Beyond Thermodynamics: Advanced AI and Machine Learning for Predicting Metastable Material Synthesizability

Accurately predicting which metastable materials can be synthesized is a critical bottleneck in accelerating the discovery of new functional materials for biomedical and technological applications.

Beyond Thermodynamics: Advanced AI and Machine Learning for Predicting Metastable Material Synthesizability

Abstract

Accurately predicting which metastable materials can be synthesized is a critical bottleneck in accelerating the discovery of new functional materials for biomedical and technological applications. This article explores the paradigm shift from traditional stability-based metrics to advanced data-driven approaches, including large language models (LLMs) and specialized machine learning (ML) frameworks. We cover the foundational challenges of defining synthesizability, detail cutting-edge methodologies like the Crystal Synthesis LLM (CSLLM) and co-training models, and address key hurdles such as data scarcity and model generalizability. A comparative analysis validates these new tools against conventional methods, demonstrating their superior accuracy in bridging the gap between theoretical prediction and experimental realization, ultimately guiding more efficient and targeted synthesis efforts.

The Synthesizability Challenge: Why Metastable Materials Defy Conventional Prediction

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why can't I rely solely on a material's formation energy to predict if it can be synthesized?

Formation energy, specifically the energy above the convex hull ( [1]), is a measure of thermodynamic stability, not synthesizability. While a negative formation energy indicates a material is stable relative to its elements, it does not account for critical experimental factors. Synthesizability is influenced by reaction kinetics, phase transformations, the availability of suitable precursors, and specific experimental conditions like temperature and pressure [1]. It is possible to have metastable materials with positive formation energies that are synthesizable, and stable materials that have not been synthesized due to kinetic barriers [2].

FAQ 2: What are the limitations of using phonon spectrum analysis to assess synthesizability?

Phonon spectrum analysis assesses kinetic stability by looking for imaginary frequencies that indicate structural instability [2]. However, a significant limitation is that material structures with imaginary phonon frequencies can still be synthesized [2]. Furthermore, this method is computationally expensive, making it impractical for high-throughput screening of thousands of candidate materials [1].

FAQ 3: How can machine learning models predict synthesizability more accurately than traditional thermodynamic methods?

Machine learning (ML) models learn the complex patterns of what makes a material synthesizable directly from large databases of known synthesized and non-synthesized materials [1] [3]. They can integrate various data types, including composition, crystal structure, and properties derived from both real and reciprocal space [1]. Unlike rigid rules like charge-balancing, ML models can implicitly learn chemical principles such as charge-balancing, chemical family relationships, and ionicity to make predictions [3]. For example, one ML model achieved 98.6% accuracy in synthesizability classification, significantly outperforming methods based on formation energy or phonon spectra [2].

FAQ 4: What is a common method for creating a dataset to train a synthesizability prediction model?

A common approach uses Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning [2] [3]. The steps are:

- Positive Examples: Collect experimentally confirmed synthesizable crystal structures from databases like the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [2] [3].

- Unlabeled (Negative) Examples: Generate a large set of hypothetical or theoretical crystal structures from sources like the Materials Project (MP) [2]. These are treated as "unlabeled" because, while most are likely non-synthesizable, some may be synthesizable but not yet discovered.

- Model Training: A machine learning model is trained to distinguish the positive examples from the unlabeled set, often by reweighting the unlabeled examples according to their likelihood of being synthesizable [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Failed Material Synthesis for Theoretically Stable Compounds

Problem: A material predicted to be thermodynamically stable (e.g., with a low energy above hull) cannot be synthesized in the lab.

Investigation and Resolution Steps:

Verify the Problem:

- Confirm that multiple synthesis attempts have been made, varying key parameters like temperature and reaction time.

- Use characterization techniques (e.g., X-ray diffraction) to confirm the target phase is absent and identify any alternative phases that may have formed instead.

Research and Form a Hypothesis:

- Research Precursors: Investigate if your chosen precursors are appropriate. A Large Language Model (LLM) specialized in precursor prediction can suggest viable alternatives [2].

- Check for Kinetic Barriers: The synthesis may be hindered by high kinetic barriers. Consult computational or experimental data on phase transformation energies or reaction pathways [1].

- Hypothesis Example: "The synthesis is failing because the solid-state reaction kinetics are too slow at the tested temperatures, or the chosen precursors form a stable intermediate phase that blocks the formation of the target material."

Develop and Execute a Game Plan [4]:

- Plan A - Modify Synthesis Method: If using a solid-state method, consider a solution-based route, or vice-versa. An LLM trained on synthetic methods can classify the most promising approach for your material [2].

- Plan B - Alternative Precursors: Source and test the alternative precursors identified during your research.

- Plan C - Adjust Parameters: Design experiments to systematically explore a wider range of temperatures, pressures, and reaction times.

Solve and Reproduce:

- Once a successful synthesis route is found, meticulously document all parameters.

- Repeat the synthesis to ensure the results are reproducible [4].

Guide 2: Troubleshooting High False Positive Rates in Virtual Material Screening

Problem: Your computational screening workflow, which uses thermodynamic stability as a filter, identifies a large number of candidate materials that later prove to be non-synthesizable.

Investigation and Resolution Steps:

Define the Problem:

- Quantify the false positive rate. How many of the predicted "stable" materials were attempted and failed synthesis?

- Analyze the composition or structure of the failed materials to see if they share common characteristics.

Isolate the Problem:

- The primary issue is likely the screening metric itself. Thermodynamic stability is an insufficient proxy for synthesizability [3].

Implement a Solution:

- Integrate a Synthesizability Filter: Incorporate a dedicated machine learning-based synthesizability model into your screening workflow after the initial stability filter.

- Model Selection: Choose a model that fits your needs. For example, the Synthesizability Score (SC) model using Fourier-transformed crystal properties (FTCP) achieved 82.6% precision for ternary crystals [1]. The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM) framework reports 98.6% accuracy [2].

- Validate the Workflow: Use a hold-out set of known materials to validate that the new combined workflow (Stability + Synthesizability filter) reduces false positives while retaining true positives.

Quantitative Data on Synthesizability Prediction Methods

The table below summarizes the performance of different methods for predicting material synthesizability.

Table 1: Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

| Prediction Method | Key Metric | Reported Performance | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formation Energy/Energy Above Hull [1] [2] | Thermodynamic Stability | ~50% of synthesized materials captured [3]; 74.1% accuracy [2] | Physically intuitive; widely available | Fails to capture kinetic and experimental factors |

| Phonon Spectrum Analysis [2] | Kinetic Stability (no imaginary frequencies) | 82.2% accuracy [2] | Assesses dynamic stability | Computationally expensive; some synthesizable materials have imaginary frequencies |

| Synthesizability Score (SC) Model [1] | Precision/Recall | 82.6% precision, 80.6% recall (ternary crystals) [1] | Uses structural information (FTCP representation) | Requires crystal structure as input |

| SynthNN [3] | Precision | 7x higher precision than formation energy [3] | Composition-based; no structure required | Cannot differentiate between polymorphs |

| Crystal Synthesis LLM (CSLLM) [2] | Accuracy | 98.6% accuracy [2] | Very high accuracy; can also predict methods and precursors | Requires a text representation of the crystal structure |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Synthesizability Screening with FTCP and Deep Learning

This methodology details the process of predicting a synthesizability score (SC) for new inorganic crystal materials [1].

1. Data Collection and Preprocessing: * Data Sources: Query crystal structures and their properties from databases like the Materials Project (MP) and the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD). * Ground Truth Labeling: Use the ICSD tag in the MP database as a label for synthesizability. * Dataset Split: For robust validation, train the model on data from before a certain date (e.g., pre-2015) and test on materials added after that date (e.g., post-2019).

2. Crystal Structure Representation: * Representation: Transform the crystal structures into a Fourier-Transformed Crystal Properties (FTCP) representation [1]. * Process: This method represents crystals in both real space and reciprocal space. Real-space features are constructed, and reciprocal-space features are formed using elemental property vectors and a discrete Fourier transform.

3. Model Training and Prediction: * Model Architecture: A deep learning classifier (e.g., a Convolutional Neural Network-based encoder) is used. * Input: The FTCP representation of the crystal structure. * Output: A binary classification or a synthesizability score (SC). Materials with a high SC are predicted to be synthesizable.

4. Validation: * Validate model performance using standard metrics like precision and recall on the held-out test set. A true positive rate of 88.60% was achieved on a post-2019 dataset [1].

Protocol 2: Predicting Synthesizability and Precursors Using Large Language Models

This protocol uses the Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models (CSLLM) framework for end-to-end synthesis planning [2].

1. Data Curation: * Positive Data: Curate a set of synthesizable crystal structures from the ICSD, applying filters (e.g., maximum of 40 atoms, no disordered structures). * Negative Data: Use a pre-trained PU learning model to assign a "crystal-likeness" score (CLscore) to a large pool of theoretical structures from multiple databases. Select structures with the lowest scores (e.g., CLscore <0.1) as non-synthesizable examples.

2. Text Representation of Crystals: * Develop a concise text representation, a "material string", that includes space group, lattice parameters, and atomic species with their Wyckoff positions. This format is more efficient for LLMs than CIF or POSCAR files.

3. Fine-Tuning LLMs: * Synthesizability LLM: Fine-tune a foundational LLM on the curated dataset to classify a material as synthesizable or not. * Method LLM: Fine-tune a separate LLM to classify the most likely synthetic method (e.g., solid-state or solution). * Precursor LLM: Fine-tune a third LLM to identify suitable solid-state synthetic precursors for binary and ternary compounds.

4. Prediction and Validation: * Input the "material string" of a candidate material into the fine-tuned CSLLM framework. * The framework outputs the synthesizability prediction, suggested method, and potential precursors. The Method LLM and Precursor LLM achieved 91.0% classification accuracy and 80.2% precursor prediction success, respectively [2].

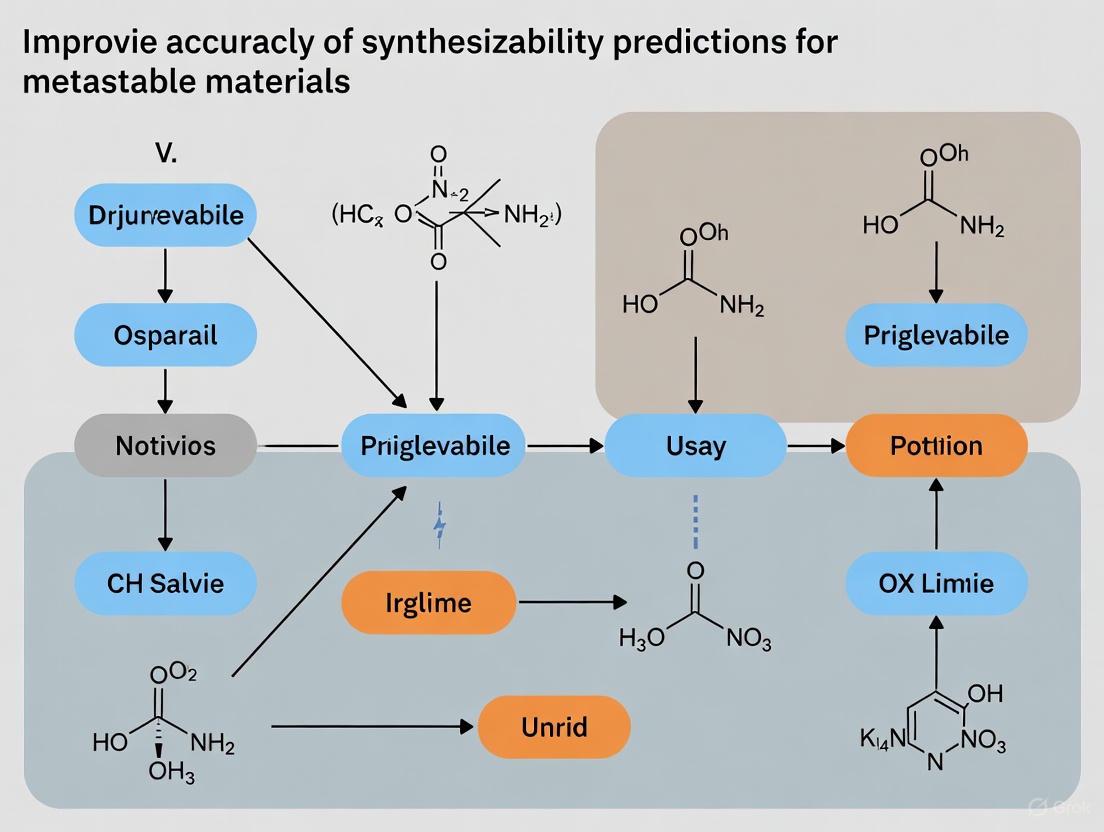

Experimental Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Traditional vs. ML-Enhanced Screening Workflow

LLM-Driven Synthesis Planning Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools and Databases for Synthesizability Research

| Tool/Database Name | Type | Primary Function in Synthesizability Research |

|---|---|---|

| Materials Project (MP) [1] [2] | Database | Provides calculated thermodynamic data (e.g., formation energy, energy above hull) and crystal structures for a vast number of inorganic materials. |

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [1] [2] [3] | Database | The primary source for experimentally confirmed, synthesizable crystal structures. Used as "ground truth" positive data for training ML models. |

| Fourier-Transformed Crystal Properties (FTCP) [1] | Crystal Representation | A method to represent crystal structures in both real and reciprocal space for machine learning, capturing periodicity and elemental properties. |

| Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Network (CGCNN) [1] | Machine Learning Model | A graph-based neural network designed for learning material properties directly from crystal structures. |

| Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM) [2] | Machine Learning Model | A framework of fine-tuned LLMs that predict synthesizability, synthetic methods, and precursors from a text representation of a crystal structure. |

| Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning [2] [3] | Machine Learning Technique | A semi-supervised learning approach to handle datasets where only positive (synthesizable) examples are reliably known, and negative examples are unlabeled. |

| Parvodicin C1 | Parvodicin C1, MF:C83H88Cl2N8O29, MW:1732.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| c-di-AMP diammonium | c-di-AMP diammonium, MF:C20H30N12O12P2, MW:692.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Welcome to the Synthesizability Prediction Support Center

This resource provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers navigate the complex challenge of predicting material synthesizability, with a special focus on the limitations of traditional stability metrics for metastable materials.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is a material with a negative formation energy sometimes still unsynthesizable?

A negative formation energy indicates thermodynamic stability but does not guarantee synthesizability. Kinetic barriers and experimental constraints often prevent realization [1]. Key reasons include:

- High Kinetic Barriers: The activation energy required to form the material from common precursors may be prohibitively high, even if the final state is stable [5].

- Lack of Viable Synthesis Pathway: No known method or accessible thermodynamic condition exists to navigate from available starting materials to the target crystal structure [6].

- Technological Limitations: The synthesis might require extreme conditions (e.g., exceptionally high pressures or temperatures) not available in standard labs [5].

FAQ 2: My hypothetical material has no imaginary phonon modes, suggesting kinetic stability. Why might it still be unsynthesizable?

The absence of imaginary phonon modes is a necessary but not sufficient condition for synthesizability [1]. Other critical factors include:

- Competing Metastable Phases: Multiple polymorphs with similar energy levels may exist, and the synthesis conditions may favor a different metastable phase than your target [1] [6].

- Precursor Availability and Reactivity: The necessary solid-state precursors may not be available, or their reaction pathways may lead to different decomposition products [2].

- The "Synthesisability" Gap: A material can be thermodynamically and kinetically stable in its final form yet remain "un-makeable" due to the complexities of the synthesis process itself [5].

FAQ 3: What are the most accurate modern methods for predicting synthesizability?

Machine learning (ML) models trained on experimental data significantly outperform traditional stability proxies. Advanced frameworks include:

- Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models (CSLLM): This framework uses LLMs fine-tuned on a massive dataset of synthesizable and non-synthesizable crystals, achieving 98.6% prediction accuracy and can also suggest synthetic methods and precursors [2].

- SynCoTrain: A semi-supervised, dual-classifier model that uses co-training to reduce model bias. It employs Positive and Unlabeled (PU) learning to handle the scarcity of negative data (failed synthesis attempts) [5].

- Synthesizability Score (SC) Models: Deep learning models using advanced crystal structure representations (like Fourier-transformed crystal properties) can achieve over 80% precision and recall in identifying synthesizable ternary crystals [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Synthesizability Prediction

| Problem | Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Over-reliance on Formation Energy | Mistaking thermodynamic stability for synthesizability; ignoring kinetic and experimental factors [1] [5]. | Use formation energy as an initial filter, not a final verdict. Supplement with ML-based synthesizability predictors (e.g., CSLLM, SynCoTrain) [5] [2]. |

| No Clear Synthesis Pathway | The target material is a local minimum on the energy landscape with high barriers to formation from common precursors [5] [6]. | Employ precursor prediction models. The CSLLM Precursor LLM can identify suitable solid-state precursors with 80.2% success rate [2]. |

| Uncertainty with Metastable Targets | Traditional phase diagrams and hull distances do not account for kinetically trapped, high-energy phases [6]. | Focus on ML models specifically designed for metastability, which learn from existing metastable materials in databases like the ICSD [5] [2]. |

| Lack of Negative Data | Failed synthesis attempts are rarely published, making it difficult for ML models to learn the decision boundary for "unsynthesizable" [5]. | Utilize models that implement PU-Learning, which are designed to learn from positive examples (ICSD) and a large set of unlabeled data (theoretical structures) [5] [2]. |

Quantitative Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

The table below summarizes the performance of various approaches, highlighting the superior accuracy of modern data-driven methods.

| Prediction Method | Core Principle | Reported Accuracy / Performance | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formation Energy / Energy Above Hull | Thermodynamic stability relative to competing phases [1]. | ~74.1% accuracy [2]. | Fails for synthesizable metastable materials; ignores kinetics and synthesis conditions [5]. |

| Phonon Stability | Absence of imaginary frequencies indicates dynamic (kinetic) stability [2]. | ~82.2% accuracy [2]. | Computationally expensive; structures with imaginary frequencies can still be synthesized [2]. |

| Synthesizability Score (SC) Model | Deep learning on crystal representations (FTCP) from materials databases [1]. | 82.6% precision, 80.6% recall [1]. | Performance depends on the quality and breadth of the underlying training data. |

| SynCoTrain (PU-Learning) | Dual-classifier co-training (ALIGNN & SchNet) to mitigate model bias [5]. | High recall on test sets; effective for oxides [5]. | Model performance can vary across different material families. |

| CSLLM Framework | Large Language Models fine-tuned on a balanced dataset of crystal structures [2]. | 98.6% accuracy for synthesizability classification [2]. | Requires a text-based representation of the crystal structure; complex model architecture. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Modern Synthesizability Workflow

This protocol outlines the steps to integrate ML-based synthesizability prediction into a high-throughput materials discovery pipeline.

Objective: To accurately screen theoretical crystal structures for synthesizability potential using the CSLLM framework and identify suitable precursors.

Materials and Computational Tools:

- Hardware: Standard computational workstation.

- Software: Python environment, CSLLM interface [2].

- Input Data: Crystal structure files (e.g., CIF, POSCAR) of candidate materials.

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Convert your crystal structure files into the "material string" text representation. This format condenses essential crystal information (space group, lattice parameters, atomic species, Wyckoff positions) into a concise, LLM-readable string [2].

- Synthesizability Classification: Input the material strings into the fine-tuned Synthesizability LLM. The model will classify each structure as "synthesizable" or "non-synthesizable" with high accuracy [2].

- Synthesis Route Identification: For structures predicted to be synthesizable, use the Method LLM to classify the most probable synthetic method (e.g., solid-state or solution-based) [2].

- Precursor Selection: For solid-state synthesis routes, utilize the Precursor LLM to identify the most likely solid-state precursor compounds required for the reaction [2].

- Validation and Downstream Analysis: For high-priority candidates, proceed with targeted first-principles calculations (e.g., phase stability, property prediction) to finalize the selection for experimental pursuit.

Research Reagent Solutions: Key Computational Tools

This table details the essential "research reagents"—the computational models and datasets—required for advanced synthesizability prediction.

| Item Name | Function / Description | Application in Synthesizability |

|---|---|---|

| CSLLM Framework | A suite of three fine-tuned Large Language Models for predicting synthesizability, method, and precursors [2]. | Provides an all-in-one tool for end-to-end synthesis planning for theoretical crystals. |

| SynCoTrain Model | A dual-classifier model using SchNet and ALIGNN for robust predictions on oxide materials [5]. | Reduces model bias through co-training; ideal for predicting synthesizability within a specific material class. |

| Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning | A machine learning technique that learns from confirmed synthesizable structures (ICSD) and a large set of unlabeled theoretical structures [5] [2]. | Addresses the critical lack of published negative data (failed syntheses). |

| Fourier-Transformed Crystal Properties (FTCP) | A crystal representation that includes information in both real and reciprocal space for machine learning [1]. | Provides a rich descriptor of crystal structures for deep learning models predicting synthesizability scores. |

| Crystal-Likeness Score (CLscore) | A metric generated by a pre-trained PU learning model to identify non-synthesizable structures [2]. | Used to curate high-quality negative datasets for training advanced models like CSLLM. |

Workflow: Modern Synthesizability Prediction

This diagram illustrates the integrated workflow that combines traditional stability checks with modern ML-based synthesizability prediction.

The SynCoTrain Co-Training Mechanism

This diagram details the architecture of the SynCoTrain model, which uses a dual-classifier approach to improve prediction reliability.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Metastable Phase Instability During Synthesis

Problem: The target metastable phase decomposes or transforms into a stable phase during synthesis.

| Problem Cause | Diagnostic Signs | Solution | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excessive thermal budget [6] | Phase analysis (XRD) shows stable phase peaks. | Lower annealing temperature/shorten duration; use rapid thermal annealing (RTA). | Use kinetic inhibitors (dopants) to slow atomic diffusion [6]. |

| Incorrect precursor selection [7] | Reaction yields multiple phases; failure to form target compound. | Use precursors with lower reaction activation energy; consider reactive precursors. | Consult literature/LLM precursor prediction tools for suitable precursors [2] [8]. |

| Insufficient driving force | Failure to form high-energy metastable phase. | Employ non-equilibrium methods (thin-film strain, mechanochemistry) [6] [9]. | Apply large undercooling, chemical pressure, or epitaxial strain during nucleation [6]. |

Guide 2: Low Yield or Poor Reproducibility in Solid-State Synthesis

Problem: Inconsistent results or low yield when synthesizing metastable ternary oxides.

| Problem Cause | Diagnostic Signs | Solution | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inhomogeneous precursor mixing | Inconsistent product composition between batches. | Improve mixing: use ball milling, sol-gel, or co-precipitation methods [7]. | Use nanostructured or coprecipitated precursors for better cation mixing [7]. |

| Suboptimal heating profile | Incorrect phase or poor crystallinity. | Optimize heating rate, dwell temperature/time; use multi-step calcination [7]. | Use a controlled ramp rate; determine optimal temperature via DTA/TGA. |

| Uncontrolled atmosphere | Non-stoichiometric oxygen content; secondary phases. | Control oxygen partial pressure during synthesis and cooling [7]. | Use sealed tubes or controlled atmosphere furnaces for oxygen-sensitive materials. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What distinguishes a metastable phase from a thermodynamically stable one? A metastable phase exists in a state of higher Gibbs free energy than the global equilibrium (stable) phase but is kinetically trapped [6]. It persists due to an energy barrier that prevents its transformation to the stable state. In contrast, a thermodynamically stable phase has the lowest possible free energy for the given conditions.

FAQ 2: Why are traditional metrics like "energy above hull" insufficient for predicting synthesizability?

The energy above the convex hull (E_hull) is a thermodynamic metric calculated at 0 K [7]. It does not account for kinetic barriers, the influence of temperature and pressure, or synthesis pathway complexities [2] [7]. Many materials with low E_hull remain unsynthesized, while many metastable materials (E_hull > 0) are successfully made [2] [8] [7].

FAQ 3: How can I predict suitable precursors for a target metastable phase? Traditional methods rely on experimental literature and phase diagrams. Now, AI models, particularly Large Language Models (LLMs) fine-tuned on materials science data, can predict solid-state precursors from the crystal structure with high accuracy (e.g., >80% success for binary/ternary compounds) [2] [8]. These models learn from vast synthesis databases to suggest viable precursor combinations.

FAQ 4: What is "thermodynamic-kinetic adaptability" in metastable phase catalysis? This concept describes how metastable phases can adapt their geometric and electronic structures during reactions [6]. They optimize interaction with reactant molecules, tune reaction barriers (e.g., by shifting the d-band center), and thereby accelerate reaction kinetics more effectively than their stable counterparts [6].

FAQ 5: Can AI accurately predict if a hypothetical crystal structure is synthesizable? Yes. Advanced frameworks like Crystal Synthesis LLMs (CSLLM) can predict the synthesizability of arbitrary 3D crystal structures with high accuracy (e.g., 98.6%), significantly outperforming screening methods based on energy above hull (74.1%) or phonon instability (82.2%) [2]. These models consider complex structural and compositional patterns beyond simple stability metrics.

Data Presentation: Synthesizability Prediction Methods

The table below compares quantitative performance of different methods for predicting material synthesizability.

Table 1: Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Methods for Inorganic Crystals

| Prediction Method | Core Principle | Key Metric(s) | Reported Accuracy / Performance | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Above Hull (Ehull) [7] | Thermodynamic stability relative to decomposition phases. | Formation energy (eV/atom). | 74.1% accuracy [2] | Fails for many metastable phases; ignores kinetics and conditions [2] [7]. |

| Phonon Stability (Imaginary Frequencies) [2] | Dynamic (kinetic) stability of the crystal lattice. | Lowest phonon frequency (THz). | 82.2% accuracy [2] | Structures with imaginary frequencies can be synthesized; computationally expensive [2]. |

| Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning [2] [7] | Machine learning on known synthesized (positive) and hypothetical (unlabeled) materials. | CLscore, PU-classifier score. | 87.9% - 92.9% accuracy [2] | Lack of true negative data makes evaluation difficult [7]. |

| Crystal Synthesis LLM (CSLLM) [2] | Large Language Model fine-tuned on text representations of crystal structures. | Classification Accuracy. | 98.6% accuracy [2] | Requires fine-tuning; performance depends on training data quality. |

| LLM Embedding + PU Classifier [8] | Uses LLM-generated text embeddings of structures as input for a PU-learning model. | True Positive Rate (Recall), Precision. | Outperforms StructGPT- FT and PU-CGCNN [8] | More complex pipeline than a single fine-tuned LLM. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Solid-State Synthesis of a Metastable Ternary Oxide

This protocol outlines the synthesis of a metastable ternary oxide, such as those explored in human-curated studies [7].

1. Precursor Preparation

- Select Precursors: Typically, solid powders of binary oxides or carbonates (e.g.,

BaCO3,TiO2). Prediction tools can aid selection [2]. - Weighing: Accurately weigh precursors according to the target compound's stoichiometry.

- Grinding/Mixing: Use an agate mortar and pestle or a ball mill to mix powders thoroughly for 30-60 minutes. For better homogeneity, perform wet grinding with a volatile solvent like ethanol, which is later evaporated [7].

2. Calcination

- Crucible Selection: Place the mixed powder in a high-temperature crucible (e.g., alumina, platinum).

- Initial Heat Treatment: Heat in a box furnace in air. Use a heating rate of

3-5 °C/minto a temperature below the final reaction temperature (e.g.,100-200 °Clower) for5-12 hoursto facilitate initial solid-state diffusion and decarbonation. - Intermediate Grinding: After cooling, regrind the powder to ensure homogeneity and break up sintered aggregates.

3. Sintering and Reaction

- Final Pelletizing: Press the reground powder into pellets under uniaxial pressure (

~5 tons) to improve inter-particle contact. - High-Temperature Reaction: Heat the pellets in the furnace at the optimal synthesis temperature (e.g.,

1000-1400 °Cfor many oxides) for12-48 hours[7]. The atmosphere (air, oxygen, argon) may be controlled. - Cooling Protocol: Cool the product to room temperature, typically inside the turned-off furnace (furnace cooling). For phases requiring specific quenching, remove the sample and cool rapidly on a cold metal block.

4. Product Characterization

- Verify phase purity and identity using X-ray Diffraction (XRD).

- Analyze morphology and composition using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) with Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS).

Protocol 2: Stabilizing a Metastable Phase via Thin-Film Epitaxial Strain

This protocol describes creating a metastable phase in classic materials like barium titanate by applying epitaxial strain [9].

1. Substrate Selection and Preparation

- Select a Crystalline Substrate: Choose a substrate with a lattice parameter slightly mismatched with the bulk stable phase of the target material (e.g.,

GdScO3forBaTiO3). - Substrate Cleaning: Clean the substrate using standard procedures (e.g., ultrasonic cleaning in acetone, isopropanol) and potentially with a high-temperature pre-anneal or plasma cleaning to ensure an atomically clean surface.

2. Thin-Film Deposition

- Deposition Technique: Use Pulsed Laser Deposition (PLD) or Molecular Beam Epitaxy (MBE) for atomic-level control.

- Deposition Conditions: Maintain a high substrate temperature (

500-800 °C) and a controlled oxygen partial pressure (~10^-5 - 10^-2 mbar) during deposition. - Growth Monitoring: Use in-situ techniques like Reflection High-Energy Electron Diffraction (RHEED) to monitor the growth mode and crystal quality in real-time.

3. Post-Deposition Processing and Characterization

- In-situ Annealing: Anneal the as-grown film in an oxygen-rich atmosphere at the growth temperature to ensure proper oxygenation and crystallinity.

- Cooling: Cool the film slowly under oxygen pressure to minimize defects.

- Structural Characterization: Use X-ray Diffraction (XRD), including

θ-2θscans and reciprocal space mapping, to confirm the epitaxial strain and the resulting metastable crystal structure [9]. - Functional Property Measurement: Use techniques like spectroscopic ellipsometry or electrical measurement systems to characterize the enhanced electro-optic or other functional properties of the metastable phase [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Metastable Materials Synthesis

| Item | Function & Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Oxide/Carbonate Precursors | Serve as cation sources in solid-state reactions; high purity minimizes side reactions. | BaCO3 and TiO2 for synthesizing BaTiO3 [7]. |

| Single-Crystal Epitaxial Substrates | Provide a template for growing strained thin films, stabilizing metastable phases. | GdScO3 substrate for growing metastable BaTiO3 films [9]. |

| Kinetic Inhibitor Dopants | Additives that slow down atomic diffusion, kinetically trapping a metastable phase. | Adding dopants to slow the transformation from metastable to stable phase [6]. |

| Large Language Models (LLMs) for Materials | AI tools to predict synthesizability, synthetic methods, and precursors from structure [2] [8]. | Using the CSLLM framework to screen hypothetical structures for synthesizability [2]. |

| Hederacoside D | Hederacoside D, MF:C53H86O22, MW:1075.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ampelopsin F | Ampelopsin F, MF:C28H22O6, MW:454.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow Visualization

This technical support center addresses two fundamental data challenges that impact the accuracy of synthesizability predictions in metastable materials research: the scarcity of negative examples (unsuccessful synthesis attempts) and publication bias (the preferential publication of positive results). These issues can skew machine learning models and experimental databases, leading to inaccurate predictions and wasted research resources. The following guides and FAQs provide practical solutions for researchers and scientists to mitigate these problems.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Mitigating the Impact of Scarce Negative Data

Problem Statement: Machine learning models for predicting synthesizability demonstrate poor performance because they are trained almost exclusively on positive examples (successfully synthesized materials), with very few confirmed negative examples (unsynthesizable materials) [3] [5].

Diagnosis Questions:

- Is your model's recall high but precision low? This is a classic symptom of a model trained without robust negative examples, causing it to incorrectly label many unsynthesizable materials as synthesizable [3].

- Are you relying on imperfect proxies for negative data? Using thermodynamic stability (e.g., formation energy, distance from convex hull) as a sole proxy for synthesizability is insufficient, as it ignores kinetic stabilization and technological constraints, leading to misclassification of metastable phases [5] [10].

Solutions & Methodologies:

Implement Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning: This semi-supervised approach treats the problem as having a set of confirmed positive data (synthesized materials from databases like ICSD or MP) and a large set of unlabeled data (hypothetical materials). The model learns to identify synthesizable patterns from the positives and iteratively refines its understanding from the unlabeled set [3] [5].

- Protocol (SynthNN-style): Reformulate the discovery task as a synthesizability classification. Use a deep learning model (e.g., atom2vec) that learns optimal material representations directly from the distribution of synthesized compositions, without requiring prior chemical knowledge or structural information [3].

- Protocol (SynCoTrain-style): Employ a co-training framework with two complementary graph neural networks (e.g., SchNet and ALIGNN). The models iteratively exchange predictions on unlabeled data to mitigate individual model bias and improve generalizability [5].

Generate Realistic Artificial Negatives: Create a dataset of artificially generated, unsynthesized material compositions to augment your training data. The ratio of artificial to synthesized formulas is a key hyperparameter (e.g., ( {N}_{{\rm{synth}}} )) to tune [3].

Guide 2: Identifying and Correcting for Publication Bias

Problem Statement: The scientific literature systematically overrepresents positive findings (successful syntheses) because studies with statistically significant results are more likely to be submitted and published [11] [12]. This skews the available data and the perceived credibility of research hypotheses.

Diagnosis Questions:

- Does your literature survey for a specific material family show a near-absence of negative or null results? In some fields, over 89% of published studies report positive associations, with some sub-fields reporting 100% positive results [12].

- Is there a preponderance of small studies with large effect sizes in meta-analyses? This can indicate that smaller, less rigorous studies with positive results are being published, while smaller studies with negative results are not [11].

Solutions & Methodologies:

Assess the Risk of Publication Bias in Meta-Analyses:

- Use Funnel Plots with Caution: Visually inspect funnel plots for asymmetry, where smaller studies show more scatter and larger studies cluster at the top. However, this method is subjective and unreliable on its own [11].

- Apply Statistical Tests: Use tests like Egger's regression to statistically assess funnel plot asymmetry. Be aware that these tests are underpowered with fewer than ten studies and asymmetry can be caused by factors other than publication bias (e.g., heterogeneity between studies) [11].

- Terminology Shift: Always refer to the "risk of publication bias" rather than stating its definitive presence, as it is very difficult to prove conclusively [11].

Implement Preventive Strategies: The most efficient solution is to prevent bias at the source.

- Pre-registration: Pre-register study protocols and analysis plans to reduce selective outcome reporting.

- Registered Reports: Submit study designs for peer review prior to data collection, with in-principle acceptance based on the methodology, not the results.

- Report All Findings: Commit to publishing all study results, regardless of the outcome's direction or statistical significance [11].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why can't I just use thermodynamic stability as a reliable proxy for synthesizability?

Thermodynamic stability is only one component of synthesizability. A material's synthetic accessibility is also governed by:

- Kinetic Factors: Metastable materials can be kinetically stabilized despite not being the thermodynamic ground state [5] [10].

- Technological Constraints: A material may be thermodynamically stable but unsynthesizable with current methods or equipment (e.g., requiring extreme pressures) [5].

- Data shows poor correlation: Traditional heuristics like charge-balancing fail to classify over 60% of known synthesized ionic compounds, demonstrating the inadequacy of simple proxies [3] [5].

FAQ 2: My model for synthesizability prediction performs well on training and test data, but fails to guide successful synthesis in the lab. What is wrong?

This is a classic sign of the generalization challenge, exacerbated by model bias and the data problems discussed here.

- Model Bias: A single model architecture may inherently overfit to the specific distribution of your training data and perform poorly on out-of-sample, real-world data [5].

- Solution: Use a co-training framework (e.g., SynCoTrain) that leverages multiple models with different inductive biases. This collaborative approach is more likely to generalize effectively to novel, unseen materials [5].

FAQ 3: How can I quantitatively assess the potential impact of publication bias on my literature-based hypothesis?

You can estimate the post-test credibility of a hypothesis using a framework analogous to diagnostic testing.

- Key Metric: Evaluate the Positive Predictive Value (PPV), which is the probability a relationship is true given a positive test (a significant published result). The formula

(1-β) Ï > αmust hold for the PPV to be greater than 50%, where:(1-β)is the statistical power.Ïis the a priori probability of the hypothesis being true.αis the significance level (type I error).

- Interpretation: In many research fields, the a priori probability (

Ï) and statistical power are low. This means that even with a low p-value, many published positive findings are more likely to be false than true, a situation severely worsened by publication bias [12].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

| Method / Model | Key Principle | Reported Advantage / Performance |

|---|---|---|

| SynthNN [3] | Deep learning classification using the entire space of synthesized compositions. | 7x higher precision than DFT-calculated formation energies; outperformed 20 human experts with 1.5x higher precision. |

| SynCoTrain [5] | Dual-classifier co-training framework (ALIGNN & SchNet) with PU learning. | Mitigates model bias; demonstrates robust performance and high recall on test sets for oxide crystals. |

| Charge-Balancing [3] | Heuristic based on net neutral ionic charge. | Poor performance: only 37% of known synthesized materials are charge-balanced. |

| Stability Network [3] | Machine learning combining formation energy and discovery timeline. | A previously developed method for synthesizability predictions. |

Table 2: Publication Bias and Data Scarcity Statistics

| Problem | Statistic / Finding | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Publication Bias | Frequency of papers declaring significant statistical support for hypotheses increased by 22% between 1990 and 2007. | [12] |

| Publication Bias | In some biomedical research fields (e.g., oxidative stress in ASD), 100% of 115 studies reported positive results. | [12] |

| Negative Data Scarcity | Only about 23% of known binary cesium compounds are charge-balanced, highlighting the inadequacy of a common heuristic. | [3] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning for Synthesizability Classification

Data Acquisition:

- Positive Data: Extract compositions and/or crystal structures of synthesized inorganic materials from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) or the Materials Project (MP) [3] [5].

- Unlabeled Data: Use a large set of hypothetical, computationally generated material compositions or structures (e.g., from high-throughput DFT calculations or generative models) [3].

Model Training (SynthNN methodology):

- Input Representation: Use an atom embedding matrix (e.g., atom2vec) to represent each chemical formula. This allows the model to learn optimal feature representations directly from the data [3].

- Semi-Supervised Learning: Train a deep neural network classifier on the positive and unlabeled datasets. The algorithm probabilistically reweights unlabeled examples based on their likelihood of being synthesizable [3].

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Tune the ratio of artificially generated unsynthesized formulas to synthesized formulas (

N_synth) [3].

Model Training (SynCoTrain methodology):

- Dual-Classifier Setup: Initialize two different graph convolutional neural networks, such as ALIGNN (encodes bonds and angles) and SchNet (uses continuous-filter convolutions) [5].

- Co-Training Loop: Each classifier is trained on the labeled positive data. They then predict labels for a subset of the unlabeled data. The most confident predictions from each classifier are used to expand the training set for the other classifier in an iterative process [5].

- Prediction: The final synthesizability label is determined by averaging the predictions from both models [5].

Workflow Visualization

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Synthesizability Research

| Item / Solution | Function | Relevance to the Data Problem |

|---|---|---|

| ICSD / MP Database [3] [5] | Primary sources of confirmed positive data (synthesized material structures and compositions). | Provides the foundational "Positive" set required for PU Learning and model training. |

| PU Learning Algorithm [3] [5] | A semi-supervised machine learning paradigm designed to learn from Positive and Unlabeled data. | Directly addresses the scarcity of confirmed negative examples by not requiring them. |

| Co-training Framework (SynCoTrain) [5] | A methodology using two complementary models to iteratively label data and reduce bias. | Mitigates model bias, improving generalizability and reliability of predictions for novel materials. |

| Graph Neural Networks (ALIGNN, SchNet) [5] | Model architectures that encode crystal structures as graphs for property prediction. | Enables structure-based synthesizability prediction, which is more informative than composition-based models [10]. |

| Symmetry-Guided Structure Derivation [10] | Generates candidate structures from synthesized prototypes using group-subgroup relations. | Creates chemically plausible candidate spaces for screening, bridging the gap between theory and experiment. |

AI-Driven Solutions: From LLMs to Graph Networks for Synthesizability Prediction

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the CSLLM framework and what is its primary achievement? The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models (CSLLM) framework is a specialized AI system designed to predict the synthesizability of 3D crystal structures, suggest possible synthetic methods, and identify suitable precursors. Its primary achievement is an ultra-accurate 98.6% accuracy in predicting synthesizability, significantly outperforming traditional methods based on thermodynamic stability (74.1% accuracy) and kinetic stability (82.2% accuracy) [2] [13].

Q2: What specific problems does CSLLM solve in metastable materials research? CSLLM directly addresses the critical gap between a material's predicted thermodynamic or kinetic stability and its actual synthesizability. Many metastable structures, which have less favorable formation energies, can be synthesized, while numerous thermodynamically stable structures have not been realized. CSLLM bridges this gap, providing direct guidance for the experimental synthesis of novel metastable materials [2].

Q3: What are the three core components of the CSLLM framework? The framework consists of three fine-tuned large language models, each dedicated to a specific task [2]:

- Synthesizability LLM: Predicts whether an arbitrary 3D crystal structure is synthesizable.

- Method LLM: Classifies the possible synthesis method (e.g., solid-state or solution).

- Precursor LLM: Identifies suitable solid-state synthetic precursors for binary and ternary compounds.

Q4: How does the Precursor LLM perform, and what supports its predictions? The Precursor LLM has an 80.2% success rate in predicting synthesis precursors. To validate and enrich its suggestions, the framework also calculates reaction energies and performs combinatorial analysis to propose additional potential precursors [2].

Q5: What is a "material string" and why is it important for CSLLM? A "material string" is a novel, efficient text representation for crystal structures developed for the CSLLM framework. It integrates essential crystal information—space group, lattice parameters, atomic species, and Wyckoff positions—in a concise, reversible format. This representation is crucial for fine-tuning the LLMs as it reduces redundancy present in CIF or POSCAR files and provides the models with a structured text input they can process effectively [2].

Troubleshooting Common CSLLM Experimental Issues

Q1: The model is ignoring its tool for predicting precursors. What could be wrong? This is a common issue when deploying LLM-based agents. Potential causes and solutions include [14]:

- Context Overload: If your system has many tools enabled, the LLM's context window may be overwhelmed. Solution: Curate your toolkit, providing only the tools necessary for the specific precursor prediction task.

- Poor Prompt Specificity: Vague prompts lead to vague results. Solution: Be explicit in your prompt. Instead of "Analyze this structure," use "Use the

precursor_prediction_toolon the provided crystal structure to identify suitable solid-state precursors." - Malformed Tool Calls: The LLM might generate an incorrectly formatted request for the tool. Solution: Enable debug modes in your framework (e.g., LangSmith) to inspect the raw tool call output and check for JSON formatting errors [14].

Q2: How can I resolve CUDA out-of-memory errors when running the CSLLM models? Memory constraints are frequent when working with large models. To mitigate this [15]:

- Model Quantization: Apply quantization techniques using libraries like Hugging Face's Optimum or vLLM to reduce model weights from 32-bit to 16-bit or 8-bit precision, significantly lowering VRAM usage.

- Reduce Context Length: Truncate input sequences or process long material strings in smaller chunks.

- Hardware Selection: Ensure you are using a GPU with sufficient VRAM. A rough guideline is that a 70B parameter model requires approximately 140GB of VRAM for inference at FP16 precision [15].

Q3: What can I do if the model's synthesizability prediction seems inaccurate or "hallucinated"? To improve reliability and reduce hallucinations, ensure your input data is correctly formatted and consider augmenting the system [16]:

- Validate Input Format: Double-check that your crystal structure is correctly converted into the "material string" format, with all lattice parameters, atomic species, and Wyckoff positions accurately specified [2].

- Implement Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG): Augment the CSLLM with an external knowledge base of known crystal structures and their synthesizability. This allows the model to retrieve relevant, factual data before generating a prediction, grounding its responses in real-world information [16].

Q4: The model fails to generate a valid output for a complex crystal structure with a large unit cell. What steps should I take?

- Check Complexity Limits: The CSLLM was trained on structures with a maximum of 40 atoms and seven different elements. Verify that your input structure does not exceed these complexity bounds [2].

- Assess Generalization: The model has demonstrated 97.9% accuracy on complex structures with large unit cells, but performance can vary. Test the model on a set of simpler, known structures to verify its baseline functionality [2].

- Inspect System Logs: Use tracing tools (e.g., LangSmith) to monitor the model's internal reasoning process and identify where the workflow fails for complex inputs [14].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Core Synthesizability Prediction Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the primary workflow for using the CSLLM framework to predict crystal synthesizability.

Dataset Construction Methodology

A key to CSLLM's performance is its comprehensive training dataset. The protocol for constructing this dataset is as follows [2]:

Positive Sample Collection:

- Source: The Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD).

- Criteria: Select 70,120 experimentally reported crystal structures.

- Filtering: Include only ordered structures with ≤40 atoms and ≤7 different elements. Exclude all disordered structures.

Negative Sample Screening:

- Source Pool: Aggregate 1,401,562 theoretical structures from the Materials Project (MP), Computational Materials Database (CMDB), Open Quantum Materials Database (OQMD), and JARVIS database.

- Screening Model: Utilize a pre-trained Positive-Unlabeled (PU) learning model to calculate a CLscore for each structure.

- Selection: Identify 80,000 structures with the lowest CLscores (CLscore < 0.1) as high-confidence non-synthesizable examples.

Dataset Validation:

- Compute CLscores for the positive samples; 98.3% scored above the 0.1 threshold, validating the dataset's balance and integrity.

Table: Composition of the CSLLM Training Dataset

| Sample Type | Data Source | Selection Criteria | Final Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synthesizable (Positive) | ICSD | Ordered structures, ≤40 atoms, ≤7 elements | 70,120 |

| Non-Synthesizable (Negative) | MP, CMDB, OQMD, JARVIS | CLscore < 0.1 from PU learning model | 80,000 |

| Total Dataset Size | 150,120 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Essential Components of the CSLLM Framework and their Research Functions

| Item / Component | Function in the Research Framework |

|---|---|

| Synthesizability LLM | The core model that predicts whether a given 3D crystal structure can be synthesized, achieving 98.6% accuracy [2]. |

| Precursor LLM | Identifies suitable chemical precursors for solid-state synthesis of binary and ternary compounds with an 80.2% success rate [2]. |

| Material String | A specialized text representation that encodes space group, lattice parameters, atomic species, and Wyckoff positions, enabling efficient LLM processing [2]. |

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) | The source of experimentally verified, synthesizable crystal structures used as positive samples for training the models [2]. |

| Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning Model | A machine learning model used to screen theoretical databases and identify high-confidence non-synthesizable structures for the negative dataset [2]. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Used in conjunction with CSLLM to rapidly predict 23 key properties for the thousands of synthesizable structures identified by the framework [2]. |

| Gynosaponin I | Gynosaponin I, MF:C42H72O12, MW:769.0 g/mol |

| Chlorantine yellow | Chlorantine yellow, MF:C28H16N4Na4O16S4, MW:884.7 g/mol |

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What are the main types of text descriptors I can use for crystal structures? Different text descriptions are suited for various tasks, from basic retrieval to conditional generative AI. The choice depends on your goal, such as database search, similarity analysis, or guiding a generative model.

Table: Common Types of Text Descriptors for Crystal Structures

| Descriptor Type | Description | Best Use Cases | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Publication Text | Uses titles, abstracts, or keywords from scientific papers linked to a crystal structure [17]. | Training models to capture high-level material properties and functionalities for intuitive, human-language-based retrieval. | "narrow-bandgap material," "visible light photocatalysis" [17] |

| Reduced Composition | The chemical formula of the material, often presented in a standardized order [18]. | A simple, fundamental descriptor for basic categorization and composition-focused models. | "TiO2", "NaCl" |

| Formatted Text | A structured combination of key properties, such as composition and crystal system [18]. | Providing clear, multi-property conditioning for generative AI models. | "TiO2, tetragonal" [18] |

| General Text | Diverse, rich descriptions of a material's properties and functions, often generated by Large Language Models (LLMs) [18]. | Enabling flexible, context-aware generation and retrieval based on complex, natural language prompts. | A description of a material's application in batteries |

| Material String | A specialized, condensed text format designed to include essential crystal information (lattice, coordinates, symmetry) efficiently for LLMs [19]. | Fine-tuning LLMs for high-accuracy predictive tasks like synthesizability assessment. | A string encoding space group, Wyckoff positions, etc. [19] |

FAQ 2: How can I generate meaningful text descriptors when I have a large dataset and limited annotations? For large-scale projects, you can leverage literature-derived data and contrastive learning.

- Method: Use a dataset of crystal structures paired with their corresponding publication titles and abstracts [17].

- Process: Train a model using a contrastive learning framework, such as CLaSP (Contrastive Language-Structure Pre-training) [17]. This method uses a crystal structure encoder and a text encoder. The model is trained to minimize a contrastive loss function that pulls the embeddings of a crystal structure and its correct text description closer together in a shared space, while pushing it away from other unrelated descriptions [17].

- Protocol:

- Data Collection: Obtain a large dataset (e.g., over 400,000 entries from the Crystallography Open Database) that links crystal structures with paper titles and/or abstracts [17].

- Keyword Generation: Use a Large Language Model (LLM) to generate concise keywords (e.g., up to 10 per structure) from the title-abstract pairs [17].

- Model Training: Jointly train a crystal encoder (e.g., a graph neural network) and a text encoder (e.g., a pre-trained SciBERT model) using the contrastive loss. This teaches the model the semantic relationship between a structure and its textual description without needing explicit property labels [17].

FAQ 3: My goal is to predict the synthesizability of a metastable material. What is the most accurate method? Recent advances show that models fine-tuned on comprehensive datasets significantly outperform traditional methods. The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Model (CSLLM) framework is a state-of-the-art approach [19].

- Experimental Protocol for CSLLM:

- Dataset Curation:

- Positive Examples: Collect synthesizable crystal structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD). For example, 70,120 ordered structures with ≤40 atoms and ≤7 elements [19].

- Negative Examples: Generate non-synthesizable examples by screening theoretical databases (e.g., Materials Project) with a pre-trained Positive-Unlabeled (PU) learning model. Select structures with the lowest synthesis likelihood score (e.g., CLscore <0.1) [19].

- Text Representation: Convert crystal structures into a simplified "material string" text format that retains essential information on lattice, composition, atomic coordinates, and symmetry without redundancy [19].

- Model Fine-Tuning: Fine-tune a large language model (like LLaMA) on this balanced dataset of material strings labeled as synthesizable or non-synthesizable. This domain-specific tuning aligns the model's knowledge with crystallographic concepts [19].

- Dataset Curation:

Table: Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

| Method | Principle | Reported Accuracy | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSLLM Framework [19] | Fine-tuned LLM using "material string" representation. | 98.6% | Highest accuracy; also predicts synthesis methods and precursors. |

| Teacher-Student PU Learning [19] | Semi-supervised learning with positive and unlabeled data. | 92.9% | Effective when definitive negative examples are unavailable. |

| Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning [3] | Class-weighting of unlabeled examples based on synthesizability likelihood. | >87.9% for 3D crystals | Useful for leveraging large, unlabeled datasets. |

| Kinetic Stability (Phonons) | Assessing the presence of imaginary frequencies in the phonon spectrum. | 82.2% | Based on fundamental physical stability. |

| Thermodynamic Stability | Calculating energy above the convex hull via DFT. | 74.1% | Widely accessible and fast for screening. |

| Charge-Balancing | Checking if a composition has a net neutral ionic charge. | ~37% | Computationally inexpensive but often inaccurate. |

FAQ 4: How can I ensure my text-based model reliably understands complex crystal chemistry? Use a text encoder that has been specifically aligned with crystal structure data through contrastive learning.

- Protocol: Crystal CLIP Training [18]:

- Model Setup: Use a transformer-based text encoder (e.g., a MatTPUSciBERT model) and a crystal structure encoder (e.g., an Equivariant Graph Neural Network) [18].

- Training: The model is trained on positive pairs, which are crystal structures and their corresponding textual descriptions.

- Objective: Maximize the cosine similarity between the embedding of a crystal structure and the embedding of its correct text description. Simultaneously, minimize the similarity with embeddings from incorrect, negative pairs [18].

- Outcome: This process creates a shared embedding space where, for instance, the text "perovskite" is located near the crystal structures of actual perovskites, and elements are clustered meaningfully (e.g., halogens, transition metals) based on their chemical properties [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Software | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Crystallography Open Database (COD) [17] | Provides a large source of crystal structures paired with publication data for training text-structure models. |

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [19] | A key resource for obtaining confirmed, synthesizable crystal structures to use as positive examples in model training. |

| SciBERT / MatTPUSciBERT [17] [18] | Pre-trained language models on scientific text, serving as an excellent starting point for a text encoder in materials science. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | A core architecture for encoding crystal structures into numerical representations (embeddings) that capture atomic interactions and geometry [17] [18]. |

| Large Language Model (e.g., LLaMA) [19] | The base model to be fine-tuned for high-level tasks like synthesizability prediction and precursor recommendation. |

| Contrastive Learning Framework (e.g., CLaSP, Crystal CLIP) [17] [18] | The training paradigm used to align the semantic spaces of crystal structures and text descriptions without manual annotation. |

| Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning [3] [19] | A semi-supervised machine learning technique critical for handling the lack of confirmed negative (non-synthesizable) examples in materials data. |

| Material String [19] | A specialized text representation for crystal structures that enables efficient processing by Large Language Models. |

| AF488 Dbco | AF488 Dbco, MF:C48H49N5O11S2, MW:936.1 g/mol |

| Aglain C | Aglain C, MF:C36H42N2O8, MW:630.7 g/mol |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low accuracy in text-based retrieval of crystal structures.

- Potential Cause 1: The text descriptors are too vague or only describe structural features without mentioning properties or functions.

- Solution: Use or generate text that includes high-level functional information. Leverage publication abstracts and LLM-generated keywords like "superconductor" or "metal-organic framework" instead of just "cubic crystal" [17].

- Potential Cause 2: The model has not been properly aligned to understand the relationship between text and crystal structures.

- Solution: Fine-tune your text encoder using a contrastive learning framework like Crystal CLIP. This explicitly teaches the model which texts and structures correspond to each other [18].

Problem: Poor generalizability of synthesizability predictions to new, complex materials.

- Potential Cause: The model was trained on a dataset that is not balanced or comprehensive enough, or it over-relies on simplistic proxies like charge-balancing.

- Solution:

- Curate a Balanced Dataset: Follow the protocol in FAQ 3. Use a PU learning model to rigorously select high-confidence negative examples, ensuring your dataset covers diverse crystal systems and compositions [19].

- Use a Advanced Model Architecture: Move beyond traditional machine learning. Fine-tune a Large Language Model (LLM) using the "material string" representation, as done in the CSLLM framework, which learns complex chemical principles directly from data [19].

Experimental Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for developing text descriptors and applying them to predict material synthesizability, particularly for metastable materials.

In materials science, a significant challenge lies in accurately predicting whether a hypothetical material is synthesizable. This is particularly crucial for metastable materials, which are not in their thermodynamic ground state but can be synthesized through kinetically controlled pathways. Traditional proxies for synthesizability, such as formation energy or distance from the convex hull, often fail as they do not fully account for kinetic factors and technological constraints inherent in synthesis experiments [5] [10].

A major bottleneck for machine-learning approaches is the scarcity of reliable negative data. Failed synthesis attempts are rarely published, and an unsynthesized material in one context might be synthesizable in another [5] [20]. The Positive and Unlabeled (PU) learning framework directly addresses this by training a model using only a set of known positive examples (synthesized materials) and a set of unlabeled data (which contains both synthesizable and unsynthesizable materials) [5] [20].

This technical support guide focuses on the SynCoTrain model, a dual-classifier, semi-supervised approach designed to improve the accuracy of synthesizability predictions for metastable materials research [5] [21].

Detailed Methodology: Implementing the SynCoTrain Framework

Experimental Protocol for Synthesizability Prediction

The following protocol outlines the key steps for implementing a SynCoTrain-style model, using oxide crystals as a target material family [5] [20].

1. Data Curation and Pre-processing

- Data Source: Access crystal structure data from the Materials Project database via its API [20].

- Positive Label Identification: Identify synthesizable (positive) materials from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) subset, flagged as "experimental" within the Materials Project [20].

- Unlabeled Set Creation: The "theoretical" materials from the Materials Project serve as the unlabeled set. This set contains both potentially synthesizable and unsynthesizable materials [20].

- Data Filtering:

2. Feature Encoding with Graph Neural Networks SynCoTrain employs two complementary Graph Convolutional Neural Networks (GCNNs) to encode crystal structures, leveraging their ability to directly learn from atomic structure information [5] [20].

- ALIGNN (Atomistic Line Graph Neural Network): Encodes both atomic bonds and bond angles into its architecture, providing a perspective that aligns with a chemist's view of the data [5] [20].

- SchNet: Uses continuous-filter convolutional layers that are well-suited for modeling quantum interactions in atomic systems, offering a physicist's perspective on the data [5] [20].

3. The Co-Training and PU Learning Workflow The core of SynCoTrain involves iterative co-training of two separate PU learners, each based on a different GCNN [5] [20].

- Base PU Learning: The method by Mordelet and Vert is used as a building block. A classifier is trained to distinguish the known positive examples from the unlabeled set. This classifier is then applied to the unlabeled data, and the items it classifies with the highest confidence are iteratively used to refine the model [5] [20].

- Dual-Classifier Co-Training:

- Train an initial PU learner using the ALIGNN classifier (Iteration 0).

- Train an initial PU learner using the SchNet classifier (Iteration 0).

- The two classifiers then iteratively "co-train" each other. Each classifier's high-confidence predictions on the unlabeled data are used to update the other classifier's training pool [20] [22].

- This process repeats for several iterations, with the two classifiers exchanging knowledge to reduce individual model bias and improve generalizability [5].

- Prediction: The final labels for the unlabeled data are determined by averaging the predictions from the two refined classifiers [5].

The workflow for this methodology is outlined in the diagram below.

SynCoTrain Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Components for a SynCoTrain Framework Implementation

| Item | Function/Description | Application in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| ALIGNN Model | A graph neural network that encodes atomic bonds and bond angles. | Provides one of the two complementary "views" of the crystal structure data during co-training [5] [20]. |

| SchNet Model | A graph neural network that uses continuous-filter convolutions to model quantum interactions. | Provides the second, distinct "view" of the crystal structure data for co-training [5] [20]. |

| Materials Project API | A programmatic interface to access the Materials Project database. | The primary source for crystal structure data, including both experimental (positive) and theoretical (unlabeled) entries [20]. |

| Pymatgen Library | A robust Python library for materials analysis. | Used for processing crystal structures, determining oxidation states, and filtering data for specific material families (e.g., oxides) [20]. |

| Positive & Unlabeled (PU) Learning Algorithm | The base semi-supervised learning method that learns from known positives and an unlabeled set. | The core learning mechanism embedded within each of the two classifiers in the co-training framework [5] [20]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q1: My model achieves high performance on the test set but fails to generalize on new, out-of-distribution material families. How can I improve its robustness?

A: This is a classic sign of model bias and overfitting. SynCoTrain was specifically designed to mitigate this issue.

- Solution: Implement a dual-classifier co-training framework similar to SynCoTrain. Using two models with different architectural biases (like ALIGNN and SchNet) forces the system to learn more robust features. The iterative exchange of predictions helps prevent either model from overfitting to spurious patterns in the training data [5].

- Preventive Measure: Start your research by focusing on a single, well-characterized material family (e.g., oxides) with extensive experimental data. This reduces initial dataset variability and provides a more reliable baseline. The model can later be extended to other families [5].

Q2: The unlabeled data in my project is noisy and may not be representative of the true distribution. How does this affect the model, and what can I do?

A: The quality of unlabeled data is critical for semi-supervised learning. Noisy or non-representative data can degrade performance and lead to incorrect conclusions [22].

- Solution:

- Rigorous Pre-processing: Apply strict filters to your unlabeled data. For synthesizability prediction, this includes using DFT-optimized structures from a single source (like the Materials Project) to ensure consistent data quality and removing entries with implausibly high formation energies [5] [20].

- Investigate Data Drift: Continuously monitor the distribution of incoming data compared to your training data. Techniques like the Population Stability Index (PSI) or Kolmogorov-Smirnov test can help detect significant distribution shifts [23].

Q3: I am dealing with a severe class imbalance where the positive examples are a tiny fraction of the unlabeled data. How can I prevent my model from being biased toward the negative class?

A: This is a fundamental characteristic of the synthesizability prediction problem, and PU learning is the strategic response.

- Solution: Do not discard the unlabeled data. Instead, use a PU learning strategy that treats the unlabeled set as a mixture of positives and negatives. The base PU learner in SynCoTrain is designed to iteratively extract likely negative examples from the unlabeled set, effectively addressing the imbalance by refining the decision boundary [5] [24]. Avoid simply treating all unlabeled data as negative, as this introduces massive label noise and will cripple model accuracy [24].

Q4: During co-training, the performance of my two classifiers starts to diverge significantly. What could be the cause?

A: Divergence often indicates that one model is learning faster or is more susceptible to noise in the pseudo-labels.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Review Confidence Thresholds: Ensure you are only exchanging high-confidence predictions between the classifiers. If the threshold is too low, one model can pollute the other's training set with erroneous labels [22].

- Cross-Validate Independently: Regularly evaluate each classifier on a held-out validation set separately. This will help you identify if one model is fundamentally underperforming or overfitting [23].

- Check Feature Consistency: Verify that the two "views" of your data (from ALIGNN and SchNet) are indeed independent and sufficient for classification. If one view is inherently noisier or less informative, it will hinder the co-training process [22].

The logical relationship of these troubleshooting steps is summarized in the following flowchart.

Quantitative Performance of the SynCoTrain Model

The SynCoTrain model has demonstrated robust performance in predicting synthesizability. The table below summarizes key quantitative results as reported in the research.

Table: Reported Performance Metrics for SynCoTrain on Oxide Crystals [5] [20] [25]

| Metric | Reported Outcome | Evaluation Context |

|---|---|---|

| Recall | Achieved high recall | Performance on internal and leave-out test sets. This indicates the model successfully identifies most of the truly synthesizable materials [5] [20]. |

| Generalizability | Mitigated model bias and enhanced generalizability | Demonstrated through the co-training framework leveraging two complementary GCNN classifiers (ALIGNN and SchNet) [5] [20]. |

| Data Efficiency | Effective use of 10,206 positive and 31,245 unlabeled data points after filtering | Initial dataset for oxide crystals, showing the framework's ability to learn from a limited set of positives and a large unlabeled pool [20]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

1. My ALIGNN model is running out of memory during training. What are my options? Memory issues commonly occur when processing large crystal structures or using big batch sizes. Several solutions can help:

- Reduce Batch Size: Start by decreasing your training batch size. This is the most straightforward way to lower memory consumption.

- Simplify the Graph: Use a smaller atomistic graph cutoff radius to reduce the number of edges. The ALIGNN-d model provides a memory-efficient alternative to maximally connected graphs while maintaining accuracy [26].

- Optimize Data Loading: Use a

DataLoaderwithpin_memory=Falseif you are not using a GPU, or monitor CPU-GPU transfer.

2. What is the fundamental difference between ALIGNN and a standard CGCNN? The key difference lies in the explicit inclusion of angular information. Standard Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Networks (CGCNNs) primarily model atoms (nodes) and bonds (edges). ALIGNN enhances this by also constructing a line graph where nodes represent bonds from the original graph, and edges in this line graph represent bond angles. This allows the model to explicitly learn from both interatomic distances and bond angles during message passing [27].

3. When should I use ALIGNN-d over the standard ALIGNN model? You should consider ALIGNN-d when predicting properties that are highly sensitive to dihedral angles or complex molecular geometries. ALIGNN-d extends the ALIGNN approach by incorporating dihedral angles, providing a more complete geometric description. This is critical for accurately modeling the optical response of dynamically disordered complexes and other systems where four-body interactions are significant [26].

4. How do I prepare my data to train a custom property prediction model with ALIGNN? Data preparation requires two main components [28]:

- Structure Files: Save your atomic structures in a supported format (e.g.,

POSCAR,.cif,.xyz) in a single directory. - Target Properties File: Create a comma-separated values (CSV) file named

id_prop.csv. Each line should contain a structure filename and its corresponding target value (e.g.,POSCAR_1, 1.25). For multi-output tasks, the target values can be space-separated on a single line.