Atom2Vec for Synthesizability Prediction: A Deep Learning Framework Accelerating Materials and Drug Discovery

This article explores the transformative role of Atom2Vec and related deep learning representations in predicting the synthesizability of chemical compounds and materials.

Atom2Vec for Synthesizability Prediction: A Deep Learning Framework Accelerating Materials and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of Atom2Vec and related deep learning representations in predicting the synthesizability of chemical compounds and materials. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we cover the foundational principles of converting chemical formulas into machine-readable vectors, detail the methodology behind models like SynthNN and DeepSA, and address key challenges such as data scarcity and model interpretability. The content provides a comparative analysis against traditional methods, highlighting significant performance gains and real-world validation. This guide serves as a comprehensive resource for integrating these AI-driven tools into computational screening workflows to enhance the efficiency and success rate of discovering synthesizable candidates.

From Atoms to Algorithms: Demystifying Atom2Vec and the Synthesizability Challenge

The discovery of new materials and drug candidates is fundamentally limited by a critical challenge: the synthesizability problem. This refers to the significant gap between computationally designed compounds and their actual synthetic accessibility in a laboratory. In materials science and drug discovery, high-throughput computational methods can generate billions of candidate structures with desirable properties, but the vast majority are either impossible to synthesize with current methodologies or would require prohibitively complex synthesis pathways. The core issue stems from the fact that while computational models excel at predicting desirable properties from structure, they often lack the chemical intelligence to assess whether a proposed structure can be realistically constructed from available precursors and synthetic protocols.

Traditionally, assessing synthesizability has relied on expert knowledge and heuristic rules such as charge-balancing for inorganic materials. However, these approaches show limited accuracy; for instance, charge-balancing correctly identifies only 37% of known synthesized inorganic materials, and even among typically ionic binary cesium compounds, only 23% are charge-balanced [1]. Similarly, in drug discovery, conventional synthesizability scores often assume near-infinite building block availability, which does not reflect the resource-constrained environment of actual research laboratories [2]. The synthesizability problem therefore represents a major bottleneck in accelerating the discovery and development of new materials and therapeutics, necessitating advanced computational approaches that can integrate synthetic feasibility directly into the design process.

atom2vec Representation for Chemical Formulas

The atom2vec representation framework provides a powerful approach for encoding chemical information directly from material compositions without requiring prior structural knowledge. This method treats chemical formulas as foundational elements for a machine learning model, leveraging the entire space of synthesized inorganic chemical compositions to learn an optimal representation [1] [3]. Unlike traditional featurization methods that rely on pre-defined elemental descriptors, atom2vec learns embedding vectors for each atom type directly from the distribution of previously synthesized materials present in large databases.

In this approach, each chemical formula is represented by a learned atom embedding matrix that is optimized alongside all other parameters of a neural network [1]. The dimensionality of this representation is treated as a hyperparameter determined prior to model training. The key advantage of this method is that it requires no assumptions about which factors influence synthesizability or what metrics might serve as proxies for synthesizability, such as charge balancing or thermodynamic stability [1]. Instead, the chemical principles of synthesizability—including charge-balancing, chemical family relationships, and ionicity—are learned directly from the data of experimentally realized materials [1].

This data-driven representation is particularly valuable for predicting the synthesizability of novel compositions because it can capture complex patterns and relationships that may not be evident through traditional chemical intuition or rule-based approaches. The atom2vec model has demonstrated an ability to identify synthesizable materials with 7× higher precision than density-functional theory (DFT)-calculated formation energies, which are commonly used as a stability proxy [1].

Case Study: SynthNN - A Deep Learning Synthesizability Model

Model Architecture and Training Approach

SynthNN (Synthesizability Neural Network) exemplifies the application of atom2vec representation to predict the synthesizability of crystalline inorganic materials. This deep learning classification model is trained on a comprehensive dataset of chemical formulas derived from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), which contains a nearly complete history of all crystalline inorganic materials reported in scientific literature [1]. To address the challenge that unsuccessful syntheses are rarely reported, the training dataset is augmented with artificially generated unsynthesized materials.

The model employs a semi-supervised learning approach that treats unsynthesized materials as unlabeled data and probabilistically reweights them according to their likelihood of being synthesizable [1]. This places SynthNN within the category of Positive-Unlabeled (PU) learning algorithms, which are particularly suited to materials science applications where negative examples (definitively unsynthesizable materials) are not available. The ratio of artificially generated formulas to synthesized formulas used in training is a key model hyperparameter (N_synth) that requires careful optimization [1].

Performance Benchmarking

SynthNN's performance has been rigorously evaluated against both computational methods and human experts:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

| Method | Precision | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| SynthNN | 7× higher than DFT-based formation energy | Requires training data |

| Charge-Balancing | 37% of known synthesized materials | Inflexible constraint |

| DFT Formation Energy | Captures only 50% of synthesized materials | Fails to account for kinetic stabilization |

| Human Experts | 1.5× lower precision than SynthNN | Specialized domains, time-intensive |

In a head-to-head material discovery comparison against 20 expert materials scientists, SynthNN outperformed all experts, achieving 1.5× higher precision and completing the task five orders of magnitude faster than the best human expert [1]. This demonstrates not only the accuracy but also the remarkable efficiency of the approach for high-throughput materials discovery.

Application Notes & Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing SynthNN for Crystalline Materials

Purpose: To predict the synthesizability of novel inorganic crystalline compositions using the SynthNN framework.

Materials and Data Requirements:

- Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD): Primary source of synthesized material compositions for training [1]

- Artificially generated compositions: Created through combinatorial methods or negative sampling

- Computational resources: GPU-accelerated deep learning environment

- Software dependencies: Python with deep learning frameworks (PyTorch/TensorFlow)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Data Preparation:

- Extract known synthesized compositions from ICSD

- Generate artificial negative examples using combinatorial approaches

- Split data into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets

Model Configuration:

- Implement atom2vec embedding layer with dimensionality 64-256

- Design neural network architecture with fully connected layers

- Set hyperparameters (learning rate, batch size, N_synth ratio)

Training Procedure:

- Initialize model with random weights

- Optimize using Adam optimizer with binary cross-entropy loss

- Apply Positive-Unlabeled learning weighting for unlabeled examples

- Validate model performance after each epoch

Evaluation:

- Calculate precision, recall, and F1-score on test set

- Compare against charge-balancing and DFT formation energy baselines

- Assess model calibration and confidence estimates

Troubleshooting:

- Poor performance may indicate inadequate representation of certain chemical spaces in training data

- Overfitting can be addressed through regularization techniques or data augmentation

- Embedding dimensionality can be optimized through hyperparameter tuning

Protocol 2: In-House Synthesizability Scoring for Drug Discovery

Purpose: To develop a synthesizability score tailored to specific available building blocks in drug discovery research.

Materials and Data Requirements:

- In-house building block inventory: Typically 5,000-10,000 available compounds [2]

- Computer-Aided Synthesis Planning (CASP) tool: e.g., AiZynthFinder [2]

- Target molecule set: For validation and training

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Synthesis Planning Setup:

- Configure CASP tool with in-house building block inventory

- Set appropriate reaction parameters and constraints

- Run synthesis planning on representative molecule set

Data Generation:

- Collect results of synthesis planning attempts

- Label molecules as synthesizable or non-synthesizable based on CASP outcomes

- Extract molecular features for training

Model Training:

- Implement machine learning classifier (random forest, neural network)

- Train on CASP-derived synthesizability labels

- Validate model predictions against held-out CASP results

Integration:

- Incorporate synthesizability score into de novo molecular design workflow

- Use as filter or multi-objective optimization parameter

Performance Expectations: When using only ~6,000 in-house building blocks versus 17.4 million commercial compounds, synthesis planning success rates decrease by only approximately 12%, though synthesis routes may be two steps longer on average [2]. This minimal performance reduction demonstrates the feasibility of resource-limited synthesizability prediction.

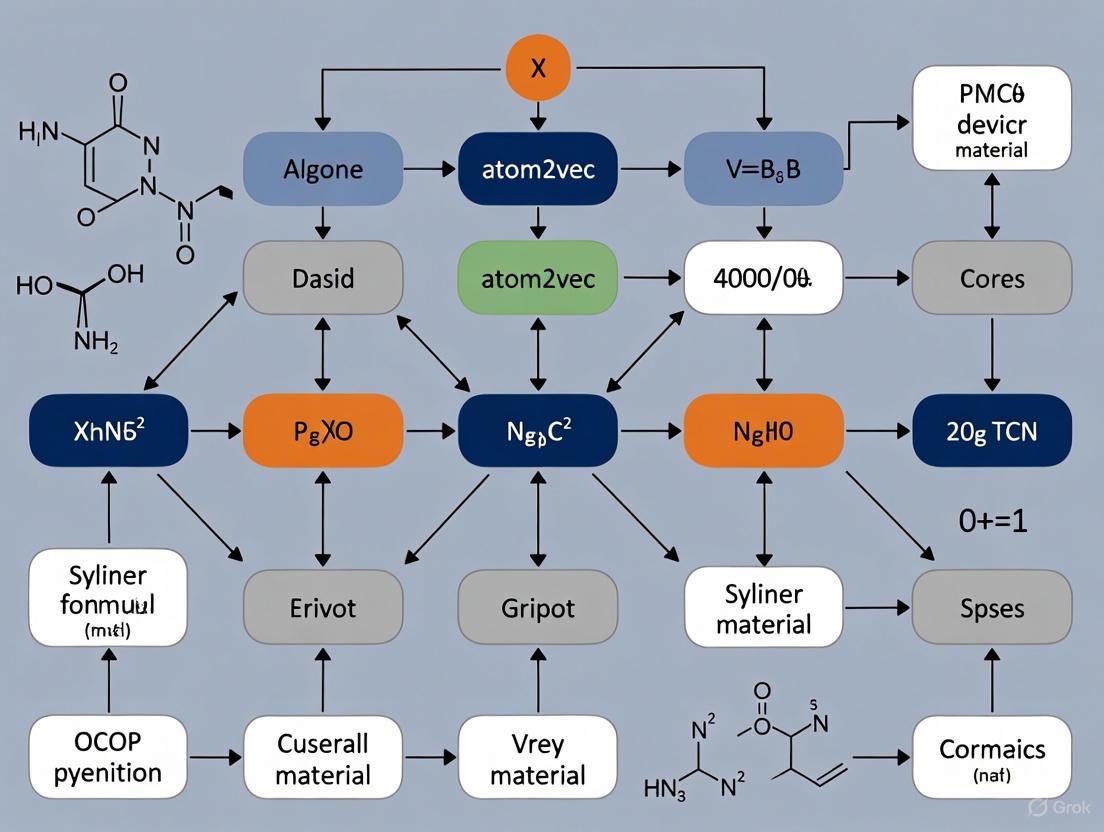

Visualization: Synthesizability Prediction Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for Synthesizability Research

| Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) | Provides known synthesized compositions for training | Crystalline inorganic materials [1] |

| AiZynthFinder | Computer-Aided Synthesis Planning tool | Drug discovery, organic molecules [2] |

| ZINC Database | Commercial building block repository | General synthesizability assessment [2] |

| Composition Analyzer Featurizer (CAF) | Generates numerical features from chemical formulas | Solid-state materials research [3] |

| Structure Analyzer Featurizer (SAF) | Extracts structural features from crystal structures | Structure-property mapping [3] |

| Matminer | Open-source toolkit for materials data featurization | High-throughput materials screening [3] |

Validation and Experimental Design

Positive-Unlabeled Learning Framework

A critical consideration in synthesizability prediction is the absence of definitive negative examples, as materials not yet synthesized may still be synthesizable with future methodologies. The Positive-Unlabeled (PU) learning framework addresses this challenge by treating unsynthesized materials as unlabeled rather than definitively negative [1]. In this approach:

- Positive examples are known synthesized materials from databases like ICSD

- Unlabeled examples are artificially generated compositions not present in databases

- The model learns to distinguish synthesizable patterns while accounting for potential false negatives in the unlabeled set

PU learning algorithms probabilistically reweight unlabeled examples according to their likelihood of being synthesizable, improving model robustness against incomplete labeling [1]. Performance evaluation in this framework typically emphasizes F1-score rather than traditional accuracy metrics, as the true negative rate cannot be definitively established [1].

Experimental Validation Protocols

Experimental validation is essential to confirm computational synthesizability predictions. The following protocol outlines a systematic approach:

Purpose: To experimentally verify the synthesizability of computationally predicted materials or molecules.

Materials:

- Predicted synthesizable compositions/molecules

- Required precursors and building blocks

- Standard laboratory equipment for synthesis (e.g., solvothermal reactors, Schlenk lines)

- Characterization equipment (XRD, NMR, LC-MS)

Procedure:

- Synthesis Planning: Use CASP tools to identify specific synthesis routes

- Precursor Preparation: Acquire or synthesize required starting materials

- Synthesis Attempt: Execute proposed synthesis under varied conditions

- Characterization: Analyze products to confirm identity and purity

- Iterative Optimization: Modify conditions based on initial results

Case Study Example: In a recent study of monoglyceride lipase (MGLL) inhibitors, researchers experimentally evaluated three de novo candidates using AI-suggested synthesis routes employing only in-house building blocks [2]. They found one candidate with evident activity, demonstrating the practical utility of synthesizability-informed molecular design.

Computational Tools and Implementation

Available Featurization Tools

Multiple featurization tools are available for generating numerical representations from chemical compositions and structures:

Table 3: Comparison of Featurization Tools for Materials Research

| Tool | Feature Type | Number of Features | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| MAGPIE | Compositional | 115-145 | Perovskite discovery, superconducting critical temperature [3] |

| JARVIS | Compositional/Structural | 438 | 2D materials identification, thermodynamic properties [3] |

| atom2vec | Compositional | N/A | Synthesizability prediction, crystal system classification [1] [3] |

| mat2vec | Compositional | 200 | Property prediction, materials natural language processing [3] |

| CAF+SAF | Compositional/Structural | 227 total | Explainable ML for solid-state structures [3] |

| CGCNN | Structural | N/A | Crystal graph convolutional networks [3] |

Visualization: Positive-Unlabeled Learning Approach

The integration of atom2vec representations with synthesizability classification models like SynthNN represents a significant advancement in addressing the synthesizability problem. These approaches leverage the complete landscape of known synthesized materials to learn the complex chemical principles governing synthetic accessibility, outperforming both traditional computational methods and human experts in prediction precision.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on several key areas:

- Multi-modal learning that integrates compositional, structural, and synthetic procedure data

- Transfer learning approaches to adapt synthesizability predictions to specific laboratory constraints

- Active learning frameworks that iteratively improve models based on experimental feedback

- Explainable AI techniques to elucidate the chemical rationale behind synthesizability predictions

As these methodologies mature, they will increasingly bridge the gap between computational design and experimental realization, accelerating the discovery of novel materials and therapeutic compounds with optimized properties and guaranteed synthetic feasibility.

The quest for effective machine representations of atoms constitutes a foundational challenge in computational materials science. Distributed representations characterize an object by embedding it in a continuous vector space, positioning semantically similar objects in close proximity [4]. For atoms, this means that elements sharing chemical similarities will reside near one another in this learned vector space. The Atom2Vec algorithm, introduced by Zhou et al., represents a groundbreaking approach to deriving these representations through unsupervised learning from extensive databases of known compounds and materials [5]. The core hypothesis is analogous to the natural language processing domain: just as words can be understood by the company they keep in textual corpora, atoms can be characterized by their common chemical environments in crystalline structures [4]. By leveraging the growing repositories of materials data, Atom2Vec learns the fundamental properties of atoms autonomously, without human supervision or pre-defined feature sets, generating high-dimensional vector representations that encapsulate complex chemical relationships and periodic trends.

Quantitative Performance Analysis

Performance of Atom2Vec and Related Models

Table 1: Comparative performance of different atom representation methods on materials property prediction tasks.

| Model | Input Data | Representation Dimensionality | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atom2Vec [5] [4] | Crystal structure databases | Varies (hyperparameter) | Discovers chemical similarities without prior knowledge | Limited to elements in training data |

| SkipAtom [4] | Crystal structure graphs using Voronoi decomposition | Not specified | Reflects chemo-structural environments; effective for compound representation | Requires structural data for training |

| Mat2Vec [4] | Scientific abstracts from materials literature | Not specified | Captures research context and trends | May reflect scientific interest rather than inherent chemistry |

| Element2Vec [6] | Wikipedia text using LLMs | Global and local embeddings | Incorporates rich textual knowledge; interpretable attributes | Limited by quality and coverage of source text |

| Random Vectors [4] | Random sampling from standard normal distribution | Arbitrary | Simple to generate | No semantic relationships |

| One-Hot Vectors [4] | Unique binary vectors per element | Number of element categories | Simple interpretation | No similarity information; high dimensionality |

Synthesizability Prediction Performance

Table 2: Performance comparison of synthesizability prediction methods on inorganic crystalline materials.

| Method | Basis of Prediction | Precision | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SynthNN (with Atom2Vec) | Deep learning on known compositions | 7× higher than formation energy | Outperformed all 20 human experts; 1.5× higher precision than best expert | [1] |

| Charge-Balancing | Net neutral ionic charge using common oxidation states | Low (23-37% of known compounds) | Inflexible; cannot account for different bonding environments | [1] |

| DFT Formation Energy | Thermodynamic stability relative to decomposition products | Captures only 50% of synthesized materials | Fails to account for kinetic stabilization | [1] |

| BLMM Crystal Transformer | Blank-filling language model | 89.7% charge neutrality, 84.8% balanced electronegativity | 4-8× higher than pseudo-random sampling | [7] |

Fundamental Atom2Vec Methodology

Core Algorithm and Workflow

The Atom2Vec algorithm employs an unsupervised learning framework inspired by natural language processing techniques. The fundamental analogy translates words in sentences to atoms in crystal structures [4]. The methodology involves these key steps:

Data Extraction: Gather crystal structures from comprehensive materials databases such as the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [1].

Environment Identification: For each atom in every crystal structure, identify its local chemical environment, typically defined by its nearest neighbors or coordination sphere.

Co-occurrence Matrix Generation: Construct a matrix documenting how frequently atoms co-occur in similar chemical environments across all structures in the database [4].

Dimensionality Reduction: Apply singular value decomposition (SVD) or neural network-based embedding techniques to the co-occurrence matrix to obtain lower-dimensional vector representations for each atom [4].

The resulting atom vectors capture complex chemical relationships, with atoms sharing similar properties or positions in the periodic table naturally clustering together in the vector space [5].

Implementation for Synthesizability Prediction

The application of Atom2Vec to synthesizability prediction involves specific adaptations and training strategies, as exemplified by the SynthNN model [1]:

Positive-Unlabeled Learning: The model is trained on a dataset consisting of:

Representation Learning: Chemical formulas are represented using the learned atom embedding matrix, which is optimized alongside all other parameters of the neural network [1].

Model Architecture: A deep neural network (SynthNN) is trained to classify materials as synthesizable or not based on their compositional representations, without requiring structural information [1].

This approach allows the model to learn the implicit "chemistry of synthesizability" directly from the distribution of experimentally realized materials, capturing complex factors beyond simple charge-balancing or thermodynamic stability [1].

Advanced Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Atom2Vec Model Training

Objective: Train Atom2Vec embeddings from a crystalline materials database.

Materials and Input Data:

- Crystal Structure Database: Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) or Materials Project database [1].

- Computing Environment: Standard deep learning framework (e.g., TensorFlow, PyTorch).

- Preprocessing Tools: Voronoi decomposition algorithms for identifying atomic neighbors in crystal structures [4].

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Extract crystal structures from the chosen database.

- For each structure, identify all atomic pairs within a specified cutoff distance or using Voronoi tessellation to determine nearest neighbors [4].

Training Set Generation:

- Create training pairs consisting of (target atom, context atom) for each atomic environment.

- For each atom in every crystal structure, pair it with all its neighboring atoms identified in step 1.

Model Configuration:

- Set embedding dimension as a hyperparameter (typically 50-200 dimensions).

- Initialize atom vectors randomly or using pre-trained values if available.

Model Training:

- Use Maximum Likelihood Estimation to maximize the average log probability:

(1/|M|) Σ_{m∈M} Σ_{a∈A_m} Σ_{n∈N(a)} log p(n|a)where M is the set of materials, A_m is the set of atoms in material m, and N(a) are the neighbors of atom a [4]. - Minimize cross-entropy loss between the one-hot vector representing the context atom and the normalized probabilities produced by the model.

- Use Maximum Likelihood Estimation to maximize the average log probability:

Validation:

- Evaluate learned embeddings by examining clustering of chemically similar elements.

- Test performance on downstream tasks such as formation energy prediction.

Protocol 2: Synthesizability Prediction with SynthNN

Objective: Predict synthesizability of inorganic chemical formulas using Atom2Vec representations.

Materials and Input Data:

- Positive Examples: 180,000+ synthesized inorganic crystalline materials from ICSD [1].

- Negative Examples: Artificially generated unsynthesized materials (treated as unlabeled data in PU learning framework).

- Atom2Vec Embeddings: Pre-trained atom vectors.

Procedure:

- Dataset Construction:

- Compile chemical formulas of known synthesized materials from ICSD as positive examples.

- Generate artificial negative examples through combinatorial composition generation or random sampling of chemical formulas not present in ICSD.

- Apply positive-unlabeled learning techniques to account for potentially synthesizable materials among the unlabeled examples [1].

Feature Representation:

- Represent each chemical formula using Atom2Vec embeddings of constituent atoms.

- Use pooling operations (e.g., sum, average, weighted average) to combine atomic vectors into fixed-dimensional compound representations [4].

Model Architecture:

- Implement a deep neural network classifier (SynthNN) with multiple fully connected layers.

- Use ReLU or similar activation functions between layers.

- Apply appropriate regularization techniques (dropout, L2 regularization) to prevent overfitting.

Training Procedure:

- Train the model to distinguish between synthesized and artificially generated materials.

- Use class weighting or sampling techniques to handle dataset imbalance.

- Employ early stopping based on validation performance.

Model Evaluation:

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Key resources for implementing Atom2Vec and synthesizability prediction models.

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Materials Databases | Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), Materials Project, OQMD | Source of crystal structures for training Atom2Vec models [1] [7] |

| Representation Models | Atom2Vec, SkipAtom, Mat2Vec, Element2Vec | Provide atomic embeddings for materials informatics tasks [5] [4] [6] |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch, JAX | Implementation of neural networks for SynthNN and related models |

| Language Models | BLMM Crystal Transformer, MatSciBERT | Alternative approaches for materials representation and generation [7] |

| Property Prediction Models | CGCNN, MEGNet, ALIGNN, PotNet | Benchmark models for evaluating quality of learned representations [8] |

| Generative Models | CDVAE, DiffCSP, GNoME | For inverse design of materials using learned representations [8] |

Future Directions and Advanced Applications

The integration of Atom2Vec with emerging deep learning architectures presents promising avenues for advancement. Transformer-based models like the Blank-filling Language Model for Materials (BLMM) have demonstrated exceptional capability in generating chemically valid compositions with high charge neutrality (89.7%) and balanced electronegativity (84.8%) [7]. These models effectively learn implicit "materials grammars" from composition data, enabling interpretable design and tinkering operations. For drug development professionals, these approaches facilitate rapid exploration of chemical space for novel inorganic compounds with potential pharmaceutical applications, such as contrast agents or diagnostic materials. The continuing development of inverse design pipelines using generative models trained on Atom2Vec representations will further accelerate the discovery of synthesizable materials with targeted properties [9]. As these models evolve, they increasingly capture complex chemical principles including charge-balancing, chemical family relationships, and ionicity, providing powerful tools for rational materials design across scientific disciplines [1].

Predicting whether a hypothetical chemical compound can be successfully synthesized remains a fundamental challenge in materials science and drug discovery. For decades, charge-balancing—ensuring a net neutral ionic charge based on elements' common oxidation states—has served as a primary heuristic for assessing synthesizability. However, evidence from large-scale materials databases reveals that this traditional metric fails to accurately predict synthetic accessibility. Analysis of the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) shows that only 37% of all known synthesized inorganic compounds are charge-balanced according to common oxidation states, with this figure dropping to a mere 23% for binary cesium compounds [1]. This discrepancy underscores a critical limitation: while chemically intuitive, charge-balancing operates as an excessively rigid filter that cannot account for the diverse bonding environments present in metallic alloys, covalent materials, or kinetically stabilized phases [1].

The development of atomistic representation learning methods, particularly atom2vec and its derivatives, has enabled more sophisticated, data-driven approaches to synthesizability prediction. These techniques learn distributed representations of atoms from existing materials databases, capturing complex chemical relationships that extend beyond simple charge-balancing considerations. By reformulating material discovery as a synthesizability classification task, models like SynthNN (Synthesizability Neural Network) demonstrate 7× higher precision than traditional formation energy calculations and outperform human experts by achieving 1.5× higher precision while completing screening tasks five orders of magnitude faster [1]. This Application Note examines the limitations of traditional synthesizability metrics and provides detailed protocols for implementing advanced machine learning approaches that leverage learned atomic representations.

Limitations of Traditional Synthesizability Metrics

Quantitative Comparison of Synthesizability Prediction Methods

Table 1: Performance comparison of synthesizability prediction approaches

| Method | Key Principle | Precision | Recall | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charge-Balancing | Net neutral ionic charge based on oxidation states | Low (exact values not reported) | N/A | Overly rigid; ignores diverse bonding environments; only 37% of known materials comply [1] |

| DFT Formation Energy | Thermodynamic stability relative to decomposition products | ~4× lower than SynthNN [1] | ~50% of synthesized materials [1] | Fails to account for kinetic stabilization; computationally intensive |

| SynthNN (atom2vec) | Data-driven classification from known materials | 7× higher than DFT [1] | High (outperforms human experts) [1] | Requires sufficient training data; model interpretability challenges |

| FTCP Representation | Crystal structure representation in real/reciprocal space | 82.6% [10] | 80.6% [10] | Requires structural information; less effective for composition-only screening |

| SC Model | Synthesizability score from structural fingerprints | 88.6% TPR for post-2019 materials [10] | 9.81% precision for post-2019 materials [10] | Performance varies across chemical spaces |

Why Charge-Balancing and Thermodynamic Metrics Fail

Traditional synthesizability assessment suffers from several fundamental limitations that machine learning approaches directly address:

Oversimplified Chemical Intuition: Charge-balancing applies a one-size-fits-all approach that fails to capture material-specific bonding characteristics. The metric performs particularly poorly for materials with metallic bonding, complex covalent networks, or those stabilized through kinetic rather than thermodynamic pathways [1].

Incomplete Stability Assessment: While DFT-calculated formation energy and energy above hull (Ehull) provide valuable thermodynamic insights, they fail to account for kinetic stabilization, synthetic pathway availability, and practical experimental constraints [10]. Studies indicate that formation energy calculations capture only approximately 50% of synthesized inorganic crystalline materials [1].

Exclusion of Practical Considerations: Traditional metrics ignore crucial experimental factors including precursor availability, equipment requirements, earth abundance of starting materials, toxicity considerations, and human-perceived importance of the target material—all factors that significantly influence synthetic decisions [1] [10].

Inability to Generalize: Rule-based approaches lack the flexibility to adapt to new chemical spaces or evolving synthetic methodologies, whereas data-driven models continuously improve as additional synthesized materials are reported [1].

Atomistic Representation Learning for Synthesizability

Foundational Concepts and Methodologies

Atomistic representation learning methods transform chemical elements into continuous vector embeddings that capture nuanced chemical relationships, mirroring successful natural language processing approaches where words with similar contexts have similar vector representations [4]. These learned representations form the foundation for modern synthesizability prediction models.

Table 2: Key atomic representation learning methods

| Method | Training Data | Representation Dimensionality | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atom2Vec | Co-occurrence matrix from materials database | Limited to number of atoms in matrix [4] | Captures elemental relationships from crystal structures |

| Mat2Vec | Scientific abstracts (text corpus) [4] | 200 dimensions [3] | Leverages rich contextual information from literature |

| SkipAtom | Crystal structures with atomic connectivity graphs [4] | Configurable (typically 50-200 dimensions) | Explicitly models local chemical environments; unsupervised |

| Element2Vec | Wikipedia text pages [11] | Global and local embeddings | Combines holistic and attribute-specific information |

The SynthNN Architecture and Workflow

The SynthNN model exemplifies the application of atomistic representations to synthesizability prediction. This deep learning framework leverages the entire space of synthesized inorganic chemical compositions through the following workflow:

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Computational Tools

Table 3: Key software and data resources for synthesizability prediction

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) | Structured database | Source of synthesized materials for training [1] [10] | Commercial |

| Materials Project API | Computational database | DFT-calculated properties; structural information [10] | Open |

| atom2vec | Algorithm | Unsupervised atomic representation learning [4] | Open |

| Matminer | Featurization toolkit | Compositional and structural descriptor generation [3] | Open |

| CAF/SAF | Feature generators | Composition Analyzer Featurizer (CAF) and Structure Analyzer Featurizer (SAF) for explainable ML [3] | Open |

| BLMM Crystal Transformer | Blank-filling language model | Generative design of inorganic materials [7] | Open |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing SynthNN for Synthesizability Classification

Purpose: To train a deep learning model for synthesizability prediction using atomistic representations and known materials data.

Materials and Data Sources:

- Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) for synthesized materials [1]

- Artificially generated unsynthesized compositions for negative examples [1]

- Python deep learning framework (PyTorch/TensorFlow)

- Atom2Vec or SkipAtom pretrained embeddings [4]

Procedure:

Data Preparation:

- Extract chemical formulas of known synthesized inorganic crystalline materials from ICSD (approximately 20,000-200,000 compositions) [1].

- Generate artificial negative examples through combinatorial composition generation or by sampling from hypothetical materials databases.

- Apply positive-unlabeled (PU) learning techniques to account for potentially synthesizable materials among the unlabeled examples [1].

Feature Generation:

- Implement atom2vec embedding lookup for each element in the chemical formula.

- Apply pooling operations (sum, average, or weighted pooling) to create fixed-length composition representations [4].

- For comparative analysis, generate alternative features including Magpie descriptors, one-hot encodings, or mat2vec representations [3].

Model Architecture:

- Construct a deep neural network with 3-5 hidden layers (512-1024 neurons per layer) with ReLU activation functions.

- Include dropout layers (rate=0.3-0.5) to prevent overfitting.

- Implement batch normalization between layers for training stability.

- Use sigmoid activation in the final layer for binary classification.

Model Training:

- Employ stratified k-fold cross-validation (k=5-10) to evaluate model performance.

- Utilize Adam optimizer with learning rate 0.001-0.0001 and binary cross-entropy loss.

- Implement early stopping with patience of 10-20 epochs based on validation loss.

- Balance training batches to address class imbalance.

Model Evaluation:

- Calculate precision, recall, F1-score, and AUC-ROC metrics.

- Compare performance against charge-balancing and DFT-based baselines.

- Perform ablation studies to assess contribution of different embedding strategies.

Troubleshooting:

- For poor convergence: Adjust learning rate, try different embedding dimensions, or increase model capacity.

- For overfitting: Increase dropout rate, implement L2 regularization, or augment training data.

- For embedding instability: Use pretrained embeddings or increase embedding training data.

Protocol 2: Composition-Based Synthesizability Screening

Purpose: To rapidly screen novel chemical compositions for synthesizability potential using only composition information.

Materials and Data Sources:

- Pretrained SynthNN model or alternative synthesizability classifier

- Candidate compositions for screening (e.g., from generative models or combinatorial enumeration)

- BLMM Crystal Transformer for composition generation and validation [7]

Procedure:

Composition Generation:

- Generate candidate compositions using generative models (GAN, VAE, or transformer-based).

- Apply charge-balancing as an initial filter (despite limitations) to reduce candidate space.

- Utilize BLMM for composition generation with built-in charge neutrality and electronegativity constraints [7].

Feature Extraction:

- Parse chemical formulas into constituent elements and stoichiometric coefficients.

- Convert elements to embeddings using pretrained atom2vec, SkipAtom, or similar.

- Apply stoichiometry-weighted pooling to create fixed-length vectors.

- Alternatively, use Magpie features or one-hot encodings for baseline comparisons.

Synthesizability Prediction:

- Apply trained classification model to generate synthesizability scores (0-1 scale).

- Rank candidates by synthesizability score for prioritization.

- Implement ensemble methods by combining predictions from multiple models.

Validation:

- Compare predictions with DFT-calculated formation energies where feasible.

- For top candidates, perform structural prediction and further stability analysis.

- Select highest-confidence candidates for experimental validation.

Troubleshooting:

- For chemically implausible high-scoring compositions: Incorporate additional constraints (electronegativity balance, radius ratio rules).

- For inconsistent predictions across similar compositions: Ensure embedding stability and consider ensemble methods.

- For memory limitations with large screening sets: Implement batch processing and efficient vector operations.

Protocol 3: Explainable Synthesizability Analysis

Purpose: To interpret synthesizability predictions and identify contributing chemical factors.

Materials and Data Sources:

- Trained synthesizability model

- Composition Analyzer Featurizer (CAF) and Structure Analyzer Featurizer (SAF) [3]

- Model interpretation libraries (SHAP, LIME)

Procedure:

Feature Importance Analysis:

- Apply SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) to quantify feature contributions.

- Identify which elements and stoichiometric ratios most influence predictions.

- Analyze whether model recovers known chemical principles (electronegativity, radius ratios, etc.).

Chemical Rule Extraction:

- Cluster materials in the embedding space and analyze synthesizability trends.

- Identify decision boundaries between synthesizable/unsynthesizable regions.

- Compare learned "chemical rules" with traditional heuristics.

Case Study Analysis:

- Select specific material families for detailed analysis (e.g., perovskites, Heuslers).

- Trace model predictions to specific training examples using attention mechanisms.

- Validate whether model captures domain-specific synthesizability factors.

Visualization:

- Create low-dimensional projections (t-SNE, UMAP) of material embeddings colored by synthesizability.

- Generate partial dependence plots for key elemental characteristics.

- Visualize attention weights in transformer-based models.

Applications and Validation

Performance Benchmarks and Experimental Validation

Machine learning approaches leveraging atomistic representations have demonstrated superior performance across multiple benchmarks:

Head-to-Head Expert Comparison: In a direct material discovery comparison, SynthNN outperformed all 20 expert materials scientists, achieving 1.5× higher precision while completing the task five orders of magnitude faster than the best human expert [1].

Temporal Validation: When trained on materials discovered before 2015 and tested on compounds added to databases after 2019, the synthesizability score (SC) model achieved 88.6% true positive rate accuracy, successfully identifying newly synthesizable materials [10].

Chemical Validity: The BLMM Crystal Transformer generates chemically valid compositions with 89.7% charge neutrality and 84.8% balanced electronegativity—more than four and eight times higher, respectively, compared to pseudo-random sampling [7].

Integration with Materials Discovery Workflows

Advanced synthesizability prediction integrates seamlessly into computational materials screening pipelines:

Generative Design: Use synthesizability predictions as constraints or objectives in generative models to ensure synthetic accessibility of proposed compositions [7].

High-Throughput Screening: Apply rapid synthesizability filters to computationally generated hypothetical materials before resource-intensive DFT calculations [10].

Experimental Prioritization: Rank candidate materials by synthesizability score to focus experimental efforts on the most promising candidates [1].

Tinkering Design: Utilize blank-filling language models to suggest chemically plausible element substitutions for known materials [7].

The limitations of traditional synthesizability metrics like charge-balancing and formation energy calculations necessitate more sophisticated, data-driven approaches. Atomistic representation learning methods, particularly those based on atom2vec and related techniques, provide a powerful framework for synthesizability prediction that captures complex chemical relationships beyond simple heuristics. The protocols outlined in this Application Note enable researchers to implement these advanced methods, significantly improving the efficiency and success rate of computational materials discovery. As these approaches continue to evolve, integrating synthesizability prediction directly into generative design workflows will further accelerate the identification of novel, synthetically accessible materials for technological applications.

The advent of machine learning (ML) in materials science has shifted the research paradigm from reliance solely on empirical rules and physical simulations to data-driven discovery. Central to this transformation are large-scale, curated databases that provide the foundational data for training and validating predictive models. Within the specific context of developing atomistic representations like atom2vec for predicting chemical synthesizability, three databases play particularly critical roles: the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), the Materials Project (MP), and PubChem. These databases collectively provide comprehensive coverage of known inorganic crystals, computationally characterized materials, and organic molecules, respectively. This application note details the quantitative contributions, experimental protocols, and integrative workflows for leveraging these databases to train and benchmark synthesizability models, providing a practical guide for researchers and scientists in drug development and materials informatics.

Database Profiles and Quantitative Comparison

The table below summarizes the core attributes and primary applications of the three key databases in the context of atom2vec and synthesizability research.

Table 1: Key Databases for Atomistic Model Training

| Database Name | Primary Content & Scope | Key Metrics and Volume | Role in atom2vec/Synthesizability Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [1] | Experimentally synthesized and structurally characterized inorganic crystalline materials. | A "nearly complete history" of reported inorganic crystals; used to train models on the entire space of synthesized compositions [1]. | Serves as the primary source of positive examples (synthesizable materials) for training supervised and positive-unlabeled (PU) learning models like SynthNN [1]. |

| Materials Project (MP) [12] [3] | A computational database of DFT-calculated material properties, including crystal structures, formation energies, and stability metrics for hundreds of thousands of materials. | Contains data on "hundreds of thousands" of materials; provides standardized formation energies and energies above the convex hull (Ehull) for stability assessment [12] [13]. | Provides stability descriptors (e.g., Ehull) used as features or validation metrics. Supplies hypothetical structures for discovery campaigns and seeds prototype-based structure generation [12] [13]. |

| PubChem [14] | An open archive of chemical substances, focusing on small molecules and their biological activities. | Contains over 46 million compound records (as of 2013). A 2015 analysis identified 28,462,319 unique atom environments within its datasets [14]. | Provides a vast corpus for unsupervised learning of atom embeddings. The concept of atom environments is directly transferable to learning representations for inorganic solids [15] [14]. |

Experimental Protocols for Database Utilization

Protocol 1: Training a Synthesizability Classifier (e.g., SynthNN) with ICSD

This protocol outlines the steps for using the ICSD to train a deep learning model for synthesizability prediction, as demonstrated by SynthNN [1].

Data Acquisition and Curation:

- Obtain the full ICSD database or a relevant subset.

- Extract the chemical formulas of all crystalline inorganic materials, representing the set of synthesized (positive) examples.

- Apply necessary pre-processing, such as removing duplicates and handling non-stoichiometric entries.

Generation of Unsynthesized Examples:

- Create a set of artificially generated chemical formulas that are not present in the ICSD. These serve as the unsynthesized (or unlabeled) class in the dataset.

- The ratio of artificially generated formulas to synthesized formulas (referred to as

N_synth) is a critical hyperparameter [1].

Model Training with Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning:

- Implement a semi-supervised learning approach that treats the unsynthesized materials as unlabeled data.

- Probabilistically reweight the unlabeled examples according to their likelihood of being synthesizable to account for the fact that some may be synthesizable but not yet discovered [1].

- Employ an

atom2vec-style embedding layer as the input to a neural network (SynthNN). This layer learns optimal vector representations for each atom directly from the distribution of chemical formulas. - Train the model to classify formulas as synthesizable or not.

Model Validation:

- Benchmark model performance against baseline methods, such as random guessing and the charge-balancing heuristic.

- Evaluate using standard metrics like precision and recall, while acknowledging that the "unsynthesized" class may contain false negatives [1].

Protocol 2: Integrating DFT Stability from the Materials Project into Predictive Models

This protocol describes how to incorporate thermodynamic stability data from the Materials Project to enhance synthesizability predictions [13].

Feature Extraction from MP:

- For a given list of chemical compositions, query the Materials Project API to retrieve computed properties.

- Extract key stability metrics, most importantly the energy above the convex hull (Ehull), which describes a compound's zero-kelvin thermodynamic stability.

- Extract or calculate other relevant compositional or structural features available through MP or associated tools like

pymatgenandmatminer.

Model Training with Combined Features:

- Combine the DFT-derived stability features (e.g., Ehull) with composition-based features (e.g.,

atom2vecembeddings or features from featurizers like MAGPIE or JARVIS). - Train a machine learning classifier (e.g., ensemble methods or neural networks) to predict synthesizability, using reported materials (e.g., from ICSD) as the positive class.

- The model learns the complex relationship where low Ehull is generally indicative of synthesizability, but also accounts for metastable synthesizable materials and stable-yet-unsynthesized materials [13].

- Combine the DFT-derived stability features (e.g., Ehull) with composition-based features (e.g.,

Screening and Discovery:

- Apply the trained model to screen large sets of hypothetical compounds.

- Identify promising candidates that are predicted to be synthesizable, which may include both stable and metastable compositions, thereby going beyond a simple Ehull filter [13].

Protocol 3: Learning Atom Embeddings (atom2vec) from a Materials Corpus

This protocol is based on the original atom2vec methodology, which can be applied to a database of material compositions like those in the ICSD or PubChem [15].

Corpus Construction:

- Compile a large list of chemical formulas from a chosen database (e.g., all entries in ICSD or a subset of PubChem). This list is the "corpus" analogous to a corpus of text documents.

Defining Atom Environments:

- For each chemical formula, generate atom-environment pairs.

- In a simplified composition-based approach, for a compound like

Bi2Se3, the environment for atomBiis represented as(2)Se3, meaning two central Bi atoms are surrounded by three Se atoms in the remainder of the compound [15].

Building the Atom-Environment Matrix:

- Construct a co-occurrence matrix

X, where each entryXijrepresents the frequency of thei-th atom type appearing in thej-th type of environment across the entire corpus.

- Construct a co-occurrence matrix

Dimensionality Reduction:

- Apply a model-free machine learning method, such as Singular Value Decomposition (SVD), to the reweighted and normalized atom-environment matrix.

- The row vectors corresponding to atoms in the subspace of the

dlargest singular values become thed-dimensional atom embeddings [15]. - These embeddings can be clustered and visualized to show that they capture fundamental chemical properties and periodic trends without prior human knowledge [15].

Workflow Visualization: From Databases to Synthesizability Prediction

The following diagram illustrates the integrative workflow for using these databases to train an atom2vec-informed synthesizability model.

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools and Datasets for Synthesizability Research

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| ICSD [1] | Database | The definitive source for experimentally verified inorganic crystal structures; provides the ground truth for "synthesized" materials. |

| Materials Project (MP) [12] [3] | Database | Provides pre-computed quantum mechanical properties (formation energy, Ehull) for hundreds of thousands of materials, essential for stability-informed models. |

| PubChem [14] | Database | A vast source of molecular structures and atom environments, useful for training general-purpose atom embeddings. |

atom2vec [15] |

Algorithm / Representation | An unsupervised method for learning vector representations of atoms that capture their chemical properties based on co-occurrence in a database. |

pymatgen [12] |

Python Library | A robust library for materials analysis; used for parsing crystal structures, analyzing phase stability, and integrating with MP data. |

matminer [12] [3] |

Python Library | An open-source toolkit for data mining in materials science; used to generate a wide array of composition-based and structure-based numerical features. |

| Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning [1] | Machine Learning Framework | A semi-supervised classification approach critical for handling the lack of confirmed negative examples (unsynthesizable materials) in synthesizability prediction. |

The discovery and development of new materials are fundamental to technological progress in fields ranging from renewable energy to drug development. A pivotal challenge in this endeavor is accurately predicting material synthesizability—determining whether a hypothetical chemical compound can be successfully realized in the laboratory. Traditional methods, which often rely on proxy metrics like charge-balancing or density functional theory (DFT) calculations, face significant limitations; for instance, charge-balancing criteria alone fail to identify over 60% of known synthesized inorganic materials [1].

Inspired by breakthroughs in natural language processing (NLP), a new paradigm has emerged: representing chemical elements as distributed vector embeddings learned from large-scale data. This approach allows machine learning models to capture complex, multifaceted chemical relationships that are difficult to codify through manual feature engineering. Techniques such as atom2vec and SkipAtom demonstrate that the statistical patterns of "co-occurrence" in materials databases or scientific text can yield powerful, meaningful representations of atoms, mirroring how NLP models like Word2Vec learn semantic meaning from word co-occurrence in text corpora [4] [16]. These learned representations form the foundation for highly accurate predictive models of synthesizability and material properties, enabling more efficient and reliable computational screening of novel materials [1].

Theoretical Foundations: From Word Embeddings to Atom Embeddings

Core NLP Concepts and Their Chemical Analogies

The application of NLP principles to materials science relies on a direct conceptual mapping between linguistic and chemical domains.

- Words and Atoms: In NLP, words are the basic units of meaning. In materials informatics, atoms serve an analogous role as the fundamental building blocks [4].

- Documents and Materials: A document is a structured sequence of words. Similarly, a crystalline material, defined by its chemical formula and atomic structure, can be viewed as a "document" where atoms appear in specific structural contexts [4].

- Vocabulary and The Periodic Table: The set of all unique words in a corpus is the vocabulary. In chemistry, the periodic table of elements constitutes the fundamental vocabulary [16].

- Semantic Similarity and Chemical Similarity: In language, words with similar meanings appear in similar contexts (the "distributional hypothesis"). In chemistry, a parallel principle holds: atoms with similar chemical properties will be found in similar structural environments within materials [4]. For example, calcium and strontium, being chemically similar, might both coordinate with oxygen in comparable geometric patterns.

The Skip-gram Model and its Chemical Adaptations

The Skip-gram model, a cornerstone of modern NLP, aims to predict the context words surrounding a given target word within a predefined window. This training objective forces the model to learn vector embeddings that place words with similar contexts close together in a high-dimensional space [4].

This model has been directly adapted for materials science in two primary ways:

SkipAtom: This method replaces the textual corpus with a database of crystal structures. Each material is represented as a graph where atoms are nodes connected by edges based on their proximity (e.g., derived from Voronoi decomposition). The training objective is modified to predict the neighboring atoms of a target atom within this crystal graph. The model learns to maximize the average log probability defined as:$$\frac{1}{| M| }\mathop{\sum}\limits_{m\in M}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{a\in {A}_{m}}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{n\in N(a)}\log p(n| a)$$whereMis the set of materials,A_mis the set of atoms in materialm, andN(a)are the neighbors of atoma[4].atom2vec: This approach uses a similar graph-based context prediction but was notably used to autonomously reproduce the structure of the periodic table. By analyzing the known chemical compounds of 118 elements, the algorithm learned vector embeddings that grouped elements by their chemical properties without any prior chemical knowledge [16].

Advanced Embeddings: From Global to Local Contexts

Recent advancements have extended these core ideas to create more nuanced representations. The Element2Vec framework, for example, processes textual descriptions of elements from sources like Wikipedia using large language models (LLMs). It generates two types of embeddings:

- Global Embedding: A single, general-purpose vector representation for an element derived from its entire text corpus [6].

- Local Embeddings: A set of attribute-specific vectors, each tailored to highlight a particular characteristic (e.g., atomic, chemical, or physical properties) [6].

This approach moves beyond co-occurrence in crystal structures to incorporate rich, descriptive knowledge from scientific literature, providing a more holistic representation of chemical elements.

Experimental Protocols and Application Notes

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing and applying atom representation learning models in synthesizability research.

Protocol 1: Training a SkipAtom Model

Objective: To learn distributed representations of atoms from a database of crystalline structures.

Materials and Input Data:

- Database: A curated collection of crystal structures, such as the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) or the Materials Project [4].

- Software: A computing environment with Python and machine learning libraries (e.g., PyTorch or TensorFlow).

Methodology:

- Graph Construction: For each crystal structure in the database, generate an undirected graph.

- Nodes: Represent individual atoms.

- Edges: Connect atoms that are considered neighbors. A robust method for this is Voronoi decomposition, which identifies nearest neighbors using solid angle weights to determine coordination environments [4].

- Training Pair Generation: Traverse each graph. For every atom (the target), compile all its directly connected neighboring atoms (the context) into (target, context) pairs.

- Model Setup: Implement a shallow neural network with:

- An input layer that accepts a one-hot encoded vector of the target atom.

- A single hidden layer (the projection layer) with a linear activation.

- An output layer with a softmax activation that predicts the probability distribution over all possible context atoms.

- Model Training: Train the network using Maximum Likelihood Estimation to minimize the cross-entropy loss between the predicted context probabilities and the true context atoms. The rows of the projection layer's weight matrix become the final atom embeddings [4].

Protocol 2: Building a Synthesizability Predictor (SynthNN)

Objective: To predict the synthesizability of an inorganic crystalline material given only its chemical formula.

Materials and Input Data:

- Positive Data: Chemical formulas of known synthesized materials, sourced from the ICSD [1].

- Negative Data: Artificially generated chemical formulas that are presumed to be unsynthesized. The ratio of artificial to synthesized formulas (

N_synth) is a key hyperparameter [1]. - Model: A deep learning model that uses learned atom embeddings.

Methodology:

- Data Preparation and Representation:

- Represent each chemical formula using an atom embedding matrix, where each element in the formula is represented by its learned vector (e.g., from

SkipAtomoratom2vec). This matrix is optimized alongside other model parameters [1]. - This approach allows the model to learn an optimal representation of chemical formulas directly from the distribution of synthesized materials, without relying on handcrafted features [1].

- Represent each chemical formula using an atom embedding matrix, where each element in the formula is represented by its learned vector (e.g., from

- Model Training with Positive-Unlabeled Learning:

- This is a Positive-Unlabeled (PU) learning problem. Artificially generated materials are treated as unlabeled data rather than definitive negatives, as some may be synthesizable but not yet discovered.

- The model, often called SynthNN, is trained to classify materials as synthesizable. Unlabeled examples are probabilistically reweighted according to their likelihood of being synthesizable [1].

- Validation: Benchmark the model's precision and recall against baseline methods like random guessing and charge-balancing. SynthNN has been shown to identify synthesizable materials with significantly higher precision than formation energy calculations from DFT [1].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow from data processing to synthesizability prediction, combining the concepts from the protocols above.

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for atom representation learning and synthesizability prediction.

Benchmarking and Data Presentation

The performance of models leveraging atom embeddings is benchmarked against traditional methods and other feature sets. The following table summarizes key quantitative results from the literature.

Table 1: Benchmarking Performance of Different Models and Featurizers on Material Informatics Tasks

| Model/Featurizer | Core Principle | Key Performance Metric | Result | Reference / Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SynthNN (with atom embeddings) | Learns synthesizability from data of all synthesized materials using atom embeddings. | Precision in identifying synthesizable materials | 7x higher precision than DFT-calculated formation energies; outperformed 20 human experts. | [1] |

| Charge-Balancing Baseline | Predicts synthesizability if a material has a net neutral ionic charge. | Coverage of known synthesized inorganic materials | Correctly identifies only ~37% of known synthesized materials. | [1] |

| MatterGen (Generative Model) | Diffusion model generating stable, diverse inorganic materials. | Percentage of generated structures that are Stable, Unique, and New (SUN) | >75% of generated structures are stable; 61% are new materials. | [17] |

| Composition & Structure Featurizer (SAF+CAF) | Generates explainable compositional and structural features for ML. | F1-Score for classifying AB intermetallic crystal structures | 0.983 (XGBoost), comparable to other advanced featurizers. | [3] |

| SOAP Featurizer | Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions; high-dimensional structural descriptor. | F1-Score for classifying AB intermetallic crystal structures | 0.983 (XGBoost), but with 6,633 features (computationally expensive). | [3] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details the essential computational tools and data resources that form the modern materials informatics pipeline.

Table 2: Key Resources for Atom Representation Learning and Synthesizability Prediction

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Synthesizability Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) | Database | A comprehensive collection of published crystal structures. | Serves as the primary source of "positive" data (known synthesized materials) for training models like SynthNN [1]. |

atom2vec / SkipAtom |

Algorithm | Learns atomic embeddings from material structures using NLP-inspired models. | Generates the foundational vector representations of atoms that capture chemical similarity, which are input for predictors [1] [4]. |

| SynthNN | Predictive Model | A deep learning classifier for material synthesizability. | The end-stage model that uses atom embeddings to directly predict the likelihood of a material being synthesizable [1]. |

| mat2vec | Algorithm / Embeddings | Learns atom and material embeddings from scientific literature abstracts. | Provides an alternative, text-based representation of atoms, enriching feature sets [3]. |

| Composition Analyzer Featurizer (CAF) | Software Tool | Generates numerical compositional features from a chemical formula. | Creates human-interpretable features for building explainable ML models, complementing learned embeddings [3]. |

| Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning | Computational Framework | A semi-supervised learning paradigm for datasets with only positive and unlabeled examples. | Critical for handling the lack of definitive negative examples (proven unsynthesizable materials) in synthesizability prediction [1]. |

| Fgfr-IN-5 | Fgfr-IN-5, MF:C25H22N6O3, MW:454.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Antitumor agent-184 | Antitumor agent-184, MF:C22H16N4O2S, MW:400.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The integration of NLP principles into materials science has catalyzed a fundamental shift in how we represent and reason about chemical elements. By treating atoms as words and materials as documents, techniques like atom2vec and SkipAtom automatically learn rich, distributed representations that encapsulate profound chemical relationships. These embeddings have proven to be powerful features for downstream predictive tasks, most notably in addressing the critical challenge of predicting material synthesizability.

Framed within the broader context of atom2vec representation for synthesizability research, this approach demonstrates a significant advantage over traditional methods. Models like SynthNN, built upon these learned embeddings, not only achieve superior precision but also learn foundational chemical principles like charge-balancing and chemical family relationships directly from data [1]. As these representation learning techniques continue to evolve, incorporating multimodal information from text and structure, they pave the way for more reliable, efficient, and accelerated discovery of novel, synthesizable materials.

Building and Deploying Synthesizability Predictors: From SynthNN to DeepSA

The discovery of novel inorganic crystalline materials is a fundamental driver of technological innovation. However, a significant bottleneck exists in transitioning from computationally predicted materials to those that can be experimentally realized. The challenge of predicting synthesizability—determining whether a hypothetical chemical composition can be synthesized as a crystalline solid—remains a critical unsolved problem in materials science [18]. Traditional proxies for synthesizability, such as charge-balancing criteria and thermodynamic stability calculated via density functional theory (DFT), have proven inadequate. Charge-balancing alone identifies only 37% of known synthesized materials, while DFT-based formation energies fail to account for kinetic stabilization and synthetic accessibility [18]. This limitation has created an urgent need for more accurate and efficient predictive methods that can keep pace with high-throughput computational material discovery.

Within this context, the SynthNN model represents a paradigm shift in synthesizability prediction. Developed as a deep learning classification model, SynthNN leverages the entire corpus of known inorganic chemical compositions to directly predict synthesizability from chemical formulas alone, without requiring structural information [18] [19]. By reformulating material discovery as a synthesizability classification task, this approach achieves a critical objective: enabling rapid screening of billions of candidate materials to identify those most likely to be synthetically accessible, thereby increasing the reliability of computational material screening workflows [18].

Architectural Foundation: The atom2vec Representation

At the core of SynthNN's innovative approach is its use of the atom2vec representation framework, which provides a learned, distributed representation of chemical elements [18]. This framework moves beyond traditional fixed chemical descriptors to create an adaptive, data-driven representation optimized specifically for synthesizability prediction.

atom2vec Implementation in SynthNN

The atom2vec framework represents each chemical formula through a learned atom embedding matrix that is optimized alongside all other parameters of the neural network during training [18]. In this architecture:

- Element Embeddings: Each chemical element is represented as a dense vector in a continuous space, with the dimensionality treated as a hyperparameter optimized during model development.

- Composition Representation: Chemical formulas are processed through these embeddings to create a unified representation that captures complex compositional relationships.

- Joint Optimization: The element representations are not pre-trained but are learned jointly with the synthesizability classification task, allowing the model to discover element relationships most relevant to synthesizability.

Remarkably, despite having no explicit chemical knowledge programmed into it, SynthNN learns fundamental chemical principles through this representation. Experimental analyses indicate that the model internalizes concepts of charge-balancing, chemical family relationships, and ionicity directly from the distribution of synthesized materials, utilizing these learned principles to generate synthesizability predictions [18] [20].

Comparative Advantage Over Traditional Representations

The atom2vec framework provides significant advantages over traditional chemical representations:

- Flexibility: Unlike fixed oxidation state tables or manually engineered features, the learned embeddings can adapt to capture complex, non-intuitive patterns in the data.

- Composition Focus: By operating solely on chemical compositions, SynthNN can evaluate materials for which atomic structures are unknown—a critical capability for genuine discovery of novel materials.

- Data-Driven Insights: The model learns which elemental properties and relationships best predict synthesizability without human bias in feature selection.

Model Design and Training Methodology

Neural Network Architecture and Workflow

SynthNN implements a deep learning architecture designed specifically for processing chemical compositions represented through atom2vec embeddings. The model follows a structured workflow from input chemical formula to synthesizability classification, illustrated in the following diagram:

The architectural workflow begins with a chemical formula as input, which is processed through the atom2vec embedding layer to create distributed representations of the constituent elements. These embeddings then pass through multiple feature learning layers that capture complex interactions between elements in the composition. Finally, the classification layer generates a synthesizability probability score, indicating the model's confidence that the input formula can be successfully synthesized [18] [19].

Training Framework: Positive-Unlabeled Learning

A fundamental challenge in synthesizability prediction is the lack of confirmed negative examples—while successfully synthesized materials are documented in databases like the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), failed synthesis attempts are rarely reported [18] [21]. SynthNN addresses this through a positive-unlabeled (PU) learning approach, a semi-supervised learning paradigm that treats unsynthesized materials as unlabeled rather than definitively unsynthesizable [18].

The training process involves:

- Positive Examples: 70,120 synthesized crystalline inorganic materials extracted from the ICSD [18].

- Artificial Negative Examples: Artificially generated unsynthesized materials, treated as unlabeled data in the PU learning framework.

- Probabilistic Reweighting: The model probabilistically reweights unlabeled examples according to their likelihood of being synthesizable, handling the inherent uncertainty in negative example labeling [18].

The ratio of artificially generated formulas to synthesized formulas used in training (referred to as Nâ‚›ynth) is treated as a key hyperparameter, with detailed analysis provided in the supplementary materials of the original publication [18].

Performance Analysis and Benchmarking

Quantitative Performance Metrics

SynthNN demonstrates superior performance compared to traditional synthesizability assessment methods, as quantified through comprehensive benchmarking. The table below summarizes key performance metrics across different prediction approaches:

Table 1: Performance comparison of synthesizability prediction methods

| Method | Precision | Recall | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SynthNN (threshold=0.5) | 0.563 | 0.604 | 7× higher precision than DFT; learns chemical principles | Requires training data [18] [19] |

| Charge-Balancing | 0.37 (on known materials) | N/A | Chemically intuitive; computationally simple | Only identifies 37% of known materials [18] |

| DFT Formation Energy | ~0.08 (7× lower than SynthNN) | ~0.50 | Physics-based; well-established | Misses kinetic stabilization; computationally expensive [18] |

| Human Experts (best performer) | 1.5× lower than SynthNN | N/A | Domain knowledge; contextual understanding | 5 orders of magnitude slower than SynthNN [18] |

The precision-recall tradeoff for SynthNN can be modulated by adjusting the classification threshold, enabling users to optimize for either high-recall exploration or high-precision targeted discovery:

Table 2: SynthNN performance at different classification thresholds

| Threshold | Precision | Recall |

|---|---|---|

| 0.10 | 0.239 | 0.859 |

| 0.30 | 0.419 | 0.721 |

| 0.50 | 0.563 | 0.604 |

| 0.70 | 0.702 | 0.483 |

| 0.90 | 0.851 | 0.294 |

Comparative Analysis with Alternative Approaches

Recent advances in synthesizability prediction have introduced several alternative methodologies. The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models (CSLLM) framework achieves 98.6% accuracy in predicting synthesizability of 3D crystal structures with known atomic positions, significantly outperforming thermodynamic and kinetic stability metrics [22]. However, CSLLM requires complete structural information, limiting its application to materials with known or predicted crystal structures. In contrast, SynthNN's composition-based approach enables screening of entirely novel chemical spaces where structural data is unavailable [18] [22].

Other PU learning approaches for solid-state synthesizability prediction have demonstrated capability in specialized domains. For ternary oxides, a PU learning model trained on human-curated literature data successfully identified 134 likely synthesizable compositions from 4,312 hypothetical candidates [21]. These specialized models benefit from high-quality, domain-specific training data but lack the generalizability of SynthNN across the entire inorganic composition space.

Practical Implementation Protocols

Experimental Setup and Research Reagents

Implementing SynthNN for material discovery workflows requires specific computational resources and data sources, as detailed in the following research reagents table:

Table 3: Essential research reagents for SynthNN implementation

| Reagent Solution | Function | Source/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| ICSD Data | Source of positive training examples; validation | Inorganic Crystal Structure Database [18] |

| Pre-trained SynthNN Weights | Model initialization for prediction | Official GitHub Repository [19] |

| Artificial Negative Generator | Generation of unlabeled examples | Custom implementation per [18] |

| atom2vec Embeddings | Chemical formula representation | Learned during training [18] |

| Python/PyTorch Stack | Model training and inference environment | Standard deep learning framework [19] |

Step-by-Step Prediction Protocol

For researchers applying SynthNN to screen candidate materials, the following protocol provides a standardized approach:

Protocol 1: Synthesizability Screening of Novel Compositions

Input Preparation

- Format chemical formulas using standard notation (e.g., "CsCl", "BaTiO3")

- Ensure formulas represent charge-neutral compositions

- Compose candidate list from generative models or high-throughput computations

Model Inference

- Load pre-trained SynthNN model from official repository

- Process formulas through atom2vec embedding layer