Homogeneous vs. Heterogeneous Nucleation: A Comparative Analysis of Mechanisms, Outcomes, and Applications in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and materials science.

Homogeneous vs. Heterogeneous Nucleation: A Comparative Analysis of Mechanisms, Outcomes, and Applications in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and materials science. It explores the fundamental thermodynamic and kinetic distinctions between these two pathways, examining how energy barriers, stochasticity, and interfacial interactions dictate nucleation outcomes. The scope extends to methodological approaches for controlling nucleation, including the use of heteronucleants, engineered interfaces, and polymeric inhibitors, with specific applications in pharmaceutical crystallization and biologics processing. The review also addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, such as suppressing unwanted homogeneous nucleation and selecting effective crystallization inhibitors. Finally, it synthesizes validation strategies and comparative performance metrics, highlighting how the selective promotion or inhibition of a specific nucleation pathway can enhance crystal quality, drug solubility, and process efficiency in biomedical research and manufacturing.

Core Principles: Demystifying the Energetic and Kinetic Landscapes of Nucleation

Defining Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Nucleation Pathways

Nucleation, the initial formation of a new thermodynamic phase from a metastable parent phase, serves as the critical first step in processes ranging from cloud formation to pharmaceutical crystallization. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the distinct pathways of homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation is essential for controlling product purity, crystal polymorphism, and particle size distribution. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these fundamental mechanisms, supported by current experimental data and methodologies.

Homogeneous nucleation occurs spontaneously within a uniform bulk phase without the involvement of foreign surfaces, typically requiring high energy barriers to be overcome. In contrast, heterogeneous nucleation takes place on pre-existing surfaces, interfaces, or impurity particles, which significantly reduce the energy required for phase transition. The competition between these pathways directly influences critical material properties in pharmaceutical development, including bioavailability, stability, and manufacturability.

Theoretical Framework and Key Concepts

Classical Nucleation Theory Fundamentals

Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) provides the foundational framework for quantifying nucleation processes across diverse systems. CNT describes nucleation as the stochastic formation of stable nuclei through fluctuations that overcome a characteristic energy barrier. The theory predicts key parameters including critical nucleus size, nucleation rate, and energy barrier height.

For homogeneous freezing, the nucleation rate is expressed as:

J_hom = C exp(-16πvi²γiw³ / (3kTΔμiw²)) [1]

where C is a kinetic prefactor, vi is the molecular volume of ice, γiw is the interfacial tension between water and ice, and Δμiw denotes the chemical potential difference between ice and water.

The critical radius of the ice nucleus in water is given by:

R_iw* = 2viγiw / Δμiw [1]

In heterogeneous nucleation, the presence of a foreign surface reduces the energy barrier by a factor f(θ) that depends on the contact angle θ between the nucleating phase and the substrate. This fundamental difference in energy requirements creates the competitive landscape between these pathways.

Comparative Mechanism Analysis

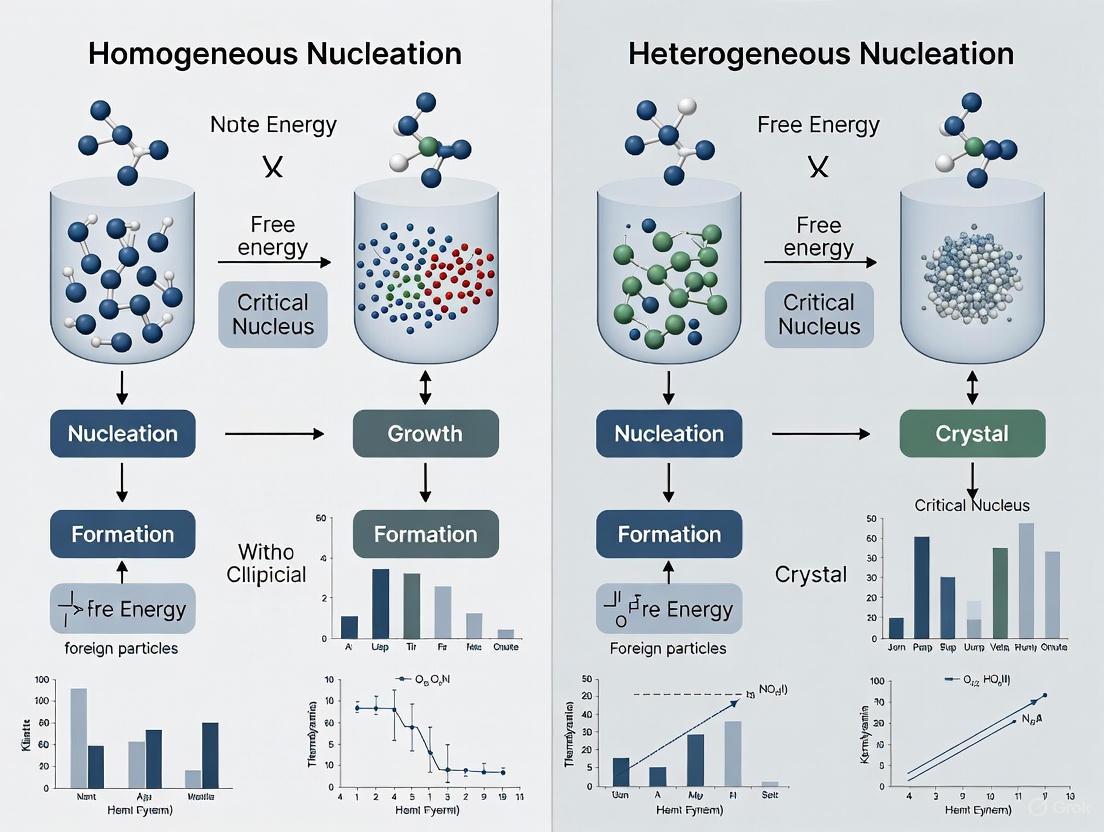

The following diagram illustrates the key differences and competitive relationships between homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation pathways:

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Atmospheric Ice Nucleation Research

Studies of ice nucleation in synoptic cirrus clouds employ sophisticated airborne measurement campaigns coupled with modeling approaches. The Midlatitude Airborne Cirrus Properties Experiment (MACPEX) utilized the NASA WB-57F science aircraft with instrumentation including:

- Two-Dimensional Stereo (2D-S) probe: Captures shadow images of ice particles from 10 μm to over 1 mm in diameter for characterizing ice crystals in cirrus clouds [2].

- Particle Analysis by Laser Mass Spectrometry (PALMS): Provides real-time, size-resolved chemical composition of aerosol particles in the 0.15-5 μm range [2].

- Closed-path tunable diode laser hygrometer (CLH): Precisely measures ice water content by collecting both water vapor and sublimated ice particles via a subisokinetic inlet [2].

Data analysis involves ice residual analysis, where ice crystals collected from cirrus clouds are evaporated and the residual particles analyzed to infer the presence and nature of ice-nucleating particles (INPs). Large-eddy simulation models like UCLALES-SALSA resolve small-scale turbulence and microphysical interactions at resolutions down to tens of meters to capture INP-driven processes [2].

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide atomic-level insights into nucleation behavior. Recent studies investigate heterogeneous nucleation characteristics of Hâ‚‚O on SiOâ‚‚ surfaces in multi-component systems:

- System construction: SiOâ‚‚ crystals of 20 Ã… are constructed using the SiOâ‚‚ cell in Materials Studio database [3].

- Simulation parameters: Simulations are conducted under NPT ensemble for 40 ns to investigate nucleation process within supersaturated water vapor environment [3].

- Analysis methods: Cluster evolution and interaction energies are tracked to identify nucleation mechanisms and competitive effects between homogeneous and heterogeneous pathways [3].

Colloidal Hard Sphere Crystallization

Experimental investigation of crystal nucleation in colloidal hard spheres employs:

- Laser-scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM): Tracks particle-level crystallization in real-time using fluorescent PMMA particles dispersed in gravity-matched solvent [4].

- Sample preparation: Sterically stabilized particles with size polydispersity of 5.75% prevent fractionation while delaying crystallization onset for adequate time resolution [4].

- Crystalline cluster identification: Uses local bond order parameters to identify clusters, with particles classified as crystalline if having at least 8 nearest neighbors within 1.4 × particle diameter and scalar product > 0.5 [4].

Comparative Experimental Data Analysis

Nucleation Pathway Characteristics

Table 1: Fundamental characteristics of homogeneous versus heterogeneous nucleation pathways

| Parameter | Homogeneous Nucleation | Heterogeneous Nucleation |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Barrier | High, requires significant supersaturation/undercooling | Significantly reduced by catalytic surfaces |

| Nucleation Rate | Sharp increase at threshold conditions | Gradual increase beginning at lower supersaturation |

| Spatial Distribution | Random throughout bulk phase | Localized at active surfaces/interfaces |

| Stochasticity | Highly stochastic | More predictable with known INP concentrations |

| Temperature Dependence | Strong temperature dependence below -38°C for ice [2] | Active across broader temperature range |

| Critical Cluster Size | Larger critical nuclei | Smaller critical nuclei stabilized by surfaces |

| Experimental Observation | Direct measurement challenging due to spontaneity | More easily quantified via surface analysis |

Quantitative Nucleation Data

Table 2: Experimental nucleation data across multiple systems

| System | Nucleation Type | Conditions | Nucleation Rate | Critical Size/Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hard Spheres [4] | Homogeneous | Φ = 0.52, MS = 0.75 | 〈J〉 = (6 ± 3) × 10â¹ mâ»Â³ sâ»Â¹ | Induction time: 395 ± 25 min |

| Synoptic Cirrus [2] | Heterogeneous (mineral dust) | Cloud-forming altitudes | INP concentration: 0.01 to 100 Lâ»Â¹ at -30°C | Depletes INPs at cloud-forming altitudes |

| Water-SiOâ‚‚ System [3] | Competitive heterogeneous/homogeneous | Multi-gas component, 40 ns simulation | Heterogeneous preferred at lower saturation | Hâ‚‚O accumulates around O atoms on SiOâ‚‚ |

| Adsorbed Water Films [1] | Homogeneous in confined geometry | 1 nm film on hydrophilic substrate | Melting point depression up to 5 K | Film must accommodate critical ice nucleus |

Competitive Interactions and Pathway Interdependence

The relationship between homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation is not merely alternative pathways but often involves complex competitive dynamics. Research demonstrates that prior heterogeneous freezing events can shape thermodynamic conditions for subsequent homogeneous nucleation [2]. In atmospheric systems, initial heterogeneous nucleation on mineral dust INPs depletes these particles from cloud-forming altitudes, potentially enabling homogeneous freezing to dominate at the time of observation despite the presence of heterogeneous characteristics earlier in the system evolution [2].

Molecular dynamics simulations of water vapor condensation on SiOâ‚‚ particles reveal that both homogeneous and heterogeneous processes occur simultaneously, with competition between them significantly influenced by environmental conditions [3]. At lower water vapor saturation, heterogeneous nucleation dominates, while higher saturation levels promote homogeneous nucleation throughout the vapor phase [3].

The following experimental workflow illustrates how these competitive interactions are investigated in atmospheric science:

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Key research materials and their applications in nucleation studies

| Material/Reagent | Function in Nucleation Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Mineral Dust Particles | Ice-nucleating particles for heterogeneous ice formation | Atmospheric ice nucleation studies [2] |

| Fluorescent PMMA Particles | Model colloidal hard spheres for direct visualization | Laser-scanning confocal microscopy [4] |

| SiOâ‚‚ Crystals | Substrate for heterogeneous nucleation studies | Molecular dynamics simulations [3] |

| cis-Decalin/TCE Mixture | Density- and refractive index-matched dispersion medium | Colloidal hard sphere experiments [4] |

| Particle Coatings (poly-hydroxy-stearic-acid) | Steric stabilization of colloidal particles | Preventing aggregation in model systems [4] |

| Fluorescent Dye (DilC18) | Particle visualization in confocal microscopy | Real-time tracking of crystallization [4] |

The comparative analysis of homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation pathways reveals a complex interplay that significantly influences phase transition outcomes across scientific disciplines and industrial applications. For drug development professionals, understanding these mechanisms enables better control over crystallization processes critical to product performance. Current research demonstrates that rather than operating in isolation, these pathways often compete and interact in dynamic ways, with prior heterogeneous events potentially shaping subsequent homogeneous nucleation.

The experimental methodologies summarized—from airborne atmospheric measurements to molecular dynamics simulations and colloidal model systems—provide complementary approaches for investigating nucleation phenomena across scales. As research continues to elucidate the intricate relationships between these fundamental processes, enhanced predictive models will emerge, offering improved strategies for controlling nucleation outcomes in pharmaceutical applications and beyond.

Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) provides the foundational framework for describing the kinetics of a phase transition, serving as a critical tool across disciplines from atmospheric science to pharmaceutical development. At the heart of CNT lies the concept of the free energy barrier (ΔGâº), which determines the rate at of formation of stable nuclei from a supersaturated parent phase. This activation barrier arises from the competition between the bulk free energy gain of the new phase and the surface free energy penalty required to create its interface. The height of this barrier dictates whether a system will remain in a metastable state or proceed rapidly toward phase separation, making its accurate quantification paramount for predicting and controlling nucleation outcomes in both natural and industrial processes.

This analysis focuses on a comparative evaluation of homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation pathways, examining how the presence of foreign surfaces or particles dramatically alters the thermodynamic landscape. While homogeneous nucleation occurs spontaneously and randomly within the bulk phase without preferential sites, heterogeneous nucleation is catalyzed by existing interfaces that effectively lower the critical energy barrier. Understanding the competition and interplay between these mechanisms is essential for applications ranging from the formation of ice crystals in cirrus clouds to the controlled crystallization of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). Recent research has illuminated the complex ways in which prior heterogeneous events can shape subsequent homogeneous nucleation, highlighting the dynamic nature of these processes that cannot be fully captured by static analysis alone [2].

Theoretical Foundations of the Free Energy Barrier

The CNT Formulation of ΔGâº

Within CNT, the free energy change associated with the formation of a spherical nucleus of the new phase is expressed as the sum of a volume term and a surface term. For a cluster containing n molecules, the Gibbs free energy is given by:

ΔG = -nΔμ + 4πr²γ

Where:

- Δμ is the chemical potential difference between the two phases (the thermodynamic driving force, often proportional to supersaturation)

- r is the radius of the nucleus

- γ is the interfacial tension between the nucleus and the parent phase

This function reaches a maximum at the critical nucleus size (râº), where the free energy barrier ΔG⺠is located. Clusters smaller than r⺠tend to dissolve, while those larger than r⺠are likely to continue growing. The critical size and associated energy barrier can be derived by setting d(ΔG)/dr = 0, yielding:

r⺠= 2γ/Δμ

ΔG⺠= 16πγ³ / (3Δμ²)

The height of this barrier exhibits an inverse square relationship with the driving force (Δμ), explaining why nucleation rates increase dramatically with increasing supersaturation. However, CNT's simplified treatment of clusters as macroscopic droplets with bulk properties represents a significant limitation, particularly for small nuclei where the continuum approximation breaks down [5].

Methodological Approaches for Probing ΔGâº

Experimental and computational methods for determining ΔG⺠have evolved significantly, moving beyond CNT's limitations:

Metastable Zone Width (MSZW) Analysis: A new mathematical model based on CNT enables direct estimation of nucleation rates and Gibbs free energy of nucleation using MSZW data as a function of solubility temperature and cooling rate. This approach has been validated across 22 solute-solvent systems, revealing nucleation rates from 10²Ⱐto 10³ⴠmolecules per m³s and Gibbs free energies ranging from 4 to 87 kJ molâ»Â¹ for various compounds including APIs, lysozyme, and inorganic materials [6].

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: MD provides atomistic insight into nucleation behavior by simulating the interactions between molecules. For water vapor phase change on SiOâ‚‚ particles, MD simulations model cluster evolution and interaction energies to analyze heterogeneous nucleation behavior and its competition with homogeneous nucleation across temperature and humidity conditions [3].

Quantum Mechanical Calculations: State-of-the-art quantum mechanics models (e.g., DLPNO-CCSD(T)/CBS and G3) calculate free energies of small water clusters (2-14 molecules), revealing that the ratio of experimentally extracted free energies to CNT predictions shows nonmonotonic behavior with cluster size at higher temperatures (>250K), challenging CNT's fundamental assumptions [5].

Comparative Analysis of Homogeneous vs. Heterogeneous Nucleation

Thermodynamic and Kinetic Differences

The presence of a foreign surface fundamentally alters the nucleation landscape by providing a template that reduces the surface energy penalty of nucleus formation. For heterogeneous nucleation on a flat, ideal surface, the free energy barrier relates to the homogeneous case through a catalytic factor:

ΔGₕₑₜ⺠= φΔGₕₒₘâº

φ = (2 + cosθ)(1 - cosθ)²/4

Where θ is the contact angle between the nucleus and the substrate, a measure of the surface's wettability and catalytic effectiveness. This relationship reveals that even weakly catalytic surfaces (θ approaching 180°) significantly reduce the barrier, while perfectly wetting surfaces (θ = 0°) eliminate it entirely.

Table 1: Comparative Free Energy Barriers in Different Systems

| System | Nucleation Type | ΔG⺠Range | Critical Nucleus Size (molecules) | Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APIs & Intermediate [6] | Primary | 4-49 kJ molâ»Â¹ | Not specified | Solution, varying cooling rates |

| Lysozyme [6] | Primary | ~87 kJ molâ»Â¹ | Not specified | Solution, varying cooling rates |

| Water Clusters [5] | Homogeneous | Varies with size | 2-14 | T > ~250K and T < ~250K |

| SiOâ‚‚ in Flue Gas [3] | Heterogeneous | Not specified | Not specified | Multi-component wet flue gas, molecular dynamics simulation |

Competitive Dynamics and Sequential Interactions

In realistic systems, homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation rarely occur in isolation, but rather compete and interact in complex ways:

Preferential Initiation: Heterogeneous nucleation typically initiates at lower supersaturations because of its reduced energy barrier. In cirrus cloud formation, for example, heterogeneous freezing on mineral dust ice-nucleating particles (INPs) occurs before homogeneous freezing becomes possible [2].

Particle Depletion Mechanism: Prior heterogeneous nucleation events can remove active nucleating particles from the system, subsequently favoring homogeneous nucleation. In synoptic cirrus, initial heterogeneous freezing on mineral dust INPs depletes these particles from cloud-forming altitudes, enabling homogeneous freezing to dominate at the time of observation despite the presence of conditions that would otherwise favor heterogeneous mechanisms [2].

Simultaneous Competition: Molecular dynamics simulations of water vapor condensation on SiOâ‚‚ particles reveal that homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation occur simultaneously with competition between them. Heterogeneous nucleation preferentially occurs around oxygen atoms on the SiOâ‚‚ surface at lower water vapor saturation, while homogeneous nucleation requires higher supersaturation levels but then proceeds rapidly [3].

Experimental Protocols for ΔG⺠Determination

Protocol 1: Metastable Zone Width (MSZW) Analysis for Solution Nucleation

This methodology enables determination of nucleation kinetics from readily measurable MSZW data, providing a practical approach for pharmaceutical and materials science applications.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for MSZW Analysis

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| APIs (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients) | Model solute systems for nucleation studies [6] |

| Lysozyme | Large protein molecule for studying macromolecular nucleation [6] |

| Glycine | Amino acid model system for biological molecule nucleation [6] |

| Inorganic Compounds (8 systems) | Broadening model system diversity [6] |

| Solvents | Creating supersaturated solutions through temperature control |

| Temperature Control System | Precise cooling rate manipulation for MSZW determination |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Prepare saturated solutions at known equilibrium temperatures for each solute-solvent system.

- Apply controlled linear cooling rates (typically 0.1-1.0 K/min) to generate supersaturation.

- Detect nucleation onset through turbidity measurements, laser backscattering, or visual observation.

- Record the temperature difference between saturation and nucleation onset (MSZW) for each cooling rate.

- Apply the CNT-based model to extract nucleation rates, kinetic constants, and Gibbs free energies using the relationship between MSZW, cooling rate, and solubility temperature.

- Validate models by predicting induction times and thermodynamic parameters (surface free energy, critical nucleus size, number of unit cells) [6].

Protocol 2: Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Competitive Nucleation

MD simulations provide atomistic-level insights into the competition between heterogeneous and homogeneous nucleation mechanisms, particularly valuable for systems where direct experimental observation is challenging.

Computational Workflow:

- System Construction: Build the simulation box containing a spherical SiOâ‚‚ particle (20Ã…) at the center, surrounded by a multi-component gas mixture (Nâ‚‚, Oâ‚‚, COâ‚‚, Hâ‚‚O) representing flue gas conditions [3].

- Force Field Selection: Employ established interatomic potentials (e.g., Tersoff parameterization for Si-O systems) to describe molecular interactions [3].

- Ensemble Configuration: Run simulations under NPT ensemble (constant number of particles, pressure, and temperature) for sufficient duration (e.g., 40 ns) to observe nucleation events [3].

- Process Monitoring: Track the spatial and temporal evolution of Hâ‚‚O molecule organization around particles, identifying nucleation initiation sites and rates.

- Competition Analysis: Quantify the relative prevalence of heterogeneous nucleation (on particle surfaces) versus homogeneous nucleation (in the vapor phase) under varying temperature and humidity conditions.

- Energy Calculations: Compute interaction energies between Hâ‚‚O molecules and particle surfaces to understand the thermodynamic drivers of heterogeneous nucleation preference [3].

Research Toolkit: Essential Methods and Reagents

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit for Nucleation Barrier Research

| Tool/Reagent | Function in Nucleation Research | Representative Application |

|---|---|---|

| Deep Docking Pipeline [7] | Identifies nucleation inhibitors from ultra-large chemical libraries | Discovery of high-affinity secondary nucleation inhibitors of Aβ42 aggregation for Alzheimer's disease |

| UCLALES-SALSA Model [2] | Large-eddy simulation for atmospheric ice nucleation | Resolving small-scale turbulence and microphysical interactions in cirrus cloud formation |

| FHH Adsorption Model [1] | Describes substrate-adsorbate interactions in confined geometries | Modeling homogeneous ice nucleation in adsorbed water films on insoluble substrates |

| PALMS Instrument [2] | Provides real-time, size-resolved chemical composition of aerosol particles | Ice residual analysis in cirrus clouds to infer nucleation mechanisms |

| 2D-S Probe [2] | Captures shadow images of ice particles for size distribution analysis | Characterizing ice crystals in cirrus clouds with detection from 10µm to over 1mm |

| ZK824859 | ZK824859, MF:C23H22F2N2O4, MW:428.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pde4-IN-24 | Pde4-IN-24, MF:C20H18F2N4O3S, MW:432.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualization of Nucleation Pathways and Methodologies

The comparative analysis of homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation through the lens of Classical Nucleation Theory reveals a complex landscape where the free energy barrier ΔG⺠serves as the critical determinant of phase transition kinetics. The experimental data compiled in this guide demonstrates that ΔG⺠values span orders of magnitude across different systems—from approximately 4 kJ molâ»Â¹ for simple APIs to 87 kJ molâ»Â¹ for complex biomolecules like lysozyme [6]—highlighting the profound influence of molecular specificity on nucleation thermodynamics.

The recognition that homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation pathways frequently compete and interact in dynamic systems represents a paradigm shift with significant implications for both basic research and industrial applications. In atmospheric science, this understanding explains observed cirrus cloud properties that cannot be predicted by considering either mechanism in isolation [2]. In pharmaceutical development, accounting for these competitive dynamics enables better control over crystal polymorphism and particle size distribution during API manufacturing [6]. In environmental engineering, understanding the preferential nucleation of water vapor on SiOâ‚‚ particles informs strategies for fine particle removal from flue gases [3].

Future research directions should focus on developing multi-scale models that seamlessly connect molecular-level interactions with macroscopic nucleation phenomena, further refining our ability to predict and manipulate ΔG⺠across diverse applications. As computational methods continue to advance—enabled by techniques like molecular dynamics, deep docking, and quantum mechanical calculations [7] [3] [5]—our capacity to design materials and processes with precisely controlled nucleation behavior will undoubtedly transform fields from medicine to climate science.

The Stochastic Nature of Nucleation and Induction Time

Nucleation, the initial formation of a new thermodynamic phase from a parent phase, is fundamentally a stochastic process, meaning it occurs randomly with a probability that can be quantified statistically. This phenomenon is critically important across scientific and industrial domains, from the production of pharmaceutical crystals with specific bioavailability to the understanding of protein aggregation in neurodegenerative diseases. The "induction time" or "lag time"—the period between the creation of a supersaturated or supercooled state and the appearance of detectable nuclei—is not a fixed value but varies significantly even under identical conditions. This variation originates from the microscopic, random nature of molecular collisions that must overcome a specific energy barrier to form a stable nucleus.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of homogeneous nucleation, which occurs spontaneously from the bulk solution without foreign surfaces, and heterogeneous nucleation, which is catalyzed by impurities, container walls, or other interfaces. Understanding their distinct outcomes is essential for controlling crystallization processes in research and industrial applications, particularly in drug development where crystal form, size, and purity are critical to a product's efficacy and safety.

Quantitative Comparison of Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Nucleation

The core difference between homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation lies in the energy barrier. Heterogeneous nucleation occurs at a lower energy barrier because the foreign surface reduces the interfacial energy penalty for creating a new phase. This results in markedly different experimental observables, most clearly seen in the statistical distribution of induction times and the resulting nucleation rates.

Table 1: Comparative Outcomes of Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Nucleation

| Characteristic | Homogeneous Nucleation | Heterogeneous Nucleation |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Barrier | Higher, requires greater supersaturation/undercooling | Lower, occurs at lower supersaturation/undercooling |

| Induction Time Distribution | Wider distribution, highly stochastic [8] | Narrower distribution, more predictable [9] |

| Experimental Nucleation Rate | Lower for a given temperature | Higher for a given temperature [9] |

| Nucleation Site | Randomly throughout the bulk volume | Preferentially at active sites (e.g., impurities, surfaces) |

| Resulting Crystal Microstructure | Fine, uniform grain structure | Larger, often columnar or "coast-island" structures [9] |

The data in Table 1 is supported by direct stochastic experiments. For instance, a study on lithium disilicate glass performed 284 runs under identical undercooling conditions, measuring the crystallization onset time each time. The statistical analysis revealed a heterogeneous crystal nucleation rate of (9.19 ± 0.04) × 10â»â´ sâ»Â¹, with the distribution of onset times confirming the random, stochastic nature of the process [9]. In contrast, homogeneous nucleation in the same system was observed at much larger undercoolings, with a different kinetic profile that forms a distinct "nose" on a Time-Temperature-Transformation (TTT) diagram [9].

Table 2: Experimentally Determined Nucleation Parameters in Different Systems

| System / Study | Nucleation Type | Measured Nucleation Rate | Key Parameter (e.g., Energy Barrier) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lithium Disilicate Glass at 1173 K [9] | Heterogeneous (on PtRh-crucible) | (9.19 ± 0.04) × 10â»â´ sâ»Â¹ | Derived from induction time statistics of 284 runs |

| Racemic Diprophylline in 1 ml solutions [8] | Heterogeneous | Varies by solvent (rate determined from induction time distribution) | Energy barrier much higher in solvent with longer induction times |

| ZIF-8 Crystallization modulated by Emodin [10] | Surface-specific (capping agent) | Not directly quantified | Emodin decreases Gibbs free energy and influences crystal growth rates on {100} facets |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Nucleation Studies

The Stochastic Approach to Measuring Induction Times

This methodology leverages the inherent randomness of nucleation by repeating an experiment numerous times under identical conditions to build a statistically significant distribution of induction times [11] [8] [9].

- Sample Preparation and Levitation: A large number (N ∼ 150–300) of identical microdroplets (1–20 μm in diameter) of a supersaturated solution are simultaneously levitated in a solvent atmosphere using a linear quadrupole electrodynamic levitator trap (LQELT). This containerless processing minimizes unwanted heterogeneous nucleation from container walls [11].

- Establishing Supersaturation: At a defined moment (tâ‚€), the environment is controlled to establish a precise state of supersaturation or undercooling in all droplets simultaneously.

- Optical Monitoring: A specialized optical system, based on the scattering of monochromatic polarized light, enables fast, simultaneous observation of nucleation events in each levitated microdroplet.

- Data Collection: The induction time for each droplet—defined as the time elapsed between t₀ and the moment a nucleus is detected—is recorded.

- Statistical Analysis: The complete set of N different induction times constitutes the nucleation statistics. This data is fitted to probability distribution models (e.g., a first-order reaction model) to extract the average nucleation rate and understand the underlying stochastic properties [11] [9].

Regulating Nucleation via Molecular Modifiers

This protocol describes an alternative approach where specific molecules are used to actively regulate the nucleation process and crystal growth, as demonstrated with the metal-organic framework ZIF-8 [10].

- One-Pot Synthesis: The reaction is set up at room temperature (∼25 °C) using an aqueous solution of 2-methylimidazole (2MI) as the reaction medium to ensure safety and simplicity.

- Introduction of Modifier: A regulator molecule, such as the anthraquinone derivative emodin, is introduced into the Zinc acetate / 2MI reaction system. The regulator is dissolved in a minimal amount of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) first if needed.

- Crystallization and Modulation: The mixture is left to crystallize. The regulator molecule acts on the process by decreasing the Gibbs free energy of the system and functioning as a capping agent for specific crystal facets (e.g., {100} facets), thereby manipulating the final particle size and morphology.

- Characterization: The resulting ZIF-8 crystals are characterized for particle size and morphology using techniques like dynamic light scattering (DLS) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The relationship between the regulator's chemical structure (e.g., the integrity of the anthraquinone structure and the number of hydroxyl groups) and its regulatory effect is analyzed [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Nucleation Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Linear Quadrupole Electrodynamic Levitator Trap (LQELT) | Enables containerless processing of many microdroplets simultaneously to minimize wall-induced heterogeneous nucleation and collect induction time statistics [11]. | Stochastic nucleation experiments in supercooled liquids or solutions [11]. |

| Emodin (Anthraquinone) | Acts as a regulator of nucleation thermodynamics and a capping agent for specific crystal facets, controlling the final size and morphology of crystals [10]. | Producing size-tuned ZIF-8 metal-organic frameworks for drug delivery applications [10]. |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Serve as a sustainable and tunable reaction medium that can modulate nucleation kinetics, crystal polymorphism, and crystal habit [12]. | Green crystallization of pharmaceutical ingredients and biomolecules [12]. |

| Platinum-Rhodium (PtRh) Crucible | Provides a highly active surface for catalyzing heterogeneous nucleation in high-temperature melts [9]. | Studying heterogeneous crystal nucleation in lithium disilicate glass [9]. |

| Monoclonal Polarized Light Source | Enables fast, non-invasive detection of nucleation events in levitated droplets or other experimental setups by detecting changes in light scattering [11]. | Determining the exact moment of nucleation in stochastic experiments [11]. |

| ABP 25 | ABP 25, MF:C55H66ClN5O3, MW:880.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Edpetiline | Edpetiline, MF:C27H43NO2, MW:413.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The comparative analysis confirms that the stochastic nature of nucleation is a universal principle, observable in both homogeneous and heterogeneous pathways. The key distinction lies in the magnitude of the energy barrier and the resulting statistical distribution of induction times. Heterogeneous nucleation, with its lower barrier, exhibits a narrower, more predictable distribution of induction times and higher observable rates under equivalent conditions. The choice between fostering homogeneous or heterogeneous nucleation is not merely academic; it has direct consequences on the critical cooling rates needed to form glasses, the microstructure of glass-ceramics, and the size and morphology of pharmaceutical crystals. Mastering the statistics of induction times through the described experimental protocols provides researchers with the data needed to predict, control, and optimize crystallization outcomes across diverse scientific and industrial landscapes.

The Role of Supersaturation as the Universal Driving Force

Supersaturation represents the fundamental deviation from thermodynamic equilibrium wherein a solution contains a higher solute concentration than its equilibrium solubility at a given temperature and pressure [13]. This condition creates the essential driving force required for all crystallization processes, establishing a non-equilibrium state that the system seeks to resolve through the formation of a solid phase [13]. The chemical potential difference (Δμ) between the supersaturated solution and the crystalline state quantitatively defines this driving force, with the supersaturation ratio (S) expressed as S = a/a, where a is the activity in the supersaturated solution and a is the activity at equilibrium [13].

In practical terms, for a cooling crystallization process, a solution becomes supersaturated as its temperature decreases below the saturation point, entering a metastable zone where the system remains in a liquid state despite being thermodynamically primed for phase transformation [13]. The width of this metastable zone varies significantly across different systems, ranging from just 1-2°C for simple inorganic salts to 20-40°C or more for complex pharmaceutical compounds, reflecting the kinetic barriers to nucleation [13]. Understanding and controlling supersaturation is particularly crucial in pharmaceutical development, where it directly influences critical quality attributes of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), including crystal form, particle size distribution, purity, and ultimately, drug efficacy and stability [14] [15].

Theoretical Framework: Classical and Modern Nucleation Theories

Classical Nucleation Theory

Classical Nucleation Theory (CNT) provides the foundational framework for understanding nucleation kinetics, modeling the process as a balance between the free energy gain from phase transformation and the energy cost of creating new interface [16]. According to CNT, the formation of a crystalline nucleus requires overcoming a characteristic free energy barrier (ΔG*) described by the relationship ΔG(n) = -nΔμ + 6a²n²â„³α, where n represents the number of molecules in the cluster, Δμ is the chemical potential difference driving crystallization, and α is the interfacial free energy [16].

The nucleation rate (J), defined as the number of nuclei formed per unit volume per unit time, follows an Arrhenius-type dependence on this energy barrier: J = νZnexp(-ΔG/kBT) [16]. Within this equation, ν* represents the attachment frequency of molecules to the nucleus, Z is the Zeldovich factor accounting for the width of the energy barrier, n is the molecular number density, kB is Boltzmann's constant, and T is temperature [16]. This theoretical framework predicts that nucleation rates increase dramatically with supersaturation, as higher supersaturation levels significantly reduce the nucleation barrier ΔG* [16].

Advancements Beyond Classical Theory

Recent research has revealed limitations in CNT, particularly its underestimation of actual nucleation rates observed in experimental systems [16]. The two-step nucleation mechanism has emerged as an important alternative explanation, proposing that crystalline nuclei form within pre-existing metastable clusters of dense liquid hundreds of nanometers in size [16]. This mechanism, initially demonstrated for protein crystals but since validated for small organic molecules, colloids, polymers, and biominerals, helps explain several long-standing puzzles in crystallization kinetics [16].

At high supersaturation levels typical of most crystallizing systems, the concept of the solution-crystal spinodal suggests that the nucleation barrier becomes negligible, enabling direct and barrier-free formation of crystal embryos [16]. This regime provides powerful opportunities for controlling nucleation by manipulating solution thermodynamic parameters and has significant implications for polymorph selection [16].

Comparative Analysis: Homogeneous vs. Heterogeneous Nucleation

Fundamental Distinctions and Experimental Discrimination

Homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation processes are primarily discriminated by their relationship to supersaturation levels and the presence of preferential nucleation sites [17]. Experimental studies with model proteins (lysozyme, glucose isomerase, and thaumatin) demonstrate that homogeneous nucleation dominates at high supersaturation, while heterogeneous nucleation prevails at lower supersaturation levels where surfaces facilitate the nucleation process by reducing the energy barrier [17].

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Nucleation

| Characteristic | Homogeneous Nucleation | Heterogeneous Nucleation |

|---|---|---|

| Supersaturation Requirement | High | Low to moderate |

| Nucleation Sites | Bulk solution, no preferential sites | Foreign surfaces, impurities, or interfaces |

| Energy Barrier | Higher | Reduced by surface interactions |

| Experimental Observation | Crystals form throughout solution volume | Crystals form preferentially on surfaces |

| Induction Time | Generally longer at equivalent supersaturation | Shorter due to lowered barrier |

| Surface Charge Dependence | Independent | Highly dependent on charge distribution |

The experimental discrimination between these mechanisms relies on controlled vapor diffusion experiments using platforms such as the "crystallization mushroom," which maintains identical chemical environments while testing different functionalized surfaces [17]. Research findings indicate that the superficial charge distribution of functionalized surfaces primarily affects nucleation frequency rather than the absolute charge value itself [17].

Quantitative Kinetics and Interfacial Energy

Advanced analytical approaches enable the determination of nucleation kinetics through both metastable zone width (MSZW) and induction time measurements [18]. A linearized integral model based on Classical Nucleation Theory allows researchers to determine interfacial energy (γ) and the pre-exponential factor (A) using cumulative distributions of MSZW data, with consistent results obtained from induction time measurements for systems including isonicotinamide, butyl paraben, dicyandiamide, and salicylic acid [18].

The mathematical relationship for nucleation rate follows the form derived from CNT: J = AJexp[-16πvm²γ³/(3kB³T³ln²S)] where vm is molecular volume, kB is Boltzmann's constant, T is temperature, and S is supersaturation ratio [18]. This fundamental relationship underscores how interfacial energy and supersaturation collectively govern nucleation kinetics across different experimental methodologies.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Induction Time and Metastable Zone Width Measurements

The measurement of induction times and metastable zone widths provides critical experimental data for quantifying nucleation kinetics [18] [19] [15]. The standard protocol involves:

Solution Preparation: Prepare saturated solutions at known initial concentrations and temperatures [18] [15]. For pharmaceutical compounds like alpha-mangostin, this may require using biorelevant dissolution media such as 50 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.4 with a minimal amount of co-solvent (e.g., 2-3% DMSO) to ensure adequate drug dissolution [15].

Supersaturation Generation: Create supersaturated conditions through appropriate methods:

Nucleation Detection: Monitor for nucleation events using:

Data Collection: Record the time interval between supersaturation establishment and first crystal detection (induction time, ti) or the temperature difference between saturation and detection points (MSZW, ΔTm) across multiple experimental runs to account for stochastic variation [18] [15].

Statistical Analysis: Apply cumulative distribution functions to the collected data, with the median value (50% of fraction detected nucleation events) providing the most reliable indicator for a random nucleation process [18].

Polymer Inhibition Studies

Evaluating the impact of polymeric additives on nucleation kinetics follows specific experimental protocols [15]:

Polymer Solution Preparation: Dissolve polymers (HPMC, PVP, Eudragit, etc.) in the selected dissolution media at specified concentrations (typically 500 μg/mL) [15].

Supersaturated Solution Preparation: Add a concentrated stock solution of the model compound (e.g., alpha-mangostin at 1500 μg/mL in DMSO) to the polymer solutions, maintaining final DMSO concentrations below 2% (v/v) to minimize solvent effects [15].

Nucleation Monitoring: Maintain solutions under constant stirring (150 rpm) at controlled temperature (25°C), with periodic sampling through 0.45-μm membrane filters followed by HPLC analysis to determine dissolved drug concentration over time [15].

Characterization of Interactions: Employ complementary techniques to elucidate polymer-drug interactions:

- FT-IR Spectroscopy: Detect potential molecular interactions through spectral shifts [15].

- NMR Measurements: Identify specific functional group interactions [15].

- In Silico Modeling: Predict binding affinities and interaction sites computationally [15].

- Viscosity Measurements: Confirm that observed effects stem from molecular interactions rather than bulk viscosity changes [15].

Experimental Workflow for Nucleation Kinetics Determination

Data Presentation and Comparative Analysis

Quantitative Comparison of Nucleation Kinetics

Table 2: Experimental Nucleation Kinetics for Model Systems

| Compound/System | Supersaturation Ratio (S) | Nucleation Type | Interfacial Energy (mJ/m²) | Induction Time | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lysozyme | High (>threshold) | Homogeneous | Not specified | Shorter at high S | Homogeneous dominance at high supersaturation [17] |

| Lysozyme | Low ( | Heterogeneous | Not specified | Longer at low S | Functionalized surfaces reduce waiting time from 2 days to 1 day [17] |

| Isonicotinamide | Variable | Both | Consistent between methods | Measured | Interfacial energy from MSZW consistent with induction time data [18] |

| Butyl Paraben | Variable | Both | Consistent between methods | Measured | Linearized integral model validated across techniques [18] |

| Alpha-Mangostin with PVP | Supersaturated | Inhibited | Not specified | Significantly extended | PVP most effective polymer for maintaining supersaturation [15] |

| Alpha-Mangostin with HPMC | Supersaturated | Uninhibited | Not specified | Minimal effect | HPMC showed negligible inhibition of nucleation [15] |

Polymer Effectiveness in Nucleation Inhibition

Table 3: Comparative Effectiveness of Polymers in Inhibiting Nucleation

| Polymer | Inhibition Effectiveness | Mechanism of Action | Key Evidence | Implications for Formulation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | High - long-term maintenance | Drug-polymer interaction via methyl group with carbonyl of drug | FT-IR, NMR, and in silico studies confirm strongest interaction | Preferred for supersaturated formulations requiring extended stability |

| Eudragit | Moderate - short-term (15 min) | Moderate drug-polymer interaction | Spectral evidence of interaction, weaker than PVP | Suitable for immediate-release formulations with shorter absorption windows |

| Hypromellose (HPMC) | Low - negligible inhibition | Minimal observed interaction with model drug | No significant spectral changes or nucleation delay | Less suitable for crystallization inhibition in this system |

| Water-Soluble Chitosan | Context-dependent | Not soluble in biorelevant media | Effective in pure water but not buffer systems | Limited application for intestinal-targeted formulations |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Nucleation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Nucleation Research | Application Context | Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functionalized Surfaces | Promote heterogeneous nucleation at lower supersaturation | Protein crystallization optimization | Surface charge distribution more critical than absolute charge [17] |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | Inhibit nucleation via specific drug-polymer interactions | Maintaining supersaturation of poorly soluble drugs | Effectiveness depends on interaction strength, not viscosity [15] |

| Hypromellose (HPMC) | Potential crystallization inhibitor | Supersaturation maintenance in formulations | System-dependent effectiveness; may show negligible inhibition [15] |

| Eudragit Polymers | pH-dependent nucleation inhibition | Targeted drug delivery systems | Provides moderate, short-term inhibition in some systems [15] |

| Alpha-Mangostin | Model poorly water-soluble compound | Studying nucleation inhibition mechanisms | Requires minimal DMSO cosolvent (<3%) in biorelevant media [15] |

| Lysozyme | Model protein for nucleation studies | Discrimination between homogeneous/heterogeneous mechanisms | Demonstrates clear supersaturation threshold for nucleation type [17] |

| IZ-Chol | IZ-Chol, MF:C34H55N3O2, MW:537.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Panclicin C | Panclicin C, MF:C25H45NO5, MW:439.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Implications for Pharmaceutical Development

The controlled induction of nucleation through supersaturation management has profound implications for pharmaceutical development, particularly in drug delivery system optimization [14] [15]. Amorphous solid dispersions designed to generate supersaturated solutions represent a leading strategy for enhancing the bioavailability of poorly water-soluble drugs, which constitute approximately 75% of current drug development candidates [15]. In these systems, the inhibition of nucleation becomes paramount for maintaining supersaturation throughout the gastrointestinal transit time, typically 1-3 hours, to ensure adequate drug absorption [15].

The selection of appropriate polymeric inhibitors depends critically on understanding their mechanism of action at a molecular level [15]. Research demonstrates that specific drug-polymer interactions rather than bulk solution properties like viscosity are primarily responsible for effective nucleation inhibition [15]. For instance, the superior performance of PVP in maintaining alpha-mangostin supersaturation stems from specific interactions between the polymer's methyl groups and the drug's carbonyl groups, as confirmed by FT-IR and NMR studies [15].

Supersaturation Control in Pharmaceutical Development

Furthermore, the discrimination between homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation mechanisms enables more precise control over crystal form and particle size distribution [16]. Since nucleation determines the initial selection of crystalline polymorphs, understanding how supersaturation levels and surface properties influence this selection is crucial for ensuring consistent production of the desired API form with optimal therapeutic performance [14] [16]. The recent identification of the solution-crystal spinodal regime at high supersaturations provides additional strategies for controlling polymorph selection through manipulation of thermodynamic parameters [16].

In conclusion, supersaturation serves as the universal driving force for nucleation processes, with its careful manipulation and control enabling researchers to direct crystallization outcomes for specific pharmaceutical applications. The comparative analysis of homogeneous versus heterogeneous nucleation mechanisms provides the scientific foundation for developing optimized drug products with enhanced performance characteristics.

Interfacial Energy and Contact Angle in Heterogeneous Nucleation

Nucleation, the initial step in the formation of a new thermodynamic phase, governs the kinetics and outcomes of phase transitions across diverse scientific and industrial fields. This process occurs through two primary pathways: homogeneous nucleation, which proceeds spontaneously within a uniform parent phase, and heterogeneous nucleation, which is facilitated by foreign surfaces or impurities. The critical distinction between these mechanisms lies in their energy requirements; heterogeneous nucleation typically dominates in real-world systems because it occurs at significantly lower energy barriers due to the involvement of pre-existing interfaces [20]. Within classical nucleation theory (CNT), the interplay between interfacial energy and contact angle provides the fundamental framework for quantifying nucleation barriers and predicting nucleation rates [20] [21]. This comparative analysis examines how these parameters dictate nucleation outcomes across different systems, with particular emphasis on applications in materials science and pharmaceutical development where controlling crystallization processes is essential.

The mathematical formalism of CNT establishes that the efficiency of a nucleating substrate is primarily determined by its ability to reduce the thermodynamic barrier to nucleus formation. This reduction is quantified through the potency factor, which depends on the contact angle established at the substrate-liquid-nucleus interface [20] [21]. Recent investigations continue to validate the remarkable robustness of CNT even for chemically heterogeneous surfaces, demonstrating that nuclei can maintain fixed contact angles through pinning mechanisms at domain boundaries [21]. This theoretical foundation enables researchers to systematically design and select nucleating agents for specific applications, from grain refinement in metallurgy to controlling polymorphism in pharmaceutical compounds.

Theoretical Framework: The CNT Perspective

Homogeneous Nucleation Barrier

Classical nucleation theory provides a quantitative description of the nucleation process by considering the balance between volume and surface free energy terms. For homogeneous nucleation, the free energy change associated with the formation of a spherical nucleus of radius r is expressed as:

ΔG_hom = (4/3)πr³Δg_v + 4πr²γ

where Δg_v is the Gibbs free energy change per unit volume (negative for a favorable transition), and γ is the interfacial free energy per unit area between the nascent phase and the parent phase [20]. This energy relationship produces a maximum that represents the nucleation barrier—the energy that must be overcome for a stable nucleus to form. The critical radius (r_c) and the corresponding nucleation barrier (ΔG*_hom) are derived by differentiating the free energy equation:

r_c = 2γ/|Δg_v|

ΔG*_hom = 16πγ³/(3|Δg_v|²)

These relationships reveal that the nucleation barrier is exquisitely sensitive to the interfacial energy, scaling with its cube [20]. This profound dependence explains why minor variations in interfacial properties can dramatically alter nucleation kinetics across different systems.

Heterogeneous Nucleation and the Potency Factor

Heterogeneous nucleation modifies this energy landscape by introducing a foreign substrate that reduces the surface energy component required for nucleus formation. In CNT, the nucleus typically assumes a spherical cap geometry on the substrate surface, characterized by a contact angle (θ) that reflects the balance of interfacial energies according to Young's equation [20]. The resulting reduction in the nucleation barrier is encapsulated by the potency factor:

ΔG*_het = f(θ)ΔG*_hom

f(θ) = [2 - 3cosθ + cos³θ]/4

where f(θ) represents the volume fraction of a spherical critical nucleus that would form heterogeneously compared to its homogeneous counterpart [20] [21]. This geometric factor decreases monotonically with the contact angle, approaching zero for perfectly wetting conditions (θ → 0°) and unity for non-wetting systems (θ → 180°) where the substrate provides no catalytic effect. The relationship between contact angle and barrier reduction is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Relationship Between Contact Angle and Nucleation Barrier Reduction

| Contact Angle (θ) | Potency Factor f(θ) | Barrier Reduction | Catalytic Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|---|

| 180° | 1 | 0% | None |

| 90° | 0.5 | 50% | Moderate |

| 30° | ~0.02 | ~98% | High |

| 0° | 0 | 100% | Perfect |

The contact angle itself is determined by the specific interactions between the substrate and the crystallizing phase. A small contact angle indicates strong affinity between the substrate and the nucleus, resulting in more effective catalytic behavior for nucleation [20]. Recent molecular dynamics studies have demonstrated that even on chemically heterogeneous surfaces with alternating liquiphilic and liquiphobic patches, the spherical cap assumption and constant contact angle premise of CNT remain surprisingly robust, with nuclei maintaining fixed contact angles through pinning at patch boundaries [21].

Comparative Analysis: Experimental Evidence

Metallic Alloy Systems

Experimental investigations in metallic systems provide compelling evidence for the critical role of interfacial energy and contact angle in heterogeneous nucleation. In magnesium alloys inoculated with spherical Zr particles, the catalytic effectiveness directly correlates with substrate size and undercooling requirements [22]. The critical undercooling (ΔT_crit) follows a predictable relationship with particle diameter (d_p):

ΔT_crit = 4γ_SL T_m/(d_p L_v)

where γ_SL is the solid-liquid interfacial energy, T_m is the melting temperature, and L_v is the latent heat of fusion per unit volume [22]. This inverse relationship between substrate size and required undercooling demonstrates how interfacial energy parameters govern nucleation behavior in practical applications.

For magnesium alloy systems, this relationship becomes quantitatively specific:

ΔT_crit = 0.719/d_p (μm)

This equation predicts that effective inoculation requires both potent substrates (small θ) and sufficient particle size, explaining why zirconium serves as an exceptional grain refiner for magnesium alloys while remaining ineffective for aluminum systems [22]. The experimental validation of these theoretical predictions across different alloy systems underscores the universal applicability of the CNT framework for metallic materials.

External Field Effects

Recent advances in nucleation control have demonstrated that external fields can modulate interfacial interactions to alter nucleation behavior. A 2025 study on the heterogeneous nucleation of aluminum on single-crystal Al₂O₃ substrates revealed that applying a static magnetic field (SMF) increased nucleation temperature by 4.7°C [23]. This enhancement was attributed to changes in crystallographic matching at the interface, which effectively reduced the interfacial energy and consequently decreased the required undercooling.

Electron backscattered diffraction and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy analysis showed that the magnetic field induced angle deviations in matching planes at the interface [23]. These structural modifications altered the orientation relationships between the nucleating crystal and the substrate, effectively changing the contact angle and improving the catalytic potency of the substrate. This research opens new possibilities for controlling solidification processes in metals through external field manipulation of interfacial properties.

Pharmaceutical and Biologic Systems

The principles of heterogeneous nucleation find crucial applications in pharmaceutical development, where controlling crystallization is essential for product performance and stability. While small-molecule drugs have traditionally dominated therapeutics, emerging modalities including nucleic acid drugs, monoclonal antibodies, and cell therapies present new nucleation control challenges [24] [25]. The structural complexity of these biological therapeutics introduces additional considerations for interfacial energy management during formulation and storage.

In nucleic acid therapeutics, delivery systems such as lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) must overcome significant interfacial energy barriers to facilitate cellular uptake and endosomal escape [25]. These challenges parallel those in classical nucleation theory, where the interface between dissimilar phases governs the kinetics of structural transformations. The development of chemical modification strategies and advanced delivery systems for nucleic acid drugs represents a modern application of interfacial energy control principles to overcome biological barriers [25].

Methodologies: Experimental Approaches and Protocols

Computational Analysis Techniques

Molecular dynamics simulations have emerged as powerful tools for investigating nucleation mechanisms at atomic resolution. Recent studies employ sophisticated sampling algorithms like jumpy forward flux sampling to overcome the inherent rarity of nucleation events [21]. Typical protocols involve:

- System Setup: Creating simulation boxes with supercooled liquids confined within slit pores formed between nucleating substrates and repulsive walls

- Interaction Potentials: Using truncated and shifted Lennard-Jones potentials with carefully parameterized interaction strengths between liquid particles and substrate particles

- Surface Patterning: Designing chemically heterogeneous surfaces with alternating liquiphilic and liquiphobic patches to mimic real-world impurities

- Analysis Methods: Tracking nucleus formation using order parameters and calculating contact angles from the spatial distribution of crystalline atoms

These computational approaches enable direct visualization of the pinning mechanism that maintains constant contact angles on heterogeneous surfaces, providing molecular-level validation of CNT principles [21].

Experimental Characterization Methods

Experimental validation of nucleation theories relies on techniques that can probe both structural and kinetic aspects of phase transitions:

- Electron Backscattered Diffraction: Characterizes crystallographic orientation relationships at interfaces with high spatial resolution [23]

- High-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy: Resolves atomic-scale structures at nucleation interfaces, revealing lattice matching and epitaxial relationships [23]

- Undercooling Measurements: Quantifies the thermodynamic driving force required to initiate nucleation on different substrates [22]

- Thermal Analysis: Monitors nucleation temperatures and kinetics under controlled cooling conditions

These methodologies provide the experimental data necessary to validate theoretical models and refine our understanding of how interfacial energy and contact angle govern nucleation behavior across different material systems.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Materials and Their Applications in Nucleation Studies

| Reagent/Technique | Primary Function | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Zirconium inoculants | Potent nucleating substrate | Grain refinement in magnesium alloys [22] |

| Al-Ti-B master alloys | Heterogeneous nucleation catalyst | Aluminum alloy grain refinement [22] |

| Static Magnetic Field (SMF) | Interface energy modification | Altering crystallographic matching in Al/Al₂O₃ systems [23] |

| Checkerboard substrates | Model heterogeneous surfaces | Studying nucleation on chemically patterned surfaces [21] |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Atomic-scale simulation | Probing nucleation mechanisms and kinetics [21] |

| Jumpy Forward Flux Sampling | Enhanced rare event sampling | Calculating nucleation rates and pathways [21] |

The comparative analysis of homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation mechanisms reveals the profound influence of interfacial energy and contact angle on phase transition kinetics. Classical nucleation theory, despite its simplifying assumptions, provides a robust framework for predicting nucleation behavior across diverse systems, from metallic alloys to pharmaceutical compounds [20] [21]. The potency factor concept successfully captures how substrate properties reduce nucleation barriers through geometric relationships governed by contact angle.

Recent experimental and computational investigations continue to validate and refine our understanding of these fundamental relationships. Studies on chemically heterogeneous surfaces demonstrate the surprising resilience of CNT, with nucleation maintaining fixed contact angles through pinning mechanisms [21]. Meanwhile, emerging techniques for manipulating interfacial interactions, such as magnetic field application [23], offer new pathways for controlling nucleation outcomes in advanced materials and therapeutic products.

As nucleation science advances, the integration of computational prediction with experimental validation will enable more precise control of phase transitions across applications. The continuing relevance of classical nucleation theory lies in its ability to distill complex interfacial phenomena into quantifiable parameters that guide material design and process optimization in fields ranging from metallurgy to pharmaceutical development.

Visual Appendix

Figure 1: Research Framework: Interfacial Energy in Nucleation Studies. This diagram illustrates the conceptual relationships between homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation theories, their experimental validation across different material systems, and practical applications in materials processing and pharmaceutical development.

Control and Application: Strategies for Directing Nucleation in Pharmaceutical and Material Systems

Engineered Interfaces and Functionalized Surfaces as Heteronucleants

The controlled formation of crystalline solids is a critical process across numerous scientific and industrial domains, from pharmaceutical development to atmospheric science. Within this landscape, the distinction between homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation pathways represents a fundamental divide in crystallization outcomes. Homogeneous nucleation occurs spontaneously from a pure solution when molecules or atoms randomly assemble into stable clusters that can grow into crystals. In contrast, heterogeneous nucleation occurs on pre-existing surfaces or interfaces, which significantly lowers the energy barrier to crystal formation. This comparative analysis examines how engineered interfaces and functionalized surfaces function as heteronucleants, objectively evaluating their performance against homogeneous nucleation and other alternatives across multiple parameters including induction time, crystal quality, polymorphism control, and process reliability.

The pivotal role of interfaces in crystallization processes cannot be overstated. As Artusio highlights, "Interfaces are ubiquitous in nature and are involved in any physico-chemical process. Crystallizing a protein implies the formation of a new interface between the growing crystalline material and the liquid solution" [26]. This fundamental understanding has driven the strategic development of engineered heteronucleants that actively control crystallization initiation. The core thermodynamic principle underlying their function lies in their ability to reduce the activation energy required for nucleus formation. By providing surfaces with complementary chemical functionality, heteronucleants facilitate molecular organization, thereby accelerating crystallization onset and improving process predictability [27].

Theoretical Framework: Homogeneous versus Heterogeneous Nucleation

Classical Nucleation Theory and Energy Barriers

Classical Nucleation Theory provides the foundational framework for understanding the energetic differences between homogeneous and heterogeneous pathways. According to CNT, the formation of stable crystal nuclei requires surpassing a critical free energy barrier, which is significantly lower in heterogeneous systems due to the reduced interfacial energy when nuclei form on compatible surfaces [26]. The nucleation rate is profoundly influenced by this energy barrier, with heterogeneous nucleation occurring more readily at lower supersaturation levels compared to homogeneous nucleation [26].

The competitive interaction between these pathways has been demonstrated across diverse systems. In atmospheric science, prior heterogeneous ice nucleation events on mineral dust particles can deplete ice-nucleating particles from cloud-forming altitudes, subsequently enabling homogeneous freezing at the time of observations [2]. Similarly, in particulate removal technology, competitive effects between heterogeneous and homogeneous nucleation occur during water vapor condensation on particle surfaces, with the dominant pathway determined by environmental conditions including temperature and vapor concentration [3].

Phase Behavior and Nucleation Zones

The phase diagram for crystalline materials delineates distinct zones governing nucleation behavior, as illustrated in Figure 1. The metastable zone represents the region between solubility and supersolubility curves where crystal growth is thermodynamically favorable but nucleation is kinetically unfavorable [26]. A key distinction between nucleation pathways is that the presence of a heteronucleant expands the nucleation zone on the phase diagram, enabling nucleation at lower supersaturation levels compared to homogeneous systems [26].

Table 1: Phase Diagram Zones and Nucleation Characteristics

| Zone | Supersaturation Relation | Homogeneous Nucleation | Heterogeneous Nucleation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Undersaturated | Below solubility curve | Not possible | Not possible |

| Metastable | Between solubility and supersolubility curves | Kinetically unfavorable | Possible with efficient heteronucleants |

| Labile | Above supersolubility curve | Spontaneous but unpredictable | Controlled and reproducible |

| Precipitation | Very high supersaturation | Amorphous aggregates dominate | Can still yield crystals with optimized surfaces |

The strategic advantage of engineered heteronucleants lies in their ability to induce crystallization within the metastable zone, where homogeneous nucleation is improbable. This capability enables better control over crystal attributes including size distribution, polymorphic form, and morphology [26].

Engineered Heteronucleants: Materials and Functionalization Strategies

Polymer-Based Heteronucleants

Polymer-induced heteronucleation has emerged as a powerful approach for controlling crystallization outcomes. Research demonstrates that polymers functionalized with tailor-made additives can dramatically accelerate nucleation kinetics. In one compelling study, polymers incorporating N-hydroxyphenyl methacrylamide – a structural mimic of acetaminophen – reduced crystallization induction time from >6000 minutes (without polymer) to just 151 minutes with a 10 mol% functionalized polymer [27]. Similarly, p-acetamidostyrene-functionalized polymers decreased induction time to approximately one-hundredth of the control value [27].

The mechanism involves functional group interactions at the polymer-crystal interface that stabilize subcritical nuclei or facilitate molecular organization into critical nuclei. Notably, the same chemical functionality that inhibits crystal growth when soluble can promote nucleation when immobilized on insoluble polymers, demonstrating the context-dependent behavior of surface interactions [27].

Inorganic and Biomolecular Surfaces

Beyond synthetic polymers, inorganic surfaces and biomolecular interfaces can also direct nucleation processes. In atmospheric science, mineral dust particles such as SiOâ‚‚ serve as efficient ice-nucleating particles by providing surfaces for heterogeneous freezing of water vapor [3] [2]. Molecular dynamics simulations reveal that water molecules preferentially accumulate around specific atomic sites on SiOâ‚‚ surfaces, initiating condensation even at lower saturation levels [3].

In biological contexts, polyphenol-functionalized nanoarchitectures can form on cell surfaces through coordinated covalent and non-covalent interactions, creating engineered interfaces with specialized nucleation properties [28]. These systems demonstrate how surface chemistry and molecular recognition elements can be harnessed to control phase transitions.

Table 2: Heteronucleant Classes and Functional Characteristics

| Heteronucleant Class | Representative Materials | Functionalization Approach | Key Interactions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functionalized Polymers | Styrene copolymers with tailor-made additives | Copolymerization of functional monomers | Hydrogen bonding, electrostatic complementarity |

| Inorganic Particles | SiOâ‚‚, mineral dust | Surface chemistry modification | Coordination, surface wettability |

| Biomolecular Interfaces | Polyphenol-metal networks | Self-assembly through coordination | Metal-phenolic coordination, π-π stacking |

| Engineered Cell Surfaces | Polydopamine coatings | Oxidative polymerization | Covalent binding, Michael addition |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Induction Time and Process Efficiency

The most quantitatively demonstrated advantage of engineered heteronucleants is the dramatic reduction in nucleation induction time compared to homogeneous systems. Controlled studies with pharmaceutical compounds provide compelling experimental evidence:

Table 3: Induction Time Comparison for Acetaminophen Crystallization [27]

| Crystallization Condition | Average Induction Time (minutes) | Relative to Control |

|---|---|---|

| No polymer (homogeneous) | >6000 | 1× |

| Polystyrene (unfunctionalized) | 1100 | ~5.5× faster |

| 1 mol% N-hydroxyphenyl methacrylamide/styrene copolymer | 243 ± 7 | ~25× faster |

| 5 mol% N-hydroxyphenyl methacrylamide/styrene copolymer | 189 ± 10 | ~32× faster |

| 10 mol% N-hydroxyphenyl methacrylamide/styrene copolymer | 151 ± 8 | ~40× faster |

| 10 mol% p-acetamidostyrene/styrene copolymer | ~60 | ~100× faster |

This acceleration directly translates to significant process advantages, including reduced operational timelines, smaller equipment footprints, and improved manufacturing efficiency. In biotherapeutic production, where downstream purification can represent up to 70% of total manufacturing costs for monoclonal antibodies, controlled crystallization via heteronucleants offers a promising alternative to traditional chromatographic methods [26].

Crystal Quality and Polymorphism Control

Beyond kinetic advantages, heteronucleants provide superior control over crystal quality and polymorphic outcomes. The presence of tailored surfaces can influence which polymorphic form crystallizes preferentially – a critical consideration in pharmaceutical development where different polymorphs exhibit distinct bioavailability, stability, and processing characteristics [27].

Research demonstrates that while soluble additives dramatically change crystal morphology, the same chemical functionality incorporated into insoluble polymers accelerates nucleation without affecting crystal morphology [27]. This decoupling of nucleation kinetics from crystal growth morphology represents a significant advantage for manufacturing processes requiring both rapid initiation and specific crystal characteristics.

In protein crystallization, heteronucleants improve the reproducibility of experiments and uniformity of crystal attributes including size, habit, and form [26]. This control is particularly valuable for structural biology applications where diffraction-quality crystals are essential.

Process Reliability and Scalability

The stochastic nature of homogeneous nucleation presents significant challenges for process reliability and scale-up. Heteronucleants address this limitation by providing consistent nucleation sites, thereby reducing batch-to-batch variability. This reproducibility advantage extends across multiple domains:

In atmospheric science, the competition between homogeneous and heterogeneous freezing significantly impacts cirrus cloud properties, with prior heterogeneous nucleation events shaping subsequent homogeneous freezing conditions [2]. In industrial particulate removal, water vapor condensation growth processes rely on controlled heterogeneous nucleation on particle surfaces to enhance removal efficiency [3].

For continuous manufacturing platforms – an emerging trend in pharmaceutical production – engineered heteronucleants offer more predictable and stable nucleation behavior compared to homogeneous systems, facilitating process control and real-time optimization [26].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Polymer Heteronucleant Preparation and Evaluation

Protocol 1: Functionalized Copolymer Synthesis and Crystallization Screening [27]

Materials Preparation:

- Synthesize N-hydroxyphenyl methacrylamide or p-acetamidostyrene additives through nucleophilic substitution reactions

- Prepare binary copolymers with styrene using free radical polymerization at varying molar ratios (1, 5, 10 mol% additive)

- Confirm polymer insolubility in water by UV-vis absorbance spectroscopy

Crystallization Procedure:

- Prepare aqueous acetaminophen solutions at appropriate concentration

- Add polymer heteronucleants to solution under controlled stirring

- Conduct crystallizations in triplicate with eight replicates per condition

- Monitor crystal appearance optically every 15 minutes for solution-based studies or every 60 seconds for time-lapse photography

- Determine induction time as duration between supersaturation establishment and first crystal detection

- Characterize resulting crystals by Raman spectroscopy for polymorph identification and morphological analysis

Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Nucleation Processes

Protocol 2: MD Simulation of Heterogeneous Nucleation [3]

System Setup:

- Construct spherical SiOâ‚‚ particle (20 Ã… diameter) centered in simulation box

- Randomly distribute gas composition mimicking flue gas (Nâ‚‚, Oâ‚‚, COâ‚‚, Hâ‚‚O) with proportional relationships

- Employ NPT ensemble with temperature control (260-300 K range)

- Use established interatomic potentials (e.g., Tersoff parameterization for Si-O systems)

Simulation Parameters:

- Conduct 40 ns simulation runs to observe nucleation behavior

- Analyze Hâ‚‚O molecule accumulation around specific atomic sites on SiOâ‚‚ surface

- Quantify competition between homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation pathways

- Evaluate effects of temperature and Hâ‚‚O content on nucleation dominance

- Calculate interaction energies to determine nucleation preferences