Transformer Architectures in Materials Science: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

This article explores the transformative impact of transformer architectures in materials science and drug discovery.

Transformer Architectures in Materials Science: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

This article explores the transformative impact of transformer architectures in materials science and drug discovery. It details the foundational principles of the self-attention mechanism that allows these models to manage complex, long-range dependencies in scientific data. The scope covers key methodological applications, from predicting material properties and optimizing molecular structures to accelerating virtual drug screening. The article also addresses critical challenges like data scarcity and model interpretability, providing troubleshooting strategies and a comparative analysis of transformer models against traditional computational methods. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes the latest advancements to inform and accelerate data-driven scientific discovery.

The Core of the Matter: Foundational Principles of Transformers for Scientific Data

Deconstructing the Self-Attention Mechanism for Materials and Molecules

The integration of transformer architectures and their core self-attention mechanism into materials science and molecular research represents a paradigm shift in property prediction and generative design. This whitepaper deconstructs the self-attention mechanism, detailing its operational principles and demonstrating its adaptation to the unique challenges of representing crystalline materials and molecular structures. We provide a comprehensive analysis of state-of-the-art models, quantitatively benchmark their performance across key property prediction tasks, and outline detailed experimental protocols for their implementation. Framed within the broader thesis that transformer architectures enable a more nuanced, context-aware understanding of material compositions and molecular graphs, this guide serves as an essential resource for researchers and scientists driving innovation in computational materials science and drug development.

Transformer architectures, first developed for natural language processing (NLP), have emerged as powerful tools for modeling complex relationships in materials science and molecular design. Their core innovation, the self-attention mechanism, allows models to dynamically weigh the importance of different components within a system—be they words in a sentence, elements in a crystal composition, or atoms in a molecule. This capability is particularly valuable in materials informatics (MI), where it enables structure-agnostic property predictions and captures complex inter-element interactions that traditional methods often miss [1]. By processing entire sequences of information simultaneously, transformers overcome limitations of earlier recurrent neural networks (RNNs) that struggled with long-range dependencies and offered limited parallelization [2].

The application of transformers to the physical sciences represents a significant methodological advancement. Models can now learn representations of materials and molecules by treating them as sequences (e.g., chemical formulas, SMILES strings) or graphs, with self-attention identifying which features most significantly influence target properties. This approach has demonstrated exceptional performance across diverse tasks, from predicting formation energies and band gaps of inorganic crystals to forecasting absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) properties of drug candidates [1] [3]. The flexibility of the attention mechanism allows it to be adapted for various data representations, including composition-based feature vectors, molecular graphs, and crystal structures, providing a unified framework for materials and molecular modeling.

The Core Self-Attention Mechanism

The self-attention mechanism functions by enabling a model to dynamically focus on the most relevant parts of its input when producing an output. In the context of materials and molecules, this allows the model to discern which elements, atoms, or substructures are most critical for determining a specific property.

Fundamental Concepts and Mathematical Formulation

At its core, self-attention operates on a set of input vectors (e.g., embeddings of elements in a composition or atoms in a molecule) and computes a weighted sum of their values, where the weights are determined by their compatibility with a query. The seminal "Attention is All You Need" paper formalized this using the concepts of queries (Q), keys (K), and values (V) [2].

For an input sequence, these vectors are derived by multiplying the input embeddings with learned weight matrices. The self-attention output for each position is computed as a weighted sum of all value vectors in the sequence, with weights assigned based on the compatibility between the query at that position and all keys. This process is encapsulated by the equation:

Attention(Q, K, V) = softmax((QK^T) / √d_k )V

Here, the softmax function normalizes the attention scores to create a probability distribution, and the scaling factor √d_k (where d_k is the dimension of the key vectors) prevents the softmax gradients from becoming too small [2]. This mechanism allows each element in the sequence to interact with every other element, capturing global dependencies regardless of their distance in the sequence.

Adapting Self-Attention for Materials and Molecules

The application of self-attention to scientific domains requires thoughtful adaptation of the input representation:

- For Composition-Based Property Prediction: Models like CrabNet (Compositionally Restricted Attention-Based Network) treat a chemical formula as a sequence of elements. The self-attention mechanism then learns the interactions between different elements in the composition, effectively capturing the chemical environment. This allows the model to recognize that trace dopants, despite their low stoichiometric prevalence, can have an outsized impact on properties—a scenario where traditional weighted-average featurization fails [1].

- For Molecular Graphs: Models like MolE represent a molecule as a graph and use a modified disentangled self-attention mechanism. In this setup, the input consists of atom identifiers (tokens) and graph connectivity information, which is incorporated as relative position information between atoms. The attention mechanism can then learn the importance of both atomic features and their topological relationships [3].

- For Crystal Structures: Hybrid frameworks, such as CrysCo, combine graph neural networks (GNNs) for local atomic environments with transformer attention networks (TAN) for compositional features. The self-attention component prioritizes global compositional trends and inter-element relationships that complement the structural details captured by the GNN [4].

Architectural Implementations and Performance

Several pioneering architectures have demonstrated the efficacy of self-attention for materials and molecules. The table below summarizes the key features and quantitative performance of leading models.

Table 1: Key Architectures Leveraging Self-Attention for Materials and Molecules

| Model Name | Primary Application | Input Representation | Key Innovation | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CrabNet [1] | Materials Property Prediction | Chemical Composition | Applies Transformer self-attention to composition, using element embeddings and fractional amounts. | Matches or exceeds best-practice methods on 28 of 28 benchmark datasets for properties like formation energy. |

| MolE [3] | Molecular Property Prediction | Molecular Graph | Uses disentangled self-attention adapted from DeBERTa to account for relative atom positions in the graph. | Achieved state-of-the-art on 10 of 22 ADMET tasks in the Therapeutic Data Commons (TDC) benchmark. |

| SANN [5] | Solubility Prediction | Molecular Descriptors (σ-profiles) | Self-Attention Neural Network that emphasizes interaction weights between HBDs and HBAs in deep eutectic solvents. | R² of 0.986-0.990 on test set for predicting CO₂ solubility in NADESs. |

| CrysCo [4] | Materials Property Prediction | Crystal Structure & Composition | Hybrid framework combining a GNN for 4-body interactions and a Transformer network for composition. | Outperforms state-of-the-art models in 8 materials property regression tasks (e.g., formation energy, band gap). |

| Materials Transformers [6] | Generative Materials Design | Chemical Formulas (Text) | Trains modern transformer LMs (GPT, BART, etc.) on large materials databases to generate novel compositions. | Up to 97.54% of generated compositions are charge neutral and 91.40% are electronegativity balanced. |

The performance benchmarks in Table 1 underscore a consistent trend: models incorporating self-attention consistently match or surpass previous state-of-the-art methods. For instance, CrabNet's performance is comparable to other deep learning models like Roost and significantly outperforms classical methods like random forests, demonstrating the inherent power of the attention-based approach [1]. The high accuracy of the SANN model in predicting COâ‚‚ solubility highlights the mechanism's utility in fine-grained analysis, where understanding the relative contribution of different molecular components (like HBAs and HBDs) is crucial [5].

Furthermore, the generative capabilities of transformer models, as evidenced by the "Materials Transformers" study, reveal their potential not just for prediction but also for the discovery of new materials. The high rates of chemically valid compositions generated by these models open a promising avenue for inverse design [6].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Implementing and training transformer models for scientific applications requires a structured workflow. Below, we detail the standard protocols for two primary use cases: composition-based property prediction and molecular property prediction via graph-based transformers.

Protocol A: Composition-Based Property Prediction (e.g., CrabNet)

This protocol is designed for predicting material properties from chemical formulas alone.

Data Acquisition and Curation:

- Source: Obtain materials data from public databases such as the Materials Project (MP), the Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD), or the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [1] [6].

- Cleaning: Remove duplicate compositions. For duplicates with varying property values, select the entry with the lowest formation energy or use the mean target value [1].

- Splitting: Split the dataset into training, validation, and test sets. Ensure no composition in the training set appears in the validation or test sets to prevent data leakage. A typical ratio is 70/15/15, but this may be adjusted based on dataset size.

Input Featurization:

- Representation: Represent each chemical composition as a set of element symbols and their corresponding fractional amounts (stoichiometric ratios).

- Embedding: Convert each element symbol into a dense vector. This can be a learned embedding (initialized randomly) or a pre-trained embedding such as mat2vec [1].

Model Architecture and Training:

- Architecture: Implement a Transformer encoder stack. The input sequence is the set of element embeddings, which are combined with positional encodings (or a learned bias) to indicate element identity.

- Self-Attention: The core of the model. The mechanism allows each element to attend to all other elements in the composition, updating its own representation based on the learned importance of its peers.

- Output Head: The output of the transformer is passed through a feed-forward neural network to produce a single property prediction (e.g., formation energy, bandgap).

- Training: Use the Adam optimizer and the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) or Mean Squared Error (MSE) as the loss function. Performance is typically evaluated using MAE on the held-out test set [1].

Protocol B: Molecular Property Prediction with Graph Transformers (e.g., MolE)

This protocol is for predicting properties from molecular structure, using a graph-based transformer.

Data Preparation:

- Source: Use molecular datasets, such as those from the Therapeutic Data Commons (TDC) for ADMET properties [3].

- Processing: Standardize molecules (e.g., neutralize charges, remove duplicates) using a toolkit like RDKit.

Graph Construction and Featurization:

- Graph Representation: Represent each molecule as a graph where nodes are atoms and edges are bonds.

- Node Features (Atom Identifiers): Calculate features for each atom (node) by hashing atomic properties into a single integer. The Morgan algorithm with a radius of 0, as implemented in RDKit, can generate these features, which typically include [3]:

- Number of neighboring heavy atoms

- Number of neighboring hydrogen atoms

- Valence minus the number of attached hydrogens

- Atomic charge

- Atomic mass

- Attached bond types

- Ring membership

- Edge Features (Graph Connectivity): Represent the molecular connectivity as a topological distance matrix

d, whered_ijis the length of the shortest path (in number of bonds) between atomiand atomj[3].

Model Architecture and Pretraining:

- Architecture: Implement a Transformer model that uses a modified self-attention mechanism, such as disentangled attention [3].

- Disentangled Attention: This variant, used in MolE, computes attention scores not only from the content of the atoms (queries and keys) but also explicitly from their relative positions in the graph [3]:

a_ij = Q_i^c • K_j^c + Q_i^c • K_i,j^p + K_j^c • Q_j,i^p

- Pretraining (Highly Recommended):

- Step 1 - Self-Supervised Pretraining: Train the model on a large, unlabeled corpus of molecular graphs (e.g., 842 million molecules from ZINC20) using a BERT-like masking strategy. The objective is not just to predict the masked atom's identity but to predict its atom environment of radius 2 (all atoms within two bonds) [3].

- Step 2 - Supervised Pretraining: Further pretrain the model on a large, labeled dataset with diverse properties to learn general biological or chemical information [3].

- Finetuning and Prediction: Finetune the pretrained model on the specific, smaller downstream task (e.g., a specific ADMET endpoint). Add a task-specific output head to the model for the final prediction.

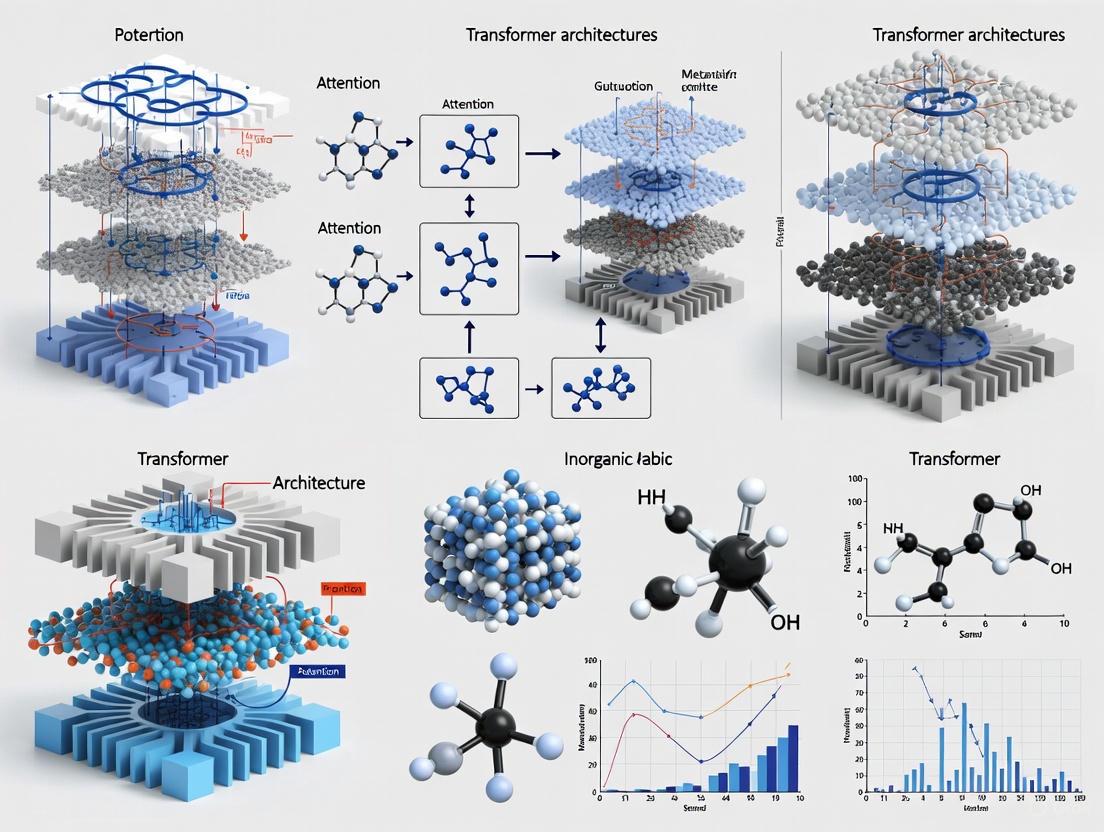

The following diagram illustrates the high-level logical workflow common to both protocols, from data preparation to model output.

Diagram 1: High-level workflow for self-attention models in materials and molecules.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Implementing and experimenting with self-attention models requires a suite of software tools and data resources. The table below catalogues the key components of a modern research pipeline.

Table 2: Essential "Research Reagents" for Transformer-Based Materials and Molecular Modeling

| Category | Item | Function / Description | Example Tools / Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Resources | Materials Databases | Provide structured, computed, and experimental data for training and benchmarking. | Materials Project (MP), OQMD, ICSD [1] [6] |

| Molecular Databases | Provide molecular structures and associated property data for drug discovery and QSAR. | Therapeutic Data Commons (TDC), ZINC20, ExCAPE-DB [3] | |

| Software & Libraries | ML Frameworks | Provide the foundational infrastructure for building, training, and deploying neural network models. | PyTorch, TensorFlow, JAX |

| Chemistry Toolkits | Handle molecule standardization, featurization, descriptor calculation, and graph generation. | RDKit [3] | |

| Specialized Models | Open-source implementations of state-of-the-art models that serve as a starting point for research. | CrabNet, Roost, MolE, ALIGNN [1] [3] [4] | |

| Computational Resources | DFT Codes | Generate high-fidelity training data and validate predictions from ML models. | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Accelerate the training of large transformer models and the execution of high-throughput DFT calculations. | GPU Clusters (NVIDIA A100, H100), Cloud Computing (AWS, GCP, Azure) | |

| Einecs 300-803-9 | Einecs 300-803-9|High-Purity Chemical for Research | Research-grade Einecs 300-803-9 for lab use. Explore its specific applications and value. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

| 3X8QW8Msr7 | 3X8QW8MSR7|C15H16BrN3S|RUO | High-purity 3X8QW8MSR7 (C15H16BrN3S) for laboratory research. This product is For Research Use Only and not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Adaptations and Interpretability

The core self-attention mechanism is often enhanced with specialized adaptations to increase its power and interpretability for scientific problems.

Enhanced Geometric and Interaction Modeling

- Four-Body Interactions in Crystals: Advanced frameworks like CrysGNN explicitly model four-body interactions (atoms, bonds, angles, dihedral angles) within a graph neural network, which is then combined with a composition-based attention network (CoTAN) in a hybrid model (CrysCo). This allows the model to capture both local periodic/structural characteristics and global compositional trends [4].

- Disentangled Attention for Graphs: The MolE model modifies the disentangled attention mechanism from DeBERTa to incorporate the relative position of atoms in a molecular graph explicitly. This is done by adding terms to the attention score calculation that depend on the relative topological distance between atoms, leading to more informative molecular embeddings [3].

Interpreting Model Decisions

The "black box" nature of complex models is a concern in science. Fortunately, the attention mechanism itself provides a native path to interpretability.

- Attention Weight Visualization: The attention weights learned by models like CrabNet can be visualized to show which elements in a composition are deemed most important for a given prediction. This lends credibility to the model and can potentially yield new chemical insights [1].

- Advanced Attribution Methods: For deeper interpretation, methods like Contrast-CAT have been developed. This technique contrasts the activations of an input sequence with reference activations to filter out class-irrelevant features, generating sharper and more faithful attribution maps that explain which tokens (e.g., words, atoms) were most influential in a classification decision [7].

- SHAP Analysis: SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis can be applied to models like SANN to quantify the contribution of individual input features (e.g., specific molecular descriptors of HBAs/HBDs) to the model's output, providing a model-agnostic interpretation [5].

The self-attention mechanism, as the operational core of transformer architectures, has profoundly impacted materials science and molecular research. By providing a flexible, powerful framework for modeling complex, long-range interactions within compositions and graphs, it has enabled a new generation of predictive and generative models with state-of-the-art accuracy. The continued evolution of these architectures—through the incorporation of geometric principles, advanced pretraining strategies, and robust interpretability methods—is steadily bridging the gap between data-driven prediction and fundamental scientific understanding. As these tools become more accessible and refined, they are poised to dramatically accelerate the cycle of discovery and design for novel materials and therapeutic molecules.

The transformer architecture, having revolutionized natural language processing (NLP), is now fundamentally reshaping computational materials science. Originally designed for sequence-to-sequence tasks like machine translation, its core self-attention mechanism provides a uniquely powerful framework for modeling complex, non-local relationships in diverse data types [8]. This technical guide examines the architectural adaptations that enable transformers to process materials science data—from crystalline structures to quantum chemical properties—thereby accelerating the discovery of novel materials for energy, sustainability, and technology applications. The migration from linguistic to scientific domains requires overcoming significant challenges, including data scarcity, the need for geometric awareness, and integration of physical laws, leading to innovative hybrid architectures that extend far beyond the transformer's original design.

Core Architectural Foundations

The transformer's initial breakthrough stemmed from its ability to overcome the sequential processing limitations of Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), such as vanishing gradients and limited long-range dependency modeling [8]. Its core innovation lies in the self-attention mechanism, which processes all elements in an input sequence simultaneously, calculating relationship weights between all pairs of elements regardless of their positional distance.

Deconstructing the Self-Attention Mechanism

The mathematical heart of the transformer is the scaled dot-product attention function:

Attention(Q, K, V) = softmax(QKᵀ/√dₖ)V

Where:

- Query (Q): A vector representing the current focus element

- Key (K): A vector against which the query is compared

- Value (V): The actual information content to be aggregated

- dâ‚–: The dimensionality of key vectors, used for scaling [8]

This mechanism enables the model to dynamically weight the importance of different input elements when constructing representations, rather than relying on fixed positional encodings or sequential processing. For materials science, this capability translates to modeling complex atomic interactions where an atom's behavior depends on multiple neighboring atoms simultaneously, not just its immediate vicinity.

Encoder-Decoder Configuration Variants

Different transformer configurations have emerged for specialized applications:

- Encoder-Only Models (e.g., BERT): Excel at understanding and representation learning tasks, suitable for property prediction from material descriptors [8]

- Decoder-Only Models (e.g., GPT): Specialize in generative tasks, applied to novel material structure generation [8]

- Encoder-Decoder Models: Handle sequence-to-sequence transformations, useful for cross-property prediction tasks

Table 1: Core Transformer Components and Their Scientific Adaptations

| Component | Original NLP Function | Materials Science Adaptation | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Attention | Capture word context | Model atomic interactions | Handles non-local dependencies |

| Positional Encoding | Word order | Geometric/structural information | Encodes spatial relationships |

| Feed-Forward Networks | Feature transformation | Property mapping | Learns complex structure-property relationships |

| Multi-Head Attention | Multiple relationship types | Diverse interaction types | Captures different chemical bonding patterns |

Adapting Transformers for Materials Science Data

The application of transformers to materials science necessitates fundamental architectural modifications to handle the unique characteristics of scientific data, which incorporates 3D geometry, physical constraints, and diverse representation formats.

Input Representation Strategies

Materials data presents in fundamentally different formats than linguistic data, requiring specialized representation approaches:

- Composition-Based Representations: Models like CrabNet process elemental composition data using transformer architectures that treat chemical formulas as "sentences" where elements are "words" with learned embeddings, augmented with physical properties as continuous embeddings [4]

- Graph-Based Representations: Crystalline materials are naturally represented as graphs with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges. Hybrid frameworks like CrysCo combine graph neural networks with transformers, where GNNs capture local atomic environments and transformers model long-range interactions [4]

- Sequence-Based Encodings: Simplified molecular-input line-entry system (SMILES) strings and other linear notations treat chemical structures as character sequences, enabling direct application of NLP-inspired transformer models for generative tasks [9]

Geometric and Physical Awareness Integration

A critical limitation of standard transformers in scientific domains is their lack of inherent geometric awareness, which is essential for modeling atomic systems. Several innovative approaches address this limitation:

- Explicit Geometric Descriptors: The multi-feature deep learning framework for CO adsorption prediction integrates structural, electronic, and kinetic descriptors through specialized encoders, with cross-feature attention mechanisms capturing their interdependencies [10]

- Four-Body Interactions: Advanced graph transformer frameworks explicitly incorporate higher-order interactions including bond angles and dihedral angles through multiple graph representations (G, L(G), L(Gd)), enabling accurate modeling of periodicity and structural characteristics [4]

- Equivariant Transformers: Architectures like EquiformerV2 build rotational and translational equivariance directly into the attention mechanism, ensuring predictions remain consistent with physical symmetries [10]

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Transformer-Based Materials Models

| Model/Architecture | Target Property/Prediction | Performance Metric | Result | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Feature Transformer [10] | CO Adsorption Energy | Mean Absolute Error | <0.12 eV | Integration of structural, electronic, kinetic descriptors |

| Hybrid Transformer-Graph (CrysCo) [4] | Formation Energy, Band Gap | MAE vs. State-of-the-Art | Outperforms 8 baseline models | Four-body interactions & transfer learning |

| BERT-Based Predictive Model [11] | Career Satisfaction | Classification Accuracy | 98% | Contextual understanding of multifaceted traits |

| ME-AI Framework [12] | Topological Semimetals | Prediction Accuracy | High (Qualitative) | Expert-curated features & interpretability |

Key Applications and Experimental Protocols

Property Prediction with Limited Data

Predicting material properties with limited labeled examples represents a significant challenge where transformers have demonstrated notable success. The transfer learning protocol employed in hybrid transformer-graph frameworks addresses this challenge through a systematic methodology:

- Pre-training Phase: Train on data-rich source tasks (e.g., formation energy prediction) using large-scale computational databases like Materials Project (∼146,000 material entries) [4]

- Feature Extraction: Utilize the pre-trained model's intermediate representations as generalized material descriptors

- Fine-Tuning Phase: Adapt the model to data-scarce target tasks (e.g., mechanical properties like bulk and shear moduli) with limited labeled examples

- Multi-Task Integration: Extend beyond pairwise transfer learning to leverage multiple source tasks simultaneously, reducing catastrophic forgetting [4]

This approach has proven particularly valuable for predicting elastic properties, where only approximately 4% of materials in major databases have computed elastic tensors, demonstrating the transformer's ability to transfer knowledge across related domains [4].

Multi-Feature Learning for Catalytic Properties

The prediction of CO adsorption mechanisms on metal oxide interfaces illustrates a sophisticated multi-feature transformer framework that integrates diverse data modalities [10]:

Experimental Protocol:

- Descriptor Computation: Calculate readily computable molecular descriptors including structural (atomic coordinates), electronic (Hirshfeld charge analysis), and kinetic parameters (pre-computed activation barriers)

- Specialized Encoding: Process each descriptor type through modality-specific encoders (structural encoder, electronic encoder, kinetic encoder)

- Cross-Feature Attention: Apply attention mechanisms across different feature types to capture their interdependencies

- Mechanism Prediction: Output adsorption energies and identify dominant adsorption mechanisms (molecular vs. dissociative)

This approach achieves correlation coefficients exceeding 0.92 with DFT calculations while dramatically reducing computational costs, enabling rapid screening of catalytic materials [10]. Systematic ablation studies within this framework reveal the hierarchical importance of different descriptors, with structural information providing the most critical contribution to prediction accuracy.

Generative Design of Novel Materials

Beyond property prediction, transformers enable the inverse design of novel materials with targeted properties through sequence-based generative approaches:

Methodology:

- Representation Learning: Convert crystal structures to sequential representations (SMILES, SELFIES, or custom notations)

- Sequence Generation: Employ decoder-only transformer architectures to autoregressively generate novel material representations

- Property Conditioning: Guide generation using desired properties as prompt inputs or through classifier-free guidance techniques

- Validity Optimization: Incorporate valency constraints and structural stability directly into the training objective [9]

Models like MatterGPT and Space Group Informed Transformers demonstrate the capability to generate chemically valid and novel crystal structures, significantly accelerating the exploration of chemical space beyond human intuition alone [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Databases for Transformer-Based Materials Research

| Tool/Database | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Transformer Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Project [4] | Materials Database | Repository of computed material properties | Source of training data (formation energy, band structure, elastic properties) |

| ALIGNN [4] | Graph Neural Network | Atomistic line graph neural network | Provides 3-body interactions for hybrid transformer-graph models |

| CrabNet [4] | Transformer Model | Composition-based property prediction | Baseline for composition-only transformer approaches |

| MPDS [12] | Experimental Database | Curated experimental material data | Source of expert-validated training examples |

| VAMAS/ASTM Standards [9] | Data Standards | Standardized materials testing protocols | Ensures data consistency for model training |

| Nandrolone nonanoate | Nandrolone Nonanoate | Bench Chemicals | |

| 4a,6-Diene-bactobolin | 4a,6-Diene-bactobolin|High-Purity Research Compound | 4a,6-Diene-bactobolin is a research chemical for studying ribosomal antibiotics. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for diagnostic, therapeutic, or personal use. | Bench Chemicals |

Implementation Workflows and System Architecture

Hybrid Transformer-Graph Framework

The integration of transformer architectures with graph neural networks represents a particularly powerful paradigm for materials property prediction. The following workflow illustrates the operational pipeline of the CrysCo framework, which demonstrates state-of-the-art performance across multiple property prediction tasks [4]:

CrysCo Hybrid Architecture Workflow

This hybrid architecture processes materials through dual pathways:

- CrysGNN Pathway: Processes crystal structure information through 10 layers of edge-gated attention graph neural networks, explicitly capturing up to four-body interactions (atoms, bonds, angles, dihedral angles) [4]

- CoTAN Pathway: Processes compositional features and human-extracted physical properties through transformer attention networks inspired by CrabNet [4]

- Feature Fusion: Integrates structural and compositional representations for final property prediction

The framework's performance advantage stems from its ability to simultaneously leverage both structural and compositional information, with the transformer component specifically responsible for modeling complex, non-local relationships in the compositional space.

Multi-Feature Deep Learning Framework

For predicting complex catalytic mechanisms such as CO adsorption on metal oxide interfaces, a specialized multi-feature framework has been developed that integrates diverse descriptor types:

Multi-Feature CO Adsorption Prediction

This architecture employs:

- Specialized Encoders: Separate encoding pathways for structural, electronic, and kinetic descriptors

- Cross-Feature Attention: Attention mechanisms that model dependencies between different descriptor types

- Hierarchical Feature Importance: The model naturally learns the relative importance of different descriptors, with structural information typically providing the most significant contribution [10]

This approach demonstrates the advantage of transformers in integrating heterogeneous data types, a critical capability for modeling complex scientific phenomena where multiple physical factors interact non-linearly.

Future Directions and Challenges

Despite significant progress, several challenges remain in fully leveraging transformer architectures for materials science applications. The quadratic complexity of self-attention with respect to sequence length presents computational bottlenecks, particularly for large-scale molecular dynamics simulations or high-throughput screening [13]. Emerging solutions include:

- Sub-quadratic Attention Variants: Linear attention mechanisms and state space models that approximate full attention with reduced computational complexity [13]

- Sparse Attention Patterns: Local window attention and strided patterns that reduce the number of token-to-token connections

- Recurrent Hybrids: Architectures like Hierarchically Gated Recurrent Neural Networks that combine the parallel processing of transformers with the linear complexity of RNNs [13]

Additionally, improving data efficiency through advanced transfer learning techniques and addressing interpretability challenges through attention visualization and concept discovery remain active research areas. The integration of physical constraints directly into transformer architectures, rather than relying solely on data-driven learning, represents a promising direction for improving generalization and physical plausibility.

As transformer architectures continue to evolve beyond their linguistic origins, their ability to model complex relationships in scientific data positions them as foundational tools for accelerating materials discovery and advancing our understanding of material behavior across multiple scales and applications.

Why Transformers? Overcoming Limitations of Traditional ML and Sequential Models

The field of materials science research is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by the need to model increasingly complex systems—from molecular structures to composite material properties. Traditional machine learning (ML) and sequential models have long been the cornerstone of computational materials research. However, their inherent limitations in capturing long-range, multi-scale interactions present a significant bottleneck for innovation. The advent of the Transformer architecture, introduced in the seminal "Attention Is All You Need" paper, has emerged as a pivotal solution, redefining the capabilities of AI in scientific discovery [14] [15].

This technical guide examines the core architectural innovations of Transformers and delineates their superiority over traditional models within the context of materials science and drug development. By leveraging self-attention mechanisms and parallel processing, Transformers overcome critical limitations of preceding models, enabling breakthroughs in predicting material properties, protein folding, and accelerating the design of novel compounds [16]. We will explore the quantitative evidence supporting this shift, provide detailed experimental methodologies, and visualize the logical frameworks that make Transformers an indispensable tool for the modern researcher.

The Limitations of Traditional and Sequential Models

Before the rise of Transformers, materials research heavily relied on a suite of models, each with distinct constraints that hindered their ability to fully capture the intricacies of scientific data.

Fundamental Architectural Constraints

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and LSTMs: These models process data sequentially, one token or data point at a time. This sequential nature makes them inherently slow and difficult to parallelize, leading to protracted training times unsuitable for large-scale molecular simulations [17] [14]. More critically, they struggle with the vanishing gradient problem, which impedes their capacity to learn long-range dependencies—a fatal flaw when modeling interactions between distant atoms in a polymer or residues in a protein [17] [15].

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs): While excellent at capturing local spatial features (e.g., in 2D material images or crystallographic data), CNNs are fundamentally limited by their fixed, local receptive fields. They are not designed to efficiently model global interactions across a structure without prohibitively increasing model depth and complexity [18] [15].

The following table summarizes the key limitations of these traditional architectures when applied to materials science problems.

Table 1: Limitations of Traditional Models in Materials Science Contexts

| Model Type | Core Limitation | Impact on Materials Science Research |

|---|---|---|

| Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs/LSTMs) | Sequential processing leading to slow training and vanishing gradients [17] [14] | Inability to model long-range atomic interactions in polymers or proteins; slow simulation times. |

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) | Fixed local receptive fields struggle with global dependencies [18] | Difficulty in capturing system-wide properties in a material, such as stress propagation in a composite. |

| Traditional ML (e.g., Random Forests, SVMs) | Limited capacity for unstructured, high-dimensional data [16] | Poor performance on raw molecular structures or spectral data without heavy, lossy feature engineering. |

The Materials Modeling Bottleneck

These constraints created a direct bottleneck in research. Predicting emergent properties in materials often depends on understanding how distant components in a system influence one another. The failure of traditional models to capture these relationships meant that researchers either relied on computationally expensive physical simulations or faced inaccurate predictions from their ML models, slowing down the discovery cycle [16].

The Transformer Paradigm: Core Architectural Innovations

The Transformer architecture bypasses the limitations of its predecessors through a design centered on the self-attention mechanism. This allows the model to weigh the importance of all elements in a sequence, regardless of their position, simultaneously [18] [17].

Deconstructing the Self-Attention Mechanism

At its core, self-attention is a function that maps a query and a set of key-value pairs to an output. For a given sequence of data (e.g., a series of atoms in a molecule), each element (atom) is transformed into three vectors: a Query, a Key, and a Value [14]. The output for each element is computed as a weighted sum of the Values, where the weight assigned to each Value is determined by the compatibility of its Key with the Query of the element in question. This process can be expressed as:

[ \text{Attention}(Q, K, V) = \text{softmax}\left(\frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right)V ]

Where ( dk ) is the dimensionality of the Key vectors, and the scaling factor ( \frac{1}{\sqrt{dk}} ) prevents the softmax function from entering regions of extremely small gradients [18] [14].

In practice, Multi-Head Attention is used, where multiple sets of Query, Key, and Value projections are learned in parallel. This allows the model to jointly attend to information from different representation subspaces at different positions. For instance, one attention "head" might focus on bonding relationships between atoms, while another simultaneously focuses on spatial proximities [17] [14].

Complementary Architectural Components

Positional Encoding: Since the self-attention mechanism is permutation-invariant, positional encodings are added to the input embeddings to inject information about the order of the sequence. This is critical for structures where spatial or sequential order matters, such as in a polymer chain [19] [14]. Modern architectures have evolved from fixed sinusoidal encodings to more advanced methods like Rotary Positional Embeddings (RoPE), which offer better generalization to sequences longer than those seen in training [19].

Parallelization and Layer Normalization: Unlike RNNs, Transformers process entire sequences in parallel, dramatically accelerating training and inference on modern hardware like GPUs [17]. Furthermore, architectural refinements like Pre-Normalization and RMSNorm (Root Mean Square Normalization) are now commonly used to stabilize training and enable deeper networks by improving gradient flow [19].

Table 2: Core Transformer Components and Their Scientific Utility

| Component | Function | Utility in Materials Science |

|---|---|---|

| Self-Attention | Dynamically weights relationships between all sequence elements [18] [17] | Identifies critical long-range interactions between atoms or defects that dictate material properties. |

| Multi-Head Attention | Attends to different types of relationships simultaneously [14] | Can parallelly capture covalent bonding, van der Waals forces, and electrostatic interactions. |

| Positional Encoding | Injects sequence order information [19] [14] | Preserves the spatial or sequential structure of a molecule, protein, or crystal lattice. |

| Feed-Forward Layers | Applies a non-linear transformation to each encoded position [14] | Refines the representation of each individual atom or node within the global context. |

| Layer Normalization | Stabilizes training dynamics [19] | Enables the training of very deep, powerful models necessary for complex property prediction. |

The following diagram illustrates the flow of information through a modern Transformer encoder block, as used in materials data analysis.

Quantitative Advantages: Transformers in Action for Materials Research

The theoretical advantages of Transformers translate into tangible, measurable improvements in materials science applications. The following table compiles key performance metrics from documented use cases, demonstrating their superiority over traditional methods.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Transformer Models in Materials Science

| Application Domain | Traditional Model Performance | Transformer Model Performance | Key Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Prediction (AlphaFold) | ~60% accuracy (traditional methods) [16] | >92% accuracy [16] | Near-experimental accuracy, revolutionizing drug discovery. |

| Material Property Prediction | Reliance on feature engineering and CNNs/RNNs with higher error rates. | State-of-the-art results predicting mechanical properties of carburized steel [20]. | Directly predicts properties from multimodal data, accelerating design. |

| Molecular Discovery (e.g., BASF) | Slower, human-led discovery processes with high trial-and-error cost. | >5x faster discovery timeline; identification of novel materials with impossible properties [16]. | Uncovered subtle molecular patterns invisible to traditional analysis. |

| General Language Task (e.g., GPT-3) | N/A (Previous SOTA models) | 175 billion parameters, enabling few-shot learning [15]. | Demonstrates the scalable architecture underpinning specialized scientific models. |

Case Study: Predicting Mechanical Properties of Heat-Treated Steel

A 2025 study in Materials & Design provides a compelling experimental protocol for applying Transformers in materials science [20].

1. Research Objective: To develop a Transformer-based multimodal learning model for accurately predicting the mechanical properties (e.g., yield strength, hardness) of vacuum-carburized stainless steel based on processing parameters and material composition.

2. Experimental Dataset and Input Modalities:

- Processing Parameters: Carburizing temperature, time, atmosphere pressure.

- Material Initial State: Steel composition (C, Cr, Ni, etc.), initial microstructure.

- Post-Treatment Data: Quenching medium, tempering parameters.

- Target Outputs: Measured yield strength, tensile strength, hardness.

3. Model Architecture and Workflow:

- Step 1: Data Preprocessing and Tokenization. Numerical parameters were normalized. Microstructural images were partitioned and embedded into a sequence of patches, treated as tokens [20].

- Step 2: Multimodal Embedding. Each data modality (parameters, composition, images) was projected into a shared embedding space using separate linear layers.

- Step 3: Transformer Encoder. The combined sequence of embeddings was processed by a Transformer encoder stack utilizing self-attention to model interactions between all input features [20].

- Step 4: Property Prediction. The contextualized representation from the encoder's [CLS] token was fed into a feed-forward regression head to predict the final mechanical properties.

4. Key Reagents and Computational Tools: Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for the Steel Property Prediction Experiment

| Reagent / Tool | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Vacuum Carburizing Furnace | Creates a controlled environment for the thermochemical surface hardening of steel specimens. |

| Tensile Testing Machine | Provides ground-truth data for yield and tensile strength of the processed steel samples. |

| Hardness Tester | Measures the surface and core hardness of the heat-treated material. |

| Scanning Electron Microscope | Characterizes the microstructure (e.g., carbide distribution) of the steel before and after processing. |

| Python & PyTorch/TensorFlow | Core programming language and deep learning frameworks for implementing the Transformer model. |

| GitHub Repository | Hosts the open-source code and datasets for reproducibility [20]. |

The following workflow diagram maps the experimental and computational process described in this case study.

Implementing Transformers: A Framework for Researchers

Integrating Transformer models into a materials science research pipeline requires a structured approach. The following framework, adapted from industry best practices, outlines the key considerations [16].

The PATTERN Framework for Implementation

- P - Pattern Identification: Begin by mapping the critical, high-impact patterns in your research. What hidden relationships drive material performance? Examples include structure-property relationships in alloys or sequence-function relationships in polymers.

- A - Architecture Assessment: Evaluate your data infrastructure and computational resources. Transformer models require high-quality, curated datasets. Assess whether your data is suitable for a sequence-based or graph-based Transformer model [21].

- T - Talent Strategy: Build a team with hybrid skills combining deep domain expertise in materials science with proficiency in modern deep learning principles.

- T - Timeline Planning: Create a realistic roadmap starting with a pilot project on a well-defined, smaller-scale problem (e.g., predicting a single material property) before scaling to more complex challenges.

- E - Economic Impact Analysis: Quantify the potential ROI. Consider the value of accelerated discovery cycles, reduced physical experimentation costs, and the potential for breakthrough innovations.

- R - Risk Management: Identify risks such as data quality gaps, model interpretability challenges, and integration hurdles with existing simulation tools. Develop mitigation strategies.

- N - Network Effect Development: Build systems and model pipelines that become more valuable as they accumulate more data and recognized patterns, creating a sustainable competitive advantage.

Navigating Limitations and Future Directions

Despite their power, Transformers are not a panacea. Researchers must be aware of their limitations, including high computational costs, massive data requirements, and a fixed context window that can restrict the analysis of extremely large molecular systems [22] [15]. Ongoing architectural innovations like Grouped-Query Attention and Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) models are actively being developed to mitigate these issues, making Transformers more efficient and accessible for the scientific community [19] [17].

The transition from traditional ML and sequential models to Transformer architectures represents a fundamental leap forward for materials science and drug development. By overcoming the critical limitations of capturing long-range, complex dependencies through self-attention and parallel processing, Transformers provide a powerful, versatile framework for modeling the intricate relationships that govern material behavior. As evidenced by breakthroughs in protein folding, alloy design, and molecular discovery, the ability of these models to uncover hidden patterns in multimodal data is not merely an incremental improvement but a paradigm shift. For researchers and scientists, mastering and implementing this technology is no longer a niche advantage but an essential component of modern, data-driven scientific discovery.

The application of transformer architectures in materials science research represents a fundamental shift in how scientists represent and interrogate matter. Unlike traditional machine learning approaches that relied on hand-crafted feature engineering, foundation models leverage self-supervised pre-training on broad data to create adaptable representations for diverse downstream tasks [23]. Central to this paradigm is tokenization—the process of converting complex, structured scientific data into discrete sequential units that transformer models can process.

In natural language processing, tokenization transforms continuous text into meaningful subunits, or tokens, enabling models to learn grammatical structures and semantic relationships [24] [25]. Similarly, scientific tokenization encodes the "languages" of matter—molecular structures, protein sequences, and crystal formations—into token sequences that preserve critical structural and functional information. This approach allows researchers to leverage the powerful sequence-processing capabilities of transformer architectures for scientific discovery, from predicting molecular properties to designing novel proteins and materials [26] [27].

The challenge lies in developing tokenization schemes that faithfully represent complex, often three-dimensional, scientific structures while maintaining compatibility with the transformer architecture. This technical guide examines the cutting-edge methodologies addressing this challenge across different domains of materials science.

Tokenization Methods Across Scientific Domains

Molecular Tokenization: Bridging 2D and 3D Representations

Molecules present unique tokenization challenges due to their complex structural hierarchies. Early approaches relied on simplified string-based representations:

- SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System): Linear notation representing molecular structure as text strings using depth-first traversal of the molecular graph [26] [25]

- SELFIES (SELF-referencing Embedded Strings): Robust alternative to SMILES that guarantees molecular validity [23]

However, these 1D representations fail to capture critical 3D structural information essential for determining physical, chemical, and biological properties [26]. Advanced tokenization schemes now integrate multiple molecular representations:

Table 1: Advanced Molecular Tokenization Approaches

| Method | Representation | Structural Information | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Token-Mol [26] | SMILES + torsion angles | 2D + 3D conformational | Appends torsion angles as discrete tokens to SMILES strings |

| Regression Transformer [26] | SMILES + property tokens | 2D + molecular properties | Encodes numerical properties as tokens for joint learning |

| XYZ tokenization [26] | Cartesian coordinates | Explicit 3D coordinates | Direct tokenization of atomic coordinates |

The Token-Mol framework exemplifies modern molecular tokenization, employing a depth-first search (DFS) traversal to extract embedded torsion angles from molecular structures. Each torsion angle is assimilated as a token appended to the SMILES string, enabling the model to capture both topological and conformational information within a unified token sequence [26].

Protein Tokenization: From Sequence to Structure

Proteins require tokenization strategies that capture multiple biological hierarchies: primary sequence, secondary structure, and tertiary folding. While traditional approaches tokenize proteins using one-letter amino acid codes, this method presents significant limitations:

- Ambiguity with textual characters

- Mismatches between amino acid length and tokenized sequence length

- Inability to represent 3D structural information critical for function [27]

The ProTeX framework addresses these limitations through a novel structure-aware tokenization approach:

- Sequence Tokenization: Modified one-letter codes with special tokens for sequence regions

- Structure Tokenization: Encodes backbone dihedral angles (φ, ψ) and secondary structure elements

- All-Atom Representation: Tokenizes complete atomic-level protein geometry [27]

ProTeX employs a vector quantization technique, initializing a codebook with 512 codes to represent structural segments. The tokenizer uses a spatial softmax to assign each residue representation to a codebook entry, creating discrete structural tokens that can be seamlessly interleaved with sequence tokens in the transformer input [27].

Crystal and Materials Tokenization

Crystalline materials present additional challenges due to their periodic structures and complex compositions. Emerging approaches include:

- SLICES (Simplified Line-Input Crystal-Encoding System): String representation for solid-state materials enabling inverse design [27]

- Graph-Based Tokenization: Represents crystals as graphs with atoms as nodes and edges representing bonds or spatial relationships

- Primitive Cell Feature Tokenization: Encodes symmetry operations and unit cell parameters [23]

Table 2: Tokenization Performance Across Scientific Domains

| Domain | Representation | Vocabulary Size | Sequence Length | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small Molecules | SMILES/SELFIES | 100-1000 tokens | 50-200 tokens | Property prediction, molecular generation |

| Proteins | Amino Acid Sequence | 20-30 tokens | 100-1000+ tokens | Function prediction, structure design |

| Proteins + Structure | ProTeX | 500-1000 tokens | 200-2000 tokens | Structure-based function prediction |

| Crystals | SLICES | 100-500 tokens | 50-300 tokens | Inverse materials design |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Token-Mol: Protocol for 3D-Aware Molecular Tokenization

Objective: Implement molecular tokenization that captures both 2D topological and 3D conformational information.

Materials:

- Molecular datasets (e.g., ZINC, ChEMBL) with 3D conformer information

- Computational chemistry tools for torsion angle calculation

- Tokenization pipeline with support for numerical value tokenization

Methodology:

Molecular Graph Processing:

- Perform depth-first search (DFS) traversal of molecular graph

- Generate canonical SMILES representation

- Identify rotatable bonds and calculate torsion angles

Torsion Angle Tokenization:

- Discretize continuous torsion angles into 36 bins (10° resolution)

- Map each torsion angle to a dedicated token ID

- Append torsion tokens to SMILES sequence with special separators

Model Training:

- Implement Gaussian cross-entropy loss for numerical regression tasks

- Use causal masking with Poisson and uniform distributions

- Pre-train on large-scale molecular datasets (e.g., 400+ billion amino acids) [24]

Validation:

- Evaluate on conformation generation using root-mean-square deviation (RMSD)

- Assess property prediction accuracy on benchmark datasets

- Test pocket-based molecular generation success rates [26]

ProTeX: Protocol for Protein Structure Tokenization

Objective: Develop unified tokenization for protein sequences and 3D structures.

Materials:

- Protein Data Bank (PDB) structures

- Multiple sequence alignment databases

- Structural biology software for geometric calculations

Methodology:

Structure Encoding:

- Extract backbone atom coordinates (N, Cα, C, O)

- Calculate φ and ψ dihedral angles for each residue

- Compute inter-atomic distances and angles

Vector Quantization:

- Initialize codebook with 512 structural codes

- Encode residue-level structural features using EvoFormer architecture

- Apply spatial softmax for code assignment

Multi-Modal Sequence Construction:

- Interleave sequence tokens, structure tokens, and natural language text

- Implement special separator tokens for modality transitions

- Handle variable-length protein sequences with padding/truncation

Model Training & Validation:

- Train with next-token prediction objective on diverse protein tasks

- Evaluate on function prediction benchmarks (Gene Ontology terms)

- Test conformational generation quality using TM-score and RMSD [27]

Performance Benchmarks and Validation

Rigorous evaluation is essential for validating tokenization approaches. Key performance metrics include:

- Tokenization Efficiency: Compression rate (input size to token sequence length)

- Representational Fidelity: Reconstruction accuracy from tokens to original structure

- Downstream Task Performance: Accuracy on property prediction, structure generation, and functional annotation

Token-Mol demonstrates 10-20% improvement in molecular conformation generation and 30% improvement in property prediction compared to token-only models [26]. ProTeX achieves a twofold enhancement in protein function prediction accuracy compared to state-of-the-art domain expert models [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Implementing effective tokenization strategies requires specialized computational tools and resources. The following table details essential "research reagents" for scientific tokenization:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Scientific Tokenization

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit [25] | Cheminformatics Library | Molecular manipulation, SMILES generation, descriptor calculation | Small molecules, drug discovery |

| AlphaFold2 [27] | Protein Structure Prediction | Generates 3D structures from amino acid sequences | Protein science, structural biology |

| SentencePiece [28] | Tokenization Algorithm | Implements BPE, Unigram, and other subword tokenization | General-purpose, multi-domain |

| EvoFormer [27] | Neural Architecture | Processes multiple sequence alignments and structural information | Protein structure tokenization |

| Vector Quantization Codebook [27] | Discrete Representation | Maps continuous structural features to discrete tokens | 3D structure tokenization |

| PDBBind [25] | Database | Curated protein-ligand complexes with binding affinities | Drug discovery, binding prediction |

| ZINC/ChEMBL [23] | Molecular Databases | Large-scale collections of chemical compounds and properties | Molecular pre-training |

| TokenLearner [29] | Adaptive Tokenization | Learns to generate fewer, more informative tokens dynamically | Computer vision, video processing |

| Enoxolone aluminate | Enoxolone Aluminate|C90H135AlO12|RUO | Bench Chemicals | |

| Tunichrome B-1 | Tunichrome B-1, CAS:97689-87-7, MF:C26H25N3O11, MW:555.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Technical Implementation Considerations

Tokenization Algorithm Selection

Choosing appropriate tokenization algorithms requires careful consideration of scientific domain characteristics:

- Byte Pair Encoding (BPE): Merges most frequent token pairs, effective for SMILES and protein sequences [28]

- WordPiece: Uses likelihood-based pair selection, employed in BERT and related models [28]

- Unigram Language Model: Starts with large vocabulary and trims based on impact, used in SentencePiece [24]

- Byte-Level Processing: Uses UTF-8 bytes as tokens, eliminates out-of-vocabulary issues but increases sequence length [30]

For biological sequences, data-driven tokenizers can reduce token counts by over 3-fold compared to character-level tokenization while maintaining semantic content [24].

Handling Numerical and Structural Data

Scientific tokenization must address unique challenges in representing continuous numerical values and spatial relationships:

- Numerical Value Tokenization: Discretize continuous values into bins or use regression transformers that treat numbers as classification tasks [26]

- Spatial Relationships: Encode distances, angles, and coordinates with special positional tokens

- Invariance Requirements: Maintain SE(3) invariance for molecular structures through careful representation choices [27]

Tokenization represents a critical bridge between the complex, multidimensional world of scientific data and the sequential processing capabilities of transformer architectures. By developing specialized tokenization schemes for molecules, proteins, and materials, researchers can leverage the full power of foundation models for scientific discovery.

The most effective approaches move beyond simple string representations to incorporate rich structural information through discrete tokens, enabling models to capture the physical and chemical principles governing molecular behavior. As tokenization methodologies continue to evolve, they will play an increasingly central role in accelerating materials discovery, drug development, and our fundamental understanding of biological systems.

Future directions include developing more efficient tokenization schemes that reduce sequence length without sacrificing information, improving integration of multi-modal data, and creating unified tokenization frameworks that span across scientific domains. These advances will further enhance the capability of transformer models to reason about scientific complexity and generate novel hypotheses for experimental validation.

From Theory to Discovery: Key Applications Driving Materials Science and Drug Development

Accelerating Materials Property Prediction with Hybrid Transformer-Graph Models

The discovery and development of new functional materials are fundamental to technological progress, impacting industries from energy storage to pharmaceuticals. Traditional methods for predicting material properties, such as density functional theory (DFT),, while accurate, are computationally intensive and time-consuming, creating a significant bottleneck in the materials discovery pipeline [31]. The field has increasingly turned to machine learning (ML) to overcome these limitations. Early ML approaches utilized models like kernel ridge regression and random forests, but their reliance on manually crafted features limited their generalizability and predictive power [31] [32].

The advent of graph neural networks (GNNs) marked a significant advancement, as they natively represent crystal structures as graphs, with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges [4] [32]. Models such as CGCNN and ALIGNN demonstrated state-of-the-art performance by learning directly from atomic structures [4]. However, GNNs have inherent limitations, including difficulty in capturing long-range interactions within a crystal and a tendency to lose global structural information [4] [33].

The core thesis of this work is that Transformer architectures, renowned for their success in natural language processing, are poised to revolutionize materials science research. When hybridized with GNNs, they create powerful models that overcome the limitations of either approach alone. These hybrid models leverage the GNN's strength in modeling local atomic environments and the Transformer's self-attention mechanism to capture complex, global dependencies in material structures, thereby enabling more accurate and efficient prediction of a wide range of material properties [4] [33].

Core Architecture of Hybrid Transformer-Graph Models

The hybrid Transformer-Graph framework represents a paradigm shift in computational materials science. Its power derives from a multi-faceted architecture designed to capture the full hierarchy of interactions within a material, from local bonds to global compositional trends.

Graph Neural Network for Structural Representation

The GNN component is responsible for interpreting the atomic crystal structure. It transforms the crystal into a graph, where atoms are nodes and interatomic bonds are edges. Advanced implementations, such as the CrysGNN model, go beyond simple graphs by constructing three distinct graphs to explicitly represent different levels of interaction [4]:

- The Atom-Bond Graph (Gâ¸): A standard graph where nodes are atoms and edges represent bonds based on interatomic distances.

- The Bond-Angle Line Graph (L(Gâ¸)): This graph is created from the line graph of Gâ¸. Its nodes represent the bonds from the original graph, and its edges represent the angles between these bonds, thereby directly encoding three-body interactions.

- The Dihedral Angle Graph (L(Gâ¸d)): A higher-order line graph that further captures four-body interactions, such as dihedral angles, providing a more complete description of the local atomic environment.

These graphs are processed using an Edge-Gated Attention Graph Neural Network (EGAT), which employs gated attention blocks to update both node (atom) and edge (bond) features simultaneously. This ensures that information about bond lengths, angles, and dihedral angles is propagated and refined throughout the network [4].

Transformer for Compositional and Global Context

Operating in parallel to the structure-based GNN is a Transformer and Attention Network (TAN), such as the CoTAN model [4]. This branch takes a different input: the material's chemical composition and human-extracted physical properties.

The Transformer treats the elemental composition and associated properties as a sequence of tokens. Its self-attention mechanism computes a weighted average for each token, allowing the model to dynamically determine the importance of each element and its interactions with all other elements in the composition. This is crucial for identifying non-intuitive, complex composition-property relationships that might be missed by human experts or simpler models [4] [34].

The Hybrid Fusion and Model Interpretability

The outputs from the GNN and Transformer branches are fused into a joint representation. This hybrid representation, used by models like CrysCo, allows the model to make predictions based on a holistic understanding of the material, considering both its precise atomic arrangement and its overall chemical makeup [4].

A significant advantage of the attention mechanisms in both the EGAT and Transformer components is model interpretability. By analyzing the attention weights, researchers can determine which atoms, bonds, or elemental components the model "attends to" most strongly when making a prediction. This provides invaluable, data-driven insights into the key structural or compositional features governing a specific material property, effectively helping to decode the underlying structure-property relationships [4].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Rigorous experimental validation is crucial for establishing the performance and capabilities of hybrid Transformer-Graph models. The following protocols detail the standard methodologies used for training, evaluation, and applying these models to real-world materials science challenges.

Data Sourcing and Preprocessing

Primary Data Sources: Research typically relies on large, publicly available DFT-computed databases. The Materials Project (MP) is one of the most commonly used sources, containing data on formation energy, band gap, and other properties for over 146,000 inorganic materials [4]. For specific applications, such as predicting mechanical properties, specialized datasets from sources like Jarvis-DFT are utilized [32].

Graph Representation: The crystal structure is converted into a graph representation. A critical hyperparameter is the interatomic distance cutoff, which determines the maximum distance for two atoms to be considered connected by an edge. This cutoff must be carefully selected to balance computational cost with the inclusion of physically relevant interactions [32]. The innovative Distance Distribution Graph (DDG) offers a more efficient and invariant alternative to traditional crystal graphs by being independent of the unit cell choice [32].

Train-Validation-Test Split: The dataset is typically split into training, validation, and test sets using an 80:10:10 ratio. To ensure a fair evaluation and prevent data leakage, a stratified split is often used for properties like energy above convex hull (EHull), which can be overrepresented at zero values in databases [4].

Model Training and Transfer Learning

Loss Function and Optimization: Models are trained to minimize the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) or Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) between their predictions and the DFT-calculated target values using variants of the Adam optimizer [4] [33].

Addressing Data Scarcity via Transfer Learning: A major challenge in materials informatics is the scarcity of data for certain properties (e.g., only ~4% of entries in the Materials Project have elastic tensors). Transfer learning (TL) is a key strategy to address this [4]. The standard protocol is:

- Pre-training: A model is first trained on a "data-rich" source task, such as formation energy prediction, where hundreds of thousands of data points are available.

- Fine-tuning: The pre-trained model's weights are then used to initialize training on the "data-scarce" target task (e.g., predicting shear modulus). This approach, as seen in the CrysCoT model, regularizes the model and significantly improves performance on the downstream task compared to training from scratch [4].

Performance Evaluation and Benchmarking

Model performance is quantitatively evaluated on the held-out test set using standard regression metrics: MAE, RMSE, and the coefficient of determination (R²). The hybrid model's predictions are benchmarked against those from other state-of-the-art models, including standalone GNNs (CGCNN, ALIGNN) and transformer-based models, to demonstrate its superior accuracy [4] [33].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Hybrid Models on Standard Benchmarks

| Model | Dataset | Target Property | Performance (MAE) | Comparison Models |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CrysCo (Hybrid) [4] | Materials Project | Formation Energy (Ef) | ~0.03 eV/atom | CGCNN, SchNet, MEGNet |

| LGT (GNN+Transformer) [33] | QM9 | HOMO-LUMO Gap | ~80 meV | GCN, GIN, Graph Transformer |

| CrysCoT (with TL) [4] | Materials Project | Shear Modulus | ~0.05 GPa | Pairwise Transfer Learning |

| DDG (Invariant Graph) [32] | Materials Project | Formation Energy | ~0.04 eV/atom | Standard Crystal Graph |

Implementing and applying hybrid Transformer-Graph models requires a suite of software tools and datasets. The following table details the key components of the modern computational materials scientist's toolkit.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Hybrid Modeling

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Hybrid Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| PyTorch Geometric (PyG) [33] | Software Library | Graph Neural Network Implementation | Provides scalable data loaders and GNN layers for building the structural component of hybrid models. |

| Materials Project (MP) [4] | Database | DFT-Computed Material Properties | Primary source of training data for energy, electronic, and a limited set of mechanical properties. |

| Jarvis-DFT [32] | Database | DFT-Computed Material Properties | A key data source for benchmarking, often used alongside MP to ensure model generalizability. |

| ALIGNN [4] | Software Model | Three-Body Interaction GNN | A state-of-the-art GNN baseline; its architecture inspires the angle-based graph constructions in newer hybrids. |

| Atomistic Line Graph [4] | Representation Method | Encoding Bond Angles | Critical for moving beyond two-body interactions, forming the basis for the line graphs used in models like CrysGNN. |

| Pointwise Distance Distribution (PDD) [32] | Invariant Descriptor | Cell-Independent Structure Fingerprinting | Forms the basis for the DDG, providing a continuous and generically complete invariant for robust model input. |

Advanced Applications and Implementation Considerations

The hybrid framework's versatility allows it to be adapted to diverse prediction tasks within materials science, each with its own implementation nuances.

Application Scenarios and Workflows

The hybrid model framework can be tailored to specific prediction scenarios, each with a distinct data processing workflow.

Critical Implementation Considerations

Successfully deploying these models requires careful attention to several technical challenges:

Capturing Periodicity and Invariance: A fundamental challenge in machine learning for crystals is creating a representation that is invariant to the choice of the unit cell and periodic. The Distance Distribution Graph (DDG) addresses this by providing a generically complete isometry invariant, meaning it uniquely represents the crystal structure regardless of how the unit cell is defined, leading to more robust and accurate models [32].

Modeling High-Body Interactions: Many material properties depend on interactions that go beyond simple two-body (bond) terms. The explicit inclusion of three-body (angle) and four-body (dihedral) interactions through line graph constructions is a key innovation in frameworks like CrysGNN and ALIGNN, allowing the model to capture a more complete picture of the local chemical environment [4].

Computational Efficiency: The self-attention mechanism in Transformers has a quadratic complexity with sequence length, which can be prohibitive for large systems. Strategies such as the Local Transformer [33], which reformulates self-attention as a local graph convolution, or the use of efficient graph representations like the DDG, are essential for making these models scalable to practical high-throughput screening applications.

Hybrid Transformer-Graph models represent a significant leap forward in computational materials science. By synergistically combining the local structural precision of Graph Neural Networks with the global contextual power of Transformer architectures, they achieve superior accuracy in predicting a wide spectrum of material properties, from formation energies and band gaps to mechanically scarce elastic moduli. Their inherent interpretability, enabled by attention mechanisms, provides researchers with unprecedented insights into structure-property relationships. Furthermore, the strategic use of transfer learning effectively mitigates the critical challenge of data scarcity for many important properties. As these models continue to evolve, integrating even more sophisticated physical invariances and scaling to larger systems, they are poised to become an indispensable tool in the accelerated discovery and design of next-generation materials.

Transformer architectures have emerged as pivotal tools in scientific computing, revolutionizing how researchers process and understand complex data. Originally developed for natural language processing (NLP), their unique self-attention mechanism allows them to capture intricate, long-range dependencies in sequential data. This capability has proven exceptionally valuable in structural biology and chemistry, where the relationships between elements in a sequence—be they words in a text, amino acids in a protein, or atoms in a molecule—determine their overall function and properties [35] [36]. The application of these architectures is now accelerating innovation in drug discovery, providing powerful new methods for target identification and molecular design that leverage their ability to process multimodal data and generate novel hypotheses.

Transformer Architectures: A Technical Primer

The core innovation of the transformer architecture is the self-attention mechanism, which dynamically weighs the importance of all elements in an input sequence when processing each element. This allows the model to build a rich, context-aware representation of the entire sequence [36].

Core Architectural Components