Machine Learning for Inorganic Material Synthesis: Predicting Precursors and Accelerating Discovery

This article explores the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in predicting synthesis precursors for inorganic materials, a critical bottleneck in materials development.

Machine Learning for Inorganic Material Synthesis: Predicting Precursors and Accelerating Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in predicting synthesis precursors for inorganic materials, a critical bottleneck in materials development. We cover the foundational challenges that make precursor prediction difficult and detail state-of-the-art methodologies, from graph neural networks and large language models to similarity-based recommendation systems. The content also addresses key troubleshooting aspects and optimization techniques, followed by a comparative analysis of different models' performance and validation strategies. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes how these data-driven approaches are poised to significantly accelerate the design of new functional materials for biomedical and clinical applications.

The Synthesis Bottleneck: Why Predicting Inorganic Precursors is a Grand Challenge

The fourth paradigm of materials science, characterized by data-driven and computational approaches, has successfully identified millions of candidate materials with promising properties through high-throughput calculations and machine learning (ML) [1] [2]. However, a critical bottleneck persists in transforming these virtual designs into physically realized materials, as synthesizability remains notoriously difficult to predict [3] [1]. While thermodynamic stability (often measured by energy above the convex hull) provides some guidance, numerous metastable structures are successfully synthesized while many computed-stable materials remain elusive [1]. The central challenge lies in moving beyond thermodynamic assessments to predict feasible synthesis routes, including appropriate precursor materials and reaction conditions – knowledge that traditionally resides in expert experience and dispersed scientific literature [3] [4].

Machine learning, particularly large language models (LLMs) and specialized ranking algorithms, is emerging as a powerful tool to bridge this gap between computational design and experimental realization [1] [4]. This Application Note details the latest frameworks and methodologies for predicting inorganic materials synthesizability and precursors, providing researchers with structured protocols to implement these approaches in their materials discovery pipelines.

Quantifying the Synthesis Prediction Challenge

Current approaches for assessing synthesizability demonstrate varying levels of accuracy, as quantified in recent benchmarking studies:

Table 1: Performance comparison of synthesizability assessment methods

| Method | Accuracy | Scope | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamic Stability (Energy above hull ≥0.1 eV/atom) [1] | 74.1% | 3D crystals | Fails for many metastable yet synthesizable materials |

| Kinetic Stability (Phonon frequency ≥ -0.1 THz) [1] | 82.2% | 3D crystals | Computationally expensive; some synthesizable materials show imaginary frequencies |

| Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning [1] | 87.9% | 3D crystals | Limited by dataset construction |

| Teacher-Student Dual Neural Network [1] | 92.9% | 3D crystals | Architecture complexity |

| Crystal Synthesis LLM (CSLLM) [1] | 98.6% | 3D crystals | Requires substantial data curation and fine-tuning |

The data clearly demonstrates the superiority of specialized ML approaches, particularly LLMs, in predicting synthesizability compared to traditional physical stability metrics.

Core Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM) Framework

The CSLLM framework employs three specialized LLMs to address distinct aspects of the synthesis prediction problem: synthesizability classification, method recommendation, and precursor identification [1].

Protocol 1: Implementing CSLLM for Synthesis Prediction

Objective: Predict synthesizability, synthetic method, and precursors for a target crystal structure using fine-tuned LLMs.

Input Requirements: Crystal structure in CIF or POSCAR format.

Processing Steps:

- Data Curation and Representation:

- Collect balanced dataset of synthesizable (e.g., 70,120 structures from ICSD) and non-synthesizable materials (e.g., 80,000 structures screened via PU learning) [1].

- Convert crystal structures to simplified text representation ("material string"):

SPG | a, b, c, α, β, γ | (AS1-WS1[WP1]), (AS2-WS2[WP2]), ...where SPG=space group, a,b,c=lattice parameters, α,β,γ=angles, AS=atomic symbol, WS=Wyckoff site, WP=Wyckoff position [1]. - Exclude disordered structures and limit to ≤40 atoms and ≤7 elements per structure.

Model Architecture and Training:

- Utilize a transformer-based LLM architecture (e.g., LLaMA) as base model [1].

- Fine-tune three separate models on the text-represented crystal data:

- Synthesizability LLM: Binary classification (synthesizable/non-synthesizable)

- Method LLM: Multi-class classification (solid-state/solution/other)

- Precursor LLM: Sequence generation for precursor identification

- Training parameters: Use nested cross-validation to avoid overfitting [5].

Validation and Testing:

- Evaluate synthesizability prediction accuracy on hold-out test set.

- Assess generalization capability on complex structures with large unit cells.

- Validate precursor predictions against known literature synthesis routes.

Output: Synthesizability probability, recommended synthesis method, and candidate precursors for target material.

Retro-Rank-In for Precursor Recommendation

Retro-Rank-In reformulates precursor recommendation as a ranking problem within a unified materials embedding space, enabling recommendation of novel precursors not seen during training [4].

Protocol 2: Precursor Ranking with Retro-Rank-In

Objective: Rank precursor sets for a target material based on chemical compatibility.

Input Requirements: Target material composition or structure.

Processing Steps:

- Materials Representation:

- Encode both target materials and potential precursors using a composition-level transformer-based encoder [4].

- Generate embeddings in a unified latent space that captures chemical similarity.

Ranker Training:

- Train a pairwise ranking model to evaluate target-precursor compatibility.

- Use negative sampling to address dataset imbalance.

- Incorporate domain knowledge through pretrained material embeddings that implicitly encode formation enthalpies and related properties [4].

Inference and Ranking:

- For a target material, compute similarity scores with all candidate precursors in the embedding space.

- Generate ranked list of precursor sets based on aggregate compatibility scores.

- The framework can recommend precursors not present in the training data, enabling discovery of novel synthesis routes [4].

Output: Ranked list of precursor sets with compatibility scores.

XGBoost for Synthesis Parameter Optimization

Beyond precursor selection, optimizing synthesis parameters is crucial for successful materials realization.

Protocol 3: ML-Guided Optimization of Synthesis Conditions

Objective: Optimize synthesis parameters to maximize yield/quality of target material.

Input Requirements: Historical synthesis data with parameters and outcomes.

Processing Steps:

- Feature Engineering:

- For CVD-grown MoSâ‚‚, identify critical parameters: gas flow rate (Rf), reaction temperature (T), reaction time (t), ramp time (tr), distance of S outside furnace (D), addition of NaCl, and boat configuration (F/T) [5].

- Calculate Pearson's correlation coefficients to eliminate redundant features.

- Define success criteria (e.g., sample size >1μm for "Can grow" classification) [5].

Model Selection and Training:

Experimental Validation:

Output: Optimized synthesis parameters with predicted success probability.

Table 2: Computational and Data Resources for Synthesis Prediction

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Project [6] | Database | Provides calculated properties of inorganic materials for training models | Free via API |

| Text-mined synthesis recipes [3] [7] | Dataset | 31,782 solid-state and 35,675 solution-based synthesis recipes for training ML models | Publicly available |

| CSLLM Framework [1] | Software | Predicts synthesizability, methods, and precursors for crystal structures | Research use |

| Retro-Rank-In [4] | Algorithm | Ranks precursor sets for target materials, including novel precursors | Research use |

| XGBoost [5] | Algorithm | Optimizes synthesis parameters through supervised learning | Open source |

Implementation Workflow and Integration

A comprehensive synthesis prediction pipeline integrates multiple computational approaches:

Future Directions and Challenges

While current ML approaches show remarkable accuracy, several challenges remain. Data quality and coverage limitations persist, with text-mined datasets often lacking the volume, variety, veracity, and velocity needed for optimal model training [3]. Future efforts should focus on developing standardized data formats for synthesis reporting, incorporating negative results, and creating specialized foundation models for materials science [8] [2]. The integration of AI-guided synthesis planning with automated laboratories represents a promising direction for closed-loop materials discovery and development [9] [2].

The discovery of novel inorganic materials is pivotal for technological advancement, yet a significant bottleneck persists between computational prediction and experimental realization. Traditional approaches have heavily relied on thermodynamic stability metrics, such as energy above the convex hull, as proxies for synthesizability. However, these methods frequently fail to account for the complex kinetic and experimental factors governing solid-state synthesis, resulting in a vast disparity between predicted and synthetically accessible materials [10] [11]. The emergence of machine learning (ML) represents a paradigm shift, enabling researchers to move beyond thermodynamic limitations and integrate diverse data—from historical synthesis records to text-mined literature—to develop more accurate and practical heuristics for predicting synthesis pathways and precursors [1] [12]. This Application Note details the protocols and data-driven frameworks that are bridging this gap, accelerating the transition from theoretical material design to laboratory synthesis.

Recent research has produced a variety of ML models for synthesizability and precursor prediction, each with distinct architectures, data sources, and performance metrics. The table below summarizes the key quantitative findings from recent seminal studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Machine Learning Models for Synthesis Prediction

| Model Name | Model Type / Approach | Key Input Data | Primary Task | Reported Performance / Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSLLM (Synthesizability LLM) [1] | Fine-tuned Large Language Model | Text-represented crystal structures (material strings) | Synthesizability classification of 3D crystals | 98.6% accuracy; significantly outperforms energy above hull (74.1%) and phonon stability (82.2%) |

| SynthNN [10] | Deep Learning (Atom2Vec) | Chemical composition only | Synthesizability classification | 7x higher precision than DFT formation energies; outperformed 20 human experts (1.5x higher precision) |

| ElemwiseRetro [13] | Element-wise Graph Neural Network | Target composition & precursor templates | Precursor set prediction | 78.6% top-1 and 96.1% top-5 exact match accuracy |

| A-Lab [12] | Integrated Autonomous Lab (NLP + Active Learning) | Computed targets, historical data, active learning | Autonomous solid-state synthesis | Successfully synthesized 41 of 58 novel target compounds (71% success rate) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Predicting Synthesizability with Crystal Synthesis LLMs (CSLLM)

The CSLLM framework employs three specialized large language models to predict synthesizability, synthetic methods, and precursors [1].

- A. Data Curation and Text Representation

- Acquire Positive Examples: Obtain 70,120 synthesizable crystal structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD). Filter for structures with ≤40 atoms and ≤7 different elements. Exclude disordered structures.

- Generate Negative Examples: Screen 1,401,562 theoretical structures from databases (e.g., Materials Project) using a pre-trained Positive-Unlabeled (PU) learning model. Select 80,000 structures with the lowest CLscore (e.g., <0.1) as non-synthesizable examples to create a balanced dataset.

- Create Material Strings: Convert crystal structures into a simplified text representation ("material string") to efficiently fine-tune LLMs. The format is:

Space Group | a, b, c, α, β, γ | (AtomSymbol1-WyckoffSite1[WyckoffPosition1,x1,y1,z1]; AtomSymbol2-WyckoffSite2[WyckoffPosition2,x2,y2,z2]; ...).

- B. Model Fine-Tuning and Prediction

- Fine-Tune LLMs: Use the curated dataset of material strings to fine-tune three separate LLMs:

- Synthesizability LLM: Binary classification (synthesizable vs. non-synthesizable).

- Method LLM: Classifies likely synthetic method (e.g., solid-state or solution).

- Precursor LLM: Identifies suitable precursor chemicals.

- Input Target Structure: For a novel target crystal structure, generate its corresponding material string.

- Execute Predictions: Input the material string into the fine-tuned CSLLM models to receive predictions for synthesizability probability, recommended synthesis method, and potential precursor sets.

- Fine-Tune LLMs: Use the curated dataset of material strings to fine-tune three separate LLMs:

Protocol: Autonomous Synthesis with the A-Lab

The A-Lab is an integrated platform that uses AI to plan, execute, and interpret solid-state synthesis experiments [12].

- A. Target Identification and Initial Recipe Generation

- Select Targets: Identify target compounds from computational databases (e.g., Materials Project), focusing on materials predicted to be stable or near-stable (e.g., energy above hull <10 meV/atom) and air-stable.

- Propose Initial Recipes:

- Use a natural language processing (NLP) model trained on scientific literature to propose up to five initial synthesis recipes based on analogy to historically similar materials.

- Use a second ML model, trained on text-mined heating data, to recommend a synthesis temperature.

- B. Robotic Execution and Analysis

- Sample Preparation: A robotic station dispenses, weighs, and mixes precursor powders in an alumina crucible. The mixture is milled to ensure homogeneity and reactivity.

- Heating: A robotic arm loads the crucible into one of four box furnaces for heating according to the proposed temperature profile.

- Characterization: After cooling, the sample is automatically transferred, ground into a fine powder, and characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD).

- C. Active Learning for Recipe Optimization

- Analyze Outcome: ML models analyze the XRD pattern to identify phases and determine the target yield via automated Rietveld refinement.

- Iterate if Needed: If the target yield is below a threshold (e.g., <50%), the active learning algorithm (ARROWS³) proposes new recipes. This algorithm uses observed reaction intermediates and ab initio reaction energies to avoid low-driving-force pathways and suggest more optimal precursor combinations and temperatures.

- Terminate: The process continues until the target is successfully synthesized or all viable recipes are exhausted.

Protocol: Precursor Prediction with ElemwiseRetro

This protocol uses a graph neural network to predict precursor sets for a target inorganic composition [13].

- A. Problem Formulation and Template Library Construction

- Categorize Elements: For a target composition, classify elements as "source elements" (typically metals, metalloids, P, S, Se; must be provided by precursors) or "non-source elements" (can come from/react with the environment).

- Build Template Library: From a curated dataset of inorganic reactions (e.g., 13,477 recipes), extract a library of common precursor templates (anionic frameworks paired with source elements). A typical library may contain ~60 such templates.

- B. Model Application and Precursor Selection

- Encode Target: Represent the target composition as a graph, with node features from pre-trained inorganic compound representations.

- Apply Source Mask: Use a source element mask to highlight which elements in the target require precursor sources.

- Predict Precursors: Feed the encoded graph into the ElemwiseRetro model. The model predicts the most probable precursor template for each source element.

- Rank Recipes: Calculate the joint probability of the predicted precursor sets. Rank the final synthesis "recipes" by this probability score, which correlates with prediction confidence and can be used to prioritize experimental trials.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

The following table outlines essential components and software used in the development and application of ML-guided synthesis platforms.

Table 2: Essential Resources for ML-Guided Materials Synthesis

| Item / Resource | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Powders | Starting materials for solid-state reactions | High-purity, commercially available oxides, carbonates, etc. [12] |

| Alumina Crucibles | Containers for high-temperature reactions | Inert, withstand repeated heating cycles [12] |

| Robotic Furnaces | Automated heating under controlled profiles | The A-Lab used four box furnaces for parallel processing [12] |

| X-ray Diffractometer | Primary characterization for phase identification | Integrated with an automated sample preparation and loading system [12] |

| Crystallographic Databases | Source of positive data for model training | Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [1] [10] |

| Theoretical Databases | Source of candidate structures and energies | Materials Project, OQMD, JARVIS, Computational Materials Database [1] [12] |

| Text-Mined Synthesis Data | Training data for NLP recipe-suggestion models | Data extracted from millions of scientific publications [12] |

| Fine-Tuned LLMs (e.g., CSLLM) | Predicting synthesizability, method, and precursors | Requires domain-specific fine-tuning on crystal structure data [1] |

| Graph Neural Networks | Predicting precursor sets from composition | ElemwiseRetro model uses element-wise formulation [13] |

| Hdac6-IN-39 | Hdac6-IN-39, MF:C16H15F4N5O4S2, MW:481.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Hdac-IN-41 | Hdac-IN-41, MF:C20H22N4O6S, MW:446.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

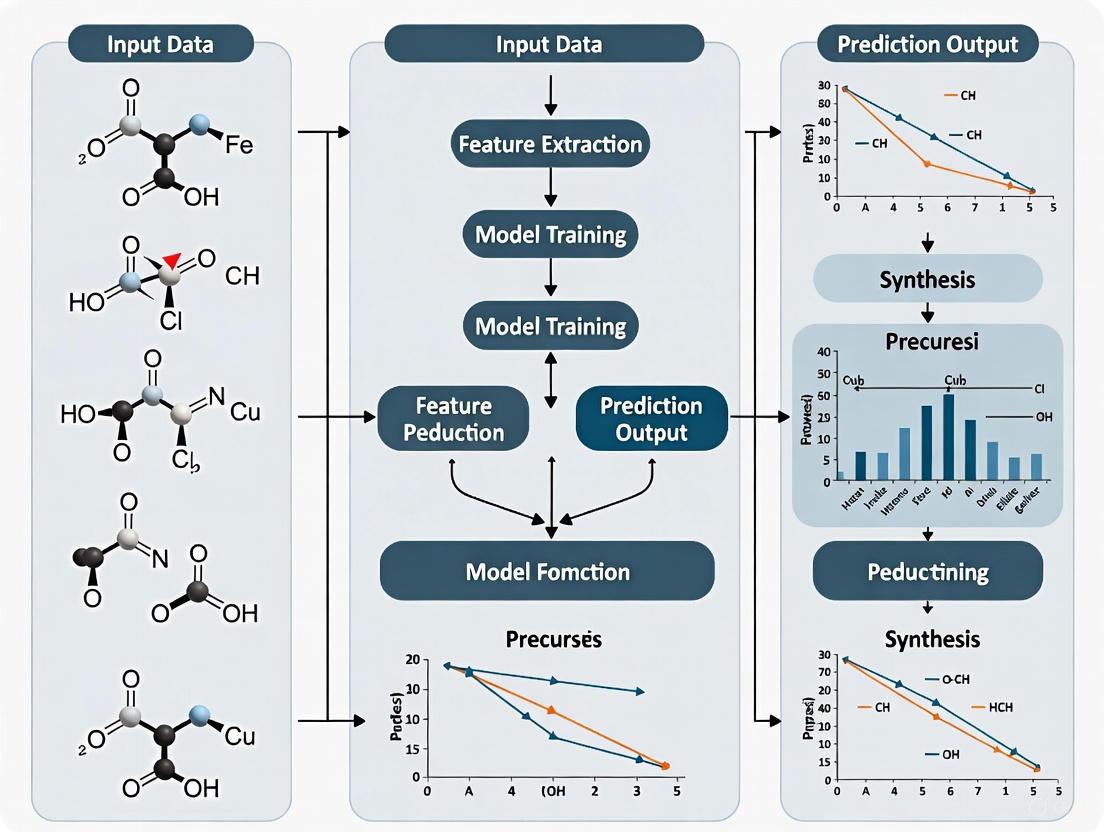

Workflow and System Diagrams

ML-Driven Synthesis Prediction Workflow. This diagram illustrates the integrated computational and experimental pipeline for predicting and realizing novel inorganic materials, from target input to synthesized material.

CSLLM Prediction Framework. This diagram outlines the process flow for the Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM), which uses a simplified text representation of crystal structures to make specialized predictions.

The discovery and synthesis of novel inorganic materials are pivotal for advancements in technologies ranging from batteries to pharmaceuticals. However, the ability to computationally design materials has far outpaced the development of synthesis routes to create them, creating a critical bottleneck in the materials innovation pipeline [14]. This challenge stems from a fundamental gap: unlike organic chemistry with its well-understood reaction mechanisms, inorganic material synthesis lacks a comprehensive theoretical foundation, relying heavily on empirical knowledge and expert intuition [10].

This application note details how text-mining scientific literature constructs the large-scale, structured knowledge bases necessary to power machine learning (ML) models for predicting inorganic material synthesis. By converting unstructured synthesis descriptions in millions of published articles into codified, machine-readable data, researchers can uncover the complex relationships between target materials, their precursors, and reaction conditions. We frame this methodology within a broader thesis on predicting inorganic material synthesis precursors, demonstrating how a robust data foundation enables the development of accurate, reliable, and interpretable ML models.

The Text-Mining Pipeline: From Unstructured Text to Structured Knowledge

The process of transforming free-text synthesis paragraphs into a structured knowledge base involves a multi-step natural language processing (NLP) pipeline. The workflow, illustrated in Figure 1, is designed to automatically identify and extract key entities and their relationships from scientific text.

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end text-mining pipeline for building a synthesis knowledge base.

Figure 1. Workflow for Text-Mining Synthesis Recipes. The pipeline processes scientific articles to automatically extract structured synthesis information from unstructured text [14].

Protocol: Implementation of the Text-Mining Pipeline

Objective: To automatically extract structured solid-state synthesis recipes from the text of scientific publications.

Materials and Reagents:

- Computational Hardware: A high-performance computing cluster or workstation with substantial memory (≥64 GB RAM) is recommended for processing large document corpora.

- Software Environment: Python 3.7+ with the following core libraries:

- Scrapy: For web-scraping and content acquisition from publisher websites.

- SpaCy & Stanza: For foundational NLP tasks like tokenization, part-of-speech tagging, and dependency parsing [15].

- ChemDataExtractor: A toolkit specifically designed for processing chemical information from text [14].

- MongoDB: A document-oriented database for storing parsed article text and associated metadata.

Methods:

Content Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Web Scraping: Use the Scrapy framework to systematically download full-text journal articles in HTML/XML format from major publishers (e.g., Springer, Wiley, Elsevier, RSC). Focus on post-2000 literature to avoid complications with PDF parsing [14].

- Text Extraction: Develop a custom parser to convert article markup into raw text paragraphs while preserving section headings and document structure. Store all data in a MongoDB database.

Paragraph Classification

- Objective: Identify paragraphs describing solid-state synthesis methodologies, filtering out irrelevant text (e.g., theoretical background, results discussion).

- Procedure:

- Implement a two-step classifier. First, use an unsupervised algorithm to cluster keywords and generate probabilistic topic assignments.

- Subsequently, train a supervised Random Forest classifier on a manually annotated set of ~1,000 paragraphs per label (e.g., "solid-state," "hydrothermal," "sol-gel," "none") [14].

- Apply the trained model to classify all paragraphs, retaining only those labeled "solid-state synthesis" for subsequent analysis.

Material Entity Recognition (MER)

- Objective: Identify and categorize all material mentions in a synthesis paragraph as "TARGET," "PRECURSOR," or "OTHER."

- Procedure:

- Implement a Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory with Conditional Random Field (BiLSTM-CRF) neural network model.

- Train the model on a manually annotated dataset of 834 solid-state synthesis paragraphs. Word embeddings should be generated using a Word2Vec model pre-trained on a corpus of ~33,000 synthesis paragraphs [14].

- For the classification step (TARGET vs. PRECURSOR), replace each material with a

<MAT>token and augment the word representation with chemical features (e.g., number of metal/metalloid elements, organic flags).

Synthesis Operation and Condition Extraction

- Objective: Identify key synthesis steps (e.g., mixing, heating) and their associated parameters (temperature, time, atmosphere).

- Procedure:

- Train a neural network to classify sentence tokens into operation categories:

MIXING,HEATING,DRYING,SHAPING,QUENCHING, orNOT OPERATION. - Use dependency tree parsing from the SpaCy library to identify relationships between operation verbs and their parameters [14] [15].

- Apply regular expressions to extract numerical values for temperature and time, and keyword matching to identify atmosphere conditions from the same sentence as the operation.

- Train a neural network to classify sentence tokens into operation categories:

Balanced Equation Generation

- Objective: Derive a balanced chemical equation for the synthesis reaction.

- Procedure:

- Pass all extracted material strings through a "Material Parser" to convert text descriptions into standardized chemical formulas.

- Solve a system of linear equations asserting the conservation of each chemical element, including a set of "open" compounds (e.g., Oâ‚‚, COâ‚‚) that can be absorbed or released [14].

Quantitative Outcomes of Text-Mining

The application of the described pipeline to a large corpus of scientific literature yields quantitative datasets that form the bedrock for subsequent machine learning. The table below summarizes the scale and content of a publicly available text-mined dataset [14].

Table 1. Summary of a Text-Mined Solid-State Synthesis Dataset.

| Metric | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Total Processed Paragraphs | 53,538 | Number of paragraphs identified as describing solid-state synthesis [14] |

| Extracted Synthesis Entries | 19,488 | Number of unique, codified synthesis recipes generated [14] |

| Key Data per Entry | Target Material, Starting Compounds, Synthesis Operations, Operation Conditions, Balanced Chemical Equation | The structured information captured for each synthesis [14] |

This data enables the transition from heuristic rules to data-driven models. For instance, analysis of known synthesized materials reveals that only 37% adhere to the simple charge-balancing rule often used as a synthesizability heuristic, underscoring the limitation of such proxies and the need for more sophisticated, data-driven approaches [10].

Building Predictive Models on the Knowledge Base

With a structured knowledge base in place, machine learning models can be trained to predict synthesis pathways. A key advancement involves framing the problem as a retrosynthetic task, predicting precursors for a target material.

Protocol: Element-wise Graph Neural Network for Retrosynthesis

Objective: Predict a set of precursor materials and a reaction temperature for a target inorganic crystalline material.

Materials and Reagents:

- Training Data: The text-mined dataset of synthesis reactions (e.g., from Table 1), curated to ~13,477 entries for model training [13].

- Software Libraries:

- PyTorch Geometric or Deep Graph Library (DGL): For implementing graph neural networks.

- Mat2Vec: or other algorithms for generating composition-based material embeddings [10].

Methods:

Problem Formulation & Template Library Creation

- Categorize elements into "source elements" (must be provided by precursors, e.g., metals) and "non-source elements" (can come from the environment, e.g., O).

- From the training data, automatically extract a library of ~60 "precursor templates"—common anionic frameworks (e.g., carbonates, oxides) that pair with source elements to form realistic precursor compounds [13].

Model Architecture (ElemwiseRetro)

- Represent the target material's composition as a graph, with nodes for each element.

- Use an element-wise Graph Neural Network (GNN) to learn the interactions between elements in the target material.

- Apply a "source element mask" to the GNN's output to focus on relevant elements.

- For each source element, a classifier head predicts the most likely precursor template from the library.

- The joint probability of a full precursor set is calculated by combining the probabilities of the individual template predictions [13].

Temperature Prediction

- Sequentially connect the precursor prediction model to a separate regression model that takes the encoded target material and predicted precursors as input to output a recommended synthesis temperature [13].

Model Validation

- Perform a "time-split" validation, training the model on data from before 2016 and testing its ability to predict synthesis routes for materials reported after 2016. This assesses the model's predictive power for truly novel materials [13].

The performance of this model compared to a simple statistical baseline is quantified in Table 2, demonstrating the value of the learned representations.

Table 2. Performance Comparison of Retrosynthesis Models.

| Top-k Accuracy | ElemwiseRetro Model | Popularity-Based Baseline |

|---|---|---|

| k=1 | 80.4% | 50.4% |

| k=3 | 92.9% | 75.1% |

| k=5 | 95.8% | 79.2% |

Data sourced from a publication-year-split test, demonstrating the model's generalizability [13].

Workflow Integration and Confidence Estimation

A critical feature of a robust predictive system is its ability to estimate its own confidence. The probability score output by the ElemwiseRetro model is highly correlated with prediction accuracy, providing a practical tool for prioritizing experimental efforts [13]. The integration of text-mined data, ML prediction, and experimental validation into a cohesive workflow is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Closed-Loop Workflow for Synthesis Prediction. A knowledge base fuels ML models that generate prioritized predictions, which are then validated experimentally, potentially feeding new data back into the knowledge base [14] [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3. Essential Computational Reagents for Text-Mining and Prediction.

| Reagent / Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Named Entity Recognition (NER) Model | Identifies and classifies material names (e.g., "LiCoOâ‚‚") and other key terms in text. | Pre-trained models like those in Stanza or SciSpacy offer a starting point, but domain-specific fine-tuning on annotated synthesis paragraphs is crucial for high accuracy [14] [15]. |

| Precursor Template Library | A finite set of validated anionic frameworks (e.g., oxide, carbonate, nitrate) used to construct realistic precursor compounds. | Automatically mined from existing reaction datasets. Using a library ensures predicted precursors are charge-balanced and commercially plausible, avoiding unrealistic suggestions [13]. |

| Material Composition Embedder | Converts a chemical formula into a numerical vector that captures chemical similarity. | Tools like mat2vec or the atom2vec method used in SynthNN provide these representations, allowing models to learn from the entire space of known materials [10]. |

| Text-Mined Synthesis Knowledge Base | The central structured repository of synthesis protocols, containing targets, precursors, operations, and conditions. | Serves as the ground-truth dataset for both training ML models and benchmarking new prediction algorithms. Data quality is paramount [14]. |

| Nudifloside B | Nudifloside B, MF:C43H60O22, MW:928.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Sibiricaxanthone B | Sibiricaxanthone B, MF:C24H26O14, MW:538.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Defining Source Elements, Precursor Templates, and Synthesis Recipes

The discovery and development of new inorganic materials are pivotal for advancements in energy storage, electronics, and catalysis. However, a significant bottleneck exists in translating computationally designed materials into physically realized compounds, as synthesis pathways are often non-obvious and determined by complex kinetic and thermodynamic factors [16]. The process of retrosynthesis—strategically planning the synthesis of a target compound from simpler, readily available precursors—is a critical but challenging task in inorganic chemistry [17]. Traditional methods often rely on trial-and-error experimentation or the specialized knowledge of expert chemists, which does not scale for the rapid exploration of vast chemical spaces [10]. This application note frames the key concepts of Source Elements, Precursor Templates, and Synthesis Recipes within the emerging paradigm of machine learning (ML)-assisted synthesis planning, providing a structured framework to accelerate the predictive synthesis of inorganic materials.

Key Conceptual Definitions

Source Elements

Source Elements refer to the fundamental chemical building blocks, typically elements or simple ions, from which more complex precursor compounds and final target materials are derived. In ML-driven synthesis planning, source elements are often represented as learned embeddings within a model. For instance, the atom2vec framework represents each element by a vector whose values are optimized during model training, allowing the algorithm to learn chemical relationships and affinities directly from data on synthesized materials [10]. This data-driven representation captures complex patterns beyond simple periodic trends, enabling the model to infer which combinations of source elements are most likely to form viable precursors and, ultimately, synthesizable materials.

Precursor Templates

Precursor Templates are the immediate chemical compounds, often simple binaries or ternary phases, that are combined in a solid-state or solution-based reaction to form the target material. Identifying the correct precursors is a central task in retrosynthesis. Machine learning approaches reformulate this problem from a multi-label classification task into a ranking problem. For example, the Retro-Rank-In framework embeds both target and precursor materials into a shared latent space and learns a pairwise ranker to assess the suitability of precursor pairs for a given target [17]. This allows the model to generalize and suggest viable precursor combinations it has not encountered during training, such as successfully predicting the precursor pair CrB + Al for the target Cr2AlB2 [17].

Synthesis Recipes

A Synthesis Recipe is a complete set of instructions for synthesizing a target material, encompassing not only the identity and stoichiometry of the precursors but also the detailed sequence of operations and conditions required. These operations include mixing, heating (calcination/sintering), drying, and quenching, each associated with specific parameters like temperature, time, and atmosphere [3]. Machine learning models can predict these parameters; for instance, transformer-based models like SyntMTE, when augmented with language model-generated data, can predict calcination and sintering temperatures with a mean absolute error as low as 73-98 °C [18]. The recipe thus represents the final, actionable output of a synthesis planning pipeline.

Quantitative Performance of ML Approaches

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Selected Synthesis Prediction Models

| Model Name | Primary Task | Key Performance Metric | Reported Result | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retro-Rank-In [17] | Precursor Recommendation | Generalization to unseen reactions | Correctly predicted CrB + Al for Cr2AlB2 |

Ranking-based approach on a bipartite graph |

| CSLLM [19] | Synthesizability Prediction | Accuracy | 98.6% | Fine-tuned Large Language Model (LLM) on crystal structures |

| CSLLM [19] | Precursor Prediction | Success Rate | 80.2% | Specialized LLM for precursors |

| SynthNN [10] | Synthesizability Prediction | Precision vs. Human Experts | 1.5x higher precision than best human expert | Composition-based deep learning model |

| Ensemble LMs [18] | Precursor Recommendation | Top-1 Accuracy | 53.8% | Ensemble of off-the-shelf language models (e.g., GPT-4.1) |

| Ensemble LMs [18] | Precursor Recommendation | Top-5 Accuracy | 66.1% | Ensemble of off-the-shelf language models |

| SyntMTE [18] | Temperature Prediction | Mean Absolute Error (Sintering) | 73 °C | Transformer model pretrained on real & synthetic data |

Experimental Protocols for ML-Driven Synthesis Prediction

Protocol: Precursor Recommendation with a Ranking Model

This protocol outlines the process for training and applying a ranking model, like Retro-Rank-In, to recommend precursor combinations for a target inorganic material [17].

Data Collection and Bipartite Graph Construction:

- Procure a dataset of verified synthesis reactions, listing target materials and their corresponding precursor sets. Public text-mined datasets, despite known limitations, can serve as a starting point [3].

- Construct a bipartite graph where one set of nodes represents target materials and the other represents precursor compounds. Edges connect a target to its known precursors.

Material Embedding:

- Represent each material (both targets and precursors) as a numerical vector (embedding). This can be achieved using a pre-trained material representation model, such as a crystal graph neural network or a transformer model like MTEncoder, which captures compositional and structural features [17] [18].

Model Training and Ranking:

- Train a pairwise ranking model (e.g., a neural network) to operate on the bipartite graph. The model learns to score the compatibility between a target material embedding and a candidate precursor embedding.

- The learning objective is to maximize the score for true precursor pairs from the training data relative to randomly sampled, incorrect pairs.

Inference and Precursor Suggestion:

- For a new target material, generate its embedding.

- Score the target against a large candidate pool of potential precursor embeddings.

- Output a ranked list of the top-k most promising precursor combinations based on the model's scores for experimental validation.

Protocol: Synthesizability Prediction with a Fine-Tuned LLM

This protocol describes the workflow for the Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM) framework to predict whether a hypothetical crystal structure is synthesizable [19].

Dataset Curation for Positive and Negative Examples:

- Positive Examples: Collect experimentally confirmed, synthesizable crystal structures from databases like the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD). Filter for ordered structures with a manageable number of atoms/elements (e.g., ≤ 40 atoms, ≤ 7 elements).

- Negative Examples: Generate a set of non-synthesizable structures. This is a key challenge. One method is to use a pre-trained Positive-Unlabeled (PU) learning model to assign a synthesizability score (CLscore) to a large pool of theoretical structures from sources like the Materials Project. Structures with the lowest scores (e.g., CLscore < 0.1) are treated as negative examples.

Crystal Structure Text Representation:

- Convert the crystal structure data (lattice parameters, atomic coordinates, space group) into a compact, text-based "material string." This format avoids the redundancy of CIF or POSCAR files and is more suitable for LLM processing [19].

Model Fine-Tuning:

- Select a foundational LLM (e.g., LLaMA).

- Fine-tune the model on the curated dataset of "material strings" labeled as synthesizable or non-synthesizable. This process aligns the model's general linguistic knowledge with the specific domain of crystal synthesizability.

Synthesizability Assessment:

- Input the text representation of a novel candidate structure into the fine-tuned CSLLM.

- The model outputs a classification (synthesizable/non-synthesizable) and/or a probability, providing a rapid and accurate assessment to guide computational discovery efforts.

Protocol: Data Augmentation for Synthesis Condition Prediction

This protocol leverages language models to generate synthetic data, overcoming the scarcity of high-quality, text-mined synthesis recipes [18].

In-Context Learning for Recipe Generation:

- Prompt a state-of-the-art language model (e.g., GPT-4.1, Gemini 2.0 Flash) with a set of example synthesis recipes (target, precursors, temperatures) from a small, trusted dataset.

- The model, leveraging its internal knowledge from pre-training, then generates new, plausible synthesis recipes for a list of target materials.

Data Compilation and Curation:

- Collect the LM-generated recipes to create a large-scale synthetic dataset. For instance, this process can generate over 28,000 complete solid-state synthesis recipes, vastly expanding existing datasets [18].

Model Pretraining and Fine-Tuning:

- Pretrain a specialized model (e.g., a transformer like SyntMTE) on the combination of real text-mined data and the generated synthetic data.

- Subsequently, fine-tune the model on a smaller, high-confidence set of experimentally verified recipes. This hybrid approach has been shown to reduce prediction errors for key parameters like sintering temperature by up to 8.7% compared to models trained only on experimental data [18].

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational and Data Resources for ML-Driven Synthesis Planning

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Synthesis Planning |

|---|---|---|

| Text-Mined Synthesis Database [3] [18] | Dataset | Provides structured data (targets, precursors, operations) from scientific literature to train ML models. |

| Crystal Structure Database (ICSD/MP) [19] [10] | Dataset | Source of confirmed synthesizable structures (ICSD) and theoretical structures (Materials Project) for training synthesizability models. |

| atom2vec / Material Embeddings [10] | Algorithm/Representation | Learns a numerical representation for chemical elements/formulas, capturing patterns from data to inform synthesizability. |

| Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning [19] [10] | Machine Learning Method | Enables training of classifiers using only positive (synthesizable) and unlabeled data, crucial due to the lack of confirmed negative examples. |

| Retro-Rank-In Model [17] | Machine Learning Model | A ranking-based framework for precursor recommendation that generalizes well to novel, unseen target materials. |

| Crystal Synthesis LLM (CSLLM) [19] | Large Language Model | A fine-tuned LLM that predicts synthesizability, suggests synthesis methods, and identifies precursors from crystal structure data. |

| SyntMTE [18] | Machine Learning Model | A transformer model for predicting synthesis conditions (e.g., temperatures), improved by pre-training on LM-generated synthetic data. |

| Language Model (e.g., GPT-4.1) [18] | Large Language Model | Used off-the-shelf for recall of synthesis knowledge or to generate synthetic recipes for data augmentation. |

| Peniditerpenoid A | Peniditerpenoid A, MF:C27H33NO7, MW:483.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Momordicoside X | Momordicoside X, MF:C36H58O9, MW:634.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

How AI Learns Synthesis: From Graph Networks to Large Language Models

Element-Wise Graph Neural Networks for Precursor Set Prediction

The discovery and synthesis of new inorganic materials are fundamental to technological progress in fields such as renewable energy, electronics, and catalysis. While computational models have accelerated the prediction of stable material structures, the determination of viable synthesis pathways and precursor sets remains a significant bottleneck [20]. This document details the application of Element-Wise Graph Neural Networks (Element-Wise GNNs) for predicting inorganic solid-state synthesis recipes, providing a structured framework within the broader context of machine-learning-guided materials research.

Theoretical Foundation: Graph Neural Networks in Materials Science

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are a class of deep learning models designed to operate on graph-structured data, making them exceptionally suited for representing molecules and crystalline materials [21]. In a graph representation, atoms constitute the nodes, and chemical bonds represent the edges. GNNs learn from these structures by performing a message-passing mechanism, where information from neighboring atoms is aggregated and used to update the representation of a target node [21] [22]. This process allows the model to capture complex local chemical environments critical for predicting material properties and, as extended in this work, synthesis pathways.

The Element-Wise Graph Neural Network is a specific architectural variant that has demonstrated high efficacy in predicting inorganic synthesis recipes [20]. Its core innovation lies in its formulation of the precursor prediction problem, treating it as a task of identifying the necessary source elements and their most likely structural arrangements (precursor templates) based on the target material's composition.

Quantitative Performance Data

The performance of the Element-Wise GNN model for precursor prediction can be quantitatively evaluated against baseline methods. The following table summarizes key metrics as reported in the literature [20].

Table 1: Performance comparison of the Element-Wise GNN model for synthesis recipe prediction.

| Model / Metric | Top-K Exact Match Accuracy | Validation Method | Key Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| Element-Wise GNN | Outperforms popularity-based statistical baseline | Publication-year-split test | High correlation between probability score and accuracy, enabling confidence assessment |

| Popularity-Based Baseline | Lower than Element-Wise GNN | Not Specified | Provides a simple statistical benchmark |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing an Element-Wise GNN for Precursor Prediction

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for training and validating an Element-Wise GNN model for precursor set prediction, based on established methodologies [20].

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Data Collection: Compile a database of solid-state synthesis recipes from scientific literature. Each data point should include the target material and its corresponding solid-state precursor compounds.

- Graph Representation: Convert the target material's crystal structure into a graph.

- Nodes: Represent individual atoms. Initialize node features using atomic properties (e.g., element type, atomic radius, electronegativity).

- Edges: Create edges between nodes based on interatomic distances or covalent bonding, typically within a defined cutoff radius.

- Precursor Labeling: Represent the precursor set using a formulation based on source elements and precursor templates. This transforms the problem into a multi-label prediction task.

Model Training Procedure

- Model Architecture: Implement an Element-Wise GNN. The key component is a series of message-passing layers that build element-wise representations by aggregating information from neighboring atoms in the crystal graph.

- Loss Function: Employ a multi-task loss function that jointly optimizes for:

- The correct identification of source elements.

- The correct selection of precursor templates.

- Training Cycle (Active Learning): To enhance performance, an active learning loop can be implemented:

- Train the initial model on the available dataset.

- Use the model to generate predictions on novel candidate materials.

- Validate these predictions using high-fidelity computational methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT).

- Incorporate the successfully validated predictions back into the training data.

- Retrain the model with the expanded dataset. This process has been shown to dramatically boost the model's discovery rate [23].

Model Validation and Testing

- Publication-Year-Split Test: To rigorously evaluate predictive power, train the model on data published up to a certain year (e.g., 2016) and test its ability to predict precursors for materials synthesized after that year. This tests the model's generalizability to novel materials [20].

- Accuracy Assessment: Use metrics such as top-k exact match accuracy to measure how often the model's predicted precursor set exactly matches the experimentally reported one within the top-k recommendations.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end workflow for precursor prediction using an Element-Wise GNN, from data preparation to final prediction.

This section catalogs the key computational tools, datasets, and software required for research in GNN-based synthesis prediction.

Table 2: Essential resources for GNN-driven materials synthesis research.

| Resource Name | Type | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Materials Project Database | Dataset | Provides open-access crystal structures and thermodynamic data for training and benchmarking GNN models [23]. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) Models | Software/Architecture | Core machine learning architecture (e.g., MPNN, GNoME) that processes material graphs to predict properties and synthesis pathways [21] [23]. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) | Computational Tool | Used as a high-fidelity validation method to assess the stability of predicted materials and verify model outputs within an active learning loop [23]. |

| Element-Wise GNN | Software/Architecture | A specific GNN variant designed for retrosynthesis, formulating the problem via source elements and precursor templates [20]. |

| Autonomous/Self-Driving Labs | Experimental System | Robotic laboratories that use AI-predicted recipes (from models like GNoME) to autonomously synthesize new materials, closing the loop between prediction and validation [23]. |

{## Introduction} The synthesis of novel inorganic materials is a cornerstone for technological advances in fields ranging from clean energy to electronics. However, unlike organic synthesis, inorganic solid-state synthesis lacks a general theory that predicts how a target compound forms from precursor materials during heating [24] [25]. Consequently, experimental researchers traditionally approach a new synthesis by manually consulting the scientific literature for precedents involving similar materials and repurposing their recipes—a process limited by individual experience and chemical intuition [24] [26].

Machine learning (ML) is now automating and quantifying this heuristic process. By applying ML to large, text-mined datasets of historical synthesis recipes, researchers can build recommendation systems that learn the complex relationships between a target material's composition and its successful precursor sets [24] [13]. These data-driven systems capture decades of hidden knowledge embedded in the literature, providing powerful tools to guide the synthesis of novel inorganic materials and accelerate their discovery [24] [27].

{## Core Methodologies and Performance} Two advanced ML paradigms demonstrate the power of learning from precedent: a materials-similarity-based approach and an element-wise graph neural network. Their performance can be quantitatively compared across key metrics.

{### Table 1: Comparative Performance of Recommendation Systems}

| Model / Metric | Top-1 Accuracy | Top-5 Accuracy | Core Methodology | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PrecursorSelector (Similarity-Based) [24] | Not Explicitly Reported | 82% (Success Rate) | Learns material vectors from precursors; finds closest reference material. | Mimics human literature search; high success rate for multiple recommendations. |

| ElemwiseRetro (Template-Based) [13] | 78.6% | 96.1% | Formulates retrosynthesis using source elements and precursor templates. | Provides a confidence score for predictions; high top-5 exact match accuracy. |

| Popularity Baseline [13] | 50.4% | 79.2% | Recommends precursors based on their frequency in the dataset. | Serves as a simple statistical benchmark. |

{### Methodology Overview}

The Similarity-Based Approach (PrecursorSelector): This strategy directly automates the human process of looking up similar synthesis recipes [24]. It employs a self-supervised neural network to learn a numerical representation (an encoding) for a target material based on its precursors. In this learned vector space, materials synthesized from similar precursors are positioned close together. To recommend precursors for a novel target, the system identifies the most similar reference material in the knowledge base and adapts its precursor set, achieving an 82% success rate when proposing five precursor sets [24].

The Element-wise Formulation (ElemwiseRetro): This method formulates the problem differently [13]. It first classifies elements in the target material as "source elements" (must be provided by precursors) or "non-source elements" (can come from the environment). A graph neural network then predicts the most probable "precursor template" (e.g., oxide, carbonate) for each source element. The final precursor set is assembled from these predicted templates, and the model outputs a probability score that serves as a valuable confidence level for experimental prioritization [13].

{## Experimental Protocols} {### Protocol 1: Implementing a Similarity-Based Recommendation System}

This protocol outlines the steps for building and deploying a precursor recommendation system based on the PrecursorSelector model [24].

Objective: To recommend precursor sets for a target inorganic material by identifying the most chemically similar material with a known synthesis recipe.

Materials and Data:

- Knowledge Base: A dataset of solid-state synthesis recipes, ideally text-mined from scientific literature. The model in [24] used 29,900 recipes.

- Computing Environment: Standard machine learning stack (e.g., Python, PyTorch/TensorFlow) with sufficient GPU resources for training neural networks.

- Target Material: The chemical formula of the compound to be synthesized.

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Extract and standardize precursor and target material data from the knowledge base. Ensure all chemical formulas are normalized.

- Split the data into training and test sets, ensuring no data leakage between sets.

- Model Training (Materials Encoding):

- Train an encoding neural network using a self-supervised learning task, such as Masked Precursor Completion (MPC). The model learns to predict masked precursors in a set based on the target material and the remaining precursors.

- The model's encoder learns to project the target material's composition into a fixed-dimensional vector where materials with similar precursors are nearby.

- Similarity Query:

- For a novel target material, process its composition through the trained encoder to obtain its vector representation.

- Calculate the similarity (e.g., using cosine similarity) between the target vector and the vectors of all materials in the training knowledge base.

- Identify the reference material with the highest similarity score.

- Precursor Recommendation & Completion:

- Propose the precursor set of the most similar reference material.

- If this set does not contain all elements of the target material, use a conditional prediction model (trained in step 2) to suggest additional precursors to complete the set.

- The system can be configured to recommend k precursor sets (e.g., k=5) by considering the top k most similar reference materials.

- Data Preprocessing:

Validation:

- Perform historical validation by holding out a set of known materials (e.g., 2,654 targets) and treating them as "novel."

- Measure success as the percentage of these test targets for which at least one of the top k recommended precursor sets matches a known successful recipe from the literature [24].

{### Protocol 2: Executing a Template-Based Prediction with ElemwiseRetro}

This protocol details the use of a graph-based, template-driven model for inorganic retrosynthesis [13].

Objective: To predict a ranked list of precursor sets for a target inorganic composition, complete with a confidence score for each prediction.

Materials and Data:

- Training Data: A curated dataset of synthesis recipes with predefined "precursor templates." The model in [13] was trained on 13,477 recipes and uses a library of 60 templates.

- Source Element List: A predefined list classifying which elements (e.g., metals, metalloids) are typically provided as precursors.

- Target Material: The chemical formula of the compound to be synthesized.

Procedure:

- Input Representation:

- Represent the target material as a graph, where nodes represent elements and edges represent their interactions in the composition.

- Apply a source element mask to the graph, highlighting which elements need to be assigned a precursor template.

- Model Inference:

- Process the graph through the pre-trained ElemwiseRetro graph neural network.

- The model performs message-passing to understand the interactions between all elements in the target composition.

- Template Prediction and Ranking:

- For each source element in the masked graph, the model's precursor classifier predicts the most probable precursor template.

- The model calculates the joint probability of the entire set of predicted templates to form a complete precursor set (a "recipe").

- Multiple precursor sets are generated and ranked by their probability scores.

- Input Representation:

Validation:

- Evaluate using top-k exact match accuracy: the proportion of test materials for which the true precursor set appears in the top k recommendations [13].

- Perform a publication-year-split test, training on data up to a certain year (e.g., 2016) and testing on materials synthesized after that date, to validate the model's predictive power for truly novel compounds [13].

{## Visualizing the Workflows} The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and key differences between the two recommendation system paradigms.

{### Diagram title: Precursor Recommendation Workflows}

{## The Scientist's Toolkit} This section details the essential computational and data resources required to develop or utilize precursor recommendation systems.

{### Table 2: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions}

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Research | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Text-Mined Synthesis Database | Dataset | Serves as the foundational knowledge base for training machine learning models. | 29,900 recipes from scientific literature [24]; 13,477 curated recipes for template-based models [13]. |

| Precursor Templates | Data Library | A finite set of anionic frameworks (e.g., oxide, nitrate) used to construct realistic precursor compounds. | A library of 60 templates derived from common commercial precursors [13]. |

| Materials Representation | Algorithm | Converts a chemical formula into a numerical vector (fingerprint) for machine processing. | Magpie, Roost, CrabNet featurization [24]; or a learned representation like PrecursorSelector encoding [24]. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | Model Architecture | Learns complex relationships within a material's composition for accurate template prediction. | ElemwiseRetro model architecture [13]. |

The transition from computationally designed materials to physically realized products is a pivotal challenge in materials science. While high-throughput screening and quantum mechanical calculations can identify millions of candidate materials with promising properties, most remain theoretical constructs due to the critical unsolved problem of synthesizability prediction. Traditional proxies for synthesizability—such as thermodynamic stability (formation energy, energy above convex hull) and kinetic stability (phonon spectra analyses)—exhibit significant limitations, as numerous metastable structures with unfavorable formation energies are successfully synthesized while many thermodynamically stable structures remain elusive [1].

This gap between computational prediction and experimental realization has created an urgent need for more accurate synthesizability assessment tools. Recent advances in large language models (LLMs) have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in learning complex patterns from diverse data types. The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models (CSLLM) framework represents a transformative application of this technology, leveraging specialized LLMs to predict synthesizability, synthetic methods, and suitable precursors for arbitrary 3D crystal structures with unprecedented accuracy [1] [28].

CSLLM Framework Architecture

The CSLLM framework employs a multi-component architecture comprising three specialized LLMs, each fine-tuned for distinct but complementary tasks in the synthesis prediction pipeline.

Model Components and Specializations

- Synthesizability LLM: Predicts whether an arbitrary 3D crystal structure is synthesizable. This model achieves 98.6% accuracy on testing data, significantly outperforming traditional thermodynamic (74.1%) and kinetic (82.2%) stability assessments [1].

- Method LLM: Classifies appropriate synthesis methods (solid-state or solution) for synthesizable structures, achieving 91.0% classification accuracy [1] [28].

- Precursor LLM: Identifies suitable solid-state synthesis precursors for binary and ternary compounds with an 80.2% success rate [1].

Technical Implementation

The framework's exceptional performance stems from two key innovations: a comprehensive dataset and an efficient text representation for crystal structures.

Dataset Construction: The training incorporates 70,120 synthesizable crystal structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) and 80,000 non-synthesizable structures identified from 1,401,562 theoretical structures using a positive-unlabeled (PU) learning model [1]. This balanced dataset covers seven crystal systems and compositions with 1-7 elements, providing robust coverage of inorganic chemical space.

Material String Representation: To enable effective LLM processing, the researchers developed a novel text representation called "material string" that integrates essential crystallographic information in a compact format: SP | a, b, c, α, β, γ | (AS1-WS1[WP1-x,y,z]), ... | SG [1]. This representation includes space group (SP), lattice parameters (a, b, c, α, β, γ), atomic species with Wyckoff positions (AS-WS[WP]), and space group (SG), effectively capturing symmetry relationships while eliminating redundancies present in conventional CIF or POSCAR formats.

The following diagram illustrates the overall CSLLM workflow and architecture:

Performance Benchmarking

Quantitative Assessment

Table 1: Performance comparison of CSLLM against traditional synthesizability assessment methods

| Method | Accuracy (%) | Relative Improvement over Thermodynamic | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSLLM Synthesizability Prediction | 98.6 | 106.1% higher | Requires crystal structure information |

| Thermodynamic Stability (Energy above hull ≥0.1 eV/atom) | 74.1 | Baseline | Misses synthesizable metastable phases |

| Kinetic Stability (Lowest phonon frequency ≥ -0.1 THz) | 82.2 | 44.5% higher | Computationally expensive; imaginary frequencies don't preclude synthesis |

| Charge-Balancing Approaches | ~37 (for known compounds) | N/A | Poor performance even for ionic compounds |

The CSLLM framework demonstrates exceptional generalization capability, achieving 97.9% accuracy on complex structures with large unit cells that considerably exceed the complexity of its training data [1]. This suggests the model has learned fundamental synthesizability principles rather than merely memorizing training examples.

Comparative Analysis with Alternative Approaches

Other machine learning approaches for synthesizability prediction exist, with varying capabilities and limitations:

SynthNN: A deep learning model that predicts synthesizability from chemical composition alone without requiring structural information. While valuable for initial screening, it cannot differentiate between polymorphs or predict synthesis methods and precursors [10].

Retro-Rank-In: A ranking-based framework for inorganic materials synthesis planning that embeds target and precursor materials into a shared latent space. This approach demonstrates improved generalization to novel reactions not seen during training [17].

Text-Mining Approaches: Previous attempts to extract synthesis recipes from scientific literature have faced challenges with data volume, variety, veracity, and velocity, limiting their predictive utility for novel materials [3].

Experimental Protocols

Dataset Preparation Protocol

Materials:

- Experimentally confirmed crystal structures from ICSD

- Theoretical structures from Materials Project, Computational Material Database, Open Quantum Materials Database, and JARVIS

- PU learning model for negative sample identification

Procedure:

- Collect synthesizable structures: Download 70,120 ordered crystal structures with ≤40 atoms and ≤7 elements from ICSD

- Generate non-synthesizable examples:

- Compute CLscore for 1,401,562 theoretical structures using pre-trained PU learning model

- Select 80,000 structures with CLscore <0.1 as non-synthesizable examples

- Validate threshold by confirming 98.3% of positive examples have CLscore >0.1

- Convert to material string representation: Transform all structures to material string format incorporating space group, lattice parameters, Wyckoff positions, and symmetry information

- Split dataset: Partition into training, validation, and testing sets, ensuring no data leakage between splits

Model Training Protocol

Materials:

- Pre-trained foundation LLM (architecture not specified in sources)

- Curated dataset of 150,120 material strings

- Computational resources for fine-tuning large language models

Procedure:

- Model initialization: Start with pre-trained LLM weights

- Architecture specialization: Implement three separate model heads for synthesizability classification, method classification, and precursor generation

- Fine-tuning:

- Employ domain-adaptive fine-tuning on material string dataset

- Use standard language modeling objective with causal masking

- Optimize with cross-entropy loss for classification tasks

- Hyperparameter tuning: Optimize learning rate, batch size, and sequence length via validation set performance

- Validation: Evaluate on held-out test set comprising structures not seen during training

Synthesis Prediction Protocol

Materials:

- Target crystal structure in CIF or POSCAR format

- Trained CSLLM framework

- Computational resources for inference

Procedure:

- Structure conversion: Transform input crystal structure to material string representation

- Synthesizability assessment:

- Input material string to Synthesizability LLM

- Obtain binary classification (synthesizable/non-synthesizable)

- Proceed only if synthesizability probability exceeds decision threshold

- Method classification:

- Input material string to Method LLM

- Receive classification (solid-state or solution synthesis)

- Precursor identification:

- Input material string to Precursor LLM

- Obtain ranked list of potential precursor combinations

- Result interpretation: Integrate predictions to formulate complete synthesis recommendation

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for using CSLLM:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential research reagents and computational resources for CSLLM implementation

| Resource | Type | Function/Role | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICSD Database | Data | Source of synthesizable crystal structures for training | Commercial license |

| Materials Project | Data | Source of theoretical structures for negative examples | Publicly available |

| Material String Representation | Software | Efficient text encoding for crystal structures | Custom implementation |

| Pre-trained Foundation LLM | Software | Starting point for domain-specific fine-tuning | Various open-source options |

| CSLLM Framework | Software | Integrated system for synthesis prediction | GitHub repository available [29] |

| Graphical User Interface | Software | User-friendly interface for structure upload and prediction | Available with framework |

| Isomaltotetraose | Isomaltotetraose, MF:C24H42O21, MW:666.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Chitinovorin B | Chitinovorin B, MF:C30H48N10O12S, MW:772.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Applications and Impact

The CSLLM framework enables high-throughput screening of theoretical materials databases for synthesizable candidates. Researchers have successfully identified 45,632 synthesizable materials from 105,321 theoretical structures, with 23 key properties predicted using graph neural network models to prioritize experimental investigation [1].

This capability dramatically accelerates the materials discovery pipeline by focusing experimental resources on fundamentally synthesizable candidates with desirable properties. The framework's ability to suggest appropriate precursors and synthesis methods further reduces the trial-and-error typically associated with developing synthesis protocols for novel materials.

The development of CSLLM represents a significant milestone in the application of specialized AI systems to overcome persistent bottlenecks in scientific discovery. By demonstrating the effectiveness of LLMs in learning complex materials science concepts, this approach paves the way for similar applications across other scientific domains where empirical knowledge has proven difficult to codify through traditional computational methods.

The discovery and synthesis of novel inorganic materials are pivotal for advancements in technology, from renewable energy systems to next-generation electronics. While computational models can now predict millions of potentially stable compounds, the practical challenge of determining how to synthesize these materials remains a significant bottleneck [1]. Traditional methods rely heavily on trial-and-error experimentation, and emerging machine learning (ML) approaches have often struggled to generalize beyond the reactions and precursors seen in their training data [17]. This application note explores a paradigm shift in this domain: the reformulation of the retrosynthesis problem from a classification task into a ranking-based task. We focus on the innovative Retro-Rank-In framework, which leverages pairwise ranking to dramatically improve out-of-distribution generalization and enable the recommendation of previously unseen precursors, thereby accelerating the development of novel inorganic materials [17] [30].

The Core Innovation: From Classification to Ranking

Traditional ML models for inorganic retrosynthesis have largely treated the problem as a multi-label classification task [30]. In this paradigm, a model learns to predict precursors from a fixed set of classes that were present during training. A significant limitation of this approach is its inability to recommend precursor materials not contained in the training set, severely restricting its utility in discovering new compounds [30].

The Retro-Rank-In framework introduces a fundamental reformulation by defining the problem as a pairwise ranking task [17] [30]. Instead of classifying a target material into predefined precursor categories, the model learns to evaluate and rank candidate precursor sets based on their predicted compatibility with the target.

- Key Mechanistic Difference: The model consists of a composition-level transformer-based materials encoder that generates chemically meaningful representations for both target materials and precursors in a shared latent space. A separate ranker then learns to assess the chemical compatibility between a target and a precursor candidate by evaluating their co-occurrence probability in viable synthetic routes [30].

- Implication for Discovery: This architecture allows a chemist to input any candidate precursor from a vast chemical space during inference. The model can then score and rank these candidates, even if they were completely absent from the training data, a capability critical for exploring novel synthesis pathways [30].

Table 1: Comparison of Retrosynthesis Modeling Approaches

| Feature | Traditional Multi-Label Classification | Ranking-Based Approach (Retro-Rank-In) |

|---|---|---|

| Problem Formulation | Predicts precursors from a fixed set of classes. | Ranks candidate precursor sets based on compatibility with the target. |

| Ability to Propose New Precursors | No; limited to recombining precursors seen in training. | Yes; can score and rank entirely novel precursors. |

| Embedding Space | Precursors and targets often embedded in disjoint spaces. | Embeds both precursors and targets in a shared latent space. |

| Handling Data Imbalance | Can be challenging with many possible precursors and few positive examples. | Allows for custom negative sampling strategies to improve balance and learning. |

| Primary Output | A set of precursor labels. | A ranked list of precursor sets. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflow

The following section outlines the core methodology for implementing and evaluating the Retro-Rank-In framework, providing a protocol for researchers seeking to apply or build upon this approach.

Retro-Rank-In Workflow Protocol

The logical flow of the Retro-Rank-In framework, from data preparation to precursor recommendation, is visualized below.

Title: Retro-Rank-In Experimental Workflow

Protocol Steps:

Input & Data Preparation:

- Input: The process begins with a target material

Twith a defined elemental composition. - Compositional Representation: Represent the target's composition as a vector

x_T = (xâ‚, xâ‚‚, ..., x_d), where eachx_icorresponds to the fraction of elementiin the compound [30]. - Data Pre-processing: Curate a dataset of known synthesis reactions. For rigorous evaluation, split the data to mitigate duplicates and overlaps, ensuring that the test set contains reactions and precursors not seen during training to properly assess generalization [17] [30].

- Input: The process begins with a target material

Model Training & Embedding:

- Materials Encoder: Train a transformer-based encoder on the compositional vectors. This model is responsible for generating chemically meaningful embeddings for both target and precursor materials. Pre-training on large-scale datasets (e.g., for formation enthalpy prediction) can be used to incorporate broad chemical knowledge [30].

- Shared Latent Space: A key objective is to project both target materials and potential precursors into a unified, shared latent space. This alignment is crucial for enabling the comparison of any material with any other, regardless of its original role as a target or precursor [30].

Candidate Generation & Ranking:

- Candidate Selection: For a given target, generate a set of candidate precursor materials

{Pâ‚, Pâ‚‚, ..., Pâ‚™}. This set can be drawn from a vast chemical space and is not limited to the training data [30]. - Pairwise Ranking: The core of the Retro-Rank-In framework. The pairwise ranker takes the embeddings of the target and a candidate precursor and learns to score their chemical compatibility. The training objective is to ensure that verified precursor sets receive a higher score than non-verified or implausible sets [30]. This is akin to methodologies used in other domains, such as the RetroRanker model for organic chemistry, which also uses a pairwise approach to re-rank candidates based on reaction feasibility [31].

- Candidate Selection: For a given target, generate a set of candidate precursor materials

Output & Validation:

- Output: The final output is a ranked list of precursor sets

(Sâ‚, Sâ‚‚, ..., S_K), where the ranking indicates the predicted likelihood of each set successfully forming the target material [30]. - Experimental Validation: The highest-ranked precursors should be validated through controlled solid-state synthesis experiments. The protocol involves mixing precursor powders, heating in a furnace under controlled atmospheric conditions (e.g., inert gas, vacuum), and analyzing the resulting product using techniques like X-ray diffraction (XRD) to confirm the formation of the target phase [1].

- Output: The final output is a ranked list of precursor sets

Key Performance Evaluation

The performance of Retro-Rank-In was rigorously evaluated against prior state-of-the-art models on challenging dataset splits designed to test generalization.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison on Retrosynthesis Tasks

| Model | Generalization Capability | Precursor Discovery | Key Demonstrated Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| ElemwiseRetro [30] | Medium | ✗ | Template completion using domain heuristics. |

| Synthesis Similarity [30] | Low | ✗ | Retrieval of known syntheses of similar materials. |