High-Throughput Screening for Synthesizable Crystalline Materials: Accelerating Drug Discovery and Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of high-throughput screening (HTS) strategies specifically for identifying synthesizable crystalline materials, a critical step in efficient drug development.

High-Throughput Screening for Synthesizable Crystalline Materials: Accelerating Drug Discovery and Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of high-throughput screening (HTS) strategies specifically for identifying synthesizable crystalline materials, a critical step in efficient drug development. We explore the foundational principles of crystal structure prediction (CSP) for organic molecules and inorganic materials, detailing automated computational workflows and advanced force field applications. The scope extends to methodological applications of these HTS strategies in targeted drug discovery, illustrated with case studies from areas such as colorectal cancer research. The article also addresses key challenges in assay optimization and performance validation, offering practical troubleshooting guidance. Finally, we present comparative analyses of different screening and synthesizability prediction models, highlighting how the integration of HTS with AI-driven synthesizability classification is revolutionizing the identification of novel, synthetically accessible materials for biomedical applications.

The Foundation of Crystalline Material Discovery: Principles and Workflows

Defining High-Throughput Screening in Materials Science

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) is a powerful methodology that enables the rapid testing of thousands to millions of chemical, biological, or material samples in an automated, parallelized manner. In the context of materials science, it accelerates the discovery and optimization of novel materials by combining advanced computational predictions with automated experimental validation, systematically navigating vast compositional and structural landscapes that would be prohibitive to explore through traditional one-at-a-time experimentation [1]. This approach is fundamentally transforming the field, moving it from sequential, intuition-driven research to a data-rich, accelerated paradigm.

Core Principles and Workflow of HTS

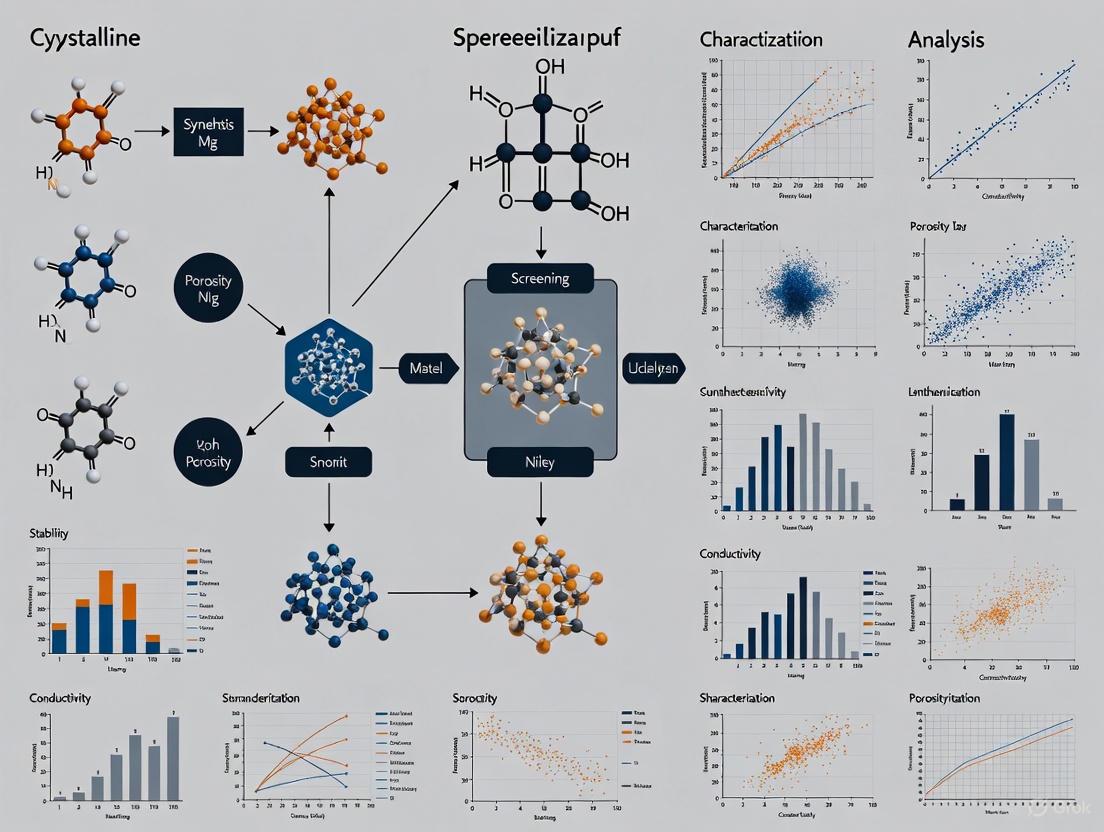

The efficacy of HTS in materials discovery hinges on a structured workflow that integrates automation, robust data analysis, and iterative learning. A universal HTS workflow can be deconstructed into several key stages, as illustrated below.

Defining the Objective and Feature Space The process initiates with a clear scientific objective, typically categorized as either optimization (e.g., enhancing a specific property like catalytic activity) or exploration (mapping a structure-property relationship to build a predictive model) [2]. Subsequently, relevant material descriptors—both intrinsic (e.g., composition, architecture, molecular weight) and extrinsic (e.g., synthesis conditions, temperature)—are selected. The chosen features are bounded and discretized to define the high-dimensional design space for the study [2].

Library Generation and Screening A representative subset of this design space is then generated through library synthesis. This can be a computational library, built from existing material databases, or an experimental library, created using automated synthesis robots and liquid handlers [2]. The library members are then subjected to high-throughput characterization using automated assays to rapidly collect data on the properties of interest [2].

Data Analysis and Active Learning The resulting large datasets are analyzed using statistical methods and machine learning (ML). Crucially, the output of this stage can inform the initial feature selection and library design through an active learning feedback loop, strategically guiding subsequent experiments toward the most promising regions of the design space and dramatically improving efficiency [3] [2].

Application Notes: Exemplary HTS in Action

Protocol for the Discovery of Bimetallic Catalysts

This protocol demonstrates a tightly integrated computational-experimental HTS pipeline for identifying novel bimetallic catalysts to replace palladium (Pd) in hydrogen peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) synthesis [4].

Step 1: High-Throughput Computational Screening

- Library Construction: A computational library of 4350 candidate bimetallic alloy structures was generated from 30 transition metals, considering ten different ordered crystal phases for each 50:50 binary combination [4].

- Thermodynamic Stability Screening: The formation energy (∆Ef) of each phase was calculated using first-principles Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations. Structures with ∆Ef < 0.1 eV were considered thermodynamically viable, filtering the list to 249 alloys [4].

- Electronic Structure Descriptor Screening: The electronic Density of States (DOS) pattern projected onto the close-packed surface of each alloy was calculated. The similarity to the DOS pattern of the reference Pd(111) surface was quantified using a defined metric (∆DOS). Alloys with low ∆DOS values were considered promising candidates, as similar electronic structures suggest comparable catalytic properties [4].

Step 2: Experimental Validation of Hits

- Synthesis: The top eight candidate alloys identified computationally were synthesized experimentally [4].

- Performance Testing: The catalytic performance of the synthesized candidates was evaluated for Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ direct synthesis. Four of the eight candidates exhibited performance comparable to Pd, validating the computational screening approach. Notably, a previously unreported Pd-free catalyst, Ni₆â‚Pt₃₉, was discovered, which outperformed the prototypical Pd catalyst and showed a 9.5-fold enhancement in cost-normalized productivity [4].

Protocol for Screening Van Der Waals Dielectrics

This protocol highlights the use of HTS computations combined with machine learning to identify novel van der Waals (vdW) dielectrics for two-dimensional nanoelectronics [3].

Step 1: Database Screening and High-Throughput Calculations

- Initial Filtering: Starting with over 126,000 materials from the Materials Project database, a topology-scaling algorithm was used to identify low-dimensional vdW materials. Screening criteria included a bandgap >1.0 eV and the exclusion of transition metals, yielding 452 0D, 113 1D, and 351 2D vdW candidates [3].

- Property Calculation: High-throughput DFT calculations were performed on the filtered candidates to obtain bandgaps and dielectric constants (ε) along the vdW direction. This process yielded data for 189 0D, 81 1D, and 252 2D vdW materials [3].

Step 2: Machine Learning Classification

- Model Development: A two-step machine learning classifier was developed using seven feature descriptors to predict promising dielectrics based on bandgap and dielectric constant [3].

- Active Learning: The ML model was implemented within an active learning framework, which successfully identified an additional 49 promising vdW dielectric candidates that were not part of the initial high-throughput calculation set [3].

Quantitative Outcomes of HTS Campaigns

The following table summarizes the scale and success rates of the HTS campaigns described in the protocols above, illustrating the quantitative power of this approach.

Table 1: Quantitative Outcomes of Exemplary HTS Studies in Materials Discovery

| Study Focus | Initial Library Size | Screened Candidates | Validated Hits | Key Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bimetallic Catalysts [4] | 4,350 alloy structures | 8 candidates synthesized | 4 catalysts with Pd-like performance | Ni₆â‚Pt₃₉: 9.5x cost-normalized productivity vs. Pd |

| vdW Dielectrics [3] | >126,000 database entries | 522 low-dimensional materials | 9 highly promising + 49 ML-identified dielectrics | Suitable for MoSâ‚‚-based FETs (Band offset >1 eV) |

| Porous Organic Cages [5] | 366 imine reactions | 366 reactions analyzed | Multiple new cages discovered | 350-fold reduction in data analysis time |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful HTS implementation relies on a suite of specialized reagents, materials, and equipment. The following table details key components used in the featured experiments.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for HTS in Materials Science

| Item Name | Function/Application | Example Usage in Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| His-SIRT7 Recombinant Protein | Enzymatic target for inhibitor screening assays. | Used in a fluorescence-based protocol for high-throughput screening of SIRT7 inhibitors [6]. |

| Fluorescent Peptide Substrates | Enable measurement of enzyme activity via changes in luminescent signals. | Employed to evaluate SIRT7 enzymatic activity in a microplate-based HTS protocol [6]. |

| Imine-based Molecular Precursors | Building blocks for dynamic covalent chemistry (DCC) in supramolecular material synthesis. | Aldehydes and amines were used in a combinatorial screen of 366 reactions to discover Porous Organic Cages [5]. |

| Cryopreserved PBMCs | Biologically relevant cell model for immunomodulatory screening; allows for longitudinal studies. | Used in a multiplexed HTS workflow to discover novel immunomodulators and vaccine adjuvants [7]. |

| AlphaLISA Kits | Homogeneous, no-wash assay for high-sensitivity quantification of cytokines and biomarkers. | Used to rapidly measure secretion levels of TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-10 from stimulated immune cells in HTS [7]. |

| Automated Liquid Handlers | Robotics for precise, nanoliter-scale dispensing of liquids into multi-well plates. | Essential for library preparation, reagent dispensing, and assay execution across all HTS protocols [1] [5]. |

| 5-Bromophthalide | 5-Bromophthalide|CAS 64169-34-2|High-Purity Reagent | |

| 6-Keto-PGE1 | 6-ketoprostaglandin E1 | Stable PGE1 Metabolite | RUO | 6-ketoprostaglandin E1 is a stable PGE1 metabolite for vascular & renal research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Integrated Computational-Experimental HTS Workflow

The most advanced HTS frameworks in materials science seamlessly blend computational and experimental elements. The diagram below synthesizes this integrated approach, showing how data flows from initial database mining to final material validation.

The Critical Challenge of Synthesizability in Material Discovery

The discovery of new inorganic materials is a central goal of solid-state chemistry and can usher in enormous scientific and technological advancements. While computational methods now generate millions of candidate material structures, a significant bottleneck persists: the majority of these computationally predicted materials are impractical to synthesize in the laboratory. The intricate nature of materials synthesis, governed by kinetic, thermodynamic, and experimental factors, often leads to cost-inefficient failures of materials design. This challenge is particularly acute in high-throughput screening of synthesizable crystalline materials, where distinguishing truly synthesizable candidates from merely computationally stable structures remains a critical hurdle. This Application Note addresses the synthesizability challenge by presenting quantitative assessment frameworks, detailed experimental protocols, and practical toolkits to bridge the gap between computational prediction and experimental realization.

Quantitative Frameworks for Synthesizability Assessment

Comparative Analysis of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Methodologies

| Method | Underlying Principle | Reported Accuracy | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamic Stability (E$_\text{hull}$) | Energy above convex hull [8] | 74.1% [9] | Strong theoretical foundation; Widely implemented | Neglects kinetic factors and synthesis conditions |

| Network Analysis | Dynamics of materials stability network [8] | Not explicitly quantified | Encodes historical discovery patterns; Captures circumstantial factors | Relies on evolutionary network growth patterns |

| Positive-Unlabeled Learning | Semi-supervised learning from positive and unlabeled data [10] | >75-87.9% for various material systems [9] | Addresses lack of negative examples in literature | Difficult to estimate false positives |

| Crystal Synthesis LLM | Fine-tuned large language models on material representations [9] | 98.6% [9] | State-of-the-art accuracy; Predicts methods and precursors | Requires extensive dataset curation |

| Composite ML Model | Integration of composition and structure descriptors [11] | Validated by 7/16 successful syntheses [11] | Combines complementary signals from composition and structure | Complex training procedure requiring significant computational resources |

Key Metrics and Performance Indicators

The energy above convex hull (E${\text{hull}}$) remains the most widely used thermodynamic stability metric, defined as the difference between the formation enthalpy of the material and the sum of the formation enthalpies of the combination of decomposition products that maximize the sum. However, this metric alone is insufficient for synthesizability prediction, achieving only 74.1% accuracy compared to 98.6% for advanced machine learning approaches [9]. The materials stability network analysis reveals that the network of stable materials follows a scale-free topology with degree distribution exponent γ = 2.6 ± 0.1 after the 1980s, within the range of other scale-free networks like the world-wide-web or collaboration networks [8]. High-throughput screening protocols employing electronic structure similarity have demonstrated experimental success, with four out of eight proposed bimetallic catalysts exhibiting catalytic properties comparable to palladium, including the discovery of a previously unreported Ni${61}$Pt$_{39}$ catalyst with a 9.5-fold enhancement in cost-normalized productivity [4].

Experimental Protocols for Synthesizability-Guided Discovery

Integrated Computational-Experimental Screening Protocol

Objective: Accelerated discovery of bimetallic catalysts through high-throughput screening. Primary Citation: High-throughput computational-experimental screening protocol for the discovery of bimetallic catalysts [4].

Methodology:

- Computational Screening:

- Consider 435 binary systems from 30 transition metals with 1:1 composition

- Evaluate 10 ordered crystal structures per system (total 4,350 structures)

- Calculate formation energy (ΔE$f$) using DFT and filter with threshold ΔE$f$ < 0.1 eV

- Compute density of states (DOS) patterns for thermodynamically screened alloys

- Quantify similarity to reference catalyst using ΔDOS${2-1}$ metric: [ \Delta DOS{2-1} = \left{ \int \left[ DOS2(E) - DOS1(E) \right]^2 g(E;\sigma) dE \right}^{1/2} ] where $g(E;\sigma)$ is a Gaussian distribution function centered at Fermi energy with σ = 7 eV

- Experimental Validation:

- Select candidates with lowest ΔDOS$_{2-1}$ values (<2.0)

- Synthesize proposed bimetallic catalysts

- Test catalytic performance for target reaction (H$2$O$2$ direct synthesis)

- Evaluate cost-normalized productivity relative to reference catalyst

Key Considerations: The protocol successfully identified Ni${61}$Pt${39}$, Au${51}$Pd${49}$, Pt${52}$Pd${48}$, and Pd${52}$Ni${48}$ as high-performing catalysts, demonstrating the utility of DOS similarity as a screening descriptor [4].

High-Throughput Encapsulated Nanodroplet Crystallization

Objective: Rapid exploration of co-crystallization space with minimal sample consumption. Primary Citation: High-throughput encapsulated nanodroplet screening for accelerated co-crystal discovery [12].

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation:

- Prepare stock solutions of substrate and co-former near solubility limit

- Select solvents (e.g., MeOH, DMF, MeNO$_2$, 1,4-dioxane) based on preliminary solubility testing

ENaCt Experimental Setup:

- Dispense 200 nL of encapsulation oils across 96-well glass plates

- Add 150 nL of test solution containing substrate and co-former

- Explore multiple substrate/co-former ratios (2:1, 1:1, 1:2)

- Seal plates with glass cover slips and incubate for 14 days

Analysis and Characterization:

- Inspect experiments by cross-polarized microscopy

- Characterize suitable crystals by single-crystal X-ray diffraction

- Identify new co-crystal forms through comparative unit cell analysis

Key Considerations: This approach enabled screening of 18 binary combinations through 3,456 individual experiments, identifying 10 novel binary co-crystal structures while consuming only micrograms of material per experiment [12].

Synthesizability-Guided Pipeline with Integrated Scoring

Objective: Prioritization of computationally predicted structures for experimental synthesis. Primary Citation: A Synthesizability-Guided Pipeline for Materials Discovery [11].

Methodology:

- Data Curation:

- Extract structures from Materials Project, GNoME, and Alexandria databases

- Label compositions as synthesizable (y=1) if any polymorph exists in experimental databases

- Label as unsynthesizable (y=0) if all polymorphs are theoretical

Model Architecture:

- Compositional encoder: Fine-tuned MTEncoder transformer

- Structural encoder: Graph neural network fine-tuned from JMP model

- Ensemble method: Rank-average fusion of composition and structure predictions

- Training: Minimize binary cross-entropy with early stopping on validation AUPRC

Synthesis Planning:

- Apply Retro-Rank-In for precursor suggestion

- Use SyntMTE to predict calcination temperatures

- Balance reactions and compute precursor quantities

Key Considerations: This pipeline successfully identified synthesizable candidates from over 4.4 million computational structures, with experimental validation achieving 7 successful syntheses out of 16 targets within three days [11].

Diagram 1: Synthesizability prediction workflow (76 characters)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Synthesizability Screening

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Example | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Encapsulation Oils | Mediate rate of sample concentration via evaporation/diffusion | ENaCt co-crystal screening [12] | Inert, immiscible with solvent; 200 nL volumes in 96-well format |

| Solid-State Precursors | Source of constituent elements for target material | Solid-state synthesis of ternary oxides [10] | Purity, particle size, and availability critical for reproducibility |

| DFT-Calculated Reference Data | Benchmark for thermodynamic stability and electronic properties | High-throughput screening of bimetallic catalysts [4] | Requires consistent computational parameters across structures |

| Building Block Libraries | Commercially available compounds for synthesis planning | Computer-Aided Synthesis Planning (CASP) [13] | Size and diversity of library directly impacts synthesizability rates |

| Text-Mined Synthesis Data | Training data for synthesizability prediction models | Positive-unlabeled learning for ternary oxides [10] | Quality and accuracy of extraction significantly impacts model performance |

| Cafenstrole | Cafenstrole | Herbicide for Plant Science Research | Cafenstrole is a selective herbicide for plant biology & agrochemical research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Iganidipine | Iganidipine | High-Purity Calcium Channel Blocker | Iganidipine is a dual L-/T-type calcium channel blocker for cardiovascular research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

Workflow Integration and Decision Pathways

Diagram 2: High-throughput experimentation cycle (53 characters)

The integration of synthesizability prediction into high-throughput screening workflows represents a paradigm shift in materials discovery. The workflow begins with computational candidate generation, where millions of structures are evaluated using integrated compositional and structural synthesizability models [11]. These models employ a rank-average ensemble method to prioritize candidates:

[ \mathrm{RankAvg}(i) = \frac{1}{2N}\sum{m\in{c,s}}\left(1+\sum{j=1}^{N}\mathbf{1}!\big[s{m}(j) < s{m}(i)\big]\right) ]

where $s_{m}(i)$ represents the synthesizability probability from composition ($c$) and structure ($s$) models for candidate $i$ [11]. High-priority candidates advance to synthesis planning, where precursor selection and reaction conditions are predicted using literature-mined data [11] [10]. High-throughput experimentation then enables rapid validation, with ENaCt methods allowing thousands of experiments with minimal material consumption [12]. The critical feedback loop refines synthesizability models based on experimental outcomes, continuously improving prediction accuracy and accelerating the discovery of novel, synthesizable materials.

Automated Workflows for Crystal Structure Prediction (CSP)

The high-throughput screening of synthesizable crystalline materials represents a paradigm shift in the discovery of new pharmaceuticals, organic electronics, and advanced materials. Automated Crystal Structure Prediction (CSP) workflows have emerged as critical tools that leverage computational modeling, artificial intelligence, and advanced sampling algorithms to systematically explore crystal energy landscapes in silico before laboratory synthesis [14]. These workflows address the fundamental challenge of crystal polymorphism, which can significantly modify material properties yet remains time-consuming and expensive to characterize experimentally [15]. The integration of automation across multiple computational pipelines—from molecular analysis and force field parameterization to structure generation and energy ranking—enables researchers to identify potential risks and opportunities in development pipelines with unprecedented speed and scale [16]. This application note details the core methodologies, protocols, and reagent solutions powering the next generation of high-throughput CSP, providing researchers with practical frameworks for implementation within diverse materials research contexts.

Core Methodologies and Quantitative Comparison

Tabular Comparison of Automated CSP Approaches

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Representative CSP Workflows

| Workflow / Software | Target Material Class | Primary Methodology | Sampling/Search Algorithm | Reported Performance Metrics | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HTOCSP [14] [15] | Organic Molecules | Force Field-based CSP | Population-based Sampling | Systematic screening of 100 molecules; benchmarked with different FFs | Open-source; automated from SMILES input; supports GAFF/OpenFF |

| CrySPAI [17] | Inorganic Materials | AI-DFT Hybrid | Evolutionary Optimization Algorithm (EOA) | Parallel procedures for 7 crystal systems; N~trial~ = 64 per generation | Broad applicability; combines AI speed with DFT accuracy |

| PXRDGen [18] | Inorganic Materials | Generative AI + Diffraction | Diffusion/Flow-based Generation | 82% match rate (1-sample); 96% (20-samples) on MP-20 dataset | End-to-end from PXRD; atomic-level accuracy in seconds |

| AutoMat [19] | 2D Materials | Experimental Image Processing | Agentic Tool Use + Physics Retrieval | Projected RMSD 0.11±0.03 Å; Energy MAE <350 meV/atom | Converts STEM images to CIF files; bridges microscopy & simulation |

| CAMD [20] | Inorganic Materials | Active Learning + DFT | Autonomous Simulation Agents | 96,640 discovered structures; 894 within 1 meV/atom of convex hull | Targets thermodynamically stable structures via iterative agent |

Table 2: Force Field and Energy Calculation Methods in CSP

| Method Category | Specific Methods | Supported Elements | Accuracy Considerations | Implementation in CSP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Force Fields | GAFF (General Amber FF) [14] [15], SMIRNOFF (OpenFF) [14] [15] | C, H, O, N, S, P, F, Cl, Br, I (GAFF); + alkali metals (OpenFF) | Fitted for standard conditions; may require retraining for specific systems | Default for initial sampling; balance of speed and accuracy |

| Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFFs) | ANI [14] [15], MACE [14] [15], MatterSim [19] | Varies by training data | Approach DFT accuracy; may struggle with far-from-equilibrium structures | Post-energy re-ranking on pre-optimized crystals |

| Ab Initio Methods | Density Functional Theory (DFT) [17] [20] | Full periodic table | High accuracy but computationally intensive; functional-dependent | Gold-standard validation; used in hybrid AI-DFT workflows |

Workflow Architecture Diagrams

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Organic CSP with HTOCSP

Application Context: Virtual polymorph screening for pharmaceutical development or organic electronic materials.

Workflow Overview: This protocol utilizes the HTOCSP package to automatically predict crystal structures for small organic molecules from SMILES strings, integrating molecular analysis, force field generation, and population-based sampling [14] [15].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Molecular Input and Analysis

- Input Preparation: Provide molecular structure as SMILES string. For multicomponent systems (co-crystals, salts, hydrates), supply separate SMILES for each component.

- 3D Conversion: HTOCSP utilizes RDKit to convert SMILES to 3D molecular coordinates [14] [15].

- Conformational Analysis: Flexible dihedral angles within the input molecule are automatically identified for subsequent sampling.

Force Field Parameterization

- Selection: Choose between GAFF or SMIRNOFF (OpenFF) force fields based on molecular composition [14] [15].

- Charge Calculation: Compute atomic partial charges using supported schemes (Gasteiger, MMFF94, or AM1-BCC) via AMBERTOOLS.

- Output: Force field parameters are saved as XML files following OpenFF standards, with optional topology files for different simulation codes.

Crystal Structure Generation

- Space Group Selection: Specify target space groups (typically common organic space groups) or use default settings.

- Symmetric Generation: Utilize PyXtal to generate trial crystal structures by placing molecules at general Wyckoff positions within the specified space groups [14].

- Constraints: Optionally incorporate experimental data (e.g., unit cell parameters from PXRD) to constrain the search space.

Structure Optimization and Ranking

- Initial Optimization: Perform symmetry-constrained geometry optimization using CHARMM (default for speed) or GULP to refine cell parameters and atomic coordinates without breaking symmetry [14] [15].

- Energy Evaluation: Calculate lattice energy for each optimized structure.

- ML Refinement (Optional): Re-rank low-energy structures using machine learning force fields (ANI, MACE) for improved energy ranking, noting this is applied to pre-optimized structures only [14] [15].

Output Analysis

- Structure Ranking: Final output is a ranked list of plausible crystal packings based on computed lattice energies.

- Visualization and Clustering: Analyze results for structural diversity, identifying distinct polymorph families and their relative stability.

Protocol 2: AI-Driven CSP from Powder Diffraction Data with PXRDGen

Application Context: Rapid crystal structure determination of inorganic materials from experimental PXRD patterns.

Workflow Overview: This protocol employs the PXRDGen neural network to solve and refine crystal structures directly from PXRD data, integrating contrastive learning, generative modeling, and automated Rietveld refinement [18].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Data Preparation and Preprocessing

- PXRD Input: Provide experimental PXRD pattern as digital data (XYE, CSV) or image (PNG, JPG, PDF). For images, PXRDGen includes AI-powered digitization.

- Chemical Information: Input chemical formula of the target material.

- Optional Unit Cell: Provide unit cell parameters from indexing software or allow complete determination by PXRDGen.

Contrastive Learning-Based Encoding

- Feature Extraction: PXRD pattern is encoded into a latent representation using a pre-trained XRD encoder (Transformer-based preferred for higher performance) [18].

- Alignment: The encoder utilizes contrastive learning to align PXRD latent space with crystal structure space, ensuring diffraction features guide structure generation.

Conditional Crystal Structure Generation

- Generative Framework: The Crystal Structure Generation (CSG) module employs either diffusion or flow-based models conditioned on the PXRD features and chemical formula [18].

- Sampling: Generate multiple candidate structures (1-20 samples) to explore potential matches. The flow-based CSG module offers state-of-the-art match rate and speed.

Automated Rietveld Refinement

- Validation: Generated structures are automatically refined against the experimental PXRD data using an integrated Rietveld refinement module [18].

- Goodness-of-Fit: Evaluate using standard R-factors to quantify agreement between calculated and experimental patterns.

Output and Validation

- Final Structure: Output refined crystal structure in CIF format.

- Performance: On the MP-20 dataset, this protocol achieves 82% single-sample and 96% 20-sample matching rates for valid compounds, with RMSE approaching Rietveld refinement precision limits [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Software and Computational Tools for Automated CSP

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Application Context | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HTOCSP [14] [15] | Python Package | Automated organic CSP workflow | Virtual polymorph screening for organic molecules & pharmaceuticals | Open-source |

| RDKit [14] [15] | Cheminformatics Library | SMILES parsing, 3D conversion, molecular analysis | Molecular input handling in multiple CSP pipelines | Open-source |

| PyXtal [14] | Structure Generation Code | Symmetric crystal generation for 0D/1D/2D/3D systems | Generating initial trial structures within symmetry constraints | Open-source |

| CrySPAI [17] | AI Software Suite | Inorganic CSP via evolutionary algorithm & deep learning | Predicting stable inorganic crystal structures | Research publication |

| PXRDGen [18] | Neural Network | End-to-end structure determination from PXRD | Rapid crystal structure solving from powder diffraction data | Research publication |

| AutoMat [19] | Agentic Pipeline | Crystal structure reconstruction from STEM images | Converting microscopy images to simulation-ready CIF files | GitHub repository |

| Spotlight [21] | Python Package | Global optimization for Rietveld analysis | Automating initial parameter finding for refinement | Open-source |

| FlexCryst [22] | Software Suite | Machine learning-based CSP & analysis | Crystal energy calculation & structure comparison | Academic license |

| GAFF/OpenFF [14] [15] | Force Field Parameters | Classical energy calculation for organic molecules | Energy evaluation during structure sampling | Open-source |

| VASP [17] [20] | DFT Code | Ab initio energy & force calculation | High-accuracy validation in AI-DFT workflows | Commercial license |

| Sudan Red 7B | Sudan Red 7B | High-Purity Lipophilic Dye | Sudan Red 7B is a lysochrome dye for lipid research & industrial staining. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals | |

| Chalcone | Chalcone | High-Purity Research Compound | Chalcone: A versatile chemical scaffold for medicinal chemistry & biochemistry research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

The acceleration of materials discovery through high-throughput computational screening has created a critical bottleneck: the experimental validation of hypothetical materials. Traditional synthesizability proxies, such as charge-balancing and thermodynamic stability (e.g., energy above the convex hull, Ehull), are insufficient alone, as they ignore kinetic barriers, synthesis conditions, and technological constraints [10] [23]. Data-driven methods, particularly machine learning (ML), are now bridging this gap by learning the complex patterns underlying successful synthesis directly from experimental data. This document outlines key data-driven methodologies and detailed experimental protocols for predicting synthesizability, enabling more reliable screening of crystalline materials.

Quantitative Comparison of Data-Driven Approaches

Table 1: Comparison of Data-Driven Synthesizability Prediction Models

| Model Name | Core Approach | Input Data Type | Key Performance Metric | Reported Performance | Key Advantage(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SynthNN [23] | Deep Learning (Atom2Vec) | Chemical Composition | Precision | 7x higher precision than Ehull screening | Screens compositions without structural data; learns chemical principles like ionicity. |

| PU Learning (Chung et al.) [10] | Positive-Unlabeled Learning | Manually curated synthesis data (ternary oxides) | Number of predicted synthesizable compositions | 134/4312 hypothetical compositions predicted synthesizable | Directly uses reliable literature synthesis data; robust to lack of negative examples. |

| Crystal Synthesis LLM (CSLLM) [24] | Fine-Tuned Large Language Models | Text-represented crystal structure (Material String) | Accuracy | 98.6% accuracy on test set | Predicts synthesizability, synthesis method, and precursors; exceptional generalization. |

| Contrastive PU Learning (CPUL) [25] | Contrastive Learning + PU Learning | Crystal Graph Structure | True Positive Rate (TPR) | High TPR, short training time | Combines structural feature learning with PU learning for efficiency and accuracy. |

| SynCoTrain [26] | Dual-Classifier Co-training (ALIGNN & SchNet) | Crystal Structure (Graph) | Recall | High recall on oxide test sets | Mitigates model bias via co-training; effective for oxide crystals. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Solid-State Synthesizability Prediction via Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning

Application: Predicting the likelihood that a hypothetical ternary oxide can be synthesized via solid-state reaction [10].

Workflow Diagram:

Title: PU Learning Workflow for Synthesizability

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Data Curation

- Source: Extract ternary oxide entries with ICSD IDs from the Materials Project (MP) database [10].

- Labeling: Manually review corresponding scientific literature via ICSD, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. For each composition, label as:

- Positive (P): Solid-state synthesizable (if ≥1 record of successful solid-state synthesis exists).

- Negative (Non-Solid-State): Synthesized, but not via solid-state reaction.

- Data Collection: For positive entries, extract synthesis details (e.g., highest heating temperature, atmosphere, precursors) where available [10].

Feature Engineering

- Calculate standard compositional and structural features from the crystal structure (e.g., using matminer or pymatgen).

- Validation: Perform a sanity check by analyzing the relationship between Ehull and the synthesized labels to confirm its inadequacy as a sole predictor [10].

PU Learning Model Training

- Framework: Employ a PU learning framework (e.g., the bagging SVM approach by Mordelet and Vert) [10] [26].

- Training Set: Use the manually labeled positive (P) samples. Treat all hypothetical materials from the MP without confirmed synthesis records as unlabeled (U) data.

- Training: Iteratively train a classifier to distinguish positive samples from the unlabeled set, which contains both synthesizable and unsynthesizable materials.

Prediction & Validation

- Screening: Apply the trained model to a set of hypothetical ternary oxides (e.g., 4312 compositions) [10].

- Output: Generate a ranked list of compositions with high "synthesizability" scores.

- Validation: Propose the top-ranked candidates (e.g., 134 compositions) for targeted experimental validation [10].

Protocol: High-Throughput Synthesizability Screening using Crystal Synthesis LLM (CSLLM)

Application: Accurately predicting the synthesizability of arbitrary 3D crystal structures, their likely synthesis methods, and suitable precursors [24].

Workflow Diagram:

Title: CSLLM Screening Workflow

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Dataset Construction

- Positive Data: Select ~70,000 ordered, experimentally confirmed crystal structures from the ICSD. Apply filters (e.g., ≤40 atoms/unit cell, ≤7 elements) [24].

- Negative Data: Generate a pool of ~1.4 million theoretical structures from MP and other DFT databases. Use a pre-trained PU learning model to assign a Crystal-Likeness score (CLscore) to each. Select the 80,000 structures with the lowest CLscores (e.g., <0.1) as robust negative examples [24].

Create Material String Representation

- Develop a concise text representation ("Material String") for each crystal structure. The format should encapsulate: Space Group | Lattice Parameters (a, b, c, α, β, γ) | (Atomic Symbol-Wyckoff Site[Wyckoff Position Coordinates]) [24].

- This representation is more efficient for LLM processing than verbose CIF or POSCAR files.

Fine-Tune Specialized LLMs

- Use the balanced dataset of positive and negative Material Strings to fine-tune three separate LLMs:

- Synthesizability LLM: Classifies a structure as synthesizable or not.

- Method LLM: Predicts the probable synthesis method (e.g., solid-state vs. solution).

- Precursor LLM: Identifies suitable chemical precursors for synthesis.

- Use the balanced dataset of positive and negative Material Strings to fine-tune three separate LLMs:

Prediction & Analysis

- Input: Convert the candidate crystal structure into the Material String format.

- Screening: Feed the string into the fine-tuned CSLLM framework.

- Output: Obtain three key predictions: a binary synthesizability label (with high accuracy, e.g., 98.6%), the suggested synthesis method, and a list of potential precursors [24].

- Downstream Analysis: Integrate these predictions into high-throughput screening pipelines to filter generative model outputs or DFT candidate lists.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Digital & Data Resources for Synthesizability Prediction

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Synthesizability Research | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Project (MP) | Computational Database | Source of calculated crystal structures, formation energies (Ehull), and hypothetical materials for screening. | [10] [25] |

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) | Experimental Database | The primary source of confirmed, synthesizable crystal structures used as positive training examples. | [23] [24] |

| pymatgen | Python Library | Materials analysis; used for structure manipulation, feature extraction, and accessing MP data. | [10] [26] |

| Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning Algorithms | Machine Learning Method | Enables model training when only positive (synthesized) and unlabeled (hypothetical) data are available. | [10] [23] [26] |

| Crystal-Likeness Score (CLscore) | Predictive Metric | A score (0-1) estimating the synthesizability of a crystal structure; used to generate negative samples. | [24] [25] |

| Material String | Data Representation | A concise text representation of crystal structures for efficient processing by Large Language Models. | [24] |

| 7-Methylindole | 7-Methylindole | For Organic Synthesis & Research | High-purity 7-Methylindole for research. A key intermediate in organic synthesis & pharmaceutical studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| SIRT1 Activator 3 | SIRT1 Activator 3 | Sirtuin-1 Research Compound | SIRT1 Activator 3 is a potent sirtuin-1 activator for aging & metabolic disease research. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

Key Databases and Computational Tools for Exploratory Screening

The discovery and development of new crystalline materials, crucial for applications ranging from pharmaceuticals to renewable energy technologies, have been revolutionized by high-throughput computational screening. This approach leverages advanced algorithms and vast databases to efficiently explore the vast chemical space of synthesizable crystalline materials, significantly accelerating the materials discovery pipeline. By integrating computational predictions with experimental validation, researchers can identify promising candidate materials with targeted properties more rapidly and cost-effectively than through traditional methods alone. This article provides a detailed overview of the key databases, computational tools, and experimental protocols that constitute the modern researcher's toolkit for exploratory screening of crystalline materials, with a specific focus on applications within drug development and materials science.

Key Databases for Crystalline Materials Research

Table 1: Major Materials Databases for High-Throughput Screening

| Database Name | Primary Focus | Key Features | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Materials Project (MP) [27] | Inorganic crystalline materials | Extensive database of computed properties; supports alloy systems screening | Available via API; CC licensing |

| Crystallographic Open Database (COD) [28] | Organic & inorganic crystal structures | Curated collection of non-centrosymmetric structures for piezoelectric screening | Open access |

| CrystalDFT [28] | Organic piezoelectric crystals | DFT-predicted electromechanical properties; ~600 noncentrosymmetric structures | Available online |

| Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) [14] | Organic & metal-organic crystals | Experimentally determined structures; critical for organic CSP | Subscription-based |

| PubChem [14] [29] | Chemical molecules and their activities | Molecular structures and biological activities; integrates with HTS data | Open access |

Computational Tools and Generative Models

Generative Models for Crystal Structure Prediction

Advanced deep learning generative models have emerged as powerful tools for exploring the configuration space of crystalline materials. These models learn the underlying distribution of known crystal structures from databases and can generate novel, stable structures.

CrystalFlow is a flow-based generative model that addresses unique challenges in crystalline materials design. It combines Continuous Normalizing Flows (CNFs) and Conditional Flow Matching (CFM) with graph-based equivariant neural networks to simultaneously model lattice parameters, atomic coordinates, and atom types [30]. This architecture explicitly preserves the intrinsic periodic-E(3) symmetries of crystals (permutation, rotation, and periodic translation invariance), enabling data-efficient learning and high-quality sampling. During inference, random initial structures are sampled from simple prior distributions and evolved toward realistic crystal configurations through learned probability paths using numerical ODE solvers [30]. CrystalFlow achieves performance comparable to state-of-the-art models on established benchmarks while being approximately an order of magnitude more efficient than diffusion-based models in terms of integration steps [30].

Other notable approaches include:

- Crystal Diffusion Variational Autoencoder (CDVAE): Integrates diffusion processes with SE(3) equivariant message-passing neural networks [30]

- Symmetry-aware models (DiffCSP++, SymmCD, CrystalFormer): Incorporate space group symmetry as a critical inductive bias for modeling crystalline materials [30]

- Unified generative frameworks: Model molecules, crystals, and proteins within a single architecture [30]

High-Throughput Screening Workflows

Table 2: Computational Screening Tools and Software Packages

| Tool/Package | Application Domain | Methodology | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CrystalFlow [30] | General crystal structure prediction | Flow-based generative modeling | Nature Communications (2025) |

| HTOCSP [14] | Organic crystal structure prediction | Population-based sampling & force field optimization | Digital Discovery (2025) |

| PyXtal [14] | Crystal structure generation | Symmetry-aware structure generation | PyXtal package |

| CDD Vault [29] | Drug discovery data management | HTS data storage, mining, visualization | CDD platform |

| pymatgen-analysis-alloys [27] | Alloy systems screening | High-throughput analysis of tunable materials | Open-source Python package |

Diagram 1: High-throughput computational screening workflow for crystalline materials.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Organic Crystal Structure Prediction Using HTOCSP

The High-Throughput Organic Crystal Structure Prediction (HTOCSP) Python package enables automated prediction and screening of crystal packing for small organic molecules [14]. Below is the detailed protocol for implementing this workflow:

1. Molecular Analysis

- Input Preparation: Obtain molecular structures as SMILES strings from databases such as PubChem or CCDC [14].

- 3D Conversion: Utilize the RDKit library to convert SMILES strings into 3D molecular coordinates [14].

- Conformational Analysis: Identify flexible dihedral angles within the input molecule using RDKit's molecular analysis capabilities [14].

- Multi-component Systems: For cocrystals, salts, and hydrates, process each molecular component separately [14].

2. Force Field Generation

- Parameter Selection: Choose between two supported force field types:

- Charge Calculation: Compute atomic partial charges using AMBERTOOLS with schemes such as Gasteiger, MMFF94, or AM1-BCC [14].

- Parameter Export: Save force field parameters as XML files according to OpenFF standards [14].

3. Symmetry-Adapted Structure Calculation

- Calculator Selection: Employ either GULP or CHARMM for symmetry-constrained geometry optimization [14].

- Symmetry Preservation: Maintain space group symmetry throughout optimization of cell parameters and molecular coordinates within the asymmetric unit [14].

- Machine Learning Force Fields: Optionally use ANI or MACE for post-energy re-ranking of pre-optimized crystals [14].

4. Crystal Structure Generation

- Space Group Selection: Generate trial structures across common space groups using PyXtal [14].

- Wyckoff Position Assignment: Place molecules at general or special Wyckoff positions based on molecular symmetry compatibility [14].

- Constraint Application: Incorporate experimental data (e.g., pre-determined cell parameters) when available [14].

Protocol: High-Throughput Screening of Organic Piezoelectrics

This protocol outlines a computational methodology for screening organic molecular crystals with piezoelectric properties [28]:

1. Database Curation

- Source noncentrosymmetric organic structures from the Crystallographic Open Database (COD) [28].

- Apply screening criteria to select space groups lacking inversion symmetry (groups 1, 3-9, 16-46, 75-82, 89-122, 143-146, 149-161, 168-174, 177-190, 195-199, 207-220) [28].

- Set computational limits (e.g., ≤50 atoms per unit cell) to ensure feasible calculation times [28].

2. High-Throughput DFT Workflow

- File Preparation: Automate creation of input files for DFT calculations (VASP recommended) [28].

- Calculation Management: Implement job submission and monitoring scripts for parallel processing [28].

- Output Analysis: Develop sequential scripts for automated extraction of piezoelectric tensors and electromechanical properties [28].

3. Validation and Benchmarking

- Compare calculated piezoelectric constants with experimental values for reference systems (e.g., γ-glycine, L-histidine) [28].

- Account for methodological variations in experimental measurements (Berlincourt method, resonance-based measurements, piezoresponse force microscopy) [28].

- Establish statistical confidence intervals for computational predictions [28].

Diagram 2: Organic crystal structure prediction workflow using HTOCSP.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Computational and Experimental Reagents for Crystalline Materials Screening

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Function/Purpose | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit [14] | Software library | Cheminformatics and molecular analysis | SMILES to 3D structure conversion; dihedral angle analysis |

| AMBERTOOLS [14] | Software suite | Molecular mechanics and dynamics | Force field parameter generation; partial charge calculation |

| PyXtal [14] | Python package | Crystal structure generation | Symmetry-aware generation of trial crystal structures |

| pymatgen-analysis-alloys [27] | Python package | Alloy system analysis | High-throughput screening of tunable alloy properties |

| GULP/CHARMM [14] | Simulation software | Symmetry-adapted geometry optimization | Crystal structure relaxation preserving space group symmetry |

| ANI/MACE [14] | Machine learning force fields | Accurate energy ranking | Post-processing optimization of generated crystal structures |

| VASP [28] | DFT software | Electronic structure calculations | Piezoelectric property prediction; high-throughput screening |

| CDD Vault [29] | Data management platform | HTS data storage and analysis | Secure data sharing; collaborative model development |

| H-Gly-Gly-Met-OH | H-Gly-Gly-Met-OH, MF:C9H17N3O4S, MW:263.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Laminarihexaose | Laminarihexaose|β-1,3-Glucan Oligosaccharide|RUO | Bench Chemicals |

The integration of advanced computational screening tools with comprehensive materials databases has created a powerful ecosystem for accelerating crystalline materials discovery. The protocols and tools outlined in this article provide researchers with a structured approach to navigate the complex landscape of crystal structure prediction and property optimization. As generative models continue to evolve and high-throughput methodologies become more sophisticated, the pace of materials discovery for pharmaceutical and energy applications is expected to accelerate significantly. Future developments will likely focus on improving the accuracy of machine learning force fields, enhancing the integration of computational and experimental workflows, and expanding the scope of screening to more complex multi-component crystalline systems.

Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Biomedical Research

The high-throughput discovery of new functional materials, particularly in the pharmaceutical and organic electronics industries, is often gated by the ability to predict stable, synthesizable crystal structures for target molecules. Crystal structure prediction (CSP) for organic molecules remains a significant challenge due to the weak and diverse intermolecular interactions that can lead to polymorphism, where a single molecule can adopt multiple stable crystalline forms [14]. The capability to computationally screen for likely organic crystal formations before laboratory synthesis saves considerable time and expense [14]. This Application Note details a comprehensive computational workflow that transforms a simple SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) string into a predicted crystalline material, framed within the paradigm of high-throughput screening for synthesizable materials. We present integrated protocols leveraging both traditional force field methods and emerging machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) approaches to enhance the speed and reliability of CSP.

The Integrated CSP Workflow: From 1D Representation to 3D Crystal

The overarching workflow for crystal generation involves several sequential stages, from molecular definition to final structure ranking. The diagram below outlines the logical flow and key decision points in this process.

Figure 1: The Integrated CSP Workflow. This flowchart illustrates the primary pathway from a SMILES string to a final list of candidate crystal structures, highlighting the integration of traditional sampling with ML-accelerated prediction steps.

Workflow Component Analysis

The workflow depicted in Figure 1 consists of several critical stages, each with distinct methodologies and tools:

- Molecular Input and Analysis: The process initiates with a SMILES string, a line notation for representing molecular structures. Tools like the RDKit library are employed to convert this 1D representation into a 3D molecular model and analyze flexible dihedral angles for subsequent conformational sampling [14].

- Force Field Parameterization: Accurate description of intermolecular interactions is crucial. This stage involves assigning force field parameters, such as those from the General Amber Force Field (GAFF) or the more flexible SMIRNOFF (OpenFF), along with atomic partial charges [14].

- Structure Sampling and Generation: This is the core exploratory phase. Approaches range from traditional population-based sampling within common space groups, as implemented in the HTOCSP package and PyXtal, to modern ML-accelerated methods [14]. ML models can predict the most probable space groups and crystal densities, drastically narrowing the search space and improving efficiency [31].

- Structure Relaxation and Ranking: Generated candidate structures are relaxed to their local energy minima. This can be performed using symmetry-adapted classical force fields (e.g., via GULP or CHARMM), faster neural network potentials (NNPs), or more accurate but computationally expensive density functional theory (DFT) [14] [31]. The relaxed structures are then ranked by lattice energy or other stability metrics.

- Synthesizability Assessment: A critical final filter involves predicting the synthesizability of the predicted crystal structures. The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM) framework has demonstrated state-of-the-art accuracy (98.6%) in distinguishing synthesizable from non-synthesizable structures, significantly outperforming filters based solely on thermodynamic or kinetic stability [9].

Quantitative Performance of CSP Methodologies

The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of various CSP and synthesizability prediction methods as reported in recent literature.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of CSP and Synthesizability Prediction Methods

| Method / Model | Primary Function | Reported Performance | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| HTOCSP Workflow [14] | High-throughput crystal generation & sampling | Systematic benchmarking over 100 molecules | Open-source, automated pipeline for organic CSP |

| SPaDe-CSP [31] | ML-accelerated CSP for organics | 2x higher success rate vs. random CSP; 80% success for tested compounds | Uses space group & density predictors to narrow search |

| CSLLM Framework [9] | Synthesizability, method & precursor prediction | 98.6% synthesizability accuracy; >90% method classification | Bridges gap between theoretical structures & practical synthesis |

| CrystalFlow [30] | Generative model for crystals | Comparable to state-of-the-art on benchmarks; ~10x more efficient than diffusion models | Flow-based model enabling efficient conditional generation |

| Thermodynamic Stability [9] | Synthesizability screening (Energy above hull) | 74.1% accuracy | Directly assesses thermodynamic favorability |

| Kinetic Stability [9] | Synthesizability screening (Phonon spectrum) | 82.2% accuracy | Assesses dynamic stability of the lattice |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Traditional Force Field-Based CSP with HTOCSP

This protocol describes a standard workflow for organic CSP using the open-source HTOCSP package, which integrates several existing open-source tools [14].

Materials and Software Requirements:

- HTOCSP Python Package

- RDKit: For molecular analysis and SMILES conversion.

- AMBERTOOLS: For force field parameterization (GAFF/OpenFF).

- PyXtal: For symmetric crystal structure generation.

- GULP or CHARMM: For symmetry-constrained geometry optimization.

Procedure:

- Molecular Input and Preprocessing:

- Input the target molecule as a SMILES string.

- Use RDKit to generate a 3D molecular model and identify all flexible torsion angles for conformational sampling during crystal generation.

Force Field Generation:

- Use the

Force Field Makermodule of HTOCSP with AMBERTOOLS to assign parameters from GAFF or OpenFF. - Compute atomic partial charges using a scheme such as AM1-BCC. The resulting parameters are saved in an XML file following the OpenFF standard.

- Use the

Crystal Structure Generation:

- Use the PyXtal package to generate initial crystal packing models.

- Specify a list of common space groups for organic crystals (e.g., P2â‚/c, P-1, P2â‚2â‚2â‚). For each space group, PyXtal will place the molecular asymmetric unit(s) into the Wyckoff positions, generating multiple random packings.

Structure Relaxation and Ranking:

- Relax the generated crystal structures using a symmetry-constrained calculator (GULP or CHARMM). The lattice parameters and atomic coordinates within the asymmetric unit are optimized without breaking the crystal symmetry.

- Calculate the final lattice energy for each relaxed structure.

- Rank all candidates by their lattice energy to produce a shortlist of the most thermodynamically plausible structures.

Protocol 2: ML-Accelerated CSP with SPaDe-CSP and AI Tools

This protocol leverages modern machine learning to make the CSP workflow faster and more reliable, as demonstrated by the SPaDe-CSP workflow and other AI-driven tools [31] [32].

Materials and Software Requirements:

- SPaDe-CSP Workflow or equivalent ML models.

- LightGBM framework (for space group/density prediction).

- Molecular Fingerprints (e.g., MACCSKeys).

- Neural Network Potential (NNP) pre-trained on DFT data.

- AI-Driven HPLC/Digital Twin Systems (for related analytical optimization).

Procedure:

- ML-Based Search Space Narrowing:

- Instead of random crystal generation across all space groups, use trained ML models (e.g., LightGBM with molecular fingerprints) to predict the most probable space groups and the crystal density for the target molecule [31].

- Apply a probability threshold for space groups and a tolerance window for density to filter out unlikely candidates before the sampling stage.

Focused Crystal Generation and Relaxation:

- Generate crystal structures only within the ML-predicted space groups and density range.

- Perform structure relaxation using an efficient Neural Network Potential (NNP) instead of classical force fields or DFT. NNPs offer a favorable balance between speed and accuracy, as they are trained on DFT data [31].

Synthesizability and Precursor Prediction:

- Input the final relaxed structures into a specialized LLM like the Crystal Synthesis LLM (CSLLM) [9].

- Use the Synthesizability LLM to obtain a probability of synthesizability.

- For structures deemed synthesizable, use the Method LLM and Precursor LLM to suggest a viable synthetic route (e.g., solid-state or solution) and potential chemical precursors.

Analytical Method Prediction (Optional):

- For pharmaceutical applications, the final candidate's characterization can be accelerated by using AI tools to predict optimal analytical methods, such as HPLC conditions. Hybrid AI systems can use digital twins and mechanistic modeling to autonomously optimize chromatographic methods with minimal experimentation [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

The table below catalogs key computational tools and their functions in a high-throughput CSP pipeline.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Computational CSP

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in CSP Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit [14] | Open-Source Library | Converts SMILES to 3D model; analyzes molecular flexibility. |

| GAFF / OpenFF [14] | Force Field | Provides parameters for intermolecular and intramolecular interactions. |

| PyXtal [14] | Python Code | Generates random symmetric crystal structures for specified space groups. |

| GULP / CHARMM [14] | Simulation Code | Performs symmetry-constrained geometry optimization of crystal structures. |

| HTOCSP [14] | Integrated Package | Provides an automated, open-source pipeline for organic CSP. |

| CSLLM [9] | Large Language Model | Predicts crystal synthesizability, synthetic methods, and precursors. |

| SPaDe-CSP (LightGBM) [31] | Machine Learning Model | Predicts probable space groups and crystal density to focus the CSP search. |

| CrystalFlow [30] | Generative Model | A flow-based model for direct generation of crystalline materials. |

| ANI / MACE [14] | ML Force Field | Used for accurate energy re-ranking of pre-optimized structures. |

| Kobusin | Kobusin, CAS:36150-23-9, MF:C21H22O6, MW:370.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3-Chloro-L-tyrosine-13C6 | 3-Chloro-L-tyrosine-13C6, MF:C9H10ClNO3, MW:221.59 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow Integration and Data Analysis

The synergy between the components in the Scientist's Toolkit creates a powerful, multi-faceted pipeline. The emerging paradigm leverages ML at the front end to guide sampling and at the back end to validate synthesizability, encapsulating the traditional force-field-based sampling and relaxation core. This integrated approach directly addresses the broader thesis of high-throughput screening for synthesizable materials by ensuring that computational predictions are not only thermodynamically plausible but also experimentally actionable.

For the final analysis of results, particularly when dealing with large virtual screens, the principles of Quantitative High-Throughput Screening (qHTS) data analysis can be applied. This involves fitting model outputs (e.g., energies, synthesizability scores) to distributions to establish activity thresholds and confidence intervals, ensuring robust ranking and prioritization of candidate structures [33] [34]. The following diagram illustrates the data analysis and decision pathway post-structure generation.

Figure 2: Post-Generation Analysis and Candidate Prioritization Workflow. This chart outlines the key filtering and analysis steps applied to a pool of generated structures to identify the most promising candidates for synthesis.

The accurate prediction of crystalline materials, particularly in pharmaceutical and organic electronic applications, hinges on the precise modeling of intermolecular interactions. Force fields (FFs)—empirical mathematical functions that describe the potential energy of a system of particles—form the computational bedrock for these simulations. The development of new organic materials with targeted properties relies heavily on understanding and controlling these interactions within the crystal structure [35] [14]. Within high-throughput screening workflows for synthesizable crystalline materials, the selection of an appropriate force field is a critical first step that directly influences the reliability of the virtual screening results. This application note provides a detailed comparison of the General Amber Force Field (GAFF), the Open Force Field (OpenFF), and emerging Machine Learning Potentials (MLPs), offering structured protocols for their effective application in crystal structure prediction (CSP).

Key Force Fields for Organic Molecular Crystals

The General Amber Force Field (GAFF): GAFF is a widely used general force field designed for modeling small organic molecules, covering elements C, H, O, N, S, P, F, Cl, Br, and I [35] [36]. It is an atom-typed force field, meaning parameters are assigned based on the atom type within a given chemical environment. Atomic partial charges are not part of the core GAFF parameter set and must be calculated separately, with the AM1-BCC charge model being a common default [35] [36]. Its widespread adoption and compatibility with the AMBER ecosystem make it a standard choice in many computational drug discovery and materials science studies [37].

The Open Force Field (OpenFF): The OpenFF initiative, exemplified by its SMIRNOFF (SMIRKS Native Open Force Field) format, employs a modern approach known as direct chemical perception [14] [38]. Instead of atom types, it assigns parameters via standard chemical substructure queries written in the SMARTS language. This makes the force field more compact and extensible, as more specific substructures can be introduced to address problematic chemistries without affecting general parameters [38]. OpenFF supports a broader range of elements, including alkali metals (Li, Na, K, Rb, Cs), which is advantageous for modeling materials like solid-state electrolytes [35] [14].

Machine Learning Potentials (MLPs): MLPs, such as ANI and MACE, represent a paradigm shift. They learn the quantum mechanical (QM) energy of an atom in its surrounding chemical environment from large datasets, requiring neither a fixed functional form nor pre-defined parameters [35] [37]. Models like ANI-2x are trained to reproduce specific levels of QM theory (e.g., ωB97X/6-31G*) on millions of molecular conformations [37]. While they offer near-QM accuracy for energies and geometries, they are computationally more expensive than conventional FFs and their performance on structures far from the training data distribution can be unpredictable [35] [37].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes a comparative analysis of key force fields based on benchmark studies.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Force Fields for Molecular Crystals

| Force Field | Parameterization Basis | Element Coverage | Computational Cost | Reported Performance (RMSE vs. QM) | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAFF/GAFF2 [37] [36] | Fitted to experimental and QM data for representative molecules. | C, H, O, N, S, P, F, Cl, Br, I [35] | Low (Baseline) | Torsion energy RMSE: ~1.1 kcal/mol for complex fragments [38]. | High transferability, robust for condensed-phase simulations [37]. | Atom-typing can lead to redundancies; torsional parameters may lack specificity [38]. |

| OpenFF (Sage) [14] [38] | Fitted to high-quality QM data (torsion drives, vibrational frequencies). | C, H, O, N, S, P, F, Cl, Br, Li, Na, K, Rb, Cs [35] [14] | Low (Comparable to GAFF) | Torsion energy RMSE: Can be reduced to ~0.4 kcal/mol with bespoke fitting [38]. | Compact, chemically intuitive, easily extensible, improved torsion profiles. | Relatively new; broader community validation is ongoing. |

| ANI-2x [35] [37] | Trained on ~8.9M molecular conformations at ωB97X/6-31G* level. | H, C, N, O, F, S, Cl [37] | High (~100x GAFF) [37] | Can over-stabilize global minima and over-estimate hydrogen bonding [37]. | Near-QM accuracy for intramolecular energies and geometries on training-like systems. | High computational cost; limited element set; performance on out-of-sample structures is uncertain. |

| MACE [35] [39] | Trained on diverse solid-state and molecular data. | Broad, including metals. | Very High | Achieves meV/atom accuracy in energy and forces with sufficient training [39]. | High accuracy for periodic systems; applicable to complex materials. | Very high computational cost; requires significant training data. |

Application Protocols for Crystal Structure Prediction

The following section outlines a standard workflow for high-throughput organic crystal structure prediction (HTOCSP) and provides a specific protocol for bespoke torsion parameter fitting.

Standard Workflow for High-Throughput CSP

The HTOCSP workflow, as implemented in packages like HTOCSP, can be broken down into six sequential tasks, integrating the force fields discussed above [35] [14]. The diagram below illustrates this automated pipeline.

Title: Automated High-Throughput CSP Workflow

Protocol Steps:

Molecular Analyzer:

Force Field Maker:

- Tool: AMBERTOOLS (for GAFF/OpenFF) or MLP interfaces (for ANI/MACE) [35] [14].

- Action: Generate all necessary force field parameters.

- For GAFF/OpenFF: Extract bond, angle, torsion, and van der Waals parameters. Compute atomic partial charges using a specified scheme (e.g., AM1-BCC, Gasteiger). Output parameters in an XML file (e.g., SMIRNOFF format) [35] [14].

- For MLPs: Load the pre-trained model. Note that MLPs are often used at the re-ranking stage (Step 6) rather than for initial sampling due to computational cost [35].

Crystal Generator:

- Tool: Symmetry-based crystal generators like PyXtal [14].

- Action: Generate random, symmetric crystal packings for the molecule. The user can specify a list of common space groups for organic crystals and the number of molecules in the asymmetric unit. Molecules can be placed on general or special Wyckoff positions if their molecular symmetry permits [14].

Crystal Sampling and Search:

Symmetry-constrained Optimization:

- Calculator: Specialized molecular simulation codes like GULP or CHARMM, which can optimize cell parameters and atomic coordinates without breaking crystal symmetry [35] [14].

- Action: Locally minimize the energy of each candidate structure generated in Step 4 using the selected force field (GAFF/OpenFF). CHARMM is often preferred as the default due to its faster implementation of the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method for long-range electrostatics [35] [14].

Post-processing and Re-ranking:

- Action: The lattice energies of the optimized structures are used for an initial ranking. For higher accuracy, a more robust but expensive method can be employed to re-rank the shortlist of low-energy structures. This often involves:

Protocol for Bespoke Torsion Parameterization with OpenFF BespokeFit

Bespoke torsion fitting is recommended when the default parameters of a general force field inadequately describe the molecular conformation energy landscape [38].

Table 2: Reagent Solutions for Bespoke Fitting

| Research Reagent / Software Tool | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| OpenFF BespokeFit [38] | The primary Python package that automates the workflow for fitting bespoke torsion parameters. |

| OpenFF QCSubmit [38] | A tool for curating, submitting, and retrieving quantum chemical (QC) reference datasets from QCArchive. |

| QCEngine [38] | A unified executor for quantum chemistry programs, used by BespokeFit to generate reference data. |

| OpenFF Fragmenter [38] | Performs torsion-preserving fragmentation to speed up QM torsion scans. |

| Quantum Chemistry Code (e.g., Gaussian, Psi4) [38] | Generates the high-quality reference data (torsion scans) against which new parameters are optimized. |

Workflow Diagram:

Title: Bespoke Torsion Parametrization Workflow

Detailed Methodology:

Fragmentation:

- Objective: Reduce computational cost of QM calculations.

- Action: Use the OpenFF Fragmenter package to break down the target molecule into smaller fragments that preserve the chemical environment of the torsion(s) of interest. This provides a close surrogate for the potential energy surface of the torsion in the parent molecule [38].

SMIRKS Generation:

- Objective: Create a unique chemical substructure identifier for the torsion to be parameterized.

- Action: BespokeFit automatically generates a SMIRKS pattern that defines the central torsion and its chemical context. This pattern will be associated with the new bespoke parameters [38].

QC Reference Data Generation:

- Objective: Obtain accurate reference data.

- Action: Using QCEngine, perform a constrained torsion scan for the generated fragment. The scan typically rotates the dihedral angle in increments (e.g., 15 degrees), computing the single-point energy at each step at a specified level of QM theory (e.g., ωB97X-D/def2-SVP) [38]. The resulting potential energy surface is the target for optimization.

Parameter Optimization:

- Objective: Find optimal torsion force constants.

- Action: BespokeFit employs an optimizer to vary the torsion force constants (k) and phase offsets (φ) in the Fourier series term of the force field, minimizing the root-mean-square error (RMSE) between the MM and QM potential energy surfaces. The original transferable force field (e.g., OpenFF Sage) is used as the starting point [38].

Validation:

- Objective: Assess the real-world performance of the bespoke force field.

- Action: The bespoke force field should be validated in a relevant simulation. For drug discovery applications, this could involve calculating the relative binding free energies of a congeneric series of protein inhibitors and comparing the results to experimental data. A successful parametrization should improve correlation with experiment and reduce the mean unsigned error (MUE) in computed binding affinities [38].

The selection of a force field for high-throughput screening of synthesizable crystalline materials is a critical decision with a direct impact on the predictive power of the simulation. GAFF offers a robust, well-tested option, while OpenFF provides a modern, extensible alternative with the potential for improved accuracy, especially when enhanced with bespoke torsion parametrization. Machine Learning Potentials offer a path to near-quantum accuracy but at a significantly higher computational cost, making them currently best-suited for final re-ranking rather than initial sampling. By integrating these tools into the automated, multi-stage workflow described in this document, researchers can systematically and efficiently navigate the complex energy landscapes of organic crystals, accelerating the discovery of novel materials with tailored properties.

This application note details the integration of High-Throughput Screening (HTS) with advanced disease modeling and computational approaches to accelerate targeted drug discovery for Colorectal Cancer (CRC). It demonstrates a practical workflow, from developing biologically relevant models and implementing a BRET-based functional screen to employing machine learning for data analysis and candidate validation. The protocols are presented within the broader context of early-stage, synthesizable crystalline material research, highlighting the importance of solid-form characterization in the drug development pipeline.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a major global health challenge, with treatment efficacy often limited by tumor heterogeneity and the emergence of drug resistance [40]. High-Throughput Screening (HTS) has revolutionized oncology drug discovery by enabling the rapid testing of thousands of compounds against biologically relevant targets. The success of HTS is contingent on the quality of the cellular models and the robustness of the screening assay. This document provides a detailed methodology for an HTS campaign targeting the disruption of the 14-3-3ζ/BAD protein-protein interaction (PPI), a key complex in cancer cell survival, and validates hits in patient-derived CRC models [41] [42]. Furthermore, it positions this process within a modern research framework that includes crystal structure prediction for novel chemical entities [14].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing a Biologically Relevant Colorectal Cancer Model

Principle: To engineer a genetically defined CRC model that recapitulates the stepwise tumor evolution seen in patients, providing a translatable system for HTS [40].

Materials:

- Cells: Normal human intestinal stem cells.

- Culture Media: Intestinal stem cell culture media, with optional withdrawal of R-Spondin-1 or EGF for selection.

- Reagents:

- Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complexes for gene editing.

- Homology-directed repair (HDR) templates for introducing specific mutations (APC truncation, KRAS G12D).

- Selection agents: Gefitinib (EGFR inhibitor), Nutlin-3 (MDM2 inhibitor), TGF-beta.

- Antibodies for Western Blot (WB) and Immunofluorescence (IF) validation.

Procedure:

- APC Truncation: Introduce a truncating mutation in the APC gene (APCtrunc) into normal human intestinal stem cells via nucleofection of the Cas9 RNP complex and HDR template.

- Functional Validation: Withdraw R-Spondin-1 from the culture media. Select clones that continue to proliferate, confirming WNT pathway independence.

- KRAS G12D Introduction: Introduce the KRAS G12D mutation into selected APC-truncated clones.

- Functional Validation: Culture cells in EGF-free media or treat with gefitinib. Select resistant clones, confirming constitutive KRAS activation.

- TP53 and SMAD4 Knockout: Sequentially knock out TP53 and SMAD4 genes in the engineered (APCtrunc, KRAS G12D) background.

- Functional Validation:

- Treat TP53-edited cells with nutlin-3 and select resistant clones.

- Treat SMAD4-edited cells with TGF-beta and select resistant clones.

- Model Characterization: Validate all genetic modifications using Sanger sequencing and Western blotting. Confirm tumorigenicity in immunocompromised mice and characterize cell morphology and polarity using immunofluorescence (markers: ECAD, CDH17, SOX9, Ki67, MUC2, VIL1) and the Air Liquid Interface (ALI) system [40].