AI-Powered Synthesis: Predicting Pathways for Solution-Based Inorganic Materials

This article explores the transformative role of artificial intelligence and machine learning in predicting synthesis pathways for solution-based inorganic materials.

AI-Powered Synthesis: Predicting Pathways for Solution-Based Inorganic Materials

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of artificial intelligence and machine learning in predicting synthesis pathways for solution-based inorganic materials. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational challenges of inorganic synthesis, the latest data-driven methodologies for precursor and condition prediction, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing AI recommendations, and rigorous validation of these new computational tools. By synthesizing information from cutting-edge research, this review serves as a comprehensive guide to leveraging AI for accelerating the discovery and reliable synthesis of novel inorganic materials, with significant implications for developing advanced biomedical agents and clinical technologies.

The Synthesis Bottleneck: Why Predicting Inorganic Materials is a Grand Challenge

The discovery of novel inorganic materials is pivotal for advancing technologies in renewable energy, electronics, and beyond. Computational and data-driven paradigms have successfully identified millions of candidate materials with promising properties. However, a critical bottleneck remains: the actual synthesis of these predicted materials. The journey from a virtual design to a physically realized compound is hindered by the lack of a general, unifying theory for inorganic materials synthesis, which continues to rely heavily on trial-and-error experimentation. This application note details the latest computational frameworks and data-driven protocols designed to bridge this gap, with a specific focus on solution-based inorganic materials synthesis prediction.

Quantifying the Synthesis Prediction Landscape

The performance of state-of-the-art models for predicting inorganic materials synthesis is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Synthesis Prediction Models

| Model Name | Core Methodology | Key Capability | Reported Accuracy/Performance | Ability to Propose Novel Precursors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retro-Rank-In [1] [2] | Pairwise Ranker in Shared Latent Space | Precursor Ranking & Recommendation | State-of-the-art in out-of-distribution generalization | Yes |

| CSLLM Framework [3] | Specialized Large Language Models (LLMs) | Synthesizability, Method & Precursor Prediction | 98.6% (Synthesizability), >90% (Method), 80.2% (Precursor) | Implied |

| VAE Screening Framework [4] | Variational Autoencoder (VAE) | Synthesis Parameter Screening | 74% accuracy differentiating SrTiO₃/BaTiO₃ syntheses | Not Specified |

| ElemwiseRetro [2] [5] | Element-wise Graph Neural Network | Precursor Template Formulation | Outperforms popularity-based baseline | No |

| Retrieval-Retro [2] | Retrieval with Multi-label Classifier | Precursor Recommendation | Strong performance on known precursors | No |

Core Computational Frameworks and Protocols

The Retro-Rank-In Framework: A Protocol for Generalized Precursor Recommendation

Retro-Rank-In redefines the retrosynthesis problem from a multi-label classification task into a pairwise ranking problem. This allows it to generalize to precursor materials not present in its training data, a critical capability for discovering new compounds [2].

Experimental Protocol:

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- Source: Compile a dataset of inorganic synthesis procedures from scientific literature. For solution-based synthesis, the dataset described by [6] provides 35,675 codified procedures.

- Annotation: Each data point must include the target material and its corresponding set of verified precursor materials.

- Splitting: Employ challenging dataset splits (e.g., based on publication year or structural similarity) to mitigate data leakage and rigorously test out-of-distribution generalization.

Model Architecture and Training:

- Materials Encoder: Utilize a composition-level transformer-based model to generate meaningful vector representations (embeddings) for both target and precursor materials. These embeddings are projected into a shared latent space.

- Pairwise Ranker: Train a ranking model that learns to evaluate the chemical compatibility between a target material and a candidate precursor. The Ranker is trained to score true precursor-target pairs higher than negative (incorrect) pairs.

- Training Objective: Use a pairwise ranking loss, such as a margin ranking loss, to optimize the model.

Inference and Prediction:

- For a novel target material, generate its embedding via the trained encoder.

- Score a large candidate set of potential precursors (including those unseen during training) using the trained Ranker.

- Output a ranked list of precursor sets, where the ranking corresponds to the predicted likelihood of successful synthesis [2].

The CSLLM Framework: A Protocol for Synthesizability and Precursor Prediction

The Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models (CSLLM) framework employs three specialized LLMs to address the synthesis pipeline comprehensively [3].

Experimental Protocol:

Dataset Curation:

- Positive Samples: Collect 70,120 synthesizable crystal structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD), filtering for ordered structures with ≤40 atoms and ≤7 elements.

- Negative Samples: Generate 80,000 non-synthesizable examples by screening over 1.4 million theoretical structures from various databases (e.g., Materials Project) using a pre-trained Positive-Unlabeled (PU) learning model. Select structures with a CLscore < 0.1 as negative examples [3].

Material Representation for LLMs:

- Develop a concise text representation ("material string") for crystal structures that includes essential information on lattice parameters, composition, atomic coordinates, and space group symmetry, avoiding the redundancy of CIF or POSCAR formats.

Model Fine-Tuning:

- Fine-tune three separate LLMs:

- Synthesizability LLM: Takes a material string as input and classifies the structure as synthesizable or not.

- Method LLM: Classifies the probable synthesis method (e.g., solid-state or solution-based).

- Precursor LLM: Identifies suitable precursor materials for a given target.

- Fine-tune three separate LLMs:

The VAE Framework: A Protocol for Screening Synthesis Parameters

This framework uses a Variational Autoencoder (VAE) to compress high-dimensional, sparse synthesis parameter vectors into a lower-dimensional latent space, enabling virtual screening [4].

Experimental Protocol:

Data Acquisition and Feature Encoding:

- Source: Apply natural language processing (NLP) and text-mining pipelines to extract synthesis parameters (e.g., precursors, solvents, concentrations, heating temperatures, times) from scientific literature [6] [4].

- Canonical Feature Vector: Encode each synthesis procedure into a high-dimensional, sparse feature vector.

Data Augmentation for Data Scarcity:

- Augment small datasets (e.g., <200 syntheses for a specific material) by incorporating synthesis data from related material systems. Use ion-substitution compositional similarity and cosine similarity between synthesis descriptors to weight the relevance of the added data [4].

Dimensionality Reduction with VAE:

- Train a VAE to compress the canonical feature vectors into a low-dimensional, continuous latent space. The VAE is trained to reconstruct its inputs after "squeezing" them through a latent bottleneck, learning the most informative combinations of parameters.

Screening and Analysis:

- Use the compressed latent representations as inputs for machine learning tasks, such as classifying the target material of a synthesis procedure or identifying correlations between synthesis parameters and outcomes [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Components for Computational Synthesis Prediction Research

| Item/Tool | Function in Research | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Structured Synthesis Databases | Provides labeled data for training and evaluating models. | Solution-based synthesis dataset (35,675 procedures) [6]; ICSD for confirmed crystal structures [3]. |

| Text-Mining Pipelines | Automates extraction of structured synthesis data from unstructured scientific literature. | NLP tools (BERT, BiLSTM-CRF) for Materials Entity Recognition (MER) and action extraction [6]. |

| Pre-trained Material Embeddings | Provides chemically meaningful vector representations of materials, incorporating domain knowledge. | Embeddings pretrained on large computational databases (e.g., Materials Project) can be fine-tuned [2]. |

| Large Language Models (LLMs) | Fine-tuned for specific tasks like synthesizability classification and precursor prediction. | Models like LLaMA, fine-tuned on specialized material strings [3]. |

| Positive-Unlabeled (PU) Learning Models | Generates negative samples (non-synthesizable structures) for model training, a major challenge in the field. | Used to assign a CLscore for screening non-synthesizable theoretical structures [3]. |

| 10-Nitrolinoleic acid | 10-Nitrolinoleic Acid|PPARγ Agonist|774603-04-2 | |

| 2-Chloro-6-fluorobenzaldehyde | 2-Chloro-6-fluorobenzaldehyde, CAS:387-45-1, MF:C7H4ClFO, MW:158.56 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

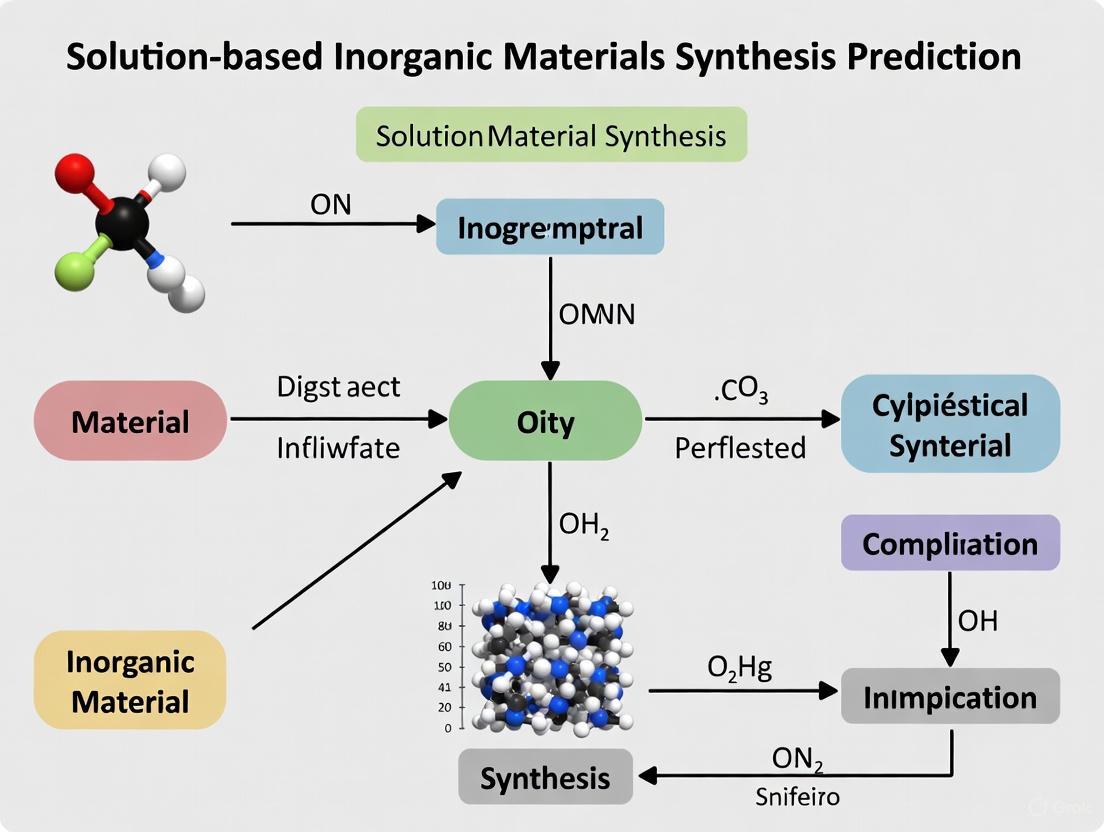

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational and experimental workflow for bridging the virtual design to actual synthesis gap, incorporating elements from the featured frameworks.

The discovery and synthesis of new inorganic materials are critical for advancing technologies in renewable energy, electronics, and catalysis [2]. However, a fundamental bottleneck persists: the lack of a unifying retrosynthesis theory for inorganic materials, which stands in stark contrast to the well-established principles governing organic chemistry [2] [7]. In organic chemistry, retrosynthesis is a rational, step-by-step process of deconstructing a target molecule into simpler, commercially available precursors through a sequence of well-understood reaction mechanisms [8]. This process is underpinned by a robust theoretical framework that allows for the logical disconnection of covalent bonds.

Inorganic solid-state chemistry, particularly for materials like complex oxides, lacks this foundational framework. The synthesis largely remains a one-step process where a set of precursors are mixed and reacted to form a target compound, with no general, unifying theory to guide the selection of these precursors or predict reaction pathways [2] [9]. This complexity is compounded by the fact that synthesis is influenced by a wide array of factors beyond thermodynamics, including kinetics, precursor selection, and reaction conditions [9] [10]. Consequently, the field has historically relied on empirical trial-and-error experimentation, which is slow, costly, and inefficient. This article explores the fundamental reasons for this disparity, reviews modern data-driven approaches that aim to bridge this knowledge gap, and provides practical protocols for researchers working in solution-based inorganic materials synthesis prediction.

The Fundamental Divergence: Why Inorganic Chemistry Lacks a Unifying Retrosynthetic Theory

The challenge of inorganic retrosynthesis is rooted in fundamental differences in bonding and structure when compared to organic molecules.

- Periodic Structure and Bonding Energetics: Organic molecules exist as discrete, individual structures with well-defined covalent bonds. This allows their synthesis to be broken down into multiple steps involving smaller building blocks. In contrast, inorganic materials adopt extended periodic structures (1D, 2D, or 3D arrangements of atoms). In a crystal structure like quartz, bonds "look the same in every direction," making it chemically ambiguous to identify discrete building blocks for a retrosynthetic process [7]. Furthermore, the clear energetic discrimination between strong covalent bonds and weak intermolecular forces that guides organic retrosynthesis is often absent in inorganic networks [7].

- The "Building Block" Dilemma: The literature frequently uses terms like "building blocks" or "secondary building units" (SBUs) for inorganic crystals. However, these are often geometrical constructs rather than proven chemical intermediates. There is typically no experimental evidence that these SBUs exist as real chemical species during the crystal growth process [7]. Therefore, reducing a crystal to its ultimate chemical constituents is not straightforward.

- Under-Determined Nature of the Problem: Unlike in organic chemistry, where a target molecule typically has one definitive structure, a target inorganic composition can often be synthesized through multiple pathways using different precursor sets. The feasibility of a route depends on factors such as cost, yield, and safety, making the problem one of ranking plausible options rather than finding a single correct answer [2].

Table 1: Core Differences Between Organic and Inorganic Retrosynthesis

| Aspect | Organic Retrosynthesis | Inorganic Retrosynthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Well-established theory of covalent bond disconnection [8] | Lacks a unifying theory; relies on heuristics and data [2] |

| Process | Multi-step sequence from simple starting materials [8] | Largely a one-step process from solid or solution precursors [2] |

| Key Units | Synthons (idealized fragments) and real reagents [8] | Hypothetical "building blocks" or precursor sets [7] |

| Primary Drivers | Reaction mechanisms and functional group compatibility | Thermodynamics, kinetics, and precursor availability [9] |

| Output | A single, logically derived synthetic pathway | Multiple ranked precursor sets with associated confidence scores [2] [11] |

Computational Frameworks Bridging the Theory Gap

To overcome the lack of theory, machine learning (ML) models are being developed to learn the implicit "rules" of inorganic synthesis from historical data. These models reformulate retrosynthesis from a classification task into a more flexible ranking task, enabling the recommendation of novel precursors.

Ranking-Based Approaches (Retro-Rank-In)

The Retro-Rank-In framework addresses key limitations of previous models that could only recombine precursors seen during training. Its core innovation is learning a pairwise ranker that evaluates the chemical compatibility between a target material and candidate precursors [2].

- Architecture: It consists of a composition-level transformer-based materials encoder that generates meaningful representations for both targets and precursors, embedding them in a shared latent space. A separate ranker then learns to predict the likelihood that a target-precursor pair can co-occur in a viable synthesis [2].

- Key Advantage: This design allows the model to score and rank entirely new precursors not present in the training data, a crucial capability for exploring the synthesis of novel compounds [2]. For example, for the target \ce{Cr2AlB2}, Retro-Rank-In correctly predicted the verified precursor pair \ce{CrB + \ce{Al}}, despite never having seen this specific pair during training [2].

Template-Based and LLM-Based Approaches

Other methods adapt concepts from organic chemistry to the inorganic domain.

- ElemwiseRetro: This approach formulates retrosynthesis by first identifying "source elements" in the target that must be provided by precursors, and "non-source elements" that may come from the reaction environment. A graph neural network then selects appropriate anionic frameworks ("precursor templates") for each source element from a predefined library. The joint probability of the resulting precursor set is calculated, providing a confidence score for ranking [11]. This method demonstrated a top-1 accuracy of 78.6% and a top-5 accuracy of 96.1%, significantly outperforming a popularity-based baseline [11].

- Crystal Synthesis Large Language Models (CSLLM): This framework leverages three specialized LLMs to predict the synthesizability of arbitrary 3D crystal structures, suggest possible synthetic methods (solid-state or solution), and identify suitable precursors. The Synthesizability LLM achieves a state-of-the-art accuracy of 98.6%, significantly outperforming traditional screening based on thermodynamic stability or kinetics [10].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Selected Inorganic Retrosynthesis Models

| Model | Core Approach | Key Performance Metric | Ability to Propose Novel Precursors |

|---|---|---|---|

| ElemwiseRetro [11] | Template-based GNN | 78.6% Top-1 Exact Match Accuracy | Limited to predefined template library |

| Retro-Rank-In [2] | Pairwise Ranking | State-of-the-art in out-of-distribution generalization | Yes |

| CSLLM (Synthesizability LLM) [10] | Fine-tuned Large Language Model | 98.6% Synthesizability Prediction Accuracy | Yes (via precursor LLM component) |

Figure 1: A generalized workflow for computational prediction of inorganic synthesis recipes, highlighting the key steps from target material to a ranked precursor recommendation.

Experimental Protocols for Validation

The following protocols detail how to computationally and experimentally validate predicted synthesis recipes for inorganic materials.

Computational Validation of Predicted Precursors

This protocol ensures thermodynamic plausibility before experimental investment.

- Objective: To assess the thermodynamic stability of a target material and its precursors using density functional theory (DFT) calculations.

- Materials & Software:

- Software: DFT calculation package (e.g., VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO).

- Input Files: Crystal structure files (CIF/POSCAR) for the target and all predicted precursor compounds.

- Database: Access to a materials database (e.g., Materials Project) for reference energies.

- Procedure:

- Geometry Optimization: Perform a full geometry optimization for the target material and all precursor compounds to obtain their ground-state energies.

- Calculate Formation Energy: Compute the formation energy (ΔHf) of the target material relative to its elements in their standard states.

- Calculate Energy Above Hull: Determine the energy above the convex hull (Ehull) to confirm the target's thermodynamic stability. An Ehull ≥ 0 eV/atom suggests stability, though metastable materials (Ehull > 0) can be synthesizable [9] [10].

- Verify Precursor Stability: Check that all proposed precursor compounds are stable (i.e., they have an Ehull close to or ≥ 0 eV/atom).

- Assess Reaction Energy: For the proposed reaction combining precursors A and B to form target C (A + B → C), calculate the reaction energy ΔEr = EC - (EA + EB). A significantly positive ΔEr indicates a thermodynamically unfavorable reaction.

Laboratory Synthesis from CSLLM-Predicted Recipes

This protocol guides the experimental synthesis of a target material using precursors and methods suggested by an LLM like CSLLM.

- Objective: To synthesize a target inorganic crystal material using solid-state or solution-based methods as predicted by a computational model.

- Materials & Reagents:

- Precursors: High-purity solid powders or solutions as identified by the Precursor LLM (e.g., for \ce{Li7La3Zr2O12}, these would be \ce{Li2CO3}, \ce{La2O3}, and \ce{ZrO2}) [10] [11].

- Equipment: Mortar and pestle or ball mill, high-temperature furnace or autoclave, alumina or platinum crucibles, fume hood, glove box (for air-sensitive materials).

- Procedure:

- Weighing and Mixing:

- Weigh out precursor powders according to the stoichiometry required to form the target compound.

- For solid-state synthesis, transfer the powders to a mortar and grind vigorously for 20-30 minutes to achieve a homogeneous mixture. Alternatively, use a ball mill for several hours.

- Calcination:

- Transfer the mixed powder to a suitable crucible.

- Place the crucible in a furnace and heat according to a controlled temperature program. This often involves a ramp to an intermediate temperature (e.g., 500-900°C) for several hours to decompose carbonates or nitrates, followed by cooling, re-grinding, and a final high-temperature firing (e.g., 1000-1500°C) for 12-48 hours to facilitate crystal growth [11].

- Solution-Based Synthesis (if applicable):

- For sol-gel or hydrothermal methods, dissolve precursors in appropriate solvents (e.g., water, alcohols) [7].

- Stir the solution to form a gel or transfer it to an autoclave for heating under autogenous pressure.

- Recover the product by filtration or centrifugation, and dry.

- Characterization:

- Perform X-ray diffraction (XRD) on the final product to confirm the formation of the target crystal structure and phase purity.

- Use scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) to analyze morphology and elemental composition.

- Weighing and Mixing:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Computational and Experimental Inorganic Synthesis Research

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Precursor Salts/Oxides (e.g., \ce{Li2CO3}, \ce{La2O3}, \ce{ZrO2}) [11] | Source of elemental components for the target material; purity is critical to avoid side reactions. |

| CIF (Crystallographic Information File) [10] | Standard text file format representing crystal structure information; input for structure-based models. |

| POSCAR File [10] | Input file for VASP DFT calculations, containing crystal structure and atomic coordinates. |

| Material String [10] | A concise text representation of a crystal structure integrating lattice parameters, composition, atomic coordinates, and symmetry; used for efficient LLM fine-tuning. |

| Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) [9] [10] | A comprehensive database of experimentally reported inorganic crystal structures; used for model training and validation. |

| 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid | 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid, CAS:22059-21-8, MF:C4H7NO2, MW:101.10 g/mol |

| Azidoethyl-SS-ethylazide | Azidoethyl-SS-ethylazide, MF:C4H8N6S2, MW:204.3 g/mol |

The absence of a unifying retrosynthesis theory for inorganic materials, unlike the mature framework in organic chemistry, presents a significant but surmountable challenge. The complex, periodic nature of inorganic solids and the under-determined nature of their synthesis pathways preclude simple, rule-based solutions. However, as outlined in this article, the field is undergoing a transformative shift driven by advanced computational approaches. Frameworks like Retro-Rank-In, ElemwiseRetro, and CSLLM are demonstrating that machine learning can effectively learn the implicit chemical principles of inorganic synthesis from data, enabling the prediction and ranking of viable synthesis pathways with quantifiable confidence. By integrating these computational protocols for precursor prediction and validation with robust experimental synthesis methods, researchers can systematically accelerate the discovery and synthesis of novel inorganic materials, thereby closing the critical gap between computational design and experimental realization.

In solution-based inorganic materials synthesis, the interplay between thermodynamic and kinetic stability presents a fundamental challenge for predicting and controlling reaction outcomes. Thermodynamic stability dictates the inherent favorability of a reaction, while kinetic stability governs the feasible pathway and rate at which the product forms. This application note delineates these concepts, provides protocols for their experimental investigation, and integrates these principles with modern data-driven approaches for synthesis prediction. By framing this discussion within the context of inorganic materials research, we equip scientists with the conceptual and practical tools to navigate complex synthesis landscapes, accelerating the development of novel materials for applications in drug development and beyond.

Conceptual Framework: Kinetic and Thermodynamic Stability

Definitions and Energetic Landscape

In chemical synthesis, stability has two distinct meanings, each critical for understanding reaction behavior.

Thermodynamic Stability is a measure of the global energy minimum of a system under given conditions. It concerns the overall Gibbs Free Energy change (ΔG) of a reaction. A reaction is thermodynamically favorable (product-favored) if ΔG is negative, indicating the products are more stable than the reactants [12] [13]. This concept describes the system's initial and final states but provides no information about the reaction rate or pathway [14].

Kinetic Stability refers to the reactivity or inertness of a substance, determined by the activation energy (Ea) of the reaction pathway. A high activation energy creates a significant barrier, resulting in a slow reaction rate even if the process is thermodynamically favorable. A substance in such a state is described as kinetically stable or inert [15] [13].

The relationship between these concepts is visualized in the energy diagram below, which maps the energetic pathway of a reaction involving kinetically stable reactants forming thermodynamically stable products.

Comparative Analysis

The following table summarizes the core differences between kinetic and thermodynamic stability, which are often conflated but have distinct implications for synthesis planning.

| Feature | Kinetic Stability | Thermodynamic Stability |

|---|---|---|

| Governing Factor | Reaction rate & activation energy (Ea) [12] [14] | Overall free energy change (ΔG) [12] [14] |

| Describes | Reactivity & reaction pathway [15] | Inherent favorability & final equilibrium state [15] |

| Reaction Speed | Slow if stable (high Ea), fast if labile (low Ea) [13] | Independent of reaction speed [12] |

| Spontaneity | Does not determine spontaneity | Determines spontaneity (if ΔG < 0) [12] |

| Practical Implication | Determines if a reaction will proceed at a usable rate under given conditions. | Determines if a reaction can proceed to a significant extent at all. |

Illustrative Examples

- Diamond to Graphite Conversion: The conversion of diamond to graphite has a negative ΔG at ambient conditions, making graphite the thermodynamically stable form of carbon. However, diamond is kinetically stable because the activation energy for rearranging the covalent carbon lattice is exceedingly high. Thus, diamond persists metastably [12].

- Methane Combustion: The combustion of methane with oxygen is highly exothermic (ΔG° = -800.8 kJ/mol), making it thermodynamically unstable in air. Yet, methane is kinetically stable and exists in the atmosphere because the reaction requires an initial input of energy (e.g., a spark) to overcome the high activation energy barrier [12].

Integration with Computational Synthesis Prediction

The principles of stability are central to overcoming the bottleneck in inorganic materials discovery. While high-throughput computations can predict millions of potentially stable compounds, determining viable synthesis routes remains a challenge due to the lack of a unifying theory for inorganic synthesis [2]. Data-driven machine learning (ML) approaches are now being developed to learn these patterns from published literature.

The Data-Driven Paradigm

Large-scale, text-mined datasets of inorganic synthesis recipes are foundational to this new paradigm. These datasets codify information from scientific publications—including target materials, precursors, synthesis actions, and conditions—into a machine-readable format [6] [16]. For instance, one such dataset contains 35,675 solution-based synthesis procedures extracted from over 4 million papers [6]. This data provides the necessary foundation for ML models to learn the complex relationships between reaction conditions and the kinetic and thermodynamic factors that control successful synthesis.

Machine Learning for Precursor Recommendation

A key task in synthesis planning is precursor recommendation. ML models like Retro-Rank-In are being developed to address this. Unlike earlier models limited to recombining known precursors, Retro-Rank-In learns a pairwise ranking function in a shared latent space of materials, enabling it to recommend novel, chemically viable precursor sets for a target material. This flexibility is crucial for exploring new synthesis pathways and understanding the kinetic and thermodynamic feasibility of proposed reactions [2].

The workflow below illustrates how these computational tools integrate stability principles and empirical data to predict synthesis pathways.

Experimental Protocols & the Scientist's Toolkit

High-Throughput Experimental (HTE) Screening for Kinetic and Thermodynamic Control

Purpose: To efficiently map the parameter space of a synthesis reaction—including precursor stoichiometry, concentration, temperature, and time—to identify conditions that yield the desired phase by navigating kinetic and thermodynamic hurdles [17].

Detailed Protocol:

- Experiment Design:

- Utilize an Experiment Designer agent or software to define a multi-dimensional parameter grid based on literature surveys and chemical intuition [18].

- Common variables for solution-based synthesis include: precursor identities and ratios, solvent composition, pH, temperature, reaction time, and pressure (for hydrothermal reactions).

- Employ a design-of-experiments (DoE) approach to maximize information gain while minimizing the number of experiments.

Automated Reaction Execution:

- Employ a high-throughput batch platform (e.g., Chemspeed SWING, Zinsser Analytic) equipped with a liquid handling robot [17].

- Use microtiter well plates (e.g., 96-well plates) as reaction vessels. The liquid handler automatically dispenses calculated volumes of precursor solutions and solvents into the wells according to the experimental design [17].

- Seal the plates and transfer them to a modular reactor block capable of heating and mixing under controlled atmospheres.

Reaction and Quenching:

- Execute reactions for the predetermined time and temperature profile.

- For kinetic studies, samples may be quenched at different time intervals to track phase evolution and product yield over time.

Product Characterization and Analysis:

- Post-reaction, the products (often precipitates) are typically washed and dried.

- Utilize high-throughput characterization techniques, such as parallel powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) to identify crystalline phases and assess phase purity.

- Employ other techniques like automated Raman spectroscopy or UV-Vis as needed.

- An automated Spectrum Analyzer or similar algorithm can process the large volume of characterization data to determine the success of each reaction condition [18].

Data Integration and Interpretation:

- A Result Interpreter agent can correlate reaction outcomes (e.g., yield, phase purity) with input conditions to identify optimal synthesis windows and propose explanations based on kinetic and thermodynamic principles [18].

- The resulting dataset can be used to refine ML models for future synthesis predictions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and their functions in solution-based inorganic synthesis, which can be screened using the HTE protocol above.

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function in Synthesis |

|---|---|

| Metal Salts (e.g., Nitrates, Chlorides, Acetates) | Serve as soluble precursors, providing the metal cations for the final inorganic material framework [6]. |

| Structure-Directing Agents (SDAs) | Organic templates (e.g., amines, quaternary ammonium salts) that guide the formation of specific porous architectures, like zeolites, often through kinetic trapping of metastable phases. |

| Mineralizers (e.g., Hydrofluoric Acid, Fluoride Salts) | Enhance the solubility and mobility of precursor species in hydrothermal syntheses, facilitating crystal growth and enabling the formation of thermodynamically stable phases [16]. |

| Solvents (e.g., Water, Alcohols, DMF) | The reaction medium that solvates precursors; its properties (polarity, boiling point, viscosity) can influence reaction kinetics and the stability of intermediate species [6]. |

| Precipitating Agents (e.g., Urea, NHâ‚„OH) | Slowly alter the solution chemistry (e.g., pH) to induce a controlled, homogeneous precipitation, which can favor the formation of pure, crystalline phases over amorphous by-products. |

| Capping Agents (e.g., Oleic Acid, CTAB) | Bind to the surface of growing nanocrystals to control their size, shape, and prevent aggregation by modulating surface energy—a key kinetic control strategy [6]. |

| Sulfo-Cyanine5.5 carboxylic acid | Sulfo-Cyanine5.5 carboxylic acid, MF:C40H39K3N2O14S4, MW:1017.3 g/mol |

| mDPR(Boc)-Val-Cit-PAB | mDPR(Boc)-Val-Cit-PAB, MF:C30H43N7O9, MW:645.7 g/mol |

For researchers and drug development professionals, a clear understanding of kinetic and thermodynamic stability is not merely academic; it is a practical necessity for designing efficient syntheses. Thermodynamic analysis identifies which materials can be formed, while kinetic analysis determines which phases are formed under accessible conditions and how to navigate around kinetic barriers. The advent of large-scale synthesis data and machine learning models offers a powerful new lens through which to view these classical concepts. By integrating high-throughput experimentation with predictive computational tools, scientists can systematically explore synthesis landscapes, moving beyond heuristic approaches to a more rational and accelerated design of novel inorganic materials.

The acceleration of materials discovery through computational methods has shifted the critical bottleneck to predictive synthesis—the ability to determine how to synthesize computationally predicted materials. While high-throughput computation can design novel materials with promising properties, these predictions offer no guidance on practical synthesis routes involving precursors, temperatures, or reaction times [19]. Text mining scientific literature offers a promising pathway to codify the collective synthesis knowledge dispersed across millions of publications into structured, machine-readable databases [6]. This application note details the methodologies, challenges, and resources for constructing structured synthesis databases for solution-based inorganic materials, framed within broader efforts to enable data-driven synthesis prediction.

The Synthesis Data Landscape

Large-scale databases of inorganic materials synthesis remain scarce compared to their organic chemistry counterparts, where databases like SciFinder and Reaxys have enabled significant advances in retrosynthesis prediction [6] [19]. The following table quantifies key text-mined synthesis datasets and their characteristics:

Table 1: Text-Mined Materials Synthesis Datasets

| Dataset | Number of Recipes | Synthesis Type | Extracted Information | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solution-Based Inorganic Synthesis | 35,675 | Solution-based (hydrothermal, sol-gel, precipitation) | Precursors, targets, quantities, synthesis actions, reaction formulas | [6] |

| Solid-State Synthesis | 31,782 | Solid-state ceramics | Precursors, targets, operations, attributes, balanced reactions | [19] |

These datasets were extracted from over 4 million scientific articles using specialized natural language processing (NLP) pipelines [6] [19]. However, they face challenges in satisfying the "4 Vs" of data science: Volume, Variety, Veracity, and Velocity, which limits their direct utility in training machine learning models for predictive synthesis of novel materials [19].

Experimental Protocols for Text Mining Synthesis Data

Content Acquisition and Preprocessing

Protocol 1: Literature Procurement and Text Conversion

- Content Acquisition: Obtain full-text permissions from major scientific publishers (e.g., Wiley, Elsevier, Royal Society of Chemistry). Use customized web-scrapers (e.g., Borges) to download materials-relevant papers published after 2000 in HTML/XML format [6].

- Format Conversion: Convert articles from HTML/XML to raw text using specialized toolkits (e.g., LimeSoup) that account for publisher-specific formatting standards [6].

- Storage: Store full-text content and metadata (journal, title, abstract, authors) in a MongoDB database collection for subsequent processing [6].

Synthesis Paragraph Identification

Protocol 2: BERT-Based Paragraph Classification

- Model Pre-training: Pre-train a Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) model on full-text paragraphs from 2 million papers in a self-supervised manner by predicting masked words from context [6].

- Fine-tuning: Fine-tune the classifier on 7,292 paragraphs manually labeled as "solid-state synthesis," "sol-gel precursor synthesis," "hydrothermal synthesis," "precipitation synthesis," or "none of the above" [6].

- Classification: Apply the fine-tuned model to identify paragraphs containing solution-based synthesis descriptions, achieving an F1 score of 99.5% [6].

Synthesis Procedure Extraction Pipeline

The core extraction pipeline involves multiple NLP components to transform unstructured text into structured synthesis recipes, as visualized below:

Diagram Title: Text-Mining Pipeline for Synthesis Data Extraction

Protocol 3: Materials Entity Recognition (MER)

- Tokenization and Embedding: Transform word tokens into digitized BERT embedding vectors trained on materials science domain text [6].

- Entity Identification: Use a bi-directional long-short-term memory neural network with conditional random field layer (BiLSTM-CRF) to identify tokens as materials entities or regular words, replacing entities with

<MAT>tags [6] [19]. - Role Classification: Apply a second BERT-based BiLSTM-CRF network to classify

<MAT>tags as target, precursor, or other materials using context clues [6] [19]. - Training Data: Train models on 834 annotated solid-state synthesis paragraphs and 447 solution-based synthesis paragraphs with paper-wise train/validation/test splits [6].

Protocol 4: Synthesis Action and Attribute Extraction

- Word Embedding Training: Re-train Word2Vec models on approximately 400,000 synthesis paragraphs of four synthesis types using the Gensim library [6].

- Action Classification: Implement a recurrent neural network that processes sentences word-by-word, labeling verb tokens as: not-operation, mixing, heating, cooling, shaping, drying, or purifying [6].

- Dependency Parsing: Use SpaCy library to parse dependency sub-trees for each identified synthesis action [6].

- Attribute Extraction: Apply rule-based regular expressions to extract temperature, time, and environment attributes from the dependency trees [6].

Protocol 5: Material Quantity Extraction

- Syntax Tree Construction: Build syntax trees for each sentence in synthesis paragraphs using the NLTK library [6].

- Sub-tree Identification: Algorithmically cut syntax trees into the largest sub-trees containing only one material entity by traversing upward from material leaf nodes [6].

- Quantity Assignment: Search for quantities (molarity, concentration, volume) within each sub-tree and assign them to the unique material entity [6].

Database Construction and Reaction Balancing

Protocol 6: Synthesis Recipe Compilation

- Formula Conversion: Convert material entity text strings into chemical data structures using a specialized material parser toolkit, capturing formula, composition, and ion information [6].

- Precursor-Target Pairing: Pair targets with precursor candidates containing at least one common element (excluding hydrogen and oxygen) [6].

- Reaction Balancing: Build balanced chemical reaction formulas, including volatile atmospheric gasses when necessary, to complete the stoichiometric representation [6] [19].

- JSON Serialization: Compile all extracted information into a standardized JSON database entry containing targets, precursors, quantities, operations, attributes, and balanced reactions [19].

Advanced Applications: Large Language Models for Synthesis Prediction

Recent advancements leverage Large Language Models (LLMs) to predict synthesizability and suggest synthesis pathways:

Protocol 7: LLM-Based Synthesizability Prediction

- Data Preparation: Convert CIF-formatted crystal structures from databases (e.g., Materials Project) to text descriptions using tools like Robocrystallographer [20].

- Model Fine-tuning: Fine-tune GPT-4o-mini models (StructGPT) on text descriptions of crystal structures for synthesizability classification as a positive-unlabeled learning problem [20].

- Embedding Generation: Alternatively, generate text embeddings using models like text-embedding-3-large and train separate positive-unlabeled classifiers, which may outperform fine-tuned LLMs while reducing costs by 57-98% [20].

- Explanation Generation: Use fine-tuned LLMs to generate human-readable explanations for synthesizability predictions, extracting underlying physical rules to guide materials design [20].

Critical Evaluation of Text-Mined Synthesis Data

Despite technical advances, text-mined synthesis databases face significant challenges that impact their utility for predictive modeling:

Table 2: Limitations of Text-Mined Synthesis Data

| Limitation | Description | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Volume | Only 28% of identified solid-state synthesis paragraphs yield balanced chemical reactions (15,144 from 53,538) [19]. | Insufficient data for robust machine learning model training. |

| Variety | Historical research bias toward certain material classes and synthesis conditions [19]. | Limited generalizability to novel materials or unconventional synthesis approaches. |

| Veracity | Extraction errors from ambiguous language, abbreviations, and incomplete reporting in literature [6] [19]. | Noisy data requiring extensive cleaning and validation. |

| Velocity | Static snapshots that don't continuously incorporate newly published knowledge [19]. | Rapid obsolescence compared to the pace of materials research publication. |

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Text Mining Synthesis Data

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Borges | Customized web-scraper for automated paper downloads | Content acquisition from publisher websites [6] |

| LimeSoup | HTML/XML to text conversion toolkit | Format-specific text extraction from journal articles [6] |

| BERT Models | Pre-trained transformer models for language understanding | Paragraph classification and entity recognition [6] |

| BiLSTM-CRF Networks | Neural sequence labeling architecture | Materials entity recognition and classification [6] [19] |

| SpaCy | Natural language processing library | Dependency parsing for action and attribute extraction [6] |

| NLTK | Natural language toolkit | Syntax tree construction for quantity extraction [6] |

| Robocrystallographer | Crystal structure description generator | Text representation of crystal structures for LLM input [20] |

| GPT-4o-mini | Large language model | Fine-tuning for synthesizability prediction and explanation [20] |

Text mining scientific literature to build structured synthesis databases represents a transformative approach to addressing the predictive synthesis bottleneck in inorganic materials discovery. While current datasets face challenges in volume, variety, veracity, and velocity, continued advances in natural language processing—particularly the integration of large language models—are progressively enhancing the quality and utility of these resources. The protocols outlined herein provide a roadmap for researchers to construct, expand, and utilize these databases, ultimately accelerating the design and synthesis of novel functional materials.

The ability to predict whether a hypothetical inorganic material can be successfully realized in a laboratory, a property known as synthesizability, is a cornerstone of accelerated materials discovery. Traditional approaches have relied on physico-chemical heuristics like the Pauling Rules or charge-balancing criteria [21]. However, these simplified rules are often outdated; more than half of the experimentally synthesized materials in modern databases violate these criteria [21]. Thermodynamic stability, often proxied by a negative formation energy or a minimal distance from the convex hull, has also been used as a synthesizability indicator. Yet, this ignores critical kinetic factors and technological constraints, leading to a significant gap between computational prediction and experimental realization [21] [22].

This document outlines the paradigm shift from these traditional heuristics to modern, data-driven classifications of synthesizability, framed within solution-based inorganic materials synthesis. We detail the protocols, datasets, and machine learning models that are defining this new frontier, providing researchers with the application notes needed to navigate this evolving landscape.

The foundation of any data-driven approach is a robust, large-scale dataset. The following table summarizes key quantitative information from recent foundational work.

Table 1: Key Datasets for Data-Driven Synthesizability Prediction

| Dataset/Model Name | Size | Material System | Key Extracted Information | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solution-Based Synthesis Procedures Dataset | 35,675 procedures | Solution-based inorganic materials | Precursors, target materials, quantities, synthesis actions (e.g., mixing, heating), action attributes (temp, time), reaction formulae [6] [23] | Scientific literature |

| SynCoTrain (Model) | Training: 10,206 experimental (positive) and 31,245 unlabeled data points | Oxide crystals | N/A (Uses data from ICSD accessed via Materials Project API) [21] | ICSD/Materials Project |

| Retro-Rank-In (Model) | Not specified in detail | Inorganic compounds | Precursor sets for target materials [2] | Scientific literature |

The performance of modern models is evaluated against specific benchmarks. The metrics below are critical for assessing their utility in a research setting.

Table 2: Key Metrics for Evaluating Synthesizability Prediction Models

| Model | Core Approach | Key Performance Highlights | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| SynCoTrain [21] | Semi-supervised PU Learning with dual GCNN co-training (ALIGNN & SchNet) | High recall on internal and leave-out test sets; mitigates model bias; addresses lack of negative data. | Synthesizability classification for oxide crystals. |

| Retro-Rank-In [2] | Ranking precursor-target pairs in a unified embedding space | State-of-the-art in out-of-distribution generalization; can recommend precursors not seen in training. | Precursor recommendation and retrosynthesis planning. |

Experimental & Computational Protocols

Protocol: Constructing a Synthesis Dataset via Text-Mining

This protocol describes the automated pipeline for building a large-scale dataset of solution-based synthesis procedures from scientific literature, as detailed in Scientific Data [6].

1. Content Acquisition:

- Tools: Custom web-scraper (Borges), LimeSoup toolkit for HTML/XML-to-text conversion.

- Procedure: Download journal articles in HTML/XML format from publishers (e.g., Wiley, Elsevier, RSC) with consent. Use LimeSoup to parse full text and metadata, storing results in a MongoDB database. A cutoff year (e.g., 2000) is recommended to minimize OCR errors.

2. Paragraph Classification:

- Objective: Identify paragraphs describing solution synthesis (e.g., sol-gel, hydrothermal, precipitation).

- Model: A Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) model, pre-trained on materials science text and fine-tuned on a labeled set of ~7,292 paragraphs.

- Output: Paragraphs classified by synthesis type with a reported F1 score of 99.5% [6].

3. Synthesis Procedure Extraction:

- Materials Entity Recognition (MER): A two-step BERT-based model identifies and classifies material entities as "target," "precursor," or "other."

- Synthesis Action Extraction: A recurrent neural network with Word2Vec embeddings labels verb tokens as synthesis actions (mixing, heating, cooling, etc.). A dependency tree parser (SpaCy) extracts action attributes (temperature, time, environment).

- Quantity Extraction: A rule-based approach traverses sentence syntax trees (using NLTK) to assign numerical quantities (molarity, concentration, volume) to the identified material entities.

4. Reaction Formula Building:

- Procedure: An in-house material parser converts text strings of materials into structured chemical data. Precursor candidates are paired with targets based on shared elements (excluding H and O), and a balanced reaction formula is computed for each procedure [6].

Protocol: Predicting Synthesizability with SynCoTrain

This protocol covers the semi-supervised prediction of synthesizability for oxide crystals using the SynCoTrain model, which addresses the critical challenge of lacking negative data [21].

1. Data Curation:

- Data Source: Access the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) via the Materials Project API.

- Filtering: Select oxide crystals where oxidation states are determinable and oxygen is -2. Remove experimental data points with an energy above hull > 1 eV as potential outliers.

- Labeling: Treat experimentally synthesized crystals from ICSD as the "Positive" class. All other calculated or hypothetical structures are treated as the "Unlabeled" class.

2. Model Training (Co-training with PU Learning):

- Architecture: Employ two Graph Convolutional Neural Networks (GCNNs) with different biases: ALIGNN (encodes bonds and angles) and SchNet (uses continuous-filter convolution).

- PU Learning Base: Implement the method by Mordelet and Vert, where each classifier learns to distinguish positive examples from the unlabeled set.

- Co-training Loop:

- Iteration 0: Train a base PU learner (e.g., ALIGNN0) on the initial positive and unlabeled data.

- The trained agent scores the unlabeled data. The top-k most confidently labeled positive instances are added to the positive training set for the other agent.

- The process repeats, with the two agents (ALIGNN and SchNet) iteratively exchanging newly labeled positive data.

- Final Prediction: The final labels are determined by averaging the prediction scores from both classifiers after the co-training iterations, enhancing generalizability and reducing model bias [21].

3. Model Evaluation:

- Primary Metric: Focus on achieving high recall on internal and leave-out test sets to ensure most synthesizable materials are correctly identified.

- Secondary Check: Evaluate model performance on predicting stability (formation energy) as a sanity check; poor performance is expected due to the unlabeled set's contamination with stable but unsynthesized materials [21].

Protocol: Planning Synthesis with Retro-Rank-In

This protocol describes a ranking-based framework for inorganic retrosynthesis, which excels at recommending novel precursors [2].

1. Problem Formulation:

- Objective: Given a target material T, generate a ranked list of precursor sets (e.g., {P1, P2, ..., Pm}) that are likely to synthesize T.

- Reformulation: Frame the task as learning a pairwise ranker that scores the compatibility between a target T and a precursor candidate P, rather than a multi-label classification over a fixed set of precursors.

2. Model Setup:

- Representation: Use a composition-based transformer model to generate embeddings for both target and precursor materials, placing them in a unified latent space.

- Ranker Training: Train a pairwise ranking model on known target-precursor pairs from historical data. The model learns to assign a higher score to precursor sets that are more chemically compatible with the target.

3. Inference and Precursor Recommendation:

- Candidate Generation: For a novel target, the model can score any precursor from a large candidate pool (including those not seen during training) using their learned embeddings.

- Output: The framework outputs a ranked list of precursor sets, with the ranking indicating the predicted likelihood of successful synthesis, enabling the exploration of entirely new synthetic routes [2].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated text-mining and machine learning workflow for defining and predicting synthesizability.

Data-Driven Synthesizability Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

This table catalogues essential computational and data "reagents" required for executing the protocols described in this document.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Data-Driven Synthesis Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function in Protocol | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Borges & LimeSoup [6] | Software Toolkit | Content Acquisition (Sec 3.1) | Custom web-scraping and parser for scientific journal HTML/XML. |

| BERT / BiLSTM-CRF Models [6] | NLP Model | Paragraph Classification & MER (Sec 3.1) | Identifies synthesis paragraphs and extracts material entities with high accuracy (F1: 99.5%). |

| SpaCy & NLTK [6] | NLP Library | Action & Quantity Extraction (Sec 3.1) | Parses dependency trees and syntax trees to link actions and quantities to materials. |

| ICSD / Materials Project API [21] | Materials Database | Data Curation for ML (Sec 3.2) | Provides authoritative source of experimental and computational crystal structures. |

| ALIGNN & SchNet [21] | Graph Neural Network | Model Architecture for SynCoTrain (Sec 3.2) | Encodes crystal structure; provides complementary "chemist" and "physicist" perspectives. |

| PyMatgen [21] | Python Library | Data Pre-processing | Analyzes materials structures and determines oxidation states for data filtering. |

| 7'-O-DMT-morpholino thymine | 7'-O-DMT-morpholino thymine | 7'-O-DMT-morpholino thymine is a key building block for synthesizing Morpholino oligonucleotides for gene silencing research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Pseudolarifuroic acid | Pseudolarifuroic acid, MF:C30H42O4, MW:466.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

AI in the Lab: Machine Learning Models for Synthesis Prediction

The discovery and synthesis of novel inorganic materials are pivotal for advancements in technologies ranging from renewable energy to electronics. However, a significant bottleneck exists in transitioning from computationally designed materials to their physical realization in the laboratory. Unlike organic chemistry, where retrosynthesis is a well-established, multi-step process, inorganic materials synthesis largely remains a one-step process reliant on trial-and-error experimentation of precursor materials, lacking a general unifying theory [24]. This creates a compelling opportunity for machine learning (ML) to bridge this knowledge gap by learning directly from historical synthesis data. Within this field, precursor recommendation—predicting a set of precursors that will react to form a desired target material—stands as a critical task [24]. This application note focuses on the ElemwiseRetro model, a template-based approach for inorganic precursor recommendation, and situates it within the broader research landscape of solution-based inorganic materials synthesis prediction.

The ElemwiseRetro Model: Core Architecture and Methodology

ElemwiseRetro represents a significant template-based ML approach for inorganic retrosynthesis. The model operates by employing domain heuristics and a classifier for template completions [24]. Its core objective is to predict a viable set of precursors for a given target inorganic material.

Model Workflow and Logic

The following diagram illustrates the high-level logical workflow of a template-based precursor recommendation system like ElemwiseRetro, from input to output.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Implementing and training a model like ElemwiseRetro requires a structured protocol. The following table outlines the key stages and their descriptions.

Table 1: Experimental Protocol for a Template-Based Precursor Recommendation Model

| Stage | Description | Key Parameters/Actions |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Data Acquisition | Obtain a dataset of known inorganic synthesis reactions. | Utilize datasets such as the solution-based synthesis database (35,675 procedures) from scientific literature [6]. |

| 2. Data Preprocessing | Clean data and represent materials for model input. | Represent elemental composition as a vector; balance chemical reactions to establish precursor-target relationships [24] [6]. |

| 3. Template Definition | Define or extract the reaction "templates" the model will use. | Templates encode connectivity changes; balance specificity and coverage [25]. |

| 4. Model Training | Train the classifier to score or complete templates for a given target. | Use a training set of known reactions; the model learns domain heuristics for template matching and completion [24]. |

| 5. Model Inference | Use the trained model to predict precursors for new target materials. | Input the target material's composition; the model outputs a ranked list of precursor sets [24]. |

Performance Analysis and Comparative Evaluation

To understand ElemwiseRetro's position in the field, it is crucial to compare its capabilities and performance against other state-of-the-art models. The following table summarizes a qualitative comparison based on key capabilities for synthesis planning.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Inorganic Retrosynthesis Models

| Model | Core Approach | Discover New Precursors? | Extrapolation to New Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| ElemwiseRetro | Template-based with heuristic classifier [24] | No [24] | Medium [24] |

| Synthesis Similarity | Retrieval of known syntheses of similar materials [24] | No [24] | Low [24] |

| Retrieval-Retro | Dual-retriever with multi-label classifier [24] | No [24] | Medium [24] |

| Retro-Rank-In | Ranking model in a shared latent space [24] | Yes [24] | High [24] |

A key limitation of ElemwiseRetro, as well as other models like Retrieval-Retro, is its inability to recommend precursors not present in its training set. This is because these models frame retrosynthesis as a multi-label classification task over a fixed set of known precursors. For example, while ElemwiseRetro might successfully recombine seen precursors, it cannot propose a novel precursor like CrB for the target Crâ‚‚AlBâ‚‚ if CrB was absent from the training data [24]. In contrast, ranking-based approaches like Retro-Rank-In embed materials into a continuous space, enabling this generalization.

The Scientist's Computational Toolkit

The development and application of models like ElemwiseRetro rely on a suite of computational and data resources. The following table details these essential "research reagents."

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Computational Synthesis Prediction

| Resource / Reagent | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Synthesis Databases | Structured datasets of inorganic synthesis procedures (e.g., 35,675 solution-based recipes) used for model training and validation [6]. |

| Materials Project DFT Database | A computational database of ~80,000 compounds with properties like formation energy, used to incorporate domain knowledge (e.g., thermodynamics) into models [24]. |

| Compositional Representation | A numerical vector representing the elemental fractions in a compound, serving as a fundamental input feature for ML models [24]. |

| Reaction Templates | Graph transformation rules or heuristic patterns that encode the connectivity changes between precursors and target materials [25]. |

| Pre-trained Material Embeddings | General-purpose, chemically meaningful vector representations of materials, often from large-scale models, used to boost ML performance [24]. |

| Digoxigenin NHS ester | Digoxigenin NHS ester, MF:C35H50N2O10, MW:658.8 g/mol |

| ortho-Topolin riboside-d4 | ortho-Topolin riboside-d4, MF:C17H19N5O5, MW:377.4 g/mol |

Integrated Workflow: From Data to Prediction

The application of a model like ElemwiseRetro is one component in a larger materials discovery pipeline. The diagram below integrates this model into a comprehensive workflow for computational synthesis prediction, highlighting its interaction with other tools and data sources.

Application Notes

The Crystal Synthesis LLM (CSLLM) framework represents a significant advancement in the application of large language models for predicting the synthesizability of inorganic materials and identifying their precursors. CSLLM is designed to achieve an ultra-accurate true positive rate (TPR) of 98.8% for the prediction of synthesizability and precursors of crystal structures [26]. This performance demonstrates the potential of specialized LLMs to overcome a critical bottleneck in materials discovery and design.

The development of CSLLM is situated within a broader research context that leverages data-driven approaches to master the challenge of determining synthesis routes for novel materials [6]. Unlike computational data, the experimentally determined properties and structures of inorganic materials are primarily available in manually curated databases or, more prevalently, within the vast and unstructured text of millions of scientific publications [6] [27]. The CSLLM framework likely utilizes advanced Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques to extract and codify synthesis information from this literature, transforming human-written descriptions into a machine-operable format suitable for training predictive models [6] [27].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics of the CSLLM Framework

| Metric | Reported Performance | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| True Positive Rate (TPR) | 98.8% [26] | Indicates a very high accuracy in correctly identifying synthesizable crystals and their precursors. |

| Primary Application | Prediction of synthesizability and precursors for crystal structures [26] | Addresses a core challenge in the inverse design of materials. |

The transformative impact of AI like CSLLM lies in its ability to learn the complex patterns of synthesis from past experimental data. Whereas the development of synthesis routes has traditionally been based on heuristics and individual experience, models like CSLLM can use the accumulated knowledge from thousands of publications to predict viable pathways for novel materials [6]. This aligns with the goals of initiatives like the Materials Genome Initiative (MGI), which seeks to accelerate materials innovation [6]. The application of such models is particularly crucial for solution-based inorganic synthesis, which involves complex procedures with precise precursor quantities, concentrations, and sequential actions [6].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Information Extraction for Training Data Generation

This protocol details the methodology for constructing a large-scale dataset of synthesis procedures from scientific literature, which serves as the foundational training data for a model like CSLLM. It is adapted from automated information extraction pipelines used in materials informatics [6].

1. Content Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Acquisition: Use a customized web-scraper (e.g., "Borges") to download journal articles in HTML/XML format from major publishers (e.g., Wiley, Elsevier, Royal Society of Chemistry) with appropriate publisher consent [6].

- Text Conversion: Convert articles from publisher-specific HTML/XML into raw text using a dedicated parser toolkit (e.g., "LimeSoup") that accounts for different journal format standards [6].

- Storage: Store the full text and metadata of the articles in a database (e.g., MongoDB) for subsequent processing [6].

2. Synthesis Paragraph Classification

- Objective: Identify paragraphs containing information about solution synthesis (e.g., sol-gel, hydrothermal, precipitation) from the full text of papers [6].

- Model: Employ a fine-tuned Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) model [6] [27].

- Procedure:

- Pre-train the BERT model on full-text paragraphs from a large corpus of materials science papers in a self-supervised way [6].

- Fine-tune the model on a labeled dataset of paragraphs categorized into synthesis types ("solid-state", "sol-gel", "hydrothermal", etc.) and "none of the above" [6].

- Apply the trained classifier to all paragraphs to filter for those relevant to solution-based synthesis [6].

3. Materials Entity Recognition (MER)

- Objective: Identify and classify all materials entities within a synthesis paragraph as "target", "precursor", or "other" [6].

- Model: Use a two-step, sequence-to-sequence model [6]:

- Step 1: A BERT-based BiLSTM-CRF (Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory with a Conditional Random Field top layer) network to identify and tag word tokens as materials entities [6].

- Step 2: A second BERT-based BiLSTM-CRF network to classify the identified materials entities into their specific roles (target, precursor, other) [6].

- Training: Train the model on an annotated dataset of synthesis paragraphs where each word token is labeled [6].

4. Extraction of Synthesis Actions and Attributes

- Objective: Identify the actions performed during synthesis (e.g., mixing, heating, drying) and their corresponding attributes (e.g., temperature, time, environment) [6].

- Model & Algorithm:

- Action Identification: Use a recurrent neural network with word embeddings (e.g., Word2Vec trained on synthesis paragraphs) to label verb tokens in a sentence with specific synthesis actions [6].

- Attribute Extraction: For each identified synthesis action, parse a dependency sub-tree of the sentence (using a library like SpaCy) to find the syntactic connections to words describing temperature, time, and environment [6].

- Value Extraction: Use a rule-based regular expression approach on the connected phrases to extract the numerical values and units of these attributes [6].

5. Extraction of Material Quantities

- Objective: Assign numerical quantities (e.g., molarity, mass, volume) to their corresponding material entities [6].

- Algorithm:

- Use the NLTK library to build a syntax tree for each sentence [6].

- Implement an algorithm to cut the syntax tree into the largest sub-trees, each containing only one material entity [6].

- Within each material-specific sub-tree, search for and extract numerical quantities [6].

- Assign the found quantities to the unique material entity in that sub-tree [6].

6. Building Reaction Formulas

- Objective: Represent the synthesis procedure as a balanced chemical reaction formula [6].

- Procedure:

- Convert all material entities from text strings into a structured chemical-data format using a material parser toolkit [6].

- Pair the target material with precursors that contain at least one element (excluding H and O) present in the target [6].

- Define these as "precursor candidates" and use them to compute a balanced reaction formula for the synthesis procedure [6].

Protocol: Model Training and Prediction for Synthesizability

This protocol outlines the core process for developing and applying a model like CSLLM for synthesizability prediction.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational and data resources essential for developing and operating a framework like CSLLM.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents & Resources for the CSLLM Framework

| Item Name | Function / Role in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| Borges Scraper | A customized web-scraper used for the automated downloading of scientific articles from publishers' websites in HTML/XML format with consent [6]. |

| LimeSoup Parser | A dedicated toolkit for converting journal articles from publisher-specific HTML/XML into raw text, accounting for varying format standards [6]. |

| Pre-trained BERT Model | A transformer-based language model, pre-trained on a large corpus of scientific text, which serves as the base for tasks like paragraph classification and entity recognition [6] [27]. |

| BiLSTM-CRF Network | A neural network architecture combining Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) and a Conditional Random Field (CRF) layer, used for precise sequence labeling tasks like Materials Entity Recognition (MER) [6]. |

| SpaCy Library | A natural language processing library used for efficient syntactic dependency parsing, which helps in extracting attributes (temperature, time) associated with synthesis actions [6]. |

| NLTK Library | The Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK) is used to build syntax trees for sentences, enabling the algorithm to correctly associate extracted quantities with their corresponding material entities [6]. |

| Material Parser Toolkit | An in-house software tool designed to convert text-string representations of materials into a structured chemical-data format, which is necessary for computing balanced reaction formulas [6]. |

| Structured Synthesis Database | A centralized database (e.g., MongoDB) storing the codified synthesis procedures, including targets, precursors, quantities, actions, and reaction formulas, which forms the training dataset for the LLM [6]. |

| 1,4-Dimethoxybenzene-d4 | 1,4-Dimethoxybenzene-d4, MF:C8H10O2, MW:142.19 g/mol |

| CRBN ligand-1 | CRBN ligand-1, MF:C11H12N2O2, MW:204.22 g/mol |

Workflow and Data Flow Diagram

The logical relationship between structured and unstructured data in building a predictive synthesis model is critical to understanding the CSLLM framework's operation.

The discovery and synthesis of novel inorganic materials are critical for advancing technologies in renewable energy and electronics. However, a significant bottleneck exists in translating computationally predicted materials into physically realized compounds, as synthesis planning largely relies on trial-and-error experimentation [28] [2]. Unlike organic synthesis, which benefits from well-defined retrosynthesis rules and multi-step reactions using small building blocks, inorganic materials synthesis involves a one-step reaction from precursor compounds to a target solid-state material, for which no general unifying theory exists [2].

Machine learning (ML) presents an opportunity to bridge this knowledge gap by learning directly from experimental synthesis data. Early ML approaches framed retrosynthesis as a multi-label classification task, but these methods struggled to generalize to novel reactions and could not propose precursors absent from their training data [28] [2]. The Retro-Rank-In framework addresses these limitations by reformulating the problem as a ranking task within a shared latent space, enabling more flexible and generalizable synthesis planning [28] [2] [29].

The Retro-Rank-In Framework

Core Conceptual Innovation

Retro-Rank-In introduces a novel paradigm for inorganic retrosynthesis. Instead of treating precursor prediction as a classification problem, it learns a pairwise ranker that evaluates the chemical compatibility between a target material and candidate precursors [2]. This approach is built on two core components:

- A composition-level transformer-based materials encoder that generates chemically meaningful representations for both target materials and precursors.

- A Ranker that learns to predict the likelihood that a target material and a precursor candidate can co-occur in viable synthetic routes [2].

The key innovation lies in embedding both target and precursor materials into a shared latent space, which enables the model to generalize to novel precursor combinations not encountered during training [2].

Comparative Analysis Against Previous Approaches

Table 1: Comparison of Retro-Rank-In with prior retrosynthesis methods

| Model | Discovers New Precursors | Chemical Domain Knowledge Incorporation | Extrapolation to New Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| ElemwiseRetro [2] | ✗ | Low | Medium |

| Synthesis Similarity [2] | ✗ | Low | Low |

| Retrieval-Retro [2] | ✗ | Low | Medium |

| Retro-Rank-In (Ours) [2] | ✓ | Medium | High |

This comparative advantage stems from fundamental architectural differences. Prior methods like Retrieval-Retro used one-hot encoding in a multi-label classification output layer, restricting them to recombining existing precursors rather than predicting entirely novel ones [2]. In contrast, Retro-Rank-In's shared embedding space and ranking formulation enable genuine discovery capabilities.

Quantitative Performance Assessment

Retro-Rank-In was rigorously evaluated on challenging dataset splits designed to mitigate data duplicates and overlaps, providing a robust assessment of its generalizability [28] [2].

Table 2: Performance outcomes demonstrating generalization capability

| Evaluation Metric | Performance Demonstration |

|---|---|

| Out-of-Distribution Generalization | Sets new state-of-the-art, particularly in out-of-distribution generalization and candidate set ranking [28] |

| Novel Precursor Prediction | Correctly predicted verified precursor pair CrB + Al for Crâ‚‚AlBâ‚‚ despite never encountering them during training [28] [2] |

| Ranking Capability | Offers superior candidate set ranking compared to prior approaches [28] |

The framework's ability to identify the correct precursor pair (CrB + Al) for Crâ‚‚AlBâ‚‚ without having seen this combination during training exemplifies a capability absent in prior work and highlights its potential for accelerating the synthesis of novel materials [28] [2].

Experimental Protocols

Problem Formulation and Data Representation

The retrosynthesis problem is formally defined as predicting a ranked list of precursor sets ((\mathbf{S}1, \mathbf{S}2, \ldots, \mathbf{S}K)) for a target material (T), where each precursor set (\mathbf{S} = {P1, P2, \ldots, Pm}) consists of (m) individual precursor materials [2]. The number of precursors (m) can vary for each set.

Compositional Representation Protocol:

- For a given target material (T), represent its elemental composition as a vector (\mathbf{x}T = (x1, x2, \dots, xd)), where each (x_i) corresponds to the fraction of element (i) in the compound.

- The dimension (d) represents the count of all considered elements in the materials universe [2].

- This representation provides a standardized input format for the transformer-based encoder.

Model Training and Implementation

Shared Latent Space Learning:

- Embedding Generation: Process compositional representations through a composition-level transformer to generate embeddings for both target and precursor materials.

- Pairwise Ranking Optimization: Train the Ranker component to optimize the relative ordering of precursor candidates for each target material.

- Negative Sampling: Implement custom sampling strategies to address dataset imbalance, as chemical datasets typically have many possible precursors but few positive labels [2].

Inference Protocol:

- For a novel target material, generate its embedding using the trained transformer encoder.

- Score candidate precursors (including those not seen during training) using the pairwise Ranker based on their embeddings.

- Rank precursor sets by their aggregated compatibility scores with the target material.

- Output the ranked list of precursor sets for experimental validation [2].

Workflow Visualization

Retro-Rank-In Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential components for implementing Retro-Rank-In

| Research Reagent | Function in Framework |

|---|---|

| Compositional Representation Vector | Standardized numerical representation of elemental composition serving as model input [2] |

| Transformer-Based Encoder | Neural network architecture generating chemically meaningful embeddings in shared latent space [2] |

| Pairwise Ranker | Scoring function evaluating chemical compatibility between target and precursor embeddings [2] |

| Bipartite Graph of Inorganic Compounds | Data structure encoding relationships between compounds for training the ranking model [28] [29] |

| Wilfordine | Wilfordine, MF:C43H49NO19, MW:883.8 g/mol |

| Moracin J | Moracin J, CAS:73338-89-3, MF:C15H12O5, MW:272.25 g/mol |