Nucleation and Growth in Inorganic Crystal Formation: Mechanisms, Control, and Pharmaceutical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of recent advances in the nucleation and growth of inorganic crystals, with a specific focus on implications for pharmaceutical development.

Nucleation and Growth in Inorganic Crystal Formation: Mechanisms, Control, and Pharmaceutical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of recent advances in the nucleation and growth of inorganic crystals, with a specific focus on implications for pharmaceutical development. It explores fundamental mechanisms, including classical and non-classical pathways, and highlights the critical role of solvent entropy and pre-nucleation clusters. The scope extends to modern methodological approaches for controlling crystallization, from computational predictive tools like ADDICT to process intensification strategies such as membrane crystallization. Practical guidance for troubleshooting common crystal growth issues and optimizing polymorph control is presented. Finally, the article covers validation and comparative frameworks, using case studies of common gas hydrate formers to illustrate how kinetic and thermodynamic analyses ensure the selection of optimal crystalline forms for drug efficacy and stability. This resource is tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals engaged in drug development who seek to leverage crystal engineering for improved pharmaceutical outcomes.

The Fundamental Principles of Inorganic Crystal Nucleation and Growth

Crystal nucleation, the process by which atoms, ions, or molecules first arrange into a stable solid phase, is a fundamental phenomenon governing the synthesis of materials ranging from pharmaceuticals to semiconductors. For decades, the scientific understanding of this initial stage was dominated by Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT), which posits that crystals form via the direct, monomer-by-monomer addition of building blocks to a nascent cluster [1]. Once this cluster reaches a critical size, it becomes stable and proceeds to grow. However, advancements in experimental and theoretical methods have revealed that many materials, including inorganic crystals, follow more complex non-classical pathways that deviate significantly from this classical picture [1] [2] [3]. These pathways often involve transient, intermediate phases that are absent in the final crystal structure, presenting both challenges and opportunities for controlling material properties. This whitepaper rethinks the initial stages of inorganic crystal formation by synthesizing current research on classical and non-classical nucleation, providing a technical guide for researchers and scientists engaged in crystal engineering and drug development.

Theoretical Foundations: From Classical to Non-Classical Frameworks

Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT)

Classical Nucleation Theory provides a foundational, albeit simplified, model for quantifying nucleation. CNT treats the formation of a new phase as a process governed by the balance between the volume free energy gain of forming a more stable phase and the surface free energy cost of creating a new interface. A central concept is the critical nucleus, a cluster of a specific size that has a 50% probability of either growing into a crystal or dissolving. Nuclei smaller than this critical size are unstable, while those larger are likely to continue growing [1]. The theory is mathematically elegant and allows for the calculation of key parameters such as nucleation rates and free energy barriers. However, its major limitation lies in its underlying assumption: that the nucleus is a miniature version of the final, bulk crystal, and that its structure forms through the direct, one-by-one addition of atoms or molecules from a solution or vapor [1] [2].

The Non-Classical Paradigm

In contrast to CNT, non-classical crystallization (NCC) encompasses mechanisms where nucleation does not proceed via a single step of monomer addition. A key feature of NCC is the involvement of precursor particles that are more complex than the single atoms or molecules assumed in CNT [1]. These precursors can be nanoparticles, dense liquid phases, or amorphous intermediates. Two prominent non-classical mechanisms are:

- The Pre-Nucleation Cluster (PNC) Pathway: In this pathway, stable molecular clusters form in solution before a distinct solid nucleus appears. These PNCs are dynamic entities that can aggregate and restructure, ultimately serving as building blocks for the crystalline phase [1].

- Two-Step Nucleation Mechanism: This widely observed mechanism involves the initial separation of a dense, often liquid-like phase from the solution. Within this dense droplet, which can lower the overall energy barrier for nucleation, the process of ordering into a crystal subsequently occurs [2]. As one study notes, for crystallization, this involves "the formation of a dense-solution droplet followed by ordering originating at the core of the droplet" [2].

It is increasingly recognized that real-world nucleation pathways are not purely classical or defined by a single non-classical theory. Instead, they are often an amalgamation of multiple mechanisms, with systems following the path of least resistance dictated by their specific thermodynamic and kinetic landscapes [1] [2].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Classical and Non-Classical Nucleation Theories

| Feature | Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) | Non-Classical Crystallization (NCC) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Building Block | Atoms, ions, or single molecules (monomers) [1] | Complex precursors (e.g., nanoparticles, dense liquid phases, pre-nucleation clusters) [1] |

| Nucleation Process | Single-step, direct monomer-by-monomer addition [1] | Multi-step, often involving intermediate phases [2] |

| Nature of Intermediate | A single, critical-sized solid nucleus with the same structure as the bulk crystal [1] | Various metastable intermediates (e.g., amorphous blobs, liquid droplets, pre-nucleation clusters) [1] [4] |

| Pathway Complexity | Single, well-defined pathway | Multiple, system-dependent pathways; an amalgamation of mechanisms [1] |

| Energy Landscape | A single free energy barrier to overcome [1] | Multiple energy barriers associated with phase separation and ordering [2] |

Direct Experimental Evidence for Non-Classical Pathways

Advanced in situ characterization techniques have been pivotal in providing direct evidence for non-classical nucleation, moving beyond the inferential understanding provided by ex situ studies.

Liquid Phase Electron Microscopy (LPEM) of Organic Pharmaceuticals

LPEM has enabled the high-resolution observation of nucleation events in a native, liquid environment. A landmark study on the pharmaceutical compound flufenamic acid (FFA) in ethanol directly captured its non-classical pathway. The observations suggested that the system followed a Pre-Nucleation Cluster (PNC) pathway with features consistent with two-step nucleation [1]. The experiment visualized nanoscale intermediate pre-crystalline stages, providing evidence that the formation of crystalline FFA proceeded through the aggregation and reorganization of clusters rather than direct monomer addition. In these experiments, the electron beam itself was exploited to induce nucleation via radiolysis of the solvent, which altered the local chemical environment and lowered the energy barrier for nucleation [1]. This work underscores the critical role of direct observation in uncovering the complex, multi-step journey from a disordered solution to an ordered crystal.

Studies on Ionic Colloidal Crystals as Model Systems

Research using charged colloidal particles as model "ions" has offered profound insights into non-classical mechanisms, as their assembly can be directly observed with optical microscopy. A recent study demonstrated that ionic colloidal crystals form via a two-step process [4]. First, a gas-like suspension of particles rapidly condenses into metastable, amorphous blobs—a dense liquid phase. Crystal nucleation then initiates within these blobs, with a crystallization front propagating through them to form ordered crystallites [4].

Following nucleation, the crystals grow through several simultaneous, non-classical processes, detailed in Table 2.

Table 2: Non-Classical Growth Mechanisms Observed in Ionic Colloidal Crystals

| Growth Mechanism | Description | Experimental Observation |

|---|---|---|

| Monomer Addition | Individual particles from the solution (gas phase) attach to the crystal one-by-one [4] | Isolated crystals in contact with the gas phase grow at steady rates [4] |

| Ostwald Ripening | Larger crystals grow at the expense of smaller, less stable ones via particle exchange through the solution [4] | Net growth of crystals without direct contact with dissolving blobs [4] |

| Blob Absorption | Direct, rapid integration of an entire amorphous blob into a growing crystal upon contact [4] | Rapid deflation of the blob and appearance of surface waves propagating from blob to crystal [4] |

| Oriented Attachment | Two crystals fuse along a common crystallographic orientation to form a larger, single crystal [4] | Crystals align before merging; the contact region melts and re-crystallizes, eliminating the seam [4] |

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations of Metal Nucleation

Computational studies have provided atomic-scale insights that complement experimental findings. MD simulations of the homogeneous nucleation of a BCC phase within FCC iron revealed that the atomic system circumvents the high energy barrier predicted by CNT by opting for alternative, non-classical nucleation processes [5]. The two key mechanisms identified were the coalescence of subcritical clusters and stepwise nucleation [5]. This demonstrates that non-classical pathways are not limited to soft or organic materials but are also highly relevant in metallic systems, highlighting their broad applicability in materials science.

Methodologies for Investigating Nucleation Pathways

Experimental Protocols

Liquid Phase Electron Microscopy (LPEM) for Organic Molecules

Objective: To directly observe the nanoscale early-stage nucleation events of small organic molecules, such as Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs), in their native liquid environment [1].

Materials:

- Liquid Phase EM Holder: A specialized TEM holder capable of sealing a liquid cell between electron-transparent windows (e.g., silicon nitride windows).

- Sample Solution: The molecule of interest dissolved in a suitable solvent. For flufenamic acid, a 50 mM solution in ethanol was used [1].

- Syringe Pump System: For loading and flowing the solution through the liquid cell, if desired.

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Assemble the liquid cell according to the manufacturer's instructions, ensuring the silicon nitride windows are clean and properly spaced.

- Sample Loading: Use the syringe pump to fill the liquid cell with the sample solution, avoiding bubble formation.

- Microscope Setup: Insert the holder into the transmission electron microscope. Locate a suitable area of the liquid cell for observation.

- Beam-Induced Nucleation: To initiate nucleation, condense the electron beam using the monochromator to increase the electron flux (dose > 150 eâ»/Ų/s) in the illuminated region. This exploits radiolysis to alter the local environment and induce nucleation [1].

- Data Acquisition: Acquire images or video streams at a high temporal resolution to capture the dynamics of pre-nucleation cluster formation, aggregation, and crystal growth. Use low-dose techniques where possible to minimize beam effects, though higher doses are often necessary to induce the process [1].

- Troubleshooting: A lack of nucleation events and scarring of the silicon nitride windows can indicate an absence of solution between the windows. Flushing the system with a solvent like water can dislodge particulates [1].

Continuous Dialysis for Ionic Colloidal Crystallization

Objective: To spatiotemporally control particle interaction strength and observe the resulting crystallization pathways of ionic colloidal particles [4].

Materials:

- Oppositely-Charged Colloidal Particles: Synthesized or commercial particles coated with a neutral polymer brush (e.g., polystyrene particles).

- Observation Cell: A sealed capillary or customized cell for microscopy.

- Dialysis System: A deionized water reservoir connected to the observation cell to allow for controlled salt removal.

- Salt Solutions: To prepare particles at a precisely known initial ionic strength.

Procedure:

- Particle Preparation: Disperse positively and negatively charged particles in the same salt solution at the desired initial high concentration (e.g., 100 mM) to maintain a stable, gas-like state [4].

- Mixing: Mix the two particle populations in an approximately 1:1 stoichiometric ratio and immediately transfer the mixture to the observation cell.

- Initiate Dialysis: Connect the observation cell to the deionized water reservoir. Salt will begin to diffuse out of the cell into the reservoir, leading to a gradual and continuous increase in the Debye length (λD) and the strength of electrostatic interactions between particles [4].

- Real-Time Observation: Use bright-field or confocal microscopy to monitor the assembly process as the interaction strength increases over time.

- Pathway Identification: Observe the sequence of phases: from gas, to the potential formation of amorphous blobs (two-step pathway), to the eventual nucleation and growth of crystals. The specific pathway (classical vs. non-classical) can be correlated with the locally evolving salt concentration [4].

- Post-Experiment Analysis: Characterize the final crystal structures and quality using techniques like SEM and confocal microscopy. Map these outcomes back to the interaction strength conditions that produced them.

Theoretical and Computational Framework

Classical Density Functional Theory (cDFT) has emerged as a powerful ab initio theoretical tool for predicting nucleation pathways. When combined with stochastic process theory, it can form a comprehensive theoretical description of nucleation [2]. This combined framework requires only the interatomic interaction potential as input and can predict non-classical pathways without pre-defining collective variables. The theory models the system as a fluctuating density field, n^t(r), evolving according to a stochastic equation that includes deterministic diffusion driven by free energy minimization and a stochastic noise term representing random collisions from the solvent [2]. By applying rare event techniques to this framework, researchers can compute the most probable path from a homogeneous solution to a crystalline cluster, revealing multi-step mechanisms like dense droplet formation followed by internal ordering [2].

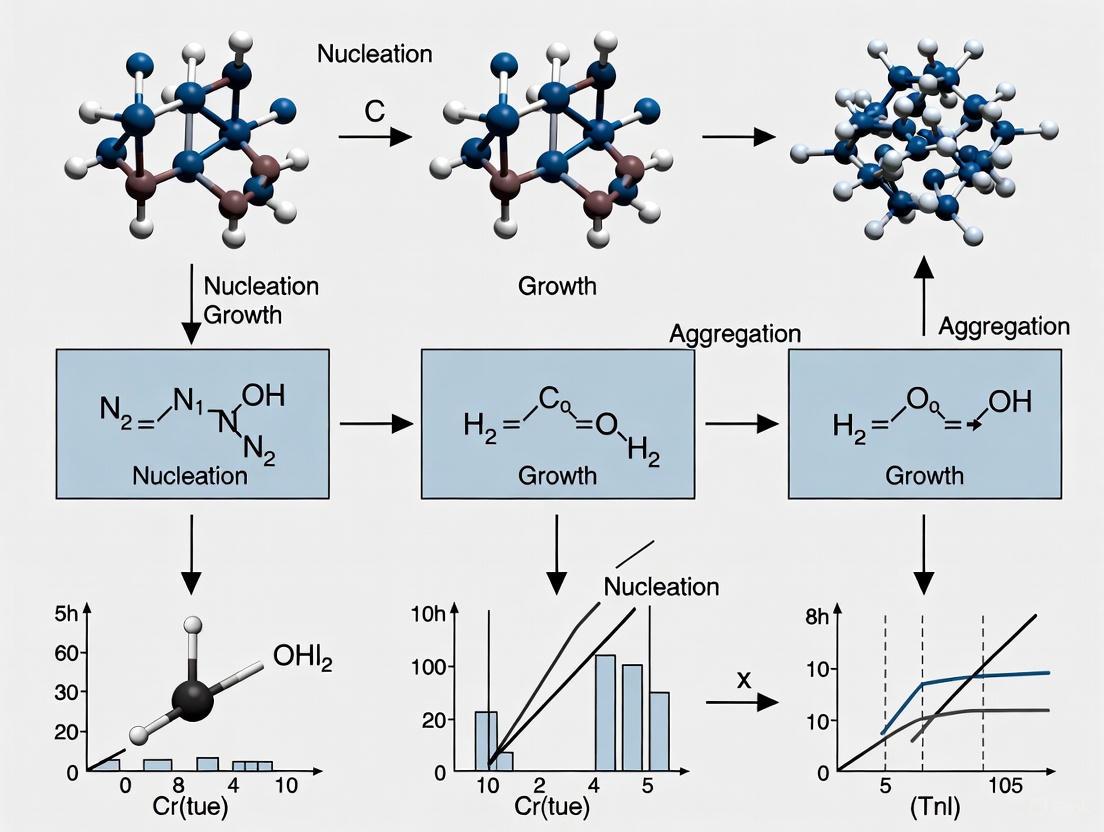

Diagram 1: A generalized non-classical nucleation pathway showing key intermediate stages, from pre-nucleation clusters to a macroscopic crystal.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Nucleation Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Phase EM Holder | Enables direct observation of nucleation in a liquid environment within an electron microscope [1]. | Observing pre-nucleation clusters of flufenamic acid in ethanol [1]. |

| Silicon Nitride Windows | Electron-transparent membranes that encapsulate the liquid sample in LPEM [1]. | Creating a sealed microchamber for the sample solution in TEM [1]. |

| Oppositely-Charged Colloids | Model systems that mimic atomic ions, allowing direct optical observation of crystallization [4]. | Studying two-step nucleation and growth mechanisms in binary ionic colloidal crystals [4]. |

| Continuous Dialysis Setup | Provides spatiotemporal control over interaction strength by dynamically varying salt concentration [4]. | Mapping crystallization pathways as a function of Debye length in a single experiment [4]. |

| Cryogenic TEM (cryo-TEM) | Snapshots of near-native states in solution by vitrifying samples, capturing transient intermediates [3]. | Studying the isolated stages of pre-nucleation events in organic aromatic compounds [1]. |

| Mandyphos SL-M012-1 | Mandyphos SL-M012-1, CAS:831226-37-0, MF:C56H58FeN2P2, MW:876.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (S)-Metalaxyl | (S)-Metalaxyl, CAS:69516-34-3, MF:C15H21NO4, MW:279.33 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implications for Inorganic Crystal Formation and Drug Development

The paradigm shift towards non-classical nucleation has profound implications for material synthesis and control. In the context of inorganic crystal formation, understanding and harnessing these pathways allows for the precise engineering of crystal size, morphology, structure, and ultimately, material properties. The discovery of non-classical pathways involving amorphous precursors or dense liquid phases provides new levers to pull in the synthesis of complex inorganic materials, from geologically relevant minerals like calcium carbonate to advanced technological materials [2] [3].

For the pharmaceutical industry, where the crystal structure (polymorph) of an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) dictates its solubility, stability, and bioavailability, controlling nucleation is paramount [1] [3]. The presence of intermediate stages in non-classical pathways means that previously inaccessible polymorphs with more desirable properties might be present during crystallization. Direct observation of these pathways, as demonstrated with flufenamic acid, opens avenues to direct polymorph selection and improve the efficacy of drug products [1]. Furthermore, this knowledge is critical for adapting API production from traditional batch manufacturing to more efficient continuous manufacturing processes, where a deep understanding of nucleation is essential for control and reproducibility [1].

The initial stages of crystal formation are far more complex and rich than previously envisioned by Classical Nucleation Theory. Direct observations powered by techniques like LPEM and model colloidal systems, combined with advanced theoretical frameworks like cDFT, have firmly established that non-classical pathways are common across material classes. These pathways, often involving pre-nucleation clusters, dense liquid phases, and complex growth mechanisms like oriented attachment, represent the rule rather than the exception. For researchers in inorganic crystal formation and drug development, embracing this complexity is no longer optional. The future of controlled material synthesis lies in leveraging in situ characterization and theoretical guidance to decipher, predict, and ultimately direct these non-classical pathways to achieve tailored crystalline materials.

The Critical Role of Solvent and Entropy in Aqueous Crystallization

Crystallization from aqueous solution represents a fundamental process with profound implications across diverse scientific and industrial domains, from pharmaceutical development to geochemical mineralization. Traditional approaches to crystallization have predominantly focused on solute behavior, considering the solvent as a passive medium. However, contemporary research has fundamentally shifted this perspective, revealing that solvent entropy and structured water layers at molecular interfaces play a decisive role in governing nucleation and crystal growth pathways [6] [7]. Within the broader context of nucleation and growth research in inorganic crystal formation, understanding these solvent-mediated effects has become paramount for predicting and controlling crystallization outcomes. This paradigm recognizes that water is not merely a background matrix but an active participant whose reorganization during phase transitions provides critical thermodynamic driving forces that can supersede the contributions of enthalpy in many crystallizing systems [6]. The implications extend to fundamental science and applied technologies, enabling more precise control over polymorph selection, crystal morphology, and material properties in fields ranging from pharmaceutical manufacturing to environmental science.

The following sections examine the thermodynamic foundations of solvent entropy contributions, experimental evidence across protein and inorganic systems, advanced characterization methodologies, and emerging non-classical crystallization pathways. By synthesizing recent developments in this rapidly evolving field, this review aims to equip researchers with both theoretical frameworks and practical approaches for leveraging solvent entropy effects in crystallization process design.

Thermodynamic Foundations of Solvent Entropy Contributions

The crystallization process from aqueous solution is governed by the change in Gibbs free energy (ΔG), which at constant temperature and pressure can be expressed through the classic relationship:

| Thermodynamic Parameter | Symbol | Typical Range for Proteins | Contribution to Crystallization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gibbs Free Energy Change | ΔG | -10 to -100 kJ molâ»Â¹ | Must be negative for spontaneous crystallization |

| Enthalpy Change | ΔH | -70 kJ molâ»Â¹ (lysozyme) to +155 kJ molâ»Â¹ (HbC) | Can be favorable or unfavorable |

| Total Entropy Change | TΔS | Varies widely | Must overcome entropy loss from molecular ordering |

| Protein Entropy Cost | TΔSprotein | -30 to -100 kJ molâ»Â¹ (at 298K) | Always unfavorable due to ordering |

| Solvent Entropy Gain | TΔSsolvent | +60 to +180 kJ molâ»Â¹ (at 298K) | Primary driving force in many systems |

Table 1: Thermodynamic parameters governing protein crystallization from aqueous solutions, compiled from experimental studies [8] [6].

For crystallization to occur spontaneously, ΔG must be negative, which requires that the TΔS term sufficiently outweighs any positive ΔH contribution. The total entropy change (ΔStotal) can be deconvoluted into two competing contributions:

where ΔSsolvent represents the entropy change from water restructuring and ΔSprotein encompasses the entropy loss from ordering of the protein molecules [6]. The protein entropy cost arises from the loss of six translational and rotational degrees of freedom per molecule, partially compensated by newly created vibrational modes, resulting in an unfavorable change estimated at -100 to -300 J molâ»Â¹ Kâ»Â¹ [6]. At room temperature, this translates to an energy penalty of 30-100 kJ molâ»Â¹ that must be overcome by favorable contributions.

The critical insight from recent research is that the dominant favorable contribution typically comes from ΔSsolvent, which can reach +100 to +600 J molâ»Â¹ Kâ»Â¹, corresponding to the release of approximately 5 to 30 water molecules upon incorporation of each protein molecule into the crystal lattice [6]. This release of structured water from protein surfaces represents the main thermodynamic driving force for crystallization, particularly in systems with unfavorable enthalpy changes.

Figure 1: Thermodynamic pathway of solvent entropy gain during crystal contact formation, highlighting water release as the key driving force.

The magnitude of this solvent entropy effect is substantial, with each released water molecule contributing approximately +22 J molâ»Â¹ Kâ»Â¹ when transferred from clathrate, crystal hydrate, or other ice-like structures to the bulk state [6]. This fundamental thermodynamic mechanism explains why proteins with dramatically different enthalpy signatures can successfully crystallize, provided the solvent entropy gain is sufficient to overcome both the unfavorable protein ordering and any positive enthalpy barriers.

Experimental Evidence Across Material Systems

Protein Crystallization Systems

Comprehensive thermodynamic studies across multiple protein systems have revealed striking diversity in how solvent entropy contributions manifest:

Hemoglobin C (HbC): Exhibits strong retrograde solubility with a surprisingly large positive enthalpy of crystallization (ΔH = +155 kJ molâ»Â¹), meaning crystallization is thermodynamically impossible without compensatory entropy gains. The massive entropy gain of +610 J molâ»Â¹ Kâ»Â¹ stems from the release of up to 10 water molecules per protein intermolecular contact, providing the exclusive driving force for crystallization [8] [6].

Apoferritin: Represents an intermediate case with enthalpy of crystallization near zero (ΔH ≈ 0), where the entropy gain from release of approximately two water molecules bound to each protein molecule in solution constitutes the main component of the crystallization driving force [8].

Lysozyme: Demonstrates more conventional behavior with moderate negative enthalpy (ΔH = -70 kJ molâ»Â¹), but interestingly exhibits a negative solvent entropy effect that increases solubility, highlighting that water restructuring can sometimes oppose crystallization depending on specific surface properties [6].

These case studies collectively establish that solvent entropy effects are not merely minor contributors but can serve as the dominant factor determining crystallizability across diverse protein systems.

Inorganic Ionic Materials

Recent research has revealed parallel solvent entropy effects in inorganic crystallization systems, challenging classical models that overlook solvent contributions:

Interfacial Energy Relationships: Studies of salt crystallization in membrane distillation systems have demonstrated that crystal-liquid interfacial energy (σ) directly correlates with nucleation rates and induction times [9]. Highly soluble salts with low interfacial energy require limited relative supersaturation (Δc/c) and favor heterogeneous nucleation mechanisms, while less soluble salts with high interfacial energy require substantial supersaturation thresholds (Δc/c > 1) to overcome nucleation barriers, frequently favoring homogeneous primary nucleation in bulk solution [9].

Solid Solution Systems: Research on binary solid solution-aqueous solution (SS-AS) systems like (Ba,Sr)SO₄ has established that interfacial free energy (σhkl(x)) varies systematically with solid solution composition, directly impacting growth rates according to both spiral growth and two-dimensional nucleation mechanisms [10]. This composition-dependent interfacial energy influences sectoral zoning patterns and ultimately determines the compositional partitioning during crystallization.

| Material System | Key Solvent Entropy Observation | Experimental Method | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin C | Release of ~10 Hâ‚‚O molecules per contact (+610 J molâ»Â¹ Kâ»Â¹) | Solubility measurements, AFM | Solvent entropy can overcome strongly unfavorable enthalpy (+155 kJ molâ»Â¹) |

| Apoferritin | Release of ~2 Hâ‚‚O molecules per protein | Solubility measurements, AFM | Near-zero enthalpy systems driven entirely by solvent entropy |

| Lysozyme | Negative solvent entropy contribution | Thermodynamic analysis | Water restructuring can sometimes oppose crystallization |

| (Ba,Sr)SOâ‚„ solid solutions | Interfacial energy varies with composition | AFM, growth rate measurements | Growth mechanisms transition with supersaturation and composition |

| Highly soluble salts | Low interfacial energy favors heterogeneous nucleation | Induction time measurements | Scaling correlated with nucleation theory predictions |

Table 2: Experimental evidence of solvent entropy effects across protein and inorganic material systems [9] [10] [8].

The experimental evidence across these diverse systems underscores the universal importance of solvent entropy contributions in aqueous crystallization, while highlighting the system-specific manifestations that depend on molecular surface properties and solution conditions.

Methodologies for Characterizing Solvent Entropy Effects

Thermodynamic Measurement Approaches

Accurate determination of solvent entropy contributions requires sophisticated experimental methodologies that can deconvolute competing thermodynamic parameters:

Temperature-Dependent Solubility Studies: The temperature dependence of protein solubility enables determination of both ΔH and ΔS of crystallization through van't Hoff analysis. For HbC, this approach revealed the surprising positive enthalpy that highlighted the dominant role of entropy [11] [8]. Modern implementations use miniaturized scintillation techniques to determine temperatures at which solutions reach equilibrium with existing crystals across carefully controlled temperature gradients [11].

In-Situ Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM): Molecular-resolution AFM imaging of growing crystal surfaces provides direct visualization of growth sites and their densities, enabling calculation of crystallization free energy and correlation with water release estimates [8] [6]. This technique has confirmed excellent agreement between observed growth site densities and values calculated from crystallization free energies determined independently through solubility measurements [8].

Isothermal Induction Time Measurements: For inorganic systems and small organic molecules, determination of nucleation kinetics through induction time experiments at constant supersaturation enables application of classical nucleation theory to extract interfacial energies and critical nucleus parameters [9] [12]. This approach has been successfully applied to pharmaceutical systems like ritonavir to quantify how solvent selection affects nucleation barriers [12].

Computational and Molecular Modeling Approaches

Complementary computational methods provide molecular-level insights into solvent organization and its thermodynamic consequences:

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: All-atom MD simulations with explicit solvent models can capture the dynamic interplay between inter- and intramolecular interactions, revealing how solvent molecules organize around solute surfaces and how this organization changes during nucleation events [12]. Recent MD studies of ritonavir in multiple solvents have elucidated conformational preferences and solute-solvent interaction patterns that explain observed nucleation behaviors [12].

Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) Calculations: These specialized MD simulations quantitatively predict solvation energies across different solvent environments, providing mechanistic understanding of how solvent selection influences nucleation kinetics and polymorphic outcomes [12].

Interfacial Energy Calculations: For solid solution systems, generalized crystal growth equations incorporating composition-dependent interfacial energies enable prediction of growth rate distributions as functions of both solid and aqueous solution compositions [10].

Figure 2: Methodological approaches for characterizing solvent entropy effects in aqueous crystallization, integrating experimental and computational techniques.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function in Crystallization Research | Specific Applications |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Proteins (HbC, apoferritin, lysozyme) | Model systems for thermodynamic studies | Temperature-dependent solubility measurements [11] [8] |

| Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) | Molecular-resolution imaging of growth interfaces | In-situ observation of crystal surface processes [10] [6] |

| Miniaturized Crystallization Platforms | High-throughput screening of conditions | Scintillation techniques for solubility determination [11] |

| Molecular Dynamics Software (GROMACS, AMBER) | Simulation of solute-solvent interactions | Modeling water structuring and release events [12] |

| Turbidometric Detection Systems | Monitoring nucleation induction times | Classical nucleation theory parameter extraction [12] |

| Controlled Composition Solutions | Solid solution-aqueous solution studies | Examining composition-dependent interfacial energy [10] |

| C.I. Acid Violet 48 | C.I. Acid Violet 48, CAS:73398-28-4, MF:C37H38N2Na2O9S2, MW:764.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Santonic acid | Santonic Acid|95% | Santonic acid is a high-purity sesquiterpenoid derivative for research applications. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for investigating solvent entropy effects in crystallization.

Implications for Nucleation and Crystal Growth Mechanisms

Non-Classical Crystallization Pathways

Recent advances have revealed that solvent entropy effects play crucial roles in non-classical crystallization pathways that diverge from traditional models:

Pre-Nucleation Clusters: Evidence suggests that structured solvent layers influence the stability and behavior of pre-nucleation clusters, which represent thermodynamically stable intermediate species in multi-step nucleation pathways [7]. The reorganization of water molecules during the transition from dispersed clusters to amorphous precursors contributes significantly to the overall thermodynamics of nucleation.

Two-Step Nucleation Mechanisms: In many systems, nucleation proceeds through an initial dense liquid phase that subsequently orders into crystalline material, with solvent release occurring primarily during the ordering step rather than initial cluster formation [7]. This pathway can reduce the overall kinetic barrier to nucleation by separating the processes of density fluctuation and structural ordering.

Compositional Zoning in Solid Solutions: The variation of interfacial energy with solid solution composition directly impacts growth mechanisms, leading to phenomena such as intrasectorial, sectorial, and progressive zoning commonly observed in mineral systems [10]. These patterns reflect kinetic competition between different growth mechanisms (spiral growth versus two-dimensional nucleation) that are influenced by solvent entropy effects at the crystal-solution interface.

Interfacial Energy and Nucleation Kinetics

The crystal-liquid interfacial energy (σ) represents a direct manifestation of solvent entropy effects at nucleation interfaces, with profound implications for crystallization behavior:

Nucleation Rate Dependence: According to classical nucleation theory, the nucleation rate (J) depends exponentially on σ³, making it exquisitely sensitive to interfacial energy [9] [12]. Small changes in σ resulting from solvent restructuring can alter nucleation rates by orders of magnitude, explaining the dramatic impact of solvent selection on crystallization outcomes.

Polymorphic Selection: In pharmaceutical systems like ritonavir, solvent-dependent interfacial energies directly influence which polymorph nucleates under given conditions [12]. The metastable form I of ritonavir nucleates preferentially from solvents like acetone, ethyl acetate, acetonitrile, and toluene, while the stable form II emerges from ethanol, correlating with calculated solute solvation free energies and desolvation behavior [12].

Heterogeneous vs. Homogeneous Nucleation: The magnitude of interfacial energy determines the relative advantage of heterogeneous versus homogeneous nucleation pathways [9]. Systems with high interfacial energy exhibit stronger supersaturation thresholds and greater propensity for homogeneous nucleation in the bulk solution, while low interfacial energy systems nucleate more readily on existing surfaces.

The critical role of solvent entropy in aqueous crystallization represents a fundamental shift in our understanding of nucleation and crystal growth mechanisms. Rather than serving as a passive medium, water actively participates in crystallization thermodynamics through structuring at molecular interfaces and release during phase transitions. This perspective successfully unifies diverse observations across protein crystallization, inorganic materials formation, and pharmaceutical polymorph selection.

Future research directions will likely focus on quantitative prediction of solvent entropy contributions through advanced computational models, direct experimental probes of water organization during early nucleation stages, and deliberate engineering of crystal surfaces to optimize solvent release effects. The emerging recognition that solvent entropy dominates crystallization thermodynamics in many systems promises to transform industrial crystallization processes through more rational solvent selection, additive design, and process condition optimization. By placing solvent contributions at the forefront of crystallization science, researchers can overcome traditional empirical approaches and develop predictive frameworks for controlling crystallization outcomes across diverse scientific and technological applications.

As the field continues to evolve, integration of solvent entropy considerations into crystallization modeling and process design will undoubtedly yield more robust control over polymorph selection, crystal habit, and material properties – ultimately enabling next-generation technologies across pharmaceuticals, materials science, and beyond.

In the realm of inorganic crystal formation research, controlling the nucleation and growth phases is paramount to obtaining materials with desired physicochemical properties. The pathways of crystallization are governed by the competing principles of kinetic and thermodynamic control, which directly influence the manifestation of either monotropic or enantiotropic solid-state systems. Kinetic control describes reactions or processes where the product composition is determined by the rate at which different products form, favoring the species with the lowest activation energy. In contrast, thermodynamic control prevails when the product composition is determined by the relative stability of the products, favoring the species with the lowest free energy, often achieved under conditions allowing for reversibility [13].

These control mechanisms profoundly impact crystalline material design, particularly in pharmaceutical development where different polymorphs can exhibit vastly different bioavailability, stability, and processability. This technical guide examines the core principles of kinetic and thermodynamic control within the context of inorganic crystal nucleation and growth, providing researchers with methodologies to navigate and manipulate monotropic and enantiotropic systems for advanced material design.

Fundamental Principles of Kinetic and Thermodynamic Control

Core Concepts and Energetic Landscapes

The competition between kinetic and thermodynamic control arises when reaction pathways lead to different products, and the reaction conditions influence the selectivity of the process [13]. The kinetic product forms faster due to a lower activation energy barrier, while the thermodynamic product is more stable and possesses a lower overall free energy.

Key Characteristics [13]:

- Kinetic Control: Dominates under low temperatures and short reaction times where reversibility is limited. The product ratio is determined by the difference in activation energies (ΔEa) of the competing pathways.

- Thermodynamic Control: Prevails at higher temperatures with longer reaction times sufficient for equilibration. The product ratio is determined by the difference in Gibbs free energies (ΔG°) between the products.

- Reversibility: A necessary condition for thermodynamic control is sufficient reversibility or a mechanism permitting equilibration between products.

The product distribution follows distinct mathematical relationships depending on the control mechanism:

- Under kinetic control: (\ln\left(\frac{[A]t}{[B]t}\right) = \ln\left(\frac{kA}{kB}\right) = -\frac{\Delta E_a}{RT})

- Under thermodynamic control: (\ln\left(\frac{[A]{\infty}}{[B]{\infty}}\right) = \ln K_{eq} = -\frac{\Delta G^{\circ}}{RT}) [13]

Visualization of Competing Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the energetic landscape for competing kinetic and thermodynamic pathways in crystal formation:

Diagram 1: Energy landscape for kinetic vs thermodynamic control

Nucleation and Crystal Growth in Inorganic Systems

Stages of Crystallization

Crystal formation from solution occurs through three distinct stages, each governed by thermodynamic and kinetic factors [14]:

- Nucleation: The initial formation of ordered aggregates that must reach a critical size to become stable and continue growing rather than re-dissolve.

- Growth: The deposition of material from solution onto the surfaces of stable crystal nuclei.

- End of Growth: Cessation of growth due to material depletion or surface poisoning by impurities or defects.

Thermodynamics of Nucleation

The energy barrier to nucleation (ΔGn) is described by: [ \Delta G_n = \left[-\frac{kT(4\pi r^3)}{V \ln \beta}\right] + 4\pi r^2\gamma ] where k is Boltzmann's constant, β is the degree of supersaturation, γ is the interfacial free energy between nucleus and solution, r is the effective radius of the crystal nucleus, and V is the molecular volume [14].

This equation contains two competing terms: a negative volume term (proportional to r³) representing the energy advantage from decreased system free energy, and a positive surface area term (proportional to r²) representing the energy required for surface deposition. The nucleation rate follows: [ Jn = Bs \exp\left(-\frac{\Delta G_n}{kT}\right) ] where Bs is a function of solubility and kinetic parameters related to diffusion coefficients [14].

Phase Diagram for Crystallization

A simplified phase diagram for crystallization illustrates the relationship between supersaturation and the crystallization process [14]:

Diagram 2: Crystallization phase diagram

The crystallization process begins with a saturated solution at equilibrium, where the chemical potential (μ) of species i is identical in solution and crystalline states: μicrys = μisol = μio + RT lnγi ci [14]. Supersaturation (μisol > μicrys) establishes the driving force for precipitation, which proceeds until equilibrium is re-established.

Monotropic and Enantiotropic Systems

Defining Polymorphic Relationships

In crystalline materials, polymorphs can exhibit distinct relationships classified as either monotropic or enantiotropic:

Monotropic Systems: One polymorph is thermodynamically stable across the entire temperature range below melting. Transition between forms is irreversible, and kinetic control typically dominates the formation of metastable polymorphs.

Enantiotropic Systems: Different polymorphs are stable within specific temperature ranges, with a transition point where stability reverses. These systems allow reversible transformations between polymorphs, making them susceptible to thermodynamic control under appropriate conditions.

Quantitative Analysis of Inorganic Crystal Chemical Space

The combinatorial space of multi-component inorganic compounds reveals the vast possibilities for polymorph formation. Recent research has enumerated binary, ternary, and quaternary element combinations to map inorganic crystal chemical space [15]:

Table 1: Compositional Space of Inorganic Compounds

| System | Total Unique Combinations | Standard (Allowed, Known) | Missing (Allowed, Unknown) | Interesting (Forbidden, Known) | Unlikely (Forbidden, Unknown) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binary (Að”´Bð”µ) | 225,879 | 3,627 (1.6%) | 9,837 (4.4%) | 6,354 (2.8%) | 206,061 (91.2%) |

| Ternary (Að”´Bð”µCð”¶) | 77,637,589 | 24,713 (0.03%) | 10,754,728 (13.9%) | 12,153 (0.01%) | 66,845,995 (86.1%) |

| Quaternary (Að”´Bð”µCð”¶Dð”·) | 16,902,534,325 | 16,455 (0.00%) | 2,909,418,527 (17.2%) | 962 (0.00%) | 13,993,098,381 (82.8%) |

Data sourced from combinatorial screening of the first 103 elements of the Periodic Table and their accessible oxidation states (421 species) with stoichiometric factors w,x,y,z < 7, labeled according to chemical filters and presence in the Materials Project database [15].

Chemical filters applied to distinguish plausible ("allowed") from implausible ("forbidden") inorganic stoichiometries include:

- Charge-neutrality: Based on sum of formal charges: wqA + xqB + yqC + zqD = 0

- Electronegativity balance: Requires that the most electronegative ion has the most negative charge (χanion - χcation > 0 using Pauling scale) [15]

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Controlling Crystallization Pathways

Different experimental parameters can be manipulated to direct crystallization toward kinetic or thermodynamic products:

Table 2: Experimental Conditions Favoring Kinetic vs Thermodynamic Control

| Parameter | Kinetic Control | Thermodynamic Control |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Low temperatures (slows equilibration) | Higher temperatures (accelerates equilibration) |

| Time | Short reaction times | Long reaction times |

| Supersaturation | High supersaturation | Moderate supersaturation near equilibrium |

| Nucleation | Rapid nucleation | Slow, controlled nucleation |

| Additives | Growth inhibitors for metastable forms | Catalysts for phase transformation |

| Agitation | Rapid mixing | Gentle or no agitation |

Research Reagent Solutions for Crystal Engineering

Table 3: Essential Materials for Controlled Crystallization Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Solvent Systems | Controls solubility and supersaturation | Mixed aqueous-organic solvents for modulating nucleation kinetics |

| Structure-Directing Agents | Templates specific crystal structures | Surfactants for mesoporous material synthesis |

| Dopants/Impurities | Modifies nucleation energy barriers | Heterovalent ions for defect-engineered crystallization |

| Seeds | Provides controlled nucleation sites | Microgravity-grown crystals as optimal templates for polymorph control [16] |

| Polymeric Stabilizers | Inhibits growth of specific crystal faces | Polyvinylpyrrolidone for morphology control |

| pH Modifiers | Controls speciation and supersaturation | Ammonia hydroxide for metal oxide precipitation |

Case Study: CdS Nanomaterial Synthesis

Research on CdS nanomaterials demonstrates how thermodynamic and kinetic control can be manipulated to produce different crystalline forms. Through careful control of reaction conditions including temperature, precursor concentration, and surface ligands, researchers achieved predominantly cubic but anisotropic CdS structures, showing how kinetic control can produce morphologies that deviate from the thermodynamic equilibrium crystal habit [17].

Advanced Applications and Research Directions

Pharmaceutical Polymorph Control

The use of microgravity-grown crystals as seeds represents a cutting-edge approach to controlling polymorph formation in pharmaceuticals. Studies demonstrate that crystals grown in microgravity environments provide optimal templates for seeding additional crystallization, effectively bypassing the stochastic nucleation phase that often leads to polymorphic mixtures [16].

Recent research has shown that microgravity-grown crystals can serve as effective seeds for multiple generations of the same polymorph formation for pharmaceutical compounds including carbamazepine and atorvastatin calcium. These crystals maintain their seeding efficacy for up to 10 generations of crystal growth, providing a robust method for controlling polymorphic outcome in industrial crystallization processes [16].

High-Throughput Screening of Polymorphic Space

The vast combinatorial space of inorganic compounds [15] necessitates high-throughput approaches to mapping polymorphic stability. Automated screening platforms that systematically vary temperature, solvent composition, and supersaturation can efficiently delineate monotropic and enantiotropic relationships while identifying conditions that favor specific polymorphs.

In Situ Monitoring Techniques

Advanced characterization methods enable real-time monitoring of crystallization processes:

- Inline spectroscopy (Raman, ATR-FTIR) for polymorph identification during crystallization

- Process analytical technology (PAT) for tracking particle size and count

- Synchrotron X-ray diffraction for time-resolved crystal structure determination

The deliberate navigation of kinetic and thermodynamic control mechanisms provides researchers with powerful strategies for manipulating monotropic and enantiotropic systems in inorganic crystal formation. By understanding the fundamental nucleation and growth processes, applying appropriate experimental controls, and utilizing advanced characterization techniques, scientists can design crystallization processes that yield targeted polymorphic forms with optimized properties for pharmaceutical, electronic, and materials applications. The continued development of computational prediction methods combined with high-throughput experimental validation promises to further enhance our ability to control crystalline form in increasingly complex multi-component systems.

Pre-Nucleation Clusters and Two-Step Nucleation Mechanisms

The understanding of crystallization, a fundamental process in materials science, chemistry, and drug development, has undergone a significant paradigm shift. The long-established classical nucleation theory (CNT), derived in the 1930s, has faced challenges in explaining numerous crystallization phenomena observed in both biological and synthetic systems [18]. CNT posits that nucleation occurs through the stochastic formation of critical nuclei directly from basic monomers (atoms, ions, or molecules), with the nucleation barrier arising from competing bulk and surface energy terms [19]. This view assumes that nascent nuclei possess the same structure as the macroscopic bulk material and that interfacial tension values equate to those of macroscopic interfaces—the debated "capillary assumption" [18].

In contrast, non-classical nucleation theory recognizes pathways that diverge from these fundamental CNT assumptions. The pre-nucleation cluster (PNC) pathway represents a truly non-classical concept where solute species with "molecular" character exist in solution prior to nucleation [18]. Additionally, two-step nucleation mechanisms have been identified wherein disordered clusters or dense liquid phases form first, followed by structural reorganization into crystalline nuclei [19] [20]. These non-classical pathways provide a more nuanced framework for understanding nucleation phenomena that have proven difficult to rationalize within the classical paradigm, particularly in biomineralization, pharmaceutical crystallization, and advanced materials synthesis.

Theoretical Foundations

The Prenucleation Cluster Concept

Prenucleation clusters are stable solute species that exist in solution before the formation of crystalline nuclei. Unlike the transient, unstable clusters envisioned in CNT, stable PNCs represent distinct chemical entities with well-defined structures and properties [18]. In the calcium carbonate system, which has been physicochemically best analyzed with respect to PNCs, these clusters demonstrate stability that would be unexpected according to classical notions [18].

The formation of stable PNCs challenges two fundamental assumptions of CNT [18]:

- No distinct phase interface exists between the clusters and the solution

- Cluster structures do not resemble the macroscopic bulk crystal structure

The driving force for PNC formation arises from a balance between favorable interface energy and unfavorable bulk energy, essentially inverting the classical perspective [19]. This explains why PNCs can represent thermodynamically favored species with respect to dispersed solutes in solutions below the saturation limit.

Thermodynamics of Two-Step Nucleation

Two-step nucleation mechanisms involve the initial formation of a disordered intermediate followed by structural reorganization into a crystalline phase. The thermodynamic rationale for such pathways lies in following the pathway encompassing the lowest nucleation barrier [19].

Table 1: Comparison of Nucleation Mechanisms

| Feature | Classical Nucleation | Two-Step Nucleation |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Step | Stochastic monomer addition | Formation of disordered clusters or dense phases |

| Intermediate Species | Unstable critical nuclei | Stable pre-nucleation clusters or amorphous precursors |

| Structural Evolution | Direct formation of crystal structure | Structural reorganization within clusters |

| Dominant Energy Terms | Surface tension vs. bulk energy | Competition between multiple phases with different surface/bulk energetics |

| Polymorph Selection | Determined by critical nucleus stability | Influenced by stability of intermediate phases |

In this framework, a disordered cluster phase may possess a more favorable surface tension, making it thermodynamically preferred for small aggregates, while the crystalline structure becomes stable only for larger aggregates due to more favorable bulk packing [19]. This size-dependent phase stability drives the multi-step nucleation pathway, with the transformation between stages potentially subject to significant energy barriers that can influence polymorph selection and crystal quality.

Experimental Evidence and Methodologies

Advanced Characterization Techniques

The identification and study of pre-nucleation clusters and multi-step nucleation mechanisms has been enabled by sophisticated experimental approaches that provide real-time monitoring and characterization at relevant length and time scales.

Table 2: Key Experimental Techniques for Studying Non-Classical Nucleation

| Technique | Application | Key Insights |

|---|---|---|

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Thermodynamics of PNC formation | Revealed endothermic nature of PNC formation in calcium carbonate [18] |

| Advanced Microscopy (AFM, TEM) | Real-time observation of nucleation | Direct visualization of multi-step pathways and intermediate species [21] |

| In Situ Spectroscopy (NMR, FTIR) | Monitoring solution chemistry | Identification of molecular-scale species prior to crystallization [22] |

| Fast Scanning Chip Calorimetry (FSC) | Crystallization kinetics | Revealed temperature-dependent nucleation mechanisms in polymers [22] |

A notable example comes from real-time in situ atomic force microscopy (AFM) studies of amphiphilic organic semiconductors, which revealed a sophisticated five-step growth trajectory [21]:

- Droplet flattening - Liquid-like droplets spread on surfaces

- Film coalescence - Nanoplates merge into amorphous base films

- Spinodal decomposition - Phase separation into thick and thin islands

- Ostwald ripening - Mass transport from small to large clusters

- Self-reorganized layer growth - Crystallized film formation

This complex pathway bridges sequential classical and non-classical mechanisms and demonstrates the importance of long-range cluster migration in organic crystal formation [21].

Computational and Modeling Approaches

Computer simulation has proven indispensable for understanding nucleation at the molecular scale, providing insights difficult to obtain experimentally [18]. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with enhanced sampling techniques, such as well-tempered metadynamics, have enabled the calculation of free-energy profiles associated with phase transitions [20].

In urea nucleation from aqueous solution, MD simulations revealed that nucleation is preceded by large concentration fluctuations, indicating a predominant two-step process where embryonic crystal nuclei emerge from dense, disordered urea clusters [20]. These simulations also identified competition between polymorphs in the early nucleation stages, highlighting how computational approaches can illuminate the complex structural evolution during nucleation.

Advanced sampling methods are particularly valuable for studying nucleation as they overcome the timescale limitations of conventional molecular dynamics. Techniques such as metadynamics accelerate configurational sampling while allowing free energies to be evaluated and transition rates to be computed [20].

Research Reagent Solutions and Methodologies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Non-Classical Nucleation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium Carbonate Systems | Model system for PNC studies | Fundamental studies of non-classical nucleation pathways [18] |

| Amphiphilic Organic Semiconductors (CnP-BTBT) | Biomimetic self-assembly studies | Real-time observation of multi-step crystallization [21] |

| Microreactors & Continuous Flow Systems | Process intensification | Enhanced nucleation control through improved mixing and heat transfer [22] |

| Ionic Liquids (PILs, SILs) | Tailored crystallization media | Potential-driven growth of metal crystals with controlled morphology [22] |

| Membrane Crystallization (MCr) Systems | Controlled supersaturation | Simultaneous solution separation and component solidification [22] |

Applications and Implications

Pharmaceutical and Materials Science

The understanding of non-classical nucleation pathways has significant implications for pharmaceutical development and materials design. Controlling crystal polymorphism is crucial in pharmaceutical formulation as different polymorphs can exhibit varying bioavailability, stability, and processing characteristics [22]. The recognition that polymorph selection can occur during early nucleation stages, influenced by the stability of pre-nucleation clusters or intermediate phases, provides new strategies for controlling crystal form.

In materials science, non-classical nucleation mechanisms enable the design of materials with tailored properties. For example, the formation of mesocrystals—superstructures of aligned nanocrystals—through particle-mediated non-classical pathways can yield materials with exceptional mechanical properties reminiscent of biominerals [18]. Similarly, understanding the multi-step nucleation of organic semiconductors has facilitated the development of high-performance optoelectronic materials through molecular and crystal engineering [21].

Geological and Biomineralization Processes

Non-classical nucleation concepts have resolved fundamental questions in geophysics and biomineralization. The "inner core nucleation paradox"—whereby the direct nucleation of stable hexagonal close-packed (hcp) iron required an unrealistic degree of undercooling under Earth's core conditions—has been resolved through the identification of a two-step nucleation mechanism [23]. Molecular dynamics simulations demonstrate that metastable body-centered cubic (bcc) iron nucleates more readily than the hcp phase, with subsequent transformation to the stable polymorph [23]. This mechanism reduces the required undercooling and explains the feasibility of inner core formation.

In biomineralization, non-classical pathways involving pre-nucleation clusters and amorphous precursors are now recognized as fundamental to the formation of complex biological minerals with sophisticated hierarchical architectures [18]. These pathways provide organisms with greater control over mineralization, enabling the production of materials with optimized mechanical properties and morphological precision.

Visualization of Key Concepts

Two-Step Nucleation Mechanism

Diagram 1: Two-step nucleation pathway involving pre-nucleation clusters

Experimental Workflow for Non-Classical Nucleation Studies

Diagram 2: Integrated experimental workflow for studying non-classical nucleation

The recognition of pre-nucleation clusters and two-step nucleation mechanisms represents a fundamental advancement in our understanding of crystallization processes. These non-classical pathways provide a more comprehensive framework for explaining crystallization phenomena across diverse systems—from biomineralization to pharmaceutical polymorphism. The integration of advanced experimental techniques with sophisticated computational models continues to reveal the complex molecular-scale processes underlying nucleation, enabling increasingly rational design of crystalline materials with tailored properties and functionalities. As research in this field progresses, the continued refinement of non-classical nucleation theory promises to enhance our control over crystallization processes in both natural and technological contexts.

The solid form of an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) is a critical determinant of its performance and processability. While the same chemical molecule can exist in multiple solid arrangements, or crystal forms, each form possesses distinct physicochemical properties that directly impact drug product development. These forms include polymorphs (different crystal structures of the same molecule), hydrates/solvates (crystal structures incorporating solvent molecules), and co-crystals (crystalline complexes with co-formers) [24]. For researchers working in nucleation and growth within inorganic crystal formation, understanding these principles is fundamental, as the same thermodynamic and kinetic rules govern the formation and stability of all crystalline materials, from simple ionic solids to complex pharmaceutical compounds.

This technical guide examines how crystal form influences key properties including solubility, stability, and ultimately, bioavailability. We frame this discussion within the context of crystallization fundamentals, providing experimental and computational methodologies for solid-form selection and control—a crucial process for ensuring drug efficacy and quality.

Crystal Forms and Their Fundamental Properties

Classification of Crystal Forms

A single API can exist in several solid forms, each with unique internal structures and external morphologies:

- Polymorphs: These are different crystalline arrangements of the same molecule. A classic example is ROY (5-methyl-2-[(2-nitrophenyl)amino]-3-thiophene carbonitrile), which has multiple polymorphs distinguished by their red, orange, and yellow colors [24]. The energy differences between polymorphs are typically small (a few kJ/mol), making their relative stability highly dependent on temperature and pressure [24].

- Hydrates and Solvates: These crystalline forms incorporate solvent molecules (specifically water in hydrates) into their lattice structure. The formation of hydrates is particularly relevant given the ubiquity of water in manufacturing and storage environments [24] [25].

- Co-crystals: These are crystalline materials comprising two or more different molecules, typically the API and a pharmaceutically acceptable co-former, in the same crystal lattice. Co-crystals can be engineered to improve poor physicochemical properties of an API [24].

- Amorphous Solids: These lack long-range molecular order and represent a distinct category from crystalline forms. They typically exhibit higher energy and solubility but also a greater tendency to crystallize over time [26].

Thermodynamic and Kinetic Relationships

The stability relationships between crystal forms are governed by thermodynamics and kinetics, concepts familiar from nucleation and growth research.

- Monotropy: In a monotropic system, one polymorph is thermodynamically stable across all temperatures below the melting point. The metastable form can irreversibly transform to the stable form, with the transformation often mediated by the liquid or vapor phase [24]. This presents a significant risk in pharmaceutical development, as an unexpected conversion can occur during manufacturing or storage.

- Enantiotropy: In an enantiotropic system, the relative stability of two polymorphs reverses at a specific transition temperature below their melting points. At this temperature, the free energies of the two forms are equal [24]. Understanding this relationship is crucial for processes involving temperature changes.

The following diagram illustrates the thermodynamic and kinetic decision-making process for crystal form selection and control, integrating both experimental and computational approaches.

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for crystal form selection, combining computational and experimental approaches.

Impact on Physicochemical Properties

Solubility and Dissolution Rate

The crystal form directly affects a drug's solubility and dissolution rate—often the rate-limiting step for absorption. These properties are governed by the crystal lattice energy: more stable polymorphs with higher lattice energy typically exhibit lower solubility, while metastable forms demonstrate higher solubility [24]. This presents a formulation strategy: utilize a metastable form for enhanced solubility while managing the risk of conversion to the stable form.

Table 1: Property Differences Between Crystal Forms

| Property | Impact of Crystal Form | Typical Variation |

|---|---|---|

| Solubility | Determined by crystal lattice energy; more stable forms have lower solubility [24]. | Can differ by several-fold between forms [27]. |

| Dissolution Rate | Influenced by solubility and crystal habit/surface area [24]. | Critical for bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs. |

| Melting Point | Reflects the stability of the crystal lattice [24]. | Varies between polymorphs; used for identification. |

| Hygroscopicity | Affects stability; hydrates form at critical relative humidity [25]. | Can lead to phase transformations during storage. |

| Chemical Stability | Molecular arrangement affects susceptibility to degradation [24]. | Some forms may be more prone to oxidation or hydrolysis. |

| Mechanical Properties | Hardness and compaction behavior vary [24]. | Affects manufacturability (e.g., tableting). |

For ionic solids, solubility is further influenced by lattice energy, which depends on ion sizes and charges. Smaller ions and higher charges lead to greater lattice energies and lower solubility, though the relationship is complex due to hydration energetics [28].

Physical and Chemical Stability

The relative stability of crystal forms determines a drug's shelf life and behavior under various environmental conditions. A key concern is the potential for phase transformation during manufacturing (e.g., wet granulation, milling) or storage. For instance, a metastable polymorph might convert to a stable form, or an anhydrate might form a hydrate under high humidity conditions [24] [25]. These transformations can alter solubility, dissolution, and bioavailability. As noted by Bernstein, the most stable form of a compound may not yet have been discovered, presenting a perpetual risk in drug development [24].

Bioavailability Implications

For poorly soluble (Biopharmaceutics Classification System Class II) drugs, dissolution is the rate-limiting step for absorption. The choice of crystal form can therefore directly determine a drug's in vivo performance. Even small differences in solubility and dissolution rate can lead to clinically significant differences in bioavailability [27]. This is a primary reason regulatory agencies require thorough solid-state characterization and control of the crystal form throughout the drug lifecycle [24].

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Crystal Form Screening Protocols

Comprehensive solid-form screening is a standard industrial practice to map the solid-form landscape and identify the most suitable form for development.

Protocol 1: Polymorph and Hydrate Screening

- Crystallization from Various Solvents: Use a range of solvents with different polarities and properties (e.g., water, alcohols, acetonitrile, toluene) [24].

- Varying Conditions: Employ multiple techniques (e.g., evaporation, cooling, anti-solvent addition, slurrying) at different temperatures [24].

- Stress Testing: Expose solid forms to elevated temperature and humidity (e.g., 40°C/75% RH) to assess stability and detect potential transformations [24].

- Analysis: Characterize all resulting solids using techniques like X-ray Powder Diffraction (XRPD), Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC), and Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) to identify distinct forms [24].

Protocol 2: Co-crystal Screening

- Co-former Selection: Choose pharmaceutically acceptable co-formers with functional groups capable of forming hydrogen bonds with the API [24].

- Preparation Methods: Use grinding (neat or liquid-assisted), solvent evaporation, or slurry crystallization [24].

- Characterization: Confirm co-crystal formation with single-crystal X-ray diffraction and spectroscopic methods like Solid-State NMR (ssNMR) [24].

Computational Prediction of Crystal Form Stability

Modern computational methods have dramatically advanced the ability to predict crystal stability and behavior under real-world conditions.

Protocol 3: Free Energy Calculation and Crystal Structure Prediction (CSP)

- Generate Putative Crystal Structures: Use computational sampling to generate a wide range of plausible crystal packings for the API [25].

- Calculate Relative Free Energies: Employ a composite approach (e.g., the TRHu(ST) method) that combines:

- Incorporate Environmental Factors: Place anhydrates and hydrates of different stoichiometries on the same energy landscape as a function of temperature and relative humidity by calculating the chemical potential of water vapor [25].

- Quantify Errors: Assign standard errors (e.g., 1–2 kJ molâ»Â¹ for industrially relevant compounds) to the computed free energies using established error propagation models [25].

These methods can accurately predict key transition points, such as the relative humidity at which a hydrate becomes more stable than an anhydrate, with experimental agreement within a factor of 1.7 on average [25].

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Crystal Form Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Polymorph Screening Kit | A standardized set of solvents with diverse properties (polar, non-polar, protic, aprotic) for experimental crystallization [24]. |

| Pharmaceutically Acceptable Co-formers | A library of molecules (e.g., carboxylic acids, amides) for co-crystal screening to modify API properties [24]. |

| Hydrate Formation Chambers | Controlled environment chambers to precisely regulate temperature and relative humidity for studying hydrate-anhydrate transitions [25]. |

| Computational Chemistry Software | Software packages for Crystal Structure Prediction (CSP) and free-energy calculation (e.g., using PBE0+MBD+Fvib approaches) [25]. |

| Reference Energetic Compounds | A benchmark set of compounds with reliably known solid-solid free-energy differences for validating computational methods [25]. |

Case Studies and Data Analysis

Pharmaceutical Case Studies

Case Study 1: Radiprodil Radiprodil is a pharmaceutical compound investigated for neurological conditions. Computational CSP was used to map its crystal-energy landscape at various temperatures and relative humidities. The study successfully predicted the stability relationships between an anhydrate, a monohydrate, and a dihydrate form. The experimentally observed forms corresponded to the most stable predicted crystal structures for each stoichiometry, demonstrating the power of modern in silico methods to guide form selection and identify hydrate risks [25].

Case Study 2: Carbamazepine Carbamazepine, an anticonvulsant drug, exists in multiple polymorphs and a dihydrate. Different polymorphs exhibit different dissolution rates and bioavailability, making solid-form control essential for product performance [27]. Furthermore, molecular simulation studies on carbamazepine suggest a two-step nucleation process beginning with amorphous aggregates, with the thermodynamic stability of polymorphs depending on crystal size. This highlights the complex interplay between nucleation kinetics and crystal form stability [29].

Quantitative Stability and Solubility Data

Table 3: Experimental vs. Computed Free-Energy Differences

| Compound Pair | Experimental ΔG (kJ molâ»Â¹) | Computed ΔG (kJ molâ»Â¹) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymorph A / Polymorph B | 0.00 (at Ttrans) | +0.5 | [25] |

| Anhydrate / Monohydrate | 0.00 (at RHtrans) | -1.2 | [25] |

| Form II / Form III (Carbamazepine) | - | Size-dependent stability inversion predicted | [29] |

Advanced computational methods can predict hydrate-anhydrate transition relative humidities within a factor of 1.7 of experimental values on average. Without empirical correction, agreement is still within a factor of 2.4, proving the fundamental robustness of the approach [25].

The impact of crystal form on the physicochemical properties of active ingredients is a fundamental consideration in drug development that rests on the principles of nucleation and crystal growth. The selection of an optimal crystal form—whether a polymorph, hydrate, or co-crystal—directly dictates critical performance attributes including solubility, stability, and ultimately, therapeutic efficacy. A proactive strategy that integrates robust experimental screening with predictive computational modeling is essential for de-risking pharmaceutical development. As computational methods continue to advance in accuracy and accessibility, the ability to predict and control crystal form stability under real-world conditions will become increasingly integral to the efficient design of robust, effective drug products.

Advanced Methods and Applications for Controlling Crystallization

The study of nucleation and growth in inorganic crystal formation provides a powerful conceptual and technical framework for understanding complex systems across scientific disciplines. The transition from a disordered to an ordered state, governed by the principles of supersaturation, nucleation, and crystal growth, offers profound parallels to the development of addictive disorders, where maladaptive neural pathways become entrenched through reinforcement. Computational modeling serves as the critical bridge connecting these seemingly disparate fields, enabling researchers to simulate processes from atomic-scale interactions in crystal lattices to the neurocircuitry of addiction. This whitepaper explores how predictive computational tools, originally developed for materials science, are now revolutionizing our understanding and treatment of substance use disorders through projects like the ADDICT model (AI-Driven Discovery and Intervention for Compulsive Triggers).

The core connection lies in the shared focus on phase transitions—whether in inorganic systems forming crystalline structures or neural circuits transitioning from controlled use to compulsive addiction. Molecular dynamics simulations track atomic interactions during crystal nucleation, while analogous computational approaches map neurobiological changes as addiction progresses. The ADDICT framework represents the clinical application of these principles, using generative artificial intelligence to predict individual vulnerability to opioid addiction by identifying patterns in complex datasets mirroring how scientists predict crystal formation pathways from molecular interactions.

Theoretical Foundations: Nucleation and Growth Principles

Classical Nucleation Theory and Analogous Processes

Crystal nucleation begins in a supersaturated solution where molecular aggregates form nuclei that develop into macroscopic crystals through growth processes [22]. This phase separation mirrors the transition from occasional drug use to established addiction, where reinforcing experiences create a psychological "supersaturation" that precipitates pathological patterns.

Supersaturation, the metastable state driving crystallization, occurs through several mechanisms:

- Solvent Evaporation: Increasing concentration by evaporating solvent until crystallization begins [30]

- Temperature Gradient: Utilizing differential solubility between hot and cold solvents [30]

- Anti-Solvent Addition: Using binary solvent systems where the compound is soluble in only one component [30]

In addiction development, analogous "supersaturation" mechanisms include stress-induced vulnerability, repeated drug exposure increasing reward sensitivity, and environmental cues that precipitate compulsive use. The nucleation stage in both systems represents the critical transition point where system behavior fundamentally changes.

Crystal Growth Mechanisms and Neural Pathway Formation

Once nucleation occurs, crystal growth proceeds through different mechanisms:

- Diffusion-controlled growth: Continues when concentration falls below critical nucleation threshold [22]

- Surface-process-controlled growth: Occurs when diffusion from bulk to growth surface is sufficiently rapid [22]

Similarly, addiction progresses through defined stages: binge/intoxication establishes drug-reward associations, withdrawal/negative affect creates avoidance motivations, and preoccupation/anticipation cements compulsive drug-seeking [31]. These stages parallel crystal growth mechanisms where initial nucleation is followed by progressive structural consolidation.

Table 1: Comparison of Crystallization Stages and Addiction Phases

| Crystallization Stage | Addiction Phase | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Supersaturation | Vulnerability | System primed for state transition |

| Nucleation | Initial Drug Use | Critical transition point |

| Crystal Growth | Addiction Progression | Reinforcement of new structure/pathways |

| Defect Formation | Compulsive Behavior | Entrenched maladaptive patterns |

Computational Methodologies

Molecular Dynamics Simulations