g., UB3 for pH 2-8 with Mg²⁺).

- Preparation: Dissolve the appropriate amounts of each individual, dry buffer powder in distilled water to achieve the desired final total buffer concentration (e.g., 60 mM total, with 20 mM from each component).

- Initial pH Adjustment: Set the initial pH of the universal buffer to a highly basic value (e.g., pH 11) using a concentrated solution of NaOH (e.g., 10M).

- Titration: For your kinetic assay, gradually adjust the pH of an aliquot of the universal buffer to the exact value required for your experiment by the step-wise addition of a concentrated acid (e.g., 5M HCl) with vigorous mixing. A nearly linear titration curve can be achieved across the entire effective range [25].

Interpretation: Using this single, composite buffer across all pH points in your study ensures that any observed changes in kinetic parameters are due to the pH change itself and not to a switch in buffer identity and its associated specific interactions [25].

Visual Workflows and Diagrams

Diagram: Systematic Buffer Selection and Validation Workflow

Diagram: Kinetic Data Problem Troubleshooting Map

This case study explores the intricate process of analyzing pH-dependent kinetic parameters in Glucose Dehydrogenase (GluDH) systems, framing the discussion within the critical context of buffer selection and appropriate control experiments. For researchers investigating enzyme kinetics, pH serves as a fundamental variable that can profoundly influence catalytic efficiency, substrate binding, and structural stability. Proper buffer selection is not merely a technical detail but a cornerstone of reliable kinetic analysis, as the choice of buffering agent can directly impact measured kinetic parameters through specific and nonspecific interactions with the enzyme system.

Key Concepts and Theoretical Framework

Glucose Dehydrogenase Systems

Glucose dehydrogenases (GluDH; EC 1.1.1.47) catalyze the oxidation of β-D-glucose to β-D-glucono-1,5-lactone with simultaneous reduction of the cofactor NAD(P)+ to NAD(P)H [28]. These enzymes offer several advantages for biotechnological applications, including high stability, inexpensive substrate, thermodynamically favorable reaction, and flexibility to regenerate both NADH and NADPH [28]. Understanding their pH-dependent behavior is crucial for optimizing their use in biocatalysis and biosensing applications.

GluDH enzymes from different biological sources exhibit distinct biochemical properties and cofactor preferences. For instance, GluDH from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (GluDH-BA) demonstrates significantly higher specific activity and stability at pH values above 6 compared to its counterpart from Bacillus subtilis (GluDH-BS) [28]. These source-dependent characteristics underscore the importance of careful kinetic characterization under varied pH conditions.

The pH-Kinetics Relationship

pH influences enzyme activity through multiple mechanisms:

- Ionization of catalytic residues: Protonation states of amino acid side chains in the active site can directly affect catalytic efficiency

- Substrate binding: pH can alter the charge state of substrate molecules, affecting their binding affinity

- Structural integrity: Extreme pH values may induce conformational changes or denaturation

- Cofactor binding: The binding of NAD(P)+/NAD(P)H can be pH-dependent

As observed in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase from Leuconostoc mesenteroides, pH variation can reveal catalytic groups involved in substrate binding and catalysis, such as carboxylic acids that accept protons during substrate oxidation [29].

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: How does buffer choice affect my kinetic parameters at different pH values?

Answer: Buffer choice significantly impacts kinetic parameters due to specific and nonspecific interactions with proteins. Different buffers can induce changes in conformational equilibria, dynamic behavior, and catalytic properties [25]. When studying pH effects, the common practice of switching buffers at different pH values makes it impossible to decouple buffer-induced changes from genuine pH effects [25].

Solution: Utilize universal buffer systems that maintain consistent composition across the entire pH range. We recommend the following formulations:

Table: Universal Buffer Formulations for pH-Dependent Kinetic Studies

| Buffer Name | Composition | Working pH Range | Metal Compatibility | Temperature Dependence (dpKa/°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UB1 | 20 mM Tricine, 20 mM Bis-Tris, 20 mM Sodium Acetate | 3.0–9.0 | Incompatible with Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Mn²⁺, Cu²⁺ | -0.015 |

| UB2 | 20 mM Tris-HCl, 20 mM Bis-Tris, 20 mM Sodium Acetate | 3.5–9.2 | Negligible metal binding | -0.020 |

| UB3 | 20 mM HEPES, 20 mM Bis-Tris, 20 mM Sodium Acetate | 2.0–8.2 | Negligible metal binding | -0.012 |

| UB4 | 20 mM HEPES, 20 mM MES, 20 mM Sodium Acetate | 2.0–8.2 | Negligible metal binding | -0.012 |

These universal buffers provide consistent buffering capacity across broad pH ranges without changing chemical composition, eliminating buffer-specific effects from your pH-kinetics analysis [25].

FAQ 2: Why do I observe inconsistent kinetic parameters when repeating pH studies?

Answer: Inconsistent parameters often stem from three common issues:

- Uncontrolled buffer effects: As discussed above, changing buffer systems across pH values introduces variability

- Insufficient stabilization of reaction products: Some reaction products, such as gluconic acid-δ-lactone in GluDH systems, are susceptible to nonenzymatic hydrolysis that varies with pH, affecting reverse reaction kinetics [29]

- Probe-related measurement errors: pH electrode issues including KCl depletion from reference electrolyte, poisoning of reference electrolyte, or cracked membranes can lead to erroneous pH measurements and inconsistent experimental conditions [30]

Solution: Implement the following quality control measures:

- Use universal buffer systems as described above

- Include appropriate controls for nonenzymatic substrate/product degradation

- Regularly calibrate and maintain pH electrodes, monitoring asymmetry potential (<±30 mV) and slope (>90%) [30]

- For GluDH systems, consider organic solvents to stabilize lactone products against hydrolysis when studying reverse reaction kinetics [29]

FAQ 3: How should I design my experiment to obtain reliable pH-kinetic parameters?

Answer: Optimal experimental design requires careful planning of both temperature levels and sampling intervals. For first-order kinetic studies, Monte Carlo analysis has demonstrated that specific sampling schemes minimize variation in derived parameters [31].

Solution: Follow this experimental workflow for robust pH-kinetics:

FAQ 4: What specific issues affect GluDH kinetic studies at different pH values?

Answer: GluDH systems present unique challenges across the pH spectrum:

At acidic pH (pH < 6):

- Decreased stability for some GluDH variants (e.g., GluDH-BS) [28]

- Potential substrate inhibition effects

- Increased nonenzymatic glucose degradation

At alkaline pH (pH > 8):

- Ionization of key catalytic residues affects activity

- Possible lactone hydrolysis affecting reverse reaction measurements

- Structural instability for some enzyme forms

Solution: Characterize your specific GluDH variant comprehensively:

- Determine pH-activity profile using universal buffers

- Assess pH-stability through pre-incubation experiments

- For GluDH-BA, leverage its exceptional stability above pH 6 [28]

- Account for lactone hydrolysis in kinetic models, especially at alkaline pH [29]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table: Key Reagents for pH-Dependent GluDH Kinetic Studies

| Reagent/Buffer | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Universal Buffer Systems (UB2-UB4) | Maintain consistent buffering across pH range | Select based on metal compatibility requirements; UB2 recommended for divalent cation-containing systems |

| NAD(P)+/NAD(P)H | Cofactor for GluDH reactions | Monitor stability at different pH values; protect from light |

| β-D-glucose | Substrate for GluDH | Prepare fresh solutions to avoid mutarotation equilibrium shifts |

| Organic solvents (methanol, ethanol) | Stabilize lactone products | Use consistent concentrations across pH treatments; can affect enzyme activity |

| His-tag purification kits | Enzyme purification | Maintain consistent enzyme preparation across pH studies |

| protease inhibitors | Prevent proteolytic degradation during assays | Ensure compatibility with kinetic assays |

Advanced Methodologies: Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining pH-Kinetic Parameters for GluDH Systems

Materials:

- Purified GluDH enzyme (e.g., recombinant GluDH-BA [28])

- Selected universal buffer system (UB2 recommended for general use)

- NADP+ stock solution (10-50 mM in water)

- Glucose stock solution (100-500 mM in water)

- Spectrophotometer with temperature control

Procedure:

- Prepare universal buffer stocks at 5× final concentration across desired pH range (e.g., pH 5.0-9.0 in 0.5 unit increments)

- Dilute to 1× final concentration, verify pH, and adjust if necessary

- For each pH condition, prepare reaction mixtures containing:

- Universal buffer (final concentration: 60 mM total buffer components)

- NADP+ (varying concentrations, typically 0.01-0.5 mM)

- Glucose (saturating concentration, typically 10-100 mM)

- Pre-incubate reaction mixtures at assay temperature (e.g., 30°C) for 5 minutes

- Initiate reactions by adding enzyme (final concentration 0.1-1 μg/mL)

- Monitor NADPH production at 340 nm for 2-10 minutes

- Calculate initial velocities from linear portion of progress curves

- Fit data to appropriate kinetic models (Michaelis-Menten, substrate inhibition, etc.)

Data Analysis:

- Plot Vmax and kcat/KM versus pH to identify catalytic pKa values

- Fit pH-rate profiles to appropriate models to extract microscopic pKa values

- Compare ionization constants with potential catalytic residues

Protocol 2: Assessing pH Stability of GluDH Variants

Materials:

- Purified GluDH enzymes (different variants for comparison)

- Universal buffer system (UB3 recommended for broader acidic range)

- Standard assay reagents

Procedure:

- Prepare enzyme solutions (0.1-0.5 mg/mL) in universal buffers across pH range

- Incubate at experimental temperature for predetermined time intervals

- Remove aliquots at various time points

- Dilute into standard assay conditions (pH optimum)

- Measure residual activity

- Calculate half-lives at each pH

- Plot stability-pH profile to identify optimal stability conditions

Data Analysis and Interpretation Framework

Quantitative Analysis of pH-Kinetic Data

Table: Example pH-Kinetic Parameters for GluDH Variants

| Enzyme Source | Parameter | pH 6.0 | pH 7.0 | pH 8.0 | pH 9.0 | Catalytic pKa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. amyloliquefaciens | kcat (s⁻¹) | 45.2 ± 3.1 | 68.5 ± 4.2 | 72.1 ± 3.8 | 65.3 ± 4.5 | 6.3 ± 0.2 (acidic) 8.7 ± 0.3 (basic) |

| B. amyloliquefaciens | KM (mM glucose) | 8.5 ± 0.7 | 5.5 ± 0.4 | 5.8 ± 0.5 | 7.2 ± 0.6 | 6.8 ± 0.3 (acidic) |

| B. amyloliquefaciens | kcat/KM (mM⁻¹s⁻¹) | 5.3 ± 0.5 | 12.5 ± 1.1 | 12.4 ± 1.2 | 9.1 ± 0.9 | - |

| B. subtilis | kcat (s⁻¹) | 12.1 ± 1.8 | 14.5 ± 2.1 | 15.2 ± 2.0 | 9.8 ± 1.5 | 8.5 ± 0.4 (basic) |

| L. mesenteroides (G6PDH) | kcat (s⁻¹) | - | - | - | - | 8.7 ± 0.2 [29] |

Note: Data adapted from referenced studies [29] [28] and representative values.

Interpreting pH-Kinetic Profiles

The pH dependence of enzyme kinetics provides insight into catalytic mechanisms:

As observed in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, the ionization of a group with pKa 8.7 increased maximum velocity due to a pH-dependent product release step that was no longer rate-limiting at high pH [29]. Similar analyses can be applied to GluDH systems to identify key catalytic residues.

Through this case study, we emphasize that rigorous analysis of pH-dependent kinetic parameters requires meticulous attention to buffer selection and experimental design. The use of universal buffer systems eliminates a significant source of variability in pH-kinetics studies, while proper experimental design and troubleshooting approaches ensure reliable parameter estimation. For GluDH systems specifically, researchers must account for enzyme-specific characteristics such as the exceptional alkaline stability of GluDH-BA and the potential for lactone hydrolysis affecting kinetic measurements. By implementing the methodologies and troubleshooting guides presented herein, researchers can obtain robust, reproducible pH-kinetic parameters that provide genuine insight into enzymatic mechanisms rather than artifacts of experimental design.

Methodology in Action: Implementing Buffers in Kinetic and Bioprocessing Workflows

Designing a Buffer Screening Experiment for Early-Stage Formulation

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and frequently asked questions (FAQs) for researchers designing buffer screening experiments, with a specific focus on their role in kinetic studies research.

Core Concepts & FAQs

What is the primary goal of a pre-formulation buffer screening?

The primary goal is to identify optimal buffer conditions that maintain the solubility and biological activity of a new biologic drug candidate. This involves a systematic evaluation of parameters like pH, salt concentration, and excipients to prevent protein aggregation or denaturation, thereby de-risking the entire drug development process [32].

How does buffer selection impact kinetic studies?

The buffer system is a critical experimental variable in kinetic studies. Its composition directly affects the stability of the molecules of interest, the integrity of the sensor surface in techniques like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), and the minimization of non-specific binding. Inconsistent buffer preparation can lead to poor reproducibility, baseline drift, and erroneous kinetic measurements, compromising the integrity of the binding data [3] [15].

What are the most common buffer systems used in early-stage formulation?

Common buffer salts and their typical pKa values include [32]:

- Acetate (pKa ~4.8)

- Citrate (pKa₃ ~6.04)

- Histidine (pKa ~6.01)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (often at pH 7.4)

- Tris (pKa ~8.1)

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Poor Reproducibility of Kinetic Data

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Inconsistent Buffer Preparation. Vague buffer descriptions in methods lead to irreproducible ionic strength and buffering capacity [3].

- Solution: Standardize and document buffer preparation exquisitely. Specify the exact salt form, the pH adjustment procedure (including the concentration of acid/base used), and ensure the pH is measured at the correct temperature and before the addition of other components like organic solvents [3].

- Cause 2: Non-Specific Binding (NSB) in SPR or other binding assays. NSB leads to unwanted signals that interfere with the specific interaction of interest [15].

- Solution: Optimize surface chemistry and use blocking agents (e.g., ethanolamine, BSA) to occupy active sites on the sensor chip. Incorporate additives like surfactants (e.g., Tween-20) in the running buffer and tune the flow conditions to minimize NSB [15].

Problem: Low Signal Intensity in Binding Assays

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Insufficient ligand density or poor immobilization efficiency [15].

- Solution: Optimize ligand immobilization density by performing titrations during surface preparation. For weak interactions, consider using sensor chips with enhanced sensitivity and ensure analyte concentrations are sufficient to generate a detectable signal without causing saturation [15].

Problem: High Material Costs During Extensive Screening

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Traditional screening methods are resource-intensive. [32]

- Solution: Employ high-throughput methods (e.g., 96-well format) and use instruments that provide high-resolution data with low sample consumption. Furthermore, consider the cost of buffer components during formulation; sometimes, a minimal sacrifice in stability for a significant cost reduction (e.g., using PBS over HEPES) is economically beneficial at scale [32].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Standard Protocol for a Multi-Parameter Buffer Screen

This protocol is designed for a 96-well format, allowing for the simultaneous testing of multiple conditions [33].

Key Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent Type | Examples | Function in Formulation |

|---|---|---|

| Buffering Agents | Histidine, Citrate, Phosphate, Tris | Maintain formulation pH within a specific range [32]. |

| Salts | Sodium Chloride (NaCl), Potassium Chloride (KCl) | Improve protein solubility and maintain ionic strength [32]. |

| Surfactants | Polysorbate 20, Polysorbate 80 | Reduce surface-induced aggregation and prevent protein denaturation [32]. |

| Stabilizers | Sucrose, Trehalose, Sorbitol, Amino Acids (e.g., Arginine) | Stabilize protein structure against thermal and mechanical stress [32]. |

Workflow:

- Define Factor Space: Identify the factors and their levels (e.g., pH: 5, 6, 7, 8; Buffer System: Acetate, Histidine, Phosphate; Surfactant: A, B, None; Sugar: A, B, None) [33].

- Design of Experiment (DoE): Use a statistical DoE approach (e.g., a screening design or custom design in software like JMP) to generate a set of experimental conditions that efficiently explores the multi-dimensional parameter space. Include center points and replicates to assess variability and model curvature [33].

- Buffer Preparation: Precisely prepare buffers according to the DoE layout. Record all details, including the exact salts used and the pH adjustment procedure [3].

- Sample Incubation: Dispense the drug candidate into each buffer condition.

- Stability Analysis: Use stability-indicating assays (e.g., analytics that monitor aggregation, conformational stability, and activity) to evaluate each formulation after incubation under relevant stress conditions (e.g., thermal stress, freeze-thaw) [32].

The diagram below visualizes the logical workflow and the key parameters involved in designing a buffer screening experiment.

Protocol for SPR Kinetic Analysis Using Single-Cycle Kinetics (SCK)

This protocol is useful for studying interactions where surface regeneration is difficult [34].

Workflow:

- Ligand Immobilization: Immobilize the ligand on an appropriate sensor chip (e.g., CM5 for covalent coupling, NTA for His-tagged proteins).

- Baseline Establishment: Pass running buffer over the sensor surface to establish a stable baseline.

- Analyte Injection (Single-Cycle): Inject a sequence of increasing analyte concentrations over the ligand surface without regeneration between injections. A typical sequence might be five injections of the same analyte at 1x, 2x, 4x, 8x, and 16x concentration.

- Dissociation: After the final injection, allow a single, long dissociation phase by resuming buffer flow.

- Data Analysis: Fit the resulting sensorgram to appropriate binding models (e.g., 1:1 Langmuir) to extract the association rate constant (kon) and dissociation rate constant (koff) [34].

The diagram below contrasts the steps involved in Multi-Cycle Kinetics (MCK) and Single-Cycle Kinetics (SCK) experiments in SPR.

Advanced Methodologies

The Role of Computational Screening

A physics-based, coarse-grained molecular simulation protocol has been developed to complement experimental buffer screening. This protocol uses medicinal chemistry interactions (electrostatics, hydrophobics, hydrogen bonding, etc.) to analyze protein behavior under different buffer conditions, pH, and ionic strength. Combined with protein-folding AI algorithms, it creates a powerful digital framework for predicting optimal formulation conditions, reducing the need for extensive physical testing [35].

Integrating DoE with High-Throughput Analytics

Modern buffer optimization leverages statistical Design of Experiment (DoE) to systematically explore the complex interplay of multiple factors. As highlighted in a community discussion, a typical screen might investigate different pH ranges (set by different buffer systems), surfactants, sugars, salt concentrations, and drug concentrations. A well-designed DoE, analyzed using tools like JMP's Custom Design platform, allows researchers to model the effect of each component and their interactions on stability, leading to a more efficient and data-driven identification of the optimal formulation [33].

Buffer Applications in Enzyme Kinetic Assays and Microreactor Systems

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is buffer selection so critical in enzyme kinetic assays? Buffer selection is paramount because enzymes are highly sensitive to their chemical environment. An inappropriate buffer can lead to inaccurate kinetic data, poor reproducibility, and enzyme inactivation. Buffers maintain the pH at the enzyme's optimal range, which is essential for preserving its active conformation and catalytic activity. Furthermore, buffers help maintain consistent ionic strength, which can influence enzyme-substrate interactions. Some buffer components can also chelate metal ions or directly interfere with the enzyme or detection method, leading to experimental artifacts [36] [37].

Q2: My enzyme kinetic data is inconsistent between replicates. Could my buffer be the cause? Yes, inconsistent data is a classic symptom of buffer-related issues. Common causes include:

- Insufficient Buffer Capacity: The buffer may not be able to maintain pH throughout the reaction, especially if protons are consumed or released.

- Human Error in Manual Preparation: Slight variations in weighing salts or adjusting pH manually can lead to differences in ionic strength and buffering capacity between batches.

- Unidentified Inhibitory Contaminants: Impurities in buffer salts can act as low-level enzyme inhibitors. To resolve this, consider using a buffer with higher capacity (e.g., phosphate for near-physiological pH), switching to an automated buffer preparation system for consistency, and using high-purity, cell culture-grade reagents [38] [37].

Q3: What are the key differences between manual and automated buffer preparation for microreactor systems? The key differences lie in precision, reproducibility, and efficiency, which are summarized in the table below.

Table: Comparison of Manual vs. Automated Buffer Preparation

| Feature | Manual Preparation | Automated Preparation Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Precision & Accuracy | Prone to human error in weighing and pH adjustment | High precision and accuracy via inline sensors and dispensing [38] |

| Reproducibility | Lower; varies between users and batches | High repeatability; crucial for regulatory compliance (e.g., cGMP) [38] |

| Process Efficiency | Time-consuming and labor-intensive | Saves time and labor; enables just-in-time preparation [38] |

| Risk of Contamination | Higher due to open-container handling | Lower; closed systems reduce contamination risk [38] |

Q4: Which buffer is best for my kinetic assay? There is no single "best" buffer, as the choice depends on your enzyme's specific requirements and your experimental setup. However, the following guidelines apply:

- pKa and pH Range: The buffer's pKa should be within ±1 unit of your desired assay pH. For physiological pH (around 7.4), phosphate buffers (pKa ~7.2) and HEPES (pKa ~7.5) are excellent choices [37].

- Chemical Inertness: Use "Good's Buffers" (e.g., HEPES, MOPS, TRIS) for biochemical assays because they are zwitterionic, have minimal metal chelation, and do not interfere with biological reactions [37].

- Temperature Sensitivity: Be aware that the pKa of some buffers, like TRIS, is highly sensitive to temperature. Choose buffers with stable pKa across your experimental temperature range [37].

Troubleshooting Guide

Table: Common Buffer-Related Issues in Kinetic Assays and Microreactors

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions & Recommended Controls |

|---|---|---|

| Low or No Enzyme Activity | 1. Incorrect assay pH.2. Buffer components inhibit the enzyme.3. Co-factor chelation (e.g., by phosphate or citrate buffers). | 1. Check enzyme's optimal pH range and ensure buffer pKa is matched.2. Test enzyme activity in different buffer systems (e.g., compare HEPES vs. phosphate).3. Include control experiments with added metal ions or switch to a non-chelating buffer [37]. |

| High Background Signal | 1. Buffer impurities reacting with assay components.2. Auto-hydrolysis of substrate in buffer. | 1. Use high-purity reagents. Run a "no-enzyme" control to establish baseline signal.2. Pre-incubate substrate in buffer before starting the reaction with enzyme to measure non-enzymatic rate [39]. |

| Poor Reproducibility in Microreactor Performance | 1. Inconsistent buffer preparation.2. Precipitate formation in concentrated stock solutions.3. Buffer degradation over time. | 1. Implement automated buffer preparation systems to ensure consistency [38].2. Filter stocks before use and check for precipitation.3. Prepare fresh buffers regularly and document shelf-life. |

| Drifting Baseline in Continuous Assays | 1. Inadequate buffer capacity for the reaction.2. pH-sensitive fluorescence or absorbance of the product. | 1. Increase buffer concentration (e.g., from 50 mM to 100 mM) or switch to a buffer with higher capacity.2. Run a control to confirm the product's spectroscopic properties are stable in your chosen buffer/pH [39]. |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Optimizing a Cell-Free Protein Synthesis (CFPS) Reaction Buffer using Design of Experiments (DoE)

Objective: To systematically optimize a complex CFPS reaction buffer for maximum protein yield and robustness, moving beyond traditional one-factor-at-a-time approaches [36].

Background: CFPS systems are used for protein production and biosensor development. Their reaction buffers contain over 20 components (salts, energy sources, amino acids), and these components can interact in non-linear ways. A systematic approach is required to understand these interactions [36].

Methodology:

- Factor Selection: Identify key buffer components to optimize (e.g., Magnesium glutamate, Potassium glutamate, PEG-8000, nucleotides).

- Experimental Design: Use statistical software (e.g., JMP Pro) to generate a Definitive Screening Design (DSD) or a Response Surface Methodology (RSM) design. This creates a set of experiments that efficiently explores the multi-component design space [36].

- Response Monitoring: For each experimental run, monitor multiple kinetic responses, not just final yield:

- Peak Protein Yield (Endpoint measurement)

- Maximum Reaction Rate (Initial slope of the production curve)

- Reaction Longevity (How long the system remains active)

- Lag Time (Time before linear production begins) [36]

- Data Analysis and Modeling: Fit the experimental data to a statistical model to identify which factors and factor interactions significantly impact each response.

- Validation: Confirm the model's predictions by testing the newly optimized buffer formulation against the reference buffer across different batches of cell extract and with different target proteins [36].

Expected Outcome: This DoE approach led to the development of a novel CFPS reaction buffer that outperformed the reference by 400% and showed improved robustness across different lysate batches and E. coli strains [36].

Protocol 2: Enzyme Kinetic Assay using a Continuous Enzyme Kinetic Assay and ICEKAT Analysis

Objective: To determine the initial velocity of an enzyme-catalyzed reaction accurately and fit the data to a Michaelis-Menten model using the ICEKAT web tool [39].

Background: Continuous assays monitor the formation of product or disappearance of substrate over time. Accurate determination of the initial, linear rate is crucial for calculating kinetic parameters like ( Km ) and ( V{max} ) [39].

Methodology:

- Assay Setup: Perform a continuous enzyme kinetic assay in a 96-well microtiter plate, collecting time-course data (e.g., absorbance or fluorescence) at different substrate concentrations.

- Data Preparation: Arrange data in a spreadsheet with the first column as time and subsequent columns as the time-dependent readout for each substrate concentration.

- ICEKAT Analysis:

- Upload the data file to the ICEKAT web interface .

- Select the appropriate analysis model (e.g., Michaelis-Menten).

- Choose a fitting mode (e.g., "Maximize Slope Magnitude" or "Schnell-Mendoza").

- Manually adjust the time range for linear fitting if necessary to ensure the most linear portion of the data is used, which helps avoid artifacts.

- Optionally, subtract a blank sample's slope [39].

- Parameter Extraction: ICEKAT will automatically calculate initial rates (slopes) for each substrate concentration and fit them to the Michaelis-Menten equation, providing ( Km ) and ( V{max} ) values with propagated errors [39].

Critical Control: Always include a "no-enzyme" control to account for any non-enzymatic substrate breakdown. Visually inspect the residual plot from ICEKAT to ensure a random distribution, indicating a good fit [39].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Reagents for Enzyme Kinetics and Microreactor Systems

| Reagent / Solution | Function & Importance | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| HEPES Buffer | A zwitterionic "Good's Buffer" with a pKa of 7.5, minimal metal ion binding, and excellent pH stability in physiological range. | Cell culture, enzyme assays, protein purification, and biochemical reactions requiring pH 7.2-8.2 [37]. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Provides isotonic, buffered conditions that mimic physiological states, crucial for maintaining biological activity. | Washing cells, diluting antibodies, and as a base solution for many biological assays [37]. |

| Automated Buffer Preparation System | Integrated systems that automatically mix, pH-adjust, and filter buffers, ensuring high precision and reproducibility while saving labor and time. | Large-scale biopharmaceutical manufacturing (e.g., for monoclonal antibodies), and high-throughput screening where consistency is critical [40] [38]. |

| Chromogenic Substrate (e.g., 4,6-ethyliden-G7-PNP) | A substrate that releases a colored product (e.g., p-nitrophenol, PNP) upon enzyme cleavage, allowing for continuous kinetic monitoring by absorbance at 405 nm. | Enzyme kinetic assays for hydrolases like α-amylase and other glycosidases; used in clinical diagnostics and enzyme characterization [39]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Enzyme Kinetic Assay and Buffer Optimization Workflow

Buffer Property Impact on Experimental Outcomes

Formulating high-concentration protein therapeutics (typically >50 mg/mL for monoclonal antibodies, and sometimes exceeding 150 mg/mL) is essential for enabling patient-friendly administration routes like subcutaneous injection [41] [42]. However, achieving stable, manufacturable, and deliverable high-concentration formulations presents significant scientific challenges. This technical support center addresses these challenges within the critical context of buffer selection and controlled experimental design, which are foundational for obtaining reproducible and predictive stability data in kinetic studies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why does viscosity increase so dramatically in high-concentration protein formulations? Viscosity increases exponentially, not linearly, with rising protein concentration due to molecular crowding and increased protein-protein interactions [42]. At high concentrations, molecules are packed densely, leading to substantial molecular interactions that would be negligible at lower concentrations, resulting in this exponential rise [41].

2. How does buffer selection impact the stability of my high-concentration therapeutic? The buffer system is critical for maintaining pH, which affects protein ionization, conformational stability, and colloidal interactions [3] [41]. An ineffective buffer can lead to pH shifts, especially during processes like ultrafiltration/diafiltration (UF/DF) due to the Gibbs-Donnan effect, potentially triggering aggregation or precipitation [41] [42].

3. Can I predict long-term stability from short-term accelerated studies? Yes, using kinetic modeling. Recent advances demonstrate that long-term stability, including for aggregates, can be predicted from short-term data using first-order kinetic models combined with the Arrhenius equation [43]. The key is designing stability studies where a single degradation pathway, relevant to storage conditions, is active across all temperature conditions [43].

4. What are the critical quality attributes to monitor for high-concentration formulations? Key attributes include:

- Aggregates and High Molecular Weight Species: Monitored by Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC-HPLC) [43].

- Viscosity: Affects manufacturability and injectability [41] [42].

- Opalescence and Phase Separation: Indicators of colloidal instability [44] [42].

- Subvisible and Visible Particles [44].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: High Viscosity

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High injection force, difficult to filter or manufacture. | High protein concentration leading to molecular crowding and self-association [41] [42]. | Optimize formulation excipients (e.g., amino acids like Histidine, salts) to reduce viscosity [41]. |

| Unfavorable protein-protein interactions at a specific pH and buffer ionic strength [3]. | Screen different buffer types, pH, and ionic strength to find conditions that minimize interactions [3] [45]. | |

| Non-Newtonian flow behavior under high shear rates [42]. | Consider sequence engineering to introduce single point mutations that reduce self-association [46]. |

Problem 2: Protein Aggregation

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Increase in soluble aggregates or particles during storage. | Partially unfolded proteins interacting at high concentrations [41]. | Optimize pH and buffer composition to maximize conformational stability [41]. Include surfactants (e.g., polysorbates) to stabilize interfaces [41]. |

| Agitation or interaction with interfaces (e.g., silicone oil in pre-filled syringes) [44] [42]. | Evaluate and mitigate silicone oil interaction, or consider silicone-free syringe systems [46]. | |

| Instability during frozen storage of Drug Substance (cryoconcentration) [44]. | Carefully control freezing rates and excipient composition (e.g., sucrose/trehalose to amorphous matrix ratio) to avoid cryoconcentration [44]. |

Problem 3: Opalescence and Phase Separation

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Solution appears cloudy or milky; liquid phases separate. | Reaching the limit of colloidal solubility, where protein-protein repulsive forces are insufficient [41] [42]. | Modify buffer conditions to increase protein colloidal stability. Use excipient screening with tools like PEG-based solubility assays to identify optimal conditions [41]. |

| High protein concentration exacerbating weak attractive interactions [42]. | Dilution may temporarily resolve opalescence but is not a product solution. Reformulate to address the underlying colloidal instability [42]. |

Problem 4: Unexpected pH Shifts During Manufacturing

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Final drug product pH is different from the diafiltration buffer pH. | Gibbs-Donnan effect during UF/DF, which causes an imbalance of diffusible ions (e.g., H+) across the membrane [41] [42]. | Conduct UF/DF feasibility studies to fine-tune the diafiltration buffer composition and account for this effect [41]. |

| Volume-exclusion effects in highly concentrated protein solutions [41]. | Design and optimize the buffer system with the final high-concentration environment in mind, not just the dilute starting solution [41]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Formulation Feasibility and Viscosity Assessment

Purpose: To determine the maximum achievable concentration and assess viscosity implications [41] [42].

Materials:

- Tangential Flow Filtration (TFF) system

- Viscometer or rheometer

- Formulation buffer candidates

Method:

- Concentration Gate Check: Concentrate the protein solution using TFF towards the target concentration [41].

- Viscosity Measurement: Measure the dynamic viscosity at the target concentration. Note the exponential relationship; small concentration increases can cause large viscosity jumps [42].

- Syringeability Test: For drug products, measure the injection force required to expel the solution through a narrow-gauge needle using a force gauge to ensure it is acceptable (typically <25 N) [42].

- Analysis: If viscosity is too high or concentration cannot be reached, proceed to excipient and buffer screening.

This workflow helps determine if the target formulation is feasible and guides subsequent optimization steps.

Protocol 2: Accelerated Stability and Kinetic Modeling for Aggregates

Purpose: To predict long-term aggregation levels using short-term stability data [43].

Materials:

- Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC-HPLC) system

- Stability chambers set at multiple temperatures (e.g., 5°C, 25°C, 40°C)

- Analytical software for kinetic modeling

Method:

- Study Design: Place the formulated drug product in stability chambers at at least three different temperatures. Ensure the dominant degradation mechanism is the same across temperatures [43].

- Sampling: Pull samples at predefined intervals (e.g., 0, 1, 3, 6 months) and analyze for aggregates using SEC-HPLC [43].

- Data Fitting: Fit the aggregate formation data to a first-order kinetic model. The rate constant (k) for aggregation at each temperature is determined [43].

- Arrhenius Plot: Use the Arrhenius equation to plot ln(k) against 1/T (absolute temperature). The linear relationship allows extrapolation of the rate constant (k) to the desired storage temperature (e.g., 5°C) [43].

- Prediction: Use the extrapolated k to predict the level of aggregates over the intended shelf-life [43].

This model uses elevated temperature data to predict long-term stability behavior at recommended storage conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in High-Concentration Formulation |

|---|---|

| Amino Acid Buffers (e.g., Histidine) | Provide buffering capacity to maintain specific pH, crucial for protein stability and solubility. Histidine is common in commercial antibody formulations [46] [45]. |

| Sugars (e.g., Trehalose, Sucrose) | Act as stabilizers by increasing the solution's viscosity and, in frozen states, forming an amorphous matrix to protect against denaturation and aggregation [44] [46]. |

| Surfactants (e.g., Polysorbate 80/20) | Minimize aggregation and surface-induced denaturation at interfaces (air-liquid, ice-liquid, solid-liquid) generated during shipping, mixing, and filling [41]. |

| Amino Acids (e.g., Arginine, Glycine) | Act as viscosity-lowering excipients and can improve colloidal stability by modulating protein-protein interactions [46]. |

| Antioxidants (e.g., Methionine) | Protect the protein from oxidation by reacting with and consuming reactive oxygen species [46]. |

Leveraging Buffers in Continuous-Flow Bioprocessing and Microreactors

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is buffer selection particularly critical in continuous-flow bioprocessing compared to traditional batch systems?