Kinetic vs. Thermodynamic Control: A Strategic Framework for Optimized Synthesis in Drug Development

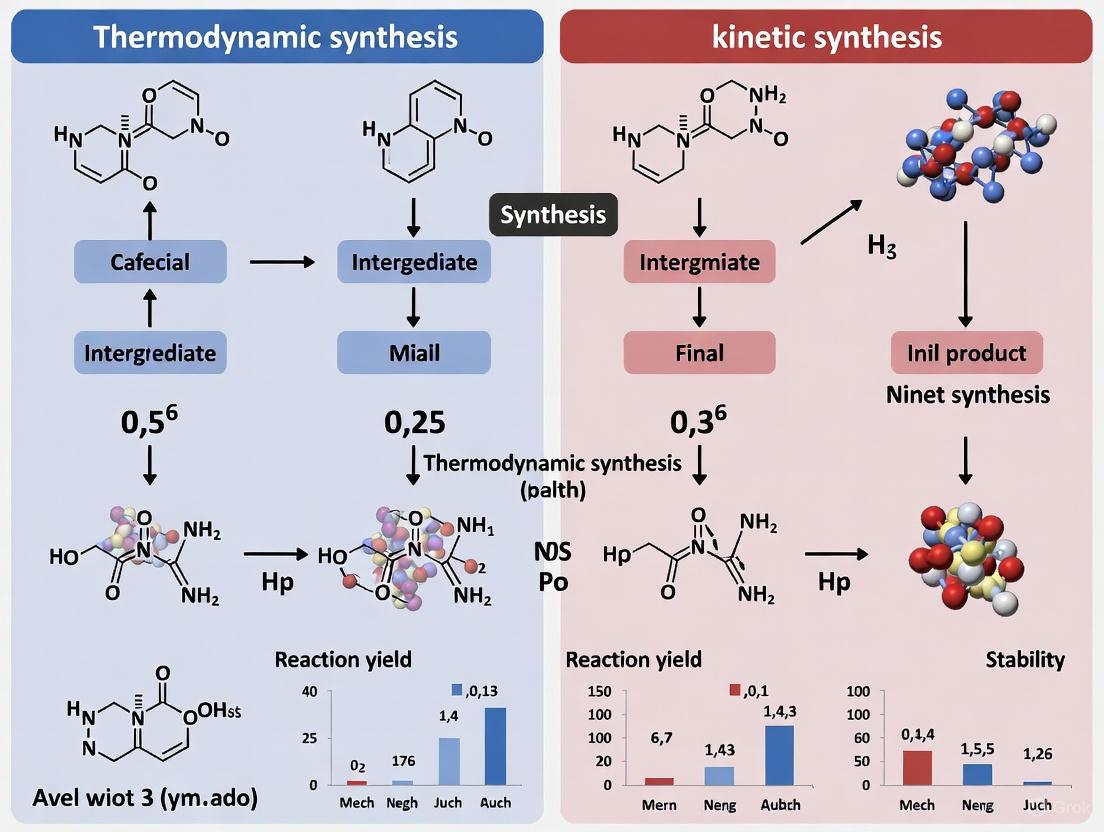

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of thermodynamic and kinetic synthesis approaches, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental principles distinguishing these pathways, using illustrative examples from organic synthesis and nanoscience. The content details advanced methodological applications, including continuous-flow microreactors and computational optimization, highlighting their role in improving efficiency and selectivity. It further offers practical troubleshooting strategies for common challenges and discusses validation through modern Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) frameworks. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with cutting-edge applications, this article serves as a strategic guide for selecting and optimizing synthesis routes to enhance drug development outcomes.

Kinetic vs. Thermodynamic Control: A Strategic Framework for Optimized Synthesis in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of thermodynamic and kinetic synthesis approaches, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental principles distinguishing these pathways, using illustrative examples from organic synthesis and nanoscience. The content details advanced methodological applications, including continuous-flow microreactors and computational optimization, highlighting their role in improving efficiency and selectivity. It further offers practical troubleshooting strategies for common challenges and discusses validation through modern Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) frameworks. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with cutting-edge applications, this article serves as a strategic guide for selecting and optimizing synthesis routes to enhance drug development outcomes.

Core Principles: Demystifying Kinetic and Thermodynamic Control in Chemical Synthesis

In the pursuit of novel compounds, particularly in pharmaceutical development, researchers must navigate complex energy landscapes where reaction pathways bifurcate toward different products. The reaction coordinate diagram serves as an indispensable cartographic tool in this journey, providing a two-dimensional representation of the energy changes that occur as reactants transform into products [1] [2]. On this diagram, the vertical axis represents energy (encompassing free energy, enthalpy, or potential energy), while the horizontal reaction coordinate traces the progression from reactants to products through various transition states and intermediates [3]. For research scientists, these diagrams do more than illustrate abstract concepts—they provide predictive insights into the competition between kinetic and thermodynamic control, a fundamental consideration in synthesizing target molecules with high selectivity and yield [4] [5]. Within the broader thesis comparing thermodynamic and kinetic synthesis approaches, understanding these energy landscapes enables strategic decision-making in reaction design, allowing researchers to manipulate conditions to favor either the fastest-formed or most-stable product.

Decoding the Diagram: Key Features and Terminology

Reaction coordinate diagrams depict the energetic pathway of a reaction, with specific features corresponding to distinct chemical entities and events. Reactants and products appear as horizontal lines or wells whose vertical positions indicate their relative potential energies [3]. The transition state exists as an energy maximum at the peak of each energy barrier, representing a high-energy, transient atomic configuration through which reactants must pass to transform into products [1] [6]. The energy difference between reactants and the transition state constitutes the activation energy (Ea), a kinetic parameter determining the reaction rate according to the Arrhenius equation [6]. For multi-step reactions, reaction intermediates appear as local energy minima between transition states, representing detectable, higher-energy species with finite lifetimes [1].

The overall energy change between reactants and products defines the reaction's thermodynamics. Exothermic reactions release energy (ΔH < 0), with products at lower energy than reactants, while endothermic reactions absorb energy (ΔH > 0), with products at higher energy [3]. In the context of synthetic chemistry, the rate-determining step corresponds to the slowest elementary step with the highest activation barrier [1]. The following Dot language visualization captures these fundamental components and their relationships within a generalized reaction coordinate diagram.

Table 1: Critical Features of Reaction Coordinate Diagrams and Their Chemical Significance

| Diagram Feature | Chemical Correspondence | Research Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Well | Stable species (reactants, products, intermediates) | Determines thermodynamic stability and equilibrium position |

| Energy Peak | Transition state (unstable configuration) | Governs reaction kinetics through activation energy |

| Activation Energy (Ea) | Energy barrier for an elementary step | Dictates reaction rate; target for catalyst design |

| Reaction Intermediate | Transient species with measurable lifetime | Potential for trapping alternative products |

| Overall Energy Change (ΔH) | Thermodynamic driving force | Predicts reaction spontaneity and equilibrium constant |

Kinetic versus Thermodynamic Control: The Fundamental Dichotomy

In synthetic chemistry, particularly pharmaceutical development, many reactions can proceed along competing pathways to yield different products. The dichotomy between kinetic and thermodynamic control governs which product dominates under specific conditions [4]. Kinetic control prevails when the reaction outcome is determined by the relative rates of formation of competing products, favoring the product with the lowest activation energy barrier—the kinetic product [4] [5]. This product forms faster but is typically less stable. In contrast, thermodynamic control dominates when the reaction is reversible and sufficient time allows equilibration to the most stable product—the thermodynamic product—which resides at the global energy minimum, regardless of formation rates [4].

The distinction between these control regimes has profound practical implications. Under kinetic control, the reaction is irreversible or yields are determined before equilibration occurs, making the relative activation energies (ΔEa) the decisive factor [4]. The product ratio follows the relationship: ln([A]t/[B]t) = ln(kA/kB) = -ΔEa/RT, where kA and kB represent the rate constants for formation of products A and B, respectively [4]. Under thermodynamic control, reversibility enables the system to reach equilibrium, favoring the product with the lowest free energy (ΔG°) according to: ln([A]∞/[B]∞) = ln Keq = -ΔG°/RT [4].

Temperature and time serve as crucial experimental handles for manipulating this control. Low temperatures and short reaction times favor kinetic products, as insufficient thermal energy prevents equilibration [4]. Elevated temperatures and extended reaction times favor thermodynamic products by providing the necessary activation energy for reversible steps and sufficient time for equilibration [4]. This paradigm enables synthetic chemists to strategically target different products from the same starting materials through deliberate manipulation of reaction conditions.

Experimental Evidence: Quantitative Data from Model Systems

Electrophilic Addition to Conjugated Dienes

The addition of hydrogen halides to 1,3-butadiene provides a classic experimental demonstration of kinetic versus thermodynamic control, with documented temperature-dependent product distributions [4]. At temperatures below room temperature, the kinetic 1,2-adduct (3-bromo-1-butene) predominates, while the thermodynamic 1,4-adduct (1-bromo-2-butene) dominates at elevated temperatures [4]. This selectivity arises from a resonance-stabilized allylic carbocation intermediate that can be attacked at two different positions [5]. The kinetic 1,2-product forms through a lower-energy transition state with positive charge localized on the more substituted carbon, while the thermodynamic 1,4-product benefits from greater stability due to its disubstituted alkene moiety [5].

Table 2: Experimental Product Distribution in HBr Addition to 1,3-Butadiene

| Temperature Condition | 1,2-Product Yield (%) | 1,4-Product Yield (%) | Dominant Control Regime |

|---|---|---|---|

| Below Room Temperature | Major product | Minor product | Kinetic control |

| Above Room Temperature | Minor product | Major product | Thermodynamic control |

Diels-Alder Cycloadditions

The Diels-Alder reaction between cyclopentadiene and furan demonstrates similar control phenomena, with the less sterically congested endo isomer prevailing as the kinetic product at room temperature, while the more stable exo isomer dominates under thermodynamic control at 81°C with extended reaction times [4]. The exo product achieves greater stability through reduced steric congestion, while orbital interactions in the transition state favor the endo pathway kinetically [4]. A sophisticated 2018 study on tandem inter-/intramolecular Diels-Alder reactions further illustrated this principle, with pincer-[4+2] cycloaddition adducts forming exclusively under kinetic control at low temperatures, while more stable domino-adducts emerged under thermodynamic control at elevated temperatures [4]. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations quantified the activation barriers, revealing a kinetic preference for the pincer pathway (ΔG‡ ≈ 5.7–5.9 kcal/mol) despite the greater thermodynamic stability of domino products (ΔG ≈ 4.2-4.7 kcal/mol) [4].

Experimental Protocols: Probing Kinetic and Thermodynamic Control

Temperature-Dependent Product Distribution Analysis

Purpose: To determine the kinetic and thermodynamic products of a reaction and establish optimal conditions for selective synthesis.

Methodology:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare identical reaction mixtures in temperature-controlled environments (e.g., -78°C, 0°C, 25°C, 60°C, and reflux) under inert atmosphere if necessary.

- Sampling Protocol: For kinetic control assessment, quench aliquots at short time intervals (e.g., 5, 15, 30, 60 minutes). For thermodynamic control, allow reactions to proceed for extended periods (12-72 hours) with monitoring until composition stabilizes.

- Product Analysis: Employ quantitative analytical techniques (GC, HPLC, or NMR spectroscopy) to determine product ratios at each time-temperature combination.

- Data Interpretation: Plot product ratios versus time and temperature. The product dominating at low temperature/short time represents the kinetic product, while the product favored at high temperature/long time represents the thermodynamic product [4].

Determination of Activation Parameters

Purpose: To quantitatively characterize the energy barriers for competing reaction pathways.

Methodology:

- Temperature Variation: Conduct reactions at multiple precisely controlled temperatures.

- Initial Rate Measurement: Determine initial rates of formation for each product at each temperature.

- Arrhenius Analysis: Plot ln(rate) versus 1/T for each product. The slope yields the activation energy (Ea = -R × slope) for each pathway [6].

- Eyring Analysis: Apply the Eyring equation to determine activation free energy (ΔG‡), enthalpy (ΔH‡), and entropy (ΔS‡) from the temperature dependence of rate constants.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Investigating Reaction Control

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature-Controlled Reactor | Precisely manipulates kinetic vs thermodynamic control | Low temperatures (-78°C to 25°C) for kinetic products; elevated temperatures (50-150°C) for thermodynamic products |

| Inert Atmosphere Equipment | Prevents unwanted side reactions | Maintaining anhydrous/anaerobic conditions for sensitive intermediates |

| Analytical Chromatography Systems | Quantifies product distributions | HPLC/GC for kinetic measurements; monitoring equilibration over time |

| Computational Chemistry Software | Models energy surfaces and predicts selectivity | DFT calculations of transition state energies and reaction pathways [4] |

| Sterically-Hindered Strong Bases | Selective formation of kinetic enolates | Generation of less stable but more rapidly formed enolate isomers [4] |

| Phase Diagram Analysis Tools | Identifies minimum thermodynamic competition | Maximizing free energy difference between target and competing phases [7] |

| EGFR-IN-147 | EGFR-IN-147, MF:C13H13N5O, MW:255.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| MU1210 | 5-(1-Methyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-3-(3-(pyridin-4-yl)phenyl)furo[3,2-b]pyridine | High-purity 5-(1-Methyl-1H-pyrazol-4-yl)-3-(3-(pyridin-4-yl)phenyl)furo[3,2-b]pyridine for research use only (RUO). Explore its application in developing kinase inhibitors for oncology. Not for human consumption. |

Strategic Synthesis Applications: Minimizing Kinetic By-Products

The principles of kinetic and thermodynamic control find practical application in minimizing by-products in complex syntheses, particularly in pharmaceutical development where purity is paramount. Recent research has formalized this approach through the Minimum Thermodynamic Competition (MTC) framework, which identifies synthesis conditions that maximize the free energy difference between target and competing phases [7]. This strategy acknowledges that while thermodynamic phase diagrams identify stability regions, they don't explicitly visualize kinetic competition from by-product phases [7]. By maximizing ΔΦ(Y) = Φtarget(Y) - minΦcompeting(Y), where Y represents intensive variables like pH, redox potential, and concentration, researchers can select conditions where the thermodynamic driving force to the target phase significantly exceeds that to competing phases, thereby reducing kinetic by-product formation [7].

Validation of this approach comes from both text-mining of published synthesis recipes and systematic experimental studies. Analysis of 331 aqueous synthesis recipes revealed that literature-reported conditions frequently cluster near MTC-predicted optima [7]. Experimental studies on LiIn(IO3)4 and LiFePO4 synthesis further confirmed that phase-pure products emerged only when thermodynamic competition with undesired phases was minimized, even within the same stability region of a conventional phase diagram [7]. This MTC framework provides a computable, quantitative metric for designing synthesis conditions that harness the interplay between kinetic and thermodynamic factors to optimize selectivity.

Reaction coordinate diagrams provide more than just a visual representation of energy changes—they offer a strategic framework for controlling synthetic outcomes. The competition between kinetic and thermodynamic control represents a fundamental dichotomy that synthetic chemists can exploit through deliberate manipulation of temperature, time, and reaction conditions. The experimental data and protocols outlined herein provide researchers with methodologies to characterize these control regimes systematically, while the Minimum Thermodynamic Competition framework offers a forward-looking approach to designing synthesis conditions that minimize kinetic by-products. For pharmaceutical developers and research scientists, mastering these principles enables rational design of synthetic routes that maximize yield and purity of target molecules, whether they represent the fastest-formed kinetic product or the most stable thermodynamic product.

In synthetic organic chemistry, the competition between kinetic and thermodynamic control governs the outcome of numerous reactions, especially those proceeding through reactive intermediates. This guide objectively compares the two dominant product formation pathways—1,2- and 1,4-addition—in reactions of conjugated dienes. These reactions are foundational in the synthesis of complex molecules, including active pharmaceutical ingredients, where selective control over regioisomers is crucial [8] [9]. The principle hinges on a fundamental dichotomy: whether the reaction conditions favor the most rapidly formed product (kinetic control) or the most stable product (thermodynamic control). Temperature serves as the primary switch between these regimes, providing synthetic chemists with a powerful tool to direct reaction pathways [8] [10]. This analysis provides a detailed comparison, supported by experimental data and protocols, to guide researchers in selecting the appropriate synthetic approach.

Theoretical Framework: Reaction Pathways and Intermediates

Conjugated dienes, such as 1,3-butadiene, undergo electrophilic addition reactions via resonance-stabilized allylic carbocation intermediates. Protonation of a terminal carbon creates a carbocation that is delocalized over two positions (C2 and C4), resulting in a hybrid structure [8] [10].

- 1,2-Addition (Kinetic Pathway): The nucleophile attacks the carbon atom adjacent to the original diene system (C2 of the allylic cation). This product forms faster because the transition state leading to it benefits from better charge stabilization in the secondary carbocation character of the resonance hybrid [8] [11].

- 1,4-Addition (Thermodynamic Pathway): The nucleophile attacks the carbon two atoms away from the original point of protonation (C4). Although this proceeds through a transition state with more primary carbocation character, the final product is more stable, as it typically features a more highly substituted alkene [8] [10].

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for achieving the desired product.

Experimental Comparison: HBr Addition to 1,3-Butadiene

The addition of hydrogen bromide (HBr) to 1,3-butadiene serves as the classic experimental model for demonstrating kinetic versus thermodynamic control [8] [11].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Kinetic Control (1,2-Addition)

- Setup: Purge a three-necked flask equipped with a stir bar, thermometer, and addition funnel with an inert gas (e.g., Nâ‚‚).

- Reaction: Dissolve 1,3-butadiene (e.g., 5.4 g, 0.10 mol) in a suitable solvent (e.g., 100 mL dichloromethane) and cool the mixture to 0°C with an ice bath.

- Addition: Slowly add a solution of HBr (e.g., 8.1 g, 0.10 mol) in the same solvent dropwise with vigorous stirring, maintaining the internal temperature below 5°C.

- Work-up: After the addition is complete and the reaction mixture has been stirred for an additional 30 minutes at 0°C, quench by pouring into a saturated sodium bicarbonate solution.

- Isolation: Extract with dichloromethane, dry the organic layer over anhydrous MgSOâ‚„, filter, and concentrate under reduced pressure to obtain the crude product [8].

Protocol B: Thermodynamic Control (1,4-Addition)

- Setup: Use the same setup as Protocol A.

- Reaction: Dissolve 1,3-butadiene (e.g., 5.4 g, 0.10 mol) in an appropriate high-boiling solvent (e.g., o-xylene) in the flask.

- Addition: Add the HBr solution and heat the mixture to 40-50°C for several hours with stirring.

- Work-up and Isolation: Follow the same work-up and isolation procedure as Protocol A. The product distribution should be analyzed by GC-MS or ¹H NMR to determine the ratio of 1,4- to 1,2-adduct [8] [11].

Quantitative Product Distribution Data

The product distribution for the addition of HBr to 1,3-butadiene is highly dependent on temperature, as shown in the table below.

Table 1: Product Distribution in HBr Addition to 1,3-Butadiene [8]

| Reaction Temperature | 1,2-Adduct Yield (%) | 1,4-Adduct Yield (%) | Dominant Control Regime |

|---|---|---|---|

| -80 °C | >80 | <20 | Kinetic |

| 0 °C | ~70 | ~30 | Kinetic |

| 25 °C (Room Temp.) | ~45 | ~55 | Mixed |

| 40 °C | ~20 | ~80 | Thermodynamic |

Comparative Analysis of Products

Table 2: Characteristics of 1,2- vs. 1,4-Addition Products from 1,3-Butadiene

| Parameter | 1,2-Addition Product (3-Bromo-1-butene) | 1,4-Addition Product (1-Bromo-2-butene) |

|---|---|---|

| IUPAC Name | 3-Bromo-1-butene | (E)-1-Bromo-2-butene |

| Alkene Substitution | Monosubstituted | Disubstituted |

| Stability | Less stable alkene | More stable alkene (Zaitsev rule) |

| Key Intermediate | Resonance-stabilized allylic carbocation | Same resonance-stabilized allylic carbocation |

| Activation Energy Barrier | Lower (faster formation) | Higher (slower formation) |

| Major Control Factor | Reaction rate | Product stability |

Extension to the Diels-Alder Reaction

The concept of kinetic versus thermodynamic control extends beyond electrophilic addition to pericyclic reactions, most notably the Diels-Alder cycloaddition [12].

- Kinetic Control (Endo Product): At lower temperatures, the reaction is irreversible and favors the product formed via the transition state with the lowest activation energy. For Diels-Alder reactions, this is often the endo diastereomer due to stabilizing secondary orbital interactions [12] [13].

- Thermodynamic Control (Exo Product): At higher temperatures, the reaction becomes reversible (via the retro-Diels-Alder pathway). The product distribution then reflects the relative stabilities of the isomers. The exo product is often less sterically hindered and more thermodynamically stable, thus becoming the major product under equilibrium conditions [12].

A striking example is the Diels-Alder reaction of hexafluoro-2-butyne with bis-furyl dienes. At room temperature, the reaction exclusively yields the kinetically controlled "pincer"-adduct. When the same reaction is performed at 140 °C, only the thermodynamically controlled "domino"-adduct is observed, demonstrating nearly perfect control [14] [15].

Table 3: Kinetic vs. Thermodynamic Control in a Model Diels-Alder Reaction [14]

| Condition | Temperature | Major Product | Control Regime | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Room Temp. | Pincer-adduct | Kinetic | Lower activation energy (ΔG‡ lower by 5.7-5.9 kcal/mol) |

| B | 140 °C | Domino-adduct | Thermodynamic | Greater thermodynamic stability (ΔG more stable by 4.2-4.7 kcal/mol) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful experimentation in this field requires specific reagents and an understanding of their roles.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for 1,2-/1,4-Addition Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Example & Note |

|---|---|---|

| 1,3-Butadiene | Model conjugated diene substrate | Typically handled as a gas or cooled liquid. |

| Anhydrous HBr (or HCl) | Strong acid electrophile source | Must be anhydrous to prevent side reactions; can be generated in situ. |

| Polar Aprotic Solvents | Reaction medium for electrophilic addition | e.g., Dichloromethane (DCM), used for HBr addition at low temps [14]. |

| Aromatic Solvents | High-boiling reaction medium | e.g., Toluene, o-Xylene; used for high-temperature thermodynamic control studies [14]. |

| Cyclopentadiene | Highly reactive diene for Diels-Alder | Must be freshly cracked from its dimer dicyclopentadiene before use [12]. |

| Hexafluoro-2-butyne | Extremely reactive dienophile | A gas; allows for clean kinetic control at low temperatures in Diels-Alder reactions [14] [15]. |

| Lewis Acids | Catalysts for Diels-Alder reactions | e.g., Etâ‚‚AlCl; lower reaction activation energy, can influence endo/exo selectivity [16]. |

| Boc-LRR-AMC | Boc-LRR-AMC, MF:C33H52N10O7, MW:700.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Antibiotic PF 1052 | Antibiotic PF 1052, MF:C26H39NO4, MW:429.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The competition between 1,2- and 1,4-addition provides a fundamental and powerful paradigm for controlling synthetic outcomes. As demonstrated, temperature is the primary variable for switching between kinetic and thermodynamic products in reactions of dienes. The experimental data clearly show that low temperatures and irreversible conditions favor the 1,2-adduct (kinetic product), while elevated temperatures and reversible conditions shift selectivity toward the more stable 1,4-adduct (thermodynamic product). This principle, first established in simple electrophilic additions, proves to be broadly applicable, governing diastereoselectivity in sophisticated Diels-Alder cycloadditions relevant to materials science and natural product synthesis [8] [14]. For researchers in drug development, mastering this control is indispensable for the selective synthesis of target regio- and stereoisomers, ultimately enabling the precise construction of complex molecular architectures.

The Role of Temperature and Reversibility in Determining Reaction Pathway

In the design of synthetic routes for pharmaceutical development, two fundamental paradigms exist: thermodynamic control and kinetic control. The choice between these pathways profoundly influences the yield, selectivity, and scalability of target molecules, with temperature and reaction reversibility serving as critical levers. Thermodynamic control results in the most stable product, typically favored under conditions that allow for reaction reversibility and extended reaction times to reach equilibrium. In contrast, kinetic control yields the product formed via the fastest pathway, often the one with the lowest activation energy, and is favored under irreversible conditions or when the reaction is quenched before equilibrium is established [17]. This guide provides a structured comparison of these approaches, equipping researchers with the data and protocols necessary to strategically steer reaction outcomes in complex syntheses.

Theoretical Foundations: Reaction Pathways, Temperature, and Reversibility

Reaction Pathway Diagrams and Energetics

A reaction pathway diagram, also known as an energy profile diagram, visualizes the energy changes during a chemical reaction, plotting the energy of the system from reactants through to products [17].

- Activation Energy (

E_a): The minimum energy required for reactant molecules to undergo a successful collision and initiate the reaction. It is represented as the energy difference between the reactants and the highest transition state [17]. - Enthalpy Change (

ΔH): The overall energy difference between reactants and products, indicating whether a reaction is exothermic (ΔH < 0) or endothermic (ΔH > 0) [17]. - Transition State: A high-energy, unstable intermediate stage during which chemical bonds are partially broken and formed. It cannot be isolated and corresponds to the peaks in the reaction pathway diagram [17].

The following diagram illustrates these concepts for generic exothermic and endothermic reactions.

The Critical Role of Temperature

Temperature is not merely a rate accelerator; it is a fundamental parameter that can shift the limiting factor of a reaction. A meta-analysis of enzyme-catalyzed reactions revealed that the activation energy for product formation is approximately twice that for diffusion or transport (E_Z > E_D). This difference means that as temperature increases, the rate of product formation accelerates more rapidly than the rate at which substrates can diffuse to the active site or products can diffuse away [18]. Consequently, a reaction can shift from being rate-limited by catalysis at lower temperatures to being diffusion-limited at intermediate temperatures, and finally to being entropy production-limited at higher temperatures, where product dissipation is insufficient, leading to a decline in net rate and the observation of an optimal temperature (T_opt) [18]. This T_opt can be significantly lower than the enzyme denaturation temperature and is influenced by enzyme concentration and efficiency, patterns consistent with reaction-diffusion thermodynamics rather than just enzyme state changes [18].

Reversibility in Thermodynamic and Kinetic Contexts

A reversible process in thermodynamics is an idealized, quasistatic process where the system and its surroundings can be restored to their exact original states by an infinitesimal reversal of the process conditions. Such a process occurs infinitely slowly through a continuous series of equilibrium states, with no energy dissipated as friction or waste heat [19] [20]. In contrast, an irreversible process is a natural, finite-time process where the system and surroundings cannot be simultaneously returned to their initial states. These processes, characterized by finite gradients (e.g., in temperature or pressure) and dissipative effects, define the maximum theoretical efficiency for real processes [19] [20] [21].

Table 1: Characteristics of Reversible and Irreversible Processes

| Feature | Reversible Process | Irreversible Process |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Process direction can be reversed by infinitesimal changes in surroundings [19]. | System and surroundings cannot be restored to original states [21]. |

| Nature | Idealized, quasistatic [20]. | Natural, spontaneous [20]. |

| Rate | Infinitely slow [19]. | Finite, measurable rate. |

| Dissipation | No energy lost to friction or other dissipative effects [19]. | Involves dissipative effects like friction, unrestrained expansion, or heat transfer through a finite temperature difference [20] [21]. |

| Practical Example | Slow isothermal compression/expansion of gases; frictionless motion [21]. | Relative motion with friction; heat transfer; diffusion; burning of fuel [21]. |

In synthetic chemistry, these concepts translate directly. A thermodynamically controlled reaction operates under conditions that allow for reversibility, enabling the system to sample multiple pathways and ultimately populate the most stable product (global energy minimum). A kinetically controlled reaction is pushed down a specific, irreversible pathway, often via the use of highly reactive reagents or specific catalysts, to form the product with the lowest activation energy (kinetic product) faster than the thermodynamic product can form.

Comparative Analysis: Thermodynamic vs. Kinetic Synthesis

Objective Comparison and Experimental Data

The following table synthesizes core experimental distinctions between the two synthesis approaches, providing a basis for informed strategic choices.

Table 2: Comparative Guide to Thermodynamic vs. Kinetic Synthesis

| Parameter | Thermodynamic Control | Kinetic Control |

|---|---|---|

| Governing Principle | Global minimization of free energy (ΔG) [19]. | Minimization of activation energy (E_a) [17]. |

| Key Determinant | Stability of the final product. | Rate of the product-forming step. |

| Reaction Reversibility | Essential; reactions must be reversible to reach equilibrium [19] [20]. | Not required; often exploits irreversible steps. |

| Typical Temperature | Higher temperatures to overcome kinetic barriers and reach equilibrium faster [18]. | Lower temperatures to suppress unwanted side reactions and avoid thermodynamic product formation. |

| Reaction Time | Long, to ensure equilibrium is established. | Short, to prevent equilibration and isolate the kinetic product. |

| Primary Outcome | Most stable product (global energy minimum). | Fastest-formed product (kinetic product). |

| Product Selectivity | Controlled by relative stability of products. | Controlled by relative activation energies of pathways [17]. |

| Yield Limitation | Equilibrium constant (K_eq). | Relative rates of parallel reactions. |

| Characteristic Data | Linear Arrhenius plot for rate constant (k) at low T, potential for rate decline at high T due to entropy production limits [18]. | Linear Arrhenius plot for rate constant (k); E_a is the decisive parameter [17]. |

Experimental Protocols for Pathway Differentiation

The following workflows provide a framework for empirically determining whether a reaction is under thermodynamic or kinetic control.

Protocol 1: Temperature Dependence Study

- Reaction Setup: Perform the identical reaction across a temperature gradient (e.g., 0°C, 25°C, 60°C, 100°C) while keeping all other parameters (concentration, solvent, catalyst) constant.

- Product Monitoring: Use an analytical technique (e.g., HPLC, GC) to monitor product distribution and yield over time at each temperature.

- Data Interpretation:

- Kinetic Indicator: A product that dominates at lower temperatures but diminishes in yield as temperature increases is likely the kinetic product.

- Thermodynamic Indicator: A product whose yield increases with temperature and/or prolonged reaction time, eventually becoming dominant, is likely the thermodynamic product [18].

Protocol 2: Reaction Reversibility and Equilibration Study

- Initial Synthesis: Synthesize the suspected kinetic product in isolation.

- Equilibration Conditions: Subject the purified kinetic product to the original reaction conditions (same solvent, temperature, and potential catalyst).

- Product Analysis: Monitor the reaction mixture over an extended time.

- Data Interpretation:

- Kinetic Control Confirmation: If the kinetic product remains unchanged, the reaction is effectively irreversible and under kinetic control.

- Thermodynamic Control Confirmation: If the kinetic product converts into a different, more stable product, the reaction is reversible and under thermodynamic control, with the new product being the thermodynamic product [19] [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The choice of reagents and catalysts is paramount in directing a reaction down a desired pathway. The following table details key solutions used in these strategic approaches.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Pathway Control

| Reagent/Material | Function in Synthesis | Role in Pathway Control |

|---|---|---|

| Lewis Acids (e.g., AlCl₃, BF₃) | Electrophilic catalyst; activates substrates toward nucleophilic attack. | Kinetic Control: Can be chosen for steric bulk to favor less hindered transition states, or to activate a specific functional group irreversibly. |

| Organometallic Catalysts (e.g., Pd(PPh₃)₄, Grubbs' Catalyst) | Facilitates cross-coupling, metathesis, and other transformations. | Kinetic Control: Often operates through irreversible insertion or metathesis steps. Thermodynamic Control: Some equilibration can occur in metathesis, favoring stable isomers. |

| Acid/Base Catalysts | Promotes reactions like aldol condensation, esterification, hydrolysis. | Thermodynamic Control: Protic acids/bases often catalyze reversible reactions, allowing for equilibration to the most stable product (e.g., in acetal formation). |

| Selective Reducing Agents (e.g., DIBAL-H, NaBHâ‚„) | Reduces specific functional groups with high chemoselectivity. | Kinetic Control: Reduces the most reactive carbonyl (e.g., acyl chloride vs. ester) fastest, allowing isolation of a kinetic intermediate (e.g., an aldehyde from an ester). |

| Selective Oxidizing Agents (e.g., PCC, Dess-Martin periodinane) | Oxidizes alcohols to carbonyls with defined selectivity. | Kinetic Control: Oxidizes the most accessible alcohol (e.g., primary over secondary) without over-oxidation, isolating the kinetic aldehyde product. |

| Solid Supports & Immobilized Reagents | Provides a heterogeneous phase for reaction, simplifying work-up and enabling continuous flow. | Can influence both pathways by controlling local concentration and diffusion rates, potentially shifting the T_opt by introducing transport limitations [18]. |

| AZA1 | AZA1, MF:C22H20N6, MW:368.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| HSL-IN-5 | HSL-IN-5, MF:C18H23F3N2O4, MW:388.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The strategic decision between thermodynamic and kinetic control is a cornerstone of efficient synthetic design, particularly in pharmaceutical development where selectivity and yield are paramount. Temperature is a powerful tool that not only accelerates reactions but can also fundamentally shift the limiting step of a process, while an understanding of reversibility defines the very nature of the reaction landscape. By applying the comparative data, experimental protocols, and reagent strategies outlined in this guide, researchers can make informed decisions to deliberately steer reactions toward the desired product, optimizing both the efficiency and outcome of their synthetic endeavors.

The pursuit of precision in nanomaterial fabrication has led researchers to embrace two fundamental philosophical approaches: thermodynamic control and kinetic control. These frameworks govern the assembly of atoms and molecules into nanostructures with defined size, shape, and composition, ultimately determining their properties and application potential. While thermodynamic strategies aim for the most stable configuration through equilibrium processes, kinetic approaches leverage energy input to trap intermediates and metastable structures that would otherwise be inaccessible. This guide provides an objective comparison of these competing paradigms, examining their underlying principles, experimental implementations, and resulting nanomaterial characteristics to inform research strategies across scientific disciplines, particularly in pharmaceutical development where nanomaterial properties directly impact therapeutic efficacy.

Theoretical Foundations: Thermodynamic vs. Kinetic Control

The divergence between thermodynamic and kinetic control originates from their distinct relationships with reaction pathways and energy landscapes. Thermodynamic control operates under conditions where reactions proceed at or near equilibrium, allowing the system to sample multiple pathways before settling into the global free energy minimum. This approach typically yields the most stable and chemically robust structures, often characterized by high crystallinity and predictable morphologies. In contrast, kinetic control dominates when reactions are driven far from equilibrium through rapid energy input or reactant addition, trapping intermediates in local energy minima before they can reach the thermodynamically favored state [22] [23].

The conceptual distinction can be visualized through the following energy landscape diagram:

This fundamental theoretical distinction manifests in practical synthesis outcomes. Thermodynamically controlled processes typically produce materials with higher order and crystallinity, while kinetically controlled methods enable access to metastable phases, amorphous structures, and non-equilibrium morphologies that expand the repertoire of available nanomaterials for specialized applications [22] [24].

Synthesis Methodologies: Experimental Frameworks

Thermodynamically-Driven Approaches

Thermodynamic control in nanomaterial synthesis emphasizes equilibrium conditions, allowing systems to reach their lowest energy state through self-assembly or slow, controlled growth. These methods typically employ moderate temperatures and extended timeframes to enable atomic rearrangement and defect minimization.

Sol-Gel Synthesis represents a classic thermodynamic approach exemplified by magnesium silicate nanoparticle fabrication [25]. The detailed protocol involves:

- Hydrolysis: Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) undergoes hydrolysis in a mixture of 250 mL distilled water and 50 mL ethanol with stirring for 2 hours at 80°C

- Precursor Addition: Introduction of 1 mol MgClâ‚‚ solution with continued stirring for 30 minutes under identical conditions

- pH Adjustment: Adjustment to pH 10 using NHâ‚„OH to facilitate condensation reactions

- Aging: Solution remains undisturbed for 24 hours to form a viscous gel through spontaneous self-assembly

- Processing: Filtration followed by drying and calcination at 800°C to yield crystalline nanoparticles [25]

Self-Assembly Methods represent another thermodynamic approach where molecular building blocks spontaneously organize into ordered nanostructures driven by non-covalent interactions including hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic effects, and π-π stacking [26]. This methodology is particularly valuable for creating drug delivery systems where amphiphilic drugs autonomously form nanostructures like micelles, rods, or liposomes without external energy input [26].

Kinetically-Driven Approaches

Kinetic control utilizes rapid energy input or precise reagent mixing to create non-equilibrium conditions that trap intermediate structures. These methods offer superior control over size distribution and enable the formation of metastable phases.

Microfluidic-Assisted Synthesis exemplifies kinetic control through precise fluid manipulation at micron dimensions. The experimental workflow encompasses:

- Chip Design: Fabrication of microchannels (typically 50-500 μm) using soft lithography or glass etching

- Flow Configuration: Implementation of either active (external energy) or passive (hydrodynamic focusing) mixing strategies

- Rapid Mixing: Precise control of reagent streams achieving mixing timescales of milliseconds

- Residence Time Control: Adjustment of channel length and flow rates to control reaction time before quenching

- Collection: Output of nanoparticles with narrow size distributions [27]

Chemical Reduction Methods represent another kinetic approach where rapid reduction of metal precursors occurs in the presence of stabilizing agents. Key parameters include:

- Precursor concentration (0.1-100 mM)

- Reducing agent selection (sodium borohydride for strong reduction, citrate for milder reduction)

- Stabilizer choice (polymers, surfactants, or ligands) to prevent aggregation

- Temperature control (0-100°C) to regulate reduction kinetics [28]

Comparative Analysis: Process Parameters and Material Outcomes

The distinction between thermodynamic and kinetic approaches manifests clearly in their operational parameters and the resulting nanomaterial characteristics. The following tables provide a systematic comparison of both frameworks.

Table 1: Synthesis Condition Comparison Between Thermodynamic and Kinetic Approaches

| Parameter | Thermodynamic Control | Kinetic Control |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Input | Moderate | High |

| Time Scale | Hours to days | Milliseconds to minutes |

| Temperature | Moderate to high (enables equilibrium) | Variable (often room temperature to low) |

| Reaction State | Near or at equilibrium | Far from equilibrium |

| Key Controlling Factors | Temperature, concentration, stability | Mixing rate, energy input, precursor concentration |

| Process Scalability | Generally easily scalable | Requires engineering for scalability [27] |

| Representative Methods | Sol-gel, self-assembly, hydrothermal | Microfluidic, chemical reduction, laser ablation [22] [23] |

Table 2: Nanomaterial Characteristics Resulting from Different Control Mechanisms

| Property | Thermodynamic Control | Kinetic Control |

|---|---|---|

| Crystallinity | Typically high | Variable (often amorphous or defective) |

| Size Distribution | Broader | Narrower |

| Morphology | Predictable, equilibrium shapes | Diverse, non-equilibrium shapes |

| Structural Defects | Minimal | Can be engineered |

| Reproducibility | High | Moderate to high with precise control |

| Metastable Phases | Rare | Common |

| Surface Chemistry | Well-defined | Tunable through capping agents [22] [23] [27] |

The relationship between synthesis parameters and final nanoparticle properties follows a deterministic pathway that can be visualized as:

Application-Specific Performance Evaluation

Drug Delivery Systems

In pharmaceutical applications, the choice between thermodynamic and kinetic control significantly impacts nanoparticle performance metrics including drug loading capacity, release kinetics, and targeting efficiency.

Size-Dependent Performance: Experimental data reveals that nanoparticle size directly influences cellular uptake efficiency. Studies using Caco-2 cell lines demonstrate that 100 nm nanoparticles exhibit 2-3-fold higher drug uptake compared to 1 μm particles and a 6-fold increase over 10 μm particles [27]. Kinetically controlled methods like microfluidics excel at producing these optimal sub-100 nm particles with narrow size distributions.

Stability Considerations: Thermodynamically synthesized nanoparticles typically demonstrate superior long-term stability against aggregation—a critical factor for pharmaceutical shelf life. However, kinetically produced nanoparticles can be engineered with specific surface properties to enhance stability through appropriate stabilizer selection [28] [27].

Energy Storage Materials

Nanomaterial synthesis approach significantly influences performance in energy storage applications, particularly for phase change materials (PCMs) used in thermal energy storage.

Thermal Stability Enhancement: Experimental studies on D-mannitol/GNP (graphene nanoplatelet) composites demonstrate that nano-enhanced PCMs exhibit significantly improved thermal stability. Model-free kinetic analysis reveals activation energies (Eâ‚) ranging from 123.67 to 149.08 kJ·molâ»Â¹ for composites containing 0.25-1 wt% GNP, substantially higher than pure D-mannitol (61.99-141.48 kJ·molâ»Â¹ depending on calculation method) [29].

Prediction Modeling: Machine learning approaches, particularly random forest regression, have achieved high predictive accuracy (R² = 0.99) for forecasting thermal stability of nano-enhanced PCMs, enabling computational design of thermally stable energy storage materials [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of thermodynamic or kinetic synthesis approaches requires specific material systems. The following table outlines key research reagents and their functions in nanomaterial fabrication.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Nanomaterial Synthesis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Compatible Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal Precursors | MgCl₂·6H₂O, TEOS, metal salts (AgNO₃, HAuCl₄) | Source of metallic or ceramic component | Both |

| Reducing Agents | Sodium borohydride, citrate, plant extracts | Electron donors for nanoparticle formation | Primarily kinetic |

| Stabilizers/Capping Agents | Polymers, surfactants, thiol ligands | Control growth and prevent aggregation | Both (selection differs) |

| Solvents | Water, ethanol, organic solvents | Reaction medium | Both |

| Structure-Directing Agents | Block copolymers, surfactants | Template nanoscale architecture | Primarily thermodynamic |

| Biological Molecules | Enzymes, microorganisms, plant extracts | Green synthesis catalysts | Primarily thermodynamic [25] [28] [30] |

| Transketolase-IN-4 | 5-Benzyl-3-(4-chlorophenyl)pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-7(4H)-one | Explore 5-Benzyl-3-(4-chlorophenyl)pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-7(4H)-one (CAS 419547-73-2), a high-purity research compound for antitubercular and kinase inhibition studies. For Research Use Only. | Bench Chemicals |

| PDE5-IN-9 | 2-(Pyridin-3-yl)-N-(thiophen-2-ylmethyl)quinazolin-4-amine, 98% | High-purity 2-(Pyridin-3-yl)-N-(thiophen-2-ylmethyl)quinazolin-4-amine for cancer research. CAS 157862-84-5. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

The comparative analysis of thermodynamic versus kinetic control frameworks reveals complementary rather than competing paradigms in nanomaterial fabrication. Thermodynamic approaches offer distinct advantages for applications requiring high stability, crystallinity, and predictable morphology, while kinetic strategies provide superior control over size distribution, access to metastable phases, and non-equilibrium structures. The strategic selection between these approaches should be guided by application requirements rather than methodological preference, with emerging hybrid methods offering the most versatile toolkit for advanced nanomaterial design. As the field progresses toward increasingly sophisticated nanomaterials, the intentional application of these fundamental control mechanisms will enable researchers to precisely engineer materials with tailored properties for specific pharmaceutical, energy, and biomedical applications.

Advanced Strategies and Real-World Applications in Pharmaceutical Synthesis

Harnessing Kinetic Control for Rapid Access to Complex Intermediates

In synthetic chemistry, the competition between kinetic and thermodynamic control is a fundamental concept that dictates the outcome of reactions with competing pathways. Kinetic control describes reaction conditions that favor the fastest-forming product, which is not necessarily the most stable. In contrast, thermodynamic control describes conditions that allow the reaction to reach equilibrium, favoring the most stable product [4]. For researchers seeking rapid access to complex intermediates, particularly in drug development where these intermediates may be unstable or highly reactive, harnessing kinetic control provides a powerful strategic approach.

The distinction between these pathways has profound implications for synthetic efficiency. Kinetic products form faster because they have a lower activation energy barrier, while thermodynamic products are more stable and possess a lower overall free energy [31] [4]. Under kinetic control, the relative product ratio is determined by the difference in activation energies, whereas under thermodynamic control, it depends on the difference in free energy between the products [4].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Kinetic vs. Thermodynamic Control

| Feature | Kinetic Control | Thermodynamic Control |

|---|---|---|

| Governing Factor | Reaction rate (activation energy) | Product stability (free energy) |

| Product Type | Kinetic (fastest-forming) | Thermodynamic (most stable) |

| Reaction Conditions | Lower temperatures, shorter times, irreversible | Higher temperatures, longer times, reversible |

| Key Influence | Fastest pathway | Most stable outcome |

| Equilibration | Negligible during reaction time | Reaches equilibrium |

Experimental Data and Comparative Performance

The choice between kinetic and thermodynamic control significantly influences the composition of reaction mixtures. Experimental data from diverse chemical systems demonstrates how reaction parameters can be manipulated to steer selectivity.

Performance in Model Chemical Reactions

Several classic organic reactions provide clear experimental evidence of how kinetic and thermodynamic control yield different products.

Diels-Alder Reactions: In the cycloaddition of cyclopentadiene with furan, the less stable endo isomer is the main product at room temperature under kinetic control. However, at elevated temperatures (81 °C) and with longer reaction times, the system reaches equilibrium and produces the more stable exo isomer as the thermodynamic product [4]. The exo product gains stability from lower steric congestion, while the endo product is favored kinetically by superior orbital overlap in the transition state.

Electrophilic Additions: The addition of hydrogen bromide to 1,3-butadiene shows temperature-dependent selectivity. At lower temperatures (below room temperature), the kinetic 1,2-adduct (3-bromo-1-butene) predominates. At higher temperatures, the reaction favors the thermodynamic 1,4-adduct (1-bromo-2-butene), which benefits from having the larger bromine atom at a less congested site and containing a more highly substituted alkene [4].

Enolate Chemistry: The deprotonation of unsymmetrical ketones demonstrates the strategic importance of control. The kinetic product is the enolate resulting from removal of the most accessible α-hydrogen, while the thermodynamic product features the more highly substituted enolate. Using low temperatures and sterically demanding bases enhances kinetic selectivity [4].

Table 2: Experimental Comparison of Kinetic and Thermodynamic Products

| Reaction System | Kinetic Product | Thermodynamic Product | Conditions Favoring Kinetic Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diels-Alder (Cyclopentadiene + Furan) | Endo isomer | Exo isomer | Room temperature |

| Electrophilic Addition (HBr + 1,3-Butadiene) | 3-Bromo-1-butene (1,2-adduct) | 1-Bromo-2-butene (1,4-adduct) | Below room temperature |

| Enolate Formation (Unsymmetrical Ketone) | Less substituted enolate | More substituted enolate | Low temperature, sterically hindered base |

Performance in Dynamic Covalent Chemistry and Complex Systems

In dynamic covalent chemistry (DCC), the competition between kinetic and thermodynamic control enables the synthesis of complex architectures. DCC utilizes reversible covalent bonds, combining error correction with the stability of covalent final products [32].

Studies have demonstrated that systems under thermodynamic control can effectively error-correct, steering even off-pathway intermediates toward favorable product distributions. However, when reversible bonds have slow exchange rates, systems become susceptible to kinetic trapping. This phenomenon can be harnessed to isolate metastable structures that would not be accessible at equilibrium [32]. For instance, research on alkyne metathesis has shown that specific reaction conditions can lead to kinetically trapped tetrahedral cages rather than the thermodynamically favored structures [32].

In biochemical contexts, such as SNARE-mediated synaptic vesicle fusion, kinetic control governs rapid biological processes. Single-molecule studies have revealed that regulatory proteins like synaptotagmin 1 and NSF create and dissolve kinetic intermediates (fusion pores) on micro- to millisecond timescales, a process crucial for neurotransmission [33].

Experimental Protocols for Harnessing Kinetic Control

General Principles for Experimental Design

To successfully harness kinetic control, researchers should implement several key strategies. First, lower reaction temperatures are critical for favoring the kinetic pathway, as temperature appears in the denominator of the equation relating product ratio to activation energy difference [4]. Second, shorter reaction times prevent equilibration and isolate the kinetic product. Third, the use of irreversible conditions or rapid quenching mechanisms prevents the kinetic product from converting to the thermodynamic product. Finally, sterically hindered reagents can influence selectivity, as demonstrated in enolate formation with bulky bases [4].

Detailed Protocol: Kinetic Protonation of Enolates

This protocol describes the kinetic protonation of an enolate to yield the enol, a classic example of kinetic control [4].

Enolate Formation: Cool the unsymmetrical ketone (e.g., 2-methylcyclohexanone) in an anhydrous aprotic solvent (e.g., THF) to -78°C under inert atmosphere. Add a strong, sterically hindered base (e.g., LDA) dropwise with stirring. Maintain the temperature at -78°C for 30 minutes to ensure complete enolate formation.

Kinetic Protonation: Rapidly add a stoichiometric amount of a proton source (e.g., acetic acid) pre-cooled to -78°C. The quenching must be fast to avoid equilibration.

Workup and Analysis: Immediately transfer the reaction mixture to a cold aqueous workup solution. Extract the organic layer and analyze the product mixture using NMR or GC-MS to determine the ratio of isomeric products, confirming the dominance of the kinetic enol.

Detailed Protocol: Low-Temperature Diels-Alder Reaction

This protocol favors the kinetic endo adduct in the Diels-Alder reaction between cyclopentadiene and furan [4].

Reaction Setup: Dissolve furan in an appropriate solvent (e.g., dichloromethane) and cool the solution to 0°C (not room temperature) in an ice bath.

Addition: Slowly add a slight stoichiometric excess of freshly cracked cyclopentadiene to the cooled furan solution with vigorous stirring.

Kinetic Control Phase: Maintain the reaction at 0°C and monitor by TLC or GC. The reaction typically shows significant conversion to the endo adduct within several hours.

Product Isolation: Once a target conversion is reached, immediately concentrate the reaction mixture under reduced pressure at low temperature to isolate the kinetic endo product before significant equilibration can occur.

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core concepts of kinetic and thermodynamic control and a generalized experimental workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successfully implementing kinetic control strategies requires specific reagents and materials designed to favor kinetic pathways and trap transient intermediates.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Kinetic Control Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function in Kinetic Control | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Sterically Hindered Bases (e.g., LDA) | Selective deprotonation at less hindered sites to form kinetic enolates | Regioselective enolate formation [4] |

| Aprotic Anhydrous Solvents (e.g., THF, DMF) | Prevent proton transfer and solvation that promote equilibration | Maintaining enolate integrity, Diels-Alder reactions |

| Cryogenic Equipment | Enable low-temperature conditions to suppress equilibration | All kinetic control protocols [4] |

| Rapid Quenching Solutions | Trap kinetic intermediates irreversibly | Protonation of enolates to enols [4] |

| Analytical Monitoring Tools (GC-MS, NMR, TLC) | Track reaction progression in real-time to identify optimal quenching time | All kinetic control experiments [4] |

| Nanodisc-BLM Systems | Study kinetic intermediates in membrane fusion processes | SNARE-mediated fusion pore formation [33] |

| Flaviviruses-IN-2 | Flaviviruses-IN-2, MF:C21H20N2O3S, MW:380.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Glomeratose A | Glomeratose A, MF:C24H34O15, MW:562.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The strategic choice between kinetic and thermodynamic control is a fundamental principle in synthetic chemistry that enables selective formation of different products from the same starting materials. This case study examines a specific application of this principle: the temperature-dependent metalation of a hexadentate ligand for the selective synthesis of both mono- and trinuclear isostructural clusters [34]. This approach demonstrates how precise control over reaction parameters can dictate nuclearity and metal composition in cluster compounds, with significant implications for materials science and drug development where specific cluster architectures are required for desired properties or activities.

Theoretical Framework: Kinetic vs. Thermodynamic Control

Fundamental Principles

In chemical synthesis, the reaction pathway and final products are influenced by two competing factors: the stability of products (thermodynamics) and the rate of product formation (kinetics) [35].

Kinetic Control: Favors the product that forms fastest, characterized by the lowest activation energy barrier [35]. This product may not be the most stable but is the most accessible in the short term. Kinetic control typically dominates under lower temperature conditions and shorter reaction times [4].

Thermodynamic Control: Favors the most stable product, with the lowest free energy, regardless of the formation pathway [35]. This control mechanism emerges when reactions are allowed to reach equilibrium, typically at higher temperatures or over extended time periods [4].

Structural Implications for Metal Clusters

The distinction between kinetic and thermodynamic control becomes particularly significant in coordination chemistry and cluster synthesis, where different metallosupramolecular assemblies can result from the same molecular building blocks. The ability to selectively target specific nuclearities and compositions through controlled metalation strategies represents an important advancement in the directed synthesis of functional molecular materials [34].

Experimental System: Metalation of H₃TPM Ligand

Ligand Design and Characteristics

The experimental system central to this case study employs the hexadentate ligand tris(5-(pyridin-2-yl)-1H-pyrrol-2-yl)methane (H₃TPM) [34]. This ligand features:

- Multiple coordination pockets with divergent binding sites

- Flexibility to accommodate different metal coordination geometries

- Ability to form stable complexes with various transition metals

- Molecular architecture conducive to stepwise metalation

Temperature-Dependent Metalation Pathways

The metalation of H₃TPM demonstrates distinct pathway selectivity based on reaction conditions:

Diagram 1: Metalation pathways of H₃TPM ligand under kinetic and thermodynamic control.

Experimental Protocols

Synthesis of Kinetic Product (Mononuclear Complex)

Method: Slow addition of Fe(II) salt to a cooled solution of H₃TPM ligand in tetrahydrofuran (THF) [34].

Critical Parameters:

- Temperature: Maintain below 0°C

- Concentration: Dilute conditions to prevent oligomerization

- Addition rate: Controlled, slow addition of metal salt

- Atmosphere: Inert conditions (Nâ‚‚ or Ar glovebox)

- Workup: Precipitation and washing at low temperature

Characterization: The mononuclear complex Na(THF)â‚„[Fe(TPM)] was characterized by X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, and mass spectrometry [34].

Synthesis of Thermodynamic Product (Trinuclear Complex)

Method: Prolonged heating of the reaction mixture or direct metalation at elevated temperature [34].

Critical Parameters:

- Temperature: 60-80°C range

- Reaction time: Extended period (hours to days)

- Solvent: Coordinating solvent system

- Equilibrium: Allow sufficient time for thermodynamic control to establish

Characterization: The trinuclear complex Fe₃(TPM)₂ was characterized by X-ray crystallography, magnetic measurements, and spectroscopic methods [34].

Cluster Expansion Protocol

Method: Post-synthetic modification of the kinetic mononuclear complex [34].

Procedure:

- Isolate and purify the kinetic mononuclear complex

- Redissolve in appropriate solvent

- Add stoichiometric amount of FeClâ‚‚ or ZnClâ‚‚

- Stir at room temperature to facilitate cluster assembly

- Isulate and characterize the resulting trinuclear clusters

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Comparison of Metalation Products

Table 1: Characteristics of kinetic versus thermodynamic metalation products

| Parameter | Kinetic Product (Mononuclear) | Thermodynamic Product (Trinuclear) |

|---|---|---|

| Nuclearity | Mononuclear Na(THF)₄[Fe(TPM)] | Trinuclear Fe₃(TPM)₂ |

| Formation Temperature | Low temperature (< 0°C) | Elevated temperature (60-80°C) |

| Reaction Time | Short (minutes to hours) | Long (hours to days) |

| Activation Energy Barrier | Lower | Higher |

| Stability | Less stable, reactive intermediate | More stable, final equilibrium product |

| Functionality | Precursor for cluster expansion | Final cluster product |

| Structural Flexibility | High (susceptible to transformation) | Low (stable architecture) |

Cluster Expansion Capabilities

Table 2: Comparison of cluster expansion from mononuclear precursor

| Expansion Parameter | FeClâ‚‚ Treatment | ZnClâ‚‚ Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Product Nuclearity | Homometallic trinuclear | Heterometallic trinuclear |

| Product Composition | Fe₃(TPM)₂ | Fe₂Zn(TPM)₂ |

| Cluster Type | Homometallic | Heterometallic |

| Structural Relationship | Isostructural frameworks | Isostructural frameworks |

| Metal Distribution | Single metal type | Controlled metal positioning |

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials and Functions

Table 3: Key research reagents for kinetic metalation studies

| Reagent | Function/Purpose | Critical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| H₃TPM Ligand | Primary hexadentate coordinating ligand | Purified, anhydrous form; structural characterization complete |

| Fe(II) Salts | Metal ion source for complex formation | Anhydrous; stored under inert atmosphere |

| Zn(II) Salts | Secondary metal for heterometallic clusters | Anhydrous; compatible with Fe chemistry |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) | Primary reaction solvent | Anhydrous, degassed; stored over molecular sieves |

| Sodium Sand | Reducing agent for certain metal precursors | Freshly prepared; particle size controlled |

| Temperature Bath | Precise temperature control for pathway selection | Low temperature capability (-78°C to 100°C) |

Mechanism and Pathway Analysis

Energy Landscape of Metalation Pathways

The selective formation of different nuclearity complexes from the same ligand can be understood through the reaction energy landscape:

Diagram 2: Energy landscape showing kinetic versus thermodynamic metalation pathways.

Structural Relationships in Cluster Formation

The isostructural nature of the final trinuclear clusters, whether homo- or heterometallic, demonstrates the robust coordinating capability of the TPM ligand framework:

Diagram 3: Structural features enabling isostructural cluster formation.

Applications and Implications

Strategic Advantages in Synthesis

The kinetic metalation approach demonstrates several significant advantages for controlled cluster synthesis:

- Nuclearity Control: Precise selection between mononuclear and trinuclear complexes through temperature manipulation [34]

- Composition Programming: Systematic variation of metal content in isostructural frameworks [34]

- Pathway Selectivity: Ability to target specific architectures through controlled reaction conditions [4]

- Precursor Strategy: Use of kinetic products as synthons for higher nuclearity clusters [34]

Relevance to Drug Development and Materials Science

For researchers in pharmaceutical and materials development, this case study illustrates important principles:

- Selectivity in Molecular Assembly: Controlled metalation mimics the selective binding in biological systems

- Structural Precision: Achievement of specific nuclearity and composition targets

- Functional Material Design: Framework for developing clusters with tailored electronic, magnetic, or catalytic properties

- Biomimetic Approaches: Inspiration for synthetic strategies mimicking metalloprotein assembly

This case study demonstrates that kinetic metalation provides a powerful strategy for selective synthesis of isostructural clusters with programmable nuclearity and metal composition. The temperature-dependent metalation of H₃TPM enables precise pathway selection, yielding either mononuclear kinetic products or trinuclear thermodynamic products from identical starting materials [34]. The methodology exemplifies how understanding and manipulating the kinetic versus thermodynamic control paradigm enables sophisticated synthetic outcomes that would be inaccessible through conventional approaches. This approach establishes a framework for programmed molecular assembly with implications for developing tailored molecular materials, catalytic systems, and functional supramolecular architectures relevant to advanced pharmaceutical and technological applications.

Leveraging Thermodynamic Control for the Most Stable Product Forms

In the synthesis of chemical products, particularly within the pharmaceutical industry, a fundamental competition often dictates the outcome: the pathway that leads to the quickest formation of a product versus the pathway that leads to the most stable product. This is the core distinction between kinetic control and thermodynamic control over reactions. Under kinetic control, the product that forms the fastest, typically via the pathway with the lowest activation energy, dominates. This product, however, is often less stable. In contrast, thermodynamic control favors the most stable product, the one with the lowest overall Gibbs free energy, even if it forms more slowly via a pathway with a higher activation energy [4] [36]. The ability to steer a reaction towards the thermodynamic product is not merely an academic exercise; it is a critical tool for ensuring the stability, efficacy, and shelf-life of solid-state pharmaceuticals, where the most stable crystalline form is often essential for consistent performance [37].

The relevance of this control is magnified in pharmaceutical development, where over 90% of newly developed drug molecules face challenges related to low solubility and bioavailability [38] [39]. The thermodynamic stability of a drug's solid form directly impacts these critical properties. Therefore, leveraging thermodynamic control is a central strategy for designing robust and efficient pharmaceutical production processes, helping to overcome some of the biggest hurdles in modern drug development [38].

Fundamental Principles and Energetics

Defining the Controlling Factors

The outcome of a chemical reaction yielding multiple products is determined by the reaction conditions, which tip the balance between kinetic and thermodynamic control.

- Kinetic Control: This regime favors the product that is formed the fastest. The product ratio depends on the relative rates of the competing reactions, which are governed by the differences in their activation energies (ΔE₠or ΔG‡). Kinetic products are favored at lower temperatures and with shorter reaction times, as there is insufficient energy to overcome the higher activation barrier of the more stable product, and the system does not have time to reach equilibrium [4] [40].

- Thermodynamic Control: This regime favors the most stable product, with the lowest Gibbs free energy. The product ratio is determined by the relative thermodynamic stabilities of the products, expressed through the equilibrium constant (Kₑᵩ). Thermodynamic products are favored at higher temperatures and with longer reaction times. The elevated temperature provides the necessary energy to overcome higher activation barriers, and the extended time allows the reaction to reach equilibrium, where the most stable product predominates [4] [36].

A key requirement for thermodynamic control is reaction reversibility. There must be a mechanism for the products to interconvert, allowing the system to equilibrate. Without reversibility, the reaction cannot escape the kinetic trap to form the most stable product [4].

Visualizing the Energy Landscape

The following reaction coordinate diagram illustrates the energetic relationship between kinetic and thermodynamic pathways for a generalized reaction, such as the addition to a conjugated diene.

- Activation Energy Barrier (

Eâ‚): The kinetic pathway has a lowerEâ‚, leading to faster product formation at low temperatures. The thermodynamic pathway has a higherEâ‚, making it slower initially [40] [5]. - Product Stability (

ΔG): The thermodynamic product is at a lower energy level (ΔG_Thermo) than the kinetic product (ΔG_Kin), making it more stable. Given sufficient energy and time, the kinetic product can often convert into the thermodynamic product [36].

Experimental Methodologies for Thermodynamic Control

Achieving thermodynamic control requires deliberate experimental design to provide the energy and time needed for the system to reach equilibrium and to selectively isolate the stable product.

Core Protocol for Favouring the Thermodynamic Product

The following workflow outlines a generalized procedure for steering a reaction toward the thermodynamic product, applicable to various systems including polymorphic forms of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and organic synthesis.

Detailed Methodological Steps:

- Reaction Setup and Solvent Selection: The reaction is set up in a high-boiling-point solvent that can dissolve the reactants and products and withstand prolonged heating. This ensures a homogeneous reaction medium conducive to reaching equilibrium [4].

- Equilibration at Elevated Temperature: The reaction mixture is heated to reflux or another elevated temperature for an extended period—often several hours or even days. This provides the thermal energy required to overcome the high activation barrier of the thermodynamic pathway and allows sufficient time for the reversible reactions to occur, enabling the system to find the global energy minimum [4] [5].

- Controlled Crystallization: After equilibration, the solution is cooled slowly to room temperature. A slow cooling rate is crucial as it prevents the kinetic product from crashing out of solution and allows the more stable thermodynamic product to crystallize selectively. Seeding the solution with crystals of the thermodynamic product can further guide this process [37].

- Product Isolation and Validation: The solid product is isolated via filtration or centrifugation. The solid-state form must be immediately characterized using techniques like Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC), Powder X-ray Diffraction (PXRD), and Hot-Stage Microscopy (HSM) to confirm the identity and purity of the thermodynamic polymorph [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Equipment for Thermodynamic Control Studies.

| Item Name | Function/Application | Context of Use in Thermodynamic Control |

|---|---|---|

| High-Boiling Solvents (e.g., DMF, DMSO) | Creates a high-temperature environment for equilibration. | Used during the prolonged heating step to enable reversibility and reach the global energy minimum [4]. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Measures melting point and heat of fusion of solids. | Used to identify the thermodynamic polymorph, which typically has a higher melting point and greater thermal stability [37]. |

| Powder X-ray Diffractometer (PXRD) | Provides a fingerprint of the crystalline structure. | Essential for distinguishing between different polymorphic forms and confirming the presence of the stable form [37]. |

| Seeding Crystals (of the thermodynamic form) | Provides a nucleation site for the desired crystal form. | Added during the crystallization step to promote selective crystallization of the thermodynamic product over the kinetic one [37]. |

| Eupalinolide K | Eupalinolide K, MF:C20H26O6, MW:362.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Glomeratose A | Glomeratose A, MF:C24H34O15, MW:562.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Comparative Data and Case Studies

Classic Organic Synthesis: Addition to Conjugated Dienes

The addition of hydrogen halides (e.g., HCl, HBr) to 1,3-butadiene is a textbook example demonstrating kinetic versus thermodynamic control, yielding distinct 1,2- and 1,4-addition products [4] [5].

Table 2: Comparison of Kinetic vs. Thermodynamic Products in HBr Addition to 1,3-Butadiene.

| Characteristic | Kinetic Product (1,2-addition) | Thermodynamic Product (1,4-addition) |

|---|---|---|

| Product Identity | 3-bromo-1-butene | 1-bromo-2-butene |

| Alkene Substitution | Monosubstituted | Disubstituted |

| Relative Stability | Less stable | More stable (greater alkene substitution) |

| Formation Rate | Faster (lower activation energy) | Slower (higher activation energy) |

| Favored Conditions | Low temperature (e.g., 0 °C), short time [40] [36] | High temperature (e.g., 40 °C), long time [4] [36] |

The rationale for this product distribution lies in the reaction mechanism. Protonation of butadiene generates a resonance-stabilized allylic carbocation. Attack by bromide at the more substituted carbon (C2) is faster (kinetic control), while attack at the less substituted carbon (C4) yields a more stable, disubstituted alkene (thermodynamic control) [5].

Pharmaceutical Solid Forms: The Case of Famotidine Polymorphs

Famotidine, a widely used Hâ‚‚-receptor antagonist, exists in multiple solid forms (polymorphs), providing a real-world case study on the importance of thermodynamic control in drug development.

Table 3: Comparison of Famotidine Polymorphs.

| Characteristic | Form B (Metastable, Kinetic) | Form A (Stable, Thermodynamic) |

|---|---|---|

| Solid-State Nature | Metastable | Thermodynamically Stable |

| Commercial Use | Yes (API in Pepcid) | No |

| Relative Solubility | Higher (initially) | Lower |

| Processing Stability | Prone to transformation during grinding, compression, or exposure to humidity [37] | Resistant to transformation under standard processing conditions [37] |

| Formation Conditions | Rapid crystallization from solution, low temperature [37] | Slow crystallization from solution, elevated temperature, or solid-state transformation of Form B [37] |

Despite Form A being the most stable polymorph, the commercial product uses the metastable Form B. This is a common strategy in pharma to leverage the higher initial solubility of a kinetic form for improved bioavailability. However, this approach requires rigorous quality control during manufacturing and storage to prevent a thermodynamically-driven transformation to the less soluble Form A, which could compromise drug product performance [37]. This highlights the critical need for understanding and controlling thermodynamics throughout a drug's lifecycle.

Implications for Pharmaceutical Development and Quality Control