Mastering Crystal Growth: How Temperature Difference (ΔT) Controls Nucleation and Growth Rates for Advanced Materials and Pharmaceuticals

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of temperature difference (ΔT) as a critical control parameter in crystal growth processes, with specific relevance to pharmaceutical and materials science research.

Mastering Crystal Growth: How Temperature Difference (ΔT) Controls Nucleation and Growth Rates for Advanced Materials and Pharmaceuticals

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of temperature difference (ΔT) as a critical control parameter in crystal growth processes, with specific relevance to pharmaceutical and materials science research. It explores the foundational principles linking ΔT to boundary layer supersaturation and nucleation kinetics, detailing advanced methodological approaches for precise experimental control. The content addresses common troubleshooting challenges such as scaling and unwanted homogeneous nucleation, and validates techniques through data-driven optimization and comparative analysis of growth environments. By synthesizing foundational theory with practical application, this resource equips scientists with strategies to manipulate crystal morphology, growth rates, and final material properties for enhanced drug development and advanced material fabrication.

The Fundamental Role of ΔT in Crystal Nucleation and Growth Kinetics

Linking Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) to Boundary Layer Supersaturation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the precise role of boundary layer supersaturation in crystallization processes? The boundary layer is a thin region of solution adjacent to a surface (like a membrane or crystal) where concentration gradients exist. Its supersaturation level is often the primary controlling factor for nucleation, rather than the supersaturation in the bulk solution. In membrane systems, for example, temperature differences (ΔT) across the membrane can create a boundary layer with a significantly higher supersaturation level, which directly drives the nucleation rate according to Classical Nucleation Theory [1].

FAQ 2: According to CNT, how do homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation differ within a boundary layer? CNT describes that both mechanisms involve overcoming a free energy barrier, but they differ in the location and height of this barrier.

- Homogeneous Nucleation occurs spontaneously in the bulk solution or within the boundary layer when a solution becomes highly supersaturated. It has a high energy barrier as it requires forming a new phase without a surface [2].

- Heterogeneous Nucleation occurs on a pre-existing surface (like a membrane, dust particle, or container wall). The surface catalyzes the process by lowering the nucleation energy barrier, making it the more common mechanism, especially in the constrained environment of a boundary layer [2].

FAQ 3: Our experiments show large deviations between measured and CNT-predicted nucleation rates. What could be the cause? This is a common challenge. Key troubleshooting areas include:

- Inaccurate Supersaturation Estimation: The actual supersaturation in the boundary layer can be much higher than in the bulk. Ensure your calculations account for the concentration gradient and temperature difference (ΔT) at the interface [1].

- Ion Pairing and Complexation: In aqueous solutions, ions can form pairs or complexes, reducing the concentration of free ions available for nucleation. This affects the ionic activity product (IAP) and the accurate calculation of supersaturation [3].

- Limitations of CNT: CNT treats microscopic nuclei as macroscopic droplets with well-defined surface tensions, which may not hold for very small clusters. For systems with only a few molecules, CNT can become less accurate [2].

FAQ 4: How can we experimentally measure the supersaturation in a boundary layer? Direct measurement is challenging due to the thinness of the layer. Common indirect methodologies involve:

- Induction Time Measurement: Measuring the time between achieving supersaturation and the first detection of nuclei. A shorter induction time indicates a higher boundary layer supersaturation. A modified power law can relate this to CNT parameters [1].

- Non-Invasive Techniques: Using methods like planar laser scattering (NPLS) to observe flow and structures within the boundary layer, which can be correlated with supersaturation conditions [4].

FAQ 5: What is the critical supersaturation threshold, and why is it important for controlling crystal growth? The critical supersaturation threshold is the specific supersaturation level above which rapid, uncontrolled scaling occurs (often via homogeneous nucleation), and below which controlled crystal growth (often via heterogeneous nucleation) can proceed. Identifying this threshold for your system allows you to "switch off" scaling and grow crystals with a preferred morphology in the bulk solution by carefully controlling the temperature (T) and temperature difference (ΔT) [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Uncontrolled Scaling and Fouling on Membrane Surfaces

- Symptoms: Rapid formation of tenacious crystal deposits on surfaces, clogging pores and reducing efficiency.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Excessively high supersaturation in the boundary layer, triggering homogeneous nucleation.

- Cause: Inadequate mixing or flow, leading to a thick, stagnant boundary layer with high local supersaturation.

- Solution: Increase turbulence or flow velocity near the surface. This enhances mass transfer and reduces the thickness of the boundary layer, preventing the buildup of extreme supersaturation [3].

Problem 2: Excessive Ostwald Ripening in Final Product

- Symptoms: Over time, small crystals dissolve and re-deposit onto larger crystals, leading to a wide and unpredictable crystal size distribution (CSD).

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Sustained low levels of supersaturation during the final stages of growth, which is the driving force for Ostwald ripening.

- Solution: Control the cooling or anti-solvent addition profile to ensure supersaturation is depleted more rapidly and completely. This minimizes the time the system spends in the low-supersaturation regime where Ostwald ripening dominates [5].

- Cause: The presence of a wide range of crystal sizes from the nucleation and growth phases.

- Solution: Improve control over the initial nucleation burst. Use the insights from CNT to design a seeding strategy or a controlled nucleation protocol that creates a more uniform initial population of crystals, reducing the driving force for ripening [5].

- Cause: Sustained low levels of supersaturation during the final stages of growth, which is the driving force for Ostwald ripening.

Problem 3: Inconsistent Crystal Morphology and Polymorph Formation

- Symptoms: Batches of crystals exhibit different shapes or crystal structures, leading to inconsistent product performance (e.g., in drug dissolution).

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Fluctuating supersaturation levels during growth, which can favor different crystal faces or polymorphs.

- Solution: Precisely control both T and ΔT. Research shows that T and ΔT can be used collectively to fix the supersaturation set point within the boundary layer, which directly influences crystal morphology [1]. Implement a feedback control system to maintain constant supersaturation.

- Cause: Secondary nucleation mechanisms generating new crystals with different habits.

- Solution: Minimize mechanical shear and crystal-impeller/crystal-crystal collisions during agitation, as these events can generate new nuclei that grow under different local conditions [1].

- Cause: Fluctuating supersaturation levels during growth, which can favor different crystal faces or polymorphs.

Quantitative Data and CNT Parameters

Table 1: Key Supersaturation Metrics and Formulas

| Metric | Formula | Description & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Supersaturation Ratio (S) | ( S = \frac{C}{C^*} ) | The ratio of the actual concentration (C) to the equilibrium saturation concentration (C*). A primary driving force in CNT [3]. |

| Relative Supersaturation (σ) | ( \sigma = \frac{C - C^}{C^} = S - 1 ) | An alternative measure of the driving force for crystallization [3]. |

| Solubility Product (Ksp) | ( K{sp} = a{Ba^{2+}} \cdot a{SO4^{2-}} ) | The equilibrium constant for a solid dissolving. Precipitation occurs when the Ion Activity Product (IAP) > Ksp [3]. |

| Saturation Ratio (Ω) | ( \Omega = \frac{IAP}{K_{sp}} ) | For ionic solutions. Ω < 1 (undersaturated), Ω = 1 (saturated), Ω > 1 (supersaturated) [3]. |

| Chemical Potential Driving Force (Δμ) | ( \Delta \mu = kT \ln(S) ) | The fundamental thermodynamic driving force for phase transformation; used to derive CNT expressions [3]. |

Table 2: Core Equations of Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT)

| Concept | Equation | Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Homogeneous Nucleation Rate (R) | ( R = NS Z j \exp\left({\frac{-\Delta G^*}{kB T}}\right) ) | ( \Delta G^* ): Energy barrier; ( kB T ): Thermal energy; ( NS ): Number of nucleation sites; ( Z ): Zeldovich factor; ( j ): Attachment frequency [2]. |

| Free Energy Barrier (( \Delta G^* )) | ( \Delta G^* = \frac{16 \pi \sigma^3}{3(\Delta g)^2} ) | ( \sigma ): Surface tension; ( \Delta g ): Gibbs free energy change per unit volume (related to Δμ) [2]. |

| Critical Radius (( r_c )) | ( rc = -\frac{2 \sigma Tm}{\Delta Hf} \frac{1}{Tm - T} ) | ( Tm ): Melting point; ( \Delta Hf ): Latent heat of fusion. For solutions, an analogous form exists with supersaturation [2]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Non-Invasive Measurement of Induction Times in Boundary and Bulk Phases

Purpose: To discriminate between nucleation events occurring in the boundary layer and the bulk solution, and to relate these to the boundary layer supersaturation [1].

Methodology:

- System Setup: Utilize a membrane crystallization cell equipped with precise temperature control for both the feed and permeate sides (establishing ΔT). Include a high-resolution optical monitoring system (e.g., microscope with camera).

- Induction Time in Bulk Solution: Initiate the experiment with a uniform, undersaturated solution. Apply the thermal gradient (ΔT). Use the optical system to record the time (( \tau_{bulk} )) until the first crystals are detected in the bulk solution away from the membrane surface.

- Induction Time at Membrane Surface: In a separate but identical experiment, focus the optical monitoring system on the membrane surface. Record the time (( \tau_{surface} )) until the first crystals appear on the membrane.

- Data Analysis: A significantly shorter ( \tau{surface} ) compared to ( \tau{bulk} ) indicates that the boundary layer supersaturation is higher than the bulk. The induction times can be fitted to a modified power law (( \tau \propto S^{-n} )) to extract kinetic parameters related to CNT and quantify the effective supersaturation in the boundary layer [1].

Protocol 2: Determining the Critical Supersaturation Threshold for Scaling

Purpose: To identify the specific supersaturation level above which undesirable homogeneous nucleation and scaling occur on the membrane [1].

Methodology:

- Experimental Series: Conduct a series of crystallization experiments at a constant bulk temperature (T) but with systematically increasing temperature differences (ΔT). Each ΔT corresponds to a specific calculated boundary layer supersaturation.

- Morphology Analysis: For each experiment, analyze the resulting solid phase using microscopy and/or X-ray Diffraction (XRD).

- Threshold Identification: The critical supersaturation threshold is identified as the ΔT (and its corresponding supersaturation) at which the crystal habit shifts from well-defined, bulk-grown crystals to a tenacious, scaly deposit on the membrane surface. Below this threshold, scaling is "switched off" [1].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for CNT and Boundary Layer Crystallization Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Model Solute (e.g., Lysozyme, Insulin) | A well-characterized substance (often a protein or salt) used to study fundamental nucleation and growth kinetics. Its crystallization behavior is of direct relevance to pharmaceutical development [5]. |

| Buffer Solutions | Used to maintain a constant pH, which is critical for controlling the solubility and charge of proteins and ionic species, thereby directly influencing supersaturation [3]. |

| Precipitating Agents (e.g., Salts, Polymers) | Agents like ammonium sulfate or PEG added to reduce solute solubility and create a supersaturated environment, providing the driving force for crystallization [3]. |

| Membrane Crystallization Cell | A core component that facilitates the creation of a controlled boundary layer. The temperature difference (ΔT) across the membrane is the primary lever for manipulating boundary layer supersaturation [1]. |

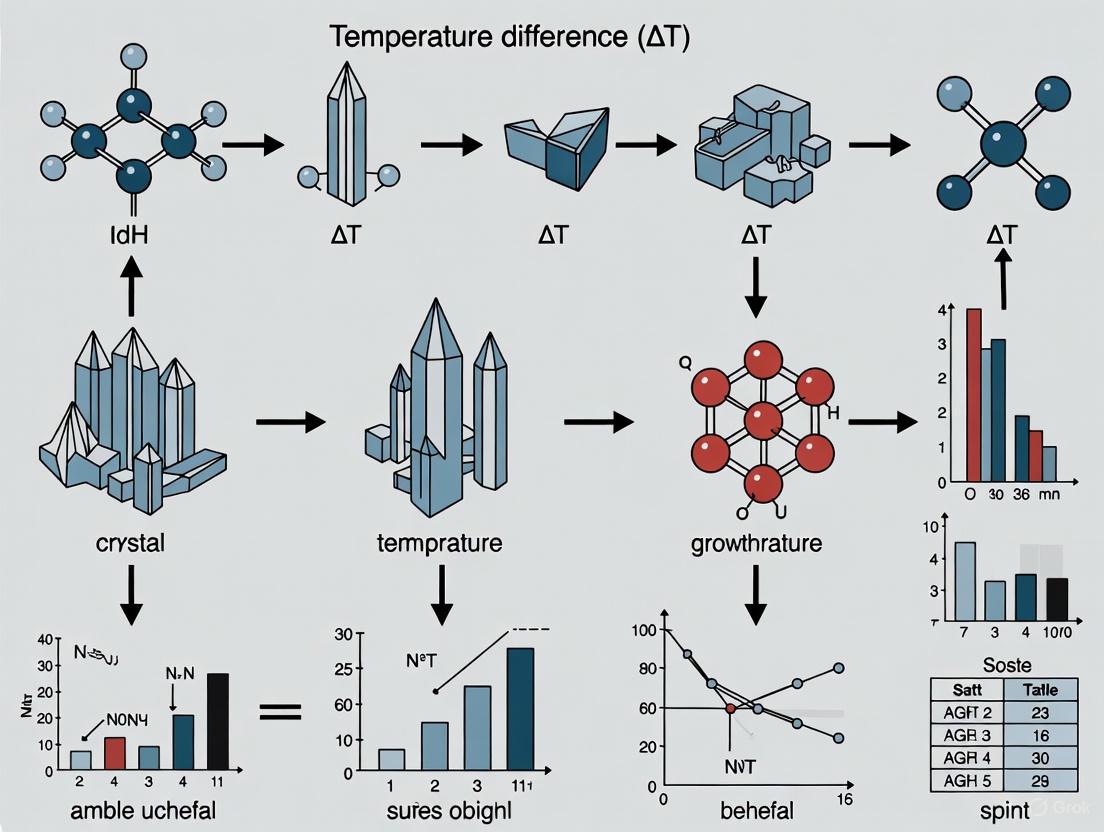

Process Visualization

Diagram 1: CNT-Based Crystallization Workflow

How ΔT and Absolute Temperature (T) Collectively Control Supersaturation Set Points

A technical support guide for crystallization researchers

FAQs: Fundamental Concepts

1. What is the fundamental role of supersaturation in crystallization?

Supersaturation is the thermodynamic driving force for both nucleation and crystal growth. It describes a state where the concentration of a solute exceeds its equilibrium saturation value, making the solution unstable and prone to precipitation [3]. The degree of supersaturation can be expressed as the concentration difference (ΔC = C - C), the supersaturation ratio (S = C/C), or relative supersaturation (σ = (C - C)/C), where C is the solution concentration and C* is the equilibrium saturation concentration [3].

2. How do absolute temperature (T) and temperature difference (ΔT) collectively influence supersaturation?

Absolute temperature (T) and temperature difference (ΔT) work in concert to adjust boundary layer properties and define the operational supersaturation set point. Research has established a log-linear relationship between nucleation rate and the supersaturation level in the boundary layer, which is characteristic of Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) [1]. Specifically:

- Absolute Temperature (T) primarily controls crystal growth rate [1]. Higher temperatures generally increase molecular mobility and diffusion rates, accelerating growth.

- Temperature Difference (ΔT) primarily controls nucleation rate in the boundary layer [1]. Larger ΔT values create steeper concentration gradients.

By manipulating both parameters, researchers can fix the supersaturation set point within the boundary layer to achieve preferred crystal morphology and control the crystal size distribution (CSD) [1].

3. What is the critical supersaturation threshold and why is it important?

The critical supersaturation threshold is a specific supersaturation level above which scaling becomes probable. Beyond this threshold, homogeneous nucleation occurs, leading to scaling on membrane surfaces and equipment [1]. Operating below this threshold allows researchers to "switch off" kinetically controlled scaling while maintaining crystal growth solely in the bulk solution, typically resulting in preferred cubic morphologies [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Uncontrolled nucleation and scaling on equipment surfaces

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Supersaturation levels in the boundary layer exceed the critical threshold, promoting homogeneous nucleation [1].

- Solution: Reduce the temperature difference (ΔT) to decrease the boundary layer supersaturation. Implement simultaneous heating and cooling cycles to promote dissolution-recrystallization and prevent scaling [6].

- Cause: Inadequate identification of the metastable zone width (MSZW) for your specific system.

- Solution: Characterize the MSZW experimentally to define safe operating limits. The metastable zone is the area between the solubility curve and the supersaturation curve where spontaneous nucleation is unlikely under normal conditions [3].

Problem: Obtaining broad crystal size distributions (CSD)

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Uncontrolled secondary nucleation throughout the process.

- Solution: Use automated direct nucleation control (ADNC), applying controlled heating and cooling cycles to dissolve fine crystals and suppress secondary nucleation [6].

- Cause: Suboptimal combination of T and ΔT for the desired CSD.

- Cause: Insufficient mixing or mass transfer during crystallization.

- Solution: Employ advanced crystallizer designs like the Couette-Taylor (CT) crystallizer, which generates Taylor vortex flow for superior heat and mass transfer, promoting uniform CSD [6].

Problem: Failure to achieve target crystal morphology

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Supersaturation profile does not favor the desired habit.

- Solution: Implement supersaturation control (SSC) to maintain a constant supersaturation level within the metastable zone. Combine SSC with optimized seed recipes to shape the CSD effectively [7].

- Cause: Incorrect seeding strategy.

- Solution: Optimize seed loading, size, and distribution. Consider dynamic seeding, where seed is added as a control variable rather than just an initial condition, to achieve complex CSD shapes [7].

Experimental Data Reference

Table 1: Operational Parameters and Their Effects on Crystallization Outcomes

| Parameter | Effect on Nucleation | Effect on Crystal Growth | Impact on CSD | Typical Experimental Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute Temperature (T) | Indirect effect via solubility | Direct control; higher T typically increases growth rate [1] | Larger crystals at higher T if nucleation is controlled [1] | 45-60°C (in referenced study) [1] |

| Temperature Difference (ΔT) | Primary control in boundary layer; higher ΔT increases nucleation rate [1] | Secondary effect | Higher nucleation rate increases fine crystal count, broadening CSD [1] | 15-30°C (in referenced study) [1] |

| Supersaturation Ratio (S) | Direct relationship; higher S increases nucleation rate | Direct relationship; higher S increases growth rate | Optimal S needed for balance; too high leads to broad CSD [7] | System-dependent; must be within metastable zone [3] |

| Residence Time | Longer time increases probability of nucleation events | Longer time allows for larger crystal size | Critical for achieving target mean size in continuous processes [6] | 2.5-15 minutes (in CT crystallizer) [6] |

Table 2: Non-Isothermal Continuous Crystallization Parameters for L-lysine

| Parameter | Condition 1 | Condition 2 | Impact on Process Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature Difference (ΔT) | 0°C (Isothermal) | 18.1°C | Effective reduction of CSD width achieved with higher ΔT [6] |

| Rotation Speed | 200 rpm | 900 rpm | Facilitates Taylor vortex flow for improved mixing and heat transfer [6] |

| Mean Residence Time | 2.5 minutes | 15 minutes | Shorter times increase productivity but may not achieve steady state [6] |

| Flow Direction | Inner heating/Outer cooling | Outer heating/Inner cooling | Alters temperature gradients and local supersaturation profiles [6] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing Supersaturation Control in Batch Cooling Crystallization

This protocol outlines a systematic method to design a supersaturation-controlled (SSC) batch cooling crystallization process to achieve a target Crystal Size Distribution (CSD), based on the approach described by Nagy et al. [7].

System Characterization:

- Determine the solubility curve and metastable zone width (MSZW) for your compound in the chosen solvent. This can be done by measuring the concentration and temperature at which nucleation first occurs upon cooling.

- Identify crystal growth kinetics. This typically involves seeded experiments at different supersaturation levels to model the growth rate, G(S,L).

Analytical CSD Estimator:

- For a growth-dominated process at constant supersaturation, the final CSD can be estimated using an analytical solution of the population balance equation. The final crystal size, L, relates to the initial seed size, L₀, by the equation: L = L₀ + G(S) × τ, where G(S) is the growth rate and τ is the batch time [7].

Design Parameter Optimization:

- A design parameter, ξ, is introduced as a function of batch time and supersaturation. An optimization problem is solved to find the value of ξ that produces a CSD with the desired shape (e.g., narrow, monomodal, or specific multimodal distribution) while meeting the required yield [7].

Setpoint Determination:

- From the optimal ξ, calculate the required supersaturation setpoint and batch time. Alternatively, fix one (e.g., supersaturation based on MSZW limits) and calculate the other.

Implementation:

- Implement the supersaturation controller using an appropriate PAT tool (e.g., ATR-FTIR, FBRM) to maintain the solution at the target supersaturation throughout the batch.

Protocol 2: Continuous Cooling Crystallization with Non-Isothermal Taylor Vortex

This protocol describes a methodology for controlling CSD in a continuous Couette-Taylor (CT) crystallizer using a non-isothermal Taylor vortex, as demonstrated for L-lysine [6].

Crystallizer Setup:

- Utilize a CT crystallizer consisting of two coaxial cylinders with an annular gap.

- Connect independent temperature control units (e.g., thermal jackets) to both the inner and outer cylinders.

Solution Preparation:

- Prepare a concentrated feed solution (e.g., 900 g/L for L-lysine) at a temperature above its saturation point (e.g., 50°C for L-lysine with a saturation temperature of 43°C) to ensure complete dissolution [6].

System Stabilization:

- Pre-fill the crystallizer with pure solvent (e.g., deionized water). Set both cylinders to the target bulk solution temperature (Tb, e.g., 28°C) for isothermal pre-operation (e.g., 20 minutes) [6].

Non-Isothermal Operation:

- Initiate feed flow at the desired rate (e.g., corresponding to a 2.5-minute residence time) and set the inner cylinder to rotate (e.g., 200 rpm).

- Establish a temperature difference (ΔT) by increasing the temperature of one cylinder (Th) and decreasing the other (Tc), while maintaining the average bulk temperature Tb.

- Two modes can be tested:

- Mode A: Inner cylinder heating (Tih), Outer cylinder cooling (Toc).

- Mode B: Inner cylinder cooling (Tic), Outer cylinder heating (Toh).

Monitoring and Analysis:

- Use in-line probes (e.g., FBRM, PVM) to monitor chord length distribution and crystal morphology in real-time.

- Once steady state is reached, collect suspension samples from various ports along the crystallizer axis for offline CSD analysis (e.g., using video microscopy) [6].

Diagram: T and ΔT Control Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

| Item | Function / Explanation | Example from Context |

|---|---|---|

| Couette-Taylor (CT) Crystallizer | A continuous crystallizer with concentric cylinders creating Taylor vortex flow for superior mixing and heat/mass transfer [6]. | Used for L-lysine crystallization with internal temperature control on both cylinders [6]. |

| Process Analytical Technology (PAT) | Tools for real-time monitoring of crystallization processes. | Focused Beam Reflectance Measurement (FBRM) for tracking crystal counts and size; ATR-FTIR for concentration monitoring [7] [6]. |

| Seeds (Optimized Recipe) | Initial crystals used to promote controlled growth and suppress excessive primary nucleation. | Critical for CSD shaping in supersaturation control (SSC) design; can be monodisperse or a designed mixture [7]. |

| Saturation Ratio (S) / Relative Supersaturation (σ) | The calculated driving force for crystallization. | S = C/C; σ = (C-C)/C, where C is concentration and C is equilibrium saturation [3]. The key parameter for controller setpoints. |

| Metastable Zone Width (MSZW) | The concentration-temperature region between saturation and spontaneous nucleation. | Defines the safe operating limits for supersaturation control to avoid uncontrolled nucleation [3] [7]. |

| Sco-267 | Sco-267, MF:C36H46N4O5, MW:614.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Gozanertinib | Gozanertinib, CAS:1226549-49-0, MF:C32H31N5O3, MW:533.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Log-Linear Relationship Between Nucleation Rate and Boundary Layer Supersaturation

Within the broader research on controlling crystal growth rate through temperature difference (ΔT), understanding and controlling the initial formation of crystals—nucleation—is paramount. This technical support guide addresses the log-linear relationship between nucleation rate and boundary layer supersaturation, a cornerstone principle of Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) that has been validated in modern membrane distillation crystallization (MDC) studies [1]. This relationship provides a powerful lever for researchers to control whether crystallization occurs homogeneously (leading to scaling) or heterogeneously in the bulk solution, and to dictate the final crystal size and shape [1] [8]. The following FAQs and troubleshooting guides are designed to help you apply this principle effectively in your experiments.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental relationship between nucleation rate and supersaturation in the boundary layer?

Research has established a characteristic log-linear relation between the nucleation rate and the supersaturation level in the boundary layer [1]. This means that a plot of the logarithm of the nucleation rate against the supersaturation level produces a straight line, which is a fingerprint of CNT. The supersaturation in the boundary layer, rather than in the bulk solution, is the critical controlling factor for nucleation in systems like MDC.

Q2: How can I experimentally determine the nucleation rate in my system?

The most common and accessible method is the induction time measurement [9]. The induction time is defined as the time between creating supersaturation and the first detection of a crystal. By running multiple identical, small-scale experiments and measuring the distribution of induction times, you can calculate the nucleation rate. Automated systems like the Crystal16 can dramatically reduce the time required for these measurements using feedback control [9].

Q3: What is the critical supersaturation threshold and why is it important?

Studies have identified a critical supersaturation threshold in the boundary layer [1]. Below this value, scaling (homogeneous nucleation on the membrane surface) can be effectively "'switched-off'", allowing crystals to form solely in the bulk solution with a preferred cubic morphology. Operating above this threshold leads to homogeneous scaling, which is difficult to control and can foul equipment.

Q4: How do temperature (T) and temperature difference (ΔT) function as control parameters?

Temperature (T) and temperature difference (ΔT) are independent but complementary control parameters [1]:

- ΔT is the primary knob for adjusting the nucleation rate. A higher ΔT increases supersaturation in the boundary layer, accelerating nucleation.

- T (average temperature) can be used to adjust the crystal growth rate. Collectively, T and ΔT can be used to fix a supersaturation set point in the boundary layer to achieve a specific crystal morphology and size distribution [1].

Q5: What advanced control strategies can help regulate nucleation and growth?

Supersaturation control strategies are key for segregating the crystal phase into the bulk solution, thereby improving crystal habit, shape, and purity independent of nucleation [8]. Furthermore, techniques like non-isothermal Taylor vortex flow in a Couette-Taylor crystallizer can narrow the crystal size distribution (CSD) by promoting dissolution-recrystallization cycles, effectively removing fines and controlling the final product size [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Uncontrolled Scaling (Fouling) on Membrane Surfaces

Problem: Rapid, unpredictable formation of scale on membrane surfaces, leading to blockages and process failure.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: The supersaturation in the boundary layer has exceeded the critical threshold for homogeneous nucleation [1].

- Solution: Reduce the temperature difference (ΔT) across the membrane. This directly lowers the supersaturation level in the boundary layer, moving the system out of the homogeneous nucleation regime [1].

- Solution: Increase the average temperature (T), if process constraints allow, to modify the boundary layer properties and metastable zone width [1].

- Cause: Inadequate crystal retention, leading to deposition on the membrane.

- Solution: Implement in-line filtration to ensure crystals are retained within the crystallizer and not deposited on the membrane surface. This helps maintain a consistent supersaturation rate and reduces scaling [8].

Issue 2: Excessive Fines and Wide Crystal Size Distribution (CSD)

Problem: The final crystalline product contains too many small particles (fines) and has an overly broad size distribution, affecting filtration and product performance.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Nucleation rate is too high relative to the growth rate, resulting in many small crystals.

- Solution: Fine-tune ΔT and T to lower the boundary layer supersaturation, thereby reducing the nucleation rate and favoring growth of existing crystals [1].

- Solution: Implement fines destruction cycles. Using a technique like the non-isothermal Taylor vortex, apply controlled heating and cooling cycles to dissolve fine crystals and allow them to recrystallize onto larger ones, narrowing the CSD [6].

- Cause: Insufficient hold-up time after induction, not allowing for crystal growth and desaturation.

- Solution: Optimize process conditions to ensure a longer hold-up time following the initial nucleation event. This allows crystal growth to desaturate the solvent, which in turn suppresses further nucleation and results in larger crystals [8].

Issue 3: Inconsistent or Irreproducible Nucleation Rates

Problem: Nucleation induction times vary widely between identical experiments, making process development and scale-up difficult.

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: The stochastic nature of nucleation is dominating, and not enough data is being collected.

- Solution: Perform a large number of small-scale, identical induction time experiments (e.g., using a Crystal16) to build a statistically significant probability distribution from which a reliable nucleation rate can be calculated [9].

- Cause: Poor control over temperature and supersaturation profiles.

- Solution: Utilize equipment with automated feedback control to precisely manage temperature and detect crystallization events (cloud points). This ensures highly consistent experimental conditions from one run to the next [9].

- Solution: For continuous processes, ensure precise control over the residence time and mixing intensity within the crystallizer, as these are critical for achieving a consistent CSD [6].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Measuring Nucleation Rate via Induction Times

This protocol is adapted from methods successfully demonstrated using automated crystallization platforms [9].

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a solution of your target compound in the desired solvent at a known concentration.

- Generate Supersaturation: For a cooling crystallization, rapidly cool the solution from a temperature where it is fully dissolved to a predetermined crystallization temperature.

- Measure Induction Time: Start a timer when the target crystallization temperature is reached. The induction time is the period until the first crystals are detected (e.g., by a drop in transmissivity) [9].

- Repeat: Conduct a minimum of 50-100 identical experiments under the same conditions of supersaturation (temperature, concentration) to account for stochasticity [9].

- Analyze Data: Plot the cumulative probability of crystallization against time. The nucleation rate can be calculated from the fitting parameters of this probability distribution [9].

Protocol 2: Establishing the Log-Linear Relationship for Your System

This protocol is based on non-invasive techniques used to relate boundary layer properties to CNT [1].

- Set Up a Membrane Crystallization System capable of independent control of feed temperature (influencing T) and permeate side temperature (defining ΔT).

- Define Experimental Matrix: Choose a range of T (e.g., 45–60 °C) and ΔT (e.g., 15–30 °C) values [1].

- Measure Induction Times: For each (T, ΔT) pair, perform multiple induction time experiments (as in Protocol 1) to determine the average nucleation rate, J.

- Calculate Boundary Layer Supersaturation: Use measured induction times and a modified power law relation to link the data to the supersaturation level in the boundary layer at the point of nucleation [1].

- Plot and Interpret: Plot log(J) against the calculated supersaturation. A straight-line relationship confirms CNT behavior and allows you to extract system-specific kinetic parameters.

Quantitative Data from Literature

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent research on nucleation and crystal growth control.

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Parameters for Nucleation and Crystal Growth Control

| System / Parameter | Value / Range | Control Objective | Key Outcome | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Membrane Crystallization | T: 45–60 °C; ΔT: 15–30 °C | Fix boundary layer supersaturation | Log-linear relation confirmed; Scaling can be switched off below a critical supersaturation. | [1] |

| L-lysine Continuous Crystallization | ΔT (cylinders): 18.1 °C; Rotation: 200 rpm | Narrow CSD | Non-isothermal Taylor vortex reduced CSD via dissolution-recrystallization. | [6] |

| Control Strategy Performance | N/A | Minimize crystal size variation | Model Predictive Control (MPC) superior to PID and GMC in settling time & overshoot. | [10] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Materials and Equipment for Nucleation and Crystal Growth Experiments

| Item | Function / Application | Brief Explanation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Automated Lag-Time Apparatus (e.g., Crystal16) | Measurement of induction times and nucleation rates. | Enables multiple, small-scale, statistically significant experiments with automated temperature and transmissivity control. | [9] |

| Couette-Taylor (CT) Crystallizer | Continuous crystallization with narrow CSD. | Generates Taylor vortex flow for superior mixing; non-isothermal operation enables fines dissolution and CSD control. | [6] |

| Focused Beam Reflectance Measurement (FBRM) | In-situ monitoring of crystal particles. | Provides real-time, chord-length distribution data to track nucleation and growth kinetics. | [6] |

| Model Predictive Control (MPC) | Advanced process control for crystallizers. | An optimization-based control strategy that handles constraints and process nonlinearities better than standard PID controllers. | [10] |

| 24, 25-Dihydroxy VD2 | 24, 25-Dihydroxy VD2, MF:C28H44O3, MW:428.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Antitumor agent-156 | Antitumor agent-156, MF:C48H77Cl3N5O12Pt-2, MW:1217.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Process Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and control strategy for managing nucleation and crystal growth based on the principles discussed.

Discriminating Between Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Nucleation Mechanisms

Within the broader research on temperature difference (ΔT) crystal growth rate control, discriminating between homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation mechanisms is a fundamental challenge. These distinct pathways dictate critical outcomes in industrial crystallization, from the purity of pharmaceutical compounds to the extent of membrane scaling. Homogeneous nucleation occurs spontaneously in the bulk solution when a system achieves a high supersaturation level without the aid of surfaces. In contrast, heterogeneous nucleation takes place on foreign surfaces, impurities, or membrane interfaces at significantly lower supersaturation levels [1] [11]. This technical guide provides researchers with diagnostic criteria, experimental protocols, and troubleshooting advice to identify and control these mechanisms in laboratory settings.

Diagnostic Criteria and Theoretical Framework

Key Differentiating Factors

Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) provides the theoretical foundation for discriminating between nucleation mechanisms. The table below summarizes the core differentiators:

Table 1: Characteristics of Homogeneous vs. Heterogeneous Nucleation

| Characteristic | Homogeneous Nucleation | Heterogeneous Nucleation |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleation Sites | Bulk solution only [1] | Surfaces, interfaces, or impurities [11] |

| Energy Barrier (ΔG)* | Higher energy barrier [11] | Reduced barrier: ΔGhet = f(θ)ΔGhom [11] |

| Critical Supersaturation | Higher threshold required [1] | Occurs at lower supersaturation levels [1] |

| Spatial Distribution | Uniform throughout bulk solution | Localized at catalytic surfaces |

| Induction Time | Shorter at high supersaturation [1] | Variable depending on surface properties |

| Crystal Morphology | Distinctive habit different from heterogeneous [1] | Often influenced by substrate properties |

The contact angle (θ) between the nucleating phase and the substrate directly determines the reduction of the energy barrier through the wettability function f(θ) = (2-3cosθ+cos³θ)/4 [11]. This mathematical relationship explains why heterogeneous nucleation predominates in most practical scenarios.

Quantitative Analysis of Nucleation Kinetics

According to Classical Nucleation Theory, the nucleation rate (R) follows a predictable relationship:

R = NSZj exp(-ΔG*/kBT) [11]

where ΔG* represents the free energy barrier, kB is Boltzmann's constant, and T is temperature. The exponential dependence on ΔG* creates the dramatic difference between homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation rates.

Table 2: Experimental Parameters for Mechanism Discrimination

| Experimental Parameter | Homogeneous Regime | Heterogeneous Regime |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Supersaturation (σ) | High (σ > 0.048 for NaClO3) [12] | Low to moderate [1] |

| Temperature Control | Critical for suppression [1] | Less sensitive |

| ΔT Effect | Induces scaling at high ΔT [1] | Promotes controlled growth |

| Nucleation Rate | Rapid increase above threshold [1] | More gradual increase |

| Crystal Size Distribution | Narrow [1] | Broader distribution |

| Boundary Layer Properties | High supersaturation in boundary layer [1] | Moderate boundary layer supersaturation |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Non-Invasive Induction Time Measurement

Objective: To measure induction times in discrete domains (membrane surface and bulk solution) to discriminate nucleation mechanisms [1].

Materials and Equipment:

- Membrane distillation system with temperature control

- Non-invasive imaging (optical microscopy with reflection interference contrast)

- Temperature-controlled crystallization chamber

- High-resolution camera for time-lapse recording

Procedure:

- Prepare solutions with precise supersaturation levels using temperature control (T range: 45-60°C) [1].

- Adjust temperature difference (ΔT range: 15-30°C) to modify boundary layer properties [1].

- Simultaneously monitor membrane surface and bulk solution for nucleation events.

- Record induction times (time to first observable nucleation) for both domains.

- Apply modified power law relation between supersaturation and induction time [1].

- Analyze crystal size distributions to correlate nucleation mechanism with growth rates.

Interpretation: Shorter induction times at membrane surfaces at moderate supersaturation indicate heterogeneous nucleation, while rapid nucleation in bulk solution at high supersaturation suggests homogeneous mechanisms [1].

Nanoconfined Crystal Growth Analysis

Objective: To observe nucleation and growth at nanometric distances from a substrate using Reflection Interference Contrast Microscopy (RICM) [12].

Materials and Equipment:

- RICM setup with high-intensity LED illumination

- Glass coverslips or confining substrates

- NaClO3 or CaCO3 crystal solutions

- Spacer particles (10-80 nm diameter) to control distance [12]

- Closed chamber with precise supersaturation control (σ = c/c0 - 1)

Procedure:

- Create strictly controlled bulk solution supersaturation in closed chamber.

- Measure distance (ζ) between confining glass coverslip and crystal surface using RICM.

- For distances ζ < 125 nm, calculate height relative to local mean with sub-nanometer precision.

- Monitor nucleation of molecular layers on confined facets.

- Record propagation of two-dimensional monolayer islands.

- Analyze nucleation localization patterns relative to contact edges.

- For systems with dislocations (∼5% of crystals), observe spiral growth dynamics [12].

Interpretation: Homogeneous nucleation of molecular layers occurs even in contact with other solids, with new layers raising the macroscopic crystal. Nucleation localization shifts from random distribution to edge-concentrated as supersaturation increases due to ion depletion effects in confined spaces [12].

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Nucleation Mechanism Discrimination

Determination of Nucleation Rates

Objective: To quantitatively determine nucleation rates as a function of supersaturation for mechanism identification [13].

Materials and Equipment:

- Temperature gradient annealing apparatus

- Al-Cu alloy samples (3.7 wt.% Cu)

- Induction coil heating system

- Scanning electron microscope

- Image analysis software for particle size distribution

Procedure:

- Prepare homogeneous, coarse-grained Al-Cu alloy samples.

- Apply temperature gradient annealing to achieve partial melting.

- Quench samples to preserve early-stage melting structures.

- Identify former liquid regions through secondary phase formation.

- Analyze spherical secondary-phase particles (50 nm to 1 μm) from single nucleation events.

- Measure particle size distributions at different temperature positions.

- Combine microstructural characterization with numerical simulation to determine time-resolved nucleation rates [13].

Interpretation: Bimodal droplet distributions suggest multiple types of nucleation sites, with nucleation rates featuring distinct maxima at different times indicating competing homogeneous and heterogeneous mechanisms [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Nucleation Mechanism Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Experimental Function |

|---|---|---|

| NaClO3 crystals | High purity, (001) surface orientation [12] | Model system for nanoconfined growth studies |

| CaCO3 crystals | Laboratory grade | Biomineralization and confinement studies [12] |

| Al-Cu alloy | 3.7 wt.% Cu, homogenized [13] | Metallic system for nucleation rate determination |

| Spacer particles | 10-80 nm diameter [12] | Control distance in nanoconfinement experiments |

| Glass coverslips | Optical quality | Transparent confinement surfaces [12] |

| Membrane materials | Various surface properties | Study heterogeneous nucleation at interfaces [1] |

| Darbufelone | Darbufelone, MF:C18H24N2O2S, MW:332.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Concanamycin E | Concanamycin E, MF:C44H71NO14, MW:838.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs

Q1: How can we suppress homogeneous nucleation to prevent scaling in membrane systems?

A: Research demonstrates that homogeneous nucleation (scaling) occurs at high boundary layer supersaturation. To suppress it:

- Maintain supersaturation below the critical threshold through precise ΔT control [1]

- Reduce temperature difference (ΔT) to decrease boundary layer supersaturation [1]

- Implement surface modifications to promote controlled heterogeneous nucleation instead

- Operate within the "metastable zone" where crystal growth occurs without excessive nucleation [14]

Q2: What diagnostic patterns indicate a shift from heterogeneous to homogeneous nucleation?

A: Key indicators include:

- Abrupt decrease in induction time [1]

- Shift from surface-localized to bulk-phase crystallization

- Change from isolated crystals to numerous microcrystals [14]

- Alteration in crystal morphology and habit [1]

- Sudden increase in nucleation rate above supersaturation threshold [12]

Q3: How does nanoconfinement affect nucleation mechanisms?

A: Nanoconfinement creates distinctive nucleation behaviors:

- New molecular layers nucleate homogeneously even when in contact with solids [12]

- Nucleation localizes near contact edges at higher supersaturation due to ion depletion [12]

- Spiral growth from dislocations becomes skewed toward contact edges [12]

- Two-dimensional mass transport through liquid films governs growth dynamics [12]

Q4: How can temperature (T) and temperature difference (ΔT) be optimized to control crystal morphology?

A: Experimental evidence shows:

- ΔT primarily adjusts nucleation rate by controlling boundary layer supersaturation [1]

- T mainly influences crystal growth rate after nucleation [1]

- Using T and ΔT collectively fixes boundary layer supersaturation to achieve preferred morphology [1]

- Higher T with moderate ΔT promotes controlled growth over chaotic nucleation

Figure 2: Troubleshooting Pathway for Membrane Scaling Issues

Advanced Technical Notes

Theoretical Foundation of Nucleation Barriers

The critical free energy barrier for homogeneous nucleation is derived from CNT:

ΔG*hom = 16πσ³/(3|Δgv|²) [11]

where σ is interfacial tension and Δgv is the volumetric free energy change. For heterogeneous nucleation, this barrier reduces by a factor related to the contact angle:

ΔGhet = f(θ)ΔGhom [11]

This theoretical framework explains why heterogeneous nucleation dominates under most experimental conditions and provides the basis for interpreting induction time measurements and supersaturation thresholds.

Practical Implications for Pharmaceutical Development

Controlling nucleation mechanisms directly impacts drug development:

- Homogeneous nucleation produces numerous small crystals with high surface area

- Heterogeneous nucleation yields larger, more uniform crystals

- Membrane scaling from homogeneous nucleation compromises filtration systems [1]

- Crystal morphology affects bioavailability, purification, and formulation processes [14]

By applying the discrimination techniques outlined in this guide, researchers can strategically manipulate experimental conditions to achieve desired crystalline products while avoiding operational issues like membrane scaling and uncontrolled crystallization.

FAQs: Understanding Critical Supersaturation

What is Critical Supersaturation and why is it fundamental to my crystallization experiments? Critical Supersaturation is the minimum level of water vapor saturation (relative to a plane surface of pure water) required for a cloud condensation nucleus (CCN) of a given size and composition to activate and form a stable cloud droplet [15]. In the broader context of crystallization, it represents the precise threshold at which a solute in a solution begins to transition from a dissolved state to forming stable solid nuclei. This concept is vital because it directly controls the number concentration of particles that will form, whether cloud droplets or crystals. Understanding and controlling this threshold is essential for predicting and regulating the outcome of crystallization processes, influencing everything from crystal size and purity to polymorphism [15].

How does Critical Supersaturation relate to the competing mechanisms of nucleation and crystal growth? Supersaturation is the driving force for both nucleation (the formation of new crystals) and crystal growth (the enlargement of existing crystals) [8]. The position of your system within the metastable zone—the region between saturation and critical supersaturation—determines which mechanism is favored. Close to the saturation point, crystal growth is favored, leading to larger, more uniform crystals. As you approach the Critical Supersaturation threshold, the system favors a primary nucleation pathway, resulting in the spontaneous formation of many small crystals, which can lead to scaling [8]. Effective control strategies therefore involve modulating supersaturation to position the system within a specific region of the metastable zone that favors the desired outcome.

What are the practical consequences of poorly controlled supersaturation in industrial or research settings? Poor control can lead to two primary issues: scaling and inconsistent product quality. When supersaturation is too high, it broadens the metastable zone width and favors homogeneous primary nucleation [8]. This leads to the formation of a large number of fine crystals on surfaces (scaling) and within the bulk solution, which can foul equipment and introduce competition between crystal growth and nucleation mechanisms [8]. The result is often a low yield of crystals with poor habit, shape, and purity, which is unacceptable in industries like pharmaceuticals where these properties are critical.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Problems & Solutions

Problem 1: Uncontrolled Spontaneous Crystallization (Scaling)

Observation: The experiment results in a mass of small, intergrown crystals or a glassy, syrup-like solid, often coating the vessel walls instead of forming discrete crystals.

Explanation: This occurs when the system's supersaturation rapidly exceeds the critical supersaturation threshold, pushing it deeply into the labile (unstable) zone where spontaneous nucleation is rampant [16].

Solutions:

- Controlled Nucleation: Avoid simply cooling a highly concentrated solution. Instead, try evaporating the solvent at an elevated temperature to gently generate a few crystal seeds, then control further growth by slow cooling [16].

- Seeding Technique: Cool your solution until spontaneous crystallization just begins, then gently warm it until nearly all crystals dissolve. The few remaining crystals will serve as seeds for controlled growth upon subsequent cooling [16].

- Avoid Glass Vessels: Solvent can creep up the hydrophilic walls of glass beakers, causing nucleation outside the main solution. Use polypropylene or Teflon vessels, or silanize glassware to make it hydrophobic [16].

- Modulate Supersaturation Rate: Research shows that using membrane area to adjust the concentration rate can shorten induction time and allow you to reposition the system within a specific region of the metastable zone that favors growth over primary nucleation [8].

Problem 2: Failure to Nucleate (No Crystallization)

Observation: Despite achieving a supersaturated state, no crystals form, even after prolonged waiting.

Explanation: Crystallization is often kinetically hindered. The system is in a metastable supersaturated state but lacks a nucleation site to initiate the process [16].

Solutions:

- Ultrasound: Using ultrasound, such as from a standard laboratory cleaning bath or by gently scratching the crystallization vessel with a glass rod, can often induce nucleation [16].

- Heterogeneous Nucleation: Intentional introduction of impurities or a rough surface can act as nucleation sites. Ensure your solutions are not overly pure without any acceptors for hydrogen bonds; sometimes adding a co-crystal former like picrates or triphenylphosphine oxide can help [16].

- Patience and Observation: Do not leave the crystallization vessel unattended for long periods. Watch the process closely and be prepared to change conditions if nucleation does not occur [16].

Problem 3: Inconsistent Crystal Growth and Quality

Observation: Crystals form, but they are small, imperfect, or show high levels of disorder, making them unsuitable for analysis (e.g., X-ray diffraction).

Explanation: The crystal growth process is happening too rapidly or under unstable conditions, not allowing for the orderly addition of molecules to the crystal lattice.

Solutions:

- Slow Down: "Don't hurry." If a synthesis takes months, the crystallization should not be rushed. Slow growth typically produces higher quality crystals [16].

- Use Less Concentrated Solutions: Crystallizing from overly concentrated solutions often leads to poor results. Choose a solvent or mixture where the solute has lower solubility to achieve better control [16].

- Segregate Crystal Phase: In advanced setups like Membrane Distillation Crystallisation (MDC), using in-line filtration to retain crystals within the crystalliser bulk can reduce deposition (scaling) on vessel walls. This allows a consistent supersaturation rate to be sustained, desaturates the solvent via crystal growth, and results in larger, more uniform crystals [8].

- Document Everything: Record all crystallization conditions meticulously. The note "Suitable crystals were obtained by slow evaporation of the solvent" is not helpful for reproducing results [16].

Quantitative Data & Experimental Protocols

Supersaturation Control Parameters

The table below summarizes key parameters and their impact on crystallization outcomes, derived from research data.

| Parameter | Typical Range/Value | Impact on Experiment | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Critical Supersaturation | Minimum vapor saturation for CCN activation | Determines which aerosol particles form cloud droplets; analogous threshold exists for solute nucleation. | [15] |

| Supersaturation at Induction | Increases with concentration rate | Shortens induction time, broadens metastable zone width, favors homogeneous nucleation. | [8] |

| Nucleation Saturation Index (∑) | ∑ = 1.9 for CaCO₃ | Fast nucleation occurs at this level; nuclei attach to surfaces. | [17] |

| Alum Additive (for MAP) | 0 - 1.25 g/100 mL water | Controls crystal habit; higher concentrations yield sharper, needle-like crystals. | [18] |

| MAP Concentration (Seed) | 60 g/100 mL hot water | Creates a highly supersaturated solution for generating seed crystals. | [18] |

| MAP Concentration (Growth) | 45 g/100 mL hot water | A less concentrated solution for growing larger, clearer crystals from seeds. | [18] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Microfluidic Control of CaCO₃ Crystal Growth

This protocol, adapted from research, outlines a method for achieving precise control over nucleation and growth, minimizing scaling.

1. Objective: To nucleate calcium carbonate crystals in a limited area and obtain accurate growth rates of single polymorph crystals under stable concentration conditions [17].

2. Materials (Research Reagent Solutions):

- Microfluidic Device: Fabricated with channels (e.g., 120 µm wide, 45 µm high) [17].

- Precision Flow Controller: A pressure-driven flow control system (e.g., Elveflow OB1 MK3 controller) is critical for stable concentrations [17].

- Syringe Pumps: For introducing reagents, though pressure-driven control is preferred for stability [17].

- Calcium Chloride (CaClâ‚‚) Solution: 2 mM for stable flow, 10 mM for nucleation [17].

- Sodium Carbonate (Na₂CO₃) Solution: 2 mM for stable flow, 10 mM for nucleation [17].

- Deionized Water: For introduction into separate inlets to control mixing [17].

3. Methodology:

- Setup: Assemble the microfluidic device and connect it to the pressure controller and reagent reservoirs [17].

- Stable Flow Establishment: Introduce deionized water into one inlet and 2 mM CaCl₂ and Na₂CO₃ solutions into the other two inlets. This achieves a low, non-nucleating CaCO₃ concentration (e.g., 0.8 mM). The flow controller maintains all flow rates constant [17].

- Nucleation Trigger: Once a stable flow is achieved, switch the reagent inlets to 10 mM CaCl₂ and Na₂CO₃ solutions. This increases the saturation index (∑) to about 1.9, prompting fast nucleation. Nuclei will become visible and attach to the channel surface [17].

- Crystal Growth: After nucleation is observed, stop the flow from auxiliary inlets. The constant, pressure-controlled flow of the 10 mM solutions past the immobilized nuclei provides a stable supersaturation environment for controlled crystal growth. The growth can be monitored for extended periods (e.g., 23 hours) [17].

- Key Consideration: Research has demonstrated that syringe pumps can cause a constant deviation in flow fraction, whereas pressure-driven flow control is essential for maintaining the stable concentration required for precise growth rate measurements [17].

Workflow Visualization & Researcher's Toolkit

Experimental Workflow for Supersaturation Control

The diagram below outlines the logical decision process for managing supersaturation to avoid scaling and achieve controlled growth.

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

The following table details key materials and their functions for controlled crystallization experiments.

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Precision Flow Controller | Pressure-driven systems (e.g., Elveflow OB1) provide superior flow stability over syringe pumps, which is crucial for maintaining constant supersaturation during crystal growth studies [17]. |

| Microfluidic Devices | Provide a confined environment for reagent mixing, nucleation, and growth, allowing for high-precision observation and control of crystallization parameters [17]. |

| Monoammonium Phosphate (MAP) | A common, non-toxic model compound for crystal growth studies. Can be used to grow large, high-quality single crystals or clusters by varying solution conditions [18]. |

| Alum (Potassium Aluminum Sulfate) | An additive used in MAP crystallization to control crystal habit. Increasing the alum concentration changes crystal shape from prismatic to sharp, needle-like spikes [18]. |

| Hydrophobic Vessels (Polypropylene/Teflon) | Prevent solvent from creeping up the walls and causing nucleation outside the main solution, a common problem with hydrophilic glassware [16]. |

| In-line Filtration | Used in systems like MDC to retain crystals in the bulk crystallizer, reducing scaling on walls and promoting controlled growth by maintaining consistent supersaturation [8]. |

| Evocalcet-D4 | Evocalcet-D4, MF:C24H26N2O2, MW:378.5 g/mol |

| Smarca2-IN-2 | Smarca2-IN-2, MF:C16H17N3, MW:251.33 g/mol |

Advanced Techniques for ΔT-Controlled Crystallization in Research and Development

Core Concepts: Understanding ΔT in Thermal Systems

What is Delta T (ΔT) and why is it critical for crystal growth research?

Answer: Delta T (ΔT) represents the temperature difference between two critical points in a system. In crystal growth research, controlling ΔT is fundamental as it directly governs heat transfer rates, which influence crystal nucleation and growth velocity. The formula for calculating ΔT is:

ΔT = T₂ - T₠Where T₂ and T₠are temperatures at two different measurement points [19].

For furnace systems, ΔT is often calculated as the difference between the average internal temperature and the external or room temperature. This is key to understanding the heat output and stability of your system [20]:

ΔT = (Flow Temperature + Return Temperature)/2 - Room Temperature

Example Calculation: If your furnace has an average internal temperature of 70°C and the lab room temperature is 20°C, then ΔT = 70°C - 20°C = 50°C. This scenario is referred to as a "Delta T 50" condition [20].

How does capillary thermostat technology contribute to precise thermal control?

Answer: Capillary thermostats are electromechanical safety devices that provide an external layer of protection for furnaces. They function based on the thermal expansion of a liquid within a sealed capillary system [21].

- Working Principle: A liquid-filled sensing bulb, connected via a capillary tube to an electrical switch, is attached to the furnace's external body. As the surface temperature rises, the liquid expands, mechanically actuating the switch. If a preset temperature limit is reached, the switch opens and safely shuts off power to the furnace [22] [21].

- Safety Function: This mechanism prevents the furnace exterior from reaching dangerously high temperatures, mitigating burn risks and potential damage to the instrument or surrounding materials [22].

- Configurations: Some models offer an optional over-temperature lock-out feature (e.g., Capstat-Dual). This provides a secondary, factory-preset safety cut-out that operates if the primary control switch fails, ensuring fail-safe operation [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Furnace fails to maintain stable ΔT

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unstable temperature or inability to reach setpoint | Capillary thermostat tripping prematurely | Verify external furnace body temperature is below the thermostat's setpoint. Check for poor ventilation around furnace. | Improve airflow around furnace. Relocate capillary sensor if it is in a hotspot. |

| Faulty or damaged capillary sensor | Visually inspect capillary tube and bulb for kinks, cracks, or crushing [21]. | Replace damaged capillary thermostat assembly [22]. | |

| Excessive temperature fluctuations | Incorrect ΔT calculation for system setup | Recalculate ΔT based on actual flow/return temperatures and ambient lab temperature [20]. | Adjust system temperature settings to achieve the correct ΔT for the desired heat output. |

Unexpected furnace shutdown

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Furnace shuts down during operation | External body temperature exceeded capillary thermostat limit [22] | Allow furnace to cool. Check if the thermostat resets automatically. | Ensure the furnace is operated within its specified environmental and thermal limits. |

| Over-temperature lock-out (if equipped) has been activated [21] | Check if the lock-out requires a manual reset. Investigate why the primary control failed. | Address the root cause of the over-temperature event (e.g., controller failure). Reset lock-out if applicable. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My research requires a very specific thermal profile. How can I ensure my furnace's ΔT is calibrated correctly for reproducible crystal growth?

A: Accurate ΔT calibration is fundamental for reproducibility.

- Measure Actual Temperatures: Use calibrated pipe thermometers or sensors to record the actual flow and return temperatures of your furnace's heating system, not just the setpoint [20].

- Monitor Ambient Conditions: Record the stable room temperature in the immediate vicinity of your experiment.

- Calculate True ΔT: Use the formula ΔT = (Flow + Return)/2 - Room Temperature to determine your real-world operating ΔT [20]. Consistently documenting and using this calibrated ΔT ensures your thermal profiles are reproducible across experiments.

Q2: The capillary thermostat on my PVT furnace keeps shutting off the system, halting my long-term experiment. What should I check?

A: This is a critical safety feature being activated. Your investigation should focus on:

- Ventilation: Ensure all vents on the furnace enclosure are completely unobstructed. Dust buildup can be a common cause.

- Sensor Placement: Verify that the capillary thermostat's sensing bulb is firmly and correctly attached to the specified location on the furnace body as per the manufacturer's manual. If it has become dislodged, it may be reading a falsely low temperature.

- Setpoint: Confirm that the thermostat's trip temperature is set appropriately for your experiment and is not set too low for the required internal temperatures.

Q3: For my drug compound crystallization, why is the industry moving towards lower ΔT values in modern systems?

A: The shift to lower ΔT values (e.g., Delta T 50 instead of Delta T 60) is driven by efficiency and control.

- Enhanced Efficiency: Modern systems, like condensing boilers, are designed to operate most efficiently at lower temperatures, reducing energy consumption [20].

- Improved Control: Lower, more stable temperatures can allow for finer control over the crystal growth process, potentially leading to more consistent crystal size and purity, which is critical in pharmaceutical development.

- Real-World Performance: Specifications based on lower ΔT values more accurately reflect the actual performance of contemporary equipment, preventing the selection of undersized equipment that cannot achieve its advertised output [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Capillary Thermostat (e.g., EQ-CT320) | Provides an external, mechanical safety shut-off for the furnace, preventing the external body from reaching hazardous temperatures [22]. |

| Armoured Capillary Tube (Optional) | Offers additional mechanical protection for the capillary tube of the thermostat in crowded or high-traffic lab environments [21]. |

| Pipe Thermometer | Essential tool for empirically measuring the actual flow temperature of the heating system, enabling accurate real-world ΔT calculation [20]. |

| Over-Temperature Lock-out (e.g., CT-DUAL) | A secondary safety switch that provides a factory-preset, fail-safe cut-off in case of primary control failure [21]. |

| Pepluanin A | Pepluanin A, MF:C43H51NO15, MW:821.9 g/mol |

| (S)-GSK-3685032 | (S)-GSK-3685032, MF:C22H24N6OS, MW:420.5 g/mol |

Experimental Protocol: Methodology for ΔT Calibration in Crystal Growth Systems

Aim: To empirically determine the operating Delta T (ΔT) of a crystal growth furnace system to ensure accurate and reproducible thermal profiles.

Procedure:

- System Stabilization: Activate the furnace and set it to the desired process temperature. Allow the system to run for a minimum of 30 minutes, or until all readouts (e.g., internal temperatures, power draw) have stabilized.

- Temperature Measurement: a. Flow Temperature: Attach a calibrated pipe thermometer to the pipe carrying heated media (e.g., water, oil) away from the furnace (the flow line). Record the temperature once stable [20]. b. Return Temperature: Similarly, attach a second thermometer to the pipe returning the media to the furnace (the return line) and record the temperature. c. Ambient Temperature: Place a calibrated room temperature sensor in the immediate vicinity of the furnace, shielded from direct heat radiation. Record the stable room temperature.

- ΔT Calculation: Input the recorded values into the standard formula: ΔT = (Flow Temperature + Return Temperature) / 2 - Ambient Temperature [20].

- Documentation: Record the calculated ΔT, all raw temperature values, and the system setpoint in the experiment's log. This calibrated ΔT value should be used as a key parameter for replicating the experiment.

System Workflow and Diagnostics

Capillary Thermostat Safety Cut-off Logic

Designing Stagnant, Uniform Growth Environments to Minimize Experimental Artifacts

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the most critical parameters to control for a uniform growth environment? The most critical parameters are temperature stability and supersaturation control. Even minor fluctuations can drastically alter crystal growth rates and morphology. Temperature stability should exceed ±0.1°C, and supersaturation must be uniform and stable throughout the growth chamber to prevent localized variations in growth kinetics [23].

How can I minimize crystal-crystal interactions and substrate effects? To minimize these artifacts:

- Use well-separated, ultrafine capillaries instead of flat substrates or fibers to support crystals. This reduces preferred nucleation sites and epitaxial-induced strain [23].

- Ensure low crystal density in the growth chamber. The average crystal separation should be on the scale of millimeters or more to prevent crystals from impeding each other's growth through the vapor-density field [23].

My initial crystals are microcrystals or clusters. How can I optimize conditions to grow larger, single crystals? Optimization is a systematic process [24]:

- Identify initial "hits" from matrix screening.

- Prioritize conditions that produce three-dimensional, polyhedral crystals over needles, plates, or clusters.

- Incrementally refine parameters such as pH, precipitant concentration, and temperature around the initial hit conditions. For example, if a hit occurred at pH 7.0, set up new trials at pH 6.0, 6.2, 6.4, up to 8.0.

What are the signs of temperature gradients or instability in my setup? Signs include inconsistent growth rates across different crystal faces or between experiments run under supposedly identical conditions, and crystals with curved edges or hollowed ends [24] [23]. Direct measurement using multiple calibrated thermistors in the growth chamber is necessary to confirm stability [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Unstable or Inconsistent Crystal Growth Rates

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Temperature fluctuations in the experimental chamber.

- Solution: Use a cooling bath circulator with high stability (exceeding ±0.1°C) and design the growth chamber with a large thermal mass (e.g., a milled metal block) to smooth out short-term temperature variations [23].

- Cause 2: Uncontrolled supersaturation.

- Solution: Implement a dedicated vapor-source chamber with an independent thermoelectric cooler to precisely control the supersaturation (S) in the growth chamber. Actively monitor this parameter throughout the experiment [23].

Problem: Crystal Clusters or Unfavorable Morphologies

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Excessive nucleation density.

- Solution: Optimize the nucleation process by adjusting the degree of undercooling (ΔT). Start with smaller ΔT to favor growth over nucleation. Techniques like matrix seeding can also help control nucleation [24].

- Cause 2: Physical interactions with the substrate.

- Solution: Transition from growth on a flat substrate or fiber to a support-free or capillary-based method. This minimizes edge-effects and strain that can influence crystal habit [23].

Problem: Poor Diffraction Quality from Seemingly Well-Grown Crystals

Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Internal disorder or twinning not visible externally.

- Solution: Use a dissecting microscope with polarized light to check the crystal's optical properties. Weak birefringence or irregular extinction can indicate internal disorder. Focus optimization efforts on conditions that produce crystals with strong, uniform optical properties [24].

- Cause 2: Inadequate optimization of chemical parameters.

- Solution: Systematically explore additives, such as detergents or specific ligands, which can enhance crystal perfection by interacting with the protein surface and promoting more ordered packing [24].

Quantitative Data and Relationships

The relationship between undercooling (ΔT) and crystal texture is a key quantitative aspect of crystallization kinetics. The following table summarizes how the degree of undercooling influences the competition between nucleation and growth, which in turn determines final crystal texture [25].

Table 1: Influence of Undercooling (ΔT) on Crystallization Kinetics and Texture

| Degree of Undercooling (ΔT) | Nucleation vs. Growth | Resulting Crystal Texture | Typical Experimental Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small to Moderate ΔT | Growth dominates over nucleation | Coarser crystallinity; larger, fewer crystals | Slow cooling; vapor diffusion with small equilibrium disturbances |

| High ΔT | Nucleation dominates over growth | Numerous small crystals (microcrystals or showers) | Rapid cooling; fast evaporation; high supersaturation |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key components used in formulating crystallization experiments, particularly for biological macromolecules [24].

Table 2: Key Reagents for Crystal Growth Optimization

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Precipitants (e.g., PEG, Salts) | Drives the sample out of solution, promoting supersaturation and nucleation. | Polyethylene glycol (PEG) of various molecular weights is used to create a crowding effect. |

| Buffers | Maintains a stable and precise pH level, critical for macromolecule stability. | A trial might systematically vary pH around a hit condition from 6.0 to 8.0 in 0.2 unit increments. |

| Additives / Ligands | Enhances crystal packing or stability by binding to the target macromolecule. | Detergents, small molecules, or ions like Mg²⺠or Ca²⺠are added to improve crystal order and diffraction. |

Experimental Protocol: Systematic Optimization via Incremental Parameter Variation

This protocol outlines a standard method for refining initial crystallization "hits" to obtain high-quality crystals [24].

Objective: To improve crystal size, morphology, and diffraction quality by systematically varying the parameters of initial crystallization conditions.

Procedure:

- Parameter Identification: Identify all chemical and physical parameters from the initial screening hit (e.g., precipitant type and concentration, pH, buffer type, temperature, additive presence).

- Solution Formulation: Prepare a matrix of new crystallization solutions. Each parameter should be varied incrementally while keeping others constant.

- Example: If the initial hit was 20% PEG 8000, 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.0, set up trials with PEG concentrations of 15%, 17.5%, 20%, 22.5%, and 25%, and pH values of 6.4, 6.6, 6.8, 7.0, 7.2, 7.4, and 7.6.

- Crystallization Trial Setup: Set up new crystallization trials (e.g., via vapor diffusion) using the newly formulated solutions. It is crucial to use a consistent sample volume and methodology.

- Observation and Evaluation: Monitor the trials regularly. Evaluate crystals based on size, three-dimensional morphology, and optical properties (using polarized light).

- Iteration: Use the best outcomes from this first round of optimization as a new starting point for further fine-tuning.

Methodology: Capillary Cryostat for Stagnant, Uniform Growth

This methodology details the use of a specialized instrument designed to minimize common experimental artifacts [23].

Objective: To grow ice crystals in a highly controlled, stagnant, and uniform environment, minimizing temperature gradients, substrate interactions, and crystal-crystal interference.

Apparatus Setup (Capillary Cryostat CC2):

- Growth Chamber (GC): A central, gold-plated copper chamber with a large thermal mass for temperature stability (fluctuations < 50 mK).

- Capillary Support: Three pure-silica glass capillaries, well-separated and extending from the ceiling of the GC. Crystals grow at the tips, minimizing contact and substrate effects.

- Vapor-Source Chambers (VSCs): Two independent chambers (above and below the GC), each containing a vapor source (ice) on a thermoelectric cooler (TEC). They allow precise and rapid control of GC supersaturation.

- Vacuum Insulation: The entire experimental chamber is surrounded by a vacuum-shroud box (< 10â»âµ Torr) for thermal isolation.

Experimental Workflow:

- Sample Loading: A crystal is nucleated at the tip of a capillary using a chosen ice-nucleation method.

- Condition Stabilization: The bath circulator and VSC TECs are set to achieve the target temperature (TEC) and supersaturation (via TVS) in the GC.

- Crystal Growth: The crystal grows affixed to the capillary in a stagnant, uniform environment. Its orientation can be manipulated to measure the growth rate of specific faces.

- Condition Modulation: The supersaturation can be rapidly changed by switching the active VSC using a sliding valve.

Core Principles and Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the core goal of minimizing artifacts and the key design principles required to achieve it.

The systematic process for moving from an initial discovery to optimized crystal growth conditions is outlined in the workflow below.

Protocols for Independent Control of ΔT and Absolute Temperature Parameters

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: How can I resolve inconsistent crystal growth rates despite a stable absolute temperature?

Answer: Inconsistent growth rates with stable absolute temperature often result from uncontrolled or unmeasured ΔT (undercooling). The growth velocity (V) is governed by the driving force, Δμ(T), which is a function of ΔT, and the kinetic attachment term, k(T) [26].