Machine Learning for Synthesizable Materials Discovery: Bridging the Gap Between Prediction and Experimental Realization

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how machine learning (ML) is revolutionizing the prediction of synthesizable materials, a critical challenge in accelerating the discovery of new functional compounds for...

Machine Learning for Synthesizable Materials Discovery: Bridging the Gap Between Prediction and Experimental Realization

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how machine learning (ML) is revolutionizing the prediction of synthesizable materials, a critical challenge in accelerating the discovery of new functional compounds for biomedical and industrial applications. We explore the foundational shift from purely energy-based stability predictions to synthesizability-driven frameworks, detailing key ML methodologies from structural featurization and generative models to synthesizability evaluation. The content covers the application of these models in de-risking experimental synthesis, addresses current bottlenecks like data scarcity and model generalizability, and evaluates model performance through benchmarking and experimental validation. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this article synthesizes the current state-of-the-art and future directions for integrating ML into the materials discovery pipeline.

The Synthesizability Challenge: Why Energy Stability Alone Isn't Enough

The discovery of new functional materials is a cornerstone of technological advancement, from developing better battery materials to novel semiconductors. For decades, computational materials science has relied on thermodynamic stability, typically calculated using density functional theory (DFT), as the primary filter for identifying promising new materials. This approach assumes that materials with favorable formation energies—those lying on or near the convex hull of thermodynamic stability—are synthetically accessible. However, a significant and persistent gap exists between computational predictions and experimental realization: many computationally predicted "stable" materials prove impossible to synthesize, while numerous metastable materials are routinely synthesized in laboratories worldwide [1] [2].

This gap emerges because thermodynamic stability represents only one factor influencing whether a material can be successfully synthesized. Experimental synthesizability is governed by a complex interplay of kinetic factors, reaction pathways, precursor selection, and synthetic conditions that thermodynamic calculations alone cannot capture [3] [4]. The critical limitation of energy-based screening is its fundamental inability to identify experimentally realizable metastable materials synthesized through kinetically controlled pathways [1]. This creates a critical bottleneck in materials discovery pipelines, where promising computational predictions fail to translate into laboratory success.

The emergence of machine learning approaches offers promising pathways to bridge this gap. By learning directly from experimental data rather than relying solely on thermodynamic principles, ML models can capture the complex patterns and relationships that dictate synthetic success [2] [5]. This technical guide explores the fundamental limitations of thermodynamic stability predictions, surveys the latest machine learning approaches designed to predict synthesizability, and provides practical methodologies for integrating these tools into materials discovery workflows.

The Fundamental Limitations of Thermodynamic Stability

Theoretical Framework and Practical Shortcomings

Thermodynamic stability assessment typically relies on calculating a material's decomposition energy (ΔHd), defined as the total energy difference between a given compound and its most stable competing phases in a specific chemical space [6]. The convex hull constructed from formation energies of compounds within a phase diagram serves as the reference point—materials with decomposition energies of zero lie on the hull and are considered thermodynamically stable, while those with positive energies are metastable or unstable [6].

Despite its theoretical foundation, this approach suffers from significant practical limitations:

Metastable Materials Synthesis: Many successfully synthesized materials are metastable, possessing positive decomposition energies. Their synthesis is enabled by kinetic stabilization through specific reaction pathways [3] [4]. For example, in Liâ‚‚M(SOâ‚„)â‚‚ compounds, metastable polymorphs are synthesized despite positive formation enthalpies, with vibrational/rotational disorder of SOâ‚„ tetrahedra providing the entropy term that enables their formation [3].

Incomplete Phase Information: Constructing accurate convex hulls requires knowledge of all competing phases in a chemical space, which is often incomplete, especially for unexplored compositional territories [6].

Temperature and Pressure Neglect: Standard convex hull analyses typically consider only zero-temperature, ambient-pressure conditions, ignoring the thermodynamic driving forces available through control of experimental parameters [3].

Kinetic Factors: Thermodynamic approaches cannot account for kinetic barriers that dominate solid-state reactions, including diffusion limitations, nucleation barriers, and intermediate phase formation [2].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

| Prediction Method | Underlying Principle | Reported Accuracy | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formation Energy/Convex Hull [2] [6] | Thermodynamic stability | ~50% of synthesized materials captured [2] | Misses metastable phases; ignores kinetics |

| Charge Balancing [2] | Charge neutrality constraint | 37% of known compounds [2] | Over-simplifies bonding environments |

| SynthNN [2] | Composition-based deep learning | 7× higher precision than DFT [2] | No structural information considered |

| CSLLM [4] | Crystal structure-based large language model | 98.6% accuracy [4] | Requires careful dataset construction |

Case Study: Lithium Polyanion Battery Materials

Experimental work on Liâ‚‚M(SOâ‚„)â‚‚ compounds provides compelling evidence for the thermodynamic stability-synthesizability gap. Research demonstrated that both monoclinic (M = Mn, Fe, Co) and orthorhombic (M = Fe, Co, Ni) polymorphs could be synthesized despite positive enthalpies of formation determined through calorimetry [3]. The orthorhombic polymorphs with Fe and Co were found to be energetically less stable than their corresponding monoclinic forms, yet they could be synthesized through ball milling methods [3].

This case study highlights a crucial principle: the entropy term (TΔS) can overcome positive enthalpy of formation in polymorphic systems, enabling metastable phase synthesis through carefully controlled kinetic pathways [3]. Such phenomena cannot be captured by standard thermodynamic stability calculations, underscoring the need for synthesizability-aware prediction frameworks.

Machine Learning Approaches to Bridge the Gap

Composition-Based Models

Composition-based machine learning models predict synthesizability directly from chemical formulas without requiring structural information, making them particularly valuable for exploring new compositional spaces where crystal structures are unknown.

The SynthNN model exemplifies this approach, using a deep learning architecture that leverages the entire space of synthesized inorganic chemical compositions [2]. By reformulating material discovery as a synthesizability classification task, SynthNN identifies synthesizable materials with 7× higher precision than DFT-calculated formation energies [2]. Remarkably, without explicit programming of chemical rules, SynthNN learns principles of charge-balancing, chemical family relationships, and ionicity directly from data [2].

These models typically employ positive-unlabeled (PU) learning frameworks to address the fundamental challenge that only successfully synthesized materials (positive examples) are typically recorded in databases, while unsuccessful synthesis attempts (negative examples) are rarely reported [2] [4]. The Synthesizability Dataset is augmented with artificially generated unsynthesized materials, with the model treating unsynthesized materials as unlabeled data and probabilistically reweighting them according to their likelihood of being synthesizable [2].

Structure-Based Models

Structure-based models offer enhanced predictive power by incorporating crystal structure information alongside composition. The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models (CSLLM) framework represents a significant advancement, utilizing three specialized LLMs to predict synthesizability, possible synthetic methods, and suitable precursors for arbitrary 3D crystal structures [4].

CSLLM achieves state-of-the-art accuracy (98.6%), significantly outperforming traditional synthesizability screening based on thermodynamic and kinetic stability [4]. The framework uses an efficient text representation for crystal structures that integrates essential crystal information, enabling fine-tuning of LLMs specifically for synthesizability prediction [4].

Another approach integrates symmetry-guided structure derivation with Wyckoff encode-based machine learning models, allowing efficient localization of subspaces likely to yield highly synthesizable structures [1]. Within these promising subspaces, structure-based synthesizability evaluation models fine-tuned using recently synthesized structures are employed alongside ab initio calculations to systematically identify synthesizable candidates [1].

Table 2: Machine Learning Models for Synthesizability Prediction

| Model Name | Input Type | Model Architecture | Key Advantages | Representative Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SynthNN [2] | Composition | Deep Neural Network | No structural info required; high throughput | Outperforms human experts by 1.5× precision |

| Synthesizability-Driven CSP [1] | Composition & Structure | Wyckoff encode-based ML | Identifies promising subspaces | Reproduced 13 known XSe structures |

| CSLLM [4] | Structure | Large Language Model | Predicts methods & precursors | 98.6% synthesizability accuracy |

| ECSG [6] | Composition | Ensemble ML | Mitigates inductive bias | 0.988 AUC for stability prediction |

Ensemble and Hybrid Approaches

Ensemble methods that combine multiple models with different inductive biases have shown improved performance for synthesizability prediction. The Electron Configuration models with Stacked Generalization (ECSG) framework integrates three base models—Magpie, Roost, and ECCNN—that leverage different domain knowledge: statistical features of elemental properties, interatomic interactions, and electron configurations [6].

This approach mitigates the limitations of individual models by combining their complementary strengths, achieving an Area Under the Curve score of 0.988 in predicting compound stability [6]. The framework demonstrates exceptional efficiency in sample utilization, requiring only one-seventh of the data used by existing models to achieve the same performance [6].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Dataset Construction for Synthesizability Prediction

Curating high-quality datasets is foundational for developing accurate synthesizability prediction models. The following protocol outlines the approach used for CSLLM development [4]:

Positive Example Collection: Select experimentally validated crystal structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD). Apply filters for structural integrity (e.g., exclude disordered structures, limit to ≤40 atoms and ≤7 different elements).

Negative Example Generation: Employ a pre-trained PU learning model to generate CLscores for theoretical structures from multiple databases (Materials Project, Computational Materials Database, OQMD, JARVIS). Select structures with the lowest CLscores (e.g., <0.1) as negative examples.

Dataset Balancing: Create a balanced dataset with approximately equal numbers of synthesizable and non-synthesizable structures. Verify that most positive examples have CLscores >0.1 to ensure separation.

Structural Diversity Validation: Visualize dataset coverage using t-SNE to ensure representation across crystal systems (cubic, hexagonal, tetragonal, orthorhombic, monoclinic, triclinic, trigonal) and compositional diversity.

Model Training and Evaluation

The training protocol for synthesizability prediction models typically follows these stages [2] [4]:

Feature Representation:

- For composition-based models: Use learned atom embedding matrices (e.g., atom2vec) optimized alongside other neural network parameters.

- For structure-based models: Develop efficient text representations (e.g., "material strings") that integrate essential crystal information (lattice parameters, composition, atomic coordinates, symmetry).

Positive-Unlabeled Learning: Implement class-weighting for unlabeled examples according to their likelihood of synthesizability. The ratio of artificially generated formulas to synthesized formulas (Nₛyₙₜₕ) is treated as a hyperparameter.

Model Architecture Selection: Choose appropriate architectures based on input type:

- Composition-based: Deep neural networks with atom embedding layers.

- Structure-based: Fine-tuned transformer architectures for LLMs.

Performance Validation: Evaluate using standard metrics (precision, recall, F1-score) with careful interpretation in PU learning context. Conduct head-to-head comparisons against human experts and traditional methods.

Workflow Integration

A synthesizability-driven crystal structure prediction framework integrates multiple components [1]:

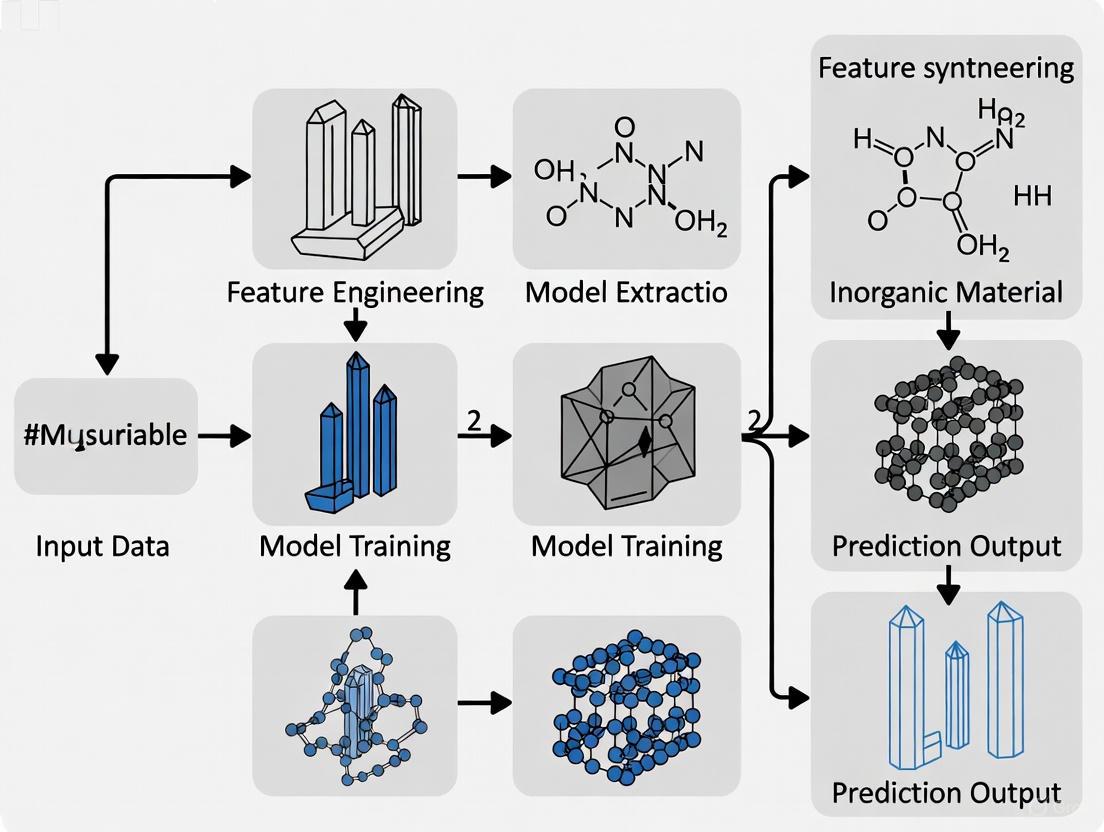

Synthesizability Prediction Workflow

Table 3: Essential Resources for Synthesizability-Driven Materials Discovery

| Resource Name | Type | Function/Role | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [2] [4] | Database | Source of experimentally verified crystal structures for training positive examples | Commercial |

| Materials Project [6] [4] | Database | Source of theoretical structures for negative example generation and validation | Free |

| Matminer [7] | Software Library | Feature generation for materials using published featurizations | Open Source |

| Automatminer [7] | Reference Algorithm | Automated machine learning pipeline for materials property prediction | Open Source |

| CSLLM Framework [4] | Software Tool | Predicts synthesizability, methods, and precursors for crystal structures | Research |

| JARVIS [6] [4] | Database | Source of DFT-computed properties and structures for training | Free |

The gap between thermodynamic stability predictions and experimental synthesizability represents both a fundamental challenge and an opportunity for computational materials science. Traditional energy-based screening methods, while valuable for identifying thermodynamically stable materials, fail to capture the complex kinetic and experimental factors that determine synthetic success.

Machine learning approaches that learn directly from experimental data offer a powerful pathway to bridge this gap. By capturing patterns in successful syntheses that transcend simple thermodynamic considerations, models like SynthNN and CSLLM demonstrate significantly improved precision in identifying synthesizable materials compared to traditional methods [2] [4]. The integration of these synthesizability predictors into materials discovery workflows enables more efficient prioritization of candidates for experimental investigation.

Future advancements will likely come from several directions: improved integration of synthesis conditions and precursor information into predictive models, development of larger and more comprehensive datasets that include failed synthesis attempts, and creation of hybrid models that combine physical principles with data-driven insights. As these technologies mature, they will accelerate the discovery of novel functional materials by providing more reliable guidance on synthetic accessibility, ultimately bridging the critical gap between computational prediction and experimental realization.

The discovery of novel functional materials is fundamental to technological progress across sectors, from clean energy to medicine. However, the traditional process of materials discovery has been bottlenecked by expensive trial-and-error approaches that are slow, resource-intensive, and fundamentally limited in their ability to explore the vastness of chemical space [8]. Before the advent of data-driven methods, material discovery relied heavily on these techniques and on first-principles calculations, such as density functional theory (DFT), which, while accurate, are computationally intensive and slow, especially for exploring large compositional or structural design spaces [5].

The critical first step in discovering any new material is identifying a novel chemical composition that is synthesizable—defined as a material that is synthetically accessible through current capabilities, regardless of whether it has been synthesized yet [2]. This article defines the concept of "synthesizability," contrasts it with related concepts like stability, and details the modern computational and machine-learning methodologies used to predict it, thereby creating a foundational reference for researchers in the field.

Beyond Thermodynamics: A Multi-Faceted Definition of Synthesizability

A common, but often insufficient, proxy for synthesizability is thermodynamic stability. The established computational method for assessing this is calculating a material's formation energy and its distance to the convex hull of stable phases. Materials that lie on this hull (with a formation energy of 0 eV/atom) are considered thermodynamically stable, while those above it are metastable or unstable [8]. However, synthesizability is a broader and more complex property. A material that is thermodynamically stable may still be impossible to synthesize with current methods, while kinetic stabilization or specific reaction pathways can enable the synthesis of metastable materials [2] [9].

Table 1: Key Concepts in Defining Synthesizability

| Term | Definition | Limitations as a Synthesizability Proxy |

|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamic Stability | A material is stable if no set of other phases has a lower combined energy. Determined by calculating the energy above the convex hull. | Does not account for kinetic stabilization or synthesis pathway. Many synthesizable materials are metastable [2]. |

| Charge-Balancing | A heuristic that filters chemical formulas to have a net neutral ionic charge based on common oxidation states. | An inflexible constraint; only ~37% of known synthesized inorganic materials are charge-balanced. Fails for metallic or covalent systems [2]. |

| Synthesizability | A material is synthesizable if it is synthetically accessible through current experimental capabilities, regardless of its prior synthesis status [2]. | The target property, but cannot be defined by a single simple rule. Depends on a complex array of physical and practical factors. |

The decision to synthesize a material depends on a wide range of considerations beyond simple thermodynamics, including the cost of reactants, availability of equipment, and human-perceived importance of the final product [2]. Therefore, synthesizability cannot be predicted based on thermodynamical or kinetic constraints alone.

Traditional Heuristics and Computational Screening

Established Rules and High-Throughput Computation

Before the rise of modern machine learning, researchers relied on chemically intuitive heuristics and high-throughput computational screening.

- Elemental Substitution and Prototype Enumeration: Guided searches involved substituting similar ions in known crystal structures or enumerating known structural prototypes. While this improved efficiency, it fundamentally limited the diversity of candidate materials [8].

- High-Throughput Density Functional Theory (DFT): Projects like the Materials Project, the Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD), and AFLOWLIB have used high-throughput DFT calculations to screen thousands of candidate materials for thermodynamic stability [8]. This involves a standard workflow of geometry optimization and energy calculation to determine a material's stability.

Table 2: Traditional Computational Screening Methods

| Method | Description | Typical Software/Platform | Key Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geometry Optimization | Computes the most stable atomic configuration of a crystal structure by minimizing forces on atoms. | VASP (Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package) [10] | Relaxed crystal structure, total energy. |

| Formation Energy Calculation | Calculates the energy of a compound relative to its constituent elements in their standard states. | VASP, Materials Project workflows [8] [10] | ΔHf (Formation Enthalpy) |

| Convex Hull Construction | Determines the set of thermodynamically stable phases by calculating the lower convex envelope of formation energies for all competing phases in a chemical space. | Materials Project, OQMD [8] | Energy above hull (Ehull) |

| Phonon Calculation | Models atomic vibrations to assess dynamic stability (absence of imaginary frequencies). | VASP, Phonopy [10] | Phonon dispersion spectrum |

| Elastic Constant Calculation | Computes the elastic tensor to evaluate mechanical stability (satisfaction of Born criteria). | VASP [10] | Elastic constants (Cij) |

Experimental Synthesis and Processing Techniques

The ultimate test of synthesizability is successful synthesis in the laboratory. Common synthesis techniques for solid-state and inorganic materials include:

- Solid-State Reaction: Heating powdered precursor elements or compounds at high temperatures to facilitate diffusion and reaction.

- Sol-Gel Process: A wet-chemical technique using a chemical solution (sol) that transitions to a gel network, which is then dried and heated to form a solid [11].

- Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD): Depositing a solid material from a vapor phase onto a substrate [11].

- Hydrothermal/Solvothermal Synthesis: Using heated solutions in a sealed vessel (autoclave) to create high-pressure conditions for crystallizing materials.

The Machine Learning Paradigm for Synthesizability Prediction

Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a transformative tool to overcome the limitations of traditional methods. ML models can analyze large, diverse datasets to uncover complex, non-linear relationships between a material's composition, structure, and its likelihood of being synthesizable [5].

Key Machine Learning Approaches

A significant advancement in ML-based prediction is the development of models trained directly on the database of all synthesized materials, allowing them to learn the optimal set of descriptors for synthesizability rather than relying on pre-defined proxy metrics [2].

- Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning: A major challenge is the lack of confirmed negative examples (proven unsynthesizable materials). PU learning algorithms treat the vast space of unknown materials as unlabeled data and probabilistically reweight them according to their likelihood of being synthesizable. The SynthNN model is a deep learning classifier that uses this approach, trained on data from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [2].

- Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): These models represent crystal structures as graphs (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges), making them exceptionally well-suited for learning structure-property relationships. The GNoME (Graph Networks for Materials Exploration) framework has demonstrated that GNNs trained at scale can reach unprecedented levels of generalization, accurately predicting formation energy and stability [8].

- Composition-Based Models: For cases where the crystal structure is unknown, models can predict stability from the chemical formula alone using learned compositional representations like atom2vec [2].

Performance and Validation of ML Models

ML models have demonstrated a remarkable ability to not only predict known outcomes but also to learn underlying chemical principles.

- Performance Benchmarks: In a head-to-head comparison, the SynthNN model identified synthesizable materials with 7x higher precision than using DFT-calculated formation energies alone and outperformed 20 expert materials scientists, achieving 1.5x higher precision and completing the task five orders of magnitude faster [2]. The GNoME project improved the precision of stable predictions (hit rate) to above 80% when structural information was available [8].

- Emergent Chemical Understanding: Remarkably, without any prior chemical knowledge, models like SynthNN learn fundamental chemical principles such as charge-balancing, chemical family relationships, and ionicity from the data itself [2]. They also exhibit emergent generalization, accurately predicting the stability of materials with five or more unique elements—a space notoriously difficult for human intuition to navigate [8].

Case Study: Data-Driven Discovery of MAX Phases

A concrete example of this modern paradigm is the data-driven discovery of novel MAX phases, a family of layered carbides and nitrides with the formula Mn+1AXn [10].

Workflow:

- Database Creation: Researchers created a database of 9,660 potential MAX phase structures with variations in M, A, and X elements (including B, O, P, S, and Si).

- Machine Learning Screening: ML models, trained on structural descriptors and physical properties, screened this vast database to identify promising candidates.

- DFT Validation: The top candidates were validated using DFT calculations to confirm their dynamic (phonon) and mechanical (elastic constants) stability.

- Experimental Synthesis Guidance: The final list of predicted synthesizable structures provides a targeted roadmap for experimental synthesis efforts.

Outcome: This integrated approach successfully predicted 13 synthesizable MAX phase compounds that had not been previously reported, demonstrating the power of ML to efficiently guide discovery in a targeted materials family [10].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in Synthesizability Research |

|---|---|---|

| Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) | Software | Performs DFT calculations for geometry optimization, energy, and property calculations, serving as the validation step for ML predictions [10]. |

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) | Database | A comprehensive collection of experimentally reported crystal structures; the primary source of "positive" data for training synthesizability models [2]. |

| Materials Project / OQMD / AFLOW | Database | Curated databases of computationally derived material properties and stability data, used for training and benchmarking ML models [5] [8]. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) Models (e.g., GNoME) | ML Model | Learns structure-property relationships by representing crystals as graphs; highly effective for predicting formation energy and stability [8]. |

| Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning Algorithms | ML Method | Handles the lack of confirmed negative data by treating unsynthesized materials as unlabeled examples, crucial for realistic synthesizability classification [2]. |

| Evolutionary Algorithms (e.g., USPEX) | Software | Used for crystal structure prediction and phase stability checks, often complementing ML-based searches [10]. |

The definition of a "synthesizable material" is evolving from one based solely on rigid chemical heuristics and thermodynamic rules to a more nuanced, data-driven concept. Modern approaches recognize that synthesizability is a complex probabilistic property that can be learned by machine learning models from the collective history of experimental synthesis. By integrating high-throughput computation, active learning, and advanced models like GNNs, the materials science community is building a future where synthesizability is a predictable constraint, enabling the targeted and efficient discovery of next-generation functional materials.

The paradigm of materials discovery is undergoing a profound shift from traditional trial-and-error approaches to data-driven scientific inquiry. Central to this transformation is the strategic utilization of materials databases as foundational training sets for machine learning (ML) models. These curated repositories provide the structured data necessary for ML algorithms to uncover complex patterns linking material composition, structure, and properties. The Materials Project alone serves over 600,000 registered users and delivers millions of data records daily through its application programming interface (API), fostering data-rich research across materials science [12]. This wealth of computed and experimental data, when properly leveraged, enables predictive models that can significantly accelerate the identification of novel synthesizable materials with targeted properties.

The fundamental challenge in materials informatics lies in navigating the immense combinatorial space of possible materials. Traditional computational methods like density functional theory (DFT) and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, while accurate, are computationally intensive and impractical for screening vast chemical spaces [5]. Machine learning addresses this limitation by training on existing materials data to establish surrogate models that predict material properties rapidly, redirecting experimental and computational resources toward the most promising candidates [13]. However, the performance and reliability of these models critically depend on the quality, diversity, and structure of the underlying training data, making the understanding of materials databases an essential prerequisite for effective ML implementation in materials science.

Major Materials Databases and Repositories

The materials science community has developed numerous structured databases that collectively capture known and hypothetical materials across different chemical families and structure types. These repositories vary in content origin, material classes covered, and primary application focus. Understanding their distinct characteristics enables researchers to select appropriate data sources for specific ML tasks.

Table 1: Major Materials Databases for ML Training

| Database Name | Content Type | Material Classes | Key Features | Primary Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Project [12] [13] | Computed Properties | Inorganic Materials | Over 200,000 materials with millions of computed properties; Free API access | High-throughput screening, Design algorithms |

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [13] [14] | Experimental Structures | Inorganic Crystals | Curated experimental crystal structures; Reference data for validation | Training on experimentally verified structures |

| Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) [13] | Experimental Structures | Organic/Metal-Organic Crystals | Extensive organic and metal-organic crystal data | Molecular materials, MOF research |

| CoRE MOF [13] | Curated Experimental | Metal-Organic Frameworks | Experimentally refined MOF structures; Focus on small-pore regions | Gas separation, Adsorption studies |

| Novel Materials Discovery (NOMAD) [13] [5] | Computed & Experimental | Multiple Classes | Repository for computational materials science data | Developing diverse training sets |

| ToBaCCo [13] | Hypothetical | Metal-Organic Frameworks | In silico generated MOFs; Focus on large-pore regions | Exploring extended chemical space |

These databases collectively provide the foundational data for ML applications, yet they exhibit important distinctions in their coverage of chemical space. For instance, analysis of metal-organic framework databases reveals that experimental MOFs (CoRE-2019) predominantly occupy small-pore regions, while hypothetical databases (ToBaCCo) contain structures mainly in the large-pore region [13]. This distribution bias has significant implications for ML model generalization and must be considered when constructing training sets. Similarly, hypothetical databases often lack diversity in metal chemistry, which can lead to incomplete or skewed predictions regarding the importance of specific elements for target applications [13].

Data Curation and Feature Engineering Methodologies

Expert-Curated Data Workflows

The ME-AI (Materials Expert-Artificial Intelligence) framework demonstrates the critical importance of domain expertise in data curation for materials ML [14]. This approach translates experimental intuition into quantitative descriptors extracted from curated, measurement-based data through a systematic workflow:

- Primary Feature Selection: Domain experts identify chemically meaningful primary features (PFs) including electron affinity, electronegativity, valence electron count, and crystallographic distances [14].

- Expert Labeling: Materials are annotated based on experimental band structure data (56% of database) or chemical logic for related compounds (44% of database) [14].

- Descriptor Discovery: Machine learning models, particularly Gaussian processes with chemistry-aware kernels, uncover emergent descriptors composed of primary features [14].

In the ME-AI implementation for topological semimetals, this workflow utilized 879 square-net compounds described using 12 experimental features, successfully recovering known structural descriptors like the "tolerance factor" while identifying new descriptors related to hypervalency concepts [14]. This demonstrates how expert-guided curation can extract meaningful patterns from relatively small datasets (hundreds to thousands of compounds), overcoming the limitations of purely data-driven approaches.

Feature Encoding and Selection Techniques

Materials data presents unique challenges for feature representation due to the varied nature of material systems, from crystalline inorganic compounds to complex polymer architectures. Effective feature engineering employs several encoding strategies:

- Atomic Descriptors: Fundamental atomic properties including electron affinity, electronegativity, and valence electron counts, often represented using maximum and minimum values across compound elements [14].

- Structural Descriptors: Crystallographic parameters such as lattice parameters, atomic distances, and symmetry information [14] [15].

- Domain Knowledge Descriptors: Expert-derived features such as tolerance factors for perovskite structures or dimensional indices for low-dimensional materials [14] [15].

Feature selection methods are crucial for managing the high dimensionality of materials feature spaces. The SISSO (Sure Independence Screening and Sparsifying Operator) method has emerged as a powerful approach for identifying optimal descriptor combinations from large feature spaces [15]. This method generates numerous mathematical combinations of primary features and screens for the most physically meaningful descriptors, successfully applied to correct perovskite tolerance factors and establish criteria for strong metal-metal interactions [15].

Additional feature selection strategies include:

- Filter Methods: Statistical approaches that evaluate feature relevance independently of the ML model.

- Wrapper Methods: Feature selection wrapped around model training, evaluating subsets based on model performance.

- Embedded Methods: Algorithms that perform feature selection as part of the model training process [15].

Integrated approaches like MIC-SHAP, which combines maximum information coefficient with SHapley Additive exPlanations, have demonstrated effectiveness in selecting optimal feature subsets for predicting properties like solid solution strengthening in high-entropy alloys [15].

Data Curation and Modeling Workflow

Machine Learning Approaches for Materials Data

Multi-Objective Optimization Frameworks

Materials for practical applications must typically satisfy multiple property requirements, often with competing relationships. Multi-objective optimization addresses this challenge by identifying materials that optimally balance these trade-offs. The core concept in multi-objective optimization is the Pareto front - a set of solutions where improvement in one objective necessitates deterioration in another [15].

Machine learning accelerates Pareto front identification through several strategies:

- Pareto Front-Based Strategy: ML models predict multiple properties simultaneously, with optimization algorithms identifying non-dominated solutions across all objectives [16] [15].

- Scalarization Function: Multiple objectives are combined into a single weighted objective function, transforming the problem into single-objective optimization [15].

- Constraint Method: One objective is optimized while treating others as constraints with minimum acceptable values [15].

Benchmark studies have demonstrated that automated machine learning approaches like AutoSklearn, combined with evolutionary optimizers such as CMA-ES, can achieve near Pareto-optimal designs with minimal data requirements [16]. These approaches are particularly valuable for materials design problems where data acquisition is expensive or time-consuming.

Data Modes for Multi-Objective Learning

The structure of training data significantly influences multi-objective ML implementation. Two primary data modes are employed:

- Mode 1: A unified dataset where all samples have the same features and multiple target properties, enabling multi-output models that predict all objectives simultaneously [15].

- Mode 2: Separate datasets for each property, with potentially different samples and features, requiring multiple specialized models for different objectives [15].

The choice between these modes depends on data availability and the relationships between target properties. Mode 1 is preferable when sufficient data exists for all properties across a consistent sample set, while Mode 2 offers flexibility for leveraging all available data, particularly when different descriptors are relevant for different properties.

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies

Case Study: Predictive Models for Topological Materials

The ME-AI framework demonstrates a complete protocol for data-driven discovery of functional materials [14]:

Experimental Protocol:

- Dataset Curation: 879 square-net compounds from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) with 12 primary features including electron affinity, electronegativity, valence electron count, and crystallographic distances.

- Expert Labeling: Materials classified as topological semimetals (TSMs) or trivial materials based on experimental band structure data (56%) or chemical logic for related compounds (44%).

- Model Training: Dirichlet-based Gaussian process model with chemistry-aware kernel trained to identify emergent descriptors.

- Validation: Model predictions tested on holdout compounds and extended to different material families (rocksalt topological insulators).

Results and Significance: The model successfully recovered the known structural "tolerance factor" descriptor and identified four new emergent descriptors, including one aligned with classical chemical concepts of hypervalency and the Zintl line [14]. Remarkably, the model trained solely on square-net compounds correctly classified topological insulators in rocksalt structures, demonstrating transferability across chemical families. This case highlights how expert-curated experimental data can produce models with strong predictive power and physical interpretability.

Case Study: Fossil Identification via Morphological Traits

Beyond electronic materials, similar principles apply to diverse material classification problems. A study on Czekanowskiales fossils demonstrated how machine learning with carefully encoded morphological traits enables quantitative taxonomic identification [17]:

Experimental Protocol:

- Trait Encoding: Macroscopic and cuticular traits statistically recorded from fossil specimens and encoded using label encoding and one-hot encoding methods.

- Algorithm Comparison: Five supervised learning algorithms (logistic regression, k-nearest neighbors, naive Bayes, classification and regression tree, support vector machine) evaluated for genus and species identification.

- Feature Importance Analysis: Trait significance assessed for different taxonomic levels.

Results and Significance: The study established that macroscopic traits are more important for genus-level identification, while cuticular traits provide greater discrimination at the species level [17]. Classification and regression tree algorithms demonstrated superior performance, with inclusion of cuticular traits significantly improving identification accuracy. This approach demonstrates the value of manual trait encoding for domains with limited training data, where image-based deep learning would require impractically large datasets.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function in ML Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Materials Databases | Materials Project, ICSD, CSD, CoRE MOF | Provide training data and validation references |

| Feature Engineering | SISSO, MIC-SHAP, Domain Knowledge Descriptors | Generate and select optimal feature representations |

| ML Algorithms | Gaussian Processes, AutoSklearn, CART, Ensemble Methods | Build predictive models from materials data |

| Optimization Frameworks | CMA-ES, NSGA-II, MOEA/D | Identify Pareto-optimal material solutions |

| Validation Tools | Independent Test Sets, Cross-Validation, Experimental Synthesis | Verify model predictions and transferability |

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant advances, several challenges persist in leveraging materials databases for ML training. Data quality and consistency remain concerns, particularly with experimental data subject to synthesis conditions and measurement protocols [18] [19]. The black-box nature of some complex ML models limits physical interpretability, driving interest in hybrid approaches that combine data-driven learning with physics-based constraints [18] [5].

Future progress depends on developing modular, interoperable AI systems and standardized FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data principles [18] [19]. Addressing data quality and integration challenges will resolve issues related to metadata gaps, semantic ontologies, and data infrastructures, especially for small datasets [18]. This will unlock transformative advances in fields like nanocomposites, metal-organic frameworks, and adaptive materials.

Emerging approaches include:

- Hybrid modeling: Combining traditional computational models offering interpretability and physical consistency with AI/ML excelling in speed and complexity handling [18].

- Transfer learning: Applying models trained on one material family to different but related systems, as demonstrated by the ME-AI application to rocksalt structures [14].

- Autonomous experimentation: Integrating ML with robotic laboratories for closed-loop materials synthesis and testing, dramatically accelerating the discovery cycle [5].

As materials databases continue to grow in size and diversity, and ML methodologies become increasingly sophisticated, the partnership between data-driven discovery and fundamental materials understanding will undoubtedly yield novel functional materials addressing critical technological needs across energy, electronics, and sustainability.

The discovery of new functional materials has historically been guided by experimental trial-and-error, a process that is often time-consuming, resource-intensive, and unpredictable. While computational methods, particularly density functional theory (DFT), have revolutionized our ability to predict material properties in silico, a critical gap persists between theoretical prediction and experimental realization [1]. Traditional energy-based crystal structure prediction approaches predominantly identify thermodynamically stable materials, struggling to pinpoint the metastable materials frequently synthesized through kinetically controlled pathways [1]. This disconnect means that thousands of promising computationally predicted compounds may never be synthesized, creating a fundamental bottleneck in materials innovation.

Machine learning (ML) is now enabling a paradigm shift from this haphazard discovery process to a targeted, rationale-driven approach. By learning complex patterns from existing experimental and computational data, ML models can predict not only whether a material is likely to be synthesizable but also the appropriate synthesis conditions and precursors required for its realization [5] [4]. This new paradigm leverages advanced algorithms including graph neural networks, large language models, and generative AI to navigate the vast chemical space efficiently, systematically bridging the gap between computational design and laboratory synthesis that has long hampered the field [1] [20].

Core ML Approaches for Synthesis Prediction

Key Algorithms and Their Applications

The ML landscape for materials discovery encompasses diverse algorithms, each suited to particular aspects of the synthesis prediction challenge. These algorithms learn from materials databases to establish the complex relationships between composition, structure, synthesis conditions, and experimental realizability.

Table 1: Essential Machine Learning Algorithms in Materials Discovery

| Algorithm Category | Specific Models | Primary Applications in Materials Discovery | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Networks [5] | Property prediction from crystal structure [21] | Naturally encodes atomic bonding and periodicity |

| Ensemble Methods | Random Forest, XGBoost [20] [22] | Synthesis parameter prediction (temperature, time) [5] | Handles small datasets robustly; good interpretability |

| Large Language Models (LLMs) | Fine-tuned LLaMA, ChatGPT [4] | Synthesizability classification, precursor identification [4] | Processes text-based structure representations effectively |

| Deep Generative Models | Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) [5] | De novo design of novel crystal structures [5] | Enables inverse design of materials with target properties |

Specialized Frameworks for Synthesizability Prediction

Recently, specialized end-to-end frameworks have emerged to tackle the synthesizability challenge comprehensively. The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM) framework utilizes three specialized LLMs to address distinct aspects of the synthesis problem [4]. The Synthesizability LLM predicts whether an arbitrary 3D crystal structure is synthesizable, achieving a state-of-the-art accuracy of 98.6%, significantly outperforming traditional thermodynamic (74.1%) and kinetic (82.2%) stability assessments [4]. Complementing this, the Method LLM classifies possible synthetic approaches (e.g., solid-state vs. solution) with 91.0% accuracy, while the Precursor LLM identifies suitable solid-state synthesis precursors with 80.2% success rate [4].

Another approach integrates symmetry-guided structure derivation with Wyckoff encode-based ML models to efficiently locate promising subspaces in the materials universe likely to yield highly synthesizable structures [1]. This synthesizability-driven crystal structure prediction framework successfully reproduced 13 experimentally known XSe structures and filtered 92,310 potentially synthesizable candidates from the 554,054 structures predicted by the GNoME database, demonstrating remarkable potential for prioritizing experimental efforts [1].

Quantitative Performance and Validation Metrics

Evaluating ML model performance requires specialized metrics beyond traditional statistical measures. While root-mean-square error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE) provide insights into prediction accuracy, they do not directly indicate a model's capability to discover novel high-performing materials [23].

Table 2: Metrics for Evaluating ML Performance in Materials Discovery

| Metric | Definition | Interpretation | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery Precision (DP) | Probability that provided candidates will outperform known materials [24] | Directly measures explorative power | Model selection for discovery campaigns |

| Discovery Yield (DY) | Number of high-performing materials discovered during a campaign [23] | Measures throughput of successful discoveries | Comparing different discovery workflows |

| Acceleration Factor | Speedup relative to random screening [24] | Quantifies efficiency gains | Justifying ML adoption |

| Synthesizability Accuracy | Percentage correctness in classifying synthesizable materials [4] | Measures practical utility for experimental guidance | Evaluating synthesis prediction models |

Forward-holdout validation and k-fold forward cross-validation have emerged as crucial validation techniques specifically designed for assessing explorative prediction power [24]. These methods create validation scenarios where the figure-of-merit of samples exceeds that of the training set, better simulating the real-world discovery context where researchers seek materials that outperform known benchmarks.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

The "Lab-in-a-Loop" Framework

The integration of ML with experimental research is embodied in the "lab-in-a-loop" framework, which creates a continuous cycle between computation and experimentation [25]. In this paradigm, initial experimental data trains ML models that generate predictions about promising material candidates or optimal synthesis conditions. These predictions are tested experimentally, generating new data that refines and retrains the models, progressively enhancing their accuracy with each iteration [25]. This approach has been successfully implemented in diverse domains including antibody design, small-molecule drug discovery, and the selection of neoantigens for cancer vaccines [25].

Automated Synthesis Prediction for Metal-Organic Frameworks

For metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), a complete ML workflow for inverse synthesis design has been established, encompassing three critical stages [20]:

Automated Data Mining: Natural language processing techniques, specifically ChemicalTagger software, automatically extract synthesis parameters (metal source, linker, solvent, additive, time, temperature) from scientific literature, creating the SynMOF database [20].

Model Training: Multiple ML models, including random forests and neural networks, are trained on the database to predict synthesis conditions for new MOF structures. Input representations include molecular fingerprints of linkers combined with metal oxidation state encodings [20].

Synthesis Prediction: The trained models predict appropriate synthesis conditions for target MOF structures, outperforming human expert predictions in controlled surveys and providing a foundation for autonomous MOF discovery in automated laboratories [20].

ML-Driven Materials Discovery Workflow

Successful implementation of ML-driven materials discovery requires access to specialized computational tools, datasets, and software resources that collectively enable predictive synthesis modeling.

Table 3: Essential Resources for ML-Driven Materials Discovery

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Key Function | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Databases | Materials Project, ICSD, CoRE MOF [26] | Provides training data on known structures and properties | JSON/API, CIF files |

| Property Prediction | P2MAT [22] | Predicts melting points, boiling points from SMILES | Standalone application |

| Synthesizability Frameworks | CSLLM [4] | Predicts synthesizability, methods, and precursors | Web interface |

| MOF Synthesis Prediction | MOF Synthesis Predictor [20] | Recommends MOF synthesis conditions | Web tool (mof-synthesis.aimat.science) |

| Benchmarking Platforms | Matbench [26] | Standardized evaluation of model performance | Python library |

Case Studies and Experimental Validation

Successful Applications Across Material Classes

The ML-driven paradigm has demonstrated remarkable success across diverse material systems. For inorganic crystals, the CSLLM framework was applied to assess the synthesizability of 105,321 theoretical structures, successfully identifying 45,632 synthesizable candidates [4]. These promising materials subsequently had 23 key properties predicted using accurate graph neural network models, creating a comprehensive pipeline from synthesizability assessment to property screening [4].

In a separate study focusing on XSe compounds, a synthesizability-driven crystal structure prediction framework successfully reproduced 13 experimentally known structures and identified three promising HfV₂O₇ candidates exhibiting high synthesizability, presenting viable targets for experimental realization [1]. These candidates are potentially associated with experimentally observed temperature-induced phase transitions, highlighting how ML can guide experimentation toward materials with interesting functional properties [1].

Integration in Drug Discovery Pipelines

The pharmaceutical industry has embraced similar approaches to overcome development bottlenecks. Insilico Medicine's TNIK inhibitor, INS018_055, progressed from target discovery to Phase II clinical trials in approximately 18 months using generative AI integrated with traditional medicinal chemistry—significantly faster than conventional timelines [21]. This acceleration demonstrates the profound impact of AI/ML integration on research and development efficiency, although challenges remain as evidenced by Exscientia's DSP-1181, which was discontinued after Phase I despite a favorable safety profile, highlighting that accelerated discovery does not guarantee clinical success [21].

CSLLM Framework for Synthesis Prediction

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant progress, ML-driven materials discovery faces several persistent challenges. Data quality and scarcity remain fundamental limitations, particularly for experimental synthesis data which is often buried in unstructured laboratory notebooks [20]. Model interpretability and explainability continue to present hurdles for widespread adoption, as researchers need to understand the rationale behind ML recommendations to trust and act upon them [21]. Furthermore, the problem of out-of-distribution generalization—where models perform poorly on chemical spaces not represented in training data—requires ongoing attention through techniques like transfer learning and domain adaptation [21].

The future trajectory of the field points toward increased integration of autonomous robotic laboratories capable of executing experiments predicted by ML models with minimal human intervention [5]. The emergence of agentic AI systems that can autonomously navigate entire discovery pipelines represents another frontier, potentially further reducing the interval between hypothesis generation and experimental validation [21]. As these technologies mature, the paradigm of materials discovery will continue shifting from serendipitous observation to engineered design, fundamentally transforming our approach to creating the next generation of functional materials.

The transition from trial-and-error to targeted discovery through machine learning represents a fundamental transformation in materials science and drug development. By leveraging sophisticated algorithms trained on expansive materials databases, researchers can now predict synthesizable materials and their optimal preparation routes with remarkable accuracy before setting foot in the laboratory. Frameworks like CSLLM for inorganic crystals and automated synthesis prediction for MOFs demonstrate the practical implementation of this paradigm, achieving prediction accuracies exceeding 90% in many cases [4] [20]. While challenges surrounding data quality, model interpretability, and clinical translation persist, the continued refinement of ML approaches and their tighter integration with automated experimentation promises to further accelerate the design-discovery-development cycle, ultimately delivering innovative materials and therapeutics to address pressing global challenges.

Core ML Architectures and Workflows for Predicting Synthesizable Materials

In the data-driven paradigm of modern materials science, machine learning (ML) models are only as effective as the data they process. The foundational step of converting a material's atomic structure into a numerical representation—a process termed structural featurization—is therefore critical for the accurate prediction of new synthesizable materials. This process involves creating a structured digital representation that encodes a material's chemical composition, atomic coordinates, and bonding environments into a format digestible by ML algorithms. The central challenge lies in designing representations that are both computationally manageable and rich enough to capture the physical and chemical features that govern a material's stability and properties. The choice of featurization method directly influences an ML model's ability to learn the complex relationships on the potential energy surface, ultimately determining the success of computational predictions in guiding experimental synthesis.

This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of the predominant featurization schemes used for crystalline and polycrystalline materials, detailing their theoretical underpinnings, implementation protocols, and integration into ML-driven discovery pipelines. By framing these technical details within the broader thesis of predicting synthesizable materials, this review aims to equip researchers with the knowledge to select, implement, and advance featurization techniques that bridge the gap between computational prediction and experimental realization.

Core Featurization Methodologies

The quest to represent atomic structures for machine learning has led to the development of several sophisticated methodologies. These can be broadly categorized into graph-based, image-based, and descriptor-based approaches, each with distinct strengths for capturing different aspects of structural information.

Graph-Based Representations

Graph-based representations conceptualize a crystal structure as a mathematical graph, offering a natural and powerful way to describe atomic connectivity and local environments.

Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Networks (CGCNN)

The Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Network (CGCNN) is a seminal framework that considers crystal topology to build undirected multigraphs for efficient property prediction [27]. In this construct, atoms are represented as nodes, and the chemical bonds between them are represented as edges. The node feature vector vi typically includes atomic properties such as element type, number of valence electrons, and atomic radius. The edge feature vector ukij between atom i and its neighboring atom j encodes interatomic relationship information, most critically the distance between the atoms, which is often expanded using a basis function like a Bessel function or Gaussian radial basis functions to facilitate learning.

A critical mathematical operation in graph networks is the message-passing or graph convolution step, which updates node embeddings by aggregating information from neighboring nodes. For a graph convolutional network (GCN), this update for the (l+1)-th layer can be represented as:

h_i^(l+1) = σ( Σ_(j∈N(i)) (1 / √(d_i * d_j)) * h_j^(l) * W^(l) )

where h_i^(l) is the feature vector of node i at layer l, N(i) is the set of neighbors of node i, d_i and d_j are the degrees of nodes i and j respectively, W^(l) is a trainable weight matrix, and σ is a non-linear activation function [28]. This formulation allows each atom to gather information from its local coordination environment, enabling the network to learn from both atomic features and the structure's topology.

Molecular Crystal Graph Networks (MolXtalNet)

For molecular crystals, the MolXtalNet framework extends graph-based learning by featurizing the entire unit cell structure [29]. This approach addresses the dual challenge of capturing both intramolecular bonding (within molecules) and intermolecular interactions (between molecules) that define crystal packing and stability. The model uses deep graph neural networks (DGNNs) where nodes represent atoms, and edges are established between atoms within a specified cutoff distance r_c. These edges are featurized with a spatial embedding function that encodes their relative 3D positions. After multiple message-passing steps, the model aggregates information from all nodes to a single vector representing the entire crystal graph, which can then be used for stability scoring (MolXtalNet-S) or property prediction such as density (MolXtalNet-D) [29].

Polycrystalline Microstructure Graphs

Beyond atomic crystals, graph representations are equally powerful for polycrystalline materials. Here, the graph structure shifts from atoms to grains. Each grain in a microstructure becomes a node, with its feature vector storing physical characteristics such as three Euler angles (for grain orientation), grain size (often as voxel count), and the number of neighboring grains [28]. The adjacency matrix A defines the connectivity, where A_ij = 1 if grain i and grain j are in physical contact (neighbors), and 0 otherwise. The resulting graph G = (F, A), where F is the feature matrix for all grains, allows GNNs to incorporate not only the physical features of individual grains but also their interactions, which critically determine macroscopic material properties like magnetostriction [28].

Table 1: Summary of Graph-Based Featurization Approaches

| Representation Type | Node Definition | Edge Definition | Key Features Encoded | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal Graph (CGCNN) | Atoms | Chemical bonds | Interatomic distances, atomic properties | Formation energy, bandgap prediction [27] |

| Molecular Crystal Graph (MolXtalNet) | Atoms | Atoms within cutoff r_c |

Intra- & intermolecular distances, atomic properties | Crystal stability ranking, density prediction [29] |

| Microstructure Graph | Grains | Neighboring grains | Grain orientation, size, neighbor count | Magnetostriction, mechanical properties [28] |

Image and Voxel-Based Representations

Image-based representations render crystal structures into 2D or 3D pixel arrays (voxels), leveraging the powerful pattern recognition capabilities of convolutional neural networks (CNNs).

Diffraction Pattern Images

A highly effective method for global symmetry recognition involves converting a 3D crystal structure into a 2D diffraction pattern image [30]. The process begins by simulating the scattering of an incident plane wave through the crystal. The amplitude Ψ from scattering by N_a atoms of species a at positions x_j^(a) is calculated as:

Ψ(q) = r^(-1) * Σ_a [ f_a(λ,θ) * Σ_(j=1)^(N_a) r_0 * exp(-i q ⋅ x_j^(a)) ]

where q is the scattering wave vector, r_0 is the Thomson scattering length, and f_a(λ,θ) is the x-ray form factor [30]. The intensity I(q) on the detector is then I(q) = A ⋅ Ω(θ) * |Ψ(q)|^2, where Ω(θ) is the solid angle. To create a robust image invariant to orientation, the structure is rotated ±45° about each of the three crystal axes, and the diffraction patterns for these rotations are superimposed into a single RGB image. This representation is exceptionally robust to structural defects like atomic displacements and vacancies, maintaining high classification accuracy even at significant defect concentrations [30].

3D Voxel Grids

For polycrystalline materials, microstructures are often directly represented as 3D voxel arrays. Each voxel is associated with a vector storing the physical features (e.g., crystal orientation) present in that volume [28]. While this raw data format is high-dimensional, CNNs can automatically learn low-dimensional embeddings (feature maps) through convolutional and pooling operations. However, a significant limitation is that these representations typically do not explicitly encode the adjacency relations between grains, which can hinder the model's ability to account for grain boundary interactions that are critical to material properties.

Skeletal Representations

An innovative approach to achieve extreme data compression while retaining topological information is the skeletal representation of microstructures [31]. This method uses skeletonization to reduce a two-phase microstructure to a set of skeletal branches and nodes, achieving a reduction in required variables by two orders of magnitude compared to pixel-based representation. From this skeleton, a suite of morphological and topological descriptors can be seamlessly computed, including the number and length of branches, number of intersections, and domain widths. This descriptor-based representation is sufficient to capture structure-property relationships for tasks like predicting material performance, with the added benefit of significantly reduced computational storage and processing requirements [31].

Geometric and Topological Descriptors

Beyond graphs and images, materials can be featurized using mathematical descriptors that capture specific structural aspects.

Radial Distribution Functions

Radial distribution functions (RDF) and related crystal fingerprinting methods are purely structure-based approaches that model the distribution of interatomic distances within a crystal [29]. These methods exploit the observation that intermolecular distances are similar between atoms in similar environments. While early approaches struggled with the combinatorial explosion of atom-pair combinations and were limited to two-body correlations, modern deep learning models can overcome these limitations by capturing atomic environments in a continuous representation and learning high-order correlations [29].

Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions (SOAP)

The SOAP descriptor provides a continuous and differentiable representation of local atomic environments by building a density-based fingerprint for each atom using a smooth Gaussian at each atomic position. The resulting descriptor is invariant to rotations, translations, and permutations of like atoms, making it particularly valuable for comparing structural similarity and building ML force fields.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Implementing these featurization methods requires careful experimental design. Below are detailed protocols for key applications.

Protocol: Crystal Structure Prediction with SCCOP

The Symmetry-based Combinatorial Crystal Optimization Program (SCCOP) integrates graph featurization with global optimization for crystal structure prediction [27].

- Initial Structure Generation: Generate initial crystal structures using 17 plane space groups, introducing perturbations in the z-direction to account for puckered structures.

- Graph Featurization: Convert each generated structure into a crystal graph using the CGCNN method, creating nodes (atoms) and edges (bonds) with features including atomic properties and interatomic distances.

- Energy Prediction: Use a pre-trained GNN model as a surrogate for DFT to predict the formation energy of each featurized structure.

- Bayesian Optimization: Employ Bayesian optimization to explore the potential energy surface and suggest new candidate structures likely to be at the global minimum.

- Structure Refinement: Apply ML-accelerated simulated annealing to the most promising candidates, followed by a limited number of DFT calculations for final validation and energy evaluation.

- Feature Analysis: Use a feature additive attribution model (e.g., SHAP) on the graph representations to identify which structural features contribute most to the predicted energy and electronic properties.

This workflow has demonstrated a 10-fold speed increase while maintaining accuracy comparable to conventional DFT-based methods like genetic algorithms (GA) and particle-swarm optimization (PSO) [27].

Protocol: Stability Ranking of Molecular Crystals with MolXtalNet-S

For ranking the stability of molecular crystal candidates, the MolXtalNet-S framework provides a rapid assessment [29].

- Data Set Construction: Curate a large and diverse set of known molecular crystal structures from databases like the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD). Generate "fake" decoy structures through random sampling or molecular dynamics to create negative examples.

- Graph Construction: For each crystal (both real and fake), build a molecular graph where nodes are atoms, and edges connect atoms within a specified cutoff distance

r_c. Featurize nodes with atomic properties and edges with spatial embeddings. - Model Training: Train a deep graph neural network (DGNN) to discriminate between stable experimental structures and unstable decoys. The model learns to assign a higher stability score to real structures.

- Validation: Validate the model on blind test sets, such as submissions to the Cambridge Structural Database Blind Tests 5 and 6, to ensure generalizability.

- Deployment: Integrate the trained MolXtalNet-S model into a crystal structure prediction pipeline to rapidly score/filter thousands of candidate structures before passing the most promising ones to more expensive quantum chemistry calculations.

Workflow Visualization: ML-Driven Materials Discovery Pipeline

The following diagram illustrates the integrated role of structural featurization within a complete ML-driven materials discovery pipeline, from initial structure generation to final experimental synthesis.

(Diagram 1: Integrated materials discovery workflow showing the central role of featurization.)

Successful implementation of structural featurization requires both software tools and computational resources. The table below details key components of the research toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Resources for Structural Featurization and ML-Driven Discovery

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Featurization |

|---|---|---|---|

| CGCNN | Software Library | Property Prediction | Implements crystal graph featurization and convolutional networks [27]. |

| SchNet/PhysNet | Deep Learning Model | Molecular & Crystal Property Prediction | DGNN architectures that featurize atoms as nodes and interactions as edges [29]. |

| Dream.3D | Software | Microstructure Generation | Creates synthetic 3D polycrystalline microstructures for graph or voxel-based featurization [28]. |

| Spglib/AFLOW-SYM | Software Library | Symmetry Analysis | Determines space group symmetry; provides input for symmetry-aware featurization [30]. |

| Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) | Data Repository | Experimental Crystal Structures | Primary source of molecular crystal data for training models like MolXtalNet [29]. |

| VASP | Software | DFT Calculations | Provides accurate ground-truth energies for training surrogate ML models [27] [32]. |

| Robotic Synthesis System | Hardware | High-Throughput Experimentation | Automates material synthesis; provides validation for ML predictions [33] [5]. |

Structural featurization forms the indispensable bridge between the physical reality of atomic arrangements and the computational power of machine learning. As this guide has detailed, the choice of representation—from the chemically intuitive crystal graph to the symmetry-sensitive diffraction image—profoundly shapes a model's ability to predict stable, synthesizable materials. The ongoing integration of these featurization techniques within active learning loops and autonomous experimental platforms, such as the CRESt system [33], is poised to further accelerate the discovery cycle. By enabling models to learn directly from structural data while incorporating domain knowledge, these advanced featurization methods are transforming materials discovery from a domain guided by intuition and trial-and-error to one driven by computationally-enlightened design.

Inverse design represents a paradigm shift in materials science and drug development. Traditional design follows a forward path, where a known chemical structure is analyzed to predict its properties. Inverse design, however, starts with a set of desired properties and aims to identify the optimal material or molecular structure that fulfills them [34]. This approach is inherently ill-posed, as multiple structures can potentially satisfy a single set of property requirements, making the search space vast and complex [34]. Machine learning (ML), particularly deep generative models, has emerged as a powerful tool to navigate this complex chemical space efficiently, enabling the prediction of new synthesizable materials by learning the underlying structure-property relationships from data [34] [35].

The application of generative AI for inverse design marks the fourth paradigm in materials innovation, unifying theory, experiment, and computer simulation through data-driven discovery [34]. This review provides an in-depth technical guide to three leading generative modeling frameworks—Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), and Diffusion Models—focusing on their principles, applications in inverse design, and detailed experimental protocols for their implementation.

Generative Model Architectures: Principles and Comparisons

Variational Autoencoders (VAEs)

VAEs are latent-variable models that learn a probabilistic mapping between a high-dimensional data space (e.g., molecular structures) and a lower-dimensional latent space [36] [37]. The architecture consists of an encoder and a decoder. The encoder transforms input data into parameters (mean and variance) of a Gaussian distribution in the latent space. The decoder then samples from this distribution to reconstruct the original data [36] [37]. This structure forces the model to learn a continuous, organized latent representation of the data, which is ideal for generating novel designs by interpolating within this space.

However, a key limitation is that VAEs often produce blurry or fuzzy outputs because the reconstruction loss (often L1 or L2) tends to average out fine details, leading to low-fidelity samples [38] [37]. They are also susceptible to "posterior collapse," where the decoder ignores the latent variables, resulting in non-diverse and meaningless generated samples [37].

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

GANs employ an adversarial training framework between two neural networks: a generator and a discriminator [39]. The generator creates synthetic data from random noise, while the discriminator evaluates whether its input is real (from the training data) or fake (from the generator) [39]. This adversarial min-max game drives the generator to produce increasingly realistic samples.

GANs are renowned for their ability to generate high-fidelity, sharp images and have been successfully applied to molecular and materials design [37] [40]. Their significant drawbacks include training instability—requiring careful hyperparameter tuning to maintain balance between the generator and discriminator—and mode collapse, where the generator produces a limited diversity of samples [38] [39] [37].

Diffusion Models

Inspired by non-equilibrium thermodynamics, diffusion models learn data generation by reversing a gradual noising process [41] [42]. The forward diffusion process systematically adds Gaussian noise to a data sample over many steps until it becomes pure noise [42]. The model is then trained to perform the reverse process, learning to iteratively denoise a random seed to generate a coherent data sample [42].

Diffusion models excel at producing high-quality, diverse outputs and offer stable training compared to GANs, as they avoid adversarial competition [38] [42]. Their primary disadvantage is slower inference speed, as generation requires multiple denoising steps (sometimes thousands), which is computationally intensive [39] [37]. Recent advancements, such as latent diffusion, perform the diffusion process in a lower-dimensional latent space to improve efficiency [37].

Table 1: Technical Comparison of Generative Models for Inverse Design

| Aspect | Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) | Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) | Diffusion Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Probabilistic encoding/decoding to a latent space [36] | Adversarial training between generator & discriminator [39] | Iterative denoising of a noisy input [42] |

| Training Stability | Stable and straightforward [38] | Unstable; prone to mode collapse [38] [39] | Stable and predictable [38] [42] |

| Output Fidelity | Lower; often produces blurry outputs [38] [37] | Very high; can produce sharp, realistic samples [38] [37] | High; detailed and diverse samples [38] [42] |

| Output Diversity | High, due to probabilistic latent space [38] | Can be limited due to mode collapse [38] [39] | Very high; captures complex distributions well [39] [42] |

| Inference Speed | Fast (single forward pass) | Very fast (single forward pass) [39] | Slow (requires multiple iterative steps) [39] [37] |

| Primary Inverse Design Use Case | Exploring a continuous latent space of designs [34] | High-fidelity generation for specific target properties [41] | High-quality, diverse design exploration with strong constraints [41] |

Quantitative Performance Analysis in Inverse Design