Polymer-Induced Liquid Precursors (PILP): A Non-Classical Pathway for Advanced Biomaterials and Bone Regeneration

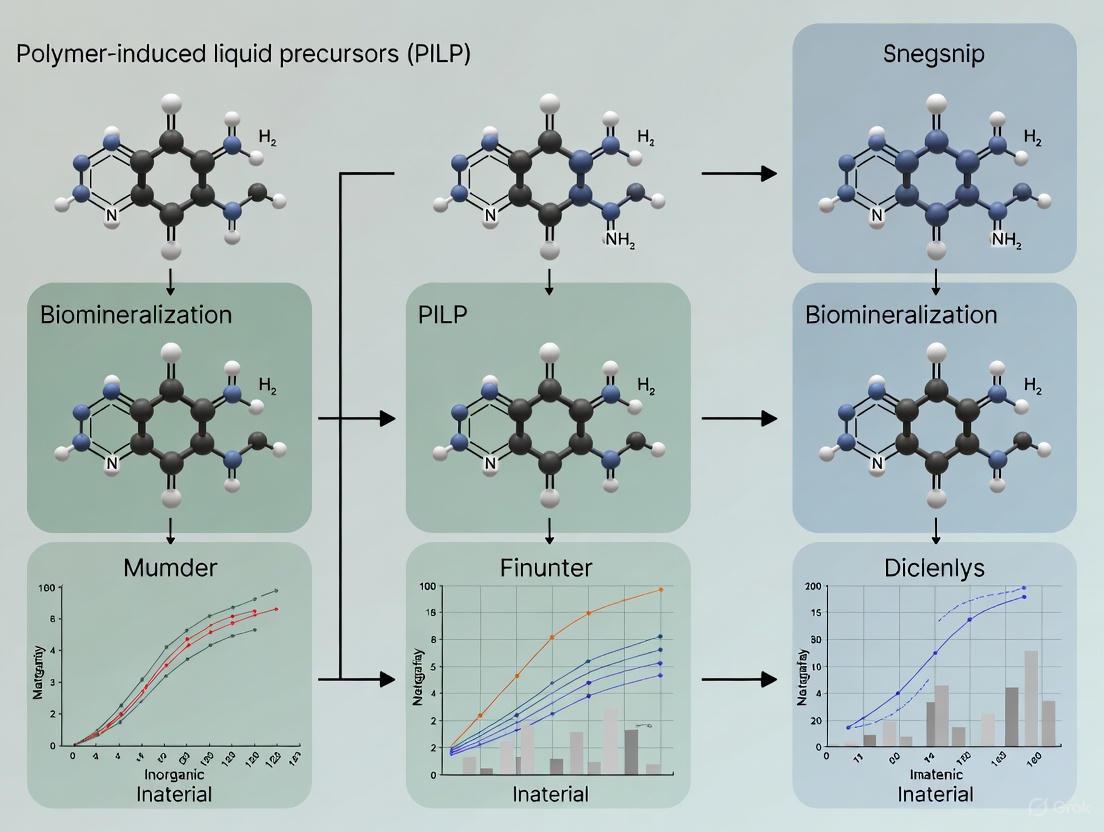

This article comprehensively examines the Polymer-Induced Liquid-Precursor (PILP) process, a transformative biomineralization pathway with significant implications for biomedical research and therapeutic development.

Polymer-Induced Liquid Precursors (PILP): A Non-Classical Pathway for Advanced Biomaterials and Bone Regeneration

Abstract

This article comprehensively examines the Polymer-Induced Liquid-Precursor (PILP) process, a transformative biomineralization pathway with significant implications for biomedical research and therapeutic development. We explore the foundational science behind PILP, from its discovery as a model system emulating natural biomineralization to its recently proposed re-conceptualization as a Colloid Assembly and Transformation (CAT) pathway. The content details methodological approaches for harnessing PILP in creating bone-like composites and repairing mineralized tissues, while addressing key troubleshooting parameters such as polymer selection and precursor stability. Through comparative analysis with classical crystallization and validation via in vitro and ex vivo studies, we demonstrate PILP's unique capability to produce intrafibrillar mineralized composites that closely mimic natural bone and dentin structure. This resource provides researchers and drug development professionals with both theoretical understanding and practical guidance for leveraging this innovative process in developing next-generation biomaterials and hard tissue repair strategies.

The PILP Process: Unraveling the Non-Classical Nucleation Pathway in Biomineralization

The field of biomineralization has undergone a revolutionary transformation over the past 25 years, largely paralleling the discovery and development of the polymer-induced liquid precursor (PILP) process [1]. This transformative concept has fundamentally challenged the long-standing dominance of classical nucleation theory (CNT) in explaining how crystals form from solution, particularly in biological systems. The PILP process, first introduced by Laurie B. Gower, has emerged as a powerful model system for investigating the role that biopolymers play in modulating biomineralization [1] [2]. At the heart of this paradigm shift is the recognition that many enigmatic features observed in biological minerals—such as the intricate hierarchical architectures of bone, teeth, and mollusk shells—can be elegantly explained through non-classical pathways involving liquid-phase precursors rather than conventional ion-by-ion addition [3] [1].

The implications of this shift extend far beyond theoretical interest, offering profound insights for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to control crystallization processes for biomedical applications. The PILP phenomenon demonstrates that charged polymers, particularly intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) commonly associated with biominerals, can trigger the separation of a liquid precursor phase that subsequently transforms into solid mineral [1] [2]. This pathway enables unprecedented control over mineral formation, allowing organisms to create complex crystalline architectures with remarkable precision—a capability that conventional crystallization methods cannot replicate. As this technical guide will explore, understanding and harnessing the PILP process opens new frontiers in biomimetic material design, targeted drug delivery, and tissue regeneration strategies.

Theoretical Foundations: Classical vs. Non-Classical Nucleation

The Classical Nucleation Theory Framework

Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT), first introduced by Gibbs in the 1870s, has served for over a century as the fundamental framework for understanding crystallization processes [3] [4]. CNT describes nucleation as a stochastic process where individual ions or molecules in solution assemble directly into crystalline nuclei through sequential addition. According to CNT, the formation of these nuclei is governed by a delicate balance between bulk energy reduction (which favors nucleation) and surface energy costs (which oppose it) [4]. This relationship is quantitatively expressed by the equation:

ΔG = 4/3πr³ΔGᵥ + 4πr²γ

Where ΔG represents the overall free energy change, r is the nucleus radius, ΔGᵥ is the volume free energy change per unit volume, and γ is the surface energy per unit area [4]. The critical nucleus size (r_crit) occurs at the maximum of this energy barrier, beyond which growth becomes energetically favorable:

r_crit = -2γ/ΔGᵥ

While CNT provides a mathematically elegant model, an increasing body of experimental evidence has revealed significant limitations in its ability to explain many crystallization phenomena, particularly in biological systems [4]. CNT assumes that nuclei possess the same internal structure and density as the final crystal, that surface energy remains constant regardless of nucleus size, and that nucleation occurs exclusively through the assembly of individual ions or molecules—assumptions that frequently fail in complex biological environments [5] [4].

The Non-Classical Perspective: PILP and Alternative Pathways

Non-classical nucleation theory challenges the fundamental premises of CNT by proposing that crystal formation can proceed through metastable precursor phases rather than direct ion-by-ion attachment [4]. The polymer-induced liquid precursor (PILP) process represents a particularly significant non-classical pathway in which charged polymers induce the formation of a dense, liquid-phase mineral precursor that can infiltrate and mold to organic templates before solidifying [3] [1]. This mechanism elegantly explains many features of biomineralization that confounded classical models, including the precise intrafibrillar mineralization of collagen fibers in bone and dentin [3].

The PILP process fundamentally differs from CNT in several key aspects. Rather than proceeding through a single activation barrier as in CNT, the PILP pathway involves multiple stages with lower individual energy barriers [4]. First, the polymer induces liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS), creating solute-rich droplets. Within these droplets, the mineral components can organize and densify before finally crystallizing. This multi-step pathway significantly reduces the kinetic barriers to nucleation, enabling crystallization under conditions where classical pathways would be impeded [1] [4].

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Classical and Non-Classical Nucleation Theories

| Aspect | Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) | PILP/Non-Classical Theory |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Mechanism | Ion-by-ion addition to forming nucleus | Liquid precursor phase via polymer induction |

| Energy Landscape | Single activation energy barrier | Multiple, lower energy barriers |

| Pathway | Direct solution-to-crystal transformation | Solution → liquid precursor → crystal |

| Role of Polymers | Typically inhibitory | Essential for inducing liquid phase separation |

| Structural Relationship | Nucleus identical to final crystal | Amorphous precursor transforms to crystal |

| Interfacial Energy | Constant, size-independent | Variable, depends on precursor structure |

The PILP Mechanism: A Multi-Stage Process

Molecular Foundations: The Role of Polymers and Intrinsically Disordered Proteins

The PILP process is fundamentally governed by specific molecular interactions between ionic polymers and mineral precursors. At the molecular level, charged polymers—such as polyaspartic acid (poly-Asp) or naturally occurring intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs)—function by sequestering calcium and phosphate ions to form stable polymer-mineral complexes [1]. These complexes concentrate mineral ions far beyond their normal solubility limits while preventing spontaneous crystallization through the polymers' ability to disrupt ion ordering [1] [2]. The charged residues along the polymer backbone create a dynamic, fluid environment that maintains the mineral components in a metastable state, effectively acting as a "crystallization chaperone" that can be directed to specific locations or templates [1].

Research has revealed that the proteins intimately associated with biominerals in nature are often IDPs, which lack a fixed tertiary structure but contain multiple charged domains that facilitate their interaction with mineral ions [1] [2]. This discovery has been pivotal in validating the biological relevance of the PILP process, as the early in vitro PILP studies utilized simple acidic polypeptides that serendipitously mimicked the behavior of these natural IDPs [1]. The flexible, dynamic nature of these polymers enables them to form coacervate droplets through liquid-liquid phase separation, creating a distinct fluid phase that serves as the mineralization environment [1] [4].

Stepwise Progression of the PILP Process

The PILP process unfolds through a well-defined sequence of stages that collectively enable the precise control over mineralization observed in biological systems:

Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation (LLPS): The process initiates when charged polymers (such as polyaspartic acid or biomimetic IDPs) interact with mineral ions in a supersaturated solution, inducing liquid-liquid phase separation and forming solute-rich, polymer-mineral coacervate droplets [1] [4]. These droplets, typically ranging from 100-500 nm in diameter, represent a distinct liquid phase with a high concentration of mineral precursors.

Precursor Migration and Infiltration: The liquid-like character of the PILP droplets enables them to flow into and conform to the geometry of confined spaces, such as the gap zones within collagen fibrils or other organic templates [3] [1]. This capillary action is driven by the fluid properties of the droplets and represents a crucial advantage over classical crystallization, where direct ion addition cannot achieve such complete penetration of nanostructured templates.

Densification and Solidification: Within the confined environment, the PILP droplets undergo progressive dehydration and densification, typically transforming first into amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP) in the case of phosphate systems [3] [1]. This amorphous intermediate is a hallmark of the PILP pathway and enables the formation of continuous mineral phases rather than discrete crystals.

Crystallization and Structural Maturation: The final stage involves the gradual transformation of the amorphous precursor into oriented crystalline material. In collagen mineralization, this results in hydroxyapatite crystals that are perfectly aligned with the collagen fibrils and occupy the intrafibrillar spaces—a characteristic feature of natural bone mineralization that classical pathways cannot replicate [3].

Diagram 1: PILP Process Stages

Experimental Methodologies: Inducing and Characterizing PILP Systems

Standard PILP Induction Protocol

The following detailed methodology describes a standardized approach for inducing the PILP process for calcium phosphate mineralization, particularly relevant for collagen mineralization studies as applied to bone and dentin regeneration research [3]:

Reagents and Solutions:

- Calcium stock solution: 4-20 mM calcium chloride (CaClâ‚‚) in buffered solution (e.g., HEPES or Tris-HCl, pH 7.4)

- Phosphate stock solution: 2-12 mM potassium phosphate (Kâ‚‚HPOâ‚„/KHâ‚‚POâ‚„) in same buffer

- Polymer additive: 50-200 μg/mL poly-L-aspartic acid or poly-L-glutamic acid (molecular weight 5-30 kDa)

- Mineralization template: Type I collagen fibrils (e.g., reconstituted collagen scaffolds, demineralized dentin, or natural bone matrix)

Procedure:

- Prepare the mineralization solution by slowly adding the calcium stock solution to the phosphate stock solution under gentle stirring to achieve a final Ca/P molar ratio between 1.67-2.0.

- Immediately add the polymer additive to the mixed mineralization solution and stir continuously for 10-15 minutes to ensure complete dissolution and complex formation.

- Adjust the pH to 7.2-7.6 using dilute NaOH or KOH, as the PILP process is highly sensitive to pH.

- Introduce the collagen template to the mineralization solution, ensuring complete immersion.

- Incubate the system at 37°C for periods ranging from 24 hours to several weeks, depending on the desired degree of mineralization.

- Monitor mineralization progress through periodic sampling and analysis (see characterization techniques below).

- Terminate the reaction by removing the template and rinsing thoroughly with deionized water to remove unincorporated ions and polymer.

Critical Parameters for Success:

- Polymer molecular weight and concentration: Optimal results typically require polymers in the 5-30 kDa range at concentrations sufficient to sequester ions without completely inhibiting crystallization.

- Ion concentration and ratio: Supersaturation levels must be carefully controlled—too low prevents nucleation, while too high leads to spontaneous precipitation.

- pH control: The process is highly pH-dependent, with neutral to slightly alkaline conditions generally preferred for calcium phosphate systems.

- Temperature: Physiological temperature (37°C) typically yields optimal results for biomimetic applications.

Advanced Characterization Techniques

Analyzing PILP systems requires multiple complementary characterization methods to confirm the presence of liquid precursors and track their transformation:

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM): Utilized to identify the liquid precursor droplets through direct imaging (often requiring cryo-TEM to preserve the liquid state) and to examine the final mineral structure, particularly intrafibrillar mineralization within collagen [3] [1].

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): Employed to assess the morphology and distribution of mineralized regions, with specialized techniques such as focused ion beam (FIB-SEM) providing cross-sectional views of mineral infiltration [3].

X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Used to determine the crystalline phase and preferred orientation of the final mineral, with time-resolved XRD capable of tracking the amorphous-to-crystalline transition [1].

Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR): Applied to identify chemical bonding environments, particularly the characteristic spectral features that distinguish amorphous precursors from crystalline phases [1].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for PILP Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in PILP Process |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium Sources | Calcium chloride (CaCl₂), Calcium nitrate (Ca(NO₃)₂) | Provides Ca²⺠ions for mineral formation |

| Phosphate Sources | Potassium phosphate (K₂HPO₄), Ammonium phosphate ((NH₄)₂HPO₄) | Provides PO₄³⻠ions for mineral formation |

| Polymeric Additives | Poly-L-aspartic acid, Poly-L-glutamic acid, Polyacrylic acid | Induces liquid phase separation, stabilizes precursors |

| Biomimetic Templates | Type I collagen fibrils, Demineralized dentin matrix, Synthetic scaffolds | Provides confined environments for precursor infiltration |

| Buffer Systems | HEPES, Tris-HCl, Carbonate-bicarbonate | Maintains physiological pH during mineralization |

| Mineralization Inhibitors | Osteopontin, Dentin matrix protein-1 (analogs) | Used in control experiments to demonstrate PILP specificity |

Applications and Implications: From Theory to Practice

Biomimetic Material Design and Tissue Regeneration

The PILP process has enabled significant advances in biomimetic material design, particularly for hard tissue regeneration. By mimicking the natural mineralization strategy, researchers have developed collagen-based composite materials that closely replicate the hierarchical structure and mechanical properties of natural bone [3]. These materials demonstrate the characteristic intrafibrillar mineralization where hydroxyapatite crystals form within the gap zones of collagen fibrils—a feature unattainable through conventional mineralization approaches [3]. This precise structural control translates to enhanced mechanical performance, with mineralized collagen scaffolds exhibiting optimized stiffness, strength, and toughness that support bone regeneration while gradually biodegrading as new tissue forms [3].

In dental applications, the PILP process has shown remarkable potential for dentin remineralization, offering a novel approach to treating dental caries. Unlike traditional restorative materials that merely fill cavities, PILP-based remineralization strategies can infiltrate the demineralized dentin matrix and restore its native structure and mechanical integrity [3]. This biomimetic approach regenerates the natural composite structure of dentin, potentially revolutionizing preventive and restorative dentistry by enabling true tissue regeneration rather than mere replacement [3].

Drug Delivery and Pharmaceutical Applications

Beyond structural biomaterials, the PILP process presents intriguing possibilities for drug delivery and pharmaceutical applications. The liquid precursor droplets can potentially encapsulate therapeutic agents—such as growth factors, antibiotics, or chemotherapeutic drugs—during their formation, enabling controlled release as the precursor transforms into crystalline mineral [6]. This mineralization-mediated drug delivery approach could provide precise temporal control over drug release kinetics, particularly for bone-targeted therapies where sustained local delivery is desirable [6].

The ability of PILP droplets to infiltrate porous structures and conform to complex geometries also offers advantages for creating drug-releasing mineral coatings on implant surfaces. Such coatings could enhance osseointegration while simultaneously preventing infection or inflammation through the localized delivery of bioactive molecules [6]. Additionally, the PILP process might be exploited for the controlled crystallization of poorly soluble pharmaceutical compounds, potentially improving their bioavailability through manipulation of crystal form and particle morphology [1].

Future Directions and Emerging Research Frontiers

Terminology Evolution: From PILP to CAT

As research progresses, some investigators have proposed refining the terminology used to describe the PILP process to better reflect current understanding of the underlying mechanisms. The term "Colloid Assembly and Transformation (CAT)" has been suggested as a more comprehensive descriptor that captures the essential stages of polymer-induced mineralization without overemphasizing the liquid character of the precursor [1] [2]. This proposed terminology shift acknowledges that the precursor phase often exhibits viscoelastic properties rather than purely liquid behavior, and more accurately encompasses the broader family of non-classical crystallization pathways that proceed through intermediate colloidal stages [1]. Regardless of nomenclature, the fundamental insights provided by the PILP/CAT model continue to drive innovation in biomineralization research and biomimetic material design.

Integration with Advanced Technologies

The convergence of PILP research with emerging technologies represents a particularly promising frontier. The integration of artificial intelligence and computational modeling approaches is enabling more precise prediction and control over mineralization outcomes, potentially allowing researchers to design custom polymers optimized for specific mineralization applications [6]. Similarly, advances in superhydrophilic/hydrophobic interfacial engineering are creating new opportunities to spatially direct mineralization processes with unprecedented precision [6]. These technological synergies will likely accelerate the translation of PILP-based strategies from laboratory demonstrations to clinically viable solutions for tissue regeneration, drug delivery, and biomedical device enhancement.

Diagram 2: Research Applications & Frontiers

The discovery and development of the polymer-induced liquid precursor process has fundamentally transformed our understanding of crystallization phenomena in biological systems. By challenging the long-dominant classical nucleation theory, the PILP concept has provided a powerful explanatory framework for the exquisite control over mineral formation observed in nature while simultaneously opening new pathways for biomimetic material design. The ability to direct mineralization through liquid precursors rather than conventional ion-by-ion addition enables unprecedented control over material structure and properties at multiple length scales. As research continues to refine our understanding of the underlying mechanisms and expand the range of applications, PILP-based strategies hold exceptional promise for advancing tissue engineering, drug delivery, regenerative medicine, and numerous other fields where precise control over crystallization processes is essential.

The Polymer-Induced Liquid Precursor (PILP) process has revolutionized our understanding of biomineralization, representing a significant paradigm shift from classical crystallization pathways. Initially conceptualized as a liquid-phase precursor, the PILP system has emerged as a complex viscoelastic medium formed through polymer-directed assembly of nanoscale mineral clusters. This transformation in understanding bridges critical gaps between in vitro models and the intricate processes governing biological mineral formation in systems ranging from marine exoskeletons to human bone and dentin. This technical review comprehensively examines the evolution of PILP characterization, from its initial discovery through contemporary nanoscale analysis, providing researchers with detailed methodological frameworks and quantitative insights into this remarkable non-classical mineralization pathway.

The field of biomineralization has undergone a fundamental transformation over the past quarter-century, largely paralleling the discovery and ongoing investigation of the Polymer-Induced Liquid Precursor (PILP) process. First introduced by Gower approximately 25 years ago, the PILP system initially provided an in vitro model for investigating how charged biopolymers modulate mineral formation [7]. This discovery emerged at a pivotal time when researchers struggled to explain the complex hierarchical structures and non-equilibrium morphologies observed in biominerals that defied explanation by classical crystallization theories.

The PILP process describes a mechanism where charged polymers stabilize amorphous mineral precursors, enabling liquid-like or viscoelastic behavior that facilitates the creation of complex biomineral architectures [8]. This pathway has proven highly relevant to biomineralization because biological minerals frequently incorporate charged biopolymers directly associated with the mineral phase [8]. The initial conceptualization of PILP as a true liquid precursor has evolved significantly, with recent research revealing a more complex viscoelastic nature with nanogranular characteristics [7] [9] [10]. This evolution in understanding reflects advances in characterization technologies and a growing recognition that the process might be more accurately described as Colloid Assembly and Transformation (CAT) [7].

This technical guide examines the evolving understanding of the PILP process, with particular emphasis on its structural transformation from liquid-like droplets to viscoelastic phases, its role in biomineralization, and its growing applications in biomimetic materials and regenerative medicine. The content is framed within the broader context of biomineralization research, providing scientists with comprehensive methodological frameworks and technical data to advance investigations in this rapidly evolving field.

Historical Development and Conceptual Evolution

Initial Discovery and Fundamental Principles

The PILP process was first identified in calcium carbonate systems using simple polypeptide additives such as polyaspartic acid (pAsp) and polyacrylic acid (pAA) [7]. Early observations revealed that these charged polymers could stabilize an amorphous calcium carbonate precursor that behaved as a liquid phase, enabling the formation of non-equilibrium crystal morphologies impossible to achieve through classical ion-by-ion crystallization [8]. The hallmark of this process was the appearance of micrometer-sized droplets (1-5 μm) that could coalesce, wet surfaces, and be molded into complex shapes before transforming into crystalline materials [10].

Gower's initial hypothesis proposed that these liquid-like droplets could infiltrate constrained environments like collagen fibrils or porous membranes, subsequently solidifying and crystallizing while maintaining the shape of their confinement [8]. This mechanism provided an elegant explanation for how biological systems could create intricate mineralized tissues with precise morphological control without requiring epitaxial templates or cellular molding of each individual crystalline element.

The Shift from Liquid to Viscoelastic Understanding

As characterization techniques advanced, particularly with the application of cryogenic transmission electron microscopy (cryoTEM) and advanced NMR spectroscopy, the simple liquid droplet model required refinement. Research published in Nature Communications in 2018 demonstrated that what appeared to be liquid droplets actually consisted of 30-50 nm amorphous calcium carbonate (ACC) nanoparticles with ~2 nm nanoparticulate texture [10]. These nanoparticles assembled into larger structures while maintaining their discrete characteristics, rather than coalescing into continuous liquid phases.

Table 1: Evolution of PILP Conceptual Models

| Time Period | Primary Model | Key Evidence | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000-2010 | Liquid Droplet Model | Optical microscopy of moving droplets; Formation of continuous films | Could not explain nanogranular textures |

| 2010-2018 | Viscoelastic Phase | Rheological measurements; AFM mechanical testing | Inconsistent liquidity observations |

| 2018-Present | Nanogranular Assembly | cryoTEM of nanoparticle assemblies; NMR diffusion studies | Reconciled macroscopic behavior with nanostructure |

Concurrent mechanical investigations revealed that the PILP phase exhibited complex viscoelastic properties rather than simple liquid behavior. Time-dependent modulus measurements demonstrated that PILP droplets initially displayed liquid-like characteristics but rapidly developed gel-like elasticity with moduli increasing from less than 0.2 MPa to several MPa [9]. This viscoelastic character explained the PILP phase's ability to both flow into confined spaces and maintain structural integrity before crystallization.

Contemporary Framework: Colloid Assembly and Transformation (CAT)

The evolving understanding has led to proposals for terminology refinement, with "Colloid Assembly and Transformation" (CAT) suggested as a more accurate description of the process [7]. This terminology better captures the key stages of polymer-driven assembly of amorphous nanoclusters and their subsequent transformation to crystalline phases, while acknowledging the viscoelastic rather than purely liquid character of the precursor phase.

The CAT framework emphasizes that the liquid-like behavior observed at macroscopic scales results from the small size and surface properties of nanogranular assemblies rather than true liquid phase separation [7] [10]. This perspective has helped reconcile seemingly contradictory observations of both fluidic behavior and solid-like characteristics in PILP systems.

Structural and Mechanical Characteristics of the PILP Phase

Nanoscale Architecture and Composition

Advanced characterization techniques have revealed the intricate architecture of the PILP phase. CryoTEM studies demonstrate that the initial PILP products are 30-50 nm amorphous calcium carbonate nanoparticles composed of even smaller ~2 nm subunits [10]. These nanoparticles aggregate into larger structures while maintaining their discrete boundaries, rather than coalescing into homogeneous liquids as previously hypothesized.

The polymer component, typically polyanions such as pAsp or pAA, plays a crucial role in stabilizing this nanogranular architecture. These polymers become excluded during crystallization, leading to the formation of organic-inorganic composite structures with organic material concentrated at grain boundaries [7]. This exclusion process creates the characteristic nanogranular texture observed in both PILP-generated materials and biominerals, with organics sequestered at interface regions contributing to enhanced mechanical properties through "fuzzy" interfaces [7].

Table 2: Structural Characteristics of PILP Phase at Different Scales

| Scale | Structural Features | Characterization Methods | Biological Correlates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular | ~2 nm ACC clusters | NMR, cryoTEM | Pre-nucleation clusters |

| Nanoscale | 30-50 nm ACC nanoparticles | cryoTEM, SAED | Biomineral nanogranules |

| Mesoscale | Nanoparticle assemblies (100 nm-μm) | SEM, AFM, DIC microscopy | Mineralized fibrils |

| Macroscopic | Space-filling continuous phases | Optical microscopy, mechanical testing | Bone, dentin, nacre |

Mechanical and Viscoelastic Properties

The mechanical behavior of the PILP phase represents one of its most distinctive characteristics. Recent in situ atomic force microscopy (AFM) measurements have quantified the time-dependent mechanical evolution of PILP droplets. Initial properties range from liquid-like behavior with high interfacial tension (350 mJ mâ»Â²) to soft gel-like materials with moduli less than 0.2 MPa [9]. These initial properties enable the liquid-like behavior essential for infiltration and molding applications.

Over time, the modulus of the PILP phase increases significantly, evolving from less than 0.2 MPa to several MPa as the phase densifies and eventually transforms into solid amorphous phases before crystallization [9]. This viscoelastic progression explains how the PILP phase can initially infiltrate collagen fibrils or other constrained environments, then gradually solidify to form interpenetrating organic-inorganic composites with excellent mechanical properties.

The following diagram illustrates the structural evolution of the PILP phase from initial ion-polymer complexes to final crystalline composites:

Methodological Framework: Experimental Approaches and Protocols

Standard PILP Formation Protocol for Calcium Carbonate

The foundational protocol for generating PILP phases in calcium carbonate systems remains based on Gower's original methodology with subsequent refinements. The following procedure outlines the standard approach for producing PILP phases for biomimetic mineralization studies:

Reagents and Solutions:

- Calcium chloride solution (10-20 mM CaClâ‚‚ in deionized water)

- Sodium carbonate solution (10-20 mM Na₂CO₃ in deionized water)

- Polyaspartic acid (pAsp, MW 2,000-11,000 Da) or polyacrylic acid (pAA) stock solution (1 mg/mL in deionized water)

- Inert background electrolyte (e.g., NaCl) to maintain constant ionic strength

Procedure:

- Prepare crystallization solutions by mixing equal volumes of calcium chloride and sodium carbonate solutions in a clean container

- Immediately add polymer stock solution to achieve final concentrations of 1-10 μg/mL

- Maintain solution at controlled temperature (20-25°C) under gentle agitation

- Monitor pH throughout reaction (typically initial pH ~10.5-11.0)

- Within 150-250 minutes, PILP phase formation can be observed as micron-sized droplets via optical microscopy [10]

- For film formation, place hydrophilic substrates (glass, mica) vertically in the solution

- For infiltration experiments, place porous substrates (polycarbonate membranes with 50-200 nm pores) in the solution

- Allow crystallization to proceed for desired duration (typically 24-72 hours)

Critical Parameters:

- Polymer molecular weight and concentration significantly impact PILP formation

- Calcium:carbonate ratio should be approximately 1:1

- Solution supersaturation must be carefully controlled

- Presence of magnesium ions (10-30 mM) can enhance stability of amorphous phases

Dentin Remineralization Protocol Using PILP Methodology

The PILP process has shown significant promise in functional remineralization of dentin caries lesions. The following protocol outlines the procedure for applying PILP methodology to dentin remineralization as validated by nanoindentation and microcomputed tomography [11] [12]:

Reagents and Solutions:

- Conditioner solution: 5 mg/mL pAsp in simulated body fluid (SBF)

- PILP cement: pAsp mixed with bioglass 45S5 (commercial bioglass powder)

- Simulated body fluid (SBF) prepared according to Kokubo formulation

- Artificial dentin lesions prepared from human third molars

Procedure:

- Prepare artificial dentin lesions (3-4 mm thick blocks) with demineralized zones of ~140 μm (shallow) or ~700 μm (deep) depth

- Apply 20 μL of conditioner solution (5 mg/mL pAsp) to demineralized lesion specimens for 20 seconds

- For experimental groups, apply PILP cement to wet surface of demineralized specimen

- Restore with glass ionomer cement (RMGIC) as control or experimental PILP-releasing restorative

- Immerse specimens in SBF solution at 37°C for 2 weeks (shallow lesions) or 4 weeks (deep lesions)

- Assess remineralization via nanoindentation for elastic modulus and hardness recovery

- For natural lesions, monitor mineral density changes via microcomputed tomography at 0, 1, and 3 months

Evaluation Methods:

- Nanoindentation: Measure elastic modulus and hardness across lesion depth

- Microcomputed tomography: Quantify mineral density and volume changes

- SEM/EDS: Examine surface morphology and elemental composition

- XRPD: Identify mineral phases present after remineralization

Advanced Characterization Techniques for PILP Phase Analysis

Modern PILP research employs sophisticated characterization methods to elucidate the complex nature of the precursor phase:

Cryogenic Transmission Electron Microscopy (cryoTEM):

- Vitrify samples at precise time points using liquid ethane plunge freezing

- Image under cryogenic conditions to preserve native hydrated state

- Acquire high-resolution images and selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns

- Perform 3D reconstruction via electron tomography for nanoscale architecture [10]

In Situ Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM):

- Measure mechanical properties of individual PILP droplets

- Quantify time evolution of elastic moduli

- Characterize surface adhesion and deformation behavior [9]

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy:

- Utilize liquid-state NMR to detect mobile components

- Employ solid-state NMR for structural characterization of amorphous phases

- Measure diffusion coefficients to assess liquidity [10]

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated experimental approach for PILP characterization:

Quantitative Analysis of PILP Systems

Mechanical Property Evolution

Recent investigations have provided quantitative data on the mechanical evolution of the PILP phase. In situ AFM measurements of calcium carbonate PILP droplets have documented a progressive increase in mechanical properties over time:

Table 3: Time Evolution of PILP Mechanical Properties

| Time Phase | Elastic Modulus | Interfacial Tension | Physical State | Functional Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial (0-10 min) | <0.2 MPa | 350 mJ mâ»Â² | Liquid to soft gel | Enables infiltration into confined spaces |

| Intermediate (10-60 min) | 0.2-1 MPa | N/A | Viscoelastic gel | Partial coalescence, molding capability |

| Late (>60 min) | 1->5 MPa | N/A | Solid amorphous phase | Maintains shape before crystallization |

| Crystalline Final | >10 GPa | N/A | Crystalline composite | Functional biomimetic material |

This mechanical evolution explains how the PILP phase can initially display liquid-like characteristics sufficient for infiltration into collagen fibrils or porous templates, yet progressively develop solid-like properties that maintain the molded morphology during the amorphous-to-crystalline transformation [9].

Performance Metrics in Remineralization Applications

Quantitative assessment of PILP-based dentin remineralization demonstrates the functional efficacy of this approach. Nanoindentation measurements across lesion depth show significant recovery of mechanical properties after PILP treatment:

Table 4: Dentin Remineralization Efficacy via PILP Process

| Treatment Method | Elastic Modulus Recovery | Hardness Recovery | Mineral Density Increase | Treatment Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PILP Conditioner + RMGIC | 70-80% in shallow lesions | Significant improvement (p<0.05) | N/A | 2 weeks (shallow) 4 weeks (deep) |

| PILP Cement + RMGIC | Significant improvement (p<0.05) in middle zones | Significant improvement (p<0.05) | N/A | 2 weeks (shallow) 4 weeks (deep) |

| PILP Solution (no restoration) | Significant improvement (p<0.01) | Significant improvement (p<0.01) | N/A | 4 weeks |

| Natural Lesions (PILP treatment) | N/A | N/A | Significant increase (p<0.05) | 3 months |

These quantitative results demonstrate that PILP-based treatments can functionally remineralize dentin lesions by restoring mechanical properties rather than merely increasing mineral content [11] [12]. The recovery is most significant when specimens are treated with PILP-solution containing restorative materials, highlighting the importance of combining the PILP process with appropriate delivery systems.

Research Reagent Solutions for PILP Investigations

The following table details essential research reagents and materials critical for experimental PILP research, with specifications and functional roles:

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for PILP Investigations

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Functional Role | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyaspartic Acid (pAsp) | MW: 2,000-11,000 Da; Concentration: 1-10 μg/mL for standard systems | Anionic polymer for stabilizing ACC precursors; Generates PILP phase | Calcium carbonate PILP; Dentin remineralization [11] [10] |

| Polyacrylic Acid (pAA) | MW: 2,000-10,000 Da; Various concentrations | Alternative anionic polymer for PILP formation | Calcium carbonate morphology control |

| Bioglass 45S5 | Commercial bioglass powder; Specific composition | Ion source for apatite formation in bioactive materials | PILP cement for dentin remineralization [11] |

| Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) | Kokubo formulation; pH 7.4 | Biomimetic mineralization environment | In vitro bioactivity testing; Remineralization studies [13] [11] |

| Track-Etch Polycarbonate Membranes | Pore sizes: 50 nm, 100 nm, 200 nm | Nanoconfinement templates for PILP infiltration | Producing nanorods with non-equilibrium morphologies [10] |

| Calcium Silicates | Tricalcium silicate (Ca₃SiO₅); Dicalcium silicate (Ca₂SiO₄) | Main components of bioceramic materials | Experimental endodontic sealers [13] |

Applications and Future Directions

Current Research Applications

The PILP process has enabled significant advances in multiple research domains:

Biomimetic Materials Synthesis: The PILP process facilitates creation of composite materials with complex architectures mimicking natural biominerals. This includes synthetic nacre-like structures, bone-like composites, and enamel-mimetic coatings [8]. The ability to generate non-equilibrium crystal morphologies through infiltration and molding provides a powerful fabrication strategy for advanced organic-inorganic hybrid materials.

Dental Restorative Applications: PILP-based methodologies show exceptional promise in functional remineralization of dentin caries lesions. Research demonstrates that PILP treatments can restore mechanical properties to demineralized dentin by promoting intrafibrillar mineralization within collagen matrices [11] [12]. This approach addresses a critical limitation of conventional remineralization strategies that often only achieve surface mineralization without recovering biomechanical function.

Regenerative Medicine: The creation of stronger soft materials without inducing rigidity represents an emerging application of PILP technology. Research presented at BMES 2025 highlighted how the PILP process can enhance collagen's elasticity and resilience, resulting in soft, elastic materials with improved mechanical properties for tissue engineering applications [14].

Technical Challenges and Research Frontiers

Despite significant advances, several challenges remain in fully harnessing the PILP process:

Process Control and Standardization: Reproducible PILP formation requires careful control of multiple parameters including polymer characteristics, ion concentrations, pH, and temperature. Developing standardized protocols for specific applications remains an ongoing challenge.

Characterization Limitations: The transient nature of PILP phases and their sensitivity to experimental conditions complicate characterization. Development of more advanced in situ characterization methods is essential for further elucidating the formation and transformation mechanisms.

Clinical Translation: For biomedical applications such as dentin remineralization, translating the PILP process from laboratory demonstrations to clinically viable treatments requires addressing challenges related to delivery systems, treatment duration, and regulatory considerations [11] [12].

Future research directions include expanding the PILP concept to additional material systems beyond calcium carbonate and calcium phosphate, developing four-dimensional characterization approaches to track PILP evolution in real time, and creating commercial products leveraging the unique capabilities of this remarkable biomineralization pathway.

The understanding of polymer-induced liquid precursors has evolved substantially from initial conceptualization as simple liquid droplets to the current model of viscoelastic nanogranular assemblies. This evolution reflects advances in characterization technologies and a growing appreciation of the complex interplay between polymers and mineral precursors in both biological and synthetic systems. The PILP process continues to provide profound insights into biomineralization mechanisms while enabling innovative approaches to materials synthesis and biomedical applications. As research advances, the integration of PILP methodologies into clinical practice and industrial materials processing promises to yield transformative technologies inspired by nature's sophisticated mineralization strategies.

Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs) as Natural PILP Analogues in Biological Systems

The polymer-induced liquid precursor (PILP) process, an in vitro biomimetic mineralization system, has emerged as a powerful model for understanding the formation of complex biomineral architectures. Recent evidence suggests that intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs), which lack stable tertiary structures and exist as dynamic conformational ensembles, may function as natural analogues to the synthetic polymers used in PILP systems. This review examines the mechanistic parallels between IDP-mediated biomineralization and the PILP process, highlighting how the structural flexibility, molecular recognition capabilities, and phase-separation properties of IDPs enable precise control over mineral formation. We synthesize findings from structural biology, materials characterization, and computational studies to establish a framework for understanding IDPs as biological PILP agents, with implications for developing novel biomaterials and therapeutic strategies.

The polymer-induced liquid precursor (PILP) process was first discovered by Gower approximately 25 years ago as a distinctly non-classical crystallization pathway [7]. In this process, charged polymeric additives such as poly(aspartic acid) sequester ions to form a highly hydrated, liquid-like amorphous precursor phase that can mold into non-equilibrium morphologies before crystallizing [7] [15]. This system has proven remarkably capable of emulating enigmatic features found in biominerals, including non-equilibrium morphologies, interpenetrating nanostructured composites, and specific defect textures [7].

The biological relevance of PILP became increasingly apparent as researchers recognized that the charged proteins intimately associated with biominerals are often intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) [7]. IDPs lack defined three-dimensional structures yet retain crucial biological functions, existing as dynamic conformational ensembles that can respond to environmental stimuli [16] [17]. Their structural plasticity and multifunctionality make them ideal regulators of biomineralization processes, paralleling the role of synthetic polymers in PILP systems.

This review explores the hypothesis that IDPs function as natural PILP analogues in biological systems, examining the structural, mechanistic, and functional evidence supporting this connection. By framing IDP-mediated biomineralization through the lens of the PILP process, we aim to establish a unified conceptual framework for understanding how organisms achieve precise control over mineral formation.

Structural and Functional Parallels Between IDPs and PILP Polymers

Molecular Characteristics of IDPs and PILP Polymers

IDPs and the synthetic polymers used in PILP systems share fundamental characteristics that enable their function in directing non-classical mineralization pathways:

- Structural Dynamics: IDPs exist as dynamic structural ensembles with conformational heterogeneity, allowing them to adapt to binding partners and environmental conditions [16] [18]. Similarly, polymers in PILP systems exhibit structural flexibility that facilitates interaction with mineral precursors.

- Charge Distribution: Both IDPs and PILP polymers typically contain clustered charge motifs that enable strong electrostatic interactions with ionic species in mineralizing solutions. These charged regions are often rich in acidic residues like aspartic and glutamic acid, analogous to the poly(aspartic acid) used in PILP systems [7] [19].

- Hydration Properties: IDPs frequently have extended hydrated regions that maintain solubility and prevent premature aggregation [16]. Similarly, the PILP process depends on the formation of a highly hydrated amorphous precursor that maintains fluidity before crystallization [15].

Functional Mechanisms in Mineralization

The functional parallels between IDPs and PILP polymers manifest through several key mechanisms:

- Amorphous Phase Stabilization: Both IDPs and PILP polymers stabilize amorphous precursor phases, with biogenic amorphous calcium carbonate (ACC) often containing proteins rich in aspartic acid residues [15], mirroring the poly(aspartic acid) used in PILP systems.

- Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation: Recent evidence suggests that many IDPs can undergo liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS), leading to the formation of membrane-less organelles [18]. This process bears striking similarity to the liquid-phase separation observed in PILP systems, suggesting a common mechanism for organizing mineral precursors.

- Exclusion During Crystallization: In both PILP and biological systems, polymeric additives become excluded during the amorphous-to-crystalline transformation, leading to the occlusion of organics at grain boundaries or the formation of mesocrystals [7]. This exclusion process generates the nanogranular textures common to both synthetic PILP-derived materials and biominerals.

Table 1: Comparative Properties of IDPs and PILP Polymers in Mineralization

| Property | IDPs in Biomineralization | PILP Polymers |

|---|---|---|

| Structural State | Dynamically disordered ensembles [16] | Flexible polymer chains |

| Charge Characteristics | Clustered acidic residues (Asp, Glu) [19] | High density of carboxylate groups [7] |

| Phase Behavior | Liquid-liquid phase separation capability [18] | Liquid-phase separation observed [7] |

| Precursor Interaction | Stabilization of amorphous phases [15] | Induction of amorphous precursors [10] |

| Fate During Crystallization | Exclusion to grain boundaries [7] | Exclusion during transformation [7] |

| Resulting Texture | Nanogranular biominerals [7] | Nanogranular synthetic minerals [10] |

Experimental Evidence: IDPs as Natural PILP Analogues

Nanostructural Characterization of PILP and Biominerals

Advanced characterization techniques have revealed striking similarities between PILP-derived materials and biominerals at the nanoscale:

Cryogenic transmission electron microscopy (cryoTEM) studies of the CaCO₃ PILP process have shown that the initial products are 30-50 nm amorphous calcium carbonate (ACC) nanoparticles with approximately 2 nm nanoparticulate texture [10]. These nanoparticles aggregate to form larger structures without coalescing into continuous liquid droplets, suggesting that the "liquid-like" behavior of PILP at macroscopic scales results from the small size and surface properties of these assemblies [10]. This nanogranular texture closely matches that observed in biominerals such as mollusk nacre and sea urchin spines, which also exhibit remnant colloidal textures of similar dimensions [7] [10].

The transformation process further reinforces the connection between PILP and biological mineralization. In both cases, the amorphous precursor undergoes solidification and crystallization with exclusion of the polymeric constituents, leading to similar defect structures and "transition bars" that match the etching patterns seen in nacre [7]. These shared mineralogical signatures point to common crystallization mechanisms despite the different origins of the polymeric modifiers.

IDP Interactions with Mineral Precursors

Biophysical studies have elucidated how IDPs interact with mineral precursors in ways that parallel the PILP process:

IDPs can form "fuzzy complexes" with mineral surfaces and precursors, where residual disorder is retained even in the bound state [16]. This interfacial behavior mirrors observations from the PILP process, where polymers appear to coat and stabilize the nanogranular clusters of ACC [7]. The inherent structural heterogeneity of IDPs allows them to engage in multivalent interactions with evolving mineral phases, simultaneously inhibiting classical crystallization while promoting alternative assembly pathways.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy has provided molecular-level insights into these interactions. Studies of PILP systems have shown strong binding between polymers and ACC in early stages, with subsequent exclusion during crystallization [10]. Similarly, NMR studies of IDPs have revealed how their dynamic structural ensembles enable complex interaction patterns with mineral phases, integrating multiple stimuli through cooperative effects on their conformational distributions [16].

Table 2: Experimental Techniques for Characterizing IDP-PILP Analogies

| Technique | Applications | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| CryoTEM | Visualization of hydrated precursor structures [10] | PILP consists of 30-50 nm ACC nanoparticles with ~2 nm substructure; similar to biogenic ACC |

| Solid-State NMR | Molecular-level structure of amorphous precursors [10] | Strong polymer-ACC interactions in early stages; exclusion during crystallization |

| SEM/TEM of Etched Samples | Analysis of mineralogical signatures [7] | Similar transition bars and defect textures in PILP-derived crystals and biominerals |

| Single-Molecule FRET | Conformational dynamics of IDPs [16] | Structural plasticity of IDPs enables adaptation to mineral interfaces |

| Small-Angle X-ray Scattering | Structural analysis of IDP ensembles [16] | Characterization of heterogeneous conformations in mineral-associated IDPs |

Methodological Approaches for Studying IDP-PILP Systems

Experimental Protocols for PILP Mineralization

The standard methodology for investigating PILP-based mineralization involves controlled crystallization experiments with polymeric additives:

Materials Preparation:

- Calcium source: 20 mM CaCl₂·2H₂O in double deionized water [15]

- Carbonate source: (NH₄)₂CO₃ powder placed in a separate container for vapor diffusion [15]

- Polymeric additive: Poly(aspartic acid) sodium salt (MW 2,000-11,000 g/mol) typically at concentrations of 50-200 μg/mL [7] [10]

- Substrates: Glass slides, track-etch membranes, or collagen scaffolds for mineralization [10] [20]

Procedure:

- Prepare calcium chloride solution with polymeric additive in a sealed container

- Place ammonium carbonate powder in a separate beaker within the container

- Allow CO₂ and NH₃ vapors to diffuse into the solution gradually raising supersaturation

- Monitor solution turbidity as an indicator of phase separation

- Collect samples at various time points for characterization

- For collagen mineralization, immerse scaffolds in the reaction solution [20]

Key Parameters:

- Polymer molecular weight significantly affects mineralization outcomes [20]

- Solution pH and ionic strength influence phase separation behavior

- Temperature controls reaction kinetics and precursor stability

Characterization Techniques for IDP-Mineral Interactions

Understanding IDP function in biomineralization requires specialized characterization approaches:

Structural Analysis of IDPs:

- Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy: Detects global disorder and residual secondary structure [18]

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance: Provides residue-specific information on dynamics and interactions [16]

- Single-Molecule Fluorescence: Monitors conformational distributions and binding events [16]

- Small-Angle X-ray Scattering: Characterizes ensemble dimensions and compactness [16]

Mineral Phase Characterization:

- CryoTEM: Visualizes hydrated precursors without drying artifacts [10]

- Selected Area Electron Diffraction: Identifies amorphous and crystalline phases [10]

- Raman/Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy: Determines mineral composition and hydration state [15]

- Thermogravimetric Analysis: Quantifies organic-inorganic ratios [20]

The Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for IDP-PILP Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(aspartic acid) | Synthetic analogue of acidic IDPs; induces PILP process [7] | CaCO₃ PILP formation; collagen mineralization [20] |

| Double-stranded DNA | Charged polymer for PILP; visualization by cryoTEM [10] | Study of polymer-mineral interactions [10] |

| Type I Collagen Sponges | Biological scaffold for mineralization studies [20] | Bone-like composite formation [20] |

| Ammonium Carbonate | Carbonate source via vapor diffusion [15] | Controlled supersaturation in PILP experiments [15] |

| CryoTEM Grids | Vitrification of hydrated samples [10] | Nanostructural analysis of precursors [10] |

| Isotopically Labeled Compounds | NMR studies of molecular interactions [10] | Tracking polymer-mineral interactions [10] |

| 2-Iodohexadecan-1-ol | 2-Iodohexadecan-1-ol, 93%|CAS 153657-85-3 | 2-Iodohexadecan-1-ol is a high-purity (93%) iodinated alcohol for research. Explore its applications in organic synthesis. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Fluroxypyr-butometyl | Fluroxypyr-butometyl|CAS 154486-27-8|Herbicide Research | Fluroxypyr-butometyl is a pyridyloxycarboxylic acid herbicide for professional research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO) and is not intended for personal or agricultural use. |

Implications and Future Directions

CAT Pathway: A Unified Framework for Biomineralization

The striking parallels between IDP-mediated biomineralization and the PILP process have led to proposals for new terminology that more accurately captures the underlying mechanisms. The Colloid Assembly and Transformation (CAT) pathway has been suggested as a more comprehensive description of these non-classical crystallization processes [7]. This terminology emphasizes the key stages of colloidal assembly of amorphous nanoparticles followed by their transformation into crystalline structures, while acknowledging the viscoelastic rather than purely liquid character of the precursor phase.

The CAT framework resolves semantic confusions that have arisen from the discovery of multiple "non-classical crystallization" pathways and provides a unified conceptual model for understanding both biological and synthetic systems [7]. Within this framework, IDPs function as natural colloidal stabilizers and assembly directors that regulate the size, stability, and transformation of mineral precursors.

Therapeutic Applications and Biomaterial Design

The understanding of IDPs as natural PILP analogues opens promising avenues for therapeutic development and biomaterial design:

Pathological Mineralization:

- IDP-PILP mechanisms may underlie pathological calcification in conditions such as kidney stones and cardiovascular calcification [7] [8]

- The layered structures observed in Randall's plaques and kidney stones resemble those generated via PILP processes [7]

- Targeting specific IDPs or their interactions with mineral precursors could yield novel therapeutic strategies

Biomaterial Development:

- PILP-inspired bone graft substitutes with bone-like mineral content and nanostructure [8] [20]

- IDP-mimetic polymers for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine

- Controlled drug delivery systems based on mineral-IDP composites

The convergence of research on IDPs and the PILP process has revealed profound similarities in how biological organisms and synthetic systems control mineral formation. IDPs function as natural analogues to the polymeric additives used in PILP systems, employing similar mechanisms of amorphous precursor stabilization, liquid-like phase behavior, and controlled crystallization through exclusion processes. The CAT pathway provides a unified conceptual framework for understanding these phenomena, emphasizing the colloid assembly and transformation steps common to both systems.

This integrated perspective advances our fundamental understanding of biomineralization while opening new possibilities for biomaterial design and therapeutic development. By harnessing the principles of IDP-PILP systems, researchers can develop increasingly sophisticated materials that mimic the remarkable properties of biological composites, from bone-like scaffolds to functional hierarchical structures. As characterization techniques continue to improve, particularly in studying dynamic disordered systems and hydrated precursors, our understanding of these complex processes will continue to deepen, offering new insights into one of nature's most fascinating material fabrication strategies.

The field of biomineralization has undergone a profound revolution over the past 25 years, largely paralleling the discovery by Gower of the polymer-induced liquid-precursor (PILP) mineralization process [2] [7]. This in vitro model system was proposed as a means to study the role of biopolymers in biomineralization; however, the full ramifications of this pivotal discovery were slow to be recognized [7]. The original PILP terminology, while groundbreaking, has increasingly shown limitations in accurately describing the observed phenomena. The term "liquid precursor" has become particularly problematic as advanced characterization techniques have revealed that the precursor phase possesses complex viscoelastic character rather than being a simple liquid [2] [7] [10]. This review proposes and justifies the more comprehensive terminology of "Colloid Assembly and Transformation (CAT)" to describe the polymer-modulated reactions in both biomineralization and the PILP process.

The semantic challenges in this field are further compounded by the discovery of multiple "non-classical crystallization" pathways, leading to confusing terminology where terms like "particle attachment" and "oriented attachment" are often used interchangeably, despite representing fundamentally different processes [7]. The CAT terminology aims to resolve these inconsistencies by more accurately capturing the key stages involved in both biomineralization and the PILP process, emphasizing the colloidal nature of the precursor and its subsequent assembly and transformation into mature biominerals [2] [7].

Theoretical Foundation: From PILP to CAT

Historical Context and Limitations of PILP Terminology

The polymer-induced liquid-precursor (PILP) process was discovered approximately 25 years ago as a distinctly different pathway from classical crystallization processes [7]. The Gower research group demonstrated that this model system could emulate numerous enigmatic features of biominerals that pervaded the 1990s literature, starting with non-equilibrium morphologies - the hallmark of invertebrate biominerals - to interpenetrating nanostructured composites [7]. Perhaps even more revealing are the similar defect textures between PILP-synthesized materials and biominerals, as 'mineralogical signatures' point to crystallization mechanisms that follow a non-classical pathway [7].

Despite this compelling evidence, the biomineralization community still rarely refers to biomineralization as occurring through a PILP-like process [7]. This reluctance stems primarily from the namesake itself, which includes the word "liquid," while it has become clear in recent years that the amorphous precursor phase of biominerals is not a pure liquid phase, given that biominerals ubiquitously have a remnant colloidal or nanogranular texture [7]. Conversely, the biomineral precursors are presumably not solid particles either, given their complete space-filling properties [7]. This paradox highlights the need for terminology that better captures the intermediate nature of the precursor phase.

The CAT Conceptual Framework

The Colloid Assembly and Transformation (CAT) terminology addresses the limitations of the PILP model by more accurately describing the physical state and transformation pathway of the precursor phase. The "colloid" component acknowledges the nanogranular composition of the precursor, which consists of amorphous nanoparticles approximately 30-50 nm in diameter with ~2 nm nanoparticulate texture [10]. The "assembly" aspect captures the process whereby these colloidal particles organize into larger structures, while "transformation" describes the subsequent crystallization process that occurs with exclusion of polymeric impurities [7].

This conceptual framework resolves the apparent contradiction between the liquid-like behavior observed macroscopically and the solid-like characteristics observed at the nanoscale. The CAT pathway suggests that the liquid-like behavior at the macroscopic level is due to the small size and surface properties of the nanogranular assemblies, rather than the bulk properties of a true liquid phase [10]. This explains observations that the precursor phase exhibits viscoelastic character and can display either complete wetting (contact angle = 0°) or non-wetting (contact angle >150°) behavior on different substrates - phenomena that cannot be explained by conventional liquid droplet models [10].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Terminology in Non-Classical Crystallization

| Term | Key Features | Limitations | Proposed Improvement in CAT |

|---|---|---|---|

| PILP (Polymer-Induced Liquid Precursor) | Liquid-like droplet behavior; Space-filling capability; Forms non-equilibrium morphologies [7] | Misleading "liquid" descriptor; Doesn't account for nanogranular texture; Oversimplifies viscoelastic character [7] [10] | Acknowledges colloidal nature; Explains macroscopic liquid-like behavior through nanoscale properties |

| Particle Attachment | Emphasis on solid particles assembling; Includes oriented attachment [7] | Implies solid phase only; Doesn't explain space-filling and densification [7] | Incorporates viscoelastic consistency that enables flow and coalescence over time |

| Pre-Nucleation Clusters (PNCs) | Focus on very early stages; Sub-critical species [21] | Debate over structure and role; Doesn't address later assembly stages [7] | CAT encompasses the entire pathway from early clusters to final crystalline material |

Experimental Evidence Supporting the CAT Model

Nanostructural Characterization of the Precursor Phase

Advanced characterization techniques, particularly cryogenic Transmission Electron Microscopy (cryoTEM), have provided crucial insights into the nanostructure of the precursor phase. These investigations reveal that what was previously described as liquid PILP droplets actually consists of 30-50 nm amorphous calcium carbonate (ACC) nanoparticles with ~2 nm nanoparticulate texture [10]. These nanoparticles appear to consist of assemblies of ~2 nm subunits, similar to those observed in polymer/ACC hydrogels using conventional TEM [10].

Crucially, cryoTEM studies show that these nanoparticles aggregate to form larger structures but do not coalesce to form continuous objects with smooth edges as would be expected for true liquid droplets [10]. Even after freeze-drying, the morphology of the aggregates retains its granular appearance, indicating they are formed by aggregation of nanoparticles rather than by their coalescence [10]. This nanogranular texture is consistently observed in both the PILP system and biominerals, creating a remnant texture from the accretion of precursor colloids [7].

The Role of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs)

The CAT model provides a framework for understanding the crucial role that intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) play in modulating biomineralization processes. At the time of the original PILP discovery, it was not recognized that the charged proteins intimately associated with biominerals are often IDPs [2] [7]. These biopolymers interact strongly with ACC in the early stages of mineralization and become excluded during crystallization [10].

The presence of charged polymers such as poly(aspartic acid) (pAsp), poly(acrylic acid) (pAA), poly(allylamine hydrochloride) (pAH), and double-stranded DNA creates a stabilized nanogranular phase that exhibits the liquid-like behavior at macroscopic scales [10]. This polymer-stabilized colloidal liquid explains the unusual flow behavior of the precursor phase, such as why streams of the phase only slowly coalesce over time [7]. The consistency of the precursor phase suggests a viscoelastic material that arises from some type of non-covalent crosslinking, possibly through calcium-mediated crosslinks with the intercalated polymer chains or hydrogen-bonding networks between polymer and hydrogenated carbonates [7].

Table 2: Key Experimental Evidence Supporting the CAT Model Over Traditional PILP

| Experimental Observation | Technique(s) Used | Interpretation in PILP Model | Interpretation in CAT Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30-50 nm particles with ~2 nm substructure [10] | CryoTEM, NMR | Liquid droplets with undefined internal structure | Assembly of ACC clusters forming nanogranular colloids |

| Gel-like elasticity [10] | Rheology, AFM | Anomalous property for a liquid | Expected behavior for polymer-stabilized colloidal assembly |

| Complete wetting OR non-wetting on substrates [10] | Contact angle measurements | Unexplained extreme wetting behavior | Consistent with nanogranular surface properties |

| Remnant nanogranular texture in biominerals [7] | SEM, TEM, CryoTEM | Not directly addressed | Fundamental signature of the colloidal assembly process |

| Polymer exclusion during crystallization [7] [10] | Various spectroscopic methods | Impurity exclusion | Natural consequence of colloidal transformation |

Methodological Approaches for Studying CAT Pathways

Essential Characterization Techniques

Understanding the CAT pathway requires a multidisciplinary approach using complementary characterization techniques. Microscopy methods are particularly crucial for visualizing the different stages of colloidal assembly and transformation. The following table summarizes key techniques and their applications in CAT research:

Table 3: Essential Methodologies for Characterizing the CAT Process

| Technique | Key Application in CAT Research | Technical Considerations | Information Gained |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cryogenic TEM | Visualization of native hydrated precursors [22] [10] | Rapid vitrification preserves native structure; Requires specialized equipment [10] | Nanoscale architecture; Particle size and assembly state; Internal texture of precursors |

| Solid-State NMR | Molecular-level structure of amorphous phases [10] | Can study non-crystalline materials; Provides local chemical environment | Polymer-mineral interactions; Coordination environment; Phase composition |

| SEM | Morphology of deposited films and crystals [10] | Requires dry samples; Conductive coating often needed [22] | Surface topography; Macroscopic morphology; Evidence of precursor deposition |

| AFM | Surface topography and nanomechanical properties [22] | Can operate in liquid; High resolution surface mapping | Surface roughness; Mechanical properties; In situ transformation monitoring |

| Liquid-Phase TEM | Direct observation of dynamic processes [21] | Electron beam may alter process; Technical challenges [21] | Real-time transformation; Particle dynamics; Assembly processes |

Experimental Protocols for CAT System Investigation

Based on published studies of PILP/CAT systems, the following detailed methodology can be employed to investigate the colloid assembly and transformation process, with particular focus on the well-characterized calcium carbonate system:

Protocol 1: Standard CAT System Preparation for Calcium Carbonate

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a calcium chloride solution ( typically 2-10 mM CaCl₂ in deionized water) and a sodium carbonate solution (2-10 mM Na₂CO₃ in deionized water). Add the charged polymer additive (e.g., poly(aspartic acid), mw = 2000-11000 g/mol) to the calcium solution at concentrations ranging from 10-100 μg/mL, depending on the desired effect [10].

- Mixing Procedure: Mix the solutions rapidly at room temperature using equal volumes. Various mixing strategies can be employed, including direct pipetting, vortex mixing, or using specialized microfluidic devices to control mixing dynamics [21].

- Incubation and Sampling: Allow the mixture to stand undisturbed or with gentle agitation. Sample at regular time intervals (e.g., 5 min, 30 min, 2 h, 6 h, 24 h) for characterization. Early time points ( minutes to a few hours) capture the colloidal assembly stage, while later time points (hours to days) capture the transformation process [10].

- Substrate Deposition (Optional): For film formation studies, immerse substrates (e.g., clean glass slides, TEM grids, or functionalized surfaces) in the reaction solution at various time points. Remove after specific durations for analysis of deposited materials [10].

Protocol 2: CryoTEM Sample Preparation and Imaging

- Grid Preparation: Apply 3-5 μL of the sample to a freshly glow-discharged TEM grid with a continuous carbon film [10].

- Vitrification: Blot the grid to remove excess liquid and immediately plunge-freeze into liquid ethane cooled by liquid nitrogen using a vitrification device [10].

- Transfer and Storage: Transfer the vitrified grid under liquid nitrogen to a cryo-TEM holder, maintaining temperatures below -170°C throughout [10].

- Imaging: Acquire images using low-dose conditions at accelerating voltages typically between 200-300 kV to minimize radiation damage. Take images at various magnifications to capture both the overall assembly structure and fine nanoscale details [10].

The experimental workflow for investigating CAT pathways involves multiple parallel characterization approaches, as visualized in the following diagram:

CAT Investigation Workflow: This diagram illustrates the integrated experimental approach for studying Colloid Assembly and Transformation pathways, connecting temporal stages with appropriate characterization techniques.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table compiles key research reagents and materials essential for investigating CAT pathways, with a focus on the well-characterized calcium carbonate system:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for CAT Investigations

| Reagent/Material | Function in CAT Research | Typical Specifications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poly(aspartic acid) [10] | Model anionic polymer for inducing colloidal phase; mimics acidic biomineralization proteins | MW: 2,000-11,000 g/mol; Concentration: 10-100 μg/mL [10] | Charge density crucial; Lower MW often more effective; Sterility may be required for bio-related studies |

| Poly(acrylic acid) [10] | Alternative anionic polymer for comparative studies | Various molecular weights; Similar concentration range to pAsp | Different binding affinity compared to pAsp; Useful for establishing general principles |

| Double-stranded DNA [10] | Structurally defined polyanion; Allows visualization in cryoTEM due to 2.4 nm diameter | Salmon sperm DNA or synthetic oligonucleotides; Phosphate groups enable NMR detection [10] | Unique opportunity for simultaneous visualization and spectroscopic tracking |

| Calcium Chloride (CaClâ‚‚) | Calcium ion source for carbonate and phosphate systems | High purity (>99%); Typically 2-20 mM concentration [10] [21] | Must be prepared fresh; Concentration affects nucleation kinetics; pH may need adjustment |

| Sodium Carbonate (Na₂CO₃) | Carbonate ion source | High purity (>99%); Typically 2-20 mM concentration [21] | Solution stability limited; Sensitive to CO₂ absorption; Prepare immediately before use |

| Polycarbonate Membranes [10] | Nanoporous substrates for testing infiltration capability of precursor | Pore sizes: 50-200 nm; Track-etch type [10] | Enables assessment of liquid-like behavior through pore infiltration assays |

| Functionalized Substrates | Surface for deposition studies; Tests wetting behavior | Glass, silicon, mica; Often with specific surface treatments or functionalizations [10] | Surface charge and chemistry dramatically affect deposition and wetting behavior |

| Staunoside E | Staunoside E, CAS:155661-21-5, MF:C66H108O33, MW:1429.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Naphthgeranine C | Naphthgeranine C | Naphthgeranine C for research applications. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

Implications and Future Research Directions

The adoption of the CAT terminology has significant implications for both fundamental understanding of biomineralization and practical applications in materials design. By more accurately representing the physical state and transformation pathway of the precursor phase, the CAT framework provides new insights into the remarkable mechanical properties of biominerals. The nanogranular textures and layering observed in many biominerals, which were previously assumed to result primarily from cellular control, may instead be inherent features of the CAT pathway [7]. Evolutionary selection would therefore include both mesoscale textures created by this formation mechanism as well as deliberate cell-controlled microstructures [7].

Future research directions should focus on several key areas. First, rigorous demonstration of true liquid character versus viscoelastic colloidal assembly remains challenging, as cryoTEM and X-ray scattering methods cannot definitively distinguish between liquid and solid amorphous structures, while liquid-phase TEM observations may interfere with the real crystallization process [21]. Second, systematic exploration of structure and dynamics across different mineral systems down to the atom and sub-millisecond scales is needed to establish universal principles of the CAT pathway [21]. Finally, integrated experimental-theoretical approaches capturing both thermodynamic and kinetic factors will be essential for the rational design of materials and controlled nanoparticle morphologies through CAT-mediated pathways [21].

The CAT model system has proven invaluable for deciphering the key role that biopolymers, particularly IDPs, play in modulating biomineralization processes - insights that were not readily accomplished in living biological systems [2] [7]. As research continues to address the remaining challenges in understanding the organic-inorganic interactions involved in biomineralization, the CAT framework provides a solid conceptual foundation for exploring the simple, yet complex, crystallization pathway that governs the formation of many biominerals and biomimetic materials.