Solution-Based vs. Vapor-Phase Crystal Growth: A Comparative Analysis for Advanced Materials and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of solution-based and vapor-phase single crystal growth techniques, critical for developing high-purity materials for pharmaceuticals, optoelectronics, and research.

Solution-Based vs. Vapor-Phase Crystal Growth: A Comparative Analysis for Advanced Materials and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of solution-based and vapor-phase single crystal growth techniques, critical for developing high-purity materials for pharmaceuticals, optoelectronics, and research. We explore fundamental principles, thermodynamic mechanisms, and key methodologies including antisolvent vapor-assisted crystallization, inverse temperature crystallization, chemical vapor deposition, and thermal evaporation. The review systematically addresses common challenges like defect formation and stoichiometric control, offering optimization strategies guided by machine learning and advanced simulation. A direct performance comparison evaluates crystallinity, scalability, and cost-effectiveness, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a validated framework for selecting optimal crystal growth techniques for specific biomedical and clinical applications.

Fundamental Principles of Crystal Growth: Thermodynamics, Kinetics, and Nucleation Mechanisms

In the fields of materials science and drug development, the solid form of a material is a critical determinant of its properties and performance. Crystalline solids are fundamentally categorized by their structural integrity: single crystals, with a continuous and unbroken lattice, and polycrystalline materials, comprised of numerous smaller crystallites, or grains, fused together at interfaces known as grain boundaries [1] [2]. This article provides a comparative analysis of these two structural forms, framing the discussion within ongoing research on solution-based and vapor-phase crystal growth techniques. The presence or absence of grain boundaries is a simple structural distinction with profound implications for a material's physical, mechanical, and functional properties, influencing everything from the efficiency of a solar panel to the stability and efficacy of a pharmaceutical product [3] [4].

Fundamental Structural Differences

The Ideal Order of Single Crystals

A single crystal, as the name implies, is a solid body in which the crystal lattice is continuous and uninterrupted to the edges of the material, with no grain boundaries. Its defining feature is the long-range periodic order of its atomic or molecular constituents [4]. This perfect uniformity means that the orientation of the lattice is consistent throughout the entire volume of the crystal. Single crystals are typically grown from a single nucleation site under carefully controlled conditions that allow atoms or molecules to add to the lattice in a regular, repeating pattern [5].

The Complex Reality of Polycrystalline Materials

In contrast, polycrystalline materials are aggregates of many small single crystals, known as grains, which are typically microscopic in size. These grains are joined together at grain boundaries, which are two-dimensional defects where crystals of different orientations meet [1] [2]. The atomic structure at these boundaries is highly disrupted and disordered compared to the perfect lattice within the grains [2]. Polycrystals form naturally when crystallization begins from multiple nucleation sites in a melt or solution; the individual crystals grow until they impinge on one another, resulting in a complex network of grains and boundaries [2].

The Nature of Grain Boundaries

Grain boundaries are characterized by several parameters, but a key distinction is the misorientation angle between adjacent grains. Low-angle grain boundaries (LAGB), with a misorientation less than about 15 degrees, are composed of an array of dislocations. High-angle grain boundaries (HAGB), with misorientation greater than about 15 degrees, have a more complex and disordered structure [1]. The energy of a grain boundary is generally higher than that of the perfect crystal lattice, and these interfaces are preferred sites for the onset of corrosion, the precipitation of new phases, and the segregation of impurities [1].

Comparative Analysis of Material Properties

The fundamental structural difference between single-crystalline and polycrystalline materials manifests in divergent physical, mechanical, and chemical properties. The following table summarizes these key differences.

Table 1: Property Comparison of Single-Crystalline and Polycrystalline Materials

| Property | Single-Crystalline Materials | Polycrystalline Materials |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Order | Continuous, unbroken lattice with long-range order [4]. | Aggregation of misoriented grains separated by boundaries [1] [2]. |

| Electrical & Thermal Conductivity | Higher due to minimal electron/phonon scattering at defects [1]. | Reduced due to scattering at grain boundaries [1]. |

| Mechanical Strength | Softer and more ductile (for metals). | Harder and stronger at room temperature (Hall-Petch relationship) [1]. |

| Chemical Stability | More uniform surface properties; often higher chemical stability. | Grain boundaries are preferred sites for corrosion and chemical attack [1]. |

| Optical Properties | Uniform and predictable. | Scattering at boundaries can reduce transparency and create non-uniform appearance [4]. |

The Critical Role of Grain Boundaries

The properties of polycrystalline materials are dominated by the behavior of their grain boundaries. While they can strengthen a material (as described by the Hall-Petch relationship), they also disrupt the motion of electrons and phonons, decreasing electrical and thermal conductivity [1]. Furthermore, their disordered nature and high energy make them chemically reactive, acting as pathways for corrosion or sites for unwanted phase precipitation [1]. In functional materials like batteries, the high surface area of grain boundaries in polycrystalline particles can exacerbate side reactions, such as gas production, which degrades performance over time [6].

Experimental Data and Performance Metrics

Quantitative data from various industries underscores the performance gap stemming from structural differences.

Table 2: Performance Metrics in Solar Photovoltaic and Battery Applications

| Application | Metric | Single-Crystalline | Polycrystalline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solar Panels (c. 2025) | Typical Conversion Efficiency | 18% - 22% (over 25% with TOPCon, HJT) [7] | 13% - 16% [7] |

| Solar Panels (c. 2025) | Temperature Coefficient | Slightly better (smaller output loss at high temps) [4] | Slightly worse on average [4] |

| Sodium-Ion Batteries (NFM111 Cathode) | Cycling Performance | Can be poorer due to large volume changes from phase transitions, leading to cracking [6] | Can be worse due to gas production from reactions at grain boundaries [6] |

| General Aesthetics | Visual Appearance | Uniform dark color [4] [7] | Speckled blue color with visible grain patterns [4] [7] |

The data reveals that the superiority of one form over the other is often application-dependent. In solar energy, single crystals' superior efficiency and aesthetics have made them the dominant technology [7]. In energy storage, the picture is more complex: single-crystalline cathode materials may suffer from bulk fractures during cycling, while polycrystalline materials may degrade faster due to reactions at the boundaries of their primary particles [6].

Crystal Growth Methodologies: Solution vs. Vapor Phase

The formation of either single or polycrystalline solids is governed by the chosen growth technique and its parameters. Both solution and vapor-phase growth aim to achieve a state of supersaturation, the driving force for crystallization [5].

Solution-Based Crystal Growth

This method involves dissolving the solute in a solvent and then creating supersaturation, typically by cooling, evaporation, or an anti-solvent effect [5]. A key challenge is morphological instability; a projecting element on a crystal surface grows faster because it encounters a region of higher solute concentration, which can lead to dendritic growth or hopper crystals if not controlled by growth kinetics [5]. Solution growth is often preferred for materials with high melting points or those that decompose upon melting, as it allows for growth at much lower temperatures, potentially resulting in crystals with fewer defects [5].

Vapor-Phase Crystal Growth

In vapor-phase growth, a material is transported via the vapor phase to a seed crystal under conditions of supersaturation. This technique is particularly useful for materials with high vapor pressures at their growth temperatures [5]. It allows for precise control over the growth environment, often leading to high-purity crystals, but can be slower and more complex than solution growth from a technological standpoint.

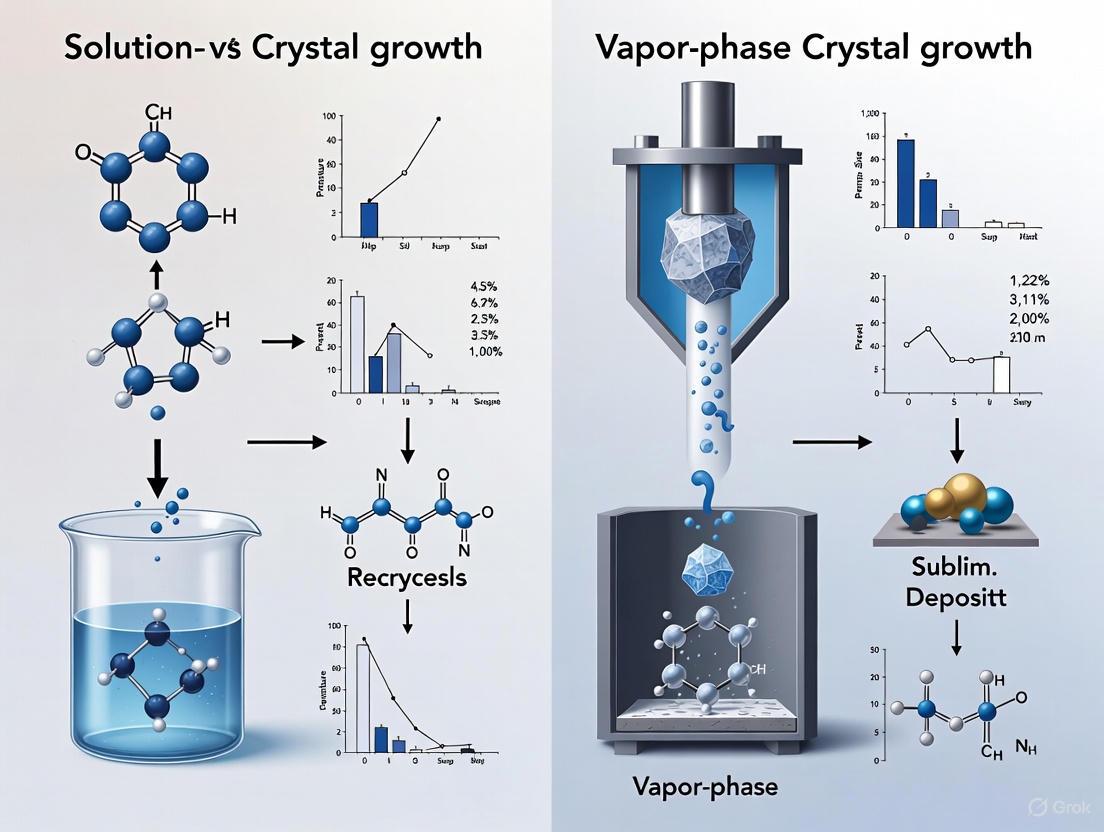

Diagram 1: Pathways to Single Crystal Growth. The diagram illustrates the fundamental steps for growing single crystals via solution-based and vapor-phase methods, highlighting the shared challenge of controlling supersaturation to prevent polycrystalline formation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and reagents essential for controlled crystal growth experiments in a research setting.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Crystal Growth

| Item | Function in Crystal Growth |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Solute | The target material to be crystallized. High purity is essential to minimize the influence of impurities on nucleation kinetics, growth rates, and crystal habit [5] [3]. |

| Ultra-Pure Solvent | The medium for solution growth. Its properties (polarity, viscosity, boiling point) critically influence solubility and supersaturation. Must be pure to avoid spurious nucleation [5]. |

| Single Crystal Seed | A small, perfect crystal used to initiate controlled growth on a defined site, preventing random nucleation and enabling the growth of large single crystals [5]. |

| Dopants / Co-formers | Intentional additives. In pharmaceuticals, co-formers are used to create co-crystals with improved properties [3]. In semiconductors, dopants control electrical properties. |

| Anti-Solvent | A solvent in which the solute has low solubility. Added to a solution to induce rapid supersaturation and nucleation [5]. |

| Crucible / Ampoule | A high-temperature container (e.g., quartz, alumina) to hold the melt or vapor during growth, chosen for its chemical inertness and thermal stability [5]. |

| 6-Chloroindole | 6-Chloroindole | High-Purity Building Block |

| Alexa Fluor 594 Azide | Alexa Fluor 594 Azide, MF:C41H46N6O10S2, MW:847.0 g/mol |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Seeded Crystal Growth from Solution

This protocol outlines a standard method for growing a single crystal from solution using a seed crystal, a critical technique for producing high-quality samples for research.

Principle: To grow a large, high-quality single crystal by initiating growth on a pre-existing, defect-free seed crystal placed in a supersaturated solution, thereby avoiding the stochastic process of primary nucleation.

Materials:

- Solute: High-purity target compound.

- Solvent: Carefully selected based on solubility data and purity.

- Seed Crystals: Small (0.5-1 mm), high-quality single crystals of the target material.

- Growth Vessel: A double-walled jacketed crystallizer (e.g., 1 L) to allow for precise temperature control.

- Programmable Recirculating Bath: For accurate temperature ramping (±0.1 °C).

- Overhead Stirrer: With a paddle impeller for gentle, uniform agitation.

- Filter Assembly: (0.22 µm) for sterile filtration of solutions.

Procedure:

- Saturation Temperature Determination: Add an excess of solute to the solvent in the growth vessel. Stir and heat gradually until all solute dissolves. Record the temperature at which the last crystal dissolves; this is the saturation temperature (T_sat).

- Solution Preparation & Filtration: Create a fresh solution at a temperature 5-10 °C above T_sat. Filter the warm solution through a 0.22 µm filter into the clean, pre-warmed growth vessel to remove dust and micro-nuclei.

- Seed Loading and Stabilization: Lower a selected seed crystal, mounted on a thin thread or a crystall loop, into the solution. Set the bath temperature to 1-2 °C above T_sat and hold for 1-2 hours to allow the system to stabilize and slightly etch the seed, ensuring a fresh growth surface.

- Initiating Growth & Programmed Cooling: Begin a slow, linear cooling ramp (e.g., 0.1-0.5 °C per day). The exact rate depends on the material's metastable zone width and is optimized to maintain growth within the metastable zone, avoiding secondary nucleation.

- Monitoring and Harvesting: Monitor crystal growth daily without mechanical disturbance. Periodically adjust stirring speed to ensure adequate mass transfer without causing abrasion. Once the crystal reaches the desired size, raise it out of the solution and harvest it quickly. Blot dry carefully.

Key Considerations:

- The success of this method hinges on maintaining the solution within the metastable zone, where growth occurs on existing crystals but new nuclei do not spontaneously form [5].

- Agitation must be sufficient to ensure uniform solute concentration and temperature but not so violent as to fracture the growing crystal or induce secondary nucleation.

The distinction between single-crystalline and polycrystalline materials is a fundamental concept in materials science with far-reaching consequences. Single crystals, with their pristine, uninterrupted lattices, offer superior electronic transport properties, higher chemical stability, and uniform behavior, making them indispensable for high-efficiency semiconductors, optics, and fundamental research. Polycrystalline materials, while often stronger and more cost-effective to produce, are limited by the disruptive influence of grain boundaries. The choice between them is not abstract but a practical decision shaped by the targeted application and the available crystal growth techniques, be it from solution or vapor phase. As research progresses, the ability to control crystal structure at the atomic level, including the engineering of grain boundaries themselves, will continue to be a critical factor in advancing technology across electronics, energy storage, and pharmaceutical development.

Crystallization, the process of forming ordered solid structures from disordered phases, is a fundamental phenomenon with critical applications across pharmaceuticals, semiconductors, and energy materials. The thermodynamic drivers of supersaturation, solubility, and phase transition dynamics govern this process, yet their manifestation differs profoundly between the two primary crystallization pathways: solution-based and vapor-phase growth. In solution-based growth, solubility in a solvent and the degree of supersaturation are the dominant parameters, where the system must traverse a path from an undersaturated to a supersaturated state to enable nucleation and crystal growth. In contrast, vapor-phase growth operates on principles of sublimation and vapor pressure, where phase transitions occur directly from the gas phase to the solid state without intermediary liquid solvents. This comparative analysis examines the core thermodynamic drivers, experimental methodologies, and resulting material properties in both frameworks, providing researchers with a structured understanding of their distinct mechanisms and applications.

The paradigm for understanding solution crystallization is undergoing a significant shift. Traditional models presume that crystals grow by diffusion and attachment of individual solute particles to a growth interface. However, this assumption is being challenged by a new perspective grounded in the cooperative-ensemble nature of condensed matter. This transition-zone theory demonstrates that solution crystallization proceeds by the formation of a melt-like pre-growth intermediate, followed by rate-determining cooperative organization into the long-range order of a crystal [8]. This revised thermodynamic understanding resolves longstanding mechanistic riddles across various scientific and industrial domains.

Theoretical Foundations and Thermodynamic Principles

Phase Diagrams and Solution Thermodynamics

Phase diagrams provide the fundamental roadmap for understanding crystallization processes, defining the boundaries between undersaturated, metastable, and labile zones. The solubility boundary separates the undersaturated region, where crystals dissolve, from the metastable zone, where existing crystals can grow but new nuclei do not form spontaneously. The supersolubility boundary further divides the metastable zone from the labile zone, where the high supersaturation drives spontaneous nucleation [9]. For a crystal to nucleate and grow, the system must first reach the labile zone for nucleation, after which growth can continue in either the metastable or labile zone.

The thermodynamic driving force in solution growth is fundamentally derived from the difference between the chemical potential of the dissolved solute and its value at equilibrium. In the context of amorphous pharmaceuticals, for instance, the characteristic "spring-and-parachute" supersaturation profile occurs when dissolution creates a concentration that surpasses crystalline solubility, followed by a plummet back to the crystalline-solubility limit as crystallization occurs [10]. This behavior results from the complex interplay of dissolution kinetics, nucleation, crystal growth, and solid-state transformation of the amorphous solid.

Vapor-Phase Transition Thermodynamics

Vapor-phase crystallization operates on distinct thermodynamic principles, where sublimation—the direct transition from solid to gas phase—replaces dissolution as the initial step. The process is governed by vapor pressure, temperature, and molecular interactions that control phase transitions and crystal growth [11]. In physical vapor transport (PVT) methods, the thermodynamic driving force is created by establishing a temperature gradient that generates a vapor pressure differential, causing the source material to sublimate at the hot end and recrystallize at the cooler end [12].

The formation of perovskite films via vapor-phase deposition illustrates these principles well, involving a complex interplay of vapor transport, surface adsorption, nucleation, and crystallization processes under carefully controlled thermodynamic and kinetic conditions. Vaporized species migrate toward a heated substrate where they adsorb and diffuse across the surface. The mobility of these adatoms, influenced by substrate temperature and surface energy, facilitates the nucleation of critical clusters through classical nucleation mechanisms [13].

Comparative Experimental Methodologies

Solution-Based Crystallization Techniques

Solution-based crystallization employs various methods to achieve supersaturation, each with distinct approaches to controlling the thermodynamic drivers:

Controlled Evaporation Platforms: These systems connect a crystallization droplet with the outside environment through a defined channel, allowing gradual solvent evaporation at a diffusion-limited rate. The volumetric rate of evaporation (J) scales with the humidity or pressure difference (ΔP) and the dimensions of the evaporation channel (cross-sectional area A, length L) according to J ∠(A/L)ΔP. This method guarantees a phase change in each experiment, allows calculation of sample concentration at any time based on the known evaporation rate and initial conditions, and enables pausing the experiment once promising conditions are reached [9].

Low Supersaturation Nucleation (LSN): This technique improves crystallographic perfection by maintaining self-nucleation under conditions of permanent low supersaturation. This approach prevents spontaneous, fast, and uncontrolled parasitic nucleation by allowing the nucleus to develop via local resublimation on the source material. The method involves a complex procedure where source material undergoes local resublimation to form a conical tip with a high-quality monocrystalline seed on top, which then transfers to a pedestal for bulk crystal growth [12].

Decoupling Nucleation and Growth: Once phase behavior is understood, crystallization can be optimized by separating nucleation and growth stages. The system is first driven to high supersaturation (labile zone) for nucleation, then maintained at lower supersaturation (metastable zone) for slower, more ordered crystal growth. This approach avoids excess nucleation that leads to many tiny crystals and improves overall crystal quality [9].

Vapor-Phase Crystallization Techniques

Vapor-phase deposition encompasses several sophisticated methodologies for creating high-quality crystalline materials:

Physical Vapor Transport (PVT): In the "contactless" PVT method for growing high-quality CdTe crystals, a conical tip of source material forms in a thermal gradient, developing a high-quality monocrystalline seed on top. This seed then transfers to a crystal holder for bulk growth. Successful implementation requires precise control of the ampoule position relative to the furnace's maximum temperature, the temperature gradient, and the amount of source material [12].

Close-Space Sublimation (CSS): This vapor-phase technique enables precise modulation of film composition and morphology through controlled sublimation and deposition processes. It offers exceptional control over film formation, leading to high-quality perovskite layers with uniform coverage, tailored composition, and improved interface integration [13].

Co-evaporation and Sequential Deposition: Co-evaporation enables simultaneous deposition of multiple precursors (e.g., CsI and PbI2 for perovskites) with precise stoichiometric control. Sequential evaporation deposits layers in a predetermined order, offering an alternative approach for growing high-quality all-inorganic perovskite layers [13].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Crystallization Techniques

| Technique | Thermodynamic Driver | Key Controlling Parameters | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Controlled Evaporation | Solvent concentration via evaporation | Channel dimensions (A/L), ΔP, initial concentration | Protein crystallization, polymorph screening |

| Low Supersaturation Nucleation | Minimal supersaturation maintenance | Temperature gradient, source material position, ampoule geometry | II-VI and IV-VI semiconductors (CdTe, etc.) |

| Physical Vapor Transport | Vapor pressure differential | Temperature gradient, source amount, system pressure | Semiconductor crystals, perovskite single crystals |

| Close-Space Sublimation | Thermal sublimation kinetics | Source temperature, substrate temperature, gap distance | Perovskite thin films for photovoltaics |

| Co-evaporation | Precursor flux ratios | Evaporation rates, substrate temperature, vacuum level | Complex stoichiometry films, multilayer structures |

Experimental Workflow: Solution vs. Vapor Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the comparative experimental workflows for solution-based and vapor-phase crystallization methodologies, highlighting key decision points and phase transitions:

Diagram 1: Comparative workflows for solution and vapor crystallization pathways

Quantitative Comparison of Growth Parameters

Thermodynamic and Kinetic Parameters

The fundamental differences between solution-based and vapor-phase crystallization approaches manifest clearly in their operational parameters and control mechanisms. Understanding these distinctions enables researchers to select the appropriate methodology for specific material systems and application requirements.

Table 2: Thermodynamic and Kinetic Parameter Comparison

| Parameter | Solution-Based Growth | Vapor-Phase Growth |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Driving Force | Chemical potential difference between solution and crystal | Vapor pressure differential |

| Supersaturation Creation | Cooling, anti-solvent addition, solvent evaporation | Temperature gradient, vacuum application |

| Typical Growth Temperature | Near room temperature to solvent boiling point | Elevated temperatures (100-800°C) |

| Growth Rate | 0.1-10 mm/day | 0.01-100 μm/hour |

| Defect Density | Moderate to high (10^14-10^16 cmâ»Â³) | Low to moderate (10^12-10^15 cmâ»Â³) |

| Scalability | Moderate, limited by solvent handling | High, compatible with semiconductor fab processes |

| Stoichiometry Control | Challenging for complex compositions | Precise through evaporation rate control |

Material Quality and Performance Metrics

The choice of crystallization method significantly impacts the resulting material properties and performance in various applications, particularly in optoelectronics and pharmaceuticals.

For photovoltaic applications, single-crystal perovskites grown via optimized methods exhibit remarkable improvements over their polycrystalline counterparts. Single-crystal perovskites demonstrate a redshifted absorption onset (approximately 850 nm for SC MAPbI3 vs. 800 nm for polycrystalline films), attributed to below-bandgap absorption mechanisms induced by Rashba splitting of the conduction band [14]. This enhanced light absorption, coupled with superior charge transport properties, enables higher performance in devices such as solar cells and radiation detectors.

In pharmaceutical applications, the crystallization method profoundly impacts bioavailability. Amorphous formulations can create supersaturation profiles where concentration sharply increases and surpasses crystalline solubility, providing temporary solubility advantage followed by rapid desupersaturation as crystallization occurs [10]. Understanding and controlling these dynamics through appropriate crystallization method selection is crucial for optimizing drug delivery systems.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Crystallization-Grown Materials

| Material System | Growth Method | Key Performance Metrics | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| CdTe crystals | Low supersaturation nucleation PVT | High crystallographic perfection | Self-nucleation, no defect propagation from seed |

| MAPbI₃ single crystals | Inverse temperature crystallization | Absorption to ~850 nm, low defect density | Superior optoelectronic properties vs. polycrystalline films |

| Inorganic perovskites (CsPbI₂Br) | Vapor-phase co-evaporation | PCE: 15.0%, stability >215 days | Phase-stable γ-CsPbI₃, uniform pinhole-free films |

| Pharmaceutical IND | Solution crystallization & solid-state transformation | Characteristic spring-and-parachute profile | Enhanced bioavailability via supersaturation |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Successful crystallization requires careful selection of materials and reagents tailored to the specific growth methodology. The following toolkit outlines essential components for both solution-based and vapor-phase approaches:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Crystallization Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| High-purity source materials (6N elements) | Starting material for synthesis | Fundamental for both solution and vapor growth of semiconductors (e.g., CdTe) |

| Polymeric excipients (HPMC, PVP, PEG) | Crystal growth modifiers, nucleation inhibitors | Pharmaceutical crystallization to control supersaturation profiles |

| Organic solvents (isopropanol, DMF, DMSO) | Dissolution medium for solutes | Solution-based crystallization for various organic and hybrid materials |

| Precipitants (salts, polymers) | Solubility reduction agents | Protein crystallization, supersaturation generation |

| Single-crystal substrates (various orientations) | Epitaxial growth templates | Vapor-phase heteroepitaxy for electronic materials |

| Evaporation platform materials (PEEK) | Controlled environment chambers | Protein crystallization with defined evaporation rates |

| Sealed ampoules (quartz, glass) | Controlled atmosphere containment | Physical vapor transport growth of sensitive materials |

| 2'-Acetylacteoside (Standard) | 2'-Acetylacteoside (Standard), MF:C31H38O16, MW:666.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Purine phosphoribosyltransferase-IN-2 | Purine phosphoribosyltransferase-IN-2, MF:C11H15N5Na4O10P2, MW:531.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

This comparative analysis demonstrates that the core thermodynamic drivers of supersaturation, solubility, and phase transition dynamics manifest distinctly across solution-based and vapor-phase crystallization methodologies. Solution-based growth offers advantages in structural variety and accessibility, while vapor-phase techniques provide superior control over stoichiometry and material quality. The emerging transition-zone theory for solution crystallization [8] represents a significant paradigm shift from traditional models, emphasizing the cooperative-ensemble nature of crystal formation rather than simple solute attachment.

Future research directions should focus on bridging the gap between these methodologies through hybrid approaches that leverage the advantages of both frameworks. The integration of machine learning and computational modeling [15] shows particular promise for predicting phase behavior and optimizing growth parameters with reduced experimental overhead. Additionally, advancing our fundamental understanding of the cooperative organization processes in crystallization will enable more precise control across multiple length scales, facilitating the development of next-generation materials for energy, electronics, and pharmaceutical applications.

Crystal growth is a fundamental process in materials science, underpinning the creation of high-quality single crystals essential for technologies ranging from semiconductors to pharmaceuticals [16]. This process begins with nucleation, where stable clusters of atoms, ions, or molecules overcome an energy barrier to form initial crystalline seeds, followed by expansion of these nuclei into larger crystals [16]. The driving force behind crystallization is the minimization of the system's free energy, making the crystalline state thermodynamically favorable compared to disordered phases [16]. Understanding nucleation kinetics—encompassing energy barriers, critical nucleus size, and growth rates—is paramount for controlling crystal quality, size, and defect density.

This guide objectively compares these kinetic parameters across two predominant crystallization methodologies: solution-based growth and vapor-phase growth. Solution-based methods, including both static and dynamic liquid phase techniques, are widely used for compounds sensitive to high temperatures, such as proteins or salts [17] [16]. In contrast, vapor-phase growth, exemplified by controlled vapor diffusion, is crucial for growing high-quality crystals of biological macromolecules for drug design [18]. The comparative analysis presented here, framed within a broader thesis on crystal growth research, provides researchers and drug development professionals with quantitative data and experimental protocols to inform method selection and optimization for specific applications.

Theoretical Foundations of Nucleation

Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT)

Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) provides the foundational model for understanding the formation of crystal nuclei from a supersaturated parent phase. CNT describes nucleation as a stochastic process governed by a balance between the volume free energy gained from the phase transformation and the surface energy required to create a new interface [16].

Homogeneous Nucleation: This refers to the spontaneous formation of crystal nuclei within a uniform, supersaturated medium—such as a bulk solution, melt, or vapor—without the influence of external surfaces or impurities [16]. The process is characterized by a significant energy barrier. The total change in Gibbs free energy (ΔG) for forming a spherical nucleus is given by the sum of the unfavorable surface energy term and the favorable volume free energy term: ΔG = 4πr²σ - (4/3)πr³|ΔGv| where

ris the radius of the nucleus,σis the interfacial energy per unit area, andΔG_vis the free energy change per unit volume (negative for a spontaneous process) [16]. This relationship leads to the existence of a critical radius (r*). Clusters smaller than r* are unstable and tend to dissolve, while those larger than r* are stable and likely to grow into crystals [16]. The critical radius is defined as: r* = 2σ / |ΔGv| The corresponding energy barrier for homogeneous nucleation (ΔG) is the maximum free energy that must be overcome to form a stable nucleus and is expressed as: ΔG = (16πσ³) / (3|ΔGv|²) The nucleation rate (J), which is the number of stable nuclei formed per unit volume per unit time, has an exponential dependence on this barrier: J = A exp(-ΔG*/kT) whereAis a pre-exponential factor,kis the Boltzmann constant, andTis the absolute temperature [16]. Consequently, high supersaturation is essential to increase the chemical potential difference (Δμ, which relates to |ΔGv|), thereby reducing both ΔG* and r* and enabling nucleation to occur at a measurable rate [16].Heterogeneous Nucleation: In practical scenarios, nucleation is often catalyzed by foreign surfaces such as container walls, impurities, or engineered substrates [16]. This process, known as heterogeneous nucleation, has a significantly lower energy barrier than homogeneous nucleation. The reduction is quantified by a catalytic factor

f(θ)that depends on the contact angle (θ) between the emerging crystal and the substrate: ΔG_het = ΔG_hom * f(θ) where f(θ) = (2 + cosθ)(1 - cosθ)²/4, and 0 ≤ f(θ) ≤ 1 [16]. A contact angle of θ=0° (perfect wetting) makes f(θ)=0, effectively eliminating the energy barrier [16]. This principle is exploited in seeded growth, where deliberately introduced seeds eliminate the stochastic nucleation stage, allowing for better control over crystal number and size [19].

Kinetic Processes in Crystal Growth

Once a stable nucleus forms, its subsequent growth involves multiple kinetic processes that can be rate-determining. In solution growth, these are primarily the coupling of mass transport of solute molecules to the crystal-solution interface and their integration into the crystal lattice [19]. The dehydration of solute molecules at the interface can also be a significant rate-determining step [19].

The ultimate incorporation of molecules often occurs at specific sites on the crystal surface, such as kinks in growth steps spiraling from dislocations, a mechanism famously described by the Burton-Cabrera-Frank (BCF) model [16]. Growth kinetics can be severely inhibited by trace impurities that adsorb to specific crystal faces, reducing growth rates and altering crystal habit [19].

Comparative Experimental Data: Solution-Based vs. Vapor-Phase Growth

The following tables synthesize quantitative data and key observations from experimental studies on solution-based and vapor-phase crystal growth methods, highlighting differences in nucleation kinetics, crystal quality, and operational parameters.

Table 1: Comparative Nucleation and Growth Kinetics for Solution-Based and Vapor-Phase Methods

| Parameter | Dynamic Liquid Phase Solution Growth [17] | Traditional Static Solution Growth [17] | Computer-Controlled Vapor Diffusion [18] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical System | Copper Sulfate Pentahydrate | Copper Sulfate Pentahydrate | Proteins (e.g., Porcine Insulin) |

| Critical Supersaturation | Precisely controlled via cooling rate (0.05°C/h) and flow. | Induced by cooling (2°C/day); less precise. | Created by controlled solvent evaporation via dry N₂ gas purge. |

| Nucleation Type | Predominantly seeded; avoids spurious nucleation. | Mixed (seeded & unseeded); prone to wall-contact nucleation. | Primarily seeded; controlled evaporation suppresses spontaneous nucleation. |

| Energy Barrier Control | Manipulated via solution flow and temperature. | Limited control; susceptible to heterogeneous nucleation on container. | Directly manipulated by varying the vapor equilibration rate (purge rate). |

| Reported Crystal Quality | High-quality, large-sized (5mm to 20mm); uniform growth on all sides; fewer defects. | Flat, elongated shape; significant defects at container contact points. | Visually larger and more defect-free; improved X-ray diffraction quality. |

| Key Growth Advantage | Seed suspended in solution; no contact with walls or holder. | Simple setup; low cost. | Dynamic control over supersaturation profile; mimics slow equilibration. |

Table 2: Quantitative Experimental Data from Key Studies

| Experimental Metric | Dynamic Solution Growth (Copper Sulfate) [17] | Vapor Diffusion (Proteins) [18] |

|---|---|---|

| Cooling Rate | 0.05°C per hour (from 30°C to 28.8°C) | Not applicable (isothermal) |

| Evaporation/Purge Rate | Not applicable | Multiple profiles tested; slower rates produced higher quality crystals. |

| Crystal Size Achieved | Up to ~20 mm diameter | Visually larger than conventional vapor diffusion |

| Crystallinity (XRD) | Excellent peak sharpness; high crystallinity; enlarged unit cell. | Subject of ongoing X-ray studies; qualitative improvement noted. |

| Characteristic Defects | Minimal defects from lack of physical contact. | Fewer visual defects compared to conventional vapor diffusion. |

| Primary Rate-Determining Process | Mass transport controlled by solution flow and cooling rate. | Vapor-phase diffusion of solvent and interface integration. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Dynamic Liquid Phase Solution Growth

This protocol, adapted from the growth of copper sulfate single crystals, details a method where seed crystals are suspended in solution without physical contact, minimizing defects [17].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Solute: High-purity copper sulfate (CuSOâ‚„) powder. Function: Source of crystallizing material [17].

- Solvent: Ultrapure water. Function: Dissolves solute to create a growth medium [17].

- Seed Crystals: Small (~3 mm) copper sulfate crystals. Function: Provides a template for growth, eliminating the stochastic nucleation stage [17].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Solubility Determination: Prior to growth, determine the precise solubility of the solute (copper sulfate) in the solvent (water) across the target temperature range (e.g., 10°C to 60°C) to prepare accurate saturated solutions [17].

- Seed Crystal Preparation: Prepare small seed crystals (~3 mm in diameter) via spontaneous crystallization from a saturated solution as it cools and solvent evaporates [17].

- Apparatus Setup: Place a pre-prepared seed crystal onto the seed crystal tray of the dynamic growth apparatus. Seal the apparatus and immerse it in a temperature-controlled water bath set to the initial saturation temperature (e.g., 30.1°C). Allow the system to equilibrate for approximately 5 hours to prevent premature crystallization upon solution introduction [17].

- Solution Introduction: Slowly pour a saturated solution at the initial temperature (e.g., 30°C) into the apparatus via the inlet, ensuring a slow and steady flow to fill the apparatus completely without disturbing the seed [17].

- Initiating Growth: Seal the inlets and exhaust vents. Initiate the programmed cooling profile on the intelligent temperature controller. A very slow cooling rate (e.g., 0.05°C per hour) is typically used to maintain controlled, low supersaturation [17].

- Crystal Harvesting: Once the target final temperature is reached or the crystal has grown to the desired size, carefully drain the solution from the apparatus and retrieve the grown single crystal [17].

Computer-Controlled Vapor Diffusion

This protocol, used for protein crystallization such as porcine insulin, allows dynamic control over the equilibration rate, which is fixed in traditional vapor diffusion [18].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Protein Solution: Purified protein in buffer (e.g., Porcine Insulin). Function: The macromolecule to be crystallized [18].

- Precipitant/Reservoir Solution: Salt or polymer solution in buffer. Function: Drives the system toward supersaturation by osmotically drawing water from the protein drop [18].

- Dry Nitrogen Gas: Function: Controlled dry gas flow replaces the traditional reservoir, actively extracting solvent vapor to create supersaturation [18].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Preliminary Screening: Use conventional hanging-drop vapor diffusion in Linbro plates to identify initial crystallization conditions that produce crystals or precipitate. This provides a starting point for optimization with the dynamic system [18].

- System Setup: Place a small drop of the protein-buffer solution on a coverslip or within the designated chamber of the dynamic control system (e.g., CrystalScore) [18].

- Environment Control: Instead of sealing the drop over a reservoir, the system is purged with a controlled flow of dry nitrogen gas. The purge rate is set by the computer to dictate the rate at of solvent evaporation from the drop [18].

- Equilibration and Growth: Allow the system to equilibrate under the controlled gas purge. The slow, precise removal of water increases the concentration of the protein and precipitant in the drop in a predictable manner, gradually driving the solution into supersaturation [18].

- Profile Optimization: Different evaporation profiles (e.g., varying purge rates over time) can be tested. Studies have shown that slower evaporation rates generally result in larger and more defect-free crystals [18].

- Crystal Harvesting: Once crystals have grown to a suitable size, discontinue the gas purge and carefully extract the crystals from the drop for analysis (e.g., X-ray diffraction) [18].

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: A side-by-side comparison of the experimental workflows for computer-controlled vapor diffusion growth (left) and dynamic liquid phase solution growth (right), highlighting their parallel stages and distinct kinetic processes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Typical Example |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Solute | Source material for crystallization; purity is critical to avoid aberrant nucleation and incorporation of impurities. | Copper sulfate powder [17], Purified proteins (e.g., Insulin) [18]. |

| Ultrapure Solvent | Dissolves solute to create the growth medium; purity and chemical compatibility are essential. | Ultrapure water [17], Specific buffer solutions for proteins [18]. |

| Precipitant Agents | Drives the solution into a supersaturated state by reducing solute solubility. | Salts (e.g., in reservoir solution) [18], Polymers. |

| Seed Crystals | Small, high-quality crystals used to initiate growth, bypassing the stochastic nucleation stage and controlling crystal orientation. | ~3-5mm copper sulfate seeds [17]. |

| Engineered Substrates | Surfaces designed to promote heterogeneous nucleation with specific orientation (epitaxial growth) for advanced applications. | Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs) [16]. |

| Controlled Atmosphere Gas | In vapor diffusion, actively controls the rate of solvent evaporation to manipulate supersaturation kinetics. | Dry Nitrogen Gas (Nâ‚‚) [18]. |

| Antiproliferative agent-16 | Antiproliferative agent-16, MF:C17H15N3O, MW:277.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Mal-PEG8-Phe-Lys-PAB-Exatecan | Mal-PEG8-Phe-Lys-PAB-Exatecan, MF:C73H92FN9O20, MW:1434.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

This comparison guide elucidates the distinct nucleation kinetics and experimental realities of solution-based and vapor-phase crystal growth methods. The controlled environment of dynamic liquid phase solution growth excels in producing large, high-quality single crystals of materials like copper sulfate by minimizing contact-induced defects and precisely managing supersaturation through temperature and flow [17]. Conversely, computer-controlled vapor diffusion addresses the primary bottleneck in protein crystallization by dynamically controlling the equilibration rate, leading to visually superior, more diffraction-quality crystals—a crucial advancement for structure-based drug design [18].

The choice between these methods is application-dependent. For robust, small-molecule materials where high yield and size are priorities, dynamic solution growth offers significant advantages. For sensitive biological macromolecules, where the control of subtle supersaturation profiles is paramount to overcome nucleation energy barriers and avoid amorphous precipitation, dynamic vapor diffusion is indispensable. Future advancements will likely involve further integration of real-time monitoring and feedback control to precisely navigate the kinetic pathways of nucleation and growth, pushing the boundaries of crystal quality for both established and emerging materials.

Crystal growth from solution represents a fundamental pillar in materials science and pharmaceutical development, operating at significantly lower temperatures than melt or vapor-phase methods to facilitate the production of high-purity, defect-controlled crystalline materials [20]. This approach enables precise manipulation of crystal properties through controlled supersaturation creation via cooling, antisolvent addition, or solvent evaporation [21]. In pharmaceutical manufacturing, solution-based crystallization is particularly crucial, serving as the primary purification method for approximately 90% of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and 70% of solid chemicals [22]. The strategic selection of solvent systems and optimization of metastable zone parameters directly dictate critical product attributes including polymorphism, crystal habit, size distribution, and purity—factors that ultimately influence drug bioavailability, stability, and manufacturing efficiency [23] [22].

In contrast to vapor-phase methods like molecular beam epitaxy (MBE), which excel in creating atomically-precise thin films under ultra-high vacuum [20], solution-based techniques offer superior control over crystal morphology and habit at substantially lower operational costs and energy requirements. While vapor deposition methods are indispensable for semiconductor applications requiring extreme purity and atomic-layer precision, solution growth remains the dominant approach for pharmaceutical compounds, organic materials, and temperature-sensitive molecules where thermal degradation presents a concern [20]. This comparative analysis examines the fundamental principles governing solvent selection, solute-solvent interactions, and metastable zone optimization that establish solution-based crystallization as a versatile and powerful tool for crystal engineering.

Theoretical Framework: Nucleation Kinetics and Solution Chemistry

Classical Nucleation Theory Fundamentals

Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) provides the primary theoretical framework for understanding crystallization from solution, describing nucleation as a process where solute molecules form stable clusters that overcome a critical energy barrier to become viable crystals [24] [25]. The nucleation rate (J) expresses the number of nuclei formed per unit volume per unit time and is governed by the equation:

J = A exp(-ΔG_critical/kT)

where A represents the pre-exponential factor related to molecular attachment frequency, ΔG_critical denotes the Gibbs free energy barrier for critical nucleus formation, k is Boltzmann's constant, and T is absolute temperature [25] [23]. The critical Gibbs energy barrier depends on the solid-liquid interfacial energy (γ) and the thermodynamic driving force (supersaturation, S), following the relationship:

ΔG_critical = (16πγ³ν²)/(3(kT)³(lnS)²)

where ν represents molecular volume [23]. These fundamental relationships establish that both kinetic (A) and thermodynamic (ΔG_critical) factors collectively govern nucleation behavior, with solvent selection critically influencing both parameters through modulation of solute-solvent interactions and interfacial energies [24] [25].

The Metastable Zone Concept

The metastable zone width (MSZW) defines the supersaturation range where a solution remains clear of detectable nucleation events before spontaneous crystallization occurs [22]. This zone is bounded by the solubility curve (equilibrium boundary) and the supersolubility curve (kinetic boundary), representing a state of thermodynamic instability but kinetic stability. The polythermal method, employing controlled cooling rates, is commonly used to determine MSZW experimentally [24] [22]. Multiple factors influence MSZW measurements, including cooling rate, solution history, agitation intensity, solution volume, and vessel geometry [24] [22]. Understanding and controlling the metastable zone is essential for optimizing crystallization processes, as operating within this zone enables controlled crystal growth while minimizing unwanted spontaneous nucleation that leads to particle size heterogeneity and inconsistent product quality [22].

Solvent Selection Strategies: Thermodynamic and Kinetic Considerations

Solvent Properties and Selection Criteria

Rational solvent selection represents the cornerstone of effective solution-based crystallization process design, with multiple thermodynamic and practical factors guiding optimal choice. The table below summarizes key solvent properties and their impact on crystallization performance:

Table 1: Key Solvent Properties and Their Impact on Crystallization Performance

| Property | Impact on Crystallization | Ideal Characteristic | Experimental Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solute Solubility | Determines process productivity and working concentration | High solubility at elevated temperatures | Gravimetric analysis, in situ FTIR [24] [22] |

| Temperature Coefficient | Dictates yield achievable through cooling crystallization | High positive coefficient | Solubility measurements at multiple temperatures [21] |

| Miscibility with Antisolvent | Critical for antisolvent crystallization processes | Complete miscibility | Phase diagram construction [24] |

| Viscosity | Influences mass transfer and crystal growth kinetics | Low viscosity | Rheological measurements [24] |

| Volatility | Affects evaporation-based crystallization and safety | Appropriate for selected method | Vapor pressure measurements [21] |

| Hazard Profile | Determines environmental, safety, and regulatory acceptability | Low toxicity, non-flammable | Regulatory screening (e.g., IID) [24] |

For pharmaceutical applications, additional constraints include regulatory approval for parenteral administration when developing long-acting injectable formulations, inclusion in the Inactive Ingredient Database (IID), and complete miscibility with water for antisolvent crystallization processes [24]. The solvent must also demonstrate sufficient API solubility to achieve high drug loadings (typically 100-300 mg/mL) required for long-acting injectable suspensions [24].

Thermodynamic Parameters in Solvent Selection

Thermodynamic parameters provide quantitative metrics for rational solvent evaluation and selection. The enthalpy of dissolution (ΔHd) serves as a key indicator, with lower values typically corresponding to easier nucleation kinetics [24]. In studies of complex lipophilic compounds, ΔHd values at similar water mass fractions followed the order: DMAC < NMP < acetone < IPA, establishing a direct correlation between solvent hydrophilicity/polarity and nucleation ease [24]. Solid-liquid interfacial energy (γ) represents another critical thermodynamic parameter derived from CNT, with lower values favoring nucleation. Research on ritonavir demonstrated that interfacial energies varied significantly across solvents, decreasing in the order: ethanol > acetone > acetonitrile > ethyl acetate > toluene, directly correlating with observed nucleation rates [23].

Solvent selection methodologies have evolved to incorporate computer-aided mixture/blend design (CAMbD) approaches that couple property prediction with process models and optimization algorithms to simultaneously identify optimal solvents, antisolvents, compositions, and process conditions for integrated synthesis and crystallization operations [26]. These model-based frameworks enable simultaneous optimization of multiple key performance indicators (KPIs), including mass efficiency, product quality, environmental impact, and safety considerations [26].

Solvent Selection Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the systematic decision process for solvent selection in solution-based crystallization:

Solute-Solvent Interactions: Molecular-Level Insights

Competitive Solvent-Solvent and Solute-Solvent Interactions

The nucleation process is governed by a delicate balance between solute-solvent and solvent-solvent interactions that collectively influence molecular self-assembly pathways. Research on 4-(methylsulfonyl)benzaldehyde (MSBZ) demonstrated that nucleation rates do not simply correlate with solute-solvent interaction strength alone [25]. Instead, the competition between solvent-solvent cohesion and solute-solvent adhesion energies determines nucleation barriers, with stronger solvent-solvent interactions potentially facilitating solute desolvation and nucleation by reducing the energy penalty for solvent cavity formation [25].

Spectroscopic techniques coupled with computational modeling have revealed that specific molecular interactions in solution preconfigure solute molecules into specific conformations that template subsequent crystal forms. In ritonavir, solution-state intramolecular hydrogen bonding between hydroxyl and carbamate groups, coupled with conformational shielding by phenyl groups, creates a kinetic trap that inhibits formation of the thermodynamically stable Form II polymorph [23]. This molecular-level understanding explains the notorious "disappearing polymorph" phenomenon observed with ritonavir and provides strategies for circumventing such crystallization challenges through strategic solvent selection.

Experimental and Computational Approaches

Advanced analytical and computational methods enable detailed investigation of solute-solvent interactions:

Table 2: Experimental and Computational Methods for Studying Solute-Solvent Interactions

| Method | Information Obtained | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| FTIR Spectroscopy | Molecular conformations, hydrogen bonding, solute solvation | Identification of ritonavir conformational states in different solvents [23] |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations | Dynamic intermolecular interactions, solvation shells, conformational preferences | Free energy calculations for ritonavir solvation in different solvents [23] |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Binding energies, molecular orbital interactions, electrostatic potential surfaces | Solute-solvent binding energy calculations for salicylic acid [25] |

| X-ray Crystallography | Molecular conformation, packing arrangement, hydrogen bonding patterns | Comparison of ritonavir Form I and Form II crystal structures [23] |

The integration of these experimental and computational approaches provides a powerful framework for understanding and predicting solvent effects on nucleation kinetics and polymorph selection. For example, MD simulations of ritonavir in explicit solvents revealed how conformational preferences and intramolecular hydrogen bonding compete with intermolecular interaction formation, providing a molecular rationale for observed nucleation barriers and polymorphic outcomes [23].

Metastable Zone Optimization: Experimental Protocols and Theoretical Models

Experimental Determination of MSZW

Metastable zone width determination employs process analytical technology (PAT) tools to detect nucleation onset accurately under controlled conditions. The following experimental protocols represent standardized approaches for MSZW characterization:

Polythermal Method Protocol (Adapted from [24] [22]):

- Prepare saturated solution at elevated temperature with known solute concentration

- Equip crystallizer with PAT tools (FTIR, FBRM, or turbidity probe)

- Implement controlled linear cooling at specified rates (typically 0.1-1.0°C/min)

- Monitor solution continuously for nucleation onset (detected by rapid increase in FBRM counts or turbidity)

- Record temperature at nucleation detection (T_n)

- Calculate MSZW as ΔTmax = Tsaturation - T_n

- Repeat at multiple cooling rates to establish cooling rate dependence

Isothermal Method Protocol (Adapted from [23]):

- Prepare supersaturated solution at constant temperature

- Monitor solution continuously for fixed time period or until nucleation occurs

- Record induction time (t_ind) for multiple supersaturation levels

- Construct cumulative probability distributions of induction times

- Calculate nucleation rates from probability distributions: J = [-ln(1-P(t))]/(V·t)

- Repeat across temperature and supersaturation ranges

These protocols enable quantitative characterization of MSZW dependence on critical process parameters, providing essential data for crystallization process design and optimization.

Theoretical Models for MSZW Analysis

Several theoretical models facilitate the interpretation of MSZW data to extract nucleation kinetics:

Nyvlt Model: Relates MSZW to cooling rate through the equation: ln(ΔTmax) = (1-m)ln(Rc) + K where R_c is cooling rate, m is nucleation order, and K is a temperature-dependent constant [22].

Sangwal Model: Describes MSZW dependence on cooling rate considering the fundamental nucleation processes: ΔTmax = (a/Rc)^b where a and b are parameters related to interfacial energy and critical nucleus size [24].

Novel CNT-Based Model: Recent advancements incorporate cooling rate dependence directly into nucleation rate expressions, enabling calculation of nucleation parameters across different cooling conditions [22].

The following table compares nucleation parameters derived from MSZW analysis for different compound-solvent systems:

Table 3: Experimentally Determined Nucleation Parameters from MSZW Studies

| Compound | Solvent | Nucleation Rate Constant (molecules/m³·s) | Interfacial Energy (mJ/m²) | Critical Nucleus Size (nm) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paracetamol | Isopropanol | 10²¹ - 10²² | 2.6 - 8.8 | ~10â»Â³ | [22] |

| Intermediate A | DMAC | Not reported | Lower relative to other solvents | Smaller critical nuclei | [24] |

| Intermediate A | IPA | Not reported | Higher relative to other solvents | Larger critical nuclei | [24] |

| Ritonavir | Toluene | Higher than ethanol | Lower relative to other solvents | Smaller critical nuclei | [23] |

| Ritonavir | Ethanol | Lower than toluene | Higher relative to other solvents | Larger critical nuclei | [23] |

PAT Tools for MSZW Characterization

Modern MSZW determination leverages advanced Process Analytical Technology (PAT) to enable real-time monitoring of crystallization processes:

In Situ Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy: Measures solute concentration through characteristic absorption bands, enabling precise determination of solubility curves and supersaturation levels [22].

Focused Beam Reflectance Measurement (FBRM): Detects nucleation onset through rapid increase in particle counts, providing accurate determination of metastable zone boundaries [22].

Turbidity Probes: Monitor light transmission through solutions, identifying nucleation events through decreased transmission associated with crystal formation [23].

These PAT tools facilitate high-quality solubility and MSZW data acquisition within 24 hours—a significant improvement over conventional methods requiring weeks or months [22]. The implementation of PAT-supported protocols aligns with Quality by Design (QbD) principles in pharmaceutical manufacturing, enabling enhanced process understanding and control.

Comparative Analysis: Solution vs. Vapor-Phase Crystal Growth

The strategic selection between solution and vapor-phase crystal growth methods depends on material properties, performance requirements, and economic considerations. The following diagram illustrates the relationship between different crystal growth techniques and their applications:

Table 4: Comparative Analysis of Crystal Growth Methods

| Parameter | Solution Growth | Vapor-Phase Growth | Melt Growth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operating Temperature | Low (typically <100°C) | Variable (room temperature to high) | Very high (often >1000°C) |

| Growth Rate | Moderate to slow | Slow to very slow | High |

| Applicability | Temperature-sensitive compounds, pharmaceuticals | Thin films, layered structures | Bulk semiconductors, metals |

| Polymorph Control | Excellent through solvent selection | Limited | Limited to none |

| Crystal Size | Millimeter to centimeter scale | Nanometer to micrometer scale | Centimeter to meter scale |

| Capital Cost | Low to moderate | High to very high | Moderate to high |

| Process Complexity | Moderate | High | Moderate |

Solution-based methods offer distinct advantages for pharmaceutical applications, including superior control over polymorph selection through strategic solvent choice, compatibility with temperature-sensitive organic molecules, and significantly lower operational costs compared to vapor-phase techniques [20] [23]. Conversely, vapor-phase methods like Molecular Beam Epitaxy (MBE) provide unparalleled atomic-layer precision and purity for electronic and optoelectronic applications, albeit at substantially higher capital and operational costs [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful solution-based crystallization requires carefully selected materials and reagents. The following table details essential components for experimental investigations:

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Solution-Based Crystallization Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Solvents | Dissolve solute, create supersaturation | API crystallization | Purity, water content, regulatory status [24] |

| Antisolvents | Reduce solubility, induce supersaturation | LASC processes | Miscibility with solvent, purity [24] |

| Model Compounds | Method development, fundamental studies | Paracetamol, ritonavir, MSBZ | Purity, well-characterized behavior [23] [22] |

| PAT Tools | Process monitoring, endpoint detection | FTIR, FBRM, turbidity probes | Calibration, compatibility with solvents [22] |

| Crystallization Vessels | Contain solution, enable control | Jacketed reactors, multi-well plates | Material compatibility, geometry [24] |

| Temperature Control | Precise thermal management | Thermostats, cryostats | Stability, ramp rates [24] [22] |

| Agitation Systems | Promote mixing, uniformity | Overhead stirrers, magnetic stirrers | Shear control, scaling considerations [24] |

| HDAC-IN-27 dihydrochloride | HDAC-IN-27 dihydrochloride, MF:C20H23ClN4O2, MW:386.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| KRAS G12C inhibitor 16 | KRAS G12C inhibitor 16, MF:C24H21ClFN3O3, MW:453.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

This toolkit enables comprehensive investigation of solvent selection, solute-solvent interactions, and metastable zone optimization, providing the fundamental infrastructure for advancing solution-based crystal growth research and development.

Solution-based crystal growth remains an indispensable technology for pharmaceutical development and materials science, with strategic solvent selection, molecular-level understanding of solute-solvent interactions, and metastable zone optimization representing critical control points for process success. The integrated application of experimental characterization techniques—including PAT tools for MSZW determination—with computational modeling approaches provides a powerful framework for rational crystallization process design. As pharmaceutical compounds increase in molecular complexity and lipophilicity, these fundamental principles of solution-based crystallization will continue to enable the production of advanced materials with tailored properties and enhanced performance characteristics.

The comparative analysis with vapor-phase methods highlights the complementary nature of crystal growth technologies, with solution-based approaches offering unparalleled advantages for temperature-sensitive materials, polymorph control, and cost-effective manufacturing at scale. Future advancements will likely focus on increasing integration of computational prediction tools with automated experimental platforms, further enhancing our ability to navigate complex crystallization landscapes and deliver optimized processes with reduced development timelines. Through continued refinement of these solution-based fundamentals, researchers and engineers will maintain a robust toolkit for addressing the evolving challenges of crystal engineering in pharmaceutical and advanced materials applications.

The choice between solution-based and vapor-phase crystal growth methods is a pivotal one in research and industrial fields, including pharmaceutical development. Each method dictates the purity, crystal structure, size, and morphology of the resulting solid phase, which in turn can critically influence the properties and performance of the final product, such as drug bioavailability and stability. Vapor-phase processing, which encompasses techniques where a crystal grows from a gaseous precursor, is fundamentally governed by the principles of sublimation thermodynamics, equilibrium vapor pressure, and molecular adsorption at interfaces. This guide provides a comparative examination of these core vapor-phase fundamentals, juxtaposing them with solution-phase alternatives and presenting the essential experimental data and protocols that underpin this critical field of study.

Thermodynamic Foundations of Phase Transitions

Vapor Pressure and Equilibrium

Vapor pressure is defined as the pressure exerted by a vapor in thermodynamic equilibrium with its condensed phases (solid or liquid) at a given temperature in a closed system [27]. It is a quantitative measure of a substance's thermodynamic tendency to evaporate (from a liquid) or sublimate (from a solid) [27] [28]. This equilibrium is dynamic; molecules continuously escape from the condensed phase into the vapor phase, while vapor molecules condense or deposit back onto the surface at an equal rate [29]. The pressure at which these two processes occur at the same rate is the equilibrium vapor pressure [28].

The vapor pressure of a substance is intrinsically linked to the strength of the intermolecular forces holding its condensed phase together. Substances with relatively weak intermolecular forces (e.g., diethyl ether) will have high vapor pressures, as molecules can escape more readily. Conversely, substances with strong intermolecular forces, such as hydrogen bonding in water or ethyl alcohol, exhibit relatively low vapor pressures [27] [29].

Sublimation Thermodynamics

Sublimation is the direct phase transition from a solid to a gas without passing through an intermediate liquid phase [30]. Like evaporation, it is an endothermic process, requiring an input of thermal energy to overcome the solid's lattice energy [30]. Every solid possesses a vapor pressure, though for many it is immeasurably low at room temperature [27] [30]. Sublimation becomes practically significant for volatile solids like iodine, naphthalene, and dry ice (solid COâ‚‚) [27].

The thermodynamics of sublimation can be described by a form of the Clausius-Clapeyron relation, which connects the vapor pressure of a solid to the temperature and the enthalpy of sublimation [27]. For a solid well below its melting point, the sublimation pressure can be estimated if the vapor pressure of the supercooled liquid and the heat of fusion are known, using the following relation [27]:

ln P_s^sub = ln P_l^sub - (Δ_fus H / R) * (1/T_sub - 1/T_fus)

Where:

P_s^subis the vapor pressure of the solid.P_l^subis the vapor pressure of the supercooled liquid.Δ_fus His the molar enthalpy of fusion.Ris the universal gas constant.T_subis the temperature of sublimation.T_fusis the melting point temperature.

This equation illustrates that the sublimation pressure is lower than the extrapolated liquid vapor pressure, a difference that increases further from the melting point [27].

Comparative Data: Vapor Pressures of Common Substances

Understanding the relative volatilities of substances is crucial for selecting appropriate crystal growth methods. The following tables provide quantitative vapor pressure data for common liquids and volatile solids, enabling a direct comparison of their tendencies to transition into the vapor phase.

Table 1: Vapor Pressure of Common Liquids at Room Temperature (Approx. 20-25°C)

| Substance | Vapor Pressure (kPa) | Vapor Pressure (atm) | Intermolecular Forces |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diethyl Ether [29] | ~70.9 | 0.7 [29] | Dipole-Dipole, London Dispersion |

| Bromine [29] | ~30.4 | 0.3 [29] | London Dispersion |

| Acetone [31] | 30.0 | ~0.30 | Dipole-Dipole, London Dispersion |

| Methyl Alcohol [31] | 16.9 | ~0.17 | Hydrogen Bonding |

| Ethyl Alcohol [29] [31] | 12.4 [31] | 0.08 [29] | Hydrogen Bonding |

| Water [29] [31] | 2.4 [31] | 0.03 [29] | Hydrogen Bonding |

| Ethylene Glycol [31] | 0.007 | ~0.00007 | Hydrogen Bonding |

Table 2: Examples of Solids and Their Sublimation Behavior

| Substance | Sublimation Behavior | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Dry Ice (Solid CO₂) [27] | High vapor pressure (5.73 MPa at 20°C) [27] | Requires robust, pressurized containers; demonstrates significant vapor-phase presence at room temperature. |

| Ice (Solid Hâ‚‚O) [30] | Readily sublimes; vital to the natural water cycle [30] | Contributes to freeze-drying processes; vapor pressure is temperature-dependent. |

| Naphthalene [27] | Volatile solid with measurable sublimation rate [27] | A common example in sublimation experiments and moth repellents. |

Experimental Protocols for Vapor-Phase Studies

Measuring Equilibrium Vapor Pressure

A standard method for measuring the vapor pressure of liquids involves using a closed system connected to a pressure measurement device like a manometer [27] [29].

Protocol:

- Purification: The test substance is first purified to remove any volatile impurities [27].

- Containment: A sample of the liquid is introduced into a closed, evacuated flask [27] [29].

- Thermal Equilibrium: The container is submerged in a constant-temperature liquid bath to ensure the entire substance and its vapor are at the same prescribed temperature [27].

- Pressure Measurement: The system is allowed to reach dynamic equilibrium, where the rate of evaporation equals the rate of condensation. The pressure exerted by the vapor is then measured directly using the manometer [27] [28] [29].

- Data Collection: This procedure is repeated across a range of temperatures to build a vapor pressure vs. temperature curve [27].

For solids with very low vapor pressures, more sensitive methods like the Knudsen effusion cell technique are employed [27].

Studying Vapor-Phase Adsorption Kinetics

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are a powerful tool for obtaining a molecular-level understanding of vapor-phase adsorption, such as the adsorption of aroma molecules onto water interfaces [32].

Protocol:

- System Setup: A simulation box is constructed containing a water-vapor interface.

- Introduction of Adsorbate: Molecules of interest (e.g., linalool) are introduced into the vapor phase [32].

- Trajectory Simulation: The classical equations of motion are solved for all atoms over time, tracking their positions and energies as they diffuse and potentially adsorb at the interface [32].

- Data Analysis:

- Surface Coverage: The number of adsorbate molecules per unit area at the interface is calculated [32].

- Surface Tension: The reduction in surface tension is computed as a function of surface coverage. Studies show that for molecules like linalool, the surface tension decrease depends only on surface coverage, whether adsorption occurs from the vapor or liquid phase [32].

- Energetics: The free energy profile of adsorption and the strength of specific interactions (e.g., between a hydroxyl group and water molecules) are analyzed to determine if the process is enthalpy-driven [32].

- Molecular Classification: Adsorbed molecules can be classified based on their trajectories and energy distributions into categories such as "bound molecules," "generally adsorbed molecules," "non-adsorbed molecules," and "free molecules" [33].

Visualizing Vapor-Phase Processes and Thermodynamics

The following diagrams illustrate the core concepts and workflows involved in vapor-phase studies.

Diagram 1: Dynamic Equilibrium in a Closed System

Diagram 2: Vapor Pressure Measurement Protocol

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Vapor-Phase Studies

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Isoteniscope [27] | A specialized glass apparatus used for the accurate measurement of vapor pressure of liquids by submerging the sample container in a liquid bath to ensure thermal equilibrium. |

| Knudsen Effusion Cell [27] | An instrument used to measure the very low vapor pressures of solids by analyzing the rate at which molecules effuse through a small orifice into a vacuum. |

| High-Pressure Sealed Vessels [27] | Robust containers required for studying substances with high vapor pressures (e.g., dry ice) to prevent rupture. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Software [32] [33] | Computational tools used to model and visualize the adsorption, diffusion, and energy profiles of molecules at interfaces at the atomic level. |

| Constant-Temperature Bath [27] | Provides precise and stable temperature control, which is critical for obtaining accurate vapor pressure data. |

| Manometer [29] | A device for measuring the pressure of the vapor in a closed system, essential for direct vapor pressure experiments. |

| Volatile Solids (Naphthalene, Iodine) [27] | Model compounds for studying sublimation kinetics and thermodynamics in laboratory settings. |

| Aroma Molecules (e.g., Linalool) [32] | Used as model volatile surfactants in studies of vapor-phase adsorption kinetics and surface tension reduction at water-air interfaces. |

| Aldose reductase-IN-3 | Aldose reductase-IN-3, MF:C18H12ClN3O2S2, MW:401.9 g/mol |

| Ethyl-L-nio hydrochloride | Ethyl-L-nio hydrochloride, MF:C9H19N3O2, MW:201.27 g/mol |

Vapor-phase crystal growth is fundamentally governed by the equilibrium vapor pressure of the source materials and the thermodynamics of sublimation and adsorption. The data and protocols presented here highlight the precise control offered by vapor-phase methods, which can lead to the production of high-purity crystals with specific morphologies. In contrast, solution-based growth is more susceptible to solvent incorporation and is governed by different thermodynamic and kinetic parameters, such as solubility and diffusion in a liquid medium. The choice between these two paradigms depends heavily on the thermal stability and volatility of the target compound. For volatile substances, vapor-phase methods offer a clean, solvent-free alternative, whereas solution-based growth remains the only viable option for many non-volatile compounds, including large biomolecules and many pharmaceutical salts. A deep understanding of vapor pressure, sublimation thermodynamics, and interfacial adsorption mechanisms is therefore indispensable for selecting and optimizing the appropriate crystal growth strategy in research and drug development.

Crystal Growth Methodologies: Techniques, Protocols, and Material-Specific Applications

Solution-based crystal growth techniques are fundamental to producing high-quality single crystals essential for advanced optoelectronics and pharmaceutical applications. Among these methods, Antisolvent Vapor-Assisted Crystallization (AVC) and Inverse Temperature Crystallization (ITC) have emerged as two prominent strategies for growing perovskite single crystals, which are critical for solar cells, radiation detectors, and light-emitting diodes [34]. These techniques offer distinct pathways to control supersaturation—the driving force behind nucleation and crystal growth—through different physical mechanisms.

This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of AVC and ITC methodologies, supported by experimental data and protocols. By examining their fundamental principles, optimized procedures, and performance outcomes, this article serves as a reference for researchers and development professionals selecting appropriate crystallization techniques for specific material systems and application requirements.

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Antisolvent Vapor-Assisted Crystallization (AVC)