Strategic Control of Crystal Habit: From Fundamentals to Advanced Applications in Pharmaceutical Development

This comprehensive review examines evidence-based strategies for achieving consistent crystal habit control, a critical factor influencing pharmaceutical processing and product performance.

Strategic Control of Crystal Habit: From Fundamentals to Advanced Applications in Pharmaceutical Development

Abstract

This comprehensive review examines evidence-based strategies for achieving consistent crystal habit control, a critical factor influencing pharmaceutical processing and product performance. Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, we explore how internal crystal structure and external crystallization conditions collectively determine crystal morphology. The article details practical methodologies including solvent selection, additive implementation, and supersaturation control, supported by case studies from recent literature. We further address troubleshooting common challenges like needle habit formation and present validation frameworks for characterizing modified crystals. This resource provides scientists and drug development professionals with a systematic approach to designing robust crystallization processes that enhance downstream manufacturing and therapeutic efficacy.

Understanding Crystal Habit: Why Morphology Matters in Pharmaceutical Development

Defining Crystal Habit and Its Critical Impact on Pharmaceutical Properties

FAQ: Understanding Crystal Habit

What is crystal habit and how is it different from polymorphism?

Crystal habit, often referred to as morphology, is the characteristic external shape of a crystal or an aggregate of crystals [1]. It describes the overall physical appearance, such as needles, plates, or cubes. Polymorphism, in contrast, refers to different internal crystal structures (packing arrangements) of the same chemical compound [2]. A single polymorph can be grown to exhibit multiple habits, and a specific habit can be observed in different polymorphs.

Why is controlling crystal habit critical in pharmaceutical development?

Crystal habit is a critical Critical Quality Attribute (CQA) because it directly influences a wide range of properties essential for manufacturing and drug performance [3] [4]. More than 90% of small-molecule Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) are produced in crystalline forms, making habit control paramount [4].

| Affected Area | Impact of Crystal Habit |

|---|---|

| Downstream Manufacturing | Influences flowability, blend uniformity, compressibility during tableting, filtration efficiency, and bulk density [3] [4]. |

| Drug Product Performance | Affects the dissolution rate and solubility, which are key determinants of bioavailability for BCS Class II drugs [4] [5]. |

| Stability & Handling | Needle-like (acicular) crystals are often friable (break easily), difficult to handle, and can cause issues like filter blockage [4]. |

FAQ: Common Experimental Issues & Troubleshooting

We keep getting a needle-like habit that is causing filtration and flow problems. How can we modify this?

The needle-like (acicular) habit is notorious for causing downstream processing issues [4]. The general strategy is to modify the growth rates of different crystal faces to move towards a more equant (blocky) or tabular (plate-like) habit. The following table summarizes the primary in-situ modification strategies [4].

| Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Typical Experimental Levers |

|---|---|---|

| Solvent Selection | Different solvents interact uniquely with various crystal faces, altering their surface energy and growth rates [4] [5]. | Test solvents with different polarity, viscosity, and hydrogen bonding capacity. |

| Use of Additives / Habit Modifiers | Additives selectively adsorb onto specific crystal faces, inhibiting their growth and thus changing the crystal's overall shape [4]. | Introduce tailor-made additives, impurities, or polymers during crystallization. |

| Controlling Supersaturation | The level of supersaturation (the driving force for crystallization) can change the relative growth rates of different faces [4]. | Modulate the cooling rate in cooling crystallization or the antisolvent addition rate. |

| Modulating Temperature & pH | Temperature affects solubility and growth kinetics. pH can alter the ionization state of the molecule, affecting its interaction with solvents and surfaces [4]. | Perform crystallization at different isothermal temperatures or a controlled cooling profile. Adjust pH to a region where the API is stable. |

Our crystal habit changes unpredictably between batches. What could be the cause?

Inconsistent crystal habit typically points to poorly controlled crystallization parameters. Key factors to investigate are [4]:

- Minor impurity profiles: Trace impurities from raw materials or solvents can act as unintended habit modifiers.

- Fluctuations in supersaturation: Inconsistent cooling or antisolvent addition rates lead to different nucleation and growth environments.

- Slight variations in solvent composition: For mixed-solvent systems, small changes in ratio can significantly impact habit.

- Inadequate seeding: Using seeds of inconsistent quality, quantity, or habit.

How can we be sure that we've only changed the habit and not the polymorphic form?

This is a crucial consideration. You must confirm that the internal structure remains unchanged. This requires a combination of physicochemical characterization techniques [3] [5]:

- Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD): The primary tool for confirming polymorphic form. Identical PXRD patterns for different habits confirm the same internal structure [5].

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC): Should show the same thermal events (e.g., melting point) for different habits of the same polymorph [5].

- Spectroscopic Techniques: FTIR or Raman spectroscopy can provide supporting evidence of identical molecular conformation and packing.

Experimental Protocol: Solvent-Based Habit Modification

This protocol provides a methodology for generating different crystal habits of an API by screening different solvent systems, as demonstrated for Sorafenib Tosylate [5].

1. Objective: To produce at least two distinct crystal habits (e.g., plate-like and needle-like) of a target API via solvent selection.

2. Materials & Reagents:

| Item | Function/Justification |

|---|---|

| High-Purity API | Ensure starting material is consistent and pure to avoid confounding effects from impurities. |

| Solvents (e.g., Acetone, n-Butanol) | Selected for differing polarity, viscosity, and surface affinity to manipulate crystal growth kinetics [5]. |

| Heating Mantle & Oil Bath | For controlled heating to dissolve the API. |

| Round-Bottom Flasks | For the crystallization vessel. |

| Magnetic Stirrer & Stir Bars | To ensure uniform concentration and temperature. |

| Vacuum Filtration Setup | For isolating the final crystals. |

| Microscope with Camera | For initial visual assessment and imaging of crystal habit. |

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Saturation - For each solvent (e.g., acetone and n-butanol), add a known quantity of the API to a round-bottom flask. Heat the suspension while stirring until a clear, saturated solution is achieved.

- Step 2: Crystallization - Slowly cool the saturated solutions to room temperature at a controlled, consistent rate (e.g., 0.5°C per minute). Alternatively, allow the solutions to stand undisturbed for slow evaporation.

- Step 3: Isolation - Once crystallization is complete, isolate the crystals by vacuum filtration.

- Step 4: Drying - Dry the harvested crystals under vacuum at ambient temperature to remove residual solvent without inducing phase transformations.

- Step 5: Characterization - Image the crystals from each condition using microscopy. Characterize the solid form using PXRD and DSC to confirm identical polymorphic form.

Analytical Toolkit for Crystal Habit Characterization

A multi-technique approach is essential for comprehensive characterization of crystal habit [3].

| Technique | Primary Function |

|---|---|

| Optical/Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) | Provides direct visual information on crystal size, shape, and morphology. |

| Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD) | Confirms the internal crystal structure (polymorph) and can indicate preferred orientation. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Assesses purity and polymorphic form through melting point and other thermal events. |

| Face Indexation | Determines the Miller indices of the crystal faces observed by microscopy, linking external form to internal structure [5]. |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | Probes the surface chemistry of different crystal faces, revealing variations in hydrophilicity [5]. |

| F1063-0967 | F1063-0967, MF:C24H24N2O5S2, MW:484.6 g/mol |

| Tyrosinase-IN-40 | Tyrosinase-IN-40, MF:C34H29N9O10, MW:723.6 g/mol |

Case Study: Impact of Sorafenib Tosylate Crystal Habit on Dissolution

A 2021 study clearly demonstrated the critical impact of crystal habit on performance [5].

- Two Habits Generated: Plate-shaped (ST-A) from acetone and Needle-shaped (ST-B) from n-butanol.

- Same Polymorph: PXRD and DSC confirmed both habits were the same internal polymorphic form.

- Surface Analysis: Molecular modeling and XPS revealed the needle-shaped crystals (ST-B) had a larger proportion of hydrophilic surfaces.

- Performance Outcome: The needle-shaped crystals (ST-B) with the more hydrophilic surface exhibited a higher dissolution rate and a substantial enhancement in in vivo pharmacokinetic performance compared to the plate-shaped habit (ST-A).

This case underscores that for BCS Class II drugs like Sorafenib Tosylate, crystal habit modification can be a powerful strategy to enhance bioavailability without altering the chemical or polymorphic form.

The Fundamental Mechanisms of Crystal Growth and Habit Formation

For researchers and drug development professionals, controlling the crystal habit of an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) is not merely an academic exercise—it is a critical step in ensuring manufacturability, stability, and therapeutic performance. Crystal habit, defined as the external shape of a crystal, is governed by the relative growth rates of its different faces [6]. Over 90% of small-molecule APIs are produced as crystalline solids, making habit control an essential aspect of pharmaceutical process development [4].

The habit of a crystal profoundly impacts nearly every aspect of pharmaceutical processing and performance. Needle-like crystals (acicular habit) are particularly problematic, known to cause filter blockage during processing, exhibit poor flowability, and demonstrate low compactibility during tableting [4]. Different crystal habits can significantly alter key pharmaceutical properties including bulk density, wettability, slurry stability, and ultimately, the bioavailability of the drug substance [4] [7]. For instance, a study on a tumor-necrosis factor related apoptosis-inducing ligand demonstrated that crystal habit directly influenced its antitumor activity [4]. Consequently, developing robust strategies for consistent crystal habit control represents a fundamental research objective with direct implications for drug product quality and performance.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Crystal Growth and Habit Formation

The Crystal Growth Process

Crystal growth from solution occurs through a sequence of molecular processes often referred to as the Kossel model [4]. These steps include:

- Bulk transport of solute molecules from the solution to the crystal face.

- Surface diffusion of adsorbed solute molecules across the crystal surface.

- Desolvation of both the crystal growth site and the solute molecules.

- Attachment of solute molecules into the crystal lattice through non-covalent bonds.

The final crystal habit is determined by the relative growth rates of different crystal faces. Faces with slower growth rates typically become more prominent in the final crystal morphology [6]. This differential growth is influenced by both the internal crystal structure and external environmental factors.

Factors Governing Crystal Habit

Multiple process variables can be modulated to control crystal habit by affecting face-specific growth rates:

- Supersaturation Level ((S = C/C^*)): Higher supersaturation often promotes faster growth and can lead to more needle-like habits for many organic crystals [4] [8].

- Solvent Selection: Solvent-surface interactions significantly modulate growth rates through differential binding to various crystal faces [4] [9].

- Habit Modifiers (Additives): Impurities or additives can selectively adsorb to specific crystal faces, inhibiting their growth and altering morphology [4] [8].

- pH: pH changes can affect the ionization state of API molecules, thereby altering solute-solvent and solute-crystal surface interactions [4].

- Temperature Profile: Cooling rate during crystallization impacts both nucleation and growth kinetics [4].

- External Stresses: Ultrasound application can generate secondary nucleation, affecting crystal size and habit [4].

Troubleshooting Guides for Common Crystal Growth Challenges

Frequently Encountered Problems and Solutions

Table 1: Common crystal growth problems and their solutions

| Problem | Root Cause | Recommended Solution | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Crystal Growth [10] | Unsaturated solution; Contamination; Incorrect temperature | Add more solute until saturation; Use purified solute and distilled water; Adjust temperature | Test for saturation before starting; Use clean containers and tools |

| No Seed Crystals [10] | Lack of nucleation sites | Pour small solution amount into shallow dish to evaporate; Use rough string for nucleation | Ensure proper saturation; Control evaporation rate |

| Seed Crystals Dissolve [10] | New solution not fully saturated | Dissolve more solute into liquid; Allow evaporation to concentrate solution; Chill solution | Verify saturation before adding seeds; Let solution stabilize thermally |

| Excessive Nucleation (Many Small Crystals) [4] | Too high supersaturation; Rapid cooling | Control cooling rate precisely; Use slightly undersaturated solutions for seeding | Implement controlled cooling profiles; Use accurate saturation point data |

| Needle-like Habit [4] [8] | Anisotropic growth favoring one direction | Use habit-modifying additives; Change solvent system; Adjust supersaturation | Screen solvents and additives early; Model crystal morphology |

Advanced Troubleshooting: Needle-like Crystal Formation

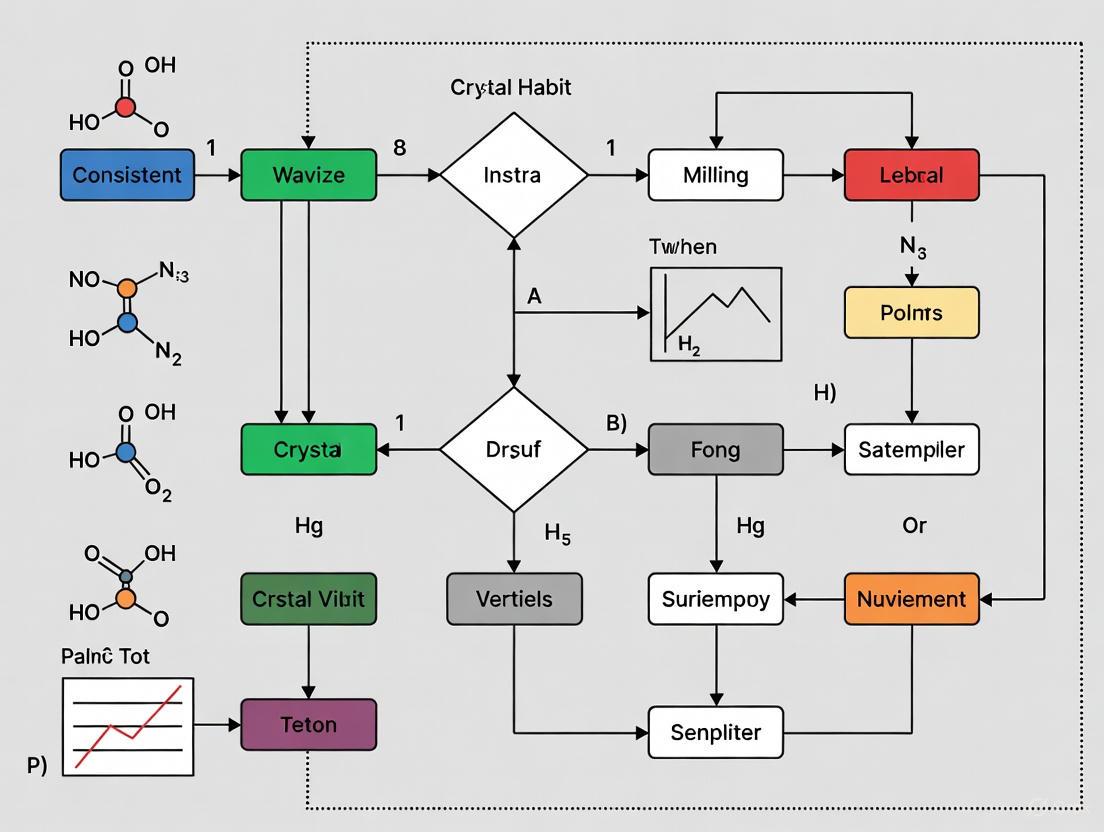

The formation of needle-like crystals represents a particularly common and challenging issue in pharmaceutical crystallization. The following decision pathway provides a systematic approach to address this problem:

Systematic approach to address needle-like crystal formation

Experimental Protocols for Crystal Habit Modification

Protocol 1: Solvent-Mediated Habit Modification

Objective: Modify crystal habit through strategic solvent selection [9].

Materials:

- API compound (pure)

- High-purity solvents (various polarities)

- Crystallization vessels

- Temperature control system

- Particle imaging system (e.g., Crystalline PV/RR system [9])

Procedure:

- Prepare saturated solutions of the API in different pure solvents and solvent mixtures at elevated temperature (e.g., 40-60°C).

- Use anti-solvent addition or cooling to generate supersaturation.

- Maintain solutions at constant temperature with gentle stirring.

- Monitor crystal growth in situ using particle imaging.

- Isolate crystals and characterize habit using microscopy.

- Correlate solvent properties (polarity, hydrogen bonding capacity, surface tension) with observed crystal habits.

Expected Outcomes: Different solvent systems will yield varying crystal habits due to differential solvent-surface interactions. For example, ascorbic acid transitions from cubical/prismatic crystals in water to elongated prisms in methanol/ethanol and needle-like forms in isopropanol [9].

Protocol 2: Additive-Mediated Habit Modification

Objective: Use selective habit modifiers to control crystal morphology [8].

Materials:

- API compound (e.g., Vitamin B1, Isoniazid)

- Potential habit modifiers (surfactants, polymers, ions)

- Crystallization platforms

- Analytical tools (SEM, XRD, Raman spectroscopy)

Procedure:

- Prepare a saturated solution of the API in a selected solvent.

- Add varying concentrations of habit modifiers (e.g., 0.1-1.0% w/w).

- Induce crystallization through cooling or anti-solvent addition.

- Monitor crystallization kinetics using in situ tools.

- Characterize crystal habit using microscopy and image analysis.

- Employ molecular modeling to understand additive-surface interactions.

Expected Outcomes: Selective inhibition of specific crystal faces. For example, sodium alkylsulfate (SDS) and sodium alkyl benzenesulfonate (SDBS) can modify Vitamin B1 from long rod to block habit by preferentially adsorbing to and inhibiting growth along the axial direction [8].

Protocol 3: Crystal Regeneration Studies

Objective: Understand crystal growth mechanisms through regeneration of deliberately damaged crystals [11].

Materials:

- Single crystals of API (e.g., aceclofenac)

- Controlled cleavage apparatus

- Supersaturated solutions

- Optical microscopy with time-lapse capability

Procedure:

- Grow high-quality single crystals of the target compound.

- Identify cleavage planes through structural analysis.

- Carefully cleave crystals along predetermined planes.

- Introduce cleaved crystals into supersaturated solutions.

- Monitor regeneration process through time-lapse microscopy.

- Characterize the regeneration kinetics and morphology.

Expected Outcomes: Crystals will preferentially regenerate along the broken faces, restoring their original morphology before further growth occurs. This demonstrates the role of surface energy in driving crystal growth processes [11].

Research Reagent Solutions for Crystal Habit Control

Table 2: Key reagents for crystal habit modification studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Habit Control | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solvents [9] | Water, methanol, ethanol, isopropanol, acetone, ethyl acetate | Modulate surface interactions and growth kinetics | Binary solvent systems often provide optimal habit control; consider solvent parameters |

| Surfactants [8] | SDS, SDBS, CTAB, Tween 80 | Selective adsorption to specific crystal faces | Concentration and alkyl chain length critically impact effectiveness |

| Polymers [11] | HPMC, PVP, PEG | Steric hindrance and surface blocking | Molecular weight and functional groups determine face selectivity |

| Ionic Additives [8] | Metal ions, counterions, salts | Alter electrostatic interactions at crystal surfaces | Particularly effective for ionic APIs; consider pH effects |

| Acid/Base Modifiers [12] | HCl, NaOH, alum | Adjust pH to control ionization and supersaturation | Alum addition increases acidity and creates sharper, more pointed crystal shapes |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do my crystals consistently form as needles, and how can I achieve more block-like morphology? A: Needle-like morphology results from highly anisotropic growth, where one direction grows much faster than others. To achieve block-like crystals: (1) Reduce supersaturation to moderate growth rates, (2) Introduce habit-modifying additives that selectively adsorb to the fast-growing faces, (3) Change solvent system to alter surface energy, (4) For aceclofenac, specific solvents like ACT and MA can promote different aspect ratios [11].

Q2: How can I quantitatively monitor crystal habit in real-time during crystallization? A: Several in-line analytical tools are available: (1) Particle View Imaging with AI-based analysis provides direct visualization and shape distribution data [9], (2) Laser diffraction measures particle size distribution but with limited shape information, (3) Raman spectroscopy can track polymorphic form changes that may accompany habit modifications [4].

Q3: What is the minimum crystal size required for structural analysis? A: Modern laboratory X-ray diffractometers can analyze crystals as small as 0.1 × 0.1 × 0.1 mm, with synchrotron sources capable of analyzing even smaller crystals. For a typical organic compound with molecular weight ~200 g/mol, a 0.3 mm crystal contains approximately 0.051 mg of material [13].

Q4: How do impurities affect crystal habit, and how can I control this? A: Impurities can drastically alter crystal habit through several mechanisms: (1) Selective adsorption to specific crystal faces, inhibiting their growth, (2) Incorporation into the crystal lattice, distorting growth patterns, (3) Altering solution properties such as surface tension or viscosity. Control strategies include purification of starting materials, use of specific additives to counteract impurity effects, and optimization of crystallization conditions to minimize impurity incorporation [4] [10].

Q5: Can crystal habit affect the dissolution rate and bioavailability of my API? A: Yes, crystal habit significantly impacts pharmaceutical properties. Different crystal habits present different surface areas to the dissolution medium, affecting dissolution rate. For instance, a needle-like crystal with high surface area may dissolve faster than a compact block-like crystal of the same mass. This directly influences bioavailability, making habit control critical for product performance [4] [7].

Integrated Workflow for Systematic Crystal Habit Control

Successful crystal habit control requires an integrated approach that combines multiple strategies:

Integrated workflow for systematic crystal habit control

This workflow emphasizes the iterative nature of crystal habit optimization, where results from each stage inform subsequent experiments. Modern approaches combine experimental screening with computational modeling to increase efficiency and fundamental understanding [8].

Within the broader thesis on strategies for consistent crystal habit control, understanding the direct impact of crystal habit on key pharmaceutical properties is fundamental. The external shape, or habit, of an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient's (API) crystals is not merely a physical attribute; it is a critical quality parameter that directly influences the efficiency of downstream manufacturing processes and the therapeutic performance of the final drug product. This guide addresses common challenges and questions researchers face in controlling crystal habit to optimize filterability, flowability, and bioavailability.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does crystal habit directly influence the filterability of an API slurry? Crystal habit dictates the packing density and porosity of a filter cake. Needle-like (acicular) crystals typically form dense, tightly packed cakes with high surface area and small interstitial spaces, severely restricting the flow of mother liquor and leading to prolonged filtration times and potential filter blockage [4]. In contrast, equidimensional crystals, such as cubes or blocks, pack into a more porous cake, allowing liquid to pass through freely and significantly improving filtration efficiency [4].

Q2: Why do some crystal powders have poor flowability, and how can habit modification help? Poor flowability is often a direct consequence of irregular crystal shapes, such as needles or thin plates, which promote interparticle friction, mechanical interlocking, and bridge formation in hoppers and feeders [4]. Modifying the habit to a more uniform, spherical, or equidimensional shape reduces these interactions. This improves the powder's flow properties, which is essential for consistent die-filling during tablet compression, ensuring uniform tablet weight and drug content [4] [7].

Q3: What is the mechanistic link between an API's crystal habit and its bioavailability? Bioavailability depends on the drug's dissolution rate in the gastrointestinal fluid. The crystal habit influences the surface-to-volume ratio and the relative exposure of specific crystal faces with different surface energies and dissolution rates [4]. A habit with a higher surface area (e.g., thin plates or needles) will typically dissolve faster than a compact, low-surface-area crystal of the same polymorph, potentially leading to a higher initial absorption rate [4] [7]. Therefore, controlling habit is a powerful lever to modulate the dissolution rate and, consequently, bioavailability.

Q4: Can a change in crystal habit induce a polymorphic transformation? While habit modification and polymorphic control are distinct concepts, the processes used to modify habit can sometimes lead to unintended form changes. Certain solvents, additives, or supersaturation levels can stabilize a different polymorphic form, which comes with its own distinct internal structure and properties [4]. It is crucial to monitor both the external habit (morphology) and the internal form (polymorph) throughout any habit modification study to ensure the desired crystal structure is maintained.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Filtration Efficiency

Symptoms: Slow filtration rates, clogged filters, wet filter cakes, extended process times.

Root Cause: Typically, the formation of needle-like or thin, plate-like crystals.

Solutions:

- Modify Solvent System: Switch to a solvent or solvent mixture that promotes growth in all dimensions. The affinity between the solvent and different crystal faces can selectively inhibit or promote growth, encouraging a more block-like habit [4] [8].

- Use a Habit-Modifying Additive: Introduce a tailor-made additive that selectively adsorbs onto the fast-growing faces of the needle crystal. For example, certain surfactants like SDS and SDBS have been shown to inhibit axial growth, transforming a rod-like habit into a block-like one [4] [8].

- Optimize Supersaturation: High supersaturation often favors needle growth. Implement a controlled cooling or antisolvent addition profile to maintain a lower, more uniform supersaturation level that promotes isotropic growth [4].

Problem 2: Poor Powder Flowability

Symptoms: Powder bridging in hoppers, inconsistent tablet weight, poor content uniformity, difficulties in automated powder handling.

Root Cause: Irregular, anisotropic crystal habits (needles, plates) with poor flow characteristics.

Solutions:

- Spherical Crystallization: Employ techniques like spherical agglomeration to form near-spherical agglomerates of primary crystals. These agglomerates have excellent flow and compression properties due to their rounded shape [8].

- Optimize Crystallization Parameters: Adjust parameters such as cooling rate, agitation intensity, and the use of specific additives to discourage the formation of fragile, elongated crystals and promote the growth of more robust, equidimensional particles [4] [14].

- Implement a Post-Crystallization Milling Step: While not an in-situ method, milling can be used to break up long needles. However, this can generate excessive fines and may induce form transformation, so it is less desirable than direct habit control [4].

Problem 3: Low and Variable Dissolution Rate

Symptoms: Failure to meet dissolution specifications, high variability in bioavailability.

Root Cause: A crystal habit with low specific surface area or with dominant faces that have low intrinsic dissolution rates.

Solutions:

- Engineer a High-Surface-Area Habit: Direct the crystallization towards a habit with a higher surface-to-volume ratio, such as thin plates or small needles, to increase the contact area with the dissolution medium [4] [7].

- Control the Supersaturation Profile: The level of supersaturation during crystallization impacts both nucleation and growth rates, which in turn determines the final crystal size and shape. Precise control can help achieve a consistent, high-surface-area product [4].

- Leverage Solvent Effects: Select a solvent that results in a crystal habit where the most hydrophilic faces are dominantly exposed. These faces typically interact more readily with water, enhancing the dissolution rate [4].

Table 1. Impact of Crystal Habit on Key Pharmaceutical Properties

| Crystal Habit | Filterability | Flowability | Dissolution Rate | Bulk Density |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Needle (Acicular) | Very Poor [4] | Very Poor [4] | High (due to high surface area) [4] [7] | Low [4] |

| Plate-like | Poor | Poor | Moderate to High [4] | Low |

| Block-like | Good [4] | Good [4] | Moderate | High [4] |

| Cubic | Excellent | Excellent | Lower (due to low surface area) | High |

| Spherical | Good | Excellent [8] | Tunable | High |

Experimental Protocols for Habit Modification

Protocol 1: Solvent Screening for Habit Modification

Objective: To identify a solvent system that produces the desired crystal habit. Methodology:

- Saturation: Prepare saturated solutions of the API in a range of pure solvents and solvent mixtures (e.g., alcohols, esters, ketones, water) at a constant elevated temperature [4] [14].

- Crystallization: Induce crystallization using a consistent method, such as slow cooling or isothermal solvent evaporation, across all samples.

- Analysis: Isolate the crystals and characterize the habit using optical microscopy or Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). Compare the shapes obtained from different solvents. Key Parameters: Solvent polarity, hydrogen bonding capacity, and molecular structure, which all affect solute-solvent interactions and relative face growth rates [4].

Protocol 2: Using Additives as Habit Modifiers

Objective: To selectively inhibit the growth of specific crystal faces using additives. Methodology:

- Additive Selection: Select potential habit modifiers (e.g., ionic surfactants like SDS, polymers, or other structurally similar impurities) based on their potential to interact with specific functional groups on the crystal surface [4] [8].

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a series of supersaturated solutions of the API in a chosen solvent. Add varying low concentrations (e.g., 0.1-1.0% w/w) of the selected additives to these solutions.

- Crystallization and Monitoring: Carry out crystallization under controlled conditions. Use in-situ tools like Particle Vision Microscopy (PVM) to monitor real-time habit development [4].

- Characterization: Analyze the final crystal products using microscopy and PXRD to confirm habit change and the absence of polymorphic transformation.

Research Workflow and Property Relationships

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 2. Essential Research Reagents for Crystal Habit Modification

| Reagent/Material | Function in Habit Modification | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Solvents (Various Polarity) | Medium for crystallization; solute-solvent interactions selectively inhibit or promote face growth rates. | Screening alcohols, esters, water to transform needle-like crystals into blocks [4]. |

| Ionic Surfactants (e.g., SDS) | Act as habit modifiers by selectively adsorbing to specific crystal faces via electrostatic and hydrogen bonding, inhibiting their growth. | Modifying Vitamin B1 from long rods to blocks by inhibiting axial growth [8]. |

| Polymers & Additives | Act as tailor-made inhibitors or promoters for specific crystal faces, altering the crystal's external shape. | Used to control the aspect ratio and prevent needle formation in various APIs [4]. |

| Seeds | Provide a controlled surface for crystal growth, helping to manage supersaturation and ensure consistent habit. | Used in controlled cooling crystallizations to ensure the desired habit is reproduced batch-to-batch [14]. |

| In-situ Analytical Probes | Enable real-time monitoring of crystal habit and size without the need for sample removal. | Using Particle Vision Microscopy (PVM) to track habit development during a crystallization process [4]. |

| Lantanose A | Lantanose A, MF:C30H52O26, MW:828.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Abz-GIVRAK(Dnp) | Abz-GIVRAK(Dnp), MF:C41H61N13O12, MW:928.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Special Challenge of Needle-Shaped Crystals and Downstream Processing Issues

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why are needle-shaped crystals particularly problematic in drug development? Needle-shaped crystals, characterized by their high aspect ratio, are problematic because they lead to poor bulk powder properties. They typically result in low bulk density, challenging powder flow, and broad, variable particle size distributions. These properties can cause issues in downstream processing, such as poor filtration performance, segregation in powder blends, and inconsistent compaction behavior during tablet manufacturing [15].

Q2: What particle engineering strategies can transform needle-like crystals into more processable forms? A primary strategy is spherical agglomeration, often integrated with other techniques like high shear wet milling (HSWM). This combined approach can convert delicate needle-like crystals into robust, spherical agglomerates. These agglomerates have improved density, flowability, and handling properties, making them more suitable for direct compression and other downstream processes. The agglomerate size can be controlled, often targeting sizes below 300 µm for pharmaceutical applications [16] [15].

Q3: Besides agglomeration, what other methods can help control crystal habit? A systematic framework for crystal shape tuning is effective. This includes [17]:

- Controlled Temperature Cycling: Repeatedly cycling the temperature to promote crystal dissolution and re-growth in a more favorable habit.

- Use of Shape Modification Additives: Introducing specific additives (e.g., polymers like polypropylene glycol) that selectively interact with certain crystal faces to inhibit needle-like growth.

- Seeding and Wet Milling: Using high-quality seeds and applying wet milling at the process start to generate secondary nuclei, providing more uniform growth sites and enhancing control over the final crystal size and shape.

Q4: Is this technology scalable from laboratory to production? Yes, processes like spherical agglomeration coupled with high shear wet milling have been successfully scaled. Studies demonstrate scalability from 250 mL laboratory vessels to 5 L production-scale agitated stirred-tanks, consistently achieving target agglomerate sizes (e.g., 35 µm, 80 µm, and 145 µm) with minimal residual solvent content and good flow performance [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Powder Flow and Low Bulk Density

Root Cause: The primary issue is the physical shape of needle-like crystals, which interlock and resist smooth flow, while also packing inefficiently, leading to low bulk density [15].

Solutions:

- Implement Spherical Agglomeration: Introduce an immiscible bridging liquid during crystallization to bind primary needle crystals into dense, spherical agglomerates. This transforms particle morphology, drastically improving flow and density [15].

- Optimize the Agglomeration Process: Use a multivariate Design-of-Experiment (DoE) approach to optimize key process parameters:

- Bridging Liquid to Solids Ratio (BSR): Critical for forming robust agglomerates.

- Bridging Liquid Addition Time: Controls the agglomeration kinetics.

- High Shear Wet Milling Speed: Helps control the initial primary particle and droplet size, enabling the formation of smaller, more uniform agglomerates [16] [15].

- Ensure Proper Agitation During Drying: After isolation, use agitation in filter dryers to prevent agglomerate breakage and attrition, preserving the improved properties. Studies indicate that over 225 impeller revolutions during drying can maintain product quality [16].

Problem: Batch-to-Batch Inconsistency in Particle Size Distribution (PSD)

Root Cause: Uncontrolled agglomeration during crystallization and sensitivity of needle-like crystals to mechanical stresses during handling [15].

Solutions:

- Employ Controlled Seeding: Use deagglomerated seeds of consistent quality and ensure their uniform dispersion, potentially via a wet milling step, to provide a consistent starting point for crystal growth [15].

- Integrate In-Process Size Control: Incorporate a high shear wet mill inline with the crystallizer or agglomerator to continuously control the particle size in real-time, breaking down large, friable agglomerates and ensuring a consistent, narrow PSD [16] [15].

- Control Agitation with CFD: Use Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations to ensure mixing intensity and flow patterns are consistent and scalable across different vessel sizes, minimizing another source of variability [15].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: Spherical Agglomeration with High Shear Wet Milling

This protocol is designed to transform a needle-like Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) into spherical agglomerates of controlled size [16] [15].

1. Objective To consistently produce robust spherical agglomerates with a median size below 300 µm, improved bulk density, and enhanced flowability.

2. Materials and Equipment

- API: Needle-like crystals (e.g., D50 ~ 2.6 µm).

- Dispersing Liquid: Distilled water.

- Bridging Liquid: A solvent immiscible with water and with high affinity for the API (e.g., Dichloromethane, Ethyl Acetate). Selected via initial screening.

- Equipment: High shear wet mill, agitated stirred-tank vessels (scale from 250 mL to 5 L), an agitated filter dryer, and analytical tools for Particle Size Analysis (PSD).

3. Procedure Step A: Initial Suspension Preparation

- Create a suspension of the API in the dispersing liquid (water) at a ratio of approximately 1:15 (w/w API-to-water).

- Begin mixing the suspension in the agitated vessel.

Step B: Integrated Milling and Agglomeration

- Pass the suspension through a high shear wet mill to control the initial size of the primary particles.

- While under agitation, add the selected bridging liquid gradually. The addition time and flow rate are key DoE variables.

- Continue agitation to allow the immersion mechanism to occur, where bridging liquid droplets capture and engulf primary particles, forming spherical agglomerates.

Step C: Isolation and Drying

- Transfer the agglomerated slurry to an agitated filter dryer.

- Isolate the wet agglomerates and begin the drying process under controlled agitation. A study suggests a minimum of 225 impeller revolutions (approximately 5 hours of drying) is sufficient to achieve acceptable product quality without excessive breakage [16].

4. Key Process Parameters to Optimize (DoE Approach) A multivariate Design-of-Experiment should be used to understand the impact of the following critical parameters [16]:

- Bridging Liquid Addition Time

- Bridging Liquid to Solids Ratio (BSR)

- High Shear Wet Milling Speed

The table below summarizes target outcomes from a scaled spherical agglomeration process.

Table 1: Target Agglomerate Properties from an Optimized Process

| Property | Target Range | Scale Demonstrated | Key Influencing Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median Agglomerate Size (D50) | 30 - 300 µm | 250 mL to 5 L | High Shear Wet Milling Speed & BSR [16] |

| Bulk Density | Significant improvement over needle-like crystals | Laboratory Scale | Successful agglomeration and spherical shape [15] |

| Powder Flowability | Good flow performance | Laboratory Scale | Spherical shape and controlled size [16] |

| Residual Solvent | Minimal content | 250 mL to 5 L | Proper drying and isolation [16] |

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials used in the featured particle engineering experiments.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Particle Engineering

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Bridging Liquid (e.g., DCM) | An immiscible solvent that selectively wets the API particles, forming liquid bridges between them to bind primary crystals into agglomerates [15]. |

| Dispersing Liquid (e.g., Water) | The continuous phase in which the crystallization and agglomeration occur; it must be immiscible with the bridging liquid [15]. |

| High Shear Wet Mill | A piece of equipment used to apply intense mechanical energy to break down primary particles and control the initial particle size before and during agglomeration [16] [15]. |

| Polymer Additives (e.g., PPG-4000) | A shape modification additive that can adsorb onto specific crystal faces during growth to inhibit needle-like morphology and promote more equidimensional crystal growth [17]. |

Process Visualization

Workflow for Solving Needle-Shaped Crystal Challenges

This diagram illustrates the strategic pathways and technologies available to address issues caused by needle-shaped crystals.

Spherical Agglomeration with High Shear Wet Milling

This diagram details the specific workflow for the integrated agglomeration and milling process.

Core Concepts: Internal Structure and Habit Formation

FAQ: What determines the inherent crystal habit of a compound? The inherent crystal habit is primarily governed by the internal crystal structure, which dictates the arrangement of molecules and the relative growth rates of different crystal faces. Faces with lower surface energies grow more slowly and become more prominent in the final crystal morphology. The equilibrium shape a crystal would adopt in a vacuum can be predicted using the Wulff construction, which minimizes the total surface energy for a given volume [18].

FAQ: How do kinetic and thermodynamic growth regimes influence crystal habit? Crystal growth can occur in two distinct regimes, leading to different shapes [18]:

- Thermodynamic Regime: Characterized by low supersaturation, high temperatures, and long aging times. Under these conditions, molecules have sufficient time to diffuse to the most energetically favorable lattice positions. This results in compact, isotropic crystal shapes that represent the global energy minimum.

- Kinetic Regime: Characterized by high supersaturation, low temperatures, and short aging times. Molecules are added to the crystal structure faster than they can rearrange. This often leads to the formation of anisotropic shapes (like needles or plates) because growth occurs more rapidly at high-energy faces, such as corners.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Crystal Habit Modification

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unexpected Needle-Like Habit | Excessive supersaturation driving kinetic growth [4]. | Reduce the cooling rate or antisolvent addition rate to lower supersaturation [4]. |

| Solvent-surface interactions that preferentially inhibit certain faces [19]. | Screen different solvents or use binary solvent mixtures [9] [4]. | |

| Poor Filtration or Filter Blockage | Formation of fine, needle-like crystals creating a dense, low-porosity filter cake [4]. | Modify habit to a more compact or equant shape using additives or solvent selection [7] [4]. |

| Inconsistent Crystal Habit Between Batches | Uncontrolled or fluctuating supersaturation profile during crystallization. | Implement precise control of temperature and antisolvent addition rates. Use in-process monitoring [4]. |

| Variation in solvent composition or impurity profile. | Ensure consistent raw material sourcing and solvent purity. | |

| Sticking During Tableting | Crystal habit with large, flat faces leading to high contact area [7]. | Modify habit to a more spherical or irregular shape to reduce punch face contact [7]. |

| Slow Dissolution Rate | Crystal habit with low specific surface area, reducing contact with the dissolution medium. | Engineer crystals with a higher aspect ratio or smaller size to increase surface area [20]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Solvent-Mediated Habit Modification

This protocol is adapted from a case study on controlling the crystal habit of ascorbic acid [9].

- Objective: To systematically investigate the effect of water-alcohol binary solvent mixtures on crystal habit.

- Materials:

- Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) or compound of interest.

- Solvents: Water, and a series of alcohols (e.g., methanol, ethanol, isopropanol).

- Crystallization reactors (e.g., Crystalline PV/RR system or equivalent round-bottom flasks with controlled stirring and temperature).

- In-line particle imaging camera or microscope for offline analysis.

- Method:

- Prepare binary solvent mixtures by adding alcohol (component 2) to water (component 1) at varying mole fractions (e.g., xâ‚‚ = 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0).

- Saturate each solvent mixture with the API at an elevated temperature.

- Perform cooling crystallization using a consistent cooling rate (e.g., 0.5 °C/min) from the saturation temperature to a final low temperature.

- Use in-line imaging or offline microscopy to capture crystal images and determine the resulting crystal habit in each solvent system.

- Expected Outcome: The crystal habit will transition with changing solvent composition. For example, ascorbic acid changes from cubical/prismatic in pure water to elongated prisms in pure methanol/ethanol and needles in pure isopropanol [9].

Protocol 2: Additive-Mediated Habit Modification

This protocol is based on methods used to modify the habit of energetic materials like PYX and is directly applicable to pharmaceuticals [4] [19].

- Objective: To use polymeric additives to suppress needle-like growth and produce crystals with a lower aspect ratio.

- Materials:

- API.

- Appropriate solvent (e.g., DMSO, DMF).

- Additives: Polymers such as Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP K30) or Polyethylene Glycol (PEG 4000).

- Method:

- Dissolve the API in the primary solvent at an elevated temperature.

- Prepare a separate solution containing a low concentration (e.g., 0.1-1.0% w/w) of the habit-modifying additive in the same solvent.

- Add the additive solution to the API solution before initiating crystallization.

- Perform cooling or antisolvent crystallization under controlled conditions.

- Isulate the crystals by filtration and characterize the habit using microscopy.

- Expected Outcome: Additives like PVP or PEG can selectively adsorb to specific growing crystal faces, inhibiting their growth. This results in a habit change from needles to more equant or plate-like crystals, significantly improving flowability and compaction properties [19].

Workflow and Logic Diagrams

Crystal Habit Modification Workflow

Troubleshooting Logic for Needle Formation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Crystal Habit Control Research

| Category | Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Solvents | Water-Alcohol Mixtures (Methanol, Ethanol, Isopropanol) | To modify the solvation environment and surface energy of different crystal faces, leading to habit changes [9]. |

| Dipolar Aprotic Solvents (DMSO, DMF, DMA) | Often used for APIs with low solubility; can significantly alter crystal habit by strong specific interactions [19]. | |

| Additives | Polymers (PVP K30, PEG 4000) | Bulky molecules that adsorb to specific crystal faces to inhibit growth, effective in reducing aspect ratio of needle-like crystals [19]. |

| Surfactants (Tween 80, Span 20) | Can reduce interfacial tension and selectively adsorb to crystal surfaces, modifying growth rates and habit [19]. | |

| Process Aids | Antisolvents (Water, n-Hexane, Diethyl Ether) | Added to reduce API solubility and induce supersaturation; choice of antisolvent can impact the resulting crystal habit [21]. |

| Analytical Tools | In-line Particle Imaging Camera | Provides real-time, in-process monitoring of crystal size and shape (PSSD) without risk of cross-contamination [9]. |

| Raman Spectroscopy Probe | Used in-line to monitor solute concentration and identify polymorphic form simultaneously with habit changes [9] [4]. | |

| Asticolorin B | Asticolorin B, MF:C33H28O7, MW:536.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Matlystatin A | Matlystatin A, MF:C22H40N4O5, MW:440.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Proven Techniques for Crystal Habit Modification: From Solvent Selection to Advanced Engineering

Strategic Solvent Selection Based on Molecular-Level Interactions

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental mechanism by which a solvent changes crystal shape? The crystal shape (habit) is determined by the relative growth rates of different crystal faces. Solvents directly modulate these growth rates by interacting with specific crystal surfaces. Strong, specific solvent-surface interactions, such as hydrogen bonding, can inhibit the growth of a face by blocking the attachment of solute molecules. Weaker, non-specific interactions typically result in faster growth of that face. The anisotropic nature of these interactions across different crystal faces leads to distinct final morphologies [22] [23].

FAQ 2: How do I select a solvent to target a specific crystal habit, like reducing aspect ratio? Targeting a specific habit requires understanding the molecular structure of your compound's different crystal faces. To reduce aspect ratio (make crystals less needle-like), you should identify solvents that selectively inhibit the growth of the fast-growing faces. For example, if a compound has functional groups capable of hydrogen bonding exposed on its fast-growing faces, selecting a solvent with complementary hydrogen-bonding ability (e.g., a hydrogen bond acceptor for a hydrogen bond donor surface) can slow down that face's growth. Experimental data from nifedipine shows that solvents with higher hydrogen bond acceptor abilities, like ethyl acetate, can lead to higher aspect ratios, while solvents like toluene and ethanol produce more equant crystals [22].

FAQ 3: My chosen solvent is not producing the expected crystal form. What could be wrong? This is a common issue. First, verify that you have not accidentally stabilized a solvate (a crystal form that includes solvent molecules within its structure). Second, consider that the solvent may be influencing the crystallization pathway kinetically, leading to a metastable polymorph. The solvent can alter the energy barrier for nucleation of different forms. Characterize your product with techniques like PXRD to identify the form you have obtained. Using a supramolecular gel matrix like an FmocFF organogel in your solvent can sometimes provide a different confinement environment that unlocks the desired polymorph [24].

FAQ 4: Are there computational tools to predict solvent effects before lab experiments? Yes, computational methods are increasingly powerful for pre-screening solvents. Protocols like CrystalClear can predict crystal growth from solution by calculating the free energies of interaction between solute and solvent molecules, providing parameters for Monte Carlo growth simulations [25]. Other approaches use molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and metadynamics to study the energetic cost of molecule attachment/detachment at crystal surfaces in different solvents, providing insights into growth kinetics at the molecular level [26]. Data-driven platforms like SolECOs also use machine learning to predict solubility and sustainability for a wide range of solvent-API pairs [27].

FAQ 5: Why do I sometimes see needle-like crystals, and how can I prevent them? Needle-like morphology results from one direction growing much faster than the others. This often occurs when the solvent interacts strongly with all faces except the fast-growing one, offering little to no growth inhibition on that face. To prevent needles, you need to identify a solvent that can interact with the specific chemistry of the fast-growing face. This might involve a solvent with a molecular structure or functional group that can adsorb onto that face. Alternatively, using a binary solvent mixture or a gel-mediated crystallization approach can help modify the diffusion-limited growth that often promotes needle formation [25] [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Uncontrolled Needle-Like Crystal Formation

Symptoms: Crystals are excessively long and thin, leading to poor filtration, handling, and flow properties. Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: The solvent has no specific interaction with the fast-growing face.

- Solution: Switch to a solvent with functional groups capable of interacting with the chemical moieties present on the fast-growing face. Computational surface chemistry analysis can help identify these moieties [28].

- Cause 2: Excessively high supersaturation, promoting diffusion-limited growth and instability at the crystal tips.

- Solution: Carefully control the supersaturation profile by reducing the cooling rate or antisolvent addition rate. Consider using a temperature-cycling program to promote Ostwald ripening [25].

- Cause 3: Convective currents in the solution promoting one-dimensional growth.

- Solution: Use a gel-mediated crystallization system. The FmocFF organogel, for example, creates a diffusion-dominated environment that suppresses convection and can promote more isotropic growth [24].

Problem: Inconsistent Crystal Habit Between Batches

Symptoms: The crystal shape varies from one experiment to another using the same nominal solvent and conditions. Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Small variations in impurity profile or solvent water content.

- Solution: Strictly control solvent source, purity, and storage conditions. Use solvents with the highest available purity and ensure equipment is thoroughly dried.

- Cause 2: Uncontrolled nucleation, leading to different growth histories of individual crystals.

- Solution: Implement seeded crystallization. By adding pre-formed seeds of the desired morphology, you control the nucleation event and promote consistent growth across all crystals.

- Cause 3: Slight fluctuations in temperature or agitation rate.

- Solution: Standardize and meticulously document all process parameters, including the agitation speed and the exact cooling profile. Automated lab reactors can provide this level of control.

Problem: Failure to Obtain the Desired Polymorph

Symptoms: The crystalline product is always the stable polymorph, not the targeted metastable form with better properties. Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: The solvent stabilizes the nucleation of the more stable form.

- Solution: Screen a wider range of solvents with different properties (polarity, hydrogen bonding, dielectric constant). The solvent can dramatically alter the nucleation kinetics of different polymorphs [24].

- Cause 2: The energy barrier for nucleating the metastable form is too high in solution.

- Solution: Employ a templating strategy. FmocFF organogels have been shown to provide a unique solid interface that can selectively template metastable polymorphs, such as the ambient-temperature isolation of nilutamide Form II, by epitaxial matching [24].

- Cause 3: The process conditions always drive the system into the stable region of the polymorph.

- Solution: Explore a different crystallization technique, such as anti-solvent crystallization with rapid mixing, to create a high supersaturation that favors the metastable form.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Key Experimental Protocol: Investigating Solvent-Surface Interactions via Molecular Dynamics

This protocol, adapted from studies on ibuprofen, allows for the in silico screening of solvents by calculating the work of defect formation on crystal surfaces [26].

System Setup:

- Software: Use molecular dynamics software like GROMACS.

- Crystal Structure: Obtain your API's crystal structure from the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD).

- Surface Preparation: Generate crystal slabs exposing the morphologically dominant facets (e.g., {100}, {002}) using crystal visualization software (e.g., VESTA).

- Solvation: Solvate each crystal slab in a box of solvent molecules using the simulation software's utilities. Ensure the slab thickness and solvent volume prevent periodic image interactions.

Force Field Selection:

- Apply a suitable force field (e.g., Generalized Amber Force Field - GAFF) for the API and solvents. Obtain parameters for solvent molecules from established databases.

Simulation & Calculation:

- Use Well-Tempered Metadynamics (WTmetaD) to simulate the removal of a single molecule from a perfect crystal surface into the solution. This models the reverse of growth and probes the solvent's inhibitory effect.

- Collective Variables (CVs): Define three CVs to bias the simulation:

- Coordination Number: Between the target molecule and other solute molecules.

- Distance: The distance of the molecule from the crystal surface.

- Alignment Angle: The molecular orientation relative to its crystal configuration.

- Analysis: The resulting free energy profile gives the work of defect formation. A higher work value indicates the solvent more strongly stabilizes the crystal surface, likely leading to growth inhibition on that facet [26].

Quantitative Solvent Effect Data

The following table summarizes experimental data for nifedipine, demonstrating how solvent properties directly influence crystal habit. Aspect Ratio (AR) is used as a quantitative measure of crystal shape [22].

Table 1: Solvent Effect on Nifedipine Crystal Habit and Aspect Ratio

| Solvent | Hydrogen Bonding Profile | Aspect Ratio (AR) | Observed Crystal Habit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethyl Acetate | Acceptor | 6.6 | Rod-like |

| Acetone | Acceptor | 4.0 | Rod-like |

| Acetonitrile | Acceptor | N/A | Shuttle-like |

| Toluene | None | 2.1 | Equant, Block-like |

| Ethanol | Donor & Acceptor | 2.1 | Equant, Block-like |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Materials for Solvent Screening and Habit Control Experiments

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Solvent Library | A diverse collection of solvents covering a range of polarities (e.g., water, ethanol, acetonitrile, toluene, ethyl acetate, chloroform). Essential for empirical screening of solvent effects on solubility and habit [22] [27]. |

| Low-Molecular-Weight Gelator (LMWG - FmocFF) | A versatile gelator that forms organogels in various solvents. Used to create a confined, diffusion-controlled environment for crystallization, which can suppress needle growth and access metastable polymorphs [24]. |

| Computational Software (e.g., GROMACS, CrystalGrower) | Enables molecular dynamics simulations and crystal growth modeling to predict solvent effects and morphologies in silico before lab work, saving time and resources [25] [26]. |

| X-ray Transparent Microfluidic Chips | High-throughput devices for setting up numerous nanoliter-scale crystallization trials with minimal material. Allow for in situ X-ray analysis, avoiding crystal harvesting damage [29]. |

| Jatrophane 4 | Jatrophane 4, MF:C39H52O14, MW:744.8 g/mol |

| Tyrosinase-IN-31 | Tyrosinase-IN-31, MF:C20H21N3O3S, MW:383.5 g/mol |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Crystal Habit Control Strategy

Molecular-Level Solvent Interaction Mechanism

Harnessing Additives and Habit Modifiers for Targeted Face Inhibition

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Needle Crystal Formation

Problem: Predominant formation of undesirable needle-shaped (acicular) crystals, leading to poor filterability, low bulk density, and difficult handling [30] [4].

| Troubleshooting Step | Action Details | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Evaluate Solvent System | Switch to a solvent with different polarity. Test less polar solvents (e.g., hexane, ethyl acetate) or aqueous buffers with different pH [30] [4]. | Alters relative growth rates of crystal faces, potentially suppressing needle habit [4]. |

| 2. Introduce a Habit Modifier | Add a small, controlled concentration (e.g., 0.1-1.0% w/w) of a polymeric growth inhibitor like Polysorbate-80 or a hydrophobic polymer [30] [4]. | Additive adsorbs onto fast-growing faces, inhibiting their growth and reducing aspect ratio [30] [31]. |

| 3. Optimize Supersaturation | Lower the initial supersaturation (S) by reducing cooling rate or adjusting anti-solvent addition rate. Aim for moderate S [4] [32]. | Shifts balance from nucleation-dominated (fines/needles) to growth-dominated (uniform crystals) [32]. |

| 4. Implement Seeding | Introduce pre-formed seeds of the desired crystal habit at the point of metastable zone entrance [32]. | Provides a template for growth, guiding crystallization towards the target morphology [32]. |

Guide 2: Managing Polymorphic Transformation During Habit Modification

Problem: Habit modification strategy inadvertently induces an unwanted polymorphic transformation, compromising API stability [32] [3].

| Troubleshooting Step | Action Details | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Characterize Initial Solid Form | Use PXRD and DSC to confirm the starting polymorph before habit modification experiments [3]. | Establishes a baseline for comparison. |

| 2. Analyze Solvent-Compatibility | Consult solvent parameters and screen solvents that are known to stabilize the desired polymorph [4] [32]. | Prevents solvent-mediated transformation during crystallization. |

| 3. Use Polymorph-Specific Seeds | Seed the crystallization with crystals of the desired polymorph and the target habit [32]. | Simultaneously controls both crystal form and external shape. |

| 4. Control Process Kinetics | Avoid rapid cooling or anti-solvent addition, which can create local high supersaturation favoring unwanted polymorphs [32]. | Maintains growth conditions within the stable zone of the desired polymorph. |

Guide 3: Overcoming Additive-Induced Agglomeration

Problem: The use of habit modifiers leads to excessive agglomeration or formation of fine particles, complicating filtration [30] [32].

| Troubleshooting Step | Action Details | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Optimize Additive Concentration | Perform a concentration gradient study. High concentrations can over-stabilize fine particles or bridge crystals [32] [31]. | Identifies a concentration window that modifies habit without causing agglomeration. |

| 2. Modify Addition Protocol | Add the habit modifier solution slowly and at a different stage (e.g., pre- or post-nucleation) [32]. | Ensures uniform distribution and prevents localized over-dosing. |

| 3. Adjust Agitation Rate/Profile | Increase agitation to break up agglomerates, but avoid excessive shear that may fracture crystals [32]. | Improves mass transfer and reduces particle bridging. |

| 4. Combine with Temperature Cycling | Implement a few cycles of heating and cooling after initial crystallization [30] [4]. | Promotes Ostwald ripening, redissolving fines and strengthening crystal structure. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental mechanism by which a habit modifier acts? Habit modifiers, typically polymers or surfactants, function by selectively adsorbing onto specific crystal faces. This adsorption impedes the growth of those faces by creating a energy barrier or physically blocking the attachment of solute molecules. The faces with adsorbed inhibitor grow more slowly relative to other faces, thereby changing the crystal's external shape or habit [4] [31].

FAQ 2: How do I select a suitable habit modifier for my API? Selection is often empirical, but the following strategies are recommended:

- Literature Review: Identify modifiers used for structurally similar compounds.

- Mechanistic Hypothesis: For a hydrophobic crystal face, use a hydrophobic polymer; for a charged surface, use an ionic surfactant or polymer.

- High-Throughput Screening: Utilize 96-well plates or other micro-formats to screen a wide range of additives (e.g., polymers, surfactants, ionic liquids) at different concentrations alongside solvent variations [30] [4].

FAQ 3: Can crystal habit truly impact the final drug product's performance? Yes, significantly. Crystal habit influences a range of critical properties:

- Downstream Processing: Needle crystals can block filter pores, reduce flowability, and fracture, creating fines. Platy or equant crystals typically offer better filtration and handling [30] [4] [3].

- Product Performance: The surface area-to-volume ratio, which varies with habit, can affect dissolution rate and, consequently, bioavailability [4] [3].

- Mechanical Properties: Habit impacts bulk density, compactibility, and tabletability [30] [3].

FAQ 4: Why is solvent selection so critical for habit modification? The solvent interacts differently with various crystal faces based on surface chemistry and molecular structure. A solvent that strongly binds to a particular face will slow its growth relative to others, effectively modifying the habit. This is why a compound like ibuprofen forms needles in low-polarity solvents but more equant crystals in water-acetone mixtures [4].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: Salting-Out Crystallization with Habit Modification

This protocol is adapted from a study on vancomycin HCl [30].

1. Objective: To produce octahedral vancomycin crystals via salting-out crystallization, avoiding the typical needle habit.

2. Materials (Research Reagent Solutions):

| Reagent / Solution | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Vancomycin HCl (USP grade) | Model Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) [30]. |

| Acetate Buffer (e.g., 0.1 M, pH 4.5) | Solvent system providing a controlled pH environment [30]. |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | Salting-out agent, reduces API solubility [30]. |

| Polymeric Habit Modifier (e.g., INITIA 585) | Additive to selectively inhibit the growth of needle-promoting crystal faces [31]. |

| Ethanol or Acetone | Anti-solvent / Washing solvent [30]. |

3. Workflow Diagram:

4. Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve vancomycin HCl in acetate buffer to a known concentration below its saturation solubility at room temperature [30].

- Additive Introduction: Add a selected habit modifier (e.g., 0.5% w/w relative to API) to the solution under gentle stirring until fully dissolved.

- Crystallization Induction: Gradually add solid sodium chloride to the solution with constant agitation. Continue addition until the solution becomes turbid, indicating the onset of nucleation.

- Crystal Growth: Continue incubation with stirring for 4-24 hours. Regularly sample a droplet of slurry for optical microscopy analysis to monitor crystal habit and size.

- Harvesting: Isolate the crystals by vacuum filtration. Wash the cake with a small volume of cold ethanol or acetone to remove residual mother liquor and salt.

- Characterization: Dry the crystals under vacuum. Characterize the final habit using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), confirm polymorphic form with Powder X-Ray Diffraction (PXRD), and analyze thermal behavior with Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) [3].

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from literature on the impact of habit modification.

| API / Compound | Modification Strategy | Key Performance Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vancomycin HCl | Salting-out crystallization in acetate buffer (pH 4.5) at room temperature. | Needle habit avoided; octahedral crystals obtained with improved filterability and handling. | [30] |

| Lovastatin | Use of less polar solvents (hexane, ethyl acetate) or addition of hydrophobic polymers. | Lower aspect ratio (less needle-like) crystals achieved. | [30] [4] |

| Nifedipine | Addition of Polysorbate-80 surfactant. | Suppression of needle habit formation. | [30] |

| Griseofulvin | Addition of poly(sebacic anhydride). | Suppression of needle habit formation. | [30] |

| Calcite | Addition of INITIA 585 polymer additive. | Abnormal crystal shape and size due to modified lattice growth. | [31] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent Category | Example(s) | Primary Function in Habit Modification |

|---|---|---|

| Polymeric Inhibitors | Hydrophobic polymers, Polysorbate-80, Poly(sebacic anhydride), INITIA polymers | Selectively adsorb to fast-growing crystal faces, reducing their growth rate and aspect ratio [30] [31]. |

| Solvent Systems | Aqueous buffers, Acetone, Ethyl acetate, Hexane, Dichloromethane | Modulate solute-solvent interactions and surface energy of different crystal faces, influencing relative growth rates [30] [4] [21]. |

| Salting-Out Agents | Sodium Chloride (NaCl), Ammonium Sulfate | Reduce solubility of the API in an aqueous system, inducing crystallization while potentially influencing habit [30]. |

| Anti-Solvents | Water, Heptane, Diethyl ether | Added to a solution to decrease API solubility, controlling supersaturation generation and crystal growth [21] [32]. |

| NCGC00351170 | NCGC00351170, MF:C18H14N2O6, MW:354.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| BDM88951 | BDM88951, MF:C23H23N5O5S2, MW:513.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guides

Why is my cooling crystallization yielding poor crystal size distribution, and how can I fix it?

| Problem Cause | Diagnostic Signs | Corrective Action | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excessively rapid cooling [33] [34] | Crystallization initiates immediately upon cooling; crystals form rapidly as a solid mass. | - Reduce the cooling rate. [33]- Re-dissolve solid and add 1-2 mL extra solvent per 100 mg solid to exceed the minimum solvent needed. [33] | Rapid cooling generates high, uncontrolled supersaturation, leading to excessive primary nucleation. Slower cooling and reduced supersaturation promote dominant crystal growth over nucleation. [33] [34] |

| Insufficient or ineffective mixing | Wide variation in crystal size; inconsistent product quality. | - Optimize agitator speed and design to ensure uniform supersaturation and temperature throughout the crystallizer. | Poor mixing creates localized zones of high supersaturation, promoting unwanted nucleation. Uniform mixing ensures consistent conditions for controlled growth. [35] |

| Incorrect seeding practice | Poor crystal size distribution (CSD) despite controlled cooling. | - Introduce seeds at a temperature slightly above the saturation point. [36]- Ensure seeds are of consistent quality and are added at the optimal supersaturation level. | Seeds provide designated growth sites, consuming supersaturation and suppressing spontaneous nucleation. Proper seeding is critical for controlling the final CSD. [36] |

Experimental Protocol for Optimizing Cooling Crystallization:

- Determine Solubility Curve: Measure the solubility of your compound in the chosen solvent across a relevant temperature range.

- Determine Metastable Zone Width (MSZW): Conduct polythermal experiments to find the temperature difference between the solubility and supersolubility curves. A wider MSZW allows for more operational flexibility. [36]

- Develop Cooling Profile: Based on the MSZW, design a cooling profile that maintains the solution within the metastable zone. This often involves an initial slow cooling period to avoid nucleation, followed by a controlled cooling rate to promote growth. [35]

- Seeding: At a temperature within the metastable zone, add a predetermined amount of high-quality seed crystals to initiate controlled growth.

My antisolvent crystallization results in excessive fines and oiling out. What steps should I take?

| Problem Cause | Diagnostic Signs | Corrective Action | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| High localized supersaturation during antisolvent addition | Formation of oil (amorphous precipitate) or a large number of fine crystals; wide CSD. | - Switch from batch addition to controlled, gradual addition of antisolvent. [36]- Implement Membrane-Assisted Antisolvent Addition for superior control. [36] | A high local concentration of antisolvent causes a sudden, drastic drop in solubility, generating an explosive nucleation event. Controlled addition distributes supersaturation more evenly. [36] |

| Poor mixing efficiency | Agglomeration, inconsistent crystal habit, and broad CSD. | - Improve agitator design and placement.- Use a membrane to introduce antisolvent as microscopic droplets, creating a large, uniform interfacial area for highly efficient mixing. [36] | Inefficient mixing creates pockets of high supersaturation ratio. Membrane dispersion achieves mixing at the microscale, promoting a uniform supersaturation environment. [36] |

| Incompatible solvent-antisolvent system | Oiling out or gum-like formation instead of crystalline solid. | - Screen different antisolvents.- Adjust the solvent-to-antisolvent ratio to find a composition where crystallization is favored over amorphous precipitation. | The compound has low solubility and high kinetic drive to precipitate in the mixture, but the molecules cannot orient into a crystal lattice quickly enough. A different solvent environment can slow the process, allowing for ordered crystallization. |

Experimental Protocol for Membrane-Assisted Antisolvent Crystallization (MAAC): [36]

- Apparatus Setup: Use a hollow fiber membrane module as the interface between the feed solution and the antisolvent. A pump is used to control the flow and pressure of the antisolvent.

- Saturation: Prepare a solution of the compound in a solvent at a known concentration and temperature.

- Controlled Addition: Pump the antisolvent through the membrane's microscopic pores. This creates a fine, uniform dispersion of antisolvent into the bulk solution, enabling precise control over the generation of supersaturation.

- Nucleation & Growth: The uniform supersaturation leads to more simultaneous nucleation and consistent crystal growth.

- Isolation: Filter, wash, and dry the resulting crystals.

How can I control crystal habit and prevent needle-like crystals during crystallization?

| Problem Cause | Diagnostic Signs | Corrective Action | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inherent crystal structure | Needle-like (acicular) or plate-like crystals, which are difficult to filter and handle. | - Employ habit modifiers: Add a specific additive that selectively adsorbs onto certain crystal faces, inhibiting their growth and modifying the final shape. [4] | The final crystal habit is determined by the relative growth rates of different crystal faces. A habit modifier binds more strongly to fast-growing faces, slowing their growth and allowing other faces to develop. [4] |

| Solvent selection | Crystal habit changes significantly with different solvents. | - Screen solvents: Perform crystallization in different solvent or binary solvent mixtures (e.g., water-alcohol). [9] [4] | Different solvents have varying surface affinity and interaction energies with different crystal faces, altering their relative growth rates and thus the final crystal morphology. [9] [4] |

| High supersaturation level | Promotes the formation of needles or other undesirable, unstable habits. | - Control supersaturation: Lower the cooling or antisolvent addition rate to reduce the supersaturation driving force. [4] | High supersaturation can favor the kinetic growth form (often needles) over the thermodynamic form. Lower supersaturation allows for more equilibrium-like, well-defined crystal development. [4] |

Experimental Protocol for Crystal Habit Modification via Solvent Screening: [9]

- Preparation: Create binary solvent mixtures (e.g., water with methanol, ethanol, or isopropanol) at varying molar ratios (e.g., 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0 mole fraction of alcohol). [9]

- Crystallization: Dissolve the compound in each solvent system at an elevated temperature. Use a controlled cooling rate (e.g., 0–20 °C/min) in a multiple-reactor system like the Crystalline PV/RR to ensure consistency. [9]

- In-line Monitoring: Use integrated imaging cameras (Particle View) to capture real-time crystal shape and size changes during the process. [9]

- Analysis: Compare the crystal habits (e.g., prism, needle, plate) obtained from the different solvent systems to select the one that yields the desired morphology. [9]

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the most critical parameter to monitor for consistent supersaturation control?

The most critical parameters are temperature profile for cooling crystallization and antisolvent addition rate for antisolvent crystallization. Both directly and instantaneously impact the supersaturation level, which is the primary driver for both nucleation and crystal growth. Fluctuations in these parameters cause inconsistent supersaturation, leading to poor reproducibility in crystal size and habit. [35] Advanced process analytical technology (PAT) tools, such as in-line turbidity probes or particle vision microscopes, are recommended for real-time monitoring of supersaturation. [9] [36]

Q2: Why do my crystals not form at all after cooling or adding antisolvent?