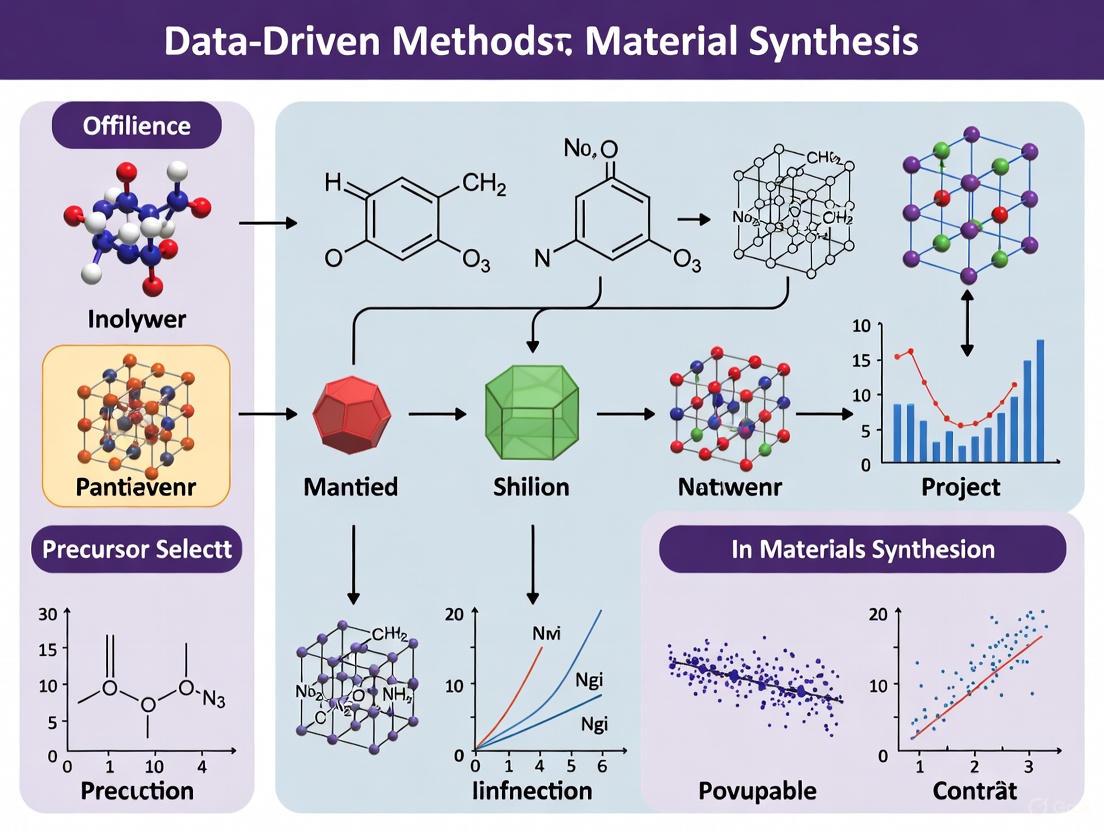

Data-Driven Methods for Material Synthesis: Accelerating Discovery from Molecules to Medicine

This article provides a comprehensive overview of data-driven methodologies that are revolutionizing material synthesis, with a special focus on pharmaceutical applications.

Data-Driven Methods for Material Synthesis: Accelerating Discovery from Molecules to Medicine

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of data-driven methodologies that are revolutionizing material synthesis, with a special focus on pharmaceutical applications. It explores the foundational shift from traditional trial-and-error approaches to modern paradigms powered by artificial intelligence, machine learning, and high-throughput automation. The content systematically covers core statistical and machine learning techniques, their practical implementation in drug development and material design, strategies for overcoming data and optimization challenges, and rigorous validation frameworks. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current advancements to equip readers with the knowledge to integrate data-driven strategies into their own material discovery and optimization workflows, ultimately accelerating the pace of innovation.

The Data-Driven Paradigm Shift in Materials Science

The journey of materials discovery has evolved from an ancient practice rooted in mystery and observation to a modern science powered by computation and data. For centuries, the development of new materials relied on alchemical traditions and laborious trial-and-error experimentation, a process that was often slow, unpredictable, and limited by human intuition. Today, a fundamental shift is underway: the integration of data-driven methods and machine learning (ML) is reshaping the entire materials discovery pipeline, from initial prediction to final synthesis [1]. This paradigm move from traditional alchemy to sophisticated algorithms represents a transformative moment in materials science, offering the potential to systematically address major global challenges through the accelerated creation of novel functional materials [2].

This article details the core computational guidelines and experimental protocols underpinning this modern, data-driven approach to inorganic materials synthesis. It is structured to provide researchers and drug development professionals with actionable methodologies, supported by quantitative data comparisons and explicit workflow visualizations, all framed within the context of optimizing and accelerating the discovery of new materials.

Computational Foundations and Data-Driven Predictions

The cornerstone of modern materials discovery is the use of computational power to predict synthesis feasibility and outcomes before any laboratory work begins. This approach relies on physical models and machine learning techniques to navigate the complex energy landscape of material formation.

Physical Models and Synthesis Feasibility

The synthesis of inorganic materials can be understood through the lens of thermodynamics and kinetics, which govern the energy landscape of atomic configurations [2]. A crucial step in this predictive process is evaluating a material's stability and likelihood of being synthesized.

- Energy Calculations: Density Functional Theory (DFT) is widely used to calculate the formation energy of a crystal structure. The underlying assumption is that synthesizable materials should not have decomposition products that are more thermodynamically stable [2].

- Beyond Simple Stability: Relying solely on formation energy can be insufficient, as it may neglect kinetic stabilization effects that allow for the synthesis of promising metastable materials [2]. Heuristic models that incorporate reaction energies offer a more nuanced view of favorable synthesis pathways [2].

Table 1: Computational Methods for Predicting Synthesis Feasibility

| Method | Core Principle | Key Advantage | Inherent Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charge-Balancing Criterion [2] | Filters materials based on a net neutral ionic charge under common oxidation states. | Simple, fast screening derived from physicochemical knowledge. | Poor predictor for non-ionic materials; only 37% of observed Cs binary compounds meet it [2]. |

| Formation Energy (via DFT) [2] | Compares energy of a crystal to the most stable phase in its chemical space. | Provides a quantitative measure of thermodynamic stability. | Cannot reliably predict feasibility for metastable materials due to neglect of kinetic barriers [2]. |

| Heuristic Thermodynamic Models [2] | Uses reaction energies to predict favorable reactions and pathways. | Offers insight into the actual synthesis process, not just final stability. | Model accuracy is dependent on the quality and scope of the underlying thermodynamic data. |

Machine Learning in Materials Synthesis

Machine learning bypasses time-consuming calculations and experiments by uncovering complex process-structure-property relationships from existing data [2]. However, the application of ML in inorganic materials synthesis faces unique challenges compared to organic chemistry, primarily due to the scarcity of high-quality data and the complexity of solid-state reactions, where universal principles are often lacking [2].

A critical enabler for ML in this field is the development of standardized data representations. The Unified Language of Synthesis Actions (ULSA) provides a robust ontology for describing inorganic synthesis procedures, turning unstructured text from scientific publications into structured, actionable data for model training [3].

A Practical Case Study: Data-Driven Synthesis of a Single-Atom Catalyst for Water Purification

The following section outlines a real-world application where a data-driven approach was used to discover and synthesize a high-performance Single-Atom Catalyst (SAC) for efficient water purification [4].

Experimental Protocol

Objective: To rapidly identify and synthesize an optimal Metal-Nâ‚„ Single-Atom Catalyst for a Fenton-like water purification reaction. Key Reagents: Precursors for 43 transition and main group metal-Nâ‚„ structures. Primary Method: Hard-template method for precise SAC synthesis.

Procedure:

- Data-Driven Prediction: A computational screening of 43 different Metal-Nâ‚„ structures was performed to predict their catalytic performance prior to synthesis [4].

- Precise Synthesis of Top Candidate: The top prediction, an Fe-based SAC, was synthesized using a hard-template method. This method achieved a high loading of ~3.83 wt% Fe-pyridine-Nâ‚„ sites and a highly mesoporous structure, which is critical for performance [4].

- Experimental Validation: The synthesized Fe-SAC was tested in a Fenton-like reaction for pollutant degradation. Its performance was quantified by a rate constant (100.97 minâ»Â¹ gâ»Â²) [4].

- Stability Testing: The optimized Fe-SAC was operated continuously for 100 hours to assess its long-term stability [4].

- Cross-Validation: To confirm the initial prediction, five other metal-SACs (Co, Ni, Cu, and Mn) with varying theoretical activities were also synthesized and tested, with Fe-SAC confirmed as the top performer [4].

- Mechanism Interrogation: Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations were used to reveal the atomic-scale mechanism, showing that the Fe-SAC reduced the energy barrier for intermediate O* formation, leading to highly selective singlet oxygen generation [4].

Key Findings and Quantitative Performance

The data-driven workflow resulted in a catalyst with exceptional performance, validated through rigorous experimentation.

Table 2: Experimental Performance of the Data-Driven Fe-SAC [4]

| Performance Metric | Result | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Decontamination Rate Constant | 100.97 minâ»Â¹ gâ»Â² | Represents one of the best performances reported for Fenton-like catalysts. |

| Fe-Pyridine-Nâ‚„ Site Loading | ~3.83 wt% | Achieved high density of active sites via precise synthesis. |

| Continuous Operational Stability | 100 hours | Demonstrates robustness and practical applicability for long-term use. |

| Key Mechanism (from DFT) | Reduced energy barrier for O* formation; selective ¹O₂ generation. | Provides atomic-scale understanding of the high performance. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and computational resources used in the featured data-driven synthesis workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Data-Driven Synthesis

| Item / Resource | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Hard-Template Agents | Used in the precise synthesis of Single-Atom Catalysts to create a structured, porous support that anchors metal atoms [4]. |

| Metal Precursors | Source of the active metal (e.g., Fe, Co, Ni) for creating Metal-Nâ‚„ sites in Single-Atom Catalysts [4]. |

| Digital Catalysis Platform (DigCat) | An extensive experimental catalysis database (the largest reported to date) used for data-driven prediction and validation [4]. |

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) | A critical database of known crystal structures used for model training and validation of synthesis feasibility predictions [2]. |

| ULSA (Unified Language of Synthesis Actions) | A standardized ontology for representing inorganic synthesis procedures, enabling AI and natural language processing of literature data [3]. |

| 4-Methoxyacridine | 4-Methoxyacridine, CAS:3295-61-2, MF:C14H11NO, MW:209.24 g/mol |

| Citrusinine II | Citrusinine II|C15H13NO5|For Research Use |

The integration of computational guidance, machine learning, and precise experimental synthesis represents a new paradigm for materials discovery [4]. This approach, as demonstrated by the accelerated development of high-performance SACs, moves beyond slow, intuition-driven trial-and-error. Future progress hinges on overcoming challenges such as data scarcity and the class imbalance in synthesis data [2]. The continued development of foundational tools like ULSA for data extraction [3] and platforms like DigCat for data sharing [4] will be crucial. Ultimately, the full integration of these data-driven methods promises to autonomously guide the discovery of novel materials, ushering in a new era of algorithmic alchemy for addressing pressing global needs.

Application Notes: Data-Driven Synthesis of Copper Nanoclusters (CuNCs)

The integration of machine learning (ML) with automated, cloud-based laboratories exemplifies the Fourth Paradigm in modern materials science. This approach addresses critical challenges of data consistency and data scarcity that traditionally hinder robust model development [5]. A representative application is the predictive synthesis of copper nanoclusters (CuNCs), where a data-driven workflow enables high-prediction accuracy from minimal experimental data.

Key Outcomes: Using only 40 training samples, an ML model was developed to predict the success of CuNCs formation based on synthesis parameters. The model provided interpretable mechanistic insights through SHAP analysis, demonstrating how data-driven methods can accelerate material discovery while offering understanding beyond a black-box prediction [5]. This methodology, validated across two independent cloud laboratories, highlights the role of reproducible, high-quality data generated by automated systems in building reliable ML models for materials science [5].

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology for Robotic CuNCs Synthesis and Data Collection

This protocol details the steps for a remotely programmed, robotic synthesis of Copper Nanoclusters, ensuring the generation of a consistent dataset for machine learning.

2.1.1. Primary Reagent Preparation

- Prepare 1 M solutions of Copper Sulfate (CuSOâ‚„), Hexadecyltrimethylammonium Bromide (CTAB), and Ascorbic Acid (AA) in water.

- Prepare a Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) solution.

2.1.2. Automated Synthesis Procedure

- Liquid Handling: Using a robotic liquid handler (e.g., Hamilton Liquid Handler SuperSTAR), transfer varying proportions of CuSOâ‚„ and CTAB into a 2 mL 96-well Deep Well Plate. Add 1 mL of Hâ‚‚O to each well [5].

- Initial Incubation: Cool the reaction mixture to 4 °C and stir at 30 rpm for 1 hour [5].

- Reduction Step: Rapidly add predetermined volumes of AA, NaOH, and 0.8 mL of water to the mixture.

- Final Mixing: Mix the complete reaction mixture at 300 rpm for 15 minutes [5].

2.1.3. Automated Data Acquisition & Analysis

- Sampling: Transfer a 250 µL aliquot from each well to a 96-well UV-Star Plate using the liquid handler.

- Spectroscopic Measurement: Place the plate into a spectrophotometer (e.g., CLARIOstar) and heat to 45 °C.

- Kinetic Data Collection: Once the temperature is stable, record absorbance spectra every 43 seconds for 80 minutes [5].

- Reproducibility Assessment: Calculate the Coefficient of Variation (CV) of the absorbance intensity at each wavelength to quantify the relative spread of the values and assess measurement reproducibility [5].

Machine Learning Model Training and Validation Protocol

This protocol covers the process of using the collected experimental data to train and validate predictive ML models.

2.2.1. Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering

- Input Features: Use the molar concentrations of the reagents (Cu, CTAB, AA, NaOH) as the primary input features for the model.

- Output/Target Variable: Define the output based on the analysis of the absorbance spectra (e.g., success/failure of CuNC formation, or a quantitative measure like peak absorbance) [5].

- Data Splitting: Partition the dataset (e.g., 40 samples) into training and validation sets, ensuring the validation set contains samples never seen during training [5].

2.2.2. Model Training and Hyperparameter Tuning

- Model Selection: Train multiple ML models for comparison. The study employed Linear Regression, Decision Tree, Random Forest, Nearest Neighbour, Gradient Boosted Trees, Gaussian Process, and a Neural Network [5].

- Hyperparameter Optimization: Use automated hyperparameter tuning (e.g., via Wolfram Mathematica's

Predictfunction with performance goal set to "Quality") to maximize prediction accuracy. Key hyperparameters are listed in Table 2 below [5]. - Performance Metrics: Evaluate model performance using the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and the Coefficient of Determination (R²) [5]. The formulas used are:

Table 1: Summary of Reagent Concentrations for CuNCs Training Data

| Sample Group | Number of Samples | Concentration Strategy | Total Molarity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Literature-Based | 4 | Concentrations selected directly from literature. | N/A |

| Incremental Increase | 10 | Concentrations of AA and CTAB were incremented. | N/A |

| Scaled Incremental | 10 | Smaller concentrations of Cu, CTAB, and AA were incremented. | N/A |

| Latin Hypercube | 20 | Generated via Latin Hypercube Sampling method. | 6.25 mM |

Table 2: Machine Learning Model Hyperparameters and Performance Metrics

| Model Type | Key Hyperparameters | Reported Performance (Representative) |

|---|---|---|

| Linear Regression | L2 regularization = 1, Max iterations = 30 | RMSE and R² calculated for validation set. |

| Decision Tree | Nodes = 13, Leaves = 7, Feature fraction = 1 | RMSE and R² calculated for validation set. |

| Random Forest | Feature fraction = 1/3, Leaf size = 4, Trees = 100 | RMSE and R² calculated for validation set. |

| Neural Network | Depth = 8, Parameters = 17,700, Activation = SELU | RMSE and R² calculated for validation set. |

Workflow and System Diagrams

Automated Data-Driven Material Discovery Workflow

Cross-Laboratory Cloud Infrastructure for Validation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Software for Data-Driven Material Synthesis

| Item Name | Function / Role in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| Copper Sulfate (CuSOâ‚„) | Source of copper ions for the formation of copper nanoclusters (CuNCs) [5]. |

| CTAB (Hexadecyltrimethylammonium Bromide) | Serves as a stabilizing agent or template to control the growth and prevent agglomeration of nanoclusters [5]. |

| Ascorbic Acid (AA) | Acts as a reducing agent, converting copper ions (Cu²âº) to atomic copper (Cuâ°) for cluster formation [5]. |

| Hamilton Liquid Handler SuperSTAR | An automated robotic liquid handling system that provides precise control over reagent volumes and mixing, eliminating operator variability and ensuring experimental consistency [5]. |

| CLARIOstar Spectrometer | A multi-mode microplate reader used for high-throughput UV-Vis absorbance measurements to monitor the kinetics of CuNCs formation and characterize the reaction outcome [5]. |

| Wolfram Mathematica | The software environment used for data preprocessing, machine learning model training, hyperparameter optimization, and model validation in the referenced study [5]. |

| Pal-VGVAPG (acetate) | Pal-VGVAPG (Acetate) |

| Fluorexetamine | Fluorexetamine (FXE) |

The field of materials synthesis research is undergoing a profound transformation, moving away from traditional, labor-intensive Edisonian approaches toward a new paradigm defined by the powerful confluence of artificial intelligence (AI), high-throughput automation, and the principles of open science. This shift is critical for overcoming the persistent bottleneck that exists between the rapid computational prediction of new materials and their actual synthesis and optimization [6]. The integration of these three key drivers is creating a cohesive, data-driven research ecosystem that significantly accelerates the entire materials development lifecycle, from initial hypothesis to functional material.

This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who are adopting these advanced, data-driven methodologies. By detailing specific platforms, workflows, and tools, we aim to equip practitioners with the knowledge to implement these transformative approaches in their own laboratories, thereby enhancing the speed, efficiency, and reproducibility of materials and drug discovery.

Conceptual Framework and Core Drivers

The Interlocking Components of Modern Research

The synergy between AI, automation, and open science creates a virtuous cycle of discovery. Artificial Intelligence acts as the central nervous system, capable of planning experiments, analyzing complex data, and generating novel hypotheses [7] [8]. High-Throughput Automation and robotics form the muscle, physically executing experiments with superhuman speed, precision, and endurance [9] [10]. Finally, the framework of Open Science—encompassing open-source hardware, open data, and standardized protocols—provides the connective tissue, ensuring that knowledge, data, and tools are accessible and interoperable across the global research community [7] [9]. This breaks down data silos, prevents redundant experimentation, and maximizes the collective value of every experiment conducted [11] [9].

Visualizing the Self-Driving Laboratory Workflow

The integrated workflow of a self-driving laboratory (SDL) exemplifies this confluence. The process is a closed-loop, iterative cycle that minimizes human intervention while maximizing the rate of knowledge generation, as depicted in the following diagram.

Application Notes: Implementation in Research Environments

Quantitative Impact of Data-Driven Methodologies

Adopting data-driven techniques for materials synthesis directly addresses the inefficiencies of the traditional one-variable-at-a-time (OVAT) approach [6]. The following table summarizes the characteristics and optimal use cases for two primary methodologies.

Table 1: Comparison of Data-Driven Techniques for Materials Synthesis

| Feature | Design of Experiments (DoE) | Machine Learning (ML) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Strength | Optimization of continuous outcomes (e.g., yield, particle size) [6] | Mapping complex synthesis-structure-property relationships; handling categorical outcomes [6] |

| Data Requirements | Effective with small datasets; ideal for exploratory research [6] | Requires large datasets; suited for high-throughput experimentation [6] |

| Key Insight | Identifies interaction effects between variables beyond human intuition [6] | Can uncover non-intuitive patterns from large, complex parameter spaces [6] |

| Best for | Optimizing synthesis within a known phase [6] | Exploring wide design spaces and predicting new crystal phases [6] |

The implementation of these techniques within integrated AI-automation platforms, or Self-Driving Labs (SDLs), leads to transformative gains in research productivity. The table below highlights the demonstrated impacts from various pioneering initiatives.

Table 2: Performance Metrics from SDL Implementations

| Initiative / Platform | Reported Acceleration / Impact | Primary Application Focus |

|---|---|---|

| SDL Platforms (General) | Accelerates materials discovery by up to 100x compared to human capabilities alone [9] | General materials discovery [9] |

| A-Lab (Berkeley Lab) | AI proposes compounds and robots prepare/test them, drastically shortening validation time [10] | Materials for batteries and electronics [10] |

| Artificial Platform | Orchestrates AI and lab hardware to streamline experiments and enhance reproducibility [11] | Drug discovery [11] |

| SmartDope (NCSU) | Autonomous lab focused on developing quantum dots with the highest quantum yield [9] | Quantum dots [9] |

Protocol: Orchestrating a Self-Driving Lab for Drug Discovery

This protocol details the methodology for using a whole-lab orchestration platform, such as the "Artificial" platform described in the search results, to conduct an AI-driven drug discovery campaign [11].

1. Hypothesis Generation & Workflow Design

- Objective: Define the goal of the computational screening campaign (e.g., "Identify potential inhibitors of Target Protein X").

- Procedure:

- Access the platform's web application (e.g., "Workflows" module) to define and configure the R&D process [11].

- The process should integrate an AI model, such as an NVIDIA BioNeMo NIM, for molecular interaction prediction [11].

- The workflow is typically structured as:

AI Virtual Screening -> Compound Selection -> Synthesis Planning.

2. Platform Orchestration & Execution

- Objective: Automate the execution of the defined workflow.

- Procedure:

- The platform's Orchestration Service handles planning and request management using a simplified Python dialect or graphical interface [11].

- The Scheduler/Executor engine uses heuristics and constraints to efficiently allocate computational resources and execute the workflow steps [11].

- The AI model is automatically deployed via the platform's Lab API, which supports connectivity via GraphQL, gRPC, and REST protocols [11].

3. Data Integration & AI Decision-Making

- Objective: Consolidate results and enable data-driven iteration.

- Procedure:

- All results and logs are automatically consolidated into the platform's Data Records repository [11].

- The AI model analyzes the virtual screening results, prioritizing the most promising candidate molecules based on predicted binding affinity and other properties.

- This list of prioritized candidates serves as the output for a dry lab setting or can be passed to robotic systems for synthesis and testing in a wet lab.

4. Validation & Reproducibility

- Objective: Ensure reliable and reproducible outcomes.

- Procedure:

Protocol: Data-Driven Synthesis of Inorganic Materials

This protocol outlines a generalized approach for using data-driven techniques to synthesize and optimize inorganic materials, leveraging methodologies from leading research groups [6].

1. System Definition & Preliminary Screening

- Objective: Identify the most influential synthetic parameters.

- Procedure:

- Define Input Variables: Select critical synthesis parameters (e.g., precursor concentration, temperature, reaction time, pH).

- Define Output Responses: Identify key material properties to optimize (e.g., band gap, particle size, yield, phase purity).

- Screening Design: Use a statistical screening design (e.g., a fractional factorial Plackett-Burman design) to efficiently identify which input variables have statistically significant effects on the outputs with a minimal number of experiments [6].

2. Response Surface Modeling & Optimization

- Objective: Build a predictive model and locate the optimum set of conditions.

- Procedure:

- Design: Based on the screening results, employ a Response Surface Methodology (RSM) design, such as a Central Composite Design (CCD), to explore the non-linear relationships between the key variables [6].

- Synthesis & Characterization: Execute the synthesis and characterization runs as specified by the experimental design.

- Model Fitting: Fit the collected data to a polynomial model (e.g., a quadratic model) to create a response surface that predicts the outcome for any combination of input variables within the explored space [6].

- Optimization: Use the model to identify the set of experimental conditions that produce the desired material properties, targeting a maximum, minimum, or specific value [6].

3. Validation and Active Learning

- Objective: Validate the model and explore beyond the initial design space.

- Procedure:

- Validation: Perform synthesis at the predicted optimum conditions to validate the model's accuracy.

- Active Learning: Integrate the model into an active learning loop. The AI (e.g., a Bayesian optimizer) selects the next most informative experiments to perform, rapidly refining the model or exploring new areas of the parameter space [9] [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table catalogues key hardware, software, and data resources that form the foundation of modern, data-driven materials synthesis laboratories.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Platforms for AI-Driven Materials Research

| Item / Solution | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Whole-Lab Orchestration Platform | Software that unifies lab operations, automates workflows, and integrates AI-driven decision-making [11]. | Artificial platform for scheduling and executing drug discovery workflows [11]. |

| Self-Driving Lab (SDL) Robotic Platform | Integrated system of robotics and AI that automates synthesis and characterization in a closed loop [9] [10]. | Berkeley Lab's A-Lab for autonomous materials synthesis and testing [10]. |

| AI Models for Science | Pre-trained models specifically designed for scientific tasks like molecular interaction prediction or protein structure analysis. | NVIDIA BioNeMo for biomolecular analysis in virtual screening [11]. |

| High-Throughput Synthesis Reactor | Automated reactor systems (e.g., parallel-flow reactors) that enable rapid, parallel synthesis of material libraries [6]. | Accelerated exploration of synthetic parameter spaces for inorganic materials [6]. |

| FAIR Data | Data that is Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable, serving as a foundational resource for training AI models [12]. | Data from the Open Catalyst project used to discover new electrocatalysts [9]. |

| Open-Source Templates | Pre-configured code and protocols for automating scientific discovery in specific domains. | SakanaAI's "AI Scientist" templates for NanoGPT, 2D Diffusion, and Grokking [8]. |

| Orphine | Orphine|Potent Synthetic Opioid for Research | Orphine is a potent synthetic opioid agonist for neurological and pharmacological research. This product is for Research Use Only and is not for human or veterinary use. |

| INE963 | INE963, CAS:2640567-43-5, MF:C19H26N6O2S, MW:402.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integrated Workflow for Autonomous Materials Discovery

The combination of the tools and protocols above creates a powerful, end-to-end pipeline for autonomous discovery. This workflow is agnostic to the specific material being investigated, relying on the seamless handoff between AI, robotics, and data infrastructure.

The confluence of AI, high-throughput automation, and open science is not merely an incremental improvement but a fundamental redefinition of the materials synthesis research paradigm. This report has detailed specific application notes and protocols that demonstrate how this integration creates a powerful, data-driven engine for discovery. By adopting these methodologies and tools, researchers can transition from slow, sequential experimentation to rapid, parallelized, and intelligent discovery processes. This shift is crucial for solving pressing global challenges in energy, healthcare, and sustainability by dramatically accelerating the development of the next generation of advanced materials and therapeutics.

In materials science and engineering, the Process-Structure-Property (PSP) relationship is a foundational framework for understanding how a material's history of synthesis and processing dictates its internal structure, which in turn governs its macroscopic properties and performance [13]. Establishing quantitative PSP linkages is essential for accelerating the development of novel materials, as it moves the field beyond trial-and-error approaches toward predictive, rational design [13]. In the related field of pharmaceutical development, an analogous concept—the Structure-Property Relationship (SPR)—illustrates how modifications to a drug molecule's chemical structure influence its physicochemical and pharmacokinetic properties, such as absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) [14]. The core principle uniting these concepts is that structure serves as the critical link between how a material or molecule is made (process) and its ultimate function (property).

The emergence of data-driven methods, including machine learning (ML) and digital twin technologies, is transforming how researchers define and exploit these PSP linkages [2] [13]. With the advent of powerful computational resources and sophisticated data science algorithms, it is now possible to fuse insights from multiscale modeling and experimental data to create predictive models that guide material synthesis and optimization [13].

Quantitative Characterization of PSP Linkages

A critical step in establishing PSP linkages is the quantitative description of a material's structure. The internal structure of a material is often captured using statistical descriptors, such as n-point spatial correlations, which can represent details of the material structure across a hierarchy of length scales [13]. The properties are then linked to the structure using homogenization (for predicting effective properties from structure) and localization (for predicting local stress/strain fields from applied macroscopic loads) models [13].

Table 1: Key Material Length Scales and Corresponding Characterization/Modeling Techniques

| Material Length Scale | Example Characterization Techniques | Example Modeling Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| Atomic / Molecular | Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM), High-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy (HRTEM) [13] | Density Functional Theory (DFT), Molecular Dynamics (MD) [13] |

| Microscale | Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), Electron Backscatter Diffraction (EBSD), X-ray Tomography [13] | Crystal Plasticity Finite Element Modeling (CPFEM), Phase-Field Simulations [13] |

| Macroscale | Mechanical Testing (e.g., Tensile, Fatigue) [13] | Finite Element Models (FEM) [13] |

In pharmaceutical research, Quantitative Structure-Property Relationships (QSPR) are built using mathematical descriptors of molecular structure to predict properties like solubility and metabolic stability. Successful drug discovery campaigns demonstrate extensive optimization using strategies such as bioisosteric replacement (swapping a group of atoms with another that has similar properties), attaching a solubilizing group, and deuterium incorporation to fine-tune these properties [14].

Table 2: Common Material Synthesis Methods and Their Characteristics

| Synthesis Method | Key Features | Typical Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Solid-State Reaction | Reaction of solid reactants at high temperatures; no solvent; large-scale production [2] | Highly crystalline materials with few defects; often the most thermodynamically stable phase; microcrystalline structures [2] |

| Synthesis in Fluid Phase | Uses solvents, melts, or fluxes to facilitate atomic diffusion and increase reaction rates [2] | Can produce kinetically stable compounds; offers better control over particle size and morphology [2] |

| Hydrothermal Synthesis | A type of fluid-phase synthesis using water in a closed vessel at high pressure [2] | Often used to grow single crystals or synthesize specific mineral phases [2] |

Experimental Protocols for Establishing PSP Linkages

Protocol: Data Collection for a Material Digital Twin

Objective: To systematically gather the multi-modal data required to create and validate a digital twin of a material, which is a computational representation that mirrors the evolution of the structure, process, and performance of a physical material sample [13].

Background: A holistic PSP understanding requires fusing disparate datasets from both experiments and simulations [13].

Material Processing:

- Record all synthesis parameters, including precursor identities and purities, reaction temperature, time, pressure, heating/cooling rates, and any post-synthesis treatments (e.g., annealing, quenching) [2].

- For solid-state reactions, note the number of grinding and heating cycles [2].

- For fluid-phase synthesis, document the solvent, concentration, stirring rate, and pH [2].

Structural Characterization:

- Perform multi-scale microscopy according to the hierarchy of the material's structure.

- Macroscale: Use optical microscopy for initial assessment.

- Microscale: Utilize Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) with Electron Backscatter Diffraction (EBSD) for microstructural and crystallographic orientation information [13].

- Nanoscale: Employ Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) or Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) for nanoscale or atomic-level structural details [13].

- Bulk Analysis: Use X-ray Diffraction (XRD) to identify crystalline phases present in the bulk material [2].

Property Evaluation:

- Conduct mechanical testing (e.g., tension, compression, hardness) to determine yield strength, ductility, and fracture toughness [13].

- Perform functional property testing relevant to the application (e.g., thermal conductivity, electrical impedance, ionic conductivity, catalytic activity).

Data Curation and Integration:

- Annotate all datasets with a unique material sample identifier to track its processing history.

- Where possible, use resource identifiers (e.g., from the Resource Identification Initiative) for reagents and equipment to ensure unambiguous reporting [15].

- Assemble data into a structured database where process parameters, structural descriptors, and property measurements are logically linked.

Protocol: Inorganic Material Synthesis via Solid-State Reaction

Objective: To synthesize a polycrystalline inorganic ceramic oxide (e.g., a perovskite) via a conventional solid-state reaction method, with monitoring via in-situ X-ray diffraction (XRD) [2].

Background: This method involves direct reaction of solid precursors at high temperature to form the target product phase. It is suitable for producing thermodynamically stable, crystalline materials on a large scale [2].

Precursor Preparation:

- Weigh out powdered solid precursors (e.g., metal carbonates or oxides) in the required stoichiometric ratios.

- The total mass of powder should be appropriate for the milling equipment used.

Mixing and Grinding:

- Transfer the powder mixture to a ball milling jar.

- Add grinding media (e.g., zirconia balls) and a suitable milling medium (e.g., ethanol) if wet milling is employed.

- Mill the mixture for a predetermined time (e.g., 6-12 hours) to ensure homogeneity and reduce particle size.

Calcination:

- Dry the milled slurry in an oven and then transfer the powder to a crucible suitable for high temperatures (e.g., alumina or platinum).

- Place the crucible in a furnace and heat to a calculated temperature (e.g., 1000-1400°C) for several hours to facilitate the solid-state reaction and form the desired phase.

- For in-situ XRD monitoring, use a high-temperature diffraction stage to collect patterns at regular intervals during heating, dwelling, and cooling [2].

Post-Processing and Characterization:

- After calcination, allow the furnace to cool to room temperature.

- Remove the powder and re-grind it in a mortar and pestle or ball mill to break up agglomerates.

- Characterize the phase purity of the resulting powder using laboratory XRD.

Visualization of PSP Workflows and Data Integration

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz, illustrate the core concepts and workflows involved in establishing and utilizing PSP linkages.

Diagram 1: The core PSP linkage.

Diagram 2: Data-driven framework for building PSP models.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials and Computational Tools for PSP Research

| Item / Solution | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Solid Precursors (e.g., metal oxides, carbonates) | Starting materials for solid-state synthesis; purity is critical to avoid impurity phases and achieve target composition [2]. |

| Grinding Media (e.g., Zirconia milling balls) | Used in ball milling to homogenize powder mixtures and reduce particle size, thereby increasing reactivity [2]. |

| High-Temperature Furnace & Crucibles | Provides the thermal energy required for solid-state diffusion and reaction; crucibles must be inert to the reactants at high T [2]. |

| In-situ XRD Stage | Allows for real-time monitoring of phase formation and transformation during heating, providing direct insight into the synthesis process [2]. |

| Digital Twin Software Framework | Computational environment for integrating multi-scale data, running homogenization/localization models, and updating the digital representation of the material [13]. |

| Machine Learning Libraries (e.g., for Python/R) | Used to build surrogate models that bypass time-consuming calculations and uncover complex, non-linear PSP relationships [2] [13]. |

| Bromazolam-d5 | Bromazolam-d5 Stable Isotope |

| Desalkylgidazepam-d5 | Desalkylgidazepam-d5, MF:C15H11BrN2O, MW:320.19 g/mol |

The Materials Innovation Ecosystem represents a transformative framework designed to accelerate the discovery, development, and deployment of new materials. This ecosystem integrates computation, experiment, and data sciences to overcome traditional, sequential approaches that have historically relied on serendipitous discovery and empirical development [16] [17]. The core vision is to create a coupled infrastructure that enables high-throughput methods, leveraging modern data analytics and computational power to drastically reduce the time from material concept to commercial application [17].

The impetus for this ecosystem stems from global competitiveness needs, as articulated by the US Materials Genome Initiative (MGI), which emphasizes the critical linkage between materials development and manufacturing processes [17]. This framework has gained substantial traction across academia, industry, and government sectors, creating a collaborative environment where stakeholders contribute complementary expertise and resources. The ecosystem's effectiveness hinges on its ability to foster interdisciplinary collaboration between materials scientists, computational experts, data scientists, and manufacturing engineers [16].

Stakeholder Roles and Interactions

Academic Institutions

Academic institutions serve as the primary engine for fundamental research and workforce development within the materials innovation ecosystem. Universities provide the foundational knowledge in materials science, chemistry, physics, and computational methods that underpin innovation. For instance, Georgia Tech's Institute for Materials (IMat) supports more than 200 materials-related faculty members across diverse disciplines including materials science and engineering, chemistry and biochemistry, chemical and biomolecular engineering, mechanical engineering, physics, biology, and computing and information sciences [16].

Academic research groups are increasingly focused on developing data-driven methodologies for materials discovery and synthesis. They create computational frameworks and machine learning tools that can predict material properties and optimal synthesis conditions before experimental validation [1]. This computational guidance significantly increases the success rate of experiments and optimizes resource allocation. Furthermore, universities are responsible for educating and training the next generation of materials scientists and engineers, equipping them with interdisciplinary skills that span traditional boundaries between computation, experimentation, and data analysis [16].

Industry Partners

Industry stakeholders translate fundamental research into commercial applications and market-ready products. They bring crucial perspective on scalability, cost-effectiveness, and manufacturing constraints to the ecosystem. Industrial participants often identify specific material performance requirements and application contexts that guide research directions toward practical solutions [17] [18].

Companies operating within the materials innovation ecosystem contribute expertise in manufacturing scale-up, quality control, and supply chain management. Their involvement ensures that newly developed materials can be produced consistently at commercial scales with acceptable economics. The HEREWEAR project's approach to creating circular, bio-based, and local textiles exemplifies how industry partners collaborate to redefine system goals toward more sustainable outcomes [18]. Industry participation also provides vital feedback loops that help academic researchers understand real-world constraints and performance requirements.

Government and Policy Makers

Government agencies provide strategic direction, funding support, and policy frameworks that enable and accelerate materials innovation. Initiatives like the Materials Genome Initiative (MGI) establish national priorities and coordinate efforts across multiple stakeholders [17]. Government funding agencies support high-risk research that may have long-term transformational potential but falls outside typical industry investment horizons.

Policy makers also facilitate standards development, intellectual property frameworks, and regulatory pathways that help translate laboratory discoveries into commercial products. They support the creation of shared infrastructure, databases, and research facilities that lower barriers to entry for various participants in the ecosystem. By aligning incentives and reducing coordination costs, government actors help create the collaborative environment essential for ecosystem success.

Table 1: Key Stakeholder Roles in the Materials Innovation Ecosystem

| Stakeholder | Primary Functions | Resources Contributed | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academic Institutions | Fundamental research, Workforce development, Computational tools | Expertise, Research facilities, Student training | New knowledge, Predictive models, Trained researchers |

| Industry Partners | Application focus, Manufacturing scale-up, Commercialization | Market needs, Manufacturing expertise, Funding | Market-ready products, Scalable processes |

| Government Agencies | Strategic planning, Funding, Policy frameworks | Research funding, Infrastructure, Coordination | National priorities, Shared resources, Standards |

Data-Driven Methodologies for Material Synthesis

Computational Guidance and Machine Learning

The integration of computational guidance and machine learning (ML) has revolutionized materials synthesis by providing predictive insights that guide experimental design. Computational approaches based on thermodynamics and kinetics help researchers understand synthesis feasibility before laboratory work begins [1]. Physical models can predict formation energies, phase stability, and reaction pathways, significantly reducing the trial-and-error traditionally associated with materials development.

Machine learning techniques further accelerate this process by identifying patterns in existing materials data that humans might overlook. ML algorithms can recommend synthesis parameters, predict outcomes, and identify promising material compositions from vast chemical spaces [1]. The data-driven approach involves several key steps: data acquisition from literature and experiments, identification of relevant material descriptors, selection of appropriate ML techniques, and validation of predictions through targeted experiments [1]. This methodology has proven particularly valuable for inorganic material synthesis, where multiple parameters often interact in complex ways.

Data-Driven Synthesis of Single-Atom Catalysts

A compelling example of data-driven materials development is the recent work on single-atom catalysts (SACs) for water purification. Researchers employed a strategy combining data-driven predictions with precise synthesis to accelerate the development of high-performance SACs [4]. The process began with computational screening of 43 metal-N4 structures comprising transition and main group metal elements using a hard-template method [4].

The data-driven approach identified an iron-based single-atom catalyst (Fe-SAC) as the most promising candidate. This Fe-SAC featured a high loading of Fe-pyridine-N4 sites (approximately 3.83 wt%) and a highly mesoporous structure [4]. Experimental validation confirmed its exceptional performance, demonstrating an ultra-high decontamination performance with a rate constant of 100.97 minâ»Â¹ gâ»Â² [4]. The optimized Fe-SAC maintained continuous operation for 100 hours, representing one of the best performances reported for Fenton-like catalysts used in wastewater purification [4].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Data-Driven Single-Atom Catalyst for Water Purification

| Parameter | Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Fe-pyridine-N4 Site Loading | 3.83 wt% | High density of active sites |

| Rate Constant | 100.97 minâ»Â¹ gâ»Â² | Exceptional catalytic activity |

| Operational Stability | 100 hours | Practical durability for applications |

| Metal Structures Screened | 43 | Comprehensive computational selection |

| Key Mechanism | Selective singlet oxygen generation | Efficient pollutant degradation |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Template-Based Synthesis Methods

The template method represents a powerful approach for controlling material morphology and pore structure during synthesis. This method involves using a template to direct the formation of target materials with precise structural characteristics [19]. The template method is simple, highly reproducible, and predictable, providing exceptional control over pore structure, dimensions, and material morphology [19].

The general synthesis procedure using templates includes three main steps: (1) preparation of templates, (2) synthesis of target materials using the templates, and (3) removal of templates [19]. Templates are classified based on their properties and spatial domain-limiting capabilities, with the most common classification distinguishing between hard templates and soft templates [19].

Hard Template Method

Hard templates typically consist of rigid materials with well-defined structures, such as porous silica, molecular sieves, metals, or carbons [19]. The synthesis process involves infiltrating the template with a precursor material, converting the precursor to a solid through chemical or thermal treatment, and subsequently removing the template through chemical etching or calcination [19]. Hard templates provide excellent domain limitation and high stability, enabling precise control over material size and morphology [19]. However, template removal can be challenging and may potentially damage the synthesized material structure [19].

Soft Template Method

Soft templates typically consist of surfactant molecules, polymers, or biological macromolecules that self-assemble into defined structures [19]. The synthesis occurs at the interface between the soft template and precursor materials, with molecular organization driven by micelle formation and intermolecular forces [19]. Soft templates generally offer milder removal conditions and simpler processing compared to hard templates, representing a current trend in template-based material preparation [19].

Protocol: Hydrothermal Synthesis of α-Fe₂O₃ Nanorod Template

The following detailed protocol exemplifies the synthesis of a specific template material used in various applications, including catalyst supports and functional materials:

Reagent Preparation:

- Dissolve 3.028 g of iron chloride hexahydrate (FeCl₃·6H₂O) and 0.72 g of urea (CO(NH₂)₂) in deionized water to form a 60 mL mixture solution [20].

Substrate Placement:

- Lean F-doped tin oxide (FTO) substrates perpendicularly in the reaction solution [20].

Hydrothermal Reaction:

- Seal the reaction vessel tightly and maintain at 100°C for 24 hours in an electric oven [20].

Annealing Treatment:

- Anneal the resulting products at 500°C for 30 minutes in a muffle furnace [20].

This protocol produces an α-Fe₂O₃ nanorod template suitable for further functionalization or use as a sacrificial template in subsequent material synthesis steps.

Data-Driven Catalyst Development Protocol

The development of high-performance single-atom catalysts follows a systematic data-driven protocol:

Computational Screening:

Candidate Selection:

- Identify promising candidates based on computational predictions, particularly focusing on structures that reduce energy barriers for key reaction steps [4].

Precise Synthesis:

- Employ hard-template methods to synthesize selected candidates with controlled atomic dispersion and porous structure [4].

Experimental Validation:

Mechanistic Study:

- Use computational methods to understand the fundamental mechanisms responsible for observed performance [4].

- For the Fe-SAC example, DFT calculations revealed that the catalyst reduced the energy barrier for intermediate O* formation, resulting in highly selective generation of singlet oxygen for pollutant degradation [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Template-Based Material Synthesis

| Reagent/Category | Function | Examples/Specific Instances |

|---|---|---|

| Hard Templates | Provide rigid scaffolding with controlled porosity for material synthesis | Porous silica, Mesoporous carbon, Metal oxides, Molecular sieves [19] |

| Soft Templates | Self-assembling molecular systems that direct material morphology | Surfactants, Polymers, Biological macromolecules [19] |

| Metal Precursors | Source of metallic components in catalyst synthesis | Iron chloride hexahydrate (FeCl₃·6H₂O), Zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO₃)₂) [20] |

| Structure-Directing Agents | Control molecular organization during synthesis | Urea (CO(NHâ‚‚)â‚‚), Hexamethylenetetramine (C₆Hâ‚â‚‚Nâ‚„) [20] |

| Computational Resources | Enable prediction and screening of material properties | Density Functional Theory (DFT) codes, Materials databases (e.g., Digital Catalysis Platform) [4] [1] |

| Manifaxine | Manifaxine, CAS:135306-42-2, MF:C12H15F2NO2, MW:243.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| [Mpa1, D-Tic7]OT | [Mpa1, D-Tic7]OT|Oxytocin Analogue|RUO | [Mpa1, D-Tic7]OT is a synthetic oxytocin receptor modulator for research. This product is for Research Use Only, not for human or veterinary use. |

Integrated Workflows in the Materials Innovation Ecosystem

The full power of the materials innovation ecosystem emerges when stakeholders and methodologies integrate into cohesive workflows. The following diagram illustrates how data-driven approaches connect different elements of the ecosystem to accelerate materials development:

This integrated workflow demonstrates how data flows between stakeholders and methodology components, creating a virtuous cycle of prediction, synthesis, validation, and knowledge capture that accelerates materials innovation.

The Materials Innovation Ecosystem represents a paradigm shift in how materials are discovered, developed, and deployed. By fostering collaboration between academia, industry, and government stakeholders, and leveraging data-driven methodologies, this ecosystem dramatically accelerates the materials development timeline. Template-based synthesis methods provide precise control over material structure, while computational guidance and machine learning optimize experimental approaches and predict outcomes before laboratory work begins. As these methodologies continue to evolve and integrate, they promise to address pressing global challenges in areas such as water purification, sustainable energy, and advanced manufacturing through more efficient and targeted materials development.

A Toolbox for Innovation: Core Data-Driven Methods and Their Applications

In the competitive landscapes of materials science and pharmaceutical development, the conventional "one-variable-at-a-time" (OVAT) approach to experimentation has become a significant bottleneck. This trial-and-error method is not only time-consuming and resource-intensive but also frequently fails to identify optimal conditions because it cannot detect critical interactions between factors [6]. In response to these challenges, Design of Experiments (DoE) and Response Surface Methodology (RSM) have emerged as statistical powerhouses that enable researchers to systematically explore complex experimental spaces, model relationships between variables, and efficiently identify optimum conditions [21] [22].

The significance of these methodologies is particularly pronounced within the context of data-driven material synthesis research, where the parameter space is often large and multidimensional. Factors such as reagent choices, synthesis methods, temperature, time, stoichiometric ratios, and concentrations can interact in complex ways that defy conventional chemical intuition [6]. Similarly, in pharmaceutical formulation development, excipient combinations and processing parameters must be optimized to achieve critical quality attributes [23] [24]. DoE and RSM provide structured frameworks for navigating these complexities, transforming the experimental process from random exploration to targeted investigation.

Theoretical Foundations: Understanding DoE and RSM

Design of Experiments (DoE)

DoE is a systematic approach for planning, conducting, analyzing, and interpreting controlled tests to evaluate the factors that control the value of a parameter or group of parameters [25]. At its core, DoE involves the deliberate simultaneous variation of input factors (independent variables) to determine their effect on response variables (dependent variables) [25]. This approach allows researchers to maximize the information gained from a minimal number of experimental runs while ensuring statistical reliability.

Key principles underlying DoE include:

- Randomization: The random sequence of experimental runs to minimize the effects of lurking variables

- Replication: Repeated experimental runs to estimate variability and improve precision

- Blocking: Arranging experiments into homogeneous groups to account for known sources of variability

The advantages of DoE over OVAT approaches are substantial. While OVAT methods can only explore one-dimensional slices of a multidimensional parameter space, DoE captures interaction effects between factors—a critical capability since many material synthesis and pharmaceutical processes are driven by these interactions [6]. Furthermore, properly designed experiments can provide a prediction equation for the process in the form of Y = f(Xâ‚, Xâ‚‚, X₃...Xâ‚™), enabling researchers to forecast outcomes for untested factor combinations [25].

Response Surface Methodology (RSM)

RSM is a collection of mathematical and statistical techniques that builds upon DoE principles to model, analyze, and optimize processes where the response of interest is influenced by several variables [21] [22]. First introduced by Box and Wilson in 1951, RSM focuses on designing experiments, fitting mathematical models to empirical data, and exploring the relationships between multiple explanatory variables and one or more response variables [21] [22].

The methodology typically proceeds through sequential phases:

- Screening experiments to identify significant factors

- Steepest ascent/descent experiments to move rapidly toward the optimum region

- Detailed modeling using response surface designs to characterize the optimum region

RSM employs empirical model-fitting, most commonly using first-order or second-order polynomial functions. A standard quadratic RSM model is expressed as: Y = β₀ + ∑βᵢXᵢ + ∑βᵢᵢXᵢ² + ∑βᵢⱼXᵢXⱼ + ε where Y is the predicted response, β₀ is the constant coefficient, βᵢ represents the linear coefficients, βᵢᵢ represents the quadratic coefficients, βᵢⱼ represents the interaction coefficients, and ε is the random error term [21].

This empirical approach is particularly valuable when theoretical models of the process are cumbersome, time-consuming, inefficient, or unreliable [22]. By using a sequence of designed experiments, RSM enables researchers to locate optimal conditions—whether for maximizing, minimizing, or attaining a specific target for the response variable(s) [22].

Comparative Analysis: DoE versus Machine Learning

While both DoE/RSM and machine learning (ML) are data-driven approaches, they offer complementary strengths for different research scenarios. DoE is particularly advantageous for novel, low-throughput exploratory research where little prior knowledge exists and the ability to collect large datasets is limited [6]. Its regression-based analysis makes it ideally suited for continuous outcomes such as yield, particle size, or emission wavelength within a specific material phase [6].

In contrast, ML techniques typically require larger datasets but excel at mapping complex synthesis-structure-property relationships that may be beyond human intuition [6] [26]. ML classifiers can handle both mixed and categorical variables and outcomes, making them better suited for problems involving synthesis across multiple crystal phases or when high-throughput synthesis generates substantial data [6]. The integration of automated robotic systems and multichannel flow reactors with ML approaches has created powerful platforms for systematic exploration of synthetic landscapes [6].

Table 1: Comparison of DoE/RSM and Machine Learning Approaches

| Aspect | DoE/RSM | Machine Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Data Requirements | Effective with small datasets | Typically requires large datasets |

| Variable Types | Best with continuous variables | Handles mixed and categorical variables well |

| Primary Applications | Optimization within a known experimental region | Exploration of complex, high-dimensional spaces |

| Outcome Types | Continuous responses | Continuous and categorical outcomes |

| Experimental Bias | More susceptible to initial experimental region selection | Can uncover patterns beyond initial assumptions |

| Implementation Context | Low-throughput, novel systems | High-throughput, data-rich environments |

Experimental Design Strategies and Mathematical Frameworks

Key Experimental Designs in RSM

Central Composite Design (CCD)

Central Composite Design is one of the most prevalent response surface designs, consisting of three distinct components [21]:

- Factorial points: Represent all combinations of factor levels (as in a standard factorial design)

- Center points: Repeated runs at the midpoint of the experimental region to estimate experimental error and check model adequacy

- Axial points (star points): Positioned along each factor axis at a distance α from the center to capture curvature and enable estimation of quadratic effects

CCDs can be arranged in different variations including circumscribed CCD (axial points outside factorial cube), inscribed CCD (factorial points scaled within axial range), and face-centered CCD (axial points on factorial cube faces) [21]. A key property of CCDs is rotatability—the variance of predicted responses remains constant at points equidistant from the center, ensuring uniform precision across the experimental region [21] [22].

Box-Behnken Design (BBD)

Box-Behnken Designs are spherical, rotatable second-order designs based on balanced incomplete block designs [21] [24]. For a 3-factor BBD with one center point, the number of required runs is calculated as 2k × (k - 1) + nₚ, where k is the number of factors and nₚ is the number of center points [21]. This results in 13 runs for a 3-factor design [21].

BBDs are particularly advantageous when a full factorial experiment is impractical due to resource constraints, as they efficiently explore the factor space with fewer experimental runs than a full factorial design [21] [27]. However, they do not include corner points and are therefore inappropriate when testing at extreme factor settings is necessary.

Table 2: Comparison of Primary RSM Experimental Designs

| Design Characteristic | Central Composite Design (CCD) | Box-Behnken Design (BBD) |

|---|---|---|

| Design Points | Factorial + Center + Axial points | Combinations of midpoints of factor edges + center points |

| Number of Runs (3 factors) | 15-20 depending on center points | 13 |

| Factor Levels | 5 levels | 3 levels |

| Region of Interest | Cuboidal or spherical | Spherical |

| Applications | Sequential experimentation | When extreme conditions are undesirable |

| Advantages | Can be used sequentially; estimates curvature well | Fewer runs than CCD; avoids extreme factor combinations |

Model Fitting and Analysis

Once experimental data are collected according to the designed matrix, the next critical step is fitting a mathematical model that describes the relationship between factors and responses [21]. Regression analysis, typically via least squares method, is used to estimate coefficients (β₀, βᵢ, βᵢⱼ) in the polynomial equation [21].

The validity and significance of the fitted model are then evaluated using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), which decomposes the total variability in the data into components attributable to each factor, their interactions, and residual error [27] [25]. Key metrics in model evaluation include:

- Coefficient of Determination (R²): Proportion of variance in the response explained by the model

- Adjusted R²: R² adjusted for the number of terms in the model

- Predicted R²: Measure of how well the model predicts new data

- p-values: Statistical significance of model terms

Model adequacy is further checked through diagnostic plots of residuals, which should be independent, normally distributed, and have constant variance [25].

Application Protocols: Materials Synthesis and Pharmaceutical Development

Protocol 1: Optimizing Inorganic Material Synthesis Using DoE/RSM

Background: The synthesis of novel inorganic materials with tailored properties represents a significant challenge in materials science. Traditional OVAT approaches often fail to identify true optima due to complex interactions between synthesis parameters [6].

Objective: To systematically optimize the synthesis of an inorganic material (e.g., metal oxide nanoparticles) for target properties such as particle size, yield, and crystallinity.

Experimental Workflow:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Define Objective and Responses: Clearly articulate the research goal—e.g., "minimize particle size while maximizing yield of metal oxide nanoparticles." Identify measurable responses (e.g., particle size, PDI, yield, crystallite size) and establish measurement protocols [6].

Identify Critical Factors: Through literature review and preliminary experiments, identify key process parameters likely to influence responses. Common factors in inorganic synthesis include:

- Precursor concentration

- Temperature and time

- pH

- Mixing rate

- Reactant stoichiometry

Select Experimental Design: Begin with a screening design (e.g., fractional factorial) if many factors are being considered. For detailed optimization with limited factors (typically 2-5), employ RSM designs such as CCD or BBD. Determine factor levels based on practical constraints and preliminary knowledge [6] [21].

Execute Experimental Runs: Perform synthesis according to the randomized run order specified by the design matrix. Maintain careful control over non-studied parameters. Document any unexpected observations or deviations from protocol.

Analyze Data and Fit Model: Use statistical software to:

- Perform ANOVA to identify significant factors and interactions

- Fit an appropriate model (linear, quadratic, or special cubic)

- Check model adequacy through residual analysis

- Generate contour and 3D surface plots to visualize factor-response relationships [21]

Validate Model and Optimize: Conduct confirmation experiments at predicted optimal conditions. Compare predicted versus actual responses to validate model accuracy. If discrepancy exceeds acceptable limits, consider model refinement through additional experiments [6].

Research Reagent Solutions for Inorganic Material Synthesis:

- Metal Salt Precursors: Source of metal ions (e.g., metal nitrates, chlorides, acetylacetonates); purity >99% recommended

- Precipitation Agents: Hydroxides, carbonates, or organic precipitants that control nucleation and growth

- Surfactants/Templating Agents: Structure-directing agents (e.g., CTAB, PVP) to control particle size and morphology

- Solvents: High-purity aqueous and non-aqueous media with controlled ionic strength and pH

- Dopants: Trace elements for modifying material properties, typically 0.1-5 mol%

Protocol 2: Pharmaceutical Formulation Optimization Using RSM

Background: Pharmaceutical formulation development requires balancing multiple, often competing, quality attributes. The case study of levetiracetam effervescent tablets demonstrates RSM's applicability to pharmaceutical systems [24].

Objective: To optimize an effervescent tablet formulation containing citric acid (Xâ‚: 320-960 mg) and effersoda (Xâ‚‚: 320-960 mg) to achieve target effervescence time, hardness, and friability [24].

Experimental Workflow:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Define Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) and Critical Process Parameters (CPPs): Identify formulation and process parameters with significant impact on product quality. For effervescent tablets, key factors include acid:base ratio, compression force, and lubricant concentration [24].

Select RSM Design: For two factors, a Central Composite Rotatable Design (CCRD) with 14 runs (6 center points, 4 cube points, 4 axial points) provides efficient exploration of the design space while allowing estimation of quadratic effects [24].

Prepare Tablet Batches: Manufacture tablets according to the experimental design using appropriate processing methods (e.g., dry granulation via roll compaction for moisture-sensitive formulations) [24].

Characterize Tablets: Evaluate CQAs for each batch including:

- Effervescence time (target: complete dissolution within 3-5 minutes)

- Tablet hardness (using pharmaceutical hardness tester)

- Friability (using Roche friabilator)

- Drug content uniformity [24]

Develop Polynomial Models: Fit second-order polynomial models to each response using multiple linear regression. For the levetiracetam case study, the models demonstrated excellent correlation with R² values of 0.9808, 0.9939, and 0.9892 for effervescence time, hardness, and friability, respectively [24].

Apply Desirability Function for Multi-Response Optimization: Use desirability functions to simultaneously optimize multiple responses. Transform each response to a desirability value (0-1 scale), then calculate overall desirability as the geometric mean of individual desirabilities [24].

Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmaceutical Formulation:

- API (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient): Drug substance (e.g., levetiracetam, bisoprolol fumarate) with specified purity and particle size distribution

- Effervescent Couple: Acid (citric, tartaric, adipic) and base (sodium bicarbonate, sodium carbonate, effersoda) components in optimal ratio

- Binders/Diluents: Water-soluble excipients (mannitol, sorbitol, anhydrous lactose) for tablet structure and dissolution

- Lubricants: Magnesium stearate, sodium stearyl fumarate in minimal concentrations (0.5-2%) to prevent sticking

- Sweeteners/Flavors: Aspartame, acesulfame-K, and pharma-approved flavors to enhance palatability

Validation and Performance Metrics: Case Study in Hybrid Materials

Background: A comprehensive 2024 study compared the effectiveness of factorial, Taguchi, and RSM models for analyzing mechanical properties of epoxy matrix composites reinforced with natural Chambira fiber and synthetic fibers [28].

Experimental Design: The research employed 90 treatments with three replicates for each study variable, creating a robust dataset for model validation [28].

Performance Outcomes:

Table 3: Model Performance Comparison for Hybrid Material Analysis [28]

| Statistical Model | Coefficient of Determination (R²) | Predictive Capability | Overall Desirability | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modified Factorial | >90% for most mechanical properties | High | 0.7537 | Best suited for research with 99.73% overall contribution |

| Taguchi | Variable across properties | Moderate | Not specified | Effective for initial screening |

| RSM | Strong for specific responses | High for targeted optimization | Not specified | Excellent for mapping response surfaces |

The validation study revealed that model refinement by considering only significant source elements dramatically improved performance metrics, reflected in increased coefficients of determination and enhanced predictive capacity [28]. The modified factorial model emerged as most appropriate for this materials research application, achieving an overall contribution of 99.73% with global desirability of 0.7537 [28].

Advanced Applications and Integration with Emerging Technologies

The integration of DoE/RSM with other analytical and computational methods creates powerful frameworks for complex research challenges. A notable example comes from polymer nanocomposites, where researchers combined DoE, RSM, and Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression to characterize and optimize low-density polyethylene/organically modified montmorillonite nanocomposites [29].

This integrated chemometric approach enabled simultaneous correlation of four processing parameters (clay concentration, compatibilizer concentration, mixing temperature, and mixing time) with six nanocomposite properties (interlayer distance, decomposition temperature, melting temperature, Young's modulus, loss modulus, and storage modulus) [29]. The PLS model achieved an R² of 0.768 (p ≤ 0.05), identifying clay% and compatibilizer% as the most influential parameters while revealing complex interactions among factors [29].

Looking forward, the convergence of traditional statistical methods with artificial intelligence and automation presents exciting opportunities. Machine learning algorithms can enhance DoE/RSM by:

- Identifying complex nonlinear relationships beyond polynomial approximations

- Optimizing experimental designs for specific objectives

- Enabling real-time adaptive experimentation through robotic platforms

- Facilitating knowledge transfer between related material systems [26]

These advanced applications highlight how DoE and RSM continue to evolve as foundational methodologies within the broader context of data-driven research, maintaining their relevance through integration with emerging technologies rather than being replaced by them.

The adoption of machine learning (ML) for property prediction represents a paradigm shift in materials science and drug discovery, enabling the rapid identification of novel materials and compounds with tailored characteristics. This shift is propelled by the convergence of increased computational power, the proliferation of experimental and computational data, and advancements in ML algorithms [30]. Data-driven science is now recognized as the fourth scientific era, complementing traditional experimental, theoretical, and computational research methods [30]. This article provides detailed application notes and protocols for applying ML to property prediction, framed within the broader context of data-driven methods for material synthesis research. We focus on the evolution from classical supervised learning to sophisticated deep neural networks, with a particular emphasis on overcoming the pervasive challenge of data scarcity. The protocols herein are designed for an audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to implement these powerful techniques.

Technical Approaches and Comparative Analysis

The selection of an appropriate ML strategy is contingent upon the specific prediction task, the nature of the available data, and the molecular representation. The following section compares the predominant technical frameworks.

# Table 1: Comparison of ML Approaches for Property Prediction

| Approach | Core Principle | Key Advantages | Ideal Use Case | Representative Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) | Correlates hand-crafted molecular descriptors or fingerprints with a target property using statistical or ML models [31] [32]. | High interpretability; Lower computational cost; Effective with small datasets [31]. | Rapid prototyping and prediction for small organic molecules when data is limited [31]. | Inclusion of MD descriptors improves prediction, especially with <1000 data points [31]. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | End-to-end learning directly from graph representations of molecules (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges) [33] [31]. | Eliminates need for manual descriptor selection; Automatically learns relevant features [33]. | Capturing complex structure-property relationships in polymers and molecules with sufficient data [33]. | State-of-the-art for many molecular tasks; RMSE reduced by 28.39% for electron affinity with SSL [33]. |

| Self-Supervised Learning (SSL) with GNNs | Pre-trains GNNs on pseudo-tasks derived from unlabeled molecular graphs before fine-tuning on the target property [33]. | Dramatically reduces required labeled data; Learns universal structural features [33]. | Polymer and molecular property prediction in scarce labeled data domains [33]. | Decreases RMSE by 19.09-28.39% in scarce data scenarios vs. supervised GNNs [33]. |

| Physics-Informed Machine Learning | Integrates physics-based descriptors or constraints (e.g., from MD simulations) into ML models [31]. | Improved accuracy and interpretability; Leverages domain knowledge; Better generalization [31]. | Predicting properties like viscosity where intermolecular interactions are critical [31]. | QSPR models with MD descriptors reveal intermolecular interactions as most important for viscosity [31]. |

| Multi-Task Learning (MTL) | Simultaneously trains a single model on multiple related prediction tasks [34]. | Improved generalization by leveraging shared information across tasks; More efficient data use [34]. | Predicting multiple ADME properties for drugs or related material properties concurrently [34]. | Enables modeling of 25 ADME endpoints with shared representations; comparable performance for TPDs [34]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Self-Supervised GNNs for Polymer Property Prediction

This protocol adapts the methodology from Gao et al. for predicting polymer properties like electron affinity and ionization potential with limited labeled data [33].

1. Polymer Graph Representation:

- Objective: Convert a polymer structure into a stochastic graph representation.

- Steps:

- Represent each atom as a node and each bond as a pair of directed edges.

- Assign feature vectors to each node (atom type, etc.) and each directed edge.

- Incorporate stochastic weights on nodes and edges to represent features like monomer stoichiometry and chain architecture [33].

- Software: Implement using deep learning frameworks (PyTorch, TensorFlow) with cheminformatics libraries.

2. Self-Supervised Pre-training:

- Objective: Pre-train a GNN model to learn fundamental polymer structural features without property labels.

- Methods (to be used ensemble):

- Model Architecture: Use a Weighted Directed Message Passing Neural Network tailored for the polymer graph representation [33].

3. Supervised Fine-tuning: