X-Ray Diffraction in Pharmaceutical Development: A Comprehensive Guide to Phase Structure and Nucleation Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive overview of X-ray diffraction (XRD) techniques for analyzing phase structure and nucleation in pharmaceutical development.

X-Ray Diffraction in Pharmaceutical Development: A Comprehensive Guide to Phase Structure and Nucleation Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of X-ray diffraction (XRD) techniques for analyzing phase structure and nucleation in pharmaceutical development. It covers foundational principles, including Bragg's Law and the unique 'fingerprint' nature of diffraction patterns for crystalline materials. The article details methodological applications of single-crystal and powder XRD (PXRD) in drug discovery, from identifying polymorphs and co-crystals to quantifying amorphous content. It addresses key troubleshooting challenges and explores optimization strategies leveraging artificial intelligence and machine learning, including novel approaches like the pair distribution function (PDF) for amorphous solid dispersions. Finally, it examines validation and comparative techniques, emphasizing regulatory compliance and the integration of XRD with complementary methods like Raman spectroscopy for robust solid-form analysis.

The Core Principles of X-Ray Diffraction for Crystalline Material Analysis

Bragg's Law, formulated by William Lawrence Bragg in 1913, is the fundamental principle that governs X-ray diffraction (XRD) and provides unparalleled insights into the atomic and molecular structure of crystalline materials [1]. This simple yet powerful equation allows scientists to decipher the atomic architecture of materials by measuring the angles and intensities of diffracted X-rays. The technique has revolutionized our understanding of materials across multiple disciplines, from determining the structure of DNA to developing advanced materials for electronics, energy storage, and pharmaceutical applications [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals, XRD provides crucial information for drug polymorphism analysis, protein crystallization studies, and characterizing active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), making it an indispensable tool in modern scientific research and development [2] [3] [4].

Theoretical Foundation: Demystifying Bragg's Law

The Core Principle and Its Mathematical Formulation

At its heart, Bragg's Law describes the condition under which X-rays scattered from parallel planes of atoms in a crystal lattice will constructively interfere to produce a detectable diffraction peak [1]. The mathematical expression of this law is:

nλ = 2d sinθ

Where:

- n = order of diffraction (an integer: 1, 2, 3...)

- λ = wavelength of the incident X-ray radiation (typically 1.5418 Å for copper Kα radiation)

- d = interplanar spacing, representing the perpendicular distance between parallel crystal planes

- θ = Bragg angle, defined as the angle between the incident X-ray beam and the crystal plane [1]

This relationship is visually represented in the following diagram, which illustrates the fundamental geometry of X-ray diffraction:

The diagram above illustrates the fundamental geometry of X-ray diffraction. Constructive interference occurs when the path difference between X-rays scattered from parallel crystal planes (shown as green lines) equals an integer multiple of the X-ray wavelength. This condition is mathematically expressed by Bragg's Law, which connects the measurable diffraction angle (θ) to the atomic-scale d-spacing of the crystal.

Practical Applications of Bragg's Law in Modern Research

Bragg's Law enables several critical analytical capabilities in materials characterization:

- Determining d-spacing: By measuring the diffraction angle θ, researchers can calculate distances between crystal planes, which is essential for understanding crystal structures [1].

- Lattice parameter determination: Measuring multiple diffraction peaks allows for precise calculation of unit cell dimensions, enabling detection of subtle structural changes due to composition, temperature, or pressure variations [1].

- Residual stress analysis: Tracking changes in d-spacing under mechanical stress reveals strain and residual stress in materials, crucial for structural integrity assessment [5].

- Phase transformation studies: Observing how d-spacing shifts during thermal or chemical treatment provides insights into phase transformations in pharmaceuticals, alloys, and functional materials [1].

The revolutionary power of Bragg's Law was famously demonstrated in the determination of DNA's double helix structure. Rosalind Franklin's XRD work provided quantitative data that Watson and Crick used to propose their DNA model. Her analysis of "Photo 51" revealed the 3.4 Ã… spacing between consecutive base pairs, the 34 Ã… helical repeat distance for one complete turn, and the 20 Ã… helix diameter - all measured directly from the diffraction pattern [1].

Experimental Methodologies: From Principle to Practice

XRD Instrumentation and Measurement Techniques

Modern X-ray diffractometers consist of several essential components working in coordination to apply Bragg's Law for materials characterization [1]:

- X-ray source: Generates monochromatic X-rays through electron bombardment of a metal target, most commonly copper with characteristic Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å)

- Incident beam optics: Conditions the X-ray beam using Soller slits for controlling beam divergence, monochromators for wavelength selection, and focusing mirrors for beam concentration

- Sample stage: Holds the specimen and allows precise positioning and rotation during measurement, providing accurate angular positioning that may include environmental controls

- Detector system: Employs position-sensitive detectors or area detectors that simultaneously collect data over a range of angles, significantly reducing measurement time while maintaining high resolution

- Goniometer: A precision mechanical system controlling angular relationships between X-ray source, sample, and detector, achieving angular accuracy better than 0.001° [1]

The instrument operates by directing X-rays at the sample while rotating both sample and detector according to θ-2θ geometry, ensuring the detector captures diffracted beams at the correct angle for constructive interference as defined by Bragg's Law [1].

Key XRD Methodologies for Different Sample Types

Different experimental approaches have been developed to address various material forms and research questions:

- Single-crystal XRD: Used when a single crystal is available, producing a pattern of defined isolated peaks on the detector plane. This method provides the most detailed structural information, allowing determination of complete unit cell geometry and atomic positions [1] [6].

- Powder XRD: Employed for polycrystalline materials, where random orientation of microcrystals produces symmetrical Debye rings. The detector scans perpendicular to these rings to gather peak intensities, providing information on phase composition, crystallite size, and preferred orientation [1].

- Thin-film and grazing incidence XRD (GIXRD): Specialized methods for analyzing coatings, thin films, and surface layers with nanometric precision, revealing crystal orientation, internal stress, and coating quality [5].

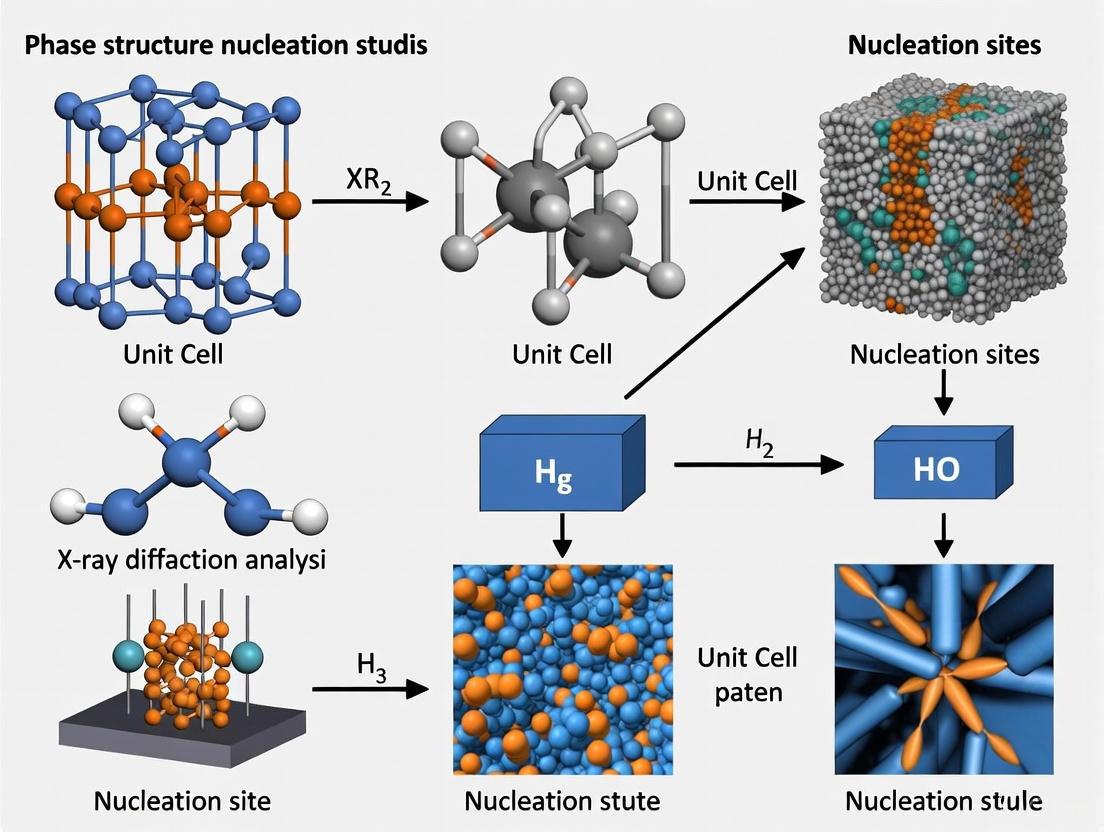

The following workflow illustrates how these different methodologies are applied in materials characterization research:

Comparative Analysis of Quantitative XRD Methods

Methodologies and Performance Metrics

Several quantitative analysis methods have been developed to extract precise mineralogical and structural information from XRD patterns, each with distinct advantages, limitations, and optimal application domains. A systematic comparative study evaluated three primary quantitative methods: Reference Intensity Ratio (RIR), Rietveld, and Full Pattern Summation (FPS) [7]. The study used artificially mixed samples containing seven high-purity minerals (quartz, albite, calcite, dolomite, halite, montmorillonite, and kaolinite) to represent mineral assemblages in natural sediments. All mixture samples were ground to <45 μm (325 mesh) to minimize micro-absorption corrections and preferred orientation effects [7].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Quantitative XRD Methods

| Method | Principle | Required Input | Software Examples | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Intensity Ratio (RIR) | Uses intensity of individual peaks with RIR values as reflection of mineral content [7] | Single peak intensity, RIR values [7] | JADE 'easy quantitative' function [7] | Handy, rapid analysis; less complex samples [7] |

| Rietveld Method | Refinement between observed and calculated patterns using crystal structure database [7] | Crystal structure models, full pattern data [7] | HighScore, TOPAS, GSAS, BGMN, Maud [7] | Complex non-clay samples; detailed structural refinement [7] |

| Full Pattern Summation (FPS) | Summation of reference patterns from pure phases to match observed pattern [7] | Library of pure diffraction patterns [7] | FULLPAT, ROCKJOCK [7] | Clay-rich samples; sediments; complex mixtures [7] |

Quantitative Performance Assessment

The analytical accuracy of these methods was systematically evaluated using known proportions of artificial mixtures, with results assessed through absolute error (ΔAE), relative error (ΔRE), and root mean square error (RMSE) calculations. The study established that a reliable quantitative XRD method should have uncertainty less than ±50X−0.5 at the 95% confidence level, covering all errors during analysis including weighting errors, counting statistics, and instrument errors [7].

Table 2: Accuracy Comparison of Quantitative XRD Methods for Different Sample Types

| Method | Accuracy for Non-Clay Samples | Accuracy for Clay-Containing Samples | Limitations | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RIR Method | Moderate accuracy [7] | Significant accuracy degradation [7] | Lower analytical accuracy; limited for complex mixtures [7] | Simple implementation; rapid analysis [7] |

| Rietveld Method | High analytical accuracy [7] | Conventional software fails with disordered/unknown structures [7] | Struggles with disordered/unknown structures [7] | Comprehensive structural refinement; high precision for crystalline phases [7] |

| FPS Method | Good accuracy [7] | Wide applicability; more appropriate for sediments [7] | Requires comprehensive reference library [7] | Excellent for complex mixtures; handles disordered materials well [7] |

The research demonstrated that while all three methods show consistent analytical accuracy for mixtures free from clay minerals, significant differences emerge for clay-mineral-containing samples. The FPS method showed the widest applicability for sedimentary samples, while the Rietveld method excelled at quantifying complicated non-clay samples with high analytical accuracy [7].

Advanced Applications in Nucleation Studies and Drug Development

In Situ XRD for Real-Time Nucleation Mechanism Studies

Advanced XRD techniques now enable real-time investigation of nucleation and growth mechanisms under various synthesis conditions. Specialized reactors have been developed for in situ X-ray scattering studies of solvothermal reactions, capable of providing data with millisecond time resolution [8]. These systems utilize robust polyimide-coated fused quartz tubes that withstand pressures up to 250 bar and temperatures up to 723 K, allowing researchers to study reaction mechanisms under previously inaccessible conditions [8].

The high temporal resolution of these advanced XRD systems has revealed previously unobservable transient phases during nanoparticle formation. For instance, simultaneous in situ powder XRD and small-angle X-ray scattering studies have illuminated the formation mechanisms of various functional nanomaterials including WO₃, ZnWO₄, ZrO₂, and HfO₂ nanoparticles [8]. These studies often reveal complex crystallization pathways involving intermediate amorphous phases and metastable crystalline forms that would be impossible to capture using conventional ex situ methods.

XRD in Pharmaceutical Development and Biotechnology

XRD plays a critical role in pharmaceutical development, particularly in polymorphism analysis and protein crystallization studies:

- Polymorphism Analysis: The pharmaceutical industry accounts for 29% of total XRD applications globally, with approximately 71% of drug manufacturers employing XRD to ensure crystalline phase purity in drug formulations [4]. Different polymorphic forms can significantly affect a drug's efficacy, stability, and bioavailability [3].

- Protein Crystallography: Biotechnology companies represent 18% of the XRD market share, using the technology for protein crystallization and biopolymer structural studies [4]. Around 46% of research institutions in biotechnology depend on single-crystal XRD for enzyme structure determination [4].

- Microgravity Crystallization: Companies like Merck have utilized the International Space Station to grow protein crystals in microgravity, resulting in larger, more uniform crystals with fewer defects [2]. Merck's research with Keytruda showed that space-grown crystals offered improved viscosity and injectability compared to Earth-grown crystals, potentially enabling subcutaneous administration of this cancer treatment [2].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for XRD Studies in Materials and Pharmaceutical Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Mineral Standards (Quartz, Albite, Calcite, etc.) | Reference materials for quantitative analysis method development and validation [7] | Artificial mixture preparation for accuracy assessment [7] | Grain size <45 μm; homogenized for 30 minutes [7] |

| Polyimide-Coated Fused Quartz Tubes | Reactor cells for in situ solvothermal studies [8] | Real-time nucleation and growth studies under high P-T conditions [8] | Withstand 250 bar, 723 K; 0.7 mm inner diameter [8] |

| Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) | Subject of polymorphic form analysis and crystal structure determination [3] [4] | Drug formulation optimization; stability studies [4] | Multiple polymorph screening; humidity/temperature variation [4] |

| Protein Crystallization Reagents | Facilitate growth of high-quality protein crystals for structural biology [2] [4] | Drug target identification; protein-ligand interaction studies [4] | Microgravity conditions often improve crystal quality [2] |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of X-ray diffraction is undergoing significant transformation driven by technological advancements and evolving research needs:

- Artificial Intelligence Integration: Approximately 48% of manufacturers are incorporating AI modules for automated peak analysis, reducing manual errors by 31% [4]. AI-driven analytics have improved experiment turnaround times by 37% and have achieved 92% accuracy in polymorphism prediction in pharmaceutical applications [4].

- Miniaturization and Portability: Portable XRD analyzers have seen a 33% adoption increase in mineral exploration and a 31% rise in environmental monitoring applications since 2022 [4]. Compact benchtop systems have increased small laboratory penetration by 22% [4].

- Advanced Detector Technology: High-resolution detectors offering 40% faster data acquisition have been adopted by 55% of laboratories globally [4]. Improvements in X-ray detectors have enhanced resolution to 0.8 Ã… in 2025, allowing visualization of small-molecule and macromolecular structures with unprecedented detail [4].

- Hybrid Techniques and Multi-Method Approaches: There is growing integration of XRD with complementary techniques such as X-ray fluorescence (XRF) for comprehensive materials characterization [3]. While XRD analyzes crystallographic structure, XRF determines elemental composition, making the techniques highly complementary for complete material analysis [3].

According to market research, the global XRD market is projected to grow from USD 1155.19 million in 2025 to USD 1943.58 million by 2034, with a compound annual growth rate of 5.95% [4]. This growth is driven by increasing demand from materials science, nanotechnology, and pharmaceutical crystallography applications, which account for 69% of market growth [4].

Bragg's Law remains the foundational principle enabling X-ray diffraction's powerful capabilities in materials characterization and drug development. The comparative analysis of quantitative methods reveals that method selection should be guided by sample complexity and specific research objectives, with the Rietveld method offering superior performance for well-crystalline materials, while the FPS approach provides broader applicability for complex, clay-containing samples. As XRD technology continues to evolve with AI integration, miniaturization, and advanced detector systems, its applications in nucleation studies and pharmaceutical development will further expand, solidifying its position as an indispensable tool for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to understand and engineer materials at the atomic level.

How Crystals Act as Three-Dimensional Diffraction Gratings for X-Rays

The Fundamental Principle: Bragg's Law

In X-ray diffraction (XRD), the fundamental principle governing how crystals act as three-dimensional diffraction gratings is Bragg's Law [9] [10]. This law describes the condition for constructive interference of X-rays scattered by the periodic lattice of atoms in a crystal.

The relationship is mathematically expressed as: nλ = 2d sinθ Where:

- n is the order of the reflection (an integer)

- λ is the wavelength of the incident X-rays

- d is the spacing between consecutive atomic planes in the crystal

- θ is the angle between the incident X-ray beam and the scattering crystal planes [11] [10]

When a beam of monochromatic X-rays strikes a crystal, it interacts with the electrons of the atoms and is scattered in all directions. For most scattering directions, the waves cancel each other out through destructive interference. However, when the path difference between X-rays scattered from parallel planes of atoms is equal to an integer multiple of the X-ray wavelength, the waves undergo constructive interference, resulting in a strong diffracted beam that can be detected [9] [12]. This is directly analogous to the diffraction of visible light by a man-made optical grating, but with the key difference that the grating is a three-dimensional atomic lattice [13] [9].

Comparison of Primary X-Ray Diffraction Techniques

X-ray diffraction techniques can be broadly categorized by the type of sample analyzed. The table below compares the two primary methodologies.

| Technique | Sample Type | Key Applications | Key Outputs | General Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Crystal XRD (SCXRD) [10] [14] | A single, high-quality crystal (typically 50–300 µm) [14]. | - Determining precise atomic structure & bond angles [14].- New mineral identification [14].- Studying cation-anion coordination [14]. | - 3D electron density map.- Accurate atomic positions. | - Requires a robust, optically clear single crystal [14].- Data collection can be time-consuming (hours to days) [14].- Handling twinned crystals is difficult [14]. |

| Powder XRD (PXRD) [11] [10] | Finely ground polycrystalline or powdered material [11]. | - Phase identification of unknown crystalline materials [11] [10].- Determination of unit cell dimensions [11].- Measurement of sample purity [11]. | - Diffractogram (Intensity vs. 2θ plot).- Phase identification & quantification. | - Less effective for non-crystalline/amorphous materials [10].- Detection limit for mixed phases is ~2% [11].- Peak overlap can complicate analysis [11] [10]. |

Advanced and Emerging XRD Methodologies

Beyond the primary techniques, several advanced methods have been developed to address specific research needs.

| Technique | Description | Specialized Applications |

|---|---|---|

| High-Resolution XRD (HRXRD) [10] | A high-precision technique for materials with fine structural details. | - Studying strain, lattice mismatch, and defects in thin films and epitaxial layers, particularly in semiconductors [10]. |

| Grazing-Incidence XRD (GIXRD) [10] | The X-ray beam is directed at a very shallow angle to the sample surface. | - Analyzing the structure of thin films, surface layers, and nanomaterials where the surface structure differs from the bulk material [10]. |

| 3D X-Ray Diffraction (3DXRD/ HEDM) [15] | A rotating technique that collects diffraction patterns in 3D. | - Measuring volume, position, orientation, and elastic strain of thousands of grains in a polycrystalline material simultaneously (micromechanics studies) [15]. |

| Coherent X-ray Diffraction Imaging (CDI) [16] | Uses coherent X-rays and computational phase retrieval to image nanoscale samples. | - 3D strain imaging of crystalline nanoparticles without needing lenses [16]. |

Experimental Protocol: Phase Identification via Powder XRD

The following workflow details a standard methodology for identifying an unknown crystalline phase using Powder XRD, a ubiquitous application in materials science, geology, and pharmaceutical development [11].

Step 1: Sample Preparation The material is the first ground to a fine powder (typically less than 10 µm) to ensure a random orientation of crystallites and to minimize induced strain that can offset peak positions. The powder is then smeared uniformly onto a glass slide or packed into a sample holder to create a flat, random powder specimen [11].

Step 2: XRD Data Collection The prepared sample is placed in an X-ray diffractometer. A monochromatic X-ray beam (e.g., CuKα radiation, λ = 1.5418 Å) is generated, collimated, and directed at the sample. The sample and detector are rotated through a range of 2θ angles (e.g., from 5° to 70°). A diffraction peak is recorded whenever the geometry satisfies Bragg's Law for a specific set of lattice planes. The result is a diffractogram—a plot of X-ray intensity versus the diffraction angle (2θ) [11] [10].

Step 3: Data Analysis and Phase Identification The measured 2θ angles of the diffraction peaks are converted to d-spacings (the interplanar spacing, d in Bragg's Law) using the Bragg equation. The relative intensities (I/Iâ‚) and d-spacings of the three strongest peaks are then used as a "fingerprint" to search a standard reference database, such as the Powder Diffraction File (PDF) maintained by the International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDD). A successful match identifies the crystalline phase of the unknown material [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials for XRD

Successful X-ray diffraction analysis requires specific materials and instrumentation. The following table details key components of a standard XRD setup.

| Item | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| X-ray Tube | Generates the incident X-rays; common target materials include Copper (Cu) for powder/single-crystal and Molybdenum (Mo) for single-crystal studies [11] [14]. |

| Monochromator / Filter | Produces monochromatic X-rays by filtering out unwanted wavelengths (e.g., Kβ radiation), leaving a nearly pure Kα beam for the experiment [11]. |

| Goniometer | A high-precision instrument that rotates the sample and the detector through precise angles (θ and 2θ, respectively) to satisfy Bragg's Law for all possible lattice planes [11]. |

| Sample Holder | Holds the specimen in the X-ray beam. For powders, this is typically a glass slide or metal well; single crystals are mounted on thin glass fibers [11] [14]. |

| X-ray Detector | Measures the intensity and position of the diffracted X-rays. Modern systems use charge-coupled device (CCD) technology for rapid data collection [14]. |

| Reference Standards | A known standard material (e.g., NIST standard) may be added to a powder sample to correct for minor instrumental shifts in peak positions for accurate unit cell determination [11]. |

| Crystal Structure Database | Digital references like the Powder Diffraction File (PDF) or Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) are essential for phase identification and structure solution [11] [17]. |

| Zotarolimus | Zotarolimus |

| Rauvotetraphylline C | Rauvotetraphylline C, CAS:1422506-51-1, MF:C28H34N2O7, MW:510.6 g/mol |

The Logical Pathway from Diffraction to Structure

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental logical relationship between a crystal's atomic structure, the diffraction process it creates, and the resulting data that scientists analyze.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) stands as a powerful, non-destructive analytical technique that is indispensable in materials science, geology, and pharmaceutical development. It provides unparalleled insights into the atomic and molecular structure of crystalline materials by leveraging the unique 'fingerprint' that each crystal phase produces [1] [5]. This guide objectively compares the performance of traditional and emerging machine learning-based approaches to XRD phase identification, framing the discussion within the broader thesis of advancing materials research through automated and data-driven analysis.

The Foundational Principle: XRD as a Crystalline Fingerprint

At its core, XRD analysis is based on the elastic scattering of X-rays by the ordered atomic planes within a crystal lattice [1]. When a monochromatic X-ray beam strikes a crystalline sample, the scattered rays constructively interfere only at specific angles, defined by Bragg's Law (nλ = 2d sin θ), producing a characteristic diffraction pattern [1] [5].

This pattern serves as a unique identifier for every crystalline phase. The peak positions correlate with the unit cell dimensions and symmetry, while the peak intensities relate to the atomic arrangement within the crystal structure [1]. Consequently, by analyzing the position, intensity, and shape of diffraction peaks, researchers can decipher the fundamental properties of a material, from its phase composition to its microstructural characteristics [5].

Performance Comparison: Traditional vs. Modern XRD Phase Identification

The methodologies for interpreting these crystalline fingerprints have evolved significantly. The table below summarizes the core characteristics, performance, and optimal use cases for the primary approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of XRD Phase Identification Methodologies

| Feature | Database Search-Match | Unsupervised Optimization (e.g., AutoMapper) | Supervised Machine Learning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Pattern comparison against reference databases (e.g., ICDD, ICSD) [18] [19] | Minimizing a loss function integrating XRD fit, composition, and entropy [18] | Training models (e.g., CNN, MTL) on large datasets of labeled patterns [20] [21] |

| Automation Level | Low to Medium (requires expert input) | High (fully automated workflow) [18] | High (end-to-end automation) |

| Key Strength | High accuracy for known phases; well-established | Identifies solid solutions, texture; provides "chemically reasonable" solutions [18] | High speed and data efficiency; handles distorted patterns [20] |

| Primary Limitation | Struggles with complex mixtures, solid solutions, or novel phases | Requires integration of domain knowledge (crystallography, thermodynamics) [18] | Requires large, high-quality training datasets [21] |

| Data Requirement | Reference databases | Raw or preprocessed XRD patterns and composition data [18] | Large volumes of labeled experimental or simulated data [21] |

| Typical Application | Routine quality control, mineral identification [19] | Analysis of combinatorial libraries for materials discovery [18] | High-throughput screening, analysis of noisy/imperfect data [20] |

Experimental Protocols for XRD Phase Analysis

Protocol 1: Automated Phase Mapping in Combinatorial Libraries

This protocol, as implemented by tools like AutoMapper, is designed for high-throughput analysis of hundreds to thousands of compositionally varied samples [18].

- Candidate Phase Identification: Collect all relevant crystalline phases from inorganic databases (ICDD, ICSD). Filter entries by chemistry (e.g., oxides only) and remove thermodynamically unstable phases using first-principles calculated data [18].

- Data Preprocessing: Apply background removal to raw XRD data (e.g., using a rolling ball algorithm) and retain substrate peaks during analysis [18].

- Pattern Simulation: Simulate XRD patterns for candidate phases, accounting for specific instrument geometry and X-ray beam polarization (e.g., fully polarized for synchrotrons, unpolarized for lab sources) [18].

- Optimization-Based Solving: Use an encoder-decoder neural network structure to solve for phase fractions and peak shifts. The model minimizes a composite loss function (

L_total) that ensures:L_XRD: High-quality fitting of the reconstructed diffraction profile (similar to Rietveld refinement).L_comp: Consistency between reconstructed and measured cation composition.L_entropy: An entropy term to prevent overfitting [18].

- Iterative Refinement: Initiate the solving process with "easy" samples (containing one or two phases) to avoid local minima, then progress to complex, multi-phase samples at phase boundaries [18].

Protocol 2: Machine Learning for Distorted Micro-XRD Patterns

This protocol uses Multitask Learning (MTL) to analyze challenging data, such as patterns from hydrothermal fluids, with minimal preprocessing [20].

- Model Selection & Training: Train an MTL model with a convolutional neural network (CNN) backbone. The model is trained on a large dataset of XRD patterns, such as the SIMPOD database, which contains hundreds of thousands of simulated patterns from the Crystallography Open Database (COD) [21].

- Loss Function Optimization: Employ a tailored cross-entropy loss function to improve model performance and data efficiency [20].

- Pattern Analysis: Input raw or minimally preprocessed XRD patterns into the trained model. The MTL architecture allows the model to learn shared features across related tasks, enhancing its ability to identify phases even in highly distorted patterns where traditional methods fail [20].

Research Workflow and Logical Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making workflow a researcher follows when selecting and applying an XRD phase identification methodology.

Diagram 1: Methodology Selection Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful XRD phase identification relies on a suite of computational and data resources. The table below details key solutions and their functions in modern analysis.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for XRD Phase Identification

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICDD/PDF-2 Database [18] [5] | Reference Database | Definitive library of powder diffraction patterns for phase identification. | Qualitative analysis; search-match verification of known phases. |

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [18] | Reference Database | Repository of crystal structures used for simulating theoretical XRD patterns. | Candidate phase generation for automated solvers; fundamental research. |

| HighScore Plus Software [19] | Analysis Software | Performs peak search, pattern matching, and phase identification across multiple databases. | Routine and complex phase analysis in industrial and research labs. |

| SIMPOD Database [21] | Machine Learning Dataset | Public dataset of 467,861 simulated XRD patterns for training and benchmarking ML models. | Training generalizable models for crystal parameter prediction. |

| AutoMapper [18] | Automated Solver | Unsupervised optimization-based workflow for phase mapping combinatorial libraries. | High-throughput materials discovery, integrating domain knowledge. |

| Multitask Learning (MTL) Models [20] | Machine Learning Model | Deep learning architecture for phase identification in distorted patterns with minimal preprocessing. | Analyzing micro-XRD data from challenging environments (e.g., hydrothermal fluids). |

| Euonymine | Euonymine, CAS:33458-82-1, MF:C38H47NO18, MW:805.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| L-Lysine hydrate | L-Lysine hydrate, CAS:39665-12-8, MF:C6H16N2O3, MW:164.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The field of XRD phase identification is undergoing a significant transformation, moving from reliance on manual database search-matching toward increasingly automated and intelligent systems. Traditional methods remain the gold standard for well-defined phases, but modern optimization-based solvers and machine learning models are breaking new ground in analyzing complex mixtures, novel materials, and noisy data. The future of the field, as evidenced by current research trends, points toward greater integration of domain knowledge with data-driven AI, enhanced by large, open-source datasets and more efficient algorithms, ultimately accelerating the pace of materials discovery and characterization [18] [20] [21].

X-ray Diffraction (XRD) is a cornerstone analytical technique for investigating the atomic and molecular structure of crystalline materials, providing unparalleled insights into phase identification, crystal structure, and structural properties [1]. For researchers working in phase structure and nucleation studies, understanding the formation and growth of crystalline phases is fundamental to designing materials with tailored properties [22]. XRD techniques enable the precise characterization of these crystalline structures by leveraging Bragg's Law (nλ = 2d sin θ), where X-rays interact with crystal lattices to produce unique diffraction patterns that serve as fingerprints for material identification [23] [1]. Within this research context, two primary methodologies have emerged: Single Crystal X-ray Diffraction (SCXRD) and Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD). Each approach offers distinct capabilities and limitations, making technique selection critical for obtaining meaningful data in nucleation and growth dynamics studies [23] [24]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these techniques to help researchers select the optimal method for their specific analytical needs in material science, pharmaceuticals, and fundamental crystallization research.

Fundamental Principles: How SCXRD and PXRD Work

Core Mechanism of X-ray Diffraction

Both SCXRD and PXRD operate on the same fundamental principle: when monochromatic X-rays interact with a crystalline material, they are scattered by the electrons around atoms in the crystal lattice. Constructive interference occurs only when the path difference between X-rays scattered from parallel crystal planes equals an integer multiple of the X-ray wavelength, a condition described by Bragg's Law [1]. This constructive interference creates detectable diffraction patterns that reveal information about the material's atomic structure. The resulting diffraction pattern serves as a unique identifier for the material, allowing researchers to determine unit cell dimensions, atomic coordinates, and overall structural composition [23].

Technique-Specific Diffraction Phenomena

Despite sharing a common physical basis, SCXRD and PXRD differ significantly in their data collection and output due to sample characteristics. In SCXRD, a focused, monochromatic X-ray beam strikes a single crystal, producing a pattern of discrete, well-defined diffraction spots [23] [24]. Each spot corresponds to a specific set of atomic planes within the crystal lattice, and by systematically rotating the crystal and collecting diffraction intensities at different angles, a three-dimensional dataset is created that allows precise determination of the atomic structure [23].

In contrast, PXRD analyzes a large collection of randomly oriented microcrystals (crystallites). The interaction of X-rays with this powder produces a diffraction pattern characterized by concentric rings (Debye rings) rather than discrete spots [1]. The final data is presented as a plot of intensity versus diffraction angle (2θ), where peak positions correspond to specific lattice spacings [23]. Since all crystal orientations are sampled simultaneously, PXRD does not require complex crystal rotation but provides less detailed structural information than SCXRD.

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental differences in diffraction patterns and data output between these two techniques:

Technical Comparison: SCXRD vs. PXRD

Sample Requirements and Preparation Protocols

Single Crystal XRD (SCXRD):

- Sample Characteristics: Requires a high-quality single crystal with well-defined faces and minimal defects [23]. The crystal must be sufficiently large (typically ≥ 0.1 mm in one dimension) and well-ordered to allow collection of distinct diffraction spots [23] [25].

- Preparation Protocol: Suitable crystals are grown using methods such as slow evaporation, vapor diffusion, or melt crystallization [23]. For small molecules, simple recrystallization is usually the first step, requiring pure samples [25]. The crystal is mounted on a goniometer, often using a fiber optic or a loop of cryoprotective oil. Cryogenic cooling is frequently employed to reduce thermal motion and mitigate radiation damage [23].

- Material Quantity: Only one crystal is needed for analysis, containing approximately 0.051 mg of material for a 0.3 × 0.3 × 0.3 mm crystal [25]. However, more material is typically required for multiple crystallization experiments.

Powder XRD (PXRD):

- Sample Characteristics: Works with microcrystalline powder consisting of numerous randomly oriented crystallites [23]. The powder should be finely ground and homogenous, with particle sizes ideally less than 10 μm to minimize peak broadening [26].

- Preparation Protocol: Preparation involves simple grinding using ball-milling or manual grinding with a mortar and pestle [26]. The powder is then packed into a sample holder, often compacted for uniformity [23]. Careful preparation is essential as particle size, preferred orientation, and sample thickness can affect analytical accuracy.

- Material Quantity: Requires significantly more sample material than SCXRD, though specific quantities depend on instrument sensitivity and sample holder design [26].

Structural Information and Resolution Comparison

Table 1: Structural Information Capabilities of SCXRD vs. PXRD

| Information Type | Single Crystal XRD | Powder XRD |

|---|---|---|

| Atomic Coordinates | Direct determination with high precision [23] | Indirect refinement using computational methods [23] |

| Bond Lengths & Angles | Precise measurement (often better than 0.001 nm) [24] | Limited to unit cell parameters [23] |

| Crystal Structure Solution | Able to solve completely new structures [23] | Requires reference patterns or known structural models [23] [17] |

| Phase Identification | Possible but not optimal for mixtures [24] | Excellent for phase analysis of polycrystalline samples [24] |

| Crystallinity Measurement | Not applicable | Quantitative determination of degree of crystallinity [24] |

| Strain/Stress Analysis | Limited | Excellent for residual stress and strain analysis [24] |

Applications in Research and Industrial Contexts

Single Crystal XRD Applications:

- Molecular Chemistry: Determining three-dimensional arrangement of atoms in complex molecules [24]

- Pharmaceutical Research: Analysis of drug polymorphism and precise molecular structure determination [23]

- Materials Science: Characterization of novel functional compounds and catalysts [23]

- Orientation Determination: Critical for semiconductor materials and turbine blade single crystal metals [24]

Powder XRD Applications:

- Pharmaceutical Development: Identification of drug polymorphs and qualitative/quantitative phase analysis [23] [26]

- Materials Science: Study of crystallinity, phase transformations, and stress-strain behavior [23]

- Geology and Mineralogy: Mineral identification and composition analysis [26]

- Quality Control: Routine analysis in cement production, metallurgy, and chemical production [27]

Time Efficiency and Practical Considerations

Table 2: Practical Considerations for Technique Selection

| Factor | Single Crystal XRD | Powder XRD |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation Time | Hours to days (crystal growth) [23] | Minutes (grinding and packing) [23] |

| Data Collection Time | Several hours to days [23] | Minutes to a few hours [23] [24] |

| Data Analysis Complexity | High, requires specialized expertise [23] [24] | Moderate, more accessible to non-specialists [23] |

| Equipment Accessibility | Specialized instrumentation required [23] | Widely available in many laboratories [23] |

| Suitability for High-Throughput | Low | Excellent [23] |

| Sample Limitations | Requires high-quality single crystals [23] | Limited to crystalline materials [27] |

Experimental Protocols for Nucleation and Growth Studies

Sample Preparation Methodologies

SCXRD Crystal Growth Protocol:

- Purification: Begin with pure compound, as contaminants can inhibit crystal formation or reduce crystal quality [25].

- Solvent Selection: Choose appropriate solvent systems based on compound solubility. Common approaches use solvent pairs where the compound is soluble in one solvent but less soluble in a second miscible solvent [25].

- Nucleation Control: Prepare solutions at concentrations similar to those used for ¹H NMR experiments. Slow evaporation or vapor diffusion methods help control nucleation density [25].

- Crystal Growth: Allow slow concentration changes through evaporation or diffusion. The setup should be located away from vibrations and temperature fluctuations [25].

- Crystal Selection: Identify well-formed crystals with smooth faces and minimal defects. Ideal crystal size is approximately 0.3 mm in each dimension [25].

PXRD Sample Preparation Protocol:

- Grinding: Use mortar and pestle or ball mill to reduce particle size to <10 μm [26].

- Homogenization: Ensure representative sampling of the bulk material.

- Packing: Load powder into sample holder and compact to ensure uniform density and minimize preferred orientation effects [23].

- Surface Preparation: Smooth the sample surface to be level with the holder rim to minimize surface topography effects.

Data Collection Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflows for both SCXRD and PXRD analysis, from sample preparation to final structure determination:

Advanced Analysis Techniques

Rietveld Refinement for PXRD: This powerful method enables precise determination of crystal structures from powder diffraction data by minimizing the difference between observed and calculated diffraction patterns [23]. The process involves refining structural parameters (atomic positions, thermal parameters, site occupancies) and instrumental parameters against the entire diffraction pattern rather than individual peaks [17]. For complex materials where reference patterns are unavailable, advanced computational approaches like evolutionary algorithms and crystal morphing (Evolv&Morph) can create crystal structures that reproduce target XRD patterns without database dependency [17].

Deep Learning Approaches: Recent advances in machine learning have enabled end-to-end structure determination from powder diffraction data. CrystalNet, a variational deep neural network, can estimate electron density in a unit cell directly from XRD patterns and partial chemical composition information, achieving up to 93.4% similarity with ground truth structures for cubic and trigonal crystal systems [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for XRD Studies

| Item | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Solvents | Crystal growth via slow evaporation, vapor diffusion, or cooling crystallization [25] | SCXRD: Solvent selection critical for growing high-quality single crystals |

| Mortar and Pestle / Ball Mill | Particle size reduction and homogenization of powder samples [26] | PXRD: Preparation of fine powders with uniform particle size distribution |

| Sample Holders | Mounting and positioning samples in the X-ray beam path [23] | Universal: Specific holders for single crystals (goniometer heads with cryoloops) and powder (flat plate, capillary) |

| Cryoprotective Oils | Protecting crystals from radiation damage and dehydration during data collection [23] | SCXRD: Mounting temperature-sensitive crystals for cryogenic data collection |

| Reference Standards | Instrument calibration and quantitative phase analysis [23] | PXRD: Accuracy verification and quantitative analysis using known materials |

| Crystallographic Databases | Phase identification and structural comparison (PDF-2, ICSD, COD) [27] [17] | Universal: Reference patterns for phase identification and structural information |

| Gardenia yellow | Gardenia yellow, MF:C44H64O24, MW:977.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Fuziline (Standard) | Fuziline (Standard), MF:C24H39NO7, MW:453.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Selecting between Single Crystal XRD and Powder XRD requires careful consideration of research objectives, sample characteristics, and available resources. SCXRD remains the gold standard for complete structural elucidation, providing atomic-level resolution for compounds that form suitable crystals [23]. Its ability to directly determine bond lengths, angles, and atomic positions makes it indispensable for molecular structure determination in chemistry and pharmaceutical development [23] [24].

PXRD offers complementary strengths in throughput, accessibility, and application to complex mixtures [23]. Its capacity for quantitative phase analysis, crystallinity measurement, and stress/strain analysis makes it invaluable for materials characterization, quality control, and studying materials that resist single crystal formation [24] [27].

For nucleation and growth studies, both techniques provide crucial structural information. SCXRD can reveal detailed molecular interactions and packing arrangements that influence crystal growth, while PXRD enables monitoring of phase transformations and quantitative analysis of crystalline phase development over time [22]. Recent computational advances, including machine learning approaches and database-free structure determination, continue to expand the capabilities of both techniques, promising enhanced structural insights for future materials research [17] [28].

Within the field of X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis for phase structure and nucleation studies, the Protein Data Bank (PDB) and the Powder Diffraction File (PDF) serve as two foundational databases. While both are integral to the materials characterization workflow, they cater to distinct scientific domains and types of materials. The PDB is the single global archive for experimentally determined 3D structures of biological macromolecules, primarily proteins and nucleic acids [29]. In contrast, the PDF, maintained by the International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDD), is the most comprehensive database for phase identification and material characterization using powder XRD, covering a vast array of inorganic, organic, and mineral phases [30]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two resources, framing their capabilities within the context of advanced XRD research.

The following table summarizes the core attributes and primary applications of the PDB and PDF databases, highlighting their distinct roles in scientific research.

Table 1: Core Database Comparison: PDB vs. PDF

| Feature | Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Powder Diffraction File (PDF) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Scope | 3D structures of biological macromolecules (proteins, nucleic acids, complexes) [29] | Crystalline phase data for inorganic, organic, organometallic, and mineral materials [30] |

| Dominant Data Type | Atomic-level 3D coordinates from XRD, NMR, and 3DEM [29] | Characteristic d-spacings and relative intensities for diffraction pattern matching ("fingerprinting") [30] [1] |

| Key Application in Research | Understanding biological function, structure-guided drug discovery, and molecular mechanisms [29] | Qualitative and quantitative phase analysis, identification of unknown materials, and monitoring phase transformations [30] |

| Role in Nucleation Studies | Provides atomic-level insights into the structure of nucleating proteins and complexes [31] | Serves as a reference library for identifying crystalline phases that nucleate from a melt or solution [30] [31] |

| Representative Experimental Method | Single-crystal XRD [32] [33] | Powder XRD (XRPD) [30] [33] |

Experimental Data and Performance in Phase Identification

The performance of each database is best evaluated by its accuracy in identifying the correct structure or phase from experimental data. The PDB enables deep structural analysis, while the PDF excels in rapid phase identification.

Table 2: Performance Comparison in Structural and Phase Analysis

| Performance Metric | Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Powder Diffraction File (PDF) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Output | Full 3D atomic model revealing molecular shape, active sites, and ligand binding [32] | List of matched crystalline phases and their relative abundance in a mixture [30] |

| Quantitative Data Output | Atomic coordinates, bond lengths/angles, resolution, and R-values to quantify model quality [32] | Lattice parameters, crystallite size, phase percentages, and strain measurements [30] [1] |

| Identification Workflow | Structure determination via phasing and refinement; search by sequence or similarity [29] | Pattern matching of peak positions and intensities against database references [30] |

| Typical Resolution | High (e.g., 1.90 Ã… for 7AAT [32]) | Varies with sample and instrument, sufficient for distinct peak separation |

| Throughput | Structure determination can be days to months, but database query is instantaneous | Rapid analysis (often under 20 minutes) with potential for full automation [30] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Structure Determination and Phase ID

Protocol: Single-Crystal Protein Structure Determination with PDB Deposition

This protocol is used for determining the atomic structure of a biological macromolecule, with the final structure often deposited into the PDB [32].

- Protein Purification and Crystallization: Purify the protein of interest to homogeneity. Grow a single, high-quality crystal using vapor diffusion or other techniques by optimizing conditions like pH, temperature, and precipitant concentration.

- Data Collection (MX): Flash-cool the crystal in liquid nitrogen. Mount the crystal on a diffractometer at a synchrotron or home source (e.g., Microfocus Tube or Rotating Anode Generator [33]). Collect a complete dataset of diffraction images by rotating the crystal through a series of angles.

- Data Processing: Index the diffraction spots to determine the unit cell parameters. Integrate the intensity of each spot and scale the datasets. This yields a list of structure factor amplitudes (

Fobs). - Phasing: Solve the "phase problem" to estimate the phases for the structure factors. Common methods include Molecular Replacement (using a known homologous structure as a search model), or experimental methods like Single-wavelength Anomalous Dispersion (SAD).

- Model Building and Refinement: Fit an atomic model into the experimental electron density map using software like Coot. Refine the model iteratively against the

Fobsdata by adjusting atomic coordinates and temperature factors to minimize the R-value and R-free [32]. - Validation and Deposition: Validate the final model using tools like the wwPDB Validation Server. Deposit the atomic coordinates, structure factors, and associated metadata into the PDB [29].

Protocol: Phase Identification of an Unknown Powder using the PDF

This protocol is standard for identifying the crystalline phases present in an unknown powder sample [30] [1].

- Sample Preparation: Grind the powder to a fine consistency to minimize preferred orientation (texture). Pack the powder into a flat-backed sample holder or a capillary to present a random orientation of crystallites to the X-ray beam.

- Data Acquisition (XRPD): Load the sample into the X-ray diffractometer. Set the instrument (with a vertical goniometer and PIXcel detector, for example [30]) to scan over the desired 2θ range (e.g., 5° to 80°). The X-ray source (commonly Cu Kα, λ = 1.5418 Å) irradiates the sample, and the detector records the intensity of the diffracted beam at each angle [1].

- Data Pre-processing: Process the raw data by applying smoothing and subtracting the background. Identify the position (2θ) and intensity of each diffraction peak in the pattern.

- Pattern Matching (Search/Match): Convert the 2θ peak positions to d-spacings using Bragg's Law (nλ = 2d sinθ [1]). Use search/match software to compare the list of d-spacings and relative intensities from the unknown sample against the reference patterns in the PDF database.

- Phase Identification and Refinement: Identify the phases present in the sample based on the best-matching reference patterns. For quantitative or complex mixtures, use refinement methods like Rietveld refinement to determine the precise phase fractions and unit cell parameters.

Workflow Visualization for XRD Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow for X-ray diffraction analysis, from sample to structure, highlighting the distinct paths for single-crystal and powder studies and the roles of the PDB and PDF.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details essential materials and reagents used in typical XRD experiments for biological and materials science applications.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for XRD Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Purified Protein | The biological macromolecule of interest; requires high purity and homogeneity for successful crystallization and structure determination. |

| Crystallization Kits | Commercial screens containing diverse combinations of precipitants, buffers, and salts to efficiently identify initial conditions for protein crystal growth. |

| Cryoprotectant (e.g., Glycerol) | A chemical added to the crystal before flash-cooling in liquid nitrogen to prevent the formation of destructive ice crystals. |

| Fine Powder Standard (e.g., Si, SiOâ‚‚) | A well-characterized crystalline material with a known diffraction pattern used to calibrate the powder diffractometer and check instrument alignment. |

| Zero-Background Holder | A sample holder made of a single crystal of silicon cut at a specific orientation, which produces minimal diffraction background, thereby improving the signal-to-noise ratio for powder samples. |

| Indexing & Refinement Software (e.g., PROLSQ) | Computational tools used for processing diffraction data, solving crystal structures (e.g., PROLSQ was used for 7AAT [32]), and performing Rietveld refinement for quantitative phase analysis. |

| Gardenia yellow | Gardenia yellow, CAS:89382-88-7, MF:C44H64O24, MW:977.0 g/mol |

| 3-Hydroxycapric acid | 3-Hydroxydecanoic Acid | High-Purity Fatty Acid | RUO |

Applied XRD Techniques for Drug Polymorphism, Co-crystals, and Formulation

In the pharmaceutical industry, the unexpected appearance of undefined crystalline forms could significantly impact the therapeutic efficacy of an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) [34]. Polymorphs—different crystalline forms of the same chemical compound—exhibit distinct crystal structures that result in different physical and chemical properties, including solubility, stability, melting point, and most critically, bioavailability [34] [35]. A thorough qualitative and quantitative monitoring of pharmaceutical solid forms is therefore essential for quality control to ensure the detection and quantification of crystalline forms, whether different polymorphs or other solid forms, even at low detection levels [34]. The imperative for robust polymorph screening and identification stems from the direct impact on drug safety and efficacy, making it a fundamental requirement in pharmaceutical development and manufacturing.

The challenges in polymorph control were starkly illustrated by the case of ABT-333 and ABT-072, two potent non-nucleoside NS5B polymerase inhibitors for hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment [36]. These structural analogs differ only by a minor substituent change—the replacement of a naphthyl group with a trans-olefin—yet this minor modification led to significant differences in their conformational preferences and intermolecular interactions, resulting in a ripple effect with substantial drug development implications, including crystal polymorphism, low aqueous solubility, and formulation development challenges [36]. Such cases underscore why controlling polymorphism is not merely a scientific curiosity but a critical component of pharmaceutical quality systems worldwide.

Essential Techniques for Polymorph Analysis

Multiple analytical techniques are employed for the detection and quantification of polymorphic forms, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and appropriate application contexts [34]. The selection of adequate solid-state techniques is fundamental based on limits of detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ), pharmacopeial specifications, and international guidelines [34].

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Techniques for Polymorph Identification and Quantification

| Technique | Primary Application | Key Strengths | Limitations | Typical LOD/LOQ Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Powder Diffraction (XRPD) | Crystal structure analysis, phase identification, quantification [34] [35] | Direct crystal structure information; distinguishes polymorphs based on unique diffraction patterns; can use calculated patterns from CIF files without physical standards [34] [35] | Primarily for crystalline materials; requires careful sample preparation [3] [35] | LOD can reach ~0.3% with Rietveld refinement [34] [35] |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Thermal transition analysis [34] | Detects melting points, solid-solid transitions, and desolvation events [34] | Indirect structural information; thermal events may overlap or be irreversible [34] | Varies significantly by API and transition enthalpy [34] |

| Infrared (IR) and Raman Spectroscopy | Molecular vibration analysis [34] | Sensitive to conformational and hydrogen-bonding differences; can analyze small particles [34] | Can be affected by particle size and pressure; may require interpretation [34] | Raman can detect polymorphs in small particles [34] |

| Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (ssNMR) | Local atomic environment analysis [34] | Powerful for quantification of crystalline and crystalline-amorphous mixtures; provides detailed structural information [34] | Expensive; low-throughput; requires specialized expertise [34] | Excellent quantification limits for crystalline-amorphous mixtures [34] |

The Gold Standard: X-ray Powder Diffraction (XRPD)

X-ray diffraction (XRD) is a foundational technique for analyzing the crystallographic structure of materials [3]. When X-rays interact with a crystalline material, they are diffracted by the lattice planes according to Bragg's Law (nλ = 2d sinθ), producing a unique pattern of peaks characterized by their position (2θ angle), intensity, and shape [3]. This diffraction pattern serves as a fingerprint for the crystal structure, enabling researchers to differentiate between polymorphic forms that have the same chemical composition but different atomic arrangements [3].

A major advantage of XRPD is the ability to use calculated diffraction patterns obtained from Crystallographic Information Framework (CIF) files as reference patterns without needing physical standards, which is particularly valuable during early development when pure reference materials may be unavailable [34]. For quantification, different pharmacopeias suggest methods such as PXRD combined with the Rietveld method, which can achieve lower LOD values for minority phases in mixtures without requiring a calibration curve [34]. This capability for both qualitative identification and quantitative analysis makes XRPD an indispensable tool in polymorph screening.

Experimental Protocols for Polymorph Identification and Quantification

XRPD Method for Polymorphic Impurity Quantification

The quantification of polymorphic impurities in APIs using XRPD involves a systematic, stepwise approach to ensure accuracy and regulatory compliance [35].

Step 1: Sample Preparation - The API must be finely ground to ensure homogeneity, free from moisture and contaminants, and packed in a consistent and reproducible manner to avoid artifacts such as peak broadening or preferred orientation [35].

Step 2: Reference Polymorph Selection - Pure forms of all relevant polymorphs must be obtained, including the desired polymorph (typically the most stable or bioavailable form) and any known or suspected impurities for generating calibration standards [35].

Step 3: XRPD Data Collection - Instrument parameters should be optimized for resolution, typically using Cu Kα radiation, a scan range of 5° to 40° 2θ, a step size of approximately 0.02°, and sufficient counting time to ensure a flat baseline and sharp peaks for accurate quantification [35].

Step 4: Peak Identification - Software or databases (e.g., ICDD PDF) are used to match peaks and identify characteristic peaks unique to each polymorph, prioritizing non-overlapping peaks for quantification whenever possible [35].

Step 5: Calibration Curve Preparation - Physical mixtures of the reference polymorphs are prepared in known proportions (e.g., 0%, 1%, 5%, 10%, 25%, 50%). XRPD patterns are acquired for each blend, and peak intensities or areas under selected peaks are measured to plot a calibration curve of peak intensity versus concentration [35].

Step 6: Sample Quantification - The sample's XRPD pattern is measured and compared against the calibration curve to determine the percentage of polymorphic impurity present. For complex patterns with overlapping peaks, advanced deconvolution techniques like Rietveld refinement or Principal Component Analysis (PCA) may be employed [35].

Step 7: Method Validation - The method must be validated according to ICH guidelines, including assessments of accuracy (spike recovery), precision (repeatability and intermediate precision), linearity of the calibration curve, and determination of Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantification (LOQ) [35].

Diagram 1: XRPD Polymorph Quantification Workflow. This workflow outlines the systematic process for quantifying polymorphic impurities in APIs using X-ray Powder Diffraction, from sample preparation to method validation.

Case Study: Quantitative Analysis of Polymorphic Impurities in Carbamazepine

Objective: To detect and quantify a known polymorphic impurity (Form II) in batches of Carbamazepine API, where Form III is the therapeutically approved and stable form, ensuring batch consistency and regulatory compliance [35].

Background: Carbamazepine exists in multiple polymorphic forms (Form I to Form IV), with Form III being the stable and pharmaceutically acceptable form. However, Form II, a metastable polymorph, can appear during certain crystallization or milling processes, potentially impacting solubility, dissolution rate, and long-term stability even at trace levels [35].

Materials and Methods:

- API Test Samples: Three batches of Carbamazepine labeled A, B, and C

- Reference Standards: Pure polymorphic forms—Form III (desired) and Form II (impurity)

- Sample Preparation: Finely ground powders packed into low-background sample holders and stored in a desiccator prior to analysis to avoid hydration or phase transformation

- Instrumentation: X-Ray Diffractometer (Bruker D8 Advance) with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å), scan range 5° to 35° 2θ, step size 0.02°, time per step 1s

- Calibration Curve Setup: Prepared binary physical mixtures of Form II and Form III in proportions of 0%, 1%, 2%, 5%, 10%, 20%, and 50% Form II; selected a characteristic peak of Form II at 15.2° 2θ; measured peak intensity (height and area) and plotted against % concentration [35]

Results:

- Calibration Curve: R² = 0.998 for intensity versus concentration of Form II; LOD: 0.3%; LOQ: 1.0%

- Batch Analysis:

Table 2: Carbamazepine Batch Analysis Results for Form II Impurity

| Batch | Peak Intensity at 15.2° 2θ | % Form II (calculated) | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 0.00 | < LOD (0.3%) | Passed - no detectable Form II |

| B | 0.45 | 1.2% | Passed - within acceptable limits (< 5%) |

| C | 1.00 | 2.8% | Flagged - exceeds internal specification (max 2%) |

Conclusion: XRPD successfully detected and quantified polymorphic impurities down to 1% concentration, providing a non-destructive and reproducible method for quality control of Carbamazepine API [35].

Advanced and Emerging Technologies in Polymorph Analysis

Computational Approaches: Crystal Structure Prediction and Molecular Simulations

With advancements in accurate simulation algorithms and increased access to parallel computing hardware, physics-based molecular simulations have become widely utilized in guiding molecular design and drug development [36]. Techniques such as Crystal Structure Prediction (CSP) can generate anhydrous crystal polymorphs, while algorithms like the Mapping Approach for Crystalline Hydrates (MACH) predict potential stable hydrates by inserting water molecules into anhydrous frameworks through a data-driven topological approach [36]. These computational methods provide unique atomistic or mechanistic insights into drug design by explicitly considering physical descriptors such as hydration shells, the solid-state environment, and dynamic molecular structure [36].

The application of these techniques to the ABT-072 and ABT-333 case study revealed that ABT-072 exhibits a diverse range of low-energy anhydrous structures due to the flexibility of its trans-olefin substituent, explaining its observed polymorphism. In contrast, ABT-333, with its more rigid naphthyl group, presented only a limited number of low-energy structures, with the highly stabilized experimental structure being the global minimum [36]. Such computational insights at early stages of drug discovery can help anticipate and mitigate development risks related to polymorphism.

Machine Learning in X-ray Diffraction Analysis

The quality and quantity of available crystal structure data have expanded dramatically in recent decades, driven by high-throughput materials synthesis and processing, online crystal structure databases, and increased use of in situ and operando methodologies [6]. This wealth of data has spawned increasing use of machine learning (ML) to either construct high-throughput surrogates of established analysis or extract patterns from large datasets [6]. Machine learning approaches are particularly valuable in emerging highly tunable materials systems like hybrid organic-inorganic semiconductors, where the vast composition and processing parameter space becomes quickly intractable for traditional analysis methods [6].

However, a significant challenge remains in bridging the gap between data analysis and the underlying physics, as XRD analysis has for decades been solved via Rietveld refinement, while most ML techniques are complex statistical evaluation methods that are physics-agnostic [6]. This discrepancy can lead to incorrect conclusions and limit the widespread adoption of ML techniques in polymorph analysis without careful validation against physical principles [6].

Emerging Techniques: Microcrystal Electron Diffraction (MicroED)

Microcrystal Electron Diffraction (MicroED) has emerged as a powerful technique for the structural analysis of solids from individual single crystallites of micrometer or even nanometer sizes [37]. This technique offers unique advantages, including dramatic reduction in the crystal size required for structural analysis at atomic resolution compared with X-ray single-crystal diffraction, experimental access to the three-dimensional reciprocal lattice, and relatively short data collection times without the need for extensive crystal growth [37]. The technique has been successfully applied to a wide range of materials, including pharmaceuticals, MOFs, natural products, and reactive organometallics [37].

Processes such as high-throughput screening of natural products and organic molecular solids of pharmaceutical interest, as well as studies of their impurities and polymorphism, can be drastically accelerated by MicroED [37]. However, drawbacks remain, including potential beam damage to the material, preferred orientation of the crystallites, higher residuals compared with single-crystal X-ray diffraction, and possible decomposition of the material under high vacuum [37]. Despite these limitations, MicroED represents a significant advancement in crystallography, complementing traditional X-ray diffraction methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Polymorph Screening

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity API Reference Standards | Serves as baseline for polymorph identification and quantification [35] | Must be thoroughly characterized; should include all known polymorphic forms |

| Crystallization Solvents | Medium for polymorph screening via recrystallization [38] | Should cover diverse polarity (water, alcohols, acetonitrile, chlorinated solvents) |

| Crystal Screen Packages | Initial broad screening of crystallization conditions [38] | Typically 50+ solutions varying in precipitant, buffer, pH, and salt (sparse matrix) |

| XRPD Reference Databases | Reference patterns for phase identification (e.g., ICDD PDF) [3] [35] | Commercial and public databases (COD, ICSD); calculated patterns from CIF files [6] [34] |

| Low-Background Sample Holders | Holds powder samples for XRPD analysis [35] | Minimizes background noise; enables consistent and reproducible packing |

| Thermal Analysis Equipment | DSC and TGA for complementary polymorph characterization [34] | Detects thermal transitions, desolvation events, and decomposition temperatures |

| Spectroscopic Standards | Reference materials for IR, Raman, and ssNMR [34] | Enables correlation of spectral features with specific polymorphic structures |

| Computational Software | Crystal structure prediction and molecular modeling [36] | CSP algorithms, molecular dynamics simulations, and density functional theory |

| Bacopaside IV | Bacopaside IV, MF:C41H66O13, MW:767.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Hypoglaunine A | Hypoglaunine A, MF:C41H47NO20, MW:873.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Diagram 2: Integrated Polymorph Screening Strategy. This diagram illustrates the multidisciplinary approach to comprehensive polymorph screening, combining experimental, computational, and analytical techniques to develop robust control strategies.

Polymorph screening and identification represents a critical frontier in ensuring API consistency and therapeutic efficacy. The case of Carbamazepine demonstrates the practical application of XRPD for quantifying polymorphic impurities at pharmaceutically relevant levels, while the ABT-333/ABT-072 example illustrates how minor molecular modifications can significantly alter solid-state behavior [36] [35]. As pharmaceutical regulations continue to emphasize solid-state control, mastering these techniques becomes increasingly valuable for analytical scientists and formulation developers.

The future of polymorph screening lies in the integration of traditional experimental methods with emerging computational and machine learning approaches [6] [36]. Crystal structure prediction, molecular dynamics simulations, and MicroED are expanding the toolkit available to pharmaceutical scientists, enabling more proactive management of polymorphism risks early in development [36] [37]. However, these advanced techniques complement rather than replace established methods like XRPD, which remains the gold standard for polymorph identification and quantification due to its direct probing of crystal structure and compatibility with regulatory requirements [34] [35]. Through the continued refinement and integration of these diverse methodologies, the pharmaceutical industry can better ensure the consistency, quality, and efficacy of drug products for patients worldwide.

Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD) represents a paradigm shift in pharmaceutical development, moving beyond traditional trial-and-error approaches to a precise methodology grounded in atomic-level structural knowledge. This approach relies fundamentally on understanding the three-dimensional architecture of biological targets and their interactions with potential therapeutic compounds. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SC-XRD) has emerged as the cornerstone technique in this field, providing unparalleled resolution of protein-ligand complexes and enabling researchers to visualize drug binding sites with atomic precision [39]. The technique's critical importance is reflected in the exponential growth of the Protein Data Bank (PDB), which has expanded from less than 90,000 structures in 2012 to over 190,000 macromolecular structures by 2022, with X-ray crystallography contributing approximately 85% of these deposits [40].

The pharmaceutical industry's investment in SBDD is driven by the staggering costs and timelines associated with traditional drug development, which can exceed $2.6 billion and two decades per approved drug [41]. Within this challenging landscape, SC-XRD serves as a crucial accelerant, allowing researchers to validate drug targets by visualizing active sites, binding pockets, and conformational states, thereby ensuring that only the most promising targets advance through the discovery pipeline [39]. This structural validation is particularly valuable for high-value targets like G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) and epigenetic regulators, where precise molecular interactions determine therapeutic efficacy [39]. As drug discovery evolves, SC-XRD continues to provide the fundamental structural insights necessary to understand the chemical determinants of potency and specificity, ultimately enabling the rational design of optimized drug candidates.

The Central Role of Single-Crystal XRD in SBDD Workflows

Fundamental Principles and Methodologies

SC-XRD functions by measuring how crystals of a target protein diffract incident X-rays, generating patterns that can be transformed into detailed electron density maps. These maps reveal the atomic structure of both the protein and any bound ligands, providing critical information about binding site occupancy, ligand pose, and the mechanism of interaction [39]. The process begins with protein purification and crystallization, where homogeneous protein preparations undergo trial-and-error screening of hundreds to thousands of conditions to identify parameters that yield high-quality crystals [40]. Ligands are typically introduced through co-crystallization or by soaking into pre-formed crystals, after which the crystals are harvested and often cryo-cooled in liquid nitrogen for data collection [40].

Traditional high-throughput SC-XRD relies on large, single crystals (100 microns or larger) and typically employs synchrotron radiation sources or advanced home-source systems like the Bruker D8 VENTURE with METALJET technology, which delivers synchrotron-like X-ray beams for in-house research [39]. These systems incorporate automated features for unattended data collection and rapid processing, significantly increasing throughput and reducing bottlenecks in pharmaceutical research pipelines. The structural data obtained enables researchers to examine intricate features such as hydrogen bonding networks, conformational flexibility, and intermolecular interactions that profoundly influence a compound's pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles [39].

Key Applications in Drug Discovery

Target Validation and Active Site Characterization: SC-XRD provides direct visualization of protein active sites, enabling researchers to confirm a target's role in disease and its potential for therapeutic modulation. For example, studies of the coronavirus methyltransferase (MTase) complex with its nsp10 cofactor revealed the binding site of the inhibitor sinefungin adjacent to the RNA binding pocket, validating this complex as a promising target for antiretroviral therapy [39].

Ligand Binding Mode Analysis: The technique excels at determining precisely how drug molecules interact with their targets. Case studies with human carbonic anhydrase II (HCA II) demonstrate that SC-XRD can unequivocally resolve bound inhibitors like acetazolamide, showing the ionized –NH group binding directly to the catalytic zinc atom and detailing the network of hydrogen bonds that confer inhibitory activity [42].