Machine Learning vs. DFT Formation Energy: The New Frontier in Predicting Material Synthesizability

Accurately predicting whether a theoretical material can be synthesized is a critical challenge in accelerating the discovery of new functional compounds, particularly in drug development and materials science.

Machine Learning vs. DFT Formation Energy: The New Frontier in Predicting Material Synthesizability

Abstract

Accurately predicting whether a theoretical material can be synthesized is a critical challenge in accelerating the discovery of new functional compounds, particularly in drug development and materials science. While Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations of formation energy have long been the standard for assessing thermodynamic stability, they often fall short as a reliable proxy for experimental synthesizability. This article explores the emerging paradigm where machine learning (ML) models are surpassing traditional DFT-based metrics. We provide a comprehensive analysis covering the foundational principles of both approaches, detailed methodologies for implementation, strategies to overcome inherent limitations, and a rigorous comparative validation. By synthesizing insights from cutting-edge research, this article serves as a guide for researchers and scientists to navigate and leverage these powerful, complementary tools for rational materials design.

The Synthesizability Challenge: Why DFT Formation Energy Isn't Enough

Defining the Synthesizability Gap in Materials Discovery

The discovery of new functional materials is fundamental to technological progress, from developing more efficient energy storage systems to creating novel pharmaceuticals. For decades, density functional theory (DFT) has served as the computational workhorse for predicting material properties and stability, with formation energy and energy above the convex hull (Ehull) serving as primary metrics for thermodynamic stability assessment. However, a significant disconnect exists between these computational stability metrics and a material's actual synthesizability in laboratory conditions—a critical shortfall known as the synthesizability gap. This gap represents one of the most pressing challenges in computational materials discovery, where millions of theoretically predicted compounds with excellent properties never transition from digital simulations to physical reality due to synthesizability limitations. The emergence of machine learning (ML) approaches offers promising pathways to bridge this gap by learning complex patterns from existing experimental data that extend beyond simple thermodynamic stability. This guide provides an objective comparison of these competing methodologies for synthesizability assessment, examining their respective capabilities, limitations, and practical implementation for researchers navigating the complex landscape of materials discovery.

Quantitative Comparison: ML vs. DFT for Synthesizability Assessment

Table 1: Performance Metrics of ML and DFT Approaches for Synthesizability Prediction

| Evaluation Metric | Traditional DFT Metrics | ML-Based Synthesizability Prediction | Specialized ML Frameworks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Quantum mechanics-based energy calculation | Pattern recognition from experimental data | Domain-adapted large language models |

| Primary Predictor | Energy above convex hull (Ehull) | Synthesizability classification score | Multi-task prediction (synthesizability, method, precursors) |

| Typical Accuracy | 74.1% (Ehull ≥0.1 eV/atom) [1] | 87.9% (PU learning on 3D crystals) [1] | 98.6% (CSLLM framework) [1] |

| Kinetic Stability | 82.2% (Phonon frequency ≥ -0.1 THz) [1] | Not directly assessed | Implicitly learned from experimental data |

| Precursor Recommendation | Not available | Not available | 80.2% success (Precursor LLM) [1] |

| Synthetic Method Prediction | Not available | Not available | 91.0% accuracy (Method LLM) [1] |

| Computational Cost | High (hours to days per structure) | Low (seconds once trained) | Moderate (inference time) |

| Key Limitation | Poor correlation with experimental synthesizability [1] | Requires carefully curated datasets [2] | Limited to trained chemical spaces |

Table 2: Prospective Validation Performance on Novel Materials

| Validation Approach | Methodology | Performance Outcome | Real-World Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal Validation | Train on pre-2015 data, test on post-2019 materials [3] | 88.6% true positive rate [3] | High prediction accuracy for novel compositions |

| Prospective Discovery | Screening of 554,054 theoretical candidates [4] | 92,310 identified as synthesizable [4] | Effective prioritization for experimental efforts |

| Complex Structure Generalization | Prediction on structures exceeding training complexity [1] | 97.9% accuracy [1] | Robust performance on challenging candidates |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

DFT-Based Stability Assessment Protocol

The conventional approach to evaluating synthesizability relies on DFT-computed thermodynamic stability metrics. The standard workflow involves:

- Structure Relaxation: Geometry optimization of the candidate crystal structure using DFT packages such as VASP [5] with appropriate exchange-correlation functionals (typically PBE [5] or other GGA variants).

- Formation Energy Calculation: Computation of the energy required to form the compound from its constituent elements in their standard states: ΔEf = Etotal - Σn_iE_i, where Etotal is the total energy of the compound, and ni and E_i are the number and reference energies of constituent elements [3].

- Energy Above Hull Calculation: Determination of the energy difference between the compound and the most stable combination of competing phases at the same composition via convex hull construction [6] [3]. Structures with Ehull ≤ 0.02-0.08 eV/atom are typically considered potentially stable [3].

- Kinetic Stability Assessment: Phonon spectrum calculation to identify imaginary frequencies that indicate dynamical instabilities [1]. This computationally expensive step is often omitted in high-throughput screenings.

This protocol, while physically grounded, fails to account for experimental factors such as precursor selection, kinetic barriers, and synthesis route feasibility [1] [3].

Machine Learning Synthesizability Prediction

ML approaches address DFT's limitations by learning from experimental data. The CSLLM framework exemplifies the state-of-the-art methodology [1]:

Dataset Curation:

- Positive Samples: 70,120 synthesizable crystal structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [1], filtered to ordered structures with ≤40 atoms and ≤7 elements.

- Negative Samples: 80,000 non-synthesizable structures identified from 1,401,562 theoretical structures using a pre-trained PU learning model with CLscore <0.1 threshold [1].

- Dataset Balancing: Approximately 1:1 ratio of synthesizable to non-synthesizable structures ensures model robustness.

Crystal Structure Representation:

- Development of "material string" representation: SP | a, b, c, α, β, γ | (AS1-WS1[WP1...] ... ) | SG, where SP is space group, a,b,c,α,β,γ are lattice parameters, AS is atomic symbol, WS is Wyckoff symbol, WP is Wyckoff position, and SG is space group [1].

- This text-based representation enables efficient processing by large language models while preserving essential crystal symmetry information.

Model Architecture and Training:

- Implementation of three specialized LLMs: Synthesizability LLM, Method LLM, and Precursor LLM.

- Fine-tuning of base LLMs on the curated dataset using the material string representation.

- Domain-focused fine-tuning aligns linguistic features with materials science knowledge, refining attention mechanisms and reducing hallucinations [1].

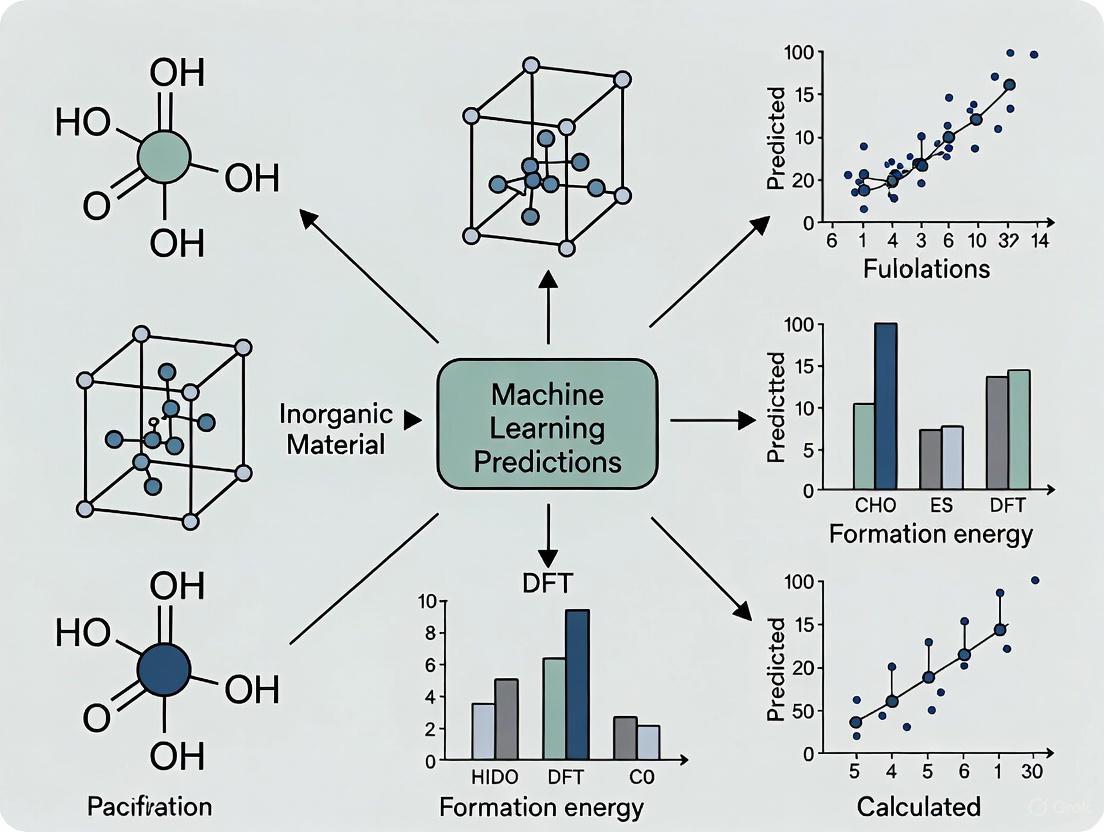

Diagram 1: Comparison of DFT and ML workflows for synthesizability assessment. The ML pathway provides more comprehensive synthesis guidance.

Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning Implementation

For material classes with limited negative examples, PU learning provides an effective alternative:

- Label Assignment: Experimental materials from ICSD tagged as positive; theoretical materials from MP, OQMD, and AFLOW treated as unlabeled [2] [3].

- Feature Engineering: Utilization of composition-based descriptors, structural features, or crystal graph representations [2].

- Model Training: Implementation of biased learning where unlabeled samples are treated as negative during training, with expectation-maximization to estimate true labels [2].

- Probability Calibration: Output of synthesizability scores (CLscore or similar) representing likelihood of successful synthesis [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Databases for Synthesizability Research

| Tool/Database | Type | Primary Function | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Project (MP) [3] | Database | Repository of DFT-computed material properties & structures | REST API / Python SDK |

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [1] | Database | Curated experimental crystal structures | Subscription / Limited access |

| Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) [5] | Software | DFT calculation for structure relaxation & energy computation | Academic license |

| Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Network (CGCNN) [3] | ML Model | Property prediction from crystal structures | Open source |

| Fourier-Transformed Crystal Properties (FTCP) [3] | Representation | Crystal structure representation for ML | Implementation in research code |

| Matbench Discovery [6] | Benchmark | Standardized evaluation of ML energy models | Python package |

| CSLLM Framework [1] | ML Model | Synthesizability, method & precursor prediction | Research implementation |

| Antitubercular agent-44 | Antitubercular agent-44|C16H13F3N4O6S2|RUO | Antitubercular agent-44 is a research compound with the formula C16H13F3N4O6S2, intended for investigational use against tuberculosis. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| ZL-12A probe | ZL-12A probe, MF:C24H23N3O2, MW:385.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The synthesizability gap remains a critical bottleneck in materials discovery, with DFT-based thermodynamic stability metrics showing limited correlation (74.1% accuracy) with experimental synthesizability. Machine learning approaches, particularly specialized frameworks like CSLLM achieving 98.6% accuracy, demonstrate superior capability by incorporating complex patterns learned from experimental data. The most promising path forward lies in hybrid approaches that combine the physical grounding of DFT with the pattern recognition power of ML. As benchmark frameworks like Matbench Discovery [6] continue to standardize evaluation metrics, the field moves closer to reliable synthesizability prediction that can significantly accelerate the discovery and deployment of novel functional materials across scientific and industrial applications.

The Synthesizability Challenge in Materials Science

A central challenge in materials science is predicting whether a computationally designed compound can be successfully synthesized in a laboratory. For years, Density Functional Theory (DFT) has been the cornerstone for assessing this synthesizability, primarily by calculating a material's thermodynamic stability. The most common metric for this is the energy above the convex hull (Ehull), where a value of 0 eV/atom indicates a material is thermodynamically stable at 0 K and thus a promising candidate for synthesis [3] [7]. While this approach has successfully guided the discovery of many new materials, it is an imperfect predictor. A significant number of metastable compounds (with Ehull > 0) are experimentally synthesizable, while many DFT-stable compounds have never been synthesized, highlighting a gap that pure thermodynamic stability cannot explain [7]. This gap has motivated the development of machine learning (ML) as a powerful alternative for synthesizability assessment.

Quantitative Comparison: DFT vs. Machine Learning

The table below summarizes a direct, quantitative comparison between a traditional DFT-based stability filter and a modern machine learning model for predicting synthesizability.

| Assessment Method | Core Metric / Model | Reported Accuracy | Key Limitations / Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional DFT | Energy above convex hull (E_hull) < 0.1 eV/atom [1] | 74.1% [1] | Provides quantum-mechanical rigor but ignores kinetic factors, synthesis conditions, and precursors [7]. |

| Machine Learning | Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM) [1] | 98.6% [1] | Learns complex patterns from experimental data, directly predicts synthesizability, methods, and precursors [1]. |

Beyond final accuracy, their computational workflows and resource demands differ significantly. The following diagram illustrates the core protocols for both DFT and ML-based formation energy prediction, which is the foundation of stability assessment.

Experimental Protocols for Stability Assessment

1. DFT-Based Stability Workflow The traditional protocol involves several computationally intensive steps [8] [7]:

- Input: A crystal structure file (e.g., POSCAR or CIF) defines the atomic positions and lattice parameters.

- Energy Calculation: A DFT simulation (using software like Quantum ESPRESSO) calculates the total energy of the target crystal. This often requires careful selection of an exchange-correlation functional (e.g., PBE, HSE06) and, for systems with localized electrons, a Hubbard U parameter [8].

- Convex Hull Construction: The formation energy of the target compound and all other known phases in its chemical space are calculated. The convex hull is constructed from the most stable phases at different compositions. The energy above the hull (E_hull) is computed as the energy difference between the target compound and its linear combination of stable phases on the hull [7].

- Output & Decision: The E_hull value is used as a proxy for synthesizability, with lower values (especially < 0.1 eV/atom) considered promising [1].

2. ML-Based Formation Energy Workflow ML models offer a faster, data-driven alternative for the critical step of formation energy prediction [9]:

- Input: The same crystal structure file (POSCAR/CIF) is used as the starting point.

- Featurization: The atomic structure is transformed into a numerical representation. Common methods include graph representations (where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges) or the incorporation of elemental features (e.g., atomic radius, electronegativity, valence electrons) to improve generalization to new elements [9].

- Model Inference: A pre-trained model (e.g., a Graph Neural Network like SchNet or MACE) processes the features to predict the formation energy directly, bypassing the need for explicit DFT calculations [9].

- Output: The model outputs a predicted formation energy, which can then be used to derive E_hull or fed into specialized synthesizability classifiers like CSLLM [1].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below catalogs key computational "reagents" — software, databases, and models — essential for research in this field.

| Name | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum ESPRESSO [8] | Software Suite | Performs first-principles DFT calculations for electronic structure and energy determination. |

| Materials Project (MP) Database [3] [9] | Database | Provides a vast repository of pre-computed DFT data for known and hypothetical materials, essential for training ML models and constructing phase hulls. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [9] [1] | Machine Learning Model | A class of models that operates directly on atomic graph structures to predict material properties like formation energy with high accuracy. |

| Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM) [1] | Specialized LLM | A fine-tuned large language model that uses text representations of crystals to predict synthesizability, synthetic methods, and precursors with high accuracy. |

Density Functional Theory (DFT) has long served as the cornerstone of computational materials design, enabling the prediction of material properties from first principles. This quantum-mechanics-based approach provides efficient and reliable estimates of ground-state materials properties at zero Kelvin, forming the foundation for the third paradigm of materials research [10]. However, the very principle that makes DFT computationally tractable—its focus on the ground state—also constitutes its most significant limitation for practical materials science. Real-world materials synthesis and application invariably occur at non-zero temperatures and involve complex kinetic pathways that DFT, in its standard implementation, struggles to capture.

The central challenge lies in the fact that temperature effects are computationally demanding to simulate from first principles, increasing the cost of simulations by several orders of magnitude [10]. This limitation is particularly problematic for predicting synthesizability, as the experimental synthesis of materials is a complex process influenced by thermodynamic conditions, kinetic barriers, and precursor selection—factors that extend far beyond ground-state thermodynamics [1]. As we transition toward a new paradigm that harnesses machine learning (ML) and accumulated data, researchers are now developing innovative approaches that bypass these fundamental DFT limitations, particularly for the critical task of predicting which computationally designed materials can actually be synthesized in the laboratory.

Quantitative Comparison: DFT Versus Machine Learning Performance

The performance gap between traditional DFT-based assessments and modern ML approaches becomes evident when examining their predictive accuracy for synthesizability and related properties. The following tables summarize key quantitative comparisons from recent studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

| Prediction Method | Accuracy | Key Limitation | Data Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT (Energy Above Hull ≥0.1 eV/atom) [1] | 74.1% | Only accounts for thermodynamic stability | 1-2 DFT calculations per structure |

| DFT (Phonon Frequency ≥ -0.1 THz) [1] | 82.2% | Accounts for kinetic stability but computationally expensive | Extensive phonon calculations |

| Crystal Synthesis LLM (CSLLM) [1] | 98.6% | Requires balanced training data | 150,120 crystal structures |

| Hybrid DFT-ML (GPR on reaction free energies) [10] | Surpasses explicit DFT | Limited experimental reference data needed | 38 metal oxide reduction temperatures |

Table 2: ML Model Performance for Formation Energy Prediction

| Model Architecture | Application Context | Performance | Generalization Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) with Elemental Features [9] | Formation energy prediction with unseen elements | Low mean absolute error | Effective even with 10% of elements excluded from training |

| SchNet [9] | Molecular energy prediction | MAE predominantly within ±0.1 eV/atom | Invariant to molecular orientation and atom indexing |

| MACE [9] | Materials property prediction | Strong force predictions (MAE within ±2 eV/Å) | Equivariant message passing for enhanced power |

Methodological Approaches: From DFT to Machine Learning Workflows

The DFT Foundation and Its Thermodynamic Limitations

Traditional DFT approaches to synthesizability rely primarily on thermodynamic stability metrics derived from zero-Kelvin calculations. The standard methodology involves computing the formation enthalpy of a compound using the formula:

[ {\Delta }{\mathrm{f}}{H}{{\mathrm{M}}{\mathrm{x}}{\mathrm{O}}{\mathrm{y}}}^{\mathrm{DFT}}(T=0\,\,{\mathrm{{K}}}\,)={E}{{\mathrm{M}}{\mathrm{x}}{\mathrm{O}}{\mathrm{y}}}^{\,\mathrm{DFT}\,}-x{E}{\mathrm{M}}^{\,\mathrm{DFT}\,}-\frac{y}{2}{E}{{{\mathrm{O}}{2}}}^{\,\mathrm{DFT}\,} ]

where ({E}{{\mathrm{M}}{\mathrm{x}}{\mathrm{O}}{\mathrm{y}}}^{\,\mathrm{DFT}\,}), ({E}{\mathrm{M}}^{\,\mathrm{DFT}\,}), and ({E}{{{\mathrm{O}}{2}}}^{\,\mathrm{DFT}\,}) are the DFT energies of the metal oxide, base metal, and oxygen molecule, respectively [10]. The energy above the convex hull—the deviation from the most stable combination of elements at specific conditions—serves as the primary synthesizability metric, with values below 0.1 eV/atom often considered potentially synthesizable.

This approach fails to account for the crucial role of entropy in real-world synthesis. At zero Kelvin, the entropy term vanishes, and Gibbs free energy becomes identical to enthalpy [10]. In experimental synthesis, however, the entropy contribution (TS) can dominate, particularly for reactions involving gas phases with high entropy. This fundamental disconnect between the DFT modeling paradigm and experimental conditions explains why numerous structures with favorable formation energies remain unsynthesized, while various metastable structures with less favorable formation energies are successfully synthesized [1].

Machine Learning Solutions for Synthesizability Prediction

Machine learning approaches address DFT's limitations by learning directly from experimental synthesis data rather than relying solely on thermodynamic principles. The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM) framework exemplifies this paradigm shift, utilizing three specialized LLMs to predict synthesizability, synthetic methods, and suitable precursors [1].

The critical innovation lies in the data representation and training methodology. These models are trained on a balanced dataset comprising 70,120 synthesizable crystal structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) and 80,000 non-synthesizable structures identified through positive-unlabeled learning [1]. Instead of relying on DFT-calculated energies, the system uses a text representation called "material string" that integrates essential crystal information in a concise format suitable for LLM processing.

Diagram 1: Contrasting approaches for synthesis prediction. ML methods using experimental data significantly outperform DFT's thermodynamics-only approach.

Integrated Workflows: Bridging DFT and Machine Learning

The most promising approaches combine the physical insights from DFT with the pattern recognition capabilities of ML. A representative example is the synthesizability-driven crystal structure prediction (CSP) framework, which integrates symmetry-guided structure derivation with machine learning [11]. This methodology proceeds through three key steps:

Structure Derivation: Generating candidate structures via group-subgroup relations from synthesized prototypes, ensuring atomic spatial arrangements of experimentally realizable materials.

Subspace Filtering: Classifying structures into configuration subspaces labeled by Wyckoff encodes and filtering based on the probability of synthesizability predicted by ML models.

Structure Relaxation and Evaluation: Applying structural relaxations to candidates in promising subspaces, followed by final synthesizability evaluations [11].

This integrated workflow successfully identified 92,310 potentially synthesizable structures from 554,054 candidates initially predicted by the Graph Networks for Materials Exploration (GNoME) project [11].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Modern Materials Prediction

Table 3: Key Computational Tools for Synthesis Prediction

| Tool/Category | Primary Function | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) [5] | DFT calculations using PAW potentials | First-principles evaluation of formation energies and structural properties |

| Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) [10] | Non-parametric Bayesian modeling | Predicting temperature-dependent reaction free energies from limited data |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [9] | Learning representation of graph-structured data | Predicting formation energies for compounds with unseen elements |

| Crystal Synthesis LLM (CSLLM) [1] | Text-based crystal structure analysis | Synthesizability classification, method recommendation, precursor identification |

| Wyckoff Encode [11] | Symmetry-based structure representation | Efficient configuration space sampling for synthesizable candidates |

| Deep Potential (DP) [12] | Neural network potentials | Large-scale molecular dynamics with DFT-level accuracy |

Case Study: MAX Phase Discovery Through Integrated Workflows

The application of these integrated approaches is exemplified by recent work on MAX phase materials discovery. Researchers systematically explored 9,660 M₂AX, M₃AX₂, and M₃A₂X structures with hexagonal symmetry, incorporating not only traditional carbon and nitrogen X-elements but also boron, oxygen, phosphorus, sulfur, and silicon [5].

The methodology combined high-throughput DFT calculations with machine learning: after creating structural descriptors based on element distances and physical properties, ML models filtered promising candidates before proceeding to more computationally intensive phonon calculations and dynamic stability assessments [5]. This integrated approach successfully predicted thirteen synthesizable compounds, demonstrating how ML can guide DFT toward the most promising regions of chemical space.

Diagram 2: Workflow for synthesizability-driven crystal structure prediction, combining symmetry guidance with ML filtering [11].

The critical shortcomings of DFT—its inherent zero-Kelvin limitation and inadequate treatment of real-world synthesis factors—are being systematically addressed through hybrid approaches that integrate physical principles with data-driven machine learning. While DFT continues to provide essential foundational insights into material thermodynamics, the superior performance of ML models in predicting synthesizability (98.6% accuracy for CSLLM versus 74.1% for formation energy criteria) demonstrates a fundamental shift in materials design paradigms [1].

The most promising path forward lies not in abandoning DFT, but in developing integrated workflows that leverage its strengths while compensating for its limitations. By using ML to guide DFT calculations toward chemically plausible and synthesizable regions of materials space, researchers can significantly accelerate the discovery of novel functional materials. As these approaches mature, the gap between computational prediction and experimental realization will continue to narrow, ushering in a new era of data-driven materials discovery that effectively bridges the divide between quantum mechanics at zero Kelvin and practical synthesis in the laboratory.

Machine Learning as a Paradigm Shift in Data-Driven Synthesizability Prediction

Predicting whether a hypothetical material or molecule can be successfully synthesized remains one of the most significant challenges in materials science and drug discovery. Traditional approaches have relied heavily on density functional theory (DFT) to calculate thermodynamic stability metrics, particularly formation energy and energy above the convex hull (E$__{hull}$), as proxies for synthesizability. While these DFT-based methods provide valuable thermodynamic insights, they exhibit fundamental limitations as they often ignore critical kinetic and experimental factors influencing synthesis outcomes [7]. The emergence of machine learning (ML) paradigms offers a transformative approach by learning complex patterns from existing experimental and computational data, enabling more accurate and comprehensive synthesizability predictions that extend beyond thermodynamic considerations alone.

This comparison guide objectively evaluates the performance of modern machine learning approaches against traditional DFT-based methods for synthesizability assessment. By examining experimental data, methodological frameworks, and application-specific case studies, we provide researchers with a clear understanding of the capabilities and limitations of each paradigm, facilitating informed selection of appropriate methodologies for specific research contexts in materials science and pharmaceutical development.

Fundamental Limitations of DFT-Based Synthesizability Assessment

Thermodynamic Stability as an Incomplete Proxy

DFT calculations provide zero-Kelvin energetic stability metrics that have traditionally served as primary screening tools for synthesizability predictions. The energy above the convex hull (E$_{hull}$) describes a compound's thermodynamic stability relative to competing phases, with materials at E$_{hull}$ = 0 eV/atom considered DFT-stable [7]. However, significant evidence demonstrates that this thermodynamic approach presents an incomplete picture of synthesizability:

- Metastable Synthesizable Materials: Approximately half of experimentally reported compounds in the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) are metastable (unstable at zero Kelvin yet synthesizable) with a median E$__{hull}$ of 22 meV/atom [7].

- Stable Unreported Materials: Many compounds with low E$__{hull}$ values remain unreported and are presumed unsynthesizable despite favorable thermodynamics [7].

- Amorphous Limit Constraint: Research indicates that polymorphs with E$__{hull}$ greater than their corresponding amorphous phase are likely unsynthesizable, though the converse is not necessarily true [7].

Practical Limitations in Computational Screening

Beyond theoretical limitations, DFT approaches face significant practical constraints in high-throughput screening scenarios:

- Computational Expense: DFT calculations remain computationally demanding, particularly for complex systems with large unit cells or numerous atomic configurations [13].

- Temperature Neglect: Standard DFT calculations ignore temperature-dependent entropic effects that significantly influence synthesis outcomes at experimental conditions [3].

- Kinetic Factor Exclusion: DFT cannot adequately capture kinetic barriers and pathway dependencies that fundamentally determine synthesis success [14].

These limitations have motivated the development of ML approaches that can learn synthesizability criteria directly from experimental data rather than relying solely on thermodynamic proxies.

Machine Learning Paradigms for Synthesizability Prediction

Key Methodological Frameworks

Machine learning approaches for synthesizability prediction employ diverse representation learning strategies and model architectures to capture complex structure-synthesis relationships:

Table 1: Comparison of ML Approaches for Synthesizability Prediction

| Method | Representation | Key Features | Reported Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Networks (CGCNN) [3] | Crystal graphs encoding atomic properties and bonds | Captures periodicity through multiple edges between nodes | MAE: 0.077 eV/atom (formation energy) |

| Fourier-Transformed Crystal Properties (FTCP) [3] | Combines real-space and reciprocal-space features | Incorporates elemental property vectors and discrete Fourier transform | 82.6% precision, 80.6% recall (ternary crystals) |

| Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models (CSLLM) [1] | Material string text representation | Specialized LLMs for synthesizability, methods, and precursors | 98.6% accuracy (synthesizability classification) |

| Convolutional Encoder on Voxel Images [15] | 3D color-coded voxel images of crystals | Learns structural and chemical patterns from visual representations | Accurate classification across crystal types |

| Retrosynthetic Planning with Reaction Prediction [14] | Molecular structures with round-trip validation | Combines retrosynthetic planners with forward reaction prediction | Tanimoto similarity-based round-trip score |

Advanced Workflows: The CSLLM Framework

The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models (CSLLM) framework represents a significant advancement in synthesizability prediction, employing three specialized LLMs for distinct prediction tasks [1]:

- Synthesizability LLM: Classifies whether a crystal structure is synthesizable (98.6% accuracy)

- Method LLM: Predicts appropriate synthetic methods (solid-state or solution)

- Precursor LLM: Identifies suitable synthetic precursors

This framework was trained on a balanced dataset of 70,120 synthesizable crystal structures from ICSD and 80,000 non-synthesizable structures identified through positive-unlabeled learning, demonstrating exceptional generalization even to complex structures with large unit cells [1].

Molecular Synthesizability: The Round-Trip Score Framework

For molecular synthesizability in drug discovery, a novel three-stage approach addresses limitations of traditional Synthetic Accessibility (SA) scores [14]:

- Retrosynthetic Planning: Predicts synthetic routes for target molecules using retrosynthetic planners

- Reaction Simulation: Uses forward reaction prediction models to simulate synthetic routes

- Round-Trip Validation: Calculates Tanimoto similarity between original and reproduced molecules

This approach provides a more rigorous assessment of synthesizability by ensuring that predicted synthetic routes can actually reconstruct target molecules from commercially available starting materials [14].

Performance Comparison: ML vs. DFT-Based Approaches

Quantitative Accuracy Metrics

Direct performance comparisons demonstrate the superior predictive capability of ML approaches over traditional DFT-based methods:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

| Method | Prediction Task | Accuracy/Precision | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFT Stability (E$__{hull}$ ≤ 0 eV/atom) [7] | Thermodynamic synthesizability | ~50% correlation with experimental reports | Misses metastable synthesizable compounds |

| DFT Amorphous Limit [7] | Necessary condition for synthesizability | Identifies unsynthesizable compounds above limit | Cannot identify synthesizable compounds below limit |

| CSLLM Framework [1] | Synthesizability classification | 98.6% accuracy | Requires extensive training data |

| FTCP with Deep Learning [3] | Ternary crystal synthesizability | 82.6% precision, 80.6% recall | Limited to specific composition spaces |

| Retrosynthetic Round-Trip [14] | Molecular synthesizability | Tanimoto similarity metric | Computationally intensive for large libraries |

Case Study: Half-Heusler Compounds Prediction

A hybrid approach combining DFT stability with composition-based ML features demonstrated significant advantages in predicting synthesizability of ternary 1:1:1 half-Heusler compounds [7]. The model achieved cross-validated precision of 0.82 and recall of 0.82, identifying 39 stable compositions predicted as unsynthesizable and 62 unstable compositions predicted as synthesizable - findings that could not be made using DFT stability alone [7].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Dataset Curation for ML Models

The accuracy of ML synthesizability predictors depends critically on rigorous dataset construction:

- Positive Examples: Experimentally confirmed synthesizable crystals from databases like ICSD (70,120 structures in CSLLM) [1]

- Negative Examples: Non-synthesizable structures identified through positive-unlabeled learning models (80,000 structures in CSLLM) [1]

- Compositional Balance: Ensuring representative coverage across elemental compositions and crystal systems

- Temporal Splitting: Training on older data and testing on recently discovered compounds to validate predictive capability [3]

Feature Engineering and Representation Learning

Different ML approaches employ distinct strategies for representing crystal structures:

- Graph Representations: CGCNN and ALIGNN model crystals as graphs with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges [3]

- Voxel Images: 3D pixel-wise images color-coded by chemical attributes enable convolutional feature learning [15]

- Material Strings: Compact text representations incorporating lattice parameters, space groups, and atomic coordinates [1]

- Elemental Features: Incorporation of physicochemical atomic properties (electronegativity, atomic radius, etc.) improves out-of-distribution generalization [9]

Model Training and Validation Protocols

Robust ML model development requires careful validation strategies:

- k-Fold Cross-Validation: Assessing model stability across different data splits

- Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation: Particularly for limited datasets [16]

- Temporal Validation: Testing on compounds discovered after training period [3]

- Out-of-Distribution Testing: Evaluating performance on chemically distinct compounds [9]

Domain-Specific Applications

Inorganic Crystal Discovery

ML synthesizability predictors have enabled large-scale screening of hypothetical inorganic crystals. The CSLLM framework identified 45,632 synthesizable candidates from 105,321 theoretical structures, dramatically accelerating the discovery pipeline [1].

High-Entropy Materials

For high-entropy oxides (HEOs), ML interatomic potentials (MLIPs) like MACE enable efficient screening of vast compositional spaces by calculating mixing enthalpies and entropy descriptors at DFT-level accuracy but fraction of the cost [13].

Pharmaceutical Drug Design

In drug discovery, ML approaches address the critical trade-off between pharmacological properties and synthesizability, where molecules with optimal binding predictions often prove unsynthesizable using traditional medicinal chemistry approaches [14].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Synthesizability Research

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Synthesizability Prediction

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Project Database [3] | Computational database | Provides DFT-calculated formation energies and structures for >130,000 materials | Public API |

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [1] | Experimental database | Curated repository of experimentally synthesized crystal structures | Subscription |

| Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD) [7] | Computational database | DFT calculations for hypothetical and reported compounds | Public access |

| Python Materials Genomics (pymatgen) [3] | Python library | Materials analysis and workflow management | Open source |

| Atomistic Line Graph Neural Network (ALIGNN) [17] | ML model | Predicts formation energy with bond angle information | Open source |

| CLEASE Code [13] | Software tool | Constructs special quasi-random structures for alloy modeling | Open source |

The evidence comprehensively demonstrates that machine learning represents a paradigm shift in synthesizability prediction, outperforming traditional DFT-based approaches across multiple metrics including accuracy, computational efficiency, and practical utility. ML models achieve this superior performance by learning complex synthesizability patterns directly from experimental data rather than relying solely on thermodynamic proxies.

However, the most promising path forward lies in hybrid approaches that integrate the physical insights from DFT with the pattern recognition capabilities of ML. As demonstrated by successful applications in half-Heusler compounds [7] and high-entropy oxides [13], combining DFT-calculated stability metrics with ML-learned features provides the most robust synthesizability assessment. This synergistic paradigm leverages the strengths of both approaches while mitigating their respective limitations, offering researchers a powerful toolkit for accelerating the discovery and synthesis of novel functional materials and pharmaceutical compounds.

For future research directions, several areas warrant particular attention: (1) developing improved representation learning techniques for out-of-distribution generalization [9], (2) creating more comprehensive and balanced training datasets spanning diverse composition spaces, and (3) advancing hybrid models that explicitly incorporate kinetic and thermodynamic principles within ML frameworks. As these methodologies mature, ML-driven synthesizability prediction will become an increasingly indispensable component of the materials and molecular discovery pipeline.

The discovery of novel functional materials is fundamental to technological progress across sectors such as clean energy, information processing, and healthcare. For decades, materials discovery was bottlenecked by expensive and time-consuming trial-and-error experimental approaches. The emergence of computational high-throughput screening and data-driven methods has dramatically accelerated this process, giving rise to the fourth paradigm of materials science. Central to this revolution are large-scale, publicly available materials databases that consolidate calculated and experimental data. Among these, the Materials Project (MP), the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), and the Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD) have become foundational pillars. This guide provides an objective comparison of these key databases, framing their capabilities and performance within the critical research context of assessing material synthesizability, a domain increasingly shaped by the interplay between traditional Density Functional Theory (DFT) and modern machine learning (ML) methods.

The three databases serve complementary roles in the materials science ecosystem. The table below summarizes their primary functions, data types, and scales.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Key Materials Databases

| Database | Primary Function & Data Type | Key Content & Features | Approximate Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Project (MP) | A repository of computed material properties via DFT (primarily GGA-PBE). | Provides formation energies, band structures, elastic properties, and a web interface for analysis. | Contains hundreds of thousands of calculated structures; a primary source for ML training data [18]. |

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) | A curated repository of experimentally determined crystal structures. | Serves as the definitive source for experimentally validated inorganic crystal structures. | Over 200,000 entries; contains ~20,000 computationally stable structures [18]. |

| Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD) | A high-throughput database of computed DFT formation energies and structures. | Focuses on calculated formation energies for ICSD compounds and hypothetical decorations of common prototypes. | Nearly 300,000 DFT calculations; includes ~32,559 ICSD compounds and ~259,511 hypothetical structures [19]. |

The ICSD is distinguished as the primary source of ground-truth experimental data, while MP and OQMD are large-scale collections of consistent, comparable DFT calculations. A significant trend is the use of MP and OQMD data as training grounds for machine learning models. For instance, the graph network GNoME was trained on data originating from continuing studies like MP and OQMD, leading to the discovery of 2.2 million new stable crystal structures [18].

Quantitative Comparison of Database Outputs and Accuracy

The accuracy of formation energies and stability predictions is a key metric for database utility. The following table compares the performance of DFT-based data from MP and OQMD against experimental benchmarks.

Table 2: Accuracy Comparison of DFT Formation Energies and Stability Predictions

| Database / Method | Reported Formation Energy Error (vs. Experiment) | Stability / Synthesizability Assessment | Limitations & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| OQMD (DFT-PBE) | Mean Absolute Error (MAE): 0.096 eV/atom [19]. | Used to predict ~3,200 new stable compounds [19]. | A significant portion of error may be attributed to experimental uncertainties, which show an MAE of 0.082 eV/atom between different sources [19]. |

| GNoME (ML Model) | Predicts DFT energies with an MAE of 11 meV/atom on relaxed structures [18]. | Achieved >80% precision ("hit rate") in predicting stable structures [18]. | Demonstrates emergent generalization, accurately predicting stability for materials with 5+ unique elements [18]. |

| CSLLM (ML Model) | Not an energy-based method. | 98.6% accuracy in predicting synthesizability from structure, outperforming energy-based metrics [20]. | Significantly outperforms thermodynamic (74.1%) and kinetic (82.2%) stability metrics, indicating a gap between stability and synthesizability [20]. |

The data reveals a critical insight: while DFT formation energies from databases like OQMD provide a reasonable first-pass filter for stability, they are an imperfect proxy for actual synthesizability. ML models trained on these databases can not only reproduce DFT energies with high accuracy but also learn more complex, underlying patterns that correlate better with experimental outcomes.

Experimental and Computational Protocols

The value of a database is intrinsically linked to the consistency and reliability of the methods used to generate its data.

High-Throughput DFT Protocols

Databases like MP and OQMD rely on high-throughput DFT calculations using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP). The core protocol involves:

- Consistent Settings: A standardized level of theory (typically the GGA-PBE functional), plane-wave cutoff, and k-point density is applied across all calculations to ensure results are directly comparable [19].

- Structure Relaxation: Initial crystal structures (often from ICSD) undergo computational relaxation of both atomic positions and lattice vectors until forces on atoms are minimized below a threshold (e.g., 0.01 eV/Ã…).

- Stability Analysis: The formation energy of a compound is calculated relative to its constituent elements in their standard states. The "energy above the convex hull" is then computed, which quantifies a material's thermodynamic stability against decomposition into other competing phases [21] [19].

Beyond Standard DFT: Improving Accuracy

Recognizing the limitations of standard GGA functionals, new databases are emerging that use higher-level methods. For example, a recent database of 7,024 materials was built using all-electron hybrid functional (HSE06) calculations, which significantly improve the accuracy of electronic properties like band gaps. For 121 binary materials, the mean absolute error in band gaps was reduced from 1.35 eV with PBEsol (a GGA functional) to 0.62 eV with HSE06 [22]. This highlights an ongoing effort to enhance the fidelity of computational data at the source.

Machine Learning for Synthesizability Prediction

The CSLLM framework exemplifies a modern ML approach to synthesizability [20]:

- Data Curation: A balanced dataset was constructed with 70,120 synthesizable crystal structures from ICSD and 80,000 non-synthesizable structures identified from theoretical databases using a positive-unlabeled learning model.

- Text Representation: Crystal structures were converted into a simple, reversible text string that includes essential information on lattice, composition, atomic coordinates, and symmetry.

- Model Fine-Tuning: Three specialized large language models (LLMs) were fine-tuned on this data to predict synthesizability, suggest synthetic methods (e.g., solid-state or solution), and identify suitable precursors.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) | Software | The workhorse DFT code used for high-throughput property calculation in databases like MP and OQMD [19]. |

| FHI-aims | Software | An all-electron DFT code enabling high-accuracy hybrid functional calculations (e.g., HSE06) for improved electronic properties [22]. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Model Architecture | Deep learning models that operate directly on crystal graphs, achieving state-of-the-art accuracy in predicting material properties and stability [18] [23]. |

| Sure-Independence Screening (SISSO) | Algorithm | A symbolic regression method used to identify interpretable descriptors for material properties from a vast pool of candidate features [22]. |

| Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) | Model Architecture | Used for the inverse design of novel crystal structures by sampling uncharted chemical spaces, as demonstrated by the PGCGM model [21]. |

Workflow Visualization: From Data to Discovery

The following diagram illustrates the integrated role of databases and methods in the modern materials discovery workflow.

This workflow highlights a key paradigm: a data flywheel where initial DFT databases fuel ML models, which in turn propose new candidates for experimental testing, with successful results feeding back to enrich the original databases [18] [21].

The synergistic relationship between the Materials Project, ICSD, and OQMD has created an unprecedented infrastructure for computational materials science. While these databases provide vast amounts of data based on well-established DFT methodologies, the research frontier is rapidly advancing on two complementary fronts. First, there is a push for higher-fidelity data through the use of more accurate, albeit computationally expensive, methods like hybrid functionals [22]. Second, and potentially more transformative, is the rise of machine learning that leverages these databases not just for screening, but for learning the complex rules of material stability and synthesizability directly, often outperforming traditional DFT-based metrics [20]. The future of materials discovery lies in tightly closed-loop cycles that integrate large-scale computation, intelligent machine learning models, and guided experimental validation, continuously refining our understanding and accelerating the journey from prediction to synthesis.

Building the Models: A Technical Deep Dive into DFT and ML Workflows

In computational materials science, accurately predicting a material's stability and synthesizability is fundamental to discovery and design. Density Functional Theory (DFT) provides a first-principles methodology to calculate key thermodynamic stability metrics, primarily the formation energy and the energy above hull. These metrics allow researchers to screen hypothetical compounds before undertaking costly experimental synthesis. Meanwhile, machine learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful complementary approach, leveraging the vast datasets generated by DFT to build predictive models of synthesizability. This guide objectively compares the methodologies, workflows, and performance of DFT and ML in the critical task of assessing which new materials can be successfully realized in the lab.

Understanding the Core Stability Metrics

Formation Energy

The formation energy ((E^f)) represents the energy change when a compound is formed from its constituent elements in their reference states (e.g., pure elemental solids or diatomic gases). It is calculated as [24] [25] [26]: [E^f = E{\text{tot}} - \sumi ni \mui] where (E{\text{tot}}) is the total energy of the compound from a DFT calculation, (ni) is the number of atoms of element (i), and (\mu_i) is the chemical potential (reference energy) of element (i). A negative formation energy indicates that the compound is thermodynamically stable with respect to its elements at 0 K [27] [26].

Energy Above Hull

The energy above hull ((E{\text{hull}})) is a more rigorous stability metric. It measures the energy difference between a compound and the most stable combination of other phases at its specific composition [28] [26]. A compound with (E{\text{hull}} = 0) eV/atom lies on the "convex hull" of stability and is thermodynamically stable at 0 K. A positive (E{\text{hull}}) value represents the energy cost per atom for the compound to decompose into its most stable competing phases [7] [28]. This decomposition energy, (Ed), is effectively the same as (E_{\text{hull}}) [28].

DFT Workflow: A Step-by-Step Protocol

Calculating formation energy and energy above hull using DFT involves a multi-stage process. The following workflow diagram outlines the key stages, with detailed protocols provided thereafter.

Diagram: The DFT workflow for calculating formation energy and energy above hull, culminating in the key stability metrics.

Computational Setup and Reference Energy Calculation

The initial phase involves careful preparation and calculation of reference energies.

- Select Exchange-Correlation Functional: The choice (e.g., LDA, PBE, PBEsol) influences result accuracy. PBEsol is often recommended for solids [25].

- Optimize Reference Structures: Perform geometry optimization on the pristine bulk structure of the compound of interest and on the reference structures for all constituent elements (e.g., diamond for carbon, Oâ‚‚ molecule for oxygen) [24] [25]. This ensures atomic positions and lattice parameters are at their theoretical ground state.

- Calculate Reference Energies: Using the optimized structures, run single-point energy calculations to obtain the total energy for each reference state. The energy per atom of an elemental solid, or per molecule for a diatomic gas, defines its chemical potential, (\mu_i) [24] [26].

Compound Energy and Formation Energy Calculation

This phase determines the energy of the target compound itself.

- Optimize Compound Geometry: Build the crystal structure of the target compound and perform a full geometry optimization to find its ground-state configuration and energy [25].

- Compute Formation Energy: Using the optimized compound energy ((E{\text{tot}})) and the reference energies ((\mui)), calculate the formation energy using the equation in Section 1.1 [26].

Phase Diagram Construction and Energy Above Hull

The final phase places the compound's stability in the context of all other phases in its chemical system.

- Construct the Convex Hull: For the chemical system of interest (e.g., Li-Fe-O), calculate the formation energies of all known compounds within that system. The convex hull is the lowest-energy "envelope" connecting the stable phases in a plot of energy vs. composition [26].

- Compute Energy Above Hull: For the target compound, its (E{\text{hull}}) is the vertical energy difference between its formation energy and the convex hull at its specific composition. This can be calculated using the decomposition pathway provided by databases like the Materials Project [28]. If a compound's decomposition products are, for example, ( \frac{2}{3}A + \frac{1}{3}B ), then (E{\text{hull}} = E{\text{target}} - (\frac{2}{3}EA + \frac{1}{3}E_B)), where all energies are normalized per atom [28].

Machine Learning as an Alternative Approach

Machine learning offers a data-driven pathway to predict synthesizability, bypassing the computationally intensive DFT workflow.

ML Workflow for Synthesizability

The core steps in building an ML model for synthesizability are:

- Data Collection: Curate a dataset of known materials, typically from the Materials Project (MP) and Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), using the ICSD tag as a proxy for "synthesizable" [3].

- Feature Representation: Convert crystal structures into computer-readable representations. Common methods include the Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Network (CGCNN) and Fourier-Transformed Crystal Properties (FTCP), which captures periodicity in reciprocal space [3].

- Model Training: Train a classifier (e.g., a deep neural network) to predict a synthesizability score (SC) or a binary label (synthesizable/unsynthesizable) based on the crystal representation and sometimes including DFT-derived features like (E_{\text{hull}}) [7] [3].

Performance Comparison: DFT vs. Machine Learning

The table below summarizes a quantitative comparison between DFT-based and ML-based approaches for predicting synthesizability.

Table: Performance and characteristics of DFT and ML for synthesizability assessment.

| Aspect | DFT-Based Approach | Machine Learning Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Metric | Formation Energy ((Ef)), Energy Above Hull ((E{\text{hull}})) [27] [26] | Synthesizability Score (SC) or Crystal-Likeness Score (CLscore) [3] [7] |

| Theoretical Basis | First-principles quantum mechanics [24] [25] | Statistical patterns learned from existing data [3] |

| Typical Workflow Cost | High (hours to days per compound) | Low (seconds per compound after training) [3] |

| Key Strength | Provides fundamental thermodynamic insight; physically interpretable results. | High throughput and speed; can capture non-thermodynamic synthesis factors [7]. |

| Key Limitation | Ignores kinetic barriers and experimental conditions; assumes (T = 0) K [7]. | Dependent on quality and bias of training data; "black box" nature limits interpretability [3]. |

| Reported Accuracy | Many stable ((E{\text{hull}} = 0)) compounds are unsynthesized, and many metastable ((E{\text{hull}} > 0)) compounds are synthesized [7]. | ~82-86% precision/recall for classifying synthesizable ternary compounds [3] [7]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This section details key computational "reagents" essential for performing DFT and ML analyses in materials science.

Table: Essential tools and resources for computational materials science research.

| Tool / Resource | Function | Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Codes (VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO) | Performs the core electronic structure calculations to determine total energies. | Fundamental for computing (E_{\text{tot}}) in the DFT workflow [24] [25]. |

| Materials Project (MP) Database | A repository of pre-computed DFT data for over 126,000 materials, including formation energies and convex hull information [26]. | Used for constructing phase diagrams and as a data source for ML training [7] [3]. |

| pymatgen | A robust Python library for materials analysis. | Essential for programmatically constructing phase diagrams, analyzing structures, and accessing the MP API [28] [26]. |

| CGCNN/FTCP | Deep learning frameworks that use crystal graphs or Fourier-transformed features as input. | Used to build ML models that predict material properties and synthesizability directly from crystal structures [3]. |

| AiiDA | An open-source workflow management platform for automated, reproducible computations. | Manages complex, multi-step computational workflows, such as high-throughput GW calculations or defect studies [29]. |

| PKA substrate | PKA substrate, MF:C39H74N20O12, MW:1015.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Sulfo-Cy3.5 maleimide | Sulfo-Cy3.5 maleimide, MF:C44H43K3N4O15S4, MW:1113.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The most powerful strategy for modern materials discovery is a hybrid approach that leverages the strengths of both DFT and ML. The following diagram illustrates how these methods can be integrated into a cohesive screening pipeline.

Diagram: A hybrid screening workflow combining ML speed with DFT accuracy for efficient materials discovery.

This hybrid workflow begins with ML pre-screening to rapidly evaluate vast chemical spaces and identify promising candidate compositions with high synthesizability scores [3]. These top candidates are then passed to accurate DFT verification to calculate their formation energy and energy above hull, confirming their thermodynamic stability [7] [26]. This two-step process ensures that only the most viable candidates, vetted by both data-driven and first-principles methods, are recommended for experimental validation.

In conclusion, while DFT provides the physical foundation for understanding material stability through formation energy and energy above hull, machine learning offers a scalable and complementary tool for synthesizability prediction. The future of accelerated materials discovery lies not in choosing one over the other, but in strategically integrating both into a unified, hierarchical screening pipeline.

The accurate prediction of material properties, particularly formation energy and synthesizability, represents a cornerstone of modern materials science and drug development. For years, density functional theory (DFT) has served as the computational bedrock for these predictions, providing insights into material stability and properties through quantum mechanical calculations. However, the computational expense and time requirements of DFT have constrained the scope of high-throughput screening. The emergence of sophisticated machine learning (ML) approaches has introduced a transformative paradigm, offering the potential for DFT-comparable accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of two leading ML architectures—Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and Large Language Models (LLMs)—for predicting formation energy and synthesizability, contextualized within the broader framework of machine learning versus DFT for materials assessment.

Formation Energy Prediction: A Critical Stability Metric

Machine Learning Approaches and Performance

Formation energy, the energy difference between a compound and its constituent elements in their standard states, serves as a fundamental indicator of thermodynamic stability. Accurately predicting this property enables researchers to identify potentially synthesizable materials before undertaking experimental efforts.

Table 1: Comparison of ML Models for Formation Energy Prediction

| Model Architecture | Input Representation | Key Features | Reported MAE (eV/atom) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALIGNN (GNN) | Crystal Graph | Bond angles, interatomic distances | ~0.03 (on standard benchmarks) | [17] [30] |

| Voxel CNN | Sparse voxel images | Normalized atomic number, group, period | Comparable to state-of-the-art | [17] |

| MLP on μ-phase | Composition & site features | Site-specific elemental properties | 0.024 (binary), 0.033 (ternary) | [31] |

| LLM-Prop (T5 encoder) | Text descriptions from Robocrystallographer | Space groups, Wyckoff sites | Comparable to GNNs | [30] |

| CGAT | Graph distance embeddings | Prototype-aware, no relaxed structure needed | Not explicitly reported | [32] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Different ML architectures employ distinct strategies for representing and learning from crystal structure information:

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): Models like ALIGNN (Atomistic Line Graph Neural Network) construct crystal graphs where atoms represent nodes and bonds represent edges. A key innovation involves creating line graphs to explicitly incorporate bond angle information, which significantly improves accuracy [17]. The network then uses message-passing layers to learn representations that capture complex atomic interactions.

Voxel-Based Convolutional Networks: This approach transforms crystal structures into sparse 3D voxel images. A cubic box with a fixed side length (e.g., 17 Ã…) is created with the unit cell at its center. After 3D rigid-body rotation, atoms are represented as voxels color-coded by normalized atomic number, group, and period in a manner analogous to RGB channels [17]. These images are processed by deep convolutional networks with skip connections (e.g., 15-layer networks) to autonomously learn relevant features.

Large Language Models (LLMs): The LLM-Prop framework leverages the encoder of a T5 model fine-tuned on textual descriptions of crystal structures generated by tools like Robocrystallographer [30]. Critical preprocessing steps include removing stopwords, replacing bond distances and angles with special tokens ([NUM] and [ANG]), and prepending a [CLS] token for prediction. This approach allows the model to capture nuanced structural information often missing in graph representations.

Specialized Networks for High-Throughput Screening: Crystal Graph Attention Networks (CGAT) utilize graph distances rather than precise bond lengths, making them applicable for high-throughput studies where relaxed structures are unavailable [32]. These networks use attention mechanisms that weight the importance of different atomic environments and incorporate a global compositional vector for context-aware pooling.

Synthesizability Prediction: Bridging Theory and Experiment

Comparative Model Performance

While formation energy indicates thermodynamic stability, synthesizability encompasses kinetic and experimental factors that determine whether a material can be practically realized. Predicting synthesizability remains challenging due to the complexity of synthesis processes and the scarcity of negative data (failed synthesis attempts).

Table 2: Comparison of ML Models for Synthesizability Prediction

| Model / Framework | Architecture | Input Data | Accuracy / Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSLLM | Fine-tuned LLMs | Material string representation | 98.6% accuracy | [1] |

| SynCoTrain | Dual GCNNs (SchNet + ALIGNN) | Crystal structure | High recall on oxides | [33] |

| PU Learning Model | Positive-unlabeled learning | Crystal structure (CLscore) | Used for negative sample identification | [1] |

| Wyckoff Encode-based ML | Symmetry-guided ML | Wyckoff positions | Identified 92K synthesizable from 554K candidates | [11] |

Key Methodological Approaches

Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models (CSLLM): This framework employs three specialized LLMs to predict synthesizability, synthetic methods, and suitable precursors respectively [1]. The model uses a novel "material string" representation that integrates essential crystal information in a compact text format: space group, lattice parameters, and atomic species with their Wyckoff positions. This representation eliminates redundancy present in CIF or POSCAR files while retaining critical structural information.

SynCoTrain: This semi-supervised approach employs a dual-classifier co-training framework with two graph convolutional neural networks (SchNet and ALIGNN) that iteratively exchange predictions to reduce model bias [33]. It uses Positive and Unlabeled (PU) learning to address the absence of explicit negative data, making it particularly valuable for real-world applications where failed synthesis data is rarely published.

Symmetry-Guided Structure Derivation: This approach integrates group-subgroup relations with machine learning to efficiently locate promising configuration spaces [11]. By deriving candidate structures from synthesized prototypes and classifying them using Wyckoff encodes, the method prioritizes subspaces with high probabilities of containing synthesizable structures before applying structure-based synthesizability evaluation.

Machine Learning vs. DFT: A Direct Performance Comparison

The transition from DFT to ML approaches necessitates clear understanding of their relative performance and limitations.

Table 3: ML vs. DFT Performance Comparison

| Prediction Task | DFT-Based Approach | ML Approach | Performance Advantage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synthesizability screening | Energy above hull (≥0.1 eV/atom) | CSLLM | 98.6% vs. 74.1% accuracy | [1] |

| Synthesizability screening | Phonon spectrum (≥ -0.1 THz) | CSLLM | 98.6% vs. 82.2% accuracy | [1] |

| Formation energy (μ-phase) | Direct DFT calculation | MLP model | ~52% reduction in computation time | [31] |

| High-throughput screening | Full DFT relaxation | Crystal Graph Attention Networks | Enables screening of 15M perovskites | [32] |

Key Datasets for Training and Benchmarking

- Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD): A comprehensive collection of experimentally validated crystal structures, typically used as positive examples for synthesizable materials [1].

- Materials Project Database: A vast repository of DFT-calculated material properties containing both stable and unstable structures, enabling training on diverse chemical spaces [1] [32].

- TextEdge Benchmark Dataset: A curated dataset containing crystal text descriptions with corresponding properties, specifically designed for evaluating LLM-based property prediction [30].

- OQMD (Open Quantum Materials Database): A large collection of DFT calculations using consistent parameters, though integration with other databases can be challenging due to parameter inconsistencies [32].

Computational Frameworks and Tools

- ALIGNN (Atomistic Line Graph Neural Network): Implements graph neural networks with explicit bond angle information for accurate property prediction [17].

- Robocrystallographer: Generates descriptive text summaries of crystal structures suitable for LLM-based property prediction [30].

- VASP (Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package): Widely-used DFT software for generating training data and validation calculations [31].

- CGAT (Crystal Graph Attention Networks): Specialized for high-throughput screening without requiring fully relaxed structures [32].

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that both GNNs and LLMs offer significant advantages over traditional DFT approaches for formation energy and synthesizability prediction, albeit with different strengths and limitations. GNNs currently provide state-of-the-art accuracy for formation energy prediction and excel at capturing local atomic environments. LLMs show remarkable performance for synthesizability classification and offer the advantage of leveraging textual representations that naturally incorporate symmetry information often challenging for graph-based approaches.

The emerging trend points toward hybrid frameworks that leverage the complementary strengths of both architectures. Future developments will likely include LLM-powered graph construction from unstructured text, graph-enhanced LLMs that maintain relational consistency, and multi-modal systems that combine the accuracy of structured reasoning with the accessibility of natural language interfaces. As these technologies mature, they will further accelerate the discovery and development of novel functional materials for applications across drug development, energy storage, and beyond.

Predicting whether a hypothetical material or molecule can be successfully synthesized represents one of the most significant bottlenecks in accelerating the discovery of new functional compounds and therapeutics. The ability to reliably identify synthesizable candidates bridges the critical gap between computational predictions and experimental realization, ensuring that proposed structures can be physically produced in laboratory settings. Traditionally, synthesizability assessment has relied heavily on density functional theory (DFT) calculations, particularly formation energy and energy above the convex hull, which serve as proxies for thermodynamic stability. However, these thermodynamic metrics alone provide an incomplete picture of synthesizability, as they fail to capture kinetic factors, synthetic pathway feasibility, and practical experimental considerations that ultimately determine whether a compound can be synthesized.

The emergence of machine learning (ML) approaches has revolutionized synthesizability prediction by enabling the integration of diverse feature sets beyond thermodynamic stability. Contemporary ML models leverage sophisticated feature engineering strategies that incorporate compositional, structural, and stability descriptors to achieve more accurate synthesizability assessments. This paradigm shift from pure-DFT to ML-enhanced methods represents a fundamental advancement in the field, allowing researchers to move beyond the limitations of formation energy calculations and incorporate a more holistic set of descriptors that collectively capture the complex factors influencing synthetic accessibility. The core challenge lies in identifying which feature combinations most effectively predict synthesizability across different material classes and chemical spaces, while maintaining computational efficiency and physical interpretability.

Comparative Analysis of Feature Engineering Approaches

Performance Metrics Across Descriptor Types

Table 1: Quantitative comparison of synthesizability prediction performance across different feature engineering approaches

| Feature Engineering Approach | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composition-Only (SynthNN) | 7× higher than DFT [34] | Not specified | High throughput; No structure required | Cannot distinguish polymorphs |

| Structure-Only (FTCP) | 82.6 [3] | 80.6 [3] | Captures periodicity; No composition limitation | Requires known crystal structure |

| Stability-Informed ML | 82.0 [7] | 82.0 [7] | Leverages existing DFT data; Physical basis | Limited to DFT-accessible systems |

| DFT Formation Energy Only | ~11-50 [34] [7] | ~50 [7] | Strong physical foundation; Well-established | Misses kinetically stable phases |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Composition-Based Feature Engineering (SynthNN)

The SynthNN framework employs a deep learning classification model that operates exclusively on chemical formulas without requiring structural information [34]. The experimental protocol involves several critical steps: First, chemical formulas from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) are encoded using an atom2vec representation, which learns optimal atom embeddings directly from the distribution of synthesized materials. This approach utilizes a semi-supervised positive-unlabeled learning algorithm to handle the lack of confirmed negative examples, as unsuccessful syntheses are rarely reported in literature. The training dataset is augmented with artificially generated unsynthesized materials, with the ratio of artificial to synthesized formulas treated as a hyperparameter. The model architecture consists of a learned atom embedding matrix optimized alongside other neural network parameters, with embedding dimensionality determined through hyperparameter tuning. Performance evaluation demonstrates that this composition-only approach achieves approximately 7 times higher precision in identifying synthesizable materials compared to using DFT-calculated formation energies alone [34].

Structure-Based Feature Engineering (FTCP Representation)

The Fourier-transformed crystal properties (FTCP) representation provides a comprehensive structural descriptor that captures both real-space and reciprocal-space information [3]. The experimental methodology begins with transforming crystal structures into the FTCP representation, which combines real-space crystal features constructed using one-hot encoding with reciprocal-space features formed using elemental property vectors and discrete Fourier transform of real-space features. This dual representation enables the model to capture crystal periodicity and convoluted elemental properties that are inaccessible through other representations. The model employs a deep learning classifier that processes FTCP inputs to generate synthesizability scores (SC) as binary classification outputs. Training utilizes the Materials Project database and ICSD tags as ground truth, with rigorous temporal validation where models trained on pre-2015 data are tested on post-2015 additions. This approach achieves 82.6% precision and 80.6% recall for ternary crystal materials, significantly outperforming stability-only metrics [3].

Stability-Informed Feature Engineering

Hybrid approaches that integrate DFT-calculated stability metrics with compositional and structural features represent a powerful intermediate strategy [7]. The experimental protocol for these methods involves calculating formation energies and energies above the convex hull using DFT for a target set of compositions and structures. These stability metrics are then combined with composition-based features (elemental properties, stoichiometric ratios) and/or simplified structural descriptors. The machine learning model is trained to identify synthesizable materials by recognizing patterns that distinguish reported compounds (from databases like ICSD) from hypothetical unsynthesized compounds. This approach specifically addresses the challenge of "uncorrelated" materials—those that are DFT-stable but unreported or DFT-unstable yet synthesized—by learning the complex relationship between stability, composition, and synthesizability that cannot be captured by simple energy thresholds. The resulting model achieves 82% precision and recall for ternary 1:1:1 compositions in the half-Heusler structure, successfully identifying both stable compounds predicted to be synthesizable and unstable compounds that are nevertheless synthesizable [7].

Visualizing Experimental Workflows and Logical Relationships

Composition-Based Synthesizability Prediction

Composition-Based Prediction Workflow

Structure-Based Synthesizability Prediction

Structure-Based Prediction Workflow

Hybrid ML-DFT Synthesizability Framework

Hybrid ML-DFT Prediction Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key computational tools and databases for synthesizability prediction

| Tool/Database | Type | Primary Function | Application in Synthesizability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Project [3] [35] | Database | DFT-calculated material properties | Provides training data and stability metrics |

| ICSD [3] [34] | Database | Experimentally reported structures | Ground truth for synthesizable materials |

| AiZynthFinder [36] [14] | Software | Retrosynthetic planning | Validates synthetic routes for molecules |

| CAF/SAF [35] | Featurizer | Composition and structure analysis | Generates explainable ML features |

| FTCP [3] | Representation | Crystal structure encoding | Captures periodic features for ML |