Mastering Crystal Morphology: An Advanced Guide to Antisolvent Treatment for Pharmaceutical Scientists

This comprehensive article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with an in-depth exploration of antisolvent crystallization for precise crystal morphology control.

Mastering Crystal Morphology: An Advanced Guide to Antisolvent Treatment for Pharmaceutical Scientists

Abstract

This comprehensive article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with an in-depth exploration of antisolvent crystallization for precise crystal morphology control. Covering foundational thermodynamic principles to advanced optimization strategies, we examine how antisolvent parameters dictate critical product attributes including particle size distribution, polymorphism, and final crystal habit. The content synthesizes current scientific understanding with practical methodological applications across pharmaceutical development, focusing on enhancing drug bioavailability, stability, and process efficiency. Through systematic analysis of parameter effects, troubleshooting guidance, and validation methodologies, this resource serves as an essential reference for implementing antisolvent techniques in pharmaceutical formulation and process development.

The Science of Crystal Engineering: Thermodynamic Principles of Antisolvent Crystallization

Supersaturation represents the fundamental driving force in crystallization processes, defined as the state where a solution contains more dissolved solute than it would under equilibrium saturation conditions [1]. In the context of antisolvent crystallization for tailoring crystal morphology, precise supersaturation control is paramount. It governs the kinetic processes of nucleation and crystal growth, which directly determine final crystal properties including size distribution, purity, and most critically, morphology [1] [2]. For pharmaceutical development, where crystal morphology affects critical product characteristics such as bulk density, mechanical strength, wettability, filtration, and drying performance, mastering supersaturation control is an essential scientific and industrial capability [2].

Theoretical Foundation

Thermodynamic Definition

The thermodynamic driving force for crystallization originates from the difference between the chemical potential of the solute in a supersaturated solution and its chemical potential at equilibrium. The rigorous, dimensionless expression for supersaturation is derived as follows [1]:

Where:

σ= dimensionless supersaturationa= activity of the solute in the supersaturated solutiona_sat= activity of the solute at saturationx= mole fraction of the solute in the supersaturated solutionx_sat= mole fraction of the solute at saturation (solubility)γ= activity coefficient of the solute in the supersaturated solutionγ_sat= activity coefficient of the solute at saturation

This mole fraction and activity coefficient-dependent (MFAD) expression provides the most accurate representation of the true crystallization driving force [1].

Simplified Expressions and Their Limitations

Several simplified supersaturation expressions are commonly employed, each with specific limitations and appropriate application domains, particularly for antisolvent crystallization systems where non-ideality is significant [1].

Table 1: Common Supersaturation Expressions and Their Applicability

| Expression | Formula | Key Assumptions | Limitations & Applicability |

|---|---|---|---|

| MFAD (Recommended) | σ = ln(x·γ / x_sat·γ_sat) |

None | Requires activity coefficient data; Most accurate for antisolvent crystallization [1] |

| Concentration Ratio | σ = ln(C / C_sat) |

Solution density and average molecular weight are constant; Avoids mole fraction conversion | Flawed when solute concentration is high or differs significantly from solvent properties [1] |

| Ideal System | σ = ln(x / x_sat) |

Ideal solution behavior (γ = γ_sat = 1) |

Acceptable near equilibrium where activity coefficient ratio ≈1; Poor in highly supersaturated or non-ideal systems [1] |

| Dimensionless Concentration Difference | σ = (C - C_sat) / C_sat |

Very low supersaturation (σ ≪ 1) and ideal system |

Poor approximation at σ > 1; Should not be used instead of more rigorous expressions [1] |

For antisolvent crystallization, the ratio of activity coefficients (γ/γ_sat) frequently deviates substantially from unity, even at relatively low supersaturation levels. Making unnecessary simplifications can introduce errors exceeding 190% in the estimation of crystallization driving force, subsequently causing nearly an order of magnitude error in regressed nucleation and growth kinetic parameters [1].

Quantification and Estimation Methods

Step-by-Step MFAD Supersaturation Estimation

The following methodology enables estimation of the MFAD supersaturation in ternary (solvent-antisolvent-solute) systems, requiring only solubility data and thermal property data from a single differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) experiment [1].

Step 1: Solubility Data Acquisition

- Determine the mole fraction solubility (

x_sat) of the solute across the relevant temperature and solvent composition ranges. - For antisolvent crystallization, establish solubility as a function of antisolvent/ solvent ratio at constant temperature.

Step 2: Thermal Property Measurement

- Using DSC, measure the melting point (

T_m) and enthalpy of fusion (ΔH_fus) of the solute crystal form of interest. - These parameters approximate the triple point temperature and enthalpy change, respectively.

Step 3: Activity Coefficient at Saturation Calculation

- Apply the generalized solubility equation to calculate

γ_satat each saturation condition. Using the approximationΔC_p = ΔS_fus = ΔH_fus / T_m, the equation simplifies to:

- Solve for

γ_satat each experimental saturation point (T,x_sat).

Step 4: Activity Coefficient in Supersaturated Solution Estimation

- Estimate the activity coefficient in the supersaturated solution (

γ) by assuming it equals the activity coefficient in a saturated solution at the same solvent composition and temperature. - This leverages the principle that activity coefficient is primarily composition-dependent rather than supersaturation-dependent.

Step 5: Supersaturation Calculation

- With

x(mole fraction in supersaturated solution from concentration measurement),x_sat,γ, andγ_sat, compute the MFAD supersaturation:σ = ln(x·γ / x_sat·γ_sat).

Key Assumptions and Error Propagation

This methodology relies on several critical assumptions [1]:

- Pressure has a negligible effect on solubility.

- The solute exhibits negligible vapor pressure in solid and subcooled liquid states.

- Triple point temperature and enthalpy are approximated by melting point and enthalpy of fusion.

- The differential heat capacity between solid and melt (

ΔC_p) is approximated by the entropy of fusion.

While supersaturation estimations are less sensitive to errors in the heat capacity term than ideal solubility predictions, significant inaccuracies in ΔC_p can still propagate into the final supersaturation value. A detailed error analysis for specific compound systems is recommended.

Experimental Protocols for Supersaturation Control in Antisolvent Crystallization

Protocol 1: Membrane Distillation Crystallization (MDC) for Supersaturation Control

This protocol utilizes membrane area to modulate supersaturation, effectively decoupling nucleation and growth mechanisms without introducing changes to mass and heat transfer within the boundary layer [3].

Materials

- Crystallizer Vessel: Jacketed glass crystallizer with temperature control (±0.1°C)

- Membrane Module: Hydrophobic microporous membrane with defined active area

- Pumping System: Peristaltic pumps for feed and antisolvent addition

- Analytical Instrumentation: In-line particle imaging probe (e.g., Mettler FBRM, PVM) and concentration monitoring (e.g., ATR-FTIR)

- Temperature Control Unit: Circulating bath for precise crystallizer temperature regulation

- Filtration System: In-line filter for crystal retention

Procedure

- Initial Solution Preparation: Prepare a saturated solution of the API in the primary solvent at the process temperature. Filter through a 0.45 µm filter to remove any undissolved impurities or dust.

System Setup and Stabilization:

- Fill the crystallizer with a known volume of the saturated solution.

- Initiate agitation at a constant speed (e.g., 300 rpm).

- Stabilize the system at the target operating temperature.

Supersaturation Generation via MDC:

- Initiate the membrane distillation process by applying a vapor pressure gradient across the membrane.

- Systematically vary the effective membrane area to control the solvent removal rate, thereby directly adjusting the supersaturation generation rate.

- Monitor solution concentration in real-time using ATR-FTIR.

Induction and Crystal Growth:

- Record the induction time (onset of nucleation) via a sharp decrease in concentration and corresponding detection of particles by in-line probes.

- Following nucleation, maintain a constant supersaturation rate by modulating the membrane area.

- Utilize in-line filtration to retain crystals within the crystallizer, reducing membrane scaling and enabling longer crystal hold-up times.

Termination and Analysis:

- Once the target crystal size distribution is achieved, stop the process.

- Filter, wash (with antisolvent), and dry the product.

- Characterize crystal morphology using microscopy, and determine crystal size distribution (CSD) via sieve analysis or laser diffraction.

Key Application Note: Increasing the concentration rate shortens induction time and raises supersaturation at induction, broadening the metastable zone width. This favors a homogeneous primary nucleation pathway. Modulating supersaturation via membrane area repositions the system within specific metastable zone regions to favor crystal growth over primary nucleation [3].

Protocol 2: Calorimetry-Based Supersaturation Monitoring for Kinetic Studies

This protocol employs reaction calorimetry to monitor the heat flow associated with crystallization, enabling indirect estimation of supersaturation and its link to morphology development [4].

Materials

- Calorimeter: Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) or reaction calorimeter (RC1e)

- Solvent Delivery System: Precision syringe pump for controlled antisolvent addition

- Data Acquisition Software: For recording heat flow and temperature data

Procedure

- Calorimeter Calibration: Perform electrical and heat capacity calibration of the calorimeter according to manufacturer specifications.

Baseline Establishment:

- Load a known mass of saturated API solution into the calorimeter vessel.

- Achieve thermal equilibrium at the process temperature.

- Record a stable thermal baseline.

Antisolvent Addition and Data Acquisition:

- Initiate controlled addition of antisolvent at a constant rate using the syringe pump.

- Record the heat flow signal (μW) throughout the addition and subsequent crystallization process.

- The heat flow profile is directly proportional to the crystallization rate (

dX/dt).

Supersaturation Profile Calculation:

- Integrate the heat flow signal over time to determine the cumulative heat released and the extent of crystallization (

X). - Relate the crystallization rate to the supersaturation driving force using an appropriate kinetic model (e.g.,

dX/dt = k σ^n). - Back-calculate the instantaneous supersaturation (

σ) profile throughout the process.

- Integrate the heat flow signal over time to determine the cumulative heat released and the extent of crystallization (

Morphology Prediction:

- Utilize the obtained supersaturation profile and kinetic parameters as input for numerical morphology simulation tools.

- Apply probabilistic numerical simulation methods based on random nucleation and subsequent growth theories to predict spherulitic morphology, nucleus density, and average crystal size from the conversion curve [4].

Key Application Note: This method is particularly valuable for linking process conditions to morphological outcomes. The simulation can differentiate between instantaneous and continuous nucleation mechanisms, which is critical for predicting final crystal size distribution and morphology [4].

Visualization of Supersaturation in Crystallization

The following diagram illustrates the thermodynamic relationship of supersaturation creation and its pivotal role in driving the crystallization mechanisms that determine final crystal morphology.

Diagram Title: Supersaturation Role in Crystallization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Antisolvent Crystallization Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrophobic Microporous Membrane | Generates supersaturation by selective solvent removal in MDC [3] | Pore size (0.1 - 0.45 µm); Chemical resistance to solvent/antisolvent system; High vapor permeability |

| In-line Particle Analyzer (e.g., FBRM, PVM) | Real-time monitoring of particle count, size, and shape evolution [5] [2] | Probe compatibility with solvent system; Calibration for chord length distribution; Sensitivity for detecting nucleation onset |

| ATR-FTIR Probe | Real-time concentration monitoring for supersaturation calculation [1] | Diamond ATR crystal for chemical resistance; Calibration model for solute concentration in solvent mixture; |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Measurement of thermal properties (Tm, ΔHfus) for activity coefficient estimation [1] | High purity calibration standards; Hermetically sealed pans to prevent solvent loss; Appropriate heating rate for accurate ΔHfus |

| Nucleating Agents (e.g., NA-21E, NX-8000) | Modify nucleation kinetics and crystal morphology [4] | Compatibility with API and solvent system; Concentration optimization required; Potential impact on product purity |

| Polypropylene Homopolymers | Model materials for methodology development and validation [4] | Well-characterized crystallization behavior; Different grades available (varying MFR) for studying process effects |

| Cimidahurinine | Cimidahurinine, CAS:142542-89-0, MF:C14H20O8, MW:316.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Nordeoxycholic acid | Nor-Desoxycholic Acid (NorUDCA) |

Accurate understanding and control of supersaturation is not merely an academic exercise but a fundamental requirement for successfully tailoring crystal morphology through antisolvent crystallization. The mole fraction and activity coefficient-dependent (MFAD) expression provides the most reliable estimation of the true thermodynamic driving force, especially in non-ideal pharmaceutical systems where simplified approaches can introduce substantial errors. By integrating rigorous supersaturation estimation with advanced control strategies like membrane distillation crystallization and calorimetric monitoring, researchers can systematically navigate the metastable zone to decouple and regulate nucleation and growth mechanisms. This precise control enables the production of crystals with targeted morphologies, directly impacting critical pharmaceutical product qualities and downstream process efficiency.

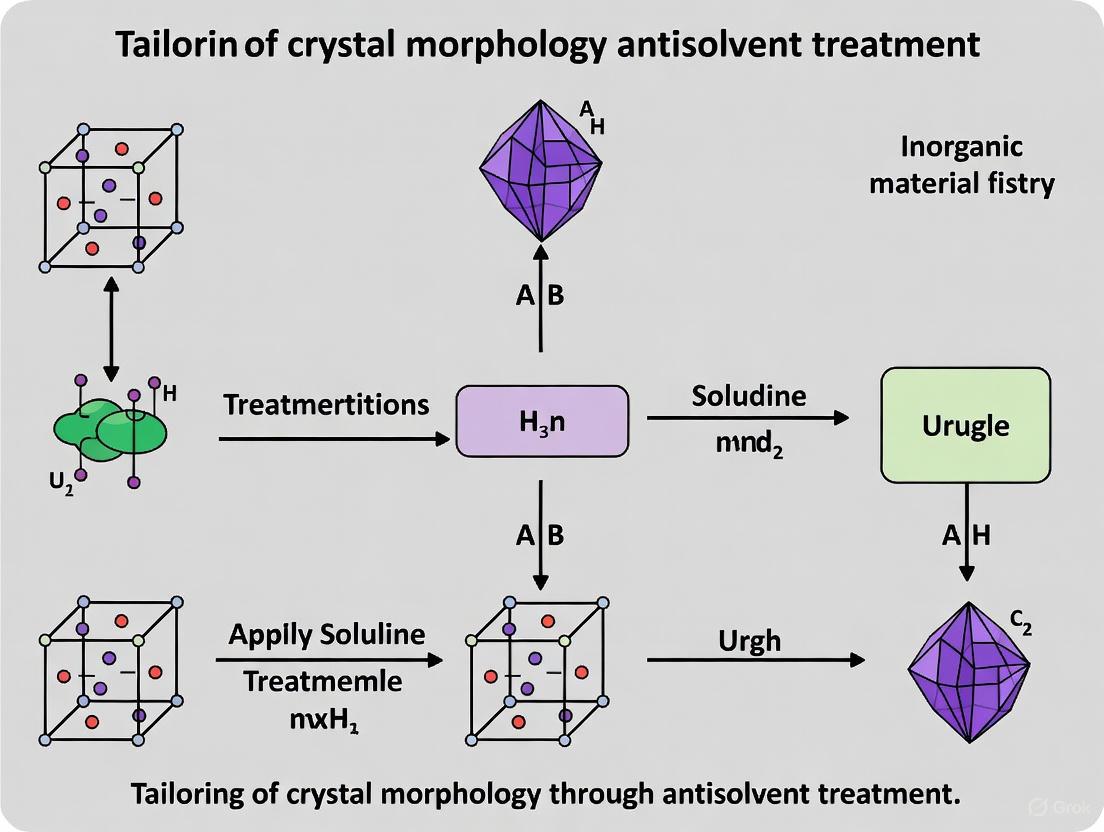

In the pharmaceutical industry, controlling the crystal morphology of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) is a critical aspect of product development. Crystal habit directly influences key pharmaceutical properties, including filtration, flowability, compressibility, and dissolution performance [6]. Among various crystallization techniques, antisolvent crystallization represents a powerful approach for manipulating nucleation and growth kinetics to achieve desired crystal morphologies.

This Application Note outlines detailed protocols for investigating the two-step process of nucleation and crystal growth kinetics within the context of antisolvent crystallization. By systematically controlling process parameters, researchers can tailor crystal morphology to overcome manufacturing challenges and optimize drug product performance. The methodologies presented herein are framed within broader research on tailoring crystal morphology with antisolvent treatment, providing scientists with practical tools for API development.

Theoretical Background

The Fundamentals of Antisolvent Crystallization

The principle behind antisolvent precipitation relies on the differential solubility of a compound in miscible solvents. The process begins by dissolving the drug in a "good" solvent, then rapidly mixing this solution with an "antisolvent" where the compound has limited solubility [7]. This rapid diffusion creates a high supersaturation ratio (β), defined as the ratio between the compound concentration in the solvent-antisolvent mixture (C₀) and the compound's equilibrium solubility (C*) at given conditions [7]:

β = C₀/C*

Supersaturation serves as the driving force for the crystallization process, which occurs through three primary stages: (1) nucleation, (2) particle growth, and (3) agglomeration [7]. According to classical nucleation theory, the initial step involves the spontaneous assembly of molecules into embryos that must overcome a critical energy barrier (ΔG*) to form stable nuclei [7]. This energy barrier and the subsequent nucleation rate (J) are highly dependent on the degree of supersaturation.

Spherulitic Growth in Pharmaceutical Crystals

Beyond traditional crystallization mechanisms, some systems exhibit spherulitic growth patterns where crystalline structures grow radially from a central point, forming spherical particles. Recent research on salbutamol sulfate has demonstrated that this growth pattern can be achieved through antisolvent crystallization, where sheaves of plate-like crystals gradually branch into fully developed spherulites [8]. This morphology offers significant advantages over needle-shaped crystals, which typically show poor flowability and challenging powder properties [8] [6].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential materials for antisolvent crystallization studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Salbutamol Sulfate (purity >99%) | Model API for crystallization studies [8] | Selective β₂-adrenergic receptor agonist; typically forms needle-shaped crystals with poor flowability [8] |

| n-Butanol (analytical grade) | Antisolvent for spherical crystallization [8] | Optimal for producing compact, uniform spherulites of salbutamol sulfate in water system [8] |

| sec-Butanol (analytical grade) | Antisolvent for novel solvate formation [8] | Produces previously unreported 1:1 solvate of salbutamol sulfate [8] |

| Deionized Water | Solvent for API dissolution [8] | Preparation of drug solution prior to antisolvent addition [8] |

| Crystallization Systems (e.g., Crystal16, Crystalline) | Automated solubility and metastable zone width determination [9] | Enables precise temperature control and transmissivity measurements for nucleation studies [9] |

Quantitative Kinetics Parameters

Table 2: Key parameters affecting nucleation and growth kinetics in antisolvent crystallization

| Parameter | Impact on Kinetics | Experimental Range | Optimal Conditions for Spherical Morphology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antisolvent Type | Influences supersaturation, solvate formation, and crystal habit [8] | ethanol, n-propanol, n-butanol, sec-butanol [8] | n-butanol (compact, uniform spherulites) [8] |

| Temperature | Affects solubility, nucleation, and growth rates [7] [9] | 10°C - 40°C [8] | 25°C (salbutamol sulfate spherulites) [8] |

| Antisolvent/Solvent Ratio | Controls supersaturation level (β) [8] [7] | 9:1 - 15:1 [8] | 9:1 (n-butanol-water system) [8] |

| Solute Concentration (Câ‚€) | Impacts final particle size and nucleation rate [8] [7] | 0.1 - 0.3 g·mLâ»Â¹ [8] | 0.2 g·mLâ»Â¹ (salbutamol sulfate) [8] |

| Agitation Rate | Affects mixing, secondary nucleation, and crystal branching [8] [9] | 250 - 350 rpm [8] | 250 rpm (initial studies) [8] |

| Feeding Rate | Controls local supersaturation at addition point [8] | 0.5 - 1 g·minâ»Â¹ [8] | 0.5 g·minâ»Â¹ (controlled addition) [8] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Spherical Crystallization via Antisolvent Addition

This protocol describes the preparation of spherical salbutamol sulfate particles through antisolvent crystallization, adapted from published methodology [8].

Materials and Equipment

- Salbutamol sulfate (2 g, purity >99%)

- Deionized water (10 mL)

- n-Butanol (90 mL, analytical grade)

- Double-jacketed crystallizers (2 units)

- Temperature control system with circulating water bath

- Peristaltic pump

- Magnetic stirrer

- Filtration apparatus

- Drying oven

Procedure

- Solution Preparation: In crystallizer 1, completely dissolve 2 g of salbutamol sulfate in 10 mL of deionized water to achieve a concentration of 0.2 g·mLâ»Â¹.

- Antisolvent Preparation: Add 90 mL of n-butanol to crystallizer 2, maintaining temperature at 25°C using the circulating water bath.

- Antisolvent Addition: Using the peristaltic pump, introduce the aqueous salbutamol sulfate solution into the antisolvent-containing crystallizer at a controlled rate of 0.5 g·minâ»Â¹.

- Crystallization Conditions: Maintain continuous stirring at 250 rpm and temperature at 25°C throughout the addition and subsequent holding period.

- Holding Time: After complete addition, continue stirring the suspension for an additional 60 minutes to allow for complete crystal growth and spherulite development.

- Product Isolation: Collect crystals by filtration and dry at 40°C until constant weight is achieved.

Notes

- The n-butanol-water system at 9:1 ratio produces compact, uniform spherulites under these conditions [8].

- The morphological evolution follows a spherulitic growth pattern where sheaves of plate-like crystals gradually branch into fully developed spherulites [8].

- For different API systems, preliminary solvent screening is recommended to identify optimal antisolvents.

Protocol 2: Determination of Nucleation Kinetics

This protocol describes the quantitative assessment of nucleation kinetics using isothermal induction time measurements, adapted from glycine crystallization studies [9].

Materials and Equipment

- Crystalline instrument (Technobis) or equivalent crystallization system

- API of interest

- Appropriate solvent and antisolvent

- Analytical balance

Procedure

- Stock Solution Preparation: Prepare stock solutions of the API in selected solvent at concentrations calculated to achieve desired supersaturation levels at the experimental temperature (e.g., 25°C).

- Sample Loading: Place stock solutions into crystallization vials, ensuring consistent volume across experiments (e.g., 3 mL).

- Dissolution Phase: Heat the vials to appropriate temperature (e.g., 55°C) for 30 minutes with agitation (e.g., 700 rpm) until complete dissolution is confirmed by 100% transmissivity.

- Isothermal Conditions: Rapidly cool to target temperature (e.g., 25°C) at a controlled rate (e.g., 5°C/min).

- Induction Time Measurement: Maintain isothermal conditions with continuous stirring and record the time elapsed from the start of the holding period until transmissivity decreases below 50%, indicating crystallization.

- Statistical Analysis: Repeat experiments 18-25 times at each supersaturation level to account for the stochastic nature of nucleation.

Data Analysis

- Calculate cumulative probability P(t) of induction times using: P(t) = M₊/M, where M is total experiments and M₊ is experiments where nucleation occurred at time ≤ t [9].

- Fit the exponential distribution: P(t) = 1 - exp[-JV(t - tð‘”)] to determine primary nucleation rate J and growth time tð‘” [9].

- Volume V is the solution volume in the vial (e.g., 3 mL).

Protocol 3: Investigation of Solvent-Dependent Kinetics

This protocol outlines a systematic approach for evaluating solvent-dependent nucleation and growth kinetics in combined cooling and antisolvent crystallization [10].

Materials and Equipment

- Crystal16 or similar multi-reactor crystallization system

- APIs of interest

- Various solvent-antisolvent combinations

- HPLC or other analytical method for concentration measurement

Procedure

- Solvent Screening: Select multiple solvent-antisolvent combinations based on API solubility differences.

- Solubility Determination: For each solvent system, determine equilibrium solubility using clear point measurements with extrapolation to zero heating rate.

- Metastable Zone Width: Determine metastable zone width by cooling solutions at fixed rates (0.1-0.5°C/min) and identifying temperature where transmissivity decreases below 50%.

- Kinetic Parameter Regression: Simultaneously regress solvent- and temperature-dependent kinetic parameters for continuous mixed-suspension, mixed-product removal (MSMPR) crystallization.

Application

- Growth and nucleation kinetic parameters are strong functions of solvent composition [10].

- Only growth kinetics show strong temperature dependence for the studied API/solvent/antisolvent systems [10].

- This approach enables rapid MSMPR cascade design and optimization for antisolvent crystallization processes.

Process Visualization and Workflows

The systematic investigation of nucleation and growth kinetics as a two-step process provides researchers with powerful tools for tailoring crystal morphology in pharmaceutical development. Through controlled antisolvent crystallization and precise parameter optimization, scientists can overcome challenging crystal habits and enhance pharmaceutical processing and product performance.

The protocols outlined in this Application Note enable comprehensive characterization of crystallization kinetics, facilitating the design of robust manufacturing processes. By understanding and manipulating the fundamental relationships between process parameters and crystal morphology, drug development professionals can significantly improve API properties, ultimately enhancing drug product quality and manufacturing efficiency.

Gibbs Free Energy and Chemical Potential in Crystal Formation

The controlled formation of crystals with tailored morphologies is a critical objective in materials science and pharmaceutical development. The processes of nucleation and crystal growth are fundamentally governed by thermodynamics, primarily the optimization of Gibbs free energy (G) across the system. At constant temperature and pressure, the chemical potential (μ), defined as the partial molar Gibbs free energy, becomes the decisive factor driving phase transitions and morphological outcomes [11]. In experimental practice, antisolvent treatment serves as a powerful, widely-used method to manipulate this thermodynamic landscape by rapidly inducing a state of supersaturation, thereby controlling the crystallization pathway [11] [12]. This Application Note details the theoretical relationship between Gibbs free energy and chemical potential in crystal formation and provides explicit protocols for leveraging this relationship through antisolvent strategies to achieve desired crystal morphologies.

Theoretical Foundation: Linking Thermodynamics to Crystallization

The Role of Gibbs Free Energy and Chemical Potential

The formation of a stable crystal nucleus from a solution is initiated when the system reaches a supersaturated state, where the chemical potential of the solute in the solution, ( \mu{solution} ), exceeds the chemical potential of the solute in the solid crystal, ( \mu{crystal} ) [11]. The driving force for nucleation and growth is this difference in chemical potential, ( \Delta\mu ). The chemical potential is intrinsically linked to the Gibbs free energy, ( G ), of the system by the relation: [ \mu = \left( \frac{\partial G}{\partial Ni} \right){T,P,N{i \neq j}} ] where ( Ni ) represents the number of particles of component i [11]. The process of nucleation and growth can therefore be tuned by regulating the chemical potential of the system. A higher supersaturation, or ( \Delta\mu ), generally leads to a higher nucleation rate but can also result in metastable, kinetically trapped morphologies if not carefully controlled [11] [2].

The Supersaturation Pathway in Antisolvent Crystallization

Antisolvent crystallization works by systematically altering the chemical potential of the solute. The addition of an antisolvent, which is miscible with the primary solvent but has a low solubility for the solute, reduces the solute's chemical potential in the solution phase. This shifts the system's thermodynamic state from undersaturated to supersaturated, initiating nucleation and growth [11] [12]. The following diagram illustrates this thermodynamic pathway and the corresponding experimental actions.

Quantitative Data for Experimental Design

The success of an antisolvent protocol depends critically on the selection of appropriate solvents and antisolvents, guided by quantitative solubility parameters and their resulting impact on crystal quality.

Table 1: Hansen Solubility Parameters (HSP) for Common Solvents and Antisolvents in Perovskite Crystal Growth [12]

| Solvent / Antisolvent | HSP δD (Dispersion) | HSP δP (Polar) | HSP δH (H-bonding) | Role in Crystallization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | 18.4 | 16.4 | 10.2 | Primary solvent (high solubility) |

| N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) | 17.4 | 13.7 | 11.3 | Co-solvent (modifies kinetics) |

| Ethanol | 15.8 | 8.8 | 19.4 | Antisolvent (optimized miscibility) |

| Chlorobenzene | 19.0 | 4.3 | 2.0 | Antisolvent (fast quenching) |

Table 2: Impact of Quenching Method on Final Film/Crystal Properties [13] [14]

| Quenching Parameter | Antisolvent Quenching | Gas Quenching | Performance Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wrinkle Density (μm/mm²) | ~65,000 | ~25,000 | Fewer pinholes, reduced defects [13] |

| Shunt Resistance (Ω) | -- | Significant increase | Lower dark current, higher efficiency [14] |

| Stability Retention | ~64% after 72h | ~81% after 72h | Superior long-term performance [14] |

| Process Control | Moderate (spreading) | High (pressure) | Better reproducibility and scaling [13] [14] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Antisolvent Vapor-Assisted Crystallization (AVC) for Large Single Crystals

This protocol, adapted for growing centimeter-scale CsPbBr₃ single crystals, exemplifies the precise control of supersaturation via vapor diffusion [12].

Principle: An antisolvent vapor slowly diffuses into a precursor solution, gradually and uniformly reducing the solute's chemical potential to initiate nucleation and sustain growth in the metastable zone, minimizing defect formation.

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Precursor Solution Preparation:

- Dissolve stoichiometric precursors (e.g., CsBr and PbBr₂ with a 1.5-fold excess of PbBr₂ to suppress Cs₄PbBr₆ byproduct formation) in a binary solvent system of 9:1 (v/v) DMSO/DMF [12].

- Stir the mixture at 50°C for 2 hours to ensure complete dissolution.

- Filter the solution through a 0.22 μm PTFE syringe filter to remove any undissolved particles.

- Induction of a Metastable State (Pre-Titration):

- Pre-treat the filtered solution by titrating with a liquid antisolvent (e.g., ethanol) until the onset of turbidity. This brings the system to the edge of the metastable zone.

- Re-filter this turbid solution to obtain a clear, metastable precursor. This step promotes controlled, sparse nucleation [12].

- Crystal Growth by Vapor Diffusion:

- Dispense aliquots of the metastable precursor solution into small vials.

- Place these vials inside a larger, sealed growth container containing a reservoir of the antisolvent (e.g., ethanol).

- For seeded growth, add a small seed crystal (≈1 mm) to each vial to suppress primary nucleation and favor large crystal growth.

- Maintain the setup at room temperature for 5-7 days. The slow diffusion of antisolvent vapor into the precursor solution initiates and sustains crystal growth [12].

- Crystal Harvesting:

- Carefully extract the grown crystals from the vials.

- Wash the crystals with a solvent like DMF to remove residual mother liquor and surface impurities.

- Air-dry the crystals before characterization.

Protocol 2: Spin-Coating with Antisolvent Quenching for Thin Polycrystalline Films

This protocol is standard for fabricating high-quality perovskite thin films for optoelectronics and demonstrates rapid, kinetic control of crystallization [11] [13].

Principle: During spin-coating, a burst of antisolvent is applied to the rotating substrate. This rapidly extracts the host solvent, creating an instantaneous, high level of supersaturation that triggers a dense nucleation event, resulting in smooth, pinhole-free polycrystalline films.

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation and Solution Deposition:

- Clean the substrate (e.g., glass/ITO) thoroughly and treat with UV-Ozone or plasma to ensure hydrophilic surface.

- Deposit a precise volume of the precursor solution onto the stationary or slowly spinning substrate.

- Spin-Coating and Antisolvent Quenching:

- Initiate the spin-coating program (e.g., a two-step process: 1000 rpm for 10 s followed by 4000-6000 rpm for 20-30 s).

- At a critical, optimized moment during the second, high-speed step (typically 5-10 seconds before the end), apply a controlled volume (e.g., 0.5-1.0 mL) of antisolvent (e.g., chlorobenzene, diethyl ether) directly onto the center of the spinning substrate [13]. The antisolvent must be miscible with the host solvent but not dissolve the perovskite precursors.

- Pressure-Controlled Spreading (Advanced Technique):

- For improved uniformity and larger grain size, use a low-pressure injection system to spread the antisolvent over a larger area. This minimizes localized shock and film damage, leading to a more uniform reduction in chemical potential [14].

- Post-Treatment and Annealing:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Antisolvent Crystallization

| Reagent / Material | Typical Examples | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Solvent | DMSO, DMF, Gamma-Butyrolactone (GBL) | Dissolves precursor materials; high Gutmann donor number coordinates with metal cations [12]. |

| Co-Solvent | DMF, N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) | Modifies solvation chemistry and evaporation kinetics of the primary solvent [12]. |

| Antisolvent | Toluene, Chlorobenzene, Diethyl Ether, Ethanol | Miscible with host solvent but reduces solute solubility, inducing supersaturation [13] [12]. |

| Precursor Salts | CsBr, PbBrâ‚‚; Organic Ammonium Salts (e.g., FAI) | Source of cations and anions for the target crystal structure. Stoichiometric excess can suppress impurities [12]. |

| Additives | Methylammonium Chloride (MACl), Polymers | Modifies growth kinetics, passivates defects, or influences crystal habit by selectively binding to specific crystal facets [13]. |

| Retusin (Standard) | Retusin (Standard), CAS:1245-15-4, MF:C19H18O7, MW:358.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Mesuaxanthone B | 1,5,6-Trihydroxyxanthone|CAS 5042-03-5|RUO | 1,5,6-Trihydroxyxanthone for research into antioxidant and anticancer mechanisms. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Antisolvent crystallization is a critical separation and particle engineering technique widely employed in the pharmaceutical industry for substances exhibiting weak temperature dependence of solubility. This process involves adding an antisolvent to a saturated solution of a solute, reducing its solubility and generating supersaturation, which leads to nucleation and crystal growth [15]. The careful selection of solvent-antisolvent systems directly impacts critical crystal properties including size distribution, morphology, and polymorphic form, which subsequently influence pharmaceutical properties such as bioavailability, stability, and processability [16] [6].

Hansen Solubility Parameters (HSP) provide a quantitative framework for predicting molecular interactions based on the principle that "like dissolves like" [17]. HSP deconstruct the total cohesive energy density of a material into three discrete components accounting for different intermolecular forces: dispersion forces (δD), polar interactions (δP), and hydrogen bonding (δH) [18] [17]. These parameters, typically measured in MPaâ°Â·âµ, define a three-dimensional coordinate in Hansen space where proximity between solvent and solute parameters indicates higher solubility potential [17].

Table 1: Fundamental Components of Hansen Solubility Parameters

| Parameter | Symbol | Intermolecular Forces Represented | Typical Range (MPaâ°Â·âµ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dispersion | δD | London dispersion forces | 14-20 |

| Polar | δP | Dipole-dipole interactions | 0-25 |

| Hydrogen Bonding | δH | Hydrogen donor/acceptor interactions | 0-42 |

For antisolvent crystallization, HSP theory enables rational selection of solvent-antisolvent pairs by predicting which solvents will effectively dissolve the solute and which antisolvents will sufficiently reduce solubility to induce crystallization. The interaction distance (Ra) between solute and solvent (or antisolvent) is calculated as:

[ (Ra)^2 = 4(\delta{D2} - \delta{D1})^2 + (\delta{P2} - \delta{P1})^2 + (\delta{H2} - \delta_{H1})^2 ]

The relative energy difference (RED) is then determined as RED = Ra/R₀, where R₀ is the interaction radius of the solute. An RED < 1 indicates high affinity, RED ≈ 1 indicates boundary condition, and RED > 1 indicates poor affinity [17]. This quantitative approach provides researchers with a powerful tool for optimizing crystal morphology and polymorphic outcomes in pharmaceutical development.

Recent Theoretical Advances and Improvements to HSP

While the original Hansen methodology has proven valuable for polymer applications, its application to small molecule solutes like active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) requires thermodynamic corrections. Recent research has introduced significant improvements to enhance prediction accuracy for pharmaceutical compounds [18].

Table 2: Thermodynamic Improvements to Hansen Solubility Parameters

| Improvement | Description | Impact on Prediction Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Solvent Size Correction | Incorporates solvent molar volume via effective radius (r_eff) calculation | Accounts for entropy effects of small solvent molecules |

| Concentration Correction | Adjusts for mole fraction differences in entropy-enthalpy balance | Enables combining data from different concentrations |

| Squared Distance | Uses squared parameter distance consistent with enthalpy of mixing theory | Provides thermodynamically sound distance metric |

| Donor-Acceptor Splitting | Separates δH into δHD (donor) and δHA (acceptor) parameters | Better models hydrogen bonding specificity |

| Temperature Extrapolation | Enables prediction of solubility at different temperatures | Expands practical utility across process conditions |

These thermodynamic refinements have demonstrated significant improvements in predictive capability, with one study reporting an increase in correct solubility predictions from 54% to 78% compared to the original Hansen method [18]. The implementation of these corrections is particularly valuable for pharmaceutical applications where precise control over crystallization outcomes is essential for product quality.

Furthermore, machine learning approaches are emerging as powerful tools for predicting HSP values. Recent studies have utilized algorithms including CatBoost, Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) to model the complex relationships between molecular structures and solubility parameters, with dielectric constant identified as the most significant predictor [19]. These data-driven methods complement the theoretical foundations of HSP while enhancing predictive accuracy for diverse chemical structures.

Experimental Protocol: Determining Hansen Parameters for API Crystallization Systems

Computational Determination via Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Principle: Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations can compute HSP values for complex solid surfaces and organic molecules, providing insights into interfacial interactions critical for crystallization [20].

Materials:

- Molecular modeling software (e.g., GROMACS, LAMMPS)

- Force field parameters for all components

- High-performance computing resources

Procedure:

- System Setup: Construct atomistic models of the API crystal surfaces and solvent/antisolvent molecules. For example, in studying siloxane-based surfactants on silicon oxide, a simplified atomistic SiOâ‚‚ surface model was developed [20].

- Parameterization: Assign appropriate force field parameters to all atoms, ensuring compatibility between organic molecules and inorganic surfaces.

- Simulation Execution: Perform MD simulations in an ensemble (NPT or NVT) with controlled temperature and pressure conditions relevant to the crystallization process.

- Energy Calculation: Extract cohesive energy densities from simulation trajectories by calculating the energy required to separate molecules.

- Parameter Extraction: Decompose the total cohesive energy into dispersion, polar, and hydrogen-bonding components using appropriate analysis methods.

- Validation: Compare predicted solubility behavior with experimental observations to validate the computed parameters.

Application Notes: This approach successfully predicted that polar solvents like acetone and triacetin form protective shields on silicon oxide surfaces, preventing surfactant adsorption in inkjet printing applications [20]. For pharmaceutical crystals, similar principles can guide solvent selection to control crystal habit or prevent unwanted additive adsorption.

Experimental Determination via Solubility Sphere Method

Principle: Experimental HSP values for an API are determined by testing its solubility in a diverse set of solvents with known HSP values and defining a solubility sphere in Hansen space [17].

Materials:

- Pure API sample (50-100 mg)

- Selected solvent set (20-30 solvents spanning Hansen space)

- Controlled temperature water bath

- Centrifuge for separation

- Analytical method for concentration determination (e.g., HPLC, UV-Vis)

Procedure:

- Solvent Selection: Choose a diverse set of solvents covering a broad range of δD, δP, and δH values. Include both good and poor solvents to define sphere boundaries.

- Solubility Testing: Add excess API to each solvent (1-2 mL) in sealed vials. Agitate continuously at constant temperature (typically 25°C) for 24 hours to reach equilibrium.

- Phase Separation: Centrifuge suspensions to separate undissolved solid from saturated solutions.

- Concentration Analysis: Quantify API concentration in the supernatant using appropriate analytical methods.

- Data Analysis: Classify solvents as "good" (solubility > threshold, e.g., 10 mg/mL) or "poor" based on experimental results.

- Sphere Fitting: Use HSP software or algorithms to fit a sphere in Hansen space that encompasses good solvents while excluding poor solvents. The sphere center defines the API's HSP coordinates, and the radius (Râ‚€) indicates its solubility specificity.

Application Notes: This experimental approach directly measures solubility behavior under relevant conditions. Recent improvements suggest incorporating concentration corrections and solvent size effects for more accurate results [18]. The resulting HSP sphere enables rational selection of solvent-antisolvent pairs for crystallization processes.

HSP Determination Workflow: This diagram illustrates the complementary computational and experimental pathways for determining Hansen Solubility Parameters, culminating in their application to solvent-antisolvent selection for crystallization processes.

Application Protocol: Designing Antisolvent Crystallization Processes Using HSP

Membrane-Assisted Antisolvent Crystallization (MAAC)

Principle: Membrane technology controls antisolvent addition to achieve superior mixing and prevent localized supersaturation, resulting in narrow crystal size distribution (CSD) and consistent crystal properties [21].

Materials:

- Hydrophobic membrane (polypropylene, PVDF, or PTFE)

- Membrane module with controlled flow paths

- Precision pumps for solution and antisolvent

- Temperature control system

- Glycine-water-ethanol model system or target API-solvent-antisolvent system

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare saturated solution of API in appropriate solvent (e.g., glycine in water at 23 wt%). Filter to remove undissolved particles.

- Antisolvent Selection: Use HSP analysis to identify antisolvents with sufficient distance in Hansen space (RED > 1) to reduce solubility while maintaining miscibility with the solvent.

- System Setup: Assemble membrane module with crystallizing solution and antisolvent on opposite sides of the hydrophobic membrane. Position module to control gravity effects (horizontal, vertical, or angled).

- Process Optimization:

- Set solution velocity between 0.00017–0.0005 m/s [21]

- Maintain temperature according to system requirements (e.g., 298.15–308.15 K for glycine)

- Adjust antisolvent composition (e.g., 40-100 wt% ethanol for glycine system)

- Crystallization Monitoring: Observe antisolvent transmembrane flux (target: 0.0002–0.001 kg/m²·s) and crystal formation.

- Product Characterization: Analyze crystal size distribution, morphology, and polymorphic form using appropriate analytical techniques.

Application Notes: This technique has demonstrated excellent consistency in producing narrow CSD with coefficient of variation (CV) of 0.5–0.6 compared to 0.7 for conventional batch crystallization [21]. The method maintains crystal morphology and polymorphic form while offering potential for continuous manufacturing.

Microfluidic Antisolvent Crystallization

Principle: Microfluidic reactors enable extreme control over mixing and supersaturation generation in antisolvent crystallization, allowing precise manipulation of crystal properties [16].

Materials:

- Microfluidic device with flow-focusing droplet generator

- Precision syringe pumps for controlled flow rates

- Microscopy system for in-situ observation

- Miconazole nitrate (MCN) in DMSO-water system or target API system

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve API in appropriate solvent (e.g., MCN in DMSO at 120 mg/mL). Filter solution to prevent clogging.

- Chip Priming: Prime microfluidic channels with continuous phase fluid to establish stable flow conditions.

- Droplet Generation:

- Set flow rate ratio to control droplet size (typically 1:5 to 1:10 aqueous-to-organic phase ratio)

- Maintain total flow rates between 10-50 μL/min for stable operation

- Crystallization Monitoring: Observe crystal nucleation and growth within droplets using in-situ microscopy.

- Product Collection: Collect crystals from outlet reservoir and characterize properties.

Application Notes: Microfluidic systems provide exceptional control over crystallization conditions, enabling the production of crystals with tailored size and morphology. For MCN, this approach facilitated the observation of crystal growth processes and analysis of crystal motion within droplets [16]. The method is particularly valuable for polymorph screening and obtaining fundamental crystallization kinetics data.

Table 3: Optimal Operating Conditions for Membrane Antisolvent Crystallization [21]

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Impact on Crystal Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Solution Velocity | 0.00017–0.0005 m/s | Higher velocity narrows CSD |

| Antisolvent Composition | 40–100 wt% ethanol | Affects supersaturation generation rate |

| Temperature | 298.15–308.15 K | Higher temperature increases crystal size |

| Membrane Orientation | Horizontal or vertical | Affects gravity resistance and flow dynamics |

| Transmembrane Flux | 0.0002–0.001 kg/m²·s | Controlled flux prevents localized supersaturation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for HSP-Guided Crystallization

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for HSP-Guided Antisolvent Crystallization

| Material/Reagent | Specifications | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Model Compound: Glycine | α-form, pharmaceutical grade | Model solute for crystallization studies with simple molecular structure and well-characterized polymorphism [21] |

| Hydrophobic Membranes | Polypropylene (PP), Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF), Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) with 150° contact angle | Controls antisolvent mass transfer in MAAC; prevents wetting by crystallizing solution [21] |

| Solvent Set for HSP Determination | 20-30 solvents spanning Hansen space (δD: 14-20, δP: 0-25, δH: 0-42 MPaâ°Â·âµ) | Experimental determination of API solubility sphere [17] |

| Microfluidic Device | Flow-focusing design with appropriate surface chemistry | Enables droplet-based antisolvent crystallization with superior mixing control [16] |

| Computational Software | Molecular dynamics packages with force fields for organic molecules | Calculates HSP values from first principles; models solvent-surface interactions [20] |

| Biotin sulfone | Biotin sulfone, CAS:40720-05-6, MF:C10H16N2O5S, MW:276.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Goniotriol | Goniotriol, CAS:96405-62-8, MF:C13H14O5, MW:250.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Hansen Solubility Parameters provide a powerful, quantitative framework for rational design of antisolvent crystallization processes in pharmaceutical development. The integration of recent thermodynamic improvements [18] with advanced implementation techniques such as membrane-assisted [21] and microfluidic crystallization [16] enables unprecedented control over critical crystal properties. By applying the protocols outlined in this document, researchers can systematically select solvent-antisolvent systems, optimize process parameters, and tailor crystal morphology to meet specific pharmaceutical requirements, ultimately enhancing drug product performance and manufacturing efficiency.

HSP Application Strategy: This workflow illustrates the systematic application of Hansen Solubility Parameters from initial API characterization through method selection and optimization to achieve desired crystal properties.

The control of crystal morphology is a critical objective in industrial solid-state chemistry, particularly within the pharmaceutical sector. The external shape of a crystal profoundly influences key product properties including bulk density, mechanical strength, wettability, flowability, and the efficiency of downstream processes such as filtration, drying, and tableting [2] [22]. In the specific context of energetic materials, morphology is directly linked to safety performance and detonation characteristics [23]. Tailoring crystal habit, therefore, represents a vital component of product design.

Antisolvent crystallization is a predominant separation technique for the purification and recovery of crystalline solids in the pharmaceutical and chemical industries [24]. This process is particularly amenable to morphology control, as the solvent environment and supersaturation profile can be strategically manipulated. The ability to predict and regulate the final crystal morphology is not merely a matter of convenience but a fundamental requirement for optimizing process design and final product performance. This Application Note details the evolution and application of established crystal morphology prediction models, with a specific focus on their utility in guiding antisolvent crystallization processes.

Foundational Morphology Prediction Models

Several theoretical models have been developed to predict the equilibrium or growth morphology of crystals based on their internal structure. These models provide a critical starting point for understanding and designing crystal habits.

Table 1: Foundational Crystal Morphology Prediction Models

| Model Name | Underlying Principle | Key Inputs | Primary Output | Major Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gibbs-Curie-Wulff Principle [2] | Crystal equilibrium shape minimizes total surface energy for a given volume. | Surface free energy (γi) of each crystal face (hkl). | Wulff shape; relative distances from crystal center to faces. | Describes the thermodynamic equilibrium morphology; often differs from growth morphology. |

| Bravais-Friedel-Donnay-Harker (BFDH) [2] [22] | Growth rate (Ghkl) of a face is inversely proportional to its interplanar spacing (dhkl). | Crystal lattice parameters and symmetry. | List of morphologically important faces and their relative growth rates. | Purely geometric; does not account for intermolecular interactions or solvent effects. |

| Attachment Energy (AE) [2] [23] | Growth rate (Rhkl) of a face is proportional to its attachment energy (Eatt), the energy released on attachment of a growth layer. | Crystal structure, including atomic coordinates and force field parameters. | Predicted crystal habit based on the relative attachment energies of different faces. | More physics-based than BFDH; but typically performed in vacuum, limiting environmental accuracy. |

| Modified Attachment Energy (MAE) [23] [25] | Modifies the AE model to account for solvent or additive adsorption on specific crystal faces, which reduces their growth rate. | Crystal structure + interaction energies between crystal surfaces and solvent/additive molecules. | Environment-specific crystal morphology, showing habit modification. | Provides more realistic predictions for crystallization from solution. |

The BFDH Model: A Geometric Starting Point

The BFDH model is one of the first and most straightforward models for crystal morphology prediction. It posits that the growth rate of a crystal face (hkl) is inversely proportional to its interplanar spacing, dhkl [2]:

Faces with a larger d-spacing (typically lower Miller indices) have a slower growth rate and thus become larger, morphologically important faces in the final crystal habit [22]. For instance, in a study on erythromycin A dihydrate (EMAD), the BFDH model successfully predicted a plate-like crystal habit bounded by the (002), (011), and (101) faces, which correlated well with crystals grown experimentally under certain conditions [22]. However, the model's primary limitation is its neglect of the chemical nature of the crystallizing compound and the growth environment, making it insufficient for predictive design in complex solvent systems [2].

The Attachment Energy Model: Incorporating Intermolecular Interactions

The Attachment Energy (AE) model, derived from the Periodic Bond Chain (PBC) theory, offers a more nuanced view by considering the crystal's internal energy distribution. The attachment energy (Eatt) is defined as the energy per molecule released when a new growth slice of thickness dhkl attaches to a crystal face [2]. The fundamental relationship in the AE model is that the growth rate of a face is proportional to the absolute value of its attachment energy [23]:

Faces with a higher attachment energy grow faster and thus become smaller or may disappear from the final morphology, while faces with a lower Eatt grow slower and dominate the crystal habit. This model has been widely used due to its computational simplicity and relatively reliable accuracy [23]. For example, the vacuum morphology of the energetic material PYX was predicted using the AE model, showing a needle-like habit, which aligned with experimental observations from many solvent systems [23].

Advanced Modeling: Accounting for the Environment with the MAE Model

While the AE model is an improvement over BFDH, its vacuum calculation limits predictive accuracy for solution crystallization. The Modified Attachment Energy (MAE) model addresses this critical gap by incorporating the effect of the solvent environment.

The MAE model calculates a corrected attachment energy (EMAE) that accounts for the energy binding of solvent molecules (Ebind) to the growing crystal face. The modified attachment energy is given by [23]:

Here, Ebind represents the energy released when solvent molecules adsorb onto a specific crystal face. A strong solvent-surface interaction (high Ebind) significantly reduces the effective attachment energy for that face, thereby slowing its growth rate and potentially altering the overall crystal habit. This model has proven highly effective in predicting solvent-induced morphology changes.

Case Study: Regulating PYX Morphology A study on the energetic material 2,6-bis(picrylamino)-3,5-dinitropyridine (PYX) demonstrated the power of the MAE model. The vacuum AE prediction showed a needle-like morphology. However, MAE simulations in solvents like dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) predicted a noticeable reduction in aspect ratio, which was subsequently confirmed by experimental cooling crystallization [23]. The model revealed that these solvents selectively adsorbed onto the faster-growing faces, inhibiting their growth and resulting in a more desirable, stout crystal.

Case Study: ε-CL-20 in Binary Solvents Similarly, research on ε-CL-20 employed the MAE model to understand the effect of 13 different binary solvent systems. The study found that the model predictions of crystal morphology were "in good accordance with that observed in the experiments" [25]. The analysis further identified that hydrogen bonding and Coulomb interactions were the primary drivers of solvent-crystal interactions, and that surface roughness played an important role in solvent adsorption behavior.

Figure 1: A workflow for employing a hierarchy of morphology models, from simple geometric prediction to environment-aware simulation, validated against experimental data to guide rational crystal design.

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation and Application

The following protocols outline key methodologies for validating model predictions and engineering crystal morphology in an antisolvent crystallization context.

Protocol 1: Molecular Dynamics Simulation for MAE-based Morphology Prediction

Purpose: To predict the crystal morphology of a target compound in a specific solvent or solvent/antisolvent system using the Modified Attachment Energy model.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Molecular Modeling Software: Packages such as Mercury (CCDC) or Materials Studio (BIOVIA) for BFDH/AE analysis; molecular dynamics (MD) software like GROMACS or LAMMPS.

- Force Field: A suitable classical force field (e.g., COMPASS, CVFF) to describe interatomic interactions.

- Crystal Structure: The CIF (Crystallographic Information File) for the compound of interest from databases like the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) or in-house single-crystal XRD data.

Procedure:

- Input Crystal Structure: Retrieve or load the single-crystal structure of the target compound (e.g., PYX, CSD Refcode) [23].

- Generate Vacuum Morphology: Calculate the vacuum equilibrium morphology using the AE model as a baseline.

- Model the Solvent Environment: Construct a simulation box containing the crystal slab of a specific face (e.g., (0 1 1), (1 0 0)) and solvate it with solvent molecules (e.g., DMSO, ethanol) [23].

- Run Molecular Dynamics Simulation: Perform energy minimization and an MD simulation (e.g., in the NPT ensemble at 298K and 1 bar for several nanoseconds) to equilibrate the system.

- Calculate Binding Energy: For a crystal face (hkl), the solvent binding energy (Ebind) is calculated as:

where Etotal is the energy of the crystal-solvent system, Ecrystal_slab is the energy of the crystal slab in vacuum, and Esolvent is the energy of the solvent molecules alone [23]. - Compute Modified Attachment Energy: For each face, calculate EMAE = Eatt - Ebind.

- Predict Morphology: Assume the growth rate of each face Rhkl ∠EMAE and construct the predicted crystal habit.

Protocol 2: Antisolvent Crystallization for Crystal Habit Modification

Purpose: To experimentally produce crystals with modified morphology based on computational predictions, using solvent/antisolvent selection and additive-mediated crystallization.

Table 2: Key Reagents for Antisolvent Crystallization

| Reagent Type | Example | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| API/Solute | Erythromycin A Dihydrate (EMAD) [22] | The target compound whose morphology is to be controlled. |

| Solvent | Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) [23], Ethanol [22] | A solvent that readily dissolves the solute. |

| Antisolvent | Water [22], n-Heptane | A solvent in which the solute has low solubility, used to generate supersaturation. |

| Polymer Additive | Hydroxypropyl Cellulose (HPC) [22], Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) [23] | Adsorbs onto specific crystal faces to inhibit growth and modify habit. |

| Surfactant Additive | Tween 80, Span 20 [23] | Can act as tailor-made inhibitors or wetting agents to control crystal growth. |

Procedure:

- Prepare Saturated Solution: Dissolve an excess of the target compound (e.g., EMAD) in a suitable solvent (e.g., ethanol) at ambient temperature and filter to remove any undissolved particles [22].

- Prepare Antisolvent/Additive Solution: Place the antisolvent (e.g., water) into the crystallization vessel. If using additives, dissolve them at the desired concentration (e.g., 0.45-4.5 wt% for HPC [22]) in the antisolvent.

- Initiate Crystallization: Under constant stirring, slowly add the filtered saturated solution to the antisolvent (e.g., at a solvent to antisolvent ratio of 1:9 v/v) [22].

- Age the Slurry: Continue stirring the suspension for a predetermined time to allow for complete crystal growth and habit development.

- Isolate and Characterize: Filter the crystals, wash with a minimal amount of antisolvent, and dry. Characterize the resulting crystal morphology using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and confirm the solid form using Powder X-Ray Diffraction (PXRD) and Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) to ensure no polymorphic transformation has occurred [22].

The journey from the geometric BFDH model to the environment-aware MAE model represents a significant advancement in our ability to rationally design crystal morphology. While BFDH provides a quick initial estimate, the AE and, more powerfully, the MAE model, offer a physics-based foundation for understanding and predicting how solvents and additives in an antisolvent crystallization process will influence the final crystal habit. The integration of molecular dynamics simulations with targeted experimental validation, as demonstrated in the cited case studies, provides a robust framework for researchers and drug development professionals to move away from empirical screening towards a predictive strategy for crystal morphology engineering. This approach is indispensable for tailoring materials with optimal handling, processing, and performance properties.

Practical Implementation: Antisolvent Techniques and Pharmaceutical Applications

Microfluidic Antisolvent Crystallization for Long-Acting Injectables

Long-acting injectable (LAI) formulations are parenteral delivery systems designed to provide sustained drug release over periods ranging from days to months, significantly improving patient compliance and quality of life by minimizing administration frequency [26] [27]. These formulations are particularly beneficial for patients with chronic conditions such as mental disorders, HIV infection, and tuberculosis, where medication adherence is crucial for treatment success [26]. While current marketed suspension-based LAIs are predominantly manufactured using top-down methods like wet media milling and high-pressure homogenization, these approaches present challenges including high energy requirements, mechanical stress on APIs, and potential product contamination [26] [27].

Microfluidic antisolvent crystallization has emerged as a promising bottom-up alternative for producing LAI microsuspensions, offering precise control over critical quality attributes including particle size distribution (PSD), crystal morphology, and polymorphic form [26] [28]. This technology enables superior mixing efficiency through microscale channels and static mixers, facilitating rapid supersaturation generation with highly precise spatial and temporal distribution [26]. The continuous nature of microfluidic processes provides additional advantages for pharmaceutical manufacturing, including straightforward scale-up, fewer processing steps, and improved reproducibility [26] [28]. This application note details protocols for implementing microfluidic antisolvent crystallization specifically for LAI development, framed within broader research on tailoring crystal morphology through antisolvent treatment.

Theoretical Framework: Crystal Morphology Control

Crystal morphology is a critical quality attribute in pharmaceutical development, significantly influencing product performance, bulk density, mechanical strength, wettability, and downstream processing operations such as filtration and drying [2]. The final morphology of crystal products results from the combined effects of the compound's internal structure and external growth environment conditions, including cooling rate, solvent selection, and supersaturation [2].

Crystal Growth Models and Prediction

Several theoretical models have been developed to predict and understand crystal growth behavior:

Gibbs-Curie-Wulff Principle: This fundamental principle states that under isothermal and isobaric equilibrium conditions, crystal geometry spontaneously forms to achieve minimum total surface energy, known as the Wulff shape [2].

BFDH Model: The Bravais-Friedel-Donnay-Harker model predicts crystal morphology based on geometric calculations considering lattice parameters and crystal symmetry, proposing that crystal face growth rate (Ghkl) is inversely proportional to crystal face spacing (dhkl) [2].

Attachment Energy Model: This widely used model, based on periodic bond chain theory, suggests that the growth rate of crystal faces is proportional to their attachment energy—the energy released when a growth slice attaches to the crystal surface [2]. This model offers advantages of simple calculation steps and relatively reliable accuracy.

Table 1: Crystal Morphology Prediction Models

| Model | Fundamental Principle | Key Equation | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gibbs-Curie-Wulff | Minimum total surface energy at equilibrium | ∑Siγi = Min | Determines equilibrium crystal shape |

| BFDH | Inverse relationship between growth rate and interplanar spacing | Ghkl ∠1/dhkl | Predicts possible growth faces based on crystal geometry |

| Attachment Energy | Growth rate proportional to energy released during layer attachment | Ghkl ∠Eatt | Most widely used model with simple calculation steps |

Microfluidic Antisolvent Crystallization Principles

Antisolvent crystallization operates on the principle that adding an antisolvent to a solution reduces solute solubility, generating supersaturation that drives nucleation and crystal growth [28]. Microfluidic technology enhances this process through superior mixing control in microscale channels, enabling precise manipulation of supersaturation profiles and crystallization kinetics [26] [28].

The key advantages of microfluidic systems for antisolvent crystallization include:

- Enhanced Mixing Efficiency: Microfluidic devices achieve intense mixing through static micromixers, creating a purely diffusive mixing environment that disperses the reaction/diffusion zone along the channel downstream [26].

- Reduced Fouling and Clogging: Flow-focusing geometries can guide nucleation away from reactor walls, minimizing encrustation issues common in conventional continuous crystallizers [26].

- Superior Particle Control: Consistent residence times and physical/chemical environments enable production of particles with controlled PSD, morphology, and polymorphism [26] [28].

- Real-time Monitoring: Advanced microfluidic systems like the Secoya Technology provide real-time monitoring capabilities for better process parameter control [26].

Application Notes: LAI Formulation Development

Case Study: Itraconazole LAI Microsuspensions

Recent research has demonstrated the successful application of Secoya microfluidic crystallization technology-based continuous liquid antisolvent crystallization for producing itraconazole LAI microsuspensions [26] [27]. The optimized process achieved:

- Final solid loading of 300 mg ITZ/g suspension after downstream concentration

- Post-precipitation feed suspension concentration of 40 mg ITZ/g suspension

- Drug-to-excipient ratio of 53:1, significantly improved compared to previous methods

- PSD maintained within the target range of 1-10 μm

- Elongated plate-shaped crystal morphology

- Form I solid state, the most thermodynamically stable form of ITZ [26]

This microfluidic approach demonstrated advantages over earlier microchannel reactor-based continuous liquid antisolvent crystallization setups, which typically yielded post-precipitation feed suspensions containing only 10 mg ITZ/g suspension with drug-to-excipient ratios of 2:1 [26].

Polymorph Control with Acoustic Cavitation

Emerging research explores combining microfluidic antisolvent crystallization with acoustic cavitation for enhanced polymorph control. A recent study using ROY as a model compound demonstrated that ultrasound application significantly affects polymorphic outcomes, promoting formation of stable crystal forms in both batch and flow crystallization setups [29]. This approach leverages cavitation-induced micro-mixing and local heating effects to influence crystal form nucleation, providing an additional parameter for morphology control [29].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Secoya Microfluidic Crystallization of Itraconazole

Objective: Produce itraconazole microsuspensions with target PSD of 1-10 μm for LAI formulations [26].

Materials:

- Itraconazole (>99% purity)

- N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (HPLC grade)

- D-α-tocopherol polyethylene glycol 1000 succinate (Vit E TPGS 1000)

- Type I ultrapure deionized water

- Secoya SCT-LAB microfluidic device

Equipment:

- Secoya microfluidic crystallization system

- Temperature-controlled feed reservoirs

- Precision syringe pumps

- In-line monitoring tools (optional)

- Centrifugation system for downstream processing

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation:

- Prepare ITZ solution in NMP at appropriate concentration (optimized at 40 mg/g)

- Prepare antisolvent stream containing stabilizer (Vit E TPGS 1000) in deionized water

- Filter both solutions through 0.45 μm filters to remove particulate matter

System Setup:

- Mount the Secoya SCT-LAB microfluidic device according to manufacturer instructions

- Connect solvent and antisolvent feed lines to respective inlet ports

- Set temperature control system to maintain constant temperature (typically 20-25°C)

- Prime both feed lines to remove air bubbles

Process Operation:

- Set solvent-to-antisolvent flow rate ratio based on optimization studies (typically 1:5 to 1:10)

- Adjust total flow rate to achieve desired residence time (typically seconds to minutes)

- Initiate simultaneous pumping of both streams

- Monitor pressure drops to detect potential clogging

- Collect effluent suspension in appropriate container

Downstream Processing:

- Concentrate suspension via centrifugation or ultrafiltration to achieve target solid loading (300 mg ITZ/g suspension)

- Resuspend particles with gentle mixing

- Characterize final suspension for PSD, solid form, and morphology

Critical Parameters:

- Solvent-to-antisolvent ratio

- Total flow rate and residence time

- Stabilizer type and concentration

- Temperature control

- Mixing intensity

Protocol 2: Microfluidic Crystallization with Acoustic Cavitation

Objective: Investigate effect of acoustic cavitation on polymorph nucleation in microfluidic antisolvent crystallization [29].

Materials:

- Model compound (e.g., ROY, 99% purity)

- Appropriate solvent (e.g., acetone, HPLC grade)

- Antisolvent (e.g., deionized water)

- Custom glass capillary microfluidic device

Equipment:

- Microfluidic flow crystallizer with acoustic transducer

- Precision pumps

- Signal generator and amplifier

- High-speed camera for visualization

- ATR-FTIR for polymorph characterization

- Temperature control system

Procedure:

- System Configuration:

- Set up flow crystallizer with integrated ultrasonic transducer

- Determine resonance frequency of system (typically 30-45 kHz)

- Calibrate power output (typically 3-8 W net electrical power)

- Establish temperature control at desired setpoint (e.g., 20°C)

Solution Preparation:

- Prepare saturated API solution in solvent

- Determine solubility at different antisolvent volume fractions if unknown

- Filter solutions before use

Experimental Operation:

- Set total flow rate (e.g., 2.5 mL/min or 10 mL/min)

- Adjust antisolvent volume fraction (0.2, 0.4, 0.85)

- Conduct experiments under silent and sonicated conditions

- Record process with high-speed camera when applicable

- Collect output suspension for analysis

Analysis:

- Filter and dry product crystals

- Characterize polymorphic form using ATR-FTIR

- Analyze crystal morphology using light microscopy

- Determine induction times and yields

Critical Parameters:

- Acoustic frequency and power

- Antisolvent volume fraction

- Flow rate and residence time

- Supersaturation ratio

- Temperature

Table 2: Key Operating Parameters for Microfluidic Antisolvent Crystallization

| Parameter | Typical Range | Impact on Crystallization | Optimization Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solvent-to-Antisolvent Ratio | 1:5 to 1:10 | Controls supersaturation generation; affects nucleation rate | OFAT approach to balance nucleation and growth |

| Total Flow Rate | 2.5-10 mL/min | Determines residence time; affects mixing efficiency | Adjust to achieve target PSD without clogging |

| Stabilizer Concentration | Drug:Excipient 53:1 | Impacts physical stability and Ostwald ripening | Minimum required to maintain suspension stability |

| Temperature | 20-25°C | Affects solubility and supersaturation | Maintain constant for process reproducibility |

| Acoustic Power (when applied) | 3-8 W | Influences polymorph selection through micro-mixing | Optimize for target polymorph without equipment damage |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Microfluidic Antisolvent Crystallization

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Specifications | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Itraconazole (API) | Model drug compound | >99% purity, BCS Class II | Representative poorly soluble compound for LAI development |

| N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone | Solvent | HPLC grade, >99.5% purity | Pharmaceutically acceptable solvent for API dissolution |

| Vit E TPGS 1000 | Stabilizer | Ph. Eur. grade, USP grade | Effective crystal growth modifier and suspension stabilizer |

| Deionized Water | Antisolvent | Type I ultrapure | Reduces API solubility, generating supersaturation |

| Sodium CMC | Alternative stabilizer | Pharmaceutical grade | Polymer stabilizer for suspension physical stability |

| Poloxamers (188, 338, 407) | Surfactant stabilizers | Pharmaceutical grade | Non-ionic triblock copolymers for crystal surface stabilization |

| Porsone | Porsone, CAS:56222-03-8, MF:C22H26O6, MW:386.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Z-D-Meala-OH | Z-D-Meala-OH, CAS:68223-03-0, MF:C12H15NO4, MW:237.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Analytical Methods for Characterization

Comprehensive characterization of the resulting microsuspensions is essential for quality control and ensuring product performance.

Particle Size Distribution:

- Utilize laser diffraction or dynamic light scattering

- Target range: 1-10 μm for LAI microsuspensions

- Monitor stability over time to detect Ostwald ripening

Solid-State Characterization:

- Employ X-ray powder diffraction for polymorph identification

- Use differential scanning calorimetry for thermal behavior

- Confirm form I ITZ as most thermodynamically stable form

Morphological Analysis:

- Scanning electron microscopy for detailed crystal morphology

- Light microscopy for rapid assessment

- Target: elongated plate-shaped morphology for ITZ

In Vitro Release Testing:

- Develop sink conditions appropriate for poorly soluble compounds

- Compare release profiles against reference formulations