Predicting Synthesizability of Crystalline Inorganic Materials: From AI Models to Real-World Applications in Drug Development

The reliable prediction of whether a hypothetical inorganic crystalline material can be synthesized is a critical challenge in materials science and drug development.

Predicting Synthesizability of Crystalline Inorganic Materials: From AI Models to Real-World Applications in Drug Development

Abstract

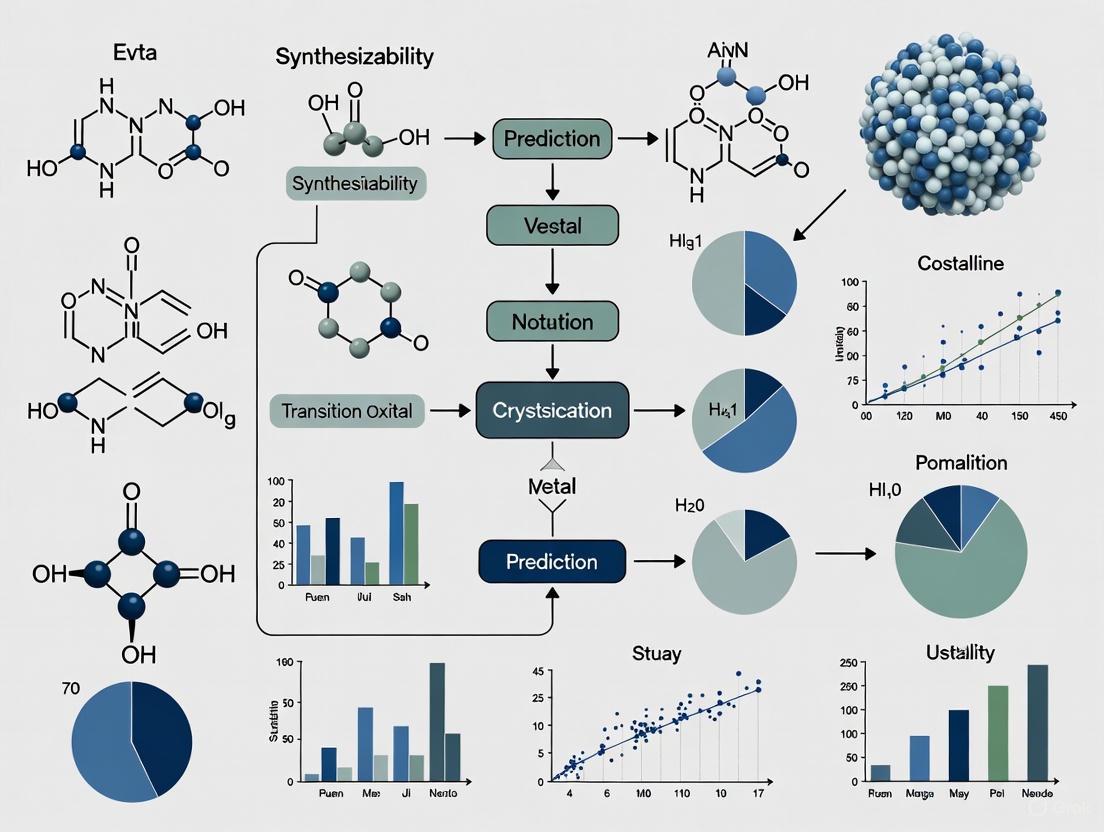

The reliable prediction of whether a hypothetical inorganic crystalline material can be synthesized is a critical challenge in materials science and drug development. This article provides a comprehensive overview of the field, exploring the fundamental principles that govern synthesizability and the limitations of traditional proxy metrics like thermodynamic stability. It delves into the latest computational methodologies, including deep learning models like SynthNN and groundbreaking large language models (CSLLM) that achieve unprecedented accuracy. The content covers strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing predictions, even with limited negative data, and offers a comparative analysis of different approaches against human experts and traditional methods. Finally, the article synthesizes key takeaways and discusses the profound implications of accurate synthesizability prediction for accelerating the discovery of novel pharmaceutical solid forms, such as polymorphs and co-crystals, thereby de-risking the drug development pipeline.

The Synthesizability Challenge: Why Predicting Crystal Formation is Fundamental to Materials Discovery

FAQs on Fundamental Concepts

What is synthesizability in materials science? In materials science, synthesizability refers to whether a hypothetical material is synthetically accessible through current experimental capabilities, regardless of whether it has been synthesized yet [1]. It is a prediction of experimental realizability, distinct from thermodynamic stability, as many metastable structures can be synthesized, and many stable structures have not been [1] [2].

Why is thermodynamic stability an insufficient predictor of synthesizability? While often used as a proxy, thermodynamic stability alone is an insufficient predictor. Formation energy or energy above the convex hull fails to account for kinetic stabilization and non-physical factors influencing synthesis [1]. Experiments confirm that numerous structures with favorable formation energies remain unsynthesized, while various metastable structures are routinely made [2].

What is the difference between general and in-house synthesizability? General synthesizability assumes near-infinite building block availability from commercial sources [3]. In-house synthesizability is a more practical concept for specific laboratory settings, considering only a limited, locally available stock of building blocks. Research shows synthesis planning with only ~6,000 in-house building blocks can achieve solvability rates only about 12% lower than using 17.4 million commercial building blocks, though routes may be two steps longer on average [3].

What are common computational approaches to predict synthesizability? Approaches can be categorized by their input requirements:

- Composition-Based Models: These use only the chemical formula, making them fast and applicable for high-throughput screening of hypothetical materials where structure is unknown. Example: SynthNN [1].

- Structure-Based Models: These require the full 3D crystal structure and generally offer higher accuracy. Examples: SyntheFormer, CSLLM [4] [2].

- Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning: A common technique where models are trained on known synthesized materials (positives) and artificially generated unsynthesized materials (treated as unlabeled) [4] [1] [5].

- Large Language Models (LLMs): Specialized LLMs fine-tuned on text representations of crystal structures can achieve high prediction accuracy and also suggest synthetic methods and precursors. Example: Crystal Synthesis LLM (CSLLM) [2].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge: My computationally predicted, high-scoring material fails to synthesize. This is a central challenge in the field. Potential causes and solutions include:

- Cause 1: Over-reliance on a Single Metric. A high synthesizability score is a probabilistic guide, not a guarantee.

- Solution: Adopt a multi-faceted validation approach. Cross-reference the prediction with other models and, crucially, check its thermodynamic stability by calculating its energy above the convex hull using Density Functional Theory (DFT) [5].

- Cause 2: Precursor Inavailability. The synthesis route suggested by computer-aided synthesis planning (CASP) may require building blocks you cannot access.

- Solution: Implement an "in-house synthesizability" filter. Retrain or select synthesizability models based on your local inventory of building blocks to ensure predictions are aligned with your lab's capabilities [3].

- Cause 3: Kinetic Barriers. The material may have a low-energy ground state, but the kinetic pathway to form it is hindered.

- Solution: Explore alternative synthesis conditions. The CSLLM framework can suggest different synthetic methods (e.g., solid-state vs. solution), which can circumvent kinetic traps [2].

Challenge: I have a novel composition; how do I predict its synthesizability without a known crystal structure? For novel compositions where the atomic structure is unknown, structure-agnostic models are required.

- Solution: Use a composition-based model like SynthNN [1]. These models learn from the distribution of known synthesized compositions and can identify promising chemical formulas without structural information, making them ideal for the initial screening of vast compositional spaces.

Challenge: How can I efficiently screen millions of candidate structures for synthesizability? Running full DFT calculations or complex synthesis planning on millions of candidates is computationally prohibitive.

- Solution: Implement a multi-stage screening funnel. First, use a fast composition-based or structure-based ML model to filter out the vast majority of candidates with low synthesizability scores. Then, apply more computationally intensive methods (like DFT or detailed CASP) only to the top candidates that pass the initial filter [2] [5].

Performance Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

The table below summarizes quantitative performance data for various computational methods, highlighting the evolution and state-of-the-art in the field.

Table 1: Key performance metrics of different synthesizability prediction methods from literature.

| Model Name | Input Type | Key Methodology | Reported Performance | Reference / Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charge-Balancing | Composition | Applies net neutral ionic charge rule | Only 37% of known synthesized ICSD materials are charge-balanced [1] | (npj Comput Mater, 2023) [1] |

| SynthNN | Composition | Deep learning on known compositions | Outperformed 20 human experts (1.5x higher precision) [1] | (npj Comput Mater, 2023) [1] |

| SyntheFormer | Crystal Structure | Hierarchical Transformer + PU Learning | Test AUC: 0.735; 97.6% recall at 94.2% coverage [4] | (arXiv, 2025) [4] |

| CSLLM (Synthesizability LLM) | Crystal Structure | Fine-tuned Large Language Model | Accuracy: 98.6%, significantly outperforming energy-based methods [2] | (Nat Commun, 2025) [2] |

| In-house Synthesizability Score | Molecule (Building Blocks) | CASP-based score adapted for local resources | Enables identification of active, synthesizable drug candidates [3] | (BMC Bioinformatics, 2025) [3] |

Experimental Protocol: Synthesizability-Driven Crystal Structure Prediction

This protocol outlines the data-driven workflow for predicting synthesizable inorganic crystal structures, integrating methods from recent literature [5].

Objective: To identify low-energy, synthesizable crystal structures for a target chemical composition.

Workflow Overview: The process involves generating candidate structures derived from known prototypes, intelligently filtering promising configuration subspaces, and evaluating the final candidates for both energy and synthesizability.

Materials and Computational Resources:

Table 2: Essential research reagents and computational tools for synthesizability-driven CSP.

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Prototype Database | A curated set of crystallographic prototypes for structure derivation. | Materials Project (MP) [5] |

| Group-Subgroup Tool | Software to construct symmetry-reduction paths for space groups. | SUBGROUPGRAPH [5] |

| Wyckoff Encode | A method to label and classify configuration subspaces. | Custom implementation [5] |

| ML Synthesizability Model | A pre-trained model to score structure synthesizability. | Synthesizability LLM (CSLLM) [2], SyntheFormer [4] |

| DFT Code | Software for first-principles energy and structure calculation. | VASP [2] |

| Building Block Library | A list of commercially or in-house available chemical precursors. | Zinc (commercial), Led3 (in-house) [3] |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Structure Derivation via Group-Subgroup Relations:

- Input: A database of synthesized prototype structures (e.g., standardized structures from the Materials Project).

- Process: For a given target composition, identify all non-conjugate group-subgroup transformation chains from the prototype database. Use these chains to guide element substitution, systematically generating derivative candidate structures that retain spatial arrangements of known materials [5].

Subspace Identification and Filtering:

- Process: Classify all derived candidate structures into distinct configuration subspaces using their Wyckoff encode—a compact descriptor of the symmetry and occupation of Wyckoff positions.

- Filtering: Use a pre-trained machine learning model to predict the probability of each subspace containing synthesizable structures. Select only the most promising subspaces for further, computationally expensive analysis. This "divide-and-conquer" strategy dramatically improves search efficiency [5].

Structural Relaxation and Final Evaluation:

- Process: Perform ab initio structural relaxation (e.g., using DFT) on all candidates within the selected promising subspaces to determine their low-energy atomic configurations.

- Final Screening: Apply a high-fidelity, structure-based synthesizability evaluation model (e.g., a fine-tuned synthesizability LLM) to the relaxed structures. The final output is a list of candidates that are both thermodynamically favorable and predicted to be highly synthesizable [2] [5].

FAQs: Understanding Synthesizability Prediction

What is the core limitation of using formation energy to predict synthesizability?

Formation energy, often calculated via Density Functional Theory (DFT), is a poor proxy for synthesizability because it only assesses thermodynamic stability at zero Kelvin. It fails to account for finite-temperature effects, kinetic factors, and complex experimental conditions that govern whether a material can actually be synthesized.

- Overlooks Metastable Phases: Many experimentally synthesized materials are metastable. For instance, the second most common phase of SiOâ‚‚, cristobalite, is not listed among the 21 SiOâ‚‚ structures found within 0.01 eV of the convex hull in the Materials Project, demonstrating that thermodynamic stability alone is an incomplete filter [6].

- High False Negatives: DFT-based formation energy calculations only capture about 50% of synthesized inorganic crystalline materials because they cannot account for kinetic stabilization [1].

Why is the common practice of charge-balancing an inadequate proxy for synthesizability?

Charge-balancing is an inflexible, chemically simplistic heuristic. It assumes a material is synthesizable only if it has a net neutral ionic charge based on common oxidation states. However, real-world synthesized materials frequently violate this rule due to diverse bonding environments.

- Low Predictive Power: Analysis shows that only 37% of all known synthesized inorganic materials in the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) are charge-balanced according to common oxidation states. The performance is even worse for specific classes like ionic binary cesium compounds, where only 23% of known compounds are charge-balanced [1].

- Fails for Metallic/Covalent Systems: The charge-neutrality constraint cannot accurately describe materials with metallic or covalent bonding character [1].

How do modern machine learning models address these limitations?

Modern ML models learn the complex, multi-faceted "chemistry of synthesizability" directly from vast databases of experimentally realized materials, moving beyond single-proxy metrics.

- Learned Chemical Principles: Models like SynthNN, which use only chemical composition, can learn advanced chemical principles like charge-balancing, chemical family relationships, and ionicity from the data itself, without prior chemical knowledge being explicitly programmed [1].

- Integrated Signals: State-of-the-art pipelines now combine complementary signals from both composition and crystal structure. Composition signals govern elemental chemistry and precursor availability, while structural signals capture local coordination and motif stability, leading to more robust predictions [6].

What is the practical performance of these data-driven models?

Data-driven synthesizability models significantly outperform traditional thermodynamic and heuristic methods in head-to-head comparisons.

The table below summarizes the quantitative performance of various approaches as reported in recent literature:

| Method / Model | Reported Performance | Key Limitation / Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Charge-Balancing | 37% of known synthesized materials are charge-balanced [1] | Inflexible; fails for many material classes. |

| Formation Energy (DFT) | Captures ~50% of synthesized materials [1] | Misses metastable phases and kinetic effects. |

| SynthNN (Composition ML) | 7x higher precision than DFT; 1.5x higher precision than best human expert [1] | Does not use structural information. |

| CSLLM (Structure LLM) | 98.6% accuracy on test data [2] | Requires structural input, which may be unknown for novel materials. |

| Synthesizability Pipeline | Successfully synthesized 7 out of 16 predicted targets [6] | Integrates composition, structure, and synthesis planning. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: My computationally discovered, thermodynamically stable material cannot be synthesized.

This is a common problem when discovery workflows rely solely on formation energy. The material may be kinetically inaccessible or require a specific, unknown synthesis pathway.

Recommended Steps:

- Re-assess with a Synthesizability Model: Before experimental attempts, screen your candidate materials with a modern synthesizability predictor.

- Check for Metastable Phases: Ensure your assessment includes metastability. The Synthesizability-driven CSP framework uses symmetry-guided derivation from synthesized prototypes to identify realizable metastable candidates [5].

- Plan the Synthesis Pathway: Use retrosynthetic planning tools. For example, the Retro-Rank-In model can suggest viable solid-state precursors, and SyntMTE can predict required calcination temperatures [6].

Issue: High rates of false positives or false negatives in synthesizability screening.

This often stems from using an outdated or inappropriate screening method for your material class.

Recommended Steps:

- Audit Your Screening Protocol: Compare the performance of your current method (e.g., charge-balancing or energy-above-hull) against the benchmarks in the table above.

- Adopt a Hybrid Approach: Implement a two-stage screening process:

- Validate with Temporal Splitting: To ensure model robustness, test its performance on materials synthesized after the training data was collected, as done with SyntheFormer [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational and data resources essential for modern synthesizability prediction research.

| Item / Resource | Function | Key Feature / Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) | Source of positive (synthesized) examples for model training. | Contains experimentally reported crystalline inorganic structures [1] [2]. |

| Materials Project Database | Source of theoretical (unsynthesized) candidates and stability data. | Provides DFT-calculated properties and flags for theoretical structures [6]. |

| Atom2Vec / Composition Embeddings | Represents chemical formulas as numerical vectors for ML. | Learns optimal composition representation directly from data [1]. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Encodes crystal structure graphs for structure-aware prediction. | Models local coordination environments and long-range interactions [6]. |

| Crystal Structure Text Representation (e.g., Material String) | Converts crystal structures into a text format for LLM processing. | Enables fine-tuning of large language models for synthesizability tasks [2]. |

| Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning Algorithms | Trains classification models using only confirmed positive and unlabeled data. | Addresses the lack of confirmed "unsynthesizable" examples [1] [4]. |

| Retrosynthetic Planning Models (e.g., Retro-Rank-In) | Predicts viable precursor materials and reaction parameters. | Bridges the gap between a target material and a viable synthesis recipe [6]. |

| Triphenoxyaluminum | Triphenoxyaluminum, MF:C18H15AlO3, MW:306.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| C23H21BrN4O4S | C23H21BrN4O4S|Research Chemical|RUO | High-purity C23H21BrN4O4S for laboratory research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: A Synthesizability-Guided Pipeline for Material Discovery

This protocol is adapted from a state-of-the-art workflow that successfully synthesized novel materials [6].

1. Candidate Screening and Prioritization

- Input: A large pool of computational candidate structures (e.g., from GNoME, Materials Project).

- Action: Apply a unified synthesizability model that integrates composition (

f_c) and structure (f_s) encoders to generate a synthesizability score. - Prioritization: Instead of a probability threshold, use a rank-average ensemble to rank all candidates. This provides a robust relative ranking across the entire screening pool.

- Filtering: Apply practical filters (e.g., exclude platinoid elements, toxic compounds) to narrow the list to a shortlist of high-priority targets.

2. Synthesis Planning

- Precursor Suggestion: Feed the shortlisted targets into a precursor-suggestion model like Retro-Rank-In to generate a ranked list of viable solid-state precursors.

- Reaction Parameter Prediction: Use a model like SyntMTE to predict the required calcination temperature for the target phase.

- Final Preparation: Balance the chemical reaction and compute the corresponding precursor quantities.

3. High-Throughput Experimental Synthesis

- Batch Selection: Group targets by recipe similarity to enable parallel synthesis in a single furnace run.

- Execution: Weigh, grind, and calcine the precursor mixtures in a benchtop muffle furnace.

- Characterization: Verify the synthesis success automatically using X-ray diffraction (XRD).

Protocol: Building a Balanced Dataset for LLM Fine-Tuning

This protocol details the method used to create the high-quality dataset for the Crystal Synthesis LLM (CSLLM), which achieved 98.6% accuracy [2].

1. Curate Positive (Synthesizable) Examples

- Source: Extract ordered crystal structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD).

- Filtering: Apply constraints such as a maximum of 40 atoms per unit cell and 7 different elements. Exclude disordered structures.

2. Construct Negative (Non-Synthesizable) Examples

- Challenge: There is no definitive database of "unsynthesizable" materials.

- Solution: Use a pre-trained Positive-Unlabeled (PU) learning model to screen a vast pool of theoretical structures from multiple databases (Materials Project, OQMD, JARVIS, etc.).

- Selection: Calculate a CLscore for each theoretical structure. Select the structures with the lowest CLscores (e.g., < 0.1) as high-confidence negative examples. This creates a balanced and comprehensive dataset for training.

3. Create Efficient Text Representation

- Problem: Standard CIF or POSCAR files contain redundant information.

- Solution: Develop a concise "material string" representation that includes space group, lattice parameters, and a minimal set of atomic coordinates with their Wyckoff positions, making it efficient for LLM processing.

FAQs: Troubleshooting Solid Form Development

Q: What should I do if my crystallization occurs too rapidly, leading to incorporated impurities? A: Rapid crystallization can be slowed by several methods. First, place the solid back on the heat source and add a small amount of extra solvent (e.g., 1-2 mL per 100 mg of solid) to decrease supersaturation. Ensure you are using an appropriately sized flask; a shallow solvent pool in a large flask cools too quickly. Finally, insulate the cooling flask by placing it on a cork ring or paper towels and covering it with a watch glass to slow the cooling process [7].

Q: How can I initiate crystallization if no crystals form upon cooling? A: If your solution remains clear with no crystal formation, try these methods in order:

- Scratching: Scratch the inner surface of the flask with a glass stirring rod to provide nucleation sites.

- Seeding: Introduce a small seed crystal of the pure API or a speck of saved crude solid.

- Evaporation: Return the solution to the heat source and boil off a portion of the solvent (e.g., half) to increase supersaturation and cool again.

- Temperature: Lower the temperature of the cooling bath [7].

Q: How can I control or prevent the formation of an unwanted polymorph? A: Polymorphic transformations are often driven by variations in temperature, solvent, or agitation. To mitigate this:

- Seeding: Actively seed the solution with pre-formed crystals of the desired polymorph.

- Supersaturation Control: Carefully control cooling profiles and supersaturation levels to avoid conditions that favor the unwanted form.

- Solvent Engineering: Select a solvent or solvent mixture that stabilizes the crystal lattice of your target polymorph [8].

Q: What are the key regulatory considerations for developing a pharmaceutical cocrystal? A: Regulatory views differ by region. The USFDA classifies cocrystals as Drug Product Intermediates (DPI), similar to polymorphs, and not as new Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs). The European Medicines Agency (EMA), however, requires demonstration that the cocrystal provides an improved safety and/or efficacy profile compared to the parent API; it may then be considered similar to a salt of the same API. For both agencies, you must demonstrate that the API and coformer interact via non-ionic bonds (e.g., hydrogen bonding) and that the cocrystal dissociates into its individual components before reaching the site of pharmacological action [9].

Q: My crystal yield is very poor after filtration. What could be the cause? A: A poor yield is often due to an excess of solvent, meaning too much of your compound remains dissolved in the mother liquor. To test this, dip a glass rod into the mother liquor and let it dry; a significant residue confirms the problem. To recover the material, you can boil away some solvent from the mother liquor and repeat the crystallization (a "second crop") or remove all solvent via rotary evaporation and attempt the crystallization again with a different solvent system [7].

Synthesizability Prediction Models for Inorganic Crystalline Materials

The following table summarizes quantitative data from recent machine learning models developed to predict the synthesizability of crystalline inorganic materials, a key consideration in broader materials research.

| Model Name | Core Approach | Reported Performance | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| SynthNN [10] | Deep learning model using learned atom embeddings from known compositions. | 7x higher precision than DFT-based formation energy; 1.5x higher precision than best human expert [10]. | Requires no prior chemical knowledge; learns principles like charge-balancing from data. |

| Synthesizability Score (SC) Model [11] | Deep learning classifier using Fourier-Transformed Crystal Properties (FTCP) representation. | 82.6% precision / 80.6% recall for ternary crystals; 88.6% true positive rate on post-2019 materials [11]. | Provides a synthesizability score (SC) for efficient screening of new material candidates. |

| XGBoost Classifier [12] | Supervised machine learning on experimental synthesis parameters (e.g., for Chemical Vapor Deposition). | Achieved an Area Under the ROC Curve (AUROC) of 0.96 for predicting successful synthesis [12]. | Optimizes real-world synthesis conditions and quantifies parameter importance. |

Experimental Protocols for Cocrystal Synthesis

1. Liquid-Assisted Grinding (LAG)

- Methodology: Place stoichiometric amounts of the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) and the coformer in a ball mill jar. Add a small, catalytic amount of a solvent (typically on the order of microliters per milligram of solid). The milling jar is then oscillated at a specific frequency for a predetermined time.

- Technical Insight: This method is highly effective for experimental screening. The small amount of solvent added in LAG, compared to neat grinding, acts as a molecular lubricant, facilitating faster reaction kinetics and often enabling the formation of cocrystals that would not be accessible otherwise [13].

2. Supercritical Fluid-Based Antisolvent Crystallization

- Methodology: Dissolve the API and coformer in a suitable organic solvent. This solution is then pumped into a vessel containing a supercritical fluid (most commonly COâ‚‚), which acts as an antisolvent. The supercritical fluid rapidly extracts the organic solvent, causing high supersaturation and precipitation of the cocrystal particles.

- Technical Insight: This technique offers excellent control over particle size and morphology and is considered a "green" alternative due to reduced solvent usage. It has been successfully demonstrated for systems like naproxen-nicotinamide and carbamazepine-saccharin [13].

3. Hot Melt Extrusion (HME)

- Methodology: Blend the API and coformer and feed the mixture into a twin-screw extruder. The materials are subjected to controlled heating and mixing as they are conveyed along the barrel. The resulting extrudate is collected and cooled.

- Technical Insight: HME is a solvent-free, continuous manufacturing process that is easily scalable, making it highly attractive for industrial production. It has been used for the continuous cocrystallization of carbamazepine with trans-cinnamic acid and nicotinamide [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Development |

|---|---|

| Coformers (GRAS listed) | Neutral molecules that form hydrogen bonds or other non-covalent interactions with the API to create the cocrystal lattice. Selecting Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) coformers simplifies regulatory approval [9]. |

| Polyethylene Oxide (PEO) | A polymer used in Hot Melt Extrusion (HME) as a carrier matrix. It can facilitate cocrystal formation during the extrusion process and is directly used in formulating the final dosage form [13]. |

| Supercritical COâ‚‚ | A versatile processing medium used as an antisolvent in supercritical fluid crystallization. It allows for the production of high-purity cocrystals with controlled particle size while minimizing organic solvent waste [13]. |

| Seeding Crystals | Small, pre-formed crystals of the target polymorph or cocrystal. They are introduced into a supersaturated solution to provide a nucleation template, ensuring the consistent and reproducible formation of the desired solid form [8]. |

| Computational Synthesizability Models (e.g., SynthNN) | Deep learning models that act as a virtual screening tool. They predict the likelihood of a hypothetical inorganic material being synthesizable, accelerating the discovery of new, stable crystalline compounds by prioritizing promising candidates for experimental work [10]. |

| 3-Nitroso-1H-indole | 3-Nitroso-1H-indole, CAS:76983-82-9, MF:C8H6N2O, MW:146.15 g/mol |

| 6-Bromochroman-3-ol | 6-Bromochroman-3-ol |

Workflow: Troubleshooting Solid Form Synthesis

The following diagram maps the logical decision process for diagnosing and resolving common issues in pharmaceutical crystallization.

Modern Approach: ML-Guided Synthesis Workflow

The field is moving towards integrating computational prediction to guide experimental efforts, as illustrated in this workflow for inorganic materials.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the core data challenge that Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning addresses in materials science? In materials science, particularly in predicting synthesizability, we have a definitive set of materials known to be synthesizable (positive examples) from databases like the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [1]. However, the set of materials that are unsynthesizable is unknown and vast; most hypothetical materials are unlabeled because failed syntheses are rarely reported. PU learning is a semi-supervised machine learning framework designed to learn classifiers from only positive and unlabeled examples, eliminating the need for definitively negative data [14] [15].

FAQ 2: Why are traditional metrics like thermodynamic stability insufficient for predicting synthesizability? While metrics like energy above the convex hull (ΔEhull) from density functional theory (DFT) are commonly used, they are insufficient because they primarily assess thermodynamic stability at 0 K [16]. Synthesizability is also governed by kinetic factors, growth conditions, and non-physical considerations like reactant cost and equipment availability [1]. Relying solely on thermodynamic stability can miss many synthesizable materials, as it only captures about 50% of known synthesized inorganic crystals [1].

FAQ 3: How does a PU learning model differentiate between synthesizable and unsynthesizable materials without negative examples? The core principle is that synthesizable materials are assumed to form coherent clusters in a feature space derived from their chemical and structural descriptors. The model learns the characteristics of the known positive examples. It then identifies other materials in the unlabeled set that share these characteristics as likely positives, while those that are dissimilar are treated as likely negatives [14] [15]. Advanced implementations use techniques like probabilistic reweighting of unlabeled examples [1] or contrastive learning to better separate these distributions [16].

FAQ 4: What are the consequences of having a low true positive rate (TPR) in a synthesizability model, and how can I improve it? A low TPR means your model is incorrectly classifying many known synthesizable materials as unsynthesizable. This can cause you to miss promising candidate materials during a screening process. To improve the TPR:

- Feature Engineering: Ensure your material descriptors (e.g., elemental properties, structural features) are representative. Incorporating features from contrastive learning has been shown to improve feature quality and TPR [16].

- Model Choice: Experiment with different classifiers. While decision trees are common [15], graph neural networks (GNNs) can capture complex structural relationships [17].

- Data Quality: Verify the integrity of your positive set. Using a large and diverse set of known materials from authoritative databases like ICSD or the Materials Project is crucial [1] [15].

FAQ 5: My model has a high false positive rate, suggesting many materials are synthesizable when they are not. How can I increase the prediction precision? A high false positive rate is a common challenge, as the unlabeled set contains both unsynthesizable and not-yet-synthesized materials. To increase precision:

- Refine the PU Algorithm: Use methods that provide a reliable "probability of synthesizability" rather than a binary classification. This allows you to rank candidates and focus on the most promising ones [18].

- Incorporate Domain Knowledge: Integrate additional filters post-PU learning. For example, you can use the PU model's probability score in conjunction with DFT-calculated stability metrics to create a more stringent selection criterion [14].

- Model Tuning: The SynthNN model demonstrated that deep learning with atom embeddings can achieve 7x higher precision than using formation energy alone [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Model Performance and Low Accuracy

Symptoms: The trained PU model performs poorly on the test set, showing low accuracy, precision, or true positive rate.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verify Data Quality | A clean, canonicalized dataset. |

| Check for and remove duplicates in your positive set. Ensure chemical formulas are standardized and consistent. | ||

| 2 | Review Feature Set | A more discriminative feature space. |

| Re-evaluate your material descriptors. Incorporate a mix of compositional (e.g., elemental properties, atom embeddings [1]) and, if available, structural features (e.g., from crystal graphs [17]). | ||

| 3 | Validate PU Learning Assumptions | A more realistic model. |

| The PU model assumes the positive set is randomly sampled from the overall set of synthesizable materials. If your positive set is biased (e.g., only contains oxides), the model's performance will be limited. Try to source a diverse positive set. | ||

| 4 | Try an Advanced Architecture | Improved feature extraction and performance. |

| If using simple classifiers, consider a more sophisticated framework. For example, the Contrastive Positive-Unlabeled Learning (CPUL) model uses contrastive learning to extract better features before applying PU learning, leading to higher true positive rates and shorter training times [16]. |

Problem 2: Model Fails to Generalize to New Material Classes

Symptoms: The model works well on materials similar to those in the training set but fails to identify synthesizable candidates in a new chemical space (e.g., predicting perovskites when trained on MXenes).

Diagnosis and Resolution:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Assess Training Data Diversity | Identification of a data coverage gap. |

| The model cannot learn patterns it has never seen. Ensure your training data (positive and unlabeled sets) encompasses a broad range of elements and material families. | ||

| 2 | Incorporate Transfer Learning | A model adapted to a new domain with less data. |

| Start with a model pre-trained on a large, diverse dataset (e.g., the entire Materials Project). Then, fine-tune it on a smaller, domain-specific positive set (e.g., a perovskite dataset) [15] [14]. | ||

| 3 | Fuse Multiple Data Types | A more robust synthesizability score. |

| Combine the PU model's output with other relevant data. For perovskites, one can combine the PU learning output with DFT-computed energies and the existence of similar synthesized compounds to create a more generalizable synthesis likelihood forecast [14]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of Select PU Learning Models in Materials Science

This table summarizes the performance of different models as reported in the literature, providing a benchmark for your own experiments.

| Model Name | Application Focus | Key Methodology | Performance Metric | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SynthNN [1] | General Inorganic Crystals | Deep learning with atom embeddings, PU learning. | Precision | 7x higher than DFT formation energy |

| CPUL [16] | General Crystals (MP DB) | Contrastive Learning + PU Learning. | True Positive Rate | 0.91 (on Materials Project DB) |

| ElemwiseRetro [18] | Synthesis Recipe Prediction | Template-based Graph Neural Network. | Top-1 Accuracy | 78.6% |

| PU Model [15] | MXenes & Materials Project | Decision tree classifier with bootstrapping. | --- | Identified 18 new synthesizable MXenes |

Detailed Methodology: Implementing a Basic PU Learning Workflow

This protocol outlines the steps for building a synthesizability classifier using a PU learning approach, as commonly described in the literature [1] [15].

1. Data Curation:

- Positive Set (P): Compile a list of known synthesizable materials. A standard source is the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [1]. For a focused study, use domain-specific databases (e.g., a perovskite dataset) [14].

- Unlabeled Set (U): Construct a set of hypothetical or not-yet-synthesized materials. This can be generated by:

2. Feature Extraction (Featurization): Represent each material in a numerical form that a machine learning model can process.

- Compositional Features: Use tools like Matminer to generate features based only on the chemical formula (e.g., elemental property statistics) [15].

- Structural Features: If crystal structures are available, use graph representations where nodes are atoms and edges are bonds, processable by Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [17] [16].

- Learned Representations: Methods like

atom2veclearn an optimal representation of chemical formulas directly from the data [1].

3. Model Training with a PU Algorithm: A common and effective method is the bootstrap aggregation approach:

- Step 1: Randomly select a subset of examples from the unlabeled set (U) and temporarily label them as negative (N).

- Step 2: Train a standard binary classifier (e.g., a Decision Tree, Random Forest, or Neural Network) on the positive set (P) and the temporary negative set (N).

- Step 3: Use the trained classifier to predict probabilities on the entire unlabeled set (U).

- Step 4: Repeat Steps 1-3 multiple times with different random samples for the temporary negative set.

- Step 5: For each material in the unlabeled set, calculate its final synthesizability score as the average probability across all iterations [15]. This score represents its likelihood of being synthesizable.

Workflow and System Diagrams

PU Learning Workflow for Material Synthesizability

Contrastive PU Learning (CPUL) Architecture

| Item Name | Function / Application | Relevant Links / References |

|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) | The primary source for positive examples (synthesized inorganic crystals). | https://icsd.products.fiz-karlsruhe.de/ [1] |

| Materials Project (MP) Database | A rich source of both known (positive) and computationally hypothesized (unlabeled) materials with DFT-calculated properties. | https://materialsproject.org/ [16] [15] |

| pymatgen | A robust Python library for materials analysis; essential for parsing crystal structures and generating features. | https://pymatgen.org/ [16] |

| Matminer | A Python library for data mining and feature extraction from materials data. | https://hackingmaterials.lbl.gov/matminer/ [15] |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) Libraries | Frameworks for building structure-aware models (e.g., CGCNN, MEGNet). | [17] |

| pumml | A Python package specifically designed for Positive and Unlabeled materials machine learning. | GitHub: ncfrey/pumml [15] |

From Deep Learning to LLMs: A Guide to Modern Synthesizability Prediction Methods

SynthNN is a deep learning model specifically designed to predict the synthesizability of crystalline inorganic materials based solely on their chemical composition. Its development addresses a core challenge in materials science: reliably identifying which computationally predicted materials are synthetically accessible in a laboratory. Traditional methods for assessing synthesizability, such as checking for charge-balancing or using density functional theory (DFT) to calculate formation energies, often serve as poor proxies. For instance, charge-balancing fails to identify 63% of known synthesized materials, while DFT-based stability calculations capture only about 50% of synthesized inorganic crystalline materials [1].

SynthNN reformulates material discovery as a synthesizability classification task. It leverages the entire space of synthesized inorganic chemical compositions to make its predictions, learning the complex, underlying principles of synthesizability directly from the data of all experimentally realized materials, without requiring prior chemical knowledge or structural information [1]. This approach allows it to outperform not only computational baselines but also human experts, achieving 1.5× higher precision in material discovery tasks than the best human expert and completing the task five orders of magnitude faster [1].

Core Methodology and Experimental Protocols

Data Curation and the Positive-Unlabeled Learning Framework

A fundamental challenge in training a synthesizability predictor is the lack of confirmed negative examples (i.e., definitively unsynthesizable materials). Failed syntheses are rarely reported in the scientific literature. SynthNN addresses this through a Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning approach [1].

- Positive Examples: Synthesized materials are obtained from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), which represents a nearly complete history of reported, synthesized, and structurally characterized crystalline inorganic materials [1].

- Unlabeled Examples: A large set of artificially generated chemical formulas that are absent from the ICSD serves as the pool of unlabeled data, presumed to be mostly unsynthesizable. The model is trained on a Synthesizability Dataset that augments the positive ICSD examples with these artificially generated compositions. The ratio of artificial formulas to synthesized formulas (referred to as

N_synth) is a key model hyperparameter [1].

To account for the possibility that some "unlabeled" materials might be synthesizable but just not yet synthesized, SynthNN uses a semi-supervised approach that probabilistically reweights unlabeled examples based on their likelihood of being synthesizable [1] [19].

The atom2vec Model and Neural Network Architecture

SynthNN does not rely on pre-defined chemical descriptors. Instead, it uses a framework called atom2vec to learn an optimal representation of chemical formulas directly from the data [1].

- Learned Atom Embeddings: The model represents each chemical element with a dense vector (an embedding). The values in these embedding vectors are not fixed; they are parameters that are optimized alongside all other weights in the neural network during training. This allows the model to discover elemental relationships that are most relevant for predicting synthesizability [1].

- Network Input and Structure: The input to SynthNN is a chemical formula. The model processes this formula using its learned atom embeddings. The architecture consists of a deep neural network that takes this embedded representation and learns to map it to a synthesizability probability. The dimensionality of the atom embeddings and other architectural details are treated as hyperparameters [1].

Model Training and Performance Benchmarking

The model is trained to classify compositions as synthesizable or not. Its performance is benchmarked against standard baselines:

- Random Guessing: Predicts synthesizability randomly, weighted by class imbalance.

- Charge-Balancing: Predicts a material as synthesizable only if it is charge-balanced according to common oxidation states.

- DFT Formation Energy: A common computational proxy where materials with favorable (negative) formation energies are considered stable and thus potentially synthesizable.

SynthNN demonstrates a significant performance improvement, identifying synthesizable materials with 7× higher precision than DFT-calculated formation energies [1]. Remarkably, without being explicitly programmed with chemical rules, analysis of the trained model indicates that it independently learns fundamental chemical principles such as charge-balancing, chemical family relationships, and ionicity, and uses these to inform its predictions [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential components for working with and understanding SynthNN.

| Component | Function & Description | Relevance in SynthNN Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) | A comprehensive database of experimentally synthesized and structurally characterized inorganic crystals. Serves as the ground-truth source for synthesizable ("positive") materials [1]. | The primary source of training data. The model's knowledge is derived from the patterns within this database. |

| Artificially Generated Compositions | A large set of plausible but (likely) unsynthesized chemical formulas. Generated to span the space of possible inorganic compositions [1]. | Serves as the pool of "unlabeled" data in the PU learning framework, allowing the model to learn distinctions between synthesized and non-synthesized spaces. |

| atom2vec Representation | A learned, numerical representation of each chemical element. The values are optimized during training to best predict synthesizability [1]. | Replaces traditional, fixed chemical descriptors (e.g., electronegativity, atomic radius), allowing the model to discover its own relevant features. |

| Pre-trained SynthNN Model | A deep neural network whose weights have already been optimized on the large-scale synthesizability dataset. Available via the official GitHub repository [20]. | Allows researchers to make predictions on new compositions without the computational cost of training a new model from scratch. |

| Decision Threshold | A user-defined probability value (between 0 and 1) above which a material is classified as "synthesizable." [20] | A critical parameter for deployment. A lower threshold increases recall (finds more synthesizable materials) but reduces precision (more false positives), and vice-versa. |

| 1-Phenyl-1-decanol | 1-Phenyl-1-decanol, CAS:21078-95-5, MF:C16H26O, MW:234.38 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Erythropterin | Erythropterin, CAS:7449-03-8, MF:C9H7N5O5, MW:265.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Performance Metrics and Interpretation

When using the pre-trained SynthNN model, understanding its output and the associated performance trade-offs is crucial. The model outputs a probability score. The user must select a decision threshold to convert this probability into a binary synthesizability classification. The table below, derived from the model's performance on a dataset with a 20:1 ratio of unsynthesized to synthesized examples, guides this choice [20].

Table 2: SynthNN performance at various decision thresholds. A threshold of 0.10 means any material with a SynthNN output >0.10 is classified as synthesizable [20].

| Decision Threshold | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|

| 0.10 | 0.239 | 0.859 |

| 0.20 | 0.337 | 0.783 |

| 0.30 | 0.419 | 0.721 |

| 0.40 | 0.491 | 0.658 |

| 0.50 | 0.563 | 0.604 |

| 0.60 | 0.628 | 0.545 |

| 0.70 | 0.702 | 0.483 |

| 0.80 | 0.765 | 0.404 |

| 0.90 | 0.851 | 0.294 |

How to interpret this table:

- Precision: Of all materials SynthNN labels as synthesizable, what fraction are truly synthesizable? A high precision means fewer "false alarms."

- Recall: Of all truly synthesizable materials, what fraction did SynthNN successfully identify? A high recall means fewer missed opportunities.

- Trade-off: Selecting a threshold is a balancing act. For initial screening where you want to capture most potential candidates, a lower threshold (e.g., 0.10-0.30) favoring high recall is appropriate. For prioritizing the most promising candidates for experimental follow-up, a higher threshold (e.g., 0.60-0.80) favoring high precision is better.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Q1: The model outputs a probability of 0.45 for my target material. Is it synthesizable? A: The raw probability is not a definitive "yes/no" answer. You must apply a decision threshold. At a threshold of 0.40, this material would be classified as synthesizable with an expected precision of about 49%. At a threshold of 0.50, it would be rejected. Your choice of threshold should align with your project's goals: favor recall (be more inclusive) or precision (be more selective) [20].

Q2: Why does SynthNN only require a chemical formula and not the crystal structure? A: For discovering new materials, the crystal structure is typically unknown. A composition-based model like SynthNN allows for screening billions of candidate compositions across the entire chemical space without this prerequisite. However, this also means SynthNN cannot differentiate between different polymorphs (different crystal structures) of the same composition [1].

Q3: How do I get synthesizability predictions for my own list of compositions?

A: The official GitHub repository provides a Jupyter Notebook (SynthNN_predict.ipynb) for this purpose. You can load the pre-trained model and run your list of chemical formulas through it to obtain synthesizability scores [20].

Q4: Can I re-train SynthNN with my own data or for a specific class of materials?

A: Yes, the GitHub repository also includes a training notebook (train_SynthNN.ipynb). You can point it to your own files containing lists of synthesized (positive) and unsynthesized (negative) materials to train a custom model tailored to your specific domain [20].

Q5: What are the main limitations of SynthNN? A:

- Structure-Agnostic: It cannot predict the synthesizability of specific polymorphs.

- Data Bias: Its knowledge is limited to patterns in the ICSD and the generated negatives. It may be biased against novel material classes that are underrepresented in historical data.

- Dynamic World: Synthesizability evolves with new techniques. The model, trained on past data, may not fully capture future synthetic capabilities.

- No Synthesis Route: It predicts if a material can be synthesized, but not how (e.g., precursors, temperatures). Newer models like CSLLM are beginning to address this latter point [19].

Advanced Applications and Future Outlook

SynthNN represents a significant step toward integrating synthesizability constraints directly into computational materials screening workflows. Its high speed and precision enable it to act as a powerful filter, prioritizing candidate materials generated by high-throughput DFT calculations or generative models for experimental investigation [1].

The field continues to evolve rapidly. Subsequent research has built upon the foundation of models like SynthNN. For example, the Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM) framework extends beyond binary synthesizability classification. It uses fine-tuned LLMs to not only predict synthesizability with very high accuracy (98.6%) but also to suggest specific synthetic methods and even identify suitable precursors for solid-state synthesis [19]. Furthermore, integrated pipelines are now being demonstrated that combine a synthesizability score (which can consider both composition and structure) with automated synthesis planning and robotic execution, successfully synthesizing novel materials predicted by the model [6].

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the primary data sources for building and testing structure-aware synthesizability models? Reliable data is the foundation of any robust model. For crystalline materials, the following databases are commonly used.

- Table: Key Data Sources for Crystalline Materials Research

Data Source Description Common Use in Synthesizability Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [2] A comprehensive collection of experimentally synthesized crystal structures. Serves as the source of positive samples (known synthesizable materials). Materials Project (MP) [2] [16] A large database of computed crystal structures and properties. Used as a source of theoretical structures; often screened to create negative or unlabeled samples. JARVIS [2] [21] An integrated database for both 3D and 2D materials. Provides data for training and validating property prediction models.

Q2: My model is achieving high accuracy on the test set but fails to generalize on new, complex crystal structures. What could be wrong? This is a classic sign of overfitting or a dataset bias. The issue likely stems from the quality and diversity of your negative samples (non-synthesizable crystals). Since there is no direct database of unsynthesizable materials, researchers often generate them from theoretical databases. If this generation process is not rigorous, the model may learn simplistic shortcuts instead of the underlying principles of synthesizability [2] [16]. To address this:

- Refine your negative samples: Instead of treating all unobserved structures as negative, use a pre-trained Positive-Unlabeled (PU) model to assign a Crystal-Likeness Score (CLscore). Structures with a very low CLscore (e.g., <0.1) are higher-confidence negative samples [2].

- Ensure dataset balance: Verify that your training data has a balanced representation of different crystal systems (cubic, hexagonal, etc.) and a range of elemental compositions [2].

- Leverage transfer learning: If your target dataset is small, initialize your model with weights pre-trained on a large, general source dataset (like formation energy from the Materials Project). This can significantly improve generalization and performance on small datasets [21].

Q3: Are there alternatives to 3D convolutional networks for structure-aware property prediction? Yes, Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are a powerful and increasingly popular alternative. While 3D-CNNs operate on voxelized images, GNNs work directly on the crystal graph, where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges.

- Table: Comparison of Structure-Aware Model Architectures

Architecture Input Representation Key Advantage Example Model 3D Convolutional Network Voxelized 3D image (density grid) Intuitive; can capture complex spatial features. 3D-CNN [22] Graph Neural Network (GNN) Crystal structure graph (atoms, bonds) Directly models atomic interactions; inherently respects periodicity. ALIGNN [21]

For synthesizability prediction, recent research has also shown great success by fine-tuning Large Language Models (LLMs). These models use a specialized text representation of the crystal structure (a "material string") that encodes space group, lattice parameters, and Wyckoff positions, achieving state-of-the-art accuracy [2].

Q4: How can I incorporate synthesizability constraints directly into a generative model for material design? This is a frontier research area. The most effective strategy is to move from a structure-centric to a synthesis-centric approach.

- Generate synthetic pathways: Instead of generating crystal structures directly, design models that output viable synthetic pathways using known reaction templates and purchasable building blocks. This ensures that every generated material has a proposed route to synthesis [23].

- Use retrosynthesis models: Integrate a retrosynthesis model directly into the optimization loop to evaluate and guide the generation process towards synthetically feasible molecules and materials [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Model performance is poor, with low accuracy on both training and validation sets. This indicates underfitting, which can be caused by inadequate feature extraction or a model that is too simple for the data complexity.

- Solution 1: Enhance feature representation.

- For 3D-CNN models, consider using 3D Gabor filters as a preprocessing step to better capture spectral-spatial features from the crystal volume [25].

- For graph-based models, ensure your input features include not only atom types but also bond angles and distances, as implemented in advanced GNNs like ALIGNN [21].

- Solution 2: Increase model capacity or use transfer learning.

- If using a 3D-CNN, you may need a deeper architecture. However, be cautious of overfitting with small datasets.

- A more efficient approach is to use a pre-trained model. A structure-aware GNN pre-trained on a large dataset like the Materials Project can be fine-tuned on your specific synthesizability data, drastically improving performance [21].

Problem: The model's predictions are inconsistent for different polymorphs of the same chemical composition. This is actually an expected and desired behavior of a truly structure-aware model. Properties, including synthesizability, can vary dramatically between polymorphs. If your model is not distinguishing between them, it is likely relying too heavily on compositional features alone.

- Solution: Verify model input.

- Ensure your model's input includes the full 3D structural information and not just the chemical formula. A model that only uses composition will fail to differentiate polymorphs and is not structure-aware [21]. The use of crystal graphs or 3D voxelized images inherently addresses this issue.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Building a Binary Classifier for Crystal Synthesizability using a 3D-CNN

This protocol outlines the steps to create a model that classifies a crystal structure as "synthesizable" or "non-synthesizable."

- Dataset Curation:

- Positive Data: Curate a set of synthesizable crystals from the ICSD. Filter for ordered structures and limit to a manageable unit cell size (e.g., ≤ 40 atoms) [2].

- Negative Data: Obtain theoretical structures from the Materials Project (MP). Use a pre-trained PU learning model to calculate a CLscore for each. Label structures with a CLscore below a strict threshold (e.g., 0.1) as negative samples. This creates a higher-quality negative set [2] [16].

- Data Preprocessing and Augmentation:

- Voxelization: Convert each crystal structure (CIF file) into a 3D voxel grid. The voxel values can represent electron density, atomic number, or other structural properties.

- Augmentation: Apply random 90-degree rotations to the 3D grid to augment your dataset and improve the model's rotational invariance [22].

- Model Training:

- Architecture: Design a 3D Convolutional Neural Network. The architecture should include multiple 3D convolutional and pooling layers to hierarchically learn features, followed by fully connected layers for classification.

- Training: Train the model on your curated dataset, using a balanced split for training, validation, and testing.

Protocol 2: Implementing a Transfer Learning Workflow using a Structure-Aware GNN

This protocol is useful when you have a small target dataset for your specific synthesizability task.

- Source Model Pre-training:

- Select a large source dataset with a fundamental property, such as formation energy from the Materials Project [21].

- Train a structure-aware GNN (like ALIGNN) on this source data. This model will learn robust, general-purpose representations of crystal structures.

- Knowledge Transfer:

- Fine-tuning: Use the weights of the pre-trained source model to initialize your target model. Then, further train (fine-tune) the entire model on your smaller, labeled synthesizability dataset [21].

- Feature Extraction: Alternatively, use the pre-trained model as a fixed feature extractor. Pass your synthesizability data through the model and extract features from an intermediate layer (e.g., after the GCN or ALIGNN layers). Use these features to train a separate, simpler classifier (e.g., a Support Vector Machine) [21].

- Evaluation:

- Compare the performance of the transfer learning model against a model trained from scratch on the target data alone. The transfer learning model is expected to achieve higher accuracy, especially when the target dataset is small [21].

- Table: Essential Computational Tools for Structure-Aware Modeling

Item Function Example / Note pymatgen A robust Python library for materials analysis. Used for parsing CIF files, manipulating crystal structures, and featurization [16]. ALIGNN A Graph Neural Network model that incorporates atomic bonds and bond angles. Provides state-of-the-art performance for a wide range of material property predictions [21]. Crystal-Likeness Score (CLscore) A metric to estimate the synthesizability of a theoretical structure. Generated by Positive-Unlabeled (PU) learning models; lower scores indicate lower synthesizability [2] [16]. Reaction Template Set A curated list of known chemical transformations. Used in synthesis-centric generative models (e.g., SynFormer) to ensure synthetic feasibility [23]. Materials API (MAPI) An interface to programmatically access data from the Materials Project. Essential for building automated data retrieval and model training pipelines [16].

Workflow Visualization

Synthesizability Prediction Workflow

Contrastive PU Learning Framework

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core function of the CSLLM framework? The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM) framework is designed to bridge the gap between theoretical materials design and experimental synthesis. It uses three specialized LLMs to predict whether an arbitrary 3D crystal structure can be synthesized, suggest the most likely synthesis method, and recommend suitable chemical precursors for the synthesis [2] [26].

Q2: How does CSLLM's accuracy compare to traditional stability-based screening methods? CSLLM significantly outperforms traditional methods. The Synthesizability LLM achieves a state-of-the-art accuracy of 98.6% on testing data. This is a substantial improvement over screening based on energy above hull (74.1% accuracy) or phonon stability (82.2% accuracy) [2].

Q3: My crystal structure is in a CIF file. How does CSLLM process it? CSLLM uses a specialized text representation called a "material string" for efficient processing. This string distills the essential crystal information—space group, lattice parameters, and atomic coordinates with Wyckoff positions—into a concise, human-readable format that the LLM can understand, avoiding the redundancy of a full CIF file [2].

Q4: What kind of data was used to train the CSLLM models? The models were trained on a large, balanced dataset of 150,120 crystal structures. This included 70,120 synthesizable structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) and 80,000 non-synthesizable structures identified from theoretical databases using a positive-unlabeled (PU) learning model [2].

Q5: Can CSLLM explain why it classifies a structure as non-synthesizable? Yes, a key advantage of using LLMs is their potential for explainability. By using appropriate prompts, a fine-tuned LLM can generate human-readable explanations for its synthesizability predictions, inferring the underlying physical or chemical rules that guided its decision [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Synthesizability Prediction Accuracy

Problem: The Synthesizability LLM is consistently classifying plausible structures as non-synthesizable, or vice-versa.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verify Input Data Format : Ensure your crystal structure is correctly converted into the "material string" format. Check for errors in lattice parameters, atomic symbols, or Wyckoff positions. | A correctly formatted input string that the LLM can parse. |

| 2 | Check Data Against Training Scope : Confirm your material's complexity (number of elements, unit cell size) falls within the model's training domain. The CSLLM was trained on structures with ≤7 elements and ≤40 atoms [2]. | Confidence that your query is within the model's designed capabilities. |

| 3 | Consult Alternative Metrics | A more holistic view of the structure's feasibility. |

| 4 | Leverage the Full Framework | A more comprehensive synthesis plan, validating the synthesizability prediction. |

The following workflow visualizes the diagnostic process for a poor prediction:

Issue 2: Ineffective or Unsuitable Precursor Recommendations

Problem: The Precursor LLM is suggesting precursors that are chemically implausible, unavailable, or inefficient for the target material.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Validate Precursor LLM Scope | Realistic expectations for the tool's output. |

| 2 | Calculate Reaction Thermodynamics | An energy-based ranking of the suggested precursors, filtering out highly unfavorable reactions. |

| 3 | Perform Combinatorial Analysis | A shortlist of the most promising and energetically favorable precursor pairs or sets. |

| 4 | Cross-Reference Experimental Databases | Corroboration of the LLM's suggestions with known, successful synthesis routes from literature. |

The logical flow for diagnosing precursor issues is outlined below:

CSLLM Performance Data

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of CSLLM Components [2]

| CSLLM Component | Primary Function | Key Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|

| Synthesizability LLM | Predicts if a 3D crystal structure is synthesizable | 98.6% accuracy on test data |

| Method LLM | Classifies the appropriate synthesis method (e.g., solid-state, solution) | 91.0% classification accuracy |

| Precursor LLM | Identifies suitable chemical precursors for synthesis | 80.2% success rate for common binary/ternary compounds |

Table 2: Comparison with Traditional Synthesizability Screening Methods [2]

| Screening Method | Basis of Prediction | Typical Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamic Stability | Energy above convex hull (≥0.1 eV/atom) | 74.1% |

| Kinetic Stability | Phonon spectrum lowest frequency (≥ -0.1 THz) | 82.2% |

| CSLLM (Synthesizability LLM) | Pattern learning from a vast dataset of synthesizable/non-synthesizable structures | 98.6% |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fine-Tuning the Synthesizability LLM

- Dataset Curation:

- Positive Samples: 70,120 experimentally verified, ordered crystal structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD). Filter for structures with ≤40 atoms and ≤7 different elements [2].

- Negative Samples: 80,000 theoretical structures with the lowest CLscore (a synthesizability score <0.1) from a pool of over 1.4 million entries in materials databases, screened using a pre-trained PU learning model [2].

- Text Representation: Convert all crystal structures from CIF format into the condensed "material string" representation. This includes space group, lattice parameters (a, b, c, α, β, γ), and atomic sites (element symbol and Wyckoff position) [2].

- Model Fine-Tuning: Use the constructed dataset to fine-tune a large language model. The training task is autoregressive, where the model learns to predict the next token in the sequence, thereby internalizing the patterns of synthesizable crystal structures [2] [28].

Protocol 2: Deploying CSLLM for High-Throughput Screening

- Input Preparation: Convert the candidate theoretical crystal structures (e.g., from generative models or high-throughput DFT calculations) into the "material string" format.

- Synthesizability Screening: Run the structures through the fine-tuned Synthesizability LLM to filter and retain only those predicted as synthesizable.

- Synthesis Planning: For the synthesizable candidates, use the Method LLM to propose a synthesis route and the Precursor LLM to suggest initial precursor chemicals.

- Property Prediction & Validation: Feed the screened, synthesizable structures into accurate Graph Neural Network (GNN) models for property prediction [2]. The final list of candidates with predicted properties and synthesis routes is ready for experimental validation.

The overall workflow of the CSLLM framework is summarized in the following diagram:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Resources for CSLLM-informed Research

| Item | Function / Description | Relevance to CSLLM Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Crystallographic Information File (CIF) | A standard text file format for representing crystallographic data [28]. | The primary source of structural information for a crystal. Must be converted to a "material string" for CSLLM input. |

| "Material String" Representation | A condensed text representation integrating space group, lattice parameters, and Wyckoff sites [2]. | Serves as the effective "language" for communicating crystal structures to the CSLLM framework. |

| Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning Model | A machine learning technique to identify negative examples (non-synthesizable structures) from a pool of unlabeled data [2]. | Critical for constructing the high-quality, balanced dataset used to train the Synthesizability LLM. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | A class of neural networks that operate on graph-structured data, used for predicting material properties [2]. | Used in conjunction with CSLLM to predict key properties of the screened, synthesizable candidate materials. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | A computational method for investigating the electronic structure of many-body systems. | Used to validate LLM predictions, calculate formation energies, and assess the thermodynamic favorability of suggested precursor reactions [2]. |

| Kanokoside D | Kanokoside D | Kanokoside D for research. This compound is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Mandyphos SL-M003-2 | Mandyphos SL-M003-2, MF:C60H42F24FeN2P2, MW:1364.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The discovery of novel inorganic crystalline materials is a cornerstone of advancements in energy, electronics, and decarbonization technologies. Computational screening and inverse design can generate millions of hypothetical candidate materials with promising properties. However, a central challenge remains: determining which of these theoretically proposed materials are synthetically accessible in a laboratory. The inability to accurately predict synthesizability creates a significant bottleneck, wasting computational and experimental resources on candidates that are fundamentally non-synthesizable. This technical support document, framed within a broader thesis on predicting the synthesizability of crystalline inorganic materials, provides a practical workflow and troubleshooting guide for integrating state-of-the-art synthesizability predictions into computational material screening pipelines. We address specific issues researchers might encounter, offering solutions based on current best practices and model capabilities.

FAQ: Synthesizability Prediction Fundamentals

What is the difference between thermodynamic stability and synthesizability?

Thermodynamic stability, often assessed via density functional theory (DFT) calculations of the energy above the convex hull, indicates whether a material is stable against decomposition into other phases at equilibrium. Synthesizability is a broader concept that encompasses whether a material can be experimentally realized, which may include metastable materials that are thermodynamically unstable but kinetically persistent. Relying solely on thermodynamic stability is an insufficient proxy for synthesizability, as many structures with favorable formation energies remain unsynthesized, while various metastable structures are successfully synthesized [2] [1].

My candidate material has a favorable formation energy. Why does the synthesizability model label it as non-synthesizable?

This is a common point of confusion. A favorable formation energy is a necessary but not sufficient condition for synthesizability. The material's kinetic stability, the potential energy landscape of its formation, and the existence of a viable synthetic pathway and precursors are also critical [29]. Advanced machine learning (ML) models are trained on historical synthesis data and learn complex patterns beyond simple thermodynamics. A non-synthesizable prediction suggests that, despite being energetically favorable, the material may lack a known kinetic pathway to its formation, require unavailable precursors, or possess structural features that have historically proven difficult to synthesize [2] [27].

Should I use a composition-based or a structure-based synthesizability model?

The choice depends on your discovery workflow and the information available.

- Composition-based models (e.g., SynthNN) are ideal for the initial stages of high-throughput screening where only the chemical formula is known. They can screen billions of candidates rapidly and learn chemical principles like charge-balancing and chemical family relationships [1].

- Structure-based models (e.g., CSLLM, PU-GPT-embedding) require the full crystal structure (atomic coordinates, lattice parameters, space group) and provide a more accurate assessment. They are essential for differentiating between polymorphs of the same composition and should be used for the final prioritization of candidates [2] [27]. The workflow often involves using a composition-based filter first, followed by a more rigorous structure-based check.

What does a "Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning" approach mean?

PU learning is a machine learning paradigm used when only positive examples (known synthesizable materials) and unlabeled examples (hypothetical materials, which are a mix of synthesizable and non-synthesizable) are available for training. It does not require a definitive set of "non-synthesizable" materials, which are rarely documented. These models, such as PU-CGCNN and PU-GPT-embedding, are trained to distinguish the characteristics of known synthesizable materials from the broader, unlabeled set, and they probabilistically weight the unlabeled data during training [27] [1]. This makes them particularly suited for the reality of materials discovery.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Scenarios

Scenario 1: Disagreement Between Property Prediction and Synthesizability Prediction

- Problem: A candidate material shows exceptional functional properties (e.g., high electrical conductivity, ideal band gap) in simulations but is assigned a low synthesizability score.

- Investigation & Solution:

- Verify Inputs: Ensure the crystal structure file (e.g., CIF, POSCAR) used for property calculation is identical to the one fed into the structure-based synthesizability model. Small distortions can significantly impact the prediction.

- Seek Explainability: Use explainable AI (XAI) tools or models with built-in explanation capabilities. For instance, fine-tuned Large Language Models (LLMs) can generate human-readable explanations for their synthesizability predictions, highlighting factors such as unusual coordination environments, unrealistic bond lengths, or the absence of known stable structural motifs [27] [30].

- Explore Metastability: Calculate the energy above the convex hull. If the material is metastable (e.g., within 50-100 meV/atom of the hull), it may still be synthesizable under non-equilibrium conditions. Cross-reference the synthesizability score with the stability metric for a holistic view [2].

- Iterative Redesign: Use the explanations from step 2 to guide minor structural modifications. For example, if the model flags a specific under-coordinated atom as a problem, consider if a different, isovalent element that prefers that coordination number could be substituted without drastically altering the electronic properties.

Scenario 2: Handling a Low-Confidence Prediction

- Problem: The synthesizability model returns a score near its decision threshold, indicating low confidence.

- Investigation & Solution:

- Uncertainty Quantification: Employ models that provide uncertainty estimates for their predictions. For example, the SyntheFormer framework incorporates uncertainty quantification, which helps identify candidates falling in a "gray area" [4].

- Consensus Modeling: Do not rely on a single model. Submit the candidate to multiple independent predictors (e.g., CSLLM, SynthNN, a thermodynamic stability checker). If a consensus emerges, you can act with greater confidence. The following table provides a comparison of modern synthesizability prediction tools:

Table 1: Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Tools and Datasets

| Tool / Model Name | Input Type | Core Methodology | Key Performance Metric | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSLLM [2] | Crystal Structure | Fine-tuned Large Language Models (LLMs) | 98.6% Accuracy | High-accuracy synthesizability & precursor prediction |

| PU-GPT-embedding [27] | Crystal Structure (as text) | LLM-derived embeddings + PU-classifier | Outperforms graph-based models | High-accuracy, cost-effective structure-based screening |

| SynthNN [1] | Chemical Composition | Deep Learning (Atom2Vec) + PU-learning | 7x higher precision than formation energy | Ultra-high-throughput composition-based screening |

| SyntheFormer [4] | Crystal Structure | Hierarchical Transformer + PU-learning | 97.6% Recall at 94.2% Coverage | Targeting metastable compounds with minimal missed discoveries |