Accelerating Discovery: A Guide to Computational and Data-Driven Inorganic Material Synthesis

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the computational guidelines and data-driven methods that are revolutionizing the synthesis of inorganic materials.

Accelerating Discovery: A Guide to Computational and Data-Driven Inorganic Material Synthesis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the computational guidelines and data-driven methods that are revolutionizing the synthesis of inorganic materials. Aimed at researchers and scientists, we explore the foundational principles of thermodynamics and kinetics that guide synthesis feasibility. The article delves into advanced methodologies, including generative AI, machine learning frameworks, and robotic laboratories, demonstrating their application in predicting synthesis pathways and optimizing conditions. We address key challenges such as data scarcity and model generalization, offering troubleshooting and optimization strategies. Finally, we present rigorous validation through case studies and performance comparisons with traditional methods, concluding with the transformative implications of these technologies for accelerating the design of next-generation materials in fields like energy storage and biomedicine.

The Physical and Data Foundations of Modern Material Synthesis

The synthesis of inorganic materials can be conceptualized as navigation on a multidimensional energy landscape, an abstract representation of the potential energy of a system as a function of its atomic configurations and reaction coordinates [1] [2]. Within this landscape, local energy minima correspond to potentially synthesizable compounds, while energy barriers represent the kinetic challenges that must be overcome to transition between states [1]. The fundamental goal of computational-guided synthesis is to identify pathways that lead from readily available precursor materials (starting minima) to desired target materials (target minima) by overcoming manageable kinetic barriers [1].

Understanding these landscapes requires integrating both thermodynamic and kinetic principles. Thermodynamics determines the relative stability of different compounds and phases, answering the question of whether a material can form. Kinetics governs the pathways and rates of synthesis reactions, addressing how and how quickly a material forms [1] [2]. This framework is particularly crucial for targeting metastable materials—compounds that are not the global minimum in energy but can be synthesized and persist under specific conditions by navigating around kinetic barriers that prevent their conversion to more stable forms [3].

Table 1: Key Thermodynamic and Kinetic Parameters in Energy Landscape Analysis

| Parameter | Description | Role in Synthesis | Computational Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formation Energy | Energy difference between a compound and its constituent elements in their standard states [1]. | Determines thermodynamic stability relative to elemental precursors. | Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations [1] [3]. |

| Energy Above Hull | Energy difference between a compound and the convex hull of stable phases in its chemical space [1] [3]. | Indicates thermodynamic stability against decomposition into other compounds; a key metric for synthesizability. | High-throughput DFT using databases like the Materials Project [3]. |

| Amorphous Limit | The free energy of the amorphous phase of a composition, serving as an upper bound for synthesizable metastable crystalline polymorphs [3]. | Defines the maximum energy window for potentially synthesizable metastable phases; polymorphs above this limit are highly unlikely to be synthesized [3]. | Ab initio sampling of amorphous configurations [3]. |

| Activation Energy | The energy barrier that must be overcome for a reaction or diffusion process to occur [1]. | Controls reaction rates and the feasibility of kinetic pathways; determines synthesis time and temperature. | Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) method, Transition State Theory [1]. |

Computational Frameworks and Descriptors

The Amorphous Limit as a Thermodynamic Bound

A critical advancement in predicting synthesizability is the establishment of the amorphous limit, which provides a chemistry-dependent, thermodynamic upper bound on the free energy scale for metastable crystalline polymorphs [3]. The underlying hypothesis is that if a crystalline phase has a higher enthalpy than its amorphous counterpart at 0 K, it cannot be synthesized at any finite temperature under constant pressure. This is because the amorphous phase, having higher entropy, experiences a greater rate of free energy decrease with rising temperature, maintaining its thermodynamic advantage [3]. Consequently, any polymorph with an energy above this amorphous limit is thermodynamically precluded from being synthesized via standard laboratory methods. This limit varies significantly between chemical systems, ranging from approximately 0.05 eV/atom to 0.5 eV/atom for various metal oxides [3].

Integrating Physics with Machine Learning

The integration of physical models with machine learning (ML) has created a powerful paradigm for accelerating inorganic material synthesis [4] [1] [2]. ML models can uncover complex, non-linear relationships within synthesis data that are difficult to model with explicit physical equations. However, to overcome challenges like data scarcity, these models are enhanced by embedding domain-specific knowledge. Using physical descriptors derived from thermodynamics and kinetics—such as formation energies, energy above hull, and activation barriers—markedly enhances the predictive performance and interpretability of ML models [4] [1] [2]. This approach fosters the development of physics-inspired ML models and physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) that adhere to fundamental physical laws while learning from data [2].

Experimental Protocols for Energy Landscape Analysis

Protocol: Thermodynamic Analysis of Synthesis Feasibility

This protocol outlines the steps to assess the thermodynamic feasibility of a target inorganic material, using resources like the Materials Project database.

1. Objective: To determine the thermodynamic stability and synthesizability window of a target inorganic compound.

2. Materials and Computational Tools:

- Computer with internet access.

- Access to the Materials Project database (materialsproject.org) or similar.

- DFT Software (e.g., VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO) for calculating unknown phases.

- Software for structure visualization and analysis (e.g., VESTA).

3. Procedure: 1. Define the Chemical System: Identify the precise chemical composition of the target material (e.g., Cdâ‚â‚‹â‚“Znâ‚“Te). 2. Database Query: - Search the Materials Project for all known crystalline phases within the defined chemical system. - Extract the calculated formation energies and energies above the convex hull for each phase. 3. Construct the Convex Hull: - Plot the formation energy per atom against composition for all stable and metastable phases. - The convex hull is formed by connecting the points of the most stable phases at each composition. Any phase lying on this line is thermodynamically stable, while those above it are metastable. 4. Calculate Energy Above Hull (ΔE): For the target metastable phase, determine its energy above the convex hull (ΔE) using the equation: ΔE = Etarget - Ehull, where E_hull is the energy of the hull at the same composition. 5. Compare to the Amorphous Limit: - Estimate the amorphous limit for the composition. This can be done via ab initio sampling of amorphous configurations [3] or by referencing literature values for similar chemistries (e.g., ~0.05 eV/atom for Bâ‚‚O₃, ~0.25 eV/atom for TiOâ‚‚) [3]. - If ΔE is below the amorphous limit, the material is thermodynamically accessible. If ΔE is above this limit, conventional synthesis is highly improbable [3].

4. Data Interpretation:

- A low ΔE (e.g., < 50 meV/atom) suggests high synthesis feasibility.

- A higher ΔE requires kinetic strategies to bypass decomposition.

- The amorphous limit provides a hard upper bound for synthesis under standard conditions.

Protocol: Data Extraction from Scientific Literature for ML

This protocol describes a method for building a structured dataset from published scientific papers to train machine learning models for synthesis prediction.

1. Objective: To create a curated dataset linking synthesis parameters (precursors, temperature, time) to material outcomes (success/failure, phase purity) from literature.

2. Materials and Tools:

- Literature Databases: Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, ACS Publications.

- Text Mining Tools: Natural Language Processing (NLP) libraries (e.g., spaCy in Python), custom scripts.

- Data Storage: Spreadsheet software or SQL database.

3. Procedure:

1. Define Data Schema: Design a structured table with the following columns: Material_Composition, Synthesis_Method, Precursors, Temperature_C, Time_hr, Atmosphere, Product_Phase, Product_Purity, DOI.

2. Paper Collection:

- Perform a systematic literature search using keywords related to the target material class (e.g., "perovskite oxide synthesis," "CdTe solid-state reaction").

- Filter results to include only papers with detailed experimental sections.

3. Text Parsing and Information Extraction:

- Use text mining tools to automatically identify and extract sentences containing keywords like "synthesized at," "heated to," "precursor," and "X-ray diffraction showed."

- Manually validate and correct the extracted data to ensure accuracy. This step is crucial due to the non-standardized reporting in scientific literature [4] [1].

4. Data Standardization:

- Convert all units to a standard set (e.g., °C, hours).

- Standardize chemical names (e.g., "CdO" instead of "cadmium oxide").

- Categorical variables (e.g., Synthesis_Method) should be assigned fixed labels (e.g., Solid_State, Hydrothermal).

5. Data Curation: Flag and review entries with missing or conflicting information. The final dataset should be as complete and consistent as possible.

4. Application:

The curated dataset can be used to train supervised ML models (e.g., Random Forests, Gradient Boosting) to predict the outcome (Product_Phase) given a set of synthesis conditions (Precursors, Temperature, etc.) [4] [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Computational Tools for Inorganic Synthesis Research

| Item | Function / Relevance | Example in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium Tetrachloroplatinate | A common precursor for the synthesis of platinum-containing inorganic complexes, such as the anti-cancer drug cisplatin [5]. | Used in inorganic and organometallic synthesis protocols [5]. |

| Cadmium Oxide (CdO) & Tellurium (Te) | Precursors for the solid-state synthesis of CdTe, a key semiconductor material [6]. | Thermodynamic analysis of Cd-Te system involves measuring P-T-X phase equilibria using these elements [6]. |

| Hydrothermal Autoclave Reactor | A sealed vessel that enables synthesis in aqueous solutions at elevated temperatures and pressures, facilitating the formation of crystalline materials like zeolites [1] [7]. | Essential equipment for Synthesis in the fluid phase methods, allowing control over temperature and pressure [1]. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) Codes | Software for first-principles calculation of material properties, including formation energies and electronic structures, which are fundamental descriptors for energy landscape analysis [1] [3]. | Used in the Thermodynamic Analysis protocol to calculate the energy of unknown or hypothetical phases [3]. |

| In-Situ X-ray Diffraction (XRD) | An analytical technique used to track phase evolution and identify intermediates in real-time during a synthesis reaction [1]. | Critical for experimental validation in the closed-loop framework and for understanding reaction pathways [1]. |

| N-hexadecylaniline | N-Hexadecylaniline|CAS 4439-42-3|317.6 g/mol | |

| Spidoxamat | Spidoxamat, CAS:907187-07-9, MF:C19H22ClNO4, MW:363.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualization of Synthesis Pathways and Landscapes

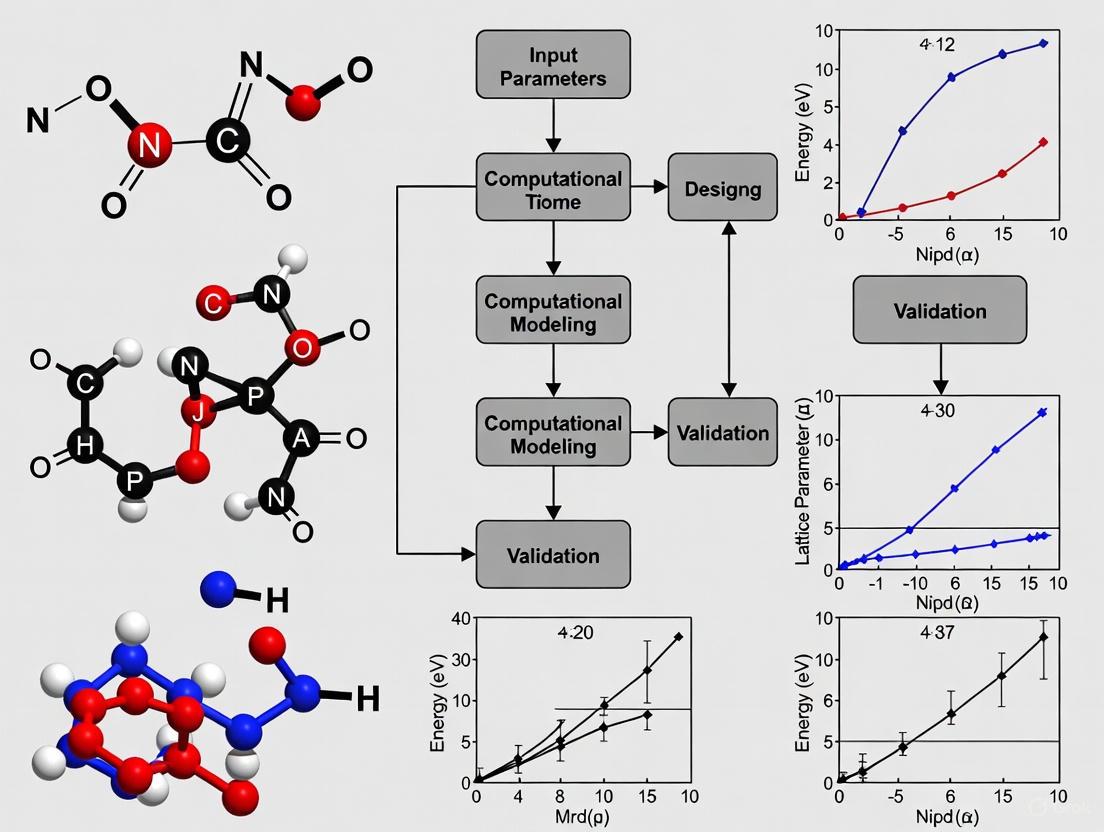

The following diagram illustrates a generalized energy landscape for inorganic synthesis, highlighting the competition between thermodynamic and kinetic control.

The discovery and synthesis of novel inorganic materials are critical for addressing global challenges in energy, electronics, and medicine. Traditional material development has largely relied on trial-and-error experimental approaches, which are often time-consuming, resource-intensive, and limited in their ability to explore complex chemical spaces systematically. The integration of computational guidance is fundamentally reshaping this paradigm by providing data-driven insights that accelerate synthesis planning, optimize reaction parameters, and enhance the predictability of experimental outcomes. This shift enables researchers to move from retrospective analysis to prospective materials design, significantly reducing development cycles and increasing success rates in inorganic material synthesis.

Foundations of Computational Guidance

Computational approaches in inorganic materials synthesis are built upon physical models derived from thermodynamics and kinetics, which provide fundamental insights into synthesis feasibility. These models help researchers understand phase stability, reaction pathways, and potential metastable states that could yield novel functional materials.

The incorporation of machine learning (ML) has further enhanced these computational frameworks by enabling the identification of complex, non-linear relationships between synthesis parameters and material outcomes that are difficult to capture with physical models alone. ML techniques can effectively map structure-property relationships and suggest optimal experimental conditions for chemical reactions, creating a more predictive approach to materials synthesis [8] [4].

Key Physical Principles

- Thermodynamic Stability: Computational screening based on formation energy predictions helps identify synthesizable materials with negative formation energies, ensuring thermodynamic viability before experimental attempts.

- Kinetic Control: Models that incorporate kinetic barriers help predict phase selection and morphological control during synthesis, enabling researchers to navigate away from thermodynamic sinks toward metastable materials with desirable properties.

- Energy Landscape Mapping: Comprehensive mapping of energy landscapes provides guidance on synthesis pathways by identifying low-energy routes to target materials while avoiding competing phases.

Data-Driven Methodologies

Data Acquisition and Curation

The effectiveness of computational guidance depends heavily on the quality and quantity of available data. Current approaches utilize multiple strategies for data acquisition:

- High-Throughput Experimental Data: Automated synthesis systems generate standardized datasets under controlled conditions, providing consistent data for model training [9].

- Scientific Literature Mining: Natural language processing (NLP) techniques extract synthesis parameters and material properties from published literature, significantly expanding available datasets [10].

- Experimental Database Curation: Structured databases like the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) and Materials Project provide experimental and computed properties for thousands of materials [10] [11].

Table 1: Primary Data Sources for Computational Materials Synthesis

| Data Source | Data Type | Scale | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) | Crystal structures | >260,000 transition metal complexes [10] | Structure-property relationships, stability prediction |

| Materials Project | Computed material properties | >100,000 inorganic compounds [11] | Thermodynamic stability screening, property prediction |

| CoRE MOF 2019 | Curated experimental structures | ~10,000 metal-organic frameworks [10] | Stability analysis, gas adsorption prediction |

| High-Throughput Experimentation | Uniform experimental measurements | Variable, depending on system | Model training, synthesis optimization |

A significant challenge in data curation is the systematic extraction of information from literature, particularly in matching chemical structures to reported properties. Named entity recognition for material identification remains difficult, especially for complex systems like metal-organic frameworks where naming conventions are inconsistent [10]. Additionally, the absence of "failed" experiments in published literature creates a positive bias in datasets that must be addressed through careful model design and data augmentation strategies.

Material Descriptors and Feature Engineering

Effective computational guidance relies on appropriate descriptors that encode critical material characteristics. Commonly utilized descriptors include:

- Compositional Features: Elemental properties, stoichiometric ratios, and electronic structure parameters.

- StructuralDescriptors: Symmetry information, coordination environments, and topological descriptors.

- Synthesis Conditions: Temperature, pressure, precursor concentrations, and reaction time.

The integration of domain knowledge through physics-inspired descriptors significantly enhances model performance and interpretability. By embedding thermodynamic and kinetic principles as domain-specific knowledge, both predictive accuracy and model transparency are markedly improved [4].

Machine Learning Applications in Synthesis

ML techniques have been successfully applied across various aspects of inorganic material synthesis, from prediction of synthesisability to optimization of reaction conditions.

Synthesis Outcome Prediction

Machine learning models trained on experimental data can predict the outcomes of synthesis experiments, including:

- Phase Selection: Predicting which crystalline phases will form under specific synthesis conditions.

- Morphological Control: Forecasting particle size, shape, and structural characteristics based on precursor chemistry and reaction parameters.

- Stability Assessment: Predicting material stability under various environmental conditions (thermal, aqueous, mechanical) [10].

For metal-organic frameworks, NLP-assisted data extraction has enabled the creation of stability prediction models for thermal decomposition (Td values), solvent removal, and aqueous stability, with datasets containing thousands of measured stability values [10].

Inverse Materials Design

Reinforcement learning (RL) approaches have shown particular promise for inverse design, where materials are generated to meet specific property objectives:

- Deep Q-Networks (DQN): Learn action-value functions to guide the selection of elements and compositions that maximize multi-objective reward functions.

- Policy Gradient Networks (PGN): Directly optimize generation policies to produce materials satisfying target properties [11].

These RL frameworks can incorporate both materials property objectives (band gap, formation energy, mechanical properties) and synthesis objectives (processing temperature, time), enabling holistic materials design that balances performance with practical synthesizability [11].

Table 2: Machine Learning Approaches in Inorganic Materials Synthesis

| ML Technique | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised Learning | Property prediction, stability classification | High accuracy for defined tasks, interpretable models | Requires large labeled datasets |

| Reinforcement Learning | Inverse design, multi-objective optimization | Can explore beyond training data, handles complex objectives | Training instability, reward design complexity |

| Natural Language Processing | Literature mining, data extraction | Leverages existing knowledge, creates large datasets | Named entity recognition challenges, data quality variability |

| Deep Generative Models | Novel material generation, structure prediction | Can propose completely new compositions | May generate invalid structures, data inefficient |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Protocol: Computational Guidance for Oxide Material Synthesis

This protocol outlines the implementation of a reinforcement learning framework for the design of inorganic oxides with target properties, based on methodologies successfully demonstrated in recent studies [11].

Preparation and Setup

- Data Collection: Acquire inorganic oxide data from Materials Project database, including compositions, formation energies, band gaps, elastic properties, and synthesis temperatures.

- Preprocessing: Filter data to include only experimentally reported oxides, normalize property values, and encode elemental compositions for model input.

- Predictor Model Training: Train supervised machine learning models (e.g., random forests, neural networks) to predict material properties and synthesis parameters from chemical composition alone.

RL Model Configuration

- State Representation: Represent states as material compositions, either complete or partially completed.

- Action Space: Define possible actions as the addition of an element (from a set of 80 possible elements) with its corresponding composition (integer 0-9).

- Reward Function: Design a weighted multi-objective reward function Rₜ(sₜ, aₜ) = ΣᵢwᵢRᵢ,ₜ(sₜ, aₜ) where Rᵢ,ₜ represents rewards from i-th objective (e.g., band gap, formation energy, sintering temperature) and wᵢ represents user-specified weights.

Training Procedure

- Episode Definition: Set episode horizon to T=5 steps, allowing generation of materials with up to 5 elements.

- Terminal Rewards: Assign rewards only at terminal states (fully generated compounds) with zero rewards at non-terminal states.

- Policy Optimization: For PGN approach, directly optimize policy parameters to maximize expected reward; for DQN approach, learn action-value function to guide policy.

Validation and Analysis

- Chemical Validity Checks: Apply rules for charge neutrality, electronegativity balance, and negative formation energy.

- Template-Based Structure Prediction: Use template matching to propose feasible crystal structures for generated compositions.

- Experimental Verification: Select top candidates for experimental synthesis and characterization to validate model predictions.

Hardware Systems for Autonomous Synthesis

The implementation of computational guidance requires integration with automated synthesis systems that enable closed-loop optimization:

- Microfluidic Platforms: Enable high-throughput screening of synthesis parameters with real-time characterization (e.g., UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy) for rapid parameter optimization [9].

- Robotic Synthesis Systems: Dual-arm robotic systems can execute complex synthesis protocols with superior reproducibility and efficiency compared to manual operations [9].

- Closed-Loop Control Systems: Integrate automated synthesis hardware with ML models to create self-optimizing systems that continuously refine synthesis parameters based on experimental outcomes.

Computational Materials Design Workflow

Case Studies and Applications

Intelligent Synthesis of Quantum Dots

The integration of automated microfluidic systems with machine learning has demonstrated remarkable efficiency in optimizing quantum dot synthesis:

- Platform Design: Automated microfluidic reactors with integrated UV-Vis spectroscopy enable real-time monitoring of nanocrystal nucleation and growth kinetics [9].

- Parameter Optimization: ML algorithms rapidly screen precursor ratios, temperatures, and reaction times to optimize photoluminescence quantum yield and particle size distribution.

- Kinetic Insights: The high-temporal-resolution data obtained from these systems provides fundamental insights into nucleation and growth mechanisms, informing improved synthesis strategies.

Metal-Organic Framework Stability Prediction

Natural language processing has enabled the creation of comprehensive stability prediction models for metal-organic frameworks:

- Data Extraction: NLP techniques applied to thousands of publications extracted thermal decomposition temperatures (Td), solvent removal stability, and aqueous stability data [10].

- Model Performance: Trained models predict MOF stability based on structural and chemical descriptors, guiding the selection of frameworks for specific applications.

- Design Rules: Model interpretation identifies chemical motifs associated with enhanced stability, informing the design of new robust MOFs.

Gold Nanoparticle Synthesis Optimization

Autonomous systems have been successfully applied to the synthesis of gold nanoparticles with precise morphological control:

- Millifluidic Reactors: Enable gram-scale production with precise control over aspect ratios of gold nanorods [9].

- Closed-Loop Optimization: Integration of synthesis platforms with characterization tools and ML algorithms creates self-optimizing systems that autonomously navigate parameter spaces to achieve target properties.

- Reproducibility Enhancement: Automated systems significantly improve batch-to-batch reproducibility compared to manual synthesis methods.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Computational-Guided Synthesis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Synthesis | Application Examples | Computational Guidance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal-Organic Framework Precursors | Provide metal nodes and organic linkers for framework assembly | Gas storage, catalysis, separation | Stability prediction models guide precursor selection for target applications [10] |

| Oxide Precursors (e.g., metal salts, alkoxides) | Source of metal cations for oxide formation | Semiconductor, dielectric, and energy materials | RL algorithms optimize elemental combinations for target properties [11] |

| Quantum Dot Precursors (e.g., metal carboxylates, chalcogenide sources) | Form nanocrystal cores with controlled composition and size | Optoelectronics, bioimaging, displays | ML models correlate precursor ratios with optical properties [9] |

| Gold Chloride (HAuClâ‚„) | Primary precursor for gold nanoparticle synthesis | Catalysis, sensing, therapeutics | Autonomous optimization of reduction conditions for size and shape control [9] |

| Structure-Directing Agents | Control crystal morphology and phase selection | Zeolites, mesoporous materials | Computational screening identifies effective agents for target structures |

Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite significant progress, several challenges remain in the full implementation of computational guidance for inorganic material synthesis:

- Data Scarcity and Quality: Limited high-quality experimental data, particularly for failed syntheses, restricts model training and generalization [10] [4].

- Interpretability and Trust: Complex ML models often function as "black boxes," making it difficult for experimentalists to trust and act on their predictions.

- Cross-scale Modeling: Integrating insights from atomic-scale simulations to macroscopic synthesis conditions remains computationally challenging.

- Standardization Needs: Lack of standardized data formats, reporting standards, and experimental protocols hinders data integration and model transferability.

Future advancements will likely focus on several key areas:

- Human-Machine Collaboration: Developing intuitive interfaces that facilitate effective collaboration between experimental expertise and computational guidance.

- Large Language Models: Leveraging advanced NLP for more efficient extraction and synthesis of knowledge from the vast chemical literature.

- Automated Discovery Platforms: Fully integrated systems that combine computational prediction with automated synthesis and characterization in closed-loop workflows.

- Physics-Informed ML: Hybrid models that embed physical principles into machine learning architectures for improved extrapolation and interpretability.

Closed-Loop Optimization System

The paradigm shift from trial-and-error to computational guidance represents a fundamental transformation in inorganic materials research. By integrating physical models, machine learning, and automated experimentation, researchers can now navigate the complex synthesis space with unprecedented efficiency and predictability. The frameworks, protocols, and case studies outlined in this application note provide a roadmap for implementing these approaches in diverse research settings. As computational guidance continues to evolve, it promises to accelerate the discovery of novel functional materials and unlock new possibilities in materials design and manufacturing. The future of inorganic synthesis lies in the seamless integration of computational intelligence with experimental expertise, creating a collaborative ecosystem that transcends traditional disciplinary boundaries.

The adoption of machine learning (ML) in inorganic materials science has transformed the research paradigm, shifting the bottleneck from computational prediction to experimental synthesis. The core of this data-driven revolution lies in the construction of high-quality, large-scale datasets that can train models to navigate the complex synthesis landscape. These datasets, built through automated high-throughput experiments and sophisticated literature mining, provide the foundational knowledge required to predict synthesis pathways and optimize experimental conditions, thereby accelerating the discovery and development of novel functional materials [1] [4]. This document details the protocols and application notes for constructing such datasets, a critical component within the broader framework of computational guidelines for inorganic materials research.

Data Acquisition Methodologies

High-Throughput Experimental Data Generation

High-throughput experimentation (HTE) intensifies data acquisition by rapidly performing and analyzing a vast number of synthesis reactions. A leading strategy is the use of self-driving laboratories or Materials Acceleration Platforms (MAPs), which integrate automated synthesis, real-time characterization, and AI-guided decision-making in a closed-loop system [12].

Protocol: Dynamic Flow Experiments for Data Intensification

This protocol, adapted from recent work on colloidal quantum dots, details how to map transient reaction conditions to steady-state equivalents for efficient data generation [12].

System Setup:

- Equipment: Microfluidic or continuous flow reactor system, in-line real-time characterization probes (e.g., UV-Vis, Raman, NMR spectroscopy), automated liquid handling systems, and a central control computer running experiment-selection algorithms.

- Reagent Preparation: Prepare precursor solutions at specified concentrations, ensuring they are compatible with the flow system (e.g., filtered to prevent clogging).

Experimental Procedure: a. Define Design Space: Identify the key synthesis parameters to be explored (e.g., precursor concentration, reaction temperature, residence time, ligand ratio). b. Implement Dynamic Flow: Instead of maintaining constant conditions, program the flow reactor to continuously and dynamically vary input parameters (e.g., using gradient pumps). This creates a continuous stream of transient conditions. c. In-line Characterization: Use the in-line probes to monitor the properties of the resulting material (e.g., absorbance for quantum dot size, composition) in real-time as conditions change. d. Data Logging: Correlate each set of experimental conditions (inputs) with the corresponding material properties (outputs) and the timestamped characterization data.

Data Processing: a. Digital Twin Modeling: Use the logged data to build a model (a "digital twin") that maps the steady-state material properties to the dynamic input parameters. b. Validation: Periodically halt the dynamic flow to perform a static experiment and confirm the digital twin's predictions.

This method has been shown to improve data acquisition efficiency by at least an order of magnitude compared to traditional one-variable-at-a-time approaches in self-driving labs [12].

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Autonomous Flow Synthesis

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Example in CdSe CQD Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Precursor Solutions | Source of elemental components for the target material | Cadmium Oleate (Cd-precursor), Selenium-Trioctylphosphine (Se-precursor) |

| Ligands / Surfactants | Control nucleation, growth, and stabilization of nanoparticles | Trioctylphosphine Oxide (TOPO), Oleic Acid (stabilizing ligands) |

| Solvents | Reaction medium for precursor dissolution and reaction | 1-Octadecene (high-boiling-point non-polar solvent) |

| In-line Spectroscopic Probes | Real-time, non-invasive monitoring of reaction progress and product quality | UV-Vis for optical properties, Raman for composition |

Diagram 1: Autonomous high-throughput experimental workflow.

Literature Mining for Historical Data

Text-mining the vast corpus of published scientific literature provides a rich source of pre-existing synthesis knowledge. The primary challenge is converting unstructured text from experimental sections into a structured, machine-readable format [13].

Protocol: Natural Language Processing (NLP) for Synthesis Recipe Extraction

This protocol outlines the pipeline for text-mining inorganic solid-state synthesis recipes [13].

Data Procurement:

- Source: Obtain full-text permissions from major scientific publishers. Focus on papers published post-2000 in HTML/XML format to avoid parsing errors from scanned PDFs.

- Identification: Scan manuscripts to identify paragraphs containing synthesis procedures using keyword-based probabilistic models (e.g., keywords: "calcined", "sintered", "synthesized").

Entity Extraction: a. Anonymization: Replace all chemical compound mentions with a general tag (e.g.,

<MAT>). b. Role Labeling: Use a trained BiLSTM-CRF (Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory - Conditional Random Field) neural network to classify the role of each<MAT>tag astarget,precursor, orreaction_mediabased on sentence context. c. Operation Classification: Use Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) to cluster synonyms of synthesis operations (e.g., "calcined", "fired", "heated") into standardized categories:mixing,heating,drying,shaping,quenching.Data Compilation and Reaction Balancing: a. Structuring: Combine extracted entities and operations into a structured format (e.g., JSON). b. Reaction Balancing: Attempt to write a balanced chemical reaction for the precursors and target, often requiring the inclusion of volatile gases (e.g., Oâ‚‚, COâ‚‚). This enables subsequent calculation of reaction energetics using DFT data from sources like the Materials Project.

Application Note: The extraction yield of this pipeline is typically low (≈28%), meaning only a fraction of identified synthesis paragraphs result in a balanced chemical reaction. Furthermore, datasets built this way often suffer from limitations in volume, variety, veracity, and velocity, reflecting historical biases in how chemists have explored materials space [13]. The emergence of advanced Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT offers new opportunities to improve the accuracy and efficiency of this process. For instance, MaTableGPT, a GPT-based extractor, achieved an F1-score of 96.8% for extracting table data from water-splitting catalysis literature [14].

Table 2: Quantitative Outcomes of Literature Mining Pipelines

| Metric | Reported Outcome (Solid-State Synthesis) | Notes and Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Total Papers Processed | 4,204,170 [13] | Scale demonstrates data availability. |

| Identified Synthesis Paragraphs | 188,198 [13] | Includes various synthesis types. |

| Solid-State Synthesis Recipes with Balanced Reactions | 15,144 (from 53,538 paragraphs) [13] | Low extraction yield (28%) is a key challenge. |

| Extraction Accuracy (F1-Score) | Up to 96.8% with MaTableGPT on table data [14] | LLMs can significantly improve accuracy. |

Diagram 2: Text-mining workflow for synthesis recipes.

Dataset Curation and Feature Engineering

Material and Synthesis Descriptors

Raw experimental data must be transformed into meaningful descriptors that ML models can learn from. These features can be derived from both the material's composition/structure and the synthesis conditions [1] [4].

- Thermodynamic Descriptors: Formation energy, energy above the convex hull (stability), reaction energy.

- Kinetic Descriptors: Activation energies for diffusion, nucleation barriers.

- Compositional Descriptors: Elemental properties (electronegativity, ionic radius), charge-balancing criteria.

- Synthesis Process Descriptors: Heating temperature and time, precursor properties, atmosphere, synthesis method type.

Application Note: While simple heuristics like the charge-balancing criterion are often used, they can be unreliable. For example, only 37% of observed Cs binary compounds in the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) meet this criterion under common oxidation states [1]. Integrating physical models of thermodynamics and kinetics as domain-specific knowledge significantly enhances the predictive performance and interpretability of ML models [1] [4].

Data Management and Quality Control

Curating a high-quality dataset is paramount. Key considerations include:

- Handling Data Scarcity and Imbalance: Experimental data, especially for novel materials, is inherently scarce and biased towards commonly studied compositions. Techniques like transfer learning, where a model pre-trained on a large computational dataset (e.g., from DFT) is fine-tuned on a smaller experimental dataset, can be highly effective [12].

- Addressing Veracity Issues: Text-mined data can contain errors from extraction or reflect inaccuracies in the original reporting. Automated analysis can also be error-prone; for instance, automated Rietveld analysis of powder X-ray diffraction data is not yet fully reliable and requires careful validation [15]. Implementing rigorous data validation steps and manual spot-checking is essential.

The construction of robust datasets through high-throughput experiments and literature mining is a foundational pillar for ML-guided inorganic materials synthesis. While high-throughput automation generates high-quality, targeted data rapidly, literature mining leverages the vast historical knowledge embedded in the scientific record. The integration of these two streams, augmented by physics-informed descriptors and rigorous data management, creates a powerful knowledge base. This enables the development of predictive models that can recommend synthesis routes for novel materials, ultimately closing the loop in an intelligent, autonomous research paradigm and accelerating the journey from material prediction to successful synthesis.

In the pursuit of accelerating inorganic materials discovery, computational guidelines have emerged as a powerful paradigm to navigate the complex synthesis landscape. Central to this approach is the use of core physical descriptors—quantifiable parameters rooted in thermodynamics and kinetics that determine a material's synthesizability and stability. The energy landscape of materials provides a fundamental perspective on the relationship between the energy of different atomic configurations and synthesis parameters, illustrating the stability of possible compounds and their reaction trajectories [1]. When a system moves from one energy minimum to another, it must overcome energy barriers directly related to nucleation energies and activation energies for diffusion in solid-state synthesis [1].

Unlike organic synthesis, where retrosynthesis strategies are well-established, inorganic solid-state synthesis lacks universal principles, with mechanisms that often remain unclear [1] [16]. This knowledge gap has traditionally forced reliance on chemical intuition and trial-and-error experimentation. However, descriptor-based approaches now offer a more systematic methodology. These descriptors, which span from phase diagrams to formation enthalpies, enable researchers to identify materials with high synthesis feasibility and determine optimal experimental conditions before entering the laboratory [1] [17]. By embedding the interplay between thermodynamics and kinetics as domain-specific knowledge, both the predictive performance and interpretability of synthesis planning models are markedly enhanced [4].

Essential Physical Descriptors for Synthesis Planning

The prediction and optimization of inorganic material synthesis rely on several interconnected physical descriptors. The table below summarizes these key descriptors, their theoretical foundations, and their specific roles in synthesis planning.

Table 1: Core Physical Descriptors for Inorganic Materials Synthesis

| Descriptor | Theoretical Basis | Role in Synthesis Planning | Computational Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formation Enthalpy (ΔHf) | First Law of Thermodynamics | Determines thermodynamic stability of a compound from its constituent elements [18]. | High-temperature calorimetry; DFT calculations [18]. |

| Energy Above Hull (Ehull) | Phase Diagram Convex Hull Construction | Quantifies thermodynamic metastability; lower values indicate higher synthesizability [13]. | DFT-computed databases (e.g., Materials Project) [13]. |

| Reaction Energy (ΔErxn) | Thermodynamics of Chemical Reactions | Drives phase transformation kinetics; more negative values favor faster reactions [17]. | Calculated from formation enthalpies of precursors and target [17]. |

| Inverse Hull Energy (ΔEinv) | Local Stability in Composition Space | Measures selectivity for a target over competing by-products; larger values favor phase purity [17]. | Derived from the convex hull in a specific composition slice [17]. |

These descriptors are not independent; they form a hierarchical framework for understanding synthesis. Formation Enthalpy and Energy Above Hull provide a global assessment of a material's inherent stability. In contrast, Reaction Energy and Inverse Hull Energy are context-dependent, offering crucial guidance for selecting specific precursor combinations and predicting the outcome of solid-state reactions [17] [13]. The fundamental assumption is that synthesizable materials should not have any decomposition products with greater thermodynamic stability, though kinetic stabilization can also play a critical role [1].

Computational Workflow for Descriptor-Driven Synthesis

Implementing a descriptor-driven approach requires a structured workflow that transforms raw computational data into actionable synthesis insights. The following protocol outlines the key steps, from data acquisition to precursor selection.

Protocol 1: Computational Workflow for Precursor Selection

Objective: To identify optimal precursor pairs for a target multicomponent inorganic material using thermodynamic descriptors.

Materials and Data Sources:

- Target Material Composition: e.g., a quaternary oxide like a battery cathode material.

- Computational Database: Access to a database of computed material properties, such as the Materials Project (contains DFT-calculated formation energies for ~80,000 compounds) [19] [16].

- Software Tools: Python materials libraries (e.g., Pymatgen) for phase diagram and descriptor analysis [19].

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition and Phase Diagram Construction:

- Query the database for all known phases within the relevant chemical system (e.g., Li-Mn-O for an LiMnOâ‚‚ target).

- Use the formation energies of these stable phases to construct a multi-dimensional convex hull phase diagram [13].

Descriptor Calculation:

- Identify Precursor Candidates: Enumerate all plausible simple oxides, carbonates, or other salts that can serve as precursors.

- Calculate Reaction Energy (ΔErxn): For each candidate precursor pair (e.g., A and B), compute the solid-state reaction energy: ΔErxn = Etarget - (EA + EB). Normalize this value per atom of the target product. More negative values indicate a stronger thermodynamic driving force [17].

- Evaluate Inverse Hull Energy (ΔEinv): For the reaction path between the two precursors, identify all competing stable phases. The inverse hull energy is defined as the energy difference between the target and the most stable linear combination of these competing phases along that specific composition slice. A larger, more negative ΔEinv indicates greater selectivity for the target phase [17].

Precursor Ranking and Selection:

- Apply selection principles to rank the precursor pairs. Prioritize pairs where:

- The target is the deepest point on the convex hull along their reaction path (Principle 3).

- The target has the largest inverse hull energy, ensuring selectivity over impurities (Principle 5).

- The precursors are relatively high-energy to maximize the reaction driving force (Principle 2) [17].

- Apply selection principles to rank the precursor pairs. Prioritize pairs where:

Validation: This thermodynamic strategy was experimentally validated in a robotic inorganic synthesis laboratory. For 35 target quaternary oxides, precursors selected through this approach frequently yielded higher phase purity than those chosen by traditional methods [17].

Experimental Protocols for Descriptor Validation

While computational descriptors provide powerful predictions, their validation requires careful experimental synthesis and characterization. The following protocols detail this process.

Protocol 2: Robotic Solid-State Synthesis of Multicomponent Oxides

Objective: To synthesize a target multicomponent oxide with high phase purity using precursors identified from computational descriptors.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Solid-State Synthesis

| Item | Specification | Function | Handling Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precursor Powders | High-purity (>99%) oxides, carbonates | Provide elemental constituents for the target material. | Dry at 200°C before use to remove adsorbed water. |

| Ball Mill Jar | Zirconia or stainless steel, with milling media | Mechanical mixing and particle size reduction of precursors. | Clean thoroughly with ethanol between batches. |

| Milling Solvent | Anhydrous ethanol or isopropanol | Facilitates mixing and prevents agglomeration during milling. | Use reagent grade. |

| Furnace | Programmable, with controlled atmosphere | High-temperature solid-state reaction. | Calibrate temperature profile regularly. |

Methodology:

- Precursor Weighing and Mixing:

- Accurately weigh precursor powders according to the stoichiometry of the target compound.

- Transfer the powder mixture into a ball mill jar with milling media and a suitable solvent (e.g., anhydrous ethanol).

- Mill the mixture for 1-2 hours at 300 RPM to ensure homogeneity.

Drying and Pelletization:

- Transfer the resulting slurry to a petri dish and dry in an oven at ~80°C.

- Once dry, gently grind the powder with an agate mortar and pestle.

- Press the powder into a pellet using a uniaxial press at a typical pressure of 2-5 tons to improve inter-particle contact.

Thermal Treatment:

- Place the pellet in an alumina crucible and transfer it to a box furnace.

- Heat the sample according to an optimized thermal profile. A generic protocol may involve:

- Ramp at 5°C/min to a calcination temperature (e.g., 500-700°C for 6 hours) to decompose carbonates/nitrates.

- Cool, re-grind, and re-pelletize the sample.

- Ramp at 5°C/min to a higher sintering temperature (e.g., 900-1200°C for 12 hours).

- Use ambient air or a controlled gas atmosphere (e.g., Oâ‚‚, Ar) as required by the material system.

Product Characterization:

- Powder X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Grind a portion of the sintered pellet and analyze via XRD. Match the diffraction pattern to the reference pattern of the target phase to assess phase purity [17].

Protocol 3: Determination of Formation Enthalpy by Calorimetry

Objective: To measure the standard enthalpy of formation (ΔHf) of an intermetallic compound using high-temperature calorimetry.

Materials:

- High-purity constituent elements (e.g., metal chips or powders).

- High-temperature calorimeter (e.g., drop calorimeter).

- Arc melter or furnace for pre-alloying (if necessary).

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation:

- Weigh the constituent elements in the correct stoichiometric ratio.

- Homogenize the mixture by arc-melting under an inert argon atmosphere, flipping and re-melting the sample several times to ensure uniformity.

Calorimetric Measurement:

- The calorimetric measurement is based on the heat effect of a reaction that forms the compound from its elements.

- Load the sample and a reference material into the calorimeter.

- At a controlled temperature, dissolve the pre-synthesized compound sample in a suitable solvent bath within the calorimeter. Alternatively, directly react the elemental mixture.

- Precisely measure the heat released or absorbed during the reaction.

Data Analysis:

- Calculate the standard enthalpy of formation from the measured heat effect, using appropriate thermochemical cycles and reference data.

- This directly measured ΔHf serves as a fundamental benchmark for validating computationally predicted formation energies [18].

Advanced Applications and Data-Driven Extensions

The integration of core physical descriptors with machine learning (ML) and high-throughput experimentation is creating a new paradigm for intelligent synthesis science. Descriptors like formation energy and elemental properties are used as features in ML models to predict the formation probability of new compounds in unexplored regions of chemical space [19]. For instance, element descriptors derived from local coordination environments in known crystal structures can be used to generate "New Material Exploration Maps," which visually guide the search for novel ternary compounds [19].

Furthermore, text-mining of historical synthesis literature has enabled the creation of large-scale datasets, linking synthesis recipes with outcomes [13] [20]. When combined with thermodynamic descriptors, these datasets power advanced ML models for retrosynthesis planning. Frameworks like Retro-Rank-In move beyond simple classification; they learn to rank precursor sets by embedding targets and precursors in a shared chemical space, allowing them to recommend novel, previously unseen precursors for a target material, thereby accelerating the discovery of new synthesis routes [16].

AI in Action: Machine Learning and Generative Models for Synthesis Design

The development of novel functional materials is pivotal for accelerating scientific progress in fields such as catalysis, microelectronics, renewable energy, and drug development [21]. Traditional materials discovery has relied on iterative experimental trial-and-error and high-throughput computational screening, but these methods are fundamentally limited by the vastness of the chemical space and the high computational cost of density functional theory (DFT) calculations [22] [23]. Inverse design represents a paradigm shift by directly generating material structures that satisfy predefined property constraints, effectively reversing the traditional structure-to-property approach [24].

Generative artificial intelligence models, particularly diffusion models, have emerged as powerful frameworks for inverse design of inorganic materials. These models learn the underlying probability distribution of known crystal structures and can generate novel, theoretically stable materials across the periodic table [22]. MatterGen, a diffusion-based generative model developed by Microsoft, exemplifies this capability by generating stable, diverse inorganic materials that can be further fine-tuned toward a broad range of property constraints [22] [24]. Compared to previous generative models, structures produced by MatterGen are more than twice as likely to be new and stable, and more than ten times closer to the local energy minimum [22].

Fundamental Principles of Diffusion Models

Diffusion models are a class of probabilistic generative models that learn complex data distributions by sequentially denoising data starting from random noise [25]. These models have demonstrated remarkable performance in generating high-quality samples across various domains, including images, video, and now materials science [26].

Core Mechanism

The fundamental principle of diffusion models involves two complementary processes [25] [26]:

- Forward Diffusion Process: This process systematically perturbs the structure of data distribution by adding Gaussian noise to the input data over a series of steps until the data is transformed into pure Gaussian noise.

- Reverse Diffusion Process: Also known as denoising, this process learns to recover the original data structure from the perturbed data distribution by progressively removing noise.

Mathematical Framework

Two main perspectives characterize diffusion models [25]:

Variational Perspective: Models like Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models (DDPMs) use variational inference to approximate the target distribution by minimizing the Kullback-Leibler divergence between the approximate and target distributions.

Score Perspective: Models including Noise-conditioned Score Networks (NCSNs) and Stochastic Differential Equations (SDEs) use a maximum likelihood-based estimation approach, leveraging the score function (gradient) of the log-likelihood of the data.

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental diffusion process for material generation:

Figure 1: The core diffusion process for material generation.

MatterGen: Architecture and Capabilities

MatterGen is a diffusion-based generative model specifically tailored for designing crystalline materials across the periodic table [22]. Its architecture incorporates several innovations that enable it to generate stable, diverse inorganic materials with desired properties.

Customized Diffusion Process for Crystalline Materials

Unlike standard diffusion models designed for images, MatterGen employs a customized diffusion process that respects the unique periodic structure and symmetries of crystalline materials [22]. The model defines a crystalline material by its repeating unit cell, comprising:

- Atom types (A): Chemical elements present in the structure

- Coordinates (X): Atomic positions within the unit cell

- Periodic lattice (L): Lattice parameters defining the unit cell shape

For each component, MatterGen implements a physically motivated corruption process with an appropriate limiting noise distribution [22]:

- Coordinate Diffusion: Uses a wrapped Normal distribution that respects periodic boundary conditions and approaches a uniform distribution at the noisy limit.

- Lattice Diffusion: Takes a symmetric form and approaches a distribution whose mean is a cubic lattice with average atomic density from the training data.

- Atom Type Diffusion: Implemented in categorical space where individual atoms are corrupted into a masked state.

Adapter Modules for Property Conditioning

A key innovation in MatterGen is the introduction of adapter modules that enable fine-tuning the base model on desired property constraints [22]. These tunable components are injected into each layer of the base model to alter its output depending on the given property label. This approach remains effective even when the labeled dataset is small compared to unlabeled structure datasets, which is common due to the high computational cost of calculating properties.

The fine-tuned model is used with classifier-free guidance to steer generation toward target property constraints [22]. This enables MatterGen to generate materials with specific:

- Chemical composition

- Symmetry (space groups)

- Scalar properties (magnetic density, electronic properties, mechanical properties)

Training Data and Base Model

MatterGen's base model was trained on Alex-MP-20, a curated dataset comprising 607,683 stable structures with up to 20 atoms recomputed from the Materials Project and Alexandria datasets [22]. This large and diverse training set enables the model to learn the fundamental principles of inorganic crystal chemistry.

The following workflow illustrates the complete MatterGen pipeline for inverse design:

Figure 2: Complete MatterGen inverse design workflow.

Quantitative Performance of MatterGen and Related Models

Extensive benchmarking demonstrates that MatterGen significantly outperforms previous generative models for materials design. The table below summarizes key performance metrics compared to other approaches:

Table 1: Performance comparison of generative models for materials design

| Model | Type | SUN Materials* | Average RMSD | Property Conditioning | Elements Covered |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MatterGen | Diffusion | 75% | <0.076 Ã… | Multiple properties | >80 elements |

| CDVAE | VAE | ~29% | ~0.8 Ã… | Limited | Limited |

| DiffCSP | Diffusion | N/A | N/A | Structure prediction only | Given atom types |

| DiffCrysGen | Diffusion | N/A | N/A | Single property | Up to 94 elements |

| GNoME | Deep Learning | N/A | N/A | None | Extensive |

Percentage of generated structures that are Stable, Unique, and New with energy above hull <0.1 eV/atom [22] *Root Mean Square Deviation between generated and DFT-relaxed structures [22]

MatterGen also demonstrates remarkable diversity in generation, with 100% uniqueness when generating 1,000 structures and only dropping to 52% after generating 10 million structures [22]. Additionally, 61% of generated structures are new with respect to existing databases, and the model has rediscovered more than 2,000 experimentally verified structures from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) not seen during training [22].

Experimental Protocols for Inverse Design

Protocol 1: Single-Property Optimization with MatterGen

This protocol enables the design of materials with targeted electronic, magnetic, mechanical, or thermal properties.

Required Materials and Computational Resources:

- Pre-trained MatterGen model

- Property evaluation method (DFT, ML potential, or predictive model)

- High-performance computing resources

- Structure visualization software

Procedure:

Define Property Target: Specify the target property value (e.g., band gap = 3.0 eV for semiconductors).

Fine-tune Base Model:

- Utilize adapter modules for the specific property of interest

- Employ a labeled dataset with property values (can be small)

- Incorporate classifier-free guidance to steer generation

Generate Candidate Structures:

- Run the fine-tuned model to generate candidate structures

- Typical batch size: 64-128 structures per iteration

Filter and Validate:

- Apply SUN (Stable, Unique, Novel) filtering:

- Thermodynamic stability: Energy above hull (E_hull) < 0.1 eV/atom

- Uniqueness: Remove duplicates from current generation

- Novelty: Remove matches to known databases

- Perform geometry optimization using universal ML interatomic potentials

- Apply SUN (Stable, Unique, Novel) filtering:

Property Evaluation:

- Calculate target properties via DFT, ML potentials, or empirical models

- For electronic properties: DFT with appropriate exchange-correlation functional

- For mechanical properties: MLIP simulations or DFT calculations

Iterative Refinement:

- Use high-performing candidates to further fine-tune the model

- Continue until convergence to target property values (typically 60 iterations)

Applications: This protocol has been successfully applied to design materials with target band gaps (3.0 eV), high magnetic densities (>0.2 Ã…â»Â³), specific heat capacities (>1.5 J/g/K), and strong epitaxial matching to substrates [21].

Protocol 2: Multi-Property Optimization with MatInvent

MatInvent extends MatterGen with reinforcement learning (RL) for complex design tasks with multiple, potentially conflicting constraints [21].

Procedure:

Formulate RL Framework:

- Frame denoising generation as a multi-step Markov Decision Process

- Define reward function combining multiple property targets

- Set KL regularization to prevent overfitting to rewards

Initialize RL Optimization:

- Start with pre-trained MatterGen model as prior

- Generate initial batch of structures (m = 100-200)

- Apply SUN filtering and geometry optimization

Evaluate Multi-property Rewards:

- Calculate property values for all candidates

- Compute composite reward balancing all targets

- Select top-k samples ranked by reward

Policy Optimization:

- Update diffusion model using reward-weighted KL regularization

- Employ experience replay for sample efficiency

- Use diversity filter to maintain exploration

Convergence:

- Continue for ~60 iterations (~1,000 property evaluations)

- Monitor average property values approaching targets

Applications: This protocol has designed low-supply-chain-risk magnets and high-κ dielectrics, demonstrating robust optimization with multiple competing objectives [21].

Protocol 3: Experimental Validation of Generated Materials

This protocol outlines the procedure for experimental synthesis and validation of AI-generated materials.

Procedure:

Stability Assessment:

- Perform DFT relaxation of generated structures

- Calculate energy above convex hull (E_hull < 0.1 eV/atom recommended)

- Evaluate dynamic stability through phonon calculations

Synthesizability Prediction:

- Calculate synthesizability scores using ML models [21]

- Assess precursor availability and reaction pathways

- Evaluate phase stability at relevant temperatures

Experimental Synthesis:

- Select synthesis route based on material system (e.g., solid-state reaction, CVD)

- Optimize synthesis conditions (temperature, pressure, atmosphere)

- Characterize phase purity (XRD) and composition (EDS)

Property Measurement:

- Measure target properties experimentally

- Compare with computational predictions

- Iterate with computational team for model improvement

Case Study: MatterGen designed Ta₂O₆, which was successfully synthesized with measured bulk modulus of 169 GPa, within 20% of the design target of 200 GPa [24].

Table 2: Essential resources for generative inverse design of materials

| Category | Resource | Function | Examples/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generative Models | MatterGen | Primary model for generating stable inorganic materials | DiffCrysGen, CDVAE |

| Training Data | Alex-MP-20 | Curated dataset of 607,683 stable structures for training | Materials Project, OQMD, ICDD |

| Property Predictors | ML Interatomic Potentials | Rapid property evaluation during generation | M3GNet, CHGNet |

| Validation Tools | Density Functional Theory | Gold-standard validation of stability and properties | VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO |

| Structure Analysis | PyMatGen | Materials analysis and processing | ASE, pymatgen |

| Synthesizability | Synthesis Likelihood Models | Predict experimental feasibility | - |

| High-Performance Computing | GPU Clusters | Training and running diffusion models | NVIDIA A100, H100 |

Future Outlook and Applications

Generative AI for inverse materials design represents a transformative approach that transcends traditional screening-based methods. As the field evolves, several promising directions emerge:

Integration with Automated Laboratories: Combining generative models with robotic synthesis and characterization for closed-loop materials discovery.

Multi-scale Modeling: Incorporating generative approaches for microstructural control along with atomic structure design [26].

Cross-domain Applications: Transferring insights from successful applications in protein design to materials science [24].

The integration of generative AI into materials research workflows promises to significantly accelerate the discovery and development of novel functional materials for energy storage, catalysis, electronics, and pharmaceutical applications. As these models continue to improve, they will enable researchers to navigate the vast chemical space more efficiently, ultimately reducing the time and cost required to bring new materials from conception to practical application.

HATNet represents a significant advancement in computational materials science, providing a unified deep learning framework specifically engineered to optimize the synthesis of both organic and inorganic materials. By leveraging a multi-head attention mechanism, HATNet captures complex, non-linear dependencies within high-dimensional synthesis parameter spaces that traditional models often miss. This approach has demonstrated state-of-the-art performance, achieving 95% classification accuracy for optimizing MoSâ‚‚ synthesis and lower Mean Squared Error values for estimating Photoluminescent Quantum Yield compared to established benchmarks like XGBoost and Support Vector Machines [27]. Framed within the broader thesis of computational guidelines for inorganic material research, HATNet offers a robust, data-driven protocol for moving from large-scale synthesis attempts to precise, functionally-oriented modifications, ultimately accelerating the discovery and development of novel materials [28].

The design and synthesis of advanced materials, such as metal-organic frameworks and transition metal dichalcogenides, have traditionally been guided by empirical knowledge and high-throughput experimental trial-and-error [28]. This process is often mired by challenges such as data sparsity—where synthesis routes exist in a sparse, high-dimensional parameter space—and data scarcity, where few literature-reported syntheses exist for a material of interest [29]. HATNet addresses these challenges directly by integrating a shared attention-based architecture that is capable of handling both classification and regression tasks. This allows researchers to predict categorical synthesis outcomes (e.g., successful/unsuccessful formation of a phase) and continuous property values (e.g., PLQY) within a single, unified framework [27]. Its development signals a shift in materials science from purely empirical approaches towards a paradigm where artificial intelligence predictions enable more precise and efficient design [28].

Quantitative Performance Data

The following tables summarize the key quantitative benchmarks demonstrating HATNet's superiority over traditional machine learning models in material synthesis optimization.

Table 1: Overall Performance Benchmark of HATNet vs. Traditional Models

| Model/Framework | Task Type | Key Performance Metric | Reported Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| HATNet | MoSâ‚‚ Synthesis Optimization | Classification Accuracy | 95% [27] |

| HATNet | PLQY Estimation | Mean Squared Error (MSE) | Lower MSE than benchmarks [27] |

| Logistic Regression | SrTiO₃/BaTiO₃ Synthesis Prediction | Classification Accuracy | 74% [29] |

| PCA + Classifier (10-D) | SrTiO₃/BaTiO₃ Synthesis Prediction | Classification Accuracy | 68% [29] |

| Human Intuition | General Reaction Success | Classification Accuracy | ~78% [29] |

Table 2: Synthesis Optimization Performance for Specific Material Systems

| Material System | Optimization Task | HATNet Performance | Comparative Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| MoSâ‚‚ | Synthesis Condition Classification | 95% Accuracy [27] | Superior to traditional ML models [27] |

| SrTiO₃ / BaTiO₃ | Synthesis Target Prediction | n/a | Baseline accuracy with other models: 74% [29] |

| Brookite TiOâ‚‚ | Formation Driving Factors | n/a | Explored via latent space analysis [29] |

| MnOâ‚‚ | Polymorph Selection | n/a | Correlations with ion intercalation identified [29] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Data Preparation and Feature Representation for Inorganic Synthesis

This protocol is adapted from data-centric approaches used in virtual screening of inorganic materials synthesis [29].

- Objective: To construct a high-dimensional, canonical feature vector that numerically represents a material synthesis procedure from text-mined literature data.

- Materials & Reagents: Scientific literature database, computational text-mining tools, standard data preprocessing libraries.

- Procedure:

- Literature Data Extraction: Use automated text-mining scripts to extract quantitative synthesis parameters from scientific papers for the target material system (e.g., SrTiO₃). Key parameters include:

- Precursor identities and concentrations

- Heating temperatures and durations

- Solvent types and concentrations

- Pressure conditions [29]

- Feature Vector Construction: Represent each synthesis as a sparse, high-dimensional vector in a unified feature space. Each dimension corresponds to a specific parameter or action that could be performed across all syntheses in the dataset.

- Data Augmentation (for Data Scarcity): To overcome limited data for a single material, augment the dataset by including syntheses of chemically similar materials. Use ion-substitution similarity algorithms and compositional similarity metrics to create a larger, weighted dataset centered on the material of interest [29].

- Dimensionality Reduction: Process the sparse canonical feature vectors using a Variational Autoencoder to learn a compressed, low-dimensional latent representation. This step emphasizes the most informative combinations of synthesis parameters and improves downstream model performance [29].

- Literature Data Extraction: Use automated text-mining scripts to extract quantitative synthesis parameters from scientific papers for the target material system (e.g., SrTiO₃). Key parameters include:

Protocol B: HATNet Model Implementation for Synthesis Optimization

This protocol outlines the core architecture and training procedure for HATNet, based on its published description [27].

- Objective: To train a unified deep learning model for optimizing material synthesis conditions and predicting material properties.

- Materials & Reagents: Prepared dataset from Protocol A, machine learning framework with support for transformer architectures, high-performance computing resources.

- Procedure:

- Model Architecture Setup:

- Implement a multi-head attention mechanism as the core of the network. This allows the model to weigh the importance of different synthesis parameters dynamically when making a prediction.

- Design the network to have a shared backbone with task-specific output heads for simultaneous classification and regression.

- Model Training:

- Input the compressed latent representations of synthesis parameters from the VAE into HATNet.

- For classification tasks (e.g., successful MoSâ‚‚ synthesis), use a cross-entropy loss function.

- For regression tasks (e.g., PLQY estimation), use a Mean Squared Error loss function.

- Jointly optimize the model parameters to minimize the combined loss on both tasks.

- Model Validation & Prediction:

- Validate the model's performance on a held-out test set of synthesis data using accuracy and MSE as primary metrics.

- Use the trained model to screen new, virtual synthesis parameter sets. The model will output a probability of success for a target material and/or predict its key photoluminescent properties [27].

- Model Architecture Setup:

Workflow and Signaling Pathway Diagrams

HATNet Synthesis Optimization Workflow

Contrastive Predictive Coding in Latent Space

HATNet's predictive power is conceptually related to self-supervised learning paradigms like Contrastive Predictive Coding, which learns representations by predicting future information in a latent space [30] [31]. The following diagram illustrates this core concept.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for AI-Driven Material Synthesis

| Item Name | Type/Category | Function in Synthesis Optimization | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metal-Organic Precursors | Chemical Reagent | Serves as the primary source of metal nodes and organic linkers for constructing framework materials [28]. | Synthesis of Metal-Organic Frameworks with tailored porosity [28]. |

| Flux Agents (e.g., Alkali Halides) | Chemical Reagent | A molten salt medium that lowers reaction temperature, improves diffusion, and enables crystal growth [32]. | Growth of single crystals in solid-state synthesis [32]. |

| Autoclave Reactor | Laboratory Equipment | Provides a sealed vessel to contain reactions at elevated temperatures and pressures far above the boiling point of water [32]. | Hydrothermal/Solvothermal synthesis of zeolites or nanomaterials [32]. |

| Text-Mined Synthesis Database | Computational Resource | A structured collection of synthesis parameters extracted from scientific literature, serving as the primary dataset for model training [29]. | Building canonical feature vectors for model input; data augmentation [29]. |

| Variational Autoencoder (VAE) | Computational Algorithm | Performs non-linear dimensionality reduction on sparse synthesis data, creating an informative latent space for downstream tasks [29]. | Compressing high-dimensional synthesis parameters before optimization with HATNet [29]. |

| C14H14Cl2O2 | C14H14Cl2O2 | High-purity C14H14Cl2O2 for research applications. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for diagnostic, therapeutic, or personal use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Endothal-sodium | Endothal-sodium|PP2A Inhibitor|For Research Use | Endothal-sodium is a protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) inhibitor for research. This product is for laboratory research use only; not for personal use. | Bench Chemicals |

The discovery and synthesis of novel inorganic materials are fundamental to advancements in various technologies, from energy storage to catalysis. However, the traditional materials discovery cycle, which relies on a trial-and-error approach, often takes months or even years, creating a significant bottleneck for innovation [1]. The integration of computational guidelines, machine learning (ML), and robotics is transforming this paradigm, enabling high-throughput synthesis and validation. This application note details the practical implementation of robotic laboratories, providing structured protocols, key reagent solutions, and visual workflows to guide researchers in accelerating inorganic materials research within a computational framework.

Key Concepts and Rationale

The synthesis of inorganic materials is a complex process governed by thermodynamics and kinetics, often lacking universal principles [1]. Computational guidance helps navigate this complexity by using data from sources like the Materials Project to identify promising, stable target materials in silico before any experimental work begins [33]. Machine learning models, trained on vast historical data from scientific literature, can then propose effective synthesis recipes by assessing target "similarity," much like a human researcher would [33].

Robotic laboratories bring these computational predictions into the physical world by executing high-throughput experiments with minimal human intervention. They address several critical challenges:

- Precursor Selection: The choice of precursor powders is crucial, as unwanted side reactions often lead to impurities. New criteria based on phase diagrams and pairwise precursor reactions have been developed to maximize the yield of the target phase [34] [35].

- Active Learning: When initial recipes fail, autonomous labs use active learning algorithms to interpret experimental outcomes (e.g., from X-ray diffraction) and propose improved synthesis routes, creating a closed-loop discovery cycle [33].

Featured Case Studies in Practice

Case Study 1: The A-Lab for Novel Inorganic Solids

The A-Lab, an autonomous laboratory for the solid-state synthesis of inorganic powders, exemplifies the integration of these concepts [33].

- Objective: To synthesize 58 novel inorganic compounds predicted to be stable by computational data from the Materials Project and Google DeepMind.

- Implementation: The lab's workflow integrated computational target selection, ML-powered recipe generation, robotic solid-state synthesis, and AI-driven analysis.

- Outcome: Over 17 days of continuous operation, the A-Lab successfully synthesized 41 out of 58 target compounds (a 71% success rate), demonstrating the feasibility of autonomous materials discovery at scale [33]. The workflow is illustrated in Figure 1.

Case Study 2: Phase-Pure Synthesis via Robotic Validation

A separate study focused on the critical challenge of achieving high phase purity by introducing a new precursor selection method [34] [35].

- Objective: To validate a new set of criteria for selecting precursor powders to avoid unwanted reactions and increase target phase purity.

- Implementation: Researchers used the Samsung ASTRAL robotic lab to test 224 separate reactions targeting 35 different oxide materials.