Predicting Thermodynamic Stability of Inorganic Materials: Machine Learning, Generative AI, and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern approaches for predicting and designing thermodynamically stable inorganic materials, crucial for advancing biomedical and technological applications.

Predicting Thermodynamic Stability of Inorganic Materials: Machine Learning, Generative AI, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern approaches for predicting and designing thermodynamically stable inorganic materials, crucial for advancing biomedical and technological applications. It explores foundational concepts of thermodynamic stability and its importance in materials discovery, examines cutting-edge machine learning frameworks like ensemble models and generative AI that achieve unprecedented accuracy in stability prediction, addresses methodological challenges and optimization strategies to reduce computational bias, and validates these approaches through case studies and experimental verification. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes recent breakthroughs that are accelerating the design of stable materials for drug delivery systems, medical devices, and pharmaceutical formulations.

The Fundamentals of Thermodynamic Stability in Inorganic Materials

In the field of inorganic materials research, thermodynamic stability serves as a fundamental predictor of a material's synthesizability and lifetime under operational conditions. This is particularly critical in pharmaceutical development, where the stability of crystalline APIs (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients) and excipients directly impacts drug shelf life, bioavailability, and safety profiles. Two quantitative metrics have emerged as essential tools for stability assessment: the decomposition energy (Edecomp) and the energy above the convex hull (Ehull). These metrics enable researchers to evaluate whether a compound will remain intact or decompose into competing phases, guiding the efficient discovery of novel materials with desired properties. While traditional experimental approaches to stability determination are time-consuming and resource-intensive, computational methods now provide accelerated pathways for stability screening across vast compositional spaces. The integration of machine learning with first-principles calculations has further revolutionized this field, enabling researchers to navigate complex multi-component systems with unprecedented efficiency. This technical guide examines the core concepts, computational methodologies, and emerging frameworks for thermodynamic stability assessment, providing researchers with practical protocols for implementation.

Core Theoretical Concepts

Decomposition Energy (Edecomp)

Decomposition energy (Edecomp or ΔHd) represents the total energy difference between a target compound and its most stable competing phases in a specific chemical space. Mathematically, it is defined as the energy required for a compound to decompose into other thermodynamically more stable compounds [1] [2]. A negative Edecomp indicates that the compound is stable against decomposition into those specific products, while a positive value suggests thermodynamic instability. However, it is crucial to note that a negative Edecomp for a specific decomposition pathway does not conclusively prove synthesizability, as other competing phases not considered in the calculation might represent lower-energy decomposition products [2].

The general formulation for calculating decomposition energy is:

Edecomp(compound) = E(compound) - ΣciE(decomposition product i)

where ci represents the stoichiometric coefficients that balance the chemical reaction and conserve atoms [2]. For accurate comparison, all energies must be normalized per atom (eV/atom) when working within composition space [2].

Energy Above the Convex Hull (Ehull)

The energy above the convex hull (Ehull) provides a more comprehensive stability metric by measuring the vertical energy distance from a compound to the convex hull in energy-composition space [2] [3]. The convex hull represents the minimum energy "envelope" formed by the most stable phases across all compositions in a chemical system [2] [4]. A compound with Ehull = 0 meV/atom lies directly on the hull and is considered thermodynamically stable, while positive values indicate metastability or instability, with higher values corresponding to greater instability [2] [3].

The convex hull construction is geometrical in nature and can exist in multiple dimensions corresponding to the number of elements in the system [2]. For a compound above the hull, Ehull represents the energy penalty per atom for existing as that specific phase rather than as a mixture of the stable hull phases below it. In practical terms, Ehull quantifies how much a compound is energetically disfavored relative to its decomposition products [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Thermodynamic Stability Metrics

| Metric | Definition | Interpretation | Calculation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decomposition Energy (Edecomp) | Energy difference between compound and specific decomposition products | Negative value favors stability against specific decomposition path; does not guarantee global stability | Chemical reaction energy with normalized energies (eV/atom) |

| Energy Above Hull (Ehull) | Vertical distance to convex hull in energy-composition space | Ehull = 0: thermodynamically stable; Ehull > 0: metastable/unstable | Geometric construction via convex hull algorithm in normalized composition space |

| Formation Energy (Ef) | Energy to form compound from elemental constituents | Measures stability relative to elements; less informative than Ehull for synthesizability | E(compound) - Σ(elemental references) |

Computational Determination of Stability Metrics

First-Principles Calculations

Density Functional Theory (DFT) serves as the foundational method for obtaining the accurate total energies required for stability assessments. The standard workflow involves:

- Structural Relaxation: Geometry optimization of crystal structures to reach their ground-state configuration using DFT codes such as VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, or ABINIT [2].

- Energy Calculation: Computation of the total energy for each relaxed structure.

- Energy Normalization: Conversion of total energies to eV/atom for comparable metrics across different compositions [2].

- Reference Data Collection: Compilation of energies for all known competing phases within the chemical system of interest.

To ensure proper Ehull calculations using frameworks like PyMatGen, researchers must use consistent DFT parameters (functionals, pseudopotentials, convergence criteria) across all structures and include sufficient reference structures to adequately represent the compositional space [2].

Convex Hull Construction

The convex hull algorithm calculates the minimum energy envelope in energy-composition space across any number of dimensions [2]. For multi-element systems, the decomposition may involve multiple phases in thermodynamic equilibrium. For example, BaTaNO₂ decomposes into a mixture of 2/3 Ba₄Ta₂O₉ + 7/45 Ba(TaN₂)₂ + 8/45 Ta₃N₅, where the stoichiometric coefficients ensure conservation of elemental concentrations when using normalized compositions [2].

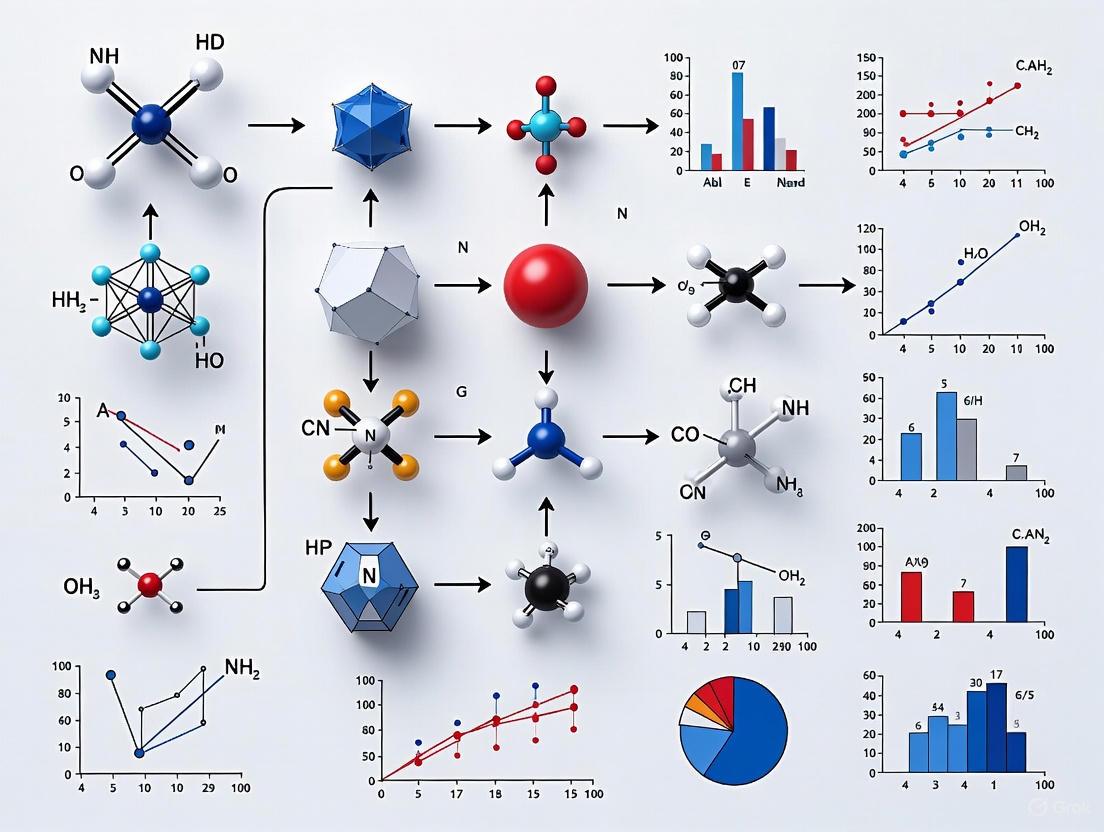

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between core concepts and the workflow for stability assessment:

Stability Assessment Workflow

Machine Learning Approaches

Machine learning methods have emerged as powerful alternatives to reduce computational costs while maintaining accuracy in stability prediction:

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): For structure-based predictions, GNNs can accurately predict thermodynamic stability with errors lower than "chemical accuracy" of 1 kcal molâ»Â¹ (43 meV per atom) [5]. The Upper Bound Energy Minimization (UBEM) approach uses scale-invariant GNNs to predict volume-relaxed energies from unrelaxed structures, providing an efficient screening method with 90% precision in identifying stable Zintl phases [5].

Ensemble Composition-Based Models: Models like ECSG (Electron Configuration with Stacked Generalization) integrate multiple approaches including Magpie (atomic statistics), Roost (graphical representation of compositions), and ECCNN (electron configuration-based CNN) to achieve AUC of 0.988 in stability prediction while requiring only one-seventh of the data used by traditional models [1].

Convex Hull-aware Active Learning (CAL): This Bayesian algorithm uses Gaussian Processes to model energy surfaces and prioritizes compositions that minimize uncertainty in the convex hull, significantly reducing the number of energy evaluations needed for accurate stability predictions [4].

Table 2: Machine Learning Methods for Stability Prediction

| Method | Input Data | Key Features | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Crystal structures | Scale-invariant architecture; predicts volume-relaxed energies; enables UBEM approach | 90% precision for Zintl phases; MAE of 27 meV/atom [5] |

| ECSG (Ensemble) | Chemical composition | Combines electron configuration, atomic statistics, and interatomic interactions; reduces inductive bias | AUC = 0.988; high sample efficiency [1] |

| LightGBM Regression | Elemental features | Handles skewed and multi-peak feature distributions; works with SHAP interpretability | Low prediction error for perovskite Ehull [3] |

| CAL (Active Learning) | Energy evaluations | Gaussian Processes; focuses on hull uncertainty minimization; iterative refinement | Reduced evaluations in ternary spaces [4] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: UBEM Approach for High-Throughput Screening

The Upper Bound Energy Minimization (UBEM) protocol enables efficient discovery of thermodynamically stable phases [5]:

- Dataset Curation: Extract known structural prototypes from databases like ICSD (e.g., 824 pnictide-based Zintl phases).

- Chemical Decoration: Systematically decorate parent structures with isovalent elements from relevant groups (e.g., Groups 1, 2, 12, 13, 14, 15), generating >90,000 hypothetical structures.

- GNN Training: Train a scale-invariant GNN model on DFT volume-relaxed structures. The model should learn to predict volume-relaxed energies from unrelaxed crystal structures.

- Energy Prediction: Apply the trained GNN to predict volume-relaxed energies for all decorated structures.

- Stability Analysis: For each composition, identify the candidate with the lowest predicted energy as the representative upper bound minimum structure.

- DFT Validation: Compute decomposition energies (Edecomp) for predicted stable phases relative to competing phases using first-principles calculations.

This approach ensures that if the volume-relaxed structure is thermodynamically stable, the fully relaxed structure will assuredly be stable, providing a robust screening methodology [5].

Protocol 2: Ensemble Machine Learning for Composition-Based Stability Prediction

For composition-based stability prediction without structural information [1]:

Feature Engineering:

- Encode compositions using electron configuration information (118 × 168 × 8 matrix for ECCNN).

- Calculate statistical features (mean, variance, range, etc.) of elemental properties (Magpie).

- Represent chemical formula as a complete graph of elements (Roost).

Model Integration:

- Develop three base models: ECCNN (electron configuration), Magpie (elemental statistics), and Roost (graph representation).

- Apply stacked generalization to combine base model outputs into a super learner (ECSG).

- Train meta-learner on base model predictions to generate final stability assessment.

Validation:

- Evaluate model performance using Area Under the Curve (AUC) metrics.

- Test sample efficiency by comparing with traditional models.

- Apply to targeted material classes (2D wide bandgap semiconductors, double perovskite oxides) and validate predictions with DFT.

Protocol 3: Thermodynamic Stability Assessment for Organic-Inorganic Hybrid Perovskites

Specialized protocol for perovskite stability analysis [3]:

Data Preprocessing:

- Collect dataset of organic-inorganic hybrid perovskites with known Ehull values.

- Apply MinMaxScaler for feature normalization: X_normalize = (x - min)/(max - min).

- Identify and remove outliers using box plot analysis (crystal length, standard deviation of proportion for B and X atoms, etc.).

Model Training:

- Implement four regression algorithms: RFR, SVR, XGBoost, and LightGBM.

- Optimize hyperparameters for each algorithm using cross-validation.

- Select best-performing model based on prediction error (LightGBM demonstrated superior performance).

Interpretation:

- Apply SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) to identify critical features influencing Ehull.

- Determine that third ionization energy of B element and electron affinity of X-site ions are most significant for perovskite stability.

- Use model to screen new perovskite compositions for high stability.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| VASP | Software | First-principles DFT calculations | Structural relaxation and energy computation for stability analysis [2] |

| PyMatGen | Python Library | Materials analysis | Convex hull construction and phase diagram analysis [2] |

| Materials Project | Database | Repository of computed materials properties | Source of reference energies for competing phases [1] [2] |

| JARVIS | Database | Repository of DFT-computed properties | Training and validation data for machine learning models [1] |

| GNN (Graph Neural Network) | Algorithm | Pattern recognition in crystal structures | Predicting formation energies and thermodynamic stability [5] |

| SHAP Analysis | Interpretability Method | Feature importance quantification | Identifying elemental properties critical to stability [5] [3] |

| CAL Framework | Active Learning Algorithm | Efficient convex hull mapping | Minimizing energy evaluations for stability assessment [4] |

The rigorous definition and assessment of thermodynamic stability through decomposition energy and convex hull analysis provide fundamental tools for advancing materials research across scientific disciplines. For pharmaceutical development professionals, these metrics offer predictive capability for crystal form stability, directly impacting drug development pipelines and formulation strategies. The integration of machine learning frameworks with traditional computational approaches has significantly accelerated stability screening, enabling researchers to navigate complex multi-component systems with enhanced efficiency. Emerging methodologies like convex hull-aware active learning and ensemble models represent the cutting edge of this field, promising continued advancement in our ability to design and discover stable functional materials. As these computational tools become increasingly sophisticated and accessible, they will play an ever-expanding role in guiding experimental synthesis efforts and stabilizing novel materials for technological applications.

In the field of inorganic materials research, thermodynamic stability is not merely an academic concept but a fundamental property that dictates a material's very existence and technological utility. It determines whether a newly predicted compound can be synthesized, whether a functional material will maintain its performance under operating conditions, and how it will interact with its environment over time. Thermodynamic stability, typically represented by the decomposition energy (ΔHd), is defined as the total energy difference between a given compound and its competing phases in a specific chemical space, ascertained by constructing a convex hull using formation energies [1]. Materials lying on this convex hull are considered stable, while those above it are metastable or unstable.

The implications of stability extend across the entire materials lifecycle—from initial synthesis to final application. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these implications is crucial for designing materials with predictable behaviors and extended functional shelf-lives. This technical guide examines the critical relationships between thermodynamic stability and key practical considerations in inorganic materials research, providing both theoretical frameworks and experimental methodologies for stability assessment.

Fundamental Principles: Stability in Inorganic Materials

Quantitative Stability Metrics

The thermodynamic stability of inorganic compounds is quantitatively assessed through several computational and experimental metrics. Table 1 summarizes the key quantitative metrics used in stability assessment, their methodological basis, and significance for materials behavior.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Metrics for Assessing Thermodynamic Stability

| Metric | Methodological Basis | Significance & Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Above Hull (Ehull) | Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations comparing compound energy to convex hull of stable phases [1] | Ehull < 0.1 eV/atom: Generally considered synthesizable [6]; Lower values indicate higher stability |

| Decomposition Energy (ΔHd) | Energy difference between compound and most stable competing phases [1] | Determines thermodynamic driving force for decomposition; Fundamental to shelf-life prediction |

| Goldschmidt Tolerance Factor (t) | Empirical geometric parameter: t = (rA + rX)/√2(rB + rX) for perovskites [7] | 0.8 < t < 1.0: Predicts perovskite structure stability; Guides compositional engineering |

| Activation Energy (Ea) for Ion Migration | Experimental measurements (e.g., impedance spectroscopy) or computational simulations [7] | Higher Ea indicates suppressed ion migration, enhancing operational stability under bias |

Structural and Electronic Determinants of Stability

The stability of inorganic materials is governed by fundamental atomic-level interactions and electronic structure considerations:

- Crystal Field Effects: The arrangement of anions around metal centers creates crystal fields that stabilize particular electronic configurations, influencing both structural integrity and redox behavior [7].

- Orbital Hybridization: In functional materials like perovskites, optimal orbital overlap between metal cations and anions stabilizes the inorganic framework. For example, in halide perovskites, the unique optoelectronic properties arise from Pb-6s and I-5p orbital mixing, which must be maintained for phase stability [7].

- Electron Configuration: The distribution of electrons within atoms, encompassing energy levels and electron count at each level, serves as an intrinsic property that correlates strongly with stability without introducing the biases associated with manually crafted features [1].

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected factors governing thermodynamic stability in inorganic materials and their downstream implications:

Diagram 1: Factors and implications of thermodynamic stability in inorganic materials.

Stability Implications for Materials Synthesis

Predictive Synthesis of Novel Compounds

The synthesis of predicted materials represents a critical bottleneck in computationally-driven materials discovery. While convex-hull stability indicates whether a material should be synthesizable, it does not provide guidance on actual synthesis parameters such as precursors, temperatures, or reaction times [8]. Advanced machine learning approaches are now addressing this challenge:

- Generative Models: Diffusion-based models like MatterGen directly generate stable crystal structures across the periodic table, more than doubling the percentage of stable, unique, and new (SUN) materials compared to previous methods [6]. These models can be fine-tuned to generate materials with specific chemistry, symmetry, and properties.

- Ensemble Methods: The ECSG (Electron Configuration with Stacked Generalization) framework integrates models based on different domain knowledge—electron configuration, atomic properties, and interatomic interactions—to mitigate individual model biases and achieve exceptional predictive accuracy (AUC = 0.988) for compound stability [1].

- Text-Mining Synthesis Recipes: Natural language processing of literature synthesis procedures has extracted thousands of synthesis recipes, though anthropogenic biases in historical research patterns limit the diversity of these datasets [8].

Experimental Synthesis Challenges

Even with computational guidance, experimental synthesis faces stability-related challenges:

- Metastable Phases: The rapid formation of competing metastable phases can create kinetic barriers to synthesizing predicted stable compounds. In La-Si-P ternary systems, molecular dynamics simulations revealed that swift formation of Si-substituted LaP phases prevents synthesis of predicted ternary compounds, explaining experimental difficulties [9].

- Multi-Component Stabilization: In complex material systems like multicomponent perovskites, incorporating multiple elements at crystal sites creates synergistic stabilization by adjusting tolerance factors and increasing ion migration activation energy [7]. This approach stabilizes phases that would be unstable in single-component forms.

- Narrow Processing Windows: Some compounds have extremely narrow temperature windows for successful synthesis from solid-liquid interfaces, requiring precise experimental control [9].

Stability-Performance Relationships in Functional Applications

Energy Storage Materials

In energy storage systems, stability directly governs performance retention and cycle life:

- Electrode Materials: Spinel-type MgCo2O4 exhibits high theoretical capacity for energy storage applications, but its practical implementation requires nanostructuring and composite formation to address stability limitations during cycling [10]. Pristine MgCo2O4 electrodes suffer from limited specific capacity, low energy density, and poor cycling stability, necessitating composite strategies.

- Phase Change Materials (PCMs): Organic-inorganic composite PCMs like LNH-AC/bentonite demonstrate how stability enhancements translate to performance retention. After 100 thermal cycles, optimized composites maintain stable phase transition temperatures and latent heat values, enabling reliable energy storage for solar thermal applications [11].

Electronic and Photonic Materials

Stability-performance relationships are particularly crucial in optoelectronic applications:

- Perovskite Photovoltaics: Inorganic perovskite solar cells based on CsPbX3 compositions offer improved stability over hybrid organic-inorganic counterparts, but still require sophisticated stabilization strategies to overcome phase instability and lead leakage issues [7] [12]. Multicomponent approaches distributing different elements across A, B, and X sites synergistically compensate for composition-induced instability.

- Two-Dimensional Semiconductors: Machine learning predictions guided by stability metrics enable discovery of new two-dimensional wide bandgap semiconductors with both appropriate electronic properties and sufficient stability for device integration [1].

Catalytic Systems

Stability under operating conditions determines catalytic lifetime and economic viability:

- Spinel Cobaltites: MgCo2O4 nanomaterials maintain catalytic functionality under reaction conditions due to their spinel structure and thermal stability [10]. Their multicomponent nature provides stability advantages over simple oxides in demanding catalytic environments.

- Nanostructure Preservation: The stability of specific crystal facets and nanoscale morphologies under reaction conditions (temperature, pressure, chemical environment) directly correlates with catalytic activity maintenance [10].

Shelf-life and Environmental Degradation Mechanisms

Fundamental Degradation Pathways

Material degradation under environmental stressors follows predictable pathways influenced by thermodynamic stability:

- Ion Migration: In ionic materials like perovskites, migration of ions under electric fields or concentration gradients drives degradation. Increasing ion migration activation energy through compositional engineering directly extends functional shelf-life [7].

- Phase Segregation: Multi-component systems with limited solid solubility tend to segregate into stable phases over time, degrading functional properties. This is particularly problematic in mixed-halide perovskites where light-induced halide segregation reduces photovoltaic performance [7].

- Surface Reactions: Exposure to ambient conditions (moisture, oxygen, carbon dioxide) drives surface reactions that propagate into bulk material. Less stable materials with higher surface energies are particularly susceptible [12].

Stability Enhancement Strategies

Multiple approaches can mitigate degradation and extend functional shelf-life:

- Compositional Engineering: In multicomponent perovskites, partial substitution of A-site cations and X-site anions adjusts tolerance factors within the stable range (0.8-1.0) while increasing ion migration activation energies [7].

- Composite Formation: Combining organic and inorganic components in phase change materials circumvents limitations of individual material classes—avoiding supercooling and phase separation in inorganic PCMs while improving thermal conductivity over organic PCMs [11].

- Defect Passivation: Strategic addition of passivating agents at grain boundaries and interfaces reduces degradation initiation sites [7] [12].

- Protective Coatings: Applying nanometer-scale protective layers prevents environmental penetration while maintaining functional performance [12].

Experimental Protocols for Stability Assessment

Computational Stability Screening

Table 2: Methodologies for Computational Stability Assessment

| Method | Protocol | Output Metrics | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT Convex Hull Analysis | 1. Calculate formation energies for target compound and competing phases2. Construct convex hull phase diagram3. Compute energy above hull (Ehull) [1] | Ehull (eV/atom), Decomposition energy, Stable decomposition products | Requires comprehensive sampling of competing phases; Dependent on exchange-correlation functional accuracy |

| Machine Learning Prediction | 1. Train ensemble models (e.g., ECSG) on diverse feature sets2. Validate against known stable compounds3. Predict stability of new compositions [1] | Stability probability (AUC score), Classification (stable/metastable/unstable) | Training data quality determines predictive accuracy; Different models capture different stability aspects |

| Molecular Dynamics with ML Potentials | 1. Develop neural network potentials from DFT2. Simulate phase formation kinetics3. Identify competing metastable phases [9] | Phase formation barriers, Kinetic competition diagrams, Synthesisability assessment | Provides kinetic insights beyond thermodynamic stability; Computationally intensive |

Experimental Stability Validation

Protocol: Accelerated Aging Testing for Shelf-life Prediction

Sample Preparation: Synthesize material using optimized protocols; characterize initial structure and composition (XRD, SEM-EDS) [11] [9].

Stress Application:

- Thermal Stress: Cycle between temperature extremes relevant to application (e.g., -20°C to 85°C for electronics) [11]

- Environmental Stress: Expose to controlled humidity (e.g., 85% RH), oxygen, or specific chemical environments [7]

- Electrical Stress: Apply bias voltage or current cycling for electronic materials [7] [12]

- Radiation Stress: Illuminate with simulated solar spectrum for photonic materials [7]

Monitoring and Analysis:

- Perform periodic structural characterization (XRD, Raman) to detect phase changes [11]

- Measure functional properties (conductivity, catalytic activity, photovoltaic parameters) to track performance degradation [12]

- Analyze surface composition (XPS, AES) to identify surface reactions [7]

- Characterize morphological changes (SEM, TEM) to observe microstructural evolution [11]

Degradation Kinetics Modeling:

- Fit property decay to kinetic models (zero-order, first-order, diffusion-controlled)

- Extract degradation rate constants and activation energies

- Extrapolate to normal storage/operation conditions for shelf-life prediction

The following workflow outlines the integrated computational and experimental approach for stability assessment:

Diagram 2: Integrated workflow for stability assessment of inorganic materials.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Stability Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Stability Research |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Databases | Materials Project (MP), Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD), Alexandria [1] [6] | Provide formation energies and reference structures for stability comparisons and convex hull constructions |

| Generative Models | MatterGen, CDVAE, DiffCSP [6] | Generate novel stable crystal structures for inverse design of materials with target properties |

| Stability Prediction Models | ECSG framework, Magpie, Roost, ECCNN [1] | Predict thermodynamic stability of compositions using ensemble machine learning approaches |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents | Reline (ChCl:urea), Ethaline (ChCl:ethylene glycol), Glyceline (ChCl:glycerol) [13] | Serve as environmentally friendly reaction media with templating effects for nanoparticle synthesis |

| Characterization Techniques | In-situ XRD, SEM/TEM, Thermal analysis (DSC/TGA), Impedance spectroscopy [11] [9] | Monitor structural, morphological and property changes during stability testing |

| Stabilization Additives | Bentonite, α-Al2O3, Expanded graphite, Boron nitride [11] | Enhance thermal cycle stability in composite materials through nanostructuring and interfacial effects |

Thermodynamic stability serves as the fundamental bridge between computational materials prediction and real-world technological implementation. As generative models like MatterGen dramatically increase the throughput of stable material discovery [6], and ensemble methods like ECSG improve prediction accuracy [1], the research frontier is shifting toward understanding kinetic stability under operational conditions. For research scientists and drug development professionals, integrating stability considerations from the earliest design stages through shelf-life prediction enables creation of materials with predictable behaviors and extended functional lifetimes. The continued development of multiscale stability models—connecting electronic structure to macroscopic degradation—will further accelerate the design of next-generation inorganic materials optimized for both performance and durability across diverse technological applications.

The pursuit of new inorganic materials with tailored properties for applications in energy storage, catalysis, and electronics relies fundamentally on accurately determining thermodynamic stability. This stability dictates whether a proposed compound can be synthesized and persist under operational conditions. Traditional determination methods form a dual pillar approach: experimental measurement provides empirical validation under specific conditions, while Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations offer a predictive, atomistic understanding of stability at the quantum mechanical level. The synergy between these methods accelerates materials discovery by bridging theoretical prediction with experimental reality, providing researchers with a robust toolkit for navigating the vast compositional space of inorganic materials. This guide details the core principles, methodologies, and interplay of these foundational techniques within modern inorganic materials research.

Fundamental Concepts of Thermodynamic Stability

Key Energetic Metrics

The thermodynamic stability of inorganic compounds is primarily assessed through several key energetic metrics derived from the concept of the convex hull, which is constructed from the formation energies of all known compounds in a given chemical space.

- Formation Energy (ΔH~f~): The enthalpy change when a compound is formed from its constituent elements in their standard states. A negative value typically indicates stability with respect to elemental decomposition.

- Decomposition Energy (ΔH~d~): Defined as the total energy difference between a given compound and the most stable combination of competing phases in its chemical space. It represents the energy penalty for a compound to decompose into other stable compounds on the convex hull [1].

- Energy Above Hull (E~above-hull~): A critical metric quantifying how far a compound's energy lies above the convex hull. Compounds with E~above-hull~ = 0 meV/atom are thermodynamically stable, while those with positive values are metastable. The magnitude of this energy indicates the degree of metastability [14] [15].

The Convex Hull and Synthesizability

The convex hull is a fundamental construct in materials thermodynamics. When the formation energies of all compounds in a chemical system are plotted, the convex hull is the set of lines connecting the stable phases (those with the lowest energy for a given composition). Any compound lying on this hull is considered thermodynamically stable.

- Metastable Compounds: Compounds that lie above the convex hull but can still be synthesized due to kinetic barriers. Their synthesizability is often guided by heuristic energy limits.

- Amorphous Limit: A proposed thermodynamic upper bound for synthesizability, which posits that a crystalline polymorph with a higher energy than its amorphous counterpart at 0 K is highly unlikely to be synthesized at any finite temperature, as the amorphous phase will always be thermodynamically preferred (see Figure 1) [15]. This limit is chemistry-dependent, ranging from ~0.05 eV/atom for network-forming oxides like SiO~2~ to ~0.5 eV/atom for other metal oxides.

Figure 1: Energy Landscape and Synthesizability. The convex hull connects the ground state and synthesizable polymorphs (B, C). Polymorph A, lying above the amorphous limit, is thermodynamically forbidden from synthesis via crystallization.

Experimental Determination Methods

Experimental methods provide direct measurement of thermodynamic stability by probing a material's energy landscape through its response to temperature or by determining its crystal structure to calculate formation energies.

Calorimetric Techniques

Calorimetry directly measures the heat effects associated with phase transformations and chemical reactions, providing quantitative data on enthalpies of formation.

- Protocol: High-Temperature Oxide Melt Solution Calorimetry

- Objective: Determine the standard enthalpy of formation (ΔH~f~) of an inorganic solid.

- Principle: The enthalpy of drop solution (ΔH~ds~) of a compound and its constituent elements (or precursor oxides) into a solvent (e.g., molten oxide) is measured. The ΔH~f~ is derived from the difference between these ΔH~ds~ values using an appropriate thermochemical cycle.

- Key Reagents: A molten oxide solvent (e.g., 2PbO·B~2~O~3~ at 700-800 °C) contained in a platinum crucible.

- Procedure:

- Calibrate the calorimeter using the melting point of a standard (e.g., gold).

- Press powdered sample into a pellet.

- Drop the pellet into the calorimeter's solvent at a controlled temperature.

- Measure the heat effect (endothermic or exothermic) associated with the dissolution process.

- Repeat for the compound and all relevant precursor phases.

- Data Analysis: Construct a thermochemical cycle to link the measured ΔH~ds~ values to the standard state formation reaction, solving for the unknown ΔH~f~.

Experimental Crystal Structure Determination

Accurate crystal structures are vital as inputs for DFT calculations and for validating computationally predicted structures. Small changes in structure can dramatically alter predicted electrical, thermal, and mechanical properties [14].

- Protocol: Single-Crystal X-ray Diffraction (SCXRD)

- Objective: Determine the precise atomic arrangement, lattice parameters, and space group of a crystalline material.

- Principle: A single crystal is irradiated with a monochromatic X-ray beam. The diffracted beams produce a pattern from which the electron density within the crystal can be reconstructed.

- Key Reagents: High-quality single crystal (typically 0.1-0.3 mm in dimension), mounted on a glass fiber.

- Procedure:

- Select and mount a suitable single crystal.

- Center the crystal in the X-ray beam and collect preliminary rotation images.

- Perform a full data collection, rotating the crystal and recording diffraction intensities.

- Index the reflections to determine unit cell parameters.

- Solve the phase problem and refine the structural model against the measured data.

- Data Analysis: The final refined model provides atomic coordinates, site occupancies, and anisotropic displacement parameters. The lattice parameters and space group are used directly for comparison with DFT-optimized structures [14]. The internal consistency of experimental data can be evaluated by comparing multiple entries for the same compound, which reveals that average uncertainties in cell volume are between 0.1% and 1% [14].

Density Functional Theory (DFT) Calculations

DFT is the workhorse for ab initio prediction of material properties, enabling high-throughput screening of material stability before synthesis.

Core Principles and Workflow

DFT solves the quantum mechanical many-body problem by using the electron density as the fundamental variable, significantly reducing computational cost.

Figure 2: DFT Stability Assessment Workflow. The standard computational procedure for determining the thermodynamic stability of a compound.

- Protocol: Calculating Energy Above Hull

- Objective: Determine the thermodynamic stability of a target compound relative to all other phases in its chemical system.

- Computational Principle: The Kohn-Sham equations are solved self-consistently to find the ground-state electron density and total energy of a crystal structure.

- Procedure:

- Initialization: Obtain an initial crystal structure (from experimental databases like ICSD or via prototyping).

- Geometry Optimization: Relax the atomic positions and unit cell parameters until the forces on atoms and stresses on the cell are minimized. This finds the ground-state structure.

- Energy Calculation: Perform a single-point energy calculation on the optimized structure to obtain the final total energy.

- Reference Calculation: Repeat steps 1-3 for all known compounds in the same chemical system (A-B-C...).

- Hull Construction: Calculate the formation energy per atom for each compound. Plot these energies versus composition and construct the lower convex envelope.

- Stability Metric: For the target compound, E~above-hull~ is calculated as its formation energy minus the hull energy at its composition.

The accuracy of DFT predictions is subject to several approximations, which must be understood for reliable results.

- Exchange-Correlation Functional: The choice of functional introduces systematic errors. The Local Density Approximation (LDA) overbinds, leading to contracted lattice parameters, while the Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) generally provides more accurate structures but can poorly describe London dispersion forces, critical for layered materials [14]. Meta-GGA functionals like RSCAN often offer superior accuracy for mechanical properties [16].

- Hubbard U Correction (DFT+U): For transition metal oxides with localized d- or f-electrons, a Hubbard U correction is often applied to mitigate self-interaction error. However, the U value is a sensitive empirical parameter. High U values (e.g., ~4 eV for Mo) can cause anomalous reversals in stability predictions and incorrect ground states, as demonstrated in Mo-containing oxides [17]. Transferability of U across different compounds and oxidation states is limited.

- Temperature and Pressure: Standard DFT calculations are performed at 0 K and 0 Pa, whereas experiments occur at finite temperatures and ambient pressure. This discrepancy can affect the comparison of properties like lattice parameters and phase stability [14].

Table 1: Comparison of Common DFT Exchange-Correlation Functionals for Property Prediction

| Functional Type | Example | Typical Performance for Lattice Parameters | Typical Performance for Elastic Properties | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDA | LDA (PW) | ~1% underestimation | Overestimation of bulk modulus | Severe overbinding |

| GGA | PBE | ~1% overestimation [14] | Slight underestimation of bulk modulus [16] | Poor description of dispersion forces [14] |

| GGA (Solid-Optimized) | PBESOL | Improved over PBE | High accuracy (e.g., AAD ~3.4 GPa for B) [16] | Less common in high-throughput databases |

| Meta-GGA | RSCAN | Good overall accuracy | Best overall accuracy (e.g., AAD ~3.1 GPa for B) [16] | Higher computational cost |

| Hybrid | HSE06 | High accuracy | High accuracy | Prohibitive computational cost for large systems [17] |

Comparative Analysis and Best Practices

Quantitative Comparison of Accuracy

Understanding the typical deviations between computational and experimental data is crucial for assessing prediction reliability.

Table 2: Typical Uncertainties in Lattice Parameters and Elastic Properties

| Property | Method | Typical Uncertainty / Deviation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lattice Parameters | Experiment (PCD) | 0.1 - 1% in cell volume [14] | Based on multi-entry analysis for the same compound |

| Lattice Parameters | DFT (PBE-GGA) | ~1% overestimation vs. experiment [14] | Varies with functional and compound type |

| Bulk Modulus (B) | DFT (PBE) | AAD* ~7.8 GPa vs. low-T experiment [16] | Highly functional-dependent |

| Bulk Modulus (B) | DFT (RSCAN) | AAD* ~3.1 GPa vs. low-T experiment [16] | Meta-GGA offers significant improvement |

| Elastic Coefficients (c~ij~) | DFT (PBE) | RRMS* ~16% [16] | Larger relative errors for individual tensor components |

*AAD: Average Absolute Deviation; RRMS: Relative Root Mean Square Deviation.

Integrated Workflow for Stability Assessment

A robust approach combines the strengths of both computation and experiment, as illustrated in the protocol below.

- Protocol: Combined DFT and Experimental Validation for Metastable Materials

- High-Throughput DFT Screening: Use databases (Materials Project, OQMD, AFLOW) or custom calculations to screen candidate compositions. Filter candidates based on a reasonable E~above-hull~ threshold (e.g., < 50-100 meV/atom for oxides) [15] and check against the amorphous limit [15].

- Accuracy Refinement: For promising candidates, perform higher-fidelity DFT calculations. Test multiple functionals (e.g., PBESOL, RSCAN) and, for transition metals, carefully validate the U parameter against known experimental data (e.g., structure, redox energy) to avoid stability reversal anomalies [17].

- Synthesis Attempt: Target the most computationally promising candidates for laboratory synthesis using techniques appropriate for metastable phases (e.g., soft chemistry, solvothermal methods, fluxes).

- Structural Characterization: Use SCXRD or powder XRD to determine the crystal structure of the synthesized material.

- Experimental Stability Validation: Perform calorimetry to measure the formation enthalpy. Compare the experimental ΔH~f~ and the synthesized structure with DFT predictions to validate and refine the computational models.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for Stability Determination of Inorganic Materials

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Stability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) | Experimental Database | Repository of experimentally determined inorganic crystal structures. | Provides initial structures for DFT calculations; ground truth for validating predicted structures [14] [15]. |

| Pauling File (PCD) | Experimental Database | Comprehensive database of inorganic crystal structures and phase diagrams. | Used to evaluate uncertainties in experimental lattice parameters and for comparative analysis [14]. |

| Materials Project (MP) | Computational Database | High-throughput DFT calculated properties for over 150,000 materials. | Source for computed formation energies, E above hull, and elastic properties for stability screening [14] [16] [17]. |

| Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD) | Computational Database | DFT-computed thermodynamic and structural properties of inorganic compounds. | Alternative source for convex hull data and formation energies [1] [17]. |

| CASTEP / VASP | Software Package | DFT simulation codes using plane-wave basis sets and pseudopotentials. | Workhorse tools for performing geometry optimizations and energy calculations [16] [17]. |

| Molten Oxide Solvent (2PbO·B~2~O~3~) | Chemical Reagent | Solvent for high-temperature oxide melt solution calorimetry. | Enables direct experimental measurement of formation enthalpies for solid compounds. |

| Sodium phthalimide | Sodium phthalimide, CAS:33081-78-6, MF:C8H4NNaO2, MW:169.11 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Terramycin-X | Terramycin-X|C23H25NO9|Research Chemical | Terramycin-X (C23H25NO9) is a tetracycline-class compound for research use only. It is not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

The field is rapidly evolving with the integration of new computational techniques. Machine-learned potentials are emerging as tools to approach DFT accuracy at a fraction of the cost, though their performance for properties like elasticity is still being established [16]. More impactful is the use of ensemble machine learning models that use only compositional information to predict stability. Models like ECSG, which incorporate electron configuration data, can achieve high accuracy (AUC > 0.98) in predicting stability, dramatically improving data efficiency and guiding DFT studies towards the most promising regions of chemical space [1].

In conclusion, the traditional determination methods of experiment and DFT calculations are complementary and interdependent. Experimental techniques provide the essential, empirical foundation upon which computational methods are built and validated. DFT, in turn, provides a powerful predictive framework that guides efficient experimental exploration. An understanding of the capabilities, limitations, and uncertainties inherent in both approaches—from the choice of DFT functional to the statistical uncertainty in experimental lattice parameters—is fundamental to the accurate determination of thermodynamic stability and the successful discovery of new inorganic materials.

The discovery and development of new inorganic materials have long been hindered by the vastness of compositional space and the immense cost of experimental trial-and-error. Within this challenge, accurately predicting thermodynamic stability—whether a compound will persist under given conditions—serves as a critical gateway, separating viable candidates from those that will decompose. The traditional approach to establishing stability, relying on experimental phase diagram construction and characterization, is notoriously time-consuming and resource-intensive. This landscape has been fundamentally transformed by the advent of high-throughput density functional theory (DFT) calculations and the large-scale databases they power [18]. Two pillars of this data revolution are the Materials Project (MP) and the Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD), which provide systematic, computed thermodynamic data for hundreds of thousands of known and hypothetical materials. By making DFT-calculated formation energies and decomposition enthalpies readily accessible, these platforms have redefined how researchers assess thermodynamic stability, accelerating the design of novel materials for applications ranging from batteries and semiconductors to catalysts.

Theoretical Foundations of Thermodynamic Stability

The Convex Hull Model

At the core of computational stability assessment is the convex hull model. For a given chemical system, the formation energies of all known compounds are calculated, and the convex hull is constructed in energy-composition space [19]. The stability of a compound is determined by its position relative to this hull.

Formation Energy Calculation: The formation energy (( \Delta E_f )) of a compound is the energy difference between the compound and its constituent elements in their standard states. It is calculated as:

( \Delta Ef = E{\text{compound}} - \sumi ni \mu_i )

where ( E{\text{compound}} ) is the total energy of the phase, ( ni ) is the number of atoms of element ( i ), and ( \mu_i ) is the reference energy per atom of element ( i ) [19].

Stability Metric: The key quantitative metric for thermodynamic stability is the hull distance (( \Delta Ed )), or decomposition energy. It represents the energy difference between the compound and the convex hull at its composition. A compound with ( \Delta Ed = 0 ) is thermodynamically stable, meaning no combination of other phases in the system has a lower energy. A positive ( \Delta E_d ) indicates the energy cost required for the compound to decompose into the most stable phases on the hull [19].

DFT Methodology and Uncertainty

Both MP and OQMD employ DFT as the foundational computational method. Despite its power, DFT predictions carry inherent uncertainties. A comparative study highlighted that the variance in formation energies between different high-throughput DFT databases can be as high as 0.105 eV/atom, with a median relative absolute difference of 6% [20]. These discrepancies arise from choices in computational parameters, including pseudopotentials, the DFT+U formalism for correcting electron self-interaction in transition metal compounds, and the selection of elemental reference states [20] [18]. A significant validation effort by OQMD, comparing DFT predictions with 1,670 experimental formation energies, found a mean absolute error of 0.096 eV/atom [18]. Notably, the researchers observed that the mean absolute error between different experimental measurements themselves was 0.082 eV/atom, suggesting that a substantial fraction of the apparent error may be attributed to experimental uncertainties [18].

The Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD)

Database Structure and Contents

The OQMD is a high-throughput database developed in Chris Wolverton's group at Northwestern University. As of its 2015 foundational publication, it contained nearly 300,000 DFT calculations [21] [18]. The database is built upon the qmpy python framework, which uses a django web interface and a MySQL backend [22] [18].

The structures in the OQMD originate from two primary sources:

- Experimental Structures: Curated entries from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD).

- Hypothetical Structures: Decorations of commonly occurring crystal structure prototypes, enabling the exploration of uncharted compositional space [18].

Table 1: Key Features of the OQMD

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Primary Focus | DFT-calculated thermodynamic and structural properties [21] |

| Database Size | ~1.3 million materials (current) [21] |

| Core Infrastructure | qmpy (Python/Django) [18] |

| Data Accessibility | Fully open and available for download without restrictions [18] |

| Key Analysis Tool | PhaseSpace class for thermodynamic analysis in qmpy [22] |

Stability Analysis Workflow

The OQMD's analysis toolkit, accessible through the PhaseSpace class in qmpy, provides a suite of methods for thermodynamic stability assessment [22]. The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for constructing a phase diagram and evaluating compound stability.

The PhaseSpace class enables advanced analyses, including the identification of equilibrium phases and the computation of phase transformations as a function of chemical potential [22]. A pivotal outcome of this high-throughput approach has been the prediction of approximately 3,200 new compounds that had not been experimentally characterized at the time of the study, demonstrating the power of computational screening to guide experimental discovery [18].

The Materials Project (MP)

Ecosystem and Data Methodology

The Materials Project provides a comprehensive web-based platform for materials data analytics. A cornerstone of its methodology is the application of energy corrections to improve the accuracy of formation energies across diverse chemical spaces [23]. These corrections address well-known systematic errors in standard DFT (e.g., GGA) when dealing with elements like Oâ‚‚ and transition metal oxides. MP has evolved its correction schemes; the current approach can mix calculations from different levels of theory, including GGA, GGA+U, and the more modern r2SCAN meta-GGA functional [24] [19].

Constructing Phase Diagrams with MP Data

MP provides extensive documentation and application programming interfaces (APIs) for users to construct and analyze phase diagrams. The process, implemented in the pymatgen code, closely follows the convex hull method [19].

Table 2: Key Features of the Materials Project

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Web-based platform for materials data analytics |

| Database Size | Over 150,000 materials (as of 2025 database versions) [24] |

| Core Infrastructure | pymatgen (Python materials genomics library) [19] |

| Data Accessibility | Web interface and REST API (some data restrictions apply, e.g., GNoME) [24] |

| Key Analysis Tool | PhaseDiagram class in pymatgen [19] |

The following code snippet, adapted from MP's documentation, demonstrates how to construct a phase diagram for the Li-Fe-O chemical system using the MP API and pymatgen [19]:

MP's database is continuously updated. Recent releases (v2024.12.18) have introduced a new hierarchy for thermodynamic data, prioritizing the more accurate GGA_GGA+U_R2SCAN mixed data, followed by r2SCAN and GGA_GGA+U [24]. This reflects a continuous effort to improve the accuracy and reliability of stability predictions.

Comparative Analysis and Emerging Approaches

Cross-Database Comparison

While both MP and OQMD share the common goal of providing DFT-derived thermodynamic data, differences in their computational settings, potential energy corrections, and structure selection can lead to variations in predicted formation energies and stability, as noted in the comparative study [20]. The choice between them may depend on the specific research needs, such as the desire for completely open data (OQMD) or the use of a specific functional or correction scheme (MP's r2SCAN data).

The Machine Learning Frontier

The data provided by MP and OQMD have also become the foundation for training machine learning (ML) models, offering a path to even faster stability screening. A recent advancement is the Electron Configuration models with Stacked Generalization (ECSG) framework [1]. This ensemble model integrates three distinct composition-based models—Magpie, Roost, and a novel Electron Configuration Convolutional Neural Network (ECCNN)—to mitigate the inductive bias inherent in any single model [1]. The ECSG framework achieved an exceptional Area Under the Curve (AUC) score of 0.988 in predicting compound stability within the JARVIS database and demonstrated remarkable sample efficiency, requiring only one-seventh of the data used by existing models to achieve the same performance [1]. This illustrates a powerful trend where ML models, trained on high-throughput DFT databases, are creating ultra-efficient proxies for stability prediction.

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section details key resources and computational "reagents" essential for researchers conducting thermodynamic stability analysis using these platforms.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Computational Stability Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Function & Purpose |

|---|---|

| VASP (Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package) | The primary DFT calculation engine used by both OQMD and MP to compute total energies from first principles [18]. |

| pymatgen (Python Materials Genomics) | A robust Python library central to the MP ecosystem. It provides the PhaseDiagram class for hull construction and analysis [19]. |

| qmpy | The Python/Django-based database and analysis framework underpinning the OQMD. It contains the PhaseSpace and FormationEnergy classes for thermodynamic analysis [22] [18]. |

| MPRester API Client | The official Python client for accessing the Materials Project REST API, allowing for programmatic retrieval of data for use in scripts and analyses [19]. |

| MaterialsProject2020Compatibility | A class in pymatgen that applies MP's energy corrections to computed entries, ensuring accurate formation energies for phase diagram construction [24]. |

| Methanethiol-13C | Methanethiol-13C, CAS:90500-11-1, MF:CH4S, MW:49.10 g/mol |

| Ramelteon impurity D | Ramelteon impurity D, CAS:880152-61-4, MF:C17H23NO2, MW:273.37 g/mol |

The Materials Project and the Open Quantum Materials Database have fundamentally reshaped the practice of inorganic materials research by making vast repositories of computed thermodynamic data freely accessible. They have standardized the convex hull as the definitive computational tool for assessing thermodynamic stability at zero temperature. While built on the foundation of high-throughput DFT, the ecosystem continues to evolve with more accurate functionals like r2SCAN and sophisticated machine learning models that promise to further accelerate the discovery cycle. As these databases grow and their methodologies refine, they solidify their role as indispensable tools for identifying novel, stable materials, thereby driving innovation across energy, electronics, and beyond. This data-driven paradigm marks a permanent shift away from reliance on serendipity toward the rational, computational design of matter.

In the realm of biomedical engineering, the thermodynamic stability of materials is not merely an academic concern but a fundamental determinant of safety, efficacy, and functionality. Thermodynamic stability, defined by a material's decomposition energy (ΔHd) and its position on the convex hull of a phase diagram, dictates a substance's inherent tendency to undergo chemical or structural change under physiological conditions [1]. For inorganic materials—including metals, ceramics, and their hybrid composites—this stability is paramount, as their failure within the body can lead to device malfunction, inflammatory responses, or the release of cytotoxic ions [25]. The challenge is multifaceted: these materials must maintain integrity over prolonged periods in a complex, aqueous, and often corrosive environment at 37°C, while simultaneously performing a specific biomedical function, whether as a drug carrier, an imaging contrast agent, or a structural implant [26] [27].

Framed within the broader context of inorganic materials research, this whitepaper examines how thermodynamic stability governs performance across key biomedical applications. It explores the fundamental instability mechanisms, details advanced characterization and computational prediction methods, and provides a structured analysis of material-specific challenges from the nanoscale, as in drug delivery systems, to the macroscale of fully implantable devices. The integration of ensemble machine learning models, capable of predicting stability with an Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.988, now offers a powerful tool to accelerate the discovery of robust biomedical materials, moving beyond traditional trial-and-error approaches [1].

Fundamental Stability Concepts and Mechanisms of Degradation

The performance and safety of inorganic biomaterials are governed by their resistance to various degradation pathways in biological environments. Understanding these fundamental concepts is crucial for designing materials with long-term stability.

Thermodynamic versus Kinetic Stability: Thermodynamic stability indicates a material's inherent state of lowest free energy in a biological environment. A material with high thermodynamic stability has a very negative formation energy and resides on the convex hull of the phase diagram, showing no tendency to decompose into other phases [1]. In contrast, kinetic stability refers to a material's persistence in a metastable state due to slow transformation rates, even if it is not the lowest energy state. Many functional biomaterials rely on kinetic stability, which can be compromised by biological catalysts, pH changes, or enzymatic activity [25] [28].

Primary Degradation Mechanisms:

- Electrochemical Corrosion: This is a predominant failure mechanism for metallic implants and nanoparticles. In the presence of bodily fluids, which act as an electrolyte, galvanic couples can form between different phases or materials, leading to the anodic dissolution of metal ions. This process is governed by the material's electrochemical potential and the physiological environment's chloride content and pH [25].

- Hydrolytic Dissolution: Ceramics, glasses, and silica-based materials are susceptible to the breakdown of their network structure by water molecules. The rate of this process is highly dependent on pH; for example, doped mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) show accelerated degradation and drug release under acidic conditions mimicking the tumor microenvironment [25].

- Phase Transformation: Some materials may undergo phase changes at body temperature or in response to local biological stresses. These transformations can alter mechanical properties, such as ductility and strength, and potentially lead to implant failure. Techniques like severe plastic deformation are used to create microstructures that resist such transformations [25].

Table 1: Key Degradation Mechanisms for Inorganic Biomaterials in Physiological Environments

| Mechanism | Materials Most Affected | Primary Consequences | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical Corrosion | Metallic alloys (e.g., Zn-Mg, Co-Cr) | Release of metal ions, loss of mechanical integrity, local tissue inflammation | pH, chloride concentration, presence of inflammatory cells, galvanic coupling |

| Hydrolytic Dissolution | Bioceramics, Mesoporous Silica | Loss of structural integrity, premature release of therapeutic payload | pH, temperature, material porosity and doping (e.g., Ca2+, Mg2+) |

| Phase Transformation | Shape-memory alloys, certain ceramics | Alteration of mechanical properties (e.g., embrittlement), device failure | Mechanical stress, temperature fluctuations, cyclic loading |

Stability Challenges in Drug Delivery Systems

Drug delivery systems, particularly those based on nanomaterials, face unique stability challenges as they must navigate the body's compartments to deliver their payload to a specific target. The stability of these nanocarriers directly impacts drug bioavailability, therapeutic efficacy, and potential side effects.

Nanocarrier Instability and Premature Release: A primary challenge is maintaining the integrity of the carrier until it reaches the target site. For instance, inorganic-organic hybrid nanoarchitectonics are engineered to have enhanced stability in circulation but responsive release at the tumor site via stimuli like pH or enzymes [26]. However, thermodynamic instability can cause premature drug leakage. Research on Ca-Mg-doped mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) has shown that doping, while useful for pH-responsive release, can lower the free energy of the system, thereby reducing its overall stability and leading to accelerated release profiles [25].

Surface-Body Fluid Interactions and Opsonization: The surface of any nanomaterial immediately interacts with biomolecules upon entry into the bloodstream, leading to protein adsorption that forms a "protein corona." This corona can mask targeting ligands and trigger recognition by the immune system (opsonization), resulting in rapid clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system. Strategies to mitigate this include engineering surfaces with stealth coatings like polyethylene glycol (PEG) or using biomimetic membranes [26] [29].

Barrier Penetration and Structural Integrity: Effective drug delivery to the central nervous system (CNS) requires crossing the formidable blood-brain barrier (BBB). Nanomaterials must be stable enough to withstand the BBB's efflux pumps and enzymatic environment without degrading. A key instability challenge here is the trade-off between creating a material that is stable for transit but can still efficiently release its therapeutic cargo at the desired location within the CNS [29].

Diagram 1: Stability challenges and mitigation in nanocarrier drug delivery.

Stability Challenges in Implantable Devices

Implantable medical devices, particularly active implantable drug delivery systems (AIDDS), present a complex stability challenge where materials must function reliably for years or even decades within the harsh in vivo environment.

Material-Biointerface Stability: The long-term integrity of the device's housing and internal components is critical. For example, Zn-based alloys are being investigated as biodegradable materials for intracorporeal implants due to their lower cytotoxicity compared to pure Zn. However, controlling their degradation rate to match the tissue healing process while maintaining mechanical strength is a significant stability challenge. Studies show that techniques like Equal Channel Angular Pressing (ECAP) can refine the microstructure of Zn-Mg alloys, simultaneously enhancing their strength and ductility for improved performance as orthopedic implants [25].

Power System and Electronics Stability: AIDDS are characterized by their active, energy-dependent control over drug release. These systems integrate power sources (batteries or wireless power transfer), control electronics, and communication interfaces. The thermodynamic stability of battery components and the integrity of microelectronics are paramount for the device's functional lifespan. Corrosion or failure of these internal systems can lead to catastrophic device failure, requiring surgical explanation [27].

Reservoir and Actuation Mechanism Stability: The core function of an AIDDS—controlled drug release—hinges on the stability of its drug reservoir and actuation mechanism. Challenges include ensuring the chemical stability of the therapeutic agent over long storage periods and preventing the denaturation of biologics. Furthermore, the actuation mechanism (e.g., micro-pumps, piezoelectric valves) must perform reliably for thousands of cycles without failure due to fatigue or fouling. The stability of these components directly impacts dosing accuracy and patient safety [27].

Table 2: Stability Challenges and Material Solutions for Implantable Devices

| Device Component | Primary Stability Challenge | Material & Engineering Solutions | Impact on Device Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Device Housing/Structural | Corrosion; Stress Cracking; Fatigue | Zn-Mg alloys processed via ECAP [25]; Biostable polymers (e.g., PEEK); Ceramic composites | Prevents structural failure and release of degradation products; maintains mechanical support. |

| Drug Reservoir | Chemical degradation of drug; Leaching; Permeability changes | Stable inorganic excipients (e.g., doped MSNs [25]); Hermetic sealing; Glass-lined reservoirs | Ensures drug potency and prevents excipient interaction over the implant's lifetime. |

| Actuation Mechanism | Mechanical wear; Fouling; Corrosion of moving parts | Piezoelectric ceramics; Corrosion-resistant metal alloys (e.g., Pt-Ir); Redundancy design | Guarantees precise, reliable dosing and on-demand drug release capabilities. |

| Power & Electronics | Battery electrolyte leakage; Circuit corrosion | Biocompatible encapsulation; Conformal coatings; Wireless power transfer to reduce sealed components [27] | Provides uninterrupted power and control, essential for closed-loop system operation. |

Advanced Characterization and Computational Prediction

The development of stable biomedical materials is being revolutionized by advanced characterization techniques that probe instability mechanisms and by machine learning models that predict thermodynamic stability, thereby accelerating the design cycle.

Experimental Characterization Techniques

A multi-technique approach is essential to fully understand material stability. As highlighted in studies on biomaterials and bone tissue, key methods include [25]:

- Scattering Techniques: Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) and neutron scattering allow for the structural characterization (size, shape, morphology) of nanostructured biomaterials on sub-millisecond timescales, capturing dynamic processes related to instability [25].

- Spectroscopic Methods: Vibrational spectroscopy like IR and Raman, as well as Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) and Electron Spin Resonance (ESR), provide information on chemical bonding, phase composition, and local environments, revealing chemical instability pathways [25].

- Microscopy and Thermal Analysis: High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) visualize morphological changes, defects, and corrosion initiation sites. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential thermal analysis (DTA) assess thermal stability and phase transformations [25].

- Atom Probe Tomography: This technique, as used in studies of oxide reduction, provides near-atomic-scale 3D compositional mapping, which is critical for understanding microstructural evolution and elemental segregation that precede material failure [28].

Computational Stability Prediction

Machine learning (ML) now offers a powerful alternative to resource-intensive experimental and theoretical methods for predicting stability.

- Ensemble Machine Learning Framework: To overcome the limitations and biases of single models, an ensemble framework based on stacked generalization (SG) has been proposed. This approach integrates three models, each based on distinct domain knowledge: Magpie (using atomic property statistics), Roost (modeling interatomic interactions as a graph), and a novel Electron Configuration Convolutional Neural Network (ECCNN). The resulting super learner, ECSG, achieves an Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.988 in predicting compound stability within the JARVIS database [1].

- High Sample Efficiency: A significant advantage of this ensemble approach is its sample efficiency; it requires only one-seventh of the data used by existing models to achieve the same performance, dramatically accelerating the discovery of new stable materials for biomedical applications [1].

Diagram 2: Ensemble ML model for predicting inorganic material stability.

Experimental Protocols for Stability Assessment

A standardized, multi-faceted experimental approach is required to reliably assess the thermodynamic and kinetic stability of inorganic biomaterials under physiologically relevant conditions.

Protocol for In Vitro Chemical Stability and Degradation

Objective: To quantify the chemical degradation rate and identify corrosion products of an inorganic material in simulated biological fluids. Materials:

- Test Material: Powder, disc, or device form of the inorganic compound (e.g., Zn-Mg alloy disc [25]).

- Simulated Body Fluid (SBF): Standard solution mimicking ion concentration of human blood plasma, pH-adjusted to 7.4 and 4.5 (lysosomal pH).

- Analytical Equipment: Inductively coupled plasma-atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES), scanning electron microscope (SEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD). Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare triplicate samples with standardized dimensions and surface finish. Accurately weigh each sample (initial mass, mâ‚€).

- Immersion Study: Immerse samples in SBF at 37°C under sterile, static conditions for predetermined periods (e.g., 1, 7, 30, 90 days). Use a volume-to-surface area ratio per relevant ISO standards.

- Post-Immersion Analysis:

- Solution Analysis: At each time point, analyze the immersion medium using ICP-AES to quantify the concentration of released metal ions.

- Surface Analysis: Examine the material surface with SEM for pitting, cracking, or coating delamination. Use XRD to identify crystalline corrosion products and phase transformations.

- Mass Change: Gently clean and dry the samples, then record the final mass (m_f) to calculate the degradation rate. Data Interpretation: Plot ion release profiles and mass loss over time. Correlate surface morphology changes with chemical data to propose a degradation mechanism.

Protocol for Thermodynamic Stability Prediction via Machine Learning

Objective: To employ the ECSG ensemble machine learning model to predict the thermodynamic stability of a novel inorganic compound prior to synthesis. Materials:

- Computational Resources: Workstation with Python/R environment and necessary ML libraries (e.g., scikit-learn, PyTorch).

- Input Data: The chemical formula of the candidate compound.

- Reference Databases: Pre-trained ECSG model, which was trained on data from the Materials Project (MP) and JARVIS databases [1]. Methodology:

- Feature Encoding: Encode the chemical formula into the three distinct input representations required by the base models:

- For ECCNN: Generate an electron configuration matrix (118 elements × 168 features × 8 channels) based on the electron orbital structure of the constituent atoms [1].

- For Roost: Represent the formula as a complete graph where nodes are elements and edges represent stoichiometric relationships [1].

- For Magpie: Calculate statistical features (mean, range, mode, etc.) of fundamental atomic properties for the composition [1].

- Model Inference: Feed the encoded inputs into the pre-trained ECCNN, Roost, and Magpie base models to obtain initial stability scores (e.g., probability of stability).

- Stacked Generalization: Use the outputs of the base models as features for the meta-level model (a logistic regressor or simple neural network), which produces the final, refined stability prediction. Data Interpretation: The model outputs a probability and a binary classification (stable/unstable). A stable prediction indicates the compound is likely to reside on or near the convex hull, making it a promising candidate for synthesis and further testing [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating Inorganic Biomaterial Stability

| Reagent / Material | Composition / Type | Primary Function in Stability Research |

|---|---|---|

| Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) | Inorganic ion solution (Naâº, Kâº, Mg²âº, Ca²âº, Clâ», HCO₃â», HPO₄²â») | Provides an in vitro environment mimicking blood plasma for corrosion and degradation studies [25]. |

| Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles (MSNs) | SiOâ‚‚ with tunable pore structure | Serves as a model drug carrier system to study the effect of doping (e.g., Ca²âº, Mg²âº) on hydrolytic stability and pH-responsive release [25]. |

| Zn-Based Biodegradable Alloys | Zn with alloying elements (e.g., Mg, Ca, Sr) | Acts as a test material for investigating the correlation between microstructure (refined by ECAP) and degradation rate in physiological environments [25]. |

| Electron Configuration Encoder | Software algorithm (Python-based) | Converts a material's chemical composition into a numerical matrix based on electron orbitals, serving as input for the ECCNN stability prediction model [1]. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) Encoder | Software algorithm (e.g., Roost) | Represents a chemical formula as a graph of atoms to model interatomic interactions and predict formation energy and stability [1]. |

| Propachlor-2-hydroxy | Propachlor-2-hydroxy, CAS:42404-06-8, MF:C11H15NO2, MW:193.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| bromoethyne | bromoethyne, CAS:593-61-3, MF:C2HBr, MW:104.93 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Computational Methods for Stability Prediction and Material Design

Predicting the thermodynamic stability of inorganic compounds represents a fundamental challenge in accelerating the discovery of novel materials. The thermodynamic stability of a material, typically represented by its decomposition energy (ΔHd), determines whether a compound can be synthesized and persist under operational conditions without degrading into more stable phases [1]. Conventional approaches for determining stability through experimental investigation or density functional theory (DFT) calculations consume substantial computational resources and time, creating a bottleneck in materials development pipelines [1]. The extensive compositional space of potential materials, compared to the minute fraction that can be feasibly synthesized in laboratory settings, creates a "needle in a haystack" problem that necessitates effective computational strategies to constrict the exploration space [1].